Abstract

Suprascapular nerve (SSN) entrapment is a rare but significant cause of posterior shoulder pain and weakness. Compression of the nerve at the level of the spinoglenoid notch leads to weakness and atrophy of the infraspinatus. A detailed history and physical examination along with appropriate workup are paramount to arrive at this diagnosis. Surgical decompression is indicated in cases refractory to conservative management. In this Technical Note, we describe our technique for open decompression of the SSN at the spinoglenoid notch. This approach permits direct visualization of the SSN and allows for a safe, reliable, and thorough decompression.

Technique Video

Suprascapular nerve (SSN) entrapment is a relatively uncommon but potentially debilitating cause of shoulder pain and dysfunction.1, 2, 3 The SSN has a tortuous course from the neck to the posterior shoulder but is most vulnerable to compression at the suprascapular and spinoglenoid notches.4 Patients with SSN neuropathy usually complain of a dull, aching pain in the posterior and lateral aspects of the shoulder.5 When the nerve is entrapped at the suprascapular notch, patients present with weakness and atrophy of both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus.1 With entrapment at the spinoglenoid notch, these symptoms are isolated to the infraspinatus.6 A variety of potential causes of compression have been described, including anomalous transverse scapular ligaments, ganglion cysts, abnormal bony morphology, direct trauma, and traction injury.7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13

There are sparse data regarding treatment options to guide surgeons definitively. Although nonoperative treatment is a reasonable initial option, surgical decompression is considered to be indicated in cases refractory to conservative management.14 The surgical approach is dictated by the site of nerve compression. Regarding the spinoglenoid notch, both open and arthroscopic techniques have been described, with no single technique showing obvious superiority.15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21 The open approach has the advantage of direct visualization of the nerve and the ability to completely excise large paralabral cysts. Arthroscopic techniques avoid the potential morbidity of an open approach and afford the surgeon the ability to address concomitant intra-articular pathology. In this Technical Note, we describe our preoperative evaluation, surgical technique, and postoperative rehabilitation for a safe and reliable open SSN decompression at the spinoglenoid notch (Video 1).

Preoperative Evaluation

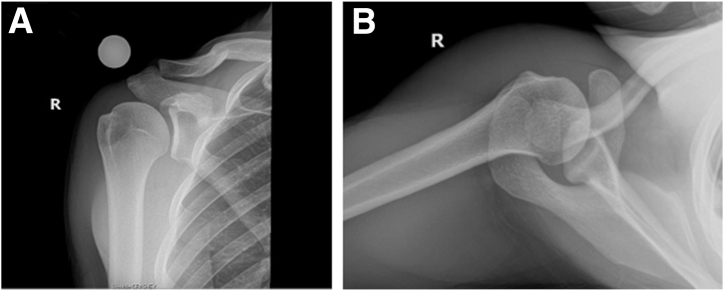

The initial workup for the patient with suspected SSN entrapment should include a thorough history of symptoms and activity level. Of note, participation in volleyball has been found to be a risk factor.13 Inspection may reveal atrophy of the supraspinatus or infraspinatus.22 Active and passive range of motion (ROM) as well as strength testing should be conducted in all patients. The supraspinatus is primarily responsible for abduction, whereas the infraspinatus acts as an external rotator of the shoulder in adduction. Although special attention is paid to the rotator cuff muscles, a thorough neurovascular examination is critical to ruling out more proximal injuries or involvement of the brachial plexus (e.g., Parsonage-Turner syndrome).1 Radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging scans are both helpful in determining whether a traumatic mechanism or space-occupying lesion may be responsible for the patient’s symptoms (Fig 1). Magnetic resonance imaging scans have added utility in assessing for atrophy of the rotator cuff, tracing out the course of the nerve, and identifying any concomitant shoulder pathology. When physical examination and imaging findings do not reveal a clear focus of entrapment, electromyography and/or nerve conduction velocity studies can aid in localizing the site of compression and confirming the diagnosis—especially by ruling out Parsonage-Turner syndrome.1 However, the results of electrodiagnostic testing can lead to false-negative or -positive findings.23,24

Fig 1.

Preoperative radiographs of right (R) shoulder showing no obvious osseous abnormalities with well-maintained joint space on both Grashey (A) and axillary (B) views.

Surgical Technique

Positioning

A regional block is performed in the preoperative area, followed by induction of laryngeal mask airway anesthesia. The patient is then placed in the lateral decubitus position and secured by a bean bag, with padding of the bony prominences, including the ankles and knees. An axillary roll is positioned underneath the patient at the level of the nipples. The upper extremity is then prepared and draped in the usual fashion, ensuring that the entirety of the posterior shoulder and operative limb is draped free. A sterile Mayo stand is placed on the far side of the operating room table to assist with placing the arm in forward flexion for the duration of the surgical procedure.

Technique

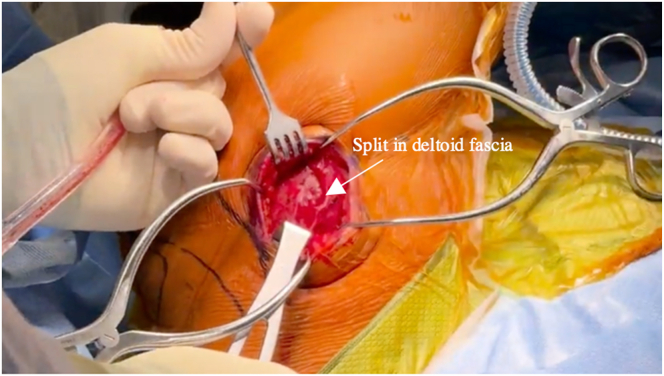

The borders of the acromion, scapular spine, and clavicle are drawn with a skin marker. The anticipated course of the axillary nerve (approximately 4.5-8 cm from the acromion) is drawn. Along a line that connects the Neviaser portal (medial aspect of the acromion) to the posterior axillary fold, a 6- to 8-cm posterior skin incision is made, extending distally from the scapular spine, in Langer lines of skin tension (Fig 2). Full-thickness skin flaps are raised with a No. 10 blade, followed by deeper dissection and hemostasis using electrocautery. Next, the deltoid fascia is split in line with the muscle fibers, proximal to the axillary nerve, and centered over the spinoglenoid with Metzenbaum scissors (Fig 3). The fibers of the deltoid run obliquely to the orientation of the skin incision. No deltoid muscle is detached from the acromion.

Fig 2.

The patient is placed in the lateral decubitus position. A sterile Mayo stand is placed on the far side of the operating room table to assist with placing the right arm in forward flexion and abduction. The borders of the acromion, scapular spine, and clavicle are drawn with a skin marker, along with the proposed 6- to 8-cm incision extending distally from the scapular spine along a line that connects the Neviaser portal (medial aspect of the acromion) to the posterior axillary fold.

Fig 3.

The right shoulder deltoid fascia is split in line with the underlying deltoid muscle fibers. The fibers of the deltoid run obliquely to the orientation of the skin incision. No deltoid muscle is detached from the acromion.

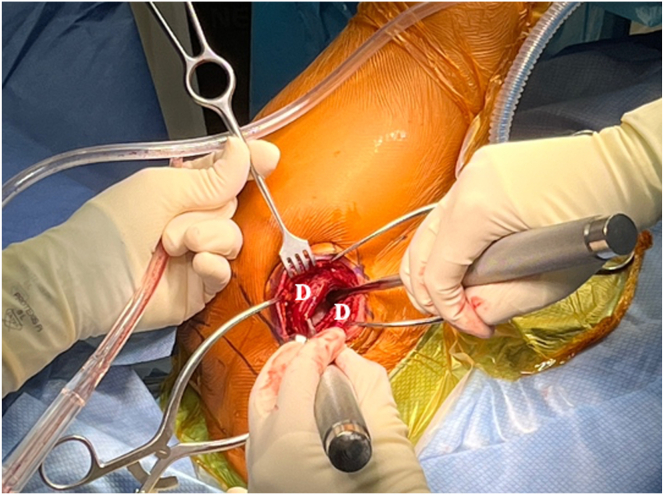

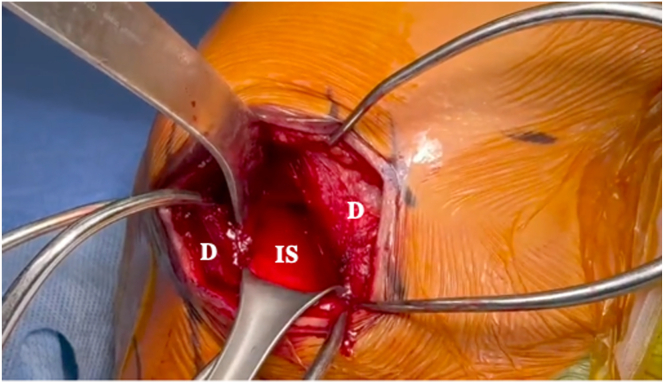

Through the distal aspect of the deltoid split, exiting the quadrilateral space, the axillary nerve is easily palpated, and care is taken not to pull traction against the nerve or extend the split distally. Further blunt dissection is performed proximal to the nerve with 2 Cobb elevators to separate the fibers of the deltoid (Fig 4). After placement of a Gelpi retractor deep to the deltoid fascia, the axillary nerve is again identified via palpation exiting the quadrilateral space. The deep deltoid fascia is incised to expose the infraspinatus (Fig 5). A blunt Hohmann retractor is placed over the humeral head into the subacromial space, and the infraspinatus is gently reflected inferiorly off the scapular spine to expose the underlying spinoglenoid notch. A Richardson retractor is used to retract the infraspinatus inferolaterally to assist with visualization of the notch, with care taken to avoid excessive traction on the infraspinatus and, by extension, the SSN. The SSN is identified within the spinoglenoid notch, and the spinoglenoid ligament is released, along with any additional adherent fascial bands (Figs 6 and 7). Great care is taken to avoid iatrogenic injury to the SSN or its associated vessels. Once decompression is achieved, we confirm that the nerve is free and mobile throughout its course in the notch with a 90° hemostat. The wound is copiously irrigated, and the infraspinatus is allowed to rest back in its fossa. The deltoid split is closed with No. 0 Vicryl (Ethicon) followed by No. 3-0 Vicryl and No. 3-0 Monocryl (Ethicon) for superficial skin layers. Pearls and pitfalls of our technique are presented in Table 1, and advantages and limitations are listed in Table 2.

Fig 4.

The skin and fascia of the right shoulder are retracted with Gelpi retractors while the deltoid (D) muscle fibers are bluntly dissected with 2 Cobb elevators to expose the underlying infraspinatus.

Fig 5.

The deep deltoid (D) fascia of the right shoulder is incised, and a blunt Hohmann retractor is placed over the humeral head into the subacromial space to expose the infraspinatus (IS).

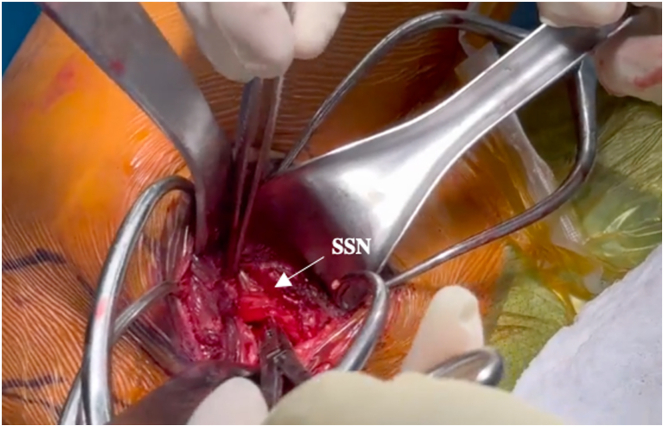

Fig 6.

The infraspinatus of the right shoulder is gently reflected inferiorly off the scapular spine to expose the underlying spinoglenoid notch. A Richardson retractor is used to retract the infraspinatus inferolaterally to assist with visualization of the notch, with care taken to avoid excessive traction on the infraspinatus and, by extension, the suprascapular nerve (SSN). The SSN is identified within the spinoglenoid notch, and the spinoglenoid ligament is released, along with any additional adherent fascial bands.

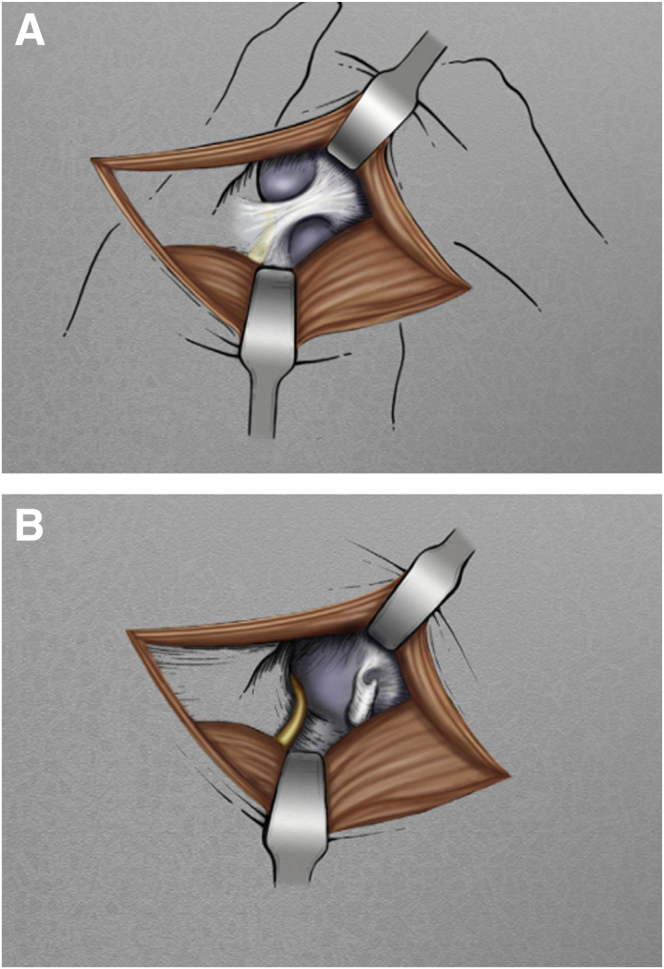

Fig 7.

Illustration of the right shoulder with the spinoglenoid ligament before (A) and after (B) its release. The spinoglenoid ligament is a fascial veil-like structure overlying the suprascapular nerve that extends from the lateral edge of the scapular spine to the posterior capsule of the shoulder.

Table 1.

Pearls and Pitfalls

| Pearls |

| The ideal indication for our open technique is suprascapular neuropathy at the spinoglenoid notch without an associated SLAP tear or paralabral cyst and with compression due to fibrous bands. |

| Careful identification of relevant bony landmarks is paramount to making an incision in the correct location and orientation. |

| Blunt dissection over the suprascapular nerve helps to avoid iatrogenic injury to the suprascapular nerve and its accompanying vasculature. |

| The inferior border of the spine of the scapula leads easily to the spinoglenoid notch. |

| Pitfalls |

| The axillary nerve can be injured on the approach or with overly exuberant traction if not identified and protected. |

| A venous plexus surrounds the suprascapular nerve. Careful hemostasis is required to avoid inadvertent iatrogenic nerve injury while controlling bleeding. |

Table 2.

Advantages and Limitations

| Advantages |

| Open decompression permits direct visualization of the suprascapular nerve. |

| Open decompression allows for a more thorough release of the spinoglenoid ligament. |

| Open decompression allows removal of large spinoglenoid notch cysts. |

| Limitations |

| Intra-articular pathology is unable to be addressed through the described approach. |

| Arthroscopic decompression allows for a more minimally invasive approach. |

Postoperative Care

The patient is placed in a simple sling with immediate initiation of physical therapy for gentle stretching and ROM. The patient is seen 2 weeks postoperatively to inspect the incision and to assess strength and ROM. At this visit, the sling is removed and the patient begins light strengthening. At 6 weeks, the patient progresses to full strengthening exercises without restriction.

Discussion

Suprascapular neuropathy is an often-overlooked cause of posterior shoulder pain and weakness. The location of entrapment in the nerve’s course through the posterior shoulder dictates the patient’s clinical picture.25 Although the nerve is most commonly compressed at the suprascapular notch, it can also be entrapped more distally at the spinoglenoid notch.26,27 This manifests as posterior shoulder pain with atrophy of the infraspinatus and weakness in external rotation. Despite being most commonly reported to be due to a ganglion cyst,28, 29, 30 compression at the spinoglenoid notch has several possible causes.20 The spinoglenoid ligament has been identified as a source of significant compression in several studies.31, 32, 33 Athletes who participate regularly in overhead sports, such as volleyball, are more susceptible to the development of suprascapular neuropathy.34, 35, 36 In these patients, it is proposed that this neuropathy is most likely caused by neurapraxia caused by repetitive hitting.

High-quality studies evaluating the outcomes of various surgical techniques are lacking given the relative rarity of this pathology. A recent meta-analysis showed encouraging patient-reported outcomes and rates of return to sport for SSN decompression broadly.24 However, there are considerably fewer data on isolated decompression of the spinoglenoid notch. Mall et al.20 reported improvement in strength in 29 of 29 patients who underwent open spinoglenoid notch decompression. Arthroscopic techniques have also been shown to be an effective means for decompression of the SSN. These techniques have the advantage of being more minimally invasive, which could theoretically lead to a less morbid approach. The senior author (G.G.) frequently performs arthroscopic nerve decompression but prefers the open approach in particular situations. Arthroscopic decompression of the SSN is preferred when the site of compression is the suprascapular notch, using the method described by Lafosse et al.16 Arthroscopic indirect decompression of spinoglenoid notch cysts followed by SLAP repair is preferred in cases of compression at the spinoglenoid notch with small- or medium-sized paralabral cysts (<2 cm). With larger cysts that can often be walled off from the joint, the senior author believes the entire cyst should be excised—in this case, the open technique described in this article is very effective. However, if a concomitant SLAP tear is present, this should also be addressed to minimize the risk of recurrence. The ideal indication for our open technique is a case in which no cyst or SLAP tear is present and fibrous bands are the source of compression. These can be dissected arthroscopically, as described by Iannotti and Ramsey,29 but the open technique is simple, is reproducible, and—because all muscles are split in line with fibers or working in intermuscular planes—has a very rapid recovery with minimal morbidity.

As shown by the described technique, an open approach provides a safe, reliable, and thorough means to decompress the SSN at the spinoglenoid notch. Further studies should focus on comparing the outcomes of open and arthroscopic techniques in cases of isolated spinoglenoid notch entrapment.

Disclosures

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: G.P.N. reports board membership with American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons; reports a consulting or advisory relationship with Wright Medical Group; and receives speaking and lecture fees from Arthrosurface. G.E.G. reports board membership with American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons; reports a consulting or advisory relationship with Bioventus, Tornier, and MiTek; receives funding grants from Arthrex and Zimmer; and owns patents with royalties paid to Tornier and DJ Orthopaedics. All other authors (W.E.H., B.K., J.S., S.G., T.W.) declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Supplementary Data

Technique for open right posterior shoulder suprascapular nerve decompression at spinoglenoid notch, highlighting pearls and pitfalls for procedure, as well as preoperative evaluation and workup.

References

- 1.Piasecki D.P., Romeo A.A., Bach B.R., Nicholson G.P. Suprascapular neuropathy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2009;17:665–676. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200911000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Post M. Diagnosis and treatment of suprascapular nerve entrapment. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1999;368:92–100. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zehetgruber H., Noske H., Lang T., Wurnig C. Suprascapular nerve entrapment. A meta-analysis. Int Orthop. 2002;26:339–343. doi: 10.1007/s00264-002-0392-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Romeo A.A., Rotenberg D.D., Bach B.R., Jr. Suprascapular neuropathy. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 1999;7:358–367. doi: 10.5435/00124635-199911000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Martin S.D., Warren R.F., Martin T.L., Kennedy K., O'Brien S.J., Wickiewicz T.L. Suprascapular neuropathy. Results of non-operative treatment. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1997;79:1159–1165. doi: 10.2106/00004623-199708000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aiello I., Serra G., Traina G.C., Tugnoli V. Entrapment of the suprascapular nerve at the spinoglenoid notch. Ann Neurol. 1982;12:314–316. doi: 10.1002/ana.410120320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hirayama T., Takemitsu Y. Compression of the suprascapular nerve by a ganglion at the suprascapular notch. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1981;155:95–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Neviaser T.J., Ain B.R., Neviaser R.J. Suprascapular nerve denervation secondary to attenuation by a ganglionic cyst. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1986;68:627–628. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ticker J.B., Djurasovic M., Strauch R.J., et al. The incidence of ganglion cysts and other variations in anatomy along the course of the suprascapular nerve. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:472–478. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(98)90197-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rengachary S.S., Burr D., Lucas S., Brackett C.E. Suprascapular entrapment neuropathy: A clinical, anatomical, and comparative study. Part 3: Comparative study. Neurosurgery. 1979;5:452–455. doi: 10.1227/00006123-197910000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.McIlveen S.J., Duralde X.A., D'Alessandro D.F., Bigliani L.U. Isolated nerve injuries about the shoulder. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1994;306:54–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yoon T.N., Grabois M., Guillen M. Suprascapular nerve injury following trauma to the shoulder. J Trauma. 1981;21:652–655. doi: 10.1097/00005373-198108000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandow M.J., Ilic J. Suprascapular nerve rotator cuff compression syndrome in volleyball players. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:516–521. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(98)90205-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Antoniou J., Tae S.K., Williams G.R., Bird S., Ramsey M.L., Iannotti J.P. Suprascapular neuropathy. Variability in the diagnosis, treatment, and outcome. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2001;386:131–138. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhatia S., Chalmers P.N., Yanke A.B., Romeo A.A., Verma N.N. Arthroscopic suprascapular nerve decompression: Transarticular and subacromial approach. Arthrosc Tech. 2012;1:e187–e192. doi: 10.1016/j.eats.2012.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lafosse L., Tomasi A., Corbett S., Baier G., Willems K., Gobezie R. Arthroscopic release of suprascapular nerve entrapment at the suprascapular notch: Technique and preliminary results. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Westerheide K.J., Dopirak R.M., Karzel R.P., Snyder S.J. Suprascapular nerve palsy secondary to spinoglenoid cysts: Results of arthroscopic treatment. Arthroscopy. 2006;22:721–727. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2006.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen A.L., Ong B.C., Rose D.J. Arthroscopic management of spinoglenoid cysts associated with SLAP lesions and suprascapular neuropathy. Arthroscopy. 2003;19:E15–E21. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(03)00381-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ghodadra N., Nho S.J., Verma N.N., et al. Arthroscopic decompression of the suprascapular nerve at the spinoglenoid notch and suprascapular notch through the subacromial space. Arthroscopy. 2009;25:439–445. doi: 10.1016/j.arthro.2008.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mall N.A., Hammond J.E., Lenart B.A., Enriquez D.J., Twigg S.L., Nicholson G.P. Suprascapular nerve entrapment isolated to the spinoglenoid notch: Surgical technique and results of open decompression. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2013;22:e1–e8. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2013.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jerome T.J., Sabtharishi V., Sk T. Open surgical decompression for large multiloculated spinoglenoid notch ganglion cyst with suprascapular nerve neuropathy. Cureus. 2021;13 doi: 10.7759/cureus.13300. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Piatt B.E., Hawkins R.J., Fritz R.C., Ho C.P., Wolf E., Schickendantz M. Clinical evaluation and treatment of spinoglenoid notch ganglion cysts. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2002;11:600–604. doi: 10.1067/mse.2002.127094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ringel S.P., Treihaft M., Carry M., Fisher R., Jacobs P. Suprascapular neuropathy in pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 1990;18:80–86. doi: 10.1177/036354659001800113. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Momaya A.M., Kwapisz A., Choate W.S., et al. Clinical outcomes of suprascapular nerve decompression: A systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27:172–180. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2017.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bigliani L.U., Dalsey R.M., McCann P.D., April E.W. An anatomical study of the suprascapular nerve. Arthroscopy. 1990;6:301–305. doi: 10.1016/0749-8063(90)90060-q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kiss G., Kómár J. Suprascapular nerve compression at the spinoglenoid notch. Muscle Nerve. 1990;13:556–557. doi: 10.1002/mus.880130614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Henlin J.L., Rousselot J.P., Monnier G., Sevrin P., Bady B. [Suprascapular nerve entrapment at the spinoglenoid notch] Rev Neurol (Paris) 1992;148:362–367. [in French] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lichtenberg S., Magosch P., Habermeyer P. Compression of the suprascapular nerve by a ganglion cyst of the spinoglenoid notch: The arthroscopic solution. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc. 2004;12:72–79. doi: 10.1007/s00167-003-0443-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Iannotti J.P., Ramsey M.L. Arthroscopic decompression of a ganglion cyst causing suprascapular nerve compression. Arthroscopy. 1996;12:739–745. doi: 10.1016/s0749-8063(96)90180-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Moore T.P., Fritts H.M., Quick D.C., Buss D.D. Suprascapular nerve entrapment caused by supraglenoid cyst compression. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1997;6:455–462. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(97)70053-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Plancher K.D., Peterson R.K., Johnston J.C., Luke T.A. The spinoglenoid ligament. Anatomy, morphology, and histological findings. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2005;87:361–365. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.C.01533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ide J., Maeda S., Takagi K. Does the inferior transverse scapular ligament cause distal suprascapular nerve entrapment? An anatomic and morphologic study. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2003;12:253–255. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(02)00030-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Demirhan M., Imhoff A.B., Debski R.E., Patel P.R., Fu F.H., Woo S.L. The spinoglenoid ligament and its relationship to the suprascapular nerve. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 1998;7:238–243. doi: 10.1016/s1058-2746(98)90051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lajtai G., Pfirrmann C.W., Aitzetmüller G., Pirkl C., Gerber C., Jost B. The shoulders of professional beach volleyball players: High prevalence of infraspinatus muscle atrophy. Am J Sports Med. 2009;37:1375–1383. doi: 10.1177/0363546509333850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ferretti A., Cerullo G., Russo G. Suprascapular neuropathy in volleyball players. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1987;69:260–263. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ferretti A., De Carli A., Fontana M. Injury of the suprascapular nerve at the spinoglenoid notch. The natural history of infraspinatus atrophy in volleyball players. Am J Sports Med. 1998;26:759–763. doi: 10.1177/03635465980260060401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Technique for open right posterior shoulder suprascapular nerve decompression at spinoglenoid notch, highlighting pearls and pitfalls for procedure, as well as preoperative evaluation and workup.