Abstract

Nuclear transport of viral nucleic acids is crucial to the life cycle of many viruses. Borna disease virus (BDV) belongs to the order Mononegavirales and replicates its RNA genome in the nucleus. Previous studies have suggested that BDV nucleoprotein (N) and phosphoprotein (P) have important functions in the nuclear import of the viral ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes via their nuclear targeting activity. Here, we showed that BDV N has cytoplasmic localization activity, which is mediated by a nuclear export signal (NES) within the sequence. Our analysis using deletion and substitution mutants of N revealed that NES of BDV N consists of a canonical leucine-rich motif and that the nuclear export activity of the protein is mediated through the chromosome region maintenance protein-dependent pathway. Interspecies heterokaryon assay indicated that BDV N shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm as a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein. Furthermore, interestingly, the NES region overlaps a binding site to the BDV P protein, and nuclear export of a 38-kDa form of BDV N is prevented by coexpression of P. These results suggested that BDV N has two contrary activities, nuclear localization and export activity, and plays a critical role in the nucleocytoplasmic transport of BDV RNP by interaction with other viral proteins.

Many viruses, including influenza viruses, herpesviruses, and retroviruses, replicate in the nucleus. Therefore, nuclear import and export of the viral genome are critical to the life cycle of viruses in mammalian cells. It has been reported that these virus employ mechanisms by which the viral nucleic acids enter and leave the nucleus in association with their replication stages (51). In human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1), viral proteins including integrase, matrix (MA), and Vpr promote localization of the viral preintegration complex (PIC) to the nucleus following the entry of virus into a cell (4, 10, 33, 45). The MA protein harbors nuclear export activity, in addition to nuclear localization activity, to direct the viral RNAs to the cytoplasm (8). Rev proteins of HIV-1 also have both these nuclear transport activities to transport unspliced or single spliced viral transcripts (32). On the other hand, the nucleocapsid protein (NP) and the nonstructural proteins (NS2 and NEP) of influenza A virus are required for nuclear import and export of the viral ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex, respectively (9, 28–31, 47). Furthermore, matrix protein (M1) of the influenza virus also plays an essential role in RNP nuclear export in combination with other viral proteins (51). Studies of these nuclear transport proteins revealed that they contain specific signals that mediate nuclear transport, called the nuclear localization signal (NLS) and the nuclear export signal (NES), which function independently of the surrounding sequences (27, 51). NLS- or NES-containing proteins can directly or indirectly bind to the viral nucleic acids and travel between the cytoplasm and nucleus through the nuclear pore complex (13, 27, 51). Recent studies have revealed that the pathway of nuclear transport of the signal-containing proteins is mediated by common host cellular proteins (13, 27). Therefore, analysis of viral nuclear transport proteins provides a better understanding not only of viral replication but also of interaction between viruses and host cells.

Borna disease virus (BDV) is a unique nonsegmented, negative-strand RNA virus that belongs to the order Mononegavirales (3, 6, 7, 37). Despite its similarity in genomic organization to other members of this order, BDV has several clearly distinguishing features. One of the most striking characteristics of BDV is its localization for transcription. BDV replicates and transcribes in the nucleus of infected cells (5), while the other animal viruses of this order undergo their life cycle in the cell cytoplasm. Molecular biological analysis has indicated that the BDV antigenome consists of at least six open reading frames (ORFs). The ORFs encode nucleoprotein (N), phosphoprotein (P), matrix protein, envelope protein, and a predicted RNA-dependent RNA polymerase in the 5′-to-3′ order (12, 17, 18, 23, 35, 38, 43, 44, 46). In addition, a small ORF X, which overlaps the P ORF, was identified to encode a novel protein X of unknown function (49). Recently, we and Schwemmle et al. have reported that the N and P proteins of BDV have nuclear localization activity, which is mediated by single and bipartite NLSs, respectively (19, 39, 41). These experiments also suggested that nuclear localization of the N and P proteins is critical for nuclear targeting of the BDV RNP complexes, because these proteins interact with each other and are probably essential components of the viral RNPs (5, 15, 25, 40). On the other hand, the NES-like sequence of BDV has been identified in the N terminus of the X protein (40, 52). However, a recent study was not able to demonstrate nuclear export activity for the X protein, despite the fact that the consensus leucine-rich sequence is found in the NES-like motif of the protein (24).

Our analysis reveals that the NES of BDV N contains a canonical leucine-rich motif, and the nuclear export activity of the protein is mediated through the chromosome region maintenance protein (CRM1) pathway. Furthermore, interestingly, a region of the NES overlaps an interaction site for the P protein. Moreover, the nuclear export activity of an isoform of the N protein (p38N), which lacks the NLS-containing N-terminal 13 amino acids of an intact form of N (p40N), is blocked by coexpression of the P protein. We demonstrate that BDV N protein has two contrary activities, nuclear localization and export, and also suggest that N plays a critical role in the nucleocytoplasmic transport of BDV RNPs in combination with other viral proteins.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and virus.

COS-7 (11) and Madin-Darby canine kidney (MDCK) cells were cultured in Dulbecco modified Eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 100 U of penicillin G per ml, 100 μg of streptomycin per ml, and 4 mM glutamine. The OL cell line, derived from human oligodendroglioma, was grown in DMEM-high glucose (4.5%) supplemented with 10% FBS. MDCK/BDV cells (14), which are MDCK cells persistently infected with BDV, were maintained under the same condition as the parental cell line.

Plasmid construction.

The construction of eukaryotic expression vectors containing influenza virus hemagglutinin (HA) epitope for BDV p40N (pHA-p40N), p38N (pHA-p38N), and P (pP-Wild) has been described previously (19, 41). The expression vectors used for protein interaction analysis were generated as follows. A fragment containing histidine (His) epitope was amplified with sense (5′-TGC CTG CAG CCA CCA TGG GTC ATC ATC ATC ATC ATC ATG GTA T-3′) and antisense (5′-GCC GCG GAT CCT CGA GCT GAA TTC CTT ATC GTC ATC GTC GTA-3′) primers with the pTrc-His B plasmid (Invitrogen, San Diego, Calif.) by PCR, and the amplified fragment was inserted into the PstI-EcoRI site of the pcDL-SRα296 eukaryotic expression plasmid (42) to create pcDL-His. To generate pHis-p40N and pHis-p38N, the entire BDV p40N and p38N cDNA sequences were digested from pHA-p40N and pHA-p38N, respectively, and were cloned into the EcoRI-KpnI site of pcDL-His. The expression vectors, pGFP-p40N and pGFP-p38N, were constructed by inserting the BDV p40N and p38N cDNA fragments, respectively, into the EcoRI-KpnI site in the pEGFP-C2 vector (Clontech Laboratories, Inc., Palo Alto, Calif.). To create expression plasmids containing green fluorescent protein (GFP)-fused polypeptide chains from the BDV N sequence, cDNA fragments amplified with a set of primers (Tables 1 and 2) were cloned into the EcoRI-BamHI site of the pEGFP-C2 vector. Plasmid pGFP-R11A, in which L128, L131, I133, and I136 in pGFP-R11 were changed to alanine, was generated with primers 7 and 10 (Tables 1 and 2) by a PCR-based mutagenesis technique described previously (19).

TABLE 1.

PCR primers used for plasmid construction

| Primer | Nucleotide positions | Nucleotide sequencea |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 132–148 | 5′-taggaattcgccaccatggtaCCTAAGCTCCCTGGGAA-3′ |

| 2 | 249–269 | 5′-gtagaattcgccaccatgCGCGATATGTTTGACACAGTA-3′ |

| 3 | 435–455 | 5′-ttagaattcCTCACCGAGCTGGAGATCTCT-3′ |

| 4 | 475–488 | 5′-tgggaattcaccatggGCTCATTGCTAATAGGG-3′ |

| 5 | 654–674 | 5′-taagaattcgccaccatgCCCTGGGTAGGCTCCTTTGTG-3′ |

| 6 | 1002–1024 | 5′-taggaattcgccaccATGGCAGGCTACCGGGCCTCCAC-3′ |

| 7 | 435–469 | 5′-atcgaattcGCCACCGAGGCGGAGGCCTCTTCTGCCTTCAGCCA-3′ |

| 8 | 196–177 | 5′-ttgggatccCCTATACCCGGATGCGGGTC-3′ |

| 9 | 367–348 | 5′-attggatcccggACAGGCGTCGACAGGTAGGA-3′ |

| 10 | 488–468 | 5′-tgaggatccTATTAGCAATGAGCAACAGTG-3′ |

| 11 | 508–492 | 5′-caaggatccGACGATCCTATCACAAC-3′ |

| 12 | 526–504 | 5′-atcggatccCCTGCTTTGATCTTAGACGA-3′ |

| 13 | 773–753 | 5′-taaggatcccgAGTAGTGTACGTAGTCATCTG-3′ |

| 14 | 1015–992 | 5′-ttaggatccCGGTAGCCTGCCATTGTGGGGTT-3′ |

| 15 | 1089–1071 | 5′-tcgggatccGAGATATCTCGCGGCGCCT-3′ |

| 16 | 1166–1149 | 5′-tacggatccTTAGTTTAGACCAGTCAC-3′ |

The restriction sites are underlined; the boldface letters represent nucleotides substituted from the BDV N mRNA.

TABLE 2.

Primer pairs used for plasmid construction

| Construct | Primer pair

|

|

|---|---|---|

| Sense | Antisense | |

| pGFP-R1 | Primer 1 | Primer 9 |

| pGFP-R2 | Primer 1 | Primer 8 |

| pGFP-R3 | Primer 2 | Primer 9 |

| pGFP-R4 | Primer 2 | Primer 12 |

| pGFP-R5 | Primer 3 | Primer 12 |

| pGFP-R6 | Primer 5 | Primer 16 |

| pGFP-R7 | Primer 5 | Primer 14 |

| pGFP-R8 | Primer 5 | Primer 13 |

| pGFP-R9 | Primer 6 | Primer 15 |

| pGFP-R10 | Primer 4 | Primer 11 |

| pGFP-R11 | Primer 3 | Primer 10 |

| pGFP-R11A | Primer 7 | Primer 10 |

Nucleotide sequences of the recombinant constructs were confirmed by DNA sequencing. The nucleotide and amino acid positions follow those previously reported for BDV strain V (EMBL Databank accession no. U046080).

Eukaryotic expression.

Cells were seeded at a concentration of 2.5 × 105 cells/ml in 35-mm tissue culture plates or glass-bottom culture dishes. After overnight culture at 37°C, the cells were transfected using TransFast Transfection reagent (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Two days after transfection, the cells were subjected to indirect immunofluorescence assay (IFA) or Western blot analyses.

IFA.

The transfected cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde prior to treatment with 0.4% Triton X-100 (19). After a reaction with the optimal antibodies (anti-HA, -His, -N, and/or -P antibodies [1:500]) as the first antibody, the cells were stained with fluorescein isothiocynate (FITC)-conjugated donkey anti-mouse or anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) and Cy3-conjugated donkey anti-mouse or anti-rabbit IgG antibodies (Jackson ImmunoResearch Laboratories, Inc., West Grove, Pa.). Immunofluorescence was detected by using an epifluorescence microscope (Nikon Co., Tokyo, Japan) or confocal laser-scanning microscope (Bio-Rad Japan, Tokyo, Japan).

LMB treatment assay.

Leptomycin B (LMB) was kindly provided by M. Yoshida (University of Tokyo). At 48 h posttransfection, the medium was replaced with fresh medium containing LMB (20 ng/ml). The transfected cells were inoculated for 2 h. The cells were fixed, and then the GFP fusion proteins were visualized with GFP fluorescence.

Protein pull-down assay.

COS-7 cells were contransfected with each combination of HA- or His-tagged N expression plasmids. At 48 h posttransfection, transfected cells were lysed by freeze-thaw cycling in Nonidet P-40 (NP-40) lysis buffer (10 mM Tris [pH 7.6], 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% NP-40, 1.5 mM MgCl2, 1.0 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride) (20). After centrifugation, the soluble fraction was reacted with anti-HA monoclonal antibody (MAb; Roche Molecule Biochemicals, Mannheim, Germany) for 2 h at 4°C, and the precipitates were then recovered by incubation with protein G agarose beads (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Santa Cruz, Calif.) for 24 h at 4°C. After a thorough washing, proteins bound to the agarose beads were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (12.5% gel) and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-His polyclonal antibody (PAb; Santa Cruz Biotechnology). The specific reactions were detected by an ECL Western blotting kit (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden).

Heterokaryon assays.

Nucleocytoplasmic shuttling was detected by using an interspecies heterokaryon assay (2, 26, 50). Human OL cells were transiently transfected with pGFP-p40N. After 18 h, mouse 3T3 cells were plated onto the transfected OL cells in medium containing 50 μg of cycloheximide per ml. Four hours later, the cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fused by addition of 50% (wt/wt) polyethylene glycol. After 2 min, the cells were washed extensively in PBS. They were then returned to medium containing 50 μg of cycloheximide per ml for 60 min. After fusion, the cells were fixed and stained with Hoechst 33258 (Sigma) and anti-primate Ku (Oncogene Research Products, Boston, Mass.) and anti-N antibodies.

RESULTS

Coexpression of BDV p38N leads to the cytoplasmic distribution of p40N protein.

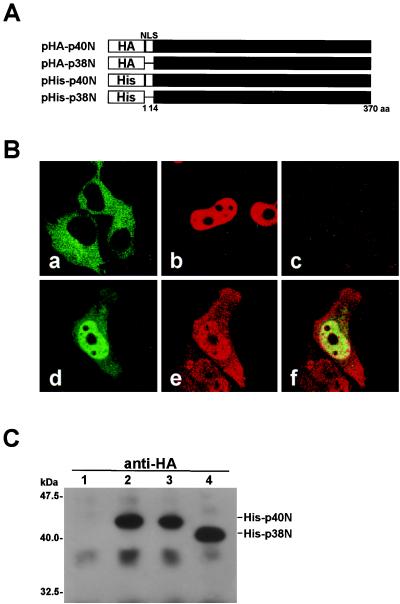

The BDV N protein contains two isoforms, p40N and p38N, of which the translation start sites are separated by a 13-amino-acid stretch (34). Previous studies have demonstrated by transient expression in transfected cells that the BDV p40N protein is localized in the nucleus (19, 34). The 38-kDa form of the N protein alone is not sufficient to direct transportation to the nucleus, because the p38N lacks an NLS (Fig. 1A) (19, 34). Both N proteins are, however, found in the nucleus and cytoplasm of infected cells (34), suggesting that p38N also plays an important role in the viral replication in the nucleus. Thus, we first investigated the intracellular localization of the two isoforms of BDV N in transfected cells. To differentiate between the p40N and p38N proteins, which are translated from the same ORF, we constructed expression plasmids that are tagged with an HA or His epitope sequence in the N terminus of the N ORF, pHA-p40N, pHA-p38N, pHis-p40N, and pHis-p38N (Fig. 1A). Upon the transfection of pHis-p40N into COS-7 cells, p40N was clearly localized only in the nucleus of the transfected cells (Fig. 1Bb). p38N, meanwhile, was found in the cytoplasm on transfection of the pHA-p38N plasmid (Fig. 1Ba). This observation is consistent with the results of a previous study (19). In contrast, however, coexpression of the pHA-p38N and pHis-p40N plasmids led not only to the nuclear localization of p38N but also to the cytoplasmic distribution of p40N (Fig. 1B d, e, and f). These results suggested a potential interaction between the two isoforms of BDV N protein in the cells. The intracellular binding between the p40N and p38N proteins was verified by protein pull-down assay. Each combination of the expression plasmids was transfected into COS-7 cells, and the immunoprecipitation was performed with anti-HA antibody. The precipitants were then detected by Western blotting using anti-His antibody. As shown in Fig. 1C, HA-p40N bound to His-p40N (Fig. 1C, lane 2), while His-p40N and His-p38N were efficiently coimmunoprecipitated with HA-p38N (Fig. 1C, lanes 3 and 4). These results suggested that the N proteins interact with each other and that p38N efficiently promotes either nuclear export or cytoplasmic retention of the NLS-containing p40N protein.

FIG. 1.

BDV p38N expression leads to the cytoplasmic distribution of p40N. (A) Construction of eukaryotic expression plasmids of BDV p40N and p38N. The expression plasmids were constructed by inserting p40N or p38N cDNA immediately downstream of influenza virus HA or a six-histidine (His) epitope of pcDL-SRα296 (42). (B) Subcellular localization of BDV p40N and p38N in transiently transfected COS-7 cells by using confocal laser-scanning microscope. Panels: a, pHA-p38N-transfected cells, anti-HA MAb (FITC); b, pHis-p40N-transfected cells, anti-His PAb (Cy3); c, mock-transfected cells, anti-HA (FITC) and -His (Cy3) antibodies; d to f, pHis-p40N- and pHA-p38N-cotransfected cells, anti-HA (FITC in panels d and f) and anti-His (Cy3 in panels e and f) antibodies. (C) Immunoprecipitation of BDV p40N and p38N. COS-7 cells were cotransfected with p40N and p38N plasmids, and interactions between the proteins were analyzed by the immunoprecipitation assay. Lanes: 1, pHA-p40N alone; 2, pHis-p40N and pHA-p40N; 3, pHis-p40N and pHA-p38N; and 4, pHis-p38N and pHA-p38N. Antibody used for the immunoprecipitation was anti-HA. The precipitants were detected by Western blotting with anti-His PAb.

The BDV N protein contains an NES.

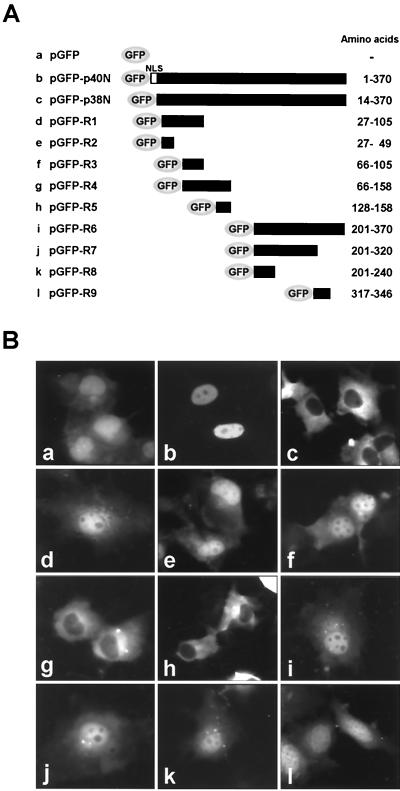

The intracellular localization of the two isoforms of N protein suggested that the BDV N protein may contain cytoplasmic localization activity within the sequence. To determine whether BDV N protein contains such activity, we generated GFP-fused plasmids containing various segments of the N sequence (Fig. 2A). Following transfection of COS-7 cells with the plasmids, expression of the polypeptides was visualized with GFP fluorescence after 48 h. As shown in Fig. 1B, pGFP-p40N and -p38N were localized in the nucleus and cytoplasm of the transfected cells, respectively (Fig. 2Bb and c). The GFP signal was diffusely detected throughout the nucleus and cytoplasm in the cells transfected with pGFP-R1, -R2, -R3, -R6, -R7, -R8, and -R9, as well as with GFP alone (Fig. 2Bd to f and i to l). In contrast, transfection of the pGFP-R4 and -R5 plasmids, which contain amino acids 66 to 158 and amino acids 128 to 158 of the BDV N protein, respectively, resulted in a cytoplasmic distribution of GFP signal (Fig. 2Bg and h). These results indicated that a 31-amino-acid stretch, amino acids 128 to 158, in the BDV N is likely to be involved in cytoplasmic localization of the protein. To investigate the activity found in the 31-amino-acid stretch in more detail, we generated expression plasmids pGFP-R10 and -R11, in which were fused short peptides corresponding to amino acids 142 to 152 and amino acids 128 to 145 of the BDV N, respectively (Fig. 3A). As shown in Fig. 3B, pGFP-R10 was diffusely localized both in the nucleus and cytoplasm, while pGFP-R11 was cytoplasmic (panel c). These results indicated that amino acids 128 to 141, 128LTELEISSIFSHCC141, of the N terminus are important for cytoplasmic localization of the protein. Sequencing of the short stretch revealed that the region contains NES-like leucine or isoleucine residues, L128, L131, I133, and I136, as indicated in other known NESs such as HIV-1 Rev (Fig. 3C) (16, 31, 32). Thus, we next generated a substitution mutant pGFP-R11A in which the L128, L131, I133, and I136 residues were replaced by an alanine residue. pGFP-R11A was diffusely localized to both nucleus and cytoplasm (Fig. 3Bd), indicating that L128, L131, I133, and I136 between amino acids 128 and 141 are important for the cytoplasmic localization of the protein and that the short stretch is a putative NES of BDV N.

FIG. 2.

BDV N contains cytoplasmic localization activity. (A) Schematic presentation of a series of GFP-fused truncated mutants of N. Amino acids regions of N contained in each plasmid are shown at the right. (B) Subcellular localization of truncated BDV N mutants. Panels: a, pGFP; b, pGFP-p40N; c, pGFP-p38N; d, pGFP-R1; e, pGFP-R2; f, pGFP-R3; g, pGFP-R4; h, pGFP-R5; i, pGFP-R6; j, pGFP-R7; k, pGFP-R8; l, pGFP-R9.

FIG. 3.

The N NES containing a canonical leucine-based sequence. (A) Schematic diagram of GFP-fused N fragments. Leucine or isoleucine residues at positions 128, 131, 133, and 136 were replaced by alanine (underlines). (B) Subcellular localization of GFP fusion proteins in COS-7 cells. Panels: a, pGFP-R5; b, pGFP-R10; c, pGFP-R11; d, pGFP-R11A. (C) A consensus leucine-based NES sequence of BDV N is indicated with those of previously characterized viral proteins, HIV-1 Rev, human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 (HTLV-1) Rex, and influenza A virus NS2. Important hydrophobic residues are underlined.

The nuclear export of BDV N is a CRM1-dependent pathway.

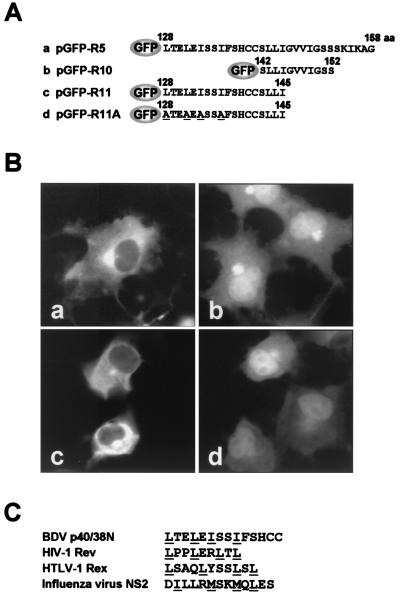

The mechanism of NES-dependent nuclear export has been elucidated from the findings that NES-containing peptides form a complex with CRM1, nuclear NES-binding receptor, or exportin 1 (13, 27). On the other hand, LMB inhibits the nuclear export of NES-containing proteins by interfering with the interaction between CRM1 and NES by directly binding to CRM1 (22). Therefore, in order to determine whether LMB can inhibit the NES function of BDV N, COS-7 cells were transfected with pGFP-R11 and treated with LMB for 2 h at 48 h posttransfection. As shown in Fig. 4, the pGFP-R11-transfected cells showed a cytoplasmic fluorescence pattern without LMB treatment (Fig. 4a; see also Fig. 3Bc). However, LMB treatment abolished the nuclear exclusion of GFP in the cells transfected with pGFP-R11 (Fig. 4b). These results suggested that BDV N contains a functional NES, the function of which is mediated by a CRM1-dependent pathway.

FIG. 4.

The nuclear export of BDV N is a CRM1-dependent pathway. pGFP-R11-transfected COS-7 cells were left untreated (a) or were treated with LMB (20 ng/ml for 2 h) (b). GFP fluorescence was visualized after fixation of the cells.

The BDV N is a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein.

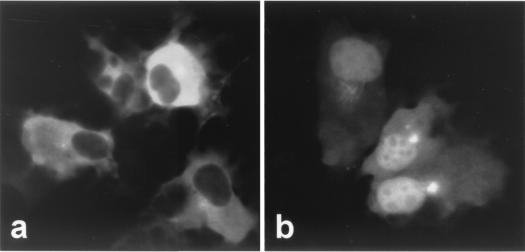

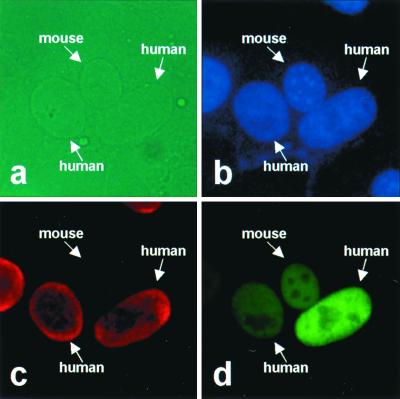

The results described above suggest that the protein shuttles between the nucleus and the cytoplasm, similar to other proteins that harbor both nuclear localization and export activities (32, 36). Thus, to demonstrate nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the BDV N protein, we used an interspecies heterokaryon assay (2, 26, 50) in which human OL cells transiently transfected with p40N were fused to mouse 3T3 cells. After fusion, the cells were fixed and stained with Hoechst 33258 and anti-primate Ku and anti-N antibodies. If nuclear export occurs, p40N should exit the human nucleus, traverse the cytoplasm, and enter the mouse nucleus. Cellular heterokaryons were identified by phase microscopy, and the mouse nucleus exhibited a characteristic speckled pattern on Hoechst staining (Fig. 5b). Anti-Ku MAb recognized only a protein of p80 subunit (Ku) presented in the human nucleus (Fig. 5c). By 2 h postfusion, p40N was seen in both the human and the mouse nuclei (Fig. 5d). As expected, p40N was not observed in unfused mouse cells (data not shown). These results indicated that the N protein of BDV functions as a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein.

FIG. 5.

BDV N shuttles between the nucleus and cytoplasm. OL cells were transiently transfected with pGFP-p40N, and the transfected cells were subjected to the interspecies heterokaryon assay as described in the text. A field of cells containing a representative interspecies heterokaryon is shown. Panels: a, phase-contrast image; b, Hoechst staining; c, anti-primate Ku (Cy3); d, anti-N (FITC).

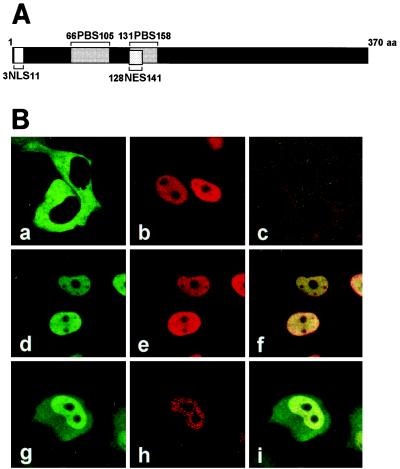

The BDV P protein prevents the nuclear export activity of p38N.

Previous studies have demonstrated that the BDV P protein contains a bipartite NLS (39, 41), and it is likely that the P protein plays a critical role in the viral replication in the nucleus by its interaction with N protein. Interestingly, one of the sites of interaction between the BDV P and N proteins, which is between amino acids 131 and 158 of the N protein (1), completely overlaps the NES region of N, i.e., amino acids 128 to 141 (Fig. 6A). Therefore, we expect that BDV P can prevent the nuclear export of N by directly binding to the NES. To address whether coexpression of the BDV P protein directly blocks nuclear export of the N protein, COS-7 cells were cotransfected with pHA-p38N and pP-Wild, and the subcellular localization of p38N was examined by staining of anti-P and anti-N antibodies. As shown in Fig. 6B, BDV p38N was completely retained in the nucleus in the presence of a higher amount of P protein (panels d and f), while increasing the ratio of p38N in the cotransfected cells (P/p38N = 1/10) led not only to the nuclear localization but also to the cytoplasmic distribution of the p38N (panels g and i). These results suggested that the BDV P protein efficiently blocks the nuclear export of p38N and retains the N protein in the nucleus by masking the NES.

FIG. 6.

BDV P prevents nuclear export of p38N. (A) Schematic presentation of functional domains within N. NLS (amino acids 3 to 11), NES (amino acids 128 to 141), which overlaps with one of the interaction domains between BDV N and P (amino acids 131 to 158), and PBS P-binding sites (amino acids 66 to 105 and 131 to 158) are shown (1). aa, amino acids. (B) Subcellular localization of BDV p38N in the presence of P by using a confocal laser-scanning microscope. COS-7 cells were cotransfected with BDV p38N and P plasmids and detected by using anti-N and -P antibodies. Panels: a, p38N plasmid-transfected cells (anti-N: FITC); b, P plasmid-transfected cells (anti-P, Cy3); c, mock-transfected cells (anti-N and -P, FITC and Cy3); d to f, p38N and P plasmid-cotransfected cells, (anti-N and -P, FITC and Cy3). p38N and P plasmids were cotransfected in the ratio of 1:1 (d to f) or 10:1 (g to i).

DISCUSSION

Nuclear export of viral nucleic acids is an important mechanism to not only viral replication but also the interaction between virus and host cells. In this report, we demonstrated that BDV N protein has nuclear export activity that is mediated by an internal NES at amino acids 128 to 141 and functions as a nucleocytoplasmic shuttling protein. This observation provides an important insight into the role of the viral nucleoprotein in the nucleocytoplasmic transport of viral RNPs.

Several NES-containing viral proteins have been identified, including the retrovirus proteins Rev and Rex (16, 32) and the influenza NS2 proteins (31). These NESs consist of a short stretch of amino acids that is rich in leucine residues (16, 31, 32). We found that the NES of BDV N also contains a canonical leucine-based sequence (Fig. 3). Four leucine or isoleucine residues are found between amino acids 128 and 141. Site-directed mutagenesis of these residues resulted in a diffused localization of GFP signals, indicating the importance of these amino acids for N export (Fig. 3). Recent studies of virus and cellular NESs have revealed that the leucine-rich sequence of NESs is recognized by several cellular proteins, including eukaryotic translation initiation protein 5A and CRM1, which binds to nucleoportins such as the GTP-bound form of Ran (Ran-GTP) (13, 27). The NES-containing protein–CRM1–Ran-GTP complex is believed to be efficiently translocated to the cytoplasm through the nuclear pore complex, mediating export of viral or cellular RNAs (13, 27, 51). Our analysis demonstrated that nuclear export of BDV NES is blocked by treatment with LMB, which directly inhibits NES-CRM1 binding, indicating that the NES of N also acts through a CRM1-dependent pathway.

Our previous study has demonstrated that BDV N bears an NLS in the region between amino acids 3 and 11 (19). This observation indicated that BDV N has two intrinsic abilities that oppose each other: nuclear localization and export activities. At present, a number of viral proteins that contain both NLS and NES have been identified, and the proteins play crucial roles in viral replication in infected cells (51). The Rev proteins of lentiviruses are responsible for the efficient export of unspliced and single spliced viral mRNAs, as well as the viral genomic RNAs, to the cytoplasm (32). The herpes simplex virus ICP27 protein also contains both nuclear transport signals and stimulates cytoplasmic export of the viral single-exon mRNAs (26, 36). These viral proteins shuttle back into the nucleus after releasing the RNAs into the cytoplasm via the function of their own NLSs. On the other hand, HIV-1 MA and influenza virus NP proteins are directly involved in nuclear transport of the virus genomic RNAs as virus structural proteins. The HIV-1 MA stimulates localization of the viral PIC to the integration site of the nucleus following the virus entry (4, 45). While, during the HIV-1 production, MA maintains the viral Gag precursor in the cytoplasm (21). It is believed that NP of influenza virus promotes the virus RNP transport in combination with other viral proteins, including M1 (9, 28, 51), although the NES region of NP has not yet been identified (9, 28). These observations indicate that the use of a virus structural protein as a carrier for nuclear transport is one of the most effective ways for viral genomic RNAs to enter and leave the nucleus. Therefore, it is most likely that BDV N contributes to the virus RNP transport via its nuclear transport signals, because N is considered to be a major component of the virus RNP complexes (7, 37). It is also possible that the RNP transport is mediated by direct or indirect interaction between the N and other virus proteins, including P and X proteins (24, 40). In fact, P also has a bipartite NLS that is composed of atypical proline-rich residues (41).

The nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins must employ switch mechanisms that change the direction of transport dependent on the viral life cycle in infected cells. The HIV-1 Rev protein is by far the best understood of the viral proteins that shuttle between the nucleus and cytoplasm. The Rev response element (RRE) contains a high-affinity binding site for the arginine-rich RNA-binding domain of Rev, which also works as an NLS of Rev (32). Thus, the nuclear localization activity of Rev is masked by the direct binding to RRE during the nuclear export (32). In addition, it has been reported that nuclear export and cytoplasmic accumulation of the influenza virus NP are stimulated by phosphorylation of the protein (28), a finding suggestive of the presence of a phosphorylation-dependent switch mechanism in viral nucleocytoplasmic shuttling proteins.

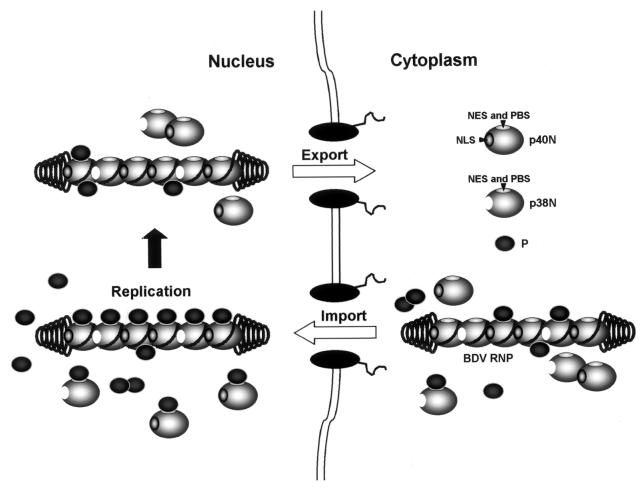

In BDV, the switch mechanism to regulate nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of the N protein may be explained by the binding to P protein and production of an N isoform lacking NLS, i.e., p38N. A previous study has demonstrated that two independent regions within the BDV N, amino acids 66 to 105 and amino acids 131 to 158, are critical for the interaction with P protein (1). Interestingly, the NES of N overlaps one of the P binding sites (Fig. 6). It is therefore possible that the nuclear export activity of BDV N is blocked by the direct binding of P to N NES. In fact, coexpression of p38N and P proteins in transiently transfected cells significantly inhibited the cytoplasmic accumulation of N (Fig. 6). Recent studies have also revealed that binding between BDV P and X proteins is carried out via a putative-NES region within the X protein (24, 52). These observations suggested that P acts as a nuclear retention factor of the N and X proteins by binding directly to the NESs (24, 52). Thus, masking of the NESs by an exceeded amount of P protein could mediate retention of the viral RNPs in the nucleus during the nuclear replication stage of the virus (Fig. 7).

FIG. 7.

Model of nucleocytoplasmic transport of BDV RNP. BDV genomic RNA is associated with multiple copies of BDV-p40N and -p38N. BDV-p40N or -P is required for import of RNP from cytoplasm to nucleus by nuclear targeting. BDV N also contains NES, which overlaps the P binding site (PBS). We postulate that the nuclear export activity of BDV N is blocked by interaction with P during its replication in the nucleus. A mechanism that triggers export of RNP to the cytoplasm after replication may also exist. Concentrations of each viral protein in the nucleus seem to play an important role as a switch mechanism of RNP export.

A mechanism that triggers N export to the cytoplasm after the replication in the nucleus may also exist. Such a switch mechanism may simply depend on the concentrations of each viral protein in the nucleus. A lower concentration of P in the nucleus can increase free NESs, mediating nuclear export of the N-containing RNP complexes (Fig. 7). On the other hand, an increased level of N could capture P protein in the nucleus, which may reduce the chance of binding of P with N in the viral RNPs. This, in turn, could also enhance nuclear export of viral RNPs (Fig. 7). In fact, we have recently demonstrated that the molecular ratio between the N and P proteins is significantly different between persistently and acutely BDV-infected cells (48).

In addition, the production of the N isoform lacking NLS in infected cells may be one of the most unique mechanisms for the transport and replication of BDV. The p38N protein would be necessary for the nuclear export and cytoplasmic accumulation of the virus RNPs. The presence of the NLS-lacking p38N protein in the N multimer would increase the relative number of NESs compared with the NLSs. Because protein transport is an active, energy-dependent, and signal-mediated process, an increase in the number of NES could enhance nuclear export of the N protein complex, resulting in accumulation of the viral RNPs in the cytoplasm for maturation or assembly of the progeny virions.

The results presented here showed that the BDV N protein has both nuclear localization and export activities that are required for viral nucleocytoplasmic shuttling. These observations provide a new insight into the mechanism of nucleocytoplasmic transport of viral RNPs in a unique nonsegmented, negative-strand RNA virus. Further studies with new techniques, such as reverse-genetic systems, are required to identify the exact roles of N protein in transporting viral RNAs during BDV infection and to improve our knowledge of protein transport in general.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Jun Katahira of this institute for helpful discussion and to Minoru Yoshida, The University of Tokyo, for the gift of the LMB.

This work was supported by the Special Coordination Funds for Science and Technology from the Science and Technology Agency (STA).

REFERENCES

- 1.Berg M, Ehrenborg C, Blomberg J, Pipkorn R, Berg A L. Two domains of the Borna disease virus p41 protein are required for interaction with the p23 protein. J Gen Virol. 1998;79:2957–2963. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-79-12-2957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Borer R A, Lehner C F, Eppenberger H M, Nigg E A. Major nucleolar proteins shuttle between nucleus and cytoplasm. Cell. 1989;56:379–390. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(89)90241-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Briese T, Schneemann A, Lewis A J, Park Y S, Kim S, Ludwig H, Lipkin W I. Genomic organization of Borna disease virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:4362–4366. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.10.4362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bukrinsky M I, Haggerty S, Dempsey M P, Sharova N, Adzhubel A, Spitz L, Lewis P, Goldfarb D, Emerman M, Stevenson M. A nuclear localization signal within HIV-1 matrix protein that governs infection of non-dividing cells. Nature. 1993;365:666–669. doi: 10.1038/365666a0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cubitt B, de la Torre J C. Borna disease virus (BDV), a nonsegmented RNA virus, replicates in the nuclei of infected cells where infectious BDV ribonucleoproteins are present. J Virol. 1994;68:1371–1381. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1371-1381.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cubitt B, Oldstone C, de la Torre J C. Sequence and genome organization of Borna disease virus. J Virol. 1994;68:1382–1396. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.3.1382-1396.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.de la Torre J C. Molecular biology of Borna disease virus: prototype of a new group of animal viruses. J Virol. 1994;68:7669–7675. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.12.7669-7675.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dupont S, Sharova N, DeHoratius C, Virbasius C M, Zhu X, Bukrinskaya A G, Stevenson M, Green M R. A novel nuclear export activity in HIV-1 matrix protein required for viral replication. Nature. 1999;402:681–685. doi: 10.1038/45272. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Elton D, Simpson-Holley M, Archer K, Medcalf L, Hallam R, McCauley J, Digard P. Interaction of the influenza virus nucleoprotein with the cellular CRM1-mediated nuclear export pathway. J Virol. 2001;75:408–419. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.408-419.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallay P, Hope T, Chin D, Trono D. HIV-1 infection of nondividing cells through the recognition of integrase by the importin/karyopherin pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:9825–9830. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.18.9825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gluzman Y. SV40-transformed simian cells support the replication of early SV40 mutants. Cell. 1981;23:175–182. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(81)90282-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalez-Dunia D, Cubitt B, Grasser F A, de la Torre J C. Characterization of Borna disease virus p56 protein, a surface glycoprotein involved in virus entry. J Virol. 1997;71:3208–3218. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.3208-3218.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gorlich D. Transport into and out of the cell nucleus. EMBO J. 1998;17:2721–2727. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Herzog S, Rott R. Replication of Borna disease virus in cell cultures. Med Microbiol Immunol. 1980;168:153–158. doi: 10.1007/BF02122849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hsu T A, Carbone K M, Rubin S A, Vonderfecht S L, Eiden J J. Borna disease virus p24 and p38/40 synthesized in a baculovirus expression system: virus protein interactions in insect and mammalian cells. Virology. 1994;204:854–859. doi: 10.1006/viro.1994.1608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim F J, Beeche A A, Hunter J J, Chin D J, Hope T J. Characterization of the nuclear export signal of human T-cell lymphotropic virus type 1 Rex reveals that nuclear export is mediated by position-variable hydrophobic interactions. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:5147–5155. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.9.5147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kliche S, Briese T, Henschen A H, Stitz L, Lipkin W I. Characterization of a Borna disease virus glycoprotein, gp18. J Virol. 1994;68:6918–6923. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.11.6918-6923.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kliche S, Stitz L, Mangalam H, Shi L, Binz T, Niemann H, Briese T, Lipkin W I. Characterization of the Borna disease virus phosphoprotein, p23. J Virol. 1996;70:8133–8137. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.11.8133-8137.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kobayashi T, Shoya Y, Koda T, Takashima I, Lai P K, Ikuta K, Kakinuma M, Kishi M. Nuclear targeting activity associated with the amino terminal region of the Borna disease virus nucleoprotein. Virology. 1998;243:188–197. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kobayashi T, Watanabe M, Kamitani W, Tomonaga K, Ikuta K. Translation initiation of a bicistronic mRNA of Borna disease virus: a 16-kDa phosphoprotein is initiated at an internal start codon. Virology. 2000;277:296–305. doi: 10.1006/viro.2000.0592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krausslich H G, Welker R. Intracellular transport of retroviral capsid components. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol. 1996;214:25–63. doi: 10.1007/978-3-642-80145-7_2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kudo N, Wolff B, Sekimoto T, Schreiner E P, Yoneda Y, Yanagida M, Horinouchi S, Yoshida M. Leptomycin B inhibition of signal-mediated nuclear export by direct binding to CRM1. Exp Cell Res. 1998;242:540–547. doi: 10.1006/excr.1998.4136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lipkin W I, Travis G H, Carbone K M, Wilson M C. Isolation and characterization of Borna disease agent cDNA clones. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:4184–4188. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.11.4184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Malik T H, Kishi M, Lai P K. Characterization of the P protein-binding domain on the 10-kilodalton protein of Borna disease virus. J Virol. 2000;74:3413–3417. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.7.3413-3417.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Malik T H, Kobayashi T, Ghosh M, Kishi M, Lai P K. Nuclear localization of the protein from the open reading frame x1 of the Borna disease virus was through interactions with the viral nucleoprotein. Virology. 1999;258:65–72. doi: 10.1006/viro.1999.9715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mears W E, Rice S A. The herpes simplex virus immediate-early protein ICP27 shuttles between nucleus and cytoplasm. Virology. 1998;242:128–137. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.9006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nakielny S, Dreyfuss G. Transport of proteins and RNAs in and out of the nucleus. Cell. 1999;99:677–690. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81666-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neumann G, Castrucci M R, Kawaoka Y. Nuclear import and export of influenza virus nucleoprotein. J Virol. 1997;71:9690–9700. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9690-9700.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Neumann G, Hughes M T, Kawaoka Y. Influenza A virus NS2 protein mediates vRNP nuclear export through NES-independent interaction with hCRM1. EMBO J. 2000;19:6751–6758. doi: 10.1093/emboj/19.24.6751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Neill R E, Jaskunas R, Blobel G, Palese P, Moroianu J. Nuclear import of influenza virus RNA can be mediated by viral nucleoprotein and transport factors required for protein import. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:22701–22704. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.39.22701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.O'Neill R E, Talon J, Palese P. The influenza virus NEP (NS2 protein) mediates the nuclear export of viral ribonucleoproteins. EMBO J. 1998;17:288–296. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.1.288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pollard V W, Malim M H. The HIV-1 Rev protein. Annu Rev Microbiol. 1998;52:491–532. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.52.1.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Popov S, Rexach M, Zybarth G, Reiling N, Lee M A, Ratner L, Lane C M, Moore M S, Blobel G, Bukrinsky M. Viral protein R regulates nuclear import of the HIV-1 pre-integration complex. EMBO J. 1998;17:909–917. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pyper J M, Gartner A E. Molecular basis for the differential subcellular localization of the 38- and 39-kilodalton structural proteins of Borna disease virus. J Virol. 1997;71:5133–5139. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5133-5139.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Pyper J M, Richt J A, Brown L, Rott R, Narayan O, Clements J E. Genomic organization of the structural proteins of borna disease virus revealed by a cDNA clone encoding the 38-kDa protein. Virology. 1993;195:229–238. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sandri-Goldin R M. ICP27 mediates HSV RNA export by shuttling through a leucine-rich nuclear export signal and binding viral intronless RNAs through an RGG motif. Genes Dev. 1998;12:868–879. doi: 10.1101/gad.12.6.868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Schneemann A, Schneider P A, Lamb R A, Lipkin W I. The remarkable coding strategy of Borna disease virus: a new member of the nonsegmented negative strand RNA viruses. Virology. 1995;210:1–8. doi: 10.1006/viro.1995.1311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schneider P A, Hatalski C G, Lewis A J, Lipkin W I. Biochemical and functional analysis of the Borna disease virus G protein. J Virol. 1997;71:331–336. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.1.331-336.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schwemmle M, Jehle C, Shoemaker T, Lipkin W I. Characterization of the major nuclear localization signal of the Borna disease virus phosphoprotein. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:97–100. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-1-97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Schwemmle M, Salvatore M, Shi L, Richt J, Lee C H, Lipkin W I. Interactions of the Borna disease virus P, N, and X proteins and their functional implications. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:9007–9012. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.15.9007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Shoya Y, Kobayashi T, Koda T, Ikuta K, Kakinuma M, Kishi M. Two proline-rich nuclear localization signals in the amino- and carboxyl-terminal regions of the Borna disease virus phosphoprotein. J Virol. 1998;72:9755–9762. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.12.9755-9762.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Takebe Y, Seiki M, Fujisawa J, Hoy P, Yokota K, Arai K, Yoshida M, Arai N. SR α promoter: an efficient and versatile mammalian cDNA expression system composed of the simian virus 40 early promoter and the R-U5 segment of human T-cell leukemia virus type 1 long terminal repeat. Mol Cell Biol. 1988;8:466–472. doi: 10.1128/mcb.8.1.466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Thiedemann N, Presek P, Rott R, Stitz L. Antigenic relationship and further characterization of two major Borna disease virus-specific proteins. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:1057–1064. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-5-1057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Thierer J, Riehle H, Grebenstein O, Binz T, Herzog S, Thiedemann N, Stitz L, Rott R, Lottspeich F, Niemann H. The 24K protein of Borna disease virus. J Gen Virol. 1992;73:413–416. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-73-2-413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.von Schwedler U, Kornbluth R S, Trono D. The nuclear localization signal of the matrix protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 allows the establishment of infection in macrophages and quiescent T lymphocytes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:6992–6996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.15.6992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Walker M P, Jordan I, Briese T, Fischer N, Lipkin W I. Expression and characterization of the Borna disease virus polymerase. J Virol. 2000;74:4425–4428. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4425-4428.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wang P, Palese P, O'Neill R E. The NPI-1/NPI-3 (karyopherin α) binding site on the influenza a virus nucleoprotein NP is a nonconventional nuclear localization signal. J Virol. 1997;71:1850–1856. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.1850-1856.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Watanabe M, Zhong Q, Kobayashi T, Kamitani W, Tomonaga K, Ikuta K. Molecular ratio between Borna disease viral-p40 and p24 proteins in infected cells determined by quantitative antigen capture ELISA. Microbiol Immunol. 2000;44:765–772. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.2000.tb02561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wehner T, Ruppert A, Herden C, Frese K, Becht H, Richt J A. Detection of a novel Borna disease virus-encoded 10 kDa protein in infected cells and tissues. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:2459–2466. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-10-2459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Whittaker G, Bui M, Helenius A. Nuclear trafficking of influenza virus ribonucleoproteins in heterokaryons. J Virol. 1996;70:2743–2756. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.2743-2756.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Whittaker G R, Helenius A. Nuclear import and export of viruses and virus genomes. Virology. 1998;246:1–23. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wolff T, Pfleger R, Wehner T, Reinhardt J, Richt J A. A short leucine-rich sequence in the Borna disease virus p10 protein mediates association with the viral phospho- and nucleoproteins. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:939–947. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-4-939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]