Abstract

The induction of alpha/beta interferon (IFN-α/β) genes constitutes one of the first responses of the cell to virus infection. The IFN-β gene is constitutively repressed in uninfected cells and is transiently activated after virus infection. In this work we demonstrate that histone deacetylation regulates the silent state of the murine IFN-β gene. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays, we show a direct in vivo correlation between the transcriptionally silent state and a state of hypoacetylation of histone H4 on the IFN-β promoter region. Trichostatin A (TSA), a specific inhibitor of histone deacetylases, induced strong, constitutive derepression of the murine IFN-β promoter stably integrated into a chromatin context, as well as the hyperacetylation of histone H4, without requiring de novo protein synthesis. We also show in this work that TSA treatment strongly enhances the endogenous IFN level and confers an antiviral state to murine fibroblastic L929 cells. Inhibition of histone deacetylation with TSA protected the cells against the lost of viability induced by vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) and inhibited VSV multiplication. Using antibodies neutralizing IFN-α/β, we show that the antiviral state induced by TSA is due to TSA-induced IFN production. The demonstration of the predominant role of histone deacetylation during the regulation of the constitutive repressed state of the IFN-β promoter constitutes an interesting advance on the understanding of the negative regulation of this gene and opens up the possibility of new therapeutic perspectives.

The beta interferon (IFN-β) gene remains silent throughout the cell cycle of a differentiated cell unless it is activated in response to specific extracellular signals such as virus infection (10, 11). This activation is only transitory and is rapidly turned off after virus infection (27, 58). Abundant data have been published concerning the organization of the minimal promoter region required for the virus-induced transcriptional activation of this gene (reviewed in reference 28). This region, which constitutes the virus-responsive element (VRE), is present between positions −110 and −55 of the promoter and consists of a complex enhancer comprising DNA-binding sites for several transcription factors such as NF-κB, proteins belonging to the family of IFN regulatory factors (IRFs), and activating transcription factor 2 (ATF-2/c-Jun) (29, 57). The architectural protein high-mobility group protein I (HMGI) binds to the VRE region of the human IFN-β promoter (28) but not to the VRE of the murine promoter (4). More recently, it has been demonstrated that the promoter recruits the transcriptional coactivator CBP/p300, which carries a histone acetyltransferase activity (40), after virus infection through interactions with the transcription factor IRF3 (23, 30, 62). In contrast to the positive regulation of the gene, the molecular mechanisms leading to the constitutive negative regulation of the IFN-β gene remain less well understood. It has been known for many years that the IFN-β gene is under negative control (12). Two regions of the IFN-β promoter, named negative regulatory domains (NRD) I and II, have been described as intervening during the establishment of the constitutive repressed state of the promoter (12, 13, 39, 63). The NF-κB-repressing factor (38, 39) and protein PRDI-BF1 (21, 47) interact with the NRD I region (situated between positions −37 and −60). Interaction of the NF-κB-repressing factor with the NRD I region prevents the binding of the small amount of NF-κB present in the nucleus before virus infection and, by doing so, partially regulates the repressed state of the IFN-β gene. Protein PRDI-BF1 is a postinduction repressor of the IFN-β gene in conjunction with members of the Groucho family (45). Its mRNA is detectable 4 h after virus infection, and only very small amounts of the protein are present before virus infection (21), making this protein a poor candidate for the establishment of the prolonged constitutive silencing of the gene (45). The determination in vivo of virus-induced DNase I-hypersensitive sites (64) on the NRD II region (situated approximately between positions −110 and −220), as well as the description of a preferential in vitro interaction of linker histone H1 with this highly A/+T-rich DNA sequence (4), suggests the presence of an organized chromatin structure on this region. In a previous work we have described a specific binding site for HMGI at position −130 of the murine promoter, between the VRE and NRD II. Binding of HMGI to this site displaced histone H1 in vitro and affected the promoter derepression in vivo (4).

Several observations tend to indicate that chromatin and chromatin remodeling play an important role in regulation of the expression of the IFN-β gene. First, the activation of the IFN-β promoter resulting from an overexpression of CBP/p300 requires the histone acetyltransferase activity of this coactivator (34). Second, virus induction leads to a local hyperacetylation of histone H3 and H4 (42). Third, we have observed significant differences between the virus-induced transcriptional activation of the stably transfected murine IFN-β promoter upon which chromatin has been fully reconstituted and the transiently transfected promoters upon which chromatin has only been poorly and randomly reconstituted (4). Also, we have observed that displacement of H1 in the presence of distamycin or after overexpression of scaffold attachment regions leads to a partial derepression of the promoter (4). Abundant biochemical and genetic data indicate that histone deacetylation and addition of histone H1 represses gene expression (2, 6, 26) whereas acetylation of core histones, together with linker histone deficiency, is correlated with gene transcriptional activation (16, 19, 37, 52).

In this work, we have analyzed the role of histone deacetylation during the constitutive silencing of the IFN-β gene. We show that inhibition of histone deacetylases (HDACs) with trichostatin A (TSA), a specific inhibitor of HDACs (26, 31, 54), induced strong, constitutive derepression of the murine IFN-β promoter stably integrated into a chromatin context, as well as high levels of endogenous IFN. Using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays, we demonstrate a direct correlation between the repressed, constitutive silent state of the promoter and a state of hypoacetylation of histone H4 on the promoter. We also present data indicating that TSA-induced activation of the murine IFN-β (muIFN-β) promoter is independent of de novo protein synthesis and is mediated by the NRD II region of the promoter. Moreover, treatment of murine fibroblast L929 cells with TSA at concentrations as low as 12.5 ng/ml conferred an antiviral state. Using antibodies that neutralize IFN-α/β, we show that the antiviral state induced by TSA is the consequence of an enhanced, TSA-induced production of endogenous IFNs.

The results presented in this work indicate that histone deacetylation is one of the main molecular events which potentiates the constitutive repressed state of the IFN-β promoter. TSA treatment mimics the effect of virus infection for the activation of the transcriptional capacity of the IFN-β promoter and confers an antiviral activity. Both these facts lead us to consider the possibility of new therapeutic applications linked to TSA treatment for the establishment of an antiviral state.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cell lines and culture.

The L929 wt330 and wt110 cell lines were constructed as previously described (4). Briefly, the corresponding IFN-β chloramphenicol acetyltransferase (CAT) reporter plasmids were cotransfected in a 5:1 molar ratio with plasmid pCB6, carrying resistance to Geneticin, by the calcium phosphate method. The transfected cells were selected for 3 weeks in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium supplemented with antibiotics, l-glutamine, nonessential amino acids, and 10% fetal calf serum containing G418 (600 μg/ml; GIBCO). Clones were isolated, propagated, and tested for virus-induced CAT activity during several passages of the cells. An average of 10 positives clones were pooled and frozen.

Virus infection and CAT assays.

One day prior to virus infection, the cells were split among six-well plates (200 000 cells/well) in medium without G418. Virus infection was carried out with Newcastle disease virus (NDV) as previously described (8). Mock-infected cells were treated like infected cells, except that no NDV was added to the medium. The cells were harvested at different times after NDV infection, and CAT activity was measured as previously described (8). The results presented in each figure correspond to an average of at least three independent experiments. For each experiment, NDV inductions were carried out in duplicate.

TSA treatment.

TSA (Sigma), kept at −20°C at 1.0 mg/ml in dimethyl sulfoxide, was freshly diluted in culture medium and added to the cells at a final concentration of 50 ng/ml for 48 h. The TSA was removed from the medium before virus infection. During cytopathic effect assays, TSA was added at a final concentration of 12.5 ng/ml for 24 h before vesicular stomatitis virus (VSV) infection. In the experiment in Fig. 1B, cycloheximide was added to the medium at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml 30 min before the TSA was added.

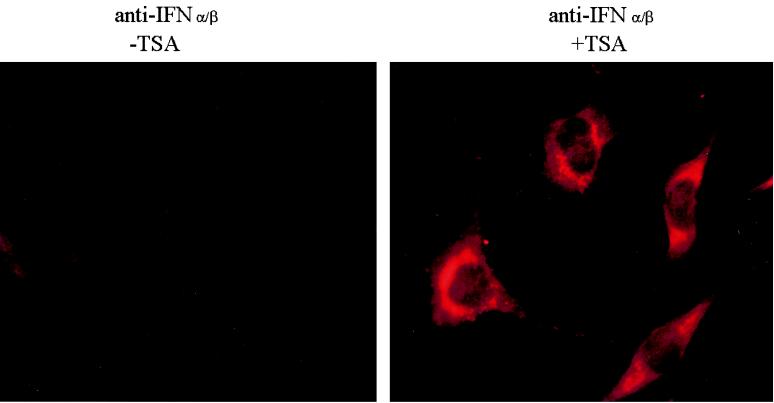

FIG. 1.

TSA treatment increases the endogenous IFN level in the absence of virus infection. Noninfected murine L929 cells were indirectly labeled with anti-IFN α/β antibodies. Note very low level of endogenous IFN in untreated cells and its high level in TSA-treated cells.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation.

L929 wt330 cells were fixed by addition of 1% formaldehyde to the medium for 10 min, scraped, and collected by centrifugation. The cells were resuspended in 0.1 ml of lysis buffer (1% sodium dodecyl sulfate [SDS], 10 mM EDTA, 50 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.1]) supplemented with 0.5 mM phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride, 1 μg of pepstatin A per ml, 1 μg of leupeptin per ml, and 0.5 mg of benzamidine per ml as previously described (5). Then 0.4 ml of Tris-EDTA (TE) was added, the cells were sonicated 10 times for 10 s, each, the lysates were cleared by centrifugation, and the concentration of DNA was determined. DNA was precipitated with ethanol, resuspended in 0.1 ml of TE, and diluted 10-fold in dilution buffer (0.01% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris HCl [pH 8.1], 150 mM NaCl) as previously described (27). Chromatin solution was precleared for 45 min at 4°C on protein A-Sepharose 4B beads preadsorbed with sonicated single-stranded DNA (1 ml of a 50% suspension of protein A-Sepharose 4B beads plus 8 μl of sonicated single-stranded DNA [10 mg/ml]). Corresponding aliquots of chromatin solution were then incubated with 1 μl of anti-H4 or anti-H4Ac antibodies (Chemicon) overnight at 4°C. Immune complexes were collected on protein A beads preadsorbed with sonicated single-stranded DNA. Beads were washed sequentially once each in TSE (0.1% SDS, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mM EDTA, 20 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.1]) with 150 mM NaCl, TSE with 500 mM NaCl, and buffer A (0.25 LiCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% deoxycholate, 1 mM EDTA, 10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.1]) and three times in TE and then extracted three times with 1% SDS–0.1 M NaHCO3. Cross-links were reversed by heating at 65°C for 4 h, and DNA was precipitated with ethanol. Precipitates were resuspended in 20 μl of TE, digested with proteinase K (50 μg/ml) for 1 hr at 37°C, extracted with phenol-chloroform (1:1), and ethanol precipitated. PCR analysis of immunoprecipitated DNA was performed using oligonucleotide F-40 (specific for the pBLCAT3 vector) (5′-gTT TTC CCA gTC ACg AC-3′) as the 5′ primer and oligonucleotide CAT (specific for the CAT reporter gene) (5′-CCA TTT TAg CTT CCT TAg CTC-3′) as the 3′ primer. PCR conditions were as follows: 1 cycle of 94°C for 1 min, 60°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min); 1 cycle of 94°C for 1 min; 58°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min; 1 cycle of 94°C for 1 min, 55°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min; and 20 cycles of 94°C for 1 min; 53°C for 1 min, and 72°C for 1 min.

Cytopathic effect assays.

Monolayer cultures of L929 cells in 96-well plates were incubated with TSA at a final concentration of 12.5 ng/ml for 24 h before VSV infection. Before VSV infection, the medium containing TSA was removed. Viruses were diluted in medium with serum and added directly to the culture medium. The monolayers were stained with crystal violet as vital dye 48 h after VSV infection. Polyclonal anti-IFN antibodies were raised against IFN-α/β produced in C243 cells after NDV infection. The results in Fig. 3 and 5 (bottom panel) were quantified using a Titertek Multiskan instrument with a 595-nm filter. In tables 4 and 5, 100% cell viability corresponds to the intensity of staining measured in noninfected cells (multiplicity of infection = 0).

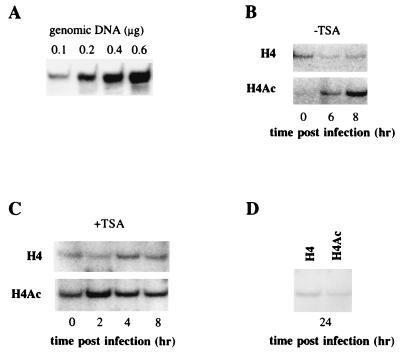

FIG. 3.

Histone H4 on the IFN-β promoter region is hypoacetylated before virus infection in the absence of TSA. DNA from L929 wt330 cells infected or not infected with NDV and incubated with or without TSA were immunoprecipitated as described in Materials and Methods with antibodies raised against H4Ac or nonacetylated H4. The amount of immunoprecipitated DNA was determined by PCR as described in Materials and Methods. (A) PCR analysis of increasing amounts of input DNA: the intensity of the IFN-β band obtained after PCR is proportional to the input of DNA. (B) PCR analysis of DNA from L929 wt330 cells in the absence of TSA (−TSA) immunoprecipitated with H4Ac or H4 antibodies before and after virus infection. (C) PCR analysis of DNA from L929 wt330 cells treated with TSA (+TSA) and immunoprecipitated with H4Ac or H4 antibodies before and after virus infection. (D) PCR analysis of DNA from L929 wt330 cells, not treated with TSA, collected 24 h after virus infection, and immunoprecipitated with H4Ac or H4 antibodies.

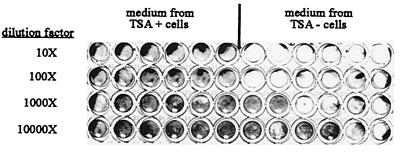

FIG. 5.

TSA treatment inhibits VSV multiplication. Supernatant (diluted 10-, 100-, 1,000-, or 10,000-fold) from TSA-treated (TSA+) or untreated (TSA−) cells infected with VSV at a MOI of 0.1, as in Fig. 3, was used to infect confluent monolayers of murine L929 cells. The cells were stained with vital dye 48 h after the medium was added.

Titration of IFN activity.

IFNs present in the supernatants of virus-infected L929 cells, previously treated or not with TSA (at a concentration of 12.5 ng/ml for 24 h before NDV infection) were titrated using the antiviral activity assay described by Mogensen and Bandu (33) against an IFN-β reference, which had itself been standardized against the international reference MRC 69/19.

Immunofluorescence microscopy.

Endogenous IFN was revealed by indirect immunofluorescent microscopy. Murine L929 cells were plated in 2 ml of medium in six-well plates on 20- by 20-mm coverslips at a density of 105 cells/ml. The cells were allowed to attach to the coverslips for several hours, and then TSA, was added at a final concentration of 50 ng/ml for 24 h. TSA-untreated and -treated cells were fixed with 3.7% formaldehyde for 15 min at room temperature, washed with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), and permeabilized with 1% Triton X-100 in PBS. Then the cells were incubated for 1 h at room temperature with sheep polyclonal antibodies against mouse IFN-α/β (PBL Biomedical Labs) diluted 200-fold in PBS–5% bovine serum albumin (according to the manufacturer, this dilution corresponds to a final concentration of 5 × 103 neutralization units/ml). The cells were washed with PBS–5% bovine serum albumin and incubated for 1 h at room temperature with secondary donkey anti-sheep antibodies conjugated with CY3 diluted 100-fold. The cells were observed with a Nikon eclipse E600 microscope.

RESULTS

Inhibition of histone deacetylation leads to nearly complete derepression of the constitutive silent state of the muIFN-β promoter.

To assess the role of histone deacetylation during the establishment of the constitutive silent state of the muIFN-β promoter, we have used TSA, a specific inhibitor of histone deacetylases, and ChIP assays. Since chromatin is correctly reconstituted in stably transfected DNA templates but remains incompletely organized in transiently transfected DNAs (22, 49), the effect of histone deacetylation was investigated on a stably transfected muIFN-β promoter.

Cells from the murine L929 wt330 cell line, constructed as described in Materials and Methods, carrying a stably integrated wild-type muIFN-β promoter (from promoter positions −330 to +20) CAT reporter construct were incubated with 50 ng of TSA per ml for 48 h. The cells were then collected, and their corresponding CAT activities were compared to the activities obtained with the cells that have not been incubated with TSA. In the absence of virus infection, the IFN-β promoter is constitutively repressed so that noninfected L929 wt330 cells display a very weak CAT activity, only slightly superior to the background values of the CAT assays. The TSA-dependent inhibition of HDAC led to a dramatic derepression of the promoter constitutive activity, inducing a 128-fold activation of its transcriptional capacity (Table 1). The activity displayed by the promoter under these conditions corresponds to 40% of the maximum CAT activity reached by the promoter 10 h after virus infection in the absence of TSA. To investigate the effect of TSA on endogenous IFN production, we carried out indirect immunofluorescence microscopy using polyclonal anti-mouse IFN-α/β antibodies. As shown in Fig. 1, treatment of non-infected L929 cells with TSA induced high levels of endogenous IFN synthesis.

TABLE 1.

CAT activity of the wt330 IFN-β promoter in the absence or presence of TSA

| Infection status | CAT activitya (cpm/h/mg) in presence of TSA (ng/ml) at:

|

TSA activation (fold) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 50 | ||

| Noninfected | 1,017 ± 684 | 132,943 ± 9,974 | 128 |

| 10 h postinfection | 334,735 ± 99,924 | 307,517 ± 130,417 | ≈1 |

The background value of the CAT activity test corresponding to 1,725 cpm/hr/mg has been subtracted. Values are means ± standard deviations.

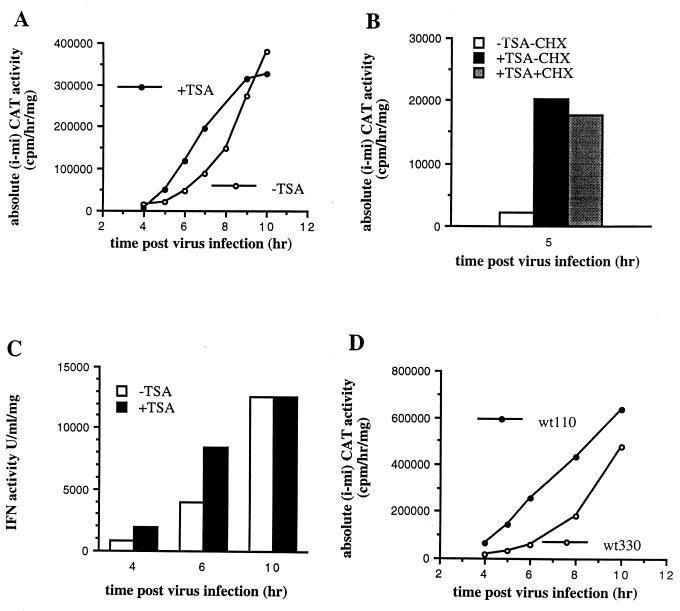

We also analyzed the effect of TSA on the virus-induced kinetics of IFN-β promoter activation. For this purpose, L929 wt330 TSA-treated or untreated cells were virus infected after removal of TSA from the medium and collected at different times after infection and their corresponding CAT activities were determined. To analyze the effect of TSA on the virus-induced CAT activity independently of the effect of TSA on the constitutive noninduced CAT activity, we subtracted the mock-induced (mi) CAT activity from the final CAT activity obtained after virus infection (i). We called this activity the absolute (i − mi) CAT activity. As shown in Fig. 2A, TSA-treated cells displayed faster virus-induced kinetics of transcription whereas the maximum transcriptional capacity reached by the promoter 10 h after infection was not affected (Table 1; Fig. 2A).

FIG. 2.

TSA treatment induces a strong constitutive derepression of the IFN-β promoter. (A) L929 wt330 cells carrying the stably transfected wild-type muIFN-β promoter (from positions −330 to +20) fused upstream of a CAT reporter gene were treated with TSA as described in Materials and Methods. The CAT activities of the cells treated or not treated with TSA (50 ng/ml) for 48 h were measured at different times after virus infection, and the corresponding absolute (i − mi) CAT activities were determined. (B) CHX was added, or not added, to the medium at a final concentration of 10 mg/ml 30 min before adding TSA (50 ng/ml). Six hours after addition of TSA, the cells were infected with NDV; they were collected 5 h after infection. (C) The IFN protein in the supernatant of virus-infected, TSA-treated and -untreated cells was titrated, as described in Materials and Methods, at different times after virus infection. (D) L929 wt330 and wt110 cells carrying a stably transfected “short” muIFN-β promoter (from positions −110 to +20) lacking the NRD II region were virus infected, and the corresponding absolute (i − mi) CAT activities were measured at different times after infection.

In Fig. 2B we compare the capacity of TSA to induce transcriptional activation of the muIFN-β promoter in the presence or absence of cycloheximide, an inhibitor of protein synthesis. Cycloheximide at a final concentration of 100 μg/ml was added to the medium of L929 wt330 cells 30 min before TSA was added. Six hours later the medium was removed and the cells were virus infected; they were collected 5 h after virus infection. As shown in Fig. 2B, the presence of cycloheximide during TSA treatment of the cells did not interfere with the capacity of TSA to activate the muIFN-β promoter. The effect of TSA on the transcriptional capacity of the muIFN-β promoter is therefore not a consequence of TSA-induced de nova protein synthesis.

To investigate the effect of TSA on the virus-induced kinetics of activation of the endogenous muIFN-β promoter, we titrated the IFN activity present in the supernatant of virus-infected murine L929 TSA-treated or -untreated cells. As shown in Fig. 2C, the effect of TSA on the virus-induced kinetics of activation of the endogenous IFN promoter is analogous to that observed on the stably integrated promoter: an increase of the virus-induced kinetics of IFN production with no effect on the maximum IFN activity measured 10 h after infection.

The IFN-β constitutive silent state is correlated with a state of hypoacetylation of histone H4 on the muIFN-β promoter region.

The above results indicate that inhibition of HDACs induces IFN-β promoter derepression. To determine if HDAC activity is directly responsible for maintaining the promoter on a histone-deacetylated state, we carried out ChIP assays with antibodies directed against either histone H4 or the acetylated forms of histone H4 (H4Ac). L929 wt330 cells were mock or virus infected, lysed, and sonicated and genomic DNA was immunoprecipitated as described in Materials and Methods. The amount of immunoprecipitated DNA corresponding to the muIFN-β promoter region was analyzed by PCR using the primers described in Materials and Method. A titration of input DNA is shown in Fig. 3A. It illustrates that under the PCR conditions we used here, the intensity of the amplified IFN-β band is proportional to the amount of input DNA. The results in Fig. 3B to D were quantified by PhosphorImager analysis, and the ratio of IFN-β DNA immunoprecipitated with anti-H4Ac to anti-H4 antibodies was determined (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Ratio of the PCR-amplified IFN-β DNA immunoprecipitated with anti-H4Ac and anti-H4 antibodies at different times after NDV infection

| Antibody | Time (h) after NDV infection:

|

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 2 | 6 | 8 | 24 | |

| H4Ac/H4 (−TSA) | <0.01 | NDa | 2.6 | 3.2 | 0.5 |

| H4Ac/H4 (+TSA) | 2.3 | 2.9 | 2.55 | 2.67 | ND |

ND, not determined.

The DNA isolated from constitutively repressed, mock-infected cells was not immunoprecipitated with antibodies directed against H4Ac, whereas it was immunoprecipitated with antibodies raised against the nonacetylated form of histone H4 (Fig. 3B). The H4Ac antibodies we used can immunoprecipitate the acetylated forms of any of the four lysine (Lys5, Lys8, Lys12, and Lys16) of histone H4. The absence of immunoprecipitate observed when mock-infected cells were incubated with these H4Ac antibodies indicates that histone H4 on the constitutively silent promoter is in an unacetylated state. This observation confirms our hypothesis that an HDAC is directly maintaining the muIFN-β promoter in a state of hypoacetylation.

In Fig. 3C it can be observed that incubation of mock-infected cells with TSA led to a clear increase in the amount of DNA immunoprecipitated with H4Ac antibodies. The TSA-induced derepression of the promoter (in the absence of any virus infection) can therefore be correlated with an increase in the degree of H4 acetylation on the IFN-β promoter region. Concerning the effect of virus infection on the degree of histone acetylation on the IFN-β promoter region, we have reproduced here with the murine promoter the results previously obtained by Parekh and Maniatis (42) with the human promoter, i.e., a virus-induced hyperacetylation of histone H4 on the IFN-β promoter (Fig. 3B).

The IFN-β promoter reaches its maximal activity between 10 and 12 h after virus infection, and then its transcriptional capacity is turned off. In this work we have investigated if the return of the promoter to a silent state could be correlated with a return of histone H4 to an unacetylated state. For this purpose we analyzed, using ChIP assays, the degree of histone H4 acetylation on the muIFN-β promoter region on DNA isolated from L929 wt330 cells collected 24 h after infection. The ratio of DNA immunoprecipitated with H4Ac antibodies as opposed to H4 antibodies diminished 24 h after infection (Fig. 3D; Table 2), indicating that histone deacetylation has occurred during the postinfection transcriptional turnoff. Nevertheless, this deacetylation is only partial, since 24 h after infection the promoter has not reached the complete histone hypoacetylated state observed before virus infection. Reconstitution of chromatin is linked to DNA replication. It is therefore possible that 24 h after infection (i.e., 12 h after that the promoter has reached its maximal activity), reconstitution of hypoacetylated chromatin has not yet occurred inside all virus-infected L929 cells, which divide approximately every 24 h. Nevertheless, the fact that 24 h after infection, histones on the promoter region have not reached the hypoacetylated state observed before virus infection suggests that the transcriptional turnoff of the promoter does not require the establishment of a complete histone hypoacetylated state. Even though some histone deacetylation occurs during the postinfection transcriptional turnoff of the promoter, this is not the only factor intervening during this phenomenon. As a matter of fact, factors such as IRF2, PRDI-BF1, and HMGI, not related to HDACs, have been previously described as responsible for the transcriptional turnoff of this promoter.

HDACs have the capacity to interact with proteins that specifically bind to methylated DNA (3), such as protein MeCP2, which binds to methylated DNA and exists in a complex with HDAC (20, 35). To test the eventual role of DNA methylation during the negative regulation of the IFN-β promoter, we carried out experiments with the demethylating agent 5-aza-2′-deoxycytidine (5Aza-dC). Treatment of the cells with 440 nM 5Aza-dC for 48 h had no detectable effect on the transcriptional capacity of the IFN-β promoter. When we incubated the cells with both TSA and 5Aza-dC, we obtained the same results as in the presence of TSA alone (data not shown). According to these results, DNA methylation does not seem to be intervening during the establishment of the silent state of the IFN-β promoter in conjunction with histone deacetylation. Besides, no CpG islands have been identified in either the 5′ or the 3′ region of the muIFN-β locus.

The A/+T-rich NRD II of the IFN-β promoter mediates most of the effect of TSA.

The upstream A/+T-rich NRD II region of the human IFN-β promoter has been described as a negative regulatory element participating in the establishment of the constitutive silent state of the human IFN-β gene (63). We were therefore interested in determining if the effect of TSA was mediated by this region. For this purpose, we constructed a murine L929 wt110 cell line carrying a stably transfected short muIFN-β promoter (from positions −110 to +20) fused upstream of a CAT reporter gene. The wt110 promoter, which contains the entire VRE but lacks the NRD II region, displayed a phenotype analogous to the one induced by TSA on the wild-type wt330 promoter: a high constitutive transcriptional capacity (the CAT activity was 33,064 ± 12,540 and 86,189 ± 6,819 cpm/h/mg in the absence and presence of 50 ng of TSA/ml, respectively) and rapid kinetics of induction (Fig. 2D). Deletion of the NRD II region mimics most of the effects induced by TSA on the muIFN-β promoter. Interestingly, TSA had only a weak effect on this promoter (2.6-fold activation), which carries only the VRE region, compared to its effect observed on the wt330 promoter (128-fold activation), which contains the VRE and the NRD II region. The effect of TSA appears to be mediated mainly by the NRD II rather than the VRE region.

TSA treatment confers antiviral activity.

Since TSA treatment induced IFN-β promoter activation and IFN-β production confers antiviral activity (10), we decided to investigate if TSA treatment by itself could induce an antiviral state. For this purpose, we compared the cytopathic effect of VSV, the capacity of VSV infection to induce cell death, and the capacity of the virus to multiply on murine fibroblastic L929 cells previously treated or not treated with TSA.

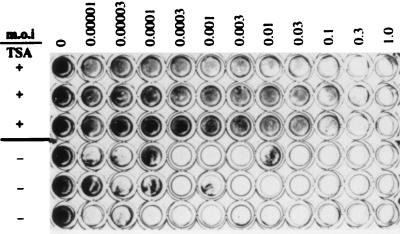

To avoid secondary effects of TSA on cell viability, the time of incubation with TSA and the concentration of TSA were reduced during these experiments to 12.5 ng/ml for 24 h. After TSA treatment, the medium containing TSA was removed and medium containing increasing virus concentrations was added to TSA-treated or untreated cells. As cells were infected with increasing amounts of virus, the proportion of viable cells found 48 h later decreased, as evidenced by the failure to stain with a vital dye. Figure 4 compares the cytopathic effect of VSV infection on the TSA-treated and untreated cells. Vital-dye staining of the cells was quantified using a Titertek Multiskan instrument with a 595-nm filter. For the TSA-treated cells, cell viability was almost completely lost at a MOI of 0.3, whereas under TSA-untreated conditions, cell viability was almost completely lost at a MOI of 0.0003 (Table 3). TSA treatment rendered the murine L929 fibroblast cells 1,000-fold more resistant to VSV infection than the control untreated cells.

FIG. 4.

TSA treatment induces resistance to VSV infection. Confluent monolayers of murine L929 cells were incubated in the absence of TSA (TSA−) or in the presence of 12.5 ng/ml of TSA (TSA+) for 24 h. The medium was then removed, and the cells were infected with increasing MOI of VSV and subsequently stained with a vital dye 48 h after infection.

TABLE 3.

Percent cell viability obtained in the presence or absence of TSA

| MOI | % Cell viability

|

|

|---|---|---|

| +TSA (12.5 ng/ml) | −TSA | |

| 0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 0.00001 | 75.0 | 36.0 |

| 0.00003 | 79.4 | 28.4 |

| 0.0001 | 82.9 | 55.8 |

| 0.0003 | 78.2 | <5 |

| 0.001 | 76.9 | <5 |

| 0.003 | 74.7 | <5 |

| 0.01 | 64.9 | 9.3 |

| 0.03 | 58.9 | <5 |

| 0.1 | 30.9 | <5 |

| 0.3 | <5 | <5 |

The supernatants from TSA-treated and untreated cells, infected as in Fig. 4 at a MOI of 0.1, were collected 24 h after infection and added, after serial 10-fold dilutions, to the corresponding wells of another plate containing L929 cells. As shown in Fig. 5, no cell death was observed after incubation of the cells with the conditioned medium from TSA-treated cells whereas cell death was observed after addition of the conditioned medium from untreated cells, even after dilution of this medium 1,000-fold. This clearly shows that the virus was able to multiply on TSA-untreated cells but not on TSA-treated cells. Two effects can therefore be directly linked to TSA treatment of L929 cells: protection against cell death induced by VSV infection, and inhibition of VSV multiplication. Both these effects are characteristic of an antiviral activity.

TSA-induced antiviral activity is a consequence of IFN production.

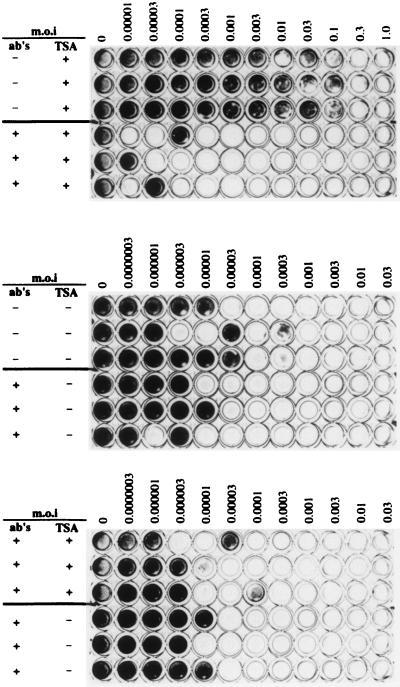

To test if the antiviral state observed after TSA treatment was a consequence of IFN production, we used antibodies directed against and neutralizing IFN-α/β. Murine fibroblast L929 cells were incubated with 12.5 ng of TSA per ml or without TSA for 24 h in the presence or absence of anti-IFN antibodies. After 24 h, the medium was removed and the cells were infected with increasing amounts of VSV either in the presence or in the absence of anti-IFN antibodies. The amount of antibodies used during TSA treatment as well as during VSV infection was sufficient to neutralize 15,000 U of IFN-β per ml.

As shown in Fig. 6 (top panel), the presence of anti-IFN antibodies at this concentration was capable to abolish the TSA-induced antiviral state. The resistance of TSA-treated cells to the VSV cytopathic effect was completely lost in the presence of IFN-neutralizing antibodies. Complete loss of cell viability occurred at a MOI of 0.0003 under TSA-treated conditions with antibody present, compared to the MOI of 0.3 under TSA-treated conditions with no antibody. As previously described (43), IFN-neutralizing antibodies had essentially no effect on the cytopathic effect of VSV control cells (Fig. 6, middle panel). In the presence of IFN-neutralizing antibodies, TSA-treated and untreated cells have approximately the same resistance to VSV infection (Fig. 6 bottom panel; Table 4), further confirming that the TSA-induced antiviral state is due to enhanced, TSA-induced endogenous IFN production.

FIG. 6.

The TSA-induced antiviral state is due to IFN production. (Top) Murine L929 cells seeded in a 96-well plate were incubated with TSA (TSA+), as in Fig. 3, in the presence or absence of antibodies directed against IFN-α/β (ab's) sufficient to neutralize a maximum of 15,000 U of IFN-β per ml. After 24 h, the medium was removed and the cells were infected with increasing amounts of VSV in the presence or absence of anti-IFN antibodies (ab's) sufficient to neutralize a maximum of 15,000 U of IFN-β per ml and subsequently stained with a vital dye 48 h after infection. (Middle) Murine L929 cells were incubated with anti-IFN antibodies (ab's) and VSV infected in the presence of antibodies, as in top panel, except that no TSA was added to the medium (TSA−). (Bottom) Murine L929 cells were incubated with (TSA+) or without (TSA−) TSA in the presence or absence of anti-IFN antibodies (ab's) and VSV infected as in the top panel.

TABLE 4.

Percent cell viability obtained in the presence or absence of TSA and in the presence of anti-IFNα/β antibodies

| MOI | % Cell viability

|

|

|---|---|---|

| +TSA (12.5 ng/ml) + antibodies | −TSA + antibodies | |

| 0 | 100.0 | 100.0 |

| 0.0000003 | 124.0 | 103.9 |

| 0.000001 | 127.4 | 109.0 |

| 0.000003 | 103.5 | 110.0 |

| 0.00001 | 41.7 | 77.9 |

| 0.00003 | 36.6 | 10.2 |

| 0.0001 | 21.5 | <5 |

| 0.0003 | <5 | <5 |

| 0.001 | <5 | <5 |

| 0.003 | <5 | <5 |

| 0.01 | <5 | <5 |

DISCUSSION

Eukaryotic genomes are assembled into a potentially repressive chromatin environment (50). The capacity of eukaryotic organism to maintain some genes in a transcriptionally silent state is essential to successfully carry out key molecular events such as cell development and differentiation (36, 41, 46, 51, 55), cell cycle regulation (7, 25, 26, 47), and regulation of the transient expression of genes which have a very low demand during a cell cycle, whose temporary activation results from extracellular signals (2, 59). Data from genetic as well as biochemical experiments have established that chromatin condensation plays a major role during constitutive gene silencing (17, 60, 61). Histone deacetylation alone (2, 18) or coupled with DNA methylation (35, 44) is important during the maintenance of the repressed state of temporarily induced genes such as the genes regulated by ligand-dependent nuclear receptors. IFN genes belong to a similar class of genes that remain inactive through a cell cycle unless extracellular signals such as viruses or other pathogens temporarily activate them.

In this work we have analyzed the role of histone deacetylation during the establishment of the constitutive silent state of the IFN-β gene. Using ChIP assays, we showed that during the constitutive transcriptionally silent state, histone H4 on the IFN-β promoter is hypoacetylated. TSA treatment of murine fibroblast L929 wt330 cells, carrying a stably integrated muIFN-β promoter, led to the constitutive derepression of the muIFN-β promoter as well as to enhanced kinetics of the virus-induced transcriptional capacity of the IFN-β promoter. As shown by our ChIP assays, the TSA-induced promoter derepression was associated with TSA-induced histone H4 acetylation at the promoter locus. Experiments performed in the presence of cycloheximide indicated that the effect of TSA on the transcriptional capacity of the IFN-β was not mediated by a protein induced during TSA treatment. Immunocytochemistry experiments allowed us to visualize the enhanced production of endogenous IFN after TSA treatment in the absence of virus infection. It is interesting that even though the level of IFN in noninfected, TSA-untreated cells is very low, it is not completely null. Some IFN seems to be present in noninfected, TSA-untreated L929 cells. Titration of the IFN activity present in the supernatant of virus-infected TSA-treated or -untreated cells showed that TSA treatment affected the virus-induced kinetics of activation of the endogenous promoter in a manner similar to that observed with the stably integrated promoter.

Our demonstration of the predominant role of HDAC activity during the regulation of the constitutive repressed state of the IFN-β promoter opens new perspectives concerning the understanding of the negative regulation of this gene. Two families of HDACs have been described in mammals: the family comprising HDACs 1 to 3, which belong to class I HDACs and have similarities to yeast transcriptional repressor protein Rpd3p, and the family comprising HDACs 4 to 6, which belong to class II HDACs and have similarities to yeast HDA1 deacetylase (15, 32). HDACs do not bind to DNA directly but are recruited to specific promoters by transcription factors. Quite often they function in large multiprotein complexes, such as mSin3A, NuRD (nucleosome-remodeling histone deacetylase), MeCP2, and Mi2 (9, 60). In this work, we present data indicating that the NRD II region of the muIFN-β promoter mediates most of the effect of TSA and that deletion of this region mimics the effect of TSA. The NRD II region behaves as the region responsible for the local recruitment of HDAC to the IFN-β promoter region, but the factor(s) directly responsible for this local recruitment remains to be identified.

Since TSA treatment of the cells was able to mimic the effect of virus infection for the activation of the IFN-β promoter, we next investigated if TSA treatment could by itself confer an antiviral activity analogous to the one conferred by IFN-β production. For this purpose, we measured the cytopathic effect of VSV on murine L929 cells treated or not treated with TSA. To avoid secondary effects associated with TSA, we used a much smaller amount of TSA as well as a much shorter period of TSA treatment in these experiments. Despite these milder conditions, a 1,000-fold-increased virus resistance was observed in cells treated with 12.5 ng of TSA per ml for 24 h compared to that in nontreated cells. The VSV-induced cell death, as well as the capacity of the virus to multiply on murine fibroblast L929 cells, was strongly inhibited after incubation of the cells with TSA. Antibodies neutralizing IFN-α/β completely abolished the antiviral effect of TSA, demonstrating that the TSA-induced antiviral state is due to an enhanced TSA-induced IFN production. The effects induced by TSA at concentrations as low as 12.5 ng/ml open the possibility of interesting therapeutic applications. Such applications should be encouraged by the positive therapeutic results that have already been obtained with HDAC inhibitors either in vitro or in vivo (14, 24, 56).

Van Lint et al. have shown that less than 5% of cellular genes have their expression modified after treatment with TSA (54). It would be interesting to determine if this rather restrained number of genes include other IFN or IFN-inducible genes. Chromatin remodeling has been proposed to intervene during the regulation of cytokine gene expression on T cells (1, 48), and TSA-dependent gene activation has been observed for the pleitropic cytokine interleukin-6 (53). It is therefore possible that chromatin remodeling is a regulatory mechanism shared by several cytokine and cytokine-inducible genes during their transition from a silent to an active state and back to a silent transcriptional state.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to Suzanne Chousterman for critical reading of the manuscript and discussions, to Sebastian Navarro for encouragement and fruitful suggestions, and to Eugenio Prieto for photographic work.

This work was supported by the Centre de la Recherche Scientifique (CNRS) and by grants from the Association pour la Recherche sur le Cancer (9994) and CNRS PCV program (PCV098-33). E. Shestakova is the recipient of a CNRS postdoctoral fellowship (until September 2000) and of a fellowship from the Fondation pour la Recheche Médical (FRM) (since October 2000).

REFERENCES

- 1.Agarwal S, Rao A. Modulation of chromatin structure regulates cytokine gene expression during T cell differentiation. Immunity. 1998;9:765–775. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80642-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alland L, Muhle R, Hou H, Jr, Potes J, Chin L, Schreiber-Agus N, DePinho R A. Role for N-Cor and histone deacetylase in Sin3-mediated transcriptional repression. Nature. 1997;387:49–55. doi: 10.1038/387049a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bestor T H. Methylation meets acetylation. Nature. 1998;393:311–312. doi: 10.1038/30613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bonnefoy E, Bandu M-T, Doly J. Specific binding of high-mobility-group I (HMGI) protein and histone H1 to the upstream AT-rich region of the murine beta interferon promoter: HMGI protein acts as a potential antirepressor of the promoter. Mol: Cell Biol. 1999;19:2803–2816. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.4.2803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Braunstein M, Rose A B, Holmes S G, Allis C D, Broach J R. Transcriptional silencing in yeast is associated with reduced nucleosome acetylation. Genes Dev. 1993;7:592–604. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.4.592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Braunstein M, Sobel R E, Allis C D, Turner B M, Broach J M. Efficient transcriptional silencing in Saccharomyces cerevisiae requires a heterochromatin histone acetylation pattern. Mol Cell Biol. 1996;16:4349–4356. doi: 10.1128/mcb.16.8.4349. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Brehm A, Miska E A, McCance D J, Reid J L, Bannister A J, Kouzarides T. Retinoblastome protein recruits histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nature. 1998;391:597–600. doi: 10.1038/35404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Civas A, Dion M, Vodjdani G, Doly J. Repression of the murine interferon alpha 11 gene: identification of negative acting sequences. Nucleic Acids Res. 1991;19:4497–4502. doi: 10.1093/nar/19.16.4497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Davie J R, Spencer V A. Control of histone modifications. J Cell Biochem. 1999;32/33:141–148. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(1999)75:32+<141::aid-jcb17>3.0.co;2-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.DeMayer E, DeMayer-Guignard J. Interferons and other regulatory cytokines. New York, N.Y: John Wiley and Sons, Inc.; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Doly J, Civas A, Navarro S, Uze G. Type I interferons: expression and signalization. Cell Mol Life Sci. 1998;54:1109–1121. doi: 10.1007/s000180050240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goodbourn S, Burstein H, Maniatis T. The human β-interferon gene enhancer is under negative control. Cell. 1986;45:601–610. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90292-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goodbourn S, Maniatis T. Overlapping positive and negative regulatory domains of the human β-interferon gene. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1988;85:1447–1451. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.5.1447. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Grignani F, De Matteis S, Nervi C, Tomasoni L, Gelmetti V, Cioci M, Fanelli M, Ruthardt M, Ferrara F F, Zamir I, Seiser C, Grignani F, Lazar M A, Minucci S, Pelicci P G. Fusion proteins of the retinoic acid receptor-α recruit histone deacetylase in promyelocytic leukaemia. Nature. 1998;391:815–818. doi: 10.1038/35901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grozinger C M, Hassig C A, Schreiber S L. Three proteins define a class of human histone deacetylases related to yeast Hdap1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4868–4873. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.9.4868. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grunstein M. Histone acetylation in chromatin structure and transcription. Nature. 1997;389:349–352. doi: 10.1038/38664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartzog G A, Winston F. Nucleosomes and transcription: recent lessons from genetics. Curr Opin Genet Dev. 1997;7:192–198. doi: 10.1016/s0959-437x(97)80128-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Heinzel T, Lavinsky R M, Mullen T-M, Söderström M, Laherty C D, Torchia J, Yang W-M, Brard G, Ngo S D, Davie J R, Seto E, Eisenman R N, Rose D W, Glass C K, Rosenfeld M. A complex containing N-CoR, mSin3 and histone deacetylase mediates transcriptional repression. Nature. 1997;387:43–48. doi: 10.1038/387043a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ikeda K, Steger D J, Eberharter A, Workman J L. Activation domain-specific and general transcription stimulation by native histone acetyltransferase complexes. Mol Cell. 1999;19:855–863. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.1.855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jones P L, Veenstra G J C, Wade P A, Vermaak D, Kass S U, Landsberger N, Strouboulis J, Wolffe A P. Methylated DNA and MeCP2 recruit histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Nat Genet. 1998;19:187–191. doi: 10.1038/561. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Keller A D, Maniatis T. Identification and characterization of a novel repressor of β-interferon gene expression. Genes Dev. 1991;5:868–879. doi: 10.1101/gad.5.5.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee H-Y, Archer T K. Prolonged glucocorticoid exposure dephosphorylates histone H1 and inactivates the MMTV promoter. EMBO J. 1998;17:1454–1466. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.5.1454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lin R, Heylbroeck L, Pitha P M, Hiscott J. Virus-dependent phosphorylation of the IRF-3 transcription factor regulates nuclear translocation, transactivation potential, and proteasome-mediated degradation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:2986–2996. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.5.2986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lin R J, Nagy L, Inoue S, Shao W, Miller W H, Evans R M. Role of the histone deacetylase complex in acute promyelocytic leukaemia. Nature. 1998;391:811–814. doi: 10.1038/35895. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo R X, Postigo A A, Dean D C. Rb interacts with histone deacetylase to repress transcription. Cell. 1998;92:463–473. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80940-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Magnaghi-Jaulin L, Groisman R, Naguibneva I, Robin P, Lorain S, Le Villain J P, Troalen F, Trouche D, Harel-Bellan A. Retinoblastoma protein represses transcription by recruiting a histone deacetylase. Nature. 1998;391:601–604. doi: 10.1038/35410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Maniatis T, Whittemore L, Fan W, C, Keller A D, Palombella V J, Thanos D N. Positive and negative control of human interferon-β gene expression. In: McKnight S L, Yamamoto K P, editors. Transcriptional regulation. Cold Spring Harbor, N.Y: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory Press; 1992. pp. 1193–1220. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Maniatis T, Falvo J V, Kim T H, Kim T K, Lin C H, Parekh B S, Wathelet M G. Structure and function of the interferon-beta enhanceosome. Cold Spring Harbor Symp Quant Biol. 1998;63:609–620. doi: 10.1101/sqb.1998.63.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Masumi A, Wang I M, Lefebvre B, Yang X-T, Nakatami Y, Ozato K. The histone acetylase PCAF is a phorbol-ester-inducible coactivator of the IRF family that confers enhanced interferon responsiveness. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:1810–1820. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.3.1810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Merika M, Williams A J, Chen G, Collins T, Thanos D. Recruitment of CBP/p300 by the IFNβ enhanceosome is required for synergistic activation of transcription. Mol Cell. 1998;1:277–287. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80028-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minucci S, Horn V, Bhattacharyya N, Russanova V, Ogryzko V V, Gabriele L, Howard B H, Ozato K. A histone deacetylase inhibitor potentiates retinoid receptor action in embryonal carcinoma cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:11295–11300. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.21.11295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Miska E A, Karlsson C, Langley E, Nielsen S J, Pines J, Kouzarides T. HDAC4 deacetylase associates with and represses the MEF2 transcription factor. EMBO J. 1999;18:5099–5107. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.18.5099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mogensen K E, Bandu M-T. Kinetic evidence for an activation step following binding of human interferon α2 to the membrane receptors of Daudi cells. Eur J Biochem. 1983;134:355–364. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1983.tb07575.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Munshi N, Merika M, Yie J, Senger K, Chen G, Thanos D. Acetylation of HMGI(Y) by CBP turns off IFNβ expression by disrupting the enhanceosome. Mol Cell. 1998;2:457–467. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80145-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nan X, Ng H-H, Johnson C A, Laherty C D, Turner B M, Eisenman R N, Bied A. Transcriptional repression by the methyl-CpG-binding protein MeCP2 involves a histone deacetylase complex. Nature. 1998;393:386–389. doi: 10.1038/30764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Nemer M. Histone deacetylase mRNA temporarly and spatially regulated in its expression in sea urchin embryos. Dev Growth Differ. 1998;40:583–590. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-169x.1998.t01-4-00002.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nightingale K P, Wellinger R E, Sogo J M, Becker P B. Histone acetylation facilitates RNA polymerase II transcription of the Drosophila hsp26 gene in chromatin. EMBO J. 1998;17:2865–2876. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.10.2865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nourbakhsh M, Hauser H. Interferon-β promoters contain a DNA element that acts as a position-independent silencer on the NF-κB site. EMBO J. 1993;12:451–459. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1993.tb05677.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nourbakhsh M, Hauser H. Constitutive silencing of IFN-β promoter is mediated by NRF (NF-κB-repressing factor), a nuclear inhibitor of NF-κB. EMBO J. 1999;18:6415–6425. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.22.6415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ogryzko V V, Schiltz R L, Russanova V, Howard B H, Nakatani Y. The transcriptional coactivators p300 and CBP are histone acetyltransferases. Cell. 1996;87:953–959. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)82001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Neill L P, Keohane A M, Lavender J S, McCabe V, Heard E, Avner P, Brockdorff N, Turner B M. A developmental switch in H4 acetylation upstream of Xist plays a role in X chromosome inactivation. EMBO J. 1999;18:2897–2907. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.10.2897. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parekh B S, Maniatis T. Virus infection leads to localized hyperacetylation of histones H3 and H4 at the IFN-β promoter. Mol Cell. 1999;3:125–129. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80181-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pine R. Constitutive expression of an ISGF2/IRF1 transgene leads to interferon-independent activation of interferon-inducible genes and resistance to virus infection. J Virol. 1992;66:4470–4478. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.7.4470-4478.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Razin A. CpG methylation, chromatin structure and gene silencing—a three-way connection. EMBO J. 1998;17:4905–4908. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.17.4905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ren B, Chee K J, Kim T H, Maniatis T. PRDI-BF1/Blimp-1 repression is mediated by corepressors of the Groucho family of proteins. Genes Dev. 1999;13:125–137. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.1.125. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Ryan J, Llinas A J, White D A, Turner B M, Sommerville J. Maternal histone deacetylase is accumulated in the nuclei of Xenopus oocytes as protein complexes with potential enzyme activity. J Cell Biol. 1999;112:2441–2452. doi: 10.1242/jcs.112.14.2441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Sambucetti L C, Fischer D D, Zabludoff S, Kwon P O, Chamberlain H, Trogani N, Xu H, Cohen D. Histone deacetylase inhibition selectively alters the activity and expression of cell cycle proteins leading to specific chromatin acetylation and antiproliferative effects. J Biol Chem. 1999;49:34940–34947. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.49.34940. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shannon M F, Himes S R, Attema J. A role for the architectural transcription factors HMGI(Y) in cytokine gene transcription in T cells. Immunol Cell Biol. 1998;76:461–466. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1711.1998.00770.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Smith C L, Hager G L. Transcriptional regulation of mammalian genes in vivo. A tale of two templates. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:27493–27496. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.44.27493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Struhl K. Fundamentally different logic of gene regulation in eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Cell. 1999;98:1–4. doi: 10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80599-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Thompson E M, Legouv E, Renard J-P. Mouse embryos do not wait for the MBT:chromatin and RNA polymerase remodeling in genome activation at the onset of development. Dev Genet. 1998;22:31–42. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1998)22:1<31::AID-DVG4>3.0.CO;2-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ura K, Kurumizaka H, Dimitrov S, Almouzni G, Wolffe A P. Histone acetylation: influence on transcription, nucleosome mobility and positioning, and linker histone-dependent transcriptional repression. EMBO J. 1997;16:2096–2107. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.8.2096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vanden Berghe W, De Bosscher K, Boone E, Plaisance S, Haegeman G. The nuclear factor-κB engages CBP/p300 and histone acetyltransferase activity for transcriptional activation of the interleukin-6 gene promoter. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:32091–32098. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.45.32091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Van Lint C, Emiliani S, Verdin E. The expression of a small fraction of cellular genes is changed in response to histone hyperacetylation. Gene Expression. 1996;5:245–253. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Vermaak D, Wolffe A P. Chromatin and chromosomal controls in development. Dev Genet. 1998;22:1–6. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6408(1998)22:1<1::AID-DVG1>3.0.CO;2-A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Warrell R P, He L-Z, Richon V, Calleja E, Pandolfi P P. Therapeutic targeting of transcriotion in acute promyelocytic leukemia by use of an inhibitor of histone deacetylase. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1998;90:1621–1625. doi: 10.1093/jnci/90.21.1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wathelet M G, Lin C H, Parekh B S, Ronco L V, Howley P M, Maniatis T. Virus infection induces the assembly of coordinately activated transcription factors on the IFN-β enhancer in vivo. Mol Cell. 1998;1:507–518. doi: 10.1016/s1097-2765(00)80051-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Whittemore L-A, Maniatis T. Postinduction repression of the β-interferon gene is mediated through two positive regulatory domains. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;64:1329–1337. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.20.7799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wolffe A P. Sinful repression. Nature. 1997;387:16–17. doi: 10.1038/387016a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Workman J L, Kingston R E. Alteration of nucleosome structure as a mechanism of transcriptional regulation. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:545–579. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wu C. Chromatin remodeling and the control of gene expression. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28171–28174. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Yoneyama M, Suhara W, Fukuhara Y, Fukuda M, Nishida E, Fujita T. Direct triggering of the type I interferon system by virus infection: activation of a transcription factor complex containing IRF-3 and CBP/p300. EMBO J. 1998;17:1087–1095. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.4.1087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zinn K, DiMaio D, Maniatis T. Identification of two distinct regulatory regions adjacent to the human β-interferon gene. Cell. 1983;34:865–879. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(83)90544-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Zinn K, Maniatis T. Detection of factors that interact with the human β-interferon regulatory region in vivo by DNAse I footprinting. Cell. 1986;45:611–618. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90293-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]