Abstract

Despite requirements by the American Psychological Association and the Psychological Clinical Science Accreditation System regarding training and education in cultural humility, questions remain regarding the presence and quality of the training in clinical psychology PhD and PsyD programs. This is a critical issue as inadequate training in diversity, cultural humility, and multiculturalism has substantial downstream effects on care for clients of color and may contribute to racial disparities and inequities in access to mental health services. We seek to explicitly evaluate key features of the conceptual model thought to improve the provision of mental health services for clients facing oppression and marginalization which includes perceptions of clinical psychology graduate programs’ training in and assessment of cultural humility. We also assess self-efficacy related to the application of cultural humility as well as actual practice of actions associated with cultural humility. Each of these domains are evaluated among a sample of 300 graduate students and faculty, clinical supervisors, and/or directors of clinical training (DCTs) and differences across position and race of participants were tested. Study findings highlight significant gaps between what trainees need to develop cultural humility and what they may actually be receiving from their respective programs. While findings suggest that there is still a lot of work to be done, understanding the state of the field with regards to clinical training in cultural humility is an important first step towards change.

Keywords: cultural humility, clinical psychology, graduate training, racism, clinical training

Introduction

In recent years there has been an increasingly recognized need to train antiracist clinical psychologists (Buchanan et al., 2021; Galán, Bekele, et al., 2021; Gee et al., 2022). Although clinical psychology training tends to focus heavily on research-based treatments, it is not evident to what extent this training extends to working with racially and ethnically marginalized populations. Despite requirements by the American Psychological Association (APA, 2022) and the Psychological Clinical Science Accreditation System (PCSAS; 2022) regarding training and education in diversity and multiculturalism, it is unclear whether and how programs are providing this training. This is problematic given inadequate training in diversity, cultural humility, and multiculturalism may cause harm to clients of color and may contribute to racial disparities and inequities in access to mental health services (Cook et al., 2017). Although clinical psychology training is only one part of addressing mental health inequities, it is imperative for programs to critically evaluate their multicultural training practices and ensure that providers of all races are equipped with the knowledge, skills, and self-awareness to work with people of color. The current manuscript describes data from 300 individuals within clinical psychology programs in the United States on training initiatives in cultural humility.

A key component of diversity and multicultural training is cultural humility (Hook et al., 2017). Cultural humility, put simply, is the expression of openness to others (Fowers & Davidoc, 2006). More specifically, cultural humility involves a lifelong intentional commitment to self-evaluation and self-critique characterized by an awareness of our limitations when it comes to our own cultural worldview and our ability to understand the worldview of others, as well as a person-centered stance that conveys respect and lack of superiority concerning the other person’s cultural background and experiences (Hook et al., 2013; Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998). It is through cultural humility that power imbalances can be identified and disrupted, and systems can be held accountable for inclusion and equity (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998).

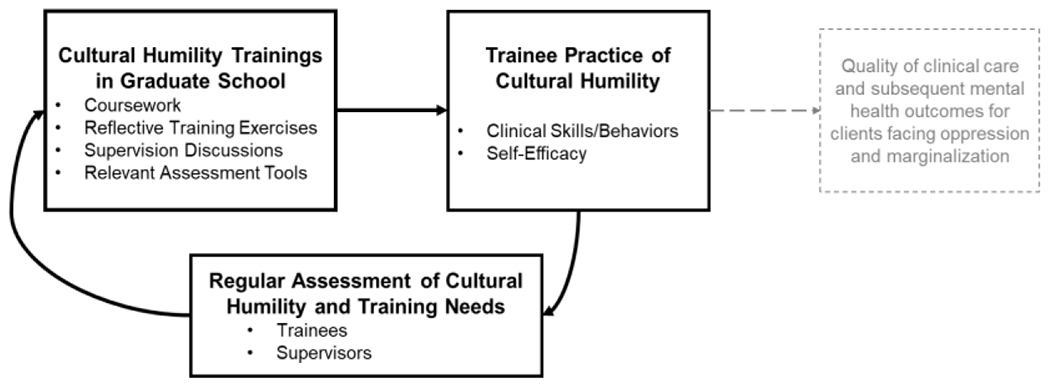

The foundation of cultural humility includes cultural self-awareness, cultural knowledge, and skills to communicate and interact with individuals of diverse cultural backgrounds (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998). Cultural self-awareness involves developing an awareness of one’s values, beliefs, assumptions, and behaviors and reflecting on how these features influence interactions with individuals from other cultures. Cultural knowledge involves being curious and learning about other cultures through didactic and experiential learning and then requires the active application of those experiences to the understanding of one’s client. Skills to communicate and interact require an understanding of how to best engage and treat clients in therapy given their cultural background (e.g., engaging in role as an advocate or consultant as appropriate), including acquiring the necessary skills when possible and understanding the limits of one’s competence (Sandeen et al., 2018; Sue, 2001; Sue & Torino, 2005). Although cultural humility is a necessary component of formal didactic and clinical training, it is a continual process that differs across contexts and situations (Tervalon & Murray-Garcia, 1998) and requires ongoing learning outside of individual training episodes (Sue, 2001) as well as regular assessment of cultural humility and training needs. This conceptual model for cultural humility training is depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

A conceptual model of the critical role of graduate training in cultural humility in improving the provision of mental health services for clients facing oppression and marginalization

Cultural humility is imperative to clinical psychology training, particularly in light of findings that suggest therapists frequently engage in microaggressions - “brief, everyday exchanges that send denigrating messages to people of color because they belong to a racial minority group” (Sue et al., 2007, p. 273) - when working with people of color. Among 120 racially and ethnically minoritized students receiving services at a university counseling center, 53% reported experiencing a microaggression from their therapist and this was associated with a lower quality therapeutic alliance (Owen et al., 2014). Another study of over 2,000 racially and ethnically minoritized individuals with experience in counseling found that 81% reported experiencing at least one microaggression in that setting (Hook et al., 2016). Importantly, other studies have found that experiencing racial microaggressions in therapy is associated with lower psychological well-being, lower satisfaction with therapy, and lower intentions to seek future services (see Hook et al., 2016 for a review). Perhaps unsurprisingly then, a now dated United States national survey found that Black Americans’ attitudes towards mental health services worsened, rather than improved, after receiving services (Diala et al., 2000). Clearly, the impact of microaggressions committed by therapists against people of color have detrimental effects on the therapeutic alliance, therapy progress, engagement in therapy, and well-being.

Training in cultural humility may be one way to improve the provision of mental health services for all people, and particularly people from minoritized cultural backgrounds. Indeed, cultural humility is associated with positive therapeutic outcomes for people of color, even when microaggressions occur. For example, cultural humility among therapists, as evidenced by successfully discussing a microaggression experience, has been shown to be associated with a higher quality therapeutic alliance (Owen et al., 2014) and may be associated with improvement in therapy (Hook et al., 2013). Client perception that therapists embody cultural humility is also associated with fewer experiences of microaggressions in therapy (Hook et al., 2016). This provides evidence that cultural humility is important for all people in clinical psychology to continually strive for in their practice and that, ideally, training in cultural humility should begin early on in clinical psychology training and be assessed often.

In the current manuscript, we seek to explicitly evaluate key features of the conceptual model depicted in Figure 1 thought to improve the provision of mental health services for historically marginalized clients. Specifically, training activities in graduate school serve to build a foundation in trainee practice of cultural humility through a combination of coursework that increases knowledge and skills in cultural humility practices, applied trainings in culturally-relevant assessment tools, and reflective training exercises and supervision discussions designed to increase self-awareness of clinician positionality and potential biases. We also evaluate to what extent clinical psychology graduate programs regularly assess cultural humility among trainees and supervisors, a critical part of a successful training model that is consistent with the lifelong intentional commitment to self-evaluation and learning that characterizes the cultural humility framework. Finally, we assess self-efficacy related to the application of cultural humility as well as their actual practice of actions associated with cultural humility. Each of these domains are evaluated among graduate students and faculty, clinical supervisors, and/or directors of clinical training (DCTs) and differences are tested. In addition, we test whether there are differences in perceptions across participants’ position in their program and participant race.

Method

Participants

Participants were 300 graduate students, faculty, and clinical supervisors from clinical psychology doctoral programs who completed an anonymous online survey. As described elsewhere (see Galán et al., preprint) eligible participants were all affiliated with United States-based APA-accredited clinical psychology PhD or PsyD programs as: (1) graduate students, including those currently completing their predoctoral clinical internship; (2) faculty, including tenured, tenure-track, and non-tenure track faculty; (3) Directors of Clinical Training (DCT); and/or (4) individuals who provided clinical supervision within the program’s in-house clinic over the past two years. A total of 498 people opened the survey link between April 2021 and August 2021, and 352 met the criteria for enrollment and provided informed consent. Thirty-five participants provided consent but exited out of the survey before answering any survey questions, and 17 participants ended the survey prior to responding to at least one of the key variables of interest, leaving a final analytic sample of 300 participants.

Participants were mostly female (n = 236; 78.7%), heterosexual (n = 195; 65.0%), and born in the United States (n = 257; 85.7%). Approximately two thirds of participants were graduate students (n = 202; 67.3%) and a third were faculty (n = 96; 32.0%). Of the faculty, approximately a third (n = 31; 32.2%) were DCTs and a third (n = 30; 31.3%) were clinical supervisors. Two respondents were clinical supervisors who were not faculty (i.e., total number of clinical supervisors: n = 32; 10.7%). Twelve of the DCTs also provided clinical supervision within their program’s in-house clinic.

Participants were predominantly from clinical psychology PhD programs (n = 268; 89.3%) and were affiliated with 112 different programs that were located in diverse geographic regions (urban: n = 146, 48.7%; rural: n = 51, 17%; suburban: n = 96, 32%; other: n = 7, 2.3%). Among respondents, 56.7% (n = 170) indicated that both of their parents graduated from high school, 18% (n = 54) have only one parent who graduated from high school, 23.7% (n = 71) indicated that neither parent graduated from high school, and 1.7% (n = 5) declined to provide their parents’ high school graduation status. In terms of racial identity, 1.7% (n = 5) of participants identified as American Indian or Alaska Native, 8.0% Asian or Pacific Islander (n = 24), 10.3% Black/African American (n = 31), 10.3% Hispanic/Latinx (n = 31), 1.7% Middle Eastern or North African (n = 5), 75.3 % White (n = 226), and 2.0% Other (n = 6). See Table 1 for additional demographic characteristics of the sample.

Table 1.

Race, gender, and sexual orientation frequencies for total sample and by position in program

| Item | Total n (%) |

Graduate Student n (%) |

Faculty, Supervisors, and/or Directors of Clinical Training n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Race | |||

|

| |||

| Non-Hispanic White | 197 (65.67%) | 123 (60.89%) | 74 (75.51%) |

| Non-Hispanic Black a | 26 (8.67%) | 17 (8.42%) | 9 (9.18%) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific | 24 (8.00%) | 23 (11.39%) | 1 (1.02%) |

| Hispanic, Latinx, or Spanish Originb | 31 (10.33%) | 22 (10.89%) | 9 (9.18%) |

| Multiracial/Other | 22 (7.33%) | 17 (8.42%) | 5 (5.10%) |

|

| |||

| Gender | |||

|

| |||

| Female | 236 (78.67%) | 171 (84.65%) | 65 (66.33%) |

| Male | 55 (18.33%) | 23 (11.39%) | 32 (32.65%) |

| Nonbinary | 8 (2.67%) | 8 (3.96%) | 0 (0%) |

| Queer | 3 (1.00%) | 3 (1.49%) | 0 (0%) |

| Another identity | 2 (0.67%) | 2 (0.99%) | 0 (0%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 1 (0.33%) | 1 (0.50%) | 0 (0%) |

|

| |||

| Sexual Orientation | |||

|

| |||

| Asexual | 3 (1.00%) | 3 (1.49%) | 0 (0%) |

| Bisexual | 40 (13.33%) | 30 (14.85%) | 10 (10.20%) |

| Gay or lesbian | 17 (5.67%) | 10 (4.95%) | 7 (7.14%) |

| Heterosexual | 195 (65.00%) | 126 (62.38%) | 69 (70.41%) |

| Mostly heterosexual | 31 (10.33%) | 21 (10.40%) | 10 (10.20%) |

| Queer | 18 (6.00%) | 16 (7.92%) | 2 (2.04%) |

| Another identity | 6 (2.00%) | 5 (2.48%) | 1 (1.02%) |

| Not sure | 2 (0.67%) | 2 (0.99%) | 0 (0%) |

| Prefer not to answer | 3 (1.00%) | 2 (0.99%) | 1 (1.02%) |

Note. Participants could endorse multiple gender and sexual orientation responses, thus, sums of percentages exceed 100%.

Listed as “Black” in subsequent tables and text.

Listed as “Latinx” in subsequent tables and in text

Procedures

The University’s Institutional Review Board approved the study. An online survey was created to collect anonymous information about anti-racism efforts in clinical psychology doctoral programs. Recruitment efforts involved distribution of the survey through social media (Twitter and Facebook), the Academy of Psychological Clinical Science (APCS) listserv, and direct emails to Department Chairs, Directors of Clinical Training (DCT), and Administrative Assistants in clinical psychology doctoral programs. Publicly available contact information for approximately 261 DCTs of clinical psychology PhD programs and 60 DCTs of PsyD programs was used to send emails asking the DCTs to share the information about the study with graduate students, faculty, and clinical supervisors in their programs. Email recipients were encouraged to share the survey link with other eligible graduate students, faculty, and clinical supervisors. After completing the web-based eligibility screener, individuals who met inclusion criteria then provided virtual written informed consent and were directed to the study survey which took, on average, 25 minutes to complete. Compensation for participation was not provided.

Measures

Data for the present report were drawn from a larger survey that assessed programs’ diversity, equity, and inclusion (DEI) initiatives and anti-racism efforts in four key areas: (1) clinical training and supervision, (2) curriculum and pedagogical approaches, (3) research and methods, and (4) recruitment, retention, and sense of belonging of faculty and graduate students of color (as outlined in in Galán, Bekele, et al., 2021). Due to a lack of validated measures for assessing programs’ current policies and efforts in these areas, the study authors developed survey items based on recent recommendations for approaches to advancing anti-racism and improving cultural humility training in clinical psychology (Galán, Bekele, et al., 2021). In total, respondents answered between 60 and 70 questions (including demographic questions). The exact number of questions an individual answered depended on their status in the program (i.e., graduate student, faculty, DCT, and/or clinical supervisor). For example, questions concerning coursework were asked of all respondents, including faculty not directly involved in clinical training. However, questions pertaining more directly to clinical work such as training in the use of a cultural formulation interview were only asked of graduate students, DCTs, and clinical supervisors.

The present study is focused specifically on ten questions related to student training in or practice of the three areas defining cultural humility: cultural knowledge (see: Coursework), cultural self-awareness (see: Clinical Supervisor Discussion of Cultural Identities, Reflective Training Exercises), and cultural skills to communicate and interact (see: Training in Assessment Tools, Training in Addressing Racism-Related Stress, Trainee Cultural Skills and Practices). Questions that assessed multiple domains of cultural humility are described in the “Cultural Humility Training Broadly” section. For instance, during a cultural plunge, individuals immerse themselves in settings in which they are the minority based on race, ethnicity, language, or some other aspect of their cultural identity. Students are then asked to reflect on their experiences, including biases and values they may have been unaware of before completing the activity. Thus, cultural plunge activities help to increase both cultural knowledge and cultural self-awareness and are thus described in the “Cultural Humility Training Broadly” section. In addition, two questions on program assessment of cultural humility are included. The specific questions are detailed below.

Cultural Humility Training Broadly

Cultural Humility Training Activities.

Graduate students, DCTs, and clinical supervisors were asked to indicate whether their program offers the following cultural humility training exercises: multiculturalism orientation, cultural plunge/cultural immersion, multicultural case conference, or didactics or workshops on cultural humility. For each activity, responses options were: “Yes, mandatory before starting clinical work,” “Yes, optional before starting clinical work,” “Yes, mandatory at some point in training,” “Yes, optional at some point in training,” “No,” “Don’t know,” or “Prefer not to answer.”

Perception of Cultural Humility Training.

To assess the quality of cultural humility training provided by graduate programs, we asked graduate students, DCTs, and clinical supervisors to indicate the extent to which they agreed with the following statement: “My program provides graduate trainees with up-to-date and empirically based training in cultural humility.” Participants responded to this question using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree,” with additional response options of “Don’t Know” and “Prefer not to answer.”

Cultural Knowledge Training

Coursework.

Graduate students, faculty, DCTs, and clinical supervisors were asked to respond to, “Does your program offer at least one graduate course focused on racial and social justice issues as they relate to clinical practice and clinical science (e.g., Psychology and Multiculturalism, Cultural Humility, or similar)?” Response options were “Yes, and the course is mandatory prior to graduation,” “Yes, and the course is mandatory prior to beginning clinical training,” “Yes, and the course is optional,” “No,” “Prefer not to answer,” and “Don’t know.” In addition, graduate students, DCTs, and clinical supervisors were asked to indicate agreement with the statement, “Diversity issues are infused throughout graduate courses rather than being isolated to a single lecture or course.” Response options were a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree,” with additional response options of “Prefer not to answer” and “Don’t know”.

Cultural Self-Awareness Training

Clinical Supervisor Discussion of Cultural Identities.

Graduate students and clinical supervisors were asked to indicate agreement with whether supervisors regularly discuss graduate student and client cultural identities within supervision. Response options were a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree,” with additional response options of “Prefer not to answer” and, for trainees only, “Not Applicable (I have not yet started clinical training or supervision).”

Reflective Training Exercises.

Graduate students, DCTs, and clinical supervisors were asked to indicate whether their program engages students in a cultural genogram exercise, an activity designed to encourage trainee exploration of their cultural identities, values, and beliefs. Response options were: “Yes, mandatory before starting clinical work,” “Yes, optional before starting clinical work,” “Yes, mandatory at some point in training,” “Yes, optional at some point in training,” “No,” “Don’t know,” or “Prefer not to answer.”

Cultural Skills Training

Training in Assessment Tools.

Graduate students, DCTs, and clinical supervisors were asked to respond to, “Graduate students in our program are trained in utilizing the DSM-5 cultural formulation interview or other instrument to assess cultural factors affecting the clinical encounter (e.g., racial identity, experiences of racial discrimination, cultural factors affecting help seeking).” Response options were “Yes,” “No,” “Prefer not to answer,” “Don’t know,” and “Not Applicable (my program does not have a training clinic).” Training providers in the use of the cultural formulation interview has been shown to improve cultural humility (Mills et al., 2016, 2017).

Training in Addressing Racism-Related Stress.

Graduate students were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed with the following statement: “I am satisfied with the clinical training in treating racial trauma or addressing racial discrimination offered by my program.” Participants responded to this question using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree,” with additional response options of “Don’t Know” and “Prefer not to answer.”

Trainee Cultural Skills and Practices.

Graduate students self-reported on the frequency in which they engage in the following practices when working with BIPOC clients: “assess individual strengths and resources such as resilience, self-efficacy, spirituality, faith, and religious values” and “assess factors related to racial microaggressions, racial discrimination, racial profiling, and racism, as potential factors triggering, precipitating or sustaining mental health problems.” Participants responded using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from “Always” to “Never,” with additional response options of “Prefer not to answer” and “NA - I have not worked with BIPOC clients.”

Program Assessment of Cultural Humility

Assessment of Trainee Cultural Humility.

Graduate students, DCTs, and clinical supervisors were asked to indicate the extent to which they agreed with the statement, “Trainee progress towards cultural humility or multicultural competence is regularly assessed in my program.” Participants responded to this question using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree,” with additional response options of “Don’t Know” and “Prefer not to answer.”

Assessment of Clinical Supervisor Cultural Humility.

Graduate students, DCTs, and clinical supervisors were asked to indicate agreement with the statement, “In-house supervisor progress towards cultural humility or multicultural competence is regularly assessed in my program.” Participants responded using a 6-point Likert scale ranging from “Strongly Disagree” to “Strongly Agree,” with additional response options of “Don’t Know” and “Prefer not to answer.”

Analytic Plan

Although 300 participants responded to at least one of the key variables of interest, some participants did not complete the entire survey, thus, not all analyses involved the full sample. Additionally, “prefer not to respond” and “don’t know” responses were treated as missing data. The number of respondents for each item is reported in Tables 2–5. To examine programs’ efforts to facilitate training in cultural humility and to assess trainee’s perceptions of their own cultural humility, we calculated descriptive statistics for the entire sample, as well as separately based on participants’ position in their program (i.e., graduate student versus faculty/clinical supervisors) and participants’ race.

Table 2.

Cultural humility training broadly, cultural knowledge training, and cultural skills training: Differences in perception by participants’ position in program

| Items | Total M (SD) or % “Yes” |

Graduate Students M (SD) or % “Yes” |

Faculty, Supervisors, and/or Directors of Clinical Training M (SD) or % “Yes” |

ANOVA or Chi-Square Test (χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CULTURAL HUMILITY TRAINING BROADLY | ||||

|

| ||||

| Cultural Humility Training Activities | ||||

|

| ||||

| As part of clinical training, my program offers the following cultural humility trainingsa (n=229): | ||||

|

| ||||

| Multiculturalism orientation | 51.50% | 47.62% | 68.18% | χ2 = 6.51, p < .05 |

|

| ||||

| Cultural plunge/Cultural immersion | 10.85% | 10.92% | 10.53% | χ2 = 0.01, p = 0.94 |

|

| ||||

| Multicultural case conference | 30.77% | 26.46% | 48.89% | χ2 = 9.27, p <.001 |

|

| ||||

| Didactics or workshops on cultural humility | 50.45% | 45.00% | 83.87% | χ2 = 14.31, p <.001 |

|

| ||||

| Perception of Cultural Humility Training | ||||

|

| ||||

| My program provides graduate students with up-to-date and empirically based training in cultural humility.b (n=209) | 3.29 (1.57) | 3.19 (1.55) | 4.41 (1.37) | F(1,207)=10.00 p <.01 |

|

| ||||

| CULTURAL KNOWLEDGE TRAINING | ||||

|

| ||||

| Coursework | ||||

|

| ||||

| Diversity issues are infused throughout graduate courses rather than being isolated to a single lecture or course. b (n = 294) | 3.72 (1.52) | 3.39 (1.56) | 4.44 (1.17) | F(1,292)=37.8, p <.001 |

| Does your program offer at least one graduate course focused on racial and social justice issues as they relate to clinical practice and clinical science? a (n = 300) | 76.00% | 70.80% | 86.70% | χ2 = 7.36, p <.05 |

|

| ||||

| CULTURAL SELF-AWARENESS TRAINING | ||||

|

| ||||

| Clinical Supervisor Discussion of Cultural Identities | ||||

|

| ||||

| Clinical supervisors regularly discuss trainee cultural identities during supervision.b (n=195) | 3.07 (1.58) | 2.80 (1.50) | 4.44 (1.27) | F(1,193)=34.92, p <.001 |

| Clinical supervisors regularly discuss client cultural identities during supervision.b (n=196) | 4.22 (1.50) | 4.05 (1.53) | 5.06 (0.98) | F(1,194)=13.42 p <.001 |

|

| ||||

| Reflective Training Exercises | ||||

|

| ||||

| Cultural genogram exercise a (n=229) | 21.40% | 16.93% | 42.50% | χ2 = 10.55, p <.001 |

Note. M = Mean. SD = standard deviation.

Responses were coded as yes versus no.

Responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

Table 5.

Cultural skills training and practices and program assessment of cultural humility: Differences in perception by participants’ race

| Items | Asian (1) M (SD) or % “Yes” |

Black (2) M (SD) or % “Yes” |

Latinx (3) M (SD) or % “Yes” |

White (4) M (SD) or % “Yes” |

ANOVA or Chi-Square Test (χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CULTURAL SKILLS TRAINING AND PRACTICES | |||||

| Training in Assessment Tools | |||||

| Graduate students in our program are trained in utilizing the DSM-5 cultural formulation interview or other instrument to assess cultural factors affecting the clinical encounter (e.g., racial identity, experiences of racial discrimination, cultural factors affecting help seeking). a (n=198) |

65% |

41.18% |

58.33% |

50.41% |

χ2 = 2.66, p = 0.45 |

| Training in Addressing Racism-Related Stress | |||||

| I am satisfied with the clinical training in treating racial trauma or addressing racial discrimination offered by my program.b,c (n=155) | 2.10 (1.55) | 1.71 (1.20) | 1.88 (1.27) | 2.03 (1.23) | F (3,151) = 0.34, p = 0.80 |

| Trainee Cultural Skills and Practices | |||||

| When working with BIPOC clients, I assess individual strengths and resources such as resilience, self-efficacy, spirituality, faith, and religious values. c,d (n = 132) | 1.56 (0.62) | 2.14 (0.77) | 1.53 (0.72) | 1.63 (0.82) | F (3,128) = 2.11 p = .10 |

| When working with BIPOC clients, I assess factors related to racial microaggressions, racial discrimination, racial profiling, and racism, as potential factors triggering, precipitating or sustaining mental health problems. c,d (n = 132) | 1.89 (0.96) | 2.71 (1.07) | 2.12 (1.05) | 2.49 (1.02) | F (3,128) = 2.61 p = .05 |

| PROGRAM ASSESSMENT OF CULTURAL HUMILITY | |||||

| Trainee progress towards cultural humility or multicultural competence is regularly assessed in my program. b (n = 223) | 2.41 (1.33) | 2.92 (1.60) | 2.81 (1.64) | 2.81 (1.64) | F (3,219) = 2.07 p = .12 |

| In-house supervisor progress towards cultural humility or multicultural competence is regularly assessed in my program.b (n = 223) | 1.82 (0.39) | 1.95 (0.23) | 1.78 (0.42) | 1.83 (0.38) | F (3,221) = 0.80 p = .50 |

Note. M = Mean. SD = standard deviation.

Responses were coded as yes versus no.

Responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

This question was only asked of graduate students.

Responses ranged from 1 (always) to 5 (never).

As we have done in prior work (see Galán et al., preprint; Galán, Stokes, et al., 2021), due to limited representation of certain races in the sample, we created a five-category race/ethnicity variable for subgroup analyses, which involved categories of: (1) Non-Hispanic White; (2) Non-Hispanic Black; (3) Non-Hispanic Asian or Pacific Islander; (4) Hispanic/Latinx; and (5) Multiracial/Other. Participants in the first three categories answered affirmatively to White, Black/African American, or Asian/Pacific Islander, respectively, and “no” to all other races. Any participants who identified as Hispanic/Latinx were categorized in the Hispanic/Latinx category, regardless of the race they endorsed (Galán, Stokes, et al., 2021). Participants who selected more than one race (and did not endorse Hispanic/Latinx) were categorized as Multiracial, and Other refers to participants who self-identified as American Indian, Alaska Native, Middle Eastern, North African, or Other (and did not endorse Hispanic/Latinx). Analyses assessing subgroup differences based on race excluded participants in the Multiracial/Other group, given the significant heterogeneity in the racial identity of participants in this category and the small sample size of each race comprising the Multiracial/Other category (i.e., each less than 1%).

To assess differences in responses based on participant position in program and race, one-way ANOVAs were computed for continuous variables and Pearson’s chi-square tests for binary variables. Significant omnibus tests were followed by post-hoc pairwise comparisons to determine which racial groups significantly differed from each other. As we had substantially fewer faculty, DCTs, and clinical supervisors who participated in our study compared to the number of graduate students, individuals in these groups were collapsed into a single category to maximize power. Thus, subgroup analyses based on position in the program examined differences in perception between graduate students and faculty, clinical supervisors, and DCTs. Pairwise contrasts were not required for position subgroup analyses as these models only entailed two groups. The p value was set at <.05 for all analyses. Analyses were conducted in SPSS 27.0 (IBM Corp, 2017).

Results

Cultural Humility Training Broadly (Tables 2–3)

Table 3.

Cultural humility training broadly, cultural knowledge training, and cultural skills training: Differences in perception by participants’ race

| Items | Asian (1) M (SD) or % “Yes” |

Black (2) M (SD) or % “Yes” |

Latinx (3) M (SD) or % “Yes” |

White (4) M (SD) or % “Yes” |

ANOVA or Chi-Square Test (χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CULTURAL HUMILITY TRAINING BROADLY | |||||

|

| |||||

| Cultural Humility Training Activities | |||||

|

| |||||

| As part of clinical training, my program offers the following cultural humility | |||||

|

| |||||

| Multiculturalism orientation | 38.10% | 47.37% | 34.62% | 56.67% | χ2 = 6.21, p = 0.10 |

|

| |||||

| Cultural plunge/Cultural immersion | 14.29% | 15.79% | 16.00% | 10.88% | χ2 = 3.72, p = 0.29 |

|

| |||||

| Multicultural case conference | 19.05% | 36.84% | 30.77% | 33.11% | χ2 = 1.93, p = 0.59 |

|

| |||||

| Didactics or workshops on cultural humility | 33.33% | 52.94% | 43.48% | 53.52% | χ2 = 3.48, p = 0.32 |

|

| |||||

| Perception of Cultural Humility Training | |||||

|

| |||||

| My program provides graduate students with up-to-date and empirically based training in cultural humility.b (n=194) | 2.59 (1.53) 1 < 4 | 3.11 (1.60) | 2.82 (1.62) | 3.52 (1.51) 4 > 1 | F (3,190) = 3.24, p <.05 |

|

| |||||

|

| |||||

| CULTURAL KNOWLEDGE TRAINING | |||||

|

| |||||

| Coursework | |||||

|

| |||||

| Diversity issues are infused throughout graduate courses rather than being isolated to a single lecture or course. b (n = 272) | 2.42 (1.41)1 < 4 | 3.16 (1.75)2 < 4 | 3.26 (1.63)3 < 4 | 4.03 (1.36)4 > 1,2,3 | F (3,268) =11.97, p <.001 |

| Does your program offer at least one graduate course focused on racial and social justice issues as they relate to clinical practice and clinical science? a (n = 278) | 75.00% | 61.54% | 87.10% | 76.65% | χ2 = 5.16, p = 0.16 |

|

| |||||

| CULTURAL SELF-AWARENESS TRAINING | |||||

|

| |||||

| Clinical Supervisor Discussion of Cultural Identities | |||||

|

| |||||

| Clinical supervisors regularly discuss trainee cultural identities during supervision. b (n=180) | 2.43 (1.60) | 2.94 (1.69) | 3.00 (1.75) | 3.12 (1.52) | F (3,176) = 1.18 p = 0.32 |

| Clinical supervisors regularly discuss client cultural identities during supervision. b (n=181) | 2.81 (1.69) 1 < 2,3,4 | 4.00 (1.66) 2 < 1 | 3.80 (1.51) 3 < 4; 3 > 1 | 4.50 (1.31) 4 > 1,3 | F (3,177) = 9.21 p <.001 |

|

| |||||

| Reflective Training Exercises | |||||

|

| |||||

| Cultural genogram exercise a (n=218) | 14.29% | 21.05% | 19.23% | 21.23% | χ2 = 0.57, p = 0.90 |

Note. M = Mean. SD = standard deviation. Superscript numbers denote significant differences in mean scores between classes based on Least Significant Difference post-hoc comparisons, ps < .05.

Responses were coded as yes versus no.

Responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

We first sought to assess perceptions of clinical psychology programs’ efforts to provide graduate students with training in cultural humility and to explore differences in these perceptions based on respondent race. See Tables 2–3 for descriptive statistics and subgroup analysis results.

Cultural Humility Training Activities.

We assessed whether programs provided a variety of cultural humility training exercises, including a multiculturalism orientation, cultural plunge/cultural immersion, multicultural case conference, or didactics/workshops on cultural humility. While approximately half of participants indicated that their program has hosted a multiculturalism orientation (51.50%) or didactics/workshops on cultural humility (50.45%), other trainings such as the cultural plunge/cultural immersion (10.85%) were less common. When examining differences based on participants’ position in the program, compared to graduate students, a greater percentage of clinical supervisors and DCTs reported that their program offers these types of training, with the exception of the cultural plunge/cultural immersion exercise which received low rates of endorsement among respondents across all positions. Asian, Black, Latinx, and White participants did not significantly differ from one another in their perceptions of the availability of these trainings.

Perception of Cultural Humility Training.

Next, we assessed perceptions of the quality of clinical training received. Half of participants (50%) disagreed that graduate students are provided with up-to-date and empirically based training in cultural humility. Asian participants and graduate students reported significantly less agreement with this statement than did White participants and clinical supervisors and DCTs, respectively.

Cultural Knowledge Training (Tables 2–3)

Coursework.

Most participants (76%) indicated that their program offers at least one graduate course focused on racial and social justice issues. However, approximately two thirds of participants (64%) disagreed (i.e., endorsed slightly disagree, mostly disagree, or strongly disagree) that issues pertaining to DEI are infused throughout graduate courses rather than being isolated to a single lecture or course. Compared to faculty, clinical supervisors, and DCTs, graduate students were significantly less likely to report that their program offers a graduate course on racial and social justice issues and less likely to perceive that diversity issues are infused throughout graduate courses (see Table 2). Further, when examining differences in perceptions based on participant race, Asian, Black, and Latinx participants were significantly less likely to agree that diversity topics are embedded in the curriculum compared to White participants (see Table 3).

Cultural Self-Awareness Training (Tables 2–3)

Clinical Supervisor Discussion of Cultural Identities.

Turning to questions about cultural self-awareness training, 57.78% of participants disagreed (i.e., endorsed slightly disagree, mostly disagree, or strongly disagree) that in-house clinical supervisors regularly discuss trainees’ cultural identities during clinical supervision; there were no differences in these reports based on participant race. About a quarter (23.76%) of participants disagreed that clinical supervisors regularly discuss clients’ cultural identities during clinical supervision, whereas half (49.72%) strongly agreed or mostly agreed with this statement. Compared to graduate students, in-house clinical supervisors and DCTs more strongly agreed that clinical supervisors in their program regularly discuss trainees’ and clients’ cultural identities during supervision (see Table 2). When examining differences in perceptions based on respondent race, White participants were more likely than Asian and Latinx participants to agree that clinical supervisors discuss clients’ cultural identities during clinical supervision (see Table 3).

Reflective Training Exercises.

Less than a quarter of participants (21.40%) indicated that their program engages students in a cultural genogram activity. When examining differences based on participants’ position in the program, compared to graduate students (16.93%), a greater percentage of clinical supervisors and DCTs (42.50%) reported that their program offers this type of training (see Table 2). Asian, Black, Latinx, and White participants did not significantly differ from one another in their perceptions of the availability of these trainings (see Table 3).

Cultural Skills Training and Practices (Tables 4–5)

Table 4.

Cultural skills training and practices and program assessment of cultural humility: Differences in perception by participants’ position in program

| Items | Total M (SD) or % “Yes” |

Graduate Students M (SD) or “Yes” |

Faculty, Supervisors, and/or Directors of Clinical Training M (SD) or % “Yes” |

ANOVA or Chi-Square Test (χ2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CULTURAL SKILLS TRAINING AND PRACTICES | ||||

| Training in Assessment Tools | ||||

| Graduate students in our program are trained in utilizing the DSM-5 cultural formulation interview or other instrument to assess cultural factors affecting the clinical encounter (e.g., racial identity, experiences of racial discrimination, cultural factors affecting help seeking). a (n=198) |

52.02% |

51.61% |

53.49% |

χ2 = 0.05, p = 0.83 |

| Training in Addressing Racism-Related Stress | ||||

| I am satisfied with the clinical training in treating racial trauma or addressing racial discrimination offered by my program.b,c (n=168) | N/A | 2.04 (1.29) | N/A | N/A |

| Trainee Cultural Skills and Practices | ||||

| When working with BIPOC clients, I assess individual strengths and resources such as resilience, self-efficacy, spirituality, faith, and religious values. c,d (n = 143) | N/A | 1.65 (0.79) | N/A | N/A |

| When working with BIPOC clients, I assess factors related to racial microaggressions, racial discrimination, racial profiling, and racism, as potential factors triggering, precipitating or sustaining mental health problems. c,d (n = 148) | N/A | 2.39 (1.06) | N/A | N/A |

| PROGRAM ASSESSMENT OF CULTURAL HUMILITY | ||||

| Trainee progress towards cultural humility or multicultural competence is regularly assessed in my program. b (n = 240) | 3.06 (1.54) | 2.87 (1.55) | 3.78 (1.30) | F(1,238)=13.25 p <.001 |

| In-house supervisor progress towards cultural humility or multicultural competence is regularly assessed in my program. b (n = 240) | 1.83 (0.38) | 1.82 (0.39) | 1.88 (0.33) | F(1,238)=10.00 p = .40 |

Note. M = Mean. SD = standard deviation.

Responses were coded as yes versus no.

Responses ranged from 1 (strongly disagree) to 6 (strongly agree).

This question was only asked of graduate students.

Responses ranged from 1 (always) to 5 (never).

Training in Assessment Tools.

Approximately half of participants (52.02%) indicated that graduate students in their program are trained in utilizing the DSM-5 cultural formulation interview or another instrument to assess cultural factors affecting the clinical encounter (e.g., racial identity, experiences of racial discrimination, cultural factors affecting help seeking). There were no differences based on participants’ position or participants’ race in perceived training in the use of the cultural formulation interview or related instruments.

Training in Addressing Racism-Related Stress.

Graduate students (but not faculty or clinical supervisors) also reported on the extent to which they are satisfied with the clinical training in treating racial trauma or addressing racial discrimination offered by their program. The majority of graduate students (87.74%) disagreed that they are satisfied with such training (i.e., endorsed slightly disagree, mostly disagree, or strongly disagree) (see Table 4). There were no significant differences on this variable based on participant race (see Table 5).

Trainee Cultural Skills and Practices.

Next, we sought to assessed cultural skills and practices among graduate students in clinical psychology programs. The majority of graduate students indicated that they frequently assess individual strengths and resources such as resilience, faith, and religious values when working with Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) (85.61% endorsed “always” or “often”). Over half of graduate students indicated that when working with BIPOC clients, they frequently assess experiences of racism and racial discrimination as potential factors triggering, precipitating or sustaining mental health problems (58.33% endorsed “always” or “often”). Black graduate students indicated engaging in these practices most frequently, but one-way ANOVAs comparing responses based on respondent race did not reach statistical significance (see Table 5).

Program Assessment of Cultural Humility (Tables 4–5)

For the final analyses, we assessed assessment of trainees’ and clinical supervisors’ cultural humility. Approximately half of participants (54.71%) disagreed that graduate students’ progress toward cultural humility or multicultural competence is regularly assessed in their program (i.e., endorsed slightly disagree, mostly disagree, or strongly disagree). Compared to clinical supervisors and DCTs, graduate students were significantly less likely to agree that trainee progress toward cultural humility is regularly assessed (see Table 4). All participants (100%) “strongly disagreed” or “mostly disagreed” that clinical supervisors’ progress toward cultural humility is regularly assessed. Asian, Black, Latinx, and White participants did not significantly differ from one another in their perceptions of the extent to which their program assesses cultural humility (see Table 5).

Discussion

Leveraging original data from an online national survey of graduate students, faculty, clinical supervisors, and Directors of Clinical Training (DCT) in clinical psychology PhD and PsyD programs, the present study took stock of clinical training initiatives in cultural humility and student self-perceived cultural humility and effectiveness in addressing racism-related stressors. Findings indicate that while the vast majority of graduate students (91.3%) are working with clients of color, most are likely doing so without adequate training in attending to the unique racial stressors that clients of color face and without adequate training in cultural humility. Further, there were significant differences based on participants’ position, such that faculty, clinical supervisors, and DCTs generally perceived their program to be more advanced in the provision of cultural humility training than did graduate students. These discrepancies in perceptions may be indicative of faculty and supervisors being more aware of the types of training offered at each stage in the graduate program, or alternatively, may reflect a blindspot of those in power. We refer readers to Galán, Bekele, et al. (2021) (pp. 23-25) for recommendations regarding approaches to cultural humility training.

Findings from the current study indicate that despite the importance of attending to clients’ experiences of racism, graduate students in clinical psychology programs receive limited training in how to broach topics of racism and address racism-related stress within the clinical context. A growing body of research suggests that clinicians’ explicit discussions of racial, ethnic, and cultural concerns in the lives and experiences of clients of color enhance therapist credibility, the depth of client disclosure, client willingness to return for follow-up sessions, and favorable client outcomes (Day-Vines et al., 2021; King, 2022; King & Borders, 2019). In contrast, clinicians’ failure to identify and address client racism-related stress and trauma has been linked to client dissatisfaction with therapy, ruptures in the working alliance, suppression of personal disclosures, premature departure from treatment, and decreased willingness to pursue mental health services in the future (Bartholomew et al., 2021; Yeo & Torres-Harding, 2021). Thus, our failure to provide graduate students with sufficient training in addressing racism-related stress and other racially-specific psychological and therapeutic concerns is likely to have significant downstream consequences in terms of maintaining and further magnifying racial disparities in the access, utilization, and quality of care for people of color.

An especially notable finding was that discussions of trainees’ cultural identities occurred less frequently during clinical supervision compared to discussions of clients’ identities, highlighting a significant gap in clinical training. Although consideration of clients’ identities is essential to providing culturally responsive care, focusing exclusively on clients’ identities without consideration of one’s own positionality is consistent with a cultural competence rather than a cultural humility stance. Trainings in cultural competence often focus on increasing knowledge about different racial groups, typically people of color. As little attention is paid to the therapist’s own identities, cultural competence approaches can have an “othering” effect where the implicit assumption is that clients who are not White are different and in need of greater understanding (Agner, 2020). Cultural humility, in contrast, encourages critical self-reflection and interrogation of our own values, beliefs, and social identities (e.g., race, ethnicity, class, gender) (Hook et al., 2017). Being a culturally humble clinician necessitates understanding how each of our identities is imbued with varying degrees of privilege, power, and oppression and how they inform what we attend to, what we overlook, the assumptions that we make about clients, the assumptions that they make about us, and other aspects of therapy (APA, 2017; Galán et al., 2022). Clinical supervisors have both the privilege and responsibility of fostering such self-reflection and cultural self-awareness among trainees; encouraging dialogue regarding trainees’ own cultural identities during supervision is one (although not the only way) in which to do so.

A particularly concerning finding was that 100% of participants (graduate students, clinical supervisors, and DCTs) disagreed that clinical supervisors’ progress towards cultural humility is assessed in their program. Programs’ failure to assess supervisors’ cultural humility may be contributing to blindspots in the amount and quality of cultural humility training that graduate students are receiving. Although supervisors play a central role in facilitating graduate students’ training in cultural humility, most graduate programs do not ensure that supervisors are actually qualified to provide such training. Monitoring cultural humility is critical for illuminating areas of growth for supervisors and ensuring that supervisors are equipped with the necessary awareness, knowledge, and skills to provide high-quality supervision experiences to trainees. Detailed recommendations for evaluating cultural humility among graduate students and clinical supervisors are provided by Galán, Bekele and colleagues (2021) (pp. 23-35).

The overall finding that BIPOC participants (regardless of position) were significantly less likely to agree that diversity topics were embedded in the graduate curriculum compared to White participants merits further investigation. It is possible that some people of color, as a result of their lived experiences, may be more knowledgeable of what it means to infuse DEI content throughout training rather isolating these issues to a single ‘diversity’ lecture or workshop in a superficial manner. Discrepancies between BIPOC and White participants may also be conflated with participant position in program as faculty, supervisors, and DCTs were disproportionately White whereas graduate students were more racially diverse. Unfortunately, due to the small sample size and limited participation of faculty, supervisors, and DCTs in our study, we were unable to disentangle the effects of race and position in program. Future research should prioritize more extensively examining faculty, supervisor, and DCT perceptions of DEI-related training as these individuals are typically responsible for the development and implementation of the training curriculum and experiences.

Limitations

Findings should be considered within the context of study limitations. First, it is possible that individuals who are committed to advancing diversity, equity, and inclusion may have self-selected into the study which may have impacted our results. Second, we did not collect reliable data on participants’ year in their training programs; though we asked participants to indicate the year they began their current program, less than half of participants elected to answer this question or provided usable data. Nonetheless, it is likely that some graduate student participants were in the first year of their training programs and may not yet have been exposed to the cultural humility training experiences assessed in our survey, which could have influenced findings. Third, due to the lack of validated measures for assessing cultural humility training in graduate programs, we developed our own survey items to assess constructs of interest. While the development of these items was informed by research on cultural humility and recent recommendations for advancing anti-racism in clinical psychology (Galán, Bekele, et al, 2021), the use of single items may have contributed to problems with multiple comparisons for subgroup analyses. Fourth, we relied solely on self-report which is vulnerable to social desirability bias. Concerns about appearing culturally incompetent may have led some respondents to overestimate the frequency with which they engage in certain behaviors (e.g., discussing trainees’ cultural identities clinical supervision). Fifth, we elected not to ask faculty, clinical supervisors, and DCTs questions about topics that they might not have first-hand experience with (e.g., satisfaction with the program’s training in treating racial trauma). However, having data on their opinions of these topics may have been informative as faculty/supervisor perceptions likely influence the nature and quality of training that students receive. Lastly, while participants spanned 112 clinical psychology programs in the United States, we did not have sufficient representation from each program to account for program-level clustering or to assess how specific programs are doing with respect to cultural humility training. We agree with recent calls to have the design and distribution of clinical science training surveys be coordinated across institutions and potentially integrated into accreditation-related data collection efforts (Gee et al., 2022). Assessments of cultural humility organized at the national level will help to mitigate concerns of self-selection biases that plague grassroots efforts (including the current survey) and provide the necessary data to begin moving towards an evidence-based approach to cultural humility training. Thus, we call upon accrediting bodies to administer similar training surveys as a way to evaluate progress towards cultural humility at the program-level which may help identify those programs’ strengths and weaknesses. It may be the case that some programs are doing particularly well at the practices outlined in the current manuscript and that engaging such efforts across programs could improve future training outcomes with respect to cultural humility.

Conclusion

To move towards antiracism in clinical psychology, we must identify concrete opportunities to change policies and behaviors that have historically perpetuated racism and racial inequities. One modifiable factor in clinical psychology graduate programs that has significant downstream effects on the development and maintenance of these racial inequities include current approaches to clinical training and supervision. Study findings highlight significant gaps between what trainees need to develop cultural humility and what they may actually be receiving from their respective programs. While findings suggest that there is still a lot of work to be done, understanding where we stand as a field with regards to cultural humility training is an important first step towards change.

We have an ethical imperative to ensure that the next generation of clinical psychologists are equipped with the knowledge, skills, and self-awareness to work with an increasingly racially and ethnically diverse population. Meeting this challenge will require an honest reckoning with the current state of clinical training in cultural humility (both in the field and in our specific programs) and an acknowledgement that providing a single course, hosting a few workshops, or completing a single self-reflective exercise will not be enough. Rather, we must embed cultural humility training throughout all aspects of our programs from beginning to end and continuously evaluate the impact of these efforts on both trainee and client outcomes. By restructuring current approaches to clinical training, we can advance an “upstream” prevention approach that helps to dismantle structural drivers of racial inequities in mental health outcomes.

Biographies

CHARDÉE A. GALÁN, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of Southern California (USC). She received her PhD in Clinical and Developmental Psychology from the University of Pittsburgh and completed her predoctoral clinical internship from Western Psychiatric Hospital/University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Her research and professional interests include risk and protective factors for psychopathology among racial-ethnic minority youth (e.g., racial-ethnic discrimination, racial-ethnic socialization); culturally responsive assessments and interventions for racial-ethnic minority youth and families; and targeting institutional and structural drivers of racial/ethnic disparities in youth mental health outcomes and care.

CASSANDRA L. BONESS, PhD, is a Licensed Clinical Psychologist in the state of New Mexico and a Research Assistant Professor at the University of New Mexico Center on Alcohol, Substance use, And Addictions (CASAA). She received her doctorate from the University of Missouri and completed a clinical internship at Western Psychiatric Hospital/University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Her research and professional interests include addiction mechanisms and precision medicine; measurement, assessment, and classification; and stigma and harm reduction.

IRENE TUNG, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Psychology at California State University, Dominguez Hills and a Licensed Clinical Psychologist. She received her PhD in clinical psychology from the University of California, Los Angeles and completed a predoctoral clinical internship at Western Psychiatric Hospital/University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Her research and professional interests include developmental psychopathology, prenatal and early life stress, resilience and prevention, and mentorship and training in health service psychology.

MOLLY A. BOWDRING, PhD, is a postdoctoral scholar affiliated with the Stanford Prevention Research Center and Department of Psychiatry at Stanford University. She completed her doctorate in Clinical and Biological Health Psychology at the University of Pittsburgh and completed her predoctoral internship at the VA Palo Alto Healthcare System. Her professional interests include the psychosocial sequelae of addictive behaviors, evidence-informed interventions for addiction and comorbid psychopathology, and clinical psychology training.

CHRISTINE C. CALL, PhD, is a postdoctoral fellow in the NIMH-funded Clinical Research Training Program for Psychologists (T32 MH018269) in the Department of Psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh. She received her doctorate from Drexel University and completed a clinical internship at Western Psychiatric Hospital/University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Her research and professional interests include intervention development for problems related to eating and weight; food insecurity and its relation to eating behaviors and weight change; perinatal behavioral health; and promoting equity in clinical science.

SHANNON M. SAVELL, MA, is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Psychology at the University of Virginia. Her research and professional interests include developing and examining culturally responsive, evidence-based intervention strategies within family systems to address mental health concerns for caregivers and children.

JESSIE B. NORTHRUP, PhD, is an Assistant Professor of Psychiatry at the University of Pittsburgh. She received her PhD in clinical and developmental psychology at the University of Pittsburgh and completed a predoctoral internship at Western Psychiatric Hospital/University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Her research and professional interests include understanding parent-child interactions as a context for early social and emotional development in young autistic children, interventions to improve quality of life for autistic individuals and their families, neurodiversity advocacy, and research mentorship.

STEFANIE L. SEQUEIRA, MS, is a doctoral candidate in the Department of Psychology at the University of Pittsburgh and a current predoctoral intern at the Alpert Medical School of Brown University. Her research and professional interests include understanding interactions between peer experiences and brain development during adolescence, identifying novel intervention targets for youth with anxiety disorders, and providing clinical and research mentorship in clinical and developmental psychology.

Footnotes

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

References

- Agner J (2020). Moving from cultural competence to cultural humility in occupational therapy: A paradigm shift. The American Journal of Occupational Therapy, 74(4), 7404347010p1 7404347010p7. 10.5014/ajot.2020.038067 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association. (2017). Multicultural guidelines: An ecological approach to context, identity, and intersectionality. Retrieved May 21, 2022, from http://www.apa.org/about/policy/multiculturalguidelines.pdf

- Bartholomew TT, Pérez-Rojas AE, Lockard AJ, Joy EE, Robbins KA, Kang E, & Maldonado-Aguiñiga S (2021). Therapists’ cultural comfort and clients’ distress: An initial exploration. Psychotherapy, 58(2), 275. 10.1037/pst0000331 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buchanan NT, Perez M, Prinstein MJ, & Thurston IB (2021). Upending racism in psychological science: Strategies to change how science is conducted, reported, reviewed, and disseminated. American Psychologist, 76(7), 1097–1112. 10.1037/amp0000905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook BL, Trinh NH, Li Z, Hou SSY, & Progovac AM (2017). Trends in racial-ethnic disparities in access to mental health care, 2004–2012. Psychiatric Services, 68(1), 9–16. 10.1176/appi.ps.201500453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Day-Vines NL, Cluxton-Keller F, Agorsor C, & Gubara S (2021). Strategies for broaching the subjects of race, ethnicity, and culture. Journal of Counseling & Development, 99(3), 348–357. 10.1002/jcad.12380 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diala C, Muntaner C, Walrath C, Nickerson KJ, LaVeist TA, & Leaf PJ (2000). Racial differences in attitudes toward professional mental health care and in the use of services. American Journal of Orthopsychiatry, 70(4), 455– 464. 10.1037/h0087736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fowers BJ, & Davidov BJ (2006). The virtue of multiculturalism: Personal transformation, character, and openness to the other. American Psychologist, 61(6), 581–594. 10.1037/0003-066X.61.6.581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galán CA, Bekele B, Boness C, Bowdring M, Call C, Hails K, McPhee J, Hawkins Mendes S, Moses J, Northrup J, Rupert P, Savell S, Sequeria S, Tervo-Clemmens B, Tung I, Vanwoerden S, Womack S, & Yilmaz B (2021). A call to action for an antiracist clinical science. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 50(1), 12–57. 10.1080/15374416.2020.1860066 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galán CA, Bowdring MA, Sequeira S, Tung I, Call CC, Savell S, Boness CL, & Northrup JB (Preprint). Real change or performative anti-racism? Differing perceptions of clinical psychology doctoral programs’ efforts to recruit and retain faculty and graduate students of color. https://osf.io/h2nbx/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Galán CA, Stokes LR, Szoko N, Abebe KZ, & Culyba AJ (2021). Exploration of experiences and perpetration of identity-based bullying among adolescents by race/ethnicity and other marginalized identities. JAMA Network Open, 4(7), e2116364–e2116364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galán CA, Tung I, Tabachnick A, Sequeira S, Novacek DM, Kahhale I, … Bekele B (2022). Combatting the conspiracy of silence: Clinician recommendations for talking about racism and racism-related events with youth of color. Journal of American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, S0890–8567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gee DG, DeYoung KA, McLaughlin KA, Tillman RM, Barch DM, Forbes EE, … & Shackman AJ (2022). Training the next generation of clinical psychological scientists: A data-driven call to action. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 18, 43–70. 10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-081219-092500 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook JN, Farrell JE, Davis DE, DeBlaere C, Van Tongeren DR, & Utsey SO (2016). Cultural humility and racial microaggressions in counseling. Journal Of Counseling Psychology, 63(3), 269–277. 10.1037/cou0000114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hook JN, Davis D, Owen J, & DeBlaere C (2017). Cultural humility: Engaging diverse identities in therapy. American Psychological Association. 10.1037/0000037-000 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hook JN, Davis DE, Owen J, Worthington EL Jr., & Utsey SO (2013). Cultural humility: Measuring openness to culturally diverse clients. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 60(3), 353–366. 10.1037/a0032595 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King KM (2022). Client perspectives on broaching intersectionality in counseling. The Journal of Humanistic Counseling, 61(1), 30–42. 10.1002/johc.12169 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- King KM, & Borders LD (2019). An experimental investigation of white counselors broaching race and racism. Journal of Counseling & Development, 97(4), 341–351. 10.1002/jcad.12283 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mills S, Xiao AQ, Wolitzky-Taylor K, Lim R, & Lu FG (2017). Training on the DSM-5 Cultural Formulation Interview improves cultural competence in general psychiatry residents: A pilot study. Transcultural Psychiatry, 54(2), 179–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mills S, Wolitzky-Taylor K, Xiao AQ, Bourque MC, Rojas SMP, Bhattacharya D, … & Lu FG (2016). Training on the DSM-5 cultural formulation interview improves cultural competence in general psychiatry residents: A multi-site study. Academic Psychiatry, 40(5), 829–834. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owen J, Tao KW, Imel ZE, Wampold BE, & Rodolfa E (2014). Addressing racial and ethnic microaggressions in therapy. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 45(4), 283–290. 10.1037/a0037420 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Psychological Clinical Science Accreditation System (PCSAS) (2022). Psychological Clinical Science Accreditation System (PCSAS): Purpose, Organization, Policies, and Procedures. https://www.pcsas.org/redesign/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/PCSAS-POPP-Manual-rev-Mar-2022.pdf

- Sandeen E, Moore KM, & Swanda RM (2018). Reflective local practice: A pragmatic framework for improving culturally competent practice in psychology. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 49(2), 142–150. 10.1037/pro0000183 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW (2001). Multidimensional facets of cultural competence. The Counseling Psychologist, 29(6), 790–821. 10.1177/0011000001296002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, Capodilupo CM, Torino GC, Bucceri JM, Holder AMB, Nadal KL, & Esquilin M (2007). Racial microaggressions in everyday life: Implications for clinical practice. American Psychologist, 62(4), 271–286. 10.1037/0003-066X.62.4.271 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sue DW, & Torino GC (2005). Racial-cultural competence: Awareness, knowledge, and skills. In Carter RE (Ed.), Handbook of Racial-Cultural Psychology and Counseling, Volume 2. (pp. 3–18). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Tervalon M, & Murray-Garcia J (1998). Cultural humility versus cultural competence: A critical distinction in defining physician training outcomes in multicultural education. Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved, 9(2), 117–125. 10.1353/hpu.2010.0233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeo E, & Torres-Harding SR (2021). Rupture resolution strategies and the impact of rupture on the working alliance after racial microaggressions in therapy. Psychotherapy, 58(4), 460–471. 10.1037/pst0000372 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]