Key Clinical Message

Cholecystocolonic fistula occurring as a complication of colonic diverticular disease is a rarely encountered clinical entity in which the patient may remain asymptomatic or present with vague abdominal or systemic symptoms. Imaging studies are usually not very reliable or effective in detecting direct communication between gallbladder and colon. However, indirect signs such as pneumobilia, gallstones, gallbladder adherent to colon and colonic diverticulosis may help reach the diagnosis. Treatment of cholecystocolonic fistula in symptomatic patients is usually surgical. However, in asymptomatic patients or patients with risk factors and comorbidities, non‐surgical options such as conservative management or biliary stenting can be considered.

Keywords: ascending colon, cholecystocolonic, diverticulitis, diverticulosis, fistula

1. INTRODUCTION

Fistulous communication between the colon and the biliary tree, or cholecystocolonic fistula (CCF), is a rare clinical entity that poses diagnostic and therapeutic challenges for clinicians. It accounts for 8%–26.5% of all cholecystoenteric fistulas (CEF), 1 , 2 , 3 making it the second most common type of CEF after cholecystoduodenal fistulas. The incidence of CCF in patients undergoing cholecystectomy is reported to be 0.06%–0.14%. 2 , 3 , 4

CCF usually occurs in the background of a gallbladder pathology, most commonly gallstones. 4 , 5 Other less common etiologies include surgery, 6 , 7 cholecystostomy, 1 , 8 abdominal wounds. 9 , 10 Herein, we report a case of cholecystocolonic fistula secondary to colonic diverticular disease.

Colonic diverticular disease/diverticulosis, a common gastrointestinal disorder predominantly affecting the elderly, is characterized by the presence of small pouch‐like protrusions, in the colonic wall. Pathogenesis of formation of cholecystocolonic fistula secondary to diverticular disease is attributed to diverticulitis which results in adhesions between the colon and adjacent structures. The inflammatory changes lead to necrosis of the colonic wall resulting in ulceration, perforation, and eventual fistula formation with the adjacent structure, such as urinary bladder, uterus, duodenum, and in our case gallbladder. 11

Cholecystocolonic fistulas are usually asymptomatic. However, when symptomatic, patients generally present with vague abdominal symptoms such as diarrhea, abdominal pain, jaundice, fever, nausea, vomiting, steatorrhea, and weight loss. 12

To date, no agreement could be established regarding the surgical management of asymptomatic cholecystocolonic fistula, especially in high‐risk patients. Asymptomatic patients may be managed conservatively to promote healing and eventual resolution of fistula once the inflammation subsides, which is what likely happened in our case. The other non‐surgical treatment option is sphincterotomy and CBD stent placement by ERCP, to reduce the pressure of the biliary system with spontaneous closure of the fistula. 13 However, there is a prevalent threat of biliary complications such as acute cholangitis, biliary peritonitis, and liver abscess in such cases. In severe cases, it may even lead to sepsis and death. 12

Despite its prevalence, the development of a cholecystocolonic fistula in the setting of diverticular disease remains a seldom‐reported occurrence in medical literature. To the best of our knowledge, two cases of CCF developing as sequelae of colonic pathologies have been reported. 14 , 15 One of these reported colonic diverticulosis as the etiological factor of CCF. 15

By reporting our experience, we aim to present a rare case of cholecystocolonic fistula secondary to diverticular disease of the ascending colon which resolved spontaneously, highlighting the clinical, radiological, and therapeutic aspects of this unique presentation.

2. CASE HISTORY

A 74‐year‐old male with diabetes mellitus, hypertension, and ischemic heart disease, presented as an outpatient to the ultrasound clinic of Aga Khan University Hospital, Karachi with the complaint of lower urinary tract symptoms.

2.1. Investigations and differential diagnosis

Ultrasound of kidneys and bladder was performed according to ACR guidelines which showed a soft tissue density polypoidal mass along the right lateral wall of the urinary bladder.

As part of the primary team's management plan, CT abdomen and pelvis with IV contrast was performed on a GE‐128 scanner with 5 mm of slice thickness and a window width of 400 HU. Approximately 90 mL of non‐ionic contrast was given. On CT imaging, there was a finding of a large polypoidal lesion arising from the base of the urinary bladder, indenting and possibly infiltrating the prostate.

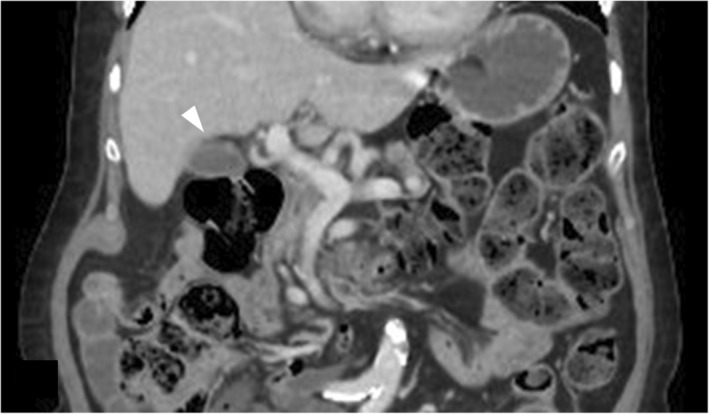

However, an additional finding of an abnormal linear air‐containing tract was identified arising from the ascending colon, extending up to the gallbladder. Another abnormal communication was noted in the region of fundus of the gallbladder with the adjacent hepatic flexure. Air was seen in the normally distended gallbladder (Figures 1, 2, 3). Two small fluid collections were also identified adjacent to the gallbladder fossa (Figures 4 and 5).

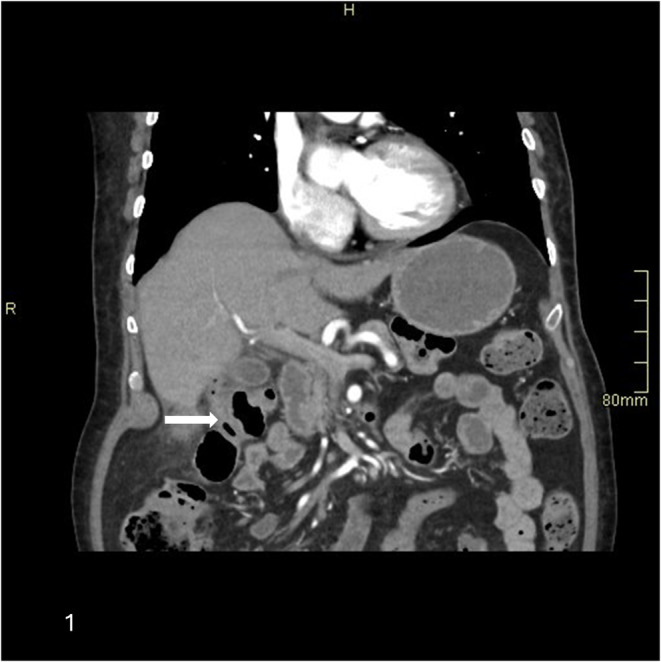

FIGURE 1.

Coronal section of CT abdomen with contrast porto‐venous phase shows a linear tract of air extending from the hepatic flexure up to the fundus of gall bladder (arrow)

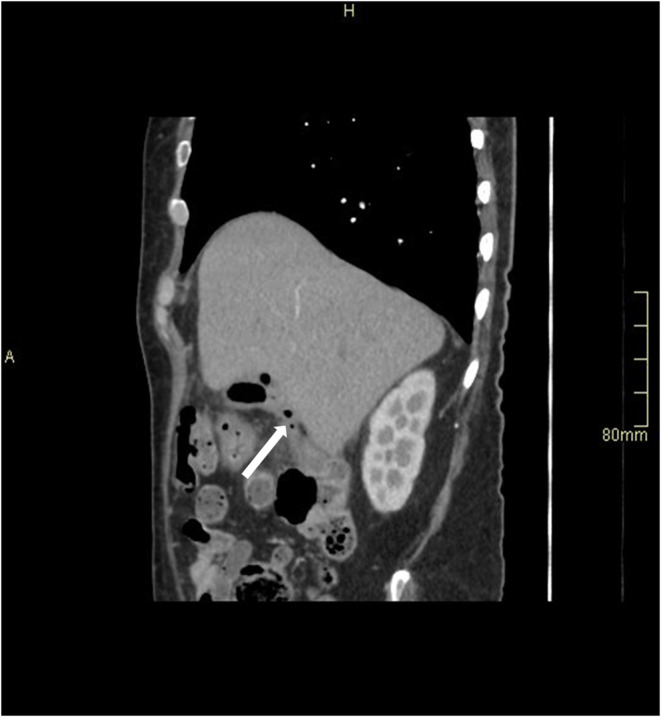

FIGURE 2.

Sagittal section of CT abdomen with contrast shows a linear tract of air extending from the hepatic flexure up to the fundus of gall bladder (arrow)

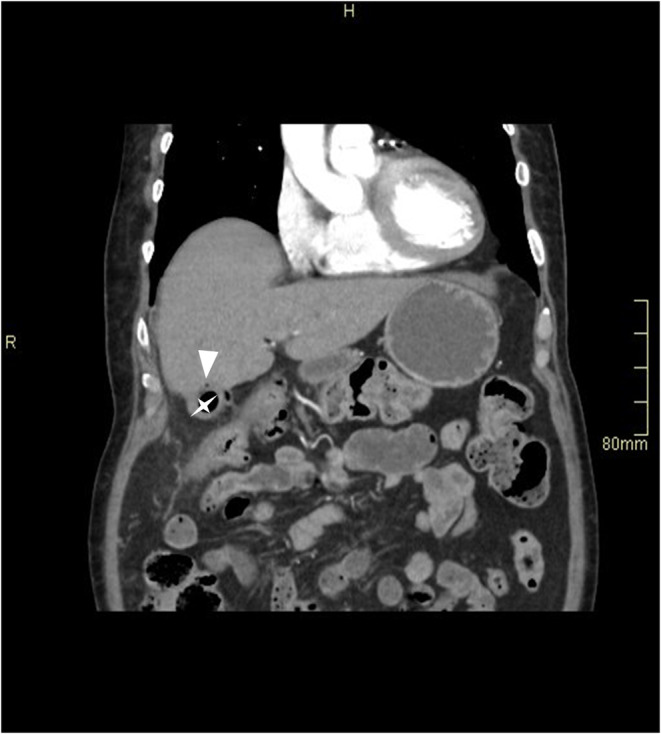

FIGURE 3.

A speck of air in the wall of the gallbladder fundus (arrowhead), indicating intramural air, with intraluminal air (star).

FIGURE 4.

CT abdomen with contrast shows a small collection lateral to the hepatic flexure (arrow) with ascending colon diverticula (arrow head).

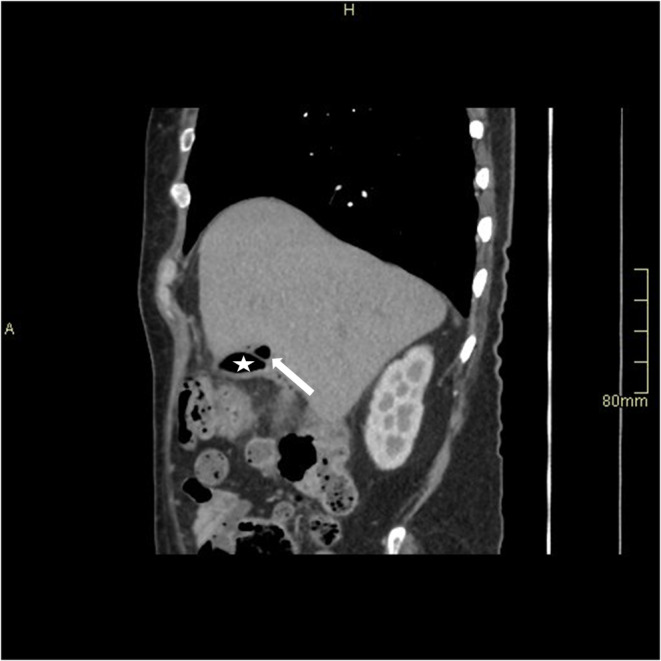

FIGURE 5.

Small pericholecystic collection containing air (arrow) (Star: gallbladder).

No gallstones were identified and the patient had no history of any invasive procedure related to the biliary system. There was no evidence of portal or intramural gas, small bowel obstruction, or calcific density within bowel loops to suggest gallstone ileus.

However, multiple tiny diverticulae were seen arising from the ascending colon (Figure 4).

Because of the presence of ascending colon diverticulosis and small collections and no evidence of cholelithiasis, cholecystitis, or prior gallbladder surgery, the presence of pneumobilia with cholecystocolonic fistulous communication was attributed to be resulting from ascending colon diverticulitis.

3. OUTCOME AND FOLLOW‐UP

The patient was then electively admitted to the hospital for cystoscopy and transurethral resection of the bladder tumor was planned.

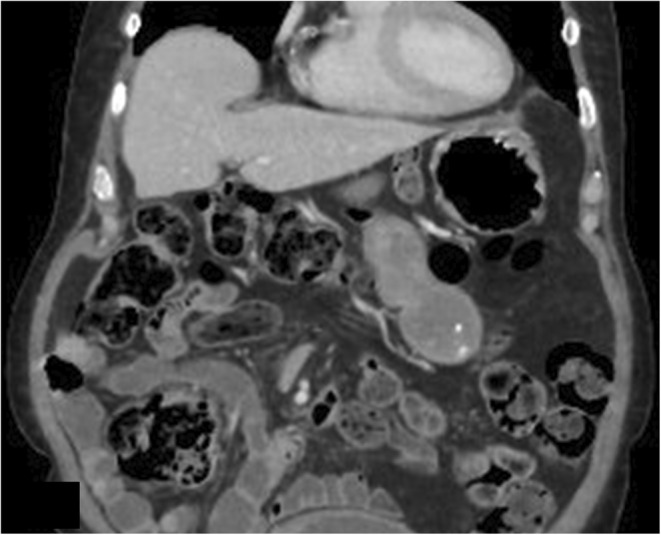

The patient was started on chemoradiotherapy for bladder carcinoma. However, since the patient did not complain of any related symptoms and had associated co‐morbid conditions, no intervention was done for the colo‐cholecystic fistula. Follow‐up CT a year later showed that the fistulous tract between the ascending colon and the biliary tree had healed, and air in the gallbladder lumen had resolved (Figures 6 and 7).

FIGURE 6.

Follow‐up CT abdomen with contrast after 1 year shows interval resolution of collection adjacent to the hepatic flexure and intraluminal air in gall bladder (arrow head).

FIGURE 7.

Follow‐up CT abdomen with contrast after 1 year shows interval resolution of collection adjacent to the hepatic flexure.

4. DISCUSSION

Cholecystocolonic fistula is a complex pathological entity often presenting with nonspecific symptoms, making its diagnosis challenging. While the majority of cases are attributed to gallstone disease or inflammatory bowel conditions, the association with diverticular disease is infrequently encountered. To the best of our knowledge, only a single such case has been documented in medical literature where the patient experienced fever and raised white cell counts, and subsequently had to undergo open cholecystectomy. 15 On the other hand, in our case, the fistulous communication was symptomless and discovered as an incidental finding. Furthermore, follow‐up imaging showed that the fistula had healed in intervals.

Since CCFs have no specific symptoms or signs, they are often overlooked unless complications occur. These complications include gallstone ileus, ascending cholangitis, or hemorrhage.

Common symptoms of CCFs include pain in the right upper quadrant, nausea, vomiting, and intolerance to fatty meals. These symptoms are characteristic of cholecystitis and are of no help in diagnosing CCF.

Diagnostic evaluation of cholecystocolonic fistula often necessitates preoperative and intraoperative evaluation. Preoperative diagnosis of CCF is challenging and is made in only 8% of the cases. 16

Imaging modalities that are sensitive and useful in preoperative diagnosis are ultrasound, barium enema, and contrast‐enhanced CT and MRI. Ultrasound may show thick‐walled and collapsed gallbladder, intraluminal air and pneumobilia. On CT and MRI examinations, presence of pneumobilia, which cannot be explained by prior biliary interventions, intraluminal air in gallbladder, ectopic gallstone in colon or thick‐walled shrunken gallbladder adherent to neighboring organs or direct communication of gallbladder with the adjacent colon suggests cholecystocolonic fistula. 6

However, ERCP is the most accurate modality for preoperative diagnosis of CCF. 16 , 17

Ibrahim et al. demonstrated intraoperative diagnosis of CCF by intraoperative cholecystography. 18

Therapeutic management of diagnosed and symptomatic colo‐cholecystic fistula primarily entails surgical intervention, aimed at cholecystectomy and colonic resection. 19 Laparoscopic techniques have gained prominence in recent years, offering the advantages of minimally invasive surgery, reduced postoperative pain, and shorter hospital stays. 6 However, the management of asymptomatic cholecystocolonic fistula is still uncertain and some authors advise non‐surgical approach and observation in such patients. A case of cholecystocolonic fistula secondary to gallstone ileus was reported by Ahmed et al in which the patient was treated conservatively due to his age and comorbidities and was followed upto 1 year without any evidence of residual or recurrent symptoms. 20 Nevertheless, the choice of approach should be tailored to individual patient factors, including the extent of disease involvement, presence of symptoms or complications, and patient risk factors.

5. CONCLUSION

Cholecystocolonic fistulas can occur secondary to various etiologies such as gallstones, recurrent cholecystitis, surgical or laparoscopic cholecystectomy, and trauma and can either remain asymptomatic or present with non‐specific symptoms such as vomiting, abdominal pain, and diarrhea. The diagnosis can be made preoperatively with the help of various imaging modalities or intraoperatively. Our report demonstrates colonic diverticular disease as a rare and possible etiology of cholecystocolonic fistula and a potential for non‐surgical approach for its management in asymptomatic patients with high risk factors, thereby optimizing patient outcomes. Further research endeavors are warranted to refine therapeutic strategies for this intriguing clinical entity.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Fatima Bhojani: Conceptualization; data curation; writing – original draft. Wasim Ahmed Memon: Conceptualization; supervision. Muhammad Nadeem Ahmad: Conceptualization; project administration; supervision; visualization. Mallick Muhammad Zohaib Uddin: Data curation; project administration; writing – original draft. Sibgha Khan: Writing – original draft. Naila Nadeem: Project administration; supervision. Faheemullah Khan: Project administration; supervision. Uffan Zafar: Conceptualization; data curation; project administration; supervision.

FUNDING INFORMATION

This medical case report received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not‐for‐profit sectors. The authors conducted this work independently without financial support.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this medical case report. No financial or personal relationships with individuals or organizations that could influence the content of this report are disclosed.

ETHICS STATEMENT

Patient confidentiality and informed consent were strictly adhered to throughout the documentation and publication of this medical case report, ensuring respect for the patient's autonomy and privacy rights.

CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient to publish this report in accordance with the journal's patient consent policy.

Bhojani F, Ahmed Memon W, Ahmad MN, et al. Cholecystocolonic fistula secondary to ascending colon diverticular disease: A case report. Clin Case Rep. 2024;12:e9405. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.9405

This work was conducted independent of any external influence, and the views expressed in this case report are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of their affiliated institutions.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy concerns. However, de‐identified data relevant to the case report may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

REFERENCES

- 1. Costi R, Randone B, Violi V, et al. Cholecystocolonic fistula: facts and myths. A review of the 231 published cases. J Hepato‐Biliary‐Pancreat Surg. 2009;16(1):8‐18. doi: 10.1007/s00534-008-0014-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Angrisani L, Corcione F, Tartaglia A, et al. Cholecystoenteric fistula (CF) is not a contraindication for laparoscopic surgery. Surg Endosc. 2001;15:1038‐1041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chowbey PK, Bandyopadhyay SK, Sharma A, Khullar R, Soni V, Baijal M. Laparoscopic management of cholecystoenteric fistulas. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2006;16:467‐472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Glenn F, Reed C, Grafe WR. Biliary enteric fistula. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1981;153:527‐531. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Paolucci V, Schaeff B, Schneider M, Gutt C. Tumor seeding following laparoscopy: international survey. World J Surg. 1999;23:989‐997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sing RF, Garberman SF, Frankel AM, Chatzinoff M. Cholecystocolic fistula: an unusual presentation and diagnosis by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography. Surg Endosc. 1990;4:39‐40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Wagtmans M, Kooy M, Snel P. Persistent diarrhoea in cholecystocolic and gastrocolic fistula after gastric surgery. Neth J Med. 1993;43:218‐221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hutchin P, Harrison TS, Halasz NA. Cholecystocolic fistula: a complication of cholecystostomy; with special reference to the management of cholecystostomy. Ann Surg. 1963;157:587‐590. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Griffith CD, Saunders JH. Cholecystoduodenocolic fistula following abdominal trauma. Br J Surg. 1982;69:99‐100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Ahn SI, Hong KC, Hur YS, et al. Cholecystocolic fistula caused by blunt trauma. Injury. 2001;32:341‐342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Patel A, Jahng A. S2545 management of cholecysto‐colonic fistula with ERCP with biliary stent placement. Off J Am College Gastroenterol. 2021;116:S1073. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Balent E, Plackett TP, Lin‐Hurtubise K. Cholecystocolonic fistula. Hawai'i J Med Public Health. 2012;71(6):155‐157. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Aguilar Rubio JL, Zamudio Martinez A, Zamudio MG. Cholecystocolonic fistula. Gen Surg Open A Open J. 2020;1:37‐39. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Menda RK, Chulani HL. Cholecystocolonic fistula following ameboma of the ascending colon: report of a case. Dis Colon Rectum. 1971;14:386‐388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Goenka P, Iqbal M, Manalo G, Youngberg GA, Thomas E. Colo‐cholecystic fistula: an unusual complication of colonic diverticular disease. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(9):2558‐2560. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1999.01396.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Manti F, Conti G, Battaglia C, et al. Cholecystocolonic fistula in exacerbated chronic cholecystitis: a case report. Radiol Case Rep. 2024;19(2):749‐752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Dutta U, Nagi B, Kumar A, Vaiphei K, Wig JD, Singh K. Pneumobilia—clue to an unusual cause of diarrhea. Trop Gastroenterol. 2002;23:138‐140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hession PR, Rawlinson J, Hall JR, Keating JP, Guyer PB. The clinical and radiological features of cholecystocolic fistulae. Br J Radiol. 1996;69:804‐809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. I131–rose bengal scanning in the detection of cholecystocolic fistula. New use of an established procedure. Am J Gastroenterol. 1977;68:396‐398. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. AlMuhsin AM, Bazuhair A, AlKhlaiwy O, Abu Hajar RO, Alotaibi T. Non‐operative management of gallstone sigmoid ileus in a patient with a prostatic cancer. J Surg Case Rep. 2023;2023(6):rjad331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and analyzed during the current study are not publicly available due to patient privacy concerns. However, de‐identified data relevant to the case report may be available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.