Abstract

Objective

This study was conducted to summarize existing studies on the association between solitary experiences and problematic social media use (PSMU) among young adults.

Method

A systematic review was performed according to the PRISMA guidelines, implemented in Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed and PsycINFO. We selected studies if they presented original data, assessed solitary experiences and PSMU in young adults (i.e., 18-30 age range), were published in peer reviewed journals between 2004 and 2023, and were written in English.

Results

After duplicate removal, 1,841 eligible studies were found. From these, 12 articles were selected, encompassing 4,009 participants. Most studies showed a positive association between general loneliness and PSMU. Some of these suggested that this relationship varies based on the facets of loneliness, other potential variables, and the type of social media. No mediating factors were found. Few studies assessed solitary experiences other than general loneliness, highlighting the need for a multidimensional perspective on solitary experience in investigating PSMU.

Conclusions

Implications and future research orientations are discussed.

Keywords: aloneness, loneliness, problematic social media use, social media, solitary experience, solitude

1. Introduction

Social media (SM) are Internet-based interactive applications, defined as a tool through which user-generated content can be created and shared (Aichner et al., 2021), accessible through digital devices, such as smartphones, tablets and computers. In recent years, SM use has increased significantly, with a recent estimation showing that there are 59.4% global SM users (Petrosyan, 2023). This trend is particularly marked among young adults (i.e., people between 18 and 30 years old; Coyne et al., 2013; Wilkinson & Dunlop, 2020), with over 90% of them actively using SM (Villanti et al., 2017). Young adulthood represents a transitional period between the adolescence and adulthood, characterized by passage from the family context to the broader social context (Francesetti et al., 2020), marked by significant changes, such as university, work and the establishment of a new autonomy (Vaterlaus et al., 2015). Most young adults use SM as an integral part of the daily life, which can improve social capital, friendship formations, a sense of community and reduce feelings of loneliness (Ryan et al., 2017). Despite these advantages, a minority of users can develop SM overuse, characterized by addiction-like symptoms (Shannon et al., 2022; Shensa et al., 2017). In spite of the amount of research in this area and the diffusion of this phenomenon – a prevalence of 14% in individualistic cultures and 31% in collectivist cultures was estimated (Cheng et al., 2021) –, there is no agreement on the definition of a dysfunctional use of SM. Indeed, the main psychiatric classifications (i.e., Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders Text Revision – DSM-5-TR and the International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision – ICD-11; American Psychiatric Association, 2022; World Health Organization, 2019) do not include diagnoses related to dysfunctional SM behaviors. For this reason, we will use the term ‘Problematic Social Media Use’ (PSMU) to refer to an excessive SM use associated with negative consequences (e.g., interference with work, interpersonal conflicts) and addictive-like symptoms, such as withdrawal and relapse (Fournier et al., 2023). Among young adults, PSMU has been linked to increased psychopathological symptoms and maladjustment, such as depression (Vaterlaus et al., 2015) and anxiety (Barbar et al., 2021; Malaeb et al., 2021; Shannon et al., 2022; Vannucci et al., 2017), stress (Shannon et al., 2022), as well as low self-esteem (Samra et al., 2022), and a poor sleep quality (Moretta et al., 2023). Furthermore, PSMU has been found to be related to different solitary experiences, such as low social connectedness (Savci & Aysan, 2017), high levels of loneliness (Griffiths et al., 2014; O’Day & Heimberg, 2021) and high perceived social isolation (Galanaki, 2004; Primack et al., 2017). However, previous findings concerning the relationships between PSMU and different forms of solitary experiences among young adults have not been summarized in a comprehensive overview.

1.1. Solitary media use experiences and problematic social

Solitary experience can be conceptualized as a not unitary phenomenon which encompasses both objective and subjective forms (Galanaki, 2004; Goossens et al., 2009). Objective forms concern an absence of social interactions (e.g., aloneness, social withdrawal and social isolation), whereas subjective forms refer to the individuals’ feelings about their solitary condition (e.g., loneliness and solitude). An objective form of solitary experience is the aloneness, which refers to the state characterized by the lack of communication with others (Galanaki, 2004). Aloneness is not necessarily associated with unpleasant feelings (Majorano et al., 2015) and can occur through social withdrawal (i.e., the voluntary behavior of withdrawing oneself from social situations). In fact, various reasons might lead to social withdrawal (Rubin & Coplan, 2004; Wang et al., 2013), such as social anxiety (Gazelle & Ladd, 2003), a disinterest towards social interactions (Coplan et al., 2004), or the engagement in enjoyable activities which do not involve other people (Ost Mor et al., 2021). Additionally, the term “social isolation” refers to the objective lack of social network and support (Nicholson, 2009).

Moreover, an individual, either in the objective state of aloneness or in the presence of other people, may experience different feelings of being alone, i.e., subjective forms of solitary experience. Among the subjective solitary experiences is loneliness, which can be described through a unidimensional or multidimensional perspective. From a unidimensional or general approach, loneliness is a subjective condition (Asher & Paquette, 2003) characterized by a state of unpleasure and discomfort, which occurs when an individual’s social relationships are significantly lacking in terms of quantity or quality (Perlman & Peplau, 1998). From a multidimensional approach, Weiss (1973) has distinguished between an emotional loneliness, which denotes a lack of deep and intimate bond with another individual, and a social loneliness, which denotes the lack of a social network of which the individual belongs. Both emotional and social loneliness are marked by a negative emotional experience. Furthermore, an individual can feel lonely in relation to specific interpersonal contexts (Cramer & Barry, 1999; Maes et al., 2022). Specifically, Schmidt and Sermat (1983) have distinguished among four domains of loneliness: romantic/sexual loneliness, occurring within a romantic or sexual context; friendship loneliness, involving peer friendship relationships; family loneliness, occurring within the family setting; and loneliness in a larger group or the community, encompassing a broader social and community dimension.

In addition to the emotional negative forms of subjective solitary experience, various scholars have focused on solitude, often called “positive solitude”. With this term, Ost Mor et al. (2021) refers to the choice to use one’s time for a significant and pleasant activity or experience, made by and for oneself. Unlike general loneliness, which is associated with psychopathology (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010) and problematic use of Internet platforms (Moretta & Buodo, 2020), solitude is linked with adaptive and positive developmental outcomes (Long et al., 2003; Nguyen et al., 2018; Thomas, 2023; Weinstein et al., 2021; White et al., 2022). For example, suppose a person who, after a day of work among others, chooses to spend some time alone, taking a walk outdoors. They may experience several benefits at that moment, like self-connection and self-exploration, as well as stress reduction and mood regulation (Thomas, 2023).

Therefore, sometimes being alone is neither sought nor desired and is experienced with negative feelings (Laursen & Hartl, 2013), while at other times individuals may be driven by internal motivations to be alone (Baumeister & Leary, 1995; Corsano et al., 2011). The motivations for solitary behaviors can be understood in the context of Self Determination Theory (Deci & Ryan, 2000), in which the role of the volitional aspect of autonomous behavior is emphasized. According to this theory, the positive outcomes related to being alone are not directly linked to the frequency of solitary or interpersonal activities but may vary according to the degree and type of motivation experienced by the individuals, in relation to how self-determined they feel (Corsano et al., 2011). In fact, perceiving oneself as intrinsically motivated in the enactment of solitary behaviors is associated with several indicators of well-being and social adaptation (Beiswenger, 2008).

Furthermore, solitary experience, whether objective or subjective, and the contexts in which it is experienced, can vary according to specific developmental period of the individual (Larson, 1990). For example, while in adolescence peer- and parent-related loneliness are relevant (Majorano et al., 2015), in young adulthood other relational contexts such as romantic relationships (Furman & Collibee, 2014), work and preparation for adulthood become more salient (Kohútová et al., 2021). Compared to early adolescents, late adolescents and young adults seem to seek more alone time and to experience it more positively (Long & Averill, 2003), even if they show higher levels of loneliness than older ages (Hawkley et al., 2022). In fact, young adults are likely to exhibit needs for establishing close bonds, and when their actual social interactions do not align with these needs, they may experience high levels of loneliness (Adamczyk, 2018; Gallardo et al., 2018), which is increasingly prevalent among this population (Buecker et al., 2021).

Although solitary experiences are distinct from each other, previous research have examined the role of few forms of solitary experiences in PSMU. A recent systematic review, that investigated the relationships between loneliness and patterns of SM use, has found that there is some evidence showing a positive association between loneliness and PSMU among young adults (O’Day & Heimberg, 2021). Another systematic review (Ahmed & Vaghefi, 2021) and a meta-analysis (Zhang et al., 2022) supported the existence of this significant association in the general population. These findings might be explained through the Compensatory Internet Use Theory (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014). From this framework, psychosocial difficulties and psychological vulnerabilities might lead individuals to excessively engage in SM use as a coping strategy (Costanzo et al., 2021; Musetti et al., 2021, 2022; Russo et al., 2022). However, these patterns of SM use might constitute a maladaptive strategy that impairs individuals’ functioning (Ciudad-Fernández et al., 2024). Therefore, loneliness, and other psychosocial difficulties, might lead young adults to PSMU, that in turns might reduce the quantity and quality of face-to-face interactions with others and, thus, maintain or reinforce feelings of loneliness (Kim et al., 2009; Nowland et al., 2018). Also, young adults exhibiting PSMU might be more prone to use SM passively (e.g., monitoring the lives of others without interacting socially; viewing updates and profiles of others without actively engaging), perceiving themselves as socially isolated and alone (Zhao, 2006).

It is noteworthy that some recent findings provide additional insight on the relationships between solitary experiences and PSMU among young adults. Hill and Zheng (2018) have found a positive association between the desire for SM use and the desire for solitary behaviors; this suggests that young adults who tend to use SM prefer more isolation and time to themselves. Furthermore, it has been found that young adults with low face-to-face social support seek more social support through SM, potentially leading to an increased risk of PSMU (Meshi & Ellithorpe, 2021). These findings support the needs to better understand how solitary experiences might lead individuals to engage in PSMU. In line with Schimmenti’s model (2023), the problematic use of Internet platforms, including PSMU, can be conceptualized as a means to satisfy specific needs, which could involve different solitary experiences. Thus, it is essential to consider the role of different forms of solitary experiences in PSMU.

1.2. Aims

To date, two systematic reviews (Ahmed & Vaghefi, 2021; O’Day & Heimberg, 2021) and a meta-analysis (Zhang et al., 2022) have considered loneliness in relation to PSMU. However, no systematic review has comprehensively examined additional forms of solitary experiences from a multidimensional perspective, such as aloneness or solitude, limiting the possibility of a deep understanding of the topic. Indeed, it could be relevant to understand how different forms of solitary experiences relate to PSMU; for instance, according to the Compensatory Internet Use Theory (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014), individuals might problematically use SM to cope with psychosocial challenges such as loneliness. However, it is unclear if PSMU differs between lonely individuals who are objectively alone and those who often engage in social interactions. Furthermore, no review has examined the potential role of positive solitude in preventing PSMU. Therefore, with this systematic review we intend to comprehensively outline all the literature that has considered the association between specific solitary experiences and PSMU in young adults. To fill the gaps in the literature: a) we aim to comprehensively examine associations between a range of solitary experiences (i.e., loneliness, aloneness, solitude, social isolation, and social withdrawal) and PSMU; b) we will examine the role of potential mediators. The findings of this systematic review could have relevant implications for future studies and personalized interventions for young adults at risk of PSMU.

2. Method

This study was based on the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement (Page et al., 2021). For a thorough and transparent methodological procedure, the protocol of this review was registered on the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews (PROSPERO) on 10 December 2022 (registration number: CRD42022378205).

2.1. Information sources and search strategy

The systematic literature search began on December 1, 2022, by two authors (MP and AM). The review was updated through a second literature search on June 30, 2023. Articles were found from the Scopus, Web of Science, PubMed and PsycINFO web databases. The search strategy used consisted of a combination of key elements identified to answer the search question of this review, using Boolean AND/OR operators, and restricted to titles, abstracts and keywords.

The search string was: (“grindr” OR “spotify” OR “music stream*” OR “pinterest” OR “reddit” OR “tinder” OR “whatsapp” OR “facebook” OR “instagram” OR “twitter” OR “youtube” OR “snapchat” OR “tiktok” OR “social media” OR “social network*”) AND (“lonel*” OR “alone*” OR “solit*” OR “social isolat*” OR “social withdraw*”) AND (“problematic*” OR “pathologic*” OR “disorder*” OR “misus* OR “overus*” OR “compulsive*” OR “excessive*” OR “addict*” OR “abus*”). No further filter was applied.

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Studies were required to meet all the following inclusion criteria (IC):

IC1: contain quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods approaches (empirical data);

IC2: use a measure of solitary experience (loneliness, aloneness, solitude, social withdrawal, isolation);

IC3: use a measure of PSMU;

IC4: date of publication between January 1, 2004 and June 30, 2023 (this is because Facebook was launched in 2004 and it is unlikely that studies conducted before 2004 included measures of PSMU);

IC5: published in peer-reviewed journals, written in English;

IC6: participants aged between 18 and 30 years.

Studies were excluded if they met one of the following exclusion criteria (EX):

EX1: review papers, case reports, commentaries, editorials, meeting abstracts.

2.3. Identification and selection of empirical studies

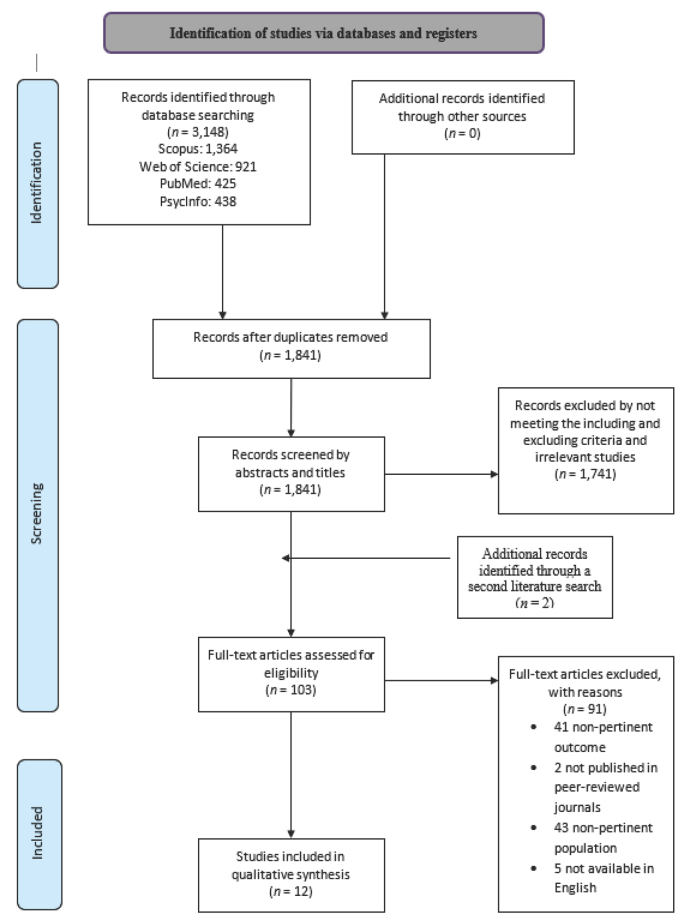

Once all articles were retrieved from each database, they were then exported to the Rayyan systematic review website (https://www.rayyan.ai). After removal of duplicates, two authors (MP and AM) independently assessed titles and abstracts to select relevant studies. After this preliminary screening, the results were compared and, in case of disagreements, the two authors resolved them by consensus. The suitability assessment was subsequently carried out using the full texts. All studies that met the inclusion criteria and did not meet any of the exclusion criteria were analyzed for data extraction (figure 1).

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of the search strategy: Modified from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses statement flow diagram (Page et al., 2021)

2.4. Risk of bias

The Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (National Institutes of Health, 2017) was used for the analysis and assessment of the risk of bias. This tool comprises 14 items and the assessment includes: questions on the clarity of the study, justification of sample size, participation rate, representativeness of the target population, sample selection, validity and reliability of measures, and consideration of possible confounding variables. Each item was answered Yes, No or Not applicable, establishing the following score ranges for each study: 0-5 = poor quality, 6-9 = fair quality and 10-14 = good quality. Subsequently, two authors (MP and AM) performed the quality assessment independently and then compared the quality judgements for each study; for this purpose, a score was assigned to each quality judgement, i.e., poor (0), fair (1) and good (2). These scores were useful in order to calculate the degree of agreement between reviewers and to assign a final quality rate to each study, considering 0-0.5 = poor quality, 1-1.5 = fair quality and 2 = good quality (see Wolford-Clevenger et al., 2018). The results of the qualitative assessment are presented in Appendix A (see table S1).

2.5. Synthesis of results

The data extraction was performed by two authors (MP and AM). The data collected from each full-text study were about general information of the study, methodology, measures and key findings. The data extracted were synthesized in the following domains: Author(s); Year; Document type; Location; Study design (e.g., cross-sectional survey); Sample characteristics; Measurement instruments for solitary experience; Solitary experience theoretical model; Measurement instruments for problematic social media use; Key findings.

3. Results

3.1. Overview of empirical studies

The initial database search found 3,148 articles. After removing duplicate records, 1,841 articles were considered. Afterwards, examination of the titles and abstracts identified 103 studies that met the inclusion criteria. After reviewing the full text, a further 91 articles were excluded, while 12 were deemed suitable by the authors for our systematic review.

3.2. Characteristics of studies

Of the 12 studies included in our review, 11 were cross-sectional and one longitudinal; these studies were conducted on a total of 4,009 participants (M = 334), with sample sizes ranging from 114 to 619 (see table 1). The proportion of women was 61.2%, while that of men was 38.8% (information not available for two samples), and all studies but one included both males and females. The age of the participants, consistent with the age criterion selected for our systematic review, ranged from 18 to 30 years with M = 20.84 and SD = 1.49 (partial or no information available for four samples). Finally, four studies were conducted in East Asia (India, Malaysia, China), three in Europe (Hungary, Poland, United Kingdom), two in the United States, two in Saudi Arabia and one in Turkey.

Table 1.

Studies on problematic social media use and solitary experience included in the review

| Authors (year) | Country | Design | Sample characteristics N (gender distribution) Age = range (M, SD) | Solitary experience theoretical model | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bakry et al. (2022) | Saudi Arabia | Cross sectional | N = 302 (gender = na) Age = 19-25 (M = na, SD = na) | General loneliness | Correlation analysis Loneliness was positively linked with social media addiction (r = .361, p < .001). |

| Casingcasing et al. (2023) | United Kingdom | Cross sectional |

N = 280 (81.8% females) Age = 18-25 (M = 22.01, SD = 3.76) |

General loneliness |

Correlation analysis Facebook addiction was positively linked with loneliness (r = .293, p < .01). |

| Cudo et al. (2020) | Poland | Cross sectional |

N = 619 (91.8% females) Age = 18-30 (M = 21.34, SD = 2.41) |

Early maladaptive schemas of experience solitary |

Hierarchical regression analysis Problematic Facebook use was negatively linked with early maladaptive schema of social isolation/alienation (β = −.19) and was not linked with maladaptive schema of abandonment (β = −.06, ns). |

| Hammad & Awed (2023) | Saudi Arabia | Cross sectional |

N = 330 (gender = na) Age = 19-23 (M = 21.1, SD = 2.52) |

General loneliness |

Regression analysis Social media addiction was positively linked with loneliness (β = .114, p = .01). |

| Hamsa et al. (2020) | India | Cross sectional |

N = 500 (100% females) Age = 18-25 (M = 21.05, SD = 0.79) |

Contextual loneliness (context of romantic/sexual relationship, relationship with family and friends) |

Correlation analysis WhatsApp dependence was weakly and negatively linked with loneliness in the context of romantic/sexual relationship, relationship with family, friends at the edge of significance (r = -.026, p = .05). |

| Kircaburun et al. (2020) | Turkey | Cross sectional |

N = 460 (61% females) Age = 18-26 (M = 19.74, SD = 1.49) |

General loneliness |

Correlation analysis, Structural Equation Model PSMU was positively associate with loneliness in bivariate (r = .26, p < .001) but not multivariate analysis. |

| Piko et al. (2022) | Hungary | Cross sectional |

N = 303 (78.7% females) Age = 18-30 (M = 23.2, SD = 2.7) |

General loneliness |

Zero-order correlations Social media addiction was positively linked with loneliness (r = .18, p < .01). |

| Ponnusamy et al. (2020) | Malaysia | Cross sectional |

N = 364 (51.1% females) Age = 19-26 (M = na, SD = na) |

General loneliness |

Partial Least Square path modelling Instagram addiction had a positive influence on loneliness (β = .211, p < .01). |

| Rajesh & Rangaiah (2020) | India | Cross sectional |

N = 114 (31.6% females) Age = 18-30 (M = na, SD = na) |

General loneliness |

Pearson product-moment correlation, regression analysis Loneliness was positively linked with Facebook addiction (r = .38, p < .01). Loneliness positively and significantly predicted Facebook addiction (β = .38, t = 4.37, p < .001). |

| Tuck & Thompson (2021) | United States | Cross sectional |

N = 176 (54.0% females) Age = 18-29 (M = 20.00, SD = 1.26) |

General loneliness |

Hierarchical regression analysis, Pearson zero-order correlations Social networking sites addiction positively predicted loneliness during COVID-19 (β = .50, t = 2.78, p = .006). Change in social networking sites addiction during COVID-19 was not associated with loneliness (r = .12, p = .31). |

| Yang et al. (2020) | United States | Longitu- dinal |

Nt1 = 219 (74% females) nt2 = 136 (74% females) Age = 18-23 (M = 18.29, SD = 0.75) |

General loneliness |

Correlation analysis, Structural Equation Model Loneliness at T2 was not significantly associated with compulsive social media use at T1 (r = 0.02, ns) and at T2 (r = .12, ns). Rumination at T1 did not mediate the association between loneliness at T1 and compulsive social media use at T2 (β = .03, p = .176). |

| Zhou & Leung (2012) | China | Cross sectional |

N = 342 (67.8% females) Age = 18-22 (M = na, SD = na) |

General loneliness |

Regression analysis Loneliness positively predicted social networking sites-game addiction (β = .09, p < .05). |

The measurement instruments used in the studies, the frequency of their use and the construct dimensions evaluated are shown in table 2. Seven different instruments were used to assess PSMU; specifically, six studies used one of Bergen’s addiction scales (Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale [BFAS; Andreassen et al., 2012], Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale modified for WhatsApp use [Hamsa et al., 2020], Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale [BSMAS; Andreassen et al., 2016], Bergen Instagram Addiction Scale [BIAS; Ballarotto et al., 2021]), which were found to be the most widely used instrument for detecting PSMU.

Table 2.

Measurement instruments and dimensions listed in the included studies (n = 12)

| Measures instruments | Construct dimensions | Studies | N of studies | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Problematic Social Media Use | Bergen Addiction Scales (i.e., the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale [BFAS; Andreassen et al., 2012], the Bergen Facebook Addiction Scale modified for WhatsApp usage [Hamsa et al. 2020], the Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale [BSMAS; Andreassen et al., 2016], the Bergen Instagram Addiction Scale [BIAS; Ballarotto et al., 2021]) | Salience, mood modification, tolerance, withdrawal, conflict, relapse | Hammad & Awed (2023); Hamsa et al. (2020); Piko et al. (2022); Ponnusamy et al. (2020); Rajesh & Rangaiah (2020); Tuck & Thompson (2021) | 6 |

| Compulsive Internet Use Subscale (Caplan, 2010); Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS; Meerkerk et al., 2009) | Adapted for social media context. Impulsive, unregulated thoughts about and social media use that is out of the user’s control | Yang et al. (2020) | 1 | |

| Facebook Addiction Scale (FAS; Koc & Gulyagci, 2013) | Cognitive and behavioral salience, conflict with other activities, euphoria, loss of control, withdrawal, relapse and reinstatement | Casingcasing et al. (2023) | 1 | |

| Facebook Intrusion Questionnaire (FIQ; Elphinston & Noller, 2011) | Cognitive salience, behavioral salience, interpersonal conflict, conflict with other activities, euphoria, loss of control, withdrawal, relapse and reinstatement | Cudo et al. (2020) | 1 | |

| Internet Addiction Test (IAT;K. Young, 1996) | Adapted to Social networking sites-game addiction. Unidimensional construct | Zhou & Leung (2012) | 1 | |

| Social Media Addiction Scale (SMAS; Al-Menayes, 2015) | Preoccupation, mood modification, relapse, conflict/problems | Bakry et al. (2022) | 1 | |

| Social Media Use Questionnaire (SMUQ; Xanidis and Brignell, 2016) | Withdrawal and compulsion | Kircaburun et al. (2020) | 1 | |

| Solitary Experience | Differential Loneliness Scale – Short student version (DLS- SSV; Schimdt & Sermat, 1983) | Loneliness in in the context of romantic/sexual relationships, friendships, relationships with family and relationships with larger groups or the community | Hamsa et al. (2020) | 1 |

| De Jong Gierveld 6-Item Loneliness Scale (De Jong Gierveld & Van Tilburg, 2010) | Social and emotional loneliness | Hammad & Awed (2023) | 1 | |

| Five-Item Loneliness Scale (Baek et al., 2014; adapted from Russell’s UCLA Loneliness Scale [1996]) | Loneliness | Casingcasing et al. (2023) | 1 | |

| Four-Item Loneliness Scale (Eskin, 2001; adapted from Russell et al.’s UCLA Loneliness Scale [1980]) | Loneliness | Kircaburun et al. (2020) | 1 | |

| Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1978); UCLA Loneliness Scale – version 3 (Russel et al., 1996) | Loneliness | Bakry et al. (2022); Piko et al. (2022); Ponnusamy et al. (2020); Rajesh & Rangaiah (2020); Tuck & Thompson (2021); Zhou & Leung (2012) | 6 | |

| Three-Item Loneliness Scale (Hughes et al., 2004) | Loneliness | Yang et al. (2020) | 1 | |

| Young Schema Questionnaire – Short Form 3 (YSQ–S3;Young, 2005) | Early maladaptive schemas of abandonment and social isolation/alienation | Cudo et al. (2020) | 1 |

Ten of the articles included in this review adopted a general model of loneliness; this phenomenon was assessed using seven different instruments, with the Revised UCLA Loneliness Scale (Russell et al., 1978), including the derived UCLA Loneliness Scale – version 3 (Russell, 1996), being the most frequently used self-report instrument, i.e., in six studies. Only one study adopted a contextual model of loneliness (Hamsa et al., 2020), considering the context of romantic/sexual relationship, relationship with family and friends; these contexts were assessed with the Differential Loneliness Scale – Short student version (DLS-SSV; Schmidt & Sermat, 1983).

3.3. Quality assessment

The quality assessment of the studies included in this systematic review was carried out using the Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies (National Institutes of Health, 2017). Firstly, a degree of agreement between the reviewers of 75% was calculated, which shows a good degree of agreement between the two authors. Regarding the quality of the individual studies, five studies (41.7% of the total) were rated as poor quality, six studies (50% of the total) had fair quality, and one study had good quality (8.3% of the total). The average quality of the studies was 0.79 (SD = 0.54) on a scale of 0-2.

3.4. Main findings

3.4.1. Direct associations between solitary experience and problematic social media use

3.4.1.1. General model of loneliness

Of the total studies included in this systematic review, 10 adopted a general model of loneliness, noting this phenomenon as a unique dimension. Nine of these studies found a cross-sectional positive association between loneliness and PSMU (Bakry et al., 2022; Casingcasing et al., 2023; Hammad & Awed, 2023; Kircaburun et al., 2020; Piko et al., 2022; Ponnusamy et al., 2020; Rajesh & Rangaiah, 2020; Tuck & Thompson, 2021; Zhou & Leung, 2012). Among these, one study (Kircaburun et al., 2020) found that loneliness was positively associated with PSMU through Pearson’s correlations, and that loneliness was a not significant predictor of PSMU through a multivariate analysis comprising several potential predictors (e.g., loneliness). Finally, no longitudinal association was found between loneliness and PSMU (Yang et al., 2020).

3.4.1.2. Contextual model of loneliness

Only one study, among those included in our review, adopted a contextual model of loneliness, observing this phenomenon as multicomponent (Hamsa et al., 2020). The results showed that loneliness in the context of romantic/sexual relationships, relationships with family and with friends was negatively and weakly associated with PSMU in a sample of female young adults.

3.4.1.3. Early maladaptive schemas of solitary experience

A study by Cudo et al. (2020) investigated the relationship between early maladaptive schemas (EMS; i.e., time-stable and cognitive-emotional representations that develop in childhood and are reworked throughout an individual’s life, determining information about themselves and the world; Young, 2014) and the problematic use of a specific SM platform, that is Facebook. Despite bivariate correlation analyses showed that problematic Facebook use was not significantly associated with the social isolation/alienation schema (i.e., the representation that the subject is different from others and excluded from society) and significantly associated with the abandonment schema (i.e., the representation that others are incapable of providing emotional support because they are precarious; Cudo et al., 2020), a multivariate analysis found that social isolation/alienation schema was a significant negative predictor of problematic Facebook use.

3.4.2. Mediators of the associations between solitary experience and problematic social media use

The only longitudinal study found that rumination (i.e., a type of attention to one’s thoughts characterized by negative valence, usually focused on negative experiences) did not mediate the association between loneliness and PSMU (Yang et al., 2020).

4. Discussion

The aim of this systematic review was to outline the existing studies that have investigated direct and indirect associations between different forms of solitary experiences and PSMU in the young adult population. All the studies included in our review focused only on subjective forms of solitary experiences. They all considered loneliness, which is the negative emotional aspect, except for one study that considered (cognitive-emotional) early schemas related to solitary experiences. The current review shows that, among young adults, general loneliness is positively associated with PSMU in cross-sectional but not in the longitudinal study. Notably, there is some evidence suggesting that general loneliness might have no significant effects on PSMU, taking into account the effects of other variables on PSMU (Kircaburun et al., 2020). In addition, one study in the present review (Hamsa et al., 2020) found a negative negligible association between contextual loneliness and PSMU. Furthermore, no studies were found on the relationship between PSMU and other aspects of solitary experiences, such as aloneness and positive solitude. These findings highlight that further research is needed to investigate the relationships between PSMU and specific forms of solitary experiences. In fact, a general and unidimensional perspective on solitary experiences is too simplifying as it is 1) unable to consider different and specific forms of solitary experiences and 2) potentially misleading as it could limit the understanding of the processes involved in PSMU. For example, future studies could investigate whether transient or chronic forms of loneliness, as well as its contextual forms, could be related to PSMU differently, or whether aloneness is associated with PSMU regardless of high levels of loneliness. In addition, considering solitude as a subjective solitary experience different from loneliness might be helpful in understanding if this could be a protective factor toward the development of PSMU. Thus, this review represents an important research and conceptual call to consider solitary experience as multidimensional phenomenon, supporting skepticism toward a generic perspective to solitary experience, which risks missing the important facets of these specific experiences in relation to PSMU.

4.1. Findings based on general model of loneliness

All the reviewed cross-sectional studies found a positive correlation between general loneliness and PSMU related to social networking sites (Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, Twitter), social networking sites-games and WhatsApp. These findings are consistent and extend the results of previous systematic reviews (Ahmed & Vaghefi, 2021; O’Day & Heimberg, 2021) and the meta-analysis by Zhang et al. (2022) focused on a broader age range of SM users.

However, Kircaburun and colleagues (2020) have found that general loneliness may have no effects on PSMU, when other potential predictors are concurrently investigated. This suggests that other variables might be more relevant (e.g., depression) than loneliness in fostering PSMU. Also, it is noteworthy that Kircaburun et al. (2020) have assessed a transient form of general loneliness through a shortened 4-item version of the UCLA – Loneliness Scale (Eskin, 2001) rather than a chronic form of it (i.e., a trait-like variable). Previous research has shown that chronic loneliness is associated with higher levels of psychopathology compared to transient loneliness (Hawkley & Cacioppo, 2010; Martín-María et al., 2020). Therefore, further studies could investigate whether chronic loneliness is significantly associated with PSMU, even when controlling for personality traits and psychopathology.

Furthermore, the only longitudinal study included in our review found no association between loneliness and PSMU (Yang et al., 2020). Nevertheless, other studies have found that general loneliness may be longitudinally associated with PSMU in different age groups (Marttila et al., 2021; Wu et al., 2024). These inconsistent findings might be partly explained by the different measures assessing loneliness that have been employed in these studies. Thus, the long-term relationship between loneliness and PSMU deserves further investigation, differentiating loneliness based on its contextual factors and chronic or transient stability.

4.2. Findings based on contextual model of loneliness

One of the reviewed studies found a negative negligible correlation between contextual loneliness (i.e., loneliness in romantic/sexual, friends and family relationship contexts) and PSMU in the context of WhatsApp use among young adults (Hamsa et al., 2020). Interestingly, this finding contrasts with the results of a reviewed study (Bakry et al., 2022) and Nagar et al. (2021), who found that general loneliness positively predicts problematic WhatsApp use. Adopting caution, as the correlation found is very weak, this divergence could be explained by the loneliness’ model used, suggesting that loneliness when measured contextually correlates differently with PSMU. Thus, assessing different forms of loneliness might provide more accurate information on the processes involved in PSMU. In fact, in the case of WhatsApp use, some young adults, in order to compensate (Kardefelt-Winther, 2014) their psychosocial difficulties (e.g., loneliness), may tend to connect through instant messaging apps, maintaining or reinforcing the general perception of those negative states, but at the same time decreasing some specific contexts of loneliness. A study by Bardi and Brady (2010) showed that very often people are motivated to use WhatsApp to decrease the perception of loneliness. According to stimulation hypothesis, which argues that the use of SM and the Internet could enrich existing relationships, having a positive impact on personal well-being (Bryant et al., 2006), problematic WhatsApp use could decrease some specific contexts of loneliness (e.g., romantic/sexual and friendship contexts) as it would increase perceptions of stable bonds, fostering a group identity (Kaye & Quinn, 2020). In fact, it should be noted that WhatsApp, more than other SM, is characterized by ease and immediacy of communication and a greater sense of presence of others (Karapanos et al., 2016), and by the possibility of immediate participation in group chats, which could foster a sense of inclusion and belonging.

4.3. Findings based on early maladaptive schemas of solitary experience

One of the reviewed studies has found that problematic Facebook use was positively correlated with EMS of abandonment and that it was not significantly associated with EMS of social isolation/alienation. However, multivariate analysis showed that EMS of social isolation/alienation was a significant predictor of decreased levels of problematic Facebook use and that EMS of abandonment was not a significant predictor, when their effects were controlled for the characteristics of Facebook use (Cudo et al., 2020). It is important consider that unlike loneliness, which is an emotional negative state (state-like variable), EMS are time-stable schemas (trait-like variable) formed during childhood (Young, 2014). These results suggest that the features of Facebook might be highly relevant to explain the relationships between specific EMS and problematic patterns use of this SM platform. For example, Cudo et al. (2020) found that the EMS of approval seeking (i.e., the belief that social approval is needed to perceive oneself as valuable) was a significant predictor of increased problematic Facebook use. Therefore, among young adults, low levels of EMS of social isolation/ alienation and high levels of approval seeking could associate with a greater orientation of the individual towards positive feedback by others through Facebook, displacing the time spent from their offline relationships and significantly increasing their SM use (Kraut et al., 1998).

4.4. Mediators of the relationships between solitary experience and problematic social media use

Our review shows that general loneliness was not longitudinally associated directly or indirectly (via rumination) with PSMU in young adult population (Yang et al., 2020).

4.5. Implications

First of all, the results of the current systematic review have some important research implications. In fact, all studies conducted on the relationship between PSMU and solitary experience in young adults have focused only on subjective forms of the latter and most of them have considered them as a unitary construct, adopting a general model of loneliness. The only study that considered loneliness from a contextual perspective (Hamsa et al., 2020) has found different results from studies that adopted a general model, supporting the importance by examining the role of different forms of solitary experience. Consequently, our review underscores the necessity of embracing a multidimensional perspective on solitary experiences to enhance the understanding of their interplay with PSMU. Without this research and conceptual perspective, there would be a risk of missing the relationships with the different and specific solitary experiences, such as the various forms of loneliness, as well as the objective dimension (i.e., aloneness) and the subjective and positive dimension (i.e., solitude).

In addition to research implications, there are also socio-educational and clinical ones. As there is no empirical evidence which elucidates the causality of the relationship between general loneliness and PSMU, it may be important to intervene in both aspects. The positive association between PSMU and loneliness among young adults should, in fact, lead to greater awareness on the part of care professions and institutions. For example, youth policies should focus on providing effective socializing environments for young adults, which can be important alternatives to prevent loneliness and PSMU. Whereas from a prevention perspective, parents and figures such as teachers, educators and social workers should promote from the early school years onwards, a conscious SM use that can enrich and create bonds, which can offset states of loneliness (Blasko & Castelli, 2022). Indeed, training these professionals on psychosocial aspects of mental health in relation to the use of technology, is crucial for the prevention of the development of PSMU. This could result in social and emotional learning-based programs (Durlak et al., 2011) at schools and universities, as well as the creation of prevention projects on PSMU, on its assessment and its consequences; awareness of negative feelings related to loneliness; the creation of workshops focused on the recognition and management of SM use (Bakry et al., 2022).

Beyond the preventive context, it is possible to suggest targeted interventions for young people showing PSMU and loneliness. For example, a recent meta-analysis observed that in young adults, group interventions focusing on social and emotional skills had the best clinical outcomes for reducing loneliness compared with other types of interventions (Eccles & Qualter, 2021). Therefore, clinical actions could be focused on emotion management and social skills training of those young adults who feel lonely and are less experienced in creating offline social connections and support, as well as promoting online social connections and support through a conscious use of SM (O’Day & Heimberg, 2021).

4.6. Limitations

Despite the large amount of research on PSMU, we found a small number of studies (n = 12) eligible for our inclusion criteria, which could provide partial information on the topic. In fact, our research focused only on the 18-30 year old population, meaning that many of the initial articles were removed. In addition to this, an average quality of 0.79 on a scale of 0-2 was assessed, indicating a relatively low-quality score, which may have affected the results of our review. Therefore, a series of limitations should be highlighted in the reviewed studies. Firstly, most of these (11 out of 12) are cross-sectional studies, limiting the observation of the temporal relationships between PSMU and solitary experience. The only longitudinal study did not find a relationship between PSMU and general loneliness at a follow-up of 3.6 months between time 1 and time 2. However, it should be noted that the reduced longitudinal follow-up of this study could make it difficult to detect changes in the variables over time. Moreover, little is known about the relationship between PSMU and the different contexts of loneliness, as it was considered by only one study among those included. Indeed, it is essential to consider the different contexts of loneliness in young adults, as some of these (e.g., romantic/sexual contexts) are more salient than others (Furman & Collibee, 2014). In line with this, 11 out of 12 studies in our review also focused only on young adult university students, not including neither workers nor those without employment or not in education. The homogeneity of the population may limit the external validity of the results, as young adult workers may show feelings of loneliness specific to their work context (Wright & Silard, 2022), which might have different implications in relation to SM use, and those without employment or not in education could be a vulnerable and interesting group regarding the relationship between PSMU and solitary experience. Another limitation is that only one study considered a potential mediating mechanism between loneliness and PSMU with insignificant results. This makes it hard to answer the second objective of our systematic review.

4.7. Conclusion and future directions

This was the first study aimed at systematically reviewing the relationship between different forms of solitary experience and PSMU among young adults. Our systematic review showed a restricted focus of the literature in this area, as all the studies considered only subjective and negative dimensions of solitary experience (i.e., loneliness and social isolation/alienation EMS), and among them almost all have considered loneliness through a general model. Moreover, the objective (i.e., aloneness) and positive (i.e., solitude) dimensions of solitary experience have not been examined in the studies carried out to date, limiting our understanding of the underlying or related processes of PSMU. It is crucial for future research to consider other dimensions of solitary experience in order to broaden the possibility of interventions oriented to PSMU. For example, given that solitude is associated with various positive outcomes (Long et al., 2003; Nguyen et al., 2018; Thomas, 2023; Weinstein et al., 2021; White et al., 2022), future research could focus on how it is linked to different modalities of SM use. It is possible that using SM seeking experiences of solitude is a protective factor for the development of problematic SM or Internet use. In this regard, future research could investigate whether loneliness and solitude may act as mediators between psychosocial vulnerabilities and PSMU. Similarly, in line with Self Determination Theory, further studies could explore the relationships between motivations for interpersonal and solitary behaviors, motivations for SM use, and PSMU, to shed light on the underlying motives leading to PMSU. In addition, it could be that promoting “solitude skills” (Thomas, 2021) through validation of one’s solitary activities in educational settings, could benefit and protect from loneliness and PSMU. These observations highlight the need to gather new evidence, in order to develop new interventions focusing both on PSMU and the well-being, especially among young adults, who seems to seek solitude more than other age groups (Long & Averill, 2003; Nguyen et al., 2019; Thomas & Azmitia, 2019). Moreover, future research should clarify the role of subjective and objective solitary experiences in relation to PSMU. For example, studies employing a centered-person approach could be implemented to identify individuals based on both subjective dimensions (e.g., loneliness, solitude) and objective dimensions (e.g., aloneness) of solitary experience, and investigate their SM usages. Furthermore, our study showed that among young adults PSMU was cross-sectionally and positively associated with general loneliness and, in the case of problematic WhatsApp use, negatively correlated with contextual loneliness. Further studies are needed to investigate the relationship between different contexts of solitary experience in relation to PSMU. It could be that the use of certain SM, such as dating apps (e.g., Tinder, Grindr) could be facilitated by specific contexts of loneliness, such as the romantic/sexual one, salient for the developmental period of young adulthood (Furman & Collibee, 2014). In line with this, it would also be important to observe specific contexts of solitude, understanding whether a romantic/sexual solitude could be a protective factor towards PSMU related to dating apps.

A negative association emerged between the EMS of social isolation/alienation and the problematic use of a specific SM platform, that is Facebook. It would be important to investigate the hypothetical association between different EMS and the seeking for social connectedness, understanding how individuals displace their relationships, differentiating between offline and online social support, through longitudinal study design. In accordance with this, given that most of the studies were cross-sectional, it would be necessary to carry out studies with longer follow-ups and with more time points that allow for disentangling the temporal relationships between SM use and solitary experience, to better outline causal relations.

In addition, not enough studies have been found to understand the possible mediating mechanisms between the solitary experience and PSMU among young adults. The unidimensional approach to solitary experience might not allow scholars to adequately investigate the potentials mediator variables of the relationships between the solitary experience and PSMU; in this vein, adopting a perspective that can differentiate specific forms of solitary experiences is functional in exploring potential mediator variables, in order to identify further factors on which intervention is possible. Moreover, little is known about the moderator variables that might dampen or strengthen the relationship between solitary experience and PSMU. For example, high levels of certain personality traits (e.g., narcissism or avoidant personality) or other associated factors (e.g., fear of missing out; Fumagalli et al., 2021) could weaken or strengthen the relationship between PSMU and solitary experiences. In addition, nowadays there are a large number of SM, including dating (Tinder or Grindr), posting photos or videos (e.g., Instagram, TikTok) or interacting with others via online games. The different uses of these applications could moderate the relationship between the PSMU and the dimensions of solitary experiences.

Hence, it is essential that future research should consider the wide spectrum of solitary experience, in relation to diverse life contexts, in order to broaden knowledge of how PSMU is related to these dimensions and to frame the socio-educational and clinical implications on PSMU.

References

- Adamczyk, K. (2018). Direct and indirect effects of relationship status through unmet need to belong and fear of being single on young adults’ romantic loneliness. Personality and Individual Differences, 124, 124–129. 10.1016/j.paid.2017.12.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, E., & Vaghefi, I. (2021). Social media addiction: A systematic review through cognitive-behavior model of pathological use. In Proceedings of the 54th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, 6681–6690. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/71422

- Aichner, T., Grünfelder, M., Maurer, O., & Jegeni, D. (2021). Twenty-five years of social media: A review of social media applications and definitions from 1994 to 2019. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 24(4), 215–222. 10.1089/cyber.2020.0134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Al-Menayes, J. (2015). Psychometric properties and validation of the Arabic Social Media Addiction Scale. Journal of Addiction, 2015(1), 291743. 10.1155/2015/291743 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association (2022). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed., text rev.). 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425787 [DOI]

- Andreassen, C. S., Billieux, J., Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., Demetrovics, Z., Mazzoni, E., & Pallesen, S. (2016). The relationship between addictive use of social media and video games and symptoms of psychiatric disorders: A large-scale cross-sectional study. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 30(2), 252–262. 10.1037/adb0000160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andreassen, C. S., TorbjØrn, T., Brunborg, G. S., & Pallesen, S. (2012). Development of a Facebook Addiction Scale. Psychological Reports, 110(2), 501–517. 10.2466/02.09.18.PR0.110.2.501-517 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asher, S. R., & Paquette, J. A. (2003). Loneliness and peer relations in childhood. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 12(3), 75–78. 10.1111/1467-8721.01233 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baek, Y. M., Cho, Y., & Kim, H. (2014). Attachment style and its influence on the activities, motives, and consequences of SNS use. Journal of Broadcasting & Electronic Media, 58(4), 522–541. 10.1080/08838151.2014.966362 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bakry, H., Almater, A., Alslami, D., Ajaj, H., Alsowayan, R., Almutairi, A., & Almoayad, F. (2022). Social media usage and loneliness among Princess Nourah University medical students. Middle East Current Psychiatry, 29(50), 1–8. 10.1186/s43045-022-00217-w [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ballarotto, G., Volpi, B., & Tambelli, R. (2021). Adolescent attachment to parents and peers and the use of Instagram: The mediation role of psychopathological risk. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(8), 3965. 10.3390/ijerph18083965 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbar, S., Haddad, C., Sacre, H., Dagher, D., Akel, M., Kheir, N., Salameh, P., Hallit, S., & Obeid, S. (2021). Factors associated with problematic social media use among a sample of Lebanese adults: The mediating role of emotional intelligence. Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 57(3), 1313–1322. 10.1111/ppc.12692 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardi, C. A., & Brady, M. F. (2010). Why shy people use instant messaging: Loneliness and other motives. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(6), 1722–1726. 10.1016/j.chb.2010.06.021 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R. F., & Leary, M. R. (1995). The need to belong: Desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychological Bulletin, 117, 497–529. 10.1037/0033-2909.117.3.497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beiswenger, K. L. (2008). Autonomy for solitary and interpersonal behavior in adolescence: Exploring links with peer relatedness, well-being, and social coping (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Clark University Worchester, Massachusetts. [Google Scholar]

- Blasko, Z., & Castelli, C. (2022). Social media use and loneliness. Publications Ofice of the European Union. https://data.europa.eu/doi/10.2760/700283 [Google Scholar]

- Bryant, J. A., Sanders-Jackson, A., & Smallwood, A. M. K. (2006). IMing, text messaging, and adolescent social networks. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 11(2), 577–592. 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2006.00028.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Buecker, S., Mund, M., Chwastek, S., Sostmann, M., & Luhmann, M. (2021). Is loneliness in emerging adults increasing over time? A preregistered cross-temporal meta-analysis and systematic review. Psychological Bulletin, 147(8), 787–805. 10.1037/bul0000332 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, S. E. (2010). Theory and measurement of generalized problematic Internet use: A two-step approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), 1089–1097. 10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.012 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casingcasing, M. L. S., Nuyens, F. M., Griffiths, M. D., & Park, M. S. (2023). Does social comparison and Facebook addiction lead to negative mental health? A pilot study of emerging adults using structural equation modelling. Journal of Technology in Behavioral Science, 8(1), 69–78. 10.1007/s41347-022-00289-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, C., Lau, Y. C., Chan, L., & Luk, J. W. (2021). Prevalence of social media addiction across 32 nations: Meta-analysis with subgroup analysis of classification schemes and cultural values. Addictive Behaviors, 117, 106845. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ciudad-Fernández, V., Zarco-Alpuente, A., Escrivá-Martínez, T., Herrero, R., & Baños, R. (2024). How adolescents lose control over social networks: A process-based approach to problematic social network use. Addictive Behaviors, 154, 108003. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2024.108003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coplan, R. J., Prakash, K., O'Neil, K., & Armer, M. (2004). Do you “want” to play? Distinguishing between conflicted shyness and social disinterest in early childhood. Developmental Psychology, 40(2), 244. 10.1037/0012-1649.40.2.244 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corsano, P., Majorano, M., Michelini, G., & Musetti, A. (2011). Solitudine e autodeterminazione in adolescenza [Loneliness and self-determination during adolescence]. Ricerche di Psicologia, 4, 473–498. 10.3280/RIP2011-004003 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Costanzo, A., Santoro, G., Russo, S., Cassarà, M. S., Midolo, L. R., Billieux, J., & Schimmenti, A. (2021). Attached to virtual dreams: The mediating role of maladaptive daydreaming in the relationship between attachment styles and problematic social media use. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 209(9), 656–664. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001356 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coyne, S. M., Padilla-Walker, L. M., & Howard, E. (2013). Emerging in a digital world: A decade review of media use, effects, and gratifications in emerging adulthood. Emerging Adulthood, 1(2), 125–137. 10.1177/2167696813479782 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer, K. M., & Barry, J. E. (1999). Conceptualizations and measures of loneliness: A comparison of subscales. Personality and Individual Differences, 27(3), 491–502. 10.1016/S0191-8869(98)00257-8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cudo, A., Mącik, D., Griffiths, M. D., & Kuss, D. J. (2020). The relationship between problematic Facebook use and early maladaptive schemas. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 9(12), 3921. 10.3390/jcm9123921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Jong Gierveld, J., & Van Tilburg, T. (2010). The De Jong Gierveld short scales for emotional and social loneliness: Tested on data from 7 countries in the UN generations and gender surveys. European Journal of Ageing, 7, 121–130. 10.1007/s10433-010-0144-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deci, E. L., & Ryan, R.M. (2000). The support of autonomy and the control of behavior. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 53, 1024–1037. 10.1037/0022-3514.53.6.1024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82(1), 405–432. 10.1111/j.1467-8624.2010.01564.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eccles, A. M., & Qualter, P. (2021). Review: Alleviating loneliness in young people – a meta-analysis of interventions. Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 26(1), 17–33. 10.1111/camh.12389 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elphinston, R. A., & Noller, P. (2011). Time to face it! Facebook intrusion and the implications for romantic jealousy and relationship satisfaction. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(11), 631–635. 10.1089/cyber.2010.0318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eskin, M. (2001). Adolescent loneliness, coping methods and the relationship of loneliness to suicidal behavior. Turkish Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 4, 5–11. [Google Scholar]

- Fournier, L., Schimmenti, A., Musetti, A., Boursier, V., Flayelle, M., Cataldo, I., Starcevic, V., & Billieux, J. (2023). Deconstructing the components model of addiction: An illustration through “addictive” use of social media. Addictive Behaviors, 143, 107694. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107694 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francesetti, G., Alcaro, A., & Settanni, M. (2020). Panic disorder: Attack of fear or acute attack of solitude? Convergences between affective neuroscience and phenomenological-Gestalt perspective. Research in Psychotherapy: Psychopathology, Process, and Outcome, 23(1), 77–87. 10.4081/ripppo.2020.421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fumagalli, E., Dolmatzian, M. B., & Shrum, L. J. (2021). Centennials, FOMO, and loneliness: An investigation of the impact of social networking and messaging/VoIP apps usage during the initial stage of the coronavirus pandemic. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 620739. 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.620739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Furman, W., & Collibee, C. (2014). A matter of timing: Developmental theories of romantic involvement and psychosocial adjustment. Development and Psychopathology, 26(4), 1149–1160. 10.1017/S0954579414000182 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galanaki, E. (2004). Are children able to distinguish among the concepts of aloneness, loneliness, and solitude? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 28(5), 435–443. 10.1080/01650250444000153 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, L. O., Martín‐Albo, J., & Barrasa, A. (2018). What leads to loneliness? An integrative model of social, motivational, and emotional approaches in adolescents. Journal of Research on Adolescence, 28(4), 839–857. 10.1111/jora.12369 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gazelle, H., & Ladd, G. W. (2003). Anxious solitude and peer exclusion: A diathesis–stress model of internalizing trajectories in childhood. Child Development, 74(1), 257–278. 10.1111/1467-8624.00534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goossens, L., Lasgaard, M., Luyckx, K., Vanhalst, J., Mathias, S., & Masy, E. (2009). Loneliness and solitude in adolescence: A confirmatory factor analysis of alternative models. Personality and Individual Differences, 47(8), 890–894. 10.1016/j.paid.2009.07.011 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths, M. D., Kuss, D. J., & Demetrovics, Z. (2014). Social networking addiction: An overview of preliminary findings. In Rosenberg K. P. & Feder L. C. (Eds.), Behavioral addictions: Criteria, evidence, and treatment (pp.119–141). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hammad, M. A., & Awed, H. S. (2023). Investigating the relationship between social media addiction and mental health. Nurture, 17(3), 149–156. 10.55951/nurture.v17i3.282 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hamsa, H., Singh, S., & Kaur, R. (2020). A cross-sectional study on patterns of social media chat usage and its association with psychiatric morbidity among nursing students. Journal of Clinical & Diagnostic Research, 14(4), 1–6. 10.7860/JCDR/2020/43023.13630 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley, L. C., Buecker, S., Kaiser, T., & Luhmann, M. (2022). Loneliness from young adulthood to old age: Explaining age differences in loneliness. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 46(1), 39–49. 10.1177/0165025420971048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2010). Loneliness matters: A theoretical and empirical review of consequences and mechanisms. Annals of Behavioral Medicine, 40(2), 218–227. 10.1007/s12160-010-9210-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, L., & Zheng, Z. (2018). A desire for social media is associated with a desire for solitary but not social activities. Psychological Reports, 121(6), 1120–1130. 10.1177/0033294117742657 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hughes, M. E., Waite, L. J., Hawkley, L. C., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2004). A short scale for measuring loneliness in large surveys: Results from two population-based studies. Research on Aging, 26(6), 655–672. 10.1177/0164027504268574 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karapanos, E., Teixeira, P., & Gouveia, R. (2016). Need fulfillment and experiences on social media: A case on Facebook and WhatsApp. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 888–897. 10.1016/j.chb.2015.10.015 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kardefelt-Winther, D. (2014). A conceptual and methodological critique of Internet addiction research: Towards a model of compensatory Internet use. Computers in Human Behavior, 31(1), 351–354. 10.1016/j.chb.2013.10.059 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaye, L. K., & Quinn, S. (2020). Psychosocial outcomes associated with engagement with online chat systems. International Journal of Human-Computer Interaction, 36(2), 190–198. 10.1080/10447318.2019.1620524 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J., LaRose, R., & Peng, W. (2009). Loneliness as the cause and the effect of problematic Internet use: The relationship between Internet use and psychological well-being. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(4), 451–455. 10.1089/cpb.2008.0327 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kircaburun, K., Grifiths, M. D., Şahin, F., Bahtiyar, M., Atmaca, T., & Tosuntaş, Ş. B. (2020). The mediating role of self/everyday creativity and depression on the relationship between creative personality traits and problematic social media use among emerging adults. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 18, 77–88. 10.1007/s11469-018-9938-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koc, M., & Gulyagci, S. (2013). Facebook addiction among Turkish college students: The role of psychological health, demographic, and usage characteristics. Cyberpsychology, Behavior and Social Networking, 16(4), 279–284. 10.1089/cyber.2012.0249 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohútová, V., Špajdel, M., & Dědová, M. (2021). Emerging adulthood – An easy time of being? Meaning in life and satisfaction with life in the time of emerging adulthood. Studia Psychologica, 63(3), 307–321. 10.31577/SP.2021.03.829 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut, R., Patterson, M., Lundmark, V., Kiesler, S., Mukophadhyay, T., & Scherlis, W. (1998). Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well- being? American Psychologist, 53(9), 1017–1031. 10.1037/0003-066X.53.9.1017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larson, R. (1990). The solitary side of life: An examination of the time people spend alone from childhood to old age. Developmental Review, 10(2), 155–183. 10.1016/0273-2297(90)90008-R [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Laursen, B., & Hartl, A. C. (2013). Understanding loneliness during adolescence: Developmental changes that increase the risk of perceived social isolation. Journal of Adolescence, 36(6), 1261–1268. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2013.06.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Long, C. R., & Averill, J. R. (2003). Solitude: An exploration of benefits of being alone. Journal for the Theory of Social Behaviour, 33(1), 21–44. 10.1111/1468-5914.00204 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Long, C. R., Seburn, M., Averill, J. R., & More, T. A. (2003). Solitude experiences: Varieties, settings, and individual differences. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29(5), 578–583. 10.1177/0146167203029005003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes, M., Qualter, P., Lodder, G. M. A., & Mund, M. (2022). How (not) to measure loneliness: A review of the eight most commonly used scales. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(17), 10816. 10.3390/ijerph191710816 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Majorano, M., Musetti, A., Brondino, M., & Corsano, P. (2015). Loneliness, emotional autonomy and motivation for solitary behavior during adolescence. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(11), 3436–3447. 10.1007/s10826-015-0145-3 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Malaeb, D., Salameh, P., Barbar, S., Awad, E., Haddad, C., Hallit, R., Sacre, H., Akel, M., Obeid, S., & Hallit, S. (2021). Problematic social media use and mental health (depression, anxiety, and insomnia) among Lebanese adults: Any mediating effect of stress? Perspectives in Psychiatric Care, 57(2), 539–549. 10.1111/ppc.12576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-María, N., Caballero, F. F., Miret, M., Tyrovolas, S., Haro, J. M., Ayuso-Mateos, J. L., & Chatterji, S. (2020). Differential impact of transient and chronic loneliness on health status. A longitudinal study. Psychology & Health, 35(2), 177–195. 10.1080/08870446.2019.1632312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marttila, E., Koivula, A., & Räsänen, P. (2021). Does excessive social media use decrease subjective well-being? A longitudinal analysis of the relationship between problematic use, loneliness and life satisfaction. Telematics and Informatics, 59, 101556. 10.1016/j.tele.2020.101556 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Meerkerk, G. J., Van Den Eijnden, R. J., Vermulst, A. A., & Garretsen, H. F. (2009). The Compulsive Internet Use Scale (CIUS): Some psychometric properties. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 12(1), 1–6. 10.1089/cpb.2008.0181 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meshi, D., & Ellithorpe, M. (2021). Problematic social media use and social support received in real- life versus on social media: Associations with depression, anxiety and social isolation. Addictive Behaviors, 119, 106949. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.106949 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moretta, T., & Buodo, G. (2020). Problematic Internet use and loneliness: How complex is the relationship? A short literature review. Current Addiction Reports, 7(2), 125–136. 10.1007/s40429-020-00305-z [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Moretta, T., Franceschini, C., & Musetti, A. (2023). Loneliness and problematic social networking sites use in young adults with poor vs. good sleep quality: The moderating role of gender. Addictive Behaviors, 142, 107687. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2023.107687 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Musetti, A., Manari, T., Billieux, J., Starcevic, V., & Schimmenti, A. (2022). Problematic social networking sites use and attachment: A systematic review. Computers in Human Behavior, 131, 107199. 10.1016/j.chb.2022.107199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Musetti, A., Starcevic, V., Boursier, V., Corsano, P., Billieux, J., & Schimmenti, A. (2021). Childhood emotional abuse and problematic social networking sites use in a sample of Italian adolescents: The mediating role of deficiencies in self‐other differentiation and uncertain reflective functioning. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 77(7), 1666–1684. 10.1002/jclp.23138 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagar, K., Singh, G., & Singh, R. (2021). Mediating effect of WhatsApp addiction between social loneliness and preference for online social interaction: A cross-cultural study. Global Business Review. Advance online publication. 10.1177/09721509211055603 [DOI]

- National Institutes of Health (2017, November 12). Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-sectional Studies. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. V., Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2018). Solitude as an approach to affective self-regulation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 44(1), 92–106. 10.1177/0146167217733073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen, T. V., Werner, K. M., & Soenens, B. (2019). Embracing me-time: Motivation for solitude during transition to college. Motivation and Emotion, 43(4), 571–591. 10.1007/s11031-019-09759-9 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson, N. (2009). Social isolation in older adults: An evolutionary concept analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 65, 1342–1352. 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04959.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nowland, R., Necka, E. A., & Cacioppo, J. T. (2018). Loneliness and social Internet use: Pathways to reconnection in a digital world? Perspectives on Psychological Science, 13(1), 70–87. 10.1177/1745691617713052 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Day, E. B., & Heimberg, R. G. (2021). Social media use, social anxiety, and loneliness: A systematic review. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 3, 100070. 10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100070 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ost Mor, S., Palgi, Y., & Segel-Karpas, D. (2021). The definition and categories of positive solitude: Older and younger adults’ perspectives on spending time by themselves. International Journal of Aging & Human Development, 93(4), 943–962. 10.1177/0091415020957379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … McKenzie, J. E. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372, n160. 10.1136/bmj.n160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman, D., & Peplau, L. (1998). Loneliness. In Friedman, H. S. (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Mental Health, Vol. 2 (pp. 571–581). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Petrosyan, A. (2024, August 19). Number of Internet and social media users worldwide as of July 2024. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/617136/digital-population-worldwide

- Piko, B., Kiss, H., Ratky, D., & Fitzpatrick, K. (2022). Relationships among depression, online self- disclosure, social media addiction, and other psychological variables among Hungarian university students. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 210(11), 818–823. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000001563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponnusamy, S., Iranmanesh, M., Foroughi, B., & Hyun, S. (2020). Drivers and outcomes of Instagram addiction: Psychological well-being as moderator. Computers in Human Behavior, 107, 106294. 10.1016/j.chb.2020.106294 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Primack, B. A., Shensa, A., Sidani, J. E., Whaite, E. O., Lin, L. Y., Rosen, D., Colditz, J. B., Radovic, A., & Miller, E. (2017). Social media use and perceived social isolation among young adults in the U.S. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 53(1), 1–8. 10.1016/j.amepre.2017.01.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajesh, T., & Rangaiah, B. (2020). Facebook addiction and personality. Heliyon, 6(1), e03184. 10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e03184 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, K. H., & Coplan, R. J. (2004). Paying attention to and not neglecting social withdrawal and social isolation. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 50(4), 506–534. 10.1353/mpq.2004.0036 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Ferguson, M. L. (1978). Developing a measure of loneliness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 42(3), 290–294. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4203_11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, D., Peplau, L. A., & Cutrona, C. E. (1980). The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: Concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39(3), 472–480. 10.1037//0022-3514.39.3.472 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell, D. (1996). UCLA Loneliness Scale (version 3): Reliability, validity, and factor structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 66(1), 20–40. 10.1207/s15327752jpa6601_2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russo, A., Santoro, G., & Schimmenti, A. (2022). Interpersonal guilt and problematic online behaviors: The mediating role of emotion dysregulation. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 19(4), 236. 10.36131/cnfioritieditore20220406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan, T., Allen, K. A., Gray, D. L. L., & McInerney, D. M. (2017). How social are social media? A review of online social behaviour and connectedness. Journal of Relationships Research, 8(e8), 1–8. 10.1017/jrr.2017.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Samra, A., Warburton, W. A., & Collins, A. M. (2022). Social comparisons: A potential mechanism linking problematic social media use with depression. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 11(2), 607–614. 10.1556/2006.2022.00023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savci, M., & Aysan, F. (2017). Technological addictions and social connectedness: Predictor effect of Internet addiction, social media addiction, digital game addiction and smartphone addiction on social connectedness. Dusunen Adam - The Journal of Psychiatry and Neurological Sciences, 30(3), 202–216. 10.5350/dajpn2017300304 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schimmenti, A. (2023). Beyond addiction: Rethinking problematic Internet use from a motivational framework. Clinical Neuropsychiatry, 20(6), 471–478. 10.36131/cnfioritieditore20230601 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, N., & Sermat, V. (1983). Measuring loneliness in different relationships. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 44(5), 1038–1047. 10.1037/0022-3514.44.5.1038 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shannon, H., Bush, K., Villeneuve, P. J., Hellemans, K. G. C., & Guimond, S. (2022). Problematic social media use in adolescents and young adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Mental Health, 9(4), e33450. 10.2196/33450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shensa, A., Escobar-Viera, C. G., Sidani, J. E., Bowman, N. D., Marshal, M. P., & Primack, B. A. (2017). Problematic social media use and depressive symptoms among U.S. young adults: A nationally-representative study. Social Science and Medicine, 182, 150–157. 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, V., & Azmitia, M. (2019). Motivation matters: Development and validation of the Motivation for Solitude Scale – Short Form (MSS-SF). Journal of Adolescence, 70, 33–42. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas, V. (2021). Solitude skills and the private self. Qualitative Psychology, 10(1), 121. 10.1037/qup0000218 [DOI] [Google Scholar]