Abstract

Woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV) and human hepatitis B virus are closely related, highly hepatotropic mammalian DNA viruses that also replicate in the lymphatic system. The infectivity and pathogenicity of hepadnaviruses propagating in lymphoid cells are under debate. In this study, hepato- and lymphotropism of WHV produced by naturally infected lymphoid cells was examined in specifically established woodchuck hepatocyte and lymphoid cell cultures and coculture systems, and virus pathogenicity was tested in susceptible animals. Applying PCR-based assays discriminating between the total pool of WHV genomes and covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA), combined with enzymatic elimination of extracellular viral sequences potentially associated with the cell surface, our study documents that virus replicating in woodchuck lymphoid cells is infectious to homologous hepatocytes and lymphoid cells in vitro. The productive replication of WHV from lymphoid cells in cultured hepatocytes was evidenced by the appearance of virus-specific DNA, cccDNA, and antigens, transmissibility of the virus through multiple passages in hepatocyte cultures, and the ability of the passaged virus to infect virus-naive animals. The data also revealed that WHV from lymphoid cells can initiate classical acute viral hepatitis in susceptible animals, albeit small quantities (∼103 virions) caused immunovirologically undetectable (occult) WHV infection that engaged the lymphatic system but not the liver. Our results provide direct in vitro and in vivo evidence that lymphoid cells in the infected host support propagation of infectious hepadnavirus that has the potential to induce hepatitis. They also emphasize a principal role of the lymphatic system in the maintenance and dissemination of hepadnavirus infection, particularly when infection is induced by low virus doses.

The hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a 3.2-kb, noncytopathic DNA virus that induces chronic hepatitis in approximately 5% of the global population and is the most common infectious cause of hepatocellular carcinoma (15, 26). Infection with the closely related woodchuck hepatitis virus (WHV) in the eastern American woodchuck (Marmota monax) has been validated as a valuable virologic and pathogenic model of HBV infection (17, 37). Although liver inflammation is the paramount pathological consequence of HBV and WHV infections and hepatocytes are the site of the most active hepadnaviral replication, both viruses also invade the host lymphatic system. HBV DNA, including replicative intermediates and covalently closed circular DNA (cccDNA), as well as virus RNA transcripts and DNA sequences integrated with the cellular genome, have been detected in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) from patients with active chronic hepatitis B (13, 29, 30, 34). Small amounts of HBV genomes have also been found in circulating lymphoid cells years after recovery from an acute episode of hepatitis B (23, 32). Studies in WHV-infected woodchucks provided even more persuasive evidence that the lymphatic system is invariably involved from the earliest stages of either symptomatic or serologically undetectable (silent) infection and is the site of life-long persistence of small amounts of pathogenic virus after resolution of hepatitis (4, 20, 22; reviewed in reference 18). It has also been documented that under certain natural conditions, i.e., in offspring born to mothers recovered from WHV hepatitis (4) or in particular experimental situations, e.g., infection of adult animals with low WHV doses (22; C. S. Coffin, P. M. Mulrooney, and T. I. Michalak, unpublished data), virus expression can be essentially confined to the lymphatic system. Although the importance of this extrahepatic site of replication for the long-term persistence of hepadnavirus becomes increasingly evident (reviewed in reference 18), the intrinsic ability of lymphotropic WHV to infect host hepatocytes and to induce liver disease as well as to invade virus-naive lymphoid cells has not yet been examined. These issues are of direct clinical relevance, since there is well-documented evidence of extrahepatic HBV persistence and prompt reinfection of donor hepatic tissue after liver transplantation in chronically infected individuals (5, 7, 12, 14, 16, 28). Furthermore, HBV infection of lymphoid cells may have a detrimental effect on a variety of host immune responses and contribute to both the establishment and the continuance of virus persistence. In this regard, we have recently shown that chronic WHV infection is associated with profound inhibition of class I major histocompatibility complex (MHC) presentation not only on hepatocytes but also on lymphoid cells (20). Impairment of class I MHC-dependent functions of the immune system could be one of the major mechanisms by which hepadnavirus compromises antiviral immunological surveillance and persists in the host.

In the present study, we investigated hepato- and lymphotropism and tested the pathobiological characteristics of WHV produced by naturally infected lymphoid cells. For this purpose, woodchuck hepatocyte and lymphoid cell cultures susceptible to WHV and lymphoid cell-hepatocyte and lymphoid cell-lymphoid cell coculture systems were established. In addition, PCR assays discriminating between the total pool of WHV DNA and that of covalently closed viral DNA were adopted to assess viral expression and replication in the infected cells. Viral cccDNA was examined as an indicator of active virus replication based on the postulate that its formation is the initial step in the hepadnaviral propagation cycle and, therefore, a marker of actually progressing replication (27, 36, 40).

The WHV DNA amplification assays were done using DNA extracted from cells subjected to DNase and limited proteolytic digestions to eliminate possible cell surface-adsorbed extracellular viral sequences. Production of infectious WHV by lymphoid cells and its pathogenic potential were examined by serial passages of the virus in cultured hepatocytes, coculture of the infected cells with virus-naive hepatocytes or lymphoid cells, and inoculation of naive animals. Our results provide direct in vitro and in vivo evidence that WHV propagating in naturally infected lymphoid cells is infectious to both hepatocytes and lymphoid cells and is able to transmit infection to virus-naive animals. In susceptible woodchucks, the lymphoid cell-derived virus can induce classical viral hepatitis, although at small doses it causes serologically undetectable infection that involves the lymphatic system but not the liver.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell isolation and cultures.

Splenocytes, containing mostly lymphocytes, and PBMC from woodchucks with serologically and histologically confirmed chronic WHV hepatitis were isolated on Ficoll-Paque (Pharmacia Biotech, Baie d'Urfé, Qubec, Canada) gradients by methods described previously (8, 19). In all instances, the cells were depleted of residual erythrocytes with 0.83% NH4Cl, extensively washed with sterile phosphate-buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.4) with 1 mM EDTA, suspended in Hanks' balanced salt solution (HBSS), and digested with DNase, trypsin, and again with DNase to eliminate WHV particles and free viral DNA fragments possibly attached to their surface. This digestion (referred to as DNase/trypsin/DNase treatment or surface enzymatic treatment) was done according to a previously published procedure (4, 22) with modifications. For this purpose, approximately 3 × 107 cells in 2 ml of HBSS were supplemented with 200 μl of DNase digestion buffer (100 mM MgCl2 in 500 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0]) and 20 μl of DNase (1 μg/μl; activity, 2 U/μg; DNase I; type IV from bovine pancreas; Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, Mo.) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h in a tissue culture incubator. Subsequently, the cells were treated with 10 μl of trypsin (10 mg/ml; activity, 7,300 U/mg; type XI from bovine pancreas; Sigma Chemical Co.) in the presence of 20 μl of 0.1 M CaCl2 for 30 min on ice. The reaction was terminated with 20 μl of trypsin inhibitor (10 μg/ml; type II-O from chicken egg white; Sigma Chemical Co.). In the following step, DNase treatment was repeated under the conditions described above to eliminate WHV DNA possibly released from extracellular virions. The cells were washed twice with a total of 20 ml of PBS with 1 mM EDTA by centrifugation at 330 × g for 5 min. The final wash and 2 × 106 treated cells were saved for WHV DNA analysis by specific PCR and Southern blot hybridization. The remaining cells were immediately suspended in hepatocyte culture medium (described below) and cultured in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2. It was found that the lymphoid cells can be maintained in a hepatocyte culture medium for up to 4 days without noticeable changes in their viability and WHV content. PBMC were also isolated from WHV-naive, healthy woodchucks and used in coculture infection experiments (see below).

Woodchuck hepatocyte line WCM-260 was established from hepatocytes isolated by two-step collagenase microperfusion of a liver biopsy obtained from an adult, healthy animal. This line was characterized in detail in our previous study (6). Briefly, WCM-260 cells were propagated in gelatin-coated flasks in a hepatocyte culture medium consisting of 80% (vol/vol) Hepato-STIM medium with 10 μM dexamethasone (Becton Dickinson, Bedford, Mass.) and 20% (vol/vol) HepG2 cell culture supernatant. The medium was supplemented with epidermal growth factor (10 ng/ml; Becton Dickinson), l-glutamine (2 mM), penicillin (50 μg/ml), and streptomycin (50 μg/ml). The WCM-260 cells demonstrated stable growth and consistent morphology and transcribed asialoglycoprotein receptor mRNA when passaged at weekly intervals for more than 3 years. For the majority of experiments, the cells were grown to a large quantity, harvested by treating the monolayer with 0.25% trypsin and 1 mM EDTA (Gibco-BRL, Grand Island, N.Y.), suspended in heat-inactivated fetal calf serum with 10% dimethyl sulfoxide at 9 × 105 cells/ml, and frozen in liquid nitrogen. Prior to an experiment, hepatocytes were thawed, washed, and grown to confluence. They were then collected, counted, and seeded 24 h before exposure to virus.

Lymphoid cell- and serum-derived WHV inocula.

Three types of WHV inocula were prepared and tested in this study. They were derived from naturally infected PBMC or splenocytes or from sera of WHV surface antigen (WHsAg)-positive animals with histologically evident chronic viral hepatitis (Table 1). WHV originating from lymphoid cells was prepared by culture of PBMC or splenocytes at 2 × 106 cells/ml for 72 h in hepatocyte medium and passage of the resulting culture supernatants through 0.2-μm-pore-size syringe filters (Gelman Sciences, Ann Arbor, Mich.). Serum-derived WHV was obtained by diluting sera with hepatocyte culture medium and filtration through 0.2-μm filters. The final filtrates were used as sources of virus for infection of either WCM-260 hepatocytes or virus-naive lymphoid cells.

TABLE 1.

Expression of WHV-specific DNA, cccDNA, and antigens in WCM-260 woodchuck hepatocytes infected with different WHV inocula derived from serum or lymphoid cells

| Source of WHV inoculum | Expt no. | WHV in inoculum (VGE/ml)a | WHV genome expression

|

% WHV antigenpositive cellsb

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DNA | cccDNA | WHsAg | WHcAg | |||

| Serum | 1 | 7.2 × 108 | + | + | 0 | 0 |

| 2 | 1.2 × 109 | + | + | 53 | 0 | |

| 3 | 8.4 × 108 | + | − | 0 | 16 | |

| 4 | 4 × 106 | + | − | 0 | 0 | |

| 5 | 1.4 × 108 | + | − | 0 | 0 | |

| 6 | 1.4 × 108 | + | + | 0 | 13 | |

| Totalsc | 6/6 | 3/6 | 1/6 | 2/6 | ||

| PBMC culture supernatantd | 7 | 3 × 103 | + | − | 0 | 0 |

| 8 | 3 × 104 | + | − | 20 | 0 | |

| 9 | 3 × 104 | + | − | 0 | 19 | |

| 10 | 3 × 104 | + | + | 0 | 20 | |

| Totals | 4/4 | 1/4 | 1/4 | 2/4 | ||

| Splenocyte culture supernatantd | 11 | 1.9 × 107 | + | + | 26 | 0 |

| 12 | 2 × 107 | + | − | 0 | 0 | |

| 13 | 2 × 107 | + | + | 0 | 0 | |

| 14 | 2 × 107 | + | + | 0 | 26 | |

| Totals | 4/4 | 3/4 | 1/4 | 1/4 | ||

| Totals | 14/14 | 7/14 | 3/14 | 5/14 | ||

WHV VGE evaluated by dot-blot hybridization (sensitivity, 106 VGE/dot) in serum and splenocyte inocula and by direct PCR/Southern blot analysis (sensitivity, 103 VGE/ml) in PBMC inocula.

Represents % of tested hepatocytes with fluorescence greater by 10% than control cell population.

Totals represent number positive/number tested.

Collected after 72-h culture of cells seeded at 2 × 106/ml.

To differentiate between WHV virions and free (envelope unprotected) WHV DNA-reactive molecules, samples of selected inocula were assayed for virus DNA content before and after digestion with DNase. The treatment was done following the method previously described (4). Briefly, 100 μl of inoculum was supplemented with 10 μl of DNase digestion buffer and 40 U of DNase (both described above) and incubated at 37°C for 1 h. Digestion was repeated three times. Recombinant, full-length WHV DNA (2 μg) suspended in normal woodchuck serum was used as a digestion control. Finally, DNA was extracted by a standard proteinase K-phenol-chloroform method and evaluated for WHV DNA by specific PCR and Southern blot hybridization, as indicated below.

Infection of cultured hepatocytes with WHV.

WCM-260 hepatocytes were seeded 24 h prior to infection at 1.2 × 104 cells/cm2 onto gelatin-coated 25-cm2 tissue culture flasks (Corning Costar Corp., Cambridge, Mass.) in 5 ml of hepatocyte culture medium. In the next step, medium was replaced with WHV inocula at a volume of 200 μl/cm2 of vessel surface and incubated with the hepatocytes for 24 h at 37°C in a humidified CO2 atmosphere. The culture medium with inoculum was then removed, hepatocytes were washed twice with HBSS, and 5 ml of fresh hepatocyte culture medium was added. The cells were allowed to grow for 3 more days and then harvested by trypsinization. In all experiments, hepatocytes destined for DNA isolation were treated with DNase/trypsin/DNase (as described for lymphoid cells) and washed in two 10-ml changes of HBSS. The final wash was saved for WHV DNA analysis by PCR and Southern blot hybridization to assess whether extracellular virus material was removed from the surface of the cultured cells analyzed. In some experiments, the collected cells were divided into two equal parts. One part was washed, surface treated with enzymes, and used for DNA extraction. The second part was examined for expression of WHV antigens by flow cytometry. In selected cases, supernatant recovered from hepatocyte cultures at day 3 postinoculation (p.i.) was ultracentrifuged at 200,000 × g for 18 h in an SW50.1 rotor (Beckman Instruments Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.), and the pellet was suspended in 100 μl of sterile PBS. Then, DNA was extracted and assayed for WHV DNA, as presented below.

Multiple passages of WHV from lymphoid cells in hepatocyte cultures.

WCM-260 cells were exposed under conditions outlined above to WHV at 3 × 104 virus genome equivalents (VGE)/ml produced by naturally infected PBMC (experiment 9 in Table 1) or 2 × 107 VGE/ml from splenocytes (experiment 14 in Table 1). Subsequently, 5-ml volumes of hepatocyte culture supernatants collected at day 3 p.i. from these hepatocyte cultures were transferred to naive WCM-260 cells seeded 24 h prior to passage. After 24 h of incubation, medium was removed, and hepatocytes were washed with HBSS and supplemented with 5 ml of fresh hepatocyte culture medium. The cells were cultured for an additional 3 days under standard conditions. The resulting culture supernatant was collected, hepatocytes were harvested, washed, and surface treated with enzymes, and DNA was extracted. The recovered culture supernatant was transferred to newly established 24-h WCM-260 cell culture using the approach described above. This procedure was repeated five consecutive times. The culture media after the final (sixth) hepatocyte passage from each of the experiments (i.e., experiments 9A and 14A) were separately spun down at 200,000 × g for 18 h in a Beckman SW50.1 rotor, and each pellet was suspended in 1 ml of sterile PBS. One hundred microliters of each suspension was assayed for WHV VGE content, and the remaining portion was injected intravenously into a WHV-naive woodchuck (see below).

Infection of cultured lymphoid cells with lymphoid cell-derived WHV.

For in vitro infection of lymphoid cells, approx. 107 PBMC from a healthy woodchuck were incubated with 5 ml of culture supernatant containing 2 × 107 WHV VGE/ml derived from naturally infected splenocytes. The inoculum was removed after 24 h by centrifugation at 330 × g for 10 min. The target cells were washed with 10 ml of HBSS, supplemented with fresh medium, and cultured for an additional 72 h. At day 4 p.i., lymphoid cells were harvested, washed, and surface treated with enzymes, and DNA was extracted and analyzed for WHV DNA and cccDNA expression.

Hepatocyte and lymphoid cell cocultures.

To determine whether WHV from lymphoid cells can directly infect homologous hepatocytes or lymphoid cells, lymphoid cell-hepatocyte and lymphoid cell-lymphoid cell coculture systems were established. The cocultures were set up in 12-well plates with permeable 0.4-μm-pore-size membrane inserts (Becton Dickinson Labware, Bedford, Mass.). All cocultured cells were maintained in hepatocyte culture medium, permitting measurements of WHV infectivity under comparable conditions. For cocultures of WHV-infected splenocytes with virus-naive hepatocytes, WCM-260 cells were seeded 24 h before the experiment at 1.2 × 104 cells/cm2 in gelatin-coated wells. When virus-naive lymphoid cells were used as targets, PBMC from a healthy woodchuck were placed at 106 cells/well in the 12-well plates 2 h prior to coculture. Then, 106 surface DNase/trypsin/DNase-treated splenocytes from a chronic WHV carrier in 1 ml of hepatocyte culture medium were placed in each permeable insert submerged in 1 ml of hepatocyte medium covering the target cells seeded in the companion well. As negative controls, WCM-260 cells or lymphoid cells in 2 ml of hepatocyte medium which were not exposed to WHV were cultured in parallel. Each coculture and control cells were set up in triplicate and incubated for 4 days. Then, the splenocytes were collected and inserts were removed. Target cells were harvested by either trypsinization (hepatocytes) or gentle scraping (lymphoid cells), washed in HBSS, and surface enzyme treated prior to DNA extraction.

Infection of woodchucks with lymphoid cell-derived WHV.

The in vivo infectivity of WHV secreted by lymphoid cells was examined in WHV-naive woodchucks in two independent trials. In the first trial, WHV produced by naturally infected PBMC or splenocytes during a 72-h culture and then serially passaged in WCM-260 hepatocytes (experiments 9A and 14A, respectively) was intravenously injected at 1.3 × 103 VGE and 7.8 × 103 VGE into animals WM.1 and WM.2, respectively. Serum and PBMC samples were collected prior to inoculation, at days 3 and 7 p.i., and then weekly up to 20 weeks p.i. for animal WM.1 and 10 wks p.i. for WM.2. In the next step, both animals were challenged by intravenous injection with 1.1 × 1010 DNase-protected WHV VGE, exactly as described in our previous studies (4, 22). Sera and PBMC were collected at days 3 and 7, weekly until 6 weeks after challenge, and then biweekly. Follow-up of these animals ceased at 5.5 months after challenge with WHV. Sera were assayed for WHsAg, antibodies to WHsAg (anti-WHs) and antibodies to WHV core antigen (anti-WHc) using immunoassays described previously (21, 22). WHV DNA was tested in sera and PBMC by dot-blot hybridization or, if required, by PCR and Southern blot hybridization assays applying methods outlined below. Liver biopsies were obtained by laparotomy at 6 weeks p.i. and at 6 weeks after WHV challenge. Hepatic tissue was evaluated for WHV genome expression and by histology.

In the second trial, the in vivo infectivity and pathogenic competence of equal amounts of WHV derived from splenocytes or serum of the same chronic WHV carrier were examined. Thus, woodchuck WF.3 was intravenously injected with 4.8 × 106 DNase-protected WHV VGE produced during a 72-h culture by splenic lymphoid cells which were treated with DNase/trypsin/DNase prior to culture. Of note is that the same splenocyte culture supernatant was also used to infect WCM-260 hepatocytes in experiment 14 and to infect woodchuck WM.2. after serial passage of virus in WCM-260 cells in experiment 14A. In parallel, animal WM.4 was inoculated by the same route with 4.8 × 106 DNase-protected VGE prepared from the serum of the WHV carrier that provided the splenocytes. Blood samples from animals WF.3 and WM.4 were collected by venipuncture up to approximately 9 months p.i. Liver biopsies were obtained by laparotomy before the experiment, at 6 and 24 weeks p.i., and at the end of follow-up. Sera were analyzed for immunological markers of WHV infection, and serum, PBMC, and liver samples were analyzed for WHV DNA. Liver tissue sections were also examined by histology using criteria described in our previous works (21, 22).

Detection of WHV DNA and cccDNA.

WHV DNA content in sera, lymphoid cell, hepatocyte culture supernatants, and cell washes was determined, in the first instance, by a dot-blot hybridization assay using 32P-labeled complete, recombinant, linearized WHV (rWHV) DNA as a probe (29). This assay was carried out according to a previously published method (4) and was followed by densitometric quantitation of hybridization signals using twofold serial dilutions of rWHV DNA as the reference and a Cyclone phosphorimaging system (Canberra-Packard Canada Ltd., Mississauga, Ontario, Canada). The estimated sensitivity of this assay was 2 × 106 WHV VGE/ml. In the case of a negative result, WHV DNA was examined by direct or, if required, nested PCR followed by Southern blot analysis of the amplified products (see below).

In some instances, viral DNA was separated from cellular DNA using KCl precipitation to obtain cccDNA-enriched fractions. This DNA isolation was performed following a procedure described by others (42). Briefly, 100-mg samples of hepatic or splenic tissue from several animals chronically infected with WHV were treated with lysis solution (0.5% [wt/vol] sodium dodecyl sulfate, 10 mM EDTA in 10 mM Tris-HCl buffer [pH 7.5]) followed by addition of KCl to a final concentration of 0.5 M. After 30 min at ambient temperature, the precipitate was removed by centrifugation, the supernatant was extracted twice with phenol and once with chloroform, and the DNA was precipitated with ethanol. DNA samples (10 μg) were then subjected to electrophoresis in 1% agarose, transferred onto a nylon membrane (Hybond-N; Amersham, Oakville, Ontario, Canada), and analyzed by Southern blotting with 32P-labeled rWHV DNA. We have found that cccDNA with an electrophoretical mobility of 2.3 kb could be identified only in hepatic tissues with WHV DNA content equal or greater than 107 VGE/μg of liver DNA. Virus cccDNA signals were not detected in livers with virus DNA levels of 106 VGE/μg or in any spleen sample tested, even in those from animals with serum WHV loads reaching 1011 VGE/ml. This finding implied that the above method was not suitable for detection of cccDNA in lymphoid cells or in vitro-infected WCM-260 hepatocytes because of its low sensitivity. Post factum, this finding was not completely surprising, since the WHV DNA levels in splenic tissue normally do not exceed 106 VGE/μg of DNA even in highly viremic animals (20) and the estimated levels of cccDNA in lymphoid cells are at least 10- to 100-fold lower than those of total WHV DNA.

For PCR amplifications, DNA was extracted from lymphoid cells or hepatocytes and tissue samples and from 100 μl of test aliquots by proteinase K digestion and phenol-chloroform protocol (35). For standard PCR detection of WHV DNA, DNA from 100 μl of cell culture supernatants, cell washes, or sera and 1 μg of DNA from PBMC or liver biopsies collected from woodchucks inoculated with test inocula were amplified using direct or nested pairs of oligonucleotide primers specific for WHV core, surface, and X gene sequences and amplification conditions described previously (4, 22). This was followed by Southern blot analysis of the amplified products. The resulting hybridization signals were quantitated by densitometry against known concentrations of rWHV DNA used as standards. The sensitivity of the direct and nested PCR amplifications employing different WHV primer pairs was 103 and between 10 and 102 VGE/ml, respectively (22).

To strengthen the distinction between WHV cccDNA (uninterrupted molecules) and relaxed circular WHV DNA (interrupted molecules having a single-stranded nick region), total DNA isolated from naturally infected lymphoid cells and from in vitro-infected hepatocytes or PBMC was subjected to digestion with a single-strand-specific nuclease to eliminate interrupted molecules. This treatment was performed using mung bean nuclease in a volume of 20 μl containing 5 μg of DNA in the presence of 2 μl of 10× digestion buffer (500 mM NaCl, 10 mM l-cysteine, 100 mM sodium acetate, 1 mM zinc acetate [pH 5.0] with 50% [vol/vol] glycerol; Gibco-BRL) and 40 U of enzyme (Gibco-BRL) for 30 min at 37°C according to a previously reported procedure (34). The reaction was terminated by the addition of 3 μl of 0.1 M EDTA. The efficiency of the nuclease digestion was ascertained by treatment of heat-denatured double-stranded rWHV DNA under conditions identical to those described above. The result showed that the digested DNA could not be amplified by nested PCR with primers specific for either individual WHV genes or the nick region (data not shown), whereas that not treated was readily detectable (see Fig. 1).

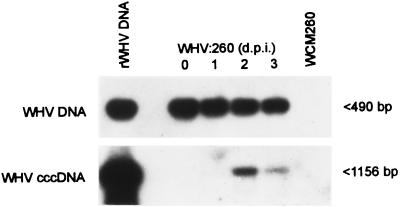

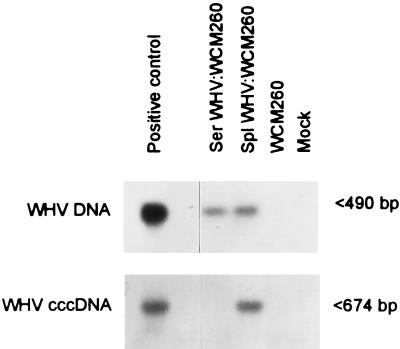

FIG. 1.

Time course of appearance and expression of WHV DNA and cccDNA in cultured woodchuck hepatocytes infected in vitro with WHV. WCM-260 hepatocytes were incubated for 24 h with woodchuck serum containing 107 WHV VGE/ml. Cells were harvested at the indicated days postinoculation (d.p.i.), washed, surface treated with DNase/trypsin/DNase, and washed again. The extracted DNA was digested with mung bean nuclease and analyzed for WHV DNA and cccDNA by a differential PCR protocol described under Materials and Methods. rWHV DNA was included as a positive control, and mung bean nuclease-digested DNA from virus-naive WCM-260 hepatocytes was used as a negative control. The amplified direct PCR products were detected by Southern blot hybridization to an rWHV DNA probe. Positive samples show the expected sizes of nucleotide fragments noted by arrowheads.

For PCR amplifications differentiating between whole (total) WHV DNA (i.e., both interrupted and cccDNA molecules) and cccDNA, two sets of WHV genome-specific primers were designed using an approach verified for HBV by others (34). The whole WHV DNA was amplified with sense primer PCOR1 (5′-TGTGTTCCATGTCCTACTGTTCAAGCC, 1964 to 1990; numbers denote the position of the sequence in the WHV genome according to GenBank accession no. M11082) and antisense primer MCOR (5′-CCGGAAGAGTCGAGAGAATGGGTGC, 2453 to 2429). For nested PCR amplification, if needed, primers PPCC (22) and CCCV (5′-GTCCCCAGGTGTCAGTGACA, 2303 to 2284) were employed. In a parallel reaction, sense primer PGAP1 (5′-TGGTGTGCTCTGTGTTTGCTGACGC, 1298 to 1322) and antisense primer MCOR were used to amplify the WHV cccDNA sequence. If required, the direct PCR product was amplified by a nested reaction with sense primer XINT (5′-CTTCGCCTTCGCCCTCAGACGAGT, 1630 to 1653) and antisense primer CCCV to detect WHV cccDNA. Amplification of whole WHV DNA and cccDNA sequences was done under identical PCR conditions using 10 μl of mung bean nuclease-digested DNA for direct PCR. In preliminary experiments, it was established that the amplification mixture of the first-round PCR has to contain 3 mM MgCl2 to overcome the inhibitory effect of EDTA, used for inactivation of the nuclease. Each reaction was run in a 100-μl volume using the following thermocycling conditions: one cycle of 95°C for 5 min, 56 °C for 2 min, and 72°C for 3 min, followed by 30 cycles of 95°C for 1 min, 56°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min, and finally, an elongation step at 72°C for 15 min. DNA extracted from the liver of a chronic WHV carrier treated with mung bean nuclease and 50 fg of double-stranded rWHV DNA were used as positive controls. As an additional control for the specificity of cccDNA detection, DNA isolated from the WHV inoculum produced by cultured chronically infected splenocytes, which contained WHV at 2 × 107 VGE/ml and was infectious to WCM-260 hepatocytes (experiment 14, Table 1), was first digested with mung bean nuclease and then amplified by a differential PCR protocol. In all PCR runs, a mock sample extracted in parallel with the test DNA and containing all reagents except DNA as well as appropriate contamination controls was included (4, 22). For nested PCR, 10 μl of the direct PCR mixture was amplified in the presence of 1.5 mM MgCl2, and thermocycling was conducted as described for the first PCR round. Southern blot analysis was used to verify the specificity of the amplified WHV DNA fragments and validity of controls. For this purpose, 20 μl of direct or nested PCR mixture was electrophoresed on a 1% agarose gel, and DNA was transferred onto a nylon membrane and hybridized with a 32P-labeled rWHV DNA probe (4). The approximate sensitivity of the direct PCR and Southern blot hybridization assay for detection of total WHV DNA and WHV cccDNA was 3 × 102 and 3 × 103 VGE/ml, respectively. Nested PCR followed by Southern blotting improved detection of the amplified signals by 10- to 100-fold.

The specificity of the amplified WHV DNA and cccDNA fragments was also confirmed by sequencing of randomly selected PCOR1-MCOR (total WHV DNA) and PGAP1-MCOR (cccDNA) amplicons. For this purpose, PCR products were sequenced with the use of the fmol DNA sequencing system (Promega Corp.) and 32P-labeled primers QX12 (5′-GGCATGCCAAGTAAGGACC, 1791 to 1809) and QC02 (5′-CTCGGATCCCTATAAAGAATTTGG, 2026 to 2049). The data obtained showed that the amplified WHV cccDNA sequences encompassed a nucleotide fragment complementing the nicked WHV region and were identical to those reported by others (10).

Detection of WHV antigens.

Approximately 106 WCM-260 hepatocytes which had been exposed to test WHV inocula and harvested at day 4 p.i. were exposed to rabbit anti-WHs or rabbit anti-WHc antibodies for 20 min on ice. Cells were washed in HBSS by pelleting at 45 × g for 5 min at 4°C and stained for 20 min on ice with goat anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG; heavy and light chains) conjugated to fluorescein isothiocyanate (Organon Teknika Cappel, Durham, N.C.). After washing, hepatocytes were fixed in 1% (wt/vol) paraformaldehyde and analyzed with a FACStar-Plus flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson, Palo Alto, Calif.). Virus-naive and WHV-exposed WCM-260 cells, unstained, exposed to secondary antibody alone or to rabbit preimmune sera, and then stained with secondary antibody, were used as controls. Flow cytometry results were analyzed with CellQuest software (Becton Dickinson). Histograms of the test hepatocytes were overlaid on those of negative controls (i.e., naive hepatocytes stained with the same antibodies), and the number of events under the curve in non-overlapping areas was gated, counted, and expressed as a percentage of the total number of events detected in the test sample. Values equal to or greater than 10% were considered positive.

RESULTS

Features of WHV infection in primary lymphoid cell cultures.

Splenic and peripheral lymphoid cells isolated from animals with serum WHsAg-positive, chronic viral hepatitis consistently displayed WHV DNA and cccDNA using PCR-based detection methods. Analyzed splenocytes demonstrated 10- to 100-fold-greater levels of virus DNA and cccDNA than those encountered in comparable numbers of peripheral lymphoid cells. These naturally infected cells survived in hepatocyte culture medium for up 4 days without alterations in their viability and intracellular WHV content. The levels of WHV genome expression remained constant during this time period and comparable to those detected in the freshly isolated cells (data not shown). To exclude the possibility that detection of cellular WHV-specific nucleic acid signals in freshly isolated or cultured lymphoid cells might be compromised by DNA from surface-attached virions or virus DNA fragments, the lymphoid cells were treated with DNase/trypsin/DNase and extensively washed prior to DNA extraction. Examination of the last cell washes did not reveal WHV DNA reactivity, implying the absence or complete removal of the possible extracellular viral material. It was further observed that WHV genome expression in lymphoid cells decreased if the culture progressed for longer than 4 days. This event was associated with a rapid decrease in cell survival and was neither virus nor medium related, since both virus-naive and WHV-infected PBMC survived to the same extent in either hepatocyte culture medium or RPMI 1640 medium that was used for lymphoid cell cultures in our previous studies (4, 8). It was also noticed that the level of WHV expression and the rate of lymphoid cell survival in hepatocyte medium were not enhanced in the presence of mitogens, such as phytohemaglutinin (PHA; 5 μg/ml) or lipopolysaccharide (LPS; 10μg/ml) (data not shown). Overall, the results revealed that conditions designed for culture of woodchuck hepatocytes were also adequate for maintenance of lymphoid cells and that they supported the transiently steady level of WHV replication in these cells.

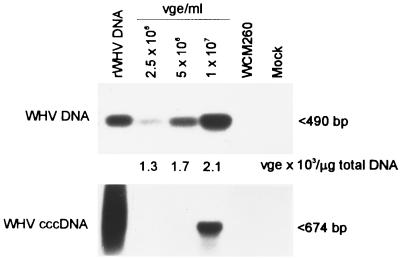

Cultured woodchuck hepatocytes support a complete cycle of WHV replication.

WCM-260 hepatocytes exposed to WHV inocula and harvested daily prior to reaching confluence expressed WHV DNA from the moment of the completion of the 24-h incubation with virus (i.e., day 0 p.i.) and viral cccDNA typically from day 2 p.i. (Fig. 1). DNA from WCM-260 cells not exposed to virus, and the final washes from the infected, surface-treated WCM-260 did not show WHV DNA reactivity. Densitometric analysis of hybridization signals demonstrated that the levels of intracellular WHV DNA remained essentially constant between days 0 and 3 p.i. in hepatocytes exposed to 107 VGE/ml, whereas the virus cccDNA level was highest at day 2 p.i. and then decreased. It was also found that the degree of WHV DNA and cccDNA expression in WCM-260 cultures depended to some extent on the amount of virus in the inoculum. Thus, the viral DNA level progressively increased when the WHV content of the inoculum was raised to ∼107 VGE/ml (Fig. 2). WHV amounts greater than 107 VGE/ml usually did not further enhance the intensity of virus DNA signals (data not shown). It was also observed that exposure of WCM-260 cells to inocula with 107 VGE/ml or greater led with the highest frequency to infection accompanied by cccDNA (Fig. 2 and Table 1). The appearance of cccDNA sequences in a time-dependent and virus dose-related manner provided strong evidence that cccDNA had been synthesized in WCM-260 and specifically detected by the assay employed.

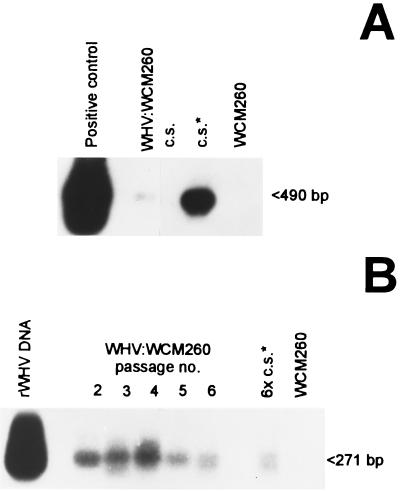

FIG. 2.

Effect of various amounts of WHV in inoculum on WHV DNA and cccDNA expression in in vitro-infected woodchuck hepatocytes. WCM-260 cells were exposed for 24 h to culture supernatant containing the indicated amounts of WHV obtained after a 72-h culture of splenocytes isolated from a chronic WHV carrier. After removal of inoculum, hepatocytes were cultured for an additional 3 days and harvested. DNA extracted from hepatocytes was digested with mung bean nuclease and assayed for WHV DNA and cccDNA by direct and nested PCR, respectively, and the amplified products were analyzed by Southern blot hybridization to an rWHV DNA probe. WHV DNA was included as a positive control, and mung bean nuclease-treated DNA from virus-naive WCM-260 hepatocytes and a mock sample extracted and treated in parallel with test samples were used as negative PCR controls. Positive samples showed nucleotide fragments of the expected sizes, as noted by arrowheads. Numbers under the upper panel represent 103 WHV genome copies (VGE) per μg of total DNA in infected hepatocytes, estimated by densitometric analysis of hybridization signals.

Other relevant experiments demonstrated that in vitro-infected WCM-260 hepatocytes can display WHV core and envelope antigens at levels detectable by specific antibody and flow cytometry and secrete WHV DNA-reactive particles infectious to both virus-naive WCM-260 cells and healthy woodchucks (details presented below). Therefore, it was established with full confidence that the hepatocytes were susceptible to WHV, supported productive replication of the virus, and released infectious virions. The propagation and survival rates of WHV-infected WCM-260 hepatocytes were identical to those of uninfected cells, suggesting that virus replicating in vitro is not cytopathic.

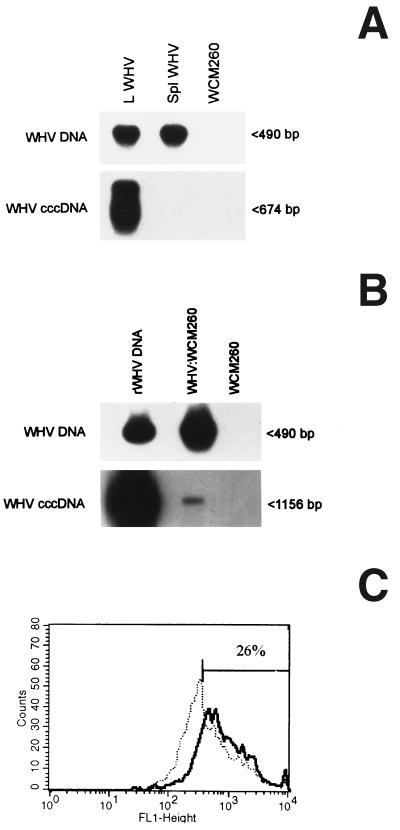

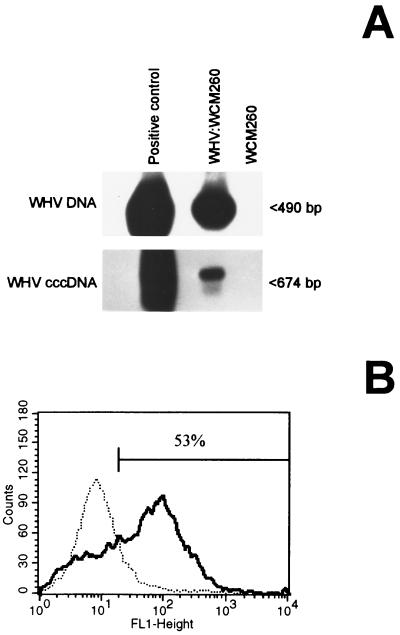

Susceptibility of woodchuck hepatocytes to serum- and lymphoid cell-derived WHV.

Assessment of WHV DNA in inocula prepared from either lymphoid cells or sera and subjected to extensive DNase digestion revealed that the vast majority (∼80%) of WHV DNA-reactive molecules resisted the enzyme treatment. This implied that they were encased within a protective envelope, as would occur in virions. In consequence, it was accepted that the estimated VGE levels reflected the virion contents with a high degree of accuracy. The same DNase treatment of plasmid-derived DNA completely eliminated WHV DNA reactivity, as determined by Southern blot hybridization of PCR products (data not shown). To ascertain the specificity of WHV cccDNA determination, DNA from infectious WHV that was secreted in culture by in vivo-infected splenocytes (experiment 14, Table 1) was digested with mung bean nuclease and then amplified. The nuclease-treated DNA cannot be detected with the nick-spanning primers but was readily identifiable by PCR with primers specific for the core gene, as illustrated in Fig. 4A. The equivalent amount of the nuclease-treated WHV DNA derived from the liver of a chronically infected animal showed evident signals for both cccDNA and the core gene. This demonstrated that cccDNA can be detected in the intracellular WHV genome material but not in the extracellular virions.

FIG. 4.

Analysis of WHV inoculum produced by naturally infected splenic lymphoid cells and susceptibility of woodchuck hepatocytes to this inoculum. (A) WHV at 2 × 107 VGE secreted during a 72-h culture of splenocytes isolated from a chronic WHV carrier (Spl WHV) and a comparable amount of WHV DNA from chronically infected liver (L WHV) were digested with mung bean nuclease and analyzed for WHV DNA and cccDNA by a differential PCR protocol. Mung bean nuclease-treated DNA from virus-naive WCM-260 cells (WCM260) was used as a negative PCR control. (B and C) WCM-260 hepatocytes were exposed to the same splenocyte-derived inoculum at 2 × 107 VGE/ml and analyzed as described in Materials and Methods. (B) Expression of WHV DNA and cccDNA. DNA was extracted from hepatocytes incubated with virus (WHV:WCM260) and from virus-naive hepatocytes cultured under the same conditions (WCM260). DNA was amplified and analyzed by Southern blot hybridization to detect WHV DNA and cccDNA. rWHV DNA was included as a positive control. (C) Flow cytometry histograms of WHcAg expression. Hepatocytes exposed to WHV inoculum (solid line) and virus-naive control cells (a negative control; dotted line) were stained with rabbit anti-WHc antibodies and secondary goat antibodies to rabbit IgG. Further details are provided in the legend to Fig. 3.

Table 1 summarizes the results on WHV DNA and cccDNA detection, as well as WHsAg and WHcAg identification in WCM-260 hepatocytes exposed to 14 different inocula containing various amounts of virus. In all experiments, both lymphoid cells that provided virus and hepatocytes collected at day 3 p.i. were enzymatically treated to ensure that only virus synthesized by lymphoid cells was used for hepatocyte inoculation and that only intracellular viral nucleic acid sequences were being examined in infected WCM-260 cells. The data from these 14 separate experiments revealed that WCM-260 hepatocytes became WHV infected (i.e., WHV DNA positive) in all the trials. In addition, virus cccDNA was identified in half (7 of 14) of the experiments, whereas virus antigens were found in 8 of the hepatocyte cultures. These findings provide evidence that the cultured woodchuck hepatocytes were susceptible to virus either produced by lymphoid cells or freely occurring in the circulation.

The results from representative experiments 2 and 14 (Table 1) are illustrated in Fig. 3 and 4, respectively. In experiment 2 (Fig. 3), WCM-260 cells were exposed to WHV from serum containing 1.2 × 109 VGE/ml. The hepatocytes became both WHV DNA and cccDNA reactive after a standard 3-day culture (Fig. 3A). The most conservative estimation indicated that at least 1 in 30 and 1 in 300 hepatocytes carried a copy of WHV DNA and cccDNA, respectively. In addition, 53% of the cells were found to be WHsAg positive by flow cytometry (Fig. 3B), while WHcAg was not detected.

FIG. 3.

Susceptibility of woodchuck hepatocytes to infection with serum WHV. WCM-260 cells were exposed to WHV at 1.2 × 109 VGE/ml derived from WHV-positive woodchuck serum as described under Materials and Methods. (A) Expression of WHV DNA and cccDNA. DNA was extracted at day 3 p.i. from hepatocytes inoculated with virus (WHV:WCM260) and from hepatocytes cultured in the absence of virus (a negative control; WCM260). DNA was digested with mung bean nuclease and analyzed for WHV DNA and cccDNA by direct and nested PCR, respectively, and then Southern blot hybridization. DNA from the liver of a chronic WHV carrier treated under exactly the same conditions was included as a positive control. (B) Fluorescence histograms of WHsAg expression. Hepatocytes exposed to WHV inoculum (solid line) and virus-naive cells (a negative control; dotted line) were probed with rabbit anti-WHs antibodies and secondary goat antibodies to rabbit IgG and then analyzed by flow cytometry. Cell numbers (counts) are plotted against the log of fluorescence intensity (FL1-Height). The percentage of hepatocytes reactive for WHsAg is indicated inside the panel.

In experiment 14 (Fig. 4), hepatocytes incubated with splenocyte culture supernatant containing 2 × 107 WHV VGE/ml demonstrated intracellular WHV DNA and WHV cccDNA at day 3 p.i. (Fig. 4B). Analysis showed that, similar to experiment 2, at least 1 in 30 cells carried a copy of the WHV genome, while 1 in 300 had a copy of WHV cccDNA. Approximately 25% of the hepatocytes displayed WHcAg (Fig. 4C), but WHsAg was not detected.

Infectivity of lymphoid cell- and serum-derived inocula with equal WHV content.

It was found that identical numbers of splenic lymphoid cells and PBMC isolated from the same chronic carriers released distinctively different quantities of WHV. Hence, while 72-h culture supernatant from 2 × 108/ml splenocytes normally contained more than 107 WHV VGE/ml, the same number of PBMC secreted no more than 3 × 104 VGE/ml. This finding was not entirely surprising considering the already mentioned fact that freshly isolated splenocytes expressed between 10- and 100-fold-greater amounts of WHV than PBMC. Nevertheless, it was of interest to assess whether WHV originating from splenic and peripheral lymphoid cells and from serum of the same host may vary in its potential to induce infection in hepatocytes. To test this, WCM-260 cells were exposed to identical VGE amounts of the virus secreted by splenocytes or PBMC or that present in serum of the same chronically infected woodchucks. In one of the trials, hepatocytes were exposed to WHV derived from splenocytes, PBMC, or serum at 104 VGE/ml. The results revealed that while WHV DNA was expressed in hepatocytes incubated with all three types of inocula, WHV cccDNA signal was detected only in the cells exposed to virus derived from splenocytes (data not shown). In another experiment, WCM-260 hepatocytes were incubated with inocula prepared from splenocytes or serum of the same chronic carrier containing 107 VGE/ml (Fig. 5). Analysis of DNA from day 3 p.i. hepatocyte cultures showed comparable levels of intracellular WHV DNA. However, cccDNA was detected only in the cells exposed to WHV produced by splenocytes (Fig. 5). Identical results were obtained when these inocula were tested on two different occasions. These observations raised the possibility that WHV inocula derived from splenocytes might somehow have a greater intrinsic ability to establish active replication in hepatocytes than that from serum or circulating lymphoid cells.

FIG. 5.

Comparison of in vitro infectivity of inocula with equal WHV content derived from serum and splenocytes of the same chronic WHV carrier. One-day WCM-260 hepatocyte cultures were exposed for 24 h to 107 DNase-protected WHV VGE/ml obtained from either serum (Ser WHV:WCM260) or splenocytes (Spl WHV:WCM260) of the same chronic WHV carrier and cultured under conditions described in Materials and Methods. DNA extracted from day 3 p.i. hepatocyte cultures was digested with mung bean nuclease and amplified with primers specific for WHV core gene by direct PCR or the virus nick region by nested PCR. As a positive control, mung bean nuclease-digested DNA from the liver of a chronic WHV carrier was used. DNA from virus-naive WCM-260 hepatocytes treated with mung bean nuclease and a mock sample treated exactly like the test samples were included as negative controls. Positive samples showed hybridization signals of the expected molecular sizes, as noted by arrowheads.

Serial passage of WHV from lymphoid cells in hepatocyte cultures.

WCM-260 hepatocytes exposed to 3 × 104 VGE/ml of WHV released during 72-h culture by naturally infected PBMC (experiment 9, Table 1) became virus DNA positive, and the pellet of their 3-day culture supernatant was reactive for viral DNA (Fig. 6A). Further, 19% of the hepatocytes were found to be reactive for WHcAg by flow cytometry, while WHsAg was not detected (Table 1). The culture medium harvested after the first passage in WCM-260 cells contained an estimated 1.3 × 104 WHV VGE/ml. It was determined that hepatocytes collected after each of the five consecutive passages (experiment 9A) expressed WHV at comparable levels of about 2 × 102 VGE/μg of cellular DNA (Fig. 6B). The culture medium after the final 6th virus passage in WCM-260 cells contained approximately 2.2 × 103 VGE, of which 1.3 × 103 VGE was injected into woodchuck WM.1. These results showed that WHV released by naturally infected peripheral lymphoid cells was infectious to homologous hepatocytes even after several passages and that the virus can be maintained in vitro by serial propagation.

FIG. 6.

Serial passage of WHV secreted by naturally infected lymphoid cells in woodchuck hepatocyte cultures. WCM-260 cells were exposed to supernatant containing 3 × 104 WHV VGE/ml from cultured PBMC isolated from a chronic WHV carrier (experiment 9, Table 1). The virus produced by hepatocytes after day 3 p.i. of culture was passaged five consecutive times in WCM-260 cell cultures as described under Materials and Methods. DNA was extracted (A) from hepatocytes after the first WHV passage (WHV:WCM260) and from 100 μl of the cell supernatant (c.s.) or the suspended pellet obtained after ultracentrifugation of the supernatant (c.s.∗) and (B) from hepatocytes after each of the five subsequent virus passages (passages 2 to 6) and 100 μl of the ultracentrifugation— concentrated culture supernatant collected after passage 6 (6 × c.s.∗). WHV DNA was assayed by direct PCR (A) or nested PCR (B) with WHV core gene-specific primers and detected by Southern blot hybridization to the rWHV DNA probe. Mung bean nuclease-digested DNA from a chronically infected liver or rWHV DNA was included as a positive control, and DNA from virus-naive WCM-260 hepatocytes was used as a negative control.

In a complementary experiment (experiment 14), WCM-260 cells were exposed to 2 × 107 VGE/ml of WHV produced by splenocytes from another chronic WHV carrier (Table 1). The resulting day 3 p.i. culture medium was used to transfer WHV to naive WCM-260 cells (experiment 14A). It was found that hepatocytes after each of the five consecutive virus passages contained WHV genomes at approximate levels of 103 VGE/μg of cellular DNA (data not shown). The medium collected after the final (sixth) virus passage contained in total 1.3 × 104 WHV VGE, of which 7.8 × 103 VGE was injected into woodchuck WM.2.

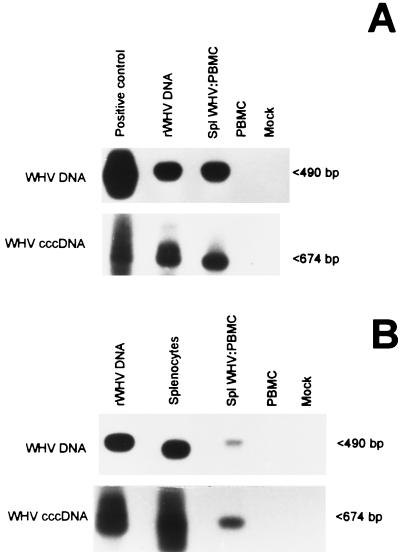

Transmissibility of WHV from lymphoid cells to virus-naive hepatocytes or lymphoid cells in cocultures.

To investigate whether WHV secreted by lymphoid cells can directly infect virus-naive hepatocytes or lymphoid cells, splenocytes isolated from a chronic WHV carrier were cocultured with WCM-260 cells or with freshly isolated PBMC obtained from healthy woodchucks. In splenocyte-hepatocyte cocultures, intracellular WHV DNA and cccDNA signals become readily detectable in WCM-260 cells after 4 days in culture. It was estimated that there were approximately 3 × 104 copies of WHV DNA and 5 × 103 copies of cccDNA per μg of total hepatocellular DNA. Assuming that at least one copy of WHV DNA or cccDNA existed in the infected cell, one in five hepatocytes contained a copy of virus DNA and 1 in 40 contained a copy of cccDNA. Therefore, hepatocytes infected in cocultures with splenocyte-derived virus had five- to sixfold-greater WHV levels than those exposed to culture supernatant obtained from the same splenocytes (data not shown).

WHV-naive lymphoid cells were susceptible to WHV infection either when exposed to supernatant from infected splenocytes or when cocultured with the spleen cells (Fig. 7). Figure 7A illustrates detection of WHV DNA and cccDNA in the initially virus-naive PBMC after incubation with culture supernatant obtained after standard 72-h culture of chronically infected splenocytes. The estimated WHV DNA and cccDNA copy numbers in these infected cells were 3.2 × 103 and 6.4 × 102 VGE/μg of total DNA, respectively. In lymphoid cell-lymphoid cell cocultures, the splenocyte-derived virus was also able to establish replication in naive lymphoid cells, as shown in Fig. 7B. The estimated copy numbers of WHV DNA and cccDNA in PBMC infected in this experiment were 7.2 × 102 and 1.4 × 102 VGE/μg of total DNA, respectively. The above depicted levels of WHV nucleic acids in de novo-infected lymphoid cells were closely comparable to those found in other experiments of the same type completed in this study. Overall, in contrast to hepatocytes, WHV levels in in vitro-infected lymphoid cells were not evidently affected by whether the virus originated from splenocyte culture supernatant or was directly transmitted from splenocytes in coculture. In addition, the level of cccDNA expression in the newly infected lymphoid cells appeared to be similar to those of the total WHV genome, suggesting that the rates of WHV replication could be different in hepatocytes and in lymphoid cells.

FIG. 7.

In vitro infection of woodchuck lymphoid cells with WHV from chronically infected splenocytes. (A) PBMC (107) isolated from a healthy woodchuck were incubated for 24 h with 108 VGE of WHV produced by splenocytes prepared from a chronic WHV carrier. After a 24-h icubation, the inoculum was removed, and cells were washed and cultured for an additional 72 h. DNA was extracted from surface DNase/trypsin/DNase-treated cells (SplWHV:PBMC), digested with mung bean nuclease, and assayed for WHV DNA and cccDNA by nested PCR and Southern blot hybridization as described under Materials and Methods. (B) Virus-naive PBMC (106) from a healthy woodchuck were cocultured for 4 days with 106 DNase/trypsin/DNase-treated splenocytes from the same chronic carrier as in panel A. DNA was extracted from both infected (SplWHV:PBMC) and lymphoid cells (splenocytes) that supplied the virus. DNA treated with mung bean nuclease was analyzed for WHV DNA and cccDNA expression as in panel A. DNA from the liver of a chronic WHV carrier treated under the same conditions as the test samples was used as a positive control, and similarly treated DNA from virus-naive PBMC and mock-infected samples were included as negative controls.

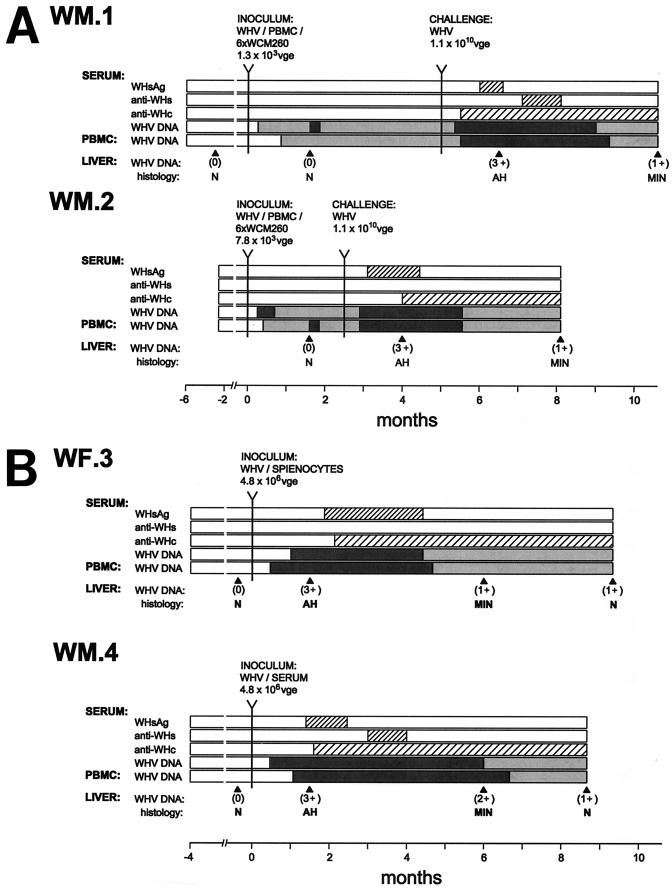

In vivo infectivity of lymphoid cell-derived WHV.

Analysis of serum samples from woodchucks WM.1 and WM.2, inoculated with low doses (∼103 VGE) of WHV produced by naturally infected PBMC or splenocytes and than serially passaged in WCM-260 hepatocyte cultures, showed the appearance of WHV DNA beginning at day 7 p.i. (Fig. 8A). The virus DNA persisted in serum at approximate levels of 102 VGE/ml until the animals were challenged with a massive WHV dose (1.1 × 1010 DNase-protected VGE) at 10 or 20 weeks after the initial inoculation. Prior to WHV challenge, small amounts of WHV DNA and, occasionally, WHV cccDNA were detectable in serial PBMC samples, but not in liver tissue collected at week 6 p.i. Interestingly, although WHV infection was evident at the molecular level, serum remained negative for WHsAg and anti-WHc antibodies. After challenge with a massive WHV dose, both animals developed a typical, histologically evident acute hepatitis accompanied by WHsAg and anti-WHc in serum (Fig. 8A). The disease was self-limiting and superseded by serological recovery, although WHV DNA persisted at the low levels in serum, PBMC, and liver until the end of the 5-month observation period.

FIG. 8.

Serological and molecular profiles of WHV infection in woodchucks inoculated with WHV that was secreted by naturally infected lymphoid cells and then serially passaged in WCM-260 hepatocytes or inoculated with equal doses of WHV obtained from splenocytes or serum of the same chronic WHV carrier. (A) WHV produced by PBMC or splenic lymphoid cells isolated from chronic WHV carriers were passaged six consecutive times in WCM-260 cells (WHV/PBMC/6×WCM260 and WHV/Spleen/6×WCM260), and the final culture supernatants containing the indicated amounts of WHV were intravenously injected into virus-naive woodchucks WM.1 and WM.2, respectively. (B) Equivalent amounts of DNase-protected WHV secreted by cultured splenocytes or obtained from serum of the chronic WHV carrier that provided the splenocytes were intravenously injected into virus-naive woodchucks WF.3 and WM.4, respectively. The graphs display the appearance and the span of duration of serum WHsAg, anti-WHs, and anti-WHc antibodies and expression of WHV DNA in serum, PBMC, and liver tissue samples. WHV DNA in serum and PBMC samples was detected by direct (dark grey bar) and nested (light grey bar) PCR followed by Southern blot analysis of the amplified sequences. The level of WHV genomes in liver tissue was assessed by direct PCR followed by Southern blot analysis of amplicons and is presented as values of 0, 1+, 2+, and 3+, corresponding to 0, 2 to 20, 2 × 103, and >2 × 106 WHV VGE per 104 cells, respectively, which were estimated as reported previously (22). Liver histology: N, normal; AH, acute hepatitis; MIN, minimal (residual) hepatitis.

WF.3 and WM.4 injected with 4.8 × 106 DNase-protected WHV VGE produced by splenocytes or derived from serum of the same chronic WHV carrier developed classical, serologically and histologically evident acute viral hepatitis (Fig. 8B). Liver inflammation was transient in both animals and followed by almost complete morphological recovery. WF.3, which was injected with WHV derived from splenocytes, remained serum WHsAg reactive for 10 weeks after the first antigen appearance and had slightly more severe lobular hepatitis than WM.4, inoculated with WHV from serum, which seroconverted to anti-WHs after a 5-week period of WHsAg positivity.

DISCUSSION

Lymphoid cells isolated from animals infected with WHV and depleted of surface-attached virus genomic material displayed virus DNA and the replicative precursor cccDNA and released viral particles infectious to cultured woodchuck hepatocytes and lymphoid cells and to susceptible animals. These naturally infected lymphoid cells, of either peripheral or splenic tissue origin, survived for up to 4 days under conditions designed for woodchuck hepatocyte culture without appreciable changes in their viability and intracellular WHV content. This transiently steady expression of WHV indicated that the cells support productive virus replication in vitro and can provide lymphotropic virus for in vivo and in vitro experimentation. It was also discovered that the efficiency of WHV replication in lymphoid cells maintained in hepatocyte culture conditions remained unchanged upon stimulation with mitogens, such as LPS and PHA. This finding was in contrast to the data reported previously showing that culture of lymphoid cells from WHsAg-positive chronic or occult WHV infection in the presence of bacterial LPS, PHA, or concanavalin A enhanced synthesis of viral transcripts and secretion of infectious virus (4, 11, 22). This discrepancy was most likely due to the presence of dexamethasone in the hepatocyte medium used for culture of lymphoid cells in the present study. This glucocorticoid has been shown to upregulate HBV DNA and protein expression in HBV-transfected and -infected hepatoblastoma cell lines (2, 33, 39). Therefore, it is likely that WHV replication in lymphoid cells in our study was unresponsive to mitogen stimulation because it was already upregulated by the glucocorticoid. This was supported by our other observations that WHV-infected PBMC cultured for 72 h in RPMI 1640 medium (4, 8) with 10 μM dexamethasone displayed WHV DNA signals at twofold-greater intensity than PBMC cultured without the hormone and that these signals were comparable in strength to those seen in equivalent numbers of cells cultured in RPMI 1640 medium containing LPS mitogen (data not shown).

A continuous WCM-260 hepatocyte line established from the liver of a healthy adult woodchuck was found to be susceptible to WHV infection and able to support a complete cycle of virus replication years after its founding. The active propagation of WHV in WCM-260 hepatocytes was evidenced by (i) appearance of virus DNA and cccDNA after exposure to different WHV inocula prepared from infected sera or lymphoid cells, (ii) synthesis and cell surface expression of WHV core and surface antigens, and (iii) secretion of viral particles infectious to cultured hepatocytes and to virus-naive animals. Analysis of WHV DNA and cccDNA expression within WCM-260 cells at different days p.i. showed that while virus DNA became identifiable at the end of a 24-h incubation with virus, cccDNA was first detected at day 1 or 2 p.i. This delayed appearance of cccDNA in WCM-260 hepatocytes is consistent with the previous observations on WHV and duck HBV virus (DHBV) replication in primary woodchuck or duck hepatocytes (1, 3, 31, 40, 41). It was postulated that this postponement in cccDNA formation could be a consequence of various intracellular processes, which may include inefficiencies in virus genome uncoating and/or nucleocapsid translocation to the nucleus, a requirement for accumulation of the virus products controlling cccDNA assembly, or be due to an intrinsic inefficiency of the cell cultures employed (1, 9, 31).

In our culture system, proliferating hepatocytes were exposed to WHV from lymphoid cells or sera and maintained for 3 days after inoculation, i.e., 4 days after addition of virus, to the moment when they become fully confluent. The kinetics of cccDNA expression appeared to follow the dynamics of WCM-260 cell proliferation, which achieved maximum at day 3 after seeding, as determined by a microculture tetrazolium assay (6, 25) (data not shown). This may suggest that WHV cccDNA formation could depend upon the pace of new cell formation. In this regard, it has been shown previously that the early phase of DHBV cccDNA amplification in in vitro-infected primary duck hepatocytes occurred only when cells underwent division (38). The suppression of hepatocyte division at the G1 phase inhibited the accumulation of DHBV cccDNA, whereas restoration of cell proliferation increased cccDNA expression in these cells. The dependence of hepadnaviral cccDNA formation on the cell cycle was thought to be due to the transport of viral nucleocapsids to the nucleus, which appears to be upregulated during the G1 phase (43). In our system, the delay in the appearance of cccDNA could be a consequence of rounds of virus replication in newly formed cells that led to progressive accumulation of cccDNA to the level that became detectable by the PCR and Southern blot hybridization assay.

The levels of WHV DNA and cccDNA expression in WCM-260 hepatocytes infected with WHV derived from lymphoid cells or sera were lower than those reported for primary woodchuck hepatocytes (1, 24). In our work, it was estimated that at least 1 in 30 and 1 in 300 WCM-260 hepatocytes carried a copy of the WHV genome and cccDNA, respectively. The levels of these nucleic acids were six- to sevenfold greater for WCM-260 hepatocytes cocultured with WHV-infected splenocytes. In comparison, for WHV-infected primary woodchuck hepatocytes, it has been reported that each cell presumably carried a copy of cccDNA (1, 24). However, there are important differences between our experimental system and that mentioned above, which need to be considered when comparisons are attempted. The unique features of our approach were (i) the use of a stable woodchuck hepatocyte line in the active phase of cell proliferation instead of primary hepatocytes seeded at confluence— this provided an unvarying supply of well-characterized, proliferating hepatocytes but potentially decreased susceptibility of the cells to WHV infection because of their long-term culture; (ii) an extensive enzymatic treatment of infected hepatocytes prior to DNA extraction that eliminated carryover of extracellular viral material but caused a partial loss (by approximately 20%) of the cells available for molecular analysis; and (iii) the inclusion of the mung bean nuclease digestion step that eliminated molecules with single-stranded DNA sequences and therefore strengthened specificity of cccDNA detection but lowered viral DNA due to additional manipulations. In consequence, evaluations of virus-specific DNA and cccDNA expression were done under very stringent experimental and assay conditions, and therefore the reported levels are the most conservative estimations.

The expression of WHsAg and WHcAg varied significantly in WCM-260 hepatocytes from different experiments and was not related to the estimated intracellular levels of virus genomes. Since there is no direct relationship between hepadnavirus DNA expression and the rate of its protein synthesis in infected hepatocytes, even in an in vivo situation, and because the levels of viral genomes were almost certainly underestimated in this study due to the stringency of the detection approach used, the above observation is not unexpected. On the other hand, a variance in the display of individual WHV antigens in infected WCM-260 could be a consequence of a number of virus- or cell-dependent factors, which remain largely unidentified for infections progressing either in vivo or in cell culture conditions. Since the inocula used in this study were derived from different chronic WHV carriers and sites, genotypic diversity of the infectious virus could have influenced viral replication efficiency and antigen synthesis in individual experiments. Other potential factors include variations in the rates of viral antigen secretion from infected cells, intrinsic characteristics of WCM-260 cells, and the relative insensitivity of the detection method used. This complex issue will require further investigation.

The establishment of the in vitro system in the present study permitting culture of hepatocytes and lymphoid cells under the same microenvironment provided a significant experimental advantage that enabled direct transfer of WHV synthesized by lymphoid cells to hepatocyte cultures and analysis of virus infectivity under uniform in vitro conditions. This also constituted a basis for the development of the lymphoid cell-hepatocyte and lymphoid cell-lymphoid cell cocultures for direct cell infection experiments. The results obtained provided definitive in vitro evidence that WHV synthesized by lymphoid cells is infectious to host hepatocytes and lymphoid cells. This fact was documented using either culture supernatants containing WHV secreted by naturally infected lymphoid cells or WHV directly permeating from the infected lymphoid cells to virus-naive cell targets in cocultures.

Although the WHV content was found to be an important determinant of the inoculum's ability to establish infection in WCM-260 hepatocytes, virus origin also appeared to have some influence on the efficiency of this process. It was noticed that when inocula with equal WHV content prepared from splenocytes, PBMC, or serum from the same chronic carriers were used to infect WCM-260 cells, virus derived from splenocytes had the highest potency to initiate replication, as evidenced by the appearance of cccDNA. This finding raised the possibility that WHV propagating within cells of lymphatic organs might somehow be more invasive toward host hepatocytes than that circulating freely or present within PBMC. At this stage, the basis of this phenomenon remains unexplained. It is conceivable that the presence in inoculum of virus genotypic and structural variants and/or replication-defective particles might modify the virus's final ability to recognize and invade permissive cells. It also is possible that the organ- or cell type-specific processes controlled, for example, by local or intracellular proteases may contribute to this process. In this regard, of note are our previous findings demonstrating that proteolytic cleavage of the WHV envelope is essential for presentation of the cell binding site recognizing woodchuck hepatocytes and lymphoid cells in a strictly host and cell type-specific manner (8). This site (designated WHV CBS1) has been identified in the N-terminal portion of the pre-S1 domain of the large WHV envelope protein and mapped to amino acids 10 to 13 of the domain. In addition, synthetic analogues of the site displayed considerably greater capacity for binding to woodchuck lymphoid cells than to hepatocytes. This ability was further augmented when lymphoid cells stimulated to cell division and blastoid formation by mitogens were used as targets (8). From these findings, we have postulated that dedifferentiated or immature lymphoid cells in the lymphatic organs, which embrace the most active lymphoid cell proliferation during adolescence, might be preferential targets and perhaps initial sites of WHV replication (8).

In an attempt to recognize whether the virus produced by lymphoid cells is as pathogenic as that existing freely in the circulation and to determine whether the observed increased potential to induce replication in cultured hepatocytes by splenocyte-derived virus has its equivalent in vivo, comparable amounts of WHV secreted by naturally infected splenic lymphoid cells or existing in serum of the same chronic WHV carrier were DNase treated and administered to virus-naive woodchucks. The results revealed that the virus originating from these two extrahepatic locations induced typical, self-limiting acute hepatitis with roughly similar profiles of WHV serological markers. This experiment revealed that virus produced by naturally infected organ lymphoid cells is infectious and pathogenic to at least the same degree as that occurring freely in the circulation. Accordingly, no persuasive evidence has been obtained so far that the splenocyte-derived virus might be better predisposed to induce more severe liver injury. In this regard, our previous study has shown that the same pool of WHV derived from peripheral lymphoid cells induced dramatically different patterns of viral hepatitis in individual animals, indicating that the host milieu may profoundly influence the infection outcome (22). This indicates that more extensive investigation in a series of WHV-naive woodchucks infected with various doses of the lymphoid cell-derived virus will be required to make conclusions with full confidence about the pathogenic vigor of hepadnavirus propagating in lymphatic organs.

WHV produced by infected circulating or splenic lymphoid cells remained infectious to virus-naive animals after several passages in hepatocyte cultures. This result demonstrates that the virus continued to be biologically competent in spite of the multistep transfer in permissive cells and that our hepatocyte culture system did not alter the virus's infectious capabilities. The virus recovered following passage in WCM-260 hepatocytes was injected at amounts not exceeding 104 VGE and caused infection characterized by the presence of WHV genomes in serum and circulating lymphoid cells, but not in the liver. Moreover, this infection advanced in the absence of WHV serological markers, i.e., WHsAg, anti-WHs, and anti-WHc, and did not provide protection against challenge with a massive WHV dose (1.1 × 1010 VGE). In this context, it is important to indicate that we have previously observed exactly the same pattern of WHV infection when investigating offspring born to mothers recovered from WHV hepatitis (4), woodchucks inoculated with WHV derived from serum or lymphoid cells of these offspring (18; Coffin et al., unpublished), and a woodchuck experimentally inoculated with viable PBMC collected years after resolution of acute WHV hepatitis (22). A comparative analysis of the data from these studies and from the current work points to a common factor predisposing to the development of this occult, nonprotective, lymphatic system-restricted infection. The uniform prerequisite appears to be a small amount of the invading virus (reviewed in reference 18). At this stage, other viral factors, including virus variants with tropism for lymphoid cells and not yet recognized elements of the host milieu, need to be considered, although their contributions seems to be less decisive. Further studies, currently in progress in our laboratory, should clarify this important issue.

The results of this study provide straightforward evidence that lymphoid cells are the sites of active replication of hepadnavirus infectious to homologous hepatocytes and lymphoid cells. They substantiate a motion based on fragmented clinical and experimental observations postulating that circulating lymphoid cells can be hepadnavirus chaperons from which virus may strike the liver. The data also reinforce the concept that invasion of the lymphatic system is an unavoidable consequence of hepadnavirus infection, even when the liver remains unaffected (reviewed in reference 18). As in other viral infections that involve the lymphatic system, the presence of replicating virus in lymphoid cells may have multiple detrimental effects on the host regulatory and protective immune responses.

Among others, as we have recently shown for chronic WHV infection (20), hepadnavirus severely reduces the display of class I MHC molecules on lymphoid cells and, in consequence, may potentially alter cell-to-cell communication and deregulate immune cell functions. These virus-induced effects, although not always directly apparent, may have generalized dissenting effect on the immune system and contribute to long-term virus persistence in the lymphatic system.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Norma D. Churchill and Colleen L. Trelegan for expert assistance.

This work was supported by operating grants MT-14818 and RO-15174 to T.I.M. from the Medical Research Council of Canada.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aldrich C E, Coates L, Wu T-T, Newbold J, Tennant B C, Summers J, Seeger C, Mason W S. In vitro infection of woodchuck hepatocytes with woodchuck hepatitis virus and ground squirrel hepatitis virus. Virology. 1989;172:247–252. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(89)90126-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chou C-K, Wang L-H, Lin H-M, Chi C W. Glucocorticoid stimulates hepatitis B viral gene expression in cultured human hepatoma cells. Hepatology. 1992;16:13–18. doi: 10.1002/hep.1840160104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Civitico G M, Locarnini S A. The half-life of duck hepatitis B virus supercoiled DNA in congenitally infected primary hepatocyte cultures. Virology. 1994;203:81–89. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coffin C S, Michalak T I. Persistence of infectious virus in the offspring of woodchuck mothers recovered from viral hepatitis. J Clin Investig. 1999;104:203–212. doi: 10.1172/JCI5048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Colantoni A, Hassanein T, Idilman R, Van Thiel D H. Liver transplantation for chronic viral liver disease. Hepatogastroenterology. 1998;45:1357–1363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Diao J, Churchill N D, Michalak T I. Complement-mediated cytotoxicity and inhibition of ligand binding to hepatocytes by woodchuck hepatitis virus-induced autoantibodies to asialoglycoprotein receptor. Hepatology. 1998;27:1623–1631. doi: 10.1002/hep.510270623. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Féray C, Zignego A L, Samuel D, Bismuth A, Reynes M, Tiollais P, Bismuth H, Brechot C. Persistent hepatitis B virus infection of mononuclear cells without concomitant liver infection: the liver transplantation model. Transplantation. 1990;49:1155–1158. doi: 10.1097/00007890-199006000-00025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jin Y-M, Churchill N D, Michalak T I. Protease-activated lymphoid cell and hepatocyte recognition site in the preS1 domain of the large woodchuck hepatitis virus envelope protein. J Gen Virol. 1996;77:1837–1846. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-77-8-1837. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kann M, Bischof A, Gerlich W H. In vitro model for nuclear transport of the hepadnavirus genome. J Virol. 1997;71:1310–1316. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1310-1316.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kodama K, Ogasawara N, Yoshikawa H, Murakami S. Nucleotide sequence of a cloned woodchuck hepatitis virus genome: evolutional relationship between hepadnaviruses. J Virol. 1985;56:978–986. doi: 10.1128/jvi.56.3.978-986.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Korba B E, Wells F, Tennant B C, Cote P J, Gerin J L. Lymphoid cells in the spleens of woodchuck hepatitis virus-infected woodchucks are a site of active viral replication. J Virol. 1987;61:1318–1324. doi: 10.1128/jvi.61.5.1318-1324.1987. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lavine J E, Lake J R, Ascher N L, Ferrell L D, Ganem D, Wright T L. Persistent hepatitis B virus following interferon alfa therapy and liver transplantation. Gastroenterology. 1991;100:263–267. doi: 10.1016/0016-5085(91)90611-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Luskus T, Radkowski M, Wang L-F, Nowicki M, Rakela J. Detection and sequence analysis of hepatitis B virus integration in peripheral blood mononuclear cells. J Virol. 1999;73:1235–1238. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1235-1238.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marcellin P, Samuel D, Areias J, Loriot M-A, Arulnaden J-L, Gigou M, David M-F, Bismuth A, Reynes M, Brechot C, Benhamou J-P, Bismuth H. Pretransplantation interferon treatment and recurrence of hepatitis B virus infection after liver transplantation for hepatitis B-related end-stage liver disease. Hepatology. 1994;19:6–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Margolis H S, Alter M J, Hadler S C. Hepatitis B: evolving epidemiology and implications for control. Semin Liver Dis. 1991;11:84–92. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1040427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marinos G, Rossol S, Carucci P, Wong P Y, Donaldson P, Hussain M J, Vergani D, Portmann B C, Williams R, Naumov N V. Immunopathogenesis of hepatitis B virus recurrence after liver transplantation. Transplantation. 2000;69:559–568. doi: 10.1097/00007890-200002270-00017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Michalak T I. The woodchuck animal model of hepatitis B. Viral Hepatitis Rev. 1998;4:139–165. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Michalak T I. Occult persistence and lymphotropism of hepadnaviral infection: insights from the woodchuck viral hepatitis model. Immunol Rev. 2000;174:98–111. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0528.2002.017406.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Michalak T I, Churchill N D, Codner D, Drover S, Marshall W H. Identification of woodchuck class I MHC antigens using monoclonal antibodies. Tissue Antigens. 1995;45:333–342. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0039.1995.tb02463.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Michalak T I, Hodgson P D, Churchill N D. Posttranscriptional inhibition of class I major histocompatibility complex presentation on hepatocytes and lymphoid cells in chronic woodchuck hepatitis virus infection. J Virol. 2000;74:4483–4494. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.10.4483-4494.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Michalak T I, Lin B. Molecular species of hepadnavirus core and envelope polypeptides in hepatocyte plasma membrane of woodchucks with acute and chronic viral hepatitis. Hepatology. 1994;20:275–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Michalak T I, Pardoe I U, Coffin C S, Churchill N D, Freake D S, Smith P, Trelegan C L. Occult life-long persistence of infectious hepadnavirus and residual liver inflammation in woodchucks convalescent from acute viral hepatitis. Hepatology. 1999;29:928–938. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Michalak T I, Pasquinelli C, Guilhot S, Chisari F V. Hepatitis B virus persistence after recovery from acute viral hepatitis. J Clin Investig. 1994;93:230–239. doi: 10.1172/JCI116950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Moraleda G, Saputelli J, Aldrich C E, Averett D, Condreay L, Mason W S. Lack of effect of antiviral therapy in nondividing hepatocyte cultures on the closed circular DNA of woodchuck hepatitis virus. J Virol. 1997;71:9392–9399. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9392-9399.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mosmann T. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65:55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Moyer L A, Mast E E. Hepatitis B: virology, epidemiology, disease and prevention, and an overview of viral hepatitis. Am J Prevent Med. 1994;10:45–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nassal M, Schaller H. Hepatitis B virus replication. Trends Microbiol. 1993;6:221–228. doi: 10.1016/0966-842x(93)90136-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]