Abstract

Background:

Several acellular dermal matrices (ADMs) are used for soft-tissue support in prosthetic breast reconstruction. Little high-level evidence supports the use of one ADM over another. The authors sought to compare Cortiva 1-mm Allograft Dermis with AlloDerm RTU (ready to use), the most studied ADM in the literature.

Methods:

A single-blinded randomized controlled trial comparing Cortiva with AlloDerm in prepectoral and subpectoral immediate prosthetic breast reconstruction was performed at 2 academic hospitals from March of 2017 to December of 2021. Reconstructions were direct to implant (DTI) or tissue expander (TE). Primary outcome was reconstructive failure, defined as TE explantation before planned further reconstruction, or explantation of DTI reconstructions before 3 months postoperatively. Secondary outcomes were additional complications, patient-reported outcomes (PROs), and cost.

Results:

There were 302 patients included: 151 AlloDerm (280 breasts), 151 Cortiva (277 breasts). The majority of reconstructions in both cohorts consisted of TE (62% versus 38% DTI), smooth device (68% versus 32% textured), and prepectoral (80% versus 20% subpectoral). Reconstructive failure was no different between ADMs (AlloDerm 9.3% versus Cortiva 8.3%; P = 0.68). There were no additional differences in any complications or PROs between ADMs. Seromas occurred in 7.6% of Cortiva but 12% of AlloDerm cases, in which the odds of seroma formation were two-fold higher (odds ratio, 1.93 [95% CI, 1.01 to 3.67]; P = 0.047). AlloDerm variable cost was 10% to 15% more than Cortiva, and there were no additional cost differences.

Conclusion:

When assessing safety, clinical performance, PROs, and cost, Cortiva is noninferior to AlloDerm in immediate prosthetic breast reconstruction, and may be less expensive, with lower risk of seroma formation.

CLINICAL QUESTION/LEVEL OF EVIDENCE:

Therapeutic, I.

In 2022, 287,850 women in the United States were diagnosed with invasive breast cancer, and 51,400 with ductal carcinoma in situ.1 In 2020, members of the American Society of Plastic Surgeons performed 137,808 breast reconstructions, with 105,665 in the immediate setting. These reconstructions used a tissue expander (TE) in 83,487 cases and an acellular dermal matrix (ADM) 59,247 times, with bilateral reconstructions outpacing unilateral at a ratio of 2:1.2 Breast reconstructions are common, and tend to involve a prosthesis in the immediate setting with an ADM.3,4 Initially, ADMs were used as a sling to extend the subpectoral pocket caudally, limit resistive forces to lower pole expansion of immediate implants, and define infralateral and lateral mammary folds.5 Compared with total submuscular coverage, partial submuscular coverage supplemented with ADM is associated with greater initial TE fill volumes, fewer postoperative TE fill visits, and higher likelihood of direct-to-implant (DTI) reconstruction.6–8 The concepts of improved aesthetic and patient-reported outcomes (PROs) with less postoperative pain when using an ADM has not been proven, however, and some reports suggest that ADMs can increase the risk of seroma, infection, skin necrosis, and reconstructive failure.6,9–19 Furthermore, ADM used for lower pole support after partial submuscular coverage does not mitigate the risk of animation deformity or pectoralis major muscle fibrosis after radiotherapy. Prepectoral reconstruction with full anterior implant coverage with ADM in TE or DTI reconstruction has gained popularity.20,21

When considering breast reconstruction, the shared decision-making process should be informed by risk exposure and optimized for preference concordance.22 The decision to use a particular ADM can be considered in this context and then weighed against cost. Risk factors associated with prosthetic breast reconstruction complications include immediate reconstruction, bilateral procedures, radiation, elevated body mass index (BMI), and smoking.10,13,23–33 Whether ADM type influences complication rates or PROs remains unclear. In most studies, the particular ADM chosen does not significantly influence complication rates.18,34–50 A higher infection rate with FlexHD than AlloDerm,51 more seromas with AlloDerm than Surgimend,52 and higher total complications driven by higher seroma rate with AlloDerm than Strattice53 represent the conspicuous exceptions not corroborated by other studies. Moreover, no significant differences in PROs have been shown when comparing ADMs.37,42,54,55

Selection of approach to postmastectomy breast reconstruction is the culmination of a series of choices, including whether to operate at all, mastectomy type, reconstruction timing, and whether to perform autologous or implant-based reconstruction. Once the decision to proceed with TE or DTI in the subpectoral or prepectoral plane is made, the surgeon must still choose a particular implant and surgical approach for device support. If the best available evidence, however, suggests that one device or ADM is not statistically significantly inferior to another in terms of safety, clinical performance, or PROs, then cost becomes a relevant factor. This study used a noninferiority design to compare the performance of Cortiva with AlloDerm in prepectoral and subpectoral breast reconstructions, focusing on TEs and DTIs, with respect to the primary outcome of reconstructive failure.

METHODS

Study Design

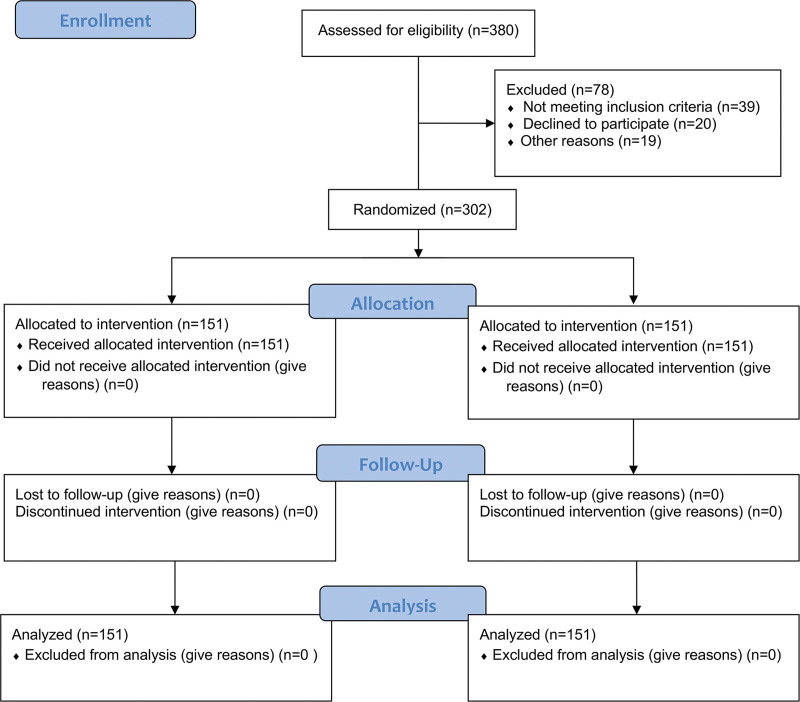

We performed a randomized controlled trial (Fig. 1) comparing 2 ADMs in immediate postmastectomy prosthetic breast reconstruction: Cortiva 1 mm Allograft Dermis, 1.0±0.2 mm (RTI Surgical) and AlloDerm RTU (ready to use), 1.6±0.4 mm (Allergan Medical). All ADMs had a single-sided, nonpreperforated basement membrane that was fenestrated by the plastic surgeon. Patients were blinded to ADM manufacturer. Reconstructions were performed at 2 sites (Barnes Jewish West County and Barnes Jewish Hospital) by 2 plastic surgeons (T.M.M. and M.M.T.) from March of 2017 to December of 2021. Patients were randomized using SAS PROC PLAN in a block size of 4 to 1 of the 2 ADMs. This study was approved by the Washington University Human Research and Protection Office (approval no. 201608168) and registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02891759).

Fig. 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials diagram. Existing data did not inform how prepectoral reconstruction would influence outcomes, so we amended the trial protocol to recruit an additional 180 patients for prepectoral reconstruction beyond those recruited for the subpectoral approach. No additional patients chose subpectoral reconstruction once prepectoral was offered, despite keeping the trial open for an additional year to optimize recruitment. Furthermore, no patient who selected prepectoral reconstruction was converted to a postpectoral approach for clinical reasons. Based on these trends, we continued overall trial enrollment to 302 patients (n = 61 subpectoral, n = 241 prepectoral). The research coordinator screened and enrolled all patients, who were blinded to the intervention; performed block randomization; notified surgeons which ADM would be used for each patient, disclosed in sealed envelopes; coordinated follow-up; administered the BREAST-Q to measure PROs; and ensured study protocol compliance.

TEs were used until planned secondary reconstructive procedure or reconstructive failure. DTI reconstructions were followed up for a minimum of 3 months postoperatively or until reconstructive failure. Time to drain removal was recorded for all breasts, including 2 drains for subpectoral and 1 drain for prepectoral.

Enrollment

All patients undergoing immediate breast reconstruction with subpectoral TE or DTI and lower pole support with ADM were considered for eligibility starting in February of 2017. The option for prepectoral reconstruction with full anterior coverage of the TE or implant was introduced in September of 2018. Patients with a BMI under 36 kg/m2, ages 22 to 70 years, undergoing prophylactic or therapeutic, nipple- or skin-sparing, unilateral or bilateral mastectomies were included.

Surgical Procedures

Patient preference drove the decision to proceed with subpectoral versus prepectoral reconstruction, and the decision to use saline versus silicone gel–filled devices where relevant. The decision to proceed with a TE or DTI and initial volumes was based on clinical assessment of perfusion, but never indocyanine green or associated devices. For subpectoral placement, the pectoralis major muscle was caudally detached and sutured with 2-0 polydioxanone suture to the cephalad edge of a 16 × 8-cm sheet of oriented ADM, and anchored to the chest wall to define the lateral and inframammary folds. For prepectoral placement, oriented ADM was secured to the chest wall muscles with 2-0 polydioxanone suture with sufficient redundancy to accommodate an implant or fully inflated TE. Two drains—1 deep (10 Fr) and 1 superficial (15 Fr) to the pectoralis major—were used for subpectoral reconstructions, and 1 subcutaneous drain (15 Fr) accompanied all prepectoral reconstructions. Only saline irrigation was used. Each breast received a 15-cc PEC II nerve block with 0.25% Marcaine and 1:200,000 epinephrine by the plastic surgeon and a standardized enhanced recovery after surgery protocol. All implanted breast prostheses from July of 2019 onward had smooth surfaces due to the U.S. Food and Drug Administration recall of Allergan macrotextured breast TEs and implants.56 Only tabbed TEs were used once we switched to smooth devices, before which TEs did not have tabs.

Outcomes

Clinical, patient-reported, and cost outcomes were prospectively recorded in REDCap version 7.57,58 The primary outcome was reconstructive failure, defined as unplanned, premature TE or implant explantation for any reason. Infection requiring reinstitution of oral or intravenous antibiotics or reoperation, seroma or hematoma identified by imaging or requiring intervention, necrosis or incisional dehiscence requiring intervention, TE or implant exposure, and time to final drain removal represented secondary outcomes. Analgesia use 2 and 4 weeks postoperatively was also collected. PROs were reported as Q scores generated by BREAST-Q version 1.1.

Variable costs, excluding the cost of the ADM, were compiled for all patients. These are patient-specific costs that the hospital incurs (eg, operative staff salaries, supplies, drugs, laboratory tests, imaging, and so on). Surgeon reimbursement and fixed costs, such as overhead and administrative salaries, were excluded. Our institution is contractually prohibited from disclosing exact costs for discrete products, such as ADMs. Rather, we can present ranges of $28 to $31/cm2 for AlloDerm RTU (ie, 128 cm2: $3584 to $3968; 320 cm2: $8960 to $9920) and $23 to $26/cm2 for Cortiva (ie, 128 cm2: $2944 to $3328; 320 cm2: $7360 to $8320), which was 10% to 15% less expensive during the study period.

Sample Size Calculation

Sample size determination assumed a reconstructive failure rate of 20% in 1 cohort and 9% in another group based on outcomes from more than 2000 of our previous reconstructions.26,35,59 A total of 180 eligible patients were determined to be required to achieve 80% power based on the 1-sided Z test with pooled variance to detect a difference between the incidence rates of the 2 ADMs at 0.1 significance. Interim analysis did not alter enrollment strategy.60 The trial was initially designed for subpectoral reconstruction, but our practices reflected a strong national switch to prepectoral reconstruction 1 year into the trial (Fig. 1).

Statistical Analyses

Chi-square and Fisher exact tests were used for categorical variables to detect differences in reconstructive failure rate between ADM types. The nonparametric Wilcoxon rank sum test was used for ranked BREAST-Q data and continuous variables that were not normally distributed. Multivariable logistic regression models were performed to assess the effect of ADM type, controlling for prepectoral versus subpectoral plane, and significant factors found in univariate analysis. Stepwise selection was applied with a P value threshold of 0.2. The 95% confidence interval for the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve was 0.773 (0.695 to 0.851) for reconstructive failure and 0.784 (0.696 to 0.872) for the logistic regression model for seroma formation, indicating acceptable model fits. A significance of α = 0.05 was used, and all tests were 2-sided. Missing data were considered missing at random and excluded. SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute) was used for analyses.

RESULTS

Patient Demographic and Cancer Characteristics

A total of 302 patients (557 breasts) were enrolled and completed the study: 151 patients (280 breasts) were randomized to AlloDerm and 151 patients (277 breasts) to Cortiva. There were no significant differences in age, race, BMI, diabetes, or smoking status (Table 1). Hypertension was more prevalent in the AlloDerm cohort (25% versus 15% in the Cortiva cohort; P = 0.04).

Table 1.

Patient-Level Demographic Characteristics and Comorbidities

| Variable | AlloDerm RTU (n = 151) | Cortiva 1 mm (n = 151) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| No. of breasts, total | 280 | 277 | — |

| Age, median (IQR), yr | 47.2 (38.7, 53.5) | 48.2 (40.6, 55.4) | 0.23 |

| Race, no. (%) | 0.43 | ||

| White | 139 (92) | 142 (95) | |

| Black | 9 (6.0) | 7 (4.7) | |

| Asian | 2 (1.3) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Other | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0.0) | |

| BMI, median (IQR) | 26.7 (23.0, 30.1) | 26.5 (23.3, 30.6) | >0.99 |

| Diabetes, no. (%) | 9 (6.0) | 7 (4.6) | 0.61 |

| Hypertension, no. (%) | 37 (25) | 23 (15) | 0.04a |

| Autoimmune disease, no. (%) | 10 (6.6) | 12 (8.0) | 0.66 |

| Smoking, no. (%) | 0.16 | ||

| Never smoker | 107 (71) | 101 (67) | |

| Former smoker | 29 (19) | 41 (27) | |

| Current smoker | 15 (9.9) | 9 (6.0) | |

| Neoadjuvant chemotherapy, no. (%) | 36 (24) | 43 (28) | 0.36 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy, no. (%) | 35 (23) | 36 (24) | 0.89 |

| Immunotherapy, no. (%) | 25 (17) | 22 (15) | 0.63 |

BMI, body mass index; RTU, ready to use.

Statistically significant.

Cancer characteristics and treatment variables are displayed in Table 2. Most mastectomies in both cohorts were prophylactic (54% in AlloDerm versus 52% in Cortiva), and there were no significant differences in cancer stage in the treated breasts (P = 0.07). Use of radiation, chemotherapy, immunotherapy, and sentinel lymph node biopsy did not differ across groups, and resected mastectomy specimen weights were similar (median: 561 [interquartile range {IQR}: 386, 738] grams AlloDerm versus median: 582 [IQR: 370, 813] grams Cortiva; P = 0.27).

Table 2.

Breast-Level Cancer Characteristics and Treatment

| Variable | AlloDerm RTU (n = 280) | Cortiva 1 mm (n = 277) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cancer stage, no. (%) | 0.07 | ||

| Prophylactic | 152 (54) | 145 (52) | |

| DCIS | 24 (8.6) | 34 (12) | |

| I | 52 (19) | 37 (13) | |

| II | 47 (17) | 47 (17) | |

| III | 5 (1.8) | 14 (5.1) | |

| Previous radiation therapy, no. (%) | 6 (2.1) | 2 (0.7) | 0.29 |

| Adjuvant radiation therapy, no. (%) | 40 (14) | 43 (16) | 0.68 |

| Mastectomy type, no. (%) | 0.07 | ||

| Nipple-sparing | 142 (51) | 119 (43) | |

| Skin-sparing | 138 (49) | 158 (57) | |

| SLNB, no. (%) | 140 (50) | 128 (46) | 0.37 |

| Mastectomy specimen weight, median (IQR), g | 561 (386, 738) | 582 (370, 813) | 0.27 |

DCIS, ductal carcinoma in situ; RTU, ready to use; SLNB, sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Breast Reconstruction Characteristics

Most breasts were reconstructed using TEs (Table 3), although a large minority of patients underwent DTI reconstruction in both groups (38% AlloDerm versus 37% Cortiva; P = 0.65). Of patients who initially received TEs, the most common second-stage reconstruction was with implants alone (59% of TEs in AlloDerm versus 62% of TEs in Cortiva; P = 0.50), with a smooth surface (68% in AlloDerm and Cortiva; P = 0.97) and in the prepectoral plane (81% in AlloDerm versus 80% in Cortiva; P = 0.78). Median time to final drain removal was 13 days in both cohorts (IQR, 9, 16 for both; P = 0.38).

Table 3.

Breast-Level Reconstruction Characteristicsa

| Variable | AlloDerm RTU (n = 280) | Cortiva 1 mm (n = 277) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reconstruction plane, no. (%) | 0.78 | ||

| Prepectoral | 227 (81) | 222 (80) | |

| Subpectoral | 53 (19) | 55 (20) | |

| Shell type, no. (%) | 0.97 | ||

| Smooth | 190 (68) | 189 (68) | |

| Textured | 89 (32) | 88 (32) | |

| Reconstruction type, no. (%) | 0.65 | ||

| Direct to implant | 107 (38) | 102 (37) | |

| TE | 38 (14) | 35 (13) | |

| TE to implant | 102 (36) | 108 (39) | |

| TE to flap | 32 (11) | 28 (10) | |

| TE to flap + implant | 1 (0.4) | 4 (1.4) | |

| Ratio of initial fill volume to mastectomy specimen weight, median (IQR), mL/g | 0.53 (0.28, 0.98) | 0.50 (0.27, 0.95) | 0.38 |

| Time to final drain removal, median (IQR), days | 13 (9, 16) | 13 (9, 16) | 0.38 |

RTU, ready to use; TE, tissue expander.

Complications

The incidence of reconstructive failure was 9.3% in patients with AlloDerm versus 8.3% in patients with Cortiva (P = 0.68). The most common complications were seroma (12% in patients with AlloDerm versus 7.6% in patients with Cortiva; P = 0.09) and infection (9.3% versus 8.7%; P = 0.80), which did not differ by cohort. Incidences of hematoma, necrosis, incisional dehiscence, implant exposure, or surgical exploration without explantation, or analgesic use 2 and 4 weeks postoperatively, did not differ across groups (Table 4).

Table 4.

Breast-Level Postoperative Complications and Analgesia Use

| Variable | AlloDerm RTU, No. (%) (n = 280) | Cortiva 1 mm, No. (%) (n = 277) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Reconstructive failure | 26 (9.3) | 23 (8.3) | 0.68 |

| Hematoma | 10 (3.6) | 4 (1.4) | 0.17 |

| Seroma | 33 (12) | 21 (7.6) | 0.09 |

| Infection | 26 (9.3) | 24 (8.7) | 0.80 |

| Necrosis | 22 (7.9) | 17 (6.1) | 0.43 |

| Incisional dehiscence | 16 (5.7) | 14 (5.1) | 0.73 |

| Exposure of implant or TE | 4 (1.4) | 6 (2.2) | 0.51 |

| Surgical exploration | 14 (5.0) | 8 (2.9) | 0.20 |

| Analgesia use at 2 weeksa | 112 (91) | 126 (95) | 0.25 |

| Analgesia use at 4 weeksa | 46 (48) | 63 (58) | 0.18 |

RTU, ready to use; TE, tissue expander.

Patient-level analgesia use.

The incidence of reconstructive failure was not different between ADMs in either plane, and the most common complications remained infection and seroma (Table 5). A subgroup analysis by reconstruction type revealed no significant differences in complication rates within patients who underwent TE reconstruction; however, among patients who underwent DTI reconstruction, surgical exploration was more common with AlloDerm than Cortiva (5.6% versus 0%; P = 0.03; Table 6).

Table 5.

Postoperative Complications and Analgesia Use with Subgroup Analysis by Plane of Reconstruction (Prepectoral versus Subpectoral)

| Variable | Prepectoral | Subpectoral | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlloDerm RTU, No. (%) (n = 227) | Cortiva 1 mm, No. (%) (n = 222) | P | AlloDerm RTU, No. (%) (n = 53) | Cortiva 1 mm, No. (%) (n = 55) | P | |

| Reconstructive failure | 22 (9.7) | 18 (8.1) | 0.55 | 4 (7.6) | 5 (9.1) | 0.77 |

| Hematoma | 7 (3.1) | 4 (1.8) | 0.54 | 3 (5.7) | 0 (0) | 0.12 |

| Seroma | 25 (11) | 18 (8.1) | 0.30 | 8 (15) | 3 (5.5) | 0.10 |

| Infection | 22 (9.7) | 20 (9.0) | 0.80 | 4 (7.6) | 4 (7.3) | >0.99 |

| Necrosis | 19 (8.4) | 15 (6.8) | 0.51 | 3 (5.7) | 2 (3.6) | 0.68 |

| Incisional dehiscence | 13 (5.7) | 13 (5.9) | 0.95 | 3 (5.7) | 1 (1.8) | 0.36 |

| Exposure of implant or TE | 3 (1.3) | 5 (2.3) | 0.50 | 1 (1.9) | 1 (1.8) | >0.99 |

| Surgical exploration | 10 (4.4) | 5 (2.3) | 0.20 | 4 (7.6) | 3 (5.5) | 0.71 |

| Analgesia use at 2 weeksa | 90 (89) | 103 (95) | 0.15 | 22 (100) | 23 (96) | >0.99 |

| Analgesia use at 4 weeksa | 34 (48) | 50 (59) | 0.17 | 12 (50) | 13 (54) | 0.77 |

RTU, ready to use; TE, tissue expander.

Patient-level analgesia use.

Table 6.

Postoperative Complications and Analgesia Use with Subgroup Analysis by Reconstruction Type (Direct to Implant versus Tissue Expander)

| Variable | Direct to Implant | Tissue Expander | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AlloDerm RTU, No. (%) (n = 107) | Cortiva 1 mm, No. (%) (n = 102) | P | AlloDerm RTU, No. (%) (n = 173) | Cortiva 1 mm, No. (%) (n = 175) | P | |

| Reconstructive failure | 5 (4.7) | 3 (2.9) | 0.72 | 21 (12) | 20 (11) | 0.84 |

| Hematoma | 4 (3.7) | 0 (0) | 0.12 | 6 (3.5) | 4 (2.3) | 0.54 |

| Seroma | 5 (4.7) | 4 (3.9) | >0.99 | 28 (16) | 17 (9.7) | 0.07 |

| Infection | 5 (4.7) | 7 (6.9) | 0.50 | 21 (12) | 17 (9.7) | 0.47 |

| Necrosis | 7 (6.5) | 3 (2.9) | 0.33 | 15 (8.7) | 14 (8.0) | 0.82 |

| Incisional dehiscence | 5 (4.7) | 3 (2.9) | 0.72 | 11 (6.4) | 11 (6.3) | 0.98 |

| Exposure of implant or TE | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | >0.99 | 4 (2.3) | 6 (3.4) | 0.75 |

| Surgical exploration | 6 (5.6) | 0 (0) | 0.03a | 8 (4.6) | 8 (4.6) | 0.98 |

| Analgesia use at 2 weeksb | 42 (89) | 47 (96) | 0.16 | 69 (93) | 78 (94) | >0.99 |

| Analgesia use at 4 weeksb | 14 (45) | 21 (59) | 0.33 | 32 (50) | 41 (57) | 0.42 |

RTU, ready to use; TE, tissue expander.

Statistically significant.

Patient-level analgesia use.

Multivariable stepwise logistic regression identified associations between nipple-sparing mastectomy, prepectoral plane, textured shell, other breast surgeon (ie, breast surgeon contributing fewer than 10 cases to the study), and mastectomy specimen weight with increased rates of reconstructive failure (Table 7). ADM type did not achieve the 0.2 P value threshold for entry into the model. Stepwise regression for seroma identified other breast surgeon, former smoking, and mastectomy specimen weight as significant risk factors (Table 7). However, ADM type was also significantly associated with seroma formation while accounting for these risk factors: use of AlloDerm was associated with an almost two-fold higher odds of seroma than use of Cortiva (OR, 1.93 [95% CI, 1.01–3.67]; P = 0.047).

Table 7.

Multivariable Logistic Regressions for Reconstructive Failure and Seroma Formationa

| Variable | Reconstructive Failure | Seroma Formation | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P | Odds Ratio | 95% CI | P | |

| AlloDerm RTU (ref = Cortiva 1 mm) | — | — | — | 1.93 | (1.01, 3.67) | 0.047b |

| Nipple-sparing mastectomy (ref = skin-sparing) | 2.63 | (1.14, 6.05) | 0.02b | — | — | — |

| Prepectoral plane (ref = subpectoral) | 2.92 | (1.08, 7.89) | 0.03b | — | — | — |

| Textured shell (ref = smooth) | 4.32 | (1.93, 9.67) | <0.001b | 1.98 | (0.97, 4.05) | 0.06 |

| Breast surgeon (ref = surgeon A) | ||||||

| Surgeon B | 0.75 | (0.08, 6.77) | 0.80 | 0.50 | (0.06, 4.39) | 0.53 |

| Surgeon C | 0.92 | (0.24, 3.52) | 0.90 | 1.48 | (0.52, 4.21) | 0.47 |

| Surgeon D | 2.88 | (0.76, 10.97) | 0.12 | 1.48 | (0.31, 7.16) | 0.62 |

| Other | 4.53 | (1.45, 14.15) | 0.009b | 5.87 | (2.11, 16.35) | <0.001b |

| Hypertension | 1.79 | (0.84, 3.79) | 0.13 | — | — | — |

| Smoking status (ref = never smoker) | ||||||

| Former smoking | 1.94 | (0.94, 4.00) | 0.07 | 2.78 | (1.41, 5.48) | 0.003b |

| Current smoking | 2.10 | (0.79, 5.58) | 0.14 | 1.38 | (0.48, 3.95) | 0.55 |

| Chemotherapy | 0.61 | (0.30, 1.27) | 0.19 | 0.51 | (0.25, 1.05) | 0.07 |

| Specimen weight, g | 1.002 | (1.001, 1.003) | <0.001b | 1.002 | (1.001, 1.003) | <0.001b |

RTU, ready to use.

Candidate variables that did not meet threshold for inclusion in the final model for reconstructive failure were acellular dermal matrix type, reconstruction type (direct to implant versus tissue expander), plastic surgeon, age, body mass index, diabetes, and radiation. Candidate variables that did not meet threshold for inclusion in the final model for seroma formation were mastectomy type, plane of reconstruction, reconstruction type (direct to implant versus tissue expander), plastic surgeon, age, body mass index, diabetes, hypertension, and radiation.

Statistically significant.

Patient-Reported Outcomes

Preoperative Q scores assessed with the BREAST-Q were not significantly different between the AlloDerm and Cortiva cohorts (Table 8). Postoperative well-being scores did not differ by ADM type. Satisfaction with Breasts, Psychosocial Well-being, and Sexual Well-being Q scores were similar postoperatively compared with preoperatively; however, in both groups, Physical Well-being tended to be lower postoperatively, with no difference by ADM type (−9 [IQR −21, 0] in AlloDerm versus −10 [IQR −20, 0] in Cortiva; P = 0.74).

Table 8.

Preoperative, Postoperative, and Change in BREAST-Q Scores in Patients with AlloDerm RTU and Cortiva 1 mm ADM

| Variable | AlloDerm RTU, Median (IQR) (n = 151) | Cortiva 1 mm, Median (IQR) (n = 151) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Satisfaction with Breasts | |||

| Preoperative | 58 (43, 63) | 53 (43, 63) | 0.38 |

| Postoperative | 58 (50, 71) | 58 (45.5, 71) | 0.51 |

| Change | 2 (−8, 19) | 2 (−12, 15) | 0.66 |

| Psychosocial Well-being | |||

| Preoperative | 63 (55, 76) | 63 (57, 76) | 0.45 |

| Postoperative | 67 (57, 92) | 64 (57, 92) | 0.98 |

| Change | 0 (−12, 16) | 0 (−6, 11) | 0.77 |

| Physical Well-being | |||

| Preoperative | 77 (71, 91) | 81 (74, 91) | 0.10 |

| Postoperative | 68 (60, 81) | 71 (63, 81) | 0.10 |

| Change | −9 (−21, 0) | −10 (−20, 0) | 0.74 |

| Sexual Well-being | |||

| Preoperative | 54 (45, 63) | 54 (45, 63) | 0.90 |

| Postoperative | 57 (41, 67) | 54 (43, 63) | 0.64 |

| Change | 0 (−14, 13) | −2 (−15, 8) | 0.28 |

| Postoperative satisfaction | |||

| Satisfaction with outcome | 75 (61, 86) | 75 (61, 86) | 0.59 |

| Satisfaction with information | 80 (62, 100) | 77 (60, 91) | 0.28 |

| Satisfaction with plastic surgeon | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 0.83 |

| Satisfaction with medical team other than plastic surgeon | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 0.46 |

| Satisfaction with office staff | 100 (100, 100) | 100 (100, 100) | 0.16 |

RTU, ready to use.

There were no significant differences in Q scores across ADM cohorts when subgroup analysis was performed by reconstructive plane or type. (See Table, Supplemental Digital Content 1, which shows a comparison of preoperative, postoperative, and change in BREAST-Q scores in patients with AlloDerm RTU and Cortiva 1 mm ADM, with subgroup analyses by plane of reconstruction. All scores are reported as median [IQR], http://links.lww.com/PRS/H47. See Table, Supplemental Digital Content 2, which shows comparison of preoperative, postoperative, and change in BREAST-Q scores in patients with AlloDerm RTU and Cortiva 1 mm ADM, with subgroup analyses by reconstruction type. All scores are reported as median [IQR], http://links.lww.com/PRS/H48.)

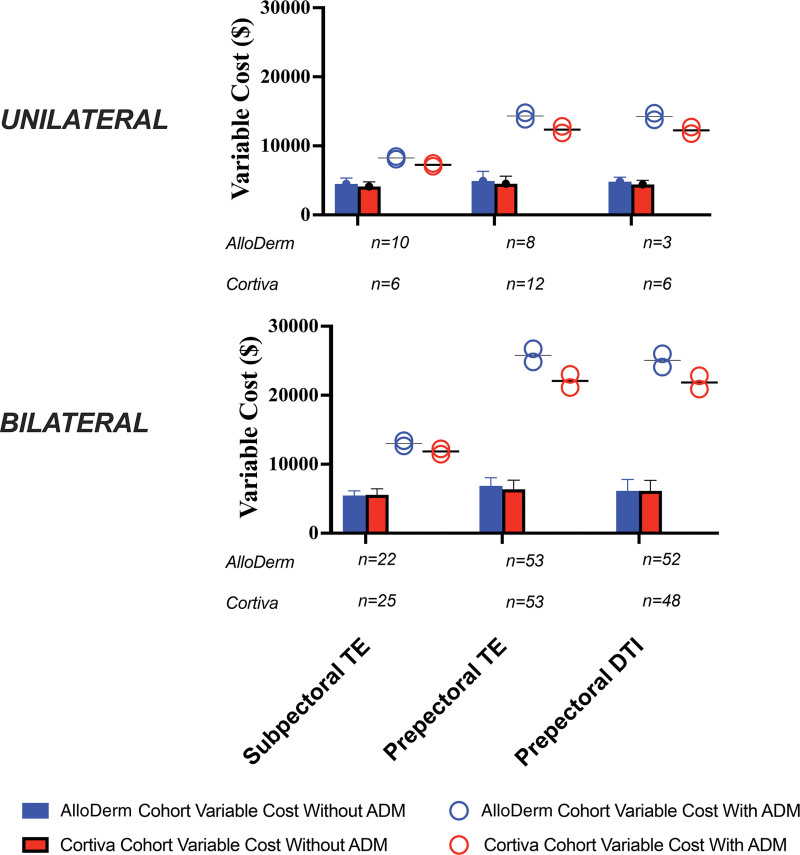

Cost Analysis

Overall variable costs were obtained for all patients. Three patients were excluded (2 AlloDerm, 1 Cortiva) because of an additional pharmacy cost for an unrelated pharmacy charge of $13,920 to $13,990, far in excess of the $19 to $1931 range exhibited in the remaining 299 patients (Fig. 2). Excluding ADM, variable costs for unilateral reconstructions ranged from $4354 ± $786 for subpectoral to $4677 ± $1216 for prepectoral TEs, and for bilateral reconstructions from $5509 ± $776 for subpectoral to $6606 ± $1274 for prepectoral TEs (Fig. 2). (See Table, Supplemental Digital Content 3, which shows variable costs by treatment cohort, with and without effect of ADM, http://links.lww.com/PRS/H49.) ADMs increased variable costs of reconstruction from 71.4% for a unilateral subpectoral TE reconstruction with Cortiva at its lower cost range of $23/cm2 to 323.8% for a bilateral prepectoral DTI reconstruction with AlloDerm at its higher cost range of $31/cm2.

Fig. 2.

Cost of subpectoral TE or prepectoral TE or DTI breast reconstructions using AlloDerm or Cortiva in unilateral or bilateral settings. Mean variable costs generated from actual patients are presented in bar graphs and exclude the cost of ADM. Costs with ADM assuming $28 to $31/cm2 for AlloDerm (blue) and $23 to $26/cm2 for Cortiva (red) are depicted as circles. The use of an ADM increases variable cost from 1.7 times (unilateral, subpectoral TE with Cortiva) to 4.2 times (bilateral, prepectoral DTI with AlloDerm) at the time of primary immediate reconstruction.

DISCUSSION

An evidence-based approach accounting for safety, clinical performance, and PROs should drive the breast reconstruction shared decision-making process. However, there are few comprehensive randomized studies comparing the various ADMs.34,38,42,47,55,61 Current meta-analyses are heavily biased to retrospective studies of subpectoral implant placement.40,41 AlloDerm is the most studied and used noncrosslinked human ADM for breast reconstruction.18,34,35,37–43,45–53,55,61–71 Cortiva, another noncrosslinked human ADM, has been safely used in a series of 183 prepectoral breast reconstructions,72 and demonstrated no significant differences compared with AlloDerm after retrospective review of 298 reconstructions.44 AlloDerm and Cortiva share similar elastin, collagen, and vascular remodeling characteristics.73 Herein we present the first randomized controlled trial comprehensively comparing Cortiva with AlloDerm in immediate prepectoral and subpectoral prosthetic breast reconstruction.

The complications reported in our study are consistent with those reported in the literature surrounding implant-based breast reconstruction with ADM, and are no different between AlloDerm and Cortiva: overall seroma rate of 9.7% (literature range 0% to 30%); infection, 9% (0% to 29%); mastectomy flap necrosis, 7% (0% to 25%); and reconstructive failure, 8.8% (0% to 30%).6–9,13–15,17–19,27,28,31,32,34,35,37–39,43–45,47–49,51,52,61,64,66,69,70,74–82 However, multivariable logistic regression found that reconstruction with AlloDerm increased odds of seroma formation two-fold. We also found that prepectoral implant placement increased odds of reconstructive failure three-fold. One hypothesis is that the risk of the known complications associated with ADM use would be increased with prepectoral reconstruction, as more ADM is used for full anterior prosthesis coverage. Why odds of seroma formation were higher with AlloDerm is less clear, but also a potentially less important finding, as ADM type was not associated with increased odds of reconstructive failure. Only 2 studies comparing ADMs have found seromas to be more common with AlloDerm when compared with another ADM—Surgimend52 and Strattice.53 However, the AlloDerm used in both studies was different from ours as it underwent aseptic versus sterile processing. In addition, Butterfield52 noted that drain practices changed during the study, which could confound results. Drain duration in our study was no different between ADMs and on average 13 days, well within the ranges reported by Glasberg and Light53 and Keifer et al.44

While previous work suggests that seromas increase implant loss and infection four-fold,83 AlloDerm was not associated with increased odds of reconstructive failure, or a significantly greater incidence of infection compared with Cortiva. Despite the differences in manufacturing processes (sterilization assurance level of 10−3 for AlloDerm RTU versus 10−6 for Cortiva 1 mm), infection may not be solely predicted by ADM type. The breast is known to be a clean-contaminated surgical site populated with bacteria throughout and a microbiome more diverse than skin.84 Mastectomy with immediate reconstruction undoubtedly leads to some level of bacterial contamination despite surgeons’ best efforts to maintain sterility, and even imperceptible defects in a healing incision can provide portals for bacterial translocation.85 Drain placement and home drain care, which controls seromas, provides a conduit for cutaneous flora. In addition, there are multiple additional nonsurgical factors that increase risk for infection, including BMI, radiation, and smoking.10,13,23–33 Given these multiple contributing factors, it is unlikely that the 1000 times greater sterilization assurance level of Cortiva makes a clinically significant difference in infection and reconstructive failure outcomes.

Because complications and PROs did not differ significantly between AlloDerm and Cortiva, cost becomes a differentiating factor with ADM selection. Cortiva was 10% to 15% less expensive than AlloDerm at our institution. With ADM excluded, variable costs did not differ significantly between cohorts. ADM use increased variable costs dramatically in our series—a minimum of 1.7 times in unilateral subpectoral reconstructions with Cortiva that used a relatively small, single 128 cm2 sheet. In bilateral prepectoral reconstructions, with two 320 cm2 sheets, ADM increased variable costs at least 4 times. Indeed, this finding supports the need to identify more economical approaches to prepectoral breast reconstruction with implants or autologous tissue. Furthermore, the cost of ADM has a considerable effect on the overall cost of primary prosthetic breast reconstruction and its economic sustainability, particularly when there are no detectable differences in outcome. Although breast reconstruction is covered by insurance, up to a third of patients undergoing breast reconstruction still pay over $5000 of out-of-pocket costs.86 Moreover, patients are frequently forced to make tradeoffs (with decreased spending on basic items) or leverage savings to pay for cancer care.86 This financial toxicity is associated with diminished quality of life, treatment nonadherence, and increased mortality rates.86–89

This study has limitations. It was a 2-center study involving 2 plastic surgeons, with the majority of mastectomies performed by a single breast oncologic surgeon. Therefore, there was little heterogeneity in technique, and our findings may not be generalizable to all practices. There were several changes that occurred during the study period, including the transition from subpectoral to prepectoral reconstruction, conversion to only smooth devices owing to the Food and Drug Administration macrotextured implant recall, and interruption in enrollment due to COVID-19. These changes were likely mitigated in part by our randomized design. In addition, although complications such as reconstructive failure and seroma typically arise in the first 3 months after prosthetic reconstruction,26,90,91 we did not examine long-term outcomes, which may have influenced reoperation rates and overall cost.

CONCLUSIONS

This randomized controlled trial establishes that Cortiva is noninferior to AlloDerm in immediate prosthetic breast reconstruction when assessing safety, complications, and PROs, regardless of reconstructive type (DTI or TE) or plane (subpectoral or prepectoral). AlloDerm may also increase risk of seroma formation. Surgeons should use an evidence-based approach informed by safety, clinical performance, PROs, and cost to aid the shared decision-making process in breast reconstruction.

DISCLOSURE

Dr. Myckatyn receives investigator-initiated grant funding, royalties, and advisory board renumeration from RTI Surgical, and investigator-initiated grant funding from Sientra. Royalties are not derived from the product studied in this article, and Dr. Myckatyn has not ever used the product for which he has received royalties. Dr. Tenenbaum receives consulting fees from NC8, Allergan, and RTI Surgical, and grant funding from Mentor. The remaining authors have no financial interests to report.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was funded by an unencumbered investigator-initiated research award to Dr. Myckatyn from RTI Surgical, Inc., and by a Barnes Jewish Foundation Grant to Dr. Myckatyn earmarked for studies related to postmastectomy breast reconstruction. Use of REDCap at Washington University was supported by a Clinical and Translational Science Award grant (UL1 TR000448), Siteman Comprehensive Cancer Center, and a National Cancer Institute Cancer Center support grant (P30 CA091842). The funders had no involvement in research study design or conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, or interpretation of data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; or the decision to submit the manuscript for publication.

The authors thank Colleen Kilbourne Glynn, Kelly Koogler, Corrine Merrill, and Tracey Guthrie for study administration. This study was funded by an unencumbered, investigator-initiated research grant to Dr. Myckatyn from RTI Surgical as well as funds from a Barnes Jewish Foundation grant to Dr. Myckatyn.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

This trial is registered under the name “Compare Outcomes between Two Acellular Dermal Matrices,” Clinical Trials.gov identification no. NCT02891759 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/study/NCT02891759).

Disclosure statements are at the end of this article, following the correspondence information.

Related digital media are available in the full-text version of the article on www.PRSJournal.com.

REFERENCES

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Fuchs HE, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2022. CA Cancer J Clin. 2022;72:7–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Society of Plastic Surgeons. 2020 Plastic Surgery Statistics Report: ASPS National Clearinghouse of Plastic Surgery Procedural Statistics. Available at: https://www.plasticsurgery.org/documents/News/Statistics/2020/plastic-surgery-statistics-full-report-2020.pdf. Accessed March 14, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Albornoz CR, Bach PB, Mehrara BJ, et al. A paradigm shift in U.S. breast reconstruction: increasing implant rates. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Albornoz CR, Cordeiro PG, Farias-Eisner G, et al. Diminishing relative contraindications for immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2014;134:363e–369e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gamboa-Bobadilla GM. Implant breast reconstruction using acellular dermal matrix. Ann Plast Surg. 2006;56:22–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sbitany H, Serletti JM. Acellular dermis-assisted prosthetic breast reconstruction: a systematic and critical review of efficacy and associated morbidity. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;128:1162–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lanier ST, Wang ED, Chen JJ, et al. The effect of acellular dermal matrix use on complication rates in tissue expander/implant breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2010;64:674–678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sbitany H, Sandeen SN, Amalfi AN, Davenport MS, Langstein HN. Acellular dermis-assisted prosthetic breast reconstruction versus complete submuscular coverage: a head-to-head comparison of outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:1735–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Smith JM, Broyles JM, Guo Y, Tuffaha SH, Mathes D, Sacks JM. Human acellular dermis increases surgical site infection and overall complication profile when compared with submuscular breast reconstruction: an updated meta-analysis incorporating new products. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2018;71:1547–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Qureshi AA, Broderick KP, Belz J, et al. Uneventful versus successful reconstruction and outcome pathways in implant-based breast reconstruction with acellular dermal matrices. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:173e–183e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhao X, Wu X, Dong J, Liu Y, Zheng L, Zhang L. A meta-analysis of postoperative complications of tissue expander/implant breast reconstruction using acellular dermal matrix. Aesthetic Plast Surg. 2015;39:892–901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee KT, Mun GH. Updated evidence of acellular dermal matrix use for implant-based breast reconstruction: a meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:600–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Pannucci CJ, Antony AK, Wilkins EG. The impact of acellular dermal matrix on tissue expander/implant loss in breast reconstruction: an analysis of the tracking outcomes and operations in plastic surgery database. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ho G, Nguyen TJ, Shahabi A, Hwang BH, Chan LS, Wong AK. A systematic review and meta-analysis of complications associated with acellular dermal matrix-assisted breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2012;68:346–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim JYS, Davila AA, Persing S, et al. A meta-analysis of human acellular dermis and submuscular tissue expander breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:28–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoppe IC, Yueh JH, Wei CH, Ahuja NK, Patel PP, Datiashvili RO. Complications following expander/implant breast reconstruction utilizing acellular dermal matrix: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Eplasty. 2011;11:e40. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chun YS, Verma K, Rosen H, et al. Implant-based breast reconstruction using acellular dermal matrix and the risk of postoperative complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:429–436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Selber JC, Wren JH, Garvey PB, et al. Critical evaluation of risk factors and early complications in 564 consecutive two-stage implant-based breast reconstructions using acellular dermal matrix at a single center. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136:10–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Parks JW, Hammond SE, Walsh WA, Adams RL, Chandler RG, Luce EA. Human acellular dermis versus no acellular dermis in tissue expansion breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;130:739–746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ostapenko E, Nixdorf L, Devyatko Y, Exner R, Wimmer K, Fitzal F. Prepectoral versus subpectoral implant-based breast reconstruction: a systemic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2023;30:126–136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Megevand V, Scampa M, McEvoy H, Kalbermatten DF, Oranges CM. Comparison of outcomes following prepectoral and subpectoral implants for breast reconstruction: systematic review and meta-analysis. Cancers (Basel) 2022;14:4223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Politi MC, Lee CN, Philpott-Streiff SE, et al. A randomized controlled trial evaluating the BREASTChoice tool for personalized decision support about breast reconstruction after mastectomy. Ann Surg. 2020;271:230–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nickel KB, Myckatyn TM, Lee CN, Fraser VJ, Olsen MA, CDC Prevention Epicenter Program. Individualized risk prediction tool for serious wound complications after mastectomy with and without immediate reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29:7751–7764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Parikh RP, Brown G, Sharma K, Yan Y, Myckatyn TM. Immediate implant-based breast reconstruction with acellular dermal matrix: a comparison of sterile and aseptic AlloDerm in 2039 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142:1401–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilkins EG, Hamill JB, Kim HM, et al. Complications in postmastectomy breast reconstruction: one-year outcomes of the Mastectomy Reconstruction Outcomes Consortium (MROC) study. Ann Surg. 2018;267:164–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dolen UC, Schmidt AC, Um GT, et al. Impact of neoadjuvant and adjuvant chemotherapy on immediate tissue expander breast reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2016;23:2357–2366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Keane AM, Keane GC, Skolnick GB, et al. Immediate post-mastectomy implant-based breast reconstruction: an outpatient procedure? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2023;152:1e–11e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bennett KG, Qi J, Kim HM, Hamill JB, Pusic AL, Wilkins EG. Comparison of 2-year complication rates among common techniques for postmastectomy breast reconstruction. JAMA Surg. 2018;153:901–908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sinha I, Pusic AL, Wilkins EG, et al. Late surgical-site infection in immediate implant-based breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:20–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Davila AA, Seth AK, Wang E, et al. Human acellular dermis versus submuscular tissue expander breast reconstruction: a multivariate analysis of short-term complications. Arch Plast Surg. 2013;40:19–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu AS, Kao HK, Reish RG, Hergrueter CA, May JW, Jr, Guo L. Postoperative complications in prosthesis-based breast reconstruction using acellular dermal matrix. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:1755–1762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Antony AK, McCarthy CM, Cordeiro PG, et al. Acellular human dermis implantation in 153 immediate two-stage tissue expander breast reconstructions: determining the incidence and significant predictors of complications. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2010;125:1606–1614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McCarthy CM, Mehrara BJ, Riedel E, et al. Predicting complications following expander/implant breast reconstruction: an outcomes analysis based on preoperative clinical risk. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2008;121:1886–1892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Broyles JM, Liao EC, Kim J, et al. Acellular dermal matrix-associated complications in implant-based breast reconstruction: a multicenter, prospective, randomized controlled clinical trial comparing two human tissues. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;148:493–500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Parikh RP, Brown GM, Sharma K, Yan Y, Myckatyn TM. Immediate implant-based breast reconstruction with acellular dermal matrix: a comparison of sterile and aseptic AlloDerm in 2039 consecutive cases. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142:1401–1409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Mendenhall SD, Anderson LA, Ying J, Boucher KM, Neumayer LA, Agarwal JP. The BREASTrial stage II: ADM breast reconstruction outcomes from definitive reconstruction to 3 months postoperative. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2017;5:e1209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Asaad M, Morris N, Selber JC, et al. No differences in surgical and patient-reported outcomes between AlloDerm, SurgiMend, and DermACELL for prepectoral implant-based breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2022;151:719e–729e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Asaad M, Selber JC, Adelman DM, et al. Allograft vs xenograft bioprosthetic mesh in tissue expander breast reconstruction: a blinded prospective randomized controlled trial. Aesthet Surg J. 2021;41:NP1931–NP1939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Greig H, Roller J, Ziaziaris W, Van Laeken N. A retrospective review of breast reconstruction outcomes comparing AlloDerm and DermACELL. JPRAS Open 201922;22:19–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Wu LH, Zhang MX, Chen CY, Fang QQ, Wang XF, Tan WQ. Breast reconstruction with AlloDerm ready to use: a meta-analysis of nine observational cohorts. Breast 2018;39:89–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee KT, Mun GH. A meta-analysis of studies comparing outcomes of diverse acellular dermal matrices for implant-based breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2017;79:115–123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hinchcliff KM, Orbay H, Busse BK, Charvet H, Kaur M, Sahar DE. Comparison of two cadaveric acellular dermal matrices for immediate breast reconstruction: a prospective randomized trial. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2017;70:568–576. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ricci JA, Treiser MD, Tao R, et al. Predictors of complications and comparison of outcomes using SurgiMend fetal bovine and AlloDerm human cadaveric acellular dermal matrices in implant-based breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:583e–591e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Keifer OP, Jr, Page EK, Hart A, et al. A complication analysis of 2 acellular dermal matrices in prosthetic-based breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2016;4:e800. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sobti N, Liao EC. Surgeon-controlled study and meta-analysis comparing FlexHD and AlloDerm in immediate breast reconstruction outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;138:959–967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zenn MR, Salzberg CA. A direct comparison of AlloDerm-ready to use (RTU) and DermACELL in immediate breast implant reconstruction. Eplasty. 2016;16:e23. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mendenhall SD, Anderson LA, Ying J, et al. The BREASTrial: stage I: outcomes from the time of tissue expander and acellular dermal matrix placement to definitive reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;135:29e–42e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seth AK, Persing S, Connor CM, et al. A comparative analysis of cryopreserved versus prehydrated human acellular dermal matrices in tissue expander breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;70:632–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Brooke S, Mesa J, Uluer M, et al. Complications in tissue expander breast reconstruction: a comparison of AlloDerm, DermaMatrix, and FlexHD acellular inferior pole dermal slings. Ann Plast Surg. 2012;69:347–349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Becker S, Saint-Cyr M, Wong C, et al. AlloDerm versus DermaMatrix in immediate expander-based breast reconstruction: a preliminary comparison of complication profiles and material compliance. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;123:1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ranganathan K, Santosa KB, Lyons DA, et al. Use of acellular dermal matrix in postmastectomy breast reconstruction: are all acellular dermal matrices created equal? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2015;136:647–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Butterfield JL. 440 Consecutive immediate, implant-based, single-surgeon breast reconstructions in 281 patients: a comparison of early outcomes and costs between SurgiMend fetal bovine and AlloDerm human cadaveric acellular dermal matrices. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;131:940–951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Glasberg SB, Light D. AlloDerm and Strattice in breast reconstruction: a comparison and techniques for optimizing outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:1223–1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.National Center for Biotechnology Information. Full Microbial Genomes 2013. https://ftp.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sampledata/genomes/. Accessed September 2, 2013.

- 55.Stein MJ, Arnaout A, Lichtenstein JB, et al. A comparison of patient-reported outcomes between AlloDerm and DermACELL in immediate alloplastic breast reconstruction: a randomized control trial. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2021;74:41–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.U.S. Food and Drug Administration.; Allergan voluntarily recalls BIOCELL textured breast implants and tissue expanders. Published July 25, 2019. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/safety/recalls-market-withdrawals-safety-alerts/allergan-voluntarily-recalls-biocellr-textured-breast-implants-and-tissue-expanders. Accessed February 4, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 57.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, Payne J, Gonzalez N, Conde JG. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Harris PA, Taylor R, Minor BL, et al.; REDCap Consortium. The REDCap consortium: Building an international community of software platform partners. J Biomed Inform. 2019;95:103208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Odom EB, Parikh RP, Um G, et al. Nipple-sparing mastectomy incisions for cancer extirpation prospective cohort trial: perfusion, complications, and patient outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;142:13–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Parikh RP, Tenenbaum MM, Yan Y, Myckatyn TM. Cortiva versus AlloDerm ready-to-use in prepectoral and submuscular breast reconstruction: prospective randomized clinical trial study design and early findings. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2018;6:e2013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Arnaout A, Zhang J, Frank S, et al. ; on behalf of the REaCT investigators. A randomized controlled trial comparing AlloDerm-RTU with DermACELL in immediate subpectoral implant-based breast reconstruction. Curr Oncol. 2020;28:184–195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Buseman J, Wong L, Kemper P, et al. Comparison of sterile versus nonsterile acellular dermal matrices for breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2013;70:497–499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Cheng A, Saint-Cyr M. Comparison of different ADM materials in breast surgery. Clin Plast Surg. 2012;39:167–175. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Jansen LA, Macadam SA. The use of AlloDerm in postmastectomy alloplastic breast reconstruction: part I: a systematic review. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2011;127:2232–2244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lewis P, Jewell J, Mattison G, Gupta S, Kim H. Reducing postoperative infections and red breast syndrome in patients with acellular dermal matrix-based breast reconstruction: the relative roles of product sterility and lower body mass index. Ann Plast Surg. 2015;74:S30–S32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Liu DZ, Mathes DW, Neligan PC, Said HK, Louie O. Comparison of outcomes using AlloDerm versus FlexHD for implant-based breast reconstruction. Ann Plast Surg. 2014;72:503–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Lyons DA, Mendenhall SD, Neumeister MW, Cederna PS, Momoh AO. Aseptic versus sterile acellular dermal matrices in breast reconstruction: an updated review. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2016;4:e823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Macarios D, Griffin L, Chatterjee A, Lee LJ, Milburn C, Nahabedian MY. A meta-analysis assessing postsurgical outcomes between aseptic and sterile AlloDerm regenerative tissue matrix. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2015;3:e409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pittman TA, Fan KL, Knapp A, Frantz S, Spear SL. Comparison of different acellular dermal matrices in breast reconstruction: the 50/50 study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;139:521–528. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Weichman KE, Wilson SC, Saadeh PB, et al. Sterile “ready-to-use” AlloDerm decreases postoperative infectious complications in patients undergoing immediate implant-based breast reconstruction with acellular dermal matrix. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2013;132:725–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Yuen JC, Yue CJ, Erickson SW, et al. Comparison between freeze-dried and ready-to-use AlloDerm in alloplastic breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2014;2:e119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Urquia LN, Hart AM, Liu DZ, Losken A. Surgical outcomes in prepectoral breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2020;8:e2744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Moyer HR, Hart AM, Yeager J, Losken A. A histological comparison of two human acellular dermal matrix products in prosthetic-based breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2017;5:e1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Baker BG, Irri R, MacCallum V, Chattopadhyay R, Murphy J, Harvey JR. A prospective comparison of short-term outcomes of subpectoral and prepectoral Strattice-based immediate breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2018;141:1077–1084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bettinger LN, Waters LM, Reese SW, Kutner SE, Jacobs DI. Comparative study of prepectoral and subpectoral expander-based breast reconstruction and Clavien IIIb score outcomes. Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open 2017;5:e1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Momeni A, Remington AC, Wan DC, Nguyen D, Gurtner GC. A matched-pair analysis of prepectoral with subpectoral breast reconstruction: is there a difference in postoperative complication rate? Plast Reconstr Surg. 2019;144:801–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Nahabedian MY, Cocilovo C. Two-stage prosthetic breast reconstruction: a comparison between prepectoral and partial subpectoral techniques. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140:22S–30S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Sbitany H, Piper M, Lentz R. Prepectoral breast reconstruction: a safe alternative to submuscular prosthetic reconstruction following nipple-sparing mastectomy. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140:432–443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.DeLong MR, Tandon VJ, Bertrand AA, et al. Review of outcomes in prepectoral prosthetic breast reconstruction with and without surgical mesh assistance. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147:305–315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Lohmander F, Lagergren J, Johansson H, Roy PG, Brandberg Y, Frisell J. Effect of Immediate implant-based breast reconstruction after mastectomy with and without acellular dermal matrix among women with breast cancer: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open 2021;4:e2127806. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sorkin M, Qi J, Kim HM, et al. Acellular dermal matrix in immediate expander/implant breast reconstruction: a multicenter assessment of risks and benefits. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2017;140:1091–1100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Weichman KE, Wilson SC, Weinstein AL, et al. The use of acellular dermal matrix in immediate two-stage tissue expander breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2012;129:1049–1058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Jordan SW, Khavanin N, Kim JYS. Seroma in prosthetic breast reconstruction. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137:1104–1116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bartsich S, Ascherman JA, Whittier S, Yao CA, Rohde C. The breast: a clean-contaminated surgical site. Aesthet Surg J. 2011;31:802–806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Walker JN, Hanson BM, Hunter T, et al. A prospective randomized clinical trial to assess antibiotic pocket irrigation on tissue expander breast reconstruction. Microbiol Spectr. 2023;11:e0143023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Asaad M, Bailey C, Boukovalas S, et al. Self-reported risk factors for financial distress and attitudes regarding cost discussions in cancer care: a single-institution cross-sectional pilot study of breast reconstruction recipients. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2021;147:587e–595e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Ell K, Xie B, Wells A, Nedjat-Haiem F, Lee PJ, Vourlekis B. Economic stress among low-income women with cancer: effects on quality of life. Cancer 2008;112:616–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Fenn KM, Evans SB, McCorkle R, et al. Impact of financial burden of cancer on survivors’ quality of life. J Oncol Pract. 2014;10:332–338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ramsey SD, Bansal A, Fedorenko CR, et al. Financial insolvency as a risk factor for early mortality among patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:980–986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Nickel KB, Myckatyn TM, Lee CN, Fraser VJ, Olsen MA, Program CDCPE. Individualized risk prediction tool for serious wound complications after mastectomy with and without immediate reconstruction. Ann Surg Oncol. 2022;29:7751–7764. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Olsen MA, Nickel KB, Fox IK, Margenthaler JA, Wallace AE, Fraser VJ. Comparison of wound complications after immediate, delayed, and secondary breast reconstruction procedures. JAMA Surg. 2017;152:e172338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.