Abstract

Background

The accommodation of eating disorder (ED) behaviours by carers is one of the maintaining processes described in the cognitive interpersonal model of anorexia nervosa. This systematic scoping review aimed to explore studies examining accommodating and enabling behaviour, including how it impacts upon the carer’s own mental health and the outcome of illness in their loved ones.

Methods and results

In this systematic scoping review, five databases (PubMed, Web of Science, MEDLINE, PsycInfo, CINAHL) were searched for studies measuring accommodating and enabling behaviour in carers of people with EDs. A total of 36 studies were included, of which 10 were randomised trials, 13 were longitudinal studies, nine were cross-sectional studies and four were qualitative studies. Carers of people with EDs were found to have high level of accommodating and enabling behaviour which reduced following treatment, although no single type of intervention was found to be superior to others. Higher accommodation in carers was associated with higher level of emotional distress, anxiety and fear. There was mixed evidence around whether accommodating and enabling behaviour in carers impacted the outcome of illness in their loved ones.

Conclusion

Accommodating and enabling behaviours are frequently seen in carers of people with AN, and carer-focused interventions are able to reduce these behaviours, although it is unclear if any intervention shows superiority. There may be nuances in the impact of these behaviours related to interactions within the support network and variations in the forms of co-morbidity in patients. More studies with a larger sample size and which include both mothers and fathers are required.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40337-024-01100-1.

Keywords: Anorexia nervosa, Eating disorders, Accommodation, Enabling behaviours, Systematic scoping review

Plain language summary

Eating disorders are complex mental health conditions which also significantly affect the physical health of patients and the carers who support these patients. In this systematic scoping review, the authors have examined the impact of eating disorders on carer's emotional reactions and behaviour towards the eating disorder symptoms, namely accommodating and enabling behaviour towards the illness. For this review the authors searched for published studies that examined accommodating behaviour in carers of people with any type of eating disorder, which includes studies such as randomized trials, longitudinal studies, cross-sectional studies and qualitative studies. Higher levels of accommodation in carers was associated with higher levels of their emotional distress, anxiety and fear. Accommodating and enabling behaviours reduced with treatment although no single type of intervention was more effective in this regard than others. There was mixed evidence for the impact of accommodating and enabling behaviour in carers on the outcome of eating disorders in the patients.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40337-024-01100-1.

Introduction

The outcomes of eating disorder (ED) treatment remain disappointing [59, 61]. For example, in cases of anorexia nervosa (AN), longitudinal studies have found approximately 30% remittance after inpatient care [11] and a third of people with AN or bulimia nervosa (BN) develop a protracted course (i.e., above nine years duration) [9]. Recent editorials suggest that this may be due to the lack of research resource assigned to this area [6], in part because these types of psychiatric disorders have been considered niche [19].

Eating disorders are often comorbid with a variety of other psychiatric conditions including anxiety, depression, obsessive–compulsive disorders, and autism spectrum disorders [59, 61]. Shared genetic and other risk factors between these conditions [23, 65] may predispose individuals to transdiagnostic temperamental features such as perfectionism, behavioural/cognitive rigidity and anxiety. These traits can impact on interpersonal family functioning in the context of an eating disorder. For example, some family members may “accommodate” anxiety in their loved ones by providing reassurance and/or modifying their behaviours to adapt to the compulsive routines and avoidance that form the safety behaviours that commonly develop, particularly in people with obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD) and autism spectrum conditions[1, 10]. In the short term these behaviours reduce distress for both the carer and their loved one, but over the long-term they may allow symptoms to persist [31].

Parent-focused interventions such as Supportive Parenting for Anxious Childhood Emotions (SPACE) targets these transdiagnostic interpersonal behaviours by placing the reduction of parental accommodation as central to the intervention. These interventions teach parents to step back from providing reassurance or participating in the safety behaviours of their child [30]. Reductions in these parental accommodating behaviours is associated with improved child outcomes for those with anxiety disorders, OCD [29, 57] and autism spectrum disorder [10]. These indirect interventions targeting parents are of particular benefit when the child is ambivalent about accepting help themselves. Moreover, the need for all parties to attend clinical centres for treatment is reduced.

Accommodating behaviours are also common in the families of people with EDs. The overt signs and symptoms of severe starvation in people with EDs elicit high levels of anxiety in close others and a common reaction is the urge to alleviate the problem and suffering by providing reassurance and even participating in the ED food and eating rituals or safety behaviours. For example, a carer may accommodate to their loved one’s wishes by cooking or buying food with low calories [14]. The cognitive interpersonal model of anorexia nervosa includes accommodation as one of the interpersonal maintaining factors to be considered as a target of treatment [48, 59–61]. The Accommodating and Enabling Scale for Eating Disorders (AESED) was developed to document these behaviours in food-related areas such as the type of food, when, with whom and how it is prepared and eaten, physical exercise and body checking behaviours [51].

Whilst the AESED has been employed in many research studies aiming to alter carer accommodating and enabling behaviours, thus far the literature and results of studies specifically investigating accommodating behaviour in carers of people with EDs have not been systematically synthesised. Here we refer to carer meaning anyone who provides recovery support. In this systematic scoping review, we collate and update the information included in previous systematic reviews that have examined family caregiving in people with EDs [2, 52, 68].

Methods and materials

This systematic scoping review was carried out following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) extension for scoping review guidelines [62] (Table S1). A systematic scoping review was deemed the appropriate methodology given the broad scope of the study aims of mapping the available evidence across study designs pertaining to accommodating and enabling behaviour in carers of people with AN [40]. A protocol and search strategy was prospectively registered on 15th January 2024 with the International prospective register of systematic reviews (Registration number: CRD42023395389).

Literature search

Five databases (PubMed, WoS, Ovid MEDLINE, APA PsycInfo, CINAHL) were searched from database inception until the 13th February 2024. Searches included the following keywords, using the Boolean operators AND and OR: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, ARFID or eating disord*, in combination with carer*, parent* maternal, paternal, cargiv*, famil*, sibling* or partner*, in combination with accomodat* or enabling. Searches were supplemented by internet searches, hand searches through reference lists of eligible and potentially relevant articles and reviews, and through Google Scholar citation tracking. See Table S2 for a full overview of search terms per database.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies published in the English language of any study design that examined the experiences of parents, carers and siblings who care for an individual with any eating disorder, were included in this review. Participants of any age were included. Publications were included if they reported original quantitative or qualitative data at any time-point. There were no restrictions on publication date.

Studies were excluded if they: (i) were review articles, perspective papers, letters (without data), conference papers, book chapters, case reports/series, academic theses; (ii) used animal samples; (iii) did not include data measured in carers of a person with an eating disorder; (iv) did not report data relating to accommodation and enabling behaviours.

Source selection

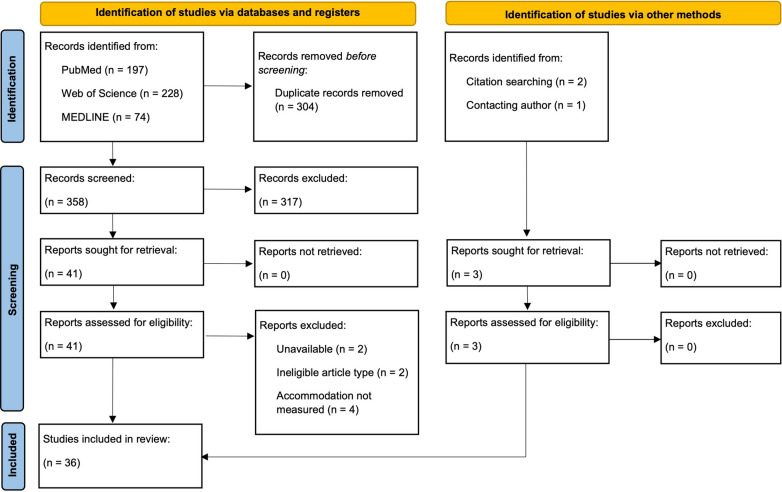

The search process was conducted independently by two reviewers (A.K. and J.L.K.). The titles and abstracts of articles were first imported into EndNote, where duplicate records were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened according to the eligibility criteria and articles deemed highly unlikely to be relevant to the study were discarded. Following this, two reviewers (A.K. and J.L.K.) reviewed the full texts of articles to examine their suitability for the systematic review, and discrepancies were resolved with a third reviewer (J.T.). See Fig. 1 for an overview of the study selection process.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram (from Page et al., 2021)

Data extraction

The main investigator (A.K.) extracted data from all included studies into an electronic database (Microsoft Excel spreadsheet), and 50% of the data was checked by another reviewer (J.L.K.). The data extracted included the following: publication identifiers (i.e., title, authors, year, journal, abstract); country of origin; study design; study methodology; sample characteristics (i.e., mean age, sample size, sex, per patient and carer group); clinical characteristics (i.e., diagnosis, diagnostic tool, illness duration, type of treatment); accommodation-related outcomes in carers and patients. Authors were contacted where data was unobtainable from the manuscript.

Quality assessment

The methodological quality of studies was assessed using the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Critical Appraisal Tools for analytical cross-sectional studies, randomised controlled trials and qualitative research [24]. There was no suitable JBI critical appraisal tool for the longitudinal studies, hence we used the cohort study tool with slight modification. See Tables S3-S6 for a full appraisal of study quality.

Synthesis of results

The results of eligible studies were narratively synthesised according to study design themes (i.e., randomised controlled trial, longitudinal study, cross-sectional study, qualitative study). Findings were synthesised according to categories of intervention, or those with similar study aims, methods or analyses. Results are reported according to p-values or effect sizes, depending on what was reported in the manuscripts.

Results

Search results

Following de-duplication, the titles and abstracts of 358 studies were screened, resulting in 41 for full-text appraisal (Fig. 1). At this stage, eight studies were excluded: two were unavailable, two were an ineligible article type (one case study, one conference abstract), and in four, accommodation was not explicitly measured. Three additional studies were identified by citation searching and from correspondence with colleagues. Therefore, a total of 36 studies were included in this systematic scoping review.

Study characteristics

This review included data from 32 quantitative studies and four qualitative studies published between 2009 and 2023. Included studies were published in the United Kingdom (n = 11), the United States of America (n = 6), Canada (n = 6), Italy (n = 4), Spain (n = 4), Australia (n = 2), Germany (n = 2) and Iceland (n = 1). Of the quantitative studies, there were various study designs, including 10 randomised trials, 13 longitudinal studies and nine cross-sectional studies. The study characteristics and their outcomes are summarised according to study design in Tables 1, 2, 3 and 4.

Measurement tools utilised across studies

The vast majority of the quantitative studies utilised the Accommodation and Enabling Scale for Eating Disorders (AESED; [51]) to measure accommodation. The AESED is a 33-item self-report measure that assesses the general tendency to engage in accommodation and enabling behaviours among parents and carers with EDs. The AESED has a five-factor structure (i.e., 1) Avoidance and Modifying Routine, (2) Reassurance Seeking, (3) Meal Ritual, (4) Control of Family and (5) Turning a Blind Eye), which have demonstrated adequate internal consistency, convergent validity, and sensitivity to change after family interventions. Higher scores on AESED subscales and total score indicate greater levels of family member accommodation and enabling behaviour.

Other tools to measure accommodation that were used in studies included the Family Coping Questionnaire for Eating Disorders (FCQ-ED; [12]) in one study [39], and the Family Accommodation Scale—Anxiety (FASA; [32] in one study [53].

Participant characteristics

A total of 1,839 people with EDs were included in the studies (N reported in 30 studies), who were mostly female (93%). The patient groups included across articles included AN (n = 1,517), EDNOS (n = 111), ARFID (n = 58), BN (n = 59), BED (n = 17) and OSFED (n = 2). The age of the people with EDs was reported by 22 studies and when pooled had a mean ± standard deviation (M ± SD) of 19.3 ± 7.1 years.

A total of 3,029 carers participated in the studies. The vast majority of carers were parents of people with EDs (n = 2,693), but also partners (n = 127), siblings (n = 16), grandparents (n = 5) and friends (n = 7). The pooled age of the carers was 49.2 ± 7.1 years, reported by 15 studies. Only 17 studies reported whether carers were living with the person with an ED, and amongst these studies 79% were cohabiting.

Study quality

The methodological quality of the articles was assessed with the JBI Critical Appraisal Tool. The studies were divided into four categories based on their design: randomised controlled studies (n = 10), longitudinal (n = 13), cross-sectional (n = 9) and qualitative studies (n = 4) (Tables S3-S6).

The quality assessment for randomised trials indicated that though true randomisation was used for all the studies, the nature of the interventions were such that it was impossible to blind the participants. The outcome assessors could have been blinded, which was done in six studies but not in three other studies. Most studies reported numbers completing follow-up or the reasons for attrition, and all studies measured outcomes in a reliable way, used appropriate statistical analysis and trial methodology. Overall the studies had low-to-moderate risk of bias; there were less than 50% negative or unclear responses on the quality assessment tool. The longitudinal studies overall had low risk of bias, although several studies didn’t identify and/or control for confounding factors (n = 7), or address incomplete follow-up (n = 5). Amongst the cross-sectional studies, the clear criteria to include in the sample were not included in three studies and the confounding factors were clearly identified and dealt with only in four studies, although outcomes were measured in a reliable way and appropriate statistical analysis was used in all studies. The methodology, representation of the participants’ voices and conclusions drawn were appropriate in all qualitative studies. However, there was lack of clarity around congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology in two qualitative studies. The influence of the researcher on the research, and vice- versa, was not addressed in all the four studies.

Study results

Randomised trials

The data from the 10 included randomised trials are tabulated in Table 1. The ten studies included information from people with AN (n = 707), BN (n = 38), BED (n = 6), ARFID (n = 4) and EDNOS (n = 21). A total of 1,193 carers participated across the trials. Four of these randomised trials used the intervention “Experienced Carers Helping Others” (ECHO) with three using treatment-as-usual (TAU) as comparison arm [21, 22, 33], and one compared standard ECHO to ECHO with coaching [16]. The other six studies used a diverse range of psychoeducation-based interventions [7, 18, 36, 44, 45, 50].

Table 1.

Characteristics and results of randomised trials

|

Study reference Country |

Patients | Carers | Outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Arm (format) |

Patient diagnosis (N) or (%) |

Gender (N/%) and age (M ± SD) or (Med, range) |

Type of carers (N) |

Living with sufferer N (%) |

Age M ± SD |

AESED (change) M ± SD |

Narrative results | |

|

[7] Canada |

Web-based ED psych-ed (8 weeks) |

AN-R (10) AN-BP (4) AN-unknown (3) BN (8) BED (3) ARFID (1) |

NR |

Parent (23) Partner (0) Friend (0) |

NR | 53.4 ± 6.7 |

- Baseline to post-treatment: (-6.97 ± 16.75) - Baseline to 3-months: (-9.03 ± 21.07) |

- No difference between arms in AESED reduction at post-treatment (ES = 0.02) or 3-months (ES = 0.05) |

| Workshop ED psych-ed (2 days) |

AN-R (8) AN-BP (6) AN-unknown (6) BN (8) BED (3) ARFID (3) |

NR |

Parent (24) Partner (2) Friend (1) |

NR | 48.9 ± 11.5 |

- Baseline to post-treatment: (-6.64 ± 15.01) - Baseline to 3-months: (-9.77 ± 19.51) |

||

|

[16] UK |

ECHO (6 weeks) |

AN (63) BN (7) EDNOS (6) |

Female (76) Male (4) 20.8 ± 6.9 |

Mother (72) Father (3) Spouse (3) |

63 (81%) | 50.5 ± 6.9 |

- Baseline: 47.4 ± 23.7 - Post-intervention: 40.7 ± 25.4 |

- AESED significantly reduced in both arms - No added benefit of telephone coaching in ECHOc group - AESED change scores were correlated with changes in carers’ HADS (r = 0.5, p < 0.001) - AESED change scores were correlated with GEDF scores (r = -0.4; p < 0.001) - ECHO most effective for people with high levels of AESED - Proportion of DVDs watched (adherence) moderated change in AESED |

|

ECHOc (6 weeks) |

AN (59) BN (5) EDNOS (2) |

Female (70) Male (3) 20.9 ± 6.8 |

Mother (58) Father (6) Spouse (5) Child (2) Other (2) |

54 (77%) | 48.7 ± 9.1 |

- Baseline: 45.2 ± 22.8 - Post-intervention: 40.4 ± 21.7 |

||

|

[18] UK |

OAO web-based intervention (4 months) |

AN-R (18) AN-BP (8) EDNOS (7) |

21.1 ± 7.0 |

Mother (23) Father (4) Husband/male partner (4) Other (2) |

26 (78.8%) | 47.3 ± 8.7 | NR | - No difference between arms in AESED reduction at post-treatment (p = 0.179) or 6mth follow-up (p = 0.925) |

|

Charity support (4 months) |

AN-R (20) AN-BP (3) EDNOS (6) Unknown (1) |

19.7 ± 5.2 |

Mother (27) Father (1) Husband/male partner (1) Other (1) |

23 (76.7%) | 49.1 ± 6.2 | NR | ||

|

[21] UK |

ECHO + TAU | AN (86) |

Female (83) 23.16 (12.5–62.7) |

Mother (144) Father (81) Partner (28) Sibling (7) Friend (5) Other relatives (3) |

57 (66%) | Adult (NR) |

- Baseline: 47.68 ± 22.14 - Post-treatment: 40.73 ± 21.32 - 6-months: 35.48 ± 23.08 - 12-months: 33.10 ± 22.59 |

- No significant difference between arms at post-treatment (ES = -0.06), 6-months (ES = -0.15) or 12-months (ES = -0.01) (all p = n.s.) |

| TAU | AN (92) |

Female (86) 24.3 (13.7–57.3) |

65 (71%) | Adult (NR) |

- Baseline: 47.28 ± 24.92 - Post-treatment: 43.93 ± 24.77 - 6-months: 41.49 ± 23.81 - 12-months: 37.67 ± 24.74 |

|||

|

[22] UK |

ECHOg + TAU |

AN (38) Atypical AN (12) |

Female (44) Male (6) 16.7 ± 2.4 |

Mother (51) Father (27) |

Most | 49.1 ± 5.7 |

- Baseline: 45.4 ± 21.1 - 6-months: 39.2 ± 18.4 |

- Slightly greater but non-significant AESED reduction at 6 months in combined ECHO groups compared to TAU (ES = 0.19) |

| ECHO + TAU |

AN (33) Atypical AN (16) |

Female (45) Male (4) 17.2 ± 2.0 |

Mother (52) Father (20) |

Most | 47.7 ± 8.9 |

- Baseline: 54.6 ± 21.6 - 6-months: 45.8 ± 24.6 |

||

| TAU |

AN (41) Atypical AN (9) |

Female (48) Male (2) 16.9 ± 2.1 |

Mother (52) Father (24) |

Most | 47.8 ± 7.7 |

- Baseline: 49.3 ± 22.3 - 6-months: 45.6 ± 24.0 |

||

|

[33] UK |

ECHO + TAU | AN (61) |

NR 27 ± 9 (across groups) |

Mother (144) Father (81) Partner (28) Sibling (7) Friend (5) Other relatives (3) |

57 (66%) | Adult (NR) | NR |

- Update of [21] - AESED nominally lower in ECHO at 24-months (ES = -0.24; p = 0.120) |

| TAU | AN (58) |

NR 27 ± 9 (across groups) |

65 (71%) | Adult (NR) | NR | |||

|

[36] Australia |

Intervention (two 2.5 h sessions over 2 weeks) |

AN (8) Atypical AN (2) BN (2) No formal diagnosis (1) |

NR |

Mother (7) Father (4) Partner (4) Friend (1) Grandparent (1) Other (1) |

NR | 47.8 ± 11.8 |

- Baseline: 71.1 ± 22.9 - Post-intervention: 68.7 ± 20.4 - 1-month FU: 63.6 ± 24.7 |

- AESED nominally higher in intervention group than waitlist at post-intervention (ES = -0.11; p = n.s.) but lower at follow-up (ES = 0.20; p = n.s.) |

| Waitlist |

AN (5) BN (3) No formal diagnosis (2) |

NR |

Mother (9) Father (4) Partner (1) Sibling (1) |

NR | 52.4 ± 8.8 |

- Baseline: 83.2 ± 36.6 - Post-intervention: 75.9 ± 31.3 - 1-month FU: 79.0 ± 38.7 |

||

|

[44] Germany |

Video intervention |

AN (72.7%) BN (19.8%) OSFED (7.5%) |

Female (94.9%) 19.7 ± 5.9 |

Parent (136) Spouse (10) Sibling (1) |

85.3% | 48.7 ± 7.7 |

- Baseline: 44.2 ± 22.3 - 3-months FU: 33.5 ± 20.5 |

- Medium-sized reduction in AESED in both video group (ES = 0.48) and control (ES = 0.47) - AESED smaller in control at follow-up (ES = 0.23) but also at baseline (ES = 0.31) - Non-significant Group x Time interaction (p = 0.396) |

| TAU |

AN (61.6%) BN (26.3%) OSFED (12.1%) |

Female (97.7%) 22.1 ± 6.8 |

Parent (117) Spouse (20) Other (1) |

78.2% | 48.0 ± 8.4 |

- Baseline: 37.8 ± 18.6 - 3-months FU: 29.0 ± 19.0 |

||

|

[45] Spain |

Collaborative Care Skills workshops (six 2-h sessions over 3 months) |

AN (15) BN (4) EDNOS (3) Unspecified (1) |

Female (20) Male (3) 19.2 ± 5.8 |

Mothers (22) Fathers (16) Siblings (1) Partners (1) |

100% | 48.5 ± 7.5 |

- Baseline: 36.7 ± 21.1 - Post-intervention: 31.0 ± 16.3 - 3-months FU: 28.5 ± 13.9 |

- AESED total scores decreased from baseline to followup in the carer skills group (hp2 = 0.21) but not from baseline to post intervention - AESED total showed a significant decrease from baseline to post-intervention and follow-up (hp2 = 0.50) - There were no differences between groups at any time-point |

| Psychoeducational workshops (six 2-h sessions over 3 months) |

AN (13) BN (1) |

Female (14) 21.4 ± 8.2 |

Mothers (16) Fathers (5) Siblings (1) Partners (2) |

100% | 48.5 ± 8.9 |

- Baseline: 37.8 ± 19.1 - Post-intervention: 25.3 ± 16.3 - 3-months FU: 22.9 ± 14.6 |

||

|

[50] Spain |

Skill-based workshop (six 2-h workshops over 3 months) |

AN (52.4%) BN (14.3%) EDNOS (33.3%) |

Female (90.5%) Male (9.5%) 19.1 ± 3.6 |

Female caregiver (27) | 20 (74.1%) | 53.7 ± 6.5 |

- Baseline: 41.17 ± 21.77 - 3-months: 36.74 ± 19.34 - 3-month FU: 32.00 ± 17.34 |

- Both groups had a decrease in AESED over time (h2 = 0.08, p – 0.026), with no group showing superiority |

| Psych-ed workshop (six 2-h workshops over 3 months) |

AN (46.2%) BN (23.1%) EDNOS (30.8%) |

Female (90.5%) Male (9.5%) 21.2 ± 4.9 |

Female caregiver (25) Male caregiver (1) |

23 (87%) | 55.3 ± 7.9 |

- Baseline: 30.62 ± 17.13 - 3-months: 30.81 ± 20.87 - 3-month FU: 25.86 ± 21.42 |

||

h2 = eta squared; hp2 = partial eta squared; AESED = Accommodation and Enabling Scale; AN = anorexia nervosa; AN-BP = anorexia nervosa binge-purging subtype; AN-R = anorexia nervosa restricting subtype; ARFID = avoidant restrictive food intake disorder; BED = binge eating disorder; BN = bulimia nervosa; ECHO = Experienced Carers Helping Others; ECHOg = ECHO guided; ES = effect size; EDNOS = eating disorder not otherwise specified; M = mean; N = number; OAO = Overcoming Anorexia Online; SD = standard deviation; TAU = treatment as usual

Of the four ECHO trials, all found nominal reductions in AESED scores after ECHO, although this was not significantly different from TAU arms. In a study of mainly adult inpatients, there was no significant difference between arms at post-treatment, 6-months or 12-months [21]. A later publication based on follow-up data at 24-months from the same trial from Magill et al. [33] found nominally lower scores in the ECHO group compared to TAU. In an outpatient study of adolescents [22], there were nominally greater reductions at 6-months in the combined ECHO groups (ECHO and ECHO with guidance) in comparison to TAU. In the study comparing 6-weeks of ECHO and ECHO with telephone coaching, reductions in AESED scores were found in both groups, with no added benefit of telephone coaching [16]. This study found ECHO was most effective in people with high AESED scores, and improvements in AESED was moderated by adherence to the intervention. Additionally, changes in AESED scores were related to improvements in carers’ depression scores, and global ED functioning in their loved ones.

Three studies examined skills-based workshops for carers [36, 45, 50]. In a study comparing six 2-h collaborative care skills workshops to psychoeducational workshops over three months [45], there were reductions in AESED scores from baseline to follow-up in both groups, and reductions from baseline to post-intervention in the psychoeducational workshop group. There were no differences in AESED scores between groups at any time-point. In another comparison study of six 2-h skills-based workshops and psychoeducational workshops [50] both arms showed reduction in AESED scores at three-months and at a three-month follow-up, with no arm having superior reductions. Finally, in a study comparing two 2.5 h psychoeducational/communication skills-based workshops with waitlist participants, there was no greater reduction in AESED scores in either arm despite both showing a nominal reduction [36].

Two studies investigated web-based interventions [7, 18]. One study compared an eight-week web-based psychoeducational intervention for carers with a two-day psychoeducational workshop [7]. Both interventions were based on the same psychoeducational materials, with the web-based intervention occurring at the user’s own pace over eight weeks, and the workshops occurring over two 7-h workshops one month apart. From baseline to post-intervention, and from baseline to three-months, there was a reduction in AESED scores in both groups, which were not significantly different from one another. Another study compared a four-month “overcoming anorexia online” web-based intervention to four months of charity support [18], finding no difference between arms in AESED scores after treatment or at a six-month follow-up.

Additionally, one study compared a video-based intervention for carers (based on the interpersonal maintenance model) to TAU [44]. Both arms again reported a reduction in AESED scores at three-months, with no difference between arms.

Longitudinal studies

Study characteristics and findings of the thirteen longitudinal studies are included in Table 2. These studies collectively included information from patients with AN (n = 396), BN (n = 18), BED (n = 11) and EDNOS (n = 42), OSFED (n = 2) and ARFID (n = 54), and 721 carers. There was significant heterogeneity across the studies in terms of the type of intervention between the baseline and follow-up time-points. Four studies broadly included hospital programmes for young people that actively involved both the patients and their carers [5, 8, 20, 63], one of which was a study examining transitions to home treatment for young people with AN [20]. Seven studies included carer-focused interventions [15, 34, 38, 42, 43, 47, 53]. One study examined the use of a couples-based intervention for people with BED [66]. Finally, one other study examined pre and post outcomes in parents of children with AN who were hospitalized for medical stabilization [58].

Table 2.

Characteristics and results of longitudinal studies

|

Study reference Country |

Patients | Carers | Measures | Treatment details | Outcomes | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Patient diagnosis (N) or (%) |

Gender (N) and age (M ± SD) | Type of carers (N) |

Living with sufferer N (%) |

Age M ± SD |

Measures in carers Measures in patients |

Type of intervention | Treatment period |

Accommodation (change) M ± SD |

Narrative results | |

|

[5] USA |

AN (15) BN (1) OSFED (2) |

Female (12) Male (6) 22.2 ± 5.3 |

Mothers (29) Fathers (6) Spouses (5) |

30 (75%) | 50.4 ± 7.6 |

AESED; PROMIS-A; FAD EDE-Q |

1. CBT-ED individual and group therapy formats for approximately five hours each day for patients 2. Weekly one-hour family therapy sessions centred around identifying and reducing accommodation 3. Accommodation-focused bi-weekly two-hour educational workshops for caregivers 4. Family “passes” from the residential programme where carers were instructed and given goals for reducing accommodation |

52.3 ± 23.3 days | NR |

Baseline: - Higher AESED related to higher PROMIS-A scores - Higher AESED “turning the blind eye” related to higher FAD roles and behavioural control Follow-up: - Higher AESED significantly predicted higher EDE-Q global scores in patients at discharge, whilst controlling for baseline EDE-Q, FAD, PROIMIS-A and length of stay |

|

[8] Canada |

AN (26) |

Female (25) Male (1) 18.2 ± 2.1 |

Mothers (23) Fathers (16) |

24 (92%) | 50.6 ± 6.8 |

AESED; PvA EDE-Q |

FBT for transition aged youth, involving 25 sessions over the course of three phases, involving patients and their caregivers | NR |

AESED Baseline: 46.3 ± 3.6 Post-treatment: 37.8 ± 3.1 3-mth FU: 45.2 ± 3.2 |

- Significant reduction in AESED from baseline to post-treatment - This was not sustained at a 3-month follow-up - Changes in caregiver AESED scores were not associated with EDE-Q scores or weight restoration in patients |

|

[15] Iceland |

AN (25) BN (4) EDNOS (3) |

NR 16.2 ± NR |

Mothers (26) Fathers (4) Others (2) |

NR | 45.4 ± NR | AESED; ECI; PedsQL; RSC; ICE- PFSQ; ICE-FIBQ |

Therapeutic Conversation Intervention based on four theoretical frameworks: Caregivers attended 3 weekly group sessions, with 2 weekly caregiver interviews. One month later, attended 3 monthly booster group sessions |

4 months |

AESED Baseline: 36.1 ± 16.5 Post intervention: 35.1 ± 14.9 4-mth FU: 27.7 ± 12.3 |

- Significant reduction in AESED from baseline to follow-up but not from baseline to post-intervention |

|

[20] Germany |

AN (22) |

Female (22) 15.1 ± 1.2 |

Mothers (21) Fathers (1) |

22 (100%) | NR |

AESED; EDSIS; CASK EDE; MRAOS; MINI; BDI-II; Kidscreen-27; ZUF-8 |

Home treatment: Patients and families visited 3–4 × a week by MDT in months 1 and 2, which reduced to 1–2 × a week in months 3 and 4 | 4 months |

AESED Baseline: 39.3 ± 17.3 Post-treatment: 28.1 ± 15.5 1-year FU: 24.8 ± 18.8 |

- Significant reduction in AESED from baseline to follow-up |

|

[34] USA |

AN (10) |

Female (9) Male (1) 15.9 ± 1.4 |

Parents (10) | NR | NR |

AESED; ABOS; CEQ; DASS; IES-R; PvA; semi-structured interview EDE-Q; EDFLIX; Dflex |

Open Science Online Grocery: a virtual online grocery store, used as an educational tool | NR |

AESED Baseline: 40.8 ± 28.6 4-wk FU: 31.0 ± 15.4 |

- Reduction in AESED scores from baseline to four weeks follow-up post discharge |

|

[38] Italy/UK/Spain |

AN (112) EDNOS (37) |

Female (137) Male (12) 16.9 ± 2.1 |

Mothers (139) Fathers (7) Grandmother (1) Sibling (2) |

NR | 48.1 ± 6.0 |

AESED; DASS-21; FQ; CASK; OSSS-3 SEED; DASS-21; CIA |

Participants were randomized to TAU, TAU + ECHO or TAU + ECHO supplemented by telephone guidance (ECHOc). Data from ECHO and ECHOc at baseline and 6- and 12-mth FU used in this study | NR | NR |

- In a network analysis using baseline data, carer’s accommodation emerged as a node with the highest bridge function (had strong and positive connection to other nodes) - Carer’s accommodation at baseline positively predicted patient’s BMI at 1-year |

|

[42] Canada |

EDs (NR) |

NR 20.8 ± 6.7 |

Mothers (43) Fathers (15) Relative/partner (16) |

NR | NR | AESED; PvA; CTS; semi-structured interviews | Two-day Emotion-Focused Family Therapy workshop for carers | NR |

AESED Baseline: 56.1 ± 23.7 Post-treatment: NR 6-mth FU: 41.7 ± 22.3 |

- Significant decrease in AESED scores from baseline to a follow-up at 6-months (d = 0.63) |

|

[43] Australia |

AN (36) BN (13) AN/BN (3) EDNOS (2) Unspecified (2) |

Female (55) Male (1) 19.1 ± 4.1 |

Mothers (50) Fathers (24) Partners (2) Sisters (1) |

61 (79%) | 48.8 ± 7.1 | AESED; Brief COPE; FQ; GHQ-12; EDSIS; Conflict subscale of FES | Collaborative Care Skill Training Workshop, six 2-h Collaborative Care Skill Training workshops held on a weekly basis for carers | 6 weeks |

AESED Baseline: 52.4 ± 19.8 Post-treatment: 48.2 ± 22.4 6-8wk FU: 42.6 ± 25.3 |

- Significant decrease in AESED scores from baseline to post-intervention (hp2 = 0.08) and to follow-up (hp2 = 0.20) - Changes found in all subscales other than “meal rituals” and “control of family” |

|

[47] UK |

AN (54) |

Female (51) 16.7 ± 2.0 |

Mothers (54) Fathers/step-fathers (54) |

NR | 49.9 ± 5.6 |

AESED; CASK SEED |

Participants were randomized to TAU, TAU + ECHO or TAU + ECHO supplemented by telephone guidance (ECHOc). Data from all groups at baseline and 12-mth FU used in this study. This subsample received either TAU (31.5%) or TAU with ECHO (68.5%) with (n = 21) or without (n = 16) carer coaching | 6 months | NR |

- No difference in baseline AESED between groups - Parental AESED scores not related to offspring’s initial AN symptoms - Over time, the offspring’s ED symptoms over 12 months followed a quadratic curve (i.e., improved and then worsened) - Patient’s AN symptoms decreased in a quadratic manner when both parents had low AESED scores, but increased in a quadratic manner when both parents had high AESED scores - The best outcomes for patients were reported when both parents were not accommodating |

|

[53] USA |

ARFID (15) |

Female (2) Male (13) 9.1 ± 2.6 |

15 | NR | NR |

FASA; CSQ-8 ADIS-C/P; CSQ-8; NIAS |

SPACE-ARFID: 12 weekly 60-min sessions conducted with parents, aiming to improve the child’s food-related flexibility by reducing accommodation | 12 weeks |

FASA Baseline: 17.7 ± 6.7 Post-treatment: 9.9 ± 6.7 |

- FASA total scores and subscales significantly reduced after treatment |

|

[58] USA |

AN (37) |

NR 14.8 ± 2.4 |

Mothers (34) Fathers (13) |

NR | 43.6 ± 6.2 | AESED; IES-R; FQ; Dflex; AAQ-II; DASS-21; ABOS | No treatment – children were hospitalized for medical stabilization | NR | N/A |

- At baseline, maternal, but not paternal, PTSS were correlated with AESED scores - AESED was not reported at other time-points |

|

[63] USA |

AN-R (48) AN-BP (11) ARFID (39) |

Female (74) Male (24) 13.7 ± 2.3 |

Mothers (77) Fathers (16) Grandparent (3) Stepparent (2) |

98 (100%) | NR |

AESED; EDSIS FOFM; NIAS; ChEAT |

Partial hospitalization programme for EDs, which included family involvement, a weekly multi-family group and a weekly parent support group | 25.2 ± 12.7 days |

AESED Baseline: 38.6 ± 21.9 Discharge: 26.2 ± 15.8 |

- Reduction in AESED from baseline to discharge - At baseline, AESED scores were higher in parents of AN patients compared to ARFID - No significant differences between AN and ARFID at discharge - AESED positively associated with EDSIS Nutrition scores, which was larger for ARFID than AN - AESED associated with NIAS Picky Eating in ARFID - AESED associated with ChEAT Dieting and ChEAT total scores in AN - No significant association between AESED change and treatment outcomes |

|

[66] USA |

BED (11) |

Female (8) Male (3) 48.5 ± 12.0 |

Male partners (8) Female partners (3) |

11 (100%) | 51.2 ± 14.4 |

AESED; emotional arousal BES; emotional arousal |

UNITE: a 22-session manualized structured couple-based intervention employing a CBT approach | NR | NR |

- Pretreatment AESED scores unrelated to patient’s pre- or post-treatment binge eating severity - AESED was not related to the level of emotional arousal in patients and partners during conversation - Before treatment, in highly accommodating partners, emotional arousal of partners was more reactive to emotional arousal of patients. This was not observed after treatment |

Abbreviations: AAQ-II = Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-2; ABOS = Anorectic Behavior Observation Scale; ADIS-C/P = Anxiety Disorders Interview Schedule for DSM-IV for Children – Child and Parent Version; AESED = Accommodation and Enabling Scale; AN = anorexia nervosa; AN-BP = anorexia nervosa binge-purging subtype; AN-R = anorexia nervosa restricting subtype; ARFID = avoidant restrictive food intake disorder; BDI-II = Beck Depression Inventory-II; BED = binge eating disorder; BES = Binge Eating Scale; BN = bulimia nervosa; Brief COPE = Coping Orientation to Problems Experienced Inventory-abbreviated; CASK = Caregiver Skills scale; CBT = Cognitive Behavioural Therapy; CEQ = Credibility and Expectancy Questionnaire; ChEAT = Children’s Eating Attitudes Test; CSQ-8 = Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8; CTS = Caregiver Traps Scale; DASS = Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale; Dflex = Detail and Flexibility Questionnaire; ECHO = Experienced Carers Helping Others; ECI = Experience of Caregiving Inventory; ED = eating disorder; EDE-Q = Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire; EDFLIX = Eating Disorder Flexibility Index; EDNOS = eating disorder not otherwise specified; EDSIS = Eating Disorders Symptom Impact Scale; FAD = Family Assessment Device; FASA = Family Accommodation Scale – Anxiety; FES = Family Environment Scale; FOFM = Fear of Food Measure; FQ = Family Questionnaire; GHQ-12 = General Health Questionnaire-12; ICE-FIBQ = Iceland Family Illness Beliefs Questionnaire; ICE-PFSQ = Iceland Family Perceived Support Questionnaire; IES-R = Impact of Events Scale – Revised; M = mean; MINI = Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview; MRAOS = Morgan-Russell Average Outcome Scale; N = number; NIAS = Nine Item ARFID Screen; NR = not reported; OSFED = other specified feeding and eating disorder; OSSS-3 = Oslo Social Support Scale; PedsQL = Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory; PROMIS-A = Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System-Anxiety short form 8a; PvA = Parents Versus Anorexia Scale; RSC = Revised Scale of Caregiving self-efficacy; SD = standard deviation; SEED = Short Evaluation of Eating Disorders; TAU = Treatment As Usual; ZUF-8 = Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8 (German Version)

Studies of hospital programmes involving patients and carers

In three studies, changes were found in AESED scores of carers from baseline to post-intervention time-points [8, 20, 63]; this was not reported in one study [5]. In a study investigating home-based treatment for young people with AN [20] and a study investigating a partial hospitalization programme for young people with AN and ARFID including family involvement [63], changes in AESED scores were found from pre- to post-treatment. In another study investigating 25-session Family-Based Therapy for transition-aged youth, a reduction in AESED scores were observed from baseline to post-treatment, although this was not sustained at a 3-month follow-up [8].

Three studies examined the predictive value of AESED scores with differing findings [5, 8, 63]. In one study, higher AESED scores in parents predicted higher EDE-Q global scores in patients at discharge after participation in a comprehensive intervention using CBT-ED for patients and components aimed at reducing accommodation in carers [5]. However, in another study changes in AESED scores from pre- to post- intervention were not associated with changes in EDE-Q scores in patients or weight restoration [8]. Additionally, in the study by Wagner et al. [63], there was no association between changes in AESED scores of carers and treatment outcomes of patients.

Studies examining carer-focused interventions

One study utilizing a group-based “Therapeutic Conversation Intervention” rooted in four theoretical frameworks did not find reductions in AESED scores from baseline to post-intervention, although significant reductions were found from baseline to a 4-month follow-up time-point [15]. In another study examining the effects of a two-day emotion-focused family therapy workshop for carers of people with different EDs, significant decreases in AESED scores were found from baseline to a 6-month follow-up [42]. Another study utilizing weekly 2-h workshops aimed at developing collaborative care skills found significant reductions in total AESED scores from baseline to post-treatment and follow-up [43]. Reductions were found in all subscales other than two (“Meal rituals” and “Control of family”). One study found a reduction in AESED scores from baseline to a four-week follow-up in carers using an online virtual grocery store, which was utilized as an educational tool [34]. Finally, one study examining a 12-week parental intervention aiming to improve the food-related flexibility of children with ARFID via reducing accommodation in parents (SPACE-ARFID), reductions in FASA scores were observed from baseline to post-treatment [53].

Two studies [38, 47] performed secondary analyses from data from a RCT reported in the previous section [22]. One study performed a network analysis, yielding the paradoxical finding that baseline AESED scores in carers positively predicted the BMI of patients at a 1-year follow-up [38]. The other study used polynomial hierarchical linear models to examine the relationship between baseline AESED scores in parents and changes in AN symptoms in their offspring [47]. This study found that patient’s symptoms followed a quadratic curve, whereby they initially improved and then worsened. This interacted with the AESED scores of parents; where both parents had low AESED scores, the patient’s AN symptoms decreased in a quadratic manner, whereas where both parents had high AESED scores, their symptoms increased in a quadratic manner. Overall, the best outcomes were reported for patients whose parents were both low in accommodation, worse for patients whose parents were both high in accommodation, and moderate for patients where one of the parents was highly accommodating and the other was not.

Other longitudinal studies

A study by Weber et al. [66] examined a 22-session CBT-based couples intervention for people with BED, finding that AESED scores in partners were unrelated to binge eating severity in patients both before and after the intervention. The authors measured the emotional arousal in patients and their partners during conversation, finding that although AESED scores were overall unrelated to emotional arousal, partners who were highly accommodating were more reactive to emotional arousal of their patients at baseline. However after treatment, this association was not found.

One study aimed to investigate symptoms of post-traumatic stress in parents of children with AN hospitalized for medical stabilization [58]. This study found that at baseline, maternal but not paternal post-traumatic stress symptoms were positively associated with AESED scores.

Cross-sectional studies

The study characteristics and data from the nine included cross-sectional studies can be found in Table 3. These studies included information from people with AN (n = 385), BN (n = 3) and EDNOS (n = 45), and 1,077 carers.

Table 3.

Characteristics and results of cross-sectional studies

|

Study reference Country |

Patients | Comparison group | Carers | Measures | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Patient diagnosis (N) or (%) |

Gender (N) and age (M ± SD) or (Med, range) |

Details | Type of carers (N) |

Living with sufferer N (%) |

Age M ± SD |

In carers In patients |

Narrative results | |

|

Spain |

AN-R (39) BN Non purging (3) EDNOS-R (8) |

Female (49) Male (1) (12–18) |

None |

Mothers (48) Fathers (45) |

84 (90.3%) | 46.2 ± 4.5 |

AESED; ECI; FACES-II; FQ; HADS K-SADS-PL; EAT-26 |

- Mothers and fathers showed similar AESED scores - AESED scores in both mothers and fathers positively correlated with EAT-26 scores in patients - In fathers, but not mothers, self-reported anxiety together with AESED scores (b = 0.34) accounted for 31% of variance in patient’s EAT-26 scores |

|

Anastasiadou, Sepulveda, Sánchez al., 2016 Spain |

AN-R (39) BN Non purging (3) EDNOS-R (8) |

Female (49) Male (1) (12–18) |

SRD patients (47) HC (68) SRD mothers (47) SRD fathers (37) HC mothers (66) HC fathers (50) |

Mothers (48) Fathers (45) |

NR | 46.2 ± 4.5 |

AESED/AESSA; ECI; FQ; SF-36 K-SADS-PL |

- In fathers of people with EDs, AESED scores were higher than HCs but lower than SRD (controlling for hours of contact and age of offspring) - In mothers of people with EDs, AESED scores were higher than HCs but similar to SRD (controlling for hours of contact and age of offspring) |

|

[17] UK |

AN (152) |

Female (144) Male (8) 25.4 ± 8.5 |

None |

Mothers (120) Fathers (9) Spouses (22) Other (1) |

107 (70%) | 51.5 ± 9.9 |

AESED; DASS; FQ PCS EDE-Q; DASS |

- AESED scores were positively correlated with: contact time, psychological control, carer distress (DASS scores) and patient distress (DASS scores) - AESED scores were not correlated with patient age or ED symptoms - In structural equation models, AESED scores were not directly associated with carer distress (DASS), but was linked to carers’ own difficulty with eating |

|

Canada |

ED (NR) |

NR 18.0 ± 4.6 |

None |

Mothers (85) Fathers (39) |

NR | NR | AESED; CTS-ED; PvA |

- The AESED and four of five subscales (excluding “Turning a Blind Eye”) was positively associated with CTS-ED scores - The more that parents expressed fear about their involvement in their child’s recovery, the more likely they were to accommodate and enable ED behaviours of their child |

|

[39] Italy |

AN-R (60) AN-BP (7), Atypical AN (20) |

NR 15.4 ± 1.5 |

None |

Mothers (87) Fathers (87) |

NR | 49.8 ± 5.2 | FCQ-ED; TCI-R |

- Mothers and fathers showed similar levels of the collusion subscale of the FCQ-ED, but mothers were more avoidant than fathers - In multivariate regression analyses in both mothers and fathers, collusion was predicted by shorter illness duration and marital status (i.e., joined families) - In both parents, collusion was positively associated with coercion and with positive communication - In mothers only, collusion was also positively predicted by harm avoidance - In fathers only, collusion was positively predicted by cooperativeness - In both parents, no other variable was associated with collusion (i.e. novelty seeking, reward dependence, persistence, self-directedness, self-transcendence, psychiatric diagnosis) |

|

[46] UK |

AN (107) EDNOS -R (37) |

Female (132) Male (12) 16.8 ± 2.1 |

None |

Mothers (135) Father/Step-fathers (61) |

75% spent more than 21 h in contact | 48.7 ± 5.2 |

AESED; Care-ED; DASS-21; FQ; OSLO-3; Carer Skills BDSEE; DASS-21; Children’s Y-BOCS; SAS; SEED |

- AESED scores higher in mothers than fathers - Maternal AESED scores were positively associated with time spent caregiving, expressed emotion and carer distress - Maternal AESED scores were negatively associated with protective factors carer skills and social support - Patients’ social aptitude was negatively associated with maternal AESED scores, but other variables in patients showed no association (patient distress, severity of ED, obsessive–compulsive symptoms) - AESED scores mediated the relationship between objective burden (time spent caregiving) and subjective burden (carers’ distress) in mothers but not fathers |

|

[54] Italy |

ED (62) |

Female (55) 17.5 ± NR |

None |

Parents (92) Spouse (5) |

92 (95%) | 48.8 ± NR | AESED; DASS; FQ |

- AESED scores greater in carers of people with AN than carers of people with BN - AESED scores greater when the carer had previously suffered from an ED themselves - AESED scores greater in primary compared to secondary carers - AESED scores similar between carers that spent < 21 h/week and ≥ 21 h/week with the patient, and between inpatients and outpatients |

|

[55] Canada |

ED (NR) |

Female (100%) 18 ± NR (8–41) |

None |

Mothers (95) Fathers (48) |

NR | NR | AESED; CTS; PvA |

- Among mothers, treatment‐ engagement fear significantly predicted AESED scores - This relationship was not significantly mediated by maternal self-efficacy - Among fathers, neither self-efficacy nor treatment-engagement fear predicted AESED scores |

|

[56] Canada |

ED (NR) |

NR 18.0 ± 5.1 (12–41) |

None |

Mothers (87) Step-mothers (3) Step-fathers (5) Romantic partners (2) Relatives (1) |

NR | NR | AESED; Carer Fear Scale; Carer Self-Blame Scale; PvA |

- Carer fear positively predicted AESED total scores as well as every subscale other than two (Meal Ritual; Turning a Blind Eye) - Carer self-blame positively predicted AESED total scores, as well as every subscale other than two (Reassurance Seeking; Turning a Blind Eye) |

Abbreviations: AESED = Accommodation and Enabling Scale; AESSA = Accommodation and Enabling Scale for Substance Abuse; AN = anorexia nervosa; AN-BP = anorexia nervosa binge-purging subtype; AN-R = anorexia nervosa restricting subtype; BDSEE = Brief Dyadic Scale of Expressed Emotion; BN = bulimia nervosa; CTS = Caregiver Traps Scale; CTS-ED = Caregiver Traps Scale for Eating Disorders; DASS = Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale; EAT-26 = Eating Attitudes Test-26; ECI = Experience of Caregiving Inventory; ED = eating disorder; EDE-Q = Eating Disorder Examination-Questionnaire; EDNOS = eating disorder not otherwise specified; EDNOS-R = EDNOS restrictive type; FACES-II = Family Adaptability and Cohesion Evaluation Scale; FCQ-ED = Family Coping Questionnaire for Eating Disorders; FQ = Family Questionnaire; HADS = Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; HC = healthy controls; K-SADS-PL = The Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children; M = mean; N = number; NR = not reported; OSLO-3 = Oslo three-item social support scale; PCS = Psychological Control Scale; PvA = Parents Versus Anorexia Scale; SAS = Social Aptitude Scale; SD = standard deviation; SEED = Short Evaluation of Eating Disorders; SF-36 = 36-item Short-Form Health Survey; SRD = substance-related disorder; TCI-R = Temperament and Character Inventory-Revised; Y-BOCS = Children’s Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale Self-Report

Overall levels of accommodation in carers

Several studies reported comparisons between groups regarding the levels of accommodation in their caregiver samples. Two studies found that mothers and fathers of people with different EDs [3, 4] and AN specifically [39] had similar levels of accommodation, however in the latter study, mothers reported higher levels of avoidance. Additionally, accommodation was associated with shorter illness duration and families being “joined” [39]. In another study, accommodation scores were found to be higher in mothers than in fathers of young people with AN/EDNOS-R [46].

One study compared accommodation in carers (mostly parents) of people with AN and people with BN, finding greater levels of accommodation in carers of people with AN [54]. Additionally, another study that compared accommodation in parents of people with EDs to parents of people with substance-related disorders (SRDs) and healthy controls, found that both mothers and fathers of people with EDs reported higher accommodation than mothers and fathers of healthy controls [3, 4]. Additionally, fathers of people with EDs had lower accommodation scores than SRDs, but there was no difference between groups in mothers.

Accommodation and carer’s own mental health difficulties

In a study of parents of people with AN/EDNOS-R, maternal accommodation was found to be positively associated with their distress (measured by the Depression, Anxiety and Stress Scale; DASS) [46]. Similarly, a study based on the cognitive interpersonal maintenance model of eating disorders by Goddard et al. [17] highlighted that accommodation was positively correlated with carer distress and psychological control. However, structural equation modelling found that accommodation was not directly associated with carers’ distress but was indirectly linked via the carers’ own difficulties with eating.

Another study by Stefanini et al. [54] found that carers with a history of an ED themselves reported more accommodation (AESED scores) than those without a history of an ED.

Accommodation and other aspects of caregiving

Overall, three studies examined the role of fear in relation to accommodating and enabling in carers [27, 55, 56]. A study by Lafrance et al. [27] found that parents’ fears about engaging in their child’s treatment (as indicated by scores on the Caregiver Traps Scale for Eating Disorders [28],) was positively associated with AESED scores. Stillar et al. [56] found that both the fear associated with caring for loved ones, and self-blame, were associated with higher AESED scores in carers of adolescents and adults with EDs. In a later study by Stillar and colleagues (2022), higher levels of fear predicted higher accommodating and enabling behaviour in mothers but not fathers of adolescents and adults with EDs, and this relationship was not mediated by levels of self-efficacy. Therefore, all three studies indicate an association between fear and accommodation and enabling in carers.

Three studies examined the relationship between time spent caregiving and accommodating and enabling behaviours in carers. Stefanini et al. [54] found that AESED scores of carers (mostly parents) of people with EDs did not differ according to the time spent caregiving (< 21 h/week vs. ≥ 21 h/week) nor between carers of inpatients or outpatients. However, the findings indicated that primary carers scored higher in accommodation compared to secondary carers. However, contrasting findings were yielded by another study that found a positive association between accommodation and contact time in carers of adults with AN [17]. In line with these findings, another study also found a positive relationship between AESED scores and time spent caregiving in mothers of people with AN/EDNOS-R, as well as expressed emotion in mothers, and a negative association with protective factors carer skills and social support [46]. Notably, accommodation scores mediated the relationship between the objective burden (time spent caregiving) and subjective burden (carers’ distress) in mothers but not fathers.

Finally, one study using multivariate regression analyses [39] found that collusion in both mothers and fathers of people with AN was positively associated with both coercion and positive communication and can be associated with accommodating and enabling behaviour in parents. Additionally, this study found that in mothers, collusion was positively predicted by maternal harm avoidance, and in fathers, collusion was positively predicted by paternal cooperativeness.

Associations between accommodation and outcomes in patients

A study by [3, 4] examined the relationship between accommodation in parents and ED psychopathology (EAT-26) scores in adolescent offspring with various EDs, finding a positive correlation between AESED scores in both mothers and fathers and ED psychopathology in offspring. In regression models, it was found that fathers’ self-reported anxiety together with AESED scores accounted for 31% of variance in their offspring’s ED psychopathology, although this was not found in mothers.

A study conducted by Rhind et al. [46] found that the social aptitude of young people with EDs was negatively correlated with their mother’s accommodating behaviour, although in contrast to [3, 4], other measures in the patients were unrelated to parental accommodation (i.e., patient distress, severity of eating disorder and obsessive–compulsive symptoms). Similarly, another study of carers of adults with AN found that the accommodation scores of parents was not correlated with ED psychopathology in patients, although they were positively correlated with patient distress (measured by DASS) [17].

Qualitative studies

The data from the four qualitative studies are tabulated in Table 4. These studies included information from people with AN (n = 29) and EDNOS (n = 3), and a total of 38 carers. Three of these studies utilised semi-structured interviews [13, 35, 67] and one used focus groups [25]. Analytic methodology was heterogeneous across studies and included Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis [25, 67], Thematic Analysis [13] and narrative analysis [35]. Most of the studies had broad aims to explore the experiences of caregiving, although one study aimed to specifically explore family accommodation [13].

Table 4.

Characteristics and results of qualitative studies

| Study reference | Study design/aims | Patient diagnosis | Gender (N) | Type of carer (N) | Living with sufferer | Qualitative methodology | Accommodation Themes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | (N) | Age (M ± SD) | Age (M ± SD) | N (%) | Analytic methodology | ||

|

Fox et al., 2017 UK |

Qualitative study Aim: to investigate family accommodation in carers of AN |

AN-R (4) AN-BP (2) |

NR 27.0 ± NR |

Mother (5) Father (2) Sister (1) 56.6 ± 8.1 |

5 (63%) |

Semi-structured Interviews Grounded Theory (Charmaz, 2006) |

Accommodating and tolerating AN behaviours: All carers accommodated AN behaviours to some extent as a result of “stepping back” from the focus on food Turning a blind eye: Avoiding confrontation by ignoring AN behaviours Colluding: Complying with food rules, adapting family meals and eating patterns Internal conflict – ‘Inside you’re screaming’: Conflict associated with accommodating AN behaviours Efforts to reduce internal conflict: All justified accommodation, many felt that they have no choice thus reducing responsibility; many used avoidant coping strategies; some considered implementing stronger boundaries; many experienced “exploding” as a result of conflict building over time |

|

[25] UK |

Qualitative study Aim: to investigate how carers of young people with EDs manage uncertainty |

AN-R (10) EDNOS (3) |

NR 15.2 ± 1.7 |

Mother (9) Father (8) 49.6 ± 6.7 |

NR |

Five 45-min focus groups: 3 in mothers, 2 in fathers Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (Smith, 1996) |

Impact of AN-related uncertainty on the family: Parents reported changes in the whole family as a result of accommodating the ED and managing uncertainty, including avoiding uncertain situations; becoming rigid as a family; allowing space for things to not go according to plan |

|

[35] Italy |

Qualitative study Aim: to identify meaning associated with AN, the role of the caregiver and treatment experience |

AN (4) |

Female (4) 19.5 ± 7.2 |

Mother (4) 49.0 ± 7.4 |

4 (100%) |

30–60 min semi-structured telephone interviews Narrative analysis |

The accommodating family figure: The desire to reduce the patients’ distress majorly drives accommodation, which may fuel a cycle of negative reinforcement that increases accommodation. This may lead to increased caregiver burden and more severe symptoms due to increased reliance of the patient on the carer |

|

[67] Italy |

Qualitative study Aim: To explore how mothers experience family mealtimes when caring for a young person with AN |

AN (9) |

Female (7) Male (2) 19.6 ± 2.7 |

Mother (9) 48.9 ± 3.8 |

NR |

40–90 min semi-structured telephone/F2F interviews Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (Smith & Osborn, 2003) |

Managing mealtime combat through accommodation and acceptance: Mealtimes described as a “battlefield” and carers described a sense of “avoiding the fight” by accommodating ED behaviours, for example with the whole family playing along with a distortion of reality; ED behaviours are accepted for “the greater good”, in order to prioritise some level of eating. Accommodation also present due to believing that the battle against AN was already lost (carer burnout) |

AN = anorexia nervosa; AN-BP = anorexia nervosa binge-purging subtype; AN-R = anorexia nervosa restricting subtype; ED = eating disorder; EDNOS = eating disorder not otherwise specified; F2F = face-to-face; M = mean; N = number; NR = not reported; SD = standard deviation; UK = United Kingdom

In this study, accommodation was discussed as a by-product of efforts to take the focus off food for the sufferer [13]. The carers described a range of accommodating behaviour including complying with food rules, adapting family meals and eating patterns. Carers noted that this behaviour was to avoid confrontation although they noted that this resulted in an internal conflict. Self-justification of accommodation was that they have no choice to follow this coping strategy, although they also considered that a possible choice was to implement stronger boundaries. Some reported “exploding” as a result of the conflict building over time.

The study from Marinaci et al. [35] highlighted some of the causes and consequences of accommodating ED behaviours. Four mothers were interviewed, and reported that accommodation was driven by a desire to reduce their child’s distress, although this ultimately contributed to a negative cycle of reinforcement, including a greater reliance on the caregiver and an increase in the severity of symptoms.

In focus groups, parents reported how changes occurred across the whole family relevant to accommodation [25]. For example, accommodation within the family included avoiding uncertain situations, becoming more rigid as a family and allowing space for things to not go to plan.

Specifically regarding accommodation at mealtimes, respondents in the study by White et al. [67] described how mealtimes were like a “battlefield”, which facilitated accommodating behaviours as a way of “avoiding the fight”. More specifically, it was reported that families played along with distorted realities, and that ED behaviours were accepted for the “greater good” in order to facilitate some level of eating. Notably, carers in this study reported a sense of burn-out and accommodation stemming from a feeling that the battle against AN was already lost.

Discussion

The aim of this systematic scoping review was to systematically map the results of studies investigating accommodating and enabling behaviours in carers of people with EDs. A total of 36 studies were included, including randomised trials, longitudinal studies, cross-sectional studies and qualitative studies. The majority of participants had a diagnosis of AN but also included small number of people with BN, BED and ARFID. Most carers were mothers, although many studies included fathers, partners, grandparents and siblings. Across the interventional studies it was found that parents and carers showed a reduction in their accommodating and enabling behaviour across different interventions, but this was not significantly associated with a particular intervention. Several studies examined the association between carer accommodation and ED symptomatology or outcomes in people with EDs, which yielded mixed findings. Studies also found associations between accommodation and other aspects of the caregiving experience, such as higher carer distress and fear around engaging in treatment, and lower carer skills and levels of social support.

Overall, carers showed high levels of accommodating and enabling behaviours, which was the case for both mothers and fathers, although one study found higher accommodation in mothers compared with fathers [46]. Additionally, accommodation was found to be higher in carers of people with AN compared with BN [54], higher when there was shorter illness duration [39], higher when the carers had their own history of eating difficulties [54] and higher with more contact time [17].

There were a considerable number of RCTs and longitudinal studies assessing carer skills-based interventions. These studies broadly found no differential treatment effects between educational interventions based on the cognitive interpersonal model for carers (ECHO), and interventions more broadly tailored towards improving carer skills, in terms of reducing accommodating and enabling behaviour in carers. Given that the vast majority of studies used the AESED to measure accommodation, a future meta-analysis examining changes in carers’ accommodating behaviours after skills-based interventions for carers either in comparison to other interventions (e.g., TAU) or within-group, using longitudinal and RCT data, would address this finding with more precision. However, other outcomes relevant to the caregiver experience such as expressed emotion, fear, distress and subjective/objective burden in carers may also be beneficial to compare quantitatively.

It is possible that the levels of adherence to the intervention may moderate treatment efficacy. For example, one study reported that watching more educational videos was linked to a greater reduction in accommodation and enabling behaviour in carers and a greater reduction in ED symptoms in young people [16]. Overall carer-focused interventions showed a positive effect in reducing accommodation, which aligns with the models and approaches used to promote self-efficacy and positive emotional responses (including parental fear, self-blame, accommodation and expressed emotion), such as the New Maudsley Model [49] and Emotion Focused Family Therapy [26].

However, such models have the assumption that the accommodating behaviour of carers is a negative prognostic factor of outcomes in people with EDs. The findings of the studies included in this review are suggestive of more complicated picture. One cross-sectional and one longitudinal study found positive associations between accommodating behaviour in carers and ED severity [5, 47] and another study found that changes in accommodation over time were related to a decrease in ED psychopathology [16]. However, two cross-sectional studies [17, 46] and two longitudinal studies [8, 63] found contrasting results. In fact, one study found that higher accommodating scores at baseline were predictive of greater BMI at 1-year in patients [38], although it should be noted that another study found that carers with higher accommodating behaviours showed the greatest improvement in response to a carer intervention [16]. It is possible that this heterogeneity may reflect that changes in ED symptomatology over time do not follow a linear pattern. Indeed, one study found quadratic changes in ED symptoms over time (an initial improvement and then worsening), which were moderated by parental accommodation whereby high levels of accommodation resulted in a poorer trajectory and low levels of accommodation resulted in a better trajectory of symptoms [47].

The causes and consequences of accommodating behaviour in relation to the carer are of relevance to facilitate an understanding of the caregiving experience. In several cross-sectional studies, fear and anxiety were associated with greater accommodating behaviours in carers. For example, three studies found that carer fear [28, 55, 56] and self-blame in one study [56] was associated with higher accommodating behaviours. However, the directionality of this effect has not been ascertained and it is likely that accommodating the ED can also produce greater anxiety and distress in carers, thus constituting a bidirectional relationship. For example, higher levels of accommodating behaviours among carers were associated with higher levels of their anxiety and distress, and poorer psychosocial functioning [5, 46, 56]. This is corroborated by the qualitative studies, which suggested that the accommodation of symptoms was often at attempt at minimising their own distress, the distress of their loved one and of the wider family, or was caused by burn-out [67]. This often resulted in considerable internal conflicts [13] and an increased reliance on caregivers [35]. This demonstrates the vital importance of interventions such as ECHO for supporting carers and facilitating caregiver skills in a wider sense.

Strengths and limitations

This scoping review summarised the results of studies utilising a wide range of study designs and included studies across the ED spectrum. However, a limitation is that the results were markedly heterogeneous. There was marked diversity in the clinical and sociodemographic characteristics of the samples such as patient age, duration of illness, comorbidity, medical risk and contact time, which may impact on the accommodating and enabling behaviour of carers. Currently there are insufficient studies to make firm conclusions based on the specific characteristics of the patient presentation and carer features. Nevertheless, most of the included studies had fairly large sample sizes, increasing the confidence in the inferences and conclusions drawn.

Implications and future directions

It is apparent from the qualitative studies that carers may accommodate in order to minimise their loved one’s distress and to mitigate their own stress through the avoidance of conflict. Thus there can appear to be strong justifications for this behaviour, although excessive accommodating behaviour serves to avoid facing the ED fears, potentially allowing them to become entrenched. It is possible that the recent focus on exposure treatments for AN [37, 41, 64] may lead to more interest in accommodation and enabling which can be conceptualised as a form of safety behaviour. However, given that the majority of the studies included samples of carers of people with AN, there should also be further studies of accommodating and enabling behaviour in carers of people with other EDs, such as BN, BED and ARFID.

As aforementioned, nuance is evident in the literature—with one study finding a positive association between accommodation and outcomes in patients [38]. Particularly for people with comorbid neurodiversity, forms of accommodation such as making reasonable environmental adjustments, may be warranted to help the individual to navigate traits such as sensory sensitivity or cognitive rigidity. Future studies using qualitative research methods would be of benefit to explore in more depth the nuances of where, when, and for who accommodation may be perceived as beneficial by people with lived experience, their carers and their clinicians. Relatedly, this review included a study using the FASA-P (Family Accommodation Scale Anxiety—parent version), rather than the AESED, in children with ARFID [53]. In future studies, particularly if there is comorbidity with ASD/OCD and anxiety, it may be helpful to use the FASA-P or combine these measures.

Conclusion

Accommodating behaviour is commonly seen amongst carers of people with EDs, and these may serve to maintain the symptoms and ideally should be minimized. However, if they help the individual to navigate traits such as sensory sensitivity or cognitive rigidity it may be necessary to consider negotiating reasonable adjustments with regular reviews. This systematic scoping review found that accommodating behaviour was high in carers of people with EDs, which reduced following carer-focused interventions, although no single intervention emerged as superior in that regard. Additionally, accommodating behaviour was associated with carer burden and distress, although the evidence for its link to patient outcomes was mixed, reflecting the complexity of this behaviour for both the carers and their loved ones. Progress in the field would be enhanced if the measures of accommodating and enabling behaviours encompassed the large diversity in caregiving relationships. Additionally, further work is needed to examine the nuanced outcomes related to these behaviours within the system of support.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Author contributions

AK conducted the database search, extracted and synthesized the data, contributed to the initial draft of the manuscript and its review and editing. HH contributed to the conceptualization of the project, review editing of the manuscript and supervision of the project. JT contributed to the conceptualization of the project, the initial draft of the manuscript, its review and editing, and supervision of the project. JLK conducted the database search, extracted and synthesized the data, contributed to the initial draft of the manuscript and its review and editing, and supervision of the project. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Janet Treasure and Hubertus Himmerich have received salary support from the NIHR BRC at the South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust (SLaM) and KCL.

Availability of data and materials

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

Janet Treasure is one of the developers of the Accommodation and Enabling Scale for Eating Disorders (AESED), which is freely available upon enquiry.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Johanna Louise Keeler and Janet Treasure Mail have contributions equally to this work.

References

- 1.Albert U, Baffa A, Maina G. Family accommodation in adult obsessive–compulsive disorder: clinical perspectives. Psychol Res Behav Manag. 2017;10:293–304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anastasiadou D, Medina-Pradas C, Sepulveda AR, Treasure J. A systematic review of family caregiving in eating disorders. Eat Behav. 2014;15(3):464–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Anastasiadou D, Sepulveda AR, Parks M, Cuellar-Flores I, Graell M. The relationship between dysfunctional family patterns and symptom severity among adolescent patients with eating disorders: a gender-specific approach. Women Health. 2016;56(6):695–712. 10.1080/03630242.2015.1118728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anastasiadou D, Sepulveda AR, Sánchez JC, Parks M, Álvarez T, Graell M. Family functioning and quality of life among families in eating disorders: a comparison with substance-related disorders and healthy controls. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2016;24(4):294–303. 10.1002/erv.2440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson LM, Smith KE, Nuñez MC, Farrell NR. Family accommodation in eating disorders: a preliminary examination of correlates with familial burden and cognitive-behavioral treatment outcome. Eat Disord. 2021;29(4):327–43. 10.1080/10640266.2019.1652473. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ayton A, Ibrahim A, Downs J, Baker S, Kumar A, Virgo H, Breen G. From awareness to action: an urgent call to reduce mortality and improve outcomes in eating disorders. Br J Psychiatry. 2024;224(1):3–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dimitropoulos G, Landers A, Freeman V, Novick J, Schmidt U, Olmsted M. A feasibility study comparing a web-based intervention to a workshop intervention for caregivers of adults with eating disorders. Eur Eat Disord Rev. 2019;27(6):641–54. 10.1002/erv.2678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dimitropoulos G, Landers AL, Freeman VE, Novick J, Cullen O, Engelberg M, Steinegger C, Le Grange D. Family-based treatment for transition age youth: parental self-efficacy and caregiver accommodation. J Eat Disord. 2018;6:13. 10.1186/s40337-018-0196-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Eddy KT, Tabri N, Thomas JJ, Murray HB, Keshaviah A, Hastings E, Edkins K, Krishna M, Herzog DB, Keel PK, Franko DL. Recovery from anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa at 22-year follow-up. J Clin Psychiatry. 2017;78(2):17085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Feldman I, Koller J, Lebowitz ER, Shulman C, Ben Itzchak E, Zachor DA. Family accommodation in autism spectrum disorder. J Autism Dev Disord. 2019;49:3602–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fichter MM, Quadflieg N, Crosby RD, Koch S. Long-term outcome of anorexia nervosa: results from a large clinical longitudinal study. Int J Eat Disord. 2017;50(9):1018–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fiorillo A, Sampogna G, Del Vecchio V, Luciano M, Monteleone AM, Di Maso V, Garcia CS, Barbuto E, Monteleone P, Maj M. Development and validation of the family coping questionnaire for eating disorders. Int J Eat Disord. 2015;48(3):298–304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]