ABSTRACT

The THαβ host immunological pathway contributes to the response to infectious particles (viruses and prions). Furthermore, there is increasing evidence for associations between autoimmune diseases, and particularly type 2 hypersensitivity disorders, and the THαβ immune response. For example, patients with systemic lupus erythematosus often produce anti-double stranded DNA antibodies and anti-nuclear antibodies and show elevated levels of type 1 interferons, type 3 interferons, interleukin-10, IgG1, and IgA1 throughout the disease course. These cytokines and antibody isotypes are associated with the THαβ host immunological pathway. Similarly, the type 2 hypersensitivity disorders myasthenia gravis, Graves’ disease, graft-versus-host disease, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, immune thrombocytopenia, dermatomyositis, and Sjögren’s syndrome have also been linked to the THαβ pathway. Considering the potential associations between these diseases and dysregulated THαβ immune responses, therapeutic strategies such as anti-interleukin-10 or anti-interferon α/β could be explored for effective management.

KEYWORDS: Type 2 hypersensitivity, Tr1, systemic lupus erythematosus, myasthenia gravis, Graves’ disease, graft-versus-host disease

Introduction

The TH17 host immunological pathway contributes to protection against extracellular microorganisms, such as bacteria, fungi, and protozoa. Research on systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), a relatively common autoimmune disorder, has demonstrated a potential association with the TH17 host immunological pathway; however, the relationship is still not clearly established. In particular, SLE autoantibodies typically target anti-double stranded DNA and anti-nuclear antibodies, suggesting that the disease is linked to viral infections, rather than the TH17 pathway [1]. There are literature evidences showing that virus infection can induce anti-ds DNA autoantibodies [2,3]. Although it is possible to extracellularly release of DNA by dying extracellular bacteria, it is still not reasonable that anti-ds DNA antibody is induced by extracellular bacteria. TLR9 sensing CG rich DNA is located in the endosomal location of cells. Thus, extracellular DNA cannot successfully induce TLR9 activation pathway. Only virus infection can induce TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9 to induce THαβ immune reaction. TLR7, TLR8, and TLR9 can induce TH1 immune reaction against intracellular bacteria like Mycobacterium tuberculosis. However, it is still not extracellular DNA released by dying extracellular bacteria to induce TH17 immune reaction. Besides, antibodies need to attack on pathogen surface in order to eliminate the pathogen. Thus, it is more reasonable that host antibodies attack extracellular bacteria cell walls to destroy these pathogens instead of inducing anti-DNA antibodies. The development of autoimmunity in SLE is thought to involve molecular mimicry, particularly through viral infections, such as Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) [4]. We suggest that the THαβ immune response, involved in defense against viruses and prions, is connected to the pathophysiology of SLE and other type 2 hypersensitivity disorders.

In type 2 hypersensitivity, an excessive type 1 interferon response plays a pivotal role in pathophysiology [5,6]. Antibody-mediated cytotoxicity is the hallmark of type 2 hypersensitivity. Several type 2 hypersensitivity disorders, including Sjögren’s syndrome, Graves’ disease, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, immune thrombocytopenia, graft-versus-host disease, dermatomyositis, and myasthenia gravis, do not align with TH1, TH2, or TH17 inflammatory disorders, creating uncertainty regarding their immunopathogenesis. In this context, we present evidence suggesting that these disorders are linked to antiviral THαβ-dominant autoimmune reactions, possibly triggered by viral infections through molecular mimicry. The presence of anti-nuclear antigens in the above-mentioned diseases further supports the notion that these type 2 autoimmune conditions can be classified as THαβ-dominant immune disorders. This perspective adds to our understanding of the immunological mechanisms underlying these diseases and their potential connection to viral infections.

Framework of host immunological pathways

Host immunological pathways can be classified into two primary categories: IgG-dominant eradicable immune reactions and IgA-dominant tolerogenic immune reactions [7–9]. Follicular helper T cells play a crucial role in facilitating the development of eradicable immunity by promoting an antibody class switch from IgM to IgG. Four distinct types of eradicable immune responses (i.e. TH1, TH22, TH2, and THαβ) correspond to different pathogenic entities. TH1 immunity, for instance, specifically combats intracellular microorganisms, including intracellular bacteria, protozoa, and fungi. This categorization improves our understanding of the intricate and specialized roles of different immune pathways in responses to diverse types of pathogens [10]. TH1 immunity involves M1 macrophages, IFNγ CD4 T cells, iNKT1 cells, CD8 T cells (Tc1, EM4), and IgG3 B cells [11,12]. It is linked to type 4 delayed-type hypersensitivity, which results in a delayed immune response. In contrast, TH2 immunity is specifically tailored to combat parasites. Notably, TH2 immunity includes two distinct subtypes, TH2a induced in response to endoparasites (helminths) and TH2b induced in response to ectoparasites (insects), emphasizing the nuanced and specialized nature of the immune response against parasitic invaders [13]. TH2a immunity involves inflammatory eosinophils (iEOS), interleukin-4/interleukin-5 CD4 T cells, mast cell tryptase (MCt), iNKT2 cells, and IgG4 B cells [14–17]. TH2b immunity includes basophils, interleukin-13/interleukin-4 CD4 T cells, mast cells-tryptase/chymase (MCtc), iNKT2 cells, and IgE B cells [18–20]. The TH2 immunological pathway is intricately associated with type 1 allergic hypersensitivity, representing a specific immune response to allergens. In contrast, TH22 immunity serves as the host’s specialized immune reaction targeting extracellular microorganisms (broadly including extracellular bacteria, protozoa, and fungi). The components of TH22 immunity are diverse and include neutrophils (N1), CD4 T cells that produce interleukin-22, iNKT17 cells, and IgG2 B cells [21,22]. TH22 immunity is associated with type 3 immune complex-mediated hypersensitivity. THαβ immunity is the host immunological pathway against infectious particles (viruses and prions) [23–25]. THαβ immunity involves NK cells (NK1), interleukin-10-producing CD4 T cells, iNKT10 cells, CD8 T cells (Tc2,EM1), and IgG1 B cells [26]. THαβ immunity is associated with type 2 antibody-dependent cytotoxic hypersensitivity. CXCR3 and its ligands are associated in THαβ immunity [27].

The immunological pathways classified as tolerogenic are characterized by the dominance of IgA-mediated immune reactions, which are further subdivided into four distinct groups tailored to address different pathogens. Regulatory T cells play a pivotal role in facilitating the development of tolerogenic immune reactions by activating the antibody class switch to IgA [7]. TH1-like immunity is a tolerogenic immune reaction against intracellular microorganisms (intracellular bacteria, protozoa, and fungi). TH1-like immunity involves M2 macrophages, TGF/IFNγ CD4 T cells, iNKT1 cells, CD8 T cells (EM3), and IgA1 B cells [28]. TH1-like immunity is associated with type 4 delayed hypersensitivity. TH9 immunity is a tolerogenic immune reaction against parasites (insects and helminths). TH9 immunity involves regulatory eosinophils (rEOS), basophils, interleukin-9 CD4 T cells, iNKT2 cells, IL-9 related mast cells (MMC9), and IgA2 B cells [29,30]. TH9 immunity is associated with type 1 allergic hypersensitivity. TH17 immunity is a tolerogenic immune reaction against extracellular microorganisms (extracellular bacteria, protozoa, and fungi). The TH17 immune reaction involves neutrophils (N2), interleukin-17 producing CD4 T cells, iNKT17 cells, and IgA2 B cells. TH17 immunity is associated with type 3 immune complex-mediated hypersensitivity [31,32]. TH3 immunity is a host immune reaction to infectious particles (viruses and prions). TH3 immunity involves NK cells (NK2), interleukin-10/TGFβ CD4 T cells, iNKT10 cells, CD8 T cells (EM2), and IgA1 B cells [33,34]. TH3 immunity is associated with type 2 antibody-dependent cytotoxic hypersensitivity.

There is a misleading belief that almost all the autoimmune disorders link to TH17 immunological pathway. For example: asthma is a type 1 autoimmune illness, but it is related to TH2 or TH9 immunological pathway. Multiple sclerosis is a type 4 autoimmune illness, but it is related to TH1 immunological pathway. Thus, it is also reasonable that some autoimmune diseases belong to TH17 immunological pathway and others belong to THαβ immunological pathway. TH17 or TH22 immune reaction is against the infections of extracellular micro-organisms including extracellular bacteria, fungi, and protozoa. THαβ immune reaction is against infectious particles including viruses and prions. The main immune effector cells are neutrophils with cytokines including TNFα, IL-1, and IL-6 in TH17 or TH22 immune response. The main effector cells are NK cells and CTLs with cytokines including IL-10, IL-27, and type 1 interferons in THαβ immune response. Thus, when neutrophils and TNFα play major roles in the pathogenesis of certain autoimmune diseases. These autoimmune diseases are TH17 or TH22 immune related disorders. For example, rheumatoid arthritis is a TH17 or TH22 immune disorder which is related to hyper-activity of neutrophils and TNFα [35]. Thus, we can use Humira, the TNFα inhibitor, to treat rheumatoid arthritis patients and get promising results. However, we cannot to treat SLE, dermatomyositis, and other type 2 hypersensitivities with Humira because they have different pathophysiology. These diseases are THαβ immune responses.

Relationship between the THαβ immunological pathway and SLE

While several previous studies have suggested that the TH17 immune response is related to SLE, this association has not been verified. The TH17 immunological pathway has been proposed to be linked to nearly all autoimmune disorders; however, this concept is flawed. Conditions such as asthma, atopic dermatitis, and allergic rhinitis fall into the category of type 1 autoimmune disorders and are associated with the TH2 or TH9 immunological pathways. In contrast, multiple sclerosis, contact dermatitis, and type 1 diabetes mellitus are classified as type 4 autoimmune diseases and are related to the TH1 immunological pathway. Consequently, the TH17 immunological pathway cannot comprehensively explain the mechanisms underlying all autoimmune disorders. It is crucial to recognize that the TH17 immunological pathway primarily serves as the host defense against extracellular microorganisms, including extracellular bacteria, protozoa, or fungi. The existence of disease-specific anti-nuclear antibodies in SLE is correlated with the host immune response against viruses. The THαβ immunological pathway, which is responsible for host eradicable immunity against viral infections, plays a role in this context. The relationship between SLE and the THαβ immune reaction will be explored further in this article.

The initiation of THαβ immune response involves innate lymphoid cells, specifically ILC10. Additionally, plasmacytoid dendritic cells (DCs) serve as antigen-presenting cells that initiate the THαβ immunological pathway. A previous study established the significance of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in the initiation of SLE [36]. Type 1 interferons (interferons alpha and beta) are mainly produced by plasmacytoid DCs. These cytokines are the first line of defense against viral pathogens invading the host. Type 1 interferons play key roles in the pathogenesis of SLE [37–39]. Monoclonal antibodies against type 1 interferons have been tested in patients with SLE in several clinical trials [40,41]. Type 3 interferons, such as interferon lambda, have similar cellular functions to those of type 1 interferons. Previous studies have also pointed out the relationship between type 3 interferons and the pathogenesis of SLE [42,43].

In addition, we examined the roles of Toll-like receptor (TLR) patterns in initiating antiviral immune reactions. TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9 are the major subtypes that trigger antiviral immune responses. TLR3 is activated by double-stranded RNA. TLR7 and TLR9 are activated by single-stranded RNA. TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9 are located in the endosomal compartments of cells. Their activation can lead to the production of type 1 interferons (interferon alpha and beta) by DCs, especially plasmacytoid DCs. TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9 are all related to the pathophysiology of SLE [44–50]. Thus, TLRs may be therapeutic targets for controlling SLE [44,51].

The central THαβ immunity-related cytokine is interleukin-10, which can activate the immune activities of NK cells and CTL and cause the B cell antibody isotype switch to IgG1. The serum level of interleukin-10 is elevated in patients with SLE [52,53]. Furthermore, anti-interleukin-10 monoclonal antibodies can alleviate symptoms and disease progression in patients with SLE [54–57]. These findings indicate that the THαβ immune reaction plays a key role in the pathogenesis of SLE. Levels of IgG1, the primary antibody used against viral infection, are elevated in patients with SLE. These findings support the hypothesis that SLE is a THαβ immune disorder. CXCR3, IRF5, and IRF7 are also related to SLE pathogenesis [58,59].

In addition to the THαβ eradicable host immunological pathway, TH3 tolerogenic immunity contributes to the response to viral infection [33]. This type of immunity is usually observed during the chronic stage of SLE. A component of the TH3 immunological pathway, serum antibody IgA1 is elevated in patients with chronic SLE [60]. Additionally, the TH3 immunological pathway with Treg cells and TGFβ production can cause kidney fibrosis and eventually lead to renal failure, a common complication of chronic SLE. Thus, TH3 immunity plays a vital role in the pathophysiology of SLE.

Relationship between the THαβ immunological pathway and Sjögren’s syndrome

Sjögren’s syndrome is a type 2 hypersensitivity disorder that manifests as dry eyes, dry mouth, and dry mucosa, indicating an autoimmune condition. These clinical features can also be associated with various viral infections, which must be considered in the differential diagnosis. Furthermore, viral infections, notably EBV infections, have the potential to activate molecular mimicry, leading to the subsequent development of autoimmune Sjögren’s syndrome. Other viral infections, including HIV, HCV, and HTLV, can also cause dry eye, dry mouth, and dry mucosa, mimicking the clinical symptoms and signs of Sjögren’s syndrome [61]. This highlights the importance of recognizing and investigating the role of viral infections in the etiology and pathogenesis of Sjögren’s syndrome [61] and ruling out viral infections before diagnosis. It is likely that Sjögren’s syndrome is associated with the antiviral THαβ immunological pathway. Furthermore, the pathogenesis involves the destruction of cells in the salivary glands, lacrimal glands, and mucosal tissue. This destruction is characterized as type 2 antibody-dependent cytotoxic hypersensitivity that is linked to the anti-viral THαβ immune reaction. These factors collectively indicate that Sjögren’s syndrome can be classified as a THαβ immune disorder.

Sjögren’s syndrome is related to the presence of anti-Ro and anti-La autoantibodies, which are antibodies against RNA molecules (Y RNA), in the serum [62]. Thus, the anti-nucleic acid antibodies associated with Sjögren’s syndrome also support the role of antiviral THαβ immunity. Viral particles can be DNA or RNA viruses. Thus, RNA is an inherited molecule from infectious viruses. Based on the shared role of THαβ autoimmunity, SLE and Sjögren’s syndrome may overlap. TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9 activation is related to the immunopathogenesis of Sjögren’s syndrome [63,64]. These three TLRs respond to DNA and RNA molecules during viral infection. Plasmacytoid DCs, which are antigen-presenting cells that initiate THαβ immunity, are activated in Sjögren’s syndrome. Type 1 and type 3 interferons, which are responsible for THαβ antiviral immunity, are also upregulated in Sjögren’s syndrome [65]. Follicular helper T cells, follicular DCs, and plasmacytoid DCs also play a role in the pathogenesis of Sjögren’s syndrome [66,67]. Follicular DCs are associated with the upregulation of follicular helper T cells. Plasmacytoid DCs are involved in the upregulation of TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9, thereby triggering type 1 interferon responses to initiate THαβ anti-virus host immune reactions. The antiviral antibody subtype IgG1 is the major autoantibody found in Sjögren’s syndrome [62]. The THαβ cytokines interleukin-10 and interleukin-27 are also upregulated in Sjögren’s syndrome and may play key roles in its pathogenesis [68,69]. The TCR repertoire is related to the pathogenesis of Sjögren’s syndrome [70]. Cytotoxic T cells, which are the key effector cells in antiviral THαβ immunity, are also stimulated in Sjögren’s syndrome [71]. Thus, T cell-related cellular immune responses, including THαβ immune reactions, are correlated with the pathophysiology of Sjögren’s disease. STAT1 and STAT3 are the major transcription factors that mediate the antiviral THαβ immunological pathway; both are upregulated in Sjögren’s syndrome [72,73]. CXCR3 is the major chemokine receptor in THαβ-related T lymphocytes. There is also evidence that CXCR3-presenting lymphocytes are correlated with Sjögren’s syndrome [74]. Various CXCR3 ligands, including CXCL9, CXCL10, and CXCL11, are upregulated in tissues involved in Sjögren’s syndrome. NKT and CD56+ NK cells also play vital roles in the pathogenesis of Sjögren’s syndrome [75]. These findings highlight the importance of THαβ immunity in the pathogenesis of Sjögren’s syndrome.

Relationship between the THαβ immunological pathway and myasthenia gravis

Myasthenia gravis is a common type 2 hypersensitivity disorder. It is not a TH1, TH2, or TH17 disorder. We provide evidence that myasthenia gravis is closely related to the THαβ immune response, consistent with its classification as a type 2 hypersensitivity disorder. Autoantibodies for myasthenia gravis are mainly anti-acetylcholine receptor antibodies, typical IgG1 antibodies involved in THαβ immunity [76]. Because acetylcholine receptors are located in the cell membrane of neurons at the neuromuscular junction, anti-acetylcholine receptor IgG1 antibodies can cause neuronal cell antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity via NK cells. NK cell activity is also upregulated in patients with myasthenia gravis. After plasmapheresis for myasthenia gravis treatment, NK cell activity decreases [77]. Interleukin-10 polymorphisms are associated with myasthenia gravis, suggesting that the THαβ immune response is related to this autoimmune disorder [78]. This indicator of cellular immunity contributes to the pathogenesis of myasthenia gravis. Another study reported that interleukin-10 and Tr1 cells (THαβ CD4 T cells) are correlated and upregulated in myasthenia gravis [79]. TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9, related to THαβ immune activation, are overexpressed in the thymus of patients with myasthenia gravis [80,81]. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and IRF5 are also correlated to the pathogenesis and clinical severity of myasthenia gravis [82,83]. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are also associated with thymoma in myasthenia gravis. [82]

Levels of the central antiviral THαβ immune cytokine, interleukin-10, are elevated in patients with myasthenia gravis [84]. Another key THαβ cytokine, interleukin-27, which can induce the production of interleukin-10, is also upregulated in myasthenia gravis [85]. In addition, initiators of THαβ immunity and type 1 interferons are upregulated [86]. These findings suggests that the THαβ immunological pathway plays a vital role in the pathophysiology of myasthenia gravis. Thymomas are often observed in patients with myasthenia gravis. Thymomas are usually associated with the overproduction of CD4 T cells and CD8 T cells. These two lymphocytes, especially cytotoxic CD8 + T cells, are important components of the THαβ immune reaction. Anti-double-stranded RNA, another autoantibody related to viral infection, is also related to the etiology of myasthenia gravis [87]. Viral infection can usually exacerbate myasthenia gravis, highlighting the vital role of the THαβ immunological pathway in disease pathogenesis. EBV, parvovirus, and HSV infections have been reported to be associated with the pathogenesis of myasthenia gravis [88,89]. Chemokine receptors and their ligands CXCR3 and IP10, which are related to THαβ immunity, are overexpressed in T lymphocytes in myasthenia gravis [90].

Relationship between the THαβ immunological pathway and Graves’ disease

Autoimmune thyroiditis encompasses Hashimoto thyroiditis (classified as a type 4 hypersensitivity disorder) and Graves’ disease (classified as a type 2 hypersensitivity disorder). Graves’ disease is associated with hyperthyroidism, whereas Hashimoto’s thyroiditis is associated with hypothyroidism. In Graves’ disease, the presence of autoantibodies leads to thyroid hyperplasia, whereas in Hashimoto thyroiditis, these autoantibodies result in thyroid tissue destruction [91]. This explains the differences in clinical characteristics between the two autoimmune thyroiditis types [92]. Similar to SLE, anti-nuclear antibodies can be detected in autoimmune thyroiditis, especially in Graves’ disease. Anti-double-stranded DNA autoantibodies are also found in patients with Graves’ disease [93]. The chemokine receptor CXCR3 and its ligand CXCL10 are overexpressed in THαβ immune cells, and they are both overexpressed in Grave’s disease [94]. Type 1 and type 3 interferons, including interferon alpha/beta/lambda, are initiators of the THαβ immune response and are overexpressed in Graves’ disease [95]. The transcription factor IRF7, which is related to type 1 interferon expression, is also overexpressed in Graves’ disease. IgG1 is an anti-viral THαβ immune reaction antibody and is the major autoantibody IgG subtype found in Graves’ disease [96]. The central cytokine of the THαβ immunological pathway, interleukin-10, is also overexpressed in this disease [97]. Another important THαβ immunity cytokine, interleukin-27, is also related to the pathophysiology of Grave’s disease. TLR3, TLR7, and TLR9 play vital roles in sensing viral antigens to trigger THαβ immune reactions, and these TLR subtypes are also overexpressed in Graves disease [98]. NK cells are important immune effector cells against viral infections. However, the activity of NK cells is suppressed by thyroid hormones. Thus, decreased NK cell activity is noted in Graves’ disease with hyperthyroidism [99]. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are related to Grave’s disease pathophysiology [100]. Besides, virus infections including enterovirus, HHV6, and Parvovirus link to the pathogenesis of Grave’s disease [101].

Relationship between the THαβ immunological pathway and graft-versus-host disease

Graft-versus-host disease is classified as a type 2 hypersensitivity reaction and is a THαβ-dominant autoimmune disorder. In the context of transplantation, activated NK cells and cytotoxic CD8 T cells originating from the graft target the recipient tissues that possess mismatched MHC molecules, leading to the development of graft-versus-host disease [102]. Antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity is over-activated and CD8 + T cell perforins are overexpressed in this disease. Interleukin-10, the central cytokine in THαβ immunity, is related to the severity of graft-versus-host disease [103]. The THαβ immunity-related chemokine receptor CXCR3 and the cytokines interleukin-15 and interleukin-27 are overexpressed in this disease [104–106]. Type 1 interferons, vital THαβ immunity initiators, are also upregulated in graft-versus-host disease [107]. Transcription factors related to type 1 interferons, IRF3 and IRF7, are also upregulated in graft-versus-host disease [108,109], and STAT1 and STAT3 are activated [110,111]. TLR7 and TLR9, which sense viral nucleic acid antigen, are also upregulated in graft-versus-host disease [112,113]. Signaling factors downstream of these TLRs, including MyD88 and TRIF, are also vital to the pathogenesis of the disease [114]. Antigen-presenting cells for antiviral THαβ immunity, plasmacytoid DCs, are activated in graft-versus-host disease [115]. CXCR3 and anti-DNA IgG1 autoantibody also participate in the pathogenesis in graft-versus-host disease [104,116].

Relationship between the THαβ immunological pathway and immune thrombocytopenia

Immune thrombocytopenia, formerly known as idiopathic thrombocytopenia, is characterized by the immune-mediated destruction of platelets. It can be caused by viral infection and thus is a THαβ-related immune disorder. Anti-nuclear autoantibodies are found in immune thrombocytopenia, particularly in patients with chronic immune thrombocytopenia. B and T cells play important roles in the pathogenesis of immune thrombocytopenia. Additionally, cytotoxic T lymphocytes and plasmacytoid DCs, both of which are important effector cells in the THαβ immunological pathway, play key roles in the pathophysiology [117].

Key cytokines in the THαβ immunological pathway also play key roles in the pathophysiology of immune thrombocytopenia. Genetic polymorphisms in interleukin-10 are related to immune thrombocytopenia [118]. Interleukin-10 is closely associated with disease development and progression [119]. Another important THαβ immunity cytokine, interleukin-27, is elevated in patients with immune thrombocytopenia [120]. Furthermore, interleukin-27 polymorphisms are also associated with the risk of immune thrombocytopenia [121]. Type 1 interferons, initiators of THαβ immunity, are also important in the pathogenesis [122], and many interferon-regulated genes are upregulated in patients with immune thrombocytopenia. IgG1, the antiviral THαβ immunity antibody subtype, is over-expressed in immune thrombocytopenia [123,124].

Signaling pathways involved in THαβ immune reactions are upregulated in immune thrombocytopenia. There is evidence for the upregulation of TLR7 [123], the type 1 interferon signaling-related transcription factor IRF3 and adaptive immunity-related transcription factor NFκB [125], and the master THαβ immune transcription factors STAT1 and STAT3 [126,127]. These results shows that the THαβ immune reaction is important in the pathophysiology of immune thrombocytopenia. NK cells and CXCR3 with its ligand CXCL11 are associated with the pathogenesis of immune thrombocytopenia [128–130]. Many viruses like VZV, rubella, EBV, influenza, and HIV also link to the pathophysiology of immune thrombocytopenia [131].

Relationship between the THαβ immunological pathway and autoimmune hemolytic anemia

Autoimmune hemolytic anemia falls under the category of type 2 autoimmune disorders, wherein red blood cells bound to IgG antibodies are targeted and destroyed by immune cells, leading to hemolysis. This condition is also a THαβ immunological disorder. Notably, our findings provide evidence that type 1 regulatory T cells, specifically THαβ CD4 T cells, play a crucial role in the development and progression of autoimmune hemolytic anemia [132]. Anti-nuclear autoantibodies have also been observed [133,134], suggesting that certain viral-related antigens can trigger autoimmune hemolytic anemia via molecular mimicry. For example, enterovirus 71 can induce autoimmune hemolytic anemia. CD4 and CD8 T cells [135] as well as follicular helper T cells, which initiate eradicable immunity, can promote autoimmune hemolytic anemia [136]. On the other hand, regulatory T cells (Tregs), which drive the tolerogenic immune response, can control autoimmune hemolytic anemia [136]. Plasmacytoid DCs with IRF8 upregulation trigger autoimmune hemolytic anemia [36].

Key THαβ immunological pathway-related cytokines play an important role in triggering autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Interleukin-10 levels are associated with autoimmune hemolytic anemia [137]. There is a positive correlation between interleukin-10 levels and reticulocyte counts and a negative correlation between interleukin-10 and haptoglobin in hemolytic anemia [138]. Type 1 interferons, including interferon alpha and beta, can trigger autoimmune hemolytic anemia [139]. IgG1, an antiviral THαβ immune-related antibody [133], STAT1 and STAT3, [140,141], and the chemokine receptor CXCR3 are involved in the pathophysiology of autoimmune hemolytic anemia [142]. TLR7 and NK cells are also related to the pathogenesis of autoimmune hemolytic anemia [143,144].

Relationship between the THαβ immunological pathway and dermatomyositis

Dermatomyositis is a type 2 autoimmune disorder that specifically falls under the category of inflammatory myopathy. This condition is characterized by elevated interferon levels, particularly type 1 interferon, within the spectrum of inflammatory myopathies [145]. Dermatomyositis is dominated by THαβ cells. The majority of individuals with dermatomyositis exhibit the presence of the Anti-Jo1 autoantibody, which targets histidyl-tRNA synthetase [146]. Because the THαβ immune reaction fights against viruses-derived DNA and RNA molecules, dermatomyositis is associated with antiviral THαβ immunity [147]. B cells, CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, and NK cells are important components of the THαβ immune reaction and are important in the pathogenesis of dermatomyositis [147–151]. The central THαβ immunity-related cytokine interleukin-10 is upregulated in dermatomyositis and is related to its pathophysiology [152–154]. Another important THαβ immune reaction-associated cytokine, interleukin-27, is also over-expressed in dermatomyositis [155]. These findings highlight the importance of THαβ immunity in the pathogenesis of dermatomyositis.

Various components in the signaling pathway of THαβ immunity are overexpressed in dermatomyositis. MHC1, an antigen-presenting molecule for CD8 T cells, is over-represented [156]. The type 1 interferon-related transcription factors IRF3 and IRF7 [157] and JAK signaling (involved in activating STAT immune master transcription factors) are important in the pathogenesis of dermatomyositis [158]. TLR9 and TLR7, which activate anti-viral THαβ immunity, are also upregulated in dermatomyositis [151,159]. CXCR3+ lymphocytes and their ligands CXCL9 and CXCL10 are correlated with the progression of dermatomyositis [160]. These chemokine ligands and receptors are important for mediating THαβ immunity. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells and IgG1 are related to the pathogenesis of dermatomyositis [161,162]. Virus infections like EBV can also link to the pathophysiology of dermatomyositis [163].

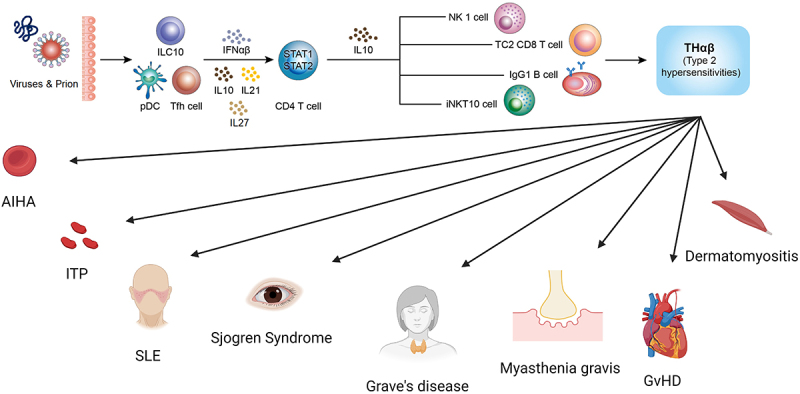

Some of these type 2 autoimmune disorders are systemic, while others are regional. The difference is depending on the autoantibodies. For example: SLE is related to ANA and anti-dsDNA antibodies which will attack on all the human cells with DNA structure that makes SLE a systemic disease [1]. On the other hand, myasthenia gravis is a regional disease. Its autoantibody is the anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody which attacks on the neuro-muscular junction only [76]. This makes myasthenia gravis a regional illness. These point out the importance of autoantibodies which will guide immune cells to attack on general or specific target cells. We made a summary of these points in Table 1 and Figure 1.

Table 1.

Summary of the relationship of THαβ related immune mediators and type 2 hypersensitivities.

| Diseases | TLRs | DCs | Cytokine | Chemokine | Transcription factor | Autoantibody | B cell | T cell | NK cell | Related Viruses |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SLE | TLR3,7,9 | pDC | IFNα/β/λ, IL-10 | CXCR3 | IRF5, IRF7 | Anti-dsDNA, ANA | IgG1, IgA1 | CTLs | NK cell | EBV |

| Sjögren’s syndrome | TLR3,7,9 | pDC, FDC |

IFNα/β/λ, IL-10 IL-27 |

CXCR3, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL11 |

STAT1, STAT3 | Anti-Ro,Anti-La | IgG1 | CTLs | NK cell, NKT cell |

EBV, HIV, HCV,HTLV |

| Myasthenia gravis | TLR3,7,9 | pDC | IL-10 | CXCR3 IP10 |

IRF5 | Anti-AchR, Anti-dsRNA |

IgG1 | CTLs, thymoma |

NK cell | EBV, parvovirus, HSV |

| Grave’s disease | TLR3,7,9 | pDC | IFNα/β/λ, IL-10, IL-27 |

CXCR3, CXCL10 |

IRF7 | TSI, ANA, Anti-dsDNA |

IgG1 | Enterovirus, HHV6, Parvovirus |

||

| GvHD | TLR7,9 TRIF, MyD88 |

pDC | IFNα/β, IL-15, IL-10, IL-27 |

CXCR3 | IRF3, IRF7, STAT1, STAT3 |

Anti-MHC Anti-DNA |

IgG1 | CTLs | NK cell | |

| Immune thrombocytopenia | TLR7 | pDC | IFNα/β, IL-10, IL-27 |

CXCR3, CXCL11 |

IRF3, STAT1, STAT3 |

Anti-platelet antibody, ANA |

IgG1 | CTLs | NK cell | VZV,rubella, EBV,influenza, HIV |

| Autoimmune hemolytic anemia | TLR7 | pDC | IFNα/β, IL-10, |

CXCR3 | IRF8, STAT1, STAT3 |

ANA | IgG1 | CTLs | NK cells | enterovirus |

| Dermatomyositis | TLR7,9 | pDC | IFNα/β, IL-10, IL-27 |

CXCR3, CXCL9, CXCL10 |

IRF3, IRF7 |

Anti-Jo1 | IgG1 | CTLs | NK cells | EBV |

Figure 1.

The anti-viral THαβ immunological pathway and its relations to type 2 hypersensitivity disorders including autoimmune hemolytic anemia, immune thrombocytopenia, systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, grave’s disease, myasthenia gravis, graft versus host disease, and dermatomyositis.

Conclusion

Understanding that the etiologies of type 2 hypersensitivities, encompassing SLE, myasthenia gravis, Graves’ disease, graft-versus-host disease, immune thrombocytopenia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, dermatomyositis, and Sjögren’s syndrome, are linked to the antiviral THαβ immunological pathway, paving the way for the development improved diagnosis and treatment approaches for these debilitating conditions. Current management often involves the use of steroid agents, which, while effective, pose significant risks by affecting adaptive immunity and increasing susceptibility to viral or bacterial infections. If the THαβ immune response is identified as the primary pathogenic mechanism underlying these diseases, a more targeted approach could involve blocking central THαβ cytokines, such as type 1 interferons, interleukin-10, and interleukin-27, using specific inhibitors. This strategic intervention aims to halt disease progression while circumventing infection-related drawbacks associated with steroid treatment. This innovative management strategy holds considerable promise for providing more effective and tailored therapeutic options for autoimmune disorders.

Acknowledgements

The authors would also like to thank the Core Laboratory at the Department of Research, Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation, for their technical support and the use of their facilities.

Funding Statement

This study was supported by grants from the Taipei Tzu Chi Hospital, Buddhist Tzu Chi Medical Foundation [TCRD-TPE-110-02(2/3) and TCRD-TPE-111-01(3/3)].

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Author contributions

YMH, LJS, KWT, TWH and WCH conducted the study and wrote the manuscript. LJS, KCL, and WCH aided in collecting the reference literature and assisted in drafting the manuscript. TWH and YMH were helpful in drafting the manuscript. YMH, LJS, MTL, and WCH handled data processing and created tables and figures. YMH, KWT, KCL, and WCH reviewed the study and edited the manuscript. WCH finally approved the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final work.

Data availability statement

Data sharing not applicable – no new data generated

Ethical statement and consent

This review article examines the literature on type 2 hypersensitivity disorders, including THαβ-dominant autoimmune diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, Grave’s disease, Myasthenia Gravis, immune thrombocytopenia, autoimmune hemolytic anemia, dermatomyositis, and graft-versus-host disease. References were sourced from PubMed and Medline, obviating the need for ethical statements and informed consent for the article’s preparation and completion.

References

- [1].Villalta D, Bizzaro N, Bassi N, et al. Anti-dsDNA antibody isotypes in systemic lupus erythematosus: IgA in addition to IgG anti-dsDNA help to identify glomerulonephritis and active disease. PLOS ONE. 2013;8(8):e71458. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0071458 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Hansen KE; Arnason J; Bridges AJ.. Autoantibodies and common viral illnesses. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 1998;27(5):263–15. doi: 10.1016/s0049-0172(98)80047-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Fredriksen K, Osei A, Sundsfjord A, et al. On the biological origin of anti-double-stranded (ds) DNA antibodies: systemic lupus erythematosus-related anti-dsDNA antibodies are induced by polyomavirus BK in lupus-prone (NZBxNZW) F1 hybrids, but not in normal mice. Eur J Immunol. 1994;24(1):66–70. doi: 10.1002/eji.1830240111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Poole BD, Scofield RH, Harley JB, et al. Epstein-Barr virus and molecular mimicry in systemic lupus erythematosus. Autoimmunity. 2006;39(1):63–70. doi: 10.1080/08916930500484849 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Attallah AM, Folks T. Interferon enhanced human natural killer and antibody-dependent cell-mediated cytotoxic activity. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 1979;60(4):377–382. doi: 10.1159/000232367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Newby BN, Brusko TM, Zou B, et al. Type 1 interferons potentiate human CD8+ T-Cell cytotoxicity through a STAT4- and granzyme B–dependent pathway. Diabetes. 2017;66(12):3061–3071. doi: 10.2337/db17-0106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].Zan H, Cerutti A, Dramitinos P, et al. CD40 engagement triggers switching to IgA1 and IgA2 in human B cells through induction of endogenous tgf-β: evidence for tgf-β but not IL-10-Dependent direct Sμ→Sα and sequential Sμ→Sγ, Sγ→Sα DNA recombination. J Immunol. 1998;161(10):5217–5225. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.161.10.5217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Breitfeld D, Ohl L, Kremmer E, et al. Follicular B helper T cells express CXC chemokine receptor 5, localize to B cell follicles, and support immunoglobulin production. J Exp Med. 2000;192(11):1545–1552. doi: 10.1084/jem.192.11.1545 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Hu WC. A framework of all discovered immunological pathways and their roles for four specific types of pathogens and hypersensitivities. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1992. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Mosmann TR, Cherwinski H, Bond MW, et al. Two types of murine helper T cell clone. I. Definition according to profiles of lymphokine activities and secreted proteins. J Immunol. 1986;136(7):2348–2357. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.136.7.2348 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].Kobayashi N, Kondo T, Takata H, et al. Functional and phenotypic analysis of human memory CD8+ T cells expressing CXCR3. J Leukoc Biol. 2006;80:320–329. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1205725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Tomiyama H, Takata H, Matsuda T, et al. Phenotypic classification of human CD8+ T cells reflecting their function: inverse correlation between quantitative expression of CD27 and cytotoxic effector function. Eur J Immunol. 2004;34(4):999–1010. doi: 10.1002/eji.200324478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Wen TH, Tsai KW, Wu YJ, et al. The framework for human host immune responses to four types of parasitic infections and relevant key JAK/STAT signaling. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(24):13310. doi: 10.3390/ijms222413310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Fort MM, Cheung J, Yen D, et al. IL-25 induces IL-4, IL-5, and IL-13 and Th2-associated pathologies in vivo. Immunity. 2001;15(6):985–995. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(01)00243-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Farne HA, Wilson A, Powell C, et al. Anti-IL5 therapies for asthma. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2017;9:Cd010834. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010834.pub3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Masure D, Vlaminck J, Wang T, et al. A role for eosinophils in the intestinal immunity against infective ascaris suum larvae. PLOS Negl Trop Dis. 2013;7(3):e2138. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Vliagoftis H, Lacy P, Luy B, et al. Mast cell tryptase activates peripheral blood eosinophils to release granule-associated enzymes. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2004;135(3):196–204. doi: 10.1159/000081304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Komai-Koma M, Brombacher F, Pushparaj PN, et al. Interleukin-33 amplifies I g E synthesis and triggers mast cell degranulation via interleukin-4 in naïve mice. Allergy. 2012;67(9):1118–1126. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2012.02859.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Obata K, Mukai K, Tsujimura Y, et al. Basophils are essential initiators of a novel type of chronic allergic inflammation. Blood. 2007;110(3):913–920. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-068718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Romagnani P, De Paulis A, Beltrame C, et al. Tryptase-chymase double-positive human mast cells express the eotaxin receptor CCR3 and are attracted by CCR3-binding chemokines. Am J Pathol. 1999;155(4):1195–1204. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9440(10)65222-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Basu R, O’Quinn DB, Silberger DJ, et al. Th22 cells are an important source of IL-22 for host protection against enteropathogenic bacteria. Immunity. 2012;37(6):1061–1075. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Eyerich S, Eyerich K, Pennino D, et al. Th22 cells represent a distinct human T cell subset involved in epidermal immunity and remodeling. J Clin Invest. 2009;119:3573–3585. doi: 10.1172/JCI40202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Hu WC. Human immune responses to Plasmodium falciparum infection: molecular evidence for a suboptimal THαβ and TH17 bias over ideal and effective traditional TH1 immune response. Malar J. 2013;12(1):392. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-12-392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Hu WC. The central THalphabeta immunity associated cytokine: IL-10 has a strong anti-tumor ability toward established cancer models in vivo and toward cancer cells in vitro. Front Oncol. 2021;11:655554. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2021.655554 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Tsou A, Chen PJ, Tsai KW, et al. THαβ immunological pathway as protective immune response against prion diseases: an insight for prion infection therapy. Viruses. 2022;14(2):408. doi: 10.3390/v14020408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Krovi SH, Gapin L. Invariant natural killer T cell subsets-more than just developmental intermediates. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1393. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Chu YT, Liao MT, Tsai KW, et al. Interplay of chemokines receptors, toll-like receptors, and host immunological pathways. Biomedicines. 2023;11(9):2384. doi: 10.3390/biomedicines11092384 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Prochazkova J, Pokorna K, Holan V. IL-12 inhibits the tgf-β-dependent T cell developmental programs and skews the tgf-β-induced differentiation into a Th1-like direction. Immunobiol. 2012;217(1):74–82. doi: 10.1016/j.imbio.2011.07.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Anuradha R, George PJ, Hanna LE, et al. IL-4–, tgf-β–, and IL-1–dependent expansion of parasite antigen-specific Th9 cells is associated with clinical pathology in human lymphatic filariasis. J Immunol. 2013;191(5):2466–2473. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1300911 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gerlach K, Hwang Y, Nikolaev A, et al. TH9 cells that express the transcription factor PU.1 drive T cell–mediated colitis via IL-9 receptor signaling in intestinal epithelial cells. Nat Immunol. 2014;15(7):676–686. doi: 10.1038/ni.2920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Atarashi K, Tanoue T, Ando M, et al. Th17 cell induction by adhesion of microbes to intestinal epithelial cells. Cell. 2015;163(2):367–380. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.08.058 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Backert I, Koralov SB, Wirtz S, et al. STAT3 activation in Th17 and Th22 cells controls IL-22–mediated epithelial host defense during infectious colitis. J Immunol. 2014;193(7):3779–3791. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1303076 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kumar S, Naqvi RA, Khanna N, et al. Th3 immune responses in the progression of leprosy via molecular cross-talks of tgf-β, CTLA-4 and cbl-b. Clin Immunol. 2011;141(2):133–142. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2011.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].Jiang R, Feng X, Guo Y, et al. T helper cells in patients with chronic hepatitis B virus infection. Chin Med J (Engl). 2002;115(3):422–424. doi: 10.1038/ni.2947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhang N, Pan HF, Ye DQ. Th22 in inflammatory and autoimmune disease: prospects for therapeutic intervention. Mol Cell Biochem. 2011;353(1–2):41–46. doi: 10.1007/s11010-011-0772-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Huang X, Dorta-Estremera S, Yao Y, et al. Predominant role of plasmacytoid dendritic cells in stimulating systemic autoimmunity. Front Immunol. 2015;6:526. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Elkon KB, Stone VV. Type I interferon and systemic lupus erythematosus. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2011;31:803–812. doi: 10.1089/jir.2011.0045 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [38].Elkon KB, Wiedeman A. Type I IFN system in the development and manifestations of SLE. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2012;24(5):499–505. doi: 10.1097/BOR.0b013e3283562c3e [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [39].Eloranta ML, Ronnblom L. Cause and consequences of the activated type I interferon system in SLE. J Mol Med (Berl). 2016;94(10):1103–1110. doi: 10.1007/s00109-016-1421-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [40].Khamashta M, Merrill JT, Werth VP, et al. Sifalimumab, an anti-interferon-α monoclonal antibody, in moderate to severe systemic lupus erythematosus: a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Ann Rheum Dis. 2016;75(11):1909–1916. doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2015-208562 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [41].Morand EF, Furie R, Tanaka Y, et al. Trial of anifrolumab in active systemic lupus erythematosus. N Engl J Med. 2020;382(3):211–221. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1912196 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [42].Amezcua-Guerra LM, Marquez-Velasco R, Chavez-Rueda AK, et al. Type III interferons in systemic lupus erythematosus: association between interferon lambda3, disease activity, and anti-Ro/SSA antibodies. J Clin Rheumatol. 2017;23(7):368–375. doi: 10.1097/RHU.0000000000000581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [43].Goel RR, Wang X, O’Neil LJ, et al. Interferon lambda promotes immune dysregulation and tissue inflammation in TLR7-induced lupus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:5409–5419. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1916897117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [44].Celhar T, Fairhurst AM. Toll-like receptors in systemic lupus erythematosus: potential for personalized treatment. Front Pharmacol. 2014;5:265. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [45].Christensen SR, Kashgarian M, Alexopoulou L, et al. Toll-like receptor 9 controls anti-DNA autoantibody production in murine lupus. J Exp Med. 2005;202(2):321–331. doi: 10.1084/jem.20050338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [46].Ehlers M, Fukuyama H, McGaha TL, et al. TLR9/MyD88 signaling is required for class switching to pathogenic IgG2a and 2b autoantibodies in SLE. J Exp Med. 2006;203:553–561. doi: 10.1084/jem.20052438 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [47].Elloumi N, Fakhfakh R, Abida O, et al. RNA receptors, TLR3 and TLR7, are potentially associated with SLE clinical features. Int J Immunogenet. 2021;48:250–259. doi: 10.1111/iji.12531 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [48].Enevold C, Kjaer L, Nielsen CH, et al. Genetic polymorphisms of dsRNA ligating pattern recognition receptors TLR3, MDA5, and RIG-I. Association with systemic lupus erythematosus and clinical phenotypes. Rheumatol Int. 2014;34(10):1401–1408. doi: 10.1007/s00296-014-3012-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [49].Fillatreau S, Manfroi B, Dorner T. Toll-like receptor signalling in B cells during systemic lupus erythematosus. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2021;17(2):98–108. doi: 10.1038/s41584-020-00544-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [50].Shen N, Fu Q, Deng Y, et al. Sex-specific association of X-linked toll-like receptor 7 (TLR7) with male systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:15838–15843. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1001337107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [51].Horton CG, Pan ZJ, Farris AD. Targeting toll-like receptors for treatment of SLE. Mediators Inflamm. 2010;2010. doi: 10.1155/2010/498980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [52].Baglaenko Y, Manion KP, Chang NH, et al. IL-10 production is critical for sustaining the expansion of CD5+ B and NKT cells and restraining autoantibody production in congenic lupus-prone mice. PLOS ONE. 2016;11(3):e0150515. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0150515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [53].Beebe AM, Cua DJ, de Waal Malefyt R. The role of interleukin-10 in autoimmune disease: systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and multiple sclerosis (MS). Cytokine Growth Factor Rev. 2002;13:403–412. doi: 10.1016/s1359-6101(02)00025-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [54].Sung YK, Park BL, Shin HD, et al. Interleukin-10 gene polymorphisms are associated with the SLICC/ACR damage index in systemic lupus erythematosus. Rheumatol (Oxford). 2006;45(4):400–404. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kei184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [55].Facciotti F, Larghi P, Bosotti R, et al. Evidence for a pathogenic role of extrafollicular, IL-10–producing CCR6 + B helper T cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117(13):7305–7316. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1917834117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [56].Geginat J, Vasco M, Gerosa M, et al. IL-10 producing regulatory and helper T-cells in systemic lupus erythematosus. Semin Immunol. 2019;44:101330. doi: 10.1016/j.smim.2019.101330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [57].Ishida H, Muchamuel T, Sakaguchi S, et al. Continuous administration of anti-interleukin 10 antibodies delays onset of autoimmunity in NZB/W F1 mice. J Exp Med. 1994;179:305–310. doi: 10.1084/jem.179.1.305 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [58].Salloum R, Niewold TB. Interferon regulatory factors in human lupus pathogenesis. Transl Res. 2011;157:326–331. doi: 10.1016/j.trsl.2011.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [59].Wang G, Sun Y, Jiang Y, et al. CXCR3 deficiency decreases autoantibody production by inhibiting aberrant activated T follicular helper cells and B cells in lupus mice. Mol Immunol. 2023;156:39–47. doi: 10.1016/j.molimm.2023.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [60].Conley ME, Koopman WJ. Serum IgA1 and IgA2 in normal adults and patients with systemic lupus erythematosus and hepatic disease. Clin Immunol and Immunopathol. 1983;26(3):390–397. doi: 10.1016/0090-1229(83)90123-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [61].Otsuka K, Sato M, Tsunematsu T, et al. Virus infections play crucial roles in the pathogenesis of Sjögren’s syndrome. Viruses. 2022;14(7):1474. doi: 10.3390/v14071474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [62].Liu Y, Li J. Preferentially immunoglobulin (IgG) subclasses production in primary sjögren’s syndrome patients. Clin Chem Lab Med. 2011;50(2):345–349. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2011.771 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [63].Karlsen M, Hansen T, Nordal HH, et al. Expression of toll-like receptor -7 and -9 in B cell subsets from patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. PLOS ONE. 2015;10(3):e0120383. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0120383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [64].Nakamura H, Horai Y, Suzuki T, et al. TLR3-mediated apoptosis and activation of phosphorylated akt in the salivary gland epithelial cells of primary Sjögren’s syndrome patients. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33(2):441–450. doi: 10.1007/s00296-012-2381-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [65].Bodewes ILA, Versnel MA. Interferon activation in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: recent insights and future perspective as novel treatment target. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2018;14(10):817–829. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2018.1519396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [66].Verstappen GM, Kroese FGM, Bootsma H. T cells in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: targets for early intervention. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2021;60(7):3088–3098. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kez004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [67].Zhao J, Kubo S, Nakayamada S, et al. Association of plasmacytoid dendritic cells with B cell infiltration in minor salivary glands in patients with Sjögren’s syndrome. Mod Rheumatol. 2016;26(5):716–724. doi: 10.3109/14397595.2015.1129694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [68].Bertorello R, Cordone MP, Contini P, et al. Increased levels of interleukin-10 in saliva of Sjögren’s syndrome patients. Correlation with disease activity. Clin Exp Med. 2004;4(3):148–151. doi: 10.1007/s10238-004-0049-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [69].Ciecko AE, Foda B, Barr JY, et al. Interleukin-27 is essential for type 1 diabetes development and Sjögren syndrome-like inflammation. Cell Rep. 2019;29(10):3073–3086.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.11.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [70].Lu C, Pi X, Xu W, et al. Clinical significance of T cell receptor repertoire in primary sjogren’s syndrome. EBioMedicine. 2022;84:104252. doi: 10.1016/j.ebiom.2022.104252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [71].Barr JY, Wang X, Meyerholz DK, et al. CD8 T cells contribute to lacrimal gland pathology in the nonobese diabetic mouse model of Sjögren syndrome. Immunol Cell Biol. 2017;95(8):684–694. doi: 10.1038/icb.2017.38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [72].Pertovaara M, Silvennoinen O, Isomaki P. Cytokine-induced STAT1 activation is increased in patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Clin Immunol. 2016;165:60–67. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2016.03.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [73].Ramos HL, Valencia-Pacheco G, Alcocer-Varela J. Constitutive STAT3 activation in peripheral CD3+ cells from patients with primary Sjögren’s syndrome. Scand J Rheumatol. 2008;37(1):35–39. doi: 10.1080/03009740701606010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [74].Yoon KC, Park CS, You IC, et al. Expression of CXCL9, -10, -11, and CXCR3 in the tear film and ocular surface of patients with dry eye syndrome. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2010;51:643–650. doi: 10.1167/iovs.09-3425 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [75].Baber A, Nocturne G, Krzysiek R, et al. Large granular lymphocyte expansions in primary Sjögren’s syndrome: characteristics and outcomes. RMD Open. 2019;5(2):e001044. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2019-001044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [76].Leite MI, Jacob S, Viegas S, et al. IgG1 antibodies to acetylcholine receptors in ‘seronegative’ myasthenia gravis†. Brain. 2008;131(7):1940–1952. doi: 10.1093/brain/awn092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [77].Chien PJ, Yeh JH, Chiu HC, et al. Inhibition of peripheral blood natural killer cell cytotoxicity in patients with myasthenia gravis treated with plasmapheresis. Eur J Neurol. 2011;18:1350–1357. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2011.03424.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [78].Alseth EH, Nakkestad HL, Aarseth J, et al. Interleukin-10 promoter polymorphisms in myasthenia gravis. J Neuroimmunol. 2009;210(1–2):63–66. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2009.02.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [79].Meng H, Zheng S, Zhou Q, et al. FoxP3(-) Tr1 cell in generalized myasthenia gravis and its relationship with the anti-AChR antibody and immunomodulatory cytokines. Front Neurol. 2021;12:755356. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.755356 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [80].Cavalcante P, Barzago C, Baggi F, et al. Toll-like receptors 7 and 9 in myasthenia gravis thymus: amplifiers of autoimmunity? Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2018;1413(1):11–24. doi: 10.1111/nyas.13534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [81].Robinet M, Maillard S, Cron MA, et al. Review on toll-like receptor activation in myasthenia gravis: application to the development of new experimental models. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2017;52(1):133–147. doi: 10.1007/s12016-016-8549-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [82].Song Y, Xing C, Lu T, et al. Aberrant dendritic cell subsets in patients with myasthenia gravis and related clinical features. Neuroimmunomodulat. 2023;30(1):69–80. doi: 10.1159/000529626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [83].Zagoriti Z, Georgitsi M, Giannakopoulou O, et al. Genetics of myasthenia gravis: a case-control association study in the Hellenic population. Clin Dev Immunol. 2012;2012:484919. doi: 10.1155/2012/484919 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [84].Yapici Z, Tuzun E, Altunayoglu V, et al. High interleukin-10 production is associated with anti-acetylcholine receptor antibody production and treatment response in juvenile myasthenia gravis. Int J Neurosci. 2007;117:1505–1512. doi: 10.1080/00207450601125840 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [85].Jeong HN, Lee JH, Suh BC, et al. Serum interleukin-27 expression in patients with myasthenia gravis. J Neuroimmunol. 2015;288:120–122. doi: 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2015.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [86].Cufi P, Dragin N, Ruhlmann N, et al. Central role of interferon-beta in thymic events leading to myasthenia gravis. J Autoimmun. 2014;52:44–52. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2013.12.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [87].Cufi P, Dragin N, Weiss JM, et al. Implication of double-stranded RNA signaling in the etiology of autoimmune myasthenia gravis. Ann Neurol. 2013;73:281–293. doi: 10.1002/ana.23791 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [88].Cavalcante P, Maggi L, Colleoni L, et al. Inflammation and Epstein-Barr virus infection are common features of myasthenia gravis thymus: possible roles in pathogenesis. Autoimmune Dis. 2011;2011:213092. doi: 10.4061/2011/213092 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [89].Leopardi V, Chang YM, Pham A, et al. A systematic review of the potential implication of infectious agents in myasthenia gravis. Front Neurol. 2021;12:618021. doi: 10.3389/fneur.2021.618021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [90].Feferman T, Maiti PK, Berrih-Aknin S, et al. Overexpression of ifn-induced protein 10 and its receptor CXCR3 in myasthenia gravis. J Immunol. 2005;174:5324–5331. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.174.9.5324 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [91].Nisihara R, Pigosso YG, Prado N, et al. Rheumatic disease autoantibodies in patients with autoimmune thyroid diseases. Med Princ Pract. 2018;27(4):332–336. doi: 10.1159/000490569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [92].Ueki I, Abiru N, Kawagoe K, et al. Interleukin 10 deficiency attenuates induction of anti-tsh receptor antibodies and hyperthyroidism in a mouse graves’ model. J Endocrinol. 2011;209(3):353–357. doi: 10.1530/JOE-11-0129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [93].Pedro AB, Romaldini JH, Americo C, et al. Association of circulating antibodies against double-stranded and single-stranded DNA with thyroid autoantibodies in graves’ disease and hashimoto’s thyroiditis patients. Exp Clin Endocrinol Diabetes. 2006;114(1):35–38. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-873005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [94].Antonelli A, Ferrari SM, Giuggioli D, et al. Chemokine (C–X–C motif) ligand (CXCL)10 in autoimmune diseases. Autoimmun Rev. 2014;13(3):272–280. doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2013.10.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [95].Kim KJ, Lee KW, Choi JH, et al. Interferon-alpha induced severe hypothyroidism followed by Graves’ disease in a patient infected with hepatitis C virus. Int J Thyroidol. 2015;8(2):230. doi: 10.11106/ijt.2015.8.2.230 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [96].Li Y, Zhao C, Zhao K, et al. Glycosylation of anti-thyroglobulin IgG1 and IgG4 subclasses in thyroid diseases. Eur Thyroid J. 2021;10(2):114–124. doi: 10.1159/000507699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [97].Liu N, Lu H, Tao F, et al. An association of interleukin-10 gene polymorphisms with Graves’ disease in two Chinese populations. Endocrine. 2011;40(1):90–94. doi: 10.1007/s12020-011-9444-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [98].Peng S, Li C, Wang X, et al. Increased toll-like receptors activity and TLR ligands in patients with autoimmune thyroid diseases. Front Immunol. 2016;7:578. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [99].Yang Q, Zhang L, Guo C, et al. Reduced proportion and activity of natural killer cells in patients with graves’ disease. Eur J Inflamm. 2020;18:205873922094233. doi: 10.1177/2058739220942337 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [100].Ruiz-Riol M, Armengol Barnils P, Colobran Oriol R, et al. Analysis of the cumulative changes in graves’ disease thyroid glands points to IFN signature, plasmacytoid DCs and alternatively activated macrophages as chronicity determining factors. J Autoimmun. 2011;36(3–4):189–200. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2011.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [101].Weider T, Genoni A, Broccolo F, et al. High prevalence of common human viruses in thyroid tissue. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2022;13:938633. doi: 10.3389/fendo.2022.938633 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [102].Villarroel VA, Okiyama N, Tsuji G, et al. CXCR3-mediated skin homing of autoreactive CD8 T cells is a key determinant in murine graft-versus-host disease. J Invest Dermatol. 2014;134:1552–1560. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [103].Abraham S, Guo H, Choi JG, et al. Combination of IL-10 and IL-2 induces oligoclonal human CD4 T cell expansion during xenogeneic and allogeneic GVHD in humanized mice. Heliyon. 2017;3(4):e00276. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2017.e00276 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [104].Duffner U, Lu B, Hildebrandt GC, et al. Role of CXCR3-induced donor T-cell migration in acute GVHD. Exp Hematol. 2003;31:897–902. doi: 10.1016/s0301-472x(03)00198-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [105].Roychowdhury S, Blaser BW, Freud AG, et al. IL-15 but not IL-2 rapidly induces lethal xenogeneic graft-versus-host disease. Blood. 2005;106(7):2433–2435. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1597 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [106].Belle L, Agle K, Zhou V, et al. Blockade of interleukin-27 signaling reduces GVHD in mice by augmenting treg reconstitution and stabilizing Foxp3 expression. Blood. 2016;128(16):2068–2082. doi: 10.1182/blood-2016-02-698241 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [107].Zhao C, Zhang Y, Zheng H. The effects of interferons on allogeneic T cell response in GVHD: the multifaced biology and epigenetic regulations. Front Immunol. 2021;12:717540. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.717540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [108].Martin-Antonio B, Suarez-Lledo M, Arroyes M, et al. A gene variant in IRF3 impacts on the clinical outcome of acute myeloid leukemia (AML) patients submitted to allogeneic stem cell transplantation (allo-sct). Blood. 2012;120(21):468–468. doi: 10.1182/blood.V120.21.468.46822517895 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [109].Hakim FT, Memon S, Jin P, et al. Upregulation of IFN-Inducible and damage-response pathways in chronic graft-versus-host disease. J Immunol. 2016;197:3490–3503. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1601054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [110].Betts BC, Sagatys EM, Veerapathran A, et al. CD4+ T cell STAT3 phosphorylation precedes acute GVHD, and subsequent Th17 tissue invasion correlates with GVHD severity and therapeutic response. J Leukoc Biol. 2015;97:807–819. doi: 10.1189/jlb.5A1114-532RR [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [111].Ziegler JA, Lokshin A, Sepulveda AR, et al. Role of STAT1 expression during graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in the gastrointestinal tract: association with lamina propria cell infiltration and tissue cytokine/chemokine expression. Blood. 2006;108(11):3175–3175. doi: 10.1182/blood.V108.11.3175.3175 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [112].Calcaterra C, Sfondrini L, Rossini A, et al. Critical role of TLR9 in acute graft-versus-host disease. J Immunol. 2008;181(9):6132–6139. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [113].Suthers AN, Su H, Anand SM, et al. Increased TLR7 signaling of BCR-activated B cells in chronic graft-versus host disease (cGVHD). Blood. 2017;130(Suppl_1):75–75. doi: 10.1182/blood.V130.Suppl_1.75.75 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- [114].Heimesaat MM, Nogai A, Bereswill S, et al. MyD88/TLR9 mediated immunopathology and gut microbiota dynamics in a novel murine model of intestinal graft-versus-host disease. Gut. 2010;59(8):1079–1087. doi: 10.1136/gut.2009.197434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [115].Koyama M, Hashimoto D, Aoyama K, et al. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells prime alloreactive T cells to mediate graft-versus-host disease as antigen-presenting cells. Blood. 2009;113(9):2088–2095. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-168609 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [116].Kim J, Choi WS, Kim HJ, et al. Prevention of chronic graft-versus-host disease by stimulation with glucocorticoid-induced TNF receptor. Exp Mol Med. 2006;38(1):94–99. doi: 10.1038/emm.2006.11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [117].Malik A, Sayed AA, Han P, et al. The role of CD8+ T cell clones in immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2023;141:2417–2429. doi: 10.1182/blood.2022018380 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [118].Tesse R, Del Vecchio GC, De Mattia D, et al. Association of interleukin-(IL)10 haplotypes and serum IL-10 levels in the progression of childhood immune thrombocytopenic purpura. Gene. 2012;505(1):53–56. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.05.050 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [119].Hua F, Ji L, Zhan Y, et al. Aberrant frequency of IL-10-producing B cells and its association with Treg/Th17 in adult primary immune thrombocytopenia patients. Biomed Res Int. 2014;2014:571302. doi: 10.1155/2014/571302 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [120].Hassan T, Abdel Rahman D, Raafat N, et al. Contribution of interleukin 27 serum level to pathogenesis and prognosis in children with immune thrombocytopenia. Medicine (Baltimore). 2022;101(25):e29504. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000029504 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [121].Zhao H, Zhang Y, Xue F, et al. Interleukin-27 rs153109 polymorphism and the risk for immune thrombocytopenia. Autoimmunity. 2013;46(8):509–512. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2013.822072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [122].Yamane A, Nakamura T, Suzuki H, et al. Interferon-α2b–induced thrombocytopenia is caused by inhibition of platelet production but not proliferation and endomitosis in human megakaryocytes. Blood. 2008;112(3):542–550. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-12-125906 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [123].Yang Q, Xu S, Li X, et al. Pathway of toll-like receptor 7/B cell activating factor/B cell activating factor receptor plays a role in immune thrombocytopenia in vivo. PLOS ONE. 2011;6(7):e22708. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0022708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [124].Chan H, Moore JC, Finch CN, et al. The IgG subclasses of platelet-associated autoantibodies directed against platelet glycoproteins IIb/IIIa in patients with idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Br J Haematol. 2003;122(5):818–824. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2141.2003.04509.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [125].Liu Y, Zuo X, Chen P, et al. Deciphering transcriptome alterations in bone marrow hematopoiesis at single-cell resolution in immune thrombocytopenia. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2022;7(1):347. doi: 10.1038/s41392-022-01167-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [126].Chen Z, Guo Z, Ma J, et al. STAT1 single nucleotide polymorphisms and susceptibility to immune thrombocytopenia. Autoimmunity. 2015;48(5):305–312. doi: 10.3109/08916934.2015.1016218 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [127].Li F, Ke Y, Cheng Y, et al. Aberrant phosphorylation of STAT3 protein of the CD4+ T cells in patients with primary immune thrombocytopenia. Blood. 2016;128(22):3740–3740. doi: 10.1182/blood.V128.22.3740.3740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [128].Liu Z, Wang M, Zhou S, et al. Pulsed high-dose dexamethasone modulates Th1-/Th2-chemokine imbalance in immune thrombocytopenia. J Transl Med. 2016;14(1):301. doi: 10.1186/s12967-016-1064-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [129].Wang T, He X, Ran N, et al. Immunological characteristics and effect of cyclosporin in patients with immune thrombocytopenia. J Clin Lab Anal. 2021;35:e23922. doi: 10.1002/jcla.23922 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [130].Barcellini W. New insights in the pathogenesis of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Transfus Med Hemother. 2015;42(5):287–293. doi: 10.1159/000439002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [131].Rand ML, Wright JF. Virus-associated idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura. Transfus Sci. 1998;19(3):253–259. doi: 10.1016/s0955-3886(98)00039-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [132].Ward FJ, Hall AM, Cairns LS, et al. Clonal regulatory T cells specific for a red blood cell autoantigen in human autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Blood. 2008;111(2):680–687. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-07-101345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [133].Sonneveld ME, de Haas M, Koeleman C, et al. Patients with IgG1-anti-red blood cell autoantibodies show aberrant fc-glycosylation. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):8187. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-08654-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [134].Rangnekar A, Shenoy MS, Mahabala C, et al. Impact of baseline fluorescent antinuclear antibody positivity on the clinical outcome of patients with primary autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2023;45:204–210. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2022.01.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [135].Pattanakitsakul P, Sirachainan N, Tassaneetrithep B, et al. Enterovirus 71-induced autoimmune hemolytic anemia in a boy. Clin Med Insights Case Rep. 2022;15:11795476221132283. doi: 10.1177/11795476221132283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [136].Gao Y, Jin H, Nan D, et al. The role of T follicular helper cells and T follicular regulatory cells in the pathogenesis of autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):19767. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-56365-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [137].Toriani-Terenzi C, Fagiolo E. IL-10 and the cytokine network in the pathogenesis of human autoimmune hemolytic anemia. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1051:29–44. doi: 10.1196/annals.1361.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [138].Ahmad E, Elgohary T, Ibrahim H. Naturally occurring regulatory T cells and interleukins 10 and 12 in the pathogenesis of idiopathic warm autoimmune hemolytic anemia. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2011;21(4):297–304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [139].Wang S, Qin E, Zhi Y, et al. Severe autoimmune hemolytic anemia during pegylated interferon plus ribavirin treatment for chronic hepatitis C: a case report. Clin Case Rep. 2017;5(9):1490–1492. doi: 10.1002/ccr3.1098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [140].Xie Y, Shao F, Lei J, et al. Case report: a STAT1 gain-of-function mutation causes a syndrome of combined immunodeficiency, autoimmunity and pure red cell aplasia. Front Immunol. 2022;13:928213. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.928213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [141].Ciullini Mannurita S, Goda R, Schiavo E, et al. Case report: signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 gain-of-function and spectrin deficiency: a life-threatening case of severe hemolytic anemia. Front Immunol. 2020;11:620046. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.620046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [142].Poulet FM, Penraat K, Collins N, et al. Drug-induced hemolytic anemia and thrombocytopenia associated with alterations of cell membrane lipids and acanthocyte formation. Toxicol Pathol. 2010;38(6):907–922. doi: 10.1177/0192623310378865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [143].Fejtkova M, Sukova M, Hlozkova K, et al. TLR8/TLR7 dysregulation due to a novel TLR8 mutation causes severe autoimmune hemolytic anemia and autoinflammation in identical twins. Am J Hematol. 2022;97(3):338–351. doi: 10.1002/ajh.26452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [144].Fattizzo B, Barcellini W. Autoimmune hemolytic anemia: causes and consequences. Expert Rev Clin Immunol. 2022;18:731–745. doi: 10.1080/1744666X.2022.2089115 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [145].Greenberg SA. Dermatomyositis and type 1 interferons. Curr Rheumatol Rep. 2010;12(3):198–203. doi: 10.1007/s11926-010-0101-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [146].Zampieri S, Ghirardello A, Iaccarino L, et al. Anti-jo-1 antibodies. Autoimmunity. 2005;38(1):73–78. doi: 10.1080/08916930400022640 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [147].Fasth AE, Dastmalchi M, Rahbar A, et al. T cell infiltrates in the muscles of patients with dermatomyositis and polymyositis are dominated by CD28null T cells. J Immunol. 2009;183(7):4792–4799. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0803688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [148].Hilliard KA, Throm AA, Pingel JT, et al. Expansion of a novel population of NK cells with low ribosome expression in juvenile dermatomyositis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:1007022. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1007022 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [149].Huang P, Tang L, Zhang L, et al. Identification of biomarkers associated with CD4(+) T-Cell infiltration with gene coexpression network in dermatomyositis. Front Immunol. 2022;13:854848. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2022.854848 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [150].Houtman M, Ekholm L, Hesselberg E, et al. T-cell transcriptomics from peripheral blood highlights differences between polymyositis and dermatomyositis patients. Arthritis Res Ther. 2018;20(1):188. doi: 10.1186/s13075-018-1688-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [151].Piper CJM, Wilkinson MGL, Deakin CT, et al. CD19+CD24hiCD38hi B cells are expanded in juvenile dermatomyositis and exhibit a pro-inflammatory phenotype after activation through toll-like receptor 7 and interferon-α. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1372. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2018.01372 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [152].Greenberg SA, Higgs BW, Morehouse C, et al. Relationship between disease activity and type 1 interferon- and other cytokine-inducible gene expression in blood in dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Genes Immun. 2012;13(3):207–213. doi: 10.1038/gene.2011.61 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [153].Kishi T, Chipman J, Evereklian M, et al. Endothelial activation markers as disease activity and damage measures in juvenile dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 2020;47(7):1011–1018. doi: 10.3899/jrheum.181275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [154].Szodoray P, Alex P, Knowlton N, et al. Idiopathic inflammatory myopathies, signified by distinctive peripheral cytokines, chemokines and the TNF family members B-cell activating factor and a proliferation inducing ligand. Rheumatol (Oxford). 2010;49(10):1867–1877. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keq151 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [155].Shen H, Xia L, Lu J. Pilot study of interleukin-27 in pathogenesis of dermatomyositis and polymyositis: associated with interstitial lung diseases. Cytokine. 2012;60(2):334–337. doi: 10.1016/j.cyto.2012.07.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [156].Li CK, Varsani H, Holton JL, et al. MHC class I overexpression on muscles in early juvenile dermatomyositis. J Rheumatol. 2004;31(3):605–609. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [157].Nombel A, Fabien N, Coutant F. Dermatomyositis with anti-MDA5 antibodies: bioclinical features, pathogenesis and emerging therapies. Front Immunol. 2021;12:773352. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.773352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [158].Ladislau L, Suarez-Calvet X, Toquet S, et al. JAK inhibitor improves type I interferon induced damage: proof of concept in dermatomyositis. Brain. 2018;141(6):1609–1621. doi: 10.1093/brain/awy105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [159].Kim GT, Cho ML, Park YE, et al. Expression of TLR2, TLR4, and TLR9 in dermatomyositis and polymyositis. Clin Rheumatol. 2010;29(3):273–279. doi: 10.1007/s10067-009-1316-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [160].Bellutti Enders F, van Wijk F, Scholman R, et al. Correlation of CXCL10, tumor necrosis factor receptor type II, and galectin 9 with disease activity in juvenile dermatomyositis. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2014;66:2281–2289. doi: 10.1002/art.38676 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [161].McNiff JM, Kaplan DH. Plasmacytoid dendritic cells are present in cutaneous dermatomyositis lesions in a pattern distinct from lupus erythematosus. J Cutan Pathol. 2008;35(5):452–456. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0560.2007.00848.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [162].Xu YT, Zhang YM, Yang HX, et al. Evaluation and validation of the prognostic value of anti-MDA5 IgG subclasses in dermatomyositis-associated interstitial lung disease. Rheumatol (Oxford). 2022;62(1):397–406. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keac229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [163].Peravali R, Acharya S, Raza SH, et al. Dermatomyositis developed after exposure to Epstein-Barr virus infection and antibiotics use. Am J Med Sci. 2020;360:402–405. doi: 10.1016/j.amjms.2020.05.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data sharing not applicable – no new data generated