Abstract

Food environment changes in low- and middle-income countries are increasing diet-related noncommunicable diseases (NCDs). This paper synthesizes the qualitative evidence about how family dynamics shape food choices within the context of HIV (Prospero: CRD42021226283). Guided by structuration theory and food environment framework, we used best-fit framework analysis to develop the Family Dynamics Food Environment Framework (FDF) comprising three interacting dimensions (resources, characteristics, and action orientation). Findings show how the three food environment domains (personal, family, external) interact to affect food choices within families affected by HIV. Given the growing prevalence of noncommunicable and chronic diseases, the FDF can be applied beyond the context of HIV to guide effective and optimal nutritional policies for the whole family.

Keywords: Qualitative evidence synthesis, Family food environment, Low- and middle-income countries, HIV, Family dynamics, Drivers of food choice

Highlights

-

•

Family is an important medium connecting the external and personal food environment (FE) domains.

-

•

Family dynamics enable and/or restrict food choices in HIV-affected households.

-

•

Including family dynamics in the FE is applicable to other diet-related NCDs.

-

•

This family dynamics food environment framework can be used to optimize policies and intervention toward nutritious food choice that is effective for the whole family.

1. Introduction

The food environment, where people procure food, shapes food choices, dietary patterns, and nutrition outcomes. Macrolevel factors such as globalization and urbanization shifted food environments toward cheap, convenient, energy-dense, salty, and sugary foods. These factors and associated shifts in food choices create a significant dietary risk for noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) (Delobelle, 2019; Juul et al., 2021; Reardon et al., 2021; Turner et al., 2020; Barrett et al.; Battersby and Watson, 2018). Globally, poor diets are the fifth leading cause of mortality. As such, food environments and choices – how and why people choose foods – have gained considerable attention in policies.

Using Turner's framework, the food environment in low- and middle-income countries can be conceptualized as two major interacting domains, the external and personal, each with describing factors related to food procurement and consumption that drive food choices (Turner et al., 2020; Turner et al., 2018). The external domain includes food availability, prices, vendor and product properties, marketing, and regulations, while the personal domain includes accessibility, affordability, convenience, and desirability. However, this framework does not account for family dynamics.

Expanding the scope of the food environment framework to incorporate family dynamics can offer valuable insights for designing effective family-based interventions and structure policies for optimal family health outcomes, especially among those affected by chronic diseases. Family plays an essential role in managing chronic diseases, especially the family members of people living with Human Immunodeficiency Virus (PLHIV) (Belsey, 2006; Aga et al., 2014; Weiser et al., 2011; Naidu and Harris, 2005; Iwelunmor et al., 2008). Here, family is defined as “any configurations of people who regularly eat together, eat from the same household food resources, and who mutually influence decisions about their family” (Gillespie and Gillespie, 2007). HIV, with improved prevention and treatment, is now considered to be a chronic disease. However, changes in inflammation and fat deposition from treatment make PLHIV more vulnerable to diet-related non-communicable diseases, known as the HIV-related NCDs syndemic (Graff, 2021; Kamkuemah et al., 2021; Popkin, 2006; Patel et al., 2018). Thus, dietary risk factors and the family dynamics affecting food choices, are essential to preventing and managing NCDs.

There are well-established linkages between HIV disease progression, food access, and family support (Belsey, 2006; Aberman et al., 2014). HIV intervention efforts have prioritized food assistance and supplementation interventions alongside HIV treatment because of the bidirectional linkages between disease progression and household food security (Weiser et al., 2011; Anema et al., 2014; Ivers et al., 2009). While the personal and external domains of the food environment are pertinent for households with a PLHIV, accounting for the familial factors shaping the food choices of PLHIV and their family members is needed. We propose integrating a family food environment domain into Turner's framework to show how this domain also shapes the food choices of PLHIV (Turner et al., 2020; Turner et al., 2018; Giddens, 1991; Anthony, 1984).

Using a systematic qualitative evidence synthesis (QES), we aim to demonstrate interactions among the agency of personal food environments and the economic, cultural, religious, and gender structure of the external food environment through the family (Giddens, 1991; Anthony, 1984; Slater et al., 2012; Sobal and Bisogni, 2009). We posit that the family is an important intermediary where structures converge to operationalize the development of habitual food choices and consumption practices. Structural changes will lead to new individual and family routines and rituals and, thus, establish new systems of practices. In the context of a chronic disease diagnosis, such as HIV, the family food environment can (mal)adapt to accommodate or bound food choices and create new food routines (Boncyk et al., 2022).

2. Methods

We conducted a qualitative evidence synthesis (QES; Prospero registration: CRD42021226283), a review methodology for rigorous and systematic appraisal and synthesis of qualitative research (Cooke et al., 2012; Flemming and Noyes, 2021). This review aimed to describe and conceptualize the family food environment and explore the family's role in PLHIV food choices, including food acquisition decision-making, preparation, allocation, consumption, and other dietary-related practices (Carroll et al., 2013; Thomas and Harden, 2008). The quality of the articles was evaluated independently by two reviewers using the Critical Appraisals Skills Programme (CASP) tool and confirmed by two different reviewers (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, 2018).

2.1. Search strategy

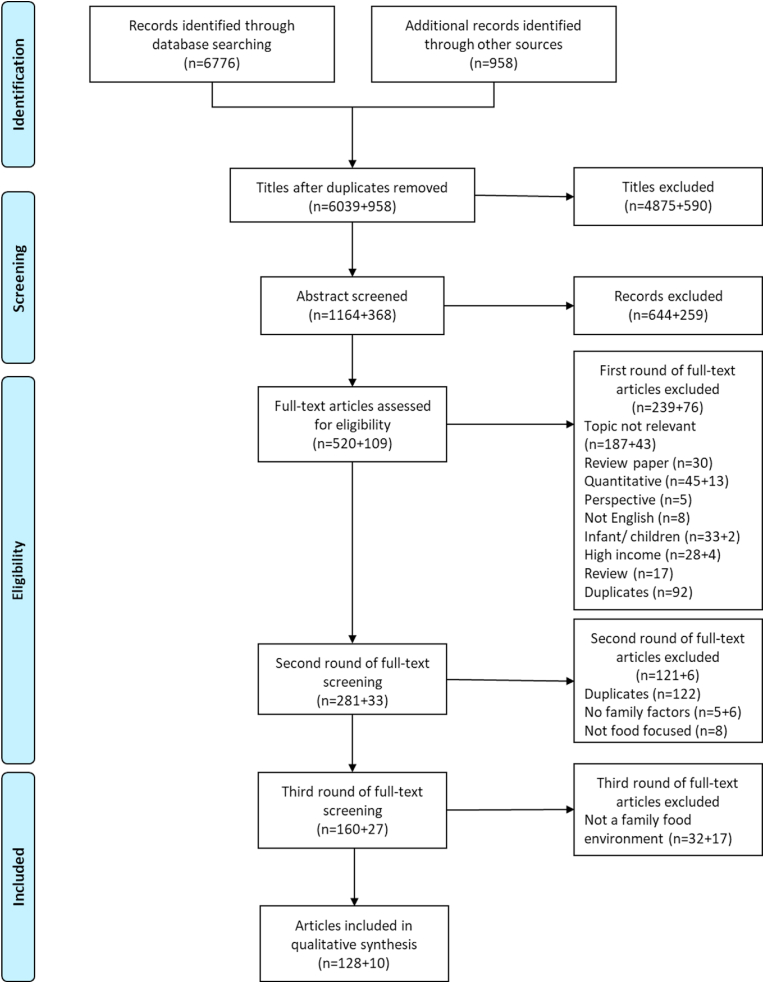

We searched PubMed, Scopus, and Web of Science with the following keywords and limited word search to qualitative studies filters: “Food and HIV”, “HIV and nutrition”, “HIV and caregiver”, “HIV and family”, “HIV and eating”, “HIV and family”. Two additional searches were conducted, first with a restricted filter “Human, AIDS, Adults” using the following keywords: “Food and Culture”, “Food and Choice”, “Food and consumption”, and “Food and insecurity.” Additionally, we identified 23 review articles during the screening process and searched the references cited in these reviews. Our systematic search yielded 6,783 non-duplicate articles. Two reviewers (RA, MB) independently screened 10% of articles for agreement on title, abstract, and three rounds of full-text screening before independently screening the remaining articles. In the first round of full-text screening, we confirmed the eligibility criteria. In the second round, we identified family-level factors influencing PLHIV food intake and developed a key concepts matrix using grounded theory and a priori coding based on Turner's food environment framework (Turner et al., 2020; Turner et al., 2018). Finally, in the third and final rounds, we ensured that included studies contributed to the Family Dynamic Framework. We used the Colandr web application to organize the screening process (Kahili-Heede and Hillgren, 2021). This search includes articles published from 1985 to 2020.

2.2. Screening

Screening inclusion criteria for articles were as follows: 1) studies conducted in LMIC as defined by the World Bank (2019 definition), 2) qualitative methodology, and 3) content related to HIV and food, including HIV stigma, caregiver burden, food access and availability, food security, food and treatment, food sources, body perception, gender differences/inequality/roles, children caring for HIV parent(s), medication adherence, poverty, disclosure, barriers, basic resources, body image/changes, and sexual transactions. In the second round of full-text screening, we specifically examined how HIV influenced food choices at the family level. The family level was defined as how family or household-level factors affect PLHIV food intake, food acquisition (purchasing, borrowing, production), and food preparation and consumption decision-making. Articles were excluded if the content was on the pediatric HIV population, such as grandparents caring for HIV child orphans and HIV maternal care/breastfeeding. Sixteen articles were excluded because we could not access the full texts.

2.3. Data extraction, analysis, and synthesis

Each included study was treated as a transcript. We used the best-fit framework synthesis approach to assess and build on Turner's food environment framework (Turner et al., 2020; Turner et al., 2018; Giddens, 1991; Anthony, 1984; Slater et al., 2012). A best-fit framework synthesis is an analytical approach that builds or tests an existing framework (in this case, food environment framework) with new qualitative synthesis like thematic analyses. A family food environment refers to any factors that affect food choice, acquisition, preparation, consumption, or family members' practices related to food choices of PLHIV. We began the analysis with a set of a priori themes and codes based on the guiding framework and theory: external, personal, and family food environment. We applied open, axial, and selective coding to identify additional constructs, determine relationships between them, and integrate codes for a deeper understanding of overarching themes. Data not easily accommodated within the framework required iterative interpretation; therefore, we also used inductive analysis techniques to synthesize the data and expand the framework (Suri, 2013). We integrated insights from both the a priori codes and emergent constructs to understand the dynamics around food in households affected by HIV.

Data extraction was completed systematically and cross-validated by two authors (RA, MB) and with a weekly discussion of each full-text screened article with the senior author (CP). We extracted the profile information, including the author's name, publication date, study design, and location for each article. First, data were extracted and placed in a matrix based on key concepts. Then they were categorized into personal (body image, food preferences, hunger), family (prioritizing PLHIV, nutrition knowledge, caregiver burden, disclosure, gender difference, financial, social network, food security), and distal (external, food aid, environment) factors and coded in MAXQDA and Excel. Factors such as affordability, accessibility, and convenience were coded as family food environment if they explicitly referred to the family level. Second, given the high prevalence of articles on food security and financial burden and existing literature on HIV and food security (Weiser et al., 2011), we assessed these articles separately to examine how they clustered with the food environment framework. Lastly, after conceptualizing the family food environment domain with three distinct sub-dimensions, the tagged articles on food security experience were re-read and coded guided by the new family domain.

After screening three databases and 23 review articles, 6783 articles were included in this review. After title screening, 1532 abstracts were screened. Among those abstracts, 629 articles moved to three rounds of full-text screening (described above). The final review included 138 full texts (Fig. 1). Articles were primarily from Africa (n = 132), with less than 10% from Southeast Asia (n = 10), Latin American (n = 11), or Caribbean (n = 11) regions (Supplemental Figure 1). Publication dates ranged from 1993 to 2020, with 68% of articles published after 2009 (Table 1). Of the 138 included articles, 110 employed structured or in-depth interviews (IDIs), 56 focus group discussions (FGDs), and 61 relied on multiple methods (FGDs, IDIs, observations, case studies, diary entries, photovoice).

Fig. 1.

study review process.

Table 1.

Descriptive characteristics of the included articles and matrix of family food environment identified in the included articles (N = 138).

| Study | Study location | Qualitative data type | Resources |

Characteristics |

Action orientation |

Health Context |

||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social capital | Resource allocation | Household wealth | Time use | Composition |

Household health status |

Household Size | Support | Value negotiations |

Impact on livelihoods Livelihoods |

Healthcare | Community Support | Acceptance | Nutrition awareness | |||||||

| Generations | Gender | Aging | Co-morbidities | Chronic Diseases | Competing basic needs | Family desirability | ||||||||||||||

| Aga et al., 2009a | Ethiopia | SSIs, observations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Aga et al., 2009b | Ethiopia | SSIs, observations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Aga et al., 2014 | Ethiopia | IDIs, observations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Agbonyitor, 2009 | Nigeria | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Alemu et al., 2013 | Ethiopia | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Alomepe et al., 2016 | Cameroon | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Amurwon et al., 2017 | Uganda | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Andersen, 2012 | Kenya | IDIs, FGDs, observations, drama, diaries | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Aransiola et al., 2014 | Nigeria | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Araujo et al., 2018 | Brazil | SSIs | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Asgary et al., 2013, Asgary et al., 2013 | Ethiopia | Interviews, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Atukunda et al., 2017 | Uganda | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Atuyambe et al., 2014 | Uganda | SSIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Axelsson et al., 2015 | Lesotho | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Ayieko et al., 2018 | Kenya, Uganda | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Balaile et al., 2007 | Tanzania | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Balcha et al., 2011 | Ethiopia | SSIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Baylies, 2002 | Zambia | Interviews | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Beckett et al., 2016 | Haiti | FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Bezabhe et al., 2014 | Ethiopia | SSIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Bindura-Mutangadura, 2001 | Zimbabwe | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Braathen et al., 2016 | Malawi | IDIs, observations (home, clinic), case study | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Burgess and Campbell, 2014 | South Africa | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Byron et al., 2008 | Kenya | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Campbell et al., 2011 | Zimbabwe | SSIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Chazan, 2014 | South Africa | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Conroy et al., 2018 | Malawi | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Crane et al., 2006 | Uganda | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Czaicki et al., 2017 | Tanzania | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| deGraft et al., 2002 | Zimbabwe | SSIs, observations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Derose et al., 2017 | Dominican Republic | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Dinh et al., 2018 | Vietnam | Interviews | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Dovel and Thomson, 2016 | Uganda | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Du and Lekganyane, 2010 | South Africa | Group IDIs, observations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Dworkin et al., 2013 | Kenya | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Fielding-Miller et al., 2014 | Swaziland | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Gebremariam et al., 2010 | Ethiopia | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Gombachika et al., 2014 | Malawi | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Goudge and Ngoma, 2011 | South Africa | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Gwatirisa and Manderson, 2009 | Zimbabwe | IDIs, FGDs, observations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Hardon et al., 2007 | Botswana, Tanzania, Uganda | SSIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Hatcher et al., 2020 | Kenya | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Herce et al., 2014 | Malawi | SSIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Holzemer et al., 2007 | Lesotho, Malawi, South Africa, Swaziland, Tanzania | FGDs | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Horn and Brysiewicz, 2014 | South Africa | Interviews | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Hussen et al., 2014 | Ethiopia | IDIs, observations, photovoice sessions, group discussion | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Iwelunmor et al., 2008 | South Africa | FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Jones et al., 2009 | Zambia | FGDs | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Jones, 2011 | South Africa | SSIs, interviews informal, observations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Kaler et al., 2010 | Uganda | Interviews | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Kalofonos, 2010 | Mozambique | SSIs, observations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Kang'ethe, 2009a | Botswana | Interviews, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Kang'ethe, 2009b | Botswana | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Kebede and Haidar, 2014 | Ethiopia | FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Kellett and Gnauck, 2017 | Uganda | Interviews, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| King et al., 2018 | South Africa | SSIs, observations (clinic) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Kipp et al., 2007 | Uganda | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Klunklin and Greenwood, 2005 | Thailand | Interviews, observations (home) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Knight et al., 2016 | South Africa | SSIs, observations (home) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Kohli et al., 2012 | India | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Kuteesa et al., 2012 | Uganda | IDIs, FGDs, observations (clinic) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Laker and Ssekiboobo, 2003 | Uganda | FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Li et al., 2008 | China | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Linda, 2013 | South Africa | IDIs, interviews informal, FGDs, observations (home) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Majumdar and Mazaleni, 2010 | South Africa | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Makoae, 2011 | Lesotho | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Mangesho, 2011 | Tanzania | Interviews formal and informal, group discussions, observations (meetings, clinic) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Martin et al., 2011 | Latin America and Caribbean | SSIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Maughan-Brown et al., 2019 | South Africa | FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Mendelsohn et al., 2014 | Kenya, Malaysia | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Mill and Anarfi, 2002 | Ghana | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Miller and Tsoka, 2012 | Malawi | SSIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Miller et al., 2011 | Uganda | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Mkandawire et al., 2015 | Malawi | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Mkandawire-Valhmu et al., 2013 | Kenya, Malawi | SSIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Mooney et al., 2017 | South Africa | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Moore and Williamson, 2003 | Togo | Interviews | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Moyo et al., 2017 | Zimbabwe | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Mshana et al., 2006 | Tanzania | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Mukumbang et al., 2017 | Zambia | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Musumari et al., 2013 | Democratic Republic of Congo | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Nachega et al., 2006 | South Africa | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Nagata et al., 2012 | Kenya | SSIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Naidu and Sliep, 2012 | South Africa | Interviews unstructured | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Nam et al., 2008 | Botswana | IDIs | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Nankwanga et al., 2009 | Uganda | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Ngamvithayapong-Yanai et al., 2005 | Thailand | IDIs, observations (home) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Nkosi et al., 2006 | Democratic Republic of Congo | FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Nsimba et al., 2010 | Tanzania | SSIs, FGDs, observations | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Ogunmefun and Schatz, 2009 | South Africa | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Okoror et al., 2013 | Nigeria | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Olenja, 1999 | Kenya | Interviews, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Olsen et al., 2013a | Ethiopia | IDIs, observations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Olsen et al., 2013b | Ethiopia | Interviews informal, FGDs, observations (home) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Oluwagbemiga, 2007 | Nigeria | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Orner, 2006 | South Africa | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Palar et al., 2013 | Bolivia | SSIs | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Pallangyo and Mayers, 2009 | Tanzania | SSIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Parker et al., 2009 | Uganda | SSIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Paz-Soldán et al., 2013 | Peru | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Raniga and Simpson, 2010 | South Africa | SSIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Rodas-Moya et al., 2016 | Malawi | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Rodas-Moya et al., 2017 | Thailand | IDIs | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Rödlach, 2009 | Zimbabwe | SSIs, FGDs, observations (home) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Root, 2010 | Swaziland | SSIs | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Rowe et al., 2005 | South Africa | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Russell et al., 2016 | Uganda | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Salter et al., 2010 | Vietnam | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Samuels and Rutenberg, 2011 | Kenya, Zambia | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Sanjobo et al., 2008 | Zambia | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Schatz, 2007 | South Africa | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Schatz and Gilbert, 2012 | South Africa | SSIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Schatz et al., 2011 | South Africa | SSIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Schatz et al., 2019 | Uganda | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Scott et al., 2014 | Zimbabwe | Interviews, FGDs, observations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Seeley et al., 1993 | Uganda | Interviews informal, observations | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Selman et al., 2013 | Kenya, Uganda | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Sileo et al., 2016 | Uganda | FGDs | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Sisya, 2010 | Zambia | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Ssengonzi, 2007 | Uganda | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Tanyi et al., 2018 | Cameroon | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | |||||||||||||||||

| Thomas, 2006 | Namibia | Diaries | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Tshililo and Davhana-Maselesele, 2009 | South Africa | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Tuller et al., 2010 | Uganda | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| VanTyler and Sheilds, 2015 | Kenya | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Wacharasin and Homchampa, 2008 | Thailand | IDIs, FGDs, obervations (home, clinic) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Ware et al., 2009 | Nigeria, Tanzania, Uganda | IDIs, observations (clinic) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||

| Watt et al., 2009 | Tanzania | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Webel et al., 2017 | Botswana | FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Weiser et al., 2010 | Uganda | SSIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Weiser et al., 2017 | Kenya | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Williams and McGill, 2011 | Mozambique | IDIs, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Wright et al., 2012 | Uganda | SSIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Xie et al., 2017 | China | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Yager et al., 2011 | Uganda | IDIs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Yakob and Ncama, 2016 | Ethiopia | IDIs, FGDs, case study | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Yizengaw et al., 2013 | Ethiopia | Interviews, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Zembe et al., 2013 | South Africa | Interviews, FGDs | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| IDIs = in-depth interviews; FGDs = focus group discussions; SSIs = semi-structured interviews | ||||||||||||||||||||

3. Results

Nearly all articles used appropriate qualitative methodology (98%) and explicitly stated the research aim of the study (96%). Most articles adequately detail participant recruitment (92%) and data collection (98%). A fifth (19%) of articles did not consider the relationship between the researcher and participants, and a third (32%) did not indicate ethical consideration. Quality assessments of the articles are summarized in Supplemental Table 1.

Family Food Environment Domain.

We hypothesized that the family food environment domain would be an intermediary between Turner's external and personal food environment domains (Turner et al., 2020; Turner et al., 2018). This family domain captures how the external food environments, rules, and rituals, also termed structures, bind and expand agency to affect the food choices of the personal food environment (Turner et al., 2020; Giddens, 1991). From the synthesis of 138 articles, we expanded the original framework to derive the Family Dynamics Framework (FDF) (Turner et al., 2018). FDF is characterized by: 1) resources available, 2) family characteristics, and 3) the action orientation of the family, which occurs within 4) a health context (Fig. 2). Each of the three dimensions includes several factors (defined in Table 2) that function independently and interact to influence family-level food choices that affect individual food choices within a household. Results are organized by how the family domain functions to enable and bind choices along with a summary of illustrative quotes and references for each factor (Table 3).

Fig. 2.

The Family Dynamics Framework (FDF) is theoretically informed (Giddens, 1991; Anthony, 1984) and expands existing frameworks (Turner et al., 2020; Turner et al., 2018) to show the additional family food environment domain and associated dimensions related to drivers of food choice in the context of families affected by HIV.

Table 2.

Definition of the family food environment domain, dimension, factor, sub-factor within the Family Dynamics Framework (FDF).

Family food environment domain: essential intermediary between external and internal food environment that captures how the structures (external food environments, rules, and rituals) bound and expand agency intersection to affect the food choices of the personal food environment.

| Dimension | Factor | Sub-factor |

|

Resources: Pooled materials and resources related to food acquisition and preparation that affect food choices |

Social capital: Social network, support, and trust that bond, bridge, and link PLHIV and their family with a network (neighbors, extended family, work) and affects preferred food allocation toward a PLHIV | |

| Resource allocation: How households pool, divide and distribute food quantity and quality | ||

| Household wealth: Financial capital and assets available within a household | ||

|

Time use: Time lost when PLHIV no longer participates in labor and household chores as well as the time that a family member spends on caring for the PLHIV |

||

|

Characteristics: Composition that affects resources and decision-making regarding food preferences and how these factors affect PLHIV and family member's food choices and consumption patterns |

Composition: Family members of different ages, generations, and genders residing in the same complex, whether under the same roof, within a shared compound, or in adjacent dwellings, influencing the dynamic of food choice | Generations: How multigenerational, extended, female- or male-headed households and children impacted food choices |

| Gender: Social roles ascribed to men and women impact food choice | ||

| Aging: Increased health risks and additional support that PLHIV need later in life | ||

| Household Health Status: Disease navigation or how the family and PLHIV make food decisions | Co-morbidities: Co-occurring morbidities besides their HIV diagnosis that require additional care and a tailored diet | |

| Chronic diseases: Morbidities among other family members | ||

|

Household Size: Number of family members affecting the food choices of the PLHIV and household members |

||

|

Action orientation: Strategies and observable acts affecting food allocation decisions and diets of PLHIV |

Support: Family factors that enable food choices of PLHIV and their family members | |

|

Value negotiations: Factors that compete with individual preferences within the family |

Competing basic needs: Prioritizing one family member over another when household resources are scarce, thereby impacting the well-being of family members | |

|

Family desirability: Balancing all family food preferences and needs while accounting for norms related to religion, ethnicity, culture, or region | ||

| Health Context: How the FDF fits within the chronic disease of focus | Impact on livelihoods: Lost income due to disease management of an individual with a chronic disease and their family members | |

| Healthcare: Burden associated with disease treatment, including hidden costs such as clinic transportation, waiting time, and testing, and how these healthcare burdens impact food choices | ||

| Community support: Structural networks, hospital, and organized community groups an individual with a chronic disease can rely on to support their food choices | ||

| Acceptance: How the household's awareness of the chronic disease status and their demonstration of acceptance through the levels of support they provide | ||

| Nutritional awareness: How the family domain worked to optimize the personal food environment by enabling healthier food choices for an individual with a chronic disease when family members are aware of the person's nutritional needs |

Table 3.

Supportive quotes of subdimensions of the Family Dynamics Framework (FDF).

| 1. RESOURCES |

|---|

| Social capital |

|

|

|

| Resource allocation |

|

|

| Household wealth |

|

| Time use |

|

| 2. CHARACTERISTICS |

|---|

| Composition |

| Generations |

|

|

| Gender |

|

| Aging |

|

|

| Household Health Status |

| Co-morbidities |

|

| Chronic diseases |

|

|

|

| Household size |

|

| 3. ACTION ORIENTATION |

|---|

| Support |

|

|

|

|

| Value negotiations |

| Competing basic needs |

|

|

|

| Family desirability |

|

| 4. HEALTH CONTEXT |

|---|

| Impact on livelihoods |

|

|

|

|

|

| Healthcare |

|

| Community support |

|

| Acceptance |

|

|

|

|

| Nutritional awareness |

|

|

|

3.1. Resources is the pooled materials and resources related to food acquisition and preparation that affect food choices, including social capital, resource allocation, household wealth, and time use

Social capital refers to the social network, support, and trust (Ferlander, 2007) that bond, bridge, and link PLHIV and their family with a network (neighbors, extended family, work) and affects preferred food allocation toward a PLHIV (38% of articles). Family members within the household and extended family both contribute to and benefit from this social capital. Food was a common medium for operationalizing social capital. To enable the food choices of PLHIV, PLHIV and their families often described reliance on social networks such as extended family members, including adult children living outside the home, and those built through social relationships, such as neighbors and friends (Table 3: 1.1a-b) (Hardon et al., 2007). Adult children of PLHIV living outside the household provided food or money for their HIV-related needs. Prior social relationships with food vendors and neighbors allowed PLHIV to borrow from vendors when necessary (Table 3: 1.1c) (Ware et al., 2009).

Resource allocation refers to how households pool, divide, and distribute food quantity and quality (33% of articles). In low-income settings, food allocation decisions were based on energy expenditure, gender, household composition, and competing family needs. Five articles reported that family members prioritized higher food quality for PLHIV without expecting that they would share it with others (Table 3: 1.2a) (Mangesho, 2011). PLHIV found it hard not to share with other family members, especially children (Table 3: 1.2b) (Moyo et al., 2017; Olsen et al., 2013a; Kebede and Haidar, 2014; Czaicki et al., 2017). One study reported variability in who was prioritized by workload seasonality (Mangesho, 2011); larger meals were allocated to family members doing heavy farm work rather than prioritizing the PLHIV and young children (Mangesho, 2011). Aging family members were also prioritized because of cultural practices of respect and kinship (Schatz, 2007; Schatz et al., 2011). Along with familial caregiving cultural expectations, household composition variations were essential factors in food choice and resource allocation among PLHIV households.

Household wealth refers to the financial capital and assets available within a household (26% of articles). Often, PLHIV families discussed the bi-directional relationship between food security and financial capacity to meet PLHIV needs (Chazan, 2014). Loss of livelihood and lack of remittances were the main economic shocks for the families as they juggled to meet the recommended diet and finances for HIV-related expenses (Moyo et al., 2017; King et al., 2018; Dovel and Thomson, 2016; Mill and Anarfi, 2002). Families discussed the socioeconomic barriers that reduced food consumption resources (Webel et al., 2017) and the competing cooking fuel costs for making special foods for the PLHIV (Beckett et al., 2016; Aga et al., 2009a; Ogunmefun and Schatz, 2009; Zembe et al., 2013). Families had to account for PLHIV's nutritional needs within the broader family budget (Table 3: 1.3) (Moyo et al., 2017). Additional wealth made hardships easier to handle as most families affected by HIV described a tremendous loss of labor of the PLHIV. In addition to food preparation and general care, the labor-intensive task of fetching water was described by PLHIV as furthering their dependency on others (Schatz, 2007). Their family caregiver and wealthier families could ease this burden by paying for care or labor assistance.

Time use refers to the time lost when PLHIV no longer participates in labor and household chores as well as the time that a family member spends on caring for the PLHIV (17% of articles). Time use negatively impacts household productivity (paid and unpaid) and well-being and affects food provisioning since family members use their time differently to ensure a PLHIV is cared for. In one study, participants observed that “the affected household may work daily, but the time is somehow shortened because they also have to care for the sick person” (Parker et al., 2009). The time use factor impacts varied by socio-economic status, and families affected by HIV described the heavy caregiving time burdens associated with providing special foods and the effects on daily routines and labor (Table 3: 1.4) (Parker et al., 2009; Kaler et al., 2010; Pallangyo and Mayers, 2009).

3.2. Characteristics refers to the composition that affects resources and decision-making regarding food preferences and how these factors affect PLHIV and family members’ food choices and consumption patterns. We found that food choices depended on family and/or household composition (generations, gender, aging), household health status (co-morbidities, chronic diseases), and household size

Composition refers to family members of different ages, generations, and genders residing in the same complex, whether under the same roof, within a shared compound, or in adjacent dwellings, influencing the dynamic of food choice. Generations refer to how multigenerational, extended, female- or male-headed households and children impacted food choices (42% of articles). An HIV diagnosis was often associated with a reshuffling that changed the dynamics within the composition. Older parents cared for their adult children with HIV as well as their young grandchildren. Recently widowed women impacted by HIV often moved to live with their parents for support with food and care (Table 3: 2.1a) (Nagata et al., 2012; Ssengonzi, 2007; Klunklin and Greenwood, 2005). Food consumption and choice were affected by age, marital status, and the number of children in the household (Table 3: 2.1b) (Nagata et al., 2012; Conroy et al., 2018; Weiser et al., 2010). A consistent cross-cutting theme was sharing food aid with children. Within multigenerational households, family food choices reflected a balancing act that aimed to meet the needs of children and the PLHIV (Klunklin and Greenwood, 2005).

Gender refers to how social roles ascribed to men and women impact food choices (36% of articles). The gender of the PLHIV influenced food allocation and choices within the household. The prioritization of the well-being and diets of PLHIV who are men focused on supporting them to recover and return to work, while PLHIV who are women received less family support (Kohli et al., 2012). The gender of the caregiver influenced the caregiving role and responsibilities for the household member with HIV. Women were considered the family's primary caregivers and food providers (Table 3: 2.2) (Davis and Kostick, 2018; Baylies, 2002), and thus served as caregivers for both the PLHIV in the family (Ssengonzi, 2007; Weiser et al., 2010; Seeley et al., 1993).

“Women and men both experienced significant food insecurity, but men were at times favored in terms of food distribution within the household. As explained by one HIV-positive widow: ‘Before you get married, your parents tell you that you're supposed to feed your husband, that he must eat more food. So when I got to my husband's home, whether I was sick or anything, he must have more food according to what I was told.’” (Weiser et al., 2010)

Williams and colleagues found that the impact of prioritization of men with HIV centered on meeting their immediate needs, so they consumed healthy diets (Williams and McGill, 2011). When the PLHIV was a woman, the focus was on long-term factors, family livelihoods, and psychological relief (Williams and McGill, 2011).

Aging refers to the increased health risks and additional support that PLHIV need later in life (8% of articles). In these articles, a common theme was that older people with HIV required more care, medications, food, and support for daily activities. They often had multiple co-morbidities, especially mental health, stigma, and a need for social support and financial security. As PLHIV age, there is a need for more significant support for daily living activities, such as cooking and fetching water (Table 3: 2.3a) (Wright et al., 2012). When an HIV diagnosis came later in life, aging PLHIV experienced stigma related to HIV and ageism (Araujo et al., 2018). Together, this dual stigma among the older PLHIV population led to high rates of non-disclosure and social withdrawal (Table 3: 2.3b) (Wright et al., 2012; Araujo et al., 2018).

Household health status refers to disease navigation or how the family and PLHIV make food decisions, comprised of co-morbidities of the PLHIV (12% of articles) and chronic diseases among other family members (7% of articles). PLHIV often have co-occurring morbidities, such as tuberculosis, hypertension, and diabetes, that require additional care and a tailored diet (Table 3: 2.4) (Webel et al., 2017). Families faced greater difficulty enabling PLHIV's food choices when other family members had chronic diseases. Family caregivers indicated high stress burdens affecting their mental well-being (Table 3: 2.5a-b) (Czaicki et al., 2017; Hatcher et al., 2020). Among both PLHIV and their family members, stressors associated with health and well-being made enhancing disease treatment through food access and choice more difficult (Table 3: 2.5c) (Pallangyo and Mayers, 2009).

Household size refers to the number of family members affecting the food choices of the PLHIV and household members (7% of articles). Themes focused on how PLHIV shared food aid with other household members (Table 3: 2.6) (Kalofonos, 2010), particularly children and neighbors, and how this pooling of resources meant there was less food available for the PLHIV (Schatz et al., 2011; Chazan, 2014; Dovel and Thomson, 2016; Aga et al., 2009a; Pallangyo and Mayers, 2009; Kalofonos, 2010; Rodas-Moya et al., 2016; Byron et al., 2008; Russell et al., 2016; Raniga and Simpson, 2010).

3.3. Action orientation refers to strategies and observable acts affecting food allocation decisions and diets of PLHIV. The strategies and acts are contingent on family support (or lack of it due to stigma) and value negotiations due to competing basic needs and family food preferences

Support refers to family factors that enable the food choices of PLHIV and their family members (68% of articles). The level of family support affects PLHIV food choices and acts along a continuum that varies over time. Continuous support played a significant role in overcoming stigma and supporting food preferences of PLHIV (Aransiola et al., 2014; Xie et al., 2017), “My mother told me to treat myself; if I [want] special foods, to just buy and eat them” (Xie et al., 2017). In resource-constrained contexts, families could often only provide intermittent support, often unpredictable and unreliable based on livelihood opportunities. They described stepping in at times of greater need, such as greater disease severity (Table 3: 3.1a) (Paz-Soldán et al., 2013), through the provision of money and food from their adult children or extended family (Table 3: 3.1b) (Moyo et al., 2017; Derose et al., 2017). Others experienced non-existent support when family members did not provide any support or negatively impacted their well-being. Levels of family support are influenced by stigma, shame, discrimination, knowledge about HIV transmission, and socioeconomic status. Food was the primary medium through which family support, stigma/shame, and discrimination were visibly expressed (Table 3: 3.1c) (Kohli et al., 2012). Lack of family support resulting from shame and stigma was observed in multiple ways including the delay of food preparation, which negatively affected the taking of medication and adherence, not buying desired foods, not sharing utensils and plates, and restricting certain foods like meat or fatty foods, increasing food insecurity for PLHIV (Table 3: 3.1d) (Derose et al., 2017).

Value negotiations refer to factors that compete with individual preferences within the family, including competing basic needs and family preferences. Competing basic needs (e.g., water, school, electricity, rent) refers to prioritizing one family member over another when household resources are scarce, thereby impacting the well-being of family members (37% of articles). Families described how they negotiate housing (Table 3: 3.2a-b) (Pallangyo and Mayers, 2009; Mkandawire et al., 2015; Atukunda et al., 2017), education (Tuller et al., 2010), medical treatment (additional testing, transportation cost, fees) (Pallangyo and Mayers, 2009; Atukunda et al., 2017; Tuller et al., 2010), and food costs (Pallangyo and Mayers, 2009; Atukunda et al., 2017; Tuller et al., 2010), especially since nutritious foods were more expensive. As one mother of five children mentions, the difficult choices between various basic needs (Tuller et al., 2010):

“Yes, I think about that 20,000 [to pay for transportation], I think about the fact that if I didn’t have HIV, I wouldn’t have to spend that money to come here for treatment. I imagine all the other things it could have been used for, and I don’t feel peace in my heart. I could hire people to do the digging, pay for school fees, buy more food. There’s no way I can even think of eating chicken, fish and meat as often as I’d like when I have to get money for transport to this place.” (Tuller et al., 2010)

Families negotiated the value of each short-term need with the needs of PLHIV. Efforts were made to enable PLHIV food choices even when jeopardizing long-term food security and assets of the household (Table 3: 3.2c) (Kaler et al., 2010; Thomas, 2006).

Family desirability refers to balancing all family food preferences and needs while accounting for norms related to religion, ethnicity, culture, or region (4% of articles). In one study, religious norms and festivals, such as fasting, guided PLHIV meal frequency, and anti-retroviral treatment (ART) adherence (Table 3: 3.3) (Bezabhe et al., 2014).

3.4. Health context refers to the chronic disease of focus. We specifically evaluated how the FDF fits within the chronic disease nature of HIV. We found that HIV had a long-term impact on livelihoods with enormous healthcare demands, the family food environment required the family's acceptance of the disease, and their nutritional awareness affected food choice

Impact on livelihoods refers to the lost income due to disease management of an individual with a chronic disease and their family members (49% of articles). Loss of livelihood due to HIV affected family food security and food choice (Table 3: 4.1a) (Pallangyo and Mayers, 2009), especially male-headed households in two ways. First is the loss of wages from men serving as the primary breadwinners. Second, because fewer income-generating opportunities existed for women and many earned lower wages than men, women had to engage in multiple income-generating activities which added to their stress (Table 3: 4.1b-c) (Ogunmefun and Schatz, 2009; Parker et al., 2009; VanTyler and Sheilds, 2015). Lastly, ART adherence was challenged by PLHIV employment due to the frequency and duration of clinic visits and mid-day or timed food consumption (Table 3: 4.1d-e) (Gombachika et al., 2014).

Healthcare refers to the burden associated with disease treatment, including hidden costs such as clinic transportation, waiting time, and testing, and how these healthcare burdens impact food choices (40% of articles). Household resources had to accommodate clinic visits' impact on incomes/livelihoods (Parker et al., 2009; Atukunda et al., 2017). There are additional direct costs associated with transportation and food consumption while going to/from the clinic to get medications and laboratory tests. As families try to account for these costs, they also have income/livelihood loss from allocating time to travel for clinic visits. The cost of HIV treatment (transport, time off work, tests) affected the cash available for food, especially the purchase of nutritious food, which was prohibitively higher (Table 3: 4.2) (Tuller et al., 2010; Balcha et al., 2011).

Community support refers to the structural networks, hospitals, and organized community groups an individual with a chronic disease can rely on to support their food choices (38% of articles). PLHIV groups and clinics also allowed forming PLHIV groups where they relied on each other to access food (Table 3: 4.3) (Aransiola et al., 2014; Horn and Brysiewicz, 2014; Hussen et al., 2014). Housing insecurity was commonly associated with losing livelihood, HIV-associated discrimination, and land grabbing from recently widowed women following the death of their husband who was affected by HIV (Schatz, 2007; Chazan, 2014; Beckett et al., 2016; Aga et al., 2009a; Parker et al., 2009; Mkandawire et al., 2015; Alomepe et al., 2016; Andersen, 2012; Burgess and Campbell, 2014; Du and Lekganyane, 2010; Kang'ethe, 2009a; Olenja, 1999; Schatz and Gilbert, 2012). Aga and colleagues explained, “Due to stigma and discrimination, these family caregivers faced difficulties in finding rental houses and in using communal facilities, like latrines and kitchens” (Aga et al., 2009a).

Acceptance refers to how the household's awareness of the chronic disease status and their demonstration of acceptance through the levels of support they provide (34% of articles). PLHIV often were reluctant to disclose their HIV status (Table 3: 4.4a), which was a key determinant of family support and food choices. Stigma had an erosive weathering effect on familial networks, support, and social capital (Aransiola et al., 2014). This stigma was also enacted within families who expected PLHIV to use separate eating utensils (Table 3: 4.4b-d) (Derose et al., 2017; Jones et al., 2009). Conversely, several articles identified sharing utensils, plates, drinking water, and food as a way to positively express support (Kohli et al., 2012; Aransiola et al., 2014; Wacharasin and Homchampa, 2008; Ngamvithayapong-Yanai et al., 2005; Miller and Tsoka, 2012; Li et al., 2008).

Nutritional awareness refers to how the family domain works to optimize the personal food environment by enabling healthier food choices for an individual with a chronic disease when family members know the person's nutritional needs (15% of articles). Disclosure of HIV status to family members was associated with greater awareness of the importance of nutrition and influenced both family and PLHIV's food choices. Targeted HIV-nutrition education to households raised awareness of PLHIV dietary needs, including scheduled eating around ART (Aga et al., 2009b), and were key to optimal outcomes among PLHIV. Family nutrition knowledge positively impacted PLHIV nutrition as family members cooked special meals, encouraged eating more fruits and vegetables, and avoided raw foods and alcohol (Table 3: 4.5a) (Wacharasin and Homchampa, 2008). Nutrition knowledge did not always translate to consumption behaviors, given that many families face severe financial constraints, loss of livelihood, and competing demands (Table 3: 4.5b-c) (Thomas, 2006; Laker and Ssekiboobo, 2003). Perceptions of healthy food vary with socioeconomic status, with those with low income focused on adequate food quantity. Support can occur at the expense of the health of family members as they forgo food consumption to meet the dietary needs of PLHIV (Gwatirisa and Manderson, 2009), but wealthier households could focus on culturally desirable food and diverse diets with reduced fat and alcohol.

4. Discussion

Family both enables and bounds agency in food consumption and plays a vital role in food access, food choice, and mitigation of health outcomes (Delormier et al., 2009, Giddens, 1991, Slater et al., 2012). In this review, we used Giddens' theory to inform the expansion of Turner's food environment framework to include the family food environment domain among families affected by HIV in LMICs (Turner et al., 2020; Giddens, 1991; Slater et al., 2012). Using qualitative evidence synthesis with a best-fit framework approach, we expanded the LMIC food environment framework within the context of families affected by HIV to develop the Family Dynamics Food Environment Framework (FDF). The 138 qualitative articles identified three major inter-connected domains under FDF through which family decision-making occurs on food choice: resources, characteristics, and action orientation, with the context of a health disease. Within these domains, most research has focused on how family food choices are affected by family support, livelihoods, social capital, and household composition. Other critical dimensions include competing basic needs, costs associated with disease treatment, and resource allocation. The family food environment domain interacts with and represents the complex dynamic of various domains and dimensions, influencing how PLHIV acquire and consume food. The interrelationships of family characteristics were found with livelihoods, social capital, competing basic needs, and gender roles affecting family food choices. Social capital intersected with the type of support PLHIV received and offset costs associated with disease treatment. Gender roles commonly intersect with family composition and social capital.

Many frameworks address family components for HIV care and treatment. Weiser and colleagues seminal work presented the bidirectional relationship between food insecurity and HIV infection, highlighting the role of household dynamics (Weiser et al., 2011). The family caregivers’ conceptions of the care model by Aga and colleagues identified themes that address the food-health needs of PLHIV, mainly symbolic gestures by family members to maintain routine, normalcy, and acceptance despite deprived economic conditions (Aga et al., 2009b, 2014). In the model of interrelationships between HIV, labor, and livelihoods, Parker and colleagues identified how family members (male, female, children) labor changed with different stages of HIV infections, ultimately affecting farming decisions and food security (Parker et al., 2009). Karney et al. and Conroy et al. applied dyadic interdependence theory to an HIV context, offering insights into how marital relationships affect household food security, health-seeking behaviors, and treatment adherence, especially on the role of gender and power to enable or constrain these relationships between couples (Conroy et al., 2018; Karney et al., 2010). A review of barriers to HIV care in East Africa identified family support as critical in realizing care and how stigma and its consequences are gendered (Ayieko et al., 2018). A qualitative meta-synthesis among pregnant women affected by HIV found family stigma a critical aspect of care because “living with people who have HIV requires that people in the environment learn adaptive behaviors and new knowledge to protect and assist these individuals” (Leyva-Moral et al., 2017). Lastly, Iwelunmor and colleagues use the PEN-3 cultural model to highlight families' role in stress, stigma, support, decision-making, and management of PLHIV care (Iwelunmor et al., 2008). These articles highlight the immediate and critical role of the family unit in addressing dietary, social, economic, emotional, and health-seeking aspects of HIV treatment and care. The Family Dynamics Food Environment Framework (FDF) developed here adds a valuable component of family as a social and economic unit for food choice and nutrition in the context of chronic disease.

Our study illuminates the various ways that household food dynamics, the health status of household members, and food choices, interact to ultimately affect decision-making processes for food consumption in the context of chronic disease management in low-resource settings (Messer, 1997). In related work, Lee and colleagues examined food choices since a tuberculosis diagnosis in Peru. They found dietary shifts towards “traditional” foods, with family members as the primary source of knowledge and support (Lee et al., 2020). Similarly, Perez-Leon and colleagues found the family accommodated their family member with type 2 diabetes and hypertension by adopting new dietary habits or minimal cooking methods (e.g., less salt or spices, removing portions of the food) to maintain single cooking preparations rather than multiple meals catering to individual dietary needs (Perez-Leon et al., 2018). We found elements of the FDF similar to other intra-household allocation of food and health frameworks (Messer, 1997; Harris-Fry et al., 2017). In a review of food allocation in Southeast Asia, Harris-Fry and colleagues identified household-level factors as key determinants of food allocation: food insecurity, scarcity, household income, education, nutrition knowledge, size, structure, religion, and ethnicity (Harris-Fry et al., 2017). The recent movement towards understanding food choice across a variety of contexts and themes (e.g., food safety, intergenerational food choices) helps us operationalize the interaction between external and internal food environments (Boncyk et al., 2022; Drew et al., 2022; Isanovic et al., 2023; Reyes et al., 2021; Samaddar et al., 2020; Schreinemachers et al., 2021; Wertheim-Heck and Raneri, 2019; Downs et al., 2022; Karanja et al., 2022; Flax et al., 2020; Green et al., 2020; Bukachi et al., 2021; Nordhagen et al., 2022). Lastly, the FDF has overlapping dimensions with previous high-income countries' food choice frameworks, such as occupation, time, gender roles, and value negotiations among families with school-aged children in Canada (Slater et al., 2012) and middle-income families from New York, USA (Furst et al., 1996). This overlap suggests some food choice dimensions are globalized, likely because of the globalized concept of work and school schedules (e.g., 9-to-5 work schedules).

Our analysis used a theory-driven approach with an a priori framework guided by Gidden's structuration theory and Turner's food environment framework (Turner et al., 2020; Turner et al., 2018; Giddens, 1991; Anthony, 1984). In addition to a systematic approach, we included gray literature and identified records through references. However, this review does have limitations. First, most included articles (>85%) were published before 2016. As families deal with ART adherence, additional factors might affect food choice as the HIV populations age, especially when dealing with mental health challenges and multiple NCD co-morbidities might become prominent (Patel et al., 2018; Kiplagat et al., 2022). Second, very few articles compare families and individual perspectives of the family food environment. Even in articles that interviewed the family members and PLHIV, limitations existed as virtually no study interviewed all family members. Third, children's food choices are important in the family food environment (Wertheim-Heck and Raneri, 2019). This review does not expand on children's food choices in PLHIV households. Lastly, most included articles were conducted in low-income populations. Variations in the interconnected dimensions from wealthier families in LMIC remain understudied. Further validation of the FDF within various families across all SES is warranted.

Poor diet is one of the leading causes of mortality worldwide (Afshin et al., 2019). As food environments rapidly shift towards ultra-processed, energy-dense foods in Southern and Eastern Africa and Asia, where many families affected by HIV live, there is an increased risk for diet-related NCDs among PLHIV and family members who are not living with HIV. Family is an essential intermediary between the external and internal food environments that can enable or bind food choice and operationalize social, economic, and personal factors related to food choice. With rapidly shifting food environments towards cheap, unhealthy foods, intra-household decision-making on food and managing health conditions will play a more significant role in the family food environment (Messer, 1997; Grey et al., 2015). Here, we examined the family food environment in the context of health and illness, which will become an essential integration in nutrition policies as NCD burdens grow in LMICs (Messer, 1997). The resource allocation towards health expenditure affects resource allocation to healthy food choices as families deal with costs associated with increasing morbidities. The FDF presented here, in the context of families affected by HIV, could be readily transferred and generalizable for other chronic and diet-related diseases. FDF could guide intervention design and nutritional policies that are effective and optimal for the entire family.

Authorship

RA conceptualized the study aim and design. RA and MB performed data extraction. RA, MP, and CLP led the analysis, wrote the manuscript, and are primary responsibility for the final content. All authors provided input on the manuscript, read, and approved the final manuscript. RA and MB are joint co-first authors.

Funding sources

This research has been funded by the Drivers of Food Choice Competitive Grants Programs, funded by the UK Government's Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office, and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation [ID: OPP1110043], and managed by the University of South Carolina, Arnold School of Public Health, USA.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Ramya Ambikapathi: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Resources, Project administration, Methodology, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis, Data curation, Conceptualization. Morgan Boncyk: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Software, Project administration, Methodology, Formal analysis. Nilupa S. Gunaratna: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Wafaie Fawzi: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Germana Leyna: Writing – review & editing. Suneetha Kadiyala: Writing – review & editing. Crystal L. Patil: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Validation, Supervision, Project administration, Methodology, Funding acquisition, Formal analysis.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Japhet Killewo for their contribution to conceptualizing this review, and Jim Kanani and Lauren Henniff for their assistance in screening articles for eligibility.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gfs.2024.100788.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data to this article:

Data availability

No data was used for the research described in the article.

References

- Aberman N.L., Rawat R., Drimie S., Claros J.M., Kadiyala S. Food security and nutrition interventions in response to the aids epidemic: assessing global action and evidence. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(5):554–565. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0822-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Afshin A., Sur P.J., Fay K.A., et al. Health effects of dietary risks in 195 countries, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet. 2019 doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(19)30041-8. Published online. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aga F., Kylmä J., Nikkonen M. Sociocultural factors influencing HIV/AIDS caregiving in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia. Nurs. Health Sci. 2009;11(3):244–251. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2018.2009.00448.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aga F., Kylmä J., Nikkonen M. The conceptions of care among family caregivers of persons living with HIV/AIDS in addis ababa, Ethiopia. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2009;20(1):37–50. doi: 10.1177/1043659608322417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aga F., Nikkonen M., Kylmä J. Caregiving actions: outgrowths of the family caregiver's conceptions of care. Nurs. Health Sci. 2014;16(2):149–156. doi: 10.1111/nhs.12077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agbonyitor M. Home-based care for people living with HIV/AIDS in Plateau State, Nigeria: findings from qualitative study. Global Publ. Health. 2009;4(3):303–312. doi: 10.1080/17441690902783165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alemu T., Biadgilign S., Deribe K., Escudero H.R. Experience of stigma and discrimination and the implications for healthcare seeking behavior among people living with HIV/AIDS in resource-limited setting. SAHARA-J J Soc Asp HIVAIDS. 2013;10(1):1–7. doi: 10.1080/17290376.2013.806645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alomepe J., Buseh A.G., Awasom C., Snethen J.A. Life with HIV: insights from HIV-infected women in Cameroon, central Africa. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care. 2016;27(5):654–666. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amurwon J., Hajdu F., Yiga D.B., Seeley J. “Helping my neighbour is like giving a loan…” –the role of social relations in chronic illness in rural Uganda. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2017;17(1):705. doi: 10.1186/s12913-017-2666-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen L.B. Children's caregiving of HIV-infected parents accessing treatment in western Kenya: challenges and coping strategies. Afr. J. AIDS Res. 2012;11(3):203–213. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2012.734979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anema A., Fielden S.J., Castleman T., Grede N., Heap A., Bloem M. Food security in the context of HIV: towards harmonized definitions and indicators. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(Suppl. 5):476–489. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0659-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony Giddens. University of California Press; 1984. The Constitution of Society : Outline of the Theory of Structuration. [Google Scholar]

- Aransiola J., Imoyera W., Olowookere S., Zarowsky C. Living well with HIV in Nigeria? Stigma and survival challenges preventing optimum benefit from an ART clinic. Glob Health Promot. 2014;21(1):13–22. doi: 10.1177/1757975913507297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo GM de, Leite M.T., Hildebrandt L.M., Oliveski C.C., Beuter M. Self-care of elderly people after the diagnosis of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2018;71:793–800. doi: 10.1590/0034-7167-2017-0248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asgary R., Amin S., Grigoryan Z., Naderi R., Aronson J. Perceived stigma and discrimination towards people living with HIV and AIDS in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: a qualitative approach. J. Public Health. 2013;21(2):155–162. doi: 10.1007/s10389-012-0533-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atukunda E.C., Musiimenta A., Musinguzi N., et al. Understanding patterns of social support and their relationship to an ART adherence intervention among adults in rural southwestern Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(2):428–440. doi: 10.1007/s10461-016-1559-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atuyambe L.M., Ssegujja E., Ssali S., et al. HIV/AIDS status disclosure increases support, behavioural change and, HIV prevention in the long term: a case for an Urban Clinic, Kampala, Uganda. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2014;14(1):276. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-14-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Axelsson J.M., Hallager S., Barfod T.S. Antiretroviral therapy adherence strategies used by patients of a large HIV clinic in Lesotho. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2015;33:10. doi: 10.1186/s41043-015-0026-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayieko J., Brown L., Anthierens S., et al. “Hurdles on the path to 90-90-90 and beyond”: qualitative analysis of barriers to engagement in HIV care among individuals in rural East Africa in the context of test-and-treat. PLoS One. 2018;13(8) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0202990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balaile G., Laisser R., Ransjö-Arvidson A.B., Höjer B. Poverty and devastation of intimate relations: Tanzanian women's experience of living with HIV/AIDS. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care. 2007;18(5):6–16. doi: 10.1016/j.jana.2007.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balcha T.T., Jeppsson A., Bekele A. Barriers to antiretroviral treatment in Ethiopia: a qualitative study. J. Int. Assoc. Phys. AIDS Care. 2011;10(2):119–125. doi: 10.1177/1545109710387674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett CB, Reardon T, Swinnen J, Zilberman D. Structural Transformation and Economic Development: Insights from the Agri-Food Value Chain Revolution. :56.

- Battersby J., Watson V. Addressing food security in African cities. Nat. Sustain. 2018;1(4):153–155. doi: 10.1038/s41893-018-0051-y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baylies C. The impact of AIDS on rural households in Africa: a shock like any other? Dev. Change. 2002;33(4):611–632. doi: 10.1111/1467-7660.00272. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beckett A.G., Humphries D., Jerome J.G., Teng J.E., Ulysse P., Ivers L.C. Acceptability and use of ready-to-use supplementary food compared to corn–soy blend as a targeted ration in an HIV program in rural Haiti: a qualitative study. AIDS Res. Ther. 2016;13(1):11. doi: 10.1186/s12981-016-0096-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belsey M.A. UN; 2006. AIDS and the Family: Policy Options for a Crisis in Family Capital. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bezabhe W.M., Chalmers L., Bereznicki L.R., Peterson G.M., Bimirew M.A., Kassie D.M. Barriers and facilitators of adherence to antiretroviral drug therapy and retention in care among adult HIV-positive patients: a qualitative study from Ethiopia. PLoS One. 2014;9(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097353. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bindura-Mutangadura G. HIV/AIDS, poverty, and elderly women in urban Zimbabwe - ProQuest. Southern African Feminist Rev. 2001;4(2/V.5):93. [Google Scholar]

- Boncyk M., Shemdoe A., Ambikapathi R., et al. Exploring drivers of food choice among PLHIV and their families in a peri-urban Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. BMC Publ. Health. 2022;22(1):1068. doi: 10.1186/s12889-022-13430-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braathen S.H., Sanudi L., Swartz L., Jürgens T., Banda H.T., Eide A.H. A household perspective on access to health care in the context of HIV and disability: a qualitative case study from Malawi. BMC Int. Health Hum. Right. 2016;16(1):12. doi: 10.1186/s12914-016-0087-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bukachi S.A., Ngutu M., Muthiru A.W., Lépine A., Kadiyala S., Domínguez-Salas P. Consumer perceptions of food safety in animal source foods choice and consumption in Nairobi's informal settlements. BMC Nutr. 2021;7(1):35. doi: 10.1186/s40795-021-00441-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgess R., Campbell C. Contextualising women's mental distress and coping strategies in the time of AIDS: a rural South African case study. Transcult. Psychiatr. 2014;51(6):875–903. doi: 10.1177/1363461514526925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byron E., Gillespie S., Nangami M. Integrating nutrition security with treatment of people living with HIV: lessons from Kenya. Food Nutr. Bull. 2008;29(2):87–97. doi: 10.1177/156482650802900202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell C., Skovdal M., Madanhire C., Mugurungi O., Gregson S., Nyamukapa C. “We, the AIDS people. . .”: how antiretroviral therapy enables Zimbabweans living with HIV/AIDS to cope with stigma. Am. J. Publ. Health. 2011;101(6):1004–1010. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2010.202838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carroll C., Booth A., Leaviss J., Rick J. “Best fit” framework synthesis: refining the method. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013;13(1):37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-13-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chazan M. Everyday mobilisations among grandmothers in South Africa: survival, support and social change in the era of HIV/AIDS. Ageing Soc. 2014;34(10):1641–1665. doi: 10.1017/S0144686X13000317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Conroy A.A., McKenna S.A., Comfort M.L., Darbes L.A., Tan J.Y., Mkandawire J. Marital infidelity, food insecurity, and couple instability: a web of challenges for dyadic coordination around antiretroviral therapy. Soc. Sci. Med. 2018;214:110–117. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooke A., Smith D., Booth A. Beyond PICO: the SPIDER tool for qualitative evidence synthesis. Qual. Health Res. 2012;22(10):1435–1443. doi: 10.1177/1049732312452938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crane J.T., Kawuma A., Oyugi J.H., et al. The price of adherence: qualitative findings from HIV positive individuals purchasing fixed-dose combination generic HIV antiretroviral therapy in kampala, Uganda. AIDS Behav. 2006;10(4):437–442. doi: 10.1007/s10461-006-9080-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Critical appraisal Skills programme. 2018. https://casp-uk.net/images/checklist/documents/CASP-Qualitative-Studies-Checklist/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf Published online.

- Czaicki N.L., Mnyippembe A., Blodgett M., Njau P., McCoy S.I. It helps me live, sends my children to school, and feeds me: a qualitative study of how food and cash incentives may improve adherence to treatment and care among adults living with HIV in Tanzania. AIDS Care. 2017;29(7):876–884. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2017.1287340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis L.M., Kostick K.M. Balancing risk, interpersonal intimacy and agency: perspectives from marginalised women in Zambia. Cult. Health Sex. 2018;20(10):1102–1116. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2018.1462889. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- deGraft Agyarko R., Madzingira N., Mupedziswa R., Mujuru N., Kanyowa L., Matorofa J. World Health Organization; 2002. Impact of AIDS on Older People in Africa: Zimbabwe Case Study.https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/67545/WHO_NMH_NPH_ALC_02.12.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Delobelle P. Big tobacco, alcohol, and food and NCDs in LMICs: an inconvenient truth and call to action. Int. J. Health Pol. Manag. 2019;8(12):727–731. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2019.74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delormier T., Frohlich K.L., Potvin L. Food and eating as social practice - understanding eating patterns as social phenomena and implications for public health. Sociol. Health Illness. 2009;31(2):215–228. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2008.01128.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Derose K.P., Payán D.D., Fulcar M.A., et al. Factors contributing to food insecurity among women living with HIV in the Dominican Republic: a qualitative study. PLoS One. 2017;12(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0181568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dinh H.T., White J.L., Hipwell M., Nguyen C.T.K., Pharris A. The role of the family in HIV status disclosure among women in Vietnam: familial dependence and independence. Health Care Women Int. 2018;39(4):415–428. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2017.1358723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dovel K., Thomson K. Financial obligations and economic barriers to antiretroviral therapy experienced by HIV-positive women who participated in a job-creation programme in northern Uganda. Cult. Health Sex. 2016;18(6):654–668. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2015.1104386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Downs S.M., Fox E.L., Zivkovic A., et al. Drivers of food choice among women living in informal settlements in Nairobi, Kenya. Appetite. 2022;168 doi: 10.1016/j.appet.2021.105748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drew S., Blake C., Monterrosa E., et al. How schwartz’ basic human values influence food choices in Kenya and Tanzania. Curr. Dev. Nutr. 2022;6(Suppl. ment_1):479. doi: 10.1093/cdn/nzac059.007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du Plessis G., Lekganyane E.M. The role of food gardens in empowering women: a study of Makotse Women's Club in Limpopo. J. Soc. Dev. Afr. 2010;25(2):97–120. [Google Scholar]

- Dworkin S.L., Grabe S., Lu T., et al. Property rights violations as a structural driver of women's HIV risks: a qualitative study in Nyanza and Western Provinces, Kenya. Arch. Sex. Behav. 2013;42(5):703–713. doi: 10.1007/s10508-012-0024-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferlander S. The importance of different forms of social capital for health. Acta Sociol. 2007;50(2):115–128. doi: 10.1177/0001699307077654. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fielding-Miller R., Mnisi Z., Adams D., Baral S., Kennedy C. “There is hunger in my community”: a qualitative study of food security as a cyclical force in sex work in Swaziland. BMC Publ. Health. 2014;14(1):79. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-14-79. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flax V.L., Thakwalakwa C., Phuka J.C., Jaacks L.M. Body size preferences and food choice among mothers and children in Malawi. Matern. Child Nutr. 2020;16(4) doi: 10.1111/mcn.13024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Flemming K., Noyes J. Qualitative evidence synthesis: where are we at? Int. J. Qual. Methods. 2021;20 doi: 10.1177/1609406921993276. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Furst T., Connors M., Bisogni C.A., Sobal J., Falk L.W. Food choice: a conceptual model of the process. Appetite. 1996;26(3):247–266. doi: 10.1006/appe.1996.0019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebremariam M.K., Bjune G.A., Frich J.C. Barriers and facilitators of adherence to TB treatment in patients on concomitant TB and HIV treatment: a qualitative study. BMC Publ. Health. 2010;10(1):651. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-10-651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giddens A. Past Present Future Bryant C Jary Deds Giddens' Theory Struct Crit Apprec Lond. Routledge; 1991. Structuration theory; pp. 55–66. Published online. [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie A.H., Gillespie G.W. Family food decision-making: an ecological systems framework. J. Fam. Consum. Sci. 2007;99(2):22–28. [Google Scholar]