Abstract

Abstract

Objectives

This study addressed two research questions: What factors do doctors in training describe as influencing their choices to apply (or not apply) for specialty training during their Foundation Year 2? Which of these factors are specific to the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the unique experiences of the cohort of doctors who qualified early during the pandemic?

Design

Sequential explanatory mixed methods study: Quantitative survey. Qualitative semistructured interviews. Quantitative data were analysed with logistic regression. Qualitative data were analysed using reflexive thematic analysis.

Setting

UK-wide.

Participants

Junior doctors who graduated medical school in 2020. Survey: 320 participants (22% of those contacted). 68% (n=219) were female, 60% (n=192) under 25 and 35% (n=112) 25–30. 72% (n=230) were white, 18% (n=58) Asian and 3% (n=10) black. Interviews: 20 participants, 10 had applied for specialty training, 10 had not.

Results

A minority of respondents had applied for specialty training to start in 2022 (114, 36%). While burnout varied, with 15% indicating high burnout, this was not associated with the decision to apply. This decision was predicted by having taken time off due to work-related stress. Those who had not taken time off were 2.4 times more likely to have applied for specialty training (OR=2.43, 95% CI 1.20 to 5.34). Interviews found reasons for not applying included wanting to ‘step off the treadmill’ of training; perceptions of training pathways as inflexible, impacting well-being; and disillusionment with the community and vocation of healthcare, based, in part, on their experiences working through COVID-19.

Conclusions

Participants infrequently cited factors specific to the pandemic had impacted their decision-making but spoke more broadly about challenges associated with increasing pressure on the health service and an eroded sense of vocation and community.

Keywords: health policy, medical education & training, health workforce

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

Focuses on an important area of concern for workforce planning—the attrition of junior doctors from specialty training programmes at point of entry.

Sequential explanatory mixed methods is a strength of this study as the results of the wider survey were used to shape the interview schedules, allowing focus on the most pertinent areas.

Qualitative analysis was informed by the quantitative data and the involvement of researchers from a range of backgrounds has added depth to the qualitative results.

Limitations include over-representation of female and white students in the initial survey.

Introduction

New clinicians starting work during the COVID-19 pandemic were among those most significantly affected by the challenges of treating a novel infectious disease and the consequent demands on healthcare. Many doctors starting work during the pandemic began as interim Foundation Year One doctors (FiY1), novel transitional roles introduced to support the existing medical workforce in the ‘first wave’ of the pandemic. These roles enhanced preparedness for starting the Foundation Programme but did increase early exposure to acutely unwell and dying patients, impacting well-being.1 2 In the UK, the post-pandemic period has been marked by acute workforce problems and unrest among doctors-in-training. Workforce issues were apparent before the pandemic3 4 but are now routinely recognised as a crisis.5 6

While medical school places are readily filled, there are growing concerns about the number of doctors not entering specialty training.7 Recruitment concerns are particularly prominent in general practice, emergency medicine and psychiatry,8,11 although there are staff shortages even within specialties whose training programmes are oversubscribed.12 The majority of medical trainees are now choosing not to enter specialty training directly after their 2-year Foundation training but rather take a year (or more) out of postgraduate training: the ‘F3’ year.13 The term ‘F3’ was initially informal, but the terminology has become widespread, with clinical and teaching posts advertised as ‘F3’ or ‘F4’. While these trends predate COVID-19, the strain of working through the pandemic and subsequent workforce crisis may have shaped doctors’ choices about their progression to specialty training or their future in the profession. Internationally, some works14,17 have addressed the perceptions of medical students on the impact of COVID-19 on their career destinations, but this population is some way from translating that preference into choice, and other experiences will intervene as the pandemic period recedes. There is evidence that increased work intensity during COVID-19 led to decreased job satisfaction among doctors,18 and that decreased satisfaction is associated with burnout.19 Studying and working during the pandemic increased both medical students’ and doctors’ rates of experiencing burnout, which may have an impact on their decision to either enter specialty training or take a break from postgraduate medical training.20 21

Given the additional pressures on the cohort of doctors who graduated into the COVID-19 pandemic and the concerns regarding the sustainability of the medical workforce in the face of reduced appetite for immediate entry to higher training from the Foundation Programme, understanding trainees’ decisions in a time of crisis may help identify risks in other times and other contexts. This work aims to gain a better understanding of the factors influencing the early career decision-making of junior doctors in the UK who had worked through the COVID-19 pandemic: specifically, the decision to either apply to enter specialty training or to take a break from postgraduate training.

The current study

This study considers the experiences of doctors in the UK who were at the point of choosing whether to apply for specialty training in 2021. Our research questions reflect an interest in the longer term effects of graduating at the height of a pandemic, and a more general understanding of how early experience informs not just preferences, but critical career decisions.

Research questions

What factors do doctors in training describe as influencing their choices to apply (or not apply) for specialty training during their Foundation Year 2?

Which of these factors are specific to the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the unique experiences of the cohort of doctors who qualified early during the pandemic?

Methods

Research approach

This was a sequential explanatory mixed methods study.22 A cross-sectional questionnaire set out to identify the choices, and reasons for those choices, of a wide sample of doctors. The results from this survey identified areas of focus and were followed by interviews with a purposive sample of respondents to examine in more detail how their experience had shaped their decisions.

Ethical considerations

Participation was voluntary. The online survey contained a statement that anonymised data may be used in publications, with completion indicating consent. For interviews, participants were sent an information sheet and consent form before the interview, and this was reviewed when confirming consent verbally at the start of each interview. All data were stored on password-protected Newcastle University servers.

Given the subject matter, participation had the potential to trigger recall of potentially distressing experiences, either related to patient care or participants’ own uncertainty about their career paths. Well-being resources were signposted in the interview and on the questionnaire, and interviewers were sensitive to any distress, meaning interviews may be paused or terminated, and participants signposted to appropriate support.

Context

The UK medical training system consists of undergraduate studies lasting 4–6 years, which can be entered either at undergraduate level or as a postgraduate option. Newly qualified doctors enter the Foundation Programme in August. This 2-year paid training role comprises six 4-month rotations in hospital and community medicine.23 After completion of this training, doctors can enter a specialty training programme in a hospital-based specialty or in general practice, at the end of which they can become a hospital-based consultant or general practitioner in primary care. The application process for specialty training is national and closes in December of each year, meaning that at the point of application, Foundation Programme trainees have had just over a year of postgraduate medical training. Specialty training programmes in the UK range from 3 to 8 years in duration. There are 65 General Medical Council (GMC) approved specialty training programmes, some of which are ‘run through’ and some of which are separated into core and higher training, with trainees reapplying for further training at the end of their core training of 2–4 years.24

Selection processes for the Foundation Programme are currently undergoing reform, but at the time of this study, entry to the Foundation Programme was based on a system of rankings—taking into account academic performance at medical school and results from a situational judgement examination. Final year medical students could preference a location (large geographical areas known as ‘deaneries’) and specific clinical rotations within these locations; however, these posts were allocated based on national rankings.

Participants

Participants were doctors in Foundation Programme Year 2 (F2) in 2021–2022, who had started work as F1 doctors in August 2020. They had therefore worked through the second substantial wave of COVID-19 in the UK (November 2020–February 2021). Many had also started work earlier, as interim Foundation Year 1 doctors (FiY1), but this was not a criterion for participation.

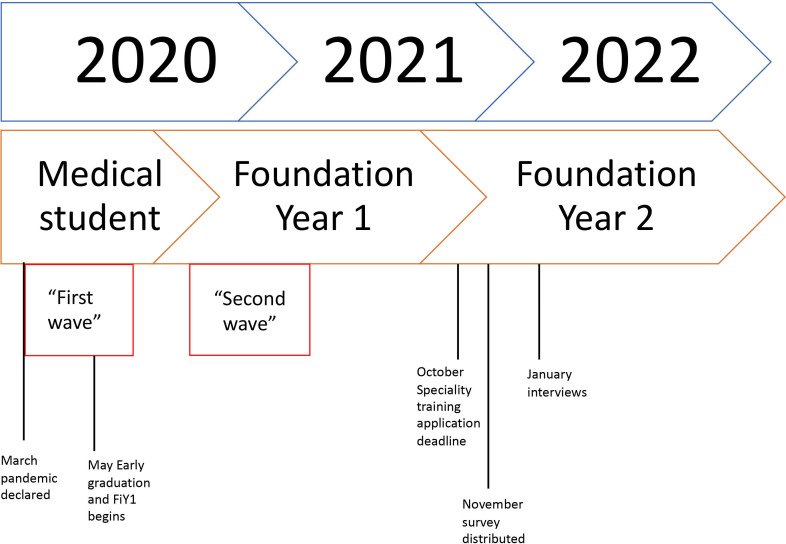

The survey was distributed in December 2021, the day after applications for specialty training had closed, to have authentic reflection of the actual decisions made. Figure 1 illustrates when data collection occurred in relation to participants’ qualification and the first waves of the pandemic (high infection, hospitalisation and mortality) in the UK.

Figure 1. Timeline to specialty choice for doctors starting work in 2020.

Recruitment

Participants were initially recruited to a study undertaken in 2020,1 25 in which they consented to be contacted about follow-up research. A total of 1427 participants (around 21% of their Foundation Programme cohort) had not opted out of contact and were emailed a link to the questionnaire (full questionnaire available in online supplemental material). This also allowed them to indicate willingness to take part in a research interview. Purposive sampling of questionnaire respondents was used to identify a sample for interview.

Questionnaire content

Survey questions were developed through discussion among the research team and piloted with three trainees who had been involved in the earlier study. To keep the questionnaire brief, demographic data (age group, gender, ethnic group) were populated from data provided in 2020, linked through a pseudonymising identifier associated with the survey, also preventing multiple participation. The online survey asked whether they had applied for specialty training or not, and their plans if not. It also included questions about their clinical work since 2020, burnout (the work burnout subscale of the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory26), whether they had taken time off due to work-related stress and whether the stress of clinical work had been higher, lower or as they had expected. Minor revisions to clarity of wording were made following feedback. The questionnaire is included in online supplemental material 1.

Interviews

About 217 respondents indicated willingness to be interviewed. A sample of 20, half who had applied for specialty training and half who had not, was purposively selected to provide representation across genders, ethnic groups, whether they had worked as an FiY1, and their response to the work burnout scale. A reserve sample of 20, matched on these criteria where possible, was also selected and invited if the initial sample declined or did not respond to an email invitation to arrange an online interview.

An interview guide was informed by the results of the survey covering questions about participants’ work since 2020, their well-being and their career plans, including general questions about their views of medicine. The interview schedule is included in online supplemental material 2.

Semistructured interviews were carried out online via Zoom or Teams in January–February 2022 by BB, GV, AG and YF.

Quantitative analysis

Quantitative analysis was undertaken in R V.4.3.2. χ2 tests were carried out to consider associations between categorical variables, while logistic regression was carried out to identify predictors of the decision to apply for training.27 A model with initial predictors burnout, having taken time off due to stress, whether stress was as expected, gender and ethnicity as predictors were considered; only predictors that significantly improved model fit (as indicated by the Akaike information criterion reported by the drop1 function in R) were retained in a final model.

Qualitative analysis

Qualitative analysis was conducted by AHB, BB and OB. The interviews were transcribed verbatim. Analysis was undertaken with a reflexive thematic analysis approach.28 Codes and themes were developed inductively from the data but refined following reflection and discussion informed by the researchers’ expertise. Interview transcripts were read and re-read by AHB, OB and BB to familiarise the researchers with the data. Initial thoughts were noted, and potential codes and areas of interest discussed at length. The results from the quantitative work were also discussed throughout the analytical process, and the findings from the quantitative analysis shaped the choice of focus on burnout and well-being. A set of potential codes were presented to the entire research group for discussion and where relevant codes were combined and condensed. Transcripts were coded and quotes extracted to stay close to the data. With reference to our initial research questions, themes were constructed and refined through discussion between the three researchers conducting the analysis and the wider research group. Themes were further iterated through the write-up process.

Patient and public involvement

Patients and the public were not involved in the conception, design or analysis of this research.

Reflexivity statement

The research team involved in data collection, analysis and writing came from a range of backgrounds, who brought different perspectives to shaping the project and interpreting the data. GV and CP had worked clinically during 2020–2021. GV is a consultant and GMC recognised trainer, who also leads the Specialised (previously Academic) Foundation Programme in the region. AHB entered the Foundation Programme in 2021, and her final year of medical school had been disrupted by the pandemic. During analysis, she was herself in the process of making key career decisions regarding her post-Foundation career trajectory, which has helped shape her interpretation of the data. GV and BB had led the initial project looking at the experience of those entering practice. YF is a mixed methods methodologist who was an F2 but decided to leave clinical practice. MB is an educational researcher who has previously researched new doctors’ transition to practice pre-pandemic. The mixture of personal and professional experience with the topic added to the richness of the qualitative analysis.

Results

Questionnaire

Respondents

About 320 participants (22% of those contacted) responded to the questionnaire between December 2021 and February 2022. Then, 68% (n=219) were female, 60% (n=192) under 25 and 35% (n=112) 25–30. Further, 72% (n=230) were white, 18% (n=58) Asian and 3% (n=10) black. These figures over-represent female and white students compared with the UK medical student population (where percentages are 55% and 59%, respectively29). About 165 respondents (52% of sample) had worked in a critical care unit or respiratory support unit since April 2020 (ie, during the pandemic).

Decision to apply

A minority of respondents had applied for specialty training to start in 2022 (114, 36%). These respondents had applied for a range of specialties—the most preferred being GP (n=36) and internal medicine training (n=34). For those who had not applied for specialty training, an additional question asked them to outline their further plans. Table 1 shows the frequency of responses for alternative plans to specialty training.

Table 1. Frequency of responses of those who had not applied for specialty training.

| Responses (n)* | |

| I intend to apply in 2022 to begin specialty training in 2023. | 95 |

| I intend to begin specialty training some time after 2023. | 68 |

| I do not have plans to apply for specialty training, but will continue to work clinically. | 30 |

| I do not intend to continue working clinically. | 5 |

| I haven’t yet decided what my plans are. | 31 |

Participants could select more than one option.

About 154 respondents (48% of the whole sample) indicated that their decision had been influenced by their experience of work during the pandemic. This was more true of those who had not applied for specialty training—56% vs 34% of those who had applied. However, more of those who had applied replied ‘Don’t know’ (47% vs 39%).

Burnout

The majority of respondents indicated low (124, 39%) or moderate (148, 46%) burnout on the Copenhagen Burnout Inventory work burnout scale. About 48 respondents (15%) indicated experiencing high burnout. This varied with gender, with women being more likely to have moderate (52% vs 33% of men) or high burnout (16% vs 12% of men, χ2=15.431, p=0.0004).

About 50 trainees (16%) had taken time off due to stress. There was an association between stress and having taken time off (χ2=12.899, p=0.002), with 32% (n=14) of those with high risk of burnout having taken time off, and just 9% (n=11) of those with low burnout. 52% (n=165) reported stress was higher than they had expected, 4% (n=13) that it was less than they had expected and 44% (n=142) as they had expected.

Binomial logistic regression found that the decision to apply for specialty training was predicted only by a participant having taken time off, and not by burnout risk, demographics or having worked in critical or respiratory care. Those who had not taken time off were 2.4 times more likely to have applied for specialty training (OR=2.43, 95% CI 1.20 to 5.34).

Interviews

Qualitative analysis identified several ways in which experiences of working and training through the COVID-19 pandemic had shaped decisions about career choices and views of working in medicine in the future. There was a sense that the pressures of the pandemic had exacerbated or revealed pre-existing issues related to working as a doctor in the National Health Service (NHS). Given the current workforce issues in the UK involving postgraduate doctors-in-training, the analysis focused on broader lessons from participants’ experiences of working during COVID-19, rather than on issues directly related to the pandemic. We have omitted data surrounding reasons for choice of specialty except where this also impacted decision-making around entering specialty training, as this was not our intended research outcome.

Themes and subthemes are illustrated in figure 2.

Figure 2. Themes and subthemes constructed from the interview data.

Working in a system under pressure

Many participants’ choices were associated with working in a system under pressure. However, this was not necessarily linked to COVID-19. Many felt that while the pressures of the pandemic had reduced or changed as they had moved through the Foundation programme, there remained other significant pressures within the system. These pressures impacted perceptions of their ability to continue to work within the structured postgraduate training pathway.

‘Stepping off the treadmill’ of postgraduate medical training

Perceptions of the pros and cons of training pathways compared with other forms of clinical work

A primary reason for not entering training was fatigue and a sense of ‘getting off the treadmill’ of medical training. However, this fatigue was not necessarily a consequence of clinical work, but rather of the structure, particularly the lack of flexibility of working, of training programmes.

What I will be getting then is all the good bits of medicine without all the crap. I won’t be having to go to F2 teaching, I won’t be having to do portfolio nonsense, I won’t be having all these meetings… I can just trim off that fat, and just do what I want to do. (Interview 8, did not apply)

Alongside the perceived lack of flexibility and administrative burdens of a formal training programme, participants who had chosen not to apply for training also perceived a lack of educational value in training programmes, or at least that educational value was squeezed out by the pressures of service delivery. In this respect, the pressures of COVID-19 had brought out latent problems in the system not being optimised for education. Anticipated ongoing pressure led some to question the value of entering a training programme in which they may not receive much ‘education’.

As soon as I got busy it was just: switch off the teaching … felt like service provision most of the time, because that’s kind of what we were. We weren't really being trained … because there were fifty patients to see, and you didn’t have the time. (Interview 13, did not apply)

Many felt they could no longer continue working the number of clinical hours they had done in their Foundation training, perceiving locum work as a way of working clinically with greater flexibility and control. With locum shifts being paid more than the hourly rate of a training programme, this meant doctors-in-training needed to work fewer hours to achieve the same level of remuneration, which also had perceived benefits for well-being:

Doing an F3 … I would only be doing locum shifts at maybe three times the hourly rate I work now, I’d only have to work one day a week or two days a week if I want … it becomes sustainable because I can go to work on the day that I’ve picked, the shift that I’ve picked at a time that works for me … I will have enough time in-between to recuperate. (Interview 8, did not apply)

Taking a break for other opportunities

Some participants viewed the end of their Foundation training as a natural pause where they had the opportunity to ‘make up for’ missed opportunities due to the impact of COVID-19, including extended holidays. Others recognised the value of taking time out to reflect on their experiences in the Foundation Programme and feel more mentally ready for the rigours of the training programme and increasing levels of responsibility.

Everyone’s in the same boat. We’ve not had a holiday, we’ve not seen so many people in the last few years, and I think exactly the same. And I think there’s just that part of me that just needs to be away from the hospital for a little bit just to go somewhere different …. The idea of just going straight from F2 straight onto another conveyor belt through straight to specialty training and never having that moment to just stop for even just a short period … I think, I need that. So I think part of my plans going forward are that I might be able to have a month off where I just do the odd locum shift and just have a moment just to process it all. (Interview 13, did not apply)

One participant cited lack of opportunity as an undergraduate student to travel professionally and experience different health systems as a reason for taking an F3 year:

I haven’t applied for specialty training at all simply because I didn’t have that experience to work abroad for my elective and so that’s why I’m taking this year out. (Interview 14, did not apply)

Preparing for the long-term professional demands of a career in medicine

Anticipated future roles and responsibilities

Some participants looked ahead to specific potential roles and the pressures and responsibilities associated with progression through training. The medical registrar (‘med reg’) is a senior role in many UK specialties in which the doctor has wider responsibility and can be called to any medical case or unwell patient. This role is associated with a particularly high workload and level of responsibility, with consequent impact on well-being. One participant described their experience of the intensity of working during the pandemic as deterring them from applying for medical specialties because they recognised it would be detrimental to their well-being:

I cannot imagine working full time and being a med reg, that just seems like a one-way ticket into a bad place. (Interview 8, did not apply)

Personal considerations influenced the decision to proceed to specialty training, and choice of specialty. This was particularly true of those who had entered medicine as a graduate.

I am 30 now … I don’t really want to be only just getting into the peak of my career when I am 40 … going through all the list of things with my mum and having an in-depth discussion made me think ‘oh, maybe GP is for me’. (Interview 7, did apply)

This was, in part, based on perceptions of what the job of a consultant in any given specialty (including general practice) would involve and the challenges anticipated in training to get to that point. Comments from two participants illustrate the different trade-offs between a shorter, but more intense training period, and a longer less pressurised one.

To be perfectly honest, if I had to do eight years as a registrar, doing an [expletive] rota, and working very hard … but at the end of it I got a job for the majority of my adult life, that I enjoyed and I wanted to do, then it’s probably worth having a bit of grief. (Interview 3, did apply)

I am not someone who is going to hurry to become a consultant and then I can have my nice life … I need to make my nice life now. (Interview 5, did apply)

Those who had decided to apply for specialty training during their Foundation Year 2 year often expressed a deep interest or love for their specific specialty choice, and that their personality and strengths were well aligned to a career in their desired specialty:

I think having spent the year working majority - majority of the time in adult medicine, I realised how much I really enjoyed working with kids. And I me - and then I started working in A&E when I got to spend time in paediatric A&E and I - I just loved it. I really liked that – so, it was building on the complex conversations and interactions that I’d developed during my time in the COVID-19 ward, that talking to kids and their parents, interacting, and sort of having those three-way discussions I really liked. So, I made the decision to apply for paediatric specialty training. (Interview 12, did apply)

Being and becoming part of the community of healthcare

Alongside the pressures of day-to-day patient contact and service provision in an increasingly stretched NHS, participants’ perceptions of the community of healthcare, teamworking and support from their seniors and peers also impacted their decision-making.

Feeling valued as a member of the healthcare community

Participants referred to ‘feeling like a number’ or ‘being rota fodder’, with one suggesting that if they were off sick, ‘it would be an inconvenience’ to the hospital, rather than a cause for concern. This was again linked specifically to being a trainee, rather than working clinically per se, with the perception that being part of a training programme obliged doctors to work in a certain way, over which they had minimal control. This eroded their sense of duty towards the system and led them to have less goodwill to work outside of the terms of their contracts.

[Junior doctors] spend six to eight years being told that they’re brilliant and special and then they get put into a system that basically treats them as cannon fodder or rota fodder … they sustain themselves on this feeling that what they’re doing is for a greater purpose. (Interview 8, did not apply)

One source of an underlying disillusionment expressed by some was a perceived lack of respect by those in management roles for junior doctors, and sometimes other clinical members of the interprofessional team, echoing the point of being a cog in the system.

I’ve always found it a very weird mix of being asked to be this independent adult who has to make quite significant clinical life or death decisions, but at the same time, in other areas … you're very much babied or looked down on … you get a slap on the wrist for something that seems quite meaningless … when you've got people dying left, right, and centre around you. (Interview 6, did not apply)

Connections with peers

Some participants felt that the social restrictions associated with COVID-19 in the early stage of their Foundation programme had impacted on their ability to make connections with their peers. Collegiality between peers fosters a sense of belonging in the profession, as well as providing support for emotional well-being. Those who had strong social networks found this useful, and those who had struggled to make these connections felt this had been detrimental to their well-being.

The biggest issue has been the inability to have the same support networks as usual, you couldn’t go socialise with colleagues for most of the year because of the restrictions … you couldn’t make the next level of connection with your colleagues as well as not being able to get things off your chest. (Interview 20, did apply)

Conversely, the presence of supportive teams, especially during times of service pressure, seemed to be an attractor for some specialties:

I’ve applied for ACCS (Acute Care Common Stem) … I did my critical care placement in FY1 … they had a pretty rough time during the pandemic … but during my time in ICU … everyone just really pulled together … was just there for each other … it really confirmed that this is a specialty that I want to do … because of how they’ve looked after trainees or looked after me. (Interview 11, did apply)

Perceptions of the practice and vocation of medicine

A mismatch between expectation and reality of working as a very junior doctor

While practical considerations of work-life balance, flexibility and maintaining well-being were clearly important for participants, these considerations also fed into wider reflections on the meaning of being a doctor. There was a risk of mismatch between expectations of what the work of a doctor would be and the reality of working life. Idealism about the role and nature of medicine, and what it can achieve, was undermined by experiences of the systemic issues of working within the NHS. Many participants directly or indirectly referred to feeling unprepared to work within the constraints of the system.

When I was in medical school, I always had this unbridled optimism about the kind of relentless good the NHS were doing … now, it is very tempered and a bit cynical … I just want to help someone; I don’t want people to constantly tell me there is no capacity or no money. (Interview 2, did not apply)

Some participants reflected on their expectations of what constitutes ‘medicine.’ Conceptions of ‘real medicine’ tend towards direct clinical interactions, rather than the indirect care of administration and teamworking which is a central part of working as a Foundation doctor.

For me doing medicine is not admin, it is not managing, it is not MDT, any of that … when I say medicine, I mean specifically me interacting with a patient who needs something … when I’m doing that, I have value and I feel good. (Interview 8, did not apply)

Discussion

Principal findings

The purpose of this study was to consider how starting work as a doctor during the COVID-19 pandemic had affected trainees’ decision to apply for specialty training. However, the results illustrate broader issues faced by graduate doctors making their immediate career choice. While some of these issues had been thrown into relief by the acute pressures of COVID-19, many were not a direct result of the pandemic, and reflected wider questions around the roles and responsibilities of the postgraduate doctor in training, and perceived value of specialty training programmes.

That said, many participants indicated their experience through the pandemic had affected their decision-making. Those who reported time off for stress were less likely to apply for specialty training. Qualitative data confirmed a desire to protect well-being, rest and recovery.

Our findings show that this desire for a break in training was linked to a sense of working in a system under strain, and frustration or disillusionment with the processes of training. Assessments of work-life balance and workplace culture also played key roles in the decision to apply, or not, and choice of specialty. This extended to a wider disillusionment with working as a junior doctor in the NHS, although significantly this was in part linked to a separation of ‘clinical’ work, ‘the good stuff’, from the realities of working in a system.

Strengths and weaknesses

Strengths of this study include our sequential mixed-methods approach, which allowed exploration of doctors’ experiences and decision-making process from two perspectives, with our quantitative data helping to shape areas of focus in the qualitative interviews. For example, our understanding of high levels of burnout from our quantitative data prompted a focus on fatigue and factors influencing burnout within our qualitative analysis.

Weaknesses of this study include the unavoidable risk of sampling bias. The convenience sample of our survey risks that those with atypical views and experiences may dominate among our respondents. Some demographics are under-represented compared with the graduate population.30 It has been well-documented from the early use of online surveys that women are more likely to respond,31 with potential reasons for this being less clear, but possibly related to gender-influenced online behaviours, with women more likely to engage in information communication and exchange than men, who are more likely to engage in information seeking. Similarly while we attempted to distribute the initial survey as widely as possible, it is unclear why white students were over-represented compared with the population of interest. The variation in response rate between participants of different ethnicities is also poorly understood32; however, we acknowledge that the research team is based in Newcastle, where white medical students and doctors are over-represented compared with the national average, which may have influenced responses. That said, we do have a breadth of experiences and variation in our well-being indicators, as well as a mix of gender and ethnicity, suggesting any such bias may be limited. Although there may be a degree of recall bias in participants’ accounts of the pandemic period, our focus was on their thinking at the point of data collection, and so any bias is part of, rather than confounding our data.

Order effects arising from the sequencing of questions in a questionnaire such as used here cannot be eliminated, and questions on well-being could prime responses on career plans, or vice versa. Our questionnaire was structured such that well-being questions were completed first, and so would not be influenced by reflection on career plans. As career questions related to a decision that had been made, those responses should not have been primed by reflection on well-being.

Overall, we feel that our findings are transferable beyond the context of this study and provide ongoing lessons for addressing well-being and workforce challenges in the future.

Strengths and weaknesses in relation to other studies

Unlike other studies, which have previously explored well-being33 and retention34 as two separate issues, this study explored new doctors’ well-being in association with career decisions. Survey responses suggest a link between certain measures of well-being and decision to enter specialty training immediately after Foundation. Our quantitative data report high levels of burnout among doctors beginning work during COVID-19 (61%), reflecting rates of burnout reported among medical students in the literature.35

Qualitative findings suggested a relationship between well-being—particularly trainees’ awareness of a need to protect their well-being—and seeking more flexible career paths. This echoes literature from emergency medicine reporting a connection between burnout and leaving the medical profession, and between burnout and a desire to create a ‘portfolio’ career, consisting of varied, and often flexible, work.36 The findings also support other work showing the contribution of burnout to both career disengagement and patient safety.37 Trainees reported making choices informed by perceptions of support from seniors, workplace culture and perceived work-life balance (including length of training) to manage their own well-being. This adds depth to previous literature reporting the influence of perceived work-life balance on doctors’ career decisions38 and suggests that the pandemic has intensified this as an influencing factor.

While burnout among our participants was high, interestingly this did not have a direct relationship to the decision to apply for specialty training (ie, those with higher burnout scores were no more likely to take a year out than those with low burnout scores). Almost all of our participants anticipated continuing to work clinically in some capacity. As well as taking breaks from clinical practice, previous literature has described strategies for addressing burnout including the building of meaningful relationships/a community with colleagues; and active choice and autonomy in the kind of work done.39 It is clear that working more flexibly in a non-training role might increase the choice and autonomy of postgraduate doctors; however, choosing to enter a specialty training programme also represents an active choice in doctors defining their scope of practice (when compared with the Foundation Programme, which will often include clinical rotations which are not of interest to the trainee). Entering a specialty training programme also gives the trainee access to a more defined community of doctors working in a specific branch of medicine, which may facilitate the building of more meaningful work relationships grounded in shared clinical interest. Previous small qualitative studies have reported a relationship between professional identity, burnout and intention to leave a specialty40; the professional identity of Foundation doctors and the relationship of this to burnout and career intentions is worth further study, particularly for those who completed their training impacted by COVID-19, as there is early evidence that this has impacted professional identity development.41

A further consideration for our participants was the perceived lack of educational value of training programmes, shaped by their experiences of cancelled teaching and other educational opportunities during the COVID-19 pandemic. For many participants who had elected not to enter specialty training, the ‘pros’ of the specialty training programme in terms of educational opportunities and skill development did not outweigh the ‘cons’ of inflexible rotas and poor working conditions. Previous work defining the role of the Foundation doctor has highlighted similar issues outside of the context of the pandemic.42 Junior doctors regard certain aspects of their job roles (such as paperwork or basic practical tasks) as non-educational and detrimental to their role as a learner in the clinical workplace. Some work with medical students has suggested that educational environment scores are linked to quality-of-life scores,43 suggesting that alongside working conditions, the ability of the clinical workplace to provide an educational experience may be an influencing factor in career decision-making. This is an area that warrants further attention as there is currently limited literature on the educational environments of qualified but still training doctors.

Possible implications for clinicians and policymakers

Our findings offer valuable insights to those responding to the impact of COVID-19 on workforce. Of particular concern is the alarming prevalence of burnout among our sample. This suggests that educational and health systems are not doing enough to support the well-being of trainees, particularly those who entered practice during the pandemic.

The considerable shift among trainees to considering more flexible career paths, such as locum work, has implications for the predictability and robustness of workforce planning. Policy currently focuses on increasing input to training pathways, notably through increasing medical school places,44 but attention to throughput is needed to ensure sufficient trainees at the necessary levels, while avoiding bottlenecks and further risk of disillusionment. The number of vacancies in medical posts remains at 7.2% across the NHS,45 indicating that despite the high fill rates, attrition of full-time trainees throughout the training pathway must be accounted for in workforce planning. Moreover, there are calls to increase the number of specialty training places to match demand46 and any increased numbers will require applicants to fill them, otherwise they risk being withdrawn.

With increasing diversity of the intake of medical students, there are more graduates, mature students and disabled students entering medicine. Postgraduate medical training in the UK has been historically structured around the experiences of young, affluent, primarily white male students.47 This approach may not adequately address the needs of a more diverse population of students. There is often a sense that a desire for flexible working and training is problematic, but there are opportunities in having a mixed economy of full-time, part-time and accelerated training to suit people at different stages of life and with different competing demands. Trainees are managing their own well-being and exerting autonomy in their training pathways, often through taking career breaks. A system that recognises and supports such autonomy may be beneficial for all.

Well-being concerns were not just an influence on the choice of whether to apply for specialty training, but also specialty choice, with considerations of the perceived stresses of training and eventual career destination. Training programmes may need to consider how they are perceived, address negative stereotypes, or mitigate real challenges to well-being.

Unanswered questions and future research

There are several interesting directions for future research. Our findings highlight the shifting preferences for flexible working—future research could explore what specific forms of flexibility are desired by trainees, and, with organisational stakeholders, how these could be implemented and evaluated. Moving forward, the longer term impact of the pandemic on the health workforce impact should be examined longitudinally.

Our findings note the impact of administrative burdens, of which there could be a more in-depth analysis, including exploration of trainees’ relationships with administrative tasks across career stages, and the associations of this relationship to stepping out of training. Perceptions of this appear not to have changed in some years42 and there may be scope for undergraduate curricula and placements to introduce medical students more to these aspects of practice.

Conclusion

This study explores, through a mixed-methods approach, new doctors’ experiences and well-being during COVID-19, and how this relates to their career decision-making at the point of entry into specialty training. There is an ongoing workforce crisis within the UK healthcare system, and our findings indicate this crisis is likely to be sustained in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is critical that policymakers, educational and service leaders take systems-level action to improve working conditions, pastoral support and educational opportunities for postgraduate medical trainees.

supplementary material

Acknowledgements

Anna Goulding, Emma Farrington, Oliver Burton.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration North East and North Cumbria.

Prepublication history and additional supplemental material for this paper are available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-086314).

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study involves human participants and was approved by Newcastle University Research Ethics Committee (ref 14101/2021). Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Data availability free text: Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available. Anonymised quantitative data are available on request, but qualitative data are not available to protect confidentiality. Data inquiries are to be directed to author BB (bryan.burford@newcastle.ac.uk).

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were not involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting or dissemination plans of this research.

Contributor Information

Anna Harvey Bluemel, Email: anna.harvey@newcastle.ac.uk.

Megan E L Brown, Email: megan.brown@newcastle.ac.uk.

Gillian Vance, Email: gillian.vance@newcastle.ac.uk.

Yu Fu, Email: yu.fu@liverpool.ac.uk.

Christopher Price, Email: C.I.M.Price@newcastle.ac.uk.

Bryan Burford, Email: bryan.burford@newcastle.ac.uk.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.

References

- 1.Burford B, Mattick K, Carrieri D, et al. How is transition to medical practice shaped by a novel transitional role? A mixed-methods study. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e074387. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-074387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Solomon-Moore E, Lambert J, Grey E, et al. Life in lockdown: a longitudinal study investigating the impact of the UK COVID-19 lockdown measures on lifestyle behaviours and mental health. BMC Public Health. 2022;22:1495. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13888-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodenheimer T, Pham HH. Primary care: current problems and proposed solutions. Health Aff (Millwood) 2010;29:799–805. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lupu D, Quigley L, Mehfoud N, et al. The growing demand for hospice and palliative medicine physicians: will the supply keep up? J Pain Symptom Manage. 2018;55:1216–23. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2018.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lock FK, Carrieri D. Factors affecting the UK junior doctor workforce retention crisis: an integrative review. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e059397. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-059397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ibrahim F, Samsudin EZ, Chen XW, et al. The prevalence and work-related factors of burnout among public health workforce during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Occup Environ Med. 2022;64:e20–7. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000002428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jewell P, Majeed A. The F3 year: what is it and what are its implications? J R Soc Med. 2018;111:237–9. doi: 10.1177/0141076818772220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Nussbaum C, Massou E, Fisher R, et al. Inequalities in the distribution of the general practice workforce in England: a practice-level longitudinal analysis. BJGP Open. 2021;5:BJGPO.2021.0066. doi: 10.3399/BJGPO.2021.0066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boyle AA, Bhardwaj S. Looking after the emergency medicine workforce: lessons from the pandemic. Emerg Med J. 2023;40:84–5. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2022-213027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Committee of Public Accounts Progress in improving NHS mental health services. Sixty-Fifth Report of Session 2022-23. 2023. https://publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm5803/cmselect/cmpubacc/1000/report.html Available.

- 11.Greig F. COVID-19, medical education and the impact on the future psychiatric workforce. BJPsych Bull. 2021;45:179–83. doi: 10.1192/bjb.2020.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.NHS medical staffing data analysis. https://www.bma.org.uk/advice-and-support/nhs-delivery-and-workforce/workforce/nhs-medical-staffing-data-analysis Available.

- 13.Silverton R. The F3 Phenomenon: exploring a new norm and its implications. 2022. https://www.hee.nhs.uk/sites/default/files/documents/F3_Phenomenon_Final.pdf Available.

- 14.Querido SJ, Vergouw D, Wigersma L, et al. Dynamics of career choice among students in undergraduate medical courses. A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 33. Med Teach. 2016;38:18–29. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1074990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Byrnes YM, Civantos AM, Go BC, et al. Effect of the COVID-19 pandemic on medical student career perceptions: a national survey study. Med Educ Online. 2020;25:1798088. doi: 10.1080/10872981.2020.1798088. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Goudarzi H, Onozawa M, Takahashi M. Future career plans of medical students and the COVID-19 pandemic: Time to recover? J Gen Fam Med . 2022;24:139–40. doi: 10.1002/jgf2.591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Doan LP, Dam VAT, Boyer L, et al. Impacts of COVID-19 on career choices in health professionals and medical students. BMC Med Educ. 2023;23:387. doi: 10.1186/s12909-023-04328-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alrawashdeh HM, Al-Tammemi AB, Alzawahreh MK, et al. Occupational burnout and job satisfaction among physicians in times of COVID-19 crisis: a convergent parallel mixed-method study. BMC Public Health. 2021;21:811. doi: 10.1186/s12889-021-10897-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mittal R, Su L, Jain R. COVID-19 mental health consequences on medical students worldwide. J Community Hosp Intern Med Perspect. 2021;11:296–8. doi: 10.1080/20009666.2021.1918475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Abdelhafiz AS, Ali A, Ziady HH, et al. Prevalence, associated factors, and consequences of burnout among egyptian physicians during COVID-19 pandemic. Front Public Health. 2020;8:590190. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.590190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Amanullah S, Ramesh Shankar R. The impact of COVID-19 on physician burnout globally: a review. Healthcare (Basel) -> Healthc (Basel) 2020;8:421. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8040421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schifferdecker KE, Reed VA. Using mixed methods research in medical education: basic guidelines for researchers. Med Educ. 2009;43:637–44. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2009.03386.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.NHS UK foundation programme. https://foundationprogramme.nhs.uk/ Available.

- 24.GMC GMC approved postgraduate curricula. https://www.gmc-uk.org/education/standards-guidance-and-curricula/curricula Available.

- 25.Burford B, Vance G, Goulding A, et al. Medical graduates: the work and wellbeing of interim foundation year 1 doctors during COVID-19-19. Report for the GMC 2021. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/ media/documents/fiy1-final-signed-off-report_pdf-86836799.pdf Available.

- 26.Kristensen TS, Borritz M, Villadsen E, et al. The copenhagen burnout inventory: a new tool for the assessment of burnout. W & S. 2005;19:192–207. doi: 10.1080/02678370500297720. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.R Core Team R: A language and environment for statistical computing_. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria. 2023.

- 28.Braun V, Clarke V. One size fits all? What counts as quality practice in (reflexive) thematic analysis? Qual Res Psychol. 2021;18:328–52. doi: 10.1080/14780887.2020.1769238. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.GMC The state of medical education and practice in the UK. https://www.gmc-uk.org/about/what-we-do-and-why/data-and-research/the-state-of-medical-education-and-practice-in-the-uk Available.

- 30.GMC Workforce report 2023. https://www.gmc-uk.org/-/media/documents/workforce-report-2023-full-report_pdf-103569478.pdf n.d. Available.

- 31.Smith G. Does gender influence online survey participation?: A record-linkage analysis of university faculty online survey response behavior. ERIC Document Reproduction Service no.ED 501717. Does gender influence online survey participation?: A record-linkage analysis of university faculty online survey response behavior. 2008. https://sjsu.edu/ Available.

- 32.Sykes LL, Walker RL, Ngwakongnwi E, et al. A systematic literature review on response rates across racial and ethnic populations. Can J Public Health. 2010;101:213–9. doi: 10.1007/BF03404376. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Greenberg N, Docherty M, Gnanapragasam S, et al. Managing mental health challenges faced by healthcare workers during covid-19 pandemic. BMJ. 2020;368:m1211. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Buchan J, Charlesworth A, Gershlick B, et al. A critical moment: NHS staffing trends, retention and attrition. London: Health Foundation. 2019.

- 35.Ishak W, Nikravesh R, Lederer S, et al. Burnout in medical students: a systematic review. Clin Teach. 2013;10:242–5. doi: 10.1111/tct.12014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Darbyshire D, Brewster L, Isba R, et al. Retention of doctors in emergency medicine: a scoping review of the academic literature. Emerg Med J. 2021;38:663–72. doi: 10.1136/emermed-2020-210450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.De Hert S. Burnout in healthcare workers: prevalence, impact and preventative strategies. Loc Reg Anesth. 2020;13:171–83. doi: 10.2147/LRA.S240564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hodkinson A, Zhou A, Johnson J, et al. Associations of physician burnout with career engagement and quality of patient care: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2022;378:e070442. doi: 10.1136/bmj-2022-070442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Polidano K, Wenning B, Mallen CD, et al. Betwixt and between student and professional identities: UK medical students during COVID times. SN Soc Sci . 2024;4:53. doi: 10.1007/s43545-024-00844-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Leigh JP, Tancredi DJ, Kravitz RL. Physician career satisfaction within specialties. BMC Health Serv Res. 2009;9:1–2.:166. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-9-166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chakrabarti R, Markless S. More than burnout: qualitative study on understanding attrition among senior Obstetrics and Gynaecology UK-based trainees. BMJ Open. 2022;12:e055280. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-055280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vance G, Jandial S, Scott J, et al. What are junior doctors for? The work of Foundation doctors in the UK: a mixed methods study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e027522. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-027522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Enns SC, Perotta B, Paro HB, et al. Medical students’ perception of their educational environment and quality of life: is there a positive association? Acad Med. 2016;91:409–17. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000000952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Medical Schools Council The expansion of medical student numbers in the United Kingdom. London: MSC. 2021. https://www.medschools.ac.uk/media/2899/the-expansion-of-medical-student-numbers-in-the-united-kingdom-msc-position-paper-october-2021.pdf Available.

- 45.Vacancy rate of the NHS workforce in England from Q1 2018/19 to Q1 2023/24, by staff group [Graph] 2023. https://www.statista.com/statistics/1269990/nhs-england-workforce-vacancy-rate-by-staff-group Available.

- 46.Hadlow J. More medical school places will not automatically mean more junior doctors. 2023. https://www.newstatesman.com/spotlight/healthcare/2023/06/medical-schools-junior-doctors-nhs-workforce-shortage Available.

- 47.Gishen F, Lokugamage A. Diversifying and decolonising the medical curriculum. 2018. https://blogs.bmj.com/bmj/2018/10/18/diversifying-and-decolonising-the-medical-curriculum/ Available. [DOI] [PubMed]