Abstract

Anthemis L. 1753 is a species-rich genus of Asteraceae. It includes species of economic value as ornamental, edible and medicinal plants. We report here the complete chloroplast genome of Anthemis cretica subsp. calabrica (Arcang.) R. Fern. 1975, the first chloroplast genome of any Anthemis species. For the scope, we have used long reads obtained with Oxford Nanopore technology. The assembled plastome is 149,509 bp long and is subdivided in a large single-copy region (LSC, 82,317 bp), a small single-copy region (SSC, 18,212 bp) and two inverted repeat regions (IR: 24,490 bp). It comprehends 136 predicted genes, of which 92 protein-coding genes, 35 tRNAs, and 8 rRNAs. The overall GC content is 37.54%. The position of A. cretica subsp. calabrica in the phylogenetic tree is congruent with those of previous analyses based on a few chloroplast or nuclear regions.

Keywords: Anthemis, Anthemis cretica, Asteraceae, chloroplast genome

Introduction

Anthemis L. 1753 is a species-rich genus of the Sunflower family (Asteraceae), including about 175 species, mainly distributed in the Mediterranean region, Europe, south-western Asia and eastern Africa (Anderberg et al. 2007). Different species of the genus are used as ornamental (e.g. A. arvensis L., A. cupaniana Nyman), for producing tea and/or as medicinal plant (Facciola 1998; Chevallier 2001). The genus gives the name to tribe Anthemideae Cass. 1819.

The Cretan mat daisy (Anthemis cretica L. 1753) is a species complex comprehending perennial plants and several subspecies growing mostly in mountain environments of the Mediterranean region, Middle East and Caucasus. It is highly morphologically variable, and includes several polyploids (Franzen 1986). Despite its diversity, taxonomical importance, and economic value as ornamental and edible plant, no chloroplast genome is publically available for any Anthemis species.

In the present study, we report the chloroplast genome sequence of an Anthemis species. We aimed at providing insights into the genome characterization through a comprehensive analysis. Information on the chloroplast genome of A. cretica will be a useful tool for future taxonomic and evolutionary studies focused on the genus and on the whole subtribe.

Materials and methods

Plant material and DNA extraction

Anthemis cretica subsp. calabrica (Arcang.) R. Fern. 1975 was collected close to Buturo (Calabria, Italy; 39.0535 N, 16.66188 E; Figure 1). A few leaves were silica-gel dried for DNA extraction and sequencing. A number of individuals were hebarized and stored in the Herbarium of the University of Göttingen (https://www.uni-goettingen.de/de/157034.html; contact person: Dr. Marc Appelhans, marc.appelhans@biologie.uni-goettingen.de) under the voucher number GOET065146.

Figure 1.

Anthemis cretica subsp. calabrica. (a) Plant individual at ‘vallata dell’Amendolea’ (southwest from ‘Diga del Menta’, Calabria; Italy) with the typical cespitose habitus, and solitary capitula with white ray and yellow disk florets (photo: Franz Xaver – wikimedia commons – CC by-SA 3.0). (b) Plant rosette collected at Buturo (Calabria; Italy) with the typical (bi-)pinnatisect leaves covered by silvery tomentum, and dried flower heads (photo: Salvatore Tomasello).

Genomic DNA was extracted from ca.1.5 cm2 leaf material of silica-dried sample using the Qiagen DNeasy Plant Mini Kit® (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). We followed the manufacturer’s instructions, except for the incubation times in the lysis and elution buffers, which were both increased to 30 min. DNA quality and fragment length were checked by gel electrophoresis in a 1.5% agarose gel. DNA concentration was estimated using 2 µl of extract and the Qubit® fluorometer with the Qubit® dsDNA HS Assay Kit (ThermoFisher Scientific, Waltham, USA).

Library preparation

The library was prepared with the ONT Ligation Sequencing Kit SQK-LSK110 optimized for high throughput and long reads (ONT, Oxford, UK) and applicable for single-plex gDNA sequencing. We adjusted the DNA concentration to 1.000 ng in 47 µl (ca. 21.5 ng/µl). We followed the manufacturer’s instructions for library preparation (protocol v. GDE_9141_v112_revH_01Dec2021, accessible via community.nanoporetech.com) with few modifications as in Karbstein et al. (2023). The library was loaded into a R9.4.1 flow cells following the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing was performed for 72 h.

Assembly and annotation

Base-calling was done on the local HPC cluster of the University of Gottingen. (GWDG, Göttingen, Germany), using the ONT software GUPPY v. 6.0.1 and the configuration file ‘dna_r9.4.1_450bps_hac.cfg’ for high accuracy base-calling. We performed plastome assembly with ptGAUL (Zhou et al. 2023). We used the plastome of Tanacetum cinerariifolium (Trevir.) Sch.Bip. 1844 (MT104464) as reference and the default settings, apart from the minimum length of reads that was set to 500, and the coverage (-c), which was set to 190.

The plastome was annotated using the online tool GeSeq (Tillich et al. 2017) (available at https://chlorobox. mpimp-golm.mpg.de/geseq.html). The BLAT (Kent 2002) searches were done setting the protein search identity to 80% and the rRNA, tRNA and DNA search identity to 85%. As reference, we used the T. cinerariifolium plastome (MT104464). Additionally, the MPI-MP land plant references were used for chloroplast CDS and rRNAs. The obtained annotation was checked manually in Geneious Prime 2022.1.1 (https://www.geneious.com). Since Nanopore assemblies are well-known for missing bases in homonucleotide regions (Scheunert et al. 2020), we checked the annotation for cases in which such missing nucleotides changed the reading frame and produced anticipated termination of coding regions. In such cases, the missing nucleotides were added, and the sequence corrected.

The final annotated chloroplast genomes were converted into graphical maps using the OGDRAW (Greiner et al. 2019) with default settings.

Phylogeny

Twenty-nine chloroplast genomes of taxa belonging to different subtribes of tribe Anthemideae, along with two outgroup accessions, were downloaded from GenBank and aligned with the plastome of Anthemis cretica (Table 1). In some cases, the orientation of the Small Single Copy region (SSC) was inverted in order to make it match to the other accessions. The sequences were processed in AliView v. 1.20 (Larsson 2014) and aligned with MAFFT v. 7.305b (Katoh and Standley 2013). The final alignment consisted of 163,110 characters. A Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree was inferred with RAXML-NG v. 1.2.0 (Kozlov et al. 2019), using the GTR + G as sequence evolution model and applying 100 bootstrap (bs) replicates.

Table 1.

Detailed information and GenBank accession numbers of the samples used for the phylogenetic analysis in Figure 3.

| Taxon | GenBank | Subtribe | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Achillea millefolium | ON320384.1 | Matricariinae | Liu et al. (2023) |

| Ajania pacifica | MN883841.1 | Artemisiinae | Kim and Kim (2020a) |

| Allardia glabra | MW628520.1 | Handeliinae | Hai et al. (2021) |

| Anacyclus radiatus | SRR9822607* | Matricariinae | Pascual-Díaz et al. (2021) |

| Artemisia frigida | NC_20607.1 | Artemisiinae | Liu et al. (2013) |

| Artemisia fukudo | MK569048.1 | Artemisiinae | Min et al. (2019) |

| Artemisia scoparia | MT830857.1 | Artemisiinae | Li et al. (2020) |

| Artemisia selengensis | NC_39647.1 | Artemisiinae | Peng et al. (2018) |

| Chrysanthemum boreale | MG913594.1 | Artemisiinae | Won et al. (2018) |

| Chrysanthemum indicum | MW633069.1 | Artemisiinae | |

| Crossostephium chinense | MH708560.1 | Artemisiinae | Chen et al. (2019) |

| Glebionis coronaria | MW874476.1 | Glebionidinae | Li et al. (2021) |

| Ismelia carinata | MG710387.1 | Glebionidinae | Liu et al. (2018) |

| Leucanthemella linearis | MN883842.1 | Artemisiinae | Kim and Kim (2020b) |

| Leucanthemum virgatum | MN996243.1 | Leucantheminae | Scheunert et al. (2020) |

| Leucanthemum vulgare | MN989913.1 | Leucantheminae | Scheunert et al. (2020) |

| Neopallasia pectinata | MW007388.1 | Artemisiinae | Yu et al. (2021) |

| Opisthopappus taihangensis | MK552323.1 | Artemisiinae | Gu et al. (2019) |

| Phaeostigma variifolium | MG873554.1 | Artemisiinae | Ma et al. (2020) |

| Santolina chamaecyparissus | NC_66020.1 | Santolininae | |

| Soliva sessilis | NC_34851.1 | Cotulinae | Vargas et al. (2017) |

| Stilpnolepis centiflora | MT830619.1 | Artemisiinae | Shi and Xie (2020) |

| Tanacetum cinerariifolium | MT104464.1 | Anthemidinae | |

| Tanacetum coccineum | MT104463.1 | Anthemidinae | |

| Aster tataricus | NC_42913.1 | Shen et al. (2018) | |

| Conyza bonariensis | MF276802.1 | Hereward et al. (2017) |

The plastomes of Aster tataricus L.f.1785 and Conyza bonariensis (L.) cronquist 1943 (erigeron bonariensis L. 1753), not members of tribe Anthemideae, were used as outgroup.

*Data of Anacyclus radiatus (SRR9822607; Pascual-Díaz et al. 2021) consisted of raw reads. We have used them to assemble the plastome of A. radiatus, mapping the reads provided by Pascual-Díaz et al. (2021) against the plastome of Achillea millefolium (ON320384) with bwa v. 0.7.16 (Li and Durbin 2009) and then producing a consensus sequence with ConsensusFixer v.0.4 (available at: https://github.com/cbg-ethz/consensusfixer).

Results

Sequencing and assembly

Sequencing produced 17.21 Gb of *fast5 files (118 files). In total, 470.3 thousand reads were generated after base-calling, with a mean read fragment length of 2,030 bp. The longest read was 81,171 bp and the overall data produced amounted to 0.52 Gbp. ptGAUL obtained a circular plastid genome of 149,460 bp in two different states (orientations of the Small Single Copy (SSC) region). After homonucleotide region correction, the plastome sequence was 149,509 bp long. Read mapping shows that all genomic regions of the plastome were well covered by reads, suggesting high accuracy of the genome assembly (Supplementary Figure S1). The complete chloroplast genome of A. cretica subsp. calabrica is available on the GenBank with accession number PP626368.

The plastome shows a typical tripartite structure with a small single-copy region (SSC, length: 18,212 bp) and a large single-copy region (LSC, length: 82,317 bp), separated by two IR regions (length: 2 × 24,490 bp; Figure 2). It has a GC content of 37.54% and contains 92 (80 unique) protein-coding genes, 35 (29 unique) tRNAs, and 8 (4 unique) rRNAs (Supplementary Figures S2 and S3).

Figure 2.

The complete chloroplast genome map of Anthemis cretica subsp. calabrica. The color of genes indicates their affiliation to the functional groups. The first inner circle depicts the genome structure with the small single-copy region (SSC), the large single-copy region (LSC) and the two inverted repeats (IRa/b). The innermost grey shaded circle represents the GC content (%). genes on the inside of the map are transcribed in the clockwise, whereas genes on the outside counter-clockwise.

Phylogeny

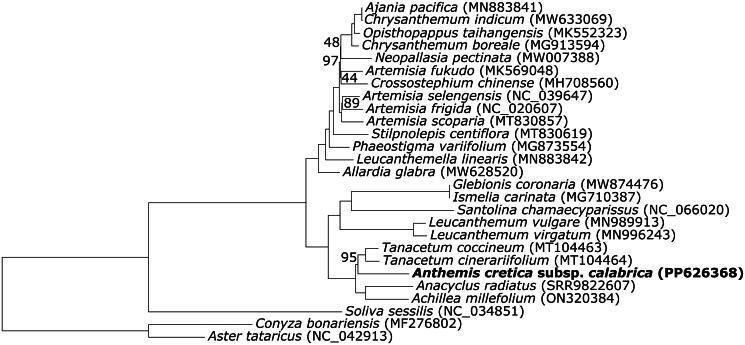

The ML tree is well resolved and show overall high bootstrap values (Figure 3). Anthemis cretica is found in a clade (bs: 97) together with species of Tanacetum L. 1753, the only other representatives of subtribe Anthemidinae (Cass.) Dumort 1827 in the dataset. This clade is found to be sister to subtribe Matricariinae K.Bremer & Humphries 1993 (bs:100). Within subtribe Artemisiinae Less. 1830, samples belonging to the ‘Chrysanthemum group’ (i.e. Chrysanthemum boreale Makino 1909, C. indicum L. 1753, Ajania pacifica (Nakai) K.Bremer & Humphries 1993, Opisthopappus taihangensis (Ling) C.Shih 1979) form a highly supported clade (bs: 100).

Figure 3.

Maximum Likelihood (ML) phylogenetic tree based on complete chloroplast genomes, and including A. cretica subsp. calabrica along with 29 additional accessions belonging to tribe Anthemideae: Achillea millefolium (ON320384; Liu et al. 2023); Ajania pacifica (MN883841; Kim and Kim 2020a); Allardia glabra (MW628520; Hai et al. 2021); Anacyclus radiatus (SRR9822607; Pascual-Díaz et al. 2021); Artemisia frigida (NC_20607; Liu et al. 2013); Artemisia fukudo (MK569048; Min et al. 2019); Artemisia scoparia (MT830857; Li et al. 2020); Artemisia selengensis (NC_39647; Peng et al. 2018); Chrysanthemum boreale (MG913594; Won et al. 2018); Chrysanthemum indicum (MW633069); Crossostephium chinense (MH708560; Chen et al. 2019); Glebionis coronaria (MW874476; Li et al. 2021); Ismelia carinata (MG710387; Liu et al. 2018); Leucanthemella linearis (MN883842; Kim and Kim 2020b); Leucanthemum virgatum (MN996243; Scheunert et al. 2020); L. vulgare (MN989913; Scheunert et al. 2020); Neopallasia pectinata (MW007388; Yu et al. 2021); Opisthopappus taihangensis (MK552323; Gu et al. 2019); Phaeostigma variifolium (MG873554; Ma et al. 2020); Santolina chamaecyparissus (NC_66020); Soliva sessilis (NC_34851; Vargas et al. 2017); Stilpnolepis centiflora (MT830619; Shi and Xie 2020); Tanacetum cinerariifolium (MT104464); T. coccineum (MT104463). In addition, the following accessions were included and used as outgroup: Aster tataricus (NC_42913; Shen et al. 2018); Conyza bonariensis (MF276802; Hereward et al. 2017). Bootstrap support values, when lower than 100, are shown beside nodes.

Discussion and conclusions

In this study, we report the chloroplast genome sequence of A. cretica subsp. calabrica, the first complete chloroplast genome of any Anthemis species. This plastome will be a useful tool for phylogenetic, taxonomic and evolutionary studies focused on the genus. It could serve as reference for reference-based assembly of chloroplast genomes in the genus Anthemis, and in the whole subtribe Anthemidinae.

The overall topology of the phylogenetic tree shown in Figure 3 is congruent with those inferred in previous studies (Oberprieler et al. 2009, 2022; Tomasello et al. 2015). Anthemis is nested within the Anthemidinae, which are found to be sister of subtribe Matricariinae, as in Tomasello et al. (2015). However, a more exhaustive sampling may result in the rejection of the reciprocal monophyly of these two subtribes (Oberprieler et al. 2009, 2022). Within subtribe Artemisiinae, Artemisia L.1753 is found to be paraphyletic, with Crossostephium Less 1831 nested within it (Watson et al. 2002). Ajania pacifica (Dendranthema pacificum (Nakai) Kitam. 1978) is found together with Chrysanthemum indicum (the Ch. indicum-complex; Shen et al. 2021).

Supplementary Material

Funding Statement

The author(s) reported there is no funding associated with the work featured in this article.

Author contributions

S.T. conceived and designed the study. E.M. and S.T. analyzed the data. E.M. and S.T. wrote the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript and agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Ethical approval

This work does not require Ethical approval or specific permissions.

Data availability statement

The assembled chloroplast genome is freely available in the GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under the accession number of PP626368.1. Information on the used plant material is available under the Bio-sample accession number SAMEA115545247. The raw sequencing data have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA), with Bio-Project accession number PRJEB75492 and SRA accession number ERR13034843.

References

- Anderberg AA, Baldwin BG, Bayer RG, Breitwieser J, Jeffrey C, Dillon MO, Eldenäs P, et al. 2007. Compositae. In: Kubitzki K, editor. The families and genera of vascular plants. VIII. Flowering plants, Eudicots: Asterales. Berlin: Springer; p. 61–576. [Google Scholar]

- Chen T, Du Y, Zhao H, Dong M, Liu L.. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome of Crossostephium chinense (Asteraceae), using genome skimming data. Mitochondrial DNA Part B Resour. 4(1):322–323. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2018.1544038. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chevallier A. 2001. Encyclopedia of medicinal plants. London: Dorling Kindersley. [Google Scholar]

- Facciola S. 1998. Cornucopia II: a source book of edible plants. New York (NY): Kampong Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Franzen R. 1986. Anthemis cretica (Asteraceae) and related species in Greece. Willdenowia. 16:35–45. [Google Scholar]

- Greiner S, Lehwark P, Bock R.. 2019. OrganellarGenomeDRAW (OGDRAW) version 1.3.1: expanded toolkit for the graphical visualization of organellar genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 47(W1):W59–W64. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gu J, Wei Z, Yue C, Xu X, Zhang T, Zhao Q, Fu S, Yang D, Zhu S.. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome of Opisthopappus taihangensis (Ling) Shih. Mitochondrial DNA Part B Resour. 4(1):1415–1416.,. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1598791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hai W, Wang W, Tong L, Shao-Hu N, Li W, Lu Y-Z, Tong B-Q, Hui-En Z.. 2021. The complete chloroplast genome of Waldheimia glabra. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 6(8):2221–2223.,. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2021.1944372. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hereward JP, Werth JA, Thornby DF, Keenan M, Chauhan BS, Walter GH.. 2017. Complete chloroplast genome of glyphosate resistant Conyza bonariensis (L.) Cronquist from Australia. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 2(2):444–445. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2017.1357441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karbstein K, Tomasello S, Wagner N, Barke BH, Paetzold C, Bradican JP, Preick M, et al. 2023. Efficient hybrid strategies for assembling the plastome, mitochondriome, and large nuclear genome of diploid Ranunculus cassubicifolius (Ranunculaceae). bioRxiv 2023.08.08.552429. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh K, Standley DM.. 2013. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Mol Biol Evol. 30(4):772–780. doi: 10.1093/molbev/mst010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent WJ. 2002. BLAT - The BLAST-like alignment tool. Genome Res. 12(4):656–664. doi: 10.1101/gr.229202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HT, Kim JS.. 2020a. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Ajania pacifica (Nakai) Bremer & Humphries. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 5(3):2399–2400. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2020.1750981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HT, Kim JS.. 2020b. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Leucanthemella linearis (Matsum. ex Matsum.) Tzvelev (Asteraceae), endangered plant of Korea. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 5(3):3360–3362. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2020.1821819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kozlov AM, Darriba D, Flouri T, Morel B, Stamatakis A.. 2019. RAxML-NG: a fast, scalable and user-friendly tool for maximum likelihood phylogenetic inference. Bioinformatics. 35(21):4453–4455. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btz305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsson A. 2014. AliView: a fast and lightweight alignment viewer and editor for large datasets. Bioinformatics. 30(22):3276–3278. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Durbin R.. 2009. Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows-Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics. 25(14):1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J, Jiang M, Chen H, Yu J, Liu C.. 2020. Intraspecific variations among the chloroplast genomes of Artemisia scoparia (Asteraceae) from Pakistan and China. Mitochondrial DNA Part B Resour. 5(3):3182–3184. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2020.1810167. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li W, Jiang S, Wang J, Yu Y, Zhu Z.. 2021. Complete chloroplast genome and phylogenetic analysis of Glebionis coronaria (L.) Cass. ex Spach (Asteraceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 6(9):2693–2694. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2021.1966331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu F, Movahedi A, Yang W, Xu D, Jiang C.. 2023. The complete plastid genome and characteristics analysis of Achillea millefolium. Funct Integr Genomics. 23(2):192. doi: 10.1007/s10142-023-01121-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu X, Zhou B, Yang H, Li Y, Yang Q, Lu Y, Gao Y.. 2018. Sequencing and analysis of Chrysanthemum carinatum Schousb and Kalimeris indica. The complete chloroplast genomes reveal two inversions and rbcL as barcoding of the vegetable. Molecules. 23(6):1358. doi: 10.3390/molecules23061358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Y, Huo N, Dong L, Wang Y, Zhang S, Young HA, Feng X, Gu YQ.. 2013. Complete chloroplast genome sequences of Mongolia medicine Artemisia frigida and phylogenetic relationships with other plants. PLoS One. 8(2):e57533.,. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0057533. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y, Zhao L, Zhang W, Zhang Y, Xing X, Duan X, Hu J, Harris AJ, Liu P, Dai S, et al. 2020. Origins of cultivars of Chrysanthemum—Evidence from the chloroplast genome and nuclear LFY gene. J Sytematics Evol. 58(6):925–944. doi: 10.1111/jse.12682. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Min J, Park J, Kim Y, Kwon W.. 2019. The complete chloroplast genome of Artemisia fukudo Makino (Asteraceae): providing insight of intraspecies variations. Mitochondrial DNA Part B Resour. 4(1):1510–1512. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2019.1601044. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oberprieler C, Himmelreich S, Källersjö M, Vallès J, Watson LE, Vogt R.. 2009. Anthemideae. In: Funk VA, Susanna A, Stuessy TF, and Bayer RJ, editors. Systematics, evolution, and biogeography of compositae. Vienna: IAPT, p. 689–711. [Google Scholar]

- Oberprieler C, Töpfer A, Dorfner M, Stock M, Vogt R.. 2022. An updated subtribal classification of Compositae tribe Anthemideae based on extended phylogenetic reconstructions. Willdenowia. 52(1):117–149. doi: 10.3372/wi.52.52108. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Díaz JP, Garcia S, Vitales D.. 2021. Plastome diversity and phylogenomic relationships in Asteraceae. Plants (Basel). 10(12):2699. doi: 10.3390/plants10122699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng J, Zhao Y, Li C, Xu Z.. 2018. The complete chloroplast genome and phylogeny of Artemisia selengensis in Dongting Lake. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 3(2):907–908. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2018.1501322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scheunert A, Dorfner M, Lingl T, Oberprieler C.. 2020. Can we use it? On the utility of de novo and reference-based assembly of nanopore data for plant plastome sequencing. PLoS ONE. 15(3):e0232195. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0226234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen CZ, Zhang CJ, Chen J, Guo YP.. 2021. Clarifying recent adaptive diversification of the Chrysanthemum-group on the basis of an updated multilocus phylogeny of subtribe Artemisiinae (Asteraceae: Anthemideae). Front Plant Sci. 12:648026. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2021.648026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Guo S, Yin Y, Zhang J, Yin X, Liang C, Wang Z, Huang B, Liu Y, Xiao S, et al. 2018. Complete chloroplast genome sequence and phylogenetic analysis of Aster tataricus. Molecules. 23(10):2426. doi: 10.3390/molecules23102426. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X, Xie K.. 2020. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Stilpnolepis centiflora (Asteraceae), an endemic desert species in Northern China. Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 5(3):3545–3546. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2020.1829127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillich M, Lehwark P, Pellizzer T, Ulbricht-Jones ES, Fischer A, Bock R, Greiner S.. 2017. GeSeq - Versatile and accurate annotation of organelle genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45(W1):W6–W11. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tomasello S, Álvarez I, Vargas P, Oberprieler C.. 2015. Is the extremely rare Iberian endemic plant species Castrilanthemum debeauxii (Compositae, Anthemideae) a ‘living fossil’? Evidence from a multi-locus species tree reconstruction. Mol Phylogenet Evol. 82:118–130. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vargas OM, Ortiz EM, Simpson BB.. 2017. Conflicting phylogenomic signals reveal a pattern of reticulate evolution in a recent high-Andean diversification (Asteraceae: astereae: diplostephium). New Phytol. 214(4):1736–1750. doi: 10.1111/nph.14530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Watson LE, Bates PL, Evans TM, Unwin MM, Estes JR.. 2002. Molecular phylogeny of Subtribe Artemisiinae (Asteraceae), including Artemisia and its allied and segregate genera. BMC Evol Biol. 2(1):17. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-2-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Won SY, Jung JA, Kim JS.. 2018. The complete chloroplast genome of Chrysanthemum boreale (Asteraceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 3(2):549–550. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2018.1468225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Xia M, Xu H, Han S, Zhang F.. 2021. The complete chloroplast genome sequence of Neopallasia pectinata (Asteraceae). Mitochondrial DNA B Resour. 6(2):430–431. doi: 10.1080/23802359.2020.1870893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou W, Armijos CE, Lee C, Lu R, Wang J, Ruhlman TA, Jansen RK, Jones AM, Jones CD.. 2023. Plastid genome assembly using long-read data. Mol Ecol Resour. 23(6):1442–1457. doi: 10.1111/1755-0998.13787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The assembled chloroplast genome is freely available in the GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/) under the accession number of PP626368.1. Information on the used plant material is available under the Bio-sample accession number SAMEA115545247. The raw sequencing data have been deposited in the European Nucleotide Archive (ENA), with Bio-Project accession number PRJEB75492 and SRA accession number ERR13034843.