Abstract

The significance of mental health inequities globally is illustrated by higher rates of anxiety and depression amongst racial and ethnic minority populations as well as individuals of lower socioeconomic status. The COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated these pre-existing mental health inequities. With rising mental health concerns, arts engagement offers an accessible, equitable opportunity to combat mental health inequities and impact upstream determinants of health. As the field of public health continues to shift its focus toward social ecological strategies, the social ecological model of health offers an approach that prioritizes social and structural determinants of health. To capture the impacts of arts engagement, this paper creates an applied social ecological model of health while aiming to advocate that engaging in the arts is a protective and rehabilitative behavior for mental health.

Keywords: mental health, arts in public health, mental health equity, social ecological model, health promotion, health behaviors

Introduction

Depression impacts approximately 280 million people worldwide. 1 Further, clear mental health inequities are evidenced by significantly higher rates of both anxiety and depression among racial and ethnic minority populations as well as individuals of lower socioeconomic status. 2 According to the National Institute of Health (NIH), an estimated one in five adults in the United States (U.S.) suffers from mental illness. 3 Notably, clear mental health inequities exist for marginalized and vulnerable U.S. populations. According to the NIH, 51.8% of White Americans with any mental illness received mental health services in 2020, compared to 37.1% of Black Americans and 35.1% of Hispanic Americans. 3 These disparities in access to care across marginalized populations often stem from socioeconomic barriers. 4 The American Psychological Association 5 has even identified lower socioeconomic status itself as a risk factor for mental illness. Further, marginalized or vulnerable populations that experience mental illness are often subject to compounding effects of stressful life events (SLEs) such as “abject or perceived racism, a dearth of education, communal violence, single-family households, or substance abuse” (p.604). 2 The COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated these pre-existing mental health inequities. 6 During the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported an unprecedented 25% increase in the global prevalence of anxiety and depression. 7 Today, innovative and interdisciplinary approaches are urgently needed to address the scale of these heightened mental health inequities.

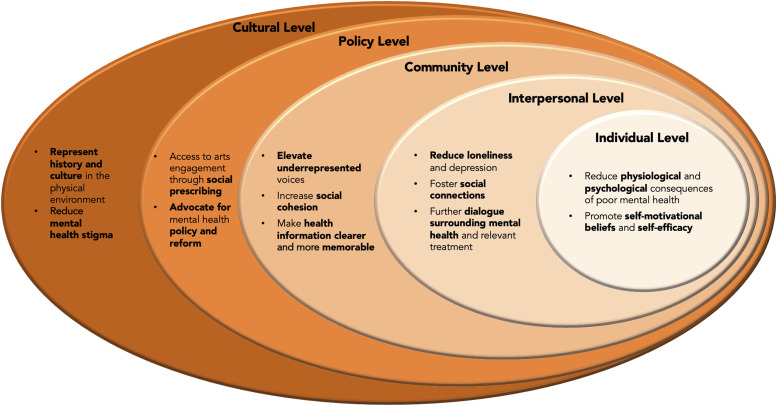

The social ecological model of health promotion, developed by McLeroy et al., 8 helps illustrate that health is affected by multiple contexts ranging from individual factors to interpersonal, community, and policy influences. In 2020, Golden and Wendel adapted the social ecological model of health (SEMoH) by adding a cultural level, recognizing that culture and sociocultural norms affect all other social ecological contexts. 9 These models help visualize the fact that health inequities are fundamentally produced by the inequitable distribution of upstream drivers of health. Thus, the scope and range of the SEMoH offers a well-aligned approach to addressing the highly prevalent issue of mental health inequities.

The broad perspective of the SEMoH indicates the importance of utilizing interdisciplinary approaches which can integrate multiple contexts and experiences. One such approach is arts engagement, which has been shown to support mental health and ameliorate consequences of mental health inequities across multiple spheres of influence. 10 Engagement in the arts can also concurrently promote a greater sense of wellbeing, combat racism, address collective trauma, promote social inclusion, and support social, cultural, and policy change.10–15 Furthermore, according to a scoping review from the WHO, engagement in the arts not only promotes physical and mental health, but when considering prevention and promotion, can also affect social determinants of health by offering accessible health promotion and building community capacity. 10 Therefore, as it relates to prioritizing marginalized communities, arts engagement may offer an accessible, equitable approach.

This paper aims to advocate that arts engagement is a protective and rehabilitative behavior for mental health. An applied version of the SEMoH, depicted in Figure 1, offers evidence for this rationale by considering application at the individual, interpersonal, community, policy, and cultural levels.

Figure 1.

Applied Social Ecological Model of Health (SEMoH). Note. An Applied Social Ecological Model of Health as adapted from Golden and Wendel; 9 This model is available on University of Florida’s Center for Arts in Medicine’s website – www.arts.ufl.edu/academics/center-for-arts-in-medicine/researchandpublications/.

Individual Level

The individual level, the innermost level of the SEMoH, is characterized by an individual’s beliefs, attitudes, knowledge, self-concepts, behaviors, and skills.8,9 For mental health, there are several mechanisms by which the arts can be utilized for preventative and rehabilitative measures. Engagement with music can reduce physiologically and psychologically negative impacts of stress.16,17 Physiologically, observing or engaging with the arts, through all its diverse modes, can reduce blood pressure, cortisol levels, and heart rate — each of which can impact behaviors and skills.18–20 Psychologically, emotional states can be affected as well; for instance, engaging with art personally perceived as pleasant increases the relative intensity of emotional valence leading to a stress-reducing effect which can affect attitudes and self-concepts.10,16 Additionally, arts engagement promotes self-motivational beliefs and therefore enhances self-efficacy.21,22

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA)’s 2021 National Survey on Drug Use and Health, “Black adults were less likely than White adults to receive treatment for depression (51.0 vs. 64.0 percent)” (p.56). 23 Further, low rates of mental health service utilization are often associated with barriers to access including the propensity and ability to use services as well as one’s insurance and capacity to afford health services. 24 Given the disparities associated with the accessibility of mental health services, the arts present an opportunity to reduce burdens on the healthcare system through more easily affordable, preventative measures.10,25 The benefits of increased accessibility have been demonstrated in the context of suicide prevention and survivorship as illustrated in a systematic review conducted by Sonke et al. 26 As it pertains to vulnerable and marginalized individuals, forms of arts engagement present an equitable, economically accessible opportunity to reduce negative consequences of mental health while bolstering protective attributes of mental health and wellbeing.

Interpersonal Level

The second level, the interpersonal level, considers relationships such as family, friends, neighbors, workplace associates, and acquaintances that act as “sources of influence in health-related behaviors” (p.356).8,27 Important considerations include strengths of social networks and social support systems.8,27 As it relates to mental health, there is a strong association between loneliness and depression 28 — a pertinent concern since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. According to a research brief published by the WHO, the prevalence of anxiety and depression surged dramatically worldwide by 25% in the first year of the COVID-19 pandemic. 7 Induced by the pandemic, social isolation was a driving factor for this exceptional rise as the pandemic’s far-reaching effects were worsened by people’s incapacity to work, participate in, and engage with their communities. 7 As communities continue to heal, arts engagement can act in conjunction with other interventions to reduce the effects of both loneliness and isolation as they pertain to depression.29,30 Additionally, arts engagements foster social connection amongst people through “social opportunities, sharing, commonality and belonging, and collective understanding” (p.1).13,31

Another valuable facet of arts engagement at this level is its ability to promote dialogue. 32 Given prevalent stigma surrounding mental health, individuals may be reluctant to speak with peers about their mental health experiences or to seek out care.33,34 Additionally, forms of racial discrimination, such as verbal harassment or hate crime, further compound the effects of this stigma.35,36 As such, engaging in art, especially forms that promote empathy and understanding, can support meaningful discussions that can promote connectedness and the use of mental health resources.10,37

Community Level

Community, as it pertains to the SEMoH, considers structures of power, relationships amongst organizations, and how those structures and relationships are mediated.8,9 Low health literacy is a key impeding factor to community level health and is defined by the U.S. Institute of Medicine as a limited capacity to obtain, process, and understand the basic health information and services needed to make informed health decisions. 38 Vulnerable and marginalized populations, including older adults, people with disabilities, people of lower socio-economic status, racial or ethnic minorities, and people with limited English proficiency or formal education, frequently have low health literacy rates. 39 In communities, arts engagement can make health information clearer and more memorable by improving awareness of health issues and available resources as well as by increasing the sharing of knowledge.13,40 Such improvements and increases may associate with individual and collective perceptions of thriving, an assets-based concept similar to wellbeing. A greater sense of thriving may also have direct effects on multiple health outcomes as people establish meaningful relationships, connections, and fulfillment through arts-based participation in their communities. 41

Positive outcomes associated with participatory arts engagement include social cohesion 42 and wellbeing. 12 Arts engagement increases potential for social cohesion by generating social capital, 43 prosocial cooperation, 44 and community capacity building. 45 Moreover, participatory arts engagement elevates underrepresented voices46,47 and builds resilience in communities 48 by highlighting community health needs and priorities. 27

An example of an arts-based practice associated with community-level health outcomes is photovoice. Photovoice is a photography and storytelling-based qualitative data-collection methodology that emphasizes participant perspectives. It is used to elevate underrepresented voices, such as immigrant youth in the U.S., by empowering participants to contextualize and express their lived experiences. 27 Photovoice can offer people who may not be proficient in a given language the opportunity to share their perspectives visually as well as allow for youth perspectives to be centered in policy making narratives.49,50 Additionally, the use of photovoice also promotes accessibility to and retention of information through its photo-based approach to data dissemination and can encourage critical reflections upon traditional viewpoints of power.51,52 Overall, considering the dynamic interplay between psychological, physical, and social variables, associations between arts engagement and wellbeing at the community level may be critical to addressing the exacerbated mental health crises.10,53

Policy Level

Policy, the next level of the SEMoH, guides and impacts the practice of public health.8,27 Policies encompass “actions, structures and expectations” (p.14); 54 they affect health through the restriction or promotion of behaviors while guiding change across social ecological levels. As it relates to the arts, health care and social service policies can be designed to provide the public, and especially the underserved, with additional access to arts-based experiences that support personal health and wellbeing.55,56 This is especially important given the social gradient in arts engagement within the U.S. . 57 Social prescribing — a practice used in the United Kingdom (U.K.) and other countries to support mental health — recognizes that health and wellbeing must be addressed by improving social determinants of health. This involves connecting patients to non-clinical services ranging from diverse forms of arts participation to engagement with local community-based resources such as housing assistance, jobs training, or food pantries.58,59 Benefits of social prescribing have included increased mental wellbeing, decreased need for clinical health services, and promotion of health equity while allowing for creativity, meaning making, and the formation of new relationships.55,60,61 Social prescribing is a component of the national health system in the U.K.; 55 in the U.S., pilot studies are exploring feasible mechanisms for implementing social prescribing, exemplified through the CultureRx Initiative. 59

Policies supporting arts engagement can advance mental health policy and advocacy efforts.62,63 As indicated by a scoping review led by Sonke et al., 64 art advances mental health education and advocacy by creating innovative forms of health communication which increase public awareness. It can also offer new means of data collection that emphasize unique, and often overlooked, perspectives.65,66 Additionally, photovoice is a particularly valuable modality for equitably leveraging policy as it can foster critical dialogue surrounding direct perspectives of vulnerable populations. 67 Photovoice can also enable a strengths-based approach to policy making by visually depicting both the needs and assets of a community. 67

Cultural Level

The cultural level of the SEMoH encompasses social and cultural norms such as stigma, which remains a critical public health issue as it continues to restrict access to adequate healthcare and acts as a cause of persisting population health inequalities. 68 More specifically, stigma creates a barrier for persons who require mental health services but are hesitant or unwilling to seek assistance due to the possibility of prejudice and rejection from others. 69 The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services has considered stigma “the most formidable obstacle to future progress in the area of mental illness and health” (p.29). 70 Further, racism can compound this issue. Notably, after the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, heightened forms of stigma, racist harassment, sentiment, and violence against Black and Asian American populations in the U.S. have markedly contributed to the “increased risk of depression and anxiety via vicarious racism and vigilance” (p.508). 71

Arts and culture together can cultivate spaces that facilitate discussion around racial stereotypes which perpetuate mental health ailments as well as stigmatized aspects of mental health itself.72–74 Arts-based experiences, including installations and performances, have the capacity to transform participants’ perspectives including their “sense of being alone, or of being unable to articulate or share their experience” (p. 43). 75 This effect was examined through the Porch Light program, an arts engagement initiative which allowed community members to collaborate with artists to work on public murals that illustrated a broad spectrum of experiences with mental illness. 76 This initiative increased perceived safety and reduced mental health stigma amongst participants and residents while increasing social cohesion and trust.76,77 As such, the inclusion of cultural ecologies in the SEMoH emphasizes the importance of incorporating creativity and cultural collaboration into community development to create unique, culturally responsive, and deep-rooted initiatives that can address the mental health concerns of stigma and build toward community-wide wellbeing.

Promising Practices

To equitably address wide-spanning issues stemming from mental health experiences, it is imperative to consider modalities which employ multiple levels of the SEMoH. 9 With health equity as a central goal, arts-based initiatives have the capacity to propel theory into practice by cultivating wellbeing and health. The exemplar programs below utilize arts engagement to promote mental health across multiple levels of influence.

UnLonely Film Festival

Project UnLonely, a national initiative by the Foundation for Art & Healing, 78 is supported by partnerships with the AARP Foundation, Cigna, Americans for the Arts, and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. It aims to expand public awareness of negative mental and physical health outcomes associated with loneliness, empowering both individuals and communities alike to connect with one another through art. Its annual UnLonely Film Festival curates award-winning short films which represent the loneliness epidemic while amplifying lived experiences with isolation. Its “front row” program promotes the films by customizing content suites for organizations, and its “film screening series” provides engaged group discussion and activities after viewing. Acting at the individual, interpersonal, and community levels, it addresses equity and caters to urgent needs by focusing on several vulnerable populations: older adults, employees, college students, and individuals with marginalized identities. Over 100 films are publicly available to raise awareness about loneliness and its effects while reminding viewers that they are not alone.

Project: Music Heals Us

Project: Music Heals Us 79 provides marginalized communities access to interactive programming and music performances to encourage, educate, and heal. It prioritizes disabled, elderly, homeless, and incarcerated populations. Acting at the community level, this project aims to make health information clearer while empowering communities, improving awareness around pertinent health issues, and sharing available resources. To realize its mission, three programs are utilized: a) Novel Voices: Distance Learning – free workshops and concerts for refugees that raise support and awareness for refugee-aid programs; b) Music for the Future: Prison Program – single-day concerts, week-long musical immersion programs, and year-long programming for incarcerated individuals led by classical musicians; and c) Vital Sounds Initiative: Virtual Bedside Concerts – live concerts in clinical settings, implemented after the onset of COVID-19, have reached over 10,000 patients with 1,700 concerts performed.

CultureRx

CultureRx employs a social prescribing framework to build public infrastructure to support the promotion of cultural experiences as protective factors for health and wellbeing. 59 Mass Cultural Council developed and funded CultureRx as a social prescription pilot program involving partnerships with twenty healthcare providers and twelve cultural organization grantees across the state of Massachusetts. The initiative allows healthcare providers to refer patients or clients to arts and culture experiences, which are then offered free of charge. As indicated by CultureRx’s evaluation data, providers are “excited about” and “recommend [the] expansion” of social prescribing; they see it as promoting overall wellbeing and improved health outcomes through a focus on increasing equitable access to upstream determinants of health (p.32).59,80–83

Conclusion

This work suggests that arts engagement can address mental health inequities while impacting upstream determinants of health. We account for interactions between the social ecological model of health and arts engagement to provide an integrated view of the value and power of the arts to facilitate positive mental health outcomes at individual, interpersonal, community, cultural, and policy levels. Arts engagement can act as a protective and rehabilitative behavior for mental health while also redefining and strengthening health at each of these levels. Use of the arts acknowledges mental health inequities by communicating their holistic and contextualized nature. The promising practices described above put theory into practice in this regard.

As the field of public health continues to shift its focus from individual to collective health behaviors, it is imperative to recognize that merely acknowledging the factors beyond the individual is no longer sufficient. This acknowledgment must inform and guide future practice to ensure the consideration of barriers and inequities while advancing health promotion. Promising future directions include community-led design, implementation, assessment, and evaluation of arts-based methods as means to positive mental health outcomes, particularly in marginalized and minoritized communities. It is essential to consider the impacts of inequities and culture while employing an interdisciplinary approach which looks beyond siloed practices.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs

Alexandra K. Rodriguez https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9254-3392

Tasha L. Golden https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8442-4967

Seher Akram https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7215-0249

References

- 1.World Health Organization [WHO] . Depression, 2021, https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/depression [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bailey RK, Mokonogho J, Kumar A. Racial and ethnic differences in depression: Current perspectives. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat 2019; 15: 603–609, DOI: 10.2147/NDT.S128584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.National Institute of Health [NIH] . Mental illness. National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), 2020, https://www.nimh.nih.gov/health/statistics/mental-illness [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tristiana RD, Yusuf A, Fitryasari R, et al. Perceived barriers on mental health services by the family of patients with mental illness. Int J Nurs Sci 2018; 5(1): 63–67, DOI: 10.1016/j.ijnss.2017.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.American Psychological Association . Low socioeconomic status is a risk factor for mental illness. American Psychological Association, 2005, https://www.apa.org/news/press/releases/2005/03/low-ses [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fortuna LR, Tolou-Shams M, Robles-Ramamurthy B, et al. Inequity and the disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on communities of color in the United States: The need for a trauma-informed social justice response. Psychol Trauma 2020; 12(5): 443–445, DOI: 10.1037/tra0000889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization [WHO] . COVID-19 pandemic triggers 25% increase in prevalence of anxiety and depression worldwide, 2022, https://www.who.int/news/item/02-03-2022-covid-19-pandemic-triggers-25-increase-in-prevalence-of-anxiety-and-depression-worldwide. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McLeroy KR, Bibeau D, Steckler A, et al. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ Q 1988; 15(4): 351–377, DOI: 10.1177/109019818801500401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Golden TL, Wendel ML. Public health’s next step in advancing equity: Re-evaluating epistemological assumptions to move social determinants from theory to practice. Frontiers in Public Health 2020; 8: 131, DOI: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fancourt D, Finn S. What is the evidence on the role of the arts in improving health and well-being?: a scoping review (Health Evidence Network Synthesis Report No. 67. World Health Organization, 2019, pp. 1–146, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK553773/ [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Golden T, Sonke J, Francois S, et al. Creating healthy communities through cross-sector collaboration. Florida, FL: University of Florida Center for Arts in Medicine/ArtPlace America, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pesata V, Colverson A, Sonke J, et al. Engaging the arts for wellbeing in the United States of America: A scoping review. Front Psychol 2021; 12: 791773, DOI: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.791773. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sonke J, Golden T, Francois S, et al. Creating healthy communities through cross-sector collaboration [White paper]. Florida, FL: University of Florida Center for Arts in Medicine/ArtPlace America, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sonke J, Golden T. Arts and culture in public health: an evidence-based framework. Florida, FL: University of Florida Center for Arts in Medicine, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 15.World Health Organization [WHO] . Healing arts launch event: the arts and wellbeing. Geneva: World Health Organization, 2021. b. [Google Scholar]

- 16.de Witte M, Spruit A, van Hooren S, et al. Effects of music interventions on stress-related outcomes: a systematic review and two meta-analyses. Health Psychol Rev 2020; 14(2): 294–324, DOI: 10.1080/17437199.2019.1627897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finn S, Fancourt D. The biological impact of listening to music in clinical and nonclinical settings: a systematic review. Prog Brain Res 2018; 237: 173–200, DOI: 10.1016/bs.pbr.2018.03.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hodges DA. Psychophysiological measures. In: Juslin PN, Sloboda J. (eds). Handbook of music and emotion. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2011, pp. 279–311. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Koelsch S, Boehlig A, Hohenadel M, et al. The impact of acute stress on hormones and cytokines, and how their recovery is affected by music-evoked positive mood. Sci Rep 2016; 6: 23008. DOI: 10.1038/srep23008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Linnemann A, Ditzen B, Strahler J, et al. Music listening as a means of stress reduction in daily life. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015; 60: 82–90. DOI: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2015.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fancourt D, Finn S, Warran K, et al. Group singing in bereavement: Effects on mental health, self-efficacy, self-esteem and well-being. BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care, Bmjspcare-2018-001642 2019. Advance online publication. DOI: 10.1136/bmjspcare-2018-001642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Varela W, Abrami PC, Upitis R. Self-regulation and music learning: A systematic review. Psychol Music 2014; 44(1): 55–74. DOI: 10.1177/0305735614554639. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA] . Key substance use and mental health indicators in the United States: results from the 2021 national Survey on Drug use and health, 2023, pp. 1–162. [Google Scholar]

- 24.National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine . Health-care utilization as a proxy in disability determination. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2018, DOI: 10.17226/24969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Burkhardt J, Brennan C. The effects of recreational dance interventions on the health and well-being of children and young people: A systematic review. Arts & Health 2012; 4(2): 148–161, DOI: 10.1080/17533015.2012.665810. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sonke J, Sams K, Morgan-Daniel J, et al. Systematic review of arts-based interventions to address suicide prevention and survivorship in Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America. Health Promot Pract 2021. a; 22(1_suppl): 53S–63S, DOI: 10.1177/1524839921996350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Golden T. Reframing photovoice: Building on the method to develop more equitable and responsive research practices. Qual Health Res 2020; 30(6): 960–972, DOI: 10.1177/1049732320905564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erzen E, Çikrikci Ö. The effect of loneliness on depression: a meta-analysis. Int J Soc Psychiatry 2018; 64(5): 427–435, DOI: 10.1177/0020764018776349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Poscia A, Stojanovic J, La Milia DI, et al. Interventions targeting loneliness and social isolation among the older people: An update systematic review. Exp Gerontol 2018; 102: 133–144, DOI: 10.1016/j.exger.2017.11.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tymoszuk U, Perkins R, Fancourt D, et al. Cross-sectional and longitudinal associations between receptive arts engagement and loneliness among older adults. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2020; 55(7): 891–900, DOI: 10.1007/s00127-019-01764-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Perkins R, Mason-Bertrand A, Tymoszuk U, et al. Arts engagement supports social connectedness in adulthood: findings from the HEartS survey. BMC Public Health 2021; 21(1): 1208, DOI: 10.1186/s12889-021-11233-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Boydell K, Gladstone BM, Volpe T, et al. The production and dissemination of knowledge: a scoping review of arts-based health research. Forum Qualitative Sozialforschung/Forum: Qualitative Social Research 2012; 13(1), DOI: 10.17169/fqs-13.1.1711. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bharadwaj P, Pai MM, Suziedelyte A. Mental health stigma. Economics Letters 2017; 159: 57–60, DOI: 10.1016/j.econlet.2017.06.028. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sickel AE, Seacat JD, Nabors NA. Mental health stigma update: A review of consequences. Advances in Mental Health 2014; 12(3): 202–215, DOI: 10.1080/18374905.2014.11081898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 35.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Raising awareness of hate crimes and hate incidents during the COVID-19 pandemic, 2022, pp. 1–42. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wong EC, Collins RL, McBain RK, et al. Racial-Ethnic differences in mental health stigma and changes over the course of a statewide campaign. Psychiatr Serv 2021; 72(5): 514–520, DOI: 10.1176/appi.ps.201900630A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Twardzicki M. Challenging stigma around mental illness and promoting social inclusion using the performing arts. J R Soc Promot Health 2008; 128(2): 68–72, DOI: 10.1177/1466424007087804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Health Literacy , Panzer AM, Kindig DA. (eds) Health literacy: a prescription to end confusion. National Academies Press (US), 2004. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schillinger D. Social determinants, health literacy, and disparities: intersections and controversies. Health Lit Res Pract 2021; 5(3): e234–e243, DOI: 10.3928/24748307-20210712-01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Postlethwait R, Ike JD, Parker R. Nurturing context: TRACE, the arts, medical practice, and health literacy. Stud Health Technol Inform 2020; 269: 439–452, DOI: 10.3233/SHTI200055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Golden T. From absence to presence: arts and culture help us redefine “health”. Grantmakers in the Arts: Supporting a Creative America, 2022, https://www.giarts.org/blog/tasha-golden/absence-presence-arts-and-culture-help-us-redefine-health [Google Scholar]

- 42.Engh R, Martin B, Laramee Kidd S, et al. WE-Making: how arts & culture unite people to work toward community well-being. Easton, PA: Metris Arts Consulting, 2021, p. 33. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee D. How the arts generate social capital to foster intergroup social cohesion. The Journal of Arts Management, Law, and Society 2013; 43(1): 4–17. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Van de Vyver J, Abrams D. The arts as a catalyst for human prosociality and cooperation. Soc Psychol Personal Sci 2018; 9(6): 664–674, DOI: 10.1177/1948550617720275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lewis F, Sommer EK. Art and community capacity-building: A case study. In: Hersey L, Bobick B. (eds). The Handbook of Research on the Facilitation of Civic Engagement through Community Art IGI. Global Publishers, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Skoy E, Werremeyer A. Using photovoice to document living with mental illness on a college campus. Clinical Medicine Insights: Psychiatry 2019; 10: 117955731882109, DOI: 10.1177/1179557318821095. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Linz S, Jackson KJ, Atkins R. Using mindfulness-informed photovoice to explore stress and coping in women residing in public housing in a low-resourced community. Journal of Psychosocial Nursing and Mental Health Services 2021: 1–9. Advance online publication. DOI: 10.3928/02793695-20211214-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Straits KJE, deMaría J, Tafoya N. Place of strength: indigenous artists and Indigenous knowledge is prevention science. Am J Community Psychol 2019; 64(1–2): 96–106, DOI: 10.1002/ajcp.12376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Fountain S, Hale R, Spencer N, et al. A 10-Year systematic review of photovoice projects with youth in the United States. Health Promot Pract 2021; 22(6): 767–777, DOI: 10.1177/15248399211019978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Graziano KJ. Working with english language learners: preservice teachers and photovoice. International Journal of Multicultural Education 2011; 13(1). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Strack RW, Lovelace KA, Jordan TD, et al. Framing photovoice using a social-ecological logic model as a guide. Health Promot Pract 2010; 11(5): 629–636, DOI: 10.1177/1524839909355519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Cluley V. Using photovoice to include people with profound and multiple learning disabilities in inclusive research. Br J Learn Disabil 2017; 45(1): 39–46, DOI: 10.1111/bld.12174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Aknin LB, De Neve J-E, Dunn EW, et al. Mental health during the first year of the COVID-19 Pandemic: A review and recommendations for moving forward. Perspectives on Psychological Science 2022, DOI: 10.1177/17456916211029964. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.University of Florida Center for Arts in Medicine. ArtPlace America, Georgetown Lombardi Arts & Humanities program. Johns Hopkins University International Arts + Minds Lab . Creating healthy communities: arts+ public health in America, working group proceedings, 2019, pp. 1–67, https://arts.ufl.edu/site/assets/files/164507/dc_proceedings_jan20_2021.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chatterjee H, Polley MJ, Clayton G. Social prescribing: Community-based referral in public health. Perspectives in Public Health 2017; 138(1): 18–19, DOI: 10.1177/1757913917736661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Vidovic D, Reinhardt GY, Hammerton C. Can social prescribing foster individual and community well-being? A systematic review of the evidence. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021; 18(10): 5276, DOI: 10.3390/ijerph18105276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Bone J, Fancourt D, Fluharty M, et al. Associations between participation in community arts groups and aspects of wellbeing in older adults in the United States: a propensity score matching analysis. Aging & Mental Health 2022, doi: 10.1080/13607863.2022.2068129 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.World Health Organization [WHO] . A toolkit on how to implement social prescribing. Manila: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific, 2022, pp. 1–45, https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789290619765 [Google Scholar]

- 59.Golden TL, Lokuta AM, Mohanty A, et al. Social prescription in the US: A pilot evaluation of Mass Cultural Council’s “CultureRx”. Mass Cultural Council, 2023, 10, https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpubh.2022.1016136/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Kilgarriff-Foster A, O’Cathain A. Exploring the components and impact of social prescribing. J Public Ment Health 2015; 14(3): 127–134, DOI: 10.1108/JPMH-06-2014-0027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Stickley T, Hui A. Social prescribing through arts on prescription in a UK city: Referrers’ perspectives (part 2). Public Health 2012; 126(7): 580–586, DOI: 10.1016/j.puhe.2012.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Rose K, Daniel MH, Liu J. Creating change through arts, culture, and equitable development: a policy and practice primer. Oakland, CA: Policylink, 2017. Retrieved from https://www.policylink.org/sites/default/files/report_arts_culture_equitable-development.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 63.The U.S. Department of Arts and Culture [USDAC] . Art & well-being: toward a culture of health, 2018, pp. 1–75, https://www.americansforthearts.org/sites/default/files/ArtWellBeing_final_small.pdf [Google Scholar]

- 64.Sonke J, Sams K, Morgan-Daniel J, et al. Health communication and the arts in the United States: A scoping review. Am J Health Promot 2021; 35(1): 106–115, DOI: 10.1177/0890117120931710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Golden TL. Innovating health research methods, part II: Arts-based methods improve research data, trauma-responsiveness, and reciprocity. Fam Community Health 2022. b; 45(3): 150–159, DOI: 10.1097/FCH.0000000000000337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Perez G, Della Valle P, Paraghamian S, et al. A community-engaged research approach to improve mental health among Latina immigrants: ALMA photovoice. Health Promot Pract 2016; 17(3): 429–439, DOI: 10.1177/1524839915593500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav 1997; 24(3): 369–387, DOI: 10.1177/109019819702400309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Hatzenbuehler ML, Phelan JC, Link BG. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health 2013; 103(5): 813–821, DOI: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Gary FA. Stigma: barrier to mental health care among ethnic minorities. Issues Ment Health Nurs 2005; 26(10): 979–999, DOI: 10.1080/01612840500280638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services . Mental health: a Report of the surgeon general. Reports of the Surgeon General - Profiles in Science, 1999, https://profiles.nlm.nih.gov/spotlight/nn/catalog/nlm:nlmuid-101584932X120-doc [Google Scholar]

- 71.Chae D, Yip T, Martz C, et al. Vicarious Racism and Vigilance During the COVID-19 Pandemic: Mental Health Implications Among Asian and Black Americans. Public Health Reports 2021; 136(4), doi: 10.1177/00333549211018675 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Hankir A, Zaman R, Geers B, et al. The wounded healer film: A London college of communication event to challenge mental health stigma through the power of motion picture. Psychiatr Danub 2017; 29(3): 307–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Rolbiecki AJ, Washington KT, Bitsicas K. Digital storytelling as an intervention for bereaved family members. Omega 2021; 82(4): 570–586, DOI: 10.1177/0030222819825513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Voices of Youth . COVID-19: Your voices against stigma and discrimination. Voices of Youth, 2020, https://www.voicesofyouth.org/covid-19-your-voices-against-stigma-and-discrimination [Google Scholar]

- 75.Golden T, Hand J. Arts, culture and community mental health. Community Development Investment Review 2018; 13: 1. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Tebes JK, Matlin SL, Hunter B, et al. Porch Light program: final evaluation report. New Haven, CT: Yale School of Medicine, 2015, pp. 1–36. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Powell BJ, Beidas RS, Rubin RM, et al. Applying the policy ecology framework to Philadelphia's behavioral health transformation efforts. Adm Policy Ment Health 2016; 43(6): 909–926, DOI: 10.1007/s10488-016-0733-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.The Foundation for Art & Healing . Project UnLonely | The foundation for art & healing. National Initiative: Project UnLonely, 2022, https://www.artandhealing.org/ [Google Scholar]

- 79.Project: Music Heals Us . Music heals us, 2022, https://www.pmhu.org [Google Scholar]

- 80.EpiArts Lab . A national endowment for the arts research lab, 2022, https://arts.ufl.edu/academics/center-for-arts-in-medicine/researchandpublications/epiarts-lab/overview/ [Google Scholar]

- 81.Golden SD, McLeroy KR, Green LW, et al. Upending the social ecological model to guide health promotion efforts toward policy and environmental change. Health Educ Behav 2015; 42(1_suppl): 8S–14S, DOI: 10.1177/1090198115575098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Liebenberg L. Thinking critically about photovoice: achieving empowerment and social change. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 2018; 17: 160940691875763, DOI: 10.1177/1609406918757631. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Mass Cultural Council . CultureRx initiative. Mass Cultural Council, 2022. Retrieved June 13, 2022, from https://massculturalcouncil.org/communities/culturerx-initiative/ [Google Scholar]