Climate change poses a major challenge for healthcare and the surgical community bears a disproportionate burden. Estimates indicate that operating theatres in Canada, the USA and the UK collectively generate 9.7 million tons of CO2 per year1. As surgeons, we have a shared responsibility to promote sustainable surgical care to align with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals to be CO2-neutral by 2050. Despite a recent survey among surgeons from 55 countries showing desire for sustainable practices, up to half of surgeons refrain from measures to reduce disposables2. This reluctance is partly due to uncertainty and a lack of knowledge about the actual contribution of surgery to CO2 emissions. Therefore, we aimed to determine the carbon footprint in kg CO2-equivalent (CO2-eq) of laparoscopic cholecystectomy (LC) and identify the main contributing factors through a process-based life-cycle assessment (LCA).

A multicentre observational study was conducted involving 15 elective LCs performed across two local teaching hospitals and one academic hospital in the Netherlands. In this study we analysed the entire life cycle of processes and materials involved in LC, from the extraction of raw materials to waste processes, known as ‘cradle to grave’. Inventory data were obtained by observation of material used during LC, waste audits, patient files and using a public database, considering all surgical instruments (that is reusables and disposables) utilized, medication provided during intraoperative phase, production and waste of used equipment, sterilisation process of reusable equipment, energy consumption, operating room (OR) scrubs and linen, and travel movements of OR personnel and patients. For the performed LCA the ISO14040 and ReCiPe2016 methodologies were applied, and processes were modelled in SimaPro 9 LCA-software using the Ecoinvent 3.9 database and the STREAM database3.

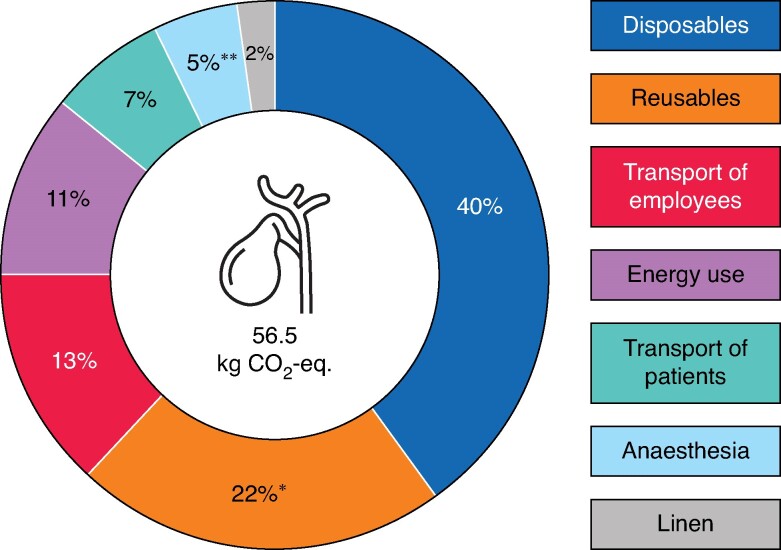

The median carbon footprint of a single LC was 56.5 kg CO2-eq. (i.q.r. 48.1–69.3). Disposable products were the largest contributors, accounting for 40% of the total footprint (22.7 kg CO2-eq.; i.q.r. 21.5–24.6). Energy consumption contributed 11% (6.1 kg CO2-eq.; i.q.r. 5.4–7.9) and reusable products constituted 22% (12.5 kg CO2-eq.; i.q.r. 12.5–12.5), with a substantial 81% of this portion attributable to the sterilization process (Fig. 1). Focusing on utilized products, each procedure used 133 individual products, with 86% being disposable. The hotspots for disposables were trocars, the clip applier, surgical gowns and surgical drapes. Disposable trocars and the clip applier accounted for 4.0 kg CO2-eq. (18% of disposables). Surgical gowns, worn by a median of three persons, contributed 19% (4.3 kg CO2-eq.), whereas drapes contributed 28% (6.2 kg CO2-eq.). Within the anaesthesia category, all medications produced 3.0 kg CO2-eq (i.q.r. 0.08–5.9, 5%). Sevoflurane, a volatile anaesthesia gas, accounted for 96% of the footprint within this category.

Fig. 1.

The carbon footprint of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy

Circle diagram of the carbon footprint of a laparoscopic cholecystectomy. A visualization representing relative contribution to the carbon footprint of one procedure, ordered in a hierarchy. *Sterilization made up 81% of reusable materials. **Volatile anaesthesia gas made up 96% of the total carbon footprint of all administered anaesthesia. Image of the gallbladder was developed by Freepik.

Extrapolated to the 61 000 LCs performed annually in the UK, this totals over 3.5 million kg CO2-eq, comparable to driving 22 million kilometres in an average petrol-fuelled car (560 times around the world), or the CO2 emission of 20 fully booked flights (290 passengers) from London to New York.

Quantification of CO2 emissions is crucial for assessing the impact of Refuse, Reduce, and Reuse measures in the circularity of surgery. For example, substituting disposables with reusable alternatives can reduce the carbon footprint by up to 70% for trocars and 83% for clip appliers4. With 280 000 trocars used annually in the UK for this procedure alone, this change can offer substantial environmental benefits. Regarding anaesthesia, total intravenous anaesthesia (TIVA) is a safe alternative to volatile gases, supported by existing guidelines.

To reduce the use of disposables, evaluating international practice variation and modelling sustainable alternatives can guide surgical equipment choices. However, refusing ineffective and unnecessary surgical procedures is the most effective method to decrease the carbon footprint. This is especially true for patients with uncomplicated gallstone disease, as 20–40% report persistent pain post-cholecystectomy5. Recent studies have demonstrated the safety and viability of conservative treatment for this condition, and improved patient selection and tailored care can potentially reduce the number of LCs5. The carbon footprint varies with the surgical approach, with robot-assisted surgeries generally having a higher environmental impact due to increased material use compared to open and laparoscopic procedures6,7. Although these advanced methods may offer some technical benefits, considering their application should factor in environmental impact and clinical benefits particularly for procedures like LC.

Advancing sustainability in surgery requires decarbonization policies and standardized reporting structures to track performance and develop best practices8. In conclusion, LC generates a substantial carbon footprint, with disposables as the major contributor.

Contributor Information

Daan J Comes, Department of Surgery, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Stijn Bluiminck, Department of Surgery, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Emma J Kooistra, Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Lindsey de Nes, Department of Surgery, Maasziekenhuis Pantein, Boxmeer, The Netherlands.

Frans T W E van Workum, Department of Surgery, Canisius-Wilhelmina Ziekenhuis (CWZ), Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Hugo Touw, Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Myrthe M M Eussen, Department of Surgery, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands; NUTRIM School of Nutrition and Translational Research in Metabolism, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Nicole D Bouvy, Department of Surgery, Maastricht University Medical Centre, Maastricht, The Netherlands; NUTRIM School of Nutrition and Translational Research in Metabolism, Maastricht University, Maastricht, The Netherlands.

Tim Stobernack, Department of Intensive Care Medicine, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Philip R de Reuver, Department of Surgery, Radboud Institute for Health Sciences, Radboud University Medical Centre, Nijmegen, The Netherlands.

Author contribution

Daan Comes (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Stijn Bluiminck (Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Emma Kooistra (Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), Lindsey De Nes (Project administration, Resources, Writing—review & editing), Frans Workum (Project administration, Resources, Writing—review & editing), Hugo Touw (Project administration, Resources, Writing—review & editing), Myrthe Eussen (Project administration, Resources, Writing—review & editing), Nicole Bouvy (Project administration, Resources, Writing—review & editing), Tim Stobernack (Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing), and Philip de Reuver (Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Supervision, Validation, Visualization, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing)

Disclosures

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Funding

In this work, Kooistra and Stobernack were supported by ZonMw (grant number 80-86800-98-112).

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (P.R.). The data are not publicly available due to ongoing research and are subject to further analysis.

References

- 1. MacNeill AJ, Lillywhite R, Brown CJ. The impact of surgery on global climate: a carbon footprinting study of operating theatres in three health systems. Lancet Planet Health 2017;1:e381–e388 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dal Mas F, Cobianchi L, Piccolo D, Balch J, Biancuzzi H, Biffl WL et al. Are we ready for “green surgery” to promote environmental sustainability in the operating room? Results from the WSES STAR investigation. World J Emerg Surg 2024;19:5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Huijbregts MAJ, Steinmann ZJN, Elshout PMF, Stam G, Verones F, Vieira M et al. Recipe2016: a harmonised life cycle impact assessment method at midpoint and endpoint level. Int J Life Cycle Assess 2017;22:138–147 [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rizan C, Bhutta MF. Environmental impact and life cycle financial cost of hybrid (reusable/single-use) instruments versus single-use equivalents in laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Surg Endosc 2022;36:4067–4078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Latenstein CSS, de Reuver PR. Tailoring diagnosis and treatment in symptomatic gallstone disease. Br J Surg 2022;109:832–838 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chan KS, Lo HY, Shelat VG. Carbon footprints in minimally invasive surgery: good patient outcomes, but costly for the environment. World J Gastrointest Surg 2023;15:1277–1285 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rizan C, Steinbach I, Nicholson R, Lillywhite R, Reed M, Bhutta MF. The carbon footprint of surgical operations: a systematic review. Ann Surg 2020;272:986–995 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Singh H, Eckelman M, Berwick DM, Sherman JD. Mandatory reporting of emissions to achieve net-zero health care. N Engl J Med 2022;387:2469–2476 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author (P.R.). The data are not publicly available due to ongoing research and are subject to further analysis.