Abstract

According to classical concepts of viral oncogenesis, the persistence of virus-specific oncogenes is required to maintain the transformed cellular phenotype. In contrast, the “hit-and-run” hypothesis claims that viruses can mediate cellular transformation through an initial “hit,” while maintenance of the transformed state is compatible with the loss (“run”) of viral molecules. It is well established that the adenovirus E1A and E1B gene products can cooperatively transform primary human and rodent cells to a tumorigenic phenotype and that these cells permanently express the viral oncogenes. Additionally, recent studies have shown that the adenovirus E4 region encodes two novel oncoproteins, the products of E4orf6 and E4orf3, which cooperate with the viral E1A proteins to transform primary rat cells in an E1B-like fashion. Unexpectedly, however, cells transformed by E1A and either E4orf6 or E4orf3 fail to express the viral E4 gene products, and only a subset contain E1A proteins. In fact, the majority of these cells lack E4- and E1A-specific DNA sequences, indicating that transformation occurred through a hit-and-run mechanism. We provide evidence that the unusual transforming activities of the adenoviral oncoproteins may be due to their mutagenic potential. Our results strongly support the possibility that even tumors that lack any detectable virus-specific molecules can be of viral origin, which could have a significant impact on the use of adenoviral vectors for gene therapy.

The observation that a number of viral oncogenes are recurrently expressed in virus-transformed cells and in the corresponding tumors led to the general view that the persistence of virus-specific genes is required to maintain the transformed cellular phenotype (21). In contrast to this conventional concept of viral oncogenesis, the “hit-and-run” hypothesis, originally proposed by Skinner (31), claims that viruses can mediate cellular transformation through an initial “hit,” while maintenance of the transformed state is compatible with the loss (“run”) of viral molecules. The hit-and-run concept raises the intriguing possibility of an etiological role of viral agents in tumors that lack any viral genes and proteins.

It is well established that cellular transformation by adenovirus type 5 (Ad5) is initiated through expression of the E1A oncogene, which is sufficient to immortalize cells, although transformation by E1A alone is inefficient and often incomplete (reviewed in references 6 and 29). The 19- and 55-kDa proteins expressed from the E1B transcription unit of Ad5 (E1B-19 kDa and E1B-55 kDa) can individually cooperate with Ad5 E1A proteins to increase transformation efficiency and to convert primary human and rodent cells to a fully transformed tumorigenic phenotype (6, 29). We and others have recently shown that two early region 4 (E4) gene products of Ad5, the E4orf6 (E4–34 kDa) and E4orf3 (E4–11 kDa) proteins, can also cooperate with E1A and E1A plus E1B to substantially enhance transformation (16, 18–20). Consistent with the conventional concept of viral oncogenesis, it has been reported that cells transformed by E1A and E1B continuously express the whole set of viral oncoproteins (7, 10, 35). However, evidence from earlier work suggested that the permanent presence and stable expression of E1 gene products are not absolutely required to maintain the transformed phenotypes of some cells, implying that hit-and-run mechanisms may play a role during adenoviral oncogenesis (12, 24). Moreover, Shenk and coworkers recently demonstrated that adenovirus E1A proteins can cooperate with the major immediate-early gene products (IE1 and IE2) of human cytomegalovirus (CMV) to mediate hit-and-run transformation of primary rat cells (28).

To evaluate the role of classical versus hit-and-run mechanisms in adenoviral oncogenesis, we compared cells transformed by E1A and E1B or E1A and E4orf6 or E4orf3 for the retention of virus-specific genes and proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids.

All viral proteins examined in this study were expressed from their respective complementary DNAs under the control of the CMV immediate-early promoter. The plasmids pCMV-E4orf3-neo, pCMV-E4orf6-neo, and pCMV-E1B-55 kDa-neo express the Ad5 E4orf3 (E4–11 kDa), E4orf6 (E4–34 kDa), and E1B-55 kDa proteins and were derived from the pcDNA3 vector (InVitrogen), which contains a neo gene conferring resistance to G418. The construction of pCMV-E4orf3-neo and pCMV-E4orf6-neo (formerly designated pCMV-E4orf3 and pCMV-E4orf6, respectively) has been described previously (20, 25). Plasmid pCMV-E1B-55 kDa-neo was generated by insertion of the E1B-55 kDa coding sequence into the BamHI and XbaI sites of pcDNA3. Plasmid pCMV-E1A expresses Ad5 E1A proteins, lacks a neo gene, and has been described previously (17).

Transformation assays and cell lines.

Primary cells were obtained from kidneys of 6- to 7-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats as previously described (18, 20) and grown in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FCS). For focus assays, subconfluent cells on 90-mm-diameter dishes were transfected by the calcium-phosphate procedure (11) with 1.5 μg of pCMV-E1A and 1 μg of empty vector-neo (pcDNA3), pCMV-E1B-55 kDa-neo, pCMV-E4orf6-neo, or pCMV-E4orf3-neo, as described previously (18). Total DNA was adjusted to 20 μg with empty vector and salmon sperm carrier DNA (Boehringer Mannheim). Four weeks after transfection, plates were stained with crystal violet, and dense foci of morphologically transformed cells were counted. Alternatively, individual foci or pools of foci were expanded into permanent cell lines.

Immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting.

For analysis of protein expression by immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting, cells were lysed in radioimmunoprecipitation assay (RIPA) buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.0], 150 mM NaCl, 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1% Nonidet P-40, 0.5% sodium deoxycholate, 1 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 0.3 μM aprotinin, 1 μM leupeptin, 1 μM pepstatin). Protein concentrations were normalized with the Bio-Rad protein assay, and equal amounts of total protein were subjected to immunoprecipitation and/or immunoblotting exactly as described previously (20). The following primary antibodies were used in this study: the mouse monoclonal antibodies M73, 2A6, and RSA3 directed against the Ad5 E1A, E1B-55 kDa, and E4orf6 proteins, respectively (8, 15, 27); and 6A11, a rat monoclonal antibody recognizing the Ad5 E4orf3 protein (20).

PCR.

Total cellular DNA was isolated by using the DNeasy tissue kit (Qiagen). PCRs were performed with 500 ng of genomic DNA or 50 ng of plasmid template and specific pairs of primer oligonucleotides with the following sequences: 5′-CCGAAGAAATGGCCGCCAGTCTTTTGGACCAGC-3′ (330-E1A-fw) and 5′-GCGTCTCAGGATAGCAGGCGCCATTTTAGGACGG-3′ (331-E1A- rev), 5′-GGAGCGAAGAAACCCATCTGAGCGGGGGGTACC-3′ (640- E1B55K-fw) and 5′-GCCAAGCACCCCCGGCCACATATTTATCATGC-3′ (641-E1B55K-rev), 5′-CACGGATCCATGACTACGTCCGG-3′ (1-E4orf6-fw) and 5′-CGCGAATTCGTCGACGCGCGAATAAACTGCTGC-3′ (48-E4orf6-rev), and 5′-CGCTGCTTGAGGCTGAAGGTGGAGGGCGC-3′ (363-E4orf3-fw) and 5′-CCAAAAGATTATCCAAAACCTCAAAATGAAG-3′ (364-E4orf3-rev).

Tumorigenicity testing.

Cells were harvested with a cell scraper, washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and resuspended in serum-free DMEM at a concentration of 107 cells per ml. NMRI (nu/nu) mice were injected subcutaneously with 106 cells, and tumor growth was recorded during a 6-week period as described previously (19).

Mutagenesis assays.

Mutagenesis assays were performed essentially as described by Shen et al. (28). Chinese hamster ovary (CHO)-D422 cells (2) were maintained in purine-free alpha-MEM medium containing 10% FCS. A total of 105 cells were plated on 90-mm-diameter dishes and transfected 2 days later by the calcium-phosphate precipitation technique followed by a 10% glycerol shock (11) with the indicated plasmids and salmon sperm carrier DNA as described above for the transformation assays. After transfection, cells were incubated in nonselective growth medium for 4 days to allow the manifestation of mutations. After that, 105 cells were plated in medium containing 10% dialyzed FCS and 10 μM 6-thioguanine to select for hprt mutants. For each culture, 100 cells were also plated in nonselective medium to determine the plating efficiency. Drug-resistant colonies were stained 7 to 8 days thereafter with crystal violet (1% in 25% methanol), and the mutation frequency was calculated from the number of resistant colonies compared to the plating efficiency.

RESULTS

The majority of cell lines transformed by E1A and E4orf6 or E4orf3 fail to express viral proteins and lack viral DNA sequences.

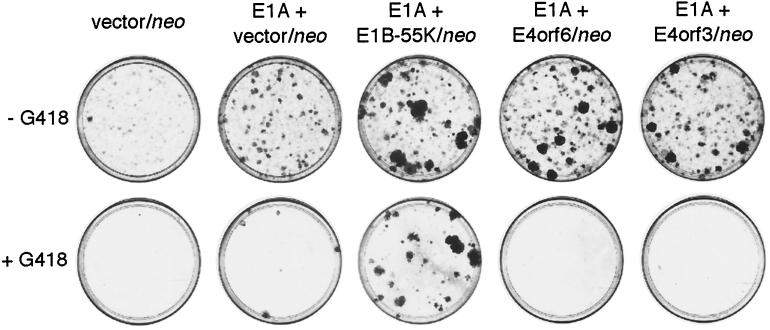

When we cotransfected primary baby rat kidney (BRK) cells with a plasmid encoding Ad5 E1B-55 kDa in combination with a neomycin resistance gene (pCMV-E1B-55 kDa-neo) and a plasmid expressing Ad5 E1A (pCMV-E1A lacking a neo gene), we consistently observed considerable numbers of G418-resistant, transformed colonies (Fig. 1 and Table 1). Similar results were obtained following cotransfections with pCMV-E1A and pCMV-E1B-19 kDa-neo (data not shown), indicating the presence of the E1B-55 kDa or E1B-19 kDa coding sequences in these cells. Cotransfections with a plasmid expressing the Ad5 E1A and E1B genes (pAd5XhoI-C) and constructs encoding Ad5 E4orf6 or E4orf3 plus a neo gene (pCMV-E4orf6-neo or pCMV-E4orf3-neo) gave rise to large numbers of G418-resistant colonies that could be readily expanded into permanent cell lines (ABS cells or ABT cells, respectively). All of these cell lines expressed substantial levels of the respective E1 and E4 proteins (18–20) (Fig. 2b and c, ABS1 and ABT29 cells). In contrast, transfections with combinations of pCMV-E1A and pCMV-E4orf6-neo or pCMV-E4orf3-neo in the absence of the E1B gene resulted in the formation of stably transformed colonies that were never (E4orf6) or very rarely (E4orf3) resistant to G418 (Fig. 1 and Table 1). These experiments suggest that the E4 oncogenes only regularly persist in transformed cells coexpressing E1B.

FIG. 1.

Cells transformed by Ad5 E1A and Ad5 E4orf6-neo or E4orf3-neo are G418 sensitive. Shown are representative plates from transfections of primary rat cells with empty vector-neo or combinations of pCMV-E1A with empty vector-neo, pCMV-E1B-55 kDa-neo, pCMV-E4orf6-neo, or pCMV-E4orf3-neo, which contain transformed colonies obtained in the absence or presence of the selective drug G418.

TABLE 1.

G418 resistance of transformed foci derived from transfections of primary rat cells with different combinations of Ad5 E1- and E4-expressing plasmids

| Expt | No. of G418-resistant foci/no. counteda

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Vector- neo | E1A/vector- neo | E1A/E1B-55kDa- neo | E1A/E4orf6- neo | E1A/E4orf3- neo | |

| 1 | 0/0 | 0/0 | NDb | 0/21 | 0/18 |

| 2 | 0/0 | 0/1 | 14/20 | 0/9 | 1/13 |

| 3 | 0/0 | 0/0 | 9/11 | 0/10 | 0/4 |

| 4 | ND | 1/2 | 22/24 | 0/12 | 0/12 |

| 5 | ND | 0/1 | 10/10 | 0/12 | 0/5 |

Numbers of G418-resistant foci/total number of unselected foci counted from two individual plates for each experiment are shown.

ND, not determined.

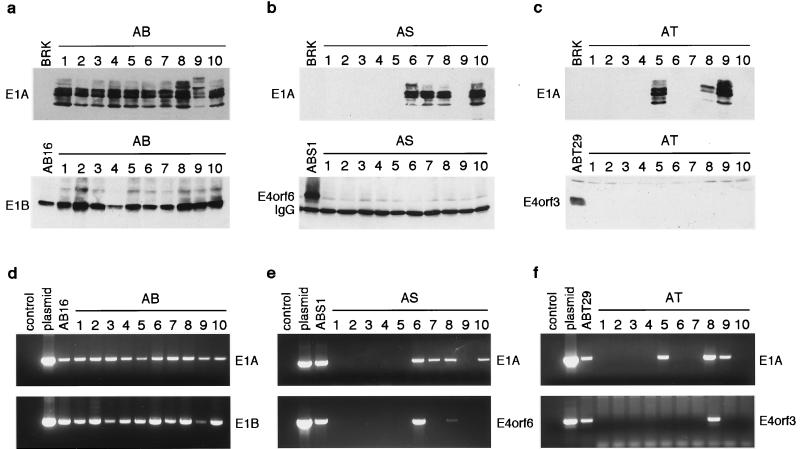

FIG. 2.

Absence of E1A and E4 proteins and genes in the majority of cell lines transformed by E1A plus E4orf6 or E4orf3. (a to c) Analysis of viral oncogene expression in 10 different AB (a), AS (b), and AT (c) cell lines by immunoblotting with M73 (E1A) or 2A6 (E1B-55 kDa) antibodies or by combined immunoprecipitation and immunoblotting with RSA3 (E4orf6) or 6A11 (E4orf3) antibodies. (d to f) PCR screening for the presence of E1A-, E1B-, E4orf6-, or E4orf3-specific DNA in 10 different AB (d), AS (e), and AT (f) cell lines. IgG, immunoglobulin G.

To confirm this idea, we derived a further set of cell lines from foci transformed by E1A/E1B-55 kDa (AB cells), E1A/E4orf6 (AS cells), and E1A/E4orf3 (AT cells) and subjected them to immunoblot analyses (Fig. 2a to c). As expected, all of the AB cell lines tested contained high levels of E1A and E1B-55 kDa proteins, while the previously discussed ABS and ABT cell lines additionally expressed the E4orf6 or E4orf3 proteins, respectively. In contrast, all AS and AT cell lines failed to express the corresponding E4 proteins at detectable levels. Curiously, even E1A expression was undetectable in 6 of 10 AS cell lines and 7 of 10 AT cell lines. To test whether the lack of viral protein expression was due to the absence of these genes, we screened our transformed cell lines by PCR for the presence of the respective DNA sequences (Fig. 2d to f). The results from these analyses show that all AS and AT cell lines failing to express E1A did indeed not contain the corresponding DNA. Likewise, no E4-specific DNA sequences were amplified from most of these cells, with the exception of two AS cell lines and one AT cell line. As a positive control, E1A and E1B sequences were PCR amplified from all AB, ABS, and ABT cell lines examined. These results clearly demonstrate that the E1A and E4 genes are only regularly retained and expressed in transformed cells when E1B is coexpressed. In the absence of E1B, the E1A and E4orf6 or E4orf3 genes can apparently cooperate to initiate transformation without subsequently being retained in the resulting cells.

A subset of hit-and-run-transformed cell lines exhibit tumorigenicity in nude mice.

To check whether our transformed rat cell lines exhibit a fully transformed phenotype even in the absence of viral oncogenes, we subcutaneously injected several AS, AT, and AB cell lines into athymic mice and monitored them for tumor development. The results summarized in Table 2 show that one of six AS cell lines (AS5), two of three AT cell lines (AT1 and AT3), and one of two AB cell lines (AB3) displayed tumorigenicity. Since AS5 and AT1 cells do not contain any detectable viral genes or proteins, we conclude that the persistence of Ad5 oncogenes is not absolutely required for maintaining the fully transformed cellular phenotype. Rather, the transient presence of the E1A and E4 genes may have generated an initial hit, resulting in the oncogenic conversion of the affected primary cells, which has been followed by the loss (“run”) of all viral genes after the transformed phenotype has been established.

TABLE 2.

Tumorigenicity of transformed rat cell lines in nude mice

| Cell linea | Viral protein expressionb | Tumor incidencec | Tumor size (mm2)d |

|---|---|---|---|

| AB16 | E1A, E1B-55 kDa, E1B-19 kDa | 6/6 | 85.4 ± 31.2 |

| AB2 | E1A, E1B-55 kDa | 0/6 | NAe |

| AB3 | E1A, E1B-55 kDa | 2/7 | 1.1 ± 0.7 |

| AS1 | None | 0/5 | NA |

| AS2 | None | 0/5 | NA |

| AS3 | None | 0/5 | NA |

| AS5 | None | 5/6 | 18.2 ± 6.8 |

| AS6 | E1A | 0/7 | NA |

| AS9 | None | 0/5 | NA |

| AT1 | None | 4/5 | 6.0 ± 2.7 |

| AT3 | None | 2/7 | 3.1 ± 2.3 |

| AT6 | None | 0/7 | NA |

AB16 cells have been described previously (17, 18). All other cell lines were derived from the present study.

Protein expression was monitored by immunoprecipitation and/or immunoblotting (Fig. 2a to c).

Number of nude mice with palpable tumors/total number of animals, determined 28 days after injection.

Mean tumor areas ± standard errors, measured 23 to 28 days after injection.

NA, not applicable.

Transient expression of E1A with E4orf6 or E4orf3 increases the mutation frequency at the hprt locus.

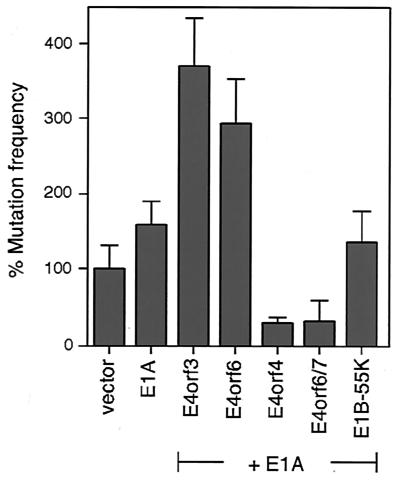

Given the fact that virtually all DNA tumor viruses including adenoviruses induce chromosomal damage and other mutations in the host cell genome (14, 23, 37), we next asked whether the oncogenic hit may be caused by mutations that accumulate during the transient presence of the viral E1A and E4 genes. To this end, we performed mutagenesis assays with the hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase (hprt) locus as an indicator gene to monitor the mutation frequency. We transiently transfected CHO-D422 cells with different plasmid combinations and maintained them in medium containing the selective drug 6-thioguanine. This purine analogue is converted to a toxic nucleotide through a reaction that requires a functional hprt-encoded enzyme. Thus, medium that contains 6-thioguanine kills normal cells but does not affect the growth of mutant cell clones harboring inactivating mutations within the hprt gene. The results from our mutagenesis assays (Fig. 3) indicate that the transient expression of Ad5 E1A can enhance the mutation frequency within the indicator gene by less than twofold, while transfection of Ad5 E4orf6 or E4orf3 alone had no mutagenic effect (data not shown). However, the combination of E1A with either E4orf6 or E4orf3 resulted in a significant increase in the number of resistant colonies compared to that with E1A alone, indicating that both E4 genes can act as comutagens in the presence of E1A. To check for specificity, we also tested two other Ad5 E4 genes (coding for E4orf4 and E4orf6/7), which do not induce focus formation in cooperation with E1A (18; unpublished results), for mutagenic activities in combination with E1A (Fig. 3). As expected, neither E4orf4 nor E4orf6/7 had any enhancing effect on the mutation frequency. Rather, a decrease was observed, which may be related to the ability of both of these E4 proteins to induce apoptosis (13, 30, 34). Similar results were obtained from cotransfections of E1A with E1B-55 kDa, which did not further increase the mutation frequency compared to E1A alone.

FIG. 3.

Transient coexpression of Ad5 E4orf6 or E4orf3 with Ad5 E1A increases the mutation frequency at the hprt locus. For mutagenesis assays, 105 CHO-D422 cells were transfected with either empty vector or plasmids encoding the indicated viral genes. After 4 days, cells were trypsinized and replated at a density of 105 cells per plate in selective growth medium containing 6-thioguanine. Drug-resistant colonies from two of these plates corresponding to a total of 2 × 105 cells plated in selective medium were counted 7 to 8 days thereafter, and numbers were corrected for the plating efficiency. The mean and standard deviation for at least three independent experiments are presented. After correction for the plating efficiency, the average number of 6-thioguanine-resistant colonies was 7 per plate for the vector control. The same results were obtained in two separate experiments in which we plated a total of 106 cells (10 plates with 105 cells/plate) in selective growth medium (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

The present study confirms previous observations that the expression of Ad5 E1A with either Ad5 E4orf6 or Ad5 E4orf3 can initiate the stable transformation of primary rat cells (16, 18, 20). Some of these cells are converted to a fully oncogenic phenotype, as demonstrated by their ability to form tumors in nude mice. Curiously, none of the cell lines tested contained the E4 proteins, and many failed to express E1A. Strikingly, the majority of transformed cell lines lacked any detectable viral DNA sequences. These observations are not compatible with the conventional concepts of virus-induced oncogenesis, in which the continuous expression of viral proteins is required to sustain the transformed phenotype. Rather, they fit the hit-and-run model, which claims that viral molecules are necessary for the initiation but not the maintenance of cellular transformation. The fact that the transient expression of E1A with E4orf6 or E4orf3 proved to be mutagenic suggests that the viral genes could mediate hit-and-run transformation by inducing oncogenic mutations in cellular genes. This idea has been suggested in a recent study by Shen et al. reporting that cells transformed by combinations of E1A with the HCMV IE1 and IE2 genes only transiently expressed the HCMV proteins, but accumulated mutations in the cellular p53 gene (28).

As yet, we can only speculate on the mechanism by which the viral oncogenes cause mutations. The mutagenic effects are apparently not based simply on the presence of viral DNAs, since plasmids containing complementary DNAs of E4orf3 or E4orf6 in an antisense orientation were not mutagenic (data not shown). More likely, the accumulation of genetic alterations requires the transient expression of the viral E1A and E4 genes. The Ad5 E1A protein has been shown previously to be involved in the generation of chromosomal aberrations (3). Interestingly, in these experiments, not only was the E1A-dependent mutagenic effect already apparent within 11 h after infection, but a contribution of E4 genes has not been ruled out (3). Very recently, Ad5 E1A has been associated with a specific human chromosomal translocation, which fuses the EWS and FLI1 genes to create a chimeric, oncogenic fusion protein (EWS-FLI1) characteristic of Ewing sarcomas (26). Moreover, recent work demonstrated that Ad5 E4orf6 and Ad5 E4orf3 are physically associated with the catalytic subunit of the DNA-dependent protein kinase, thereby inhibiting double-strand-break repair (1, 22). Besides, both E1A and E4orf6 can individually compromise the function of the tumor suppressor protein p53 (4, 32), a critical mediator of genome integrity, while E1A and E4orf3 associate with PML bodies (5), which have been recently implicated in genomic stability (36). Together, these E1A- and E4-dependent activities may lead to the accumulation of chromosomal aberrations and other mutations. However, continuous mutagenesis may be detrimental to cells, selecting against the permanent presence of the E1A and E4 genes. Conversely, the E1B proteins may favor retention of the E1A and E4 genes by virtue of their ability to efficiently interfere with different apoptosis pathways (reviewed in reference 33). Alternatively, E1B may actively suppress the mutagenic effects of the E4 proteins. However, this seems unlikely, since coexpression of E1B-55 kDa with E1A and E4orf6 or E4orf3 in CHO cells did not result in lower mutation frequencies than those of E1A and E4orf6 or E4orf3 alone (data not shown).

Adenovirus infections have never been convincingly linked to human oncogenesis, because none of the human neoplasms examined consistently contained adenoviral DNA (6, 29). Our results support the intriguing possibility that adenovirus infections may contribute to the development of some human tumors through a mutagenesis-based hit-and-run mechanism resulting in tumors that do not carry viral genes and proteins. If true, it would be extremely difficult, if not impossible, to implicate this widespread pathogen in human oncogenesis. Finally, our data may also have direct safety implications for the use of oncolytic adenovirus vectors currently being tested in clinical trials for human tumor therapy (9), because they contain the E1A and E4 genes.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Christian Endter for plasmid pCMV-E1B-55 kDa-neo, Franz Wiesenmeyer and Oskar Baumann for excellent technical assistance, Rainer Apfel for preparing the printouts, and Yuqiao Shen for help with the mutagenesis assays.

This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft and the Fonds der Chemischen Industrie. M.N. received an Emmy-Noether fellowship awarded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft.

REFERENCES

- 1.Boyer J, Rohleder K, Ketner G. Adenovirus E4 34k and E4 11k inhibit double-strand-break repair and are physically associated with the cellular DNA-dependent protein kinase. Virology. 1999;263:307–312. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9866. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradley W E, Letovanec D. High-frequency nonrandom mutational event at the adenine phosphoribosyltransferase (aprt) locus of sib-selected CHO variants heterozygous for aprt. Somatic Cell Genet. 1982;8:51–66. doi: 10.1007/BF01538650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Caporossi D, Bacchetti S. Definition of adenovirus type 5 functions involved in the induction of chromosomal aberrations in human cells. J Gen Virol. 1990;71:801–808. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-71-4-801. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dobner T, Horikoshi N, Rubenwolf S, Shenk T. Blockage by adenovirus E4orf6 of transcriptional activation by the p53 tumor suppressor. Science. 1996;272:1470–1473. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5267.1470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Doucas V, Ishov A M, Romo A, Juguilon H, Weitzman M D, Evans R M, Maul G G. Adenovirus replication is coupled with the dynamic properties of the PML nuclear structure. Genes Dev. 1996;10:196–207. doi: 10.1101/gad.10.2.196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Graham F L. Transformation by and oncogenicity of human adenoviruses. In: Ginsberg H S, editor. The adenoviruses. New York, N.Y: Plenum Press; 1984. pp. 339–398. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Graham F L, Smiley J, Russel W C, Nairn R. Characteristics of a human cell line transformed by DNA from human adenovirus type 5. J Gen Virol. 1977;36:59–72. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-36-1-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Harlow E, Franza B R, Jr, Schley C. Monoclonal antibodies specific for adenovirus early region 1A proteins: extensive heterogeneity in early region 1A products. J Virol. 1985;55:533–546. doi: 10.1128/jvi.55.3.533-546.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heise C, Sampson Johannes A, Williams A, McCormick F, Von Hoff D D, Kirn D H. ONYX-015, an E1B gene-attenuated adenovirus, causes tumor-specific cytolysis and antitumoral efficacy that can be augmented by standard chemotherapeutic agents. Nat Med. 1997;3:639–645. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hutton F G, Turnell A S, Gallimore P H, Grand R J A. Consequences of disruption of the interaction between p53 and the larger adenovirus early region 1B protein in adenovirus E1 transformed human cells. Oncogene. 2000;19:452–462. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kingston R E, Chen C A, Okayama H, Rose J K. Introduction of DNA into mammalian cells. In: Ausubel F M, Brent R, Kingston R E, Moore D D, Seidman J G, Smith J A, Struhl K, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York, N.Y: John Wiley & Sons; 1996. pp. 9.1.1–9.1.11. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuhlmann I, Achten S, Rudolph R, Doerfler W. Tumor induction by human adenovirus type 12 in hamsters: loss of the viral genome from adenovirus type 12-induced tumor cells is compatible with tumor formation. EMBO J. 1982;1:79–86. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1982.tb01128.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lavoie J N, Nguyen M, Marcellus R C, Branton P E, Shore G C. E4orf4, a novel adenovirus death factor that induces p53-independent apoptosis by a pathway that is not inhibited by zVAD-fmk. J Cell Biol. 1998;140:637–645. doi: 10.1083/jcb.140.3.637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marengo C, Mbikay M, Weber J, Thirion J P. Adenovirus-induced mutations at the hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase locus of Chinese hamster cells. J Virol. 1981;38:184–190. doi: 10.1128/jvi.38.1.184-190.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marton M J, Baim S B, Ornelles D A, Shenk T. The adenovirus E4 17-kilodalton protein complexes with the cellular transcription factor E2F, altering its DNA-binding properties and stimulating E1A-independent accumulation of E2 mRNA. J Virol. 1990;64:2345–2359. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.2345-2359.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Moore M, Horikoshi N, Shenk T. Oncogenic potential of the adenovirus E4orf6 protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11295–11301. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Neill S D, Hemstrom C, Virtanen A, Nevins J R. An adenovirus E4 gene product trans-activates E2 transcription and stimulates stable E2F binding through a direct association with E2F. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2008–2012. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.5.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nevels M, Rubenwolf S, Spruss T, Wolf H, Dobner T. The adenovirus E4orf6 protein can promote E1A/E1B-induced focus formation by interfering with p53 tumor suppressor function. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:1206–1211. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.4.1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nevels M, Spruss T, Wolf H, Dobner T. The adenovirus E4orf6 protein contributes to malignant transformation by antagonizing E1A-induced accumulation of the tumor suppressor protein p53. Oncogene. 1999;18:9–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1202284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nevels M, Täuber B, Kremmer E, Spruss T, Wolf H, Dobner T. Transforming potential of the adenovirus type 5 E4orf3 protein. J Virol. 1999;73:1591–1600. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1591-1600.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nevins J R, Vogt P K. Cell transformation by viruses. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 1. New York, N.Y: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 301–343. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nicolás A L, Munz P L, Falck-Pedersen E, Young C S H. Creation and repair of specific DNA double-strand breaks in vivo following infection with adenovirus vectors expressing Saccharomyces cerevisiae HO endonuclease. Virology. 2000;266:211–224. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.0062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paraskeva C, Roberts C, Biggs P, Gallimore P H. Human adenovirus type 2 but not adenovirus type 12 is mutagenic at the hypoxanthine phosphoribosyltransferase locus of cloned rat liver epithelial cells. J Virol. 1983;46:131–136. doi: 10.1128/jvi.46.1.131-136.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pfeffer A, Schubbert R, Orend G, Hilger-Eversheim K, Doerfler W. Integrated viral genomes can be lost from adenovirus type 12-induced hamster tumor cells in a clone-specific, multistep process with retention of the oncogenic phenotype. Virus Res. 1999;59:113–127. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1702(98)00131-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubenwolf S, Schütt H, Nevels M, Wolf H, Dobner T. Structural analysis of the adenovirus type 5 E1B 55-kilodalton–E4orf6 protein complex. J Virol. 1997;71:1115–1123. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.2.1115-1123.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sanchez-Prieto R, de Alava E, Palomino T, Guinea J, Fernandez V, Cebrian S, LLeonart M, Cabello P, Martin P, San Roman C, Bornstein R, Pardo J, Martinez A, Diaz-Espada F, Barrios Y, Ramon y Cajal S. An association between viral genes and human oncogenic alterations: the adenovirus E1A induces the Ewing tumor fusion transcript EWS-FLI1. Nat Med. 1999;5:1076–1079. doi: 10.1038/12516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sarnow P, Sullivan C A, Levine A J. A monoclonal antibody detecting the adenovirus type 5-E1b–58Kd tumor antigen: characterization of the E1b–58Kd tumor antigen in adenovirus-infected and -transformed cells. Virology. 1982;120:510–517. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(82)90054-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shen Y, Zhu H, Shenk T. Human cytomegalovirus IE1 and IE2 proteins are mutagenic and mediate “hit-and-run” oncogenic transformation in cooperation with the adenovirus E1A proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:3341–3345. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.7.3341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shenk T. Adenoviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. New York, N.Y: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 2111–2148. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shtrichman R, Kleinberger T. Adenovirus type 5 E4 open reading frame 4 protein induces apoptosis in transformed cells. J Virol. 1998;72:2975–2982. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2975-2982.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Skinner G R. Transformation of primary hamster embryo fibroblasts by type 2 simplex virus: evidence for a “hit and run” mechanism. Br J Exp Pathol. 1976;57:361–376. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Steegenga W T, van Laar T, Riteco N, Mandarino A, Shvarts A, van der Eb A, Jochemsen A G. Adenovirus E1A proteins inhibit activation of transcription by p53. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:2101–2109. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.5.2101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White E. Regulation of apoptosis by adenovirus E1A and E1B oncoproteins. Semin Virol. 1998;8:505–513. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yamano S, Tokino T, Yasuda M, Kaneuchi M, Takahashi M, Niitsu Y, Fujinaga K, Yamashita T. Induction of transformation and p53-dependent apoptosis by adenovirus type 5 E4orf6/7 cDNA. J Virol. 1999;73:10095–10103. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10095-10103.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zantema A, Fransen J A, Davis O A, Ramaekers F C, Vooijs G P, DeLeys B, van der Eb A J. Localization of the E1B proteins of adenovirus 5 in transformed cells, as revealed by interaction with monoclonal antibodies. Virology. 1985;142:44–58. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90421-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhong S, Hu P, Ye T Z, Stan R, Ellis N A, Pandolfi P P. A role for PML and the nuclear body in genomic stability. Oncogene. 1999;18:7941–7947. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.zur Hausen H. Induction of specific chromosomal aberrations by adenovirus type 12 in human embryonic kidney cells. J Virol. 1967;1:1174–1185. doi: 10.1128/jvi.1.6.1174-1185.1967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]