Abstract

Introduction:

Government agencies have identified evidence-based practice (EBP) dissemination as a pathway to high-quality behavioral health care for youth. However, gaps remain about how to best sustain EBPs in treatment organizations in the U.S., especially in resource-constrained settings like publicly-funded youth substance use services. One important, but understudied, determinant of EBP sustainment is alignment: the extent to which multi-level factors that influence sustainment processes and outcomes are congruent, consistent, and/or coordinated. This study examined the role of alignment in U.S. states’ efforts to sustain the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (A-CRA), an EBP for youth substance use disorders, during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Methods:

Our design was mixed-method QUAL→quan. We interviewed state administrators and providers (i.e., supervisors and clinicians) from 15 states that had completed a federal A-CRA implementation grant; providers also completed surveys. The sample included 50 providers from 35 treatment organizations that reported sustaining A-CRA when the COVID-19 pandemic began, and 20 state administrators. In qualitative thematic analyses, we applied the EPIS (Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment) framework to characterize alignment processes that interviewees described as influential on sustainment. We then used survey items to quantitively explore the associations described in qualitative themes, using bivariate linear regressions.

Results:

At the time of interview, staff from 80% of the treatment organizations (n =28), reported sustaining A-CRA. Providers from both sustainer and non-sustainer organizations, as well as state administrators, described major sources of misalignment when state agencies ceased technical assistance post-grant, and because limited staff capacity conflicted with A-CRA’s training model, which was perceived as time-intensive. Participants described the pandemic as exacerbating preexisting challenges, including capacity issues. Sustainer organizations reported seeking new funding to help sustain A-CRA. Quantitative associations between self-rated extent of sustainment and other survey items largely followed the pattern predicted from the qualitative findings.

Conclusions:

The COVID-19 pandemic amplified longstanding A-CRA sustainment challenges, but treatment organizations already successfully sustaining A-CRA pre-pandemic largely continued. There are missed opportunities for state-level actors to coordinate with providers on the shared goal of EBP sustainment. A greater focus on alignment processes in research and practice could help states and providers strengthen sustainability planning.

Keywords: youth substance use, evidence-based practice, sustainment, mixed method

1. Introduction

Despite the emergence of effective youth substance use treatments, there are still more than 9.8 million youth and young adults who meet criteria for SUD (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA), 2021). Government agencies have identified evidence-based practice (EBP) dissemination as a pathway to provide high-quality behavioral health care to youth in publicly-funded service settings (Chambers et al., 2005; Hoagwood et al., 2024; Rieckmann et al., 2011). Successful implementation and ultimately, sustainment of EBPs on a national scale are challenging due to heterogeneity across contexts (e.g., in funding, organizational structures) (Becan et al., 2020; Boaz et al., 2024; Guerrero et al., 2015; McHugh & Barlow, 2010). Implementation refers to the initial integration of an EBP into a routine care setting whereas sustainment refers to an EBP being maintained in a service setting, especially once external funding ends (Proctor et al., 2023; Rabin et al., 2008).

The Exploration, Preparation, Implementation, Sustainment (EPIS) framework can assist in unpacking key factors that influence EBP implementation and sustainment across multiple state and system contexts (Aarons et al., 2011; Moullin et al., 2019). In applying the EPIS framework for federal EBP implementation initiatives, treatment organizations signify the inner context with factors such as leader perspectives and staffing capacity. Factors external to the treatment organization lie in the outer context, and include state-level agencies, the policy environment and client characteristics. Bridging factors refer to the interconnections between inner and outer settings such as external organizations that provide referrals. The EBP itself can also be influential, which is captured in innovation factors (e.g., its structure, training model). To date, there has been ample research about individual barriers and facilitators to the implementation and (to a lesser extent) sustainment of youth EBPs (Dopp et al., 2023; Hunter et al., 2020; Peters-Corbett et al., 2023). However, major gaps remain in understanding how inner context, outer context, bridging and innovation factors interact to influence sustainment in multiple service systems across states.

The study of alignment can help address such gaps and guide sustained impacts of federal investment in multi-state EBP initiatives. Originally from the organizational management literature, alignment refers to the fit between an organization’s strategy (e.g., processes and decisions) and its objectives (Kathuria et al., 2007; von Thiele Schwarz & Hasson, 2013). Using EPIS, alignment helps describe the extent of fit or congruence between inner context, outer context, bridging, and innovation elements and actors around a common goal of EBP sustainment (Ehrhart & Aarons, 2022; Lundmark et al., 2021). A taxonomy of alignment characterizes five types: (1) Interorganizational: alignment between different agencies/organizations; (2) Internal Systems: alignment of policies, practices, procedures and systems within a treatment organization; (3) Vertical: extent to which leaders and staff at various levels are aligned in their support of sustaining the EBP; (4) Horizontal Unit: Extent to which culture is shared and/or the emphasis on EBP sustainment is shared across organizational units/departments; and (5) Innovation-provider/client: extent to which the EBP is aligned with the treatment organization’s clients and providers (Crable & Aarons, 2022; Ehrhart & Aarons, 2022).

A recent scoping review on the study of alignment in implementation research highlighted limited extant literature with most studies focused on EBP implementation and only five studies focused on sustainment (Lundmark et al., 2021). Moreover, only one of the five studies assessed alignment within a substance use service setting, and the EBP of interest was a quality improvement initiative not a treatment model (Stumbo et al., 2017). Further, most alignment research has narrowly focused on one specific element in the inner or outer context; more research examining the full range and complexity of alignment processes during EBP sustainment is indicated (Lundmark et al., 2021). To our knowledge, no study has used the taxonomy of five types of alignment (i.e., Interorganizational; Internal Systems; Vertical; Horizontal Unit; Innovation-provider/client) to characterize EBP sustainment within youth substance use service settings.

The Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (A-CRA) is one EBP for substance use that has garnered government support for large-scale implementation, thus presenting an opportunity to assess alignment across state contexts. Considered a well-established EBP (Hogue et al., 2018), A-CRA is a 12–14 week behavioral treatment for youth and young adults aged 12–25 (with some caregiver participation) that aims to improve substance use, mental health and social outcomes (Godley et al., 2016). Given A-CRA’s established effectiveness, national efforts to disseminate it have been supported by several federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) grant mechanisms, which provided funding and resources for A-CRA implementation activities (Dopp et al., 2022; Godley et al., 2011). SAMHSA issued “organization-focused” grants which were provided directly to treatment organizations then “state-focused” SAMHSA grants, which were 3–4 year awards (sometimes extended to 6 years) to state-level substance use agencies. In state-focused grants, state agency grantees were tasked with creating A-CRA training and sustainment infrastructure, which included financial and technical assistance to treatment organizations to intensively train their providers as A-CRA clinicians and/or supervisors.

Though governmental initiatives can be helpful in initial implementation of EBPs, the lack of alignment within systems undermine sustained EBP delivery and impact (Shelton et al., 2018). Maintaining alignment around EBP delivery is especially difficult in resource-constrained systems like publicly-funded youth substance use services. Specifically, recent studies on A-CRA sustainment after SAMHSA implementation support ended found that A-CRA was only partially sustained; these studies also measure sustainment quality to coincide with the view that sustainment is best captured on a continuum rather than as a checkbox (Huang et al., 2017; Hunter et al., 2017, 2020). Beyond standard service settings, major disasters like the COVID-19 pandemic exemplify “shocks to the system” that can create further misalignment and inhibit EBP sustainability. For example, EBP components, like worksheets, have been found to be difficult to deliver in a telehealth modality (Sklar, Reeder, et al., 2021). Despite such barriers, some research suggests that EBPs can be sustained during the COVID-19 pandemic (Cruden et al., 2021), and they remain a service priority (Palinkas et al., 2021; Purtle et al., 2022).

The current study assessed the role of multilevel alignment in sustaining A-CRA across several states after the completion of a SAMHSA implementation grant and during the COVID-19 pandemic. A key motivation for the study was to assess the pandemic’s potential influence on alignment processes and A-CRA sustainment. We used a mixed method QUAL → quan design with the function of convergence to assess whether select quantitative analyses could triangulate with patterns that could be drawn from qualitative results (Palinkas et al., 2011). The study was informed by the EPIS framework and the alignment taxonomy and had two central aims: (1) Characterize the role of five types of alignment in the sustainment of A-CRA including any perceived impacts of the pandemic on alignment, and (2) Explore quantitative associations with provider ratings of A-CRA sustainment, as predicted by the qualitative alignment themes.

2. Method

2.1. Current Study Context

We drew data from a larger study examining A-CRA implementation and sustainment that compared state-focused versus organization-focused funding strategies from SAMHSA. A detailed study protocol has been previously published (Dopp, Hunter, et al., 2022), so only details relevant to the current study are discussed here. The RAND Internal Review Board (Protocol #2020-N0887) approved the study. The current study sample were all involved in “state-focused” SAMHSA grants. The organization-focused grant type was not included in the current study because those grants ended more than 5 years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, and we only collected data up to 5 years post-award.

During the state-focused grant period, A-CRA training was provided by Chestnut Health Systems, the organization that led A-CRA development, and/or by approved local trainers. A-CRA has 19 procedures (e.g., functional analysis of substance use, problem solving, and communication skills); providers should tailor the sequence of delivering procedures to individual client needs (Godley et al., 2011). Trainee clinicians achieve A-CRA certification by demonstrating competency on at least nine core clinical procedures through reviews of recorded therapy sessions with real clients; however, trainees are encouraged to reach certification in all 19 procedures (Godley et al., 2016). Providers can also obtain certification as A-CRA supervisors, which enables a train-the-trainer model such that the certified supervisor can train and certify clinicians in A-CRA.

2.2. Procedures and Participants

In the larger study, participants were eligible if they were treatment providers (i.e., supervisors or clinicians) or state administrators who were involved in the SAMHSA grants within a 5-year period after each grant ended. The research team identified eligible participants through Chestnut Health Systems’ records of SAMHSA grantees. The research team contacted eligible participants via email, phone, and/or mail. State administrators were invited to complete an interview; providers were invited to complete an interview and a survey. Informed consent was obtained for each interview and survey. Participants were offered $25 for each interview or survey completed; however, a number of state administrators declined interview compensation as they considered participation a part of their job.

Trained research staff conducted the state administrators and providers interviews. Administrators worked in state-level substance use agencies and were in a leadership position that involved administering the state-level SAMHSA grants for A-CRA; administrator interviews could be individual or group. Interviews with providers were always done in an individual format. Research team members conducted interviews via telephone or Microsoft Teams. Interviews were approximately 45–60 minutes and were audio-recorded and transcribed (with de-identification). Providers completed a web survey hosted on Confirmit that asked about A-CRA knowledge, implementation/sustainment determinants, organizational factors, and demographics. We did not survey state administrators or collect their demographic information.

The overall state-focused sample from the larger study included 33 state administrators and 124 providers from 76 treatment organizations in 18 states. Eligibility criteria for the current study were that: (1) the SAMHSA grant had ended and (2) per provider interviews, the treatment organization was sustaining A-CRA as of March 2020, when COVID-19 was declared a public health emergency (President of the United States of America, 2020). The current sample included 20 state administrators and 50 providers from 35 treatment organizations in 15 states. Grants had been completed for an average of 2.83 years from when the data was collected, between December 2021 and July 2022. The current sample had a provider survey response rate of 96% (48 of 50 providers). Treatment organizations were defined as non-sustainers if A-CRA was no longer being delivered at the time of the provider interview. Importantly, administrators were from states that had sustainer organizations only (N=11), or a mix of sustainer and non-sustainer organizations (N=4)

2.3. Measures

2.3.1. Qualitative Interviews with Providers and State Administrators

Interview protocols for both state administrators and providers used open-ended questions and focused probes. Questions covered the initial implementation process of A-CRA during the SAMHSA grant, barriers/facilitators to A-CRA sustainment post-grant, and the impact of COVID-19 on A-CRA delivery. State administrators were asked additional questions about training infrastructure during the grant period and continued supports to treatment organizations post-grant. Provider interview protocols were tailored based on whether the treatment organization was sustaining A-CRA (sustainer) or not (non-sustainer); for example, non-sustainer interviews included questions about why A-CRA delivery stopped. Our interview and survey protocols have been published open access (Dopp et al., 2023; Dopp, Hunter, et al., 2022).

2.3.2. Quantitative Provider Survey Items

PRESS Score.

The Provider REport of Sustainment Scale (PRESS; Moullin et al., 2021) was used as a quantitative measure of unit-level EBP sustainment with the unit being treatment organizations. We tailored three PRESS items to measure A-CRA sustainment (e.g., “Staff use A-CRA as much as possible when appropriate”). The PRESS uses a 5-point Likert scale (0 = “Not at all” to 4 = “To a very great extent”) and the ratings on the three items were summed. Then, an aggregated average was calculated at the treatment organization level; higher scores indicated stronger sustainment. The PRESS items from participants in the current sample had strong internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .94).

Individual Items Selected as PRESS Score Predictors.

Once qualitative analyses were completed, we selected single items from the full range of provider survey questions as predictors of PRESS scores; further details are provided in the Analytic Plan section below. Single item measures are considered efficient and can comprise valid measure when the construct is unambiguous (Allen et al., 2022). We selected three individual items measuring A-CRA implementation difficulty, adapted from O’Loughlin et al. (1998): (1) “Financing A-CRA is/was difficult”; (2) “Finding time to prepare for A-CRA is/was difficult”; and (3) “Recruiting staff to work on A-CRA is/was difficult.”. Participants rated their level of agreement with each statement using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree to 5 = Strongly Agree), with higher scores indicating greater difficulty. We also selected a single item from the Agency Financial Status Scale (Maxwell et al., 2021): “Our agency has/had done a good job finding adequate funding for evidence-based practices.” Participants responded using a 5-point Likert scale (1 = “Not at all” to 5 = “Very great extent”), with higher scores signifying more adequate funding. Note that all four items selected were presented to non-sustainers with the preface, “Please think about the six-month period right before A-CRA treatment delivery ended” and worded in the past tense.

2.3.3. Analytic Plan

The study used a mixed method QUAL → quan design to assess whether select quantitative analyses could triangulate with qualitative results (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Palinkas et al., 2011). First, second and third authors conducted qualitative analyses under the supervision of the senior author. We elected to use thematic analysis as our analytic approach as it allowed us to take a theoretically-driven deductive top-down approach. We used EPIS to frame our understanding of the factors involved in alignment, which helped us identify themes by five types of alignment: Interorganizational Alignment, Internal Systems Alignment, Vertical Alignment, Horizontal Unit Alignment, and Innovation-Client/Provider Alignment. We considered treatment organizations as the inner context. Microsoft Word was used for qualitative analyses as the creation of tables facilitated the multilevel structure of the data (providers within treatment organizations that were sustainers or non-sustainers within states) and allowed for the flexibility to navigate themes across multiple informants (i.e., state administrators, providers). To further characterize alignment, we initially organized themes according to whether they captured a process of alignment or misalignment; we noticed that participant responses commonly described factors/processes that included a combination of alignment and misalignment, and thus we developed a third category of mixed alignment. Concurrently, interviews were reviewed for themes that characterized the COVID-19 pandemic’s influence on alignment. Throughout the entire thematic analysis, themes remained tracked according to the informant that reported on the theme (i.e., administrator from state with sustainer organizations only, administrator from state with sustainer and non-sustainer organizations, provider from a sustainer organization, and provider from a non-sustainer organization). We initially coded state administrators, provider interviews from sustainer organizations and provider interviews from non-sustainer organizations separately. Themes generated from state administrators were checked against sustainer and/or non-sustainer provider interviews within their state. Thereafter, themes from all sources were checked against each other across states until themes were “coherent, consistent and distinctive” (Braun & Clarke, 2006).

Aligned with reflexive thematic analysis (Campbell et al., 2021), we developed one thematic map for themes describing alignment types in predominantly sustainer organizations and another for themes predominantly describing non-sustainer organization alignment types. Creating and iterating maps is a process to identify relationships between themes until maps accurately represent the patterns in the qualitative data (Braun & Clarke, 2006). Through iterative refinement, we diagrammed the alignment themes according to the EPIS framework, and used lines to signify alignment, misalignment or mixed alignment. We also used symbols to signify whether the pandemic influenced alignment, whether themes were primarily generated from one specific type of informant interview, and whether major themes were shared between sustainer and non-sustainer organizations. Maps helped with interpretation of the dynamic process of multi-level alignment. To illustrate themes, select interview quotes are presented in the Results section.

Quantitative analyses were exploratory and not pre-planned, and thus were constrained to available survey items; surveys were not developed to directly measure alignment processes. Thus, from the provider survey, we selected items based on their potential to quantitatively explore the alignment qualitative findings; each model used a single item as the predictor variable and the aggregate mean PRESS score as the outcome variable. The PRESS score was used as it captures sustainment on a continuum. We conducted bivariate linear regressions in Stata version 17 (StataCorp, 2023). We also assessed effect sizes by calculating eta squared to help with interpretation of magnitude of findings based on common effect size guidelines in which .01 indicates a small effect, .06 a medium effect and .14 a large effect (Cohen et al., 2013).

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

The majority of treatment organizations reported sustaining A-CRA at the time of their interview (80%; 28 of 35). The 50 providers were on average 43.62 years old (SD = 9.57). Most were female, White, and had a Master’s degree. Table 1 provides additional demographic information for providers. 15 interviews were conducted with 20 state administrators; five of the 15 interviews were conducted with state administrator pairs.

Table 1.

Provider Characteristics

| Total | Sustainer | Non-sustainer | |

|---|---|---|---|

|

| |||

| Treatment organizations, n | 35 | 28 | 7 |

| Providers, n | 50 | 40 | 10 |

| Age, (M, SD) | 43.62 (9.57) | 43.89 (9.70) | 42.44 (9.48) |

| Role (n, %) | |||

| Clinician | 27 (54.00%) | 21 (52.50%) | 6 (60.00%) |

| Supervisor-Clinician | 2 (4.00%) | 1 (2.50%) | 1 (10.00%) |

| Supervisor | 21 (42.00%) | 18 (45.00%) | 3 (30.00%) |

| Gender (n, %) | |||

| Male | 15 (30.00%) | 13 (32.50%) | 2 (20.00%) |

| Female | 33 (66.00%) | 26 (65.00%) | 7 (70.00%) |

| Not reported | 2 (4.00%) | 1 (2.50%) | 1 (10.00%) |

| Race, (n, %) | |||

| White | 38 (76.00%) | 30 (75.00%) | 8 (80.0%) |

| Black/African American | 4 (8.00%) | 3 (7.50%) | 1 (10.00%) |

| Other | 5 (10.00%) | 5 (12.50%) | 0 |

| Not reported | 3 (6.00%) | 2 (5.00%) | 1 (10.00%) |

| Latinx Ethnicity (n, %) | |||

| No | 38 (76.00%) | 30 (75.00%) | 8 (80.0%) |

| Yes | 10 (20.00%) | 9 (22.50%) | 1 (10.00%) |

| Not reported | 2 (4.00%) | 1 (2.50%) | 1 (10.00%) |

| Education (n, %) | |||

| Bachelor’s Degree | 5 (10.00%) | 4 (10.00%) | 1 (10..00%) |

| Master’s Degree | 40 (80.00%) | 33 (82.50%) | 7 (7.00%) |

| Doctoral Degree | 2 (4.00%) | 1 (2.50%) | 1 (10.00%) |

| Other | 1 (2.00%) | 1 (2.50%) | 0 |

| Not reported | 2 (4.00%) | 1 (2.50%) | 1 (10.00%) |

3.2. Qualitative Results: Alignment Themes

We identified major themes for most alignment types that helped explain A-CRA sustainment during the COVID-19 pandemic. Notably, we found no themes for Horizontal Alignment. Compared to non-sustainer organizations, a higher number of themes were identified describing sustainer organizations with most themes characterizing alignment (vs. mixed or misalignment); non-sustainer themes were mostly in the misalignment category. Figures 1 and 2 present thematic maps summarizing prominent themes that describe alignment in sustainer and non-sustainer organizations, respectively.

Figure 1. Sustainer Thematic Map.

Note. Alignment themes dominant in organizations that sustained A-CRA using the EPIS framework. Themes are presented in square boxes within the respective EPIS domain, alignment types are presented in boxes with rounded corners, and lines between themes and provider types represent whether the theme described alignment and/or misalignment. See the Legend for specific conventions used in the formatting of the boxes and lines.

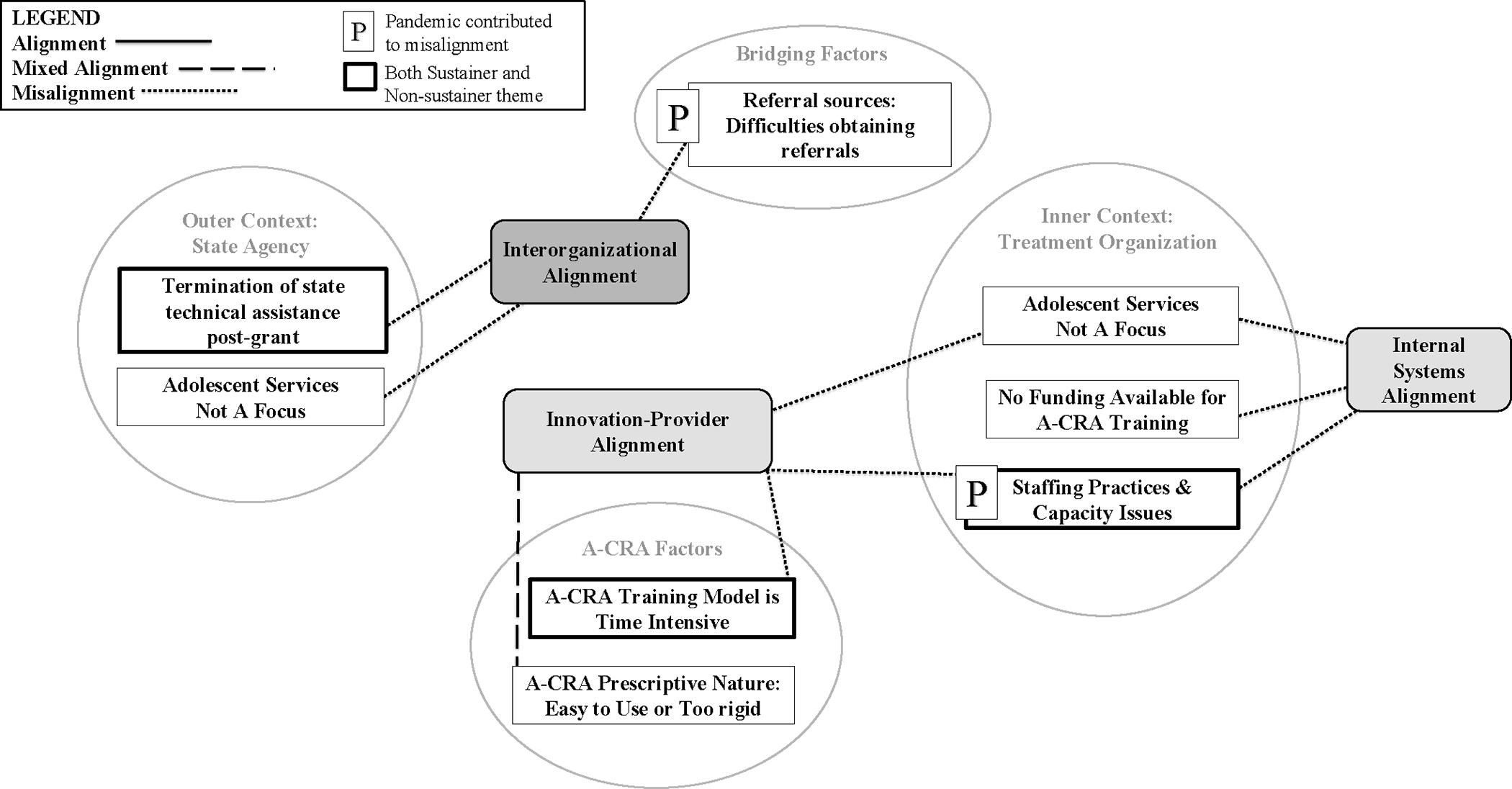

Figure 2. Non-sustainer Thematic Map.

Note. Alignment themes dominant in organizations that did not sustain A-CRA using the EPIS framework. Themes are presented in square boxes within the respective EPIS domain, alignment types are presented in boxes with rounded corners, and lines between themes and provider types represent whether the theme described alignment and/or misalignment. See the Legend for specific conventions used in the formatting of the boxes and lines.

The subsequent results sections are organized by a discussion of 16 alignment themes with quotes exemplifying the theme. Of the 16 themes, there were two major themes for sustainers and non-sustainers (Figures 1 and 2), 10 were predominantly for sustainers (Figure 1) and four were dominant for non-sustainers (Figure 2). In the following sections, we present themes relevant to both sustainers and non-sustainers first followed by those most prominent for sustainers, then non-sustainers. To further guide the reader, paragraph headers have two components beginning with the theme description; in parentheses, we label the type(s) of alignment the theme describes. For quotes, the type of informant is noted and in parentheses, we also specify whether the provider is part of a sustainer or non-sustainer organization; for administrators, we specify whether their states encompass sustainer organizations only, or both sustainer and non-sustainer organizations (i.e., “Both”).

3.2.1. Themes that Apply to Both Sustainers and Non-Sustainers

Theme 1: State Conclusion of Technical Assistance (Interorganizational Misalignment).

Among both sustainer and non-sustainer organizations, a major Interorganizational Misalignment theme was that states reportedly stopped providing technical assistance after the grant ended (Figures 1 and 2). Lack of continued state assistance was misaligned with providers’ ongoing needs to sustain A-CRA especially around problem solving and training new providers. Several state administrators acknowledged this lack of post-grant support. An administrator from a state with only sustainer organizations shared, “Activities to promote A-CRA specifically - I can’t say that there have been.” Another from a state with both sustainers and non-sustainers noted, “No, we did not track to see if they’re still utilizing the A-CRA model or not.” Some treatment organizations described that the lack of state attention to sustainability planning contributed to discontinuation of A-CRA, while others sustained A-CRA but still desired follow-up from the state agency. One provider shared:

There wasn’t a lot of outreach [from the state] regarding the transition about next steps and how can you stay involved, ‘what can we do? What are you doing? Let us talk with you.’ I would say the state could have done a little bit better in this transitional phase.

- Clinician (Sustainer)

Theme 2: Staff Capacity Issues and Time Intensive A-CRA Training Model (Innovation-Provider and Internal Systems Misalignment).

Sustainer and non-sustainer providers both described Innovation-Provider Misalignment with the A-CRA training model. They found the certification process to be too time intensive amongst chronic staff capacity issues, which were exacerbated during the pandemic (Figures 1 and 2). Issues with capacity could also be described as Internal Systems Misalignment. Subthemes were competing demands, turnover, and caseload size. Competing demands (e.g., documentation; clinicians’ high caseloads) seemed to take precedent over A-CRA training activities that were unbillable.

We only do [A-CRA training] with those that show interest and seem pretty motivated. What we found is A-CRA is a pretty intensive type of certification, and if the clinician that doesn’t have a track record with just doing paperwork with their other responsibilities, they’re likely not going to be able to follow through.

- Supervisor (Sustainer)

After the first main big training where they signed some people up, the agencies realized how much time it took and they were not as supportive when their people weren’t getting paid for all the hours that weren’t billable, so when they weren’t getting paid for like the supervision time or they weren’t getting paid for their clients to prepare for sessions, or they weren’t getting paid for when their clients were having to upload stuff or to do like those other various things that took more time away from the billable hours.

- Supervisor (Non-Sustainer)

High rates of turnover of clinicians who were A-CRA certified or training to become certified posed challenges to sustainment. Turnover resulted in either limited or an absence of A-CRA providers working at the treatment organization. A common staffing practice that exhibited Internal Systems Misalignment was that supervisors carried very small or no caseloads (~zero to two cases) thereby leaving them little to no opportunity to deliver A-CRA and help sustain it at the organizational level. Such misalignment was especially prevalent when the supervisor was the only provider at the organization trained in A-CRA. One supervisor from a non-sustainer organization described this misalignment, “Probably none of them [received A-CRA] because they weren’t my clients. They were the other therapists in the agency. Since I became supervisor, my caseload was kind of shortened.”

Staff capacity issues were heightened during the pandemic due to increased demand for services, which deprioritized A-CRA sustainment, and thus exacerbated misalignment.

I have not trained anyone personally [in the last six months]. Providing services during the pandemic has been challenging, and so I have not seen anybody pursuing some of these extra kind of things [like A-CRA training and certification] more recently just because folks are trying to...’we’re trying to serve people where we don’t have enough people to actually provide services, given the demand.

- Supervisor (Sustainer)

3.2.2. Themes that Apply Predominantly to Sustainers

Theme 3: State-Initiated Funds for A-CRA (Interorganizational Alignment).

State-initiated procurement and/or allocation of government funding (e.g., SAMHSA block grant; other state grants) to support treatment organizations’ sustainment of A-CRA was an Interorganizational Alignment theme, which we primarily identified from administrator interviews from states with sustainer treatment organizations (indicated in Figure 1). State support in financing of A-CRA post-grant included covering direct services not reimbursable for insurance and paying for internally hosted or Chestnut-contracted trainings, which may reduce effort needed by treatment organizations to secure funds and addressing turnover issues. For example, an administrator noted, “The State Opioid Response grant was a specialty grant that we helped with adolescent coverage for one of our A-CRA providers.” Another highlighted their efforts to align with organizations, “Through [a different SAMHSA grant], actually, what we’re looking to do is to expand and enhance [A-CRA] services, which would include additional training in A-CRA. As you can imagine, some of these agencies, you have turnover.”

Theme 4: Obtaining Referrals Amidst Challenges (Interorganizational Mixed Alignment).

Among sustainers, Mixed Interorganizational Alignment was also exhibited between treatment organizations and external organizations that referred clients for youth substance use services. Alignment was exhibited as sustainer organizations engaged in outreach efforts (e.g., ease referral process; marketing that A-CRA was an option) to help obtain referrals that could be matched to an A-CRA provider.

We’ve just started an initiative where we’ll have staff, we’ll have liaisons in all of our primary care clinics just to be a direct referral for youth issues as well as all of our local courts where we’ll have somebody sit in to directly take those referrals.

- Clinician (Sustainer)

Although the pandemic spurred barriers to receiving referrals, referrals seemed to be consistent enough to sustain A-CRA. The challenges were most pronounced when schools were referral sources. For example, when asked about the impact of COVID-19, one supervisor noted shifting trends in school referrals across phases of the pandemic:

It’s really our referrals are very low, very low. And, we really feel that it’s due to these kids, there was virtual learning and so they weren’t really going to school. They weren’t being seen... Now it’s starting because now that the kids are back in school, we’re receiving a lot more referrals.

- Supervisor (Sustainer)

Theme 5: Delivery of EBPs Encouraged or Required (Interorganizational, Internal Systems and Innovation-Provider Alignment).

A key theme related to Interorganizational Alignment between sustainer organizations and state substance use agencies was guidelines encouraging delivery of EBPs, with some agencies and organizations even requiring that EBPs are delivered. The EBP delivery theme equally relates to Internal Systems Alignment and Innovation-Provider Alignment given that the innovation A-CRA is an EBP and the organization/provider’s practice is to deliver EBPs.

We do have to do EBP for any of the insurances that we bill. So, Medicaid and Department of Mental Health funding, it has to be evidence-based, and A-CRA does follow that, and then also for our agency, we have to provide evidence-based practice.

- Supervisor (Sustainer)

Theme 6: A-CRA Delivery with Flexibility (Innovation-Client/Provider Alignment).

In sustainer organizations, providers described A-CRA as aligning with their own therapeutic approach and their clients’ needs because procedures could be delivered with flexibility, such as changing sequences of procedures, integrating other approaches and lengthening treatment. Several providers mentioned the specific notion that A-CRA meets clients where they are at, and providers described how A-CRA’s flexible delivery helped tailor treatment to individual clients.

I think the procedures and having some flexibility in doing them helps us to meet the client where they’re at. So it’s not like they come in and we say... ‘this [A-CRA procedure] is what we have to do.’ So we can kind of bring them in, ‘oh, you had an argument with mom. This sounds like a really good opportunity to talk about communication skills or anger management skills or whatever.’

- Clinician (Sustainer)

Theme 7: A-CRA Does Not Address Mental Health and Crisis Needs (Innovation-Client/Provider Misalignment).

An Innovation-Client/Provider sustainer theme of misalignment was that providers perceived that A-CRA did not adequately address clients’ mental health needs, or emergent life events (e.g., crises) that occurred during treatment.

I think [A-CRA] provided a structured way for therapists to address our clients’ substance use. But I think that, in some ways, it fell short with addressing some of their mental health concern, so we would have to get creative with how to do both A-CRA with also addressing some of their other needs as well.

- Clinician (Sustainer)

When asked whether A-CRA met the needs of the populations the provider serves, one supervisor said,

I do, with kind of two exceptions. The biggest one for me is crisis and how the model supports people that are in crisis. And, right now, they don’t have, to my knowledge still, a procedure that’s about that specifically...Then, the other piece is for people with co-occurring disorders, that there’s very little focus on the mental health side, with all the focus really being more on the substance abuse side. So, I think that part was challenging for us too.

- Supervisor (Sustainer)

Theme 8: Family Engagement Challenges and A-CRA Family Sessions (Innovation-Client/Provider Mixed Alignment).

In sustainer organizations, providers and clients exhibited mixed alignment with the A-CRA model component of family involvement. Providers had buy-in for the family/caregiver sessions of A-CRA, which they described as helping caregivers develop new skills to support the client. However, engaging caregivers was often challenging, which compromised sustainment of the full A-CRA model. One clinician shared their positive perspectives, “I think the structure of the sessions helped because you do have the family component with it as well. And, I think, with adolescents, that’s very important to have the family involvement, so the family can help carry on those interventions outside of the program.”

- Clinician (Sustainer)

Despite such positive appraisals of family involvement in A-CRA, providers highlighted misalignment with caregiver perspectives:

The hard part about A-CRA for the client was when we asked them to bring family members in. Family members have, frankly, not wanted to be a part of treatment. It’s just not what they want to do. Family members want to send you their kid and say, ‘Fix them.’ And that’s not how treatment works, and we want to involve family members in it, but some of the dyad work they have you do with the A-CRA program seemed a little hinky [i.e., suspicious] to family members, and I think that they struggled a little bit to buy in.

- Supervisor (Sustainer)

Theme 9: Funding Sought for A-CRA Training (Internal Systems Alignment).

Providers from sustainer treatment organizations reported that their organization set aside or sought funding to support A-CRA delivery (e.g., prosocial activities/engagement) and/or facilitate training for new providers, which demonstrates Internal Systems Alignment between leadership and providers centered on supporting A-CRA implementation activities. Organizations also applied to other grants to continue A-CRA training, when internal funds were not available.

Probably the biggest planning was that when we did write the [SAMHSA] Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinic grant. We wrote in significant funding for individuals to get trained in A-CRA so that we would have a significant amount of individuals who could provide those services.

- Clinician (Sustainer)

Theme 10: Organization-Level Train-the-Trainer Model (Internal Systems Mixed Alignment).

Many sustainer organizations reportedly adopted an A-CRA train-the-trainer model, in which a provider obtained the A-CRA supervisor certification and then trained and certified other providers at the organization. Some administrators and mostly sustainers also mentioned state efforts to establish a state-level train-the-trainer model citing barriers such as state staff turnover and low bandwidth to monitor fidelity; however, it was not considered a major theme based on how often it was mentioned in the data compared to other alignment processes. In the case of organizational-level train-the-trainer model, the Internal Systems Mixed Alignment was between organizational leadership and the supervisors acting as local trainers. However, the alignment did not seem to always extend to new providers in training as they often did not always pursue any type of certification and there seemed to be variability in whether training led to A-CRA delivery with fidelity. Staff capacity issues had some overlap with these subthemes.

My interest was A-CRA, so I did go out and did the training and then I did the training to become an A-CRA supervisor. And others who have gone to do the training with Chestnut are currently - I’m supervising them. Some of them, not all of them. Supervising them to their certification to become A-CRA clinicians as a supervisor.

- Supervisor (Sustainer)

We’ve had several groups that have gone through [A-CRA] training and I personally end up training a lot of those groups [internally], with Chestnut’s knowledge and approval, but there aren’t a whole lot of clinicians still today that are able to deliver that with fidelity, and it’s because people move up or move on. And the training lift is so high that keeping people trained has proven really challenging because it requires so much time and effort.

- Supervisor (Sustainer)

Theme 11: Organizational Leadership & Providers Proponents of A-CRA (Vertical Alignment).

Vertical alignment was exhibited with sustainer treatment organizations’ leadership, such as directors and CEOs, expressing support of supervisors/clinicians delivering A-CRA model. A major subtheme was supervisors being champions of A-CRA as they encouraged A-CRA to clinicians and thus, were key in helping sustain the A-CRA program in the organizations. Some supervisor champions were the in-house trainer who fostered enthusiasm from clinicians to pursue training and use the model.

I always have felt like I’ve had the full support of my supervisor. She’s wonderful. ... we talk about, in supervision or whatever, we’ll kind of go through procedures, talk about kids, clients. And I 100% know that I have her full support and she believes in the [A-CRA] model, she believes in the team, it’s a very warm, very super of environment.

- Clinician (Sustainer)

Theme 12: Telehealth Fosters/Hinders Client Engagement (Internal Systems and Innovation-Client Mixed Alignment).

Internal Systems Mixed Alignment also occurred with sustainer organization’s use of telehealth as a service delivery modality for A-CRA, as it both fostered and hindered client engagement during the COVID-19 pandemic. Many providers reported that their organization continues to offer telehealth appointments although pandemic restrictions have been eased. Alignment subthemes included fostering engagement due to preventing cancellations, eliminating transportation barriers, and expanding services to other parts of the state (e.g., rural areas).

One of the things that has been beneficial is the ability to quickly flex the telehealth if needed. And so I think that if a client’s not going to be able to make it to an appointment, but they can be able to switch to telehealth that makes it easier to maintain that appointment...Historically, if they missed that appointment, that was it. But now they can shift it to telehealth and still be able to have that very needed appointment.

- Supervisor (Sustainer)

Reasons for Internal Systems and Innovation-Client/Provider Misalignment with telehealth delivery of A-CRA include clients with substance use being particularly vulnerable to distraction within home environment and technological challenges. Participants spoke about benefits or difficulties for engagement in telehealth in a general sense for behavioral health services. However, some providers did raise that A-CRA specifically could be difficult to deliver over a video platform, which represents a form of Internal Systems Misalignment.

So maybe the engagement in the sense of full participation - I don’t know the word that I’m looking for, but it’s more challenging to implement [A-CRA] over zoom....with substance abuse, so many of the kiddos or the adolescents will isolate in their room and so it’s really difficult to keep their attention because they’re in their own environment and as a clinician, you can’t really manage what they’re doing there. So it’s challenging.

- Clinician (Sustainer)

[The pandemic is] affecting it a lot because now you have to do A-CRA by telehealth... Because of the pandemic and it’s a challenge doing A-CRA groups by telehealth, as opposed to having clients coming to the clinic to do them. And some of the barriers for telehealth is that you don’t get to see their reactions and their moods all of the time.

- Clinician (Sustainer)

3.2.3. Themes that Apply Predominantly to Non-sustainers

Theme 13: A-CRA Prescriptive Nature (Innovation-Client/Provider Mixed Alignment).

Among non-sustainer organizations, mixed alignment was indicated as there was variability in providers’ views of A-CRA. Some believed it was too rigid to meet client needs or fit with their therapeutic approach, whereas other non-sustainer providers expressed appreciation for the structure and prescriptive nature, noting it made A-CRA easy to deliver. One supervisor highlighted the lack of fit with clients, “I think because it is such a rigid model and prescribed, it was challenging to implement with the really complex youth we serve.” In contrast, another provider perceived it helped find starting points with clients:

The structure, especially being a new therapist at the time was very much appreciated and helpful to lead the sessions and get the most out of the sessions. Because sometimes it’s hard to know exactly what each client would like to work on, but then when you start to go through the different aspects of A-CRA, it kind of opens up different discussion opportunities.

- Clinician (Non-sustainer)

Theme 14: Organizations Lack Funding for A-CRA (Internal Systems Misalignment).

Internal Systems Misalignment was indicated as non-sustainer organizations did not have funding and/or did not pursue funding to invest in A-CRA training. One clinician describes the A-CRA program at their organization ending seemingly after a new grant was not secured:

“I don’t think we ever got the grant but no one ever told us anything else after that. A-CRA gets dissolved and we never heard anything after that.”

- Clinician (Non-sustainer)

Theme 15: Adolescent Services Not a Focus (Interorganizational and Internal Systems Misalignment).

In many non-sustainer organizations, adolescent services – where A-CRA programs were typically located within the organization – were de-emphasized or disbanded during the sustainment phase, which created Internal Systems Misalignment. There was also an example of Interorganizational Misalignment between non-sustainer treatment organizations and the state when adolescent services were no longer a state-level priority.

When I walked out of the adolescent treatment coordinator position in 2019, the focus on adolescent treatment just dissolved. And even within the agencies, the community mental health centers and our agencies, it just kind of dissolved. And so they’re trying to build that back up, but we had two or three adolescent programs close. And it was like all of a sudden we had no adolescent [services] for substance use in the state.

- State Administrator (Both)

Theme 16: Difficulties Obtaining Referrals (Interorganizational Misalignment).

Interorganizational misalignment occurred between non-sustainer treatment organizations and referral sources, as providers found it difficult to maintain relationships and obtain referrals. One supervisor described how the lack of referrals can impede the certification process, “What do you do when you’re not getting referrals and you don’t have a client that wants to be recorded? What do we do then? I think maybe there’s not, perhaps, as much empathy [from the certification process].” Difficulties with referrals seemed to be negatively influenced by the COVID-19 pandemic which ultimately led to discontinuing A-CRA.

I just think in general the referral sources were all down as well when COVID happened. So that obviously then impacted us getting referrals, because probation wasn’t getting as many kids, so they didn’t really have kids to send us. And I think in that way it affected us.

- Clinician (Non-sustainer)

3.3. Quantitative Results

Table 2 summarizes bivariate linear regression analyses based on the qualitative themes of staffing capacity issues (Internal Systems and Innovation-Provider Misalignment) that were present in both sustainers and non-sustainers, and having or obtaining funding for A-CRA activities (Internal Systems Alignment), which was prominent in sustainers. Quantitative analyses for these two themes were explored because they were the only survey items that were considered relevant to assess confirmation of alignment themes.

Table 2.

Quantitative Associations Between Provider Survey Items and Aggregate Sustainment Ratings

| PRESS Aggregate Score |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 95% CI |

||||||

| Alignment Type(s) | Model #: Predictor Item | B (SE) | LL | UL | p value | Effect Size |

|

| ||||||

| Innovation-Provider and Internal Systems Misalignment | Model 1: Finding time to prepare for A-CRA is difficult | −.71 (.39) | −1.50 | .07 | .07 | .07 |

| Model 2: Recruiting staff to work on A-CRA is difficult | −.96 (.35) | −1.67 | −.26 | .008* | .14 | |

|

| ||||||

| Internal Systems Misalignment |

Model 3: Financing A-CRA was difficult | −.74 (.41) | −1.56 | .08 | .08 | .07 |

| Model 4: Our agency has done a good job of finding adequate funding for evidence-based practices |

1.69 (.41) | .85 | 2.52 | <.001* | .27 | |

Note. PRESS Aggregate Score = Provider REport of Sustainment Scale average score aggregated at the treatment organization level; CI = confidence interval; LL = lower limit; UL = upper limit;

p < .05

In assessing triangulation with the staff capacity issues due to competing demands for provider time and the perceived time intensive training model, “finding time to prepare for A-CRA is/was difficult” was not significantly associated with PRESS scores (b=−.71, p = .07, eta squared = .07). However, “recruiting staff to work on A-CRA is/was difficult” was significantly negatively related to PRESS scores (b = −.96, p = .008) with a large effect size (eta squared = .14). Thus, difficulties recruiting staff for A-CRA delivery was associated with lower A-CRA sustainment scores.

Based on qualitative findings that sustainers aligned with A-CRA by finding funding for A-CRA activities and non-sustainers did not seem to have money to support A-CRA, we examined, but did not find a significant relationship between “financing A-CRA is/was difficult” and PRESS scores (b = −.06, p = .51, eta squared = .07). However, “our agency has/had done a good job of finding adequate funding for evidence-based practices” was positively related to PRESS scores (b = .45, p =.001) with a large effect size (eta squared = .27). Thus, an organization’s ability to financially support EBPs was related with higher A-CRA sustainment.

4. Discussion

The current study sought to characterize multilevel alignment processes of sustaining an EBP for youth substance use after the completion of a federal implementation grant to states and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Our study is the first to empirically examine alignment theory to understand EBP sustainment within the challenging resource constraints of youth substance use services. Our findings demonstrate how alignment theory can help explain EBP sustainment generally as well as develop recommendations to improve EBP sustainment in substance use disorder treatment specifically. Surprisingly, findings indicated that the pandemic seemed to have limited influence. Moreover, there was mixed triangulation between qualitative themes and quantitative results assessing staffing capacity factors and financing (i.e., time to recruit A-CRA providers and difficulty finding adequate funding for EBPs were associated with A-CRA sustainment ratings, but time to prepare for A-CRA and difficulties financing A-CRA were not). Still, our thematic maps display the dynamic and complex alignment processes that cut across multiple levels and actors to influence EBP sustainment. We focus our discussion of findings on the more robust qualitative results, consistent with our qual-dominant mixed-method design, but still note quantitative findings when useful.

Qualitative results indicated that both sustainer and non-sustainer providers perceived Interorganizational Misalignment with state agencies offering little to no post-grant technical assistance, which was also acknowledged by some administrators. In the perspectives of providers, it seems that SAMHSA’s grant design to have state agencies lead A-CRA implementation did not consistently result in state infrastructure supporting A-CRA sustainment. Indeed, support and resources for EBP delivery being contingent on short-term funding opportunities like time-limited grants is typical, well-documented and undermines sustainability (Hailemariam et al., 2019; Lengnick-Hall et al., 2020). However, state administrators described Interorganizational Alignment as they found funding to help maintain A-CRA delivery primarily amongst sustainer treatment organizations, including paying for some technical assistance activities. Relatedly, though it did not achieve status as a major theme, some efforts to establish a state-level trainer were mentioned by a few participants. These disparate reports about post-grant state support for A-CRA likely reflects limited communication between state agencies and organizations regarding their respective sustainability efforts. Similarly, a recent study found that these state-focused grants led to lower rates of A-CRA certification than the earlier SAMHSA grants awarded directly to treatment organizations, with challenges collaborating with state leadership support often noted as a barrier in state-focused grants (Dopp et al., 2023). Government agencies should consider designing grant or other funding opportunities that more clearly outline expectations for sustainability planning, including how state-level leaderships and organizations will remain aligned in the post-grant period. More detailed guidance on how government agencies can successfully support multi-state EBP implementation is forthcoming as an aim of the ongoing larger project, from which the current study data was drawn, is to identify policy implications for the governmental funding of EBPs (Dopp, Hunter, et al., 2022).

Potentially due to the lack of interorganizational coordination and low communication, Internal Systems Alignment was reported by sustainer organizations as they sought their own funding to sustain A-CRA. Research on financing of EBP implementation and sustainment efforts has found that organizations regularly need to leverage multiple funding sources (e.g., fundraising, contracts, writing grants, billing insurance) to financially sustain EBPs (Dopp, Manuel, et al., 2022; Jaramillo et al., 2019; Lengnick-Hall et al., 2020). Such efforts may pay off as our quantitative results showed a positive association between providers reporting adequate funding for EBPs and their ratings of A-CRA sustainment. Still, implementation strategies that target state-organization communication and Interorganizational Alignment, especially around funding, seem worth pursuing as there likely are state-level resources that could further bolster treatment organizations’ sustainment of EBPs. For example, contract arrangements can act as an EPIS bridging factor between government and treatment organizations invoking funding or other resources and enacting policies that encourage EBP delivery so that clients can benefit directly (Lengnick-Hall et al., 2020). An organization tool known as the Fiscal Mapping Process, which focuses on the financial sustainment of EBPs, could help organizations identify funding gaps that could be filled by state resources; the tool also has potential to bolster Horizontal Alignment between clinical and financial teams (Dopp et al., 2021; Dopp, Gilbert, et al., 2022);

Across both sustainers and non-sustainers, Innovation-Provider and Internal Systems Misalignment due to staffing capacity issues made it difficult to complete the “time intensive” training and certification model and to sustain A-CRA. Specifically, key capacity issues of competing demands for time and low staffing (e.g., turnover) were partially corroborated with quantitative analyses showing that difficulties recruiting staff to work on A-CRA were associated with lower sustainment. A recent review found that workforce turnover does indeed undermine EBP sustainability, as it creates need for training of new providers (Pascoe et al., 2021). Further, findings on capacity issues highlight that an organization’s priorities in staff recruitment and practices can signify their commitment to and climate for implementing and sustaining an EBP (Aarons et al., 2014). Some organizations in the current study appeared to be committed to maintain A-CRA as the adoption of the train-the-trainer model was a theme amongst sustainers only. The train-the-trainer model likely helped circumvent staffing issues as has been shown in previous literature (e.g., Jackson et al., 2021). Interestingly, variability of A-CRA adherence or fidelity was discussed within the context of the train-the-trainer model and also when discussing difficulties engaging families. Sustainment with imperfect or low fidelity has been documented (Huang et al., 2017; Shelton et al., 2018; Wiltsey Stirman et al., 2012), and there is growing recognition that insistence on delivering EBPs as tested in research settings is rarely a realistic goal in real-world settings (Park et al., 2018). Organizations can assess misalignment to identify which components of A-CRA training and clinical procedures have been the least feasible to sustain and why. To foster alignment within treatment organizations, several strategies have potential including the Leadership and Organizational Change for Implementation which targets Vertical Alignment for EBP delivery (Aarons et al., 2017) and the Interorganizational Collaborative Team model which could be useful for Internal Systems and Interorganizational Alignment (Hurlburt et al., 2014). Empirically investigating the influence of such implementation strategies on alignment processes can provide guidance about how to best promote EBP sustainability in resource constrained environments like publicly-funded substance use services.

Given the novelty of studying alignment within complexity of real-world EBP implementation, researchers may consider methodologies that would maximize organizational learning and inform theory development on alignment. One such method is the realist evaluation framework, as it focuses on knowledge translation into practices and helps to understand under what circumstances and through what mechanisms an intervention works on specific outcomes (Salter & Kothari, 2014). Realist evaluation would support an iterative process to develop alignment theory for behavioral health EBPs informed by empirical data. Additionally, coincidence analysis can help to identify the combinations of factors and alignment types that would lead to EBP sustainment using a causal inference approach (Whitaker et al., 2020). However, to conduct such work, research is needed in developing quantitative measures of alignment for behavioral health care that providers, organizational leaders, and state administrators could complete.

Despite our expectation that the COVID-19 pandemic would influence alignment and sustainment, qualitative findings revealed influence on only three alignment themes. These findings could be a testament to the organizations already having the opportunity to work through many sustainment barriers prior to the pandemic, given that they had been sustaining A-CRA on an average of nearly 3 years. Government funding agencies can learn from such organizations by identifying factors that contributed to successful sustainment in their previous grantees, and designing new grant opportunities that leverage and/or build up those factors across a range of grantee organizations. The pandemic mostly amplified longstanding sustainment challenges that sustainer organizations had been navigating pre-pandemic. First, the pandemic seemed to worsen staff capacity issues as provider time was further strained, thereby deprioritizing A-CRA training. De-prioritization of A-CRA training may not contribute to its sustainment per se, but it may be an adaptive organizational pandemic response for workforce well-being, given that high workload is associated with burnout (Yang & Hayes, 2020), Moreover, vertical misalignment on clinician psychological safety has been associated with lower EBP self-efficacy (Byeon et al., 2023). To support EBP sustainment amidst workforce well-being challenges, organizations may consider providing behavioral health resources to their staff, such as Coping First Aid, a coaching program that has been rated as beneficial by healthcare workers during the pandemic (Arnold et al., 2022).

Secondly, the pandemic influenced Interorganizational Misalignment between both sustainer and non-sustainers, and their referral sources due difficulties readily identifying youth substance use needs especially within remote learning contexts (i.e., themes 4 and 16). However, sustainers created Interorganizational Alignment by outreaching and marketing to referral sources during the pandemic, which may have counteracted the misalignment. Lastly, sustainers described Mixed Internal Systems Alignment with telehealth delivery as it helped engage some clients while hindering engagement of others. Other research supports mixed engagement within telehealth-delivered EBPs as the modality may foster attendance but not in-session participation (AlRasheed et al., 2022; Sklar, Reeder, et al., 2021). Furthermore, one study on a trauma-focused EBP found that parent engagement was facilitated through telehealth, which was not a prominent theme in the current study (Schriger et al., 2022). The presenting problem may be a determinant of client engagement in telehealth, especially if engagement is already a challenge within in-person delivery as is true for youth with substance use challenges (Dopp, Gilbert, et al., 2022). As telehealth may continue to be offered in public services amidst staffing challenges (Purtle et al., 2022), identifying engagement strategies for EBP video delivery would be prudent for providers and EBP developers, and would foster Internal Systems Alignment (Sklar, Ehrhart, et al., 2021).

5. Limitations

Though the current study makes valuable contributions, findings should be considered within the context of several limitations. First, we did not find any major themes related to Horizontal Alignment within treatment organizations, which may be due to our interview strategy. We focused on providers and did not interview staff at the same or similar levels within the organizational hierarchy (e.g., financial managers). Second, our provider sample was skewed towards sustainers, which likely resulted in missing themes relevant to non-sustainers. Third, we had a modest sample size which dictated our primarily qualitative study design, as we were limited in the types of statistical analyses we were adequately powered to conduct. Fourth, a different mixed-method approach that more strongly leveraged the sequential design, such as using qualitative findings to select the survey items asked of participants, could have revealed more comparable quantitative results. Fifth, our understanding of A-CRA sustainment was limited to self-reported status and we did not examine clinical outcomes of A-CRA. More in-depth research is needed to identify nuanced associations between alignment in the extent, quality, and clinical outcomes of A-CRA sustainment. Finally, our findings may not generalize to other EBPs for substance use, especially those with different requirements for implementation and sustainment.

6. Conclusions

Treatment organizations and their partners need to navigate numerous points of alignment and misalignment as part of their ongoing efforts to sustain EBP delivery. In the case of A-CRA in our study, post-grant funding remained essential to sustain the treatment, especially amidst chronic clinical staff turnover and COVID-19 pandemic impacts. Many treatment organizations in our sample were nimble and resourceful in sustaining A-CRA, but there are missed opportunities for state-level actors to coordinate with providers on the shared goal of sustainment. A greater focus on alignment processes in research and practice could help federal agencies, states and providers strengthen sustainability planning.

Acknowledgements:

First, we appreciate all the representatives from treatment organizations and state agencies who participated in the interviews and surveys, and those who helped us identify the best individuals to participate. This research would not have been possible without their willingness to participate in and/or discuss A-CRA initiatives with our team. We also thank Erika Crable for contributions to conceptualizing and analyzing alignment processes; Chau Pham, Danielle Schlang, and other staff in the RAND Survey Research Group for their support with recruitment and data collection; and Michelle Bongard for assistance with preparing the survey data for analysis.

Funding sources:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01DA051545 (Dopp, PI). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. BW was supported by an award from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (T32HS000046; Rice, PI).

Abbreviations:

- EBP

evidence-based practice

- A-CRA

Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach

- SAMHSA

Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration

Footnotes

Declaration of interest: MDG is the past center director for A-CRA training of clinicians and supervisors in the USA and other countries for Chestnut Health Systems, a not-for-profit organization. All other authors do not have any declarations of interest to disclose.

CRediT Authorship Contribution Statement:

Blanche Wright: Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization

Isabelle González: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing - Review & Editing

Monica Chen: Formal analysis, Validation, Writing - Review & Editing

Gregory A. Aarons: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing

Sarah B. Hunter: Funding acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing

Mark D. Godley: Funding acquisition, Writing - Review & Editing

Jonathan Purtle: Writing - Review & Editing

Alex R. Dopp: Funding acquisition, Conceptualization, Methodology, Formal analysis, Validation, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision

References

- Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Farahnak LR, & Sklar M (2014). Aligning leadership across systems and organizations to develop a strategic climate for evidence-based practice implementation. Annual Review of Public Health, 35(1), 255–274. 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182447 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Ehrhart MG, Moullin JC, Torres EM, & Green AE (2017). Testing the leadership and organizational change for implementation (LOCI) intervention in substance abuse treatment: A cluster randomized trial study protocol. Implementation Science, 12(1), 1–11. 10.1186/s13012-017-0562-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aarons GA, Hurlburt M, & Horwitz SM (2011). Advancing a conceptual model of evidence-based practice implementation in public service sectors. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 38(1), 4–23. 10.1007/s10488-010-0327-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen MS, Iliescu D, & Greiff S (2022). Single item measures in psychological science. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 38(1), 1–5. 10.1027/1015-5759/a000699 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- AlRasheed R, Woodard GS, Nguyen J, Daniels A, Park N, Berliner L, & Dorsey S (2022). Transitioning to telehealth for covid-19 and beyond: Perspectives of community mental health clinicians. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 49(4), 524–530. 10.1007/s11414-022-09799-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arnold KT, Becker-Haimes EM, Wislocki K, Bellini L, Livesey C, Kugler K, Weiss M, & Wolk CB (2022). Increasing access to mental health supports for healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond through a novel coaching program. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 13, 1–7. 10.3389/fpsyt.2022.1073639 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becan JE, Fisher JH, Johnson ID, Bartkowski JP, Seaver R, Gardner SK, Aarons GA, Renfro TL, Muiruri R, Blackwell L, Piper KN, Wiley TA, & Knight DK (2020). Improving substance use services for juvenile justice-involved youth: Complexity of process improvement plans in a large scale multi-site study. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 47(4), 501–514. 10.1007/s10488-019-01007-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boaz A, Baeza J, Fraser A, & Persson E (2024). ‘It depends’: What 86 systematic reviews tell us about what strategies to use to support the use of research in clinical practice. Implementation Science, 19(1), 1–30. 10.1186/s13012-024-01337-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V, & Clarke V (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Byeon YV, Brookman-Frazee L, Aarons GA, & Lau AS (2023). Misalignment in community mental health leader and therapist ratings of psychological safety climate predicts therapist self-efficacy with evidence-based practices (EBPs). Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 50(4), 673–684. 10.1007/s10488-023-01269-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell K, Orr E, Durepos P, Nguyen L, Li L, Whitmore C, Gehrke P, Graham L, & Jack S (2021). Reflexive thematic analysis for applied qualitative health research. The Qualitative Report, 26(6), 81–106. 10.46743/2160-3715/2021.5010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers DA, Ringeisen H, & Hickman EE (2005). Federal, state, and foundation initiatives around evidence-based practices for child and adolescent mental health. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 14(2), 307–327. 10.1016/j.chc.2004.04.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J, Cohen P, West SG, & Aiken LS (2013). Applied multiple regression/correlation analysis for the behavioral sciences (3rd ed.). Routledge. 10.4324/9780203774441 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Crable E, & Aarons G (2022). LOCI Indiana: Qualitative Codebook.

- Cruden G, Campbell M, & Saldana L (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on service delivery for an evidence-based behavioral treatment for families involved in the child welfare system. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 129, 108388. 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108388 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dopp AR, Gilbert M, Silovsky J, Ringel JS, Schmidt S, Funderburk B, Jorgensen A, Powell BJ, Luke DA, Mandell D, Edwards D, Blythe M, & Hagele D (2022). Coordination of sustainable financing for evidence-based youth mental health treatments: protocol for development and evaluation of the fiscal mapping process. Implementation Science Communications, 3(1), 1–15. 10.1186/s43058-021-00234-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dopp AR, Hunter SB, Godley MD, González I, Bongard M, Han B, Cantor J, Hindmarch G, Lindquist K, Wright B, Schlang D, Passetti LL, Wright KL, Kilmer B, Aarons GA, & Purtle J (2023). Comparing organization-focused and state-focused financing strategies on provider-level reach of a youth substance use treatment model: a mixed-method study. Implementation Science, 18(1), 1–18. 10.1186/s13012-023-01305-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dopp AR, Hunter SB, Godley MD, Pham C, Han B, Smart R, Cantor J, Kilmer B, Hindmarch G, González I, Passetti LL, Wright KL, Aarons GA, & Purtle J (2022). Comparing two federal financing strategies on penetration and sustainment of the adolescent community reinforcement approach for substance use disorders: protocol for a mixed-method study. Implementation Science Communications, 3(1), 1–17. 10.1186/s43058-022-00298-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dopp AR, Kerns SEU, Panattoni L, Ringel JS, Eisenberg D, Powell BJ, Low R, & Raghavan R (2021). Translating economic evaluations into financing strategies for implementing evidence-based practices. Implementation Science, 16(1), 66. 10.1186/s13012-021-01137-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dopp AR, Manuel JK, Breslau J, Lodge B, Hurley B, Kase C, & Osilla KC (2022). Value of family involvement in substance use disorder treatment: Aligning clinical and financing priorities. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 132, 108652. 10.1016/j.jsat.2021.108652 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhart MG, & Aarons GA (2022). Alignment: Impact on implementation processes and outcomes. In Rapport F, Clay-Williams R, & Braithwaite J (Eds.), Implementation Science (1st Ed., pp. 171–174). Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Godley SH, Garner BR, Smith JE, Meyers RJ, & Godley MD (2011). A large-scale dissemination and implementation model for evidence-based treatment and continuing care. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 18(1), 67–83. 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2011.01236.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godley S, Smith JE, Meyers RJ, & Godley MD (2016). The adolescent community reinforcement approach: a clinical guide for treating sustance use disorders. Chestnut Health Systems. [Google Scholar]

- Guerrero EG, Padwa H, Fenwick K, Harris LM, & Aarons GA (2015). Identifying and ranking implicit leadership strategies to promote evidence-based practice implementation in addiction health services. Implementation Science, 11(1), 69. 10.1186/s13012-016-0438-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hailemariam M, Bustos T, Montgomery B, Barajas R, Evans LB, & Drahota A (2019). Evidence-based intervention sustainability strategies: A systematic review. Implementation Science, 14(1), 1–12. 10.1186/s13012-019-0910-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoagwood KE, Richards-Rachlin S, Baier M, Vilgorin B, Horwitz SM, Narcisse I, Diedrich N, & Cleek A (2024). Implementation feasibility and hidden costs of statewide scaling of evidence-based therapies for children and adolescents. Psychiatric Services, 1–9. 10.1176/appi.ps.20230183 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogue A, Henderson CE, Becker SJ, & Knight DK (2018). Evidence base on outpatient behavioral treatments for adolescent substance use, 2014–2017: Outcomes, treatment delivery, and promising horizons. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 47(4), 499–526. 10.1080/15374416.2018.1466307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang W, Hunter SB, Ayer L, Han B, Slaughter ME, Garner BR, & Godley SH (2017). Measuring sustainment of an evidence based treatment for adolescent substance use. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 83, 55–61. 10.1016/j.jsat.2017.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter SB, Felician M, Dopp AR, Godley SH, Pham C, Bouskill K, Slaughter ME, & Garner BR (2020). What influences evidence-based treatment sustainment after implementation support ends? A mixed method study of the adolescent-community reinforcement approach. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 113, 107999. 10.1016/j.jsat.2020.107999 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter SB, Han B, Slaughter ME, Godley SH, & Garner BR (2017). Predicting evidence-based treatment sustainment: Results from a longitudinal study of the Adolescent-Community Reinforcement Approach. Implementation Science, 12(1), 1–14. 10.1186/s13012-017-0606-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurlburt M, Aarons GA, Fettes D, Willging C, Gunderson L, & Chaffin MJ (2014). Interagency Collaborative Team model for capacity building to scale-up evidence-based practice. Children and Youth Services Review, 39, 160–168. 10.1016/j.childyouth.2013.10.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jackson CB, Herschell AD, Scudder AT, Hart J, Schaffner KF, Kolko DJ, & Mrozowski S (2021). Making implementation last: The impact of training design on the sustainability of an evidence-based treatment in a randomized controlled trial. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 48(5), 757–767. 10.1007/s10488-021-01126-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaramillo ET, Willging CE, Green AE, Gunderson LM, Fettes DL, & Aarons GA (2019). “Creative financing”: Funding evidence-based interventions in human service systems. Journal of Behavioral Health Services and Research, 46(3), 366–383. 10.1007/s11414-018-9644-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kathuria R, Joshi MP, & Porth SJ (2007). Organizational alignment and performance: Past, present and future. Management Decision, 45(3), 503–517. 10.1108/00251740710745106 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lengnick-Hall R, Willging C, Hurlburt M, Fenwick K, Aarons GA, & Aarons GA (2020). Contracting as a bridging factor linking outer and inner contexts during EBP implementation and sustainment: A prospective study across multiple U.S. public sector service systems. Implementation Science, 15(1), 1–16. 10.1186/s13012-020-00999-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundmark R, Hasson H, Richter A, Khachatryan E, Åkesson A, & Eriksson L (2021). Alignment in implementation of evidence-based interventions: a scoping review. Implementation Science, 16(1), 93. 10.1186/s13012-021-01160-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]