Abstract

Applied behavior analysis (ABA) is the application of behavioral principles to affect socially important behavior change with social importance, or social validity, being defined by the consumers of the intervention. (Schwartz & Baer, Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis 24, 189–204, 1991) provided several suggestions to improve the implementation of the social validity assessment including engaging in ongoing assessment, increasing the type and psychometric rigor of social validity measures, and extending participation in the social validity assessment to include direct and indirect consumers. The purpose of this article is to explore the current implementation of social validity assessments used in behavioral research. This article also explores key demographics among consumers with disabilities and/or mental health disorders who are included and excluded from social validity assessments. The most common social validity assessment source was author-created and implemented at a single time point. In addition, consumers with disabilities were often excluded from the social validity assessments. The implications of the social validity assessment implementation and consumer exclusion are discussed.

Keywords: Direct consumers, Social importance, Social validity assessment, Social validity

Applied behavior analysis (ABA) is the application of behavioral principles to affect socially important behavior change, with social importance being defined by the consumers of the intervention (Schwartz & Kelly, 2021; Wolf, 1978). Consumers are defined as those who receive the intervention (i.e., direct consumers), those who are significantly affected by the intervention such as parents (i.e., indirect consumers), and members of the immediate and extended community (Schwartz & Baer, 1991). The formal evaluation of social importance, the social validity assessment, was initially introduced as a means for behavior analysis to “find its heart” by gathering information related to consumer experience and then applying that information to improve practice (Wolf, 1978). Social importance is a core dimension of ABA and applies to the selection of meaningful target behaviors, the implementation of acceptable behavioral strategies, and overall satisfaction with intervention effectiveness (Baer et al., 1968; Wolf, 1978). Baer et al. (1987) urged behavior analysts to engage in active assessment of social validity to improve intervention and to address consumer disapproval that can result in an array of undesired responses (e.g., failure to implement).

Several reviews limited to publications in ABA-specific outlets have examined the use and implementation of social validity assessments (Carr et al., 1999; Ferguson et al., 2019; Huntington et al., 2023; Kennedy, 1992). Kennedy (1992) reviewed articles published in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis (JABA) and Behavior Modification (BMO) from 1977 to 1990 and found that 20% of articles included a social validity assessment, with most utilizing subjective measures and conducted after the intervention. Kennedy (1992) also found that if a preassessment was conducted, it assessed the goals of the intervention with postassessments most commonly examining procedures and outcomes. Kennedy (1992) recommended that guidelines be established for behavioral research as to when social validity assessments are required and that those guidelines should be applied to publication. Kennedy (1992) also suggested that social validity research should focus on increasing the number and type of measures that are available to researchers with the goal of improving applicability to varied contexts.

Carr et al. (1999) reviewed social validity assessments used in articles published in JABA from its founding in 1968 to 1998. Carr et al. (1999) found that 13% of articles included a “formal” social validity assessment or “any systematic attempt to collect data on treatment outcome or acceptability” (Carr et al., 1999, p. 225). Carr et al. (1999) also found that social validity assessments were more likely to be conducted in studies occurring in natural settings as opposed to contrived or research-based settings. Like Kennedy (1992), Carr et al. (1999) recommended that guidelines for including social validity assessments in published behavioral literature be established. Carr et al. (1999) also contended that more valid measures need to be developed to ensure that what is being measured, is what is intended to be measured (i.e., content validity) and that the measures themselves can be trusted (i.e., psychometric rigor)

Ferguson et al. (2019) conducted a follow-up review in JABA, and included articles published from 1999 to 2016. Ferguson et al. (2019) found that 12% of articles included a social validity assessment, most utilizing rating scales and questionnaires to measure social validity. In addition, Ferguson et al. (2019) found that social validity assessments focused on the social importance of the procedures with few focusing on the goals of the intervention. Ferguson et al. (2019) called for an increase in social validity assessments across behavioral literature, echoing previous reviews (Carr et al., 1999; Kennedy, 1992). Ferguson et al. (2019) also recommend that the type of consumer who is participating in the social validity assessments should be expanded.

The most recent review of social validity assessment from Huntington et al. (2023) examined intervention articles across eight prominent behavioral journals from 2010 to 2020. Huntington et al. (2023) found that social validity assessments were included in 47% of articles, an increase from previous reviews with a notable rise from 2018 to 2020. Huntington et al. (2023) also found that the terminology used to describe social validity assessments was inconsistent across the literature, making systematic and comprehensive reviews of this construct difficult. Huntington et al. (2023) recommended future researchers use the term “social validity” as outlined originally by Wolf (1978) to describe these assessment types in the future. Huntington et al. (2023) also called for journal editors to require the inclusion of social validity assessments in articles published in behavioral literature.

These previous reviews highlight recommendations to improve the future implementation of social validity assessments. Recommendations in many of these reviews mirror those made in publications preceding them. In their seminal article, Schwartz and Baer (1991) posited that current social validity assessments may be deviating from the original purpose (i.e., preventing consequences of social invalidity). To address this deviation, Schwartz and Baer recommended that the assessment of social validity be an iterative ongoing process, that measurement tools increase in variety and psychometric rigor, and that members of all consumer types be included. Fawcett (1991) also proposed that consumers be more actively involved in intervention (i.e., goal selection) and that an increased variety of consumer experts be included to evaluate social validity.

Other reviews on social validity that examine broader bodies of intervention literature also indicate that recommendations for improved social validity measurement have not been fully realized. For example, Ledford et al. (2016) reviewed articles published from 1994 to 2013 in which participants were young children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD). Ledford et al. (2016) found that the type of social validity measures being used is narrowing, rather than expanding, with most articles relying on similar subjective measures (e.g., checklists, interviews) with the source not identified. In addition, it is well-documented in previous reviews of the literature that social validity assessments are not being conducted on an ongoing basis, and most often are conducted after the intervention has concluded (D’Agostino et al., 2019; Ferguson et al., 2019; Kennedy, 1992; Ledford et al., 2016; Park & Blair, 2019; Snodgrass et al., 2018).

Despite calls for expanding consumers participating in social validity assessment (e.g., Ferguson et al., 2019; Schwartz & Baer, 1991), few reviews have explored the types of consumers (e.g., direct, indirect) participating in social validity assessments and none have examined demographic variables in-depth. Park and Blair (2019) reviewed single-case research articles on early childhood behavior interventions published between 2001 and 2018. Park and Blair (2019) found that most articles included the direct consumer, defined as the interventionist, in the social validity assessment. Snodgrass et al. (2018) likewise categorized direct consumers as those who were the intended implementer or receiver of the intervention and found that these consumers were most often included in social validity assessments. Given that Schwartz and Baer (1991) originally defined a direct consumer as the “primary recipients of the program intervention” (p. 193), these reviews do not provide a clear picture of whether the type of consumer participating in social validity assessments is expanding. Without the perspectives of the direct consumer, as defined by Schwartz and Baer (1991), the social validity of an intervention may be called into question even with positive responses from indirect consumers or other community members. When behavior analysts fail to engage in a thorough investigation of direct consumer experiences through rigorous and appropriate social validity measurement, their ability to implement high-quality, effective, and long-lasting intervention is limited (Baer et al., 1987; Schwartz & Baer, 1991; Fawcett, 1991). In addition, Schwartz and Kelly (2021) suggest that direct consumers may be the “only” ones who can define social importance for themselves.

Reviews within behavioral journals (e.g., Carr et al., 1999; Ferguson et al., 2019; Huntington et al., 2023; Kennedy, 1992) and in related fields (e.g., D’Agostino et al., 2019; Ledford et al., 2016; Park & Blair, 2019; Snodgrass et al., 2018), have offered similar recommendations to improve implementation of social validity measurement that Schwartz and Baer (1991) provided in their original commentary. However, even with the development of a published manual on social validity assessment that provides explicit detail on improving the social significance of intervention goals, increasing the acceptability of intervention procedures, and enhancing the meaningfulness and satisfaction of intervention effects (Carter & Wheeler, 2019), it remains unclear if these recommendations are being followed in the current measurement of social validity. The purpose of this review was to examine the implementation of social validity assessments across behavior journals and assess the status of recommended practice. In particular, the source of social validity measures, engagement in continuous measurement of social validity, and inclusion of direct consumers with disabilities and/or mental health (MH) disorders as respondents was explored. The following questions guided this exploration:

What is the source of the social validity assessment measures used in the behavioral intervention literature?

When are social validity assessments being conducted relative to the intervention in behavioral intervention literature?

What are the demographic characteristics of direct consumers that are included and excluded from social validity assessments?

How often do social validity assessments include the perspectives of direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders?

Method

The data set used in this article is part of a larger selective review of behavioral research in which publication patterns related to social validity (i.e., frequency and terminology used to describe assessment) in articles published in eight behavioral journals between 2010 and 2020 (Huntington et al., 2023) were identified. Details on the methods of the initial search, including identification of journals for inclusion, and findings are available in Huntington et al. (2023). The full data set included 425 articles that were reviewed in initial coding. A subset of 236 articles that included at least one direct consumer of the intervention with a disability and/or MH disorder were reviewed in second round coding.

Initial Coding

Working from the full data set (n = 425), the full texts of articles were reviewed, and the source of the measure and the timing of the social validity assessment relative to the intervention were coded. During this initial coding, articles in which direct consumers of the intervention included at least one individual with a disability and/or MH disorder were also identified. This initial round of coding was completed by two doctoral-level behavior analysts, one behavior analyst with a PhD, and one graduate student studying ABA. All coders participated in training consisting of coding the same five articles independently and meeting to discuss all disagreements until an agreement was reached for each article. Following training, coders reviewed all articles in the full data set (n = 425) and 33% (n = 139) of articles were double coded for interrater reliability (IRR). IRR for all codes combined in initial coding was calculated by dividing the total number of disagreements by the total number of agreements and disagreements, resulting in 96% reliability with a range of 93%–100% across individual item codes. IRR was similarly calculated for each individual item code resulting in 97% reliability for social validity assessment source, 94% reliability for social validity assessment timing, and 97% reliability for direct consumers of the intervention with a disability and/or MH disorder.

Social Validity Assessment Source

Coders recorded “author-created” if the author noted that the social validity measure was created by the authors or if no information was provided related to the source of the social validity measure. Coders recorded “author-adapted” if the authors cited the use of an established social validity measure and stated that an adaptation was made. Coders recorded “established measure” if the authors cited a previously utilized social validity measure developed in previous research.

Social Validity Assessment Timing

Coders recorded whether authors reported the social validity assessment occurring before, during, and/or after the intervention. Multiple time points were recorded as described. If authors did not explicitly state the timing of the social validity assessment, coders recorded “not stated.”

Direct Consumers of the Intervention with a Disability and/or MH Disorder

Coders recorded “yes” if at least one of the consumers listed in the method had a stated disability and/or MH disorder. If the article did, these articles were included in the second round of analysis.

Second Round Coding

In second round coding, the full texts of the subset of articles that included at least one direct consumer of the intervention with a disability and/or MH disorder (n = 236) were reviewed. Reviewers coded demographic information of direct consumers of the intervention and whether direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders were included or excluded from participation in the social validity assessment. Second round coding was completed by three doctoral-level behavior analysts, one behavior analyst with a PhD, two master’s-level behavior analysts, two graduate students studying ABA, and one bachelor’s-level research associate. All coders participated in training that consisted of independently coding one article from each included journal and meeting to discuss disagreements until a consensus was reached. Following training, coders independently reviewed the subset of 236 articles with 32% (n = 76) of articles double-coded for IRR. The IRR for all codes combined in second round coding was calculated by dividing the total agreements by total agreements plus disagreements, resulting in a total agreement of 94% with a range of 91%–100% agreement across individual item codes. IRR was similarly calculated for each individual item code resulting in 92% reliability for whether all, some, or none of the direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders were included in the social validity assessment by article; 92% reliability for age, 91% reliability for sex, 92% reliability for gender, 99% reliability for ethnicity, 93% reliability for race, 100% reliability for IQ, 92% reliability for communication delays, and 97% reliability for disability and disorder type.

Demographics of Direct Consumers

Coders recorded whether all, some, or none of the direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders were included in the social validity assessment by article. Coders also recorded direct consumers' age, sex, gender, ethnicity, and raced. Demographics were recorded as reported by authors (e.g., if the author wrote “boy,” this was copied directly). Coders also recorded direct consumer IQ scores as reported and whether the authors noted the presence of communication delays (i.e., concerns, disabilities, limitations) for each consumer. If articles did not report demographic information relevant to a specific category, it was coded as “not reported.” Coders also recorded consumer diagnoses as reported by authors. When the second round coding was complete, direct consumers were grouped into the following disability and disorder type categories: attention deficit disorder/attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADD/ADHD), disability and MH disorder or health condition (i.e., disability type with co-occurring MH disorder or health condition), intellectual and developmental disability (inclusive of ASD; IDD), language impairment, MH disorder(s) (i.e., one or more co-occurring MH disorders), multiple disabilities (i.e., two or more co-occurring disabilities, not including MH disorders), specific learning disability (SLD), and other (e.g., educational classification or others not directly listed in existing categories).

Results

The full data set (n = 425) was reviewed in relation to social validity assessment source, timing, and inclusion of at least one direct consumer of the intervention with a disability and/or MH disorder. Data was analyzed by article to identify differences and broken down by journal for informational purposes. The subset of articles (n = 236) was reviewed in relation to demographic data (e.g., communication delay, disability, and disorder type) to identify differences with some variables (i.e., age, gender, sex, race, ethnicity) broken down by journal for informational purposes.

Social Validity Assessment Source

Social validity assessment source data can be viewed in Table 1. Across the full data set of 425 articles, authors reported using author-created social validity measures in 73.18% (n = 311) of articles. Author-adapted measures were the second most common assessment source (13.65%, n = 58), followed by established measures (6.82%; n = 29). Multiple assessment sources were reported in 6.35% (n = 27) of included articles; author-created and author-adapted measures were used together in 4.23% (n = 18) of articles, established measures were used together with either author-adapted or author-created measures were reported in 1.41% (n = 6) of articles, and established measures in combination with author-created and author-adapted measures were reported in 0.71% (n = 3) of articles. Similar patterns were found across journals as seen in Table 1. Author-created measures were the most frequently reported social validity assessment source across all included journals.

Table 1.

Source and timing of social validity assessment

| Full Data Set | AVB | BAP | BAT/BARP | BI | BMO | JABA | TPR | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n = 425 | n = 8 | n = 65 | n = 18 | n = 89 | n = 80 | n = 148 | n = 17 | |||||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Assessment Source | ||||||||||||||||

| Author Created (AC) | 311 | 73.18 | 7 | 87.50 | 49 | 75.38 | 17 | 94.44 | 69 | 77.53 | 36 | 45.00 | 119 | 80.41 | 14 | 82.35 |

| Author Adapted (AA) | 58 | 13.65 | 1 | 12.50 | 10 | 15.38 | 0 | - | 9 | 10.11 | 20 | 25.00 | 18 | 12.16 | 0 | - |

| Established Measure (EM) | 29 | 6.82 | 0 | - | 2 | 3.08 | 6 | 4.05 | 5 | 5.62 | 14 | 17.50 | 6 | 4.05 | 1 | 5.88 |

| Multiple Sources | 27 | 6.35 | 0 | - | 4 | 6.15 | 0 | - | 6 | 6.74 | 10 | 12.50 | 5 | 3.38 | 2 | 11.76 |

| AC and AA | 18 | 4.23 | - | - | 4 | 6.15 | - | - | 5 | 5.62 | 3 | 3.75 | 4 | 2.70 | 2 | 11.76 |

| EM with AC or AA | 6 | 1.41 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 5 | 6.25 | 1 | 1.12 | - | - |

| EM with AC & AA | 3 | 0.71 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 1 | 1.12 | 2 | 2.50 | - | - | - | - |

| Assessment Timing | ||||||||||||||||

| Single Time Point | 277 | 65.18 | 3 | 37.50 | 40 | 61.54 | 13 | 72.22 | 48 | 53.93 | 57 | 71.25 | 104 | 70.27 | 12 | 70.59 |

| Before | 3 | 0.71 | - | - | 1 | 1.54 | - | - | 1 | 1.12 | 1 | 1.25 | - | - | - | - |

| During | 11 | 2.59 | - | - | - | - | - | - | 2 | 2.25 | 3 | 3.75 | 6 | 4.05 | - | - |

| After | 263 | 61.88 | 3 | 37.50 | 39 | 60.00 | 13 | 72.22 | 45 | 50.56 | 53 | 66.25 | 98 | 66.22 | 12 | 70.59 |

| Multiple Time Points | 35 | 8.24 | - | - | 2 | 3.08 | 2 | 11.11 | 11 | 12.36 | 8 | 10.00 | 10 | 6.76 | 2 | 11.76 |

| Before and After | 23 | 5.41 | - | - | 1 | 1.54 | 2 | 11.11 | 9 | 10.11 | 3 | 3.75 | 7 | 4.73 | 1 | 5.89 |

| During and After | 6 | 1.41 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | 4 | 5.00 | 1 | 0.68 | - | - |

| Before, During, and After | 6 | 1.41 | - | - | 1 | 1.54 | - | - | 1 | 1.12 | 1 | 1.25 | 2 | 1.35 | 1 | 5.89 |

| Not Stated | 113 | 26.58 | 5 | 62.50 | 23 | 35.38 | 3 | 16.67 | 30 | 33.71 | 15 | 18.75 | 34 | 22.97 | 3 | 17.65 |

Note: AVB = Analysis of Verbal Behavior; BAP = Behavior Analysis in Practice; BAT= The Behavior Analyst Today/BARP = Behavior Analysis: Research and Practice; BI = Behavioral Interventions; BMOD = Behavior Modification; JABA = Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis; TPR = The Psychological Record.

Social Validity Assessment Timing

Social validity assessment timing can be viewed in Table 1. Authors reported timing of the social validity assessment, relative to intervention was recorded in the full data set of 425 articles. Authors reported assessing social validity at a single time point in 65.18% (n = 277) of articles. Of these 277 articles, 94.95% (n = 263) reported social validity assessment occurring after the implementation of the intervention, 3.97% (n = 11) reported assessment of social validity during the implementation of the intervention, and 1.08% (n = 3) reported assessment of social validity before the intervention. Authors reported assessing social validity at multiple time points in 8.24% (n = 35); of articles, 65.71% (n = 23) occurred before and after intervention, 17.14% (n = 6) occurred during and after intervention, and 17.14% (n = 6) occurred before, during, and after intervention. Timing was not reported in 26.58% (n = 113) of articles. Patterns of reported social validity assessment timing across all included journals as seen in Table 1 were explored and comparable results were identified.

Demographics of Direct Consumers

Inclusion of direct consumers in the social validity assessment can be viewed in Table 2. Across the full set of 425 articles, a subset of 55.53% (n = 236) articles included at least one direct consumer of the intervention with a reported disability and/or MH disorder with every journal including at least one of this direct consumer type. Across articles, all direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders were included in the social validity assessment in 28.39% (n = 67), some direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders were included in the social validity assessment in 6.36% (n = 15) of articles, and none of the direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders were included (i.e., all were excluded) in the social validity assessment in 65.25% (n = 154) of articles. These findings varied by journal and ranged from 0% to 100% of direct consumers included across articles within journals as seen in Table 2.

Table 2.

Inclusion of direct consumers with disabilities and/or mental health disorders in the social validity assessment

| All Included | Some Included | All Excluded | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Subset of Articles | 236 | 67 | 28.39 | 15 | 6.36 | 154 | 65.25 |

| Analysis of Verbal Behavior | 8 | 1 | 12.50 | 0 | - | 7 | 87.50 |

| Behavior Analysis in Practice | 37 | 9 | 24.32 | 0 | - | 28 | 75.68 |

| The Behavior Analyst Today/Behavior Analysis Research and Practice | 5 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 5 | 100.00 |

| Behavior Interventions | 60 | 10 | 16.67 | 2 | 3.33 | 48 | 80.00 |

| Behavior Modification | 52 | 25 | 48.08 | 7 | 13.46 | 20 | 38.46 |

| Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis | 73 | 21 | 28.77 | 6 | 8.22 | 46 | 63.01 |

| The Psychological Record | 1 | 1 | 100.00 | 0 | - | 0 | - |

Note. Across the full data set of 425 articles, a subset of 236 articles included at least one participant with a reported disability and/or mental health disorder.

Demographics reported can be viewed in Table 3. Of the subset of 236 articles that included a direct consumer with a disability and/or MH disorder, all reported the age and disability and disorder type of direct consumers. The gender of direct consumers (e.g., man, woman, transgender, nonbinary, boy, girl) was reported in 47.46% (n = 112) of articles. The sex (e.g., male, female, or intersex) of direct consumers was reported in 50.85% (n = 120) of articles. Race (e.g., American Indian, Asian, white/Caucasian, Black) of direct consumers was reported in 25.00% (n = 59) of articles and the ethnicity of direct consumers (e.g., identified as Hispanic or Latinx) was reported in 12.88% (n = 29) of articles. Of articles that included direct consumers with a disability and/or MH disorder, only 8.90% (n = 21) reported on direct consumer IQ and 48.31% (n = 114) reported that a communication delay or concern was present. Demographic reporting across behavior analytic journals (n = 7) was also explored and reporting varied by publication as seen in Table 3.

Table 3.

Demographics reported

| Age | Gender | Sex | Race | Ethnicity | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Subset of Articles | 236 | 236 | 100.00 | 112 | 47.46 | 120 | 50.85 | 59 | 25.00 | 29 | 12.29 |

| Analysis of Verbal Behavior | 8 | 8 | 100.00 | 1 | 12.50 | 6 | 75.00 | 0 | - | 0 | - |

| Behavior Analysis in Practice | 37 | 37 | 100.00 | 13 | 35.14 | 17 | 45.95 | 2 | 5.41 | 2 | 5.41 |

| The Behavior Analyst Today/ Behavior Analysis Research and Practice | 5 | 5 | 100.00 | 1 | 20.00 | 4 | 80.00 | 1 | 80.00 | 0 | - |

| Behavior Interventions | 60 | 60 | 100.00 | 12 | 20.00 | 20 | 33.33 | 40 | 66.67 | 5 | 8.33 |

| Behavior Modification | 52 | 52 | 100.00 | 14 | 26.92 | 34 | 65.38 | 17 | 32.69 | 16 | 30.77 |

| Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis | 73 | 73 | 100.00 | 45 | 61.64 | 16 | 21.92 | 10 | 13.70 | 3 | 4.11 |

| The Psychological Record | 1 | 1 | 100.00 | 1 | 100.00 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 0 | - |

Note. Across the full data set of 425 articles, a subset of 236 articles included at least one participant with a reported disability and/or mental health disorder.

Age

Patterns were identified across the subset of 236 articles related to direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders included or excluded from social validity assessments based on age as seen in Table 4. Of articles that included direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders aged 2 years or younger, 100% (n = 8) did not include any of the direct consumers in the social validity assessment. Of articles that included direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders ages 3–5, 8.75% (n = 7) included all direct consumers, 2.50% (n = 2) of articles included some, and 88.75% (n = 71) did not include any. Of articles that included direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders between the ages of 6 and 11, 21.60% (n = 27) included all direct consumers, 3.20% (n = 4) of articles included some, and 75.20% (n = 94) did not include any. Of articles that included direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders ages 12–17, 27.94% (n = 19) included all direct, 2.94% (n = 2) included some, and 69.12% (n = 47) did not include any. Of articles that included direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders who were 18 years of age or older 55.55% (n = 35) included all direct consumers, 7.94% (n = 5) included some, and 36.51% (n = 23) of articles did not include any of the direct consumers in the social validity assessment.

Table 4.

Inclusion of direct consumers of intervention by reported demographic information

| All Included | Some Included | All Excluded | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total n of articles | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Age | |||||||

| 0-2 years | 8 | 0 | - | 0 | - | 8 | 100.00 |

| 3-5 years | 80 | 7 | 8.75 | 2 | 2.50 | 71 | 88.75 |

| 6-11 years | 125 | 27 | 21.60 | 4 | 3.20 | 94 | 75.20 |

| 12-17 years | 68 | 19 | 27.94 | 2 | 2.94 | 47 | 69.12 |

| 18+ years | 63 | 35 | 55.55 | 5 | 7.94 | 23 | 36.51 |

| Communication | |||||||

| Delay Reported | 118 | 19 | 16.10 | 11 | 9.32 | 88 | 74.58 |

| No Delay Reported | 118 | 48 | 40.68 | 4 | 3.39 | 66 | 55.93 |

Note. Across the full data set of 425 articles, a subset of 236 articles included at least one participant with a reported disability and/or mental health disorder. When examining direct consumer age, articles were counted based on whether direct consumers represented age categories and thus some articles were counted in multiple age categories.

Communication Delay

Patterns were identified across the subset of 236 articles related to direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders included or excluded from the social validity assessment if there was a described communication delay as seen in Table 4. Of articles where all direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders were included in the social validity assessment, 16.10% (n = 19) of articles reported that at least one direct consumer had communication delays. Of articles where some direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders were included in the social validity assessment, 9.32% (n = 11) of articles reported that at least one direct consumer had communication delays. Of articles where none of the direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders were included in the social validity assessment, 74.58% (n = 88) of articles reported that at least one direct consumer experienced communication delays.

Disability and Disorder Type

Direct consumers’ diagnoses as reported by the authors were described in 100.00% of the subset of 236 articles. Of these articles, 59.75% (n = 141) had direct consumers with IDD (inclusive of ASD), 12.29% (n = 29) had direct consumers with MH disorders, 11.02% (n = 26) had direct consumers with a disability and MH disorder or health condition, 9.32% (n = 22) had direct consumers with multiple disabilities, 2.97% (n = 7) had direct consumers who were reported to have an educational classification or other disorder not listed in this analysis (i.e., other), 2.12% (n = 5) had direct consumers with specific learning disabilities, 1.27% (n = 3) had consumers with ADD/ADHD, and 1.27% (n = 3) had direct consumers with language impairment.

Across articles, 1571 direct consumers were included. Of these consumers, 42.46% (n = 667) were described as having one or more MH disorders, 35.77% (n = 562) were described with an IDD (including 509 direct consumers with ASD), 11.71% (n = 184) were described as having multiple disabilities, 4.26% (n = 67) were described as having a disability and MH disorder or health condition, 2.16% (n = 34) were categorized as other, 2.10% (n = 33) were described as having a SLD, 1.02% (n = 16) of direct consumers were described as having ADD/ADHD, and 0.51% (n = 8) were described as having a language impairment. Two of the 236 articles in the subset presented the direct consumers as a group and did not report the individual number of direct consumers included in the article. Authors reported including 47.42% (n = 745) of direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders in the social validity assessment and excluding 43.60% (n = 685). It was unable to be determined whether direct consumers were included in or excluded from participation in the social validity assessment for 8.98% (n = 141) consumers.

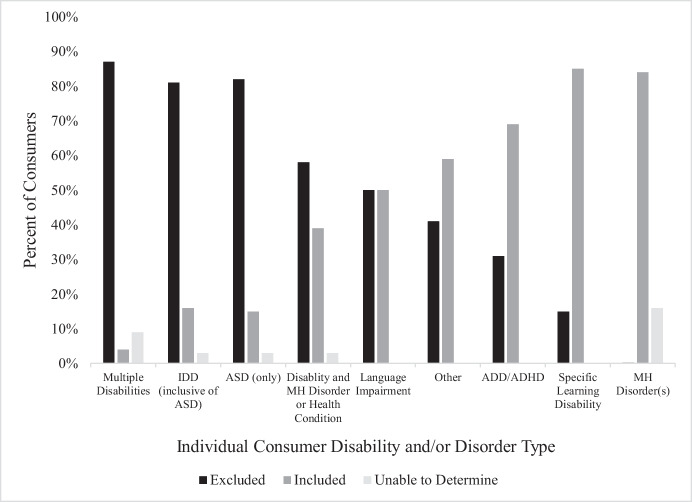

Patterns were identified across articles related to direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders included or excluded from the social validity assessment based on disability and disorder type as seen in Fig. 1. Of direct consumers described as having multiple disabilities, 86.41% (n = 159) were excluded from participating in the social validity assessment, 4.35% (n = 8) were included in the social validity assessment, and inclusion was unable to be determined for 9.24% (n = 17) of direct consumers. Of direct consumers with IDD (inclusive of ASD), 81.49% (n = 458) were excluded, 15.84% (n = 89) were included and inclusion was unable to be determined for 2.67% (n = 15). Of note, many direct consumers in the IDD category were described as having ASD; of direct consumers with ASD, 82.51% (n = 420) were excluded from participation in the social validity assessment, 14.54% (n = 74) were included in the social validity assessment, and inclusion was unable to be determined for 2.95% (n = 15). Of direct consumers described as having a disability co-occurring with MH disorders and/or a health condition, 58.21% (n = 39) were excluded, 38.80% (n = 26) were included and inclusion was unable to be determined for 2.99% (n = 2) of direct consumers. Of direct consumers with language impairments, 50.00% (n = 4) were excluded from participation in the social validity assessment; 50.00% (n = 4) were included. Of direct consumers in the other category, 41.18% (n = 14) were excluded and 58.82% (n = 20) were included in the social validity assessment. Of direct consumers with ADD/ADHD, 31.25% (n = 5) were excluded from participation in the social validity assessment and 68.75% (n = 11) were included. For direct consumers categorized as SLD, 15.15% (n = 5) were excluded from participation in the social validity assessment and 84.85% (n = 28) were included. Of direct consumers described as having one or more MH disorders (without co-occurring disability), 0.15% (n = 1) were excluded from participation in the social validity assessment, 83.81% (n = 559) were included, inclusion was unable to be determined for 16.04% (n = 107).

Fig. 1.

Direct consumers included in social validity assessments by consumer disability and/or disorder type. IDD= Intellectual and Developmental Disability; ASD= Autism Spectrum Disorder; ADD/ADHD= Attention Deficit Disorder/Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder; MH= One or more co-occurring Mental Health Disorders

Discussion

A data set of behavior analytic research articles published in behavioral journals that included both an intervention intended to change human behavior and a social validity assessment (Huntington et al., 2023) were examined to address the following research questions: (1) What is the source of the social validity assessment measures used in the behavioral intervention literature? (2) When are social validity assessments being conducted relative to the intervention in behavioral intervention literature? (3) What are the demographic characteristics of direct consumers that are included and excluded from social validity assessments? (4) How often do social validity assessments include the perspectives of direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders?

Social Validity Assessment Source

Scholars have consistently suggested that the variety, rigor, and content of social validity assessment measures be improved (Carr et al., 1999; Ferguson et al., 2019; Huntington et al., 2023; Kennedy, 1992; Snodgrass et al., 2018) but there remains limited information about the source of the social validity measures being used in the behavioral literature (Ledford et al., 2016). Of the 425 articles in the full data set, the most common social validity source was author-created. This was true across all included journals individually, as well as the full data set as seen in Table 1. This finding is a strong addition to the literature as previous reviews have focused on the social validity assessment type and quality (Carr et al., 1999; Ferguson et al., 2019; Huntington et al., 2023; Kennedy, 1992; Snodgrass et al., 2018) but few have identified the social validity assessment by source (i.e., where the assessment came from, e.g., Park & Blair, 2019).

Our finding that behavior analytic researchers overwhelmingly rely on author-created social validity assessments may be logical given the ability to individualize these assessments to fit the studies’ purpose. In addition, some may argue that these measures best fit the intent of the social validity assessment which is to individualize the assessment process for targeted consumers. It is also possible that researchers rely on self-created methods due to the limitations of established methods not fitting their articles' purpose or population. Given the frequent use of author-created assessments, future research should consider recommendations to improve the variety, quality, and content of these assessments. In addition, authors should consider describing their author-created assessments with technological precision to aid in practice-based replication and potential data comparison across articles, interventions, and populations (Fawcett, 1991; Huntington et al., 2023).

Future research should also consider creating additional social validity assessment tools that can be more universally applied across settings, populations, and research questions (e.g., Intervention Rating Profile; Witt & Martens, 1983). This suggestion may be a first step towards Schwartz and Baer’s (1991) unanswered call for increasing the psychometric rigor of social validity assessments. If researchers choose to adapt established measures, these adaptations should be clearly described with a rationale for why these assessments are being altered. Future research should also consider the validity of these adapted measures.

Social Validity Assessment Timing

Many reviews have found that historically, social validity assessments are most often conducted after the intervention (D’Agostino et al., 2019; Ferguson et al., 2019; Kennedy, 1992; Ledford et al., 2016; Park & Blair, 2019; Snodgrass et al., 2018). Likewise, social validity assessments are most often conducted at a single time point, with most articles collecting social validity data only after the intervention concluded as seen in Table 1. Overall, social validity assessment timing was poorly reported with approximately 27% of articles not reporting when the assessment was conducted. Schwartz and Baer (1991) argued that social validity assessments should be delivered on an ongoing basis to appropriately adapt goals and intervention procedures to consumer feedback. Schwartz and Baer (1991) further contended that if consumers do not see change based on their feedback, the assessments will be viewed as useless at best and fraudulent at worst. Given this consideration, conducting a social validity assessment at a single time point and only after the intervention has concluded is problematic and may fail to serve the purpose of the social validity assessment (i.e., to promote the social importance of interventions and associated outcomes; Schwartz & Baer, 1991). Some may argue that the assessment of social validity may be more complicated in research settings by limited flexibility of research goals or short timelines. Still, others may contend that given the voluntary nature of participation in research and practice, it is imperative to ensure that the goals of an intervention are meaningful and acceptable to the participants, regardless of the setting. Future research should consider the usefulness of social validity assessments conducted at single and multiple time points in the intervention process and if these recommendations should change from research to practice settings. In addition, researchers should consider the purpose of the social validity assessments and ensure that ongoing evaluation of social validity is meaningfully improving service delivery on an ongoing basis (Schwartz & Baer, 1991).

Demographics of Direct Consumers

The most underexplored recommendation to improve the implementation of social validity assessments is to expand the variety of consumers participating. To our knowledge, no in-depth analysis of consumer demographics has been conducted on those participating in social validity assessments. Of the subset of 236 articles that included direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders, direct consumer demographics were inconsistently and often underreported with sex, gender, ethnicity, and race all being reported in 50% or less of articles as seen in Table 3. In addition, coders reported demographic data exactly as written by the article authors, but an informal review of the data suggests that sex and gender were often conflated. Likewise, authors often failed to differentiate between race and ethnicity in their reporting and it was common to report one or the other but not both. This implies that important demographic data is not only left out of articles published in behavioral journals and that the information provided may not be accurate. In addition, as noted above, two of the articles in subset of 236 analyzed for demographic data did not report the number of direct consumers included in the article. These omitted and inconsistent demographic data limited the analysis, and thus no conclusions can be drawn about inclusion or exclusion from social validity assessments based on these demographics. These concerns with demographic reporting are consistent with other research on the topic (Brodhead et al., 2014; Jones et al., 2020) and should be a point for all future researchers to consider striving to improve the quality and technological rigor of research articles as well as accurate and respectful reporting of direct consumers. In addition, without these pieces of critical demographic information, it is difficult to determine patterns of social validity that could improve intervention quality and acceptability with diverse populations. The most consistently reported demographic characteristics were age, descriptions of communication delays, and disability and disorder type; additional analysis was possible for these variables.

Age

Our data indicates that participation in social validity assessments increased by age for consumers as seen in Table 4. For example, in articles that described direct consumers who were 0 to 2 years old, all direct consumers with disabilities were excluded from the social validity assessments. In contrast, in articles that contained direct consumers who were 18 years old or older less than half of those consumers were excluded from the social validity assessments. Along with the noted trends in the analysis that imply that younger direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders are more likely excluded and older direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders are more likely to be included, at least two articles in the analysis that included direct consumers of mixed ages included the older direct consumers (i.e., age 19 and above) in the social validity assessment and excluded the younger ones (i.e., age 7 and below). This trend seems to support previous reviews related to social validity which found that only 3% of young children were included in the social validity assessment (Heal & Hanley, 2008). To our knowledge, no best practice recommendations exist that discuss exclusion from social validity assessments based on age and future research should consider this variable when determining at what age, if at all, it is appropriate to include or exclude direct consumers.

Communication Delay

Considering communication delays, almost 75% of articles that included direct consumers with reported delays excluded all of them from the social validity assessment as seen in Table 4. As such, delays in communication seem to have a strong influence on direct consumers' inclusion or exclusion from social validity assessments. Hanley (2010) contended that if a direct consumer has limited language skills, it is unlikely that consumer will be included in subjective (e.g., opinion-based) social validity assessments. These findings align with Schwartz and Baer (1991) recommendations for future researchers to create additional methods of gathering social validity data from a variety of consumers, including those with limited language and writing skills. Objective social validity assessments have been proposed (Hanley, 2010; Huntington & Schwartz, 2022) and should continue to be explored as a means of including these direct consumers. Professionals within the field of ABA (e.g., Breaux & Smith, 2023; Schwartz & Baer, 1991) and outside of it (e.g., Anderson, 2023; McGill & Robinson, 2020) are strongly advocating for the voices and opinions of those served to be highlighted, respected, and accommodated. The authors of this article contend that this should be applied equally to those whose voices are not easily understood or those that cannot be heard. We strongly urge researchers to prioritize gathering opinion-based data from direct consumers with limited communication and making goal, intervention, and outcome decisions accordingly. If strategies to do so are not currently available, then the field must dedicate time and effort to developing them.

Disability and Disorder Type

Regarding disability and disorder type, of the direct consumers with MH disorders only, more than 80% were included in the social validity assessment as seen in Fig. 1. In contrast, those with disabilities were only included in the social validity assessments less than 20% of the time within certain disability categories. This relationship was examined by articles and by individual consumers. Direct consumers with multiple disabilities and IDD (inclusive of ASD) were most likely to be excluded from social validity assessments. Together, this represents the largest group of direct consumers in the entire data set and represents a sizable portion of the analysis. In contrast, direct consumers with one or more MH disorders without a co-occurring disability were more likely to be included in social validity assessments. The inclusion and exclusion patterns among direct consumers with ASD both within the IDD category and as a separate category were also examined. More than three quarters of direct consumers with ASD were excluded from participation in social validity assessments.

This finding is an important addition to the existing literature, as it contrasts with previous reviews on social validity which found direct consumers to be the most common social validity assessment respondent (D’Agostino et al., 2019; Snodgrass et al., 2018). This discrepancy may have arisen based on this article's definition of “direct consumer.” This article included only direct consumers with a disability and/or MH disorder whereas others included all direct consumers (e.g., parents who were the direct consumer of an intervention; Snodgrass et al., 2018). This seems to indicate that direct consumers with disabilities and/or MH disorders may be included at lower rates than direct consumers without them in social validity assessments. In addition, the data indicates that those with certain disabilities (e.g., IDD) are included at even lower rates than others with disabilities and/or MH disorders.

Future research should consider why these discriminatory patterns, resulting in the exclusion of consumers with certain disabilities, are occurring more often than others (see Figure 1) and resulting in an overall pattern of exclusion (see Table 2) and take proactive steps to rectify this. Such steps should include the use of existing and the development of new social validity assessment strategies that are accessible and meaningful for all consumers, and the provision of accommodations and modifications to support inclusion. The inclusion of direct consumers with disabilities in social validity assessments must be a priority if behavior-analytic research goals, procedures, and outcomes are to be considered socially important (Schwartz & Kelly, 2021), and the recommendations by Schwartz and Baer (1991) to expand inclusion are to be met. In addition, it may be useful for future research to explore the social validity assessments being utilized with indirect consumers and direct consumers with MH disorders to better understand why some were included and others were not.

Limitations

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting these data. First, due to issues with accurate reporting of direct consumer sex and gender, as well as insufficient data on direct consumer ethnicity, race, and IQ, these data were not analyzed and therefore, patterns that might exist were not identified. Second, the type of assessment used was not recorded (e.g., questionnaires, scales), how it was adapted, or when specific assessments were implemented. It was noted that different assessments were used at specific time points, but these data points were not systematically collected and therefore, conclusions cannot be made about these observations. Third, the anecdotal findings suggest that patterns are present regarding distinct types of social validity assessments being used with different populations (e.g., objective assessments may be used more commonly with consumers with communication delays), but these data cannot be reported because it was not systematically collected. Finally, it was not noted whether diagnoses were verified through diagnostic assessment in each article.

Conclusion

ABA, at its heart, is a science of social significance. Wolf (1978) reminds us that all aspects of ABA intervention (i.e., goals, procedures, outcomes) must be meaningful and important for those receiving it. Although Schwartz and Baer (1991) and many other scholars have provided ample suggestions for improving the measurement and assessment of social validity, these findings highlight that behavioral researchers still have much to do to ensure that the goals of improving social validity assessment are met, that researchers and practitioners are conducting social validity assessments in an ongoing meaningful way, and all are advocating for all direct consumer voices to be included. Huntington et al. (2023) highlighted that the frequency of social validity assessment in behavioral research is rapidly increasing. The recommendation from scholars before us bears repeating that journals should develop guidelines for publication regarding social validity assessments in applied research to ensure that increasing patterns of publishing social validity assessment continue. It is important to remember, however, that increasing in frequency is not enough. Researchers and practitioners must ensure that the quality of social validity assessments is sufficient and that direct consumers are meaningfully included as partners in research and as experts in their interventions (Arthur et al., 2023; Pritchett et al., 2022; Shogren, 2023). Now is the time to ensure we are not, as Schwartz and Baer (1991) warn, missing the point of social validity assessment.

Acknowledgements

Special thanks to Leicee Teighlyr Guiou for the development of the paper.

Authors note

This project was led by Rachelle Huntington; the article was co-authored by Rachelle Huntington and Natalie Badgett with writing support from authors 3–8. Natalie completed the majority of this work at the University of North Florida but has since moved to the University of Utah. Jakob completed the majority of this work at the University of North Florida but has since moved to Ruby Beach Behavioral Pediatrics. Alice completed the majority of this work at Seattle Pacific University but has since moved to the University of Washington. Madelynn completed the majority of this work at the University of Virginia but has since moved to the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Data Availability

The data are available from the first author upon request.

Declarations

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to report.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Anderson, L. K. (2023). Autistic experiences of applied behavior analysis. Autism,27(3), 737–750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arthur, S. M., Linnehan, A. M., Leaf, J. B., Russell, N., Weiss, M. J., Kelly, A. N., Saunders, M. S., & Ross, R. K. (2023). Concerns about ableism in applied behavior analysis: An evaluation and recommendations. Education & Training in Autism & Developmental Disabilities,58(2), 127–143. [Google Scholar]

- Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. R. (1968). Some current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,1(1), 91–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baer, D. M., Wolf, M. M., & Risley, T. R. (1987). Some still current dimensions of applied behavior analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,20(4), 313–327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Breaux, C. A., & Smith, K. (2023). Assent in applied behaviour analysis and positive behaviour support: ethical considerations and practical recommendations. International Journal of Developmental Disabilities,69(1), 111–121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brodhead, M. T., Durán, L., & Bloom, S. E. (2014). Cultural and linguistic diversity in recent verbal behavior research on individuals with disabilities: A review and implications for research and practice. Analysis of Verbal Behavior,30, 75–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr, J. E., Austin, J. L., Britton, L. N., Kellum, K. K., & Bailey, J. S. (1999). An assessment of social validity trends in applied behavior analysis. Behavioral Interventions: Theory & Practice in Residential & Community-Based Clinical Programs,14(4), 223–231. [Google Scholar]

- Carter, S. L., & Wheeler, J. J. (2019). The social validity manual: Subjective evaluation of interventions. Elsevier Science. [Google Scholar]

- D’Agostino, S. R., Douglas, S. N., & Duenas, A. D. (2019). Practitioner-implemented naturalistic developmental behavioral interventions: Systematic review of social validity practices. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education,39(3), 170–182. [Google Scholar]

- Fawcett, S. B. (1991). Social validity: A note on methodology. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,24(2), 235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferguson, J. L., Cihon, J. H., Leaf, J. B., Van Meter, S. M., McEachin, J., & Leaf, R. (2019). Assessment of social validity trends in the journal of applied behavior analysis. European Journal of Behavior Analysis,20(1), 146–157. [Google Scholar]

- Hanley, G. P. (2010). Toward effective and preferred programming: A case for the objective measurement of social validity with recipients of behavior-change programs. Behavior Analysis in Practice,3, 13–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heal, N., & Hanley, G. P. (2008, May). Social validity assessments of behavior-change procedures used with young children: A review. In C. St. Peter Pipkin (eds), Measuring social validity during behavioral research and consultation. Symposium conducted at the 34th Annual Convention of the Association for Behavior Analysis International.

- Huntington, R. N., & Schwartz, I. S. (2022). The use of stimulus preference assessments to determine procedural acceptability for participants. Journal of Positive Behavior Interventions,24(4), 325–336. [Google Scholar]

- Huntington, R. N., Badgett, N., Rosenberg, N., Greeny, K., Bravo, A., Bristol, R., Byun, Y., & Park, M. (2023). Social validity in behavioral research: A selective review. Perspectives on Behavior Science,46(1), 201–215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones, S. H., St. Peter, C. C., & Ruckle, M. M. (2020). Reporting of demographic variables in the Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,53(3), 1304–1315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, C. H. (1992). Trends in the measurement of social validity. The Behavior Analyst,15(2), 147–156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ledford, J. R., Hall, E., Conder, E., & Lane, J. D. (2016). Research for young children with autism spectrum disorders: Evidence of social and ecological validity. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education,35(4), 223–233. [Google Scholar]

- Lord, C., Charman, T., Havdahl, A., Carbone, P., Anagnostou, E., Boyd, B., ..., & McCauley, J. B. (2022). The Lancet Commission on the future of care and clinical research in autism. The Lancet, 399(10321), 271–334. [DOI] [PubMed]

- McGill, O., & Robinson, A. (2020). “Recalling hidden harms”: Autistic experiences of childhood applied behavioural analysis (ABA). Advances in Autism,7(4), 269–282. [Google Scholar]

- Park, E. Y., & Blair, K. S. C. (2019). Social validity assessment in behavior interventions for young children: A systematic review. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education,39(3), 156–169. [Google Scholar]

- Pritchett, M., Ala’i-Rosales, S., Cruz, A. R., & Cihon, T. M. (2022). Social justice is the spirit and aim of an applied science of human behavior: Moving from colonial to participatory research practices. Behavior Analysis in Practice,15(4), 1074–1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, I. S., & Baer, D. M. (1991). Social validity assessments: Is current practice state of the art? Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,24(2), 189–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, I. S., & Kelly, E. M. (2021). Quality of life for people with disabilities: Why applied behavior analysts should consider this a primary dependent variable. Research and practice for persons with severe disabilities,46(3), 159–172. [Google Scholar]

- Shogren, K. A. (2023). The right to science: Centering people with intellectual disability in the process and outcomes of science. Intellectual & Developmental Disabilities,61(2), 172–177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snodgrass, M. R., Chung, M. Y., Meadan, H., & Halle, J. W. (2018). Social validity in single-case research: A systematic literature review of prevalence and application. Research in Developmental Disabilities,74, 160–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Witt, J. C., & Martens, B. (1983). Intervention rating profile. Psychology in the Schools,20, 510–517. [Google Scholar]

- Wolf, M. M. (1978). Social validity: The case for subjective measurement or how applied behavior analysis is finding its heart. Journal of Applied Behavior Analysis,11(2), 203–214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data are available from the first author upon request.