Abstract

The unique ability of adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV) to site-specifically integrate its genome into a defined sequence on human chromosome 19 (AAVS1) makes it of particular interest for use in targeted gene delivery. The objective underlying this study is to provide evidence for the feasibility of retargeting site-specific integration into selected loci within the human genome. Current models postulate that AAV DNA integration is initiated through the interactions of the products of a single viral open reading frame, REP, with sequences present in AAVS1 that resemble the minimal origin for AAV DNA replication. Here, we present a cell-free system designed to dissect the Rep functions required to target site-specific integration using functional chimeric Rep proteins derived from AAV Rep78 and Rep1 of the closely related goose parvovirus. We show that amino-terminal domain exchange efficiently redirects the specificity of Rep to the minimal origin of DNA replication. Furthermore, we establish that the amino-terminal 208 amino acids of Rep78/68 constitute a catalytic domain of Rep sufficient to mediate site-specific endonuclease activity.

Adeno-associated virus type 2 (AAV) has drawn much attention as a potential vector for human gene therapy. Advantages include its apparent lack of pathogenicity, its capacity to infect many cell types, and, notably, the ability of the wild-type (wt) virus to site-specifically integrate into a region on chromosome 19 known as AAVS1 (19q13.4) (14, 26–28, 35–37, 47). Integration, and thus the establishment of latency, is thought to occur preferentially over productive replication in the absence of coinfection of the host cell by a helper virus (3, 4, 8, 18).

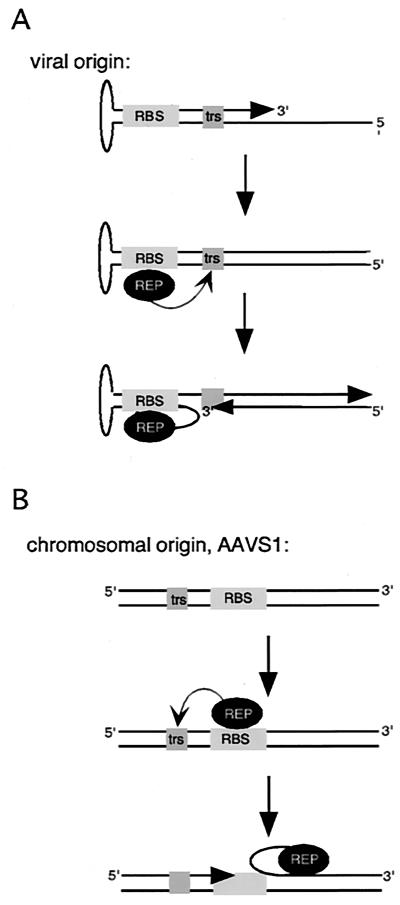

The AAV genome is linear, single stranded, and flanked on either side by inverted terminal repeats (ITRs) (45, 53). Palindromic sequences within the ITRs allow for the formation of hairpin secondary structures, which contain the viral origins of replication (5, 15, 17, 34, 38, 53). The minimal AAV DNA replication origin (AAVori) is organized into three segments: the Rep binding site (RBS), the terminal resolution site (TRS), and a spacer region separating the RBS from the TRS (Fig. 1A and 2B). The RBS coordinates the sequence-dependent recruitment of Rep to the origin (11), where it can then deliver a strand-specific nick at the TRS (23, 24). The spacer region has been implicated in favorably positioning the TRS so that it is efficiently nicked by the Rep protein (6). Interestingly, within AAVS1 is a region homologous to the minimal AAV origin in that it also contains a TRS and an RBS. Rep interaction with the minimal origin sequence in AAVS1 (57, 62) is required for site-specific integration (36, 63), thereby suggesting that Rep-mediated DNA replication may be linked to site-specific integration (Fig. 1B).

FIG. 1.

Schematic representation of the Rep-specific origins within the viral ITR (A) and in AAVS1 (B). See text for a more detailed discussion.

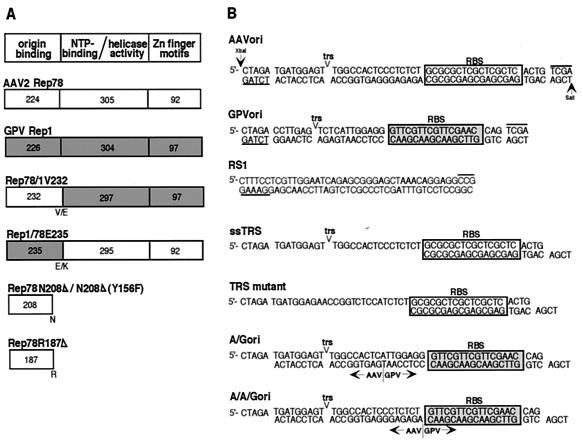

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of protein constructs and substrates used in this study. (A) Parental, chimeric, and truncated Rep proteins. Shaded areas correspond to regions derived from GPV Rep1. Numbers indicate the number of amino acids within each domain; letters indicate the amino acid at a junction or truncation. Putative functions of conserved domains are also noted. (B) Synthetic oligonucleotide substrates used in this study. The TRS and RBS are indicated. Overlined and underlined sequences are those that are added by Klenow polymerase for either incorporation of radioactive nucleotides or blunt end ligations. RS1 is an unrelated sequence used as a control substrate. Sequences of the chimeric origins were derived from AAV and GPV sequences as indicated.

Mechanistically, the initial steps of both AAV DNA replication and AAV site-specific integration are thought to be similar (25, 36). In this model, Rep78/68 initiates replication at the viral origin by nicking the TRS in a site- and strand-specific manner, generating a 3′ primer for replication. This event is followed by unidirectional replication and displacement of the nicked strand (Fig. 1A) (2). During the process of integration, it is presumed that the chromosomal origin sequence within AAVS1 is also targeted and nicked by means of interactions between Rep-RBS and TRS (37, 57, 67). A prerequisite for the establishment of integration is that limited DNA replication must be possible, once a primer is generated, despite the absence of helper virus functions. This assumption is supported by the results of cell-free DNA replication assays which use recombinant Rep and extracts from cells which are not infected by helper virus (42, 59, 61). Under these conditions, Rep-directed DNA replication is not processive (59, 60). This lack of processivity may result in template strand switches of the replication machinery, potentially generating the cellular-viral DNA junctions observed at sites of AAV integration (25, 36).

Collectively, these observations have made it apparent that Rep is responsible for the specificity of the AAV DNA integration event. Therefore, alteration of the Rep domain(s) responsible for its origin specificity could allow for the possibility of retargeting integration to different genomic loci. However, in order to establish retargeted integration, the functional domains responsible and sufficient for Rep's interaction with the minimal AAV DNA replication origin must be determined.

Of the four REP gene products (Rep78, -68, -52, and -40), Rep78 and -68 are best studied. It has been demonstrated that they are required for virtually every step of the viral life cycle, including DNA replication (20, 55), site-specific integration (1, 37, 54), rescue of integrated genomes, and regulation of both viral and cellular promoters (19, 21, 22, 30–33, 39, 44). Biochemical activities consistent with mediating origin-dependent replication have been characterized: specific binding to RBS-containing substrates (10, 24, 40, 41, 46, 62), nucleoside triphosphate-dependent DNA and DNA-RNA helicase activities (23, 24, 29, 50, 51, 58, 64, 65) and site-specific endonuclease activity at the TRS (23, 24).

Mutational analyses have revealed possible domain boundaries suggesting a separation of the multiple Rep activities (Fig. 2A). With respect to Rep's origin binding capability, studies demonstrating that Rep40 and Rep52, which lack the N terminus of Rep78/68, do not bind the AAV origin, provided the first suggestion that origin binding activity may be associated with this region (24). Furthermore, McCarty et al. (39) have proposed that amino acids 134 to 242 and 415 to 490 are required for specific binding to ITR substrates. In addition to these regions, residues 25 to 62, 88 to 113, and 346 to 400 have also been implicated in specific ITR binding (66). Extending these studies, Urabe et al. (56) undertook charged-to-alanine scanning mutagenesis of the Rep78 amino terminus, the results of which indicated the involvement of the N terminus in ITR binding, endonuclease activity, and thus the ability of these mutants to support integration. That the amino terminus itself may be sufficient for site-specific nicking activity has been recently demonstrated by Davis et al. (13), who earlier implicated tyrosine 156 in endonuclease activity (12). Smith and Kotin subsequently further implicated this tyrosine residue in both endonuclease and ligase activities (49). These studies are in direct contradiction to a study by Gavin et al. (16), who implicated aspartate 412, and thus the carboxy terminus of the protein, in mediating the nicking event.

Although mutational analyses have contributed much to our understanding of Rep function, definite domain boundaries have yet to be established. This is largely because loss of function due to a specific mutation could be attributed either to the replacement of a critical amino acid or, more generically, to the overall misfolding of a protein domain. To overcome this problem, we have chosen to approach domain mapping by generating functionally active AAV/goose parvovirus (GPV) chimeric Rep proteins. GPV is an autonomous parvovirus but nevertheless encodes a regulatory protein, Rep1, which is highly homologous in both sequence and biochemical activity to AAV Rep78 (Fig. 2A) (48, 68). Both proteins have specific DNA binding affinities for their respective origin substrates, helicase activity which maps to the central region of the protein, and C-terminal Zn finger motifs. Furthermore, the GPV origin, specifically recognized by Rep1, is organized similarly to the minimal AAV origin, in that it consists of a putative TRS and an RBS separated by a spacer region (Fig. 2B) (48, 68). Despite this high degree of similarity, GPV Rep1 is capable of mediating helper-independent replication within its host organism, in contrast to AAV Rep78 (7).

Functional chimeric Rep mutants were generated through N-terminal domain swapping based on the homologies between AAV Rep78 and GPV Rep1 (Fig. 2A). In one case, amino-terminal domain swapping between AAV Rep78 and the corresponding domain of GPV Rep1 resulted in a chimeric protein with biochemical activities comparable to those of the wild-type proteins. Intriguingly, the origin-specific interactions of this chimeric protein were determined solely by its N terminus as demonstrated by DNA binding and cell-free DNA replication assays. The chimera's ability to mediate DNA replication implied that the N-terminal domain might also be responsible for the site-specific endonuclease activity. Indeed, further study using N-terminal truncation mutants showed that this region constitutes a catalytic domain in and of itself which can be truncated to 187 N-terminal residues while still retaining specific origin binding and endonuclease activities.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials.

All restriction enzymes and Klenow fragment (3′→5′ Exo−) were obtained from New England Biolabs, Inc., except for Pfu polymerase, which was from Stratagene. pET16b and pET15b vectors and respective protein expression systems were from Novagen. HiTrap chelating columns, ATP, deoxynucleoside triphosphates, and poly(dIdC) were obtained from Pharmacia. Synthetic oligonucleotides were made by Gene Link and Sigma-Genosys. [α-32P]dCTP and [γ-32P]ATP was purchased from Amersham.

Cloning of Rep constructs.

Construction of pHisRep78 and pHisRep1, encoding the His-tagged parental proteins Rep78 and Rep1, respectively, was as previously described (48). For Rep78N208Δ, a single product was amplified by Pfu DNA polymerase using primer 1 (5′-CATCATCATCATCACAGCAGCG-3′), primer 2 (5′-CGCAGGTCACAGTGTGTCAATTCTGATTCTCTTTGTTCTGCT-3′), and pHisRep78/16b as the template. In primer 2, nucleotides (nt) at positions 20 to 42 corresponded to nt 922 to 944 in the wt AAV genome, followed by an opal mutation directly adjacent to amino acid 208 of the Rep open reading frame and a DraIII site. The resulting product was cut with NdeI and DraIII and ligated to pHisRep78/16b cut with the same enzymes. For Rep78N208Δ, the sequence between the NdeI and BlpI sites was subsequently recloned into a pET15b vector, which later allowed for efficient thrombin cleavage of the His tag. The same strategy was applied to the cloning of Rep78R187Δ, using primer 1 (above), primer 3 (5′-CGCAGGTCACAGTGTGTCACCGTTTACGCTCCGTGAGATTC-3′), and pHisRep78/15b as the template. Primer 3 is similar to primer 2 in that nt 20 to 41 corresponded to the wt AAV genome (nt 860 to 881), followed by an opal mutation directly adjacent to the codon for arginine 187 of the Rep open reading frame and a DraIII site. This PCR fragment was directly cloned into a pET15b vector for later removal of the His tag. Overlapping PCR mutagenesis was used as previously described (48) clone the chimeric constructs, with the following modifications. For Rep78/1V232, two separate products were amplified using (i) primer A (5′-CATCATCATCATCACAGCAGCG-3′), primer A' (5′-GTTATCCCCATTTCCACGAGCCA-3′) and pHisRep78/16b as the template and (ii) primer B (5′-TGGCTCGTGGAAATGGGGATAAC-3′), primer B' (5′-CCTCAAGACCCGTTTAGAGGC-3′), and pHisRep1/16b as the template. In primer A', nt 1 to 11 correspond to nt 1242 to 1252 of the wt GPV genome and nt 12 to 23 correspond to nt 1010 to 1021 in the wt AAV genome. In primer B, nt 1 to 12 correspond to AAV nt 1010 to 1021, while nt 13 to 23 correspond to GPV nt 1242 to 1252. The resulting PCR products were gel purified, combined, and reamplified in the presence of primers A and B'. This full-length product of 2.1 kb was then cut with SacII and BamHI and ligated to pHisRep78/16b, which was cut with the same enzymes and gel purified. Rep1/78E235 was cloned in a similar manner as its counterpart using (i) primer C (5′-ATTGTGAGCGGATAACAATTCCC-3′), primer C' (5′-GTAATCCCCTTTTCAATGAGCCA-3′), and pHisRep1/16b as the template and (ii) primer D (5′-TGGCTCATTGAAAAGGGGATTAC-3′), primer D' (5′-GGTGTTGGAGGTGACGATCAC-3′), and pHisRep78/16b as the template. In primer C', nt 1 to 11 correspond to GPV nt 1020 to 1030, while nt 12 to 23 correspond to AAV nt 1230 to 1241. In primer D, nt 1 to 12 correspond to GPV nt 1230 to 1241, and nt 12 to 23 correspond to AAV nt 1020 to 1030. The full-length product of 1.4kb was cut with NsiI and DraIII and ligated to pHisRep1/78K343 cut with the same enzymes. pHisRep1/78K343 is a chimeric construct, previously cloned in our laboratory, consisting of the Rep1 amino terminus and Rep78 carboxy terminus joined at a common BpuAI site. For Rep78N208Δ(Y156F), two separate PCR products were generated using (i) primer 1 and primer 4 (5′-GGGGAGCAAGAAATTGGGGATG-3′) and (ii) primer 5 (5′-CAGAGAGAGTGTCCTCGAGCC-3′) and primer 6 (5′-CATCCCCAATTTCTTGCTCCCC-3′), with pHisRep78N208Δ/15b as template (primers 4 and 6 are complementary and correspond to AAV 776 to 797 with a mutation occurring in the codon coding for tyrosine 156 of the Rep open reading frame, resulting in a point mutation at this amino acid position to phenylalanine). These two fragments were combined and amplified using primer 1 and primer 5, cut with SacII and DraIII, and ligated to pHisRep78/15b cut with the same enzymes. In all cases, products generated by PCR were verified by sequencing.

Protein purification.

Rep78, Rep1, chimeric Rep constructs (cloned into the pET16b vector), and Rep78N208Δ and Rep78R187Δ (cloned into the pET15b vector) were expressed in BL21(DE3) strain Escherichia coli carrying pLysS. The resulting His-tagged proteins were isolated according to the manufacturer's instructions with the following modifications. Briefly, cultures were induced with 1 mM IPTG (isopropyl-β-d-thiogalactopyranoside) for 1.5 h at 37°C (for Rep78, Rep78N208Δ, and Rep78R187Δ), 2 h at 37°C [for Rep78/1V232 and Rep78N208Δ(Y156F)], 1.5 h at 30°C (for Rep1), or 4 h at 20°C (for Rep1/78E236). Induced cells were pelleted and freeze-thawed prior to sonication in commercial binding buffer containing protease inhibitors (Novagen). Cell lysates were loaded onto a 1-ml nickel affinity column and washed with increasing imidazole concentrations up to 100 mM (for Rep78, Rep78N208Δ, and Rep78R187Δ), 60 mM [for Rep78/1V232 and Rep78N208Δ(Y156F)], or 200mM (for Rep1 and Rep1/78E236). Proteins were eluted in buffer containing 1 M imidazole (for Rep78 and Rep78/1V232), 500 mM imidazole [for Rep1, Rep1/78E236, Rep78R187Δ, and Rep78N208Δ(Y156F)], or 400 mM imidazole (for Rep78N208Δ). The eluted proteins were then desalted over a Sephadex G-25 column which was equilibrated in protein storage buffer (25 mM Tris · Cl [pH 7.5], 0.1 mM EDTA, 1 mM dithiothreitol [DTT], 0.01% NP-40, and 20% glycerol) containing 50 mM NaCl (for Rep1 and Rep78/1V232) or 250mM NaCl (for Rep78 and Rep1/78E236). Rep78N208Δ, Rep78N208Δ(Y156F), and Rep78R187Δ were desalted into thrombin buffer and digested to remove the His tag. Following digestion, each protein was reloaded onto a nickel affinity column and the flowthrough was reequilibrated in protein storage buffer containing either 250 mM NaCl [for Rep78N208Δ and Rep78N208Δ(Y156F)] or 200 mM NaCl (for Rep78R187Δ). Determination of salt concentrations in the storage buffer for each protein was based on optimization performed with the parental Rep proteins (48). All proteins were frozen as aliquots in liquid N2 and stored at −80°C. Protein concentrations were determined using the Bio-Rad protein assay reagent as per the manufacturer's instructions.

Generation of substrates.

Substrates for electrophoretic mobility shift assays (EMSA) and helicase assays were radiolabeled using Klenow fragment as previously described (48). The replication substrate, pBSori (see Fig. 5A), was made by cloning the respective origin into pBluescript via XbaI and SalI restriction sites. The plasmid was then linearized by digestion with NaeI, phenol-chloroform extracted, ethanol precipitated, and resuspended in 0.5× TE (5 mM Tris · Cl [pH 8.0], 0.5 mM EDTA [pH 8.0]). Endonuclease assay substrates were generated by first kinase labeling the TRS-containing oligonucleotide and then annealing the labeled oligonucleotide to the appropriate complementary strand.

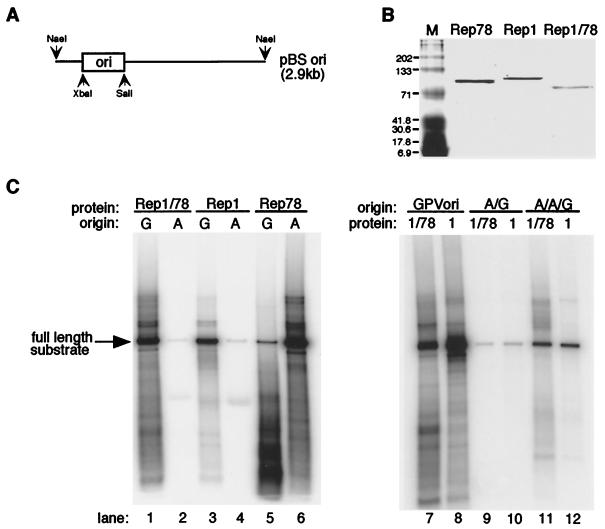

FIG. 5.

AAV Rep78 origin-mediated replication can be redirected through N-terminal domain exchange with GPV Rep1. (A) Schematic representation of the replication substrate used in this assay, pBSori: AAVori, GPVori, A/Gori, and A/A/Gori oligonucleotides (Fig. 2B) were cloned into pBluescript at the XbaI and SalI sites. The plasmid was subsequently linearized approximately 300 bp 5′ to the origin sequences using NaeI. (B) SDS–8% polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis of isolated proteins used in these assays. Lane M, molecular weight standard (Bio-Rad). Approximate molecular masses are indicated in kilodaltons. (C) In vitro DNA replication assays using endogenous and heterologous substrates, using Rep1/78E235 as well as the parental Rep proteins Rep78 and Rep1. wt origins, GPVori (G) and AAVori (A); chimeric origins, A/Gori (A/G) and A/A/Gori (A/A/G) (Fig. 2B).

DNA helicase assay.

The DNA helicase assay was performed as described previously (48). In short, in a reaction volume of 10 μl, 50 or 100 ng of protein was incubated for 30 min at 37°C in the presence of 50 fmol of Klenow-labeled RS1 (Fig. 2B). Each protein was adjusted to 50 ng/μl in the appropriate storage buffer, and a total of 2 μl of protein and/or buffer was added to each reaction mixture. Reactions were terminated by quick-chilling on an ice water bath. After the addition of 3 μl of loading buffer, a total of 10 μl was loaded onto an 8% polyacrylamide gel. The electrophoresed gel was then fixed, dried, and visualized on a STORM860 PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics). Quantification of PhosphorImager data was performed using Imagequant version 1.11 software (Molecular Dynamics).

Cell-free replication assay.

Cell-free replication assays were performed as described previously (48). Reaction mixtures containing 100 ng of origin template DNA were preincubated for 3 h prior to addition of [α-32P]dCTP and Rep protein to minimize incorporation of labeled dCTP through DNA repair mechanisms. Upon addition of [α-32P]dCTP and 75 ng of Rep protein, reaction mixtures were incubated at 37°C for 16 h, reactions were terminated by passage over a Sephadex G-50 spin column, and the products were digested with proteinase K (Boerhinger Manhinem). Replication products were analyzed by electrophoresis on 0.8% agarose gels in 90 mM Tris · borate (pH 8.3)–2 mM EDTA (1× TBE) and visualized as in the EMSA and helicase assays.

EMSA.

Except where indicated, assays were performed as follows. In a total reaction volume of 14 μl, 100 ng of protein was incubated with 30 fmol of radiolabeled DNA in a buffer consisting of 0.25× TBE, 14.3 mM NaCl, 0.9 mM DTT, 0.04% NP-40, 400 ng of poly(dIdC), and 3 μl of loading buffer (40% sucrose, 1% xylene cyanol, and 1% bromophenol blue in 0.25× TBE). After incubation for 10 min at room temperature, 7 μl of the total reaction volume was loaded onto a 6% polyacrylamide gel in 0.25× TBE, incubated for an additional 10 min, and run at 18 V/cm at room temperature. Electrophoresed gels were then fixed in 10% trichloroacetic acid, dried, and visualized as in the helicase assay.

Endonuclease assay.

Nicking assays were performed as previously described (6, 23), with minor modifications. Briefly, 20-μl reaction mixtures contained 25 mM HEPES · KOH (pH 7.5), 1 mM DTT, 200 ng of bovine serum albumin, 5 fmol of 5′-labeled DNA, and, where indicated, 1mM ATP and metal cofactor. Typically, 1 pmol of Rep78 or Rep78(K340H) was added to the reaction mixtures, while truncation mutants required larger amounts in order for activity to be observed, usually 20–40 pmol. After incubation for 1 h at 37°C, reaction mixtures were proteinase K digested for 1 h at 50°C and ethanol precipitated in the presence of 2 μg of sonicated salmon sperm DNA (as carrier) and approximately 10 mM MgCl2 (to facilitate precipitation of single-stranded reaction products). Precipitated DNA was resuspended in loading buffer, heated to 95°C for 5 min, and fractionated on either 15 or 12% polyacrylamide gels in 1× TBE containing 50% urea. Bands were visualized using a STORM860 PhosphorImager (Molecular Dynamics).

RESULTS

Design, overexpression, and isolation of enzymatically active chimeric Rep proteins.

In order to identify a minimal origin interaction domain and to test the feasibility of redirecting origin specificity, chimeric AAV/GPV Rep proteins were generated. Chimeric proteins were constructed in which the N-terminal origin binding domain of Rep78 was replaced by the corresponding domain from GPV Rep1 (designated Rep1/78E235) and vice versa (designated Rep78/1V232) (Fig. 2A). The chimeras were expressed as His-tagged fusion proteins in E. coli and isolated as described in Materials and Methods. It was our expectation that in each chimera, swapping of a putative origin interaction domain would redirect the origin specificity of the parent protein to that specified by the N terminus of the donor. The junctions within the chimeric proteins were designed to be at or near the initiation methionines of Rep52 and -40 (M225 of Rep78 and M236 of Rep1), at a position where the relatively low homology of the N terminus transitions into the highly conserved central core domain (V232 of Rep78 and E235 of Rep1) (Fig. 2A).

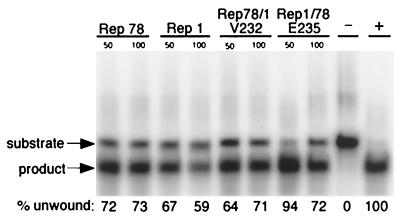

To test whether these chimeras retained enzymatic activity, several functional assays were performed. On an unrelated double-stranded substrate (RS1) (Fig. 2B), both chimeras maintained helicase activity comparable to that of the proteins from which they were derived, indicating that the helicase domains of the chimeric proteins were folded correctly (Fig. 3). Dominant-negative variants (containing a mutation of the nucleotide binding motif) of Rep78 (K340H) (29) and Rep1 (K342H) (48) purified in a manner similar to that for the chimeric proteins did not possess helicase activity (data not shown), demonstrating that the activity was not attributable to a copurifying contaminant.

FIG. 3.

Chimeric Rep proteins are isolated as active helicases. Helicase assay on a duplex DNA substrate, RS1, demonstrates that the chimeric Rep proteins have activities comparable to those of the parental proteins from which they were derived. The indicated amount of protein, in nanograms per reaction mixture, was incubated in the presence of 50 fmol of Klenow-labeled duplex DNA. Both the negative and positive controls were incubated without protein; the positive control was heat denatured prior to being loaded onto the gel. The percentage of substrate unwound by Rep helicase activity is shown for each lane. Dominant-negative mutants of Rep78 and Rep1 did not have helicase activity and were able to inhibit unwinding by the proteins used in this assay (reference 48 and data not shown).

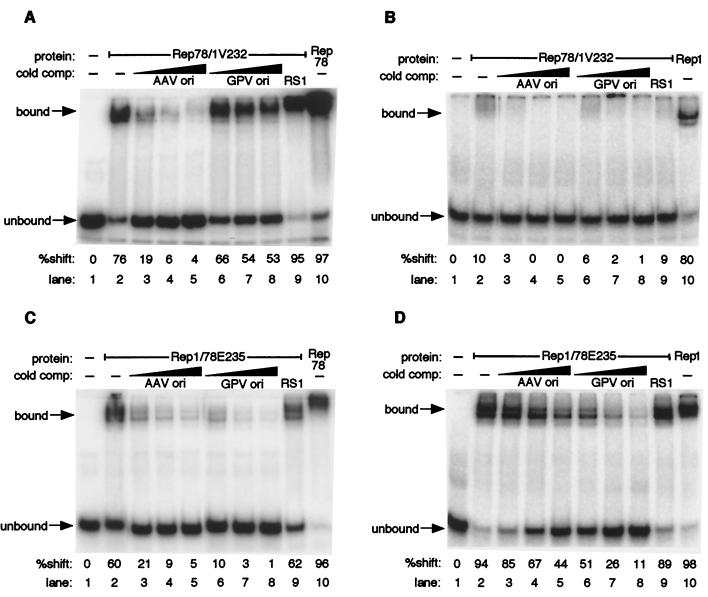

EMSA were used to test the chimeric proteins for the ability to specifically bind origin DNA using both AAVori and GPVori substrates (Fig. 2B). wt Rep78 and Rep1 have been found to interact with both AAV and GPV origin sequences, but each protein shows a marked preference for its cognate origin DNA (48). As shown in Fig. 4, both chimeras exhibit a preference for the origin sequences specific to their respective N-terminal domains. Rep78/1V232 bound 76% of labeled AAVori (Fig. 4A, lane 2) while only weakly binding to GPVori (Fig. 4B, lane 2). Binding by this chimera to each ori substrate was specific, since it was significantly diminished only in the presence of unlabeled specific competitors (origin substrates) and was not altered in the presence of RS1 (Fig. 4A and B, lanes 3 through 9). Thus, Rep78/1V232 binding affinities for both origin substrates parallel those of wt Rep78. Likewise, Rep1/78E235 exhibited binding affinities more similar to those of Rep1. Rep1/78E235 bound 94% of the GPVori probe (Fig. 4D, lane 2) and 60% of the AAVori probe (Fig. 4C, lane 2). Excess unlabeled GPVori efficiently competed for Rep1/78E235 binding to both origin substrates, while AAVori competed well for binding to the AAVori probe and only weakly for binding to the GPVori probe. In both cases, binding was specific, as it was not competed by RS1 (Fig. 4, lanes 9). These data demonstrate that the N-terminal domain is sufficient to direct origin-specific binding in the context of a full-length Rep protein.

FIG. 4.

The amino terminus effectively redirects origin binding specificity of chimeric Rep proteins. EMSA using Rep78/1V232 on the AAV (A) and GPV (B) origins as well as Rep1/78E235 on the AAV (C) and GPV (D) origins are shown. Specific cold competitor substrate was present at a 10-, 25-, or 50-fold excess over labeled substrate. Nonspecific cold competitor, RS1, was present at a 50-fold excess. EMSA were performed as described in Materials and Methods.

The N terminus of GPV Rep1 effectively redirects AAV Rep78-mediated, origin-dependent DNA replication in vitro.

One objective of the study presented here was to test the feasibility of redirecting the origin specificity of the AAV Rep protein as a first step in establishing retargeted, site-specific integration. AAV DNA replication can be initiated by Rep on two different templates, which differ in whether a free 3′ end is already available to serve as a primer (as in an initial AAV infection [Fig. 1A]) or must be produced through Rep endonuclease activity (as in the terminal resolution, viral integration, and rescue of integrated viral genomes [Fig. 1B]). We examined replication as mediated by the chimeric proteins using substrates that would require Rep-mediated endonuclease activity at the TRS for formation of a 3′ primer, thus resembling the substrate involved in site-specific integration. These substrates (Fig. 5A) were constructed by cloning the AAVori or the GPVori (Fig. 2B) into pBluescript, after which the plasmid was linearized approximately 300 bp 5′ to the origin sequence (48). As shown in Fig. 5B, the proteins used in the replication assays are highly purified and show slightly different mobilities. The results of these assays are shown in Fig. 5C. Each parental Rep protein is able to initiate DNA replication efficiently from its cognate origin (Fig. 5C, lanes 3 and 6), while few or no full-length replication products were observed when the opposite origins were used to direct replication (Fig. 5C, lanes 4 and 5). A considerable amount of short replication products was seen with Rep78 on GPVori (lane 5). While these molecules have not yet been characterized, their presence indicates that limited Rep78-dependent DNA replication can be initiated on a GPVori-containing substrate. The extent and specificity of replication observed with Rep1/78E235 (Fig. 5C, lanes 1 and 7) were comparable to those observed with Rep1 on the GPVori substrate tested (lanes 3 and 8). While this chimera efficiently replicates the GPVori substrate, it does not replicate the AAVori substrate (Fig. 5C, lane 2), indicating that the origin specificity of Rep-mediated DNA replication can be altered by exchange of the N-terminal origin specificity domain. No replication was observed using Rep78/1V232 (data not shown).

The notion that the central core domain of AAV Rep contributes to the endonuclease activity at the TRS has been put forward (16). This hypothesis opens the possibility that the specificity of origin interactions by Rep is mediated by two protein domains, i.e., RBS binding by the N terminus and endonuclease activity by the central core domain. Rep1/78E235 contains the N terminus of Rep1 and the central core domain of Rep78. We therefore tested two chimeric origin substrates for possible contributions by Rep78 to TRS specificity (Fig. 2B). The A/Gori and A/A/Gori substrates both contained the GPV RBS and the AAV TRS. In A/Gori the junction between the motifs was placed in the middle of the spacer region. In A/A/Gori both the TRS and the spacer region are derived from AAV and only the RBS motif is from GPV. In no case was replication enhanced by the presence of AAV origin sequences (Fig. 5C, lanes 7 to 12), further supporting the idea that all origin-specific determinants lie within the N-terminal residues of the protein.

The N-terminal 208 amino acids of Rep78 are sufficient for specific origin binding.

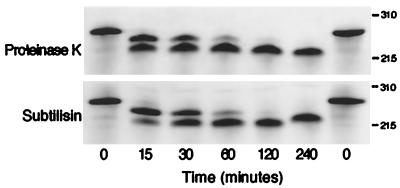

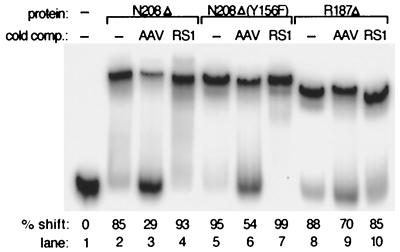

We have observed that the specificities for both RBS binding and TRS endonuclease activity reside in the amino-terminal domain, suggesting the possibility that the amino terminus itself constituted an additional Rep catalytic domain responsible for endonuclease activity. This hypothesis was also supported by previously published observations that an amino-terminal tyrosine residue (Tyr156) is involved in the attachment of Rep to the 5′ end of the nicked substrate (12, 49). In order to determine the possible position of the physical domain border so that this activity could be biochemically isolated, several approaches were employed. First, it has been proposed that the N-terminal 225 amino acids of Rep78/68 are responsible for RBS binding, since Rep52 and Rep40, variants which lack these residues, do not bind the origin DNA (24). We hypothesized that the boundary of the endonuclease domain was located proximal to the initiating methionine of Rep52, in a region of low homology between AAV and other parvoviruses, such as adeno-associated virus type 5 (9) and GPV (68). A ClustalW alignment (Blosum 30 matrix; open gap penalty of 10; extended gap penalty of 0.1) between the Rep proteins of GPV and muscovy duck parvovirus (reference 68 and data not shown) showed that these two proteins are highly homologous (97.5% identical and 99.5% similar within the N-terminal 200 amino acids) yet diverge significantly between amino acids 201 and 210 (2 out of 10 amino acids identical; 4 out of 10 conserved; 4 out of 10 different), suggesting a potential hinge region between two conserved domains. We therefore constructed a variant, Rep78N208Δ (Fig. 2A), which is truncated within this putative linker region at asparagine 208. Limited proteolysis experiments followed by peptide sequencing were also performed. Digestion of Rep68 with the unspecific proteases proteinase K and subtilisin resulted in four major and five minor bands when the products were separated on a sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel (data not shown). In order to simplify the analysis of these experiments, limited proteolysis was performed on Rep78N208Δ (Fig. 6). Prior to proteolysis, the N-terminal His tag was removed by thrombin cleavage followed by repurification over a nickel affinity column. As shown in Fig. 6, digestion of Rep78N208Δ with either proteinase K or subtilisin resulted in a single species with an apparent molecular mass of approximately 21 kDa. Subsequent peptide sequencing indicated that this molecule terminated at amino acid R187 (data not shown), and an additional truncation variant, Rep78R187Δ, was also isolated. Both proteins were tested by EMSA for their ability to specifically bind AAVori DNA. Figure 7 demonstrates the ability of Rep78N208Δ and, to a certain extent, Rep78R187Δ to specifically bind AAVori (lanes 2 and 8), as binding was competed by excess nonradiolabeled AAVori (lanes 3 and 9) but not by an unrelated sequence, RS1 (lanes 4 and 10). It should be noted that to generate the shift observed, a sixfold-higher protein concentration was required for Rep78R187Δ than for Rep78N208Δ (Fig. 7, lane 8).

FIG. 6.

Limited proteolysis of Rep78N208Δ indicates possible physical domain boundaries. Rep78N208Δ (0.4 mg/ml) was subjected to proteolysis by proteinase K and subtilisin. Digests were performed at 4°C in commercial buffers at a protease-to-target protein ratio of 1:10,000. Samples were taken at the time points indicated and visualized via SDS-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis. Approximate molecular masses are indicated in kilodaltons.

FIG. 7.

Rep78 N-terminal truncation mutants can specifically bind AAV origin sequences. EMSA were carried out in a total volume of 20 μl containing 0.25× TBE (pH 8.3), 1 mM DTT, 400 ng of poly(dIdC), 0.05% NP-40, 150 fmol of Klenow-labeled AAVori, 2 μl of loading dye (40% sucrose and 0.1% each bromophenol blue and xylene cyanol in 0.25× TBE), and either 0.5 μg of protein [for Rep78N208Δ and Rep78N208Δ(Y156F)] or 3 μg of protein (for Rep78R187Δ). Unlabeled AAVori or RS1 was used as a cold competitor (comp) where indicated and was present at a 50-fold excess over the labeled substrate.

Amino-terminal endonuclease activity.

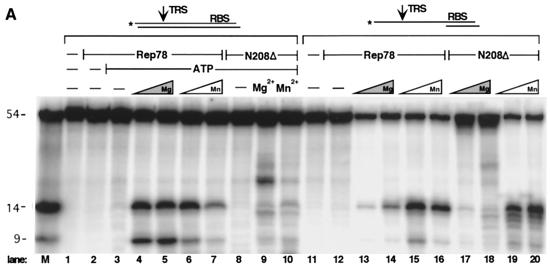

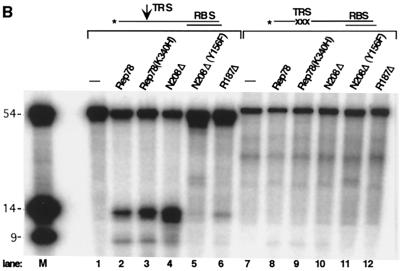

To address the possibility that the N terminus possessed catalytic activity as suggested by the origin-dependent replication assays, we assayed Rep78N208Δ and Rep78R187Δ for endonuclease activity. Because these truncation mutants lacked the domains known to be responsible for helicase activity, we designed partially single-stranded substrates in which helicase activity would not be required for nicking of the TRS (6, 52). As Fig. 8A indicates, wt Rep78 is the only protein tested which can specifically nick AAVori DNA with a double-stranded TRS in an ATP-dependent manner (lanes 4 to 7). In addition, both Mg2+ and Mn2+ can serve as divalent cations in this reaction. However, once helicase activity is rendered unnecessary for TRS nicking (by making the TRS single stranded), Mn2+ is clearly preferred in this reaction (Fig. 8A, lanes 13 to 16). Rep78N208Δ has the ability to nick substrates with a single-stranded TRS (lanes 17 to 20) indicating that the complete catalytic endonuclease domain of Rep is contained within the N-terminal 208 amino acids. Note that in the case of the truncation variants, endonuclease products can be observed only when the assay is performed in the presence of Mn2+ and not when it is performed with Mg2+. In order to demonstrate specificity of this reaction, several controls were included (Fig. 8B). As predicted, the helicase-negative mutant Rep78(K340H) is able to mediate site-specific nicking at the single-stranded TRS (Fig. 8B, lane 3). Change of the active tyrosine to a phenylalanine (Y156F) in Rep78N208Δ abolishes endonuclease activity. Specificity for nicking at the TRS was retained, since significant nicking was not observed on substrates containing mutations within the TRS. As was shown in Fig. 7, Rep78R187Δ binds AAVori DNA. Lane 6 in Fig. 8B also demonstrates site-specific endonuclease activity by this truncation mutant. However, this activity is markedly reduced in comparison to that of Rep78N208Δ, suggesting that the actual domain boundary is better reflected by Rep78N208Δ than by this shorter variant.

FIG. 8.

The N terminus of Rep78 possesses endonuclease activity. Endonuclease assays were performed on 5′-labeled double-stranded or single-stranded TRS substrates as graphically indicated (see also Fig. 2B) and fractionated on denaturing polyacrylamide gels. (A) One picomole of Rep78 or 0.5 μg of Rep78N208Δ was used in each reaction. Where indicated, reaction mixtures also contained 1 mM ATP and either MgCl2 or MnCl2 at 6.25 mM (lanes 4 and 6) or 18.75 mM (lanes 5, 7, 9, and 10). (B) Each reaction mixture contained 1 pmol [for Rep78 and Rep78(K340H)] or 20 pmol (for all N-terminal truncations) of protein and 5 mM MnCl2. Lanes M, 5′-labeled marker oligonucleotides (14 and 9 nucleotides) corresponding in both length and sequence to the expected reaction products (see text for a more detailed discussion). The marker oligonucleotides were incubated under the assay conditions used but in the absence of proteins.

DISCUSSION

The regulatory Rep proteins of AAV have the ability to mediate site-specific integration of the viral DNA into the human host genome. The integration mechanism is thought to be initiated by means of Rep interactions with a Rep-specific origin of replication present on the human target sequence. To date, three steps have been implicated in Rep-mediated origin interaction: Rep recognition and binding to the RBS is followed by partial unwinding of the origin, thus generating a single-stranded TRS as a target for Rep site-specific endonuclease activity.

The identification of domains necessary and sufficient for the specificity of the origin interactions (and thus targeting of integration) by means of mutational analyses is complicated by the fact that Rep is a multifunctional protein for which a panoply of activities have been described, most recently, ligase activity (49). It is not surprising that most of the Rep mutants documented to date show a loss of multiple functions.

In order to overcome these limitations, we have chosen to approach the identification of the origin interaction domain by generating functionally active chimeric Rep proteins. Amino-terminal domain swapping between AAV Rep78 and the corresponding domain of GPV Rep1 resulted in chimeric proteins with biochemical activities comparable to those of the wt proteins as determined by helicase assays. Furthermore, EMSA experiments using unlabeled origin competitor DNA clearly show that Rep78/1V232 specifically binds AAVori substrates while Rep1/78E235 has a specific affinity to GPVori DNA, essentially demonstrating that origin binding specificity can be altered without the apparent loss of biochemical activity.

To further test the feasibility of N-terminal domain exchange for the alteration of origin interaction specificity by Rep78, cell-free DNA replication experiments were performed with Rep1/78E235. The results obtained from these experiments were intriguing in several respects. First, compared to the GPV origin, replication was markedly reduced with the two chimeric origins, A/G and A/A/G, indicating that the TRS specificity could not be attributed to the central core domain as previously proposed (16). These data suggested that the specificity for both the RBS and TRS was determined by the N-terminal 235 amino acids of the Rep protein. This conclusion was clearly supported when wt origins were compared using parental proteins as well as Rep1/78E235. These data demonstrate that N-terminal domain exchange redirects the origin specificity of Rep78 from AAVori to GPVori, thereby indicating that origin specificity is exclusively determined by the N-terminal Rep domain. However, one surprising finding was that Rep78 was able to initiate significant replication activity on GPVori with the vast majority of products at subtemplate length. While the nature of these molecules is unknown, it might be speculated that Rep78 may be able to assemble a replication complex which is capable of initiating an errant type of DNA replication when provided with a suboptimal origin.

Based on the conclusions from our replication data, we hypothesized that the Rep N-terminal domain not only was sufficient to determine origin binding specificity but also contained the necessary motifs for catalytic endonuclease activity. Two amino-terminal truncation mutants of Rep were generated, Rep78N208Δ and Rep78R187Δ. These proteins bound the AAVori as determined by EMSA. However, in order to achieve binding, sixfold-greater protein concentrations were required for Rep78R187Δ than for Rep78N208Δ, indicating that truncation of Rep at R187 had disturbed the integrity of the origin binding domain. Together with the data generated by limited-proteolysis analyses, these results suggest that amino acids 187 through 208 form a relatively unstructured region within Rep that becomes structured in the presence of specific DNA and in this conformation contributes to the ability of Rep to specifically interact with the RBS.

Nicking assays using the amino-terminal truncation mutants were performed using either Mg2+ or Mn2+ on both fully double-stranded substrates and on substrates in which the TRS region was single stranded. As expected, fully double-stranded templates were nicked only by full-length Rep78 (i.e., a molecule that retains an active helicase domain), while no endonuclease activity was observed with Rep78N208Δ. When partially single-stranded substrates were used, both Rep78 and Rep78N208Δ showed activity, the latter only in the presence of Mn2+ under these conditions. The truncation variants required higher concentrations than full-length Rep in order for endonuclease activity to be observed, which is also consistent with the EMSA data and may suggest that higher concentrations of the truncation proteins are required for efficient RBS interactions. The activity of Rep78R187Δ was substantially lower than that of Rep78N208Δ, but the presence of a faint product band indicated that the residues required for site-specific nicking were contained within the N-terminal 187 amino acids of Rep. The Rep78R187Δ results suggest that while core catalytic activity can be retained despite the removal of the additional amino acids present in Rep78N208Δ, the integrity of the catalytic domain is rapidly lost. This latter point is supported by the results of Davis et al. (13), who observed endonuclease activity with a construct comprised of the first 200 amino acids of Rep78/68, but at greatly reduced levels compared to the full-length protein. Thus, we conclude that asparagine 208 most closely reflects the physical endonuclease domain boundary.

In summary, our data indicate that the N terminus of Rep constitutes an independent origin interaction domain containing the endonuclease activity required for the initiation of both DNA replication and site-specific integration. Based on our findings, we can now conclude that the wt Rep protein contains three independent metal coordination sites. While it is not clear which divalent cations are used in vivo, in our assays the endonuclease domain can be distinguished from the helicase domain in its Mn2+ dependence. Identification of these residues involved in coordination of the metal ion required for endonuclease activity will provide an idea for the biochemical mechanism for the Rep endonuclease through comparison to other endonuclease families that have been previously characterized (e.g., topoisomerases, recombinase-activating gene proteins [RAGs], integrases, transposases, and bacteriophage replication initiator proteins). Furthermore, cellbased assays can be designed to address the question whether AAV site-specific integration requires DNA replication or, alternatively, whether a site-specific nick introduced by the N terminus is sufficient to initiate this unique recombination event.

We have provided biochemical evidence for the feasibility of retargeting AAV Rep origin specificity through amino-terminal domain exchange with other parvoviruses. Based on the current model for Rep-mediated site-specific integration, our data provide the first evidence that it may be possible to design Rep proteins capable of targeting integration into alternative loci within a human or animal genome.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

M. Yoon and D. H. Smith contributed equally to this work.

We thank Nathalie Dutheil and Zhen-Qiang Pan for helpful discussions and José Trincão for technical assistance with protein purifications.

This work was supported in part by grants DK55609 and DK57746 (to R.M.L.) and T32AI07647 (M.Y.) from the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Balague C, Kalla M, Zhang W W. Adeno-associated virus Rep78 protein and terminal repeats enhance integration of DNA sequences into the cellular genome. J Virol. 1997;71:3299–3306. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3299-3306.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berns K I. Parvoviridae: the viruses and their replication. In: Fields B N, Knipe D M, Howley P M, editors. Fields virology. 3rd ed. Vol. 2. Philadelphia, Pa: Lippincott-Raven; 1996. pp. 2173–2197. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berns K I, Linden R M. The cryptic life style of adeno-associated virus. Bioessays. 1995;17:237–245. doi: 10.1002/bies.950170310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Berns K I, Pinkerton T C, Thomas G F, Hoggan M D. Detection of adeno-associated virus (AAV)-specific nucleotide sequences in DNA isolated from latently infected Detroit 6 cells. Virology. 1975;68:556–560. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(75)90298-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bohenzky R A, LeFebvre R B, Berns K I. Sequence and symmetry requirements within the internal palindromic sequences of the adeno-associated virus terminal repeat. Virology. 1988;166:316–327. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(88)90502-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brister J R, Muzyczka N. Rep-mediated nicking of the adeno-associated virus origin requires two biochemical activities, DNA helicase activity and transesterification. J Virol. 1999;73:9325–9336. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9325-9336.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brown K E, Green S W, Young N S. Goose parvovirus—an autonomous member of the dependovirus genus? Virology. 1995;210:283–291. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheung A K, Hoggan M D, Hauswirth W W, Berns K I. Integration of the adeno-associated virus genome into cellular DNA in latently infected human Detroit 6 cells. J Virol. 1980;33:739–748. doi: 10.1128/jvi.33.2.739-748.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chiorini J A, Kim F, Yang L, Kotin R M. Cloning and characterization of adeno-associated virus type 5. J Virol. 1999;73:1309–1319. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1309-1319.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiorini J A, Wiener S M, Owens R A, Kyostio S R, Kotin R M, Safer B. Sequence requirements for stable binding and function of Rep68 on the adeno-associated virus type 2 inverted terminal repeats. J Virol. 1994;68:7448–7457. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.7448-7457.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chiorini J A, Yang L, Safer B, Kotin R M. Determination of adeno-associated virus Rep68 and Rep78 binding sites by random sequence oligonucleotide selection. J Virol. 1995;69:7334–7338. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7334-7338.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davis M D, Wonderling R S, Walker S L, Owens R A. Analysis of the effects of charge cluster mutations in adeno-associated virus Rep68 protein in vitro. J Virol. 1999;73:2084–2093. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2084-2093.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Davis M D, Wu J, Owens R A. Mutational analysis of adeno-associated virus type 2 Rep68 protein endonuclease activity on partially single-stranded substrates. J Virol. 2000;74:2936–2942. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.6.2936-2942.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dutheil N, Shi F, Dupressoir T, Linden R M. Adeno-associated virus site-specifically integrates into a muscle-specific DNA region. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:4862–4866. doi: 10.1073/pnas.080079397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fife K H, Berns K I, Murray K. Structure and nucleotide sequence of the terminal regions of adeno-associated virus DNA. Virology. 1977;78:475–477. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(77)90124-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gavin D K, Young S M, Jr, Xiao W, Temple B, Abernathy C R, Pereira D J, Muzyczka N, Samulski R J. Charge-to-alanine mutagenesis of the adeno-associated virus type 2 Rep78/68 proteins yields temperature-sensitive and magnesium-dependent variants. J Virol. 1999;73:9433–9445. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.11.9433-9445.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerry H W, Kelly T J, Jr, Berns K I. Arrangement of nucleotide sequences in adeno-associated virus DNA. J Mol Biol. 1973;79:207–225. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(73)90001-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Handa H, Shiroki K, Shimojo H. Complementation of adeno-associated virus growth with temperature-sensitive mutants of human adenovirus types 12 and 5. J Gen Virol. 1975;29:239–242. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-29-2-239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hermonat P L. Adeno-associated virus inhibits human papillomavirus type 16: a viral interaction implicated in cervical cancer. Cancer Res. 1994;54:2278–2281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hermonat P L, Labow M A, Wright R, Berns K I, Muzyczka N. Genetics of adeno-associated virus: isolation and preliminary characterization of adeno-associated virus type 2 mutants. J Virol. 1984;51:329–339. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.2.329-339.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Holscher C, Kleinschmidt J A, Burkle A. High-level expression of adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep78 or Rep68 protein is sufficient for infectious-particle formation by a Rep-negative AAV mutant. J Virol. 1995;69:6880–6885. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6880-6885.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Horer M, Weger S, Butz K, Hoppe-Seyler F, Geisen C, Kleinschmidt J A. Mutational analysis of adeno-associated virus Rep protein-mediated inhibition of heterologous and homologous promoters. J Virol. 1995;69:5485–5496. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.9.5485-5496.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Im D S, Muzyczka N. The AAV origin binding protein Rep68 is an ATP-dependent site-specific endonuclease with DNA helicase activity. Cell. 1990;61:447–457. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90526-k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Im D S, Muzyczka N. Partial purification of adeno-associated virus Rep78, Rep52, and Rep40 and their biochemical characterization. J Virol. 1992;66:1119–1128. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.2.1119-1128.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kotin R M. Prospects for the use of adeno-associated virus as a vector for human gene therapy. Hum Gene Ther. 1994;5:793–801. doi: 10.1089/hum.1994.5.7-793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kotin R M, Linden R M, Berns K I. Characterization of a preferred site on human chromosome 19q for integration of adeno-associated virus DNA by non-homologous recombination. EMBO J. 1992;11:5071–5078. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1992.tb05614.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kotin R M, Menninger J C, Ward D C, Berns K I. Mapping and direct visualization of a region-specific viral DNA integration site on chromosome 19q13-qter. Genomics. 1991;10:831–834. doi: 10.1016/0888-7543(91)90470-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kotin R M, Siniscalco M, Samulski R J, Zhu X D, Hunter L, Laughlin C A, McLaughlin S, Muzyczka N, Rocchi M, Berns K I. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:2211–2215. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.6.2211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kyostio S R, Owens R A. Identification of mutant adeno-associated virus Rep proteins which are dominant-negative for DNA helicase activity. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1996;220:294–299. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1996.0399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kyostio S R, Owens R A, Weitzman M D, Antoni B A, Chejanovsky N, Carter B J. Analysis of adeno-associated virus (AAV) wild-type and mutant Rep proteins for their abilities to negatively regulate AAV p5 and p19 mRNA levels. J Virol. 1994;68:2947–2957. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.5.2947-2957.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kyostio S R, Wonderling R S, Owens R A. Negative regulation of the adeno-associated virus (AAV) P5 promoter involves both the P5 Rep binding site and the consensus ATP-binding motif of the AAV Rep68 protein. J Virol. 1995;69:6787–6796. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.6787-6796.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Labow M A, Graf L H, Jr, Berns K I. Adeno-associated virus gene expression inhibits cellular transformation by heterologous genes. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:1320–1325. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.4.1320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Labow M A, Hermonat P L, Berns K I. Positive and negative autoregulation of the adeno-associated virus type 2 genome. J Virol. 1986;60:251–258. doi: 10.1128/jvi.60.1.251-258.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lefebvre R B, Riva S, Berns K I. Conformation takes precedence over sequence in adeno-associated virus DNA replication. Mol Cell Biol. 1984;4:1416–1419. doi: 10.1128/mcb.4.7.1416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Linden R M, Berns K I. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus: a basis for a potential gene therapy vector. Gene Ther. 1997;4:4–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.gt.3300357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linden R M, Ward P, Giraud C, Winocour E, Berns K I. Site-specific integration by adeno-associated virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:11288–11294. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.21.11288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Linden R M, Winocour E, Berns K I. The recombination signals for adeno-associated virus site-specific integration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:7966–7972. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.15.7966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lusby E, Fife K H, Berns K I. Nucleotide sequence of the inverted terminal repetition in adeno-associated virus DNA. J Virol. 1980;34:402–409. doi: 10.1128/jvi.34.2.402-409.1980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McCarty D M, Ni T H, Muzyczka N. Analysis of mutations in adeno-associated virus Rep protein in vivo and in vitro. J Virol. 1992;66:4050–4057. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4050-4057.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.McCarty D M, Pereira D J, Zolotukhin I, Zhou X, Ryan J H, Muzyczka N. Identification of linear DNA sequences that specifically bind the adeno-associated virus Rep protein. J Virol. 1994;68:4988–4997. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4988-4997.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McCarty D M, Ryan J H, Zolotukhin S, Zhou X, Muzyczka N. Interaction of the adeno-associated virus Rep protein with a sequence within the A palindrome of the viral terminal repeat. J Virol. 1994;68:4998–5006. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4998-5006.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ni T H, McDonald W F, Zolotukhin I, Melendy T, Waga S, Stillman B, Muzyczka N. Cellular proteins required for adeno-associated virus DNA replication in the absence of adenovirus coinfection. J Virol. 1998;72:2777–2787. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.4.2777-2787.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Owens R A, Weitzman M D, Kyostio S R, Carter B J. Identification of a DNA-binding domain in the amino terminus of adeno-associated virus Rep proteins. J Virol. 1993;67:997–1005. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.2.997-1005.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pereira D J, Muzyczka N. The cellular transcription factor SP1 and an unknown cellular protein are required to mediate Rep protein activation of the adeno-associated virus p19 promoter. J Virol. 1997;71:1747–1756. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1747-1756.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ruffing M, Heid H, Kleinschmidt J A. Mutations in the carboxy terminus of adeno-associated virus 2 capsid proteins affect viral infectivity: lack of an RGD integrin-binding motif. J Gen Virol. 1994;75:3385–3392. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-12-3385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryan J H, Zolotukhin S, Muzyczka N. Sequence requirements for binding of Rep68 to the adeno-associated virus terminal repeats. J Virol. 1996;70:1542–1553. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.3.1542-1553.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Samulski R J, Zhu X, Xiao X, Brook J D, Housman D E, Epstein N, Hunter L A. Targeted integration of adeno-associated virus (AAV) into human chromosome 19. EMBO J. 1991;10:3941–3950. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb04964.x. . (Erratum, 11:1228, 1992.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith D H, Ward P, Linden R M. Comparative characterization of Rep proteins from the helper-dependent adeno-associated virus type 2 and the autonomous goose parvovirus. J Virol. 1999;73:2930–2937. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2930-2937.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith R H, Kotin R M. An adeno-associated virus (AAV) initiator protein, Rep78, catalyzes the cleavage and ligation of single-stranded AAV ori DNA. J Virol. 2000;74:3122–3129. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3122-3129.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Smith R H, Kotin R M. The Rep52 gene product of adeno-associated virus is a DNA helicase with 3′-to-5′ polarity. J Virol. 1998;72:4874–4881. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.6.4874-4881.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Smith R H, Spano A J, Kotin R M. The Rep78 gene product of adeno-associated virus (AAV) self-associates to form a hexameric complex in the presence of AAV ori sequences. J Virol. 1997;71:4461–4471. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4461-4471.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Snyder R O, Im D S, Ni T, Xiao X, Samulski R J, Muzyczka N. Features of the adeno-associated virus origin involved in substrate recognition by the viral Rep protein. J Virol. 1993;67:6096–6104. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.10.6096-6104.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Srivastava A, Lusby E W, Berns K I. Nucleotide sequence and organization of the adeno-associated virus 2 genome. J Virol. 1983;45:555–564. doi: 10.1128/jvi.45.2.555-564.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Surosky R T, Urabe M, Godwin S G, McQuiston S A, Kurtzman G J, Ozawa K, Natsoulis G. Adeno-associated virus Rep proteins target DNA sequences to a unique locus in the human genome. J Virol. 1997;71:7951–7959. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.10.7951-7959.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Tratschin J D, Miller I L, Carter B J. Genetic analysis of adeno-associated virus: properties of deletion mutants constructed in vitro and evidence for an adeno-associated virus replication function. J Virol. 1984;51:611–619. doi: 10.1128/jvi.51.3.611-619.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Urabe M, Hasumi Y, Kume A, Surosky R T, Kurtzman G J, Tobita K, Ozawa K. Charged-to-alanine scanning mutagenesis of the N-terminal half of adeno-associated virus type 2 Rep78 protein. J Virol. 1999;73:2682–2693. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.4.2682-2693.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Urcelay E, Ward P, Wiener S M, Safer B, Kotin R M. Asymmetric replication in vitro from a human sequence element is dependent on adeno-associated virus Rep protein. J Virol. 1995;69:2038–2046. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2038-2046.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Walker S L, Wonderling R S, Owens R A. Mutational analysis of the adeno-associated virus type 2 Rep68 protein helicase motifs. J Virol. 1997;71:6996–7004. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.9.6996-7004.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Ward P, Berns K I. In vitro replication of adeno-associated virus DNA: enhancement by extracts from adenovirus-infected HeLa cells. J Virol. 1996;70:4495–4501. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.7.4495-4501.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ward P, Dean F B, O'Donnell M E, Berns K I. Role of the adenovirus DNA-binding protein in in vitro adeno-associated virus DNA replication. J Virol. 1998;72:420–427. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.1.420-427.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ward P, Urcelay E, Kotin R, Safer B, Berns K I. Adeno-associated virus DNA replication in vitro: activation by a maltose binding protein/Rep 68 fusion protein. J Virol. 1994;68:6029–6037. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.6029-6037.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Weitzman M D, Kyostio S R, Carter B J, Owens R A. Interaction of wild-type and mutant adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep proteins on AAV hairpin DNA. J Virol. 1996;70:2440–2448. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.4.2440-2448.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Weitzman M D, Kyostio S R, Kotin R M, Owens R A. Adeno-associated virus (AAV) Rep proteins mediate complex formation between AAV DNA and its integration site in human DNA. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:5808–5812. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.13.5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Wonderling R S, Kyostio S R, Owens R A. A maltose-binding protein/adeno-associated virus Rep68 fusion protein has DNA-RNA helicase and ATPase activities. J Virol. 1995;69:3542–3548. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.6.3542-3548.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Wu J, Davis M D, Owens R A. Factors affecting the terminal resolution site endonuclease, helicase, and ATPase activities of adeno-associated virus type 2 Rep proteins. J Virol. 1999;73:8235–8244. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8235-8244.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Yang Q, Trempe J P. Analysis of the terminal repeat binding abilities of mutant adeno-associated virus replication proteins. J Virol. 1993;67:4442–4447. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.4442-4447.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Young S M, Jr, Xiao W, Samulski R J. Site-specific targeting of DNA plasmids to chromosome 19 using AAV cis and trans sequences. Methods Mol Biol. 2000;133:111–126. doi: 10.1385/1-59259-215-5:111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zadori Z, Stefancsik R, Rauch T, Kisary J. Analysis of the complete nucleotide sequences of goose and muscovy duck parvoviruses indicates common ancestral origin with adeno-associated virus 2. Virology. 1995;212:562–573. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]