Key Points

Question

What is the efficacy and safety of once-daily roflumilast cream, 0.15%, in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD)?

Findings

In 2 phase 3 randomized clinical trials of 1337 individuals with AD, significantly more patients treated with once-daily roflumilast cream, 0.15%, achieved Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis success at 4 weeks than patients treated with vehicle cream. Roflumilast was well tolerated with low rates of adverse events in both trials.

Meaning

An effective, well-tolerated, once-daily, nonsteroidal treatment like roflumilast cream, 0.15%, may address several unmet needs and substantially improve the treatment landscape for patients with AD.

Abstract

Importance

Safe, effective, and well-tolerated topical treatment options available for long-term use in patients with atopic dermatitis (AD) are limited and associated with low adherence rates.

Objective

To evaluate efficacy and safety of once-daily roflumilast cream, 0.15%, vs vehicle cream in patients with AD.

Design, Setting, and Participants

Two phase 3, randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled trials (Interventional Trial Evaluating Roflumilast Cream for the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis 1 and 2 [INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2]), included patients from sites in the US, Canada, and Poland. Participants were 6 years or older with mild to moderate AD based on Validated Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (assessed on a 5-point scale ranging from 0 [clear] to 4 [severe]).

Intervention

Patients were randomized 2:1 to receive roflumilast cream, 0.15%, or vehicle cream once daily for 4 weeks.

Main Outcomes and Measures

The primary efficacy end point was Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis success at week 4, defined as a score of 0 or 1 plus at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline. Secondary end points included Eczema Area and Severity Index and Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale. Safety and local tolerability were also evaluated.

Results

Among 1337 patients (654 patients in INTEGUMENT-1 and 683 patients in INTEGUMENT-2), the mean (SD) age was 27.7 (19.2) years, and 761 participants (56.9%) were female. The mean body surface area involved was 13.6% (SD = 11.6%; range, 3.0% to 88.0%). Significantly more patients treated with roflumilast than vehicle achieved the primary end point (INTEGUMENT-1: 32.0% vs 15.2%, respectively; P < .001; INTEGUMENT-2: 28.9% vs 12.0%, respectively; P < .001). At week 4, statistically significant differences favoring roflumilast also occurred for the achievement of at least 75% reduction in the Eczema Area and Severity Index (INTEGUMENT-1: 43.2% vs 22.0%, respectively; P < .001; INTEGUMENT-2: 42.0% vs 19.7%, respectively; P < .001). Roflumilast was well tolerated with low rates of treatment-emergent adverse events. At each time point, investigators noted no signs of irritation at the application site in 885 patients who were treated with roflumilast (≥95%), and 885 patients who were treated with roflumilast (90%) reported no or mild sensation at the application site.

Conclusions and Relevance

In 2 phase 3 trials enrolling adults and children, once-daily roflumilast cream, 0.15%, improved AD relative to vehicle cream, based on multiple efficacy end points, with favorable safety and tolerability.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifiers: NCT04773587, NCT04773600

Two randomized clinical trials evaluate the efficacy and safety of once-daily roflumilast cream, 0.15%, vs vehicle cream in patients with atopic dermatitis.

Introduction

Atopic dermatitis (AD) is a chronic relapsing inflammatory skin disease that presents across all age groups.1,2 The prevalence of AD in the US is up to 20% in children3 and 5% in adults.2 Symptoms of AD, including pruritus (the most reported and burdensome symptom) and pain,4,5 are associated with reduced quality of life and sleep disturbances.4,5,6

The affected areas of the skin in patients with AD are characterized by an inflammatory infiltrate with heterogeneous proinflammatory cytokine expression and dysregulated innate and adaptive immunity.7 Increased cyclic adenosine monophosphate phosphodiesterase (PDE) activity in mononuclear leukocytes may explain the immune dysregulation observed in patients with AD.8 In vitro and in vivo studies of PDE4 inhibitors in patients with AD demonstrated anti-inflammatory effects.9 Subsequently, clinical trials of the twice-daily topical PDE4 inhibitor, crisaborole, demonstrated safety and efficacy in patients with AD.10

Although the current therapeutic landscape for AD comprises topical steroidal and nonsteroidal medications, unmet treatment needs persist. First, crisaborole and the topical calcineurin inhibitor (TCI) tacrolimus are ointments, but many patients with skin diseases prefer creams over ointments.11 Second, adherence to treatment remains a major barrier to improvement in patients with inflammatory skin disorders such as AD12; twice-daily dosing of approved topical medications may contribute to this poor adherence.13 Third, the efficacy of currently available nonsteroidal medications is suboptimal: the TCI pimecrolimus14 is less effective than potent corticosteroids,15,16 and crisaborole has shown only modest efficacy.17 Lastly, several of these medications are associated with application-site reactions, including skin atrophy with steroids16,17 and application-site burning and pain with TCIs and crisaborole,15,18 and ruxolitinib cream has boxed warnings and a body surface area (BSA) maximum.15,18,19,20

Roflumilast cream, 0.3%, is a highly potent, once-daily topical PDE4 inhibitor approved to treat plaque psoriasis, including intertriginous psoriasis.21 Clinical trials have been conducted with topical roflumilast foam, 0.3%, to treat patients with plaque psoriasis of the scalp and body and seborrheic dermatitis, and roflumilast cream, 0.15%, and roflumilast cream, 0.05%, to treat patients with AD.22,23,24 Structural and computational biology assessments demonstrate that roflumilast more closely mimics cyclic adenosine monophosphate compared with other PDE4 inhibitors, resulting in high affinity for PDE4.25 Depending on the isoform tested, roflumilast demonstrated approximately 25-fold to more than 300-fold more potency than apremilast and crisaborole in vitro, the 2 other PDE4 inhibitors (oral or topical) approved for dermatologic conditions.26

A phase 2 proof-of-concept trial demonstrated once-daily roflumilast cream, 0.15%, and roflumilast cream, 0.05%, had favorable safety and tolerability profiles with the potential to be effective in treating mild to moderate AD.24 The phase 3 randomized clinical trials presented here (Interventional Trial Evaluating Roflumilast Cream for the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis 1 and 2 [INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2]) evaluated the efficacy and safety of roflumilast cream, 0.15%, applied once daily for 4 weeks in patients 6 years or older with mild to moderate AD.

Methods

Study Design and Participants

INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2 were identical, parallel-group, double-blind, vehicle-controlled randomized trials conducted at 65 and 88 centers, respectively, in the US, Canada, and Poland (see Supplement 1 for trial protocols and statistical analysis plans). The protocols were approved by the Advarra Institutional Review Board. The trials were conducted in accordance with the principles of the Tri-Council Policy Statement, the ethical principles in the Declaration of Helsinki,27 and the Good Clinical Practice guidelines of the International Council for Harmonisation.

All patients provided written informed consent/assent (guardians provided consent when applicable) before initiating trial-specific procedures. Patients eligible for inclusion were 6 years or older, had a history of AD (≥6 months for adults and ≥3 months for children and adolescents), and were in otherwise good health. At baseline, patients had to have an Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI)28 score of at least 5, Validated Investigator Global Assessment for AD (vIGA-AD; eTable 1 in Supplement 2)29 score of 2 (mild) or 3 (moderate), and AD involving at least 3% BSA with no upper limit.

Trial Treatments

Roflumilast, 0.15%, was formulated as an emollient, water-based, moisturizing cream.21,24 The cream did not contain fragrances, propylene glycol, isopropyl alcohol, ethanol, or formaldehyde-releasing preservatives.21,24 The vehicle cream was identical to roflumilast cream excluding roflumilast. Patients received 45-gram tubes of their assigned treatment (roflumilast cream, 0.15%, or vehicle cream). Investigators used the percentage of BSA involved to determine the number of tubes to dispense to each patient. Patients and caregivers were to apply the assigned treatment to all areas identified at baseline and new lesions that developed during the trial once daily for 4 weeks, even if areas cleared. Palms and soles could be treated with the assigned treatment but were not counted toward efficacy assessments. The scalp was neither treated nor assessed. Nonmedicated emollients or moisturizers could be applied once daily but only to untreated areas of the patient’s skin.

Patients were randomized via an interactive online system to roflumilast cream, 0.15%, or vehicle cream in a 2:1 ratio according to a computer-generated randomization list stratified by vIGA-AD score (2 vs 3) and trial site. The sponsor, patients and caregivers, and assessors of end points were unaware of the patients’ group assignments.

Primary and Secondary End Points

The primary efficacy end point for both trials was vIGA-AD success (defined as vIGA-AD score of 0 [clear] or 1 [almost clear] plus at least 2-grade improvement from baseline) at week 4. Secondary end points were vIGA-AD success at week 4 in patients with vIGA-AD score of 3 at randomization; Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale (WI-NRS) success (defined as ≥4-point reduction on the 11-point WI-NRS scale, which ranges from 0 [no itch] to 10 [worst itch imaginable],30 in patients with baseline WI-NRS score ≥ 4) at weeks 1, 2, and 4; greater than or equal to 75% reduction in EASI (EASI-75) at week 4 (weeks 1 and 2 were exploratory end points); vIGA-AD score 0 or 1 at weeks 1, 2, and 4; and vIGA-AD success at weeks 1 and 2.

Per categories required by regulatory agencies, investigators collected demographic data for each patient, including sex, age, race, and ethnicity. Participants self-reported race and ethnicity from a list of fixed categories, which included options to select race as “not reported” or “other” with an option to specify race.

Safety was monitored through adverse events (AEs), investigator-rated and patient-rated local tolerability assessments, vital signs, physical examination, clinical laboratory parameters, assessments of depression and suicidal ideation, and other clinical assessments (eMethods in Supplement 2).

Statistical Analysis

A sample size of 650 participants was planned for each trial. This provided approximately 95% power to detect an overall 15% difference between the treatment groups on vIGA-AD success at week 4 at α < .05 using a 2-sided stratified (vIGA-AD at randomization and trial site) Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test. The 15% treatment difference was based on the phase 2 trial results.24 If the primary end point was statistically significant, the hierarchy of secondary end points was inferentially tested (eFigure 1 in Supplement 2).

Primary and secondary efficacy analyses used the intention-to-treat (ITT) population (defined as all randomized patients) with 2 exceptions: (1) vIGA-AD success at week 4 used the subset of patients from the ITT population with vIGA-AD score of 3 at randomization, and (2) WI-NRS success at all time points used the subset of the ITT population 12 years or older with baseline WI-NRS score of at least 4. The safety population comprised all patients who received at least 1 confirmed application of the investigational product.

The primary end point of vIGA-AD success at week 4 was analyzed using a Cochran-Mantel-Haenszel test, stratified by trial site and baseline vIGA-AD score; the multiple imputation method was used to handle missing data. Patients who discontinued treatment because of AEs or lack of efficacy were considered nonresponders after discontinuation. SAS statistical software, version 9.4 or higher (SAS Institute Inc), was used to perform all statistical analyses. Statistical assessments are detailed further in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

Results

Study Participants

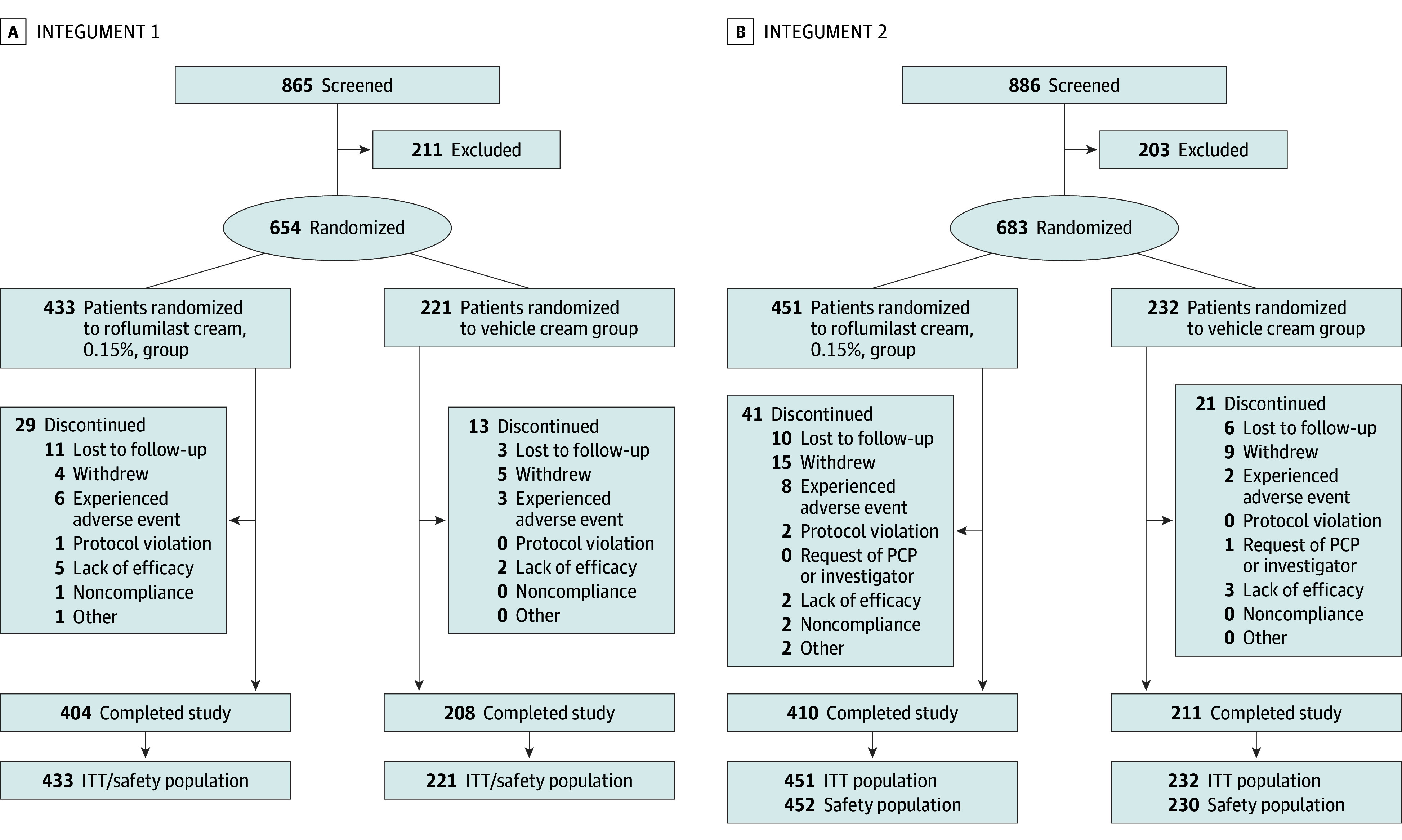

In INTEGUMENT-1, 865 patients were screened, and 654 patients were randomized to receive treatment (roflumilast, n = 433; vehicle, n = 221). Of these, 42 patients (6.4%) discontinued, and 612 patients (93.6%) completed the trial (Figure 1). Of 886 patients screened in INTEGUMENT-2, 683 patients were randomized to receive treatment (roflumilast: n = 451; vehicle: n = 232). Of these, 62 patients (9.1%) discontinued, and 621 patients (90.9%) completed the trial (Figure 1).

Figure 1. INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2 Flow Diagrams.

INTEGUMENT indicates Interventional Trial Evaluating Roflumilast Cream for the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis. ITT, intention-to-treat; PCP, primary care physician.

Patient demographic and baseline characteristics were similar in roflumilast and vehicle groups in both trials (eTable 2 in Supplement 2). The mean (SD) age was 27.7 (19.2) years, and 761 participants (56.9%) were female. A total of 1014 patients (75.8%) had vIGA-AD of 3 at baseline. The mean (SD) BSA involved was 13.6% (SD = 11.6%); overall BSA ranged from 3.0% to 88.0%. Of all patients in both trials, 567 patients (42.4%) and 277 patients (20.7%) had facial and eyelid involvement, respectively. Across both groups and trials, 813 (60.8%), 242 (18.1%), and 98 (7.3%) reported previous inadequate response, intolerance, or contraindication to topical corticosteroids, TCIs, and crisaborole, respectively.

Efficacy Outcomes

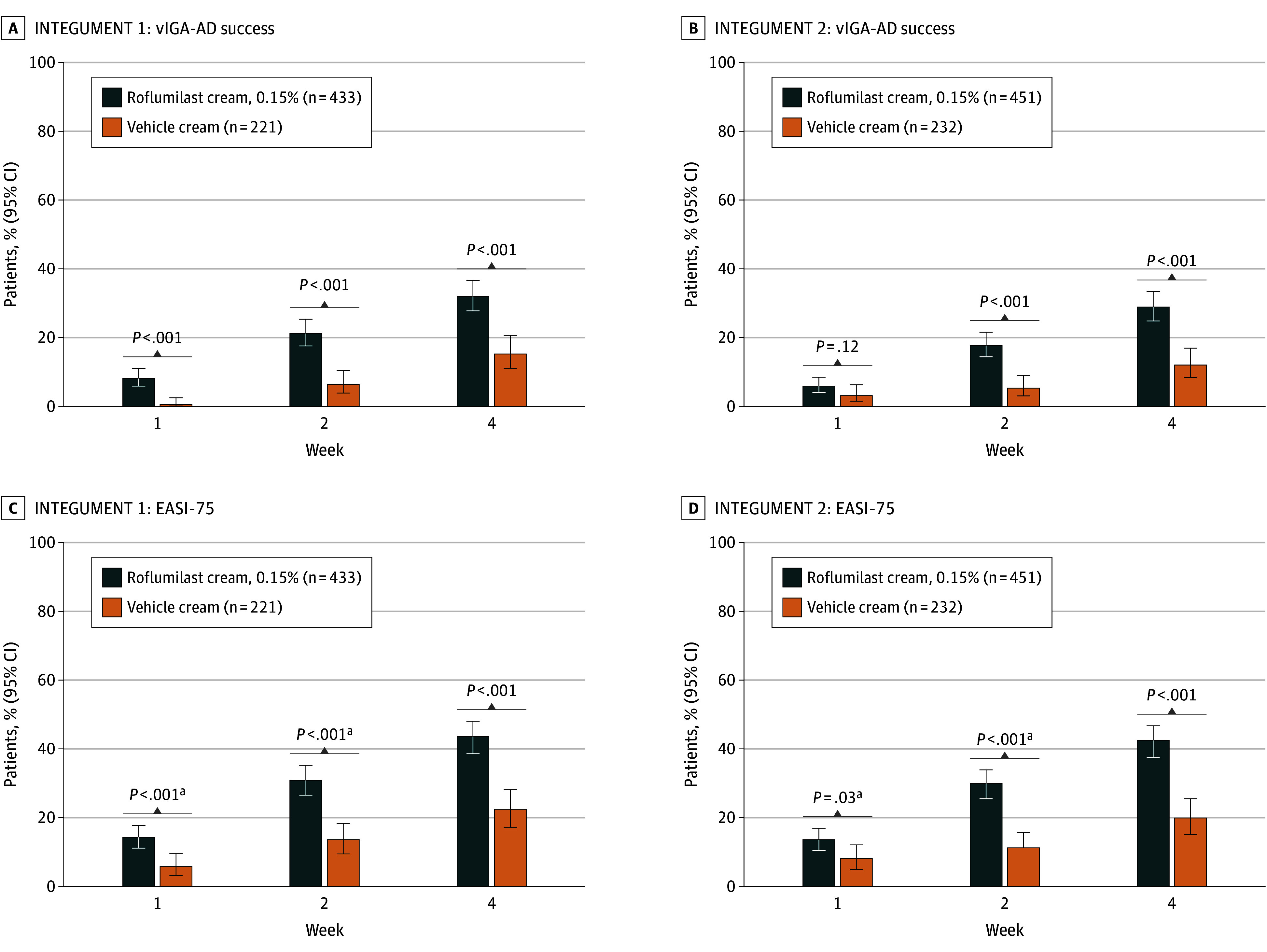

In INTEGUMENT-1, 32.0% of patients treated with roflumilast and 15.2% of patients treated with vehicle achieved the primary end point of vIGA-AD success at week 4 (percent difference, 17.4%; P < .001; Figure 2). In INTEGUMENT-2, 28.9% of patients treated with roflumilast and 12.0% of patients treated with vehicle achieved the primary end point of vIGA-AD success at week 4 (percent difference, 16.5%; P < .001; Figure 2). At week 4, vIGA-AD success was consistently higher for patients treated with roflumilast than for patients treated with vehicle across all age groups and in those with baseline vIGA-AD of 3 (eTable 3 in Supplement 2).

Figure 2. Percentage of Patients Achieving vIGA-AD Success and at Least 75% Improvement in EASI Score.

Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD) was evaluated on a 5-point scale: 0 (clear), 1 (almost clear), 2 (mild), 3 (moderate), and 4 (severe). vIGA-AD success was defined as a score of 0 or 1 plus at least a 2-grade improvement from baseline. EASI-75 indicates at least a 75% reduction in Eczema Area and Severity Index score from baseline.

aP values are nominal.

Statistically significant differences were also observed between the roflumilast and vehicle groups for vIGA-AD success at weeks 1 and 2 in INTEGUMENT-1 (week 1: 8.1% of patients vs 0.5% of patients; P < .001; week 2: 21.2% of patients vs 6.4% of patients; P < .001; Figure 2) and week 2 in INTEGUMENT-2 (17.7% of patients vs 5.3% of patients; P < .001; Figure 2). In both trials, more patients treated with roflumilast cream than patients treated with vehicle cream achieved EASI-75 (Figure 2) and vIGA-AD 0/1 (eFigure 2 in Supplement 2) at weeks 1, 2, and 4. Differences in the least squares mean percentage change from baseline in EASI also favored roflumilast cream (eFigure 3 in Supplement 2).

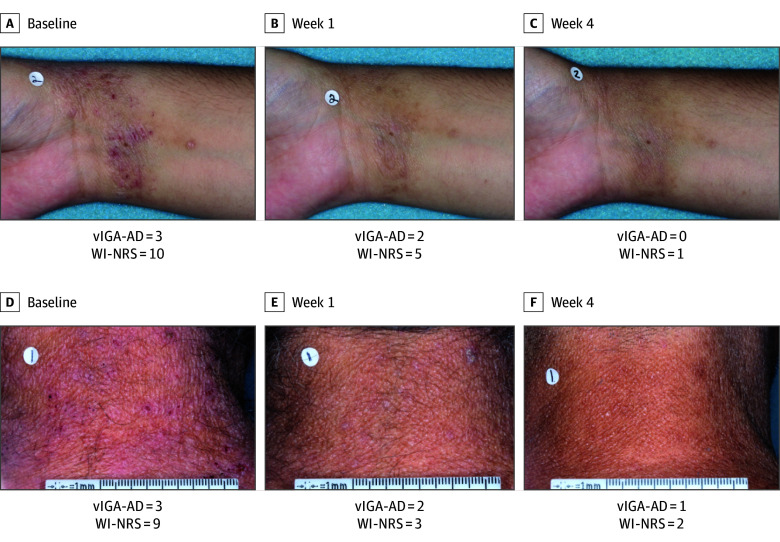

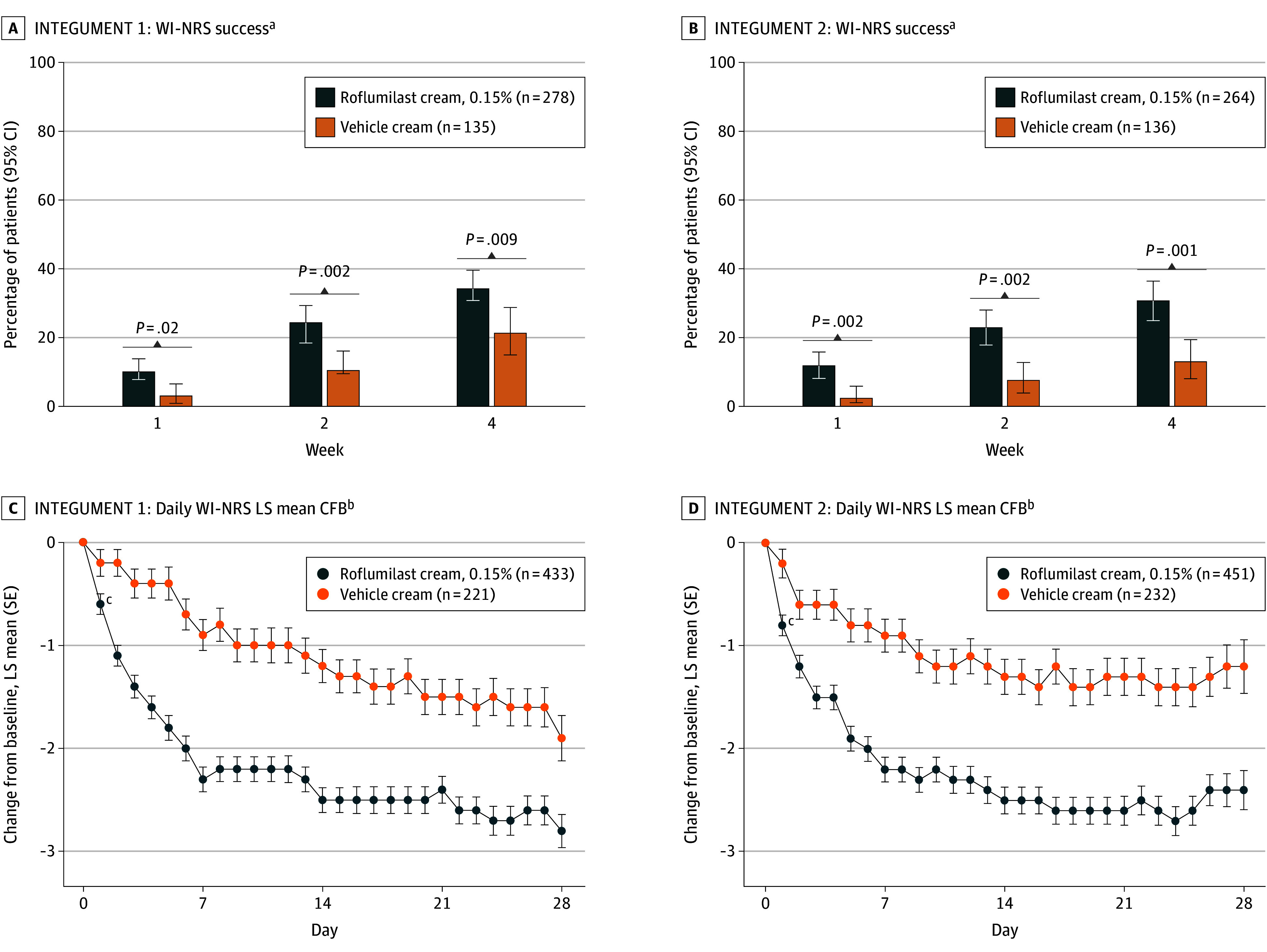

In patients with a WI-NRS score of at least 4 at baseline, statistically significantly more patients treated with roflumilast cream achieved at least a 4-point reduction on WI-NRS than patients treated with vehicle cream at weeks 1, 2, and 4 (Figure 3). In the ITT population, patients experienced statistically significant greater changes from baseline in daily WI-NRS score with roflumilast cream treatment vs vehicle cream treatment for all time points, including as early as 24 hours following the first application (nominal P = .004 [INTEGUMENT-1] and P < .001 [INTEGUMENT-2]) (Figure 3). Time-sequenced photographs of patients with improvement in AD after roflumilast treatment are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 3. Percentage of Patients With Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale (WI-NRS) Success and Daily Changes.

WI-NRS was evaluated on an 11-point scale ranging from 0 (no itch) to 10 (worst itch imaginable). WI-NRS success was defined as at least a 4-point reduction in WI-NRS from baseline in patients 12 years or older. CFB indicates change from baseline; LS, least squares.

aEvaluated in patients 12 years or older with baseline WI-NRS score of at least 4.

bEvaluated in all patients, not just those with baseline WI-NRS scores of at least 4.

cNominal P = .004 (INTEGUMENT-1) and P < .001 (INTEGUMENT-2) at 24 hours following the first application, and P < .05 at all subsequent time points, for difference vs vehicle.

Figure 4. Clinical Images of Atopic Dermatitis in Patients Treated With Roflumilast Cream, 0.15%, Over 4 Weeks.

vIGA-AD indicates Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis; WI-NRS, Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale. vIGA-AD and WI-NRS are global measures.

Safety Outcomes

Roflumilast was well tolerated with a low incidence of treatment-emergent AEs (TEAEs) and treatment-related TEAEs in the roflumilast and vehicle groups in both trials (Table). A treatment-related TEAE was defined as any TEAE that was assessed by the investigator as likely, probably, or possibly related to the study treatment. Most TEAEs were mild to moderate in severity. Four patients (0.9%) treated with roflumilast in each trial experienced serious TEAEs, with 1 serious AE deemed possibly related to treatment and 1 probably related to treatment (Table). Overall, TEAEs leading to discontinuation ranged from 2 patients (0.9%) to 8 patients (1.8%) across both groups and trials (Table).

Table. Adverse Event Profiles for Roflumilast and Vehicle Groups in INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2a.

| Event | No. of patients (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| INTEGUMENT-1 | INTEGUMENT-2 | |||

| Roflumilast cream, 0.15% (n = 433) | Vehicle cream (n = 221) | Roflumilast cream, 0.15% (n = 452) | Vehicle cream (n = 230) | |

| Patients with any TEAE | 92 (21.2) | 35 (15.8) | 102 (22.6) | 30 (13.0) |

| Patients with any treatment-related TEAEb | 27 (6.2) | 4 (1.8) | 26 (5.8) | 8 (3.5) |

| Patients with any serious TEAEc | 4 (0.9) | 0 | 4 (0.9) | 0 |

| Patients with any TEAE leading to discontinuation | 6 (1.4) | 3 (1.4) | 8 (1.8) | 2 (0.9) |

| Most common TEAEs by preferred term, ≥1% in any group | ||||

| Headache | 10 (2.3) | 3 (1.4) | 16 (3.5) | 1 (0.4) |

| Nausea | 8 (1.8) | 2 (0.9) | 9 (2.0) | 0 |

| Application-site pain | 9 (2.1) | 1 (0.5) | 4 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) |

| Nasopharyngitis | 8 (1.8) | 2 (0.9) | 0 | 1 (0.4) |

| COVID-19 | 4 (0.9) | 5 (2.3) | 4 (0.9) | 3 (1.3) |

| Diarrhea | 6 (1.4) | 0 | 7 (1.5) | 2 (0.9) |

| Vomiting | 5 (1.2) | 0 | 8 (1.8) | 2 (0.9) |

| Upper respiratory tract infection | 0 | 1 (0.5) | 5 (1.1) | 1 (0.4) |

Abbreviations: INTEGUMENT, Interventional Trial Evaluating Roflumilast Cream for the Treatment of Atopic Dermatitis; TEAE, treatment-emergent adverse event.

Adverse events are for the safety population, defined as all patients who were enrolled and received at least 1 confirmed dose of trial medication.

Investigators reviewed each event and assessed its relationship to the investigational product. A treatment-related TEAE is defined as any TEAE that is assessed by the investigator as likely, probably, or possibly related to study treatment.

In INTEGUMENT-1, serious adverse events were depression (unlikely related to the investigational product), diverticulitis (unrelated to the investigational product), pulmonary embolism (unrelated to the investigational product), and suicidal ideation (unrelated to the investigational product). In INTEGUMENT-2, serious adverse events were cutaneous nerve entrapment (unrelated to the investigational product), general physical health deterioration (possibly related to the investigational product), progression of atopic dermatitis that was disproportionately greater than the natural history of atopic dermatitis (probably related to the investigational product), and staphylococcal scalded skin syndrome (unlikely related to the investigational product).

At each time point, more than 95% of patients treated with roflumilast had a score of no signs of irritation (0) on investigator-rated local tolerability assessments, and more than 90% reported no (0) or mild (1) sensation on patient-rated local tolerability assessments (including on application day 1; eFigure 4 in Supplement 2). Across both trials, of the 98 patients with previous inadequate response, intolerance, or contraindication to crisaborole, 47 patients (34 patients treated with roflumilast; 13 patients treated with vehicle) had previously stopped crisaborole because of stinging, burning, and/or poor tolerability. None of these patients developed application-site AEs during roflumilast or vehicle treatment in these trials. Additional safety details are in the eMethods in Supplement 2.

Discussion

Once-daily, nonsteroidal roflumilast cream, 0.15%, improved mild to moderate AD in 2 phase 3 randomized clinical trials, in which the results were highly consistent. Patients treated with roflumilast cream, 0.15%, achieved the primary end point of vIGA-AD success at week 4 significantly more than patients treated with vehicle cream, with similar results observed for children, adolescents, and adults. Significant improvements were observed in vIGA-AD success by week 1 in INTEGUMENT-1 and week 2 in INTEGUMENT-2. Differences in EASI-75 at weeks 1, 2, and 4 also favored roflumilast. The achievement of primary and secondary end points at 4 weeks, with statistically significant differences observed at weeks 1 and 2, is notable given that many trials of topical treatments for AD have primary end points at 12 weeks.31,32 While the improvements at 4 weeks are clinically meaningful, longer-duration clinical studies are required to evaluate the benefit of chronic administration.

Improvement in itch is crucial as it is the most common and burdensome symptom of AD and negatively impacts the patient’s quality of life.4 Statistically significantly more patients treated with roflumilast cream than patients treated with vehicle cream with baseline WI-NRS of 4 or more achieved at least a 4-point reduction at weeks 1, 2, and 4 in both trials. Notably, itch improved with roflumilast treatment as compared with vehicle treatment at 24 hours after the first application. Although the mechanism by which PDE4 inhibition reduces itch is unknown, it may be related to reduced proinflammatory mediators by lesional immune infiltrates, specifically type 2 cytokines that promote itch.33 Furthermore, PDE4 inhibition has an antipruritic effect in mouse models of dermatoses that is distinct from the anti-inflammatory effect, possibly mediated by direct suppression of C-fibers responsible for itch perception.33

In patients with mild to moderate AD, roflumilast cream, 0.15%, demonstrated favorable safety and tolerability, including when applied on sensitive areas such as the face and eyelids. Patients treated with roflumilast had low rates of treatment-related TEAEs, including gastrointestinal AEs typically observed with systemic PDE4 inhibitors, such as diarrhea and nausea. Additionally, the safety and tolerability profiles of patients with AD treated with roflumilast cream, 0.15%, was generally consistent with those observed in patients with psoriasis treated with roflumilast cream, 0.3%.21 In contrast to other topical nonsteroidal AD therapies that often induce stinging, burning, itching, and irritation,34 application-site pain was reported in only 0.9% and 2.1% of patients treated with roflumilast cream in INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2, respectively. Furthermore, of the patients who had discontinued crisaborole prior to enrollment in the current trials because of stinging or burning, none reported application-site pain during the INTEGUMENT-1 or INTEGUMENT-2 trials. Although the overall rate of application-site pain in phase 3 trials of crisaborole, 2% ointment, was 4.4%,10 subsequent trials and medical record studies suggest a higher incidence. For example, in a 4-week phase 3b/4 trial in patients with mild to moderate AD, 13.8% of patients taking crisaborole experienced application-site pain compared with 1.7% of patients treated with vehicle.19 Similarly, in a retrospective medical record study of crisaborole to treat AD, 31.7% of patients experienced application-site pain (typically within a few minutes of application) including 50% of patients who applied crisaborole on their face.18 The INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2 trials prospectively assessed local tolerability using both investigator-rated and patient-rated local tolerability assessments at multiple time points (in clinic before and after application, respectively) as well as via reports of application-site AEs, increasing reliability that the low rates of application-site pain observed in these trials are accurate.

Skin barrier disruption in AD leads to penetration of irritants and allergens, skin microbiome disruption, and water loss.35,36 Topical corticosteroids, often used to treat AD, can cause skin atrophy16,17 and thus further disrupt the skin barrier. Roflumilast, which uses a water-based vehicle cream without sensitizers or penetration enhancers, was designed to protect the skin barrier. The vehicle cream contains a mild emulsifier that does not extract lipids from the skin and is commonly used in cosmetic products but not previously used in prescription topical formulations prior to roflumilast cream and foam.37 As assessed by patients and investigators, this vehicle cream has demonstrated similar efficacy, tolerability, and aesthetic properties to a commonly recommended moisturizer.35 Thus, the novel vehicle formulation likely contributed to the favorable local tolerability of both roflumilast and its vehicle in these trials.

Adherence to topical therapies in patients with chronic inflammatory diseases such as AD is generally poor.12 Roflumilast addresses this unmet medical need by reducing the barriers to adherence. Because fear of AEs is a common reason for nonadherence,13 the low rates of AEs and favorable local tolerability scores observed with roflumilast may reduce this fear and thus improve adherence. Furthermore, all currently approved nonsteroidal topical therapies for AD (tacrolimus,38 pimecrolimus,14 crisaborole,39 ruxolitinib20) are indicated for twice-daily use; roflumilast’s simpler, once-daily treatment regimen also may improve adherence.40 Lastly, given patients’ preference for less greasy formulations,11 patients may be more likely to apply roflumilast cream as prescribed than ointments such as tacrolimus and crisaborole.11

The disparities in diagnostic accuracy and therapeutic management among patients with AD identified as having skin of color underscore the importance of studying diverse patient populations.41 The diverse racial and ethnic profiles of the patients in the INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2 trials serve to reduce these disparities.

Limitations

Limitations of the trials include their short duration, minimum age limit of 6 years, and lack of an active comparator. An ongoing open-label extension trial (NCT04804605) is studying long-term treatment with roflumilast cream in patients 2 years or older, including proactive use and maintenance therapy of previously affected areas that have since cleared. Similarly, a phase 3 trial (NCT04845620) in patients aged 2 to 5 years with AD evaluated the safety and efficacy of roflumilast in these younger patients.

Conclusions

The INTEGUMENT-1 and INTEGUMENT-2 phase 3 randomized clinical trials of patients with AD treated with roflumilast cream, 0.15%, demonstrated improvement across multiple efficacy end points, including reducing pruritus within 24 hours after application, with favorable safety and tolerability. This once-daily nonsteroidal cream addresses several unmet needs in the treatment of AD and thus has the potential to substantially improve treatment. Additional research, including subgroup analyses, will provide more data regarding the efficacy and safety of roflumilast cream, 0.15%, in patients with AD.

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

Investigators

eMethods

eFigure 1. Testing Hierarchy

eFigure 2. Percentage of Patients Achieving vIGA-AD 0/1

eFigure 3. LS Mean % Change from Baseline in EASI

eFigure 4. Investigator- (A, B) and Patient-Rated (C, D) Local Tolerability

eTable 1. vIGA-AD Scale

eTable 2. Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

eTable 3. vIGA-AD Success at Week 4

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement

References

- 1.Asher MI, Montefort S, Björkstén B, et al. ; ISAAC Phase Three Study Group . Worldwide time trends in the prevalence of symptoms of asthma, allergic rhinoconjunctivitis, and eczema in childhood: ISAAC phases one and three repeat multicountry cross-sectional surveys. Lancet. 2006;368(9537):733-743. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)69283-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barbarot S, Auziere S, Gadkari A, et al. Epidemiology of atopic dermatitis in adults: results from an international survey. Allergy. 2018;73(6):1284-1293. doi: 10.1111/all.13401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Silverberg JI, Barbarot S, Gadkari A, et al. Atopic dermatitis in the pediatric population: a cross-sectional, international epidemiologic study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2021;126(4):417-428.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2020.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Silverberg JI, Gelfand JM, Margolis DJ, et al. Patient burden and quality of life in atopic dermatitis in US adults: a population-based cross-sectional study. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;121(3):340-347. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vakharia PP, Chopra R, Sacotte R, et al. Burden of skin pain in atopic dermatitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2017;119(6):548-552.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2017.09.076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bawany F, Northcott CA, Beck LA, Pigeon WR. Sleep disturbances and atopic dermatitis: relationships, methods for assessment, and therapies. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2021;9(4):1488-1500. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.12.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gittler JK, Shemer A, Suárez-Fariñas M, et al. Progressive activation of T(H)2/T(H)22 cytokines and selective epidermal proteins characterizes acute and chronic atopic dermatitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;130(6):1344-1354. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2012.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grewe SR, Chan SC, Hanifin JM. Elevated leukocyte cyclic AMP-phosphodiesterase in atopic disease: a possible mechanism for cyclic AMP-agonist hyporesponsiveness. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1982;70(6):452-457. doi: 10.1016/0091-6749(82)90008-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanifin JM, Chan SC, Cheng JB, et al. Type 4 phosphodiesterase inhibitors have clinical and in vitro anti-inflammatory effects in atopic dermatitis. J Invest Dermatol. 1996;107(1):51-56. doi: 10.1111/1523-1747.ep12297888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Paller AS, Tom WL, Lebwohl MG, et al. Efficacy and safety of crisaborole ointment, a novel, nonsteroidal phosphodiesterase 4 (PDE4) inhibitor for the topical treatment of atopic dermatitis (AD) in children and adults. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75(3):494-503.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2016.05.046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eastman WJ, Malahias S, Delconte J, DiBenedetti D. Assessing attributes of topical vehicles for the treatment of acne, atopic dermatitis, and plaque psoriasis. Cutis. 2014;94(1):46-53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hix E, Gustafson CJ, O’Neill JL, et al. Adherence to a five day treatment course of topical fluocinonide 0.1% cream in atopic dermatitis. Dermatol Online J. 2013;19(10):20029. doi: 10.5070/D31910020029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Capozza K, Schwartz A. Does it work and is it safe—parents’ perspectives on adherence to medication for atopic dermatitis. Pediatr Dermatol. 2020;37(1):58-61. doi: 10.1111/pde.13991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.ELIDEL (pimecrolimus) cream prescribing information. Bausch Health US, LLC. September 2020. Accessed August 26, 2024. https://pi.bauschhealth.com/globalassets/BHC/PI/Elidel-PI.pdf

- 15.Ashcroft DM, Dimmock P, Garside R, Stein K, Williams HC. Efficacy and tolerability of topical pimecrolimus and tacrolimus in the treatment of atopic dermatitis: meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2005;330(7490):516. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38376.439653.D3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Luger TA, Lahfa M, Fölster-Holst R, et al. Long-term safety and tolerability of pimecrolimus cream 1% and topical corticosteroids in adults with moderate to severe atopic dermatitis. J Dermatolog Treat. 2004;15(3):169-178. doi: 10.1080/09546630410033781 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ramachandran V, Cline A, Feldman SR, Strowd LC. Evaluating crisaborole as a treatment option for atopic dermatitis. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2019;20(9):1057-1063. doi: 10.1080/14656566.2019.1604688 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pao-Ling Lin C, Gordon S, Her MJ, Rosmarin D. A retrospective study: application site pain with the use of crisaborole, a topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;80(5):1451-1453. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2018.10.054 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.EUCTR208-00143-31—a phase 3b/4, multicenter, randomized, assessor blinded, vehicle and active (topical corticosteroid and calcineurin inhibitor) controlled, parallel group study of the efficacy, safety, and local tolerability of crisaborole ointment, 2% in pediatric and adult subjects (ages 2 years and older) with mild to moderate atopic dermatitis. 2021. Accessed July 28, 2023. https://www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/trial/2018-001043-31/results

- 20.Opzelura (ruxolitinib) cream prescribing information. Incyte Corporation. September 2023. Accessed August 16, 2024. https://www.opzelura.com/opzelura-prescribing-information

- 21.ZORYVE (roflumilast) cream prescribing information. Arcutis Biotherapeutics, Inc. July 2024. Accessed August 16, 2024. https://www.arcutis.com/wp-content/uploads/USPI-roflumilast-cream.pdf

- 22.Kircik LH, Alonso-Llamazares J, Bhatia N, et al. Once-daily roflumilast foam 0.3% for scalp and body psoriasis: a randomized, double-blind, vehicle-controlled phase IIb study. Br J Dermatol. 2023;189(4):392-399. doi: 10.1093/bjd/ljad182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zirwas MJ, Draelos ZD, DuBois J, et al. Efficacy of roflumilast foam, 0.3%, in patients with seborrheic dermatitis: a double-blind, vehicle-controlled phase 2a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Dermatol. 2023;159(6):613-620. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2023.0846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gooderham M, Kircik L, Zirwas M, et al. The safety and efficacy of roflumilast cream 0.15% and 0.05% in patients with atopic dermatitis: randomized, double-blind, phase 2 proof of concept study. J Drugs Dermatol. 2023;22(2):139-147. doi: 10.36849/JDD.7295 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang J, Bunick CG. Clinically relevant differences in the chemical and structural mechanism of action of dermatological phosphodiesterase-4-inhibitors. Presented at: International Societies for Investigative Dermatology; May 10-13, 2023; Tokyo, Japan. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dong C, Virtucio C, Zemska O, et al. Treatment of skin inflammation with benzoxaborole PDE inhibitors: selectivity, cellular activity, and effect on cytokines associated with skin inflammation and skin architecture changes. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2016;358(3):413-422. doi: 10.1124/jpet.116.232819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Medical Association . World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA. 2013;310(20):2191-2194. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.281053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hanifin JM, Thurston M, Omoto M, Cherill R, Tofte SJ, Graeber M; EASI Evaluator Group . The Eczema Area and Severity Index (EASI): assessment of reliability in atopic dermatitis. Exp Dermatol. 2001;10(1):11-18. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-0625.2001.100102.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Simpson E, Bissonnette R, Eichenfield LF, et al. The Validated Investigator Global Assessment for Atopic Dermatitis (vIGA-AD): the development and reliability testing of a novel clinical outcome measurement instrument for the severity of atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020;83(3):839-846. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.04.104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Naegeli AN, Flood E, Tucker J, Devlen J, Edson-Heredia E. The Worst Itch Numeric Rating Scale for patients with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis or psoriatic arthritis. Int J Dermatol. 2015;54(6):715-722. doi: 10.1111/ijd.12645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Paller A, Eichenfield LF, Leung DY, Stewart D, Appell M. A 12-week study of tacrolimus ointment for the treatment of atopic dermatitis in pediatric patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;44(1)(suppl):S47-S57. doi: 10.1067/mjd.2001.109813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Paller AS, Stein Gold L, Soung J, Tallman AM, Rubenstein DS, Gooderham M. Efficacy and patient-reported outcomes from a phase 2b, randomized clinical trial of tapinarof cream for the treatment of adolescents and adults with atopic dermatitis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84(3):632-638. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2020.05.135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ishii N, Shirato M, Wakita H, et al. Antipruritic effect of the topical phosphodiesterase 4 inhibitor E6005 ameliorates skin lesions in a mouse atopic dermatitis model. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2013;346(1):105-112. doi: 10.1124/jpet.113.205542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Silverberg JI, Nelson DB, Yosipovitch G. Addressing treatment challenges in atopic dermatitis with novel topical therapies. J Dermatolog Treat. 2016;27(6):568-576. doi: 10.1080/09546634.2016.1174765 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Draelos Z, Higham RC, Osborne DW, Seal MS, Burnett P, Berk DR. Assessment of the vehicle for roflumilast cream compared to a commercially marketed, ceramide-containing moisturizing cream in patients with mild eczema. Abstract and poster 646 presented at Revolutionizing Atopic Dermatology Virtual Meeting, December 11-13, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Kim BE, Leung DYM. Significance of skin barrier dysfunction in atopic dermatitis. Allergy Asthma Immunol Res. 2018;10(3):207-215. doi: 10.4168/aair.2018.10.3.207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Berk D, Osborne DW. Krafft temperature of surfactants in vehicles for roflumilast and pimecrolimus cream and effects on skin tolerability. J Invest Dermatol. 2022;142(8):S101. doi: 10.1016/j.jid.2022.05.602 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 38.PROTOPIC (tacroliumus) ointment prescribing information. LEO Pharma Inc. February 2019. Accessed August 26, 2024. https://mc-df05ef79-e68e-4c65-8ea2-953494-cdn-endpoint.azureedge.net/-/media/corporatecommunications/us/therapeutic-expertise/our-product/protopicpi.pdf

- 39.EUCRISA (crisaborole) ointment prescribing information. Pfizer, Inc. April 2023. Accessed August 16, 2024. https://www.pfizermedicalinformation.com/patient/eucrisa/medguide

- 40.Patel NU, D’Ambra V, Feldman SR. Increasing adherence with topical agents for atopic dermatitis. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2017;18(3):323-332. doi: 10.1007/s40257-017-0261-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Quan VL, Erickson T, Daftary K, Chovatiya R. Atopic dermatitis across shades of skin. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2023;24(5):731-751. doi: 10.1007/s40257-023-00797-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Trial Protocol and Statistical Analysis Plan

Investigators

eMethods

eFigure 1. Testing Hierarchy

eFigure 2. Percentage of Patients Achieving vIGA-AD 0/1

eFigure 3. LS Mean % Change from Baseline in EASI

eFigure 4. Investigator- (A, B) and Patient-Rated (C, D) Local Tolerability

eTable 1. vIGA-AD Scale

eTable 2. Patient Demographics and Baseline Characteristics

eTable 3. vIGA-AD Success at Week 4

eReferences

Data Sharing Statement