Abstract

Cotton thrip, Thrips tabaci is a major polyphagous pest widely distributed on a variety of crops around the world, causing huge economic losses to agricultural production. Due to its biological and genomic characteristics, this pest can reproduce quickly and develop resistance to various pesticides in a very short time. However, the lack of high-quality reference genomes has hindered deeper gene function exploration and slows down the development of new management strategies. Here, we assembled a high-quality genome of T. tabaci at the chromosome level for the first time by using Illumina, PacBio long reads, and Hi-C technologies. The 329.59 Mb genome was obtained from 320 contigs, with a contig N50 of 1.53 Mb, and 94.21% of the assembly was anchored to 18 chromosomes. In total, 17,816 protein-coding genes were annotated, and 96.78% of BUSCO genes were fully represented. In conclusion, this high-quality genome provides a valuable genetic basis for our understanding of the biology of T. tabaci and contributes to the development of management strategies for cotton thrip.

Subject terms: Genome, Entomology

Background & Summary

Cotton thrip Thrips tabaci (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) is a polyphagous and devastating global insect pest species on numerous agricultural crops1–4 (Fig. 1). T. tabaci is widespread in more than 120 countries and regions, including Asia, Europe, North America, South America, Australia, and Africa, and causes severe damage to more than 50 crops, including cotton, onions, leeks, garlic, cabbage, cucumbers, peas, strawberries, peppers and potatoes1,5–7. The first and second instar larvae and adults of T. tabaci can feed on different plant organs to directly damage the crops or indirectly transmit plant orthotospoviruses, namely, Tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV), Iris yellow spot virus (IYSV), Tomato yellow ring virus (TYRV) and Alstroemeria yellow spot virus (AYSV)2,8–11. Pesticides application is the most widely used management strategy to control T. tabaci at present. However, T. tabaci still causes significant damage to the global agricultural system due to their small size, cryptic behaviour, polyophagy, short generation time, high reproductive capacity, dispersal to neighbouring farmfields or greenhouses, and transport along the international trade in agricultural products, while resistance to serial pesticides has been observed in several T. tabaci populations around the world, resulting in particular damage in turn12–16. Therefore, to facilitate more innovative management strategies for this destructive pest, a deeper understanding of its genetics is needed and remains to be completed.

Fig. 1.

Morphological characteristics of Thrips tabaci across different development stages.

Previous studies have shown that polyphagous insects adapt to changing environments by inducing changes in gene expression related to detoxification enzymes when feeding on different crops or pesticides17–19. The variation and selective expression of these genes make T. tabaci resistant to pesticides, which increases the difficulty of control18,20,21. Therefore, there is an urgent need for genomic resources for molecular biology and physiology studies of pesticide resistance and reproduction in T. tabaci. Thysanoptera is one of the most important insects in the world, but only 6 thrips have had their genomes sequenced to date, namely Frankliniella intonsa, Frankliniella occidentalis, Megalurothrips usitatus, Stenchaetothrips biformis, Thrips palmi, and Aptinothrips rufus, while T. tabaci lacked the vital data of genome22–24. In order to facilitate future research on the genetics, biology and ecology of T. tabaci, filling this knowledge gap will help provide theoretical support for optimizing management strategies for T. tabaci, which has important implications for pest control efforts.

In the present study, we propose a high-quality genome-assembly at chromosome level and conduct a whole life cycle transcriptome of T. tabaci using a combination of Illumina short-read sequencing, PacBio high fidelity (HiFi) reads, and high resolution chromosome conformation capture (Hi-C) techniques (Table 1). A 329.59 Mb genome was obtained from 320 contigs, with a contig N50 of 1.53 Mb (Tables 2), and 94.21% of the assembly (310.51 Mb of 329.59 Mb) was anchored to 18 chromosomes (Table 3) with a scaffold N50 of 16.56 Mb. We also predicted that the transposable elements accounted for 25.64% (12.40% retroelement and 13.24% DNA transposon) of the total genome sequence, and 9.22% of the total genome sequence was tandem repeats (Table 4). Besides, Eventually, 17,816 protein-coding genes (Table 5) was obtained, and the predicted genes were annotated and analyzed in eight databases: NR, EggNOG, GO, KEGG, TrEMBL, KOG, Swiss-Prot and Pfam. 13, 569 genes were annotated in the GO database, 12, 983 genes were annotated in the KEGG database, 10, 813 genes were annotated in the KOG database, 14, 275 genes were annotated in the Pfam database, 10, 404 genes were annotated in the Swiss-Prot database, 15, 652 genes were annotated in the TrEMBL database, 12, 768 genes were annotated in the EggNOG database, and 15, 114 genes were annotated in the NR database. Finally, A total of 16, 209 genes were annotated in all databases, accounting for 90.98% of all protein-coding genes (Table 6). Our genomic features of T. tabaci will lay a foundation for future ecological studies of thrips and provide a genetic basis for further studies of this polyphagous pest.

Table 1.

Statistics of sequencing data of Thrips tabaci genome.

| Library type | Usage | Insert Size (bp) | Clean Data (Gb) | Coverage (X) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Illumina | Genome survey | 350 | 24.51 | 87.99 |

| PacBio | Genome assembly | 20000 | 25.59 | 94.70 |

| Hi-C | Hi-C assembly | 150 | 56.30 | 208.34 |

| RNA-Seq (Illumina) | Anno-evidence | 150 | 85.91 | |

| RNA-Seq (PacBio) | Anno-evidence | 20000 | 33.07 |

Table 2.

Statistics of genome assembly of Thrips tabaci at the chromosomal-level.

| Features | Values |

|---|---|

| Estimate the genome size (Mb) | 278.54 |

| Total length (Mb) | 329.59 |

| Longest scaffold length (bp) | 21,765,751 |

| Contig numbers | 320 |

| Contig N50 (bp) | 1,531,534 |

| Reads length mean (bp) | 16,193 |

| Scaffold N50 (bp) | 16,564,241 |

| Scaffold N90 (bp) | 14,161,603 |

| GC (%) | 53.28 |

| Anchored to chromosome (Mb, %) | 310.51 (94.21%) |

Table 3.

Statistics of Hi-C assembly results.

| Pseudo-chromosomes | No. Cluster | Cluster Length (bp) | No. Order | Order Length (bp) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chr01 | 25 | 23,590,669 | 23 | 21,763,551 |

| Chr02 | 21 | 23,320,197 | 19 | 21,720,082 |

| Chr03 | 24 | 23,517,496 | 21 | 21,358,915 |

| Chr04 | 20 | 21,294,565 | 19 | 19,667,489 |

| Chr05 | 21 | 20,467,540 | 20 | 18,821,432 |

| Chr06 | 9 | 18,215,419 | 9 | 18,215,419 |

| Chr07 | 20 | 19,122,245 | 18 | 17,483,537 |

| Chr08 | 9 | 17,007,937 | 9 | 17,007,937 |

| Chr09 | 20 | 16,562,341 | 20 | 16,562,341 |

| Chr10 | 18 | 17,444,087 | 16 | 16,544,672 |

| Chr11 | 20 | 19,763,899 | 18 | 16,343,346 |

| Chr12 | 21 | 18,427,373 | 17 | 16,351,134 |

| Chr13 | 16 | 16,425,660 | 15 | 15,849,037 |

| Chr14 | 17 | 15,711,168 | 16 | 15,406,219 |

| Chr15 | 18 | 15,102,040 | 18 | 15,102,040 |

| Chr16 | 17 | 15,049,817 | 16 | 14,744,272 |

| Chr17 | 12 | 14,856,180 | 11 | 14,160,603 |

| Chr18 | 12 | 13,706,612 | 11 | 13,410,671 |

| Total (Ratio %) | 320 (100.00) | 329,585,245 (100.00) | 296 (92.50) | 310,512,697 (94.21) |

Table 4.

Classification of repeat elements in Thrips tabaci genome.

| Repeat types | Number | Length (bp) | Percent (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Retroelement | DIRS | 1 | 73 | 0 | 12.40 |

| LINE | 20,517 | 4,663,532 | 1.41 | ||

| SINE | 1,809 | 223,456 | 0.07 | ||

| LTR/Copia | 6,199 | 3,260,579 | 0.99 | ||

| LTR/ERV | 1,533 | 210,523 | 0.06 | ||

| LTR/Gypsy | 31,415 | 14,185,724 | 4.30 | ||

| LTR/Ngaro | 334 | 26,769 | 0.01 | ||

| LTR/Pao | 195 | 15,106 | 0 | ||

| LTR/Unknown | 118,446 | 18,271,408 | 5.54 | ||

| DNA transposon | Academ | 102 | 60,099 | 0.02 | 13.24 |

| CACTA | 1,044 | 89,800 | 0.03 | ||

| Crypton | 249 | 47,534 | 0.01 | ||

| Dada | 21 | 1,156 | 0 | ||

| Ginger | 117 | 6,997 | 0 | ||

| Helitron | 120,799 | 17,559,717 | 5.33 | ||

| IS3EU | 38 | 3,155 | 0 | ||

| Kolobok | 134 | 16,700 | 0.01 | ||

| Maverick | 482 | 229,551 | 0.07 | ||

| Merlin | 3 | 152 | 0 | ||

| Mutator | 10 | 1,274 | 0 | ||

| P | 2 | 45 | 0 | ||

| PIF-Harbinger | 80 | 30,609 | 0.01 | ||

| PiggyBac | 87 | 32,058 | 0.01 | ||

| Sola | 17 | 2,881 | 0 | ||

| Tc1-Mariner | 159 | 12,005 | 0 | ||

| Unknown | 99,195 | 25,342,075 | 7.69 | ||

| Zator | 41 | 18,447 | 0.01 | ||

| Zisupton | 61 | 3,487 | 0 | ||

| hAT | 1,375 | 174,669 | 0.05 | ||

| Unknown | 42 | 8,351 | 0 | ||

| srpRNA | 5 | 1,455 | 0 | ||

| Tandem repeat | Microsatellite (1–9 bp units) | 175,172 | 4,548,089 | 1.38 | 9.22 |

| Minisatellite (10–99 bp units) | 119,995 | 9,614,460 | 2.92 | ||

| Satellite (> = 100 bp units) | 11,590 | 16,241,158 | 4.93 | ||

| Total | 711,269 | 114,903,094 | 34.86 | ||

Table 5.

Gene annotation statistics of Thrips tabaci genome.

| Features | Results |

|---|---|

| Number of annotated genes | 17,816 |

| Total lineage BUSCOs | 1367 |

| Complete BUSCOs and Ratio | 1328 (97.15%) |

| Complete and single-copy BUSCOs and Ratio | 1032 (75.49%) |

| Complete and duplicated BUSCOs and Ratio | 296 (21.65%) |

| Fragmented BUSCOs and Ratio | 1 (0.07%) |

| Missing BUSCOs and Ratio | 38 (2.78%) |

| Average gene length (bp) | 7837.37 |

| Number of Exon | 138,164 |

| Average Exon length (bp) | 1760.30 |

| Average Exon count per gene | 7.76 |

| Number of CDS | 138,153 |

| Average CDS length (bp) | 1758.72 |

| Average CDS per gene | 7.75 |

| Number of Intron | 120,348 |

| Average Intron length (bp) | 6077.08 |

| Average Intron per gene | 6.76 |

Table 6.

Functional annotation statistics of Thrips tabaci genome.

| Annotation type | Genes number | Percent (%) | Homepage |

|---|---|---|---|

| GO | 13,569 | 76.16 | http://www.geneontology.org/ |

| KEGG | 12,983 | 72.87 | http://www.genome.jp/kegg/ |

| KOG | 10,813 | 60.69 | http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/KOG/ |

| Pfam | 14,275 | 80.12 | http://pfam.xfam.org/ |

| Swiss-Prot | 10,404 | 58.40 | http://www.uniprot.org/ |

| TrEMBL | 15,652 | 87.85 | http://www.uniprot.org/ |

| EggNOG | 12,768 | 71.67 | http://eggnog5.embl.de/#/app/home |

| NR | 15,114 | 84.83 | ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/blast/db/ |

| Total annotated genes | 16,209 | 90.98 |

Methods

Sample preparation and genomic DNA sequencing

A colony of Thrips tabaci originally collected from cotton field in Henan Province of China, was reared in the laboratory for approximately 100 generations. Adults were fed on Brassica oleracea and kept at controlled conditions of 25 ± 0.5 °C, 60 ± 5% relative humidity, and a photoperiod of 16 h Light: 8 h Dark25. Briefly, pupal thrips were decontaminated by immersing in 1% sodium hypochlorite solution for 5 min, followed by rinsing in sterile water and immersion in 70% ethanol twice, and then rinsing in sterile water again. Before genomic DNA and RNA extraction, samples were rapidly transferred to collection tubes and flash frozen in liquid nitrogen, then stored at −80 °C.

We prepared approximately 4,000 pupae of T. tabaci for genome sequencing. Genomic DNA was extracted using the QIAGEN® Genomic kit (QIAGEN, Dusseldorf, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The purity and concentration of genomic DNA was determined by 0.75% agarose gel electrophoresis, Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), and Qubit TM3 Fluorometer (Invitrogen, USA), successively.

To construct the library, the total genomic DNA was randomly sheared into fragments of ~15 kb. The SMRTbell library was constructed using the SMRTbell Express Template Prep kit 2.0 (Pacific Biosciences). Before annotating the data obtained by PacBio readings, we performed a series of preprocessing procedures. The sheared 10 μg of DNA was brought into the first enzymatic reaction to remove the single-strand dangling, and then treated with repair enzymes to repair any damage that may exist on the DNA backbone. After DNA damage repair, ends of the double-stranded fragments were polished and subsequently tailed with an A-overhang at the 3′end. Ligation with T-overhang SMRTbell adapters was performed at 20 °C for 60 minutes. Following ligation, the SMRTbell library was digested by exonuclease and purified with 0.45X AMPure PB beads. After library characterization, the Sage ELF system (Sage Science, Beverly, MA) was used to perform a size selection step on 3 μg to collect SMRTbells 15–18 kb. After size selection, the library was purified with 1X AMPure PB beads. The size and quantity of libraries were evaluated using FEMTO Pulse and Qubit dsDNA HS reagents Assay kits. The sequencing primers and Sequel II DNA polymerase were annealed and combined into the final SMRTbell library, respectively. The library was subjected to diffusion loading at 55 pM plate concentration.

The long-read library was sequenced on the PacBio Sequel II platform (Pacific Biosciences, USA) at BioMarker (Beijing) Co., Ltd., and circular consensus (CCS) reads were generated. The 150 bp paired-end short read sequencing libraries were sequenced on the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 platform. After filtering out the adapters and low-quality reads, approximately 25.59 Gb of subreads (coverage: 94.7 × ) were obtained from the PacBio long-read sequencing (Table 1). The PacBio reads had an average length of 16,193 bp, with an Contig N50 length of 1,531,534 bp (Table 2). The Illumina platform generated a total of 24.51 Gb (coverage: 87.99 × ) of clean data with an average insert size of 350 bp (Table 1).

Hi-C library preparation and sequencing

The Hi-C (high-throughput chromatin conformation capture) technique was used to construct the chromosome-level genome assembly of T. tabaci26. For Hi-C library construction, fresh tissues from 2000 pupae individuals were to be used. Formaldehyde is used to fix the sample, cross-link intracellular proteins with DNA, DNA with DNA, preserve their interactions, and maintain the 3D structure in the cell. The DNA is digested with the restriction enzyme DpnII, resulting in sticky ends on both sides of the crosslink. Finally, the DNA was broken into fragments of 300 bp to 700 bp, and streptaviin magnetic beads were used to capture DNA fragments containing interacting relationships for library construction. After the library inspection is qualified, the Illumina platform was used for high-throughput sequencing, and the sequencing read length is paired-end 150 bp. The Hi-C library was constructed following the standard library preparation protocol, and 56.30 Gb of clean data was generated (Table 1).

Transcriptome sequencing

Transcriptome samples were prepared at all developmental stages of T. tabaci including the 1st and 2nd instar nymphs, pupae and adults of T. tabaci, respectively. Separate total RNA was extracted from larvae, pupae, and adult samples collected above, using the TRIzol reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientifc, Waltham, USA). The complementary DNA (cDNA) library was constructed and sequenced on an Illumina Novaseq 6000 platform. After library construction, Qubit2.0 and Agilent 2100 were used to determine the concentration and insert size of the library, and Q-PCR was used to accurately quantify the effective concentration of the library to ensure the library quality. A total of 85.91 Gb clean RNA-seq data was obtained after the following quality control: removal of reads containing connectors and removal of low-quality reads (including reads that remove more than 10% of N; the reads with mass value Q ≤ 10 accounted for more than 50% of the entire read) (Table 1).

In addition, the full-length cDNA of mRNA was synthetised using the SMARTer™ PCR cDNA Synthesis Kit (Pacifc Biosciences, USA) for library construction. Subsequently, full-length transcriptome sequencing was performed on the PacBio Sequel II platform, and circular consensus (CCS) reads were generated. A total of 33.07 Gb full-length transcriptome data were obtained after the following quality control: according to the adaptor in the sequence, all the original sequences were converted into CCS sequences, and the CCS sequences were polished to obtain the quality information of the sequences. According to whether there were 3′ primers, 5′ primers and PolyA in the CCS sequence, the sequence was divided into full-length sequence and non-full-length sequence. The full-length sequences from the same transcript were clustered, and the similar full-length sequences were clustered into a cluster. Each cluster obtained a consistent sequence and extracted high-quality sequences (Table 1). Ultimately these high-quality sequencing data were mapped to the assembled genome to identify gene transcript levels27.

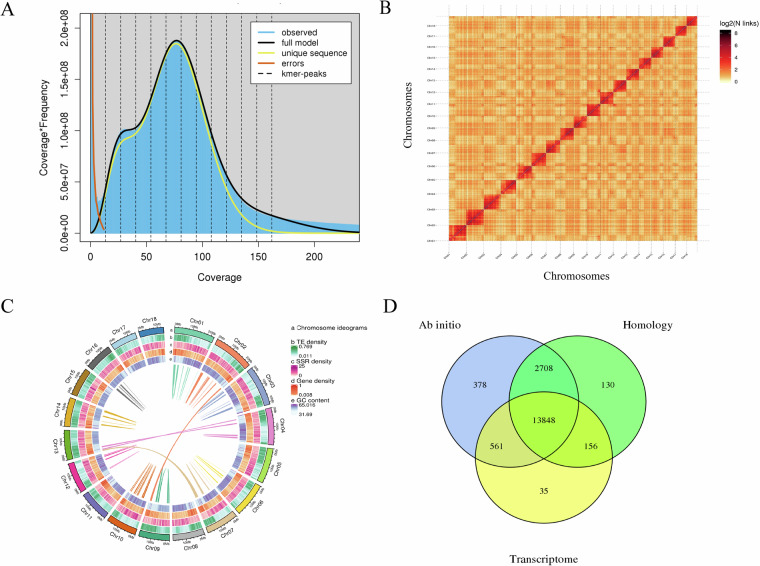

Estimation of genomic characteristics

Firstly, in order to evaluate the genomic characteristics of T. tabaci, the genome was investigated using next-generation sequencing, and 24.51 GB of high-quality data was generated, the short reads from the Illumina platform were quality filtered by Fastp (version 0.21.0)28 using the parameters of ‘-q 10 -u 50 -y -g -Y 10 -e 20 -l 100 -b 150 -B 150’. The high-quality filtered reads were used for further genome size estimation. In order to determine whether the DNA of the extracted samples was contaminated, 10,000 single-ended reads were randomly selected from a 350 bp library sequenced and compared to the NT library by BLAST (ncbi-blast + , version 2.2.29)29 with the parameter set to ‘-num_descriptions 100-num_alignments 100-evalue 1e-05’. The libraries sequenced by Illumina platform were compared with plastids for SOAP (version2.21)30, and the parameter was set to ‘-m 260-x 440’ to evaluate the extranuclear DNA content in the libraries and ensure the integrity of the genome assembly. We counted the 19-kmers using Jellyfish (version 2.1.4)31 with the following parameters ‘-h 10000000000’ and calculated the genome features using Genomescope (version2.0)32 with the parameters of ‘-k 19 -p 6 -m 100000’. Through fitting various ploidy data, it was found that the Kmer distribution map had the best fitting degree when it was hexaploid (Fig. 2A). Using hexaploid as fitting standard, the kmer depth corresponding to the first peak is 13.5, and the length of a single genome is approximately 278.54 Mb (Table 2). According to the distribution of kmer, it is estimated that the repetitive sequence content was about 33.14%, the heterozygosity was about 2.47%, and the GC content of the genome was about 51.39% (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2.

Genome assembly and temporal transcriptome of Thrips tabaci. (A) Genome scope profiles of 19-mer analysis. (B) Hi-C interactive heatmap of eighteen linkage pseudo-chromosomes in Thrips tabaci genome. Color indicates the intensity of the interaction signal. The darker the color, the higher the intensity. (C) Circle genome landscape of Thrips tabaci. Circle a represents chromosomes, while circles b-e indicate repeat density, SSR density, gene density, and GC content of each respective chromosome, respectively. (D) Protein-coding gene prediction of Thrips tabaci through three strategies.

De novo genome assembly

For the quality control of PacBio long reads (CCS) data, we mainly performed error correction of identifiable haplotypes. For CCS reads, although its accuracy is high, some errors are still retained. Hifiasm (version0.19)33 will read all CCS reads into memory for all-vs-all comparison and error correction. Based on the overlap informations between reads, if a base on a read is different from other bases and supported by at least three reads, it is considered to be a SNP and retained, otherwise it is considered to be wrong and corrected. It is worth noting that Hifiasm (version0.19)33 only uses the data of the same haplotype for error correction, thereby avoiding overcorrection and retaining heterozygous variation information from different haplotypes. In this step, Hifiasm (version0.19)33 can phasing the heterozygous SNP.

High accuracy CCS data was used for genome assembly by the Hifiasm (version0.19)33 with parameters ‘-2, -4’. For genomes with high heterozygosity, the initial assembly may assemble all the heterozygous fragments, resulting in a larger than expected genome. The purge_dups34 was used to resolve the haplotigs and overlaps in a primary assembly based on read depth, while Pilon35 and Racon36 were used to polish the assembly. The scaffold pipeline of the genome was deconstructed in equal lengths of 50 Kb and reassembled using Hi-C technology26. The locations that could not be restored to the original assembly sequence are listed as candidate error regions, and the locations with low Hi-C coverage depth in this region are identified as error points, thus completing the error correction of the original assembled genome. For anchored contigs, clean read pairs were generated from the Hi-C library and were mapped to the polished T. tabaci genome using BWA (version0.7.17)37 with the default parameters. Paired reads with mapped reads to a different contig were used to do the Hi-C associated scaffolding. Self-circle ligation, non-ligation and other invalid reads, such as Dangling Ends, Re-ligation, and Dumped Pairs were filtered. HiC-Pro (version2.10.0)38 can identify valid interaction pairs and invalid interaction pairs in Hi-C sequencing results by analyzing and comparing the results, and realize the quality evaluation of Hi-C library. We then successfully clustered 320 contigs into 18 groups (Table 3) using the agglomerative hierarchical clustering method in LACHESIS (version 2e27abb)39. Furthermore, 296 of 320 contigs were successfully ordered and oriented with the length of 310,512,697 bp via LACHESIS as well (Table 3). Finally, we obtained the first high-quality assembled genome of T. tabaci at the chromosome level. The genome was consisted of 320 contigs with a total length of 329.59 Mb, which was similar to the predicted size of 278.54 Mb, and with a scaffold N50 of 16.56 Mb, maximum length of 21.77 Mb, and GC rate of 53.28%. The analysis of Hi-C data helped to anchor 296 (92.50%) contigs of 310.51 (94.21%) Mb sequence to 18 pseudo-chromosomes, which were well-distinguished from each other based on the chromatin interaction heatmap (Tables 2, 3; Fig. 2B).

Repetitive elements and noncoding RNA annotation

Transposon elements (TE) and tandem repeats were identified using a combination of homology-based and de novo approaches. We first customized a de novo repeat library of the genome using RepeatModeler (version2.0.1)40 (http://www.repeatmasker.org/RepeatModeler/) with parameters ‘BuildDatabase -name & RepeatModeler -pa 12’, which can automatically execute two de novo repeat finding programs, including RECON (version1.0.8)41 and RepeatScout (version1.0.6)42. Then full-length long terminal repeat retrotransposons (fl-LTR-RTs) were identified using both LTR_FINDER (version2.8)43 with parameters ‘-w 2 -C -D’ and LTRharvest (version1.5.9)44 with default parameters. The high-quality intact fl-LTR-RTs and non-redundant LTR library were then produced by LTR_retriever (version2.9.0)45 with default parameters. Non-redundant species-specific TE library was constructed by combining the de novo TE sequence library above with the well-known Dfam (version3.5)46 database. Final TE sequences in the T. tabaci genome were identified and classified by homology search against the library using RepeatMasker (version4.12)47 with parameters ‘-nolow -no_is -norna -engine wublast -parallel 8 -qq’. Tandem repeats were annotated by Tandem Repeats Finder (TRF) (version409)48 with parameters ‘2 7 7 80 10 50 500 -d -h’ and MIcroSAtellite identification tool (MISA) (version2.1)49 with default parameters. In total, 34.86% of the assembled genome was classified as repetitive sequences in the 329.59 Mb genome, including transposable elements (TEs) with a sequence length of 84,499,387 bp, accounting for 25.64% of the whole genome, and tandem repeats with a sequence length of 30,403,707 bp, accounting for 9.22% of the whole genome (Table 4).

Non-coding RNAs are RNAs that do not encode proteins, including microRNA, rRNA, tRNA and other RNAs with unknown functions. According to the structural characteristics of different non-coding RNAs, several specific strategies are used to predict corresponding non-coding RNAs. tRNAscan-SE (version1.3.1)50 was used to identify tRNA with default parameters. Prediction of rRNA was mainly made using barrnap (version0.9)51 with parameters ‘kingdom euk–threads 1’. miRNA, snoRNA and snRNA were predicted based on the Rfam (version14.5)52 database via Infenal (version1.1)53 with parameters ‘cpu 3–rfam’. Finally, a total of 2,980 tRNAs, 61 rRNAs, and 27 miRNAs were obtained (Table 7).

Table 7.

Statistics of noncoding RNA in Thrips tabaci genome.

| No. tRNA | No. rRNA | No. miRNA |

|---|---|---|

| 2980 | 61 | 27 |

Gene Prediction and Functional Annotation

Before the gene annotation of CCS reads, we enriched the mRNA containing polyA tail by primers with Oligo-dT, and then reverse transcribed the mRNA using Iso-Seq RT enzyme. By adding template switching oligo (Template Switch Oligo, TSO), the synthesized cDNA was amplified by PCR. Then, the full-length cDNA was repaired by damage repair, end repair, and end plus A tail. Finally, the SMRT dumbbell-shaped sequencing adaptor was connected, and the sequencing primers were combined to bind the DNA polymerase to form a complete SMRT-bell sequencing library by using Iso-Seq (version 4.0.0) with default parameters.

We integrated three approaches, namely, de novo prediction, homology search, and transcript-based assembly, to annotate protein-coding genes in the genome. Based on the genome sequence, we used Augustus (version3.2.3)54 and SNAP (version2006-07-28)55 for ab initio gene prediction with default parameters. For homo-based approaches, GeneModelMapper (GeMoMa) (version1.7)56 was used with Aptinothrips rufus, Drosophila melanogaster, Frankliniella occidentalis, Trips palmi, and Megalurothrips usitatus (Table 8) as references with parameters ‘run.sh mmseqs’. For the transcript-based methods, RNA-seq reads were mapped to our assembled reference genome above by using Hisat (version2.1.0)57 with the parameters ‘dta -p 10’. Stringtie (version2.1.4)58 was then applied with parameters ‘p 2’ to assemble the mapped reads into transcripts. Genes were predicted from the assembled transcripts using GeneMarkS-T (version5.1)59 with default parameters. Meanwhile, the PASA (version2.4.1)60 was utilized to predict genes based on the unigenes assembled by Trinity (version2.11)61 with default parameters ‘genome_guided_bam’. Full-length transcripts from the PacBio sequencing were compared using gmap (version 2020-06-30) with parameters ‘cross-species–nthreads = 4 -f 2’, and then used PASA (version2.4.1)60 for gene prediction. Finally, we merged predicted genes obtained from strategies of homology-based, de novo-derived, and transcripts, to generate the high-confidence gene set using the EVidenceModeler (versio1.1.1)62 with default parameters. In total, 17,816 protein-coding genes with an average length of 7837.37 bp were obtained in the assembled T. tabaci genome (Table 5). The average length of coding sequence (CDS) was 1758.72 bp with a total number of CDS of 138,153. The average exon length was 1760.30 bp and the average Exon number of each gene was 7.76. The insecta database in BUSCO contains 1,367 conserved core genes (Table 5). We used Benchmarking Universal Single-Copy Orthologs (BUSCO, version5.2.2)63 with parameters ‘m prot’ to evaluate the completeness of gene prediction, where 97.15% of BUSCO genes were present in the predicted genes (Table 5), indicating a high completeness of gene prediction in T. tabaci.

Table 8.

The number of differential expressed genes in the pairwise comparisons of Thrips tabaci across 1st instar nymphs (N1), 2nd instar nymphs (N2), pupa and adult.

| Groups | DEGs_total | DEGs_up | DEGs_down |

|---|---|---|---|

| N1_vs_N2 | 2944 | 1530 | 1414 |

| N1_vs_Pupa | 2397 | 1040 | 1357 |

| N1_vs_Adult | 6868 | 3005 | 3863 |

| N2_vs_Pupa | 1416 | 774 | 642 |

| N2_vs_Adult | 8603 | 3895 | 4708 |

| Pupa_vs_Adult | 6537 | 2674 | 3863 |

Gene structure and annotations were identified according to the best match of the alignments to the public databases including National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Non-Redundant (NR) (ftp://ftp.ncbi.nih.gov/blast/db/), EggNOG64, KOG (http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/KOG/), GO (http://www.geneontology.org/), TrEMBL65 and Swiss-Prot protein databases65 (Table 6) using diamond (2.0.4.142) with parameters ‘masking 0 -e 0.001’. The data were also compared with the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) database66 (Table 6), with an E-value threshold of 1E-5. The motifs and domains within gene models were identified by Pfam databases67 (Table 6). In total, approximately about 90.98% (16209 of 17816 total predicted genes) of the predicted protein-coding genes could be annotated in those databases above (Fig. 2D, Table 6). Finally, the number of EVM-integrated genes supported by the three prediction methods were counted separately, and 13,848 genes were predicted by all three methods (Fig. 2D).

Temporal transcriptome of T. tabaci across nymphal, pupal, adult stage

Samples were collected from all developmental stages of T. tabaci, namely, first instar nymph, second instar nymph, pupa and adult. Fifty T. tabaci individuals were placed in each 1.5 mL collection tube with 3 replicates per stage. TRIzol reagent was used for RNA extraction. Transcriptome sequences were obtained using the same procedure as described in the section of “Transcriptome sequencing” above.

Hisat (version2.1.0)57 was used to quickly align the clean reads obtained from transcriptome sequencing accurately with the assembled genome of T. tabaci to obtain the location information of Reads on the reference genome. Then Stringtie (version2.1.4)58 was used to assemble the above reads, and the transcripts were reconstructed for subsequent analysis with default parameters. Finally, FPKM (Fragments Per Kilobase of transcript per Million fragments mapped) was standardized as an indicator to measure the level of transcript or gene expression68.

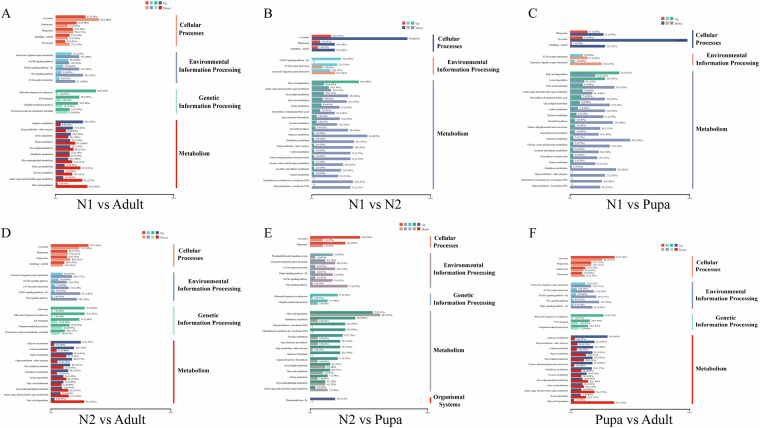

Based on the count value of genes in each sample, DESeq269 was used for differential expression gene screening and differential analysis. The False Discovery Rate (FDR) was obtained by correcting the significance p-value of the difference, in order to reduce false positives caused by changes in the expression of a large number of genes70. Finally, |log2FC| ≥ 2 and FDR < 0.01 were used as the criteria in the process of significantly differential expression gene detection. Hierarchical clustering analysis of all identified DEGs was performed, and genes with the same or similar expression patterns in different samples were clustered by hclust () function in R-packets. DEGs were mapped to GO terms and KEGG pathways, and an enrichment analysis was performed to identify any over-representation of GO terms and KEGG pathways by hypergeometric test (Figs. 3, 4; Table 8).

Fig. 3.

Differential expressed genes in pairwise comparison of Thrips tabaci across different developmental stages. (A) Venn diagrams of DEGs among those pairwise comparisons. (B–G) Volcanic maps of different expressed genes in separate comparison among different developmental stages. The red and green balls represent the significantly up- and down-regulated expressed genes, respectively.

Fig. 4.

Significantly enriched KEGG pathways of DEGs in these pairwise comparison of Thrips tabaci at different developmental stages.

Data Records

Genomic Illumina sequencing data were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive at NCBI under accession number SRR2644819171. Genomic PacBio sequencing data were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive at NCBI under accession number SRR2641791172. Hi-C sequencing data were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive at NCBI under accession number SRR2640108373. RNA-seq data were deposited in the Sequence Read Archive at NCBI under accession number PRJNA1028763 and SRR2640485574. The final assembled Thrips tabaci genome has been submitted to NCBI under accession number GCA_040581495.175. The annotation files of the Thrips tabaci genome have been deposited at figshare76.

Technical Validation

DNA integrity

Nanodrop 2000 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientifc, USA) and QubitTM3Flurometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) were used to detect the concentration of extracted DNA. Absorbance of obtained DNA at 260/280 nm and 260/230 nm were both about 1.8. The quality of genomic DNA was detected by agarose gel electrophoresis. The main band size of DNA fragments was ≥ 23 K, the degradation band was > 5 K. There was no contamination in the sample holes, which proved that good integrity of DNA molecules was observed in this study.

Assessment of genome assemblies

We assess the integrity and accuracy of the genome in four main ways: First, the short sequences obtained by Illumina sequencing platform were compared with the assembled genome through BWA (version0.7.17)37, and the integrity of the assembled genome and the uniformity of sequencing coverage can be assessed by statistical comparison rate, proportion of covered genomes, and depth distribution. The results showed that 164,272,072 clean reads were obtained, of which 155,286,329 were located to the reference genome, accounting for 94.53% of all Clean Reads (Table 9). Secondly, Minimap277 was used to compare HiFi reads with assembled genomes. The results showed that 1,580,153 clean reads were obtained by three-generation sequencing via PacBio CCS technology, and 1,532,715 clean reads were located to the reference genome, accounting for 97.00% of all clean reads (Table 9). Third, the Core Eukaryotic Genes Mapping Approach (CEGMA) was used to evaluate the assembled genome by selecting conserved genes (458 genes) existing in eukaryotic model organisms to form a core gene library to assess the integrity of the assembled genome. The results showed that 452 genes were identified in the assembled genome, accounting for 98.69% of the total. Finally, the single-copy gene set constructed by BUSCO (version5.2.2)63 was compared with the assembled genome, and the ratio and completeness of the comparison were evaluated. The results showed that the completeness of BUSCO evaluation was 96.78% with only 0.07% fragmented BUSCOs and 3.15% missing BUSCOs (Table 9). All of the above results indicate that our assembled Thrips tabaci genome has high integrity and accuracy. These BUSCO results were compared with the genome integrity of other thrips species, all of which were comparable, such as T. palmi (97.20%), M. usitatus (97.40%), and A. rufus (95.00%) (Table 10).

Table 9.

Assessment metrics for the final genome assembly of Thrips tabaci.

| Items | Types | Ratios |

|---|---|---|

| Genome completeness | Complete BUSCOs (C) | 96.78% |

| Complete and single-copy BUSCOs (S) | 87.93% | |

| Complete and duplicated BUSCOs (D) | 8.85% | |

| Fragmented BUSCOs (F) | 0.07% | |

| Missing BUSCOs (M) | 3.15% | |

| Genome accuracy | Mapping short-reads rate | 94.53% |

| Mapping HiFi reads rate | 97.00% |

Table 10.

Comparisons of genome assemblies of different thrips species.

| Species | Assembly level | Genome size (Mb) | Pseudo-chromosomes number | Scaffold N50 (Kb) | BUSCO (%) | GC (%) | Data source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Thrips tabaci | Chromosome | 329.59 | 18 | 16,564 | 96.78 | 53.28 | In this study |

| Megalurothrips usitatus Ref1 | Chromosome | 238.14 | 16 | 13,852 | 97.40 | 55.90 | 10.1038/s41597-023-02164-5 |

| Megalurothrips usitatus Ref2 | Chromosome | 247.82 | 16 | 14,859 | 98.60 | 55.40 | 10.3390/ijms241411268 |

| Trips palmi | Chromosome | 237.85 | 16 | 14,670 | 97.20 | 53.90 | 10.1111/1755-0998.13189 |

| Stenchaetothrips biformis | Chromosome | 338.86 | 18 | 18,207 | 96.60 | 51.09 | 10.1038/s42003-023-05187-1 |

| Frankliniella occidentalis | Scaffold | 274.99 | 15 | 4,180 | 98.50 | 48.40 | 10.1186/s12915-020-00862 |

| Aptinothrips rufus | Contig | 339.92 | 5 | 95.00 | 48.60 | http://v2.insect-genome.com/Organism/87 |

The 3 C (contiguity, completeness and correctness) criterion: 1) Contiguity: a total of 24.51 Gb data were obtained by short reads sequencing. The total sequencing depth was about 87.99 X, the GC content was about 51.39%, and the genome size was about 278.54 Mb; The amount of data obtained by long reads sequencing was 25.59 Gb, the depth was about 94.7 X, the average length of reads was 16.19 k, the number of contigs/scaffolds was 320, the Contig N50 was 1.53 Mb, the GC content was about 53.28%, and the total length of the genome sequence was 329.59 Mb. 2) Completeness: In the long reads, the insecta database of OrthoDB 10 was selected. The number of genes in the core gene set were 1,367. The number and proportion of complete single-copy core genes in the core gene set were 1202 and 87.93%, respectively. The number and proportion of complete multi-copy core genes in the core gene set were 121 and 8.85%, respectively. The number and proportion of complete core genes in the core gene set (including single-copy and multi-copy) were 1323 and 96.78%. The sequencing data were compared with the assembly results to evaluate the data coverage. In short reads, the number of clean reads was 164,272,072, the number of clean reads mapped to the reference genome was 155,286,329, and the percentage of clean reads mapped to the reference genome to all clean reads was 94.53%. In long reads, the number of clean reads was 1,580,153, the number of clean reads mapped to the reference genome was 1,532,715, and the percentage of clean reads mapped to the reference genome to all clean reads was 97.00%. 3) Correctness: CEGMA (Core Eukaryotic Genes Mapping Approach) evaluation is to select conserved genes (458 genes) existing in eukaryotic model organisms to form a core gene library, and to evaluate the assembled genome with software such as tblastn to evaluate the correctness of the assembled genome. The number of conserved genes contained in the assembled genome was 452, accounting for 98.69% of the 458 conserved genes. The assembled genome contains 244 highly conserved genes, accounting for 98.39% of the 248 highly conserved genes. The short reads data were re-aligned and compared with the assembled genome. The alignment rate was 94.53%, the cover degree was 97.77%, and the average sequencing depth was 64 × ; The long reads data were remapped and compared with the assembled genome. The alignment rate was 97.00%, the cover degree was 99.99%, and the average sequencing depth was 64 × . Finally, we obtained a Thrips tabaci genome sequence with high contiguity, completeness and correctness.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by National Key R&D Program of China (2022YFD1400300), Biological Breeding-Major Projects (2023ZD04062), and Agricultural Science and Technology Innovation Program of Chinese Academy of Agricultural Sciences.

Author contributions

J.J., J.C., J.L. and X.Z. conceived the project; Y.G., C.X., X.Z., L.W., K.Z. and D.L. performed the experiments; Y.G., X.W. and M.X. performed the bioinformatic analyses; Y.G., H.H. and L.C. evaluated the results; Y.G. and J.J. wrote the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Code availability

All bioinformatics tools and software used in this study were acquired in public databases and executed in accordance with published bioinformatics tools manuals and protocols. The software version and parameters were described in the method without the use of specific code or scripts. No custom code was used.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Yue Gao, Jichao Ji.

Contributor Information

Jichao Ji, Email: hnnydxjc@163.com.

Xiangzhen Zhu, Email: zhuxiangzhen318@163.com.

Jinjie Cui, Email: aycuijinjie@163.com.

Junyu Luo, Email: luojunyu1818@126.com.

References

- 1.Li, X. et al. Population Genetic Diversity and Structure of Thrips tabaci (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) on Allium Hosts in China, Inferred From Mitochondrial COI Gene Sequences. Journal of Economic Entomology113, 1426–1435, 10.1093/jee/toaa001 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Komondy, L., Hoepting, C. A., Fuchs, M., Pethybridge, S. J. & Nault, B. Spatiotemporal Patterns of Iris Yellow Spot Virus and its Onion Thrips Vector, Thrips tabaci, in Transplanted and Seeded Onion Fields in New York. Plant Dis10.1094/pdis-05-23-0930-re (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wakil, W., Gulzar, S., Prager, S. M., Ghazanfar, M. U. & Shapiro-Ilan, D. I. Efficacy of entomopathogenic fungi, nematodes and spinetoram combinations for integrated management of Thrips tabaci. Pest Management Science79, 3227–3238, 10.1002/ps.7503 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iftikhar, R., Ghosh, A. & Pappu, H. R. Mitochondrial genetic diversity of Thrips tabaci (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) in onion growing regions of the United States. Journal of Economic Entomology116, 1025–1032, 10.1093/jee/toad039 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Loredo Varela, R. C. & Fail, J. Host Plant Association and Distribution of the Onion Thrips, Thrips tabaci Cryptic Species Complex. Insects13, 298 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Thrips tabaci (onion thrips). Vol. CABI Compendium (CABI, 2022).

- 7.Silva, R., Hereward, J. P., Walter, G. H., Wilson, L. J. & Furlong, M. J. Seasonal abundance of cotton thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae) across crop and non-crop vegetation in an Australian cotton producing region. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment256, 226–238, 10.1016/j.agee.2017.12.024 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diaz-Montano, J., Fuchs, M., Nault, B. A., Fail, J. & Shelton, A. M. Onion Thrips (Thysanoptera: Thripidae): A Global Pest of Increasing Concern in Onion. Journal of Economic Entomology104, 1–13, 10.1603/ec10269 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chatzivassiliou, E. K., Peters, D. & Katis, N. I. The Efficiency by Which Thrips tabaci Populations Transmit Tomato spotted wilt virus Depends on Their Host Preference and Reproductive Strategy. Phytopathology92, 603–609, 10.1094/phyto.2002.92.6.603 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rasoulpour, R. & Izadpanah, K. Characterisation of cineraria strain of Tomato yellow ring virus from Iran. Australasian Plant Pathology36, 286–294, 10.1071/AP07023 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hassani-Mehraban, A. et al. Alstroemeria yellow spot virus (AYSV): a new orthotospovirus species within a growing Eurasian clade. Archives of Virology164, 117–126, 10.1007/s00705-018-4027-z (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shelton, A. M. & North, R. C. Species Composition and Phenology of Thysanoptera within Field Crops Adjacent to Cabbage Fields. Environmental Entomology15, 513–519, 10.1093/ee/15.3.513 (1986). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Orosz, S., Éliás, D., Balog, E. & Tóth, F. Investigation of thysanoptera populations in Hungarian greenhouses. Acta Universitatis Sapientiae, Agriculture and Environment9, 140–158, 10.1515/ausae-2017-0013 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vierbergen, G. Thysanoptera intercepted in the Netherlands on plant products from Ethiopia, with description of two new species of the genus Thrips. Zootaxa3765, 269–278, 10.11646/zootaxa.3765.3.3 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Morishita, M. Pyrethroid-resistant onion thrips, Thrips tabaci Lindeman (Thysanoptera: Thripidae), infesting persimmon fruit. Applied Entomology and Zoology43, 25–31, 10.1303/aez.2008.25 (2008). [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aizawa, M., Watanabe, T., Kumano, A., Miyatake, T. & Sonoda, S. Cypermethrin resistance and reproductive types in onion thrips, Thrips tabaci (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). Journal of Pesticide Science41, 167–170, 10.1584/jpestics.D16-049 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Xu, C. et al. Chromosome level genome assembly of oriental armyworm Mythimna separata. Scientific Data10, 597, 10.1038/s41597-023-02506-3 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Celorio-Mancera, M. D. L. P. et al. Mechanisms of macroevolution: polyphagous plasticity in butterfly larvae revealed by RNA-Seq. Molecular Ecology22, 4884–4895, 10.1111/mec.12440 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pym, A. et al. Host plant adaptation in the polyphagous whitefly, Trialeurodes vaporariorum, is associated with transcriptional plasticity and altered sensitivity to insecticides. BMC Genomics20, 996, 10.1186/s12864-019-6397-3 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhou, C. S. et al. Transcriptional analysis of Bemisia tabaci MEAM1 cryptic species under the selection pressure of neonicotinoids imidacloprid, acetamiprid and thiamethoxam. BMC Genomics23, 15, 10.1186/s12864-021-08241-6 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yang, N. et al. Transcriptome profiling of the whitefly Bemisia tabaci reveals stage-specific gene expression signatures for thiamethoxam resistance. Insect molecular biology22, 485–496, 10.1111/imb.12038 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ma, L. et al. Chromosome-level genome assembly of bean flower thrips Megalurothrips usitatus (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). Scientific Data10, 252, 10.1038/s41597-023-02164-5 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hu, Q.-L., Ye, Z.-X., Zhuo, J.-C., Li, J.-M. & Zhang, C.-X. A chromosome-level genome assembly of Stenchaetothrips biformis and comparative genomic analysis highlights distinct host adaptations among thrips. Communications Biology6, 813, 10.1038/s42003-023-05187-1 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guo, S.-K. et al. Chromosome-level assembly of the melon thrips genome yields insights into evolution of a sap-sucking lifestyle and pesticide resistance. Molecular Ecology Resources20, 1110–1125, 10.1111/1755-0998.13189 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wakil, W. et al. Development of Insecticide Resistance in Field Populations of Onion Thrips, Thrips tabaci (Thysanoptera: Thripidae). Insects14, 376 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rao et al. A 3D Map of the Human Genome at Kilobase Resolution Reveals Principles of Chromatin Looping. Cell159, 1665–1680, 10.1016/j.cell.2014.11.021 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gordon, S. P. et al. Widespread Polycistronic Transcripts in Fungi Revealed by Single-Molecule mRNA Sequencing. PloS one10, e0132628, 10.1371/journal.pone.0132628 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Chen, S., Zhou, Y., Chen, Y. & Gu, J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics34, i884–i890, 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Altschul, S. F., Gish, W., Miller, W., Myers, E. W. & Lipman, D. J. Basic local alignment search tool. Journal of Molecular Biology215, 403–410, 10.1016/S0022-2836(05)80360-2 (1990). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li, R., Li, Y., Kristiansen, K. & Wang, J. SOAP: short oligonucleotide alignment program. Bioinformatics24, 713–714, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btn025 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Marçais, G. & Kingsford, C. A fast, lock-free approach for efficient parallel counting of occurrences of k-mers. Bioinformatics27, 764–770, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btr011 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ranallo-Benavidez, T. R., Jaron, K. S. & Schatz, M. C. GenomeScope 2.0 and Smudgeplot for reference-free profiling of polyploid genomes. Nature Communications11, 1432, 10.1038/s41467-020-14998-3 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Cheng, H., Concepcion, G. T., Feng, X., Zhang, H. & Li, H. Haplotype-resolved de novo assembly using phased assembly graphs with hifiasm. Nature Methods18, 170–175, 10.1038/s41592-020-01056-5 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guan, D. et al. Identifying and removing haplotypic duplication in primary genome assemblies. Bioinformatics36, 2896–2898, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btaa025 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Walker, B. J. et al. Pilon: An Integrated Tool for Comprehensive Microbial Variant Detection and Genome Assembly Improvement. PloS one9, e112963, 10.1371/journal.pone.0112963 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Vaser, R., Sović, I., Nagarajan, N. & Šikić, M. Fast and accurate de novo genome assembly from long uncorrected reads. Genome Res27, 737–746, 10.1101/gr.214270.116 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Li, H. & Durbin, R. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics25, 1754–1760, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Servant, N. et al. HiC-Pro: an optimized and flexible pipeline for Hi-C data processing. Genome Biology16, 259, 10.1186/s13059-015-0831-x (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burton, J. N. et al. Chromosome-scale scaffolding of de novo genome assemblies based on chromatin interactions. Nature Biotechnology31, 1119–1125, 10.1038/nbt.2727 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Flynn, J. M. et al. RepeatModeler2 for automated genomic discovery of transposable element families. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences117, 9451–9457, 10.1073/pnas.1921046117 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bao, Z. & Eddy, S. R. Automated de novo identification of repeat sequence families in sequenced genomes. Genome Res12, 1269–1276, 10.1101/gr.88502 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Price, A. L., Jones, N. C. & Pevzner, P. A. De novo identification of repeat families in large genomes. Bioinformatics21(Suppl 1), i351–358, 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti1018 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Xu, Z. & Wang, H. LTR_FINDER: an efficient tool for the prediction of full-length LTR retrotransposons. Nucleic Acids Research35, W265–W268, 10.1093/nar/gkm286 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ellinghaus, D., Kurtz, S. & Willhoeft, U. LTRharvest, an efficient and flexible software for de novo detection of LTR retrotransposons. BMC Bioinformatics9, 18, 10.1186/1471-2105-9-18 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ou, S. & Jiang, N. LTR_retriever: A Highly Accurate and Sensitive Program for Identification of Long Terminal Repeat Retrotransposons. Plant Physiology176, 1410–1422, 10.1104/pp.17.01310 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wheeler, T. J. et al. Dfam: a database of repetitive DNA based on profile hidden Markov models. Nucleic Acids Research41, D70–D82, 10.1093/nar/gks1265 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Tarailo-Graovac, M. & Chen, N. Using RepeatMasker to Identify Repetitive Elements in Genomic Sequences. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics25, 4.10.11–14.10.14, 10.1002/0471250953.bi0410s25 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Benson, G. Tandem repeats finder: a program to analyze DNA sequences. Nucleic Acids Research27, 573–580, 10.1093/nar/27.2.573 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Beier, S., Thiel, T., Münch, T., Scholz, U. & Mascher, M. MISA-web: a web server for microsatellite prediction. Bioinformatics33, 2583–2585, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btx198 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Lowe, T. M. & Eddy, S. R. tRNAscan-SE: A Program for Improved Detection of Transfer RNA Genes in Genomic Sequence. Nucleic Acids Research25, 955–964, 10.1093/nar/25.5.955 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Loman, T. A Novel Method for Predicting Ribosomal RNA Genes in Prokaryotic Genomes (2017).

- 52.Griffiths-Jones, S. et al. Rfam: annotating non-coding RNAs in complete genomes. Nucleic Acids Research33, D121–D124, 10.1093/nar/gki081 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Nawrocki, E. P. & Eddy, S. R. Infernal 1.1: 100-fold faster RNA homology searches. Bioinformatics29, 2933–2935, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt509 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Stanke, M. et al. AUGUSTUS: ab initio prediction of alternative transcripts. Nucleic Acids Research34, W435–W439, 10.1093/nar/gkl200 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Korf, I. Gene finding in novel genomes. BMC Bioinformatics5, 59, 10.1186/1471-2105-5-59 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Keilwagen, J. et al. Using intron position conservation for homology-based gene prediction. Nucleic Acids Research44, e89–e89, 10.1093/nar/gkw092 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Kim, D., Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nature Methods12, 357–360, 10.1038/nmeth.3317 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pertea, M. et al. StringTie enables improved reconstruction of a transcriptome from RNA-seq reads. Nature Biotechnology33, 290–295, 10.1038/nbt.3122 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Tang, S., Lomsadze, A. & Borodovsky, M. Identification of protein coding regions in RNA transcripts. Nucleic Acids Research43, e78–e78, 10.1093/nar/gkv227 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Haas, B. J. et al. Improving the Arabidopsis genome annotation using maximal transcript alignment assemblies. Nucleic Acids Research31, 5654–5666, 10.1093/nar/gkg770 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Grabherr, M. G. et al. Full-length transcriptome assembly from RNA-Seq data without a reference genome. Nature Biotechnology29, 644–652, 10.1038/nbt.1883 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Haas, B. J. et al. Automated eukaryotic gene structure annotation using EVidenceModeler and the Program to Assemble Spliced Alignments. Genome Biology9, R7, 10.1186/gb-2008-9-1-r7 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Simão, F. A., Waterhouse, R. M., Ioannidis, P., Kriventseva, E. V. & Zdobnov, E. M. BUSCO: assessing genome assembly and annotation completeness with single-copy orthologs. Bioinformatics31, 3210–3212, 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv351 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Huerta-Cepas, J. et al. eggNOG 5.0: a hierarchical, functionally and phylogenetically annotated orthology resource based on 5090 organisms and 2502 viruses. Nucleic Acids Res47, D309–d314, 10.1093/nar/gky1085 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Boeckmann, B. et al. The SWISS-PROT protein knowledgebase and its supplement TrEMBL in 2003. Nucleic Acids Res31, 365–370, 10.1093/nar/gkg095 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Kanehisa, M., Sato, Y., Kawashima, M., Furumichi, M. & Tanabe, M. KEGG as a reference resource for gene and protein annotation. Nucleic Acids Res44, D457–462, 10.1093/nar/gkv1070 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Finn, R. D. et al. The Pfam protein families database. Nucleic Acids Research36, D281–D288, 10.1093/nar/gkm960 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Trapnell, C. et al. Transcript assembly and quantification by RNA-Seq reveals unannotated transcripts and isoform switching during cell differentiation. Nature Biotechnology28, 511–515, 10.1038/nbt.1621 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq. 2. Genome Biology15, 550, 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Köster, J., Dijkstra, L. J., Marschall, T. & Schönhuth, A. Varlociraptor: enhancing sensitivity and controlling false discovery rate in somatic indel discovery. Genome Biology21, 98, 10.1186/s13059-020-01993-6 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.NCBI Sequence Read Archive.https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR26448191 (2024).

- 72.NCBI Sequence Read Archive.https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR26417911 (2024).

- 73.NCBI Sequence Read Archive.https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR26401083 (2024).

- 74.NCBI Sequence Read Archivehttps://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR26404855 (2024).

- 75.NCBI Assembly.https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_040581495.1 (2024).

- 76.Gao, Y. Genome annotation of Thrips tabaci. figshare10.6084/m9.figshare.24408181.v1 (2023).

- 77.Li, H. Minimap2: pairwise alignment for nucleotide sequences. Bioinformatics34, 3094–3100, 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty191 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Citations

- NCBI Sequence Read Archive.https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR26448191 (2024).

- NCBI Sequence Read Archive.https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR26417911 (2024).

- NCBI Sequence Read Archive.https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR26401083 (2024).

- NCBI Sequence Read Archivehttps://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.sra:SRR26404855 (2024).

- NCBI Assembly.https://identifiers.org/ncbi/insdc.gca:GCA_040581495.1 (2024).

- Gao, Y. Genome annotation of Thrips tabaci. figshare10.6084/m9.figshare.24408181.v1 (2023).

Data Availability Statement

All bioinformatics tools and software used in this study were acquired in public databases and executed in accordance with published bioinformatics tools manuals and protocols. The software version and parameters were described in the method without the use of specific code or scripts. No custom code was used.