Introduction

More than 40 years have passed since Canada’s first reported case of HIV in 1981. As HIV treatment has evolved, so too has the role of the pharmacist in caring for people with HIV. What was once a terminal diagnosis has become a chronic condition with limited impact on life expectancy when managed with contemporary antiretroviral therapy (ART).1-3 Although people with HIV are at increased risk of developing age-related comorbidities compared with people without HIV,2,4,5 they are now hospitalized less frequently for HIV-related complications.6,7 As such, HIV is often managed in outpatient settings. 8 Reflecting on the advances in therapy and changing demographics of this patient population, pharmacists in community and long-term care settings are increasingly caring for people with HIV in their practices.

While the general principles of ART have not changed since the last Canadian publication on the pharmacist’s role in caring for people with HIV, 9 many therapeutic advances have occurred, including options for biomedical HIV prevention and development of long-acting ART. Although many pharmacists have not received comprehensive HIV training, pharmacists are expected to recognize and distinguish between ART for HIV prevention and treatment and to provide person-centred care to individuals on ART, regardless of indication or practice setting.

The HIV cascade of care, a framework used to benchmark progress in HIV management efforts, describes the trajectory from HIV diagnosis to viral suppression,10-15 and similar cascades exist for HIV prevention.16-19 Pharmacists have roles throughout the continuum of HIV prevention and care (Figure 1), underscoring the many ways pharmacists contribute to individual- and population-level HIV prevention and management. This article focuses on the role of the pharmacist within the cascade, serving as a practical guide to new pharmacists providing HIV care, pharmacy students, residents, and community or hospital pharmacists with limited HIV experience. HIV-specific resources are included that further elaborate on concepts discussed in this article, and a list of common terms and abbreviations is included in Appendix 1 in the Supplementary Materials, available in the online version of the article.

Figure 1.

Pharmacist’s role in the HIV cascade of care

Adapted from Ehrenkranz et al. 13

AEs, adverse effects; ART, antiretroviral therapy; DDIs, drug-drug interactions; PEP, postexposure prophylaxis; PrEP, pre-exposure prophylaxis; TasP, treatment as prevention; U=U, undetectable = untransmittable.

HIV prevention, diagnosis and linkage to care

Prevention

The Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC) estimated that, in 2021, there were 1472 new HIV infections in Canada. 20 While a vaccine remains unavailable, there are several strategies to prevent HIV, including treatment as prevention (TasP), nonpharmacologic harm reduction, pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and postexposure prophylaxis (PEP). TasP is the use of antiretroviral (ARV) medication by people living with HIV to suppress their viral load and prevent HIV transmission. 21 Since 2018, Canada has endorsed undetectable = untransmittable (U=U), which means that achieving and maintaining a suppressed HIV viral load with ART prevents sexual transmission. 22 Pharmacists can provide education on TasP/U=U and facilitate access to harm reduction supplies such as condoms and safer injection and inhalation supplies.23-28

As accessible health care professionals in many settings and communities who routinely provide patient education, pharmacists are uniquely positioned to identify individuals at high risk of HIV who may benefit from PrEP. This highly effective prophylaxis strategy involves the use of ARVs by individuals who are HIV-negative to prevent HIV acquisition. 27 Tenofovir disoproxil fumarate in combination with emtricitabine (TDF/FTC) 300/200 mg can be taken daily or, for cisgender men who have sex with men without hepatitis B (HBV), it can also be used on demand (2 tablets 2 to 24 hours before sex, 1 tablet 24 hours after the first dose and 1 tablet 24 hours later). 27 On-demand TDF/FTC, also known as “2-1-1 dosing”, should not be used by people at risk through receptive vaginal sex due to lower tenofovir penetration in genital tissues. 29 Tenofovir alafenamide (TAF)/FTC 25/200 mg is only indicated for daily PrEP dosing to reduce the risk of sexually acquired HIV and is not indicated for people at risk from receptive vaginal sex due to limited evidence. 30 Long-acting injectable cabotegravir every 2 months is approved in the United States for PrEP, 28 and Canada will likely follow. PrEP effectiveness is directly linked to PrEP adherence. 27 Pharmacists can navigate private and public insurance to reduce financial barriers, educate on and support adherence, provide education on the importance of routine HIV and sexually transmitted infection testing, and promote appropriate PrEP discontinuation if/when patients are no longer at risk of acquiring HIV. Pharmacist-led PrEP delivery through ambulatory clinics or community pharmacies provides opportunities for pharmacists to expand their role to include PrEP initiation and monitoring.27,29,31

PEP involves 28 days of ART started within 72 hours following HIV exposure to reduce the risk of HIV acquisition. Regimens vary but often include the combination of 2 nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitors (NRTIs) with a third medication from another class, which is usually an integrase inhibitor (INSTI). Pharmacists can identify patients who would benefit from PEP and link them to care as soon as possible postexposure. 29 They can assist with decisions regarding PEP indication based on risk assessment, optimize regimens to avoid drug-drug interactions (DDIs), improve safety, provide medication education, and discuss adherence strategies and options for PrEP following PEP completion when appropriate. 27 Pharmacists seeking additional information about PrEP and PEP, and their potential role, can refer to the Canadian PrEP and PEP pharmacist guidelines. 27

Pharmacists are also involved in the prevention of perinatal/vertical HIV transmission. This includes providing ART or PrEP to pregnant women and ensuring appropriate ART is available during labour/delivery, including for the infant, according to current treatment guidelines (see Appendix 2). The risk of HIV transmission to the infant can be reduced from ~30% to <1% through the following combination of strategies: achievement of HIV viral suppression of the mother before and during pregnancy, administration of intravenous zidovudine prior to and during delivery, administration of ART to the newborn, and evidence-based, patient-centred decision-making about infant feeding.32,33 Pharmacists can help optimize ART and promote adherence during pregnancy, provide education regarding newborn medication administration, and ensure caregivers have medication supply for the newborn and resources to access formula before discharge.

HIV testing

PHAC recommends HIV testing as part of routine care and that health care providers take active roles in offering HIV testing to patients. 34 However, 13% of Canadians with HIV do not know their status, highlighting a need to improve testing access. 20 To increase awareness, pharmacists can engage with and promote National HIV Testing Day in Canada. 35 Pharmacists should be familiar with HIV testing requirements, including the different types of tests, who should be tested, frequency of testing and how to assess for signs and symptoms of acute HIV. 34 The accessibility of community pharmacies, especially in rural/remote areas, makes them attractive venues for HIV testing. Studies have found patients feel getting an HIV test in a pharmacy is private, discreet, convenient and should be routinely offered.36,37 Health Canada has approved a rapid point-of-care HIV test (INSTI HIV-1/HIV-2 Antibody Test) for administration by trained personnel as well as a self-test (INSTI HIV Self-Test) for home use. Both of these tests require a fingerstick blood sample and have >99% sensitivity and specificity.38,39 Dried blood spot (DBS) testing, which involves collecting fingerstick blood samples on special DBS cards and sending them to a laboratory for processing, is another option that can be offered in community settings. 40 Pharmacists can play important roles in offering testing in pharmacies and counselling on the appropriate use of self-tests by patients for home use.

The currently available HIV point-of-care and self-test kits are considered screening tests only, have a window period of 3 months, and reactive (positive) test results require standard laboratory testing to confirm the diagnosis. In preparing to offer HIV testing, pharmacists should create linkage to care plans, including education and support for positive point-of-care test results, confirmatory testing and, if indicated, referral for HIV care or access to ART for HIV prevention. As of November 2023, HIV self-test kits are covered through funding from the Government of Canada; individuals can access kits through community-based organizations and online mail orders (see Appendix 2). Currently, HIV self-test kits are for patient use only, not for health care provider point-of-care HIV testing. Health care providers can obtain point-of-care tests from wholesalers or directly from test manufacturers. Due to provincial scope-of-practice variations, pharmacists should consult their regulatory bodies before offering HIV testing to ensure they meet provincial requirements such as the need for collaborative practice agreements for confirmatory laboratory testing, quality assurance procedures, and necessary documentation.

Linkage to care

Due to their accessibility, pharmacists are often first in the circle of care to identify when additional support is required. Linkage to care could be in the form of an outreach program referral to facilitate bloodwork or support ART adherence, sending a patient on PrEP with signs and symptoms of acute HIV for urgent assessment and HIV testing, or sending a patient for medical follow-up after pharmacist-initiated PEP. Pharmacists should be familiar with community resources to make appropriate linkages to care.

Unfortunately, structural and psychosocial barriers continue to present challenges for successful linkage to care and initiation of HIV treatment. 20 Nearly half of persons who use drugs avoid HIV services because of stigma and discrimination. 20 Despite this, evidence suggests that people with HIV and substance use disorder are willing to trust and accept care from pharmacists, which positively affects ART adherence. 41 Further, person-centred, culturally safe health care promotes access and retention in care and treatment adherence.42-45 Pharmacists therefore have a responsibility to address stigma and discrimination toward people with HIV to ensure effective linkage to and delivery of care (see Appendix 2 for resources).

Initiation of treatment

ART regimen selection

Baseline assessments

Once a patient is diagnosed with HIV, assessing their willingness to start and adhere to ART is the first step in treatment initiation. 46 Pharmacists can conduct a readiness assessment that includes potential adherence barriers such as houselessness or unstable housing, substance use or certain mental health concerns. 46 If barriers are identified, the pharmacist can problem-solve solutions with the individual, liaise with other health care providers and plan frequent adherence assessments.

When planning ART, pharmacists should perform a best possible medication history. The interview provides time for adherence education, disease state education and DDI information.46-48 Pharmacists should routinely ask about over-the-counter items, complementary and alternative medicines, cultural and traditional medicines and recreational drugs.49,50 Baseline bloodwork drawn prior to ART initiation (see Appendix 3) should be assessed for viral resistance,48-50 which may inform which ARVs are less likely to be effective and should be avoided in the patient’s treatment regimen.51,52 Screening for the HLA-B*5701 allele can identify patients who may be predisposed to a potentially life-threatening hypersensitivity reaction if exposed to abacavir. 53

Selection of initial ART

The initial ARV regimen should be simple, well-tolerated and have a high genetic barrier to resistance. 54 First-line regimens generally consist of 2 NRTIs plus an INSTI. In some situations, alternative regimens comprising 2 NRTIs plus a nonnucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor (NNRTI) or boosted protease inhibitor (PI) may be considered. 53 Dual therapy with dolutegravir/lamivudine is also a guideline-recommended initial regimen, as it has demonstrated effective and durable viral suppression in select populations. 53 ART choice may depend upon baseline resistance and individual patient factors such as comorbidities, 53 adverse effect (AE) potential, drug coverage, patient preference and other considerations outlined in Appendix 3. Pharmacists are encouraged to keep abreast of current treatment guidelines (see Appendix 2).

Rapid ART initiation

Evidence is emerging on the benefits of rapid ART initiation, which refers to treatment initiation on the same day or within a week of HIV diagnosis, often before full laboratory results are available. The goal is to increase treatment uptake and linkage to care and decrease time to viral suppression. Patients with central nervous system opportunistic infections (OIs) may not be candidates for rapid ART, and resource limitations may restrict feasibility. 53 However, initiating ART as early as possible remains a cornerstone of HIV care.55,56 Not all regimens are appropriate for rapid ART; pharmacists should consult current guidelines for up-to-date recommendations.53,54 Through the facilitation of ART access and review of initial regimens, pharmacist involvement can decrease time to ART initiation and increase rapid ART uptake.26,57

Patient education

Patient education can empower informed decision-making. It is important to use patients’ preferred names, the patient’s correct pronouns and customize the style, language and literacy level for each patient’s background and understanding. The goal is for patients to feel comfortable, cared for and willing to discuss issues in a confidential, nonjudgmental, nonpunitive relationship with their pharmacist. Information gathering and patient education should be conducted in private environments. Including family, partners and/or friends during education sessions can be helpful for reinforcement and patient support. Providing written information at a grade 6 literacy level can help with reinforcing information, and in some cases, an interpreter and/or handouts in other languages may be useful. Pharmacists can be valuable referral sources for educational tools, drug information education and patient support.

Initial education should include information regarding ARV administration and storage, food requirements, the importance of adherence, management of missed doses, potential AEs, DDIs and the monitoring and follow-up plan. Information regarding goals of therapy, partner transmission, U=U and pregnancy planning should be included, if applicable. Refer to Appendix 2 for education resources, including information available in multiple languages and guidelines for people-first, nonstigmatizing language.

Drug coverage and acquisition

ARVs are lifelong medications that can be cost-prohibitive to patients without comprehensive coverage. Medication costs may compromise essentials such as food and housing 58 or force patients to alter treatment (e.g., halve doses, skip days or discontinue),59,60 which risks viral breakthrough and ARV resistance. Prior to initiating therapy, the ability to maintain medication access should be established. In Canada, there is no national program that provides free ARVs to all individuals. Several federal programs provide portable coverage for populations such as status First Nations, recognized Inuit, 61 veterans, federally incarcerated individuals and refugee claimants. Each province/territory administers its own program(s) that vary in eligibility, formulary and cost-sharing requirements. Pharmacists should familiarize themselves with and be skilled at navigating patient support programs to reduce out-of-pocket costs. If patients do not qualify for private or public drug programs, pharmacists can suggest lower-cost alternatives or study enrollment to access cost-free medications.

Patients should be told where and how their prescriptions will be filled (e.g., clinic or outpatient hospital pharmacy, specialty pharmacy, community pharmacy). Not all pharmacies regularly stock ARVs, and patients should be advised that advance notice for refills may be required to ensure uninterrupted supply.9,46

Screening and managing DDIs

DDIs between ARVs and comedications may lead to serious consequences.62-65 Some ARVs are substrates, inhibitors (e.g., PIs, elvitegravir-cobicistat) or inducers (e.g., NNRTIs) of the cytochrome P450 isoenzymes; some modulate (e.g., ritonavir) or are affected by uridine diphosphate glucuronosyltransferases (e.g., zidovudine, INSTIs); and some interfere with enzymes or drug transporters such as p-glycoprotein, OATP1B1, MATE1 and OCT2. Although less likely to be perpetrators of DDIs, unboosted INSTIs and second-generation NNRTIs may still be involved with DDIs (e.g., dolutegravir may increase metformin concentrations and gastric acid modifiers may impair rilpivirine absorption). 66

Screening for DDIs should occur when starting or discontinuing prescription and nonprescription medications (including those administered topically, ophthalmically, vaginally, by inhalation, etc.), recreational substances, vitamins, supplements, and cultural and traditional medicines. Polyvalent cations that exist in supplements, protein shakes or antacids, for example, chelate with INSTIs, reducing their absorption.67-69 Cushing’s syndrome and adrenal suppression have occurred with PIs and inhaled or injected corticosteroids.70,71 While some interactions may be managed by separating administration times, other strategies may require adjusting dosages, altering frequency or administering with food, or switching agents. Pharmacists should consult HIV-specific resources (Appendix 2) for DDI guidance. However, not all DDIs have been elucidated and not all are clinically significant or predictable. In such cases, pharmacists should assess potential harms of drug combinations, inform providers and patients of possible consequences and suggest appropriate monitoring plans.

Key populations

Advanced HIV and immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome

OI prophylaxis or treatment may be necessary for persons with advanced disease (people with AIDS-defining illnesses or CD4 <200 cells/mm3). 45 Pharmacists can screen for appropriate initiation or discontinuation of OI prophylaxis, ensure that prophylaxis is not used when there are signs and symptoms suggestive of active OI, 72 facilitate access to OI medications and prevent and manage AEs.

Immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome (IRIS) is a pathogen-specific exaggerated inflammatory response that may occur when the immune system begins to recover following ART initiation in advanced HIV. 53 Pharmacists can assist in determining the timing of ART initiation in patients with active OIs. For instance, to reduce the risk of severe IRIS in patients with cryptococcal meningitis, ART initiation should be deferred for several weeks after starting antifungals. 73

Women

In Canada, approximately 30% of new HIV infections and nearly one-quarter of all people with HIV are women. 74 Women and families living with HIV may face unique challenges. Women are often the primary caregivers for their families and may require additional support. Women have been underrepresented in ART clinical trials, and the incidence and types of ARV AEs may differ from men. For instance, women generally experience greater weight gain with ART. 53

Pharmacists can optimize drug therapy for women with HIV of all ages. For women of childbearing potential, pharmacists can help identify and support patients who would like hormonal contraception or aid in the selection of safe and effective ART for pregnancy. Not all ARVs are safe in pregnancy, and some may be less effective due to pregnancy-induced pharmacokinetic changes. 32 Finally, more women with HIV are experiencing menopause due to improved life expectancies. Although there are no DDIs with ART that contraindicate the use of hormone replacement therapy (HRT), 75 HRT is underused in this population. 75 Pharmacists can recommend specific HRT and manage any DDIs that exist with ART.

Pediatrics

Infants can acquire HIV during pregnancy, delivery or breastfeeding. Older children and adolescents can acquire HIV through unprotected sex or contaminated equipment. Early ART initiation has been associated with reduced viral reservoirs, 76 better neurodevelopment 77 and decreased infant mortality and disease progression. 78

Pediatric ART considerations include the limited evidence available for pediatric populations; ability to swallow pills; availability of liquid, chewable or granule formulations; availability of pediatric doses; dosing based on age/weight (e.g., mg/kg or body surface area [mg/m2]); developmental stage; and the need to regularly adjust doses for growth. Pharmacists play a pivotal role in navigating these factors. Discussion with the caregiver (and child when appropriate) on adherence is fundamental and should be assessed and discussed at each appointment. Incomplete ART adherence can lead to the development of drug-resistant mutations, limit treatment options and result in more complex ART for years to come. Advocacy is needed for the inclusion of children in clinical trials for the development of child-friendly ARV dosages and formulations.

Other key populations

While principles of ART selection are generally consistent across populations, additional considerations are sometimes applicable. Some groups, such as Indigenous peoples, 74 transgender persons 79 and people with experience in the prison system 80 may be disproportionately affected by HIV, whereas others, such as those in rural/remote communities, may face challenges accessing HIV care. 81 Following release from corrections, some people with HIV may require intensive support to remain engaged in care. 82 Others, such as refugees, may be more likely to present with advanced HIV and require additional support with linkage to care. 83

Table 1 provides a pharmacist’s guide to caring for the key populations discussed in this article.

Table 1.

A pharmacist’s guide to providing HIV care to key populations

| Population | Considerations | Pharmacist’s role | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| Advanced HIV | • People with advanced HIV (CD4 count <200 cells/mm3) are at risk of morbidity and mortality secondary to opportunistic infections and other AIDS-defining illnesses such as Kaposi sarcoma and lymphoma.72,84

• IRIS is a pathogen-specific exaggerated inflammatory response that may occur when the immune system begins to recover following ART initiation in the context of an opportunistic infection. 53 |

• For patients with active OIs, ensure treatment is initiated and continued for the full duration of induction, consolidation or maintenance therapy. • For patients at risk of OIs, ensure OI prophylaxis is prescribed when indicated and discontinued when discontinuation criteria are met. • Recommend G6PD screening tests prior to starting dapsone or primaquine. • Manage AEs and DDIs with OI medications. |

DHHS Guidelines for the Prevention and Treatment of Opportunistic Infections: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines ASHP Guidelines on Pharmacist Involvement in HIV Care, section on Pharmacist Involvement on Management of OIs: https://www.ashp.org/-/media/assets/policy-guidelines/docs/guidelines/pharmacist-involvement-hiv-care.ashx |

| Women | • Incidence and types of ART AEs may differ from men (e.g., ART-induced weight gain: women > men; risk of TDF-induced bone density losses in postmenopausal women > men).

53

• Not all ARVs are safe and effective in pregnancy 32 (see Appendix 2). • Surveillance programs for the collection of postmarketing safety data among pregnant women on ART helps build evidence for specific ARVs in pregnancy. 85 |

• Consider a woman’s plans or ability to become pregnant when selecting ART. • Help identify and select hormonal contraception options compatible with ART. • Monitor and report ART-related AEs experienced by women for postmarketing surveillance. • Recommend HRT when indicated and manage any DDIs that exist with ART. |

Patient resources for pregnancy care for women with HIV: https://www.catie.ca/prevention/pregnancy-and-infant-feeding

Canadian Perinatal HIV Surveillance Program: https://www.cparg.ca/surveillance-bull-cphsp.html Canadian HIV Pregnancy Planning Guidelines: https://www.hivpregnancyplanning.com/ |

| Pediatrics | • Early ART initiation is associated with improved neurodevelopment

77

and decreased mortality and disease progression.

78

• Incomplete adherence to ART can lead to resistance, limiting treatment options and increasing ART complexity for life. |

• Source pediatric ART formulations and counsel on techniques to increase palatability when pediatric formulations not available. • Dose-adjust ART as children grow. • Discuss importance of adherence with caregivers (and child, when appropriate for age and developmental stage). • Advocate to include children in clinical trials to expand available treatment options. |

Information on crushing and liquid formulations: https://hivclinic.ca/main/drugs_extra_files/Crushing%20and%20Liquid%20ARV%20Formulations.pdf Canadian Pediatric & Perinatal HIV/AIDS Research Group: www.cparg.ca |

| Transgender individuals | • Factors contributing to elevated HIV prevalence among trans persons include stigma, sex work and inaccurate risk perception.

79

• Many encounter significant barriers in accessing culturally competent health care. 53 • Concerns regarding DDIs between ARVs and GAHT may affect willingness to take ART. |

• Facilitate access to costly (e.g., gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists) or restricted treatments (e.g., testosterone is a scheduled controlled substance).

86

• Counsel on and provide risk-reduction strategies (e.g., smoking cessation to reduce venous thromboembolism risk with estrogen). • Manage DDIs between ART and GAHT 87 (e.g., there are no significant DDIs between GAHT and INSTIs). • Provide referral to practitioners specializing in transgender care. |

Providing LGBTQ-Inclusive Care and Services at Your Pharmacy: https://www.thehrcfoundation.org/professional-resources/providing-lgbtq-inclusive-care-and-services-at-your-pharmacy

Sexual Orientation, Gender Identity & Gender Expression (SOGIE): Safer Spaces Toolkit (Alberta Health Services): https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/pf/div/if-pf-div-sogie-safer-places-toolkit.pdf 2SLGBTQIA+ resources: https://opatoday.com/2slgbtqia-resources/ |

| Immigrants and refugees | • Some may struggle with HIV-related stigma, fear of persecution and/or post-traumatic stress disorders related to premigration trauma. • Consider the presence of opportunistic coinfections endemic to their home countries. |

• Reduce barriers to medication access by being familiar with billing federal health insurance for refugees (e.g., interim Federal Health). • Provide counselling and drug information in the patient’s preferred language via reliable interpreters. • Referrals to medical clinics that specialize in care for immigrants and refugees. |

Multilingual HIV resources: www.aidsmap.com https://aidsinfo.unaids.org/ On-demand interpreter services: Provincial language services: http://www.phsa.ca/our-services/programs-services/provincial-language-services (British Columbia only) |

| Indigenous peoples | • Stigma, racism, discrimination and both previous and ongoing colonial policies and practices influence Indigenous peoples’ health and affect access to care. 88 | • Reduce barriers to medication access by being familiar with pharmacy benefits for First Nations and Inuit peoples (e.g., Non-Insured Health Benefits). • Enroll in continuing education and training programs to understand how colonialism and systemic racism have contributed and continue to contribute to HIV prevalence among Indigenous peoples. • Provide culturally competent and sensitive care. |

San’yas: Indigenous cultural safety training: www.sanyas.ca Unmet needs of Indigenous peoples living with HIV:https://www.ohtn.on.ca/rapid-response-unmet-needs-of-indigenous-peoples-living-with-hiv/ Resources for Pharmacy Professionals to Support Indigenous Cultural Competency:https://www.ocpinfo.com/about/equity-diversity-and-inclusion/resources-to-support-indigenous-cultural-competency/ Communities, Alliances and Networks (CAAN; formerly Canadian Aboriginal AIDS Network): https://caan.ca/ Indigenous Pharmacy Professionals of Canada: https://www.pharmacists.ca/pharmacy-in-canada/ippc/ |

| Remote communities | • Numerous barriers to accessing HIV care (travel and associated costs), missing work, family responsibilities, privacy concerns.

89

• Telehealth technology can improve access but has limitations (e.g., inability to perform physical exams, access requires smart phones/devices with reliable Internet connection). 90 |

• Be familiar with relevant provincial/territorial and organizational protocols for conducting telemedicine care. • Explore medication delivery options and encourage patients to keep an emergency supply of ART on hand. |

Rapid Response Service. Rapid Response: HIV Services in Rural and Remote Communities: https://www.ohtn.on.ca/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/RR73-2013-Rural-ASO.pdf |

| Incarcerated persons | • Pharmacist involvement in a multidisciplinary team improves care of incarcerated people with HIV.

91

• Telemedicine pharmacy services can improve clinical outcomes. 92 |

• Ensure prompt and appropriate continuation of ART upon admission. • Provide adherence counselling to empower inmates to develop skills they will need in the community following release. • Refer to case management and ensure discharged medications are filled prior to release. |

Treatment of medical, psychiatric and substance-use comorbidities in people infected with HIV who use drugs. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20650518/ |

AE, adverse event; ART, antiretroviral therapy; ARV, antiretroviral; ASHP, American Society of Health-System Pharmacists; CD4, cluster of differentiation 4; DDI, drug-drug interactions; DHHS, Department of Health and Human Services; G6PD, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase; GAHT, gender-affirming hormone therapy; HRT, hormone replacement therapy; INSTI, integrase inhibitor; IRIS, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; OI, opportunistic infections; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Achievement and maintenance of viral suppression

Managing AEs

While newer ARVs have improved safety profiles, they still have potential to cause AEs, including renal, cardiovascular, metabolic, neuropsychiatric, cutaneous and gastrointestinal toxicities. Pharmacists can educate on AEs and provide recommendations on prevention and management.

In general, most commonly prescribed ARVs are well-tolerated, and AEs such as headache, nausea and vomiting are self-limiting. Although rare, severe AEs have been reported with newer ARVs.93-96 Pharmacists can educate patients to continue ART and advise when to seek medical attention. Some neuropsychiatric AEs such as insomnia can be mitigated by changing administration time (e.g., bedtime dosing of efavirenz; morning dosing of dolutegravir, bictegravir). Generally, dose reductions are not recommended to manage AEs. If an AE is bothersome and persistent despite management strategies, consider switching ART. Pharmacists can help determine if toxicities are drug-related and recommend treatment modification.

Consideration of long-term AEs is important when individualizing ART.97-100 For example, TDF (and to a lesser extent, TAF) may cause renal impairment and decreases in bone density,97,101 while PIs have been associated with an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases and delayed conduction through the atrioventricular node (PR prolongation).98-100,102 Several studies have reported greater weight gain with certain ART. INSTIs, specifically dolutegravir and bictegravir, have been associated with more weight gain than other ARVs.103-105 Greater weight increase has also been reported with TAF vs TDF 103 and with rilpivirine vs efavirenz. 105 Pharmacists must consider the impact of long-term AEs on a patient’s comorbidities, assess risk factors and balance potential harms with benefits prior to making treatment recommendations.

Strategies for supporting adherence and preventing resistance

ART adherence is fundamental in maintaining viral suppression and immune function, and preventing drug resistance. Multiple studies show positive pharmacist impact on ART adherence.106,107 Strategies such as adherence packaging/devices, daily/weekly dispensing, medication delivery, pairing ART with opioid agonist therapy dispensing, refill reminders, reminder devices (e.g., cell phone alarms) and weekly phone calls are beneficial when suboptimal adherence is identified. 108 Pharmacists offering supportive dispensing services should closely monitor adherence and inform prescribers if challenges are identified.

Adherence education remains a cornerstone of HIV care and should always be patient-centred, nonjudgmental, culturally safe and trauma-informed and, when necessary, involve motivational interviewing strategies. 108 Pharmacists should strive to identify reasons for adherence challenges, to make tailored recommendations to improve adherence. 108 Switching to a single-tablet regimen may help patients struggling with pill burden. Switching to smaller oral tablets or a long-acting injectable regimen may be advantageous for patients with swallowing difficulties.

ART interruptions should be avoided. Pharmacists are well-positioned to assist with strategies to prevent treatment interruptions. 108 For example, if medications are often lost or stolen, ensure patients know how to obtain replacement supplies and/or consider dispensing smaller quantities more frequently. If patients are travelling, ensure sufficient quantity is dispensed to cover extended absences. If patients are experiencing financial barriers, assist with enrolling in provincial/federal drug programs, special authorizations and/or patient support programs. Finally, for patients experiencing frequent refill gaps, ensure they are on a regimen with a high barrier to resistance, ask if refills are needed, offer adherence aids or programs to make refilling easier, notify prescribers of possible suboptimal adherence and connect patients with outreach supports.

Patients may experience swallowing difficulties or be unable to take medications orally for a variety of reasons, including baseline aversions to swallowing tablets, aging or acute injury or illness. These situations pose unique challenges to managing ART as most ARVs are available only in solid oral dosage forms. Generally, limited data exist for the effectiveness and safety of crushing ART, and pharmacists are encouraged to use available resources to manage ART in these settings (Appendix 2).

Managing comorbidities

Noninfectious comorbidities

Comorbidities are common among people with HIV, and the achievement and maintenance of viral suppression often involve successful comorbidity management. Some comorbidities, such as psychiatric conditions and substance use disorders, can affect ART adherence, decreasing the likelihood of viral suppression.109,110 Others, such as osteoporosis, chronic pain and cardiovascular and metabolic disease, may occur as a result of the interplay between ART exposure, aging and/or HIV infection itself.46,73,111-113 Tobacco use (e.g., cigarette smoking, chewing tobacco, etc.) is a major contributor to early morbidity and mortality among people with HIV, and pharmacists can play a significant role in assistance with tobacco cessation. The HIV-positive transplant and oncology population is at risk for many DDIs. 114 Pharmacists should select ART to mitigate DDIs and monitor for their effects, particularly when starting/stopping ritonavir or cobicistat-boosted ART. Table 2 outlines considerations for managing comorbidities in people living with HIV.

Table 2.

A pharmacist’s guide to managing comorbidities among people with HIV

| Comorbidity | Considerations | Pharmacist’s role |

|---|---|---|

| Psychiatric comorbidities | • Common among people with HIV; can affect ART adherence.46,110 | • Offer integration of ART dispensing and help design medication regimens that fit a patient’s lifestyle.46,115

• Monitor for neuropsychiatric effects that may occur with certain ART regimens (e.g., efavirenz, rilpivirine, INSTIs) and DDIs.46,53,116,117 |

| Substance use disorder | • DDIs between some ART and recreational substances exist that can lead to overdose (e.g., fentanyl and MDMA; no significant interaction with cannabis).

118

• DDI concerns between ART and recreational substances should not preclude a patient from HIV treatment. |

• Ask about recreational drug use, including frequency and route, in a nonjudgmental nature. • Counsel on DDIs that may occur between HIV regimens and OAT or recreational substances; offer harm reduction strategies when appropriate (e.g., naloxone kits). |

| Osteoporosis (OP) | • People with HIV are at increased risk of OP and fractures compared with the general population.111,112

• Some ARVs are associated with negative effects on bone density markers (TDF, particularly when boosted by ritonavir or cobicistat).53,119 • OP treatment modalities may be underused among people with HIV. 120 |

• Identify those at risk for OP and fractures

121

and assist with ART optimization for bone health (e.g., switch to a regimen free of TDF). • Help modify non-ART-related risk factors for OP (e.g., encourage weight-bearing exercise, smoking cessation, calcium/vitamin D supplementation). • Counsel patients on how to manage/avoid INSTI-cation DDIs. • Help remove patient-specific barriers to OP treatment when indicated.122,123 |

| CV disease | • People with HIV are at increased risk of CV disease as a result of proinflammatory effects of HIV, AEs of some ART (e.g., some ARVs have negative effects on lipid profiles) and an increased prevalence of certain traditional cardiovascular risk factors, such as smoking and alcohol use.124-126

• Controversy exists around the cardiovascular safety of abacavir: while an association between abacavir and MI risk has been identified in observational studies, no such association was found in the largest meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.127,128 • Many DDIs with medications used for CV disease interact with ART that induce or inhibit cytochrome P450 enzymes, including some statins, antiplatelets, anticoagulants and calcium channel blockers.129,130 |

• Optimize ART regimens to minimize CV risk (e.g., if significant CV risk, consider avoiding abacavir due to possible association with MI; consider effect of PIs and TAF on lipids). • Encourage smoking cessation via counselling and provision of pharmacotherapy. |

| Tobacco use disorder | • People on ART lose more life-years to smoking than HIV itself,131,132 and although the life expectancy gap between people with HIV and the general population is diminishing, people with HIV have fewer comorbidity-free years,2,133 likely due to the higher smoking prevalence among people with HIV.124,131

• Competing priorities in HIV care can distract health care providers from addressing smoking cessation. 134 • With prescribing authority for smoking cessation pharmacotherapy in many provinces, pharmacists have potential to make dramatic health impacts in this population. |

• Assess smoking status in all patients and, whenever appropriate, offer and prescribe smoking cessation services. • Screen for and manage DDIs between ARVs and pharmacotherapy for smoking cessation. • Ritonavir, efavirenz and nevirapine may decrease bupropion concentrations.66,134,135 • No anticipated clinically significant DDIs between ARVs and varenicline or nicotine replacement therapy).66,135 |

| Weight gain and metabolic disease | • Weight gain is possible following initiation of ART; INSTIs and TAF have been associated with increased weight gain in some people with HIV.73,103

• The long-term clinical significance of ART-induced weight gain remains unknown, although weight gain and obesity can increase the risk of metabolic disease. 136 |

• Counsel patients initiating ART or switching to INSTI- or TAF-based ART on the possibility of weight gain; encourage healthy lifestyle.

73

• Document and monitor weight and BMI. • Routinely screen for diabetes and cardiovascular risk. 73 |

| Oncology | • Compared with the general population, people with HIV are at increased risk of developing and dying from many non-AIDS-defining cancers.

137

• While many DDIs exist between ART and chemotherapy, some ARVs, such as INSTIs, have a lower propensity for DDIs with chemotherapy.114,138 • Complications of cancer or chemotherapy may result in challenges with ART administration (e.g., oral mucositis may result in swallowing difficulties). 138 |

• Optimize ART regimen to avoid DDIs with chemotherapy. • Prior to initiation of chemotherapy, review regimens for availability of liquid formulations or options for crushing/dissolving tablets in the event swallowing difficulties arise. |

| Transplant | • HIV is not a contraindication to solid organ transplant or bone marrow transplant, and there is growing experience in the management of people with HIV undergoing transplantation.139-141

• While many DDIs exist between ART and agents used in these settings, many of these DDIs can be avoided with use of INSTI-based ART.142-144 • Risk of infection should be carefully considered, with decisions on opportunistic infection prophylaxis and treatment informed by current HIV and transplant-specific guidance.143,144 |

• Review ART for DDIs with immunosuppressant therapy and other agents commonly used in these settings (e.g., azoles, chemotherapy for induction prior to bone marrow transplant). • Whenever possible, switch to INSTI-based ART to minimize risk of DDIs. 142 • Liaise with transplant pharmacist to coordinate monitoring plans and establish plans for managing DDIs for which there is minimal guiding literature (e.g., immunosuppressants with NNRTI- or PI-based ART. 142 |

| Chronic pain | • Chronic pain is highly prevalent among people with HIV and can be neuropathic and/or nociceptive in origin.113,145

• The etiology of neuropathic pain can include effects of the virus itself, effects of coinfections such as syphilis and past exposure to early antiretroviral medications.113,146 • Chronic pain among people with HIV causes negative impacts on quality of life and is linked to reduced ART adherence and engagement in care.113,145,146 |

• Facilitate referrals to multidisciplinary pain specialists, if and when available. • Reassure patients that the early ARVs associated with peripheral neuropathy (e.g., stavudine, didanosine, zalcitabine) are no longer marketed and that neuropathy associated with modern ART is rare. 146 • Encourage ART initiation and adherence to ART to prevent and treat HIV-associated peripheral neuropathy. 113 • Provide teaching on opioid overdoses and naloxone kits to people with HIV who are receiving opioids. |

| HBV coinfection | • Progression of liver-related disease and mortality is more rapid vs HBV monoinfection.

147

• ART should be effective for both HIV and HBV.53,148 • Tenofovir plus emtricitabine or lamivudine should be included in the regimen; the choice of TAF or TDF can be made based on renal function, bone health and cost. • Discontinuation of HBV treatment can lead to HBV reactivation and hepatocellular damage.53,148 • Even in the setting of HIV resistance, agents active against HBV should be continued for HBV suppression. 53 • Transaminase monitoring is necessary for HBV/HIV patients starting treatment due to the potential for IRIS following ART initiation and due to the increased risk of ART-related hepatotoxicity. |

• Screen and provide HBV immunization in susceptible people.

149

• Select ART that is effective for both HBV and HIV and prevent unintentional HBV treatment interruptions when ART is initiated or modified. • Manage DDIs, monitor treatment safety, adjust dosing in organ dysfunction, support medication adherence and facilitate drug access. • Recommend alternative HBV therapy (e.g., entecavir in addition to a complete ART regimen) when tenofovir (TDF or TAF) cannot be safely used. |

| HCV coinfection | • Risk of progression to cirrhosis or decompensated liver disease is 3 times greater among people with HIV/HCV coinfection vs HCV monoinfection.

150

• Selection of HCV treatment is based on liver disease staging, HCV genotype, treatment history DDIs, patient preference, renal function and cost. 151 • Most DAAs for HCV may be used with unboosted INSTIs and nonenzyme-inducing NNRTIs. Enzyme-inducing NNRTIs (e.g., efavirenz, etravirine, nevirapine) and agents boosted with cobicistat or ritonavir may interact with commonly used DAA regimens; if possible, ART should be switched to a noninteracting combination prior to initiating DAA treatment or a DAA compatible with ART should be selected. |

• Screen for active HCV infection in persons with HIV. • Select and monitor HCV treatment. • Manage DDIs. • Facilitate drug access. • Support medication adherence. • Promote harm reduction strategies to prevent reinfection. |

AE, adverse event; ART, antiretroviral therapy; ARV, antiretroviral; BMI, body mass index; CV, cardiovascular; DAA, directly acting antiviral; DDI, drug-drug interaction; HBV, hepatitis B virus; HCV, hepatitis C virus; INSTI, integrase inhibitor; IRIS, immune reconstitution inflammatory syndrome; MDMA3, 4-methylenedioxymethamphetamine (“ecstasy” or “molly”); MI, myocardial infarction; NNRTI, non-nucleoside reverse transcriptase inhibitor; OAT, opioid agonist therapy; PI, protease inhibitor; TAF, tenofovir alafenamide; TDF, tenofovir disoproxil fumarate.

Viral coinfections and emerging viral illnesses

With overlapping risk factors, viral hepatitis coinfections among people with HIV are prevalent in Canada.152,153 Clinical complications consist of cirrhosis, end-stage liver disease and hepatocellular carcinoma, and people with HIV and chronic viral hepatitis are at risk of more rapid progression to cirrhosis than those with either HBV or hepatitis C (HCV) monoinfection.154-156 Refer to Table 2 for the pharmacist’s role in the prevention, screening and treatment of viral hepatitis among people living with HIV.

Like HIV, emerging viral illnesses such as COVID-19 and monkey pox (mpox) have demonstrated the potential to infect anyone while disproportionately affecting certain populations.157,158 Pharmacists can contribute to public health efforts by learning from HIV language resources (Appendix 2) and communication toolkits 159 to promote antistigma messaging and counter the spread of misinformation. Pharmacists can provide recommendations on prevention and treatment strategies to people with HIV, who may be at increased risk of infection 73 or severe outcomes160-164 and who are more vulnerable to health service interruptions precipitated by emerging outbreaks.73,165 Pharmacists treating COVID-19 should be aware that nirmatrelvir/ritonavir can be coadministered with all ART and that specific resources exist to guide the management of DDIs involving ritonavir for COVID-19, which may differ from the context of ritonavir for HIV.166,167 Pharmacists treating mpox should be aware of DDIs involving ART and should consult HIV-specific DDI tools (Appendix 2) for recommendations for management.

Consideration for people with HIV who are aging

The population of people aging with HIV is increasing. While age itself does not appear to significantly affect the pharmacokinetics of most ARVs, 168 age-associated declines in renal or hepatic function may necessitate dose adjustment or ARV changes. Furthermore, polypharmacy for age-associated comorbidities is common in this population and may contribute to DDIs, AEs, suboptimal adherence, hospitalization and death. 169 To reduce DDI risk, pharmacists can consider switching to unboosted regimens and reduce polypharmacy by assisting with deprescribing, dose reduction or switching to safer alternatives. The use of prescribing tools combined with clinical judgment may help with deprescribing.170-172 Aging people with HIV may experience faster decline in cognitive function, mental health disorders and HIV-associated neurocognitive disorder, which are associated with reduced medication adherence and earlier death. 173 Pharmacists can facilitate adherence by simplifying ART and recommending adherence aids (see the “Strategies for supporting adherence and preventing resistance” section) and facilitate neurologist and/or mental health specialist referrals for these patients.

Changing ART

Switching or simplifying ART

Pharmacists can use their expertise to help guide ART changes in patients who are virally suppressed. Reasons to consider ART switches in virally suppressed patients include minimizing long-term AEs, decreasing pill burden, avoiding food requirements or DDIs, cost/coverage challenges, planning pregnancy and patient preference.53,174 Knowledge of first-line regimens, results of studies of suppressed individuals switching ART, newly marketed ART and prior ART/resistance history will aid in recommendations to modernize and tailor regimens without compromising viral suppression.

Use of long-acting ART

Long-acting ART (LA-ART) presents additional options for people with HIV. To date, the only complete LA-ART regimen available is cabotegravir/rilpivirine, indicated as switch therapy for virally suppressed patients and administered as intramuscular injections every 1 or 2 months, following an optional oral lead-in period. 175 In contrast, lenacapavir, a subcutaneous twice-yearly injection, is approved for use in combination with oral ARVs for people with multidrug-resistant HIV on failing ART.176,177 With multiple cabotegravir/rilpivirine dosing schedules available, 175 pharmacists should be aware that the potential for error is high. Pharmacists can help ensure patients understand the importance of resuming oral ART if cabotegravir/rilpivirine is discontinued175,178 and help patients access oral ART in the event of missed injections. 179 Although LA-ART avoids DDIs involving gastric acid suppression or cation chelation, 178 metabolic DDIs still exist. LA-ART also highlights the importance of using HIV-specific DDI tools and considering the route of administration, recognizing the latter can change throughout therapy. For instance, DDIs affecting oral absorption (e.g., cabotegravir and polyvalent cations or rilpivirine and proton pump inhibitors) must be taken into consideration during oral lead-in or oral bridging in anticipation of planned missed injections (e.g., for travel). 175

Management of treatment failure

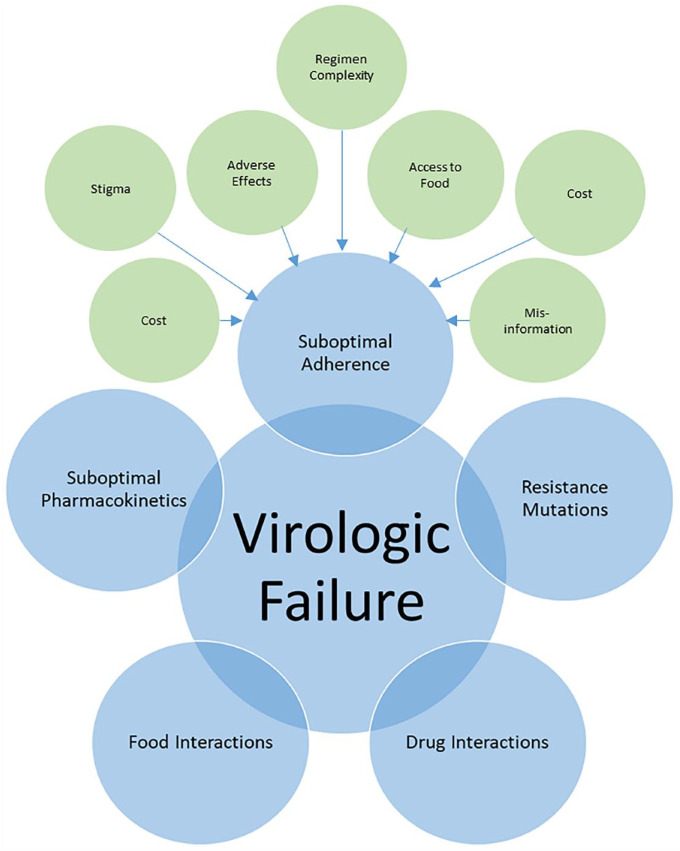

Virologic failure is defined as the inability to achieve or maintain viral suppression to HIV RNA <200 copies/mL. 53 Pharmacists can play an active role in determining causes of virologic failure and providing recommendations on management. Patients with viremia should be assessed for various contributing factors (Figure 2) and have their HIV viral load tests repeated. 53 In patients with HIV RNA ≥1000 copies/mL with no resistance mutations, the cause of viremia is likely suboptimal adherence. 53 In patients with low-level viremia (detectable HIV RNA below 200 copies/mL), pharmacists should routinely assess for and address factors contributing to virologic failure (Figure 2), but ART changes are not necessarily required. 53 Pharmacists can identify and provide support for adherence issues and are also skilled at identifying and managing complex DDIs (“Key populations” section) that may contribute to treatment failure.

Figure 2.

Factors associated with virologic failure

Prior to designing a new regimen, the patient’s ART history and cumulative drug resistance must be reviewed. Repeat viral load and genotype resistance testing may be advisable if there is incomplete viral suppression or viral rebound. 52 HIV pharmacists should be able to interpret resistance tests and provide appropriate recommendations, taking into account the complete ART history, limitations of genotypic drug resistance testing (e.g., if the resistance test was performed more than 4 weeks after discontinuing ART, some mutations may not be detected due to the absence of drug pressure) and the cumulative nature of drug resistance (e.g., once a mutation is detected, it should be considered present indefinitely). 53 See Appendix 2 for useful resources. Pharmacists can ensure regimens contain at least 2 fully active agents if at least 1 has a high barrier to resistance (e.g., dolutegravir, boosted darunavir) or otherwise 3 fully active ARVs. 53 In patients with certain resistance mutations, pharmacists can help with dose optimization to achieve drug concentrations necessary to be fully active against a less-sensitive virus (e.g., twice-daily dolutegravir or ritonavir-boosted darunavir).53,180

Although rare, some patients develop extensive drug resistance. Achieving maximal viral suppression should still be the goal. However, if unachievable, the goals of ART should be to preserve immunologic function, delay clinical progression and minimize further development of resistance mutations. In patients with ongoing viremia and limited treatment options, pharmacists can review patients for novel or investigational agents and assist with obtaining access through expanded access programs or studies.

Therapeutic drug monitoring

Although not routinely recommended, ARV therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) may be useful in certain patient populations (e.g., pediatric, pregnant) or clinical situations (e.g., virologic failure, complex DDIs, suspected malabsorption).180-184 Some Canadian laboratories offer ARV TDM services (Quebec Antiretroviral Therapeutic Drug Monitoring Program, 185 BC Centre for Excellence in HIV 186 ). Pharmacists can identify patients who may benefit from TDM and facilitate the request by ensuring that instructions are accurately followed (e.g., timing of drug measurements, handling of samples) and including relevant clinical information needed for analysis (e.g., resistance and treatment history, concurrent medications). 181 Pharmacists should collaborate with providers and patients to make final decisions on treatment changes and repeat the analysis to confirm the outcome of the intervention. Note that the delay in receiving TDM results can make timely dose adjustments difficult.

Managing transitions of care

It is critical to review medications and ensure continuity at transitions of care, which can include the movement between ambulatory care and hospital, between hospital wards or hospitals, from pediatric to adult clinics, between provinces, between HIV care providers, from independent living to long-term care, and to incarceration. Pharmacists can assist with care transitions by providing a complete list of medications to be continued and discontinued, administration instructions and a continuous supply of medication to prevent treatment interruptions.

The transition from pediatric to adult care for people with HIV can be challenging for both patients and health care providers. Patients with perinatally acquired HIV often have a change in HIV care providers, clinic location and expectations of their new adult health team. Pharmacists can ease the transition by assisting with drug coverage, providing age-appropriate ARV education and strategies to maintain adherence as they become more independent in managing medications and their health.

Scholarly and professional activities

Pharmacists have roles beyond the HIV cascade of prevention and care. The Canadian HIV and Viral Hepatitis Pharmacists Network (CHAP) was founded in 1997 to bring together pharmacists with clinical and research interest in HIV and/or viral hepatitis to optimize patient outcomes and foster professional development through communication, clinical practice, education and research. Members meet annually, communicate regularly via e-mail and collaborate on projects and publications. 187 There are currently more than 160 members across Canada and worldwide.

Pharmacists are routinely involved in providing drug information to patients and health care providers. Medication pamphlets can facilitate patient understanding and medication adherence. Pocket guides and resources 188 can support clinicians in optimizing care for people with HIV. Online resources such as the HIV/HCV Medication Guide 189 and the HIV/HCV Drug Therapy Guide website 135 and mobile app, created and regularly updated by pharmacists, provide comprehensive data on HIV and HCV drug therapy with a focus on identifying and managing DDIs. Pharmacists can also collaborate with other clinicians in developing local or national guidelines for the treatment and prevention of HIV and coinfections.27,29,190 Pharmacists are key players in the delivery of antiretroviral stewardship programs (ARVSPs) that focus on the mitigation of ARV and OI medication errors in hospitalized patients by examining incomplete/incorrect medication regimens, incorrect doses, improper administration and major DDIs.191,192 A 2020 Joint Policy Paper by the Infectious Diseases Society of America, the HIV Medicine Association and the American Academy of HIV Medicine highlights how ARVSPs can optimize regimens, prevent ARV resistance and improve overall inpatient outcomes. 193 Key components of ARVSPs include audits, order set development, formulary reviews, and follow a structured framework for patient care delivery.

HIV pharmacists play an important role in pharmacy student education through teaching, mentoring and supervising practice-based rotations. Several accredited pharmacy residency programs across Canada offer HIV elective rotations for year 1 residents. An accredited year 2 HIV pharmacy residency offers further training for those wishing to develop advanced HIV patient care skills.194,195 Since 2011, HIV pharmacist credentialling has been available for pharmacists working in HIV through the American Academy of HIV Medicine. 196 To meet the learning needs of practising pharmacists, the Canadian HIV And Viral Hepatitis Pharmacists (CHAP) Network launched a national observership program in 2017 to increase confidence in HIV pharmacotherapy, enhance awareness of different practice sites and subspecialties and promote professional collaboration. Observers are paired with a local preceptor to build relationships for future collaboration and networking. 197

Furthermore, pharmacists often provide interprofessional education on HIV pharmacotherapy. In 2013, the St. Michael’s Hospital Positive Care Clinic in Toronto implemented a month-long, immersive, pharmacist-led teaching rotation for medical residents to acquire enhanced skills in HIV care. Now offered annually, the rotation’s overarching concept is for the medical trainee to “become the pharmacist”, learning to recognize, prevent and manage common drug therapy issues in people with HIV. 198 Pharmacist-led didactic and case-based teaching is provided to medical residents and infectious disease fellows at universities across Canada as part of their HIV rotations.

Lastly, many research opportunities exist for pharmacists, including writing case reports of rare or serious adverse drug reactions or novel DDIs; conducting cross-sectional surveys or reviews on prescribing practices; studying health economics, drug policy development and pharmacoepidemiology; conducting studies on DDIs, pharmacokinetics/pharmacogenomics, TDM and pharmacovigilance; and participating in practice-based studies such as pharmacist-led testing for HIV and sexually transmissible and blood-borne infections, prescribing for PrEP, and other ways to improve access to and quality of care. These activities ultimately advance the profession of pharmacy and improve patient care.

Conclusion

Pharmacists have an integral role in every stage of the HIV cascade of care. From PrEP and PEP to pharmacist-based HIV testing programs, pharmacists can assist with prevention, diagnosis and linkage to care. For people with HIV, pharmacists are key players in ART initiation and tailoring therapy to meet patients’ individual needs. Through careful monitoring, pharmacists can adjust ART to achieve and maintain viral suppression. Finally, through engagement in professional activities, pharmacists contribute to the evolution of HIV management and shape the future of the HIV pharmacist in Canada. ■

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-pdf-1-cph-10.1177_17151635241267350 for Role of the pharmacist caring for people at risk of or living with HIV in Canada by Stacey Tkachuk, Erin Ready, Shanna Chan, Jennifer Hawkes, Tracy Janzen Cheney, Jeff Kapler, Denise Kreutzwiser, Linda Akagi, Michael Coombs, Pierre Giguere, Christine Hughes, Deborah Kelly, Sheri Livingston, Dominic Martel, Mark Naccarato, Salin Nhean, Carley Pozniak, Tasha Ramsey, Linda Robinson, Jonathan Smith, Jaris Swidrovich, Jodi Symes, Deborah Yoong and Alice Tseng in Canadian Pharmacists Journal / Revue des Pharmaciens du Canada

Footnotes

Author Contributions: E. Ready, S. Tkachuk and A. Tseng initiated and supervised the project; J. Hawkes and T. Janzen Cheney led the writing of section 1; J. Kapler led the writing of section 2; S. Chan led the writing of section 3; and D. Kreutzwiser led the writing of section 4. All authors participated in developing the concept and design and in writing and/or reviewing the manuscript.

Tracy Jansen Cheney: advisory board work for Gilead; Pierre Giguere: speaking honoraria and/or advisory board work for ViiV, Gilead, Merck, Pfizer; Deborah Kelly: speaking honoraria and/or advisory board work for ViiV, Gilead, Moderna; Dominic Martel: speaking honoraria and/or advisory board work for AbbVie, Gilead, Paladin and Pfizer; Carley Pozniak: speaking honoraria and advisory board work for Viiv, Gilead, Merck; Linda Robinson: speaker/educational honoraria, ViiV, Gilead, Merck; Jonathan Smith: advisory board work for ViiV; Alice Tseng: speaking honoraria and/or advisory board work for ViiV, Gilead, Merck, Pfizer.

Funding: The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iDs: Stacey Tkachuk  https://orcid.org/0009-0000-7110-8578

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-7110-8578

Erin Ready  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9030-3595

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9030-3595

Deborah Kelly  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3114-8123

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3114-8123

Supplemental Material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

Contributor Information

Stacey Tkachuk, Women and Children’s Health Centre of British Columbia, Provincial Health Services Authority, Vancouver, British Columbia; UBC Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Vancouver, British Columbia.

Erin Ready, UBC Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Vancouver, British Columbia; St. Paul’s Hospital Ambulatory Pharmacy, Providence Health Care, Vancouver, British Columbia.

Shanna Chan, Winnipeg Regional Health Authority Regional Pharmacy Program, Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Jennifer Hawkes, UBC Faculty of Pharmaceutical Sciences, Vancouver, British Columbia; University Hospital of Northern BC, Northern Health, Prince George, British Columbia.

Tracy Janzen Cheney, Winnipeg Regional Health Authority Regional Pharmacy Program, Winnipeg, Manitoba.

Jeff Kapler, Southern Alberta Clinic, Alberta Health Services, Calgary, Alberta.

Denise Kreutzwiser, St. Joseph’s Health Care London, London, Ontario.

Linda Akagi, St. Paul’s Hospital Ambulatory Pharmacy, Providence Health Care, Vancouver, British Columbia; British Columbia Centre for Excellence in HIV/AIDS, Vancouver, British Columbia.

Michael Coombs, School of Pharmacy, Memorial University, St. John’s, Newfoundland.

Pierre Giguere, Pharmacy Department, The Ottawa Hospital, Ottawa, Ontario; Ottawa Hospital Research Institute, Ottawa, Ontario; School of Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Ottawa, Ottawa, Ontario.

Christine Hughes, Faculty of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Alberta.

Deborah Kelly, School of Pharmacy, Memorial University, St. John’s, Newfoundland.

Sheri Livingston, Tecumseh Byng Program, Windsor Regional Hospital, Windsor, Ontario.

Dominic Martel, Pharmacy Department, Centre hospitalier de l’Université de Montréal (CHUM), Montreal, Quebec; Centre de recherche du CHUM (CRCHUM), Montreal, Quebec.

Mark Naccarato, Henry Ford Hospital, Detroit, Michigan, USA.

Salin Nhean, Luminis Health Doctors Community Medical Center, Lanham, Maryland, USA.

Carley Pozniak, Positive Living Program, Royal University Hospital, Saskatoon, Saskatchewan.

Tasha Ramsey, Pharmacy Department, Nova Scotia Health Authority, Halifax, Nova Scotia; College of Pharmacy, Faculty of Health, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia.

Linda Robinson, Windsor Regional Hospital, Windsor, Ontario.

Jonathan Smith, Casey House, Toronto, Ontario.

Jaris Swidrovich, Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

Jodi Symes, Pharmacy Department, Saint John Regional Hospital, Horizon Health Network, Saint John, New Brunswick.

Deborah Yoong, St. Michael’s Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, Toronto, Ontario.

Alice Tseng, Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario; Toronto General Hospital, University Health Network, Toronto, Ontario.

References

- 1. Samji H, Cescon A, Hogg RS, et al. Closing the gap: increases in life expectancy among treated HIV-positive individuals in the United States and Canada. PLoS One 2013;8(12):e81355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Marcus JL, Leyden WA, Alexeeff SE, et al. Comparison of overall and comorbidity-free life expectancy between insured adults with and without HIV infection, 2000-2016. JAMA Netw Open 2020;3(6):e207954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Gueler A, Moser A, Calmy A, et al. Life expectancy in HIV-positive persons in Switzerland: matched comparison with general population. AIDS 2017;31(3):427-36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schouten J, Wit FW, Stolte IG, et al. Cross-sectional comparison of the prevalence of age-associated comorbidities and their risk factors between HIV-infected and uninfected individuals: the AGEhIV cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2014;59(12):1787-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Brunetta JM, Baril JG, de Wet JJ, et al. Cross-sectional comparison of age- and gender-related comorbidities in people living with HIV in Canada. Medicine 2022;101(28):e29850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Davy-Mendez T, Napravnik S, Hogan BC, et al. Hospitalization rates and causes among persons with HIV in the United States and Canada, 2005–2015. J Infect Dis 2021;223(12):2113-23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Nozza S, Timelli L, Saracino A, et al. Decrease in incidence rate of hospitalizations due to AIDS-defining conditions but not to non-AIDS conditions in PLWHIV on cART in 2008–2018 in Italy. J Clin Med 2021;10(15):3391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kendall CE, Shoemaker ES, Boucher L, et al. The organizational attributes of HIV care delivery models in Canada: a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2018;13(6):e0199395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Tseng A, Foisy M, Hughes CA, et al. Role of the pharmacist in caring for patients with HIV/AIDS: clinical practice guidelines. Can J Hosp Pharm 2012;65(2):125-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Horn T, Thompson MA. The state of engagement in HIV care in the United States: from cascade to continuum to control. Clin Infect Dis 2013;57(8):1164-71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis 2011;52(6):793-800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Haber N, Pillay D, Porter K, Bärnighausen T. Constructing the cascade of HIV care: methods for measurement. Curr Opin HIV AIDS 2016;11(1):102-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ehrenkranz P, Rosen S, Boulle A, et al. The revolving door of HIV care: revising the service delivery cascade to achieve the UNAIDS 95-95-95 goals. PLoS Med 2021;18(5):e1003651. Available: https://journals.plos.org/plosmedicine/article?id=10.1371/journal.pmed.1003651 (accessed Feb. 2, 2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. HIV.gov. HIV care continuum. 2022. Available: https://www.hiv.gov/federal-response/policies-issues/hiv-aids-care-continuum (accessed Jan. 16, 2023).

- 15. National Center for Disease Control Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention. Understanding the HIV care continuum. 2019. Available: https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pdf/library/factsheets/ (accessed Jan. 16, 2023).

- 16. Schaefer R, Gregson S, Fearon E, Hensen B, Hallett TB, Hargreaves JR. HIV prevention cascades: a unifying framework to replicate the successes of treatment cascades. Lancet HIV 2019;6(1):e60-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nunn AS, Brinkley-Rubinstein L, Oldenburg CE, et al. Defining the HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis care continuum. AIDS. 2017;31(5):731-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Kelley CF, Kahle E, Siegler A, et al. Applying a PrEP continuum of care for men who have sex with men in Atlanta, Georgia. Clin Infect Dis 2015;61(10):1590-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Jin H, Biello KB, Garofalo R, et al. HIV treatment cascade and PrEP care continuum among serodiscordant male couples in the United States. AIDS Behav 2021;25(11):3563-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Canada.ca. Estimates of HIV incidence, prevalence and Canada’s progress on meeting the 90-90-90 HIV targets. 2020. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/publications/diseases-conditions/summary-estimates-hiv-incidence-prevalence-canadas-progress-90-90-90.html (accessed Jan. 16, 2023).

- 21. HIV.gov. HIV treatment as prevention: TASP prevention of HIV/AIDS. 2023. Available: https://www.hiv.gov/tasp/ (accessed Jun. 20, 2023).

- 22. HIV Legal Network. HIV criminalization in Canada: Key Trends and Patterns (1989-2020). 2022. Available: https://www.hivlegalnetwork.ca/site/hiv-criminalization-in-canada-key-trends-and-patterns-1989-2020/?lang=en (accessed Feb. 2, 2023).

- 23. Goodin A, Fallin-Bennett A, Green T, Freeman PR. Pharmacists’ role in harm reduction: a survey assessment of Kentucky community pharmacists’ willingness to participate in syringe/needle exchange. Harm Reduct J 2018;15(1):4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Janulis P. Pharmacy nonprescription syringe distribution and HIV/AIDS: a review. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2012;52(6):787-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Matheson C, Bond CM, Tinelli M. Community pharmacy harm reduction services for drug misusers: national service delivery and professional attitude development over a decade in Scotland. J Public Health (Oxf) 2007;29(4):350-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. McCree DH, Byrd KK, Johnston M, Gaines M, Weidle PJ. Roles for pharmacists in the “ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for America” initiative. Public Health Rep 2020;135(5):547-54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hughes C, Yoong D, Giguère P, Hull M, Tan DHS. Canadian guideline on HIV preexposure prophylaxis and nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis for pharmacists. Can Pharm J (Ott) 2019;152(2):81-91. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30886661/ (accessed Apr. 11, 2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Crawford ND, Myers S, Young H, Klepser D, Tung E. The role of pharmacies in the HIV prevention and care continuums: a systematic review. AIDS Behav 2021;25(6):1819-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tan DHS, Hull MW, Yoong D, et al. Canadian guideline on HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis and nonoccupational postexposure prophylaxis. Can Med Assoc J 2017;189(47):E1448-58. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Baldwin A, Light B, Allison WE. Pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV infection in cisgender and transgender women in the U.S.: a narrative review of the literature. Arch Sex Behav 2021;50(4):1713-28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Owens DK, Davidson KW, Krist AH, et al. Preexposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV infection: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA 2019;321(22):2203-13. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31184747/ (accessed Jan. 16, 2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Panel on Treatment of Pregnant Women with HIV Infection and Prevention of Perinatal Transmission. Recommendations for use of antiretroviral drugs during pregnancy and interventions to reduce perinatal HIV transmission in the United States. Department of Health and Human Services; 2023. Available: https://clinicalinfo.hiv.gov/en/guidelines (accessed Jun. 20, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 33. Connor EM, Sperling RS, Gelber R, et al. Reduction of maternal-infant transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 with zidovudine treatment. Pediatric AIDS Clinical Trials Group Protocol 076 Study Group. N Engl J Med 1994;331(18):1173-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Canada.ca. Human immunodeficiency virus - HIV screening and testing guide. 2014. Available: https://www.canada.ca/en/public-health/services/hiv-aids/hiv-screening-testing-guide.html#c1 (accessed Jan. 16, 2023).

- 35. CATIE - Canada’s source for HIV and hepatitis C information. National HIV Testing Day. 2016. Available: https://www.catie.ca/national-hiv-testing-day-0 (accessed Aug. 17, 2023).

- 36. Kelly DV, Kielly J, Hughes C, et al. Expanding access to HIV testing through Canadian community pharmacies: findings from the APPROACH study. BMC Public Health 2020;20(1):639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Darin KM, Klepser ME, Klepser DE, et al. Pharmacist-provided rapid HIV testing in two community pharmacies. J Am Pharm Assoc 2015;55(1):81-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. CATIE - Canada’s source for HIV and hepatitis C information. HIV self-testing. 2023. Available: https://www.catie.ca/hiv-self-testing-0 (accessed Jan. 16, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 39. CATIE - Canada’s source for HIV and hepatitis C information. HIV testing technologies. 2022. Available: https://www.catie.ca/hiv-testing-technologies (accessed Jan. 16, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 40. Young J, Ablona A, Klassen BJ, et al. Implementing community-based dried blood spot (DBS) testing for HIV and hepatitis C: a qualitative analysis of key facilitators and ongoing challenges. BMC Public Health 2022;22(1):1085. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/35642034/ (accessed Jan. 16, 2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Cernasev A, Kodidela S, Veve MP, Cory T, Jasmin H, Kumar S. A narrative systematic literature review: a focus on qualitative studies on HIV and medication-assisted therapy in the United States. Pharmacy (Basel) 2021;9(1):67. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33806974/ (accessed Jan. 16, 2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Tucker CM, Marsiske M, Rice KG, Nielson JJ, Herman K. Patient-centered culturally sensitive health care: model testing and refinement. Health Psychol 2011;30(3):342-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Abboah-Offei M, Bristowe K, Harding R. Are patient outcomes improved by models of professionally-led community HIV management which aim to be person-centred? A systematic review of the evidence. AIDS Care 2021;33(9):1107-17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Chinyandura C, Jiyane A, Tsalong X, Struthers HE, McIntyre JA, Rees K. Supporting retention in HIV care through a holistic, patient-centred approach: a qualitative evaluation. BMC Psychol 2022;10(1):17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Schilder AJ, Kennedy C, Goldstone IL, Ogden RD, Hogg RS, O’Shaughnessy MV. “Being dealt with as a whole person.” Care seeking and adherence: the benefits of culturally competent care. Soc Sci Med 2001;52(11):1643-59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Schafer JJ, Gill TK, Sherman EM, McNicholl IR. ASHP guidelines on pharmacist involvement in HIV care. Am J Health Syst Pharm 2016;73(7):468-94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Ahmed A, Saqlain M, Tanveer M, Blebil AQ, Dujaili JA, Hasan SS. The impact of clinical pharmacist services on patient health outcomes in Pakistan: a systematic review. BMC Health Serv Res 2021;21(1):859. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34425816/ (accessed Jan. 16, 2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Hill LA, Ballard C, Cachay ER. The role of the clinical pharmacist in the management of people living with HIV in the modern antiretroviral era. AIDS Rev 2019;21(4):195-210. Available: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31834321/ (accessed Jan. 16, 2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Bahall M. Prevalence, patterns, and perceived value of complementary and alternative medicine among HIV patients: a descriptive study. BMC Complement Altern Med 2017;17(1):422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]