Abstract

Neurofibromas, in association with NF-1, can undergo a malignant transformation, giving rise to Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours (MPNSTs), a relatively rare entity. Clinically, it presents with non-specific symptoms like pain and numbness, distinguishing it from other nerve lesions difficult. There is a lack of data on the occurrence of MPNST in NF-1 in children and adults, and distant metastasis to the brain and bones is reported only in a few cases. In this case report, we present the unusual presentation of MPNST with metastasis to the proximal femur and liver in a patient with NF-1 and its management. Patients and clinicians should be made aware of the relatively high risk of MPNST in NF-1, which is characterized by pain and rapid growth, and regular follow-up is needed for NF-1 patients for early diagnosis of malignant transformation. So, this case report is presented to enhance the understanding and awareness regarding this rare presentation.

Keywords: Nerve sheath tumour, pathological fracture, bone metastasis, neurofibromatosis

Introduction

Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) is an autosomal dominant hereditary disorder affecting 1 in 3,000 newborns [1]. The disorder principally affects tissues derived from the ectoderm and mesoectoderm. It predominantly involves the skin, subcutaneous tissues, peripheral nerves, and the skeletal system. It is typified by cafe-au-lait spots, Lisch nodules, axillary freckling, optic gliomas, and peripheral neurofibromas. Amongst the skeletal manifestations, scoliosis and congenital pseudoarthrosis of the tibia are notable. Furthermore, intraosseous cystic lesions and periosteal bone proliferation may also be seen.

About 2-5% of neurofibromas can undergo a malignant transformation in association with NF-1, giving rise to Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours (MPNSTs) [2]. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours (MPNSTs) are a relatively rare but noteworthy group of soft tissue sarcomas, representing around 5-10% of all cases in this category [3]. Although the age of onset for MPNSTs is generally between 30 and 50 years, they can occur ten years earlier in patients with NF-1. However, MPNSTs are rare before adolescence, even in NF-1 [4]. Typical locations of these tumours are the proximal extremities, trunk, head, and neck regions. Clinically, it presents with non-specific symptoms like pain and numbness, making it challenging to distinguish it from other nerve lesions. As a result, the diagnosis and treatment of MPNSTs remain complex and often require a multidisciplinary approach. The histopathological examination may show characteristic hypo- and hyper-cellular areas with atypical spindle-shaped cells with nuclear pleomorphism, mitosis, necrosis, and a high proliferative index. Perivascular accentuation of tumor cells around blood vessels is also seen [5]. S-100 is regarded as the best marker for MPNST and is positive in about 50%-90% of the tumors [6]. MPNST is usually associated with poor prognosis and has limited treatment options [7]. Surgery should aim for complete lesion removal with tumor-free margins [8]. Adjuvant radiotherapy is recommended for intermediate- to high-grade lesions and low-grade tumors after marginal excision. Chemotherapy for adult soft tissue sarcomas, including MPNST, has limited efficacy, with partial response rates around 25-30% [9]. Patients with distant metastasis are usually given chemotherapy and palliative treatment [9]. Even with the progression in sarcoma management, the prognosis of MPNSTs is generally grave. In the literature, there is a paucity of data on the occurrence of MPNST in NF-1 in children and adults. Moreover, distant metastasis to the brain and bones is reported only in a few cases, adding further intricacy to managing this condition. To the best of our knowledge, only a few cases are reported of MPNST in NF-1 patients presenting as pathological fracture of the proximal femur with liver metastasis. So, we are reporting this case to enhance the understanding and awareness regarding this rare presentation.

Case summary

A 54-year-old female with a documented medical history of Neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF-1) arrived at the emergency department for injury to her left hip following a trivial fall. She presented to us after a week of injury. Examination revealed multiple neurofibromas all over her body, with numerous café au lait spots on the trunk (Figure 1). The radiograph showed a pathological fracture of the left proximal femur with a lytic, expansile lesion in the intertrochanteric region along with thinning of the cortex with the absence of periosteal reaction (Figure 2). Additional imaging, including CT and MRI findings, supported the plain radiographic evaluation. MR Imaging showed heterogeneously enhancing altered signal intensity lesion in the meta-diaphyseal region of the left proximal femur with the expansion of medullary cavity and thinning of cortex with pathological fracture in the intertrochanteric region with peripheral enhancing collection adjacent to lesser trochanter and muscle edema (Figure 3). USG of the abdomen revealed metastasis to the liver. The patient was managed with fixation of the fracture with the proximal femoral nail (Figure 4). The reaming material (curetted tissue) was sent for biopsy and cytology. Histopathological work-up from elbow swelling, reamed material (curetted tissue) from the proximal femur, and liver lesion revealed hyper and hypocellular areas of spindle-shaped cells with the formation of sheets and whorls at places, and thus a final diagnosis of MPNST was made. The tumour cells showed S-100 positivity. After the histopathological confirmation of MPNST, the adjuvant chemotherapy using a combination of Ifosfamide and Doxorubicin was given to the patient. Doxorubicin 20 mg/m2 and Ifosfomide 3 g/m2 on days 1, 2, and 3 and were repeated after 21 days for four cycles in adjuvant chemotherapy. The patient could walk with the help of a walker and was followed up for 1 year, during which no signs of recurrence were found. However, she was lost to follow, and the course of her disease could not be studied further.

Figure 1.

Clinical photograph of patient showing multiple neurofibromas over the back.

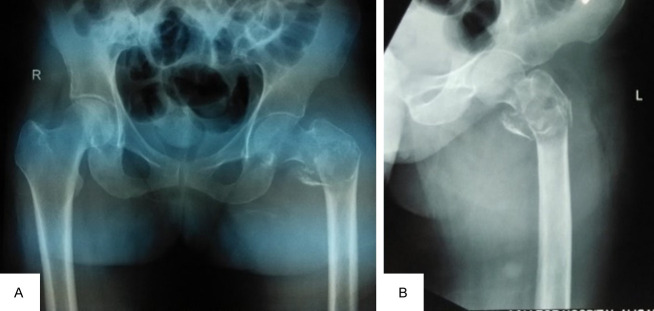

Figure 2.

The Plain radiograph showed a pathological fracture of the left proximal femur with a lytic, expansile lesion in the intertrochanteric region along with thinning of the cortex with the absence of periosteal reaction. AP View (A), Lateral view (B).

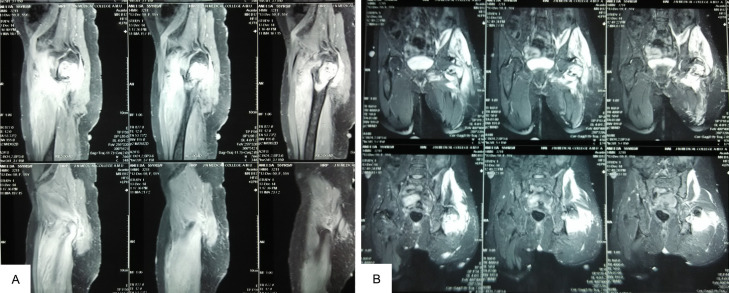

Figure 3.

MR imaging showing expansion of the medullary cavity and thinning of the cortex with a pathological fracture in the intertrochanteric region (A). Heterogenously enhancing altered signal intensity lesion in the proximal meta-diaphyseal region of the left proximal femur with peripherally enhancing collection adjacent to lesser trochanter and muscle edema (B).

Figure 4.

Post-operative plain radiograph after fixation of the fracture with PFN.

Discussion

MPNSTs, also documented as malignant schwannoma, neurofibrosarcoma, and neurogenic sarcoma, display a high level of aggressiveness, accounting for 5%-10% of all soft tissue sarcomas. American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC) is a commonly used staging system for these tumours. Our patient was classified as stage IV according to the AJCC system, as the patient presented with distant metastasis to the liver and proximal femur. The established risk factors for MPNSTs are neurofibromatosis (NF) and prior radiation exposure [3,5]. Although our patient had no history of radiation exposure, but had neurofibromatosis type-1 (NF-1). Malignant transformation of neurofibromas is predominantly associated with NF-1 in 75% of patients, as was seen in our patient, resulting in a reported 5-year survival rate of just 15% [2,6].

The literature contains several case reports detailing uncommon locations of MPNST linked to NF, such as the oral cavity [2], cervical vagus nerve [10], omentum [11], and chest wall [5]. Poor prognosis is associated with distant metastasis and frequent local recurrence. There are limited references describing bone and brain as metastatic sites. This particular case is noteworthy due to the patient’s presentation with a pathological fracture of the proximal femur, given her known history of NF-1. The well-defined lytic lesion in the intertrochanteric region of the femur, as observed on the plain radiograph of the hip, is highly atypical in its nature and presentation. When considering lytic lesions causing pathological fractures in older individuals, the differential diagnosis typically includes metastasis, multiple myeloma, and lymphoma.

From a histopathological perspective, MPNSTs exhibit distinctive features, including both hypo- and hyper-cellular regions, containing atypical spindle-shaped cells that display nuclear pleomorphism, frequent mitosis, necrosis, and a notably high rate of cell proliferation. Another distinguishing hallmark is the perivascular clustering of tumour cells around blood vessels [9]. In our case, characteristic histopathological features and positive S-100 staining confirm the malignant transformation of neurofibroma located over her elbow, leading to the development of MPNST. A similar morphological pattern was observed in the histopathological examination of the femur lesion, and a positive result for S-100 further confirms the metastatic MPNST. S-100 is traditionally considered the most reliable marker for MPNST, exhibiting positivity in approximately 50%-90% of these tumours [10]. CD56 and protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5) are considered sensitive markers for peripheral nerve sheath tumours, although their sensitivity does not equate to specificity for MPNSTs [10,11]. The liver fine-needle aspiration cytology (FNAC) revealed the presence of malignant spindle cells scattered amidst the normal hepatocytes. This discovery provides additional confirmation for the diagnosis and highlights the liver as an uncommon site for metastasis in cases of MPNST. MPNST is commonly linked to an unfavorable outlook, and in most cases, treatment options are limited. The primary cause of this bleak prognosis stems from the high occurrence of local recurrence and distant metastasis [12]. Patients who present with distant metastasis typically receive chemotherapy and palliative care to manage their condition. Our follow-up period was short as the patient did not survive for long after palliative treatment. Studies encompassing more patients with longer follow up is recommended to know more about its clinical presentation and natural history to make an early diagnosis and propose a specific treatment protocol.

Conclusion

Malignant transformation of neurofibroma is rare and is usually associated with NF-1. Patients with NF-1 should be made aware of the relatively high risk of MPNST, characterized by pain and rapid growth, and they should have easy access to specialist advice if these symptoms emerge and regular follow-up is needed for NF-1 patients for early diagnosis of malignant transformation. The possibility of bone metastasis should always be kept in mind.

Disclosure of conflict of interest

None.

Abbreviations

- MPNSTs

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours

- AJCC

American Joint Committee on Cancer

- NF-1

Neurofibromatosis type-1

- FNAC

Fine-needle aspiration cytology

References

- 1.Huson SM, Harper PS, Compston DA. Von Recklinghausen neurofibromatosis. A clinical and population study in south-east Wales. Brain. 1988;111:1355–1381. doi: 10.1093/brain/111.6.1355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Oztürk O, Tutkun A. A case report of a malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the oral cavity in neurofibromatosis type 1. Case Rep Otolaryngol. 2012;2012:936735. doi: 10.1155/2012/936735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wong KB, Chan SA. A case report of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour (MPNST) which present as an acute traumatic sciatic neuropathy. Int J Clin Case Rep. 2014;4:1–4. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yao C, Zhou H, Dong Y, Alhaskawi A, Hasan Abdullah Ezzi S, Wang Z, Lai J, Goutham Kota V, Hasan Abdulla Hasan Abdulla M, Lu H. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: latest concepts in disease pathogenesis and clinical management. Cancers (Basel) 2023;15:1077. doi: 10.3390/cancers15041077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ducatman BS, Scheithauer BW, Piepgras DG, Reiman HM, Ilstrup DM. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors. A clinicopathologic study of 120 cases. Cancer. 1986;57:2006–21. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19860515)57:10<2006::aid-cncr2820571022>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kosmas C, Tsakonas G, Evgenidi K, Gassiamis A, Savva L, Mylonakis N, Karabelis A. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor in neurobifromatosis type-1: two case reports. Cases J. 2009;2:7612. doi: 10.4076/1757-1626-2-7612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gupta A, Bansal S, Bhagat S, Bahl A. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour of the cervical vagus nerve in a neurofibromatosis type 1 patient - An unusual presentation. Online J Health Allied Scs. 2010;9:10. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miguchi M, Takakura Y, Egi H, Hinoi T, Adachi T, Kawaguchi Y, Shinomura M, Tokunaga M, Okajima M, Ohdan H. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor arising from the greater omentum: case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2011;9:33. doi: 10.1186/1477-7819-9-33. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hsu CC, Huang TW, Hsu JY, Shin N, Chang H. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor of the chest wall associated with neurofibromatosis: a case report. J Thorac Dis. 2013;5:E78–82. doi: 10.3978/j.issn.2072-1439.2013.05.12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Guo A, Liu A, Wei L, Song X. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors: differentiation patterns and immunohistochemical features - A mini-review and our new findings. J Cancer. 2012;3:303–9. doi: 10.7150/jca.4179. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Campbell LK, Thomas JR, Lamps LW, Smoller BR, Folpe AL. Protein gene product 9.5 (PGP 9.5) is not a specific marker of neural and nerve sheath tumors: an immunohistochemical study of 95 mesenchymal neoplasms. Mod Pathol. 2003;16:963–9. doi: 10.1097/01.MP.0000087088.88280.B0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Friedrich RE, Hartmann M, Mautner VF. Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumors (MPNST) in NF1-affected children. Anticancer Res. 2007;27:1957–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]