Abstract

This article describes the process and results associated with the organizational-level recruitment of Black barbershops into Fitness in the Shop (FITShop), a 6-month barbershop-based intervention study designed to promote physical activity among Black men. Organizational-level recruitment activities included (1) a telephone call to prospective barbershop owners to assess their interest and eligibility for participation, (2) an organizational eligibility letter sent to all interested and eligible barbershops, (3) a visit to interested and eligible barbershops, where a culturally sensitive informational video was shown to barbershop owners to describe the study activities and share testimonies from trusted community stakeholders, and (4) a signed agreement with barbershop owners and barbers, which formalized the organizational partnership. Structured interviews were conducted with owners of a total of 14 enrolled barbershops, representing 30% of those determined to be eligible and interested. Most enrolled shops were located in urban settings and strip malls. Barbershop owners were motivated to enroll in the study based on commitment to their community, perceived client benefits, personal interest in physical activity, and a perception that the study had potential to make a positive impact on the barbershop and on reducing health disparities. Results offer important insights about recruiting barbershops into intervention trials.

Keywords: community intervention, health disparities, health promotion, community-based participatory research, health research, men’s health, Black/African American, minority health, community organization

INTRODUCTION

Compared with other population segments, such as women and White men, Black men experience disproportionately high rates of nearly all chronic diseases, including cancer, diabetes, and cardiovascular disease. Despite their existing health disparities, evidence suggests that Black men are less likely to join and be retained in both clinical- and community-based health promotion research studies (Blumenthal, Sung, Coates, Williams, & Liff, 1995; Diaz, Mainous, McCall, & Geesey, 2008). Barriers to participation among Black men include a history of medical mistrust, stigma of having an illness, and the belief that research will not benefit them or their communities (Spence & Oltmanns, 2011). Additional barriers include low socioeconomic status, which limits flexibility to participate, limited access to primary care, low educational levels, and social deprivation (Byrd et al., 2011). Selection of appropriate recruitment venues has been found to reduce participation barriers among all racial/ethnic minority groups (George, Duran, & Norris, 2014).

To effectively enroll and retain Black men in health-related research studies, it is imperative to engage them in their naturally frequented settings, ones where they are comfortable when approached with information about joining a research trial. While churches are a location that has been traditionally used for recruitment, this setting may not be ideal for recruiting and hosting studies for Black men. In a study by Linnan et al. (2011), only 50% of Black men reported attending church at least once per month. In a study by Weinrich, Greiner, Reis-Starr, Yoon, and Weinrich (1998), 29 worksites in South Carolina were recruited to enroll low-income men into a prostate education program and yielded a primarily Black male participant sample (64%). Historically Black colleges and universities have also been used as sites for recruitment of Black men (Ford & Goode, 1994). Although churches, worksites, and historically Black colleges and universities have been observed to be effective recruitment settings for ethnic minority participants, many Black men are not reached through these settings.

Just as beauty salons are effective sites for promoting health among women, barbershops are an ideal setting for enrolling Black men into intervention studies (Linnan, D’Angelo, & Harrington, 2014). The barbershop is an effective site for recruiting Black males and hosting interventions for this priority population for a variety of reasons. First, barbershops are located in all communities—urban, rural, suburban, large, and small. Within any given Black barbershop, male customers consist of diverse backgrounds (age, education level, occupation, etc.), affording opportunities to reach many types of Black men. Additionally, Black men visit barbershops regularly, return often, and receive service from a specific barber with whom they have a trusted relationship with the potential of aiding behavior modification sustainability (Luque, Ross, & Gwede, 2014). Finally, the barbershop, coined as “the Black man’s country club,” is a setting where Black men regularly socialize (Releford, Frencher, & Yancey, 2010, p. 186). Thus, the barbershop is a significant and culturally relevant venue to reach Black men for health promotion activities (Linnan et al., 2014).

As presented in a recent systematic review of weight loss, physical activity, and dietary interventions involving Black men by Newton, Griffith, Kearney, and Bennett (2014), community-based sites, such as barbershops, are increasingly being used as locations for hosting health promotion interventions for Black males. Previous barbershop-based health promotion programs for Black men have focused on behaviors such as prostate cancer screening (Browne, 2007; Cowart, Brown, & Biro, 2004; Frencher et al., 2016; Luque et al., 2010), hypertension screening and control (Hess et al., 2007; Pepe, 1989; Rader, Elashoff, Niknezhad, & Victor, 2013; Victor et al., 2011; Yancy, 2011), nutrition (Magnus, 2004), and physical activity (Hood et al., 2015; Linnan et al., 2011). Additional barbershop-based efforts have focused on providing sex education to young, heterosexual Black males (Johnson, Speck, Bowdre, & Porter, 2015), with an emphasis on HIV risk reduction (Jemmott, Jemmott, Lanier, Thompson, & Baker, 2016; Nathan, 2013; Wilson et al., 2014). Though most barbershop-based health promotion programs have been conducted in urban settings, recent studies have demonstrated the feasibility of promoting health in Black barbershops located in rural communities (Hall et al., 2016; Luque et al., 2015). Overall, barbershop-based programs have employed a wide variety of health promotion methods, including using barbershops as locations for delivering group education about various health topics, or using barbershops as sites for conducting health communication interventions. Some programs have also trained barbers to directly deliver preventive health information to clients, as well as provide disease screenings to their clients.

While there is a growing body of literature to support effective approaches for enrolling individual Black males for study participation, very little information is available on strategic efforts to initially engage and formally establish partnerships with leaders of the actual organizations where Black men can be enrolled and participate in community-based intervention research studies (Jones, Steeves, & Williams, 2009). Before recruiting Black males for participation in barbershop-based intervention trials, it is first necessary for researchers and practitioners to engage and gain the support of organizational leaders, such as barbershop owners, who function as gatekeepers within this important community venue (Renert, Russell-Mayhew, & Arthur, 2013). Barbershop-based researchers have emphasized the importance of gaining “buy-in” from barbershop owners to enhance organizational recruitment for study site enrollment (Hall et al., 2016). In contrast, the absence of buy-in from barbershop owners, and barbers has been recognized as a potential barrier to the successful implementation of barbershop-based health promotion initiatives (Brawner et al., 2013; Hood et al., 2015; Roy, 2016). Also, similar to Black salon owners, Black barbershop owners, as trusted and influential gatekeepers, can ultimately encourage and enhance participation in health promotion initiatives among the men who visit their barbershops (Apantaku-Onayemi, 2013).

Our study, Fitness in the Shop (FITShop), employed a community-based participatory research (CBPR) approach to develop effective strategies for recruiting Black barbershops as health promotion intervention study sites. We successfully recruited and retained 14 Black barbershops for the 6-month barbershop-based FITShop intervention study. The purpose of this article is to describe strategic organizational-level barbershop recruitment procedures and enrollment results for FITShop, present structured interview results from partnering barbershop owners, and to present the characteristics of enrolled barbershops. This article highlights the essential link between research and practice, by offering effective strategies that will assist future community-based researchers with overcoming barriers to recruiting Black barbershops as sites for intervention trials, to consequently ensure successful implemental, and increase health promotion program participation among Black males.

METHOD

Institutional review board approval for the FITShop study was awarded by the University of North Carolina and North Carolina Central University Offices of Human Research Ethics (IRB #10–1903).

Barbershop Eligibility

To be eligible for the study, barbershops needed to (1) have Black males as their primary clientele, (2) serve more than 65 customers per week, and (3) be licensed and independently owned. Shops were ineligible for participation if they were part of a franchise, because they have a large walk-in clientele and a less stable customer base. Additionally, shops were eligible to serve as a study site if the research team received written consent from the barbershop owner and at least one barber in the shop.

North Carolina BEAUTY and Barbershop Advisory Board

Guided by principles of CBPR, which encourages collaboration and shared power between researchers and community members to address a common issue (Israel, Eng, Shulz, & Parker, 2012), the FITShop design was developed in partnership with the North Carolina (NC) BEAUTY and Barbershop Advisory Board. Convened by an interdisciplinary team of academic researchers in 2000, the NC BEAUTY and Barbershop Advisory Board is a committed group of cosmetology industry leaders (i.e., owners, barbers, stylists, policy makers, educators, product distributors) and community stakeholders who have helped guide a series of community-based health intervention studies based primarily in Black beauty salons and barbershops throughout North Carolina (Linnan, Thomas, D’Angelo, & Ferguson, 2012).

The Advisory Board provided invaluable insight, suggestions, and direction for all FITShop organizational recruitment materials and activities. In particular, it was imperative to gain the perspectives and suggestions of male Advisory Board members regarding the development of relevant and culturally appropriate strategies for engaging and recruiting barbershop owners for study site enrollment. As key community stakeholders and collaborative research partners on the FITShop team, male Advisory Board members actively participated in the development of the (1) barbershop recruitment protocol, (2) recruitment materials, and (3) the FITShop promotional video shown during shop recruitment visits. During the development of the FITShop promotional video, Advisory Board members provided critical feedback that shaped the final product. After viewing an initial recording of the video, Advisory Board members were asked (1) What information do you think could be taken out? (2) How appropriate is the video in terms of length? (3) Is there anything that needs to be added to the video? (4) Are the video characters relatable? and (5) Does the video serve the purpose of getting a barbershop owner interested in FITShop? The Advisory Board members’ feedback and suggestions were incorporated into edits for the final FITShop promotional video. Throughout the recruitment planning process, several Advisory Board meetings and an intervention planning retreat were held to collaboratively design effective recruitment strategies as well as to identify themes, messages, and images that would be appealing to African American men. Advisory Board members also suggested prospective barbershops for study site participation.

Barbershop Recruitment and Enrollment Procedures

Recruitment of barbershops occurred between February and April 2012.

Initial Phone Call.

The first organizational-level barbershop recruitment activity involved contacting prospective barbershops to assess their potential interest and eligibility for study site enrollment. For a fee of $25, our research team purchased a listing of licensed barbershops in four North Carolina counties (Chatham, Durham, Orange, and Wake) from the North Carolina Board of Barber Examiners. Additionally, referrals of potentially interested and eligible shops were accepted from Advisory Board members. In February, using a scripted call guide, four trained research team members (three Black females and one White female) called all prospective barbershops (N = 283) and asked to speak with the barbershop owner in order to determine their eligibility and interest.

Organizational Eligibility Letter.

Following the initial phone call, all eligible barbershops that expressed an interest in serving as a study site received a mailed letter to thank them for their interest and confirm their organizational eligibility for the FITShop study. The letter also provided a brief history of the research team’s experience and commitment to partnering with barbershops and beauty salons throughout North Carolina for health promotion research studies and was enclosed with a fact sheet about the FITShop study.

Barbershop Visit.

After sending out organizational eligibility letters, an in-person visit was scheduled with each eligible barbershop that expressed an interest in serving as a FITShop study site. The purpose of the visit was to meet with the barbershop owner (or manager) to discuss study requirements, benefits of participation, and to finalize the barbershop enrollment. Barbershop visits occurred during March and April, typically on nonbusy days and times (i.e., Monday–Wednesday and morning hours). The barbershop visit protocol consisted of (1) identifying the shop owner or manager, (2) using a series of scripted talking points to guide the recruitment discussion, and (3) showing a short FITShop recruitment video that was produced with help from the NC BEAUTY and Barbershop Advisory Board. The recruitment video (see https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3brsxQpbMGI; FITShopUNC, 2012) was almost 7 minutes in length and provided an overview of the study design and purpose. The video was designed to motivate organizations to join the study through featured testimonials by Black male NC BEAUTY and Barbershop Advisory Board members who formally endorsed the FITShop initiative and emphasized the importance of promoting physical activity in barbershops. The video also featured owners and barbers who discussed their key role in supporting customers to live healthy lifestyles. Finally, each barbershop visit concluded with the review and signing of a study agreement form by the barbershop owner and one barber. Specifically, the signed study agreement form, similar to a memorandum of understanding, formalized the barbershop’s enrollment status, and served as an organizational-level consent to form a partnership between the research team and the barbershop to conduct the FITShop study with customers. The form included a study overview and a list of roles, responsibilities, and benefits for barbershop participation. At least one owner and one barber pair was required to sign the study agreement form per shop. Barbers were encouraged to sign up, in an effort to strengthen solidarity among all key stakeholders within the organization. This process was created to enhance the organizational-level commitment for full participation before any barbershop customers were invited to join the study.

Measures

Structured Interviews.

Trained research team members administered in-person structured interviews to all enrolled owners, at the owners’ convenience. During each interview, the research team member read questions and response options aloud and recorded the owners’ verbal responses. The structured interview consisted of both closed and open-ended questions. Closed-ended questions assessed the basic demographic characteristics of owners who supported the FITShop study within their barbershops, as well as their health-related characteristics, including self-reported rating of health, insurance status, physical activity levels, nutrition, and smoking status. An assessment of owners’ health characteristics was included because previous barbershop-based research has suggested that the health status of barbershop owners predicts outcomes of barbershop-based health promotion programs (Linnan, Emmons, & Abrams, 2002). All health-status questions were adapted from 2011 North Carolina Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) items (North Carolina BRFSS, 2011). Additional closed-ended questions assessed organizational characteristics for each owners’ barbershop, including the length of operation, an estimate of customers served weekly, total hours of weekly operation, and total number of barbers employed in the shop. The structured interview also contained an open-ended question, “What is the main reason you joined the study?” which was included to assist the research team with identifying barbershop owners’ specific reasons for endorsing the FITShop study at their barbershops. The structured interview took about 30 minutes to complete. All enrolled owners received $25 for completing the structured interview. Additionally, barbershop owners were informed that, on enrollment, they would have the opportunity to attend to a series of four free business development workshop sessions led by professional experts. The workshops were made available through a partnership with the North Carolina Institute of Minority Economic Development (NCIMED), a statewide non-profit organization focused on business and economic growth through effective business diversity. A list of NCIMED workshop topics was presented to barbershop owners during the structured interviews. Session topics were selected based on owners’ interest. Designed as a retention strategy that complemented the financial empowerment control arm of the FITShop intervention study (see Hood et al., 2015), the business development workshops were scheduled to occur periodically over the course of the 6-month intervention. Each 2-hour session took place at a centrally located community space on a Monday evening to accommodate owners’ and barbers’ work schedules, and a catered dinner was provided. The first hour covered a variety of topics, including, Small Business Resources, Business Expansion, and Social Media (i.e., marketing strategies), Taxes and Workers’ Compensation, and Business Plan Basics. During the second hour, the research team provided study updates and addressed any owner/barber issues related to the FITShop intervention and control activities. Session attendance varied by topic with the greatest participation for Taxes and Workers’ Compensation, followed by the Small Business Resources session. On average, the value of the financial workshops was rated 9.8 (range = 9.0–10.0) by attendees. A detailed description of the FITShop study intervention and control components is presented in Hood et al. (2015).

Data Analysis

Descriptive analysis was conducted using SPSS Version 23.0 to summarize demographic and health behavior characteristics of enrolled barbershop owners, as well as characteristics of the enrolled shops. Content analysis, a method of systematically categorizing qualitative information (Saldana, 2013), was used to summarize owners’ responses to the open-ended question, “What is the main reason you joined the study?” providing insight for why owners chose to enroll their shops as a FITShop study site. Each owner’s open-ended response was independently reviewed by two postdoctoral fellows on the research team, who were trained and experienced in qualitative analysis. During the independent review, each fellow documented emergent themes pertaining to owners’ reasons for enrolling their shops as a FITShop study site and identified direct quotes to support these emergent themes. Independently derived themes and summaries from the content analyses were compared, and final thematic summaries and direct quotes for inclusion were approved by the lead study investigator.

RESULTS

Organizational-Level Recruitment Results

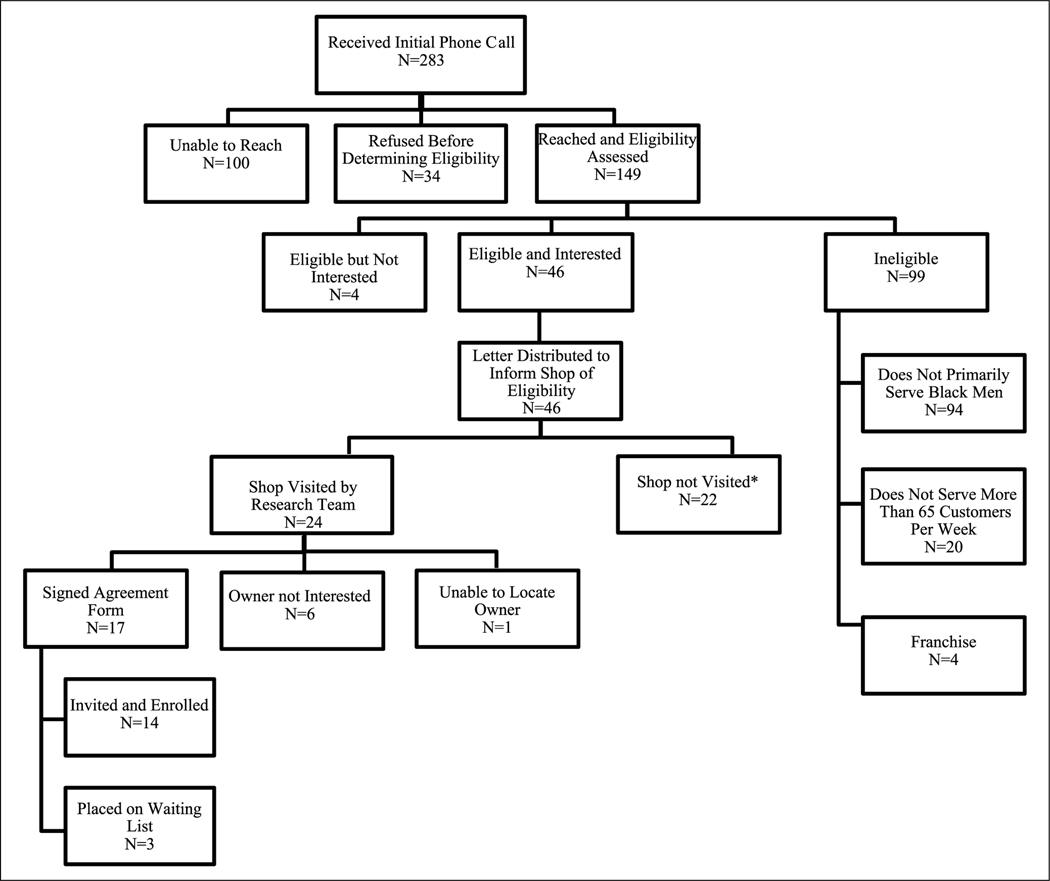

Organizational-level recruitment results for the FITShop study are presented in a comprehensive recruitment response diagram in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1. FITShop (Fitness in the Shop) Recruitment Response Diagram.

*Not visited due to refusal to scheduling or unable to reach a person of authority in the barbershop.

Of the 283 barbershops on the initial list of prospective barbershops, our research staff was unable to reach 100 shops due to nonworking phone numbers, wrong numbers, or unanswered calls. In an additional 34 shops, owners refused to respond to the eligibility questions during the initial phone call. Of the 149 shops that responded to eligibility questions over the phone, 99 shops were ineligible because they were either a franchise, did not serve predominantly Black customers, or did not serve at least 65 customers per week. Forty-six were eligible and interested in the study and four were eligible but not interested (see Figure 1).

Of the 46 shops classified as eligible and interested, we only visited 24 because we were unable to reach the owner or the owner refused to schedule an appointment in 22 shops. Of the 24 shops visited, 17 signed study agreement forms, 6 were no longer interested, and we were unable to arrange a meeting with the owner of one shop. The FITShop 2-arm controlled intervention trial was designed to enroll a total of 14 barbershops (i.e., seven intervention shops and seven control shops). Of the 17 shops that signed agreements, 14 were invited to join the study and 3 were placed on a waitlist (see Figure 1). The waitlisted shops allowed the potential for enrolled shops to be replaced during the intervention study should attrition occur, in an effort to maintain equally sized intervention and control study arms.

During our recruitment and enrollment phase, specific reasons were documented for shops being classified as “refusals.” In particular, four shops determined to be eligible during the initial call were later classified as refusals because the shop owners directly expressed that they were not interested in participating in the FITShop study at the time. Additionally, some shop owners (n = 6), who were initially interested in the study over the phone, were later classified as refusals after the shop visit because while the owner was interested, no barbers in the shop were interested in having the shop serve as a FITShop study site, making them ineligible. These shops were removed from consideration because it was important to have barber support, in addition to owners, since they had more one-on-one contact and influence with customers.

Characteristics of Successfully Recruited Barbershops

Owners.

A total of 15 barbershop owners from 14 enrolled shops (one shop had two co-owners) signed study agreement forms to enroll their shops. All enrolled owners were male and were an average age of 42 years (range = 23–67 years). On average, owners of enrolled shops had been barbershop owners for approximately 6 years (range = less than 1 year-22 years).

Health characteristics of owners who enrolled their shops as FITShop study sites is presented in Table 1. In the table, owners’ health characteristics are compared to corresponding 2011 North Carolina BRFSS data for Black males, since the FITShop survey items (assessed in 2012) were derived from the 2011 North Carolina BRFSS. Additionally, subsequent years for North Carolina BRFSS survey did not contain the same health characteristics items as 2011 and therefore could not be compared to the barbershop owners’ data.

TABLE 1.

FITShop Barbershop Owners’ Self-Reported Health Characteristics Compared With 2011 North Carolina BRFSS Data for Black Males

| Health Assessment Item | Owner (n = 15), % | BRFSS (2011; Black Males in NC), % |

|---|---|---|

|

| ||

| Good or very good health rating | 68.0 | 66.6 |

| Has health insurance | 64.3 | 69.7 |

| Has a regular health care provider | 71.4 | 52.9 |

| Eats at least five servings of fruits and vegetables per day | 35.7 | 11.3 |

| Gets moderate physical activity at least 5 times per week | 57.1 | 45.4 |

| Engages in strength training at least twice per week | 85.7 | 39.4 |

| Current smoker | 0.0 | 29.4 |

NOTE: FITShop = Fitness in the Shop; BRFSS = Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System; NC = North Carolina.

Overall, enrolled owners’ self-reported health characteristics indicated that they were similar to or healthier than most Black males in North Carolina, when compared to North Carolina BRFSS data for corresponding items. On a self-rating of health status scale, most owners (68%) reported that their health was “very good” or “good,” which was similar to BRFSS self-report data for Black men in North Carolina (66.6%; North Carolina BRFSS, 2011). Barbers who enrolled their shops in the study had a slightly lower rate of health care coverage than the rates for Black males in North Carolina (64.3% vs. 69.7), based on the 2011 North Carolina BRFSS data (North Carolina BRFSS, 2011). Also, compared with the 2011 North Carolina BRFSS data for Black males, owners who enrolled their shops as FITShop study sites were more likely to have a regular health care provider (71.4% vs. 52.9%), more likely to meet daily fruit and vegetable recommendations (35.7% vs. 11.3%), more likely to meet physical activity recommendations (57.1% vs. 45.4%), and more likely to meet recommendations for strength training (85.7% vs. 39.4%). Compared to the 29% of Black males who self-reported as current smokers in 2011 North Carolina BRFSS data (North Carolina BRFSS, 2011), none of the Barbers who enrolled in the FITShop study reported that they were current smokers.

When owners were asked, “What is the main reason you joined the study?” responses covered a variety of reasons. Owners’ most frequently mentioned reason for enrolling their barbershop in the study was because of their personal commitment to the community. For example, one owner indicated that using his shop as a study site would help to maintain his community involvement, saying “I try my best to be involved in [the] community. . . This [FITShop] study will help me to stay connected.” Moreover, owners also reported that they joined the study because they perceived it to be beneficial to their clients, such as noting that FITShop is an “opportunity to give back to clients.” In particular, several owners noted that FITShop would increase their ability to educate clients about physical activity, similar to one owner’s suggestion that study participation would allow him and his employees to “know more about fitness so we can help our customers.” Several owners indicated that they were interested in enrolling their barbershops as a FITShop study site because they as owners were personally interested in health and physical activity. Specifically, some men mentioned their own need to become more physically active. One owner noted FITShop’s potential to positively influence the health consciousness of the barbershop as a reason for enrolling his shop as a study site, saying that it would “bring more health consciousness to the shop.” Finally, FITShop’s promising positive impact on Black men’s health was provided as a reason for owners’ interest in enrolling their shops. For example, one owner noted that FITShop is a “good idea, especially for young men [and] especially Black men who have health disparities, [such as] family members with diabetes.”

Barbershops.

A summary of the general characteristics of enrolled barbershops is presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

General Characteristics of Enrolled Barbershops (N = 14)

| Barbershop ID | Length of Operationa (years) | Weekly Customers | Weekly Hours | Barbers Employed in Shopb (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||

| A | 16 | 60 | 57 | 6 |

| B | 4 | 115 | 49 | 2 |

| C | 3 | 500 | 55 | 7 |

| D | 2 | 400 | 65 | 7 |

| E | 2 | 110 | 50 | 5 |

| F | 4 | 100 | 48 | 3 |

| G | 25 | 115 | 38.5 | 2 |

| H | 6 | 99 | 63 | 5 |

| I | 0 | 70 | 47.5 | 2 |

| J | 3 | 200 | 54 | 5 |

| K | 5 | 77 | 58.5 | 6 |

| L | 4 | 300 | 41.5 | 5 |

| M | 18 | 120 | 45 | 3 |

| N | 2 | 150 | 67 | 5 |

| Average | 6.7 | 173 | 53 | 5 |

Rounded up by 0.5 or down by 0.4 to calculate whole years.

Includes both licensed and apprentice barber.

On average, enrolled barbershops (79% urban, 21% rural) had been in their current locations for approximately 6.7 years (range = 0–25 years). Overall, enrolled barbershops served an average of 173 customers per week (range = 60–500) and were open for business an average of 53 hours per week (range = 38.5–67.0). Collectively, there were 63 barbers employed across the enrolled barbershops, with each shop having an average of approximately 5 barbers per shop (range = 2–7).

DISCUSSION

There is a growing interest in barbershops as an important setting for research and practice to address health disparities among Black males, yet there is a dearth of information available that focuses on the strategic recruitment of the barbershop venue. In particular, few research articles have documented the processes of how barbershop owners were engaged to enroll their shops as study sites. To our knowledge, the only other research article that specifically focuses on strategic recruitment of barbershops was published by Hart et al. (2008).

Several barbershop-based health studies in the literature have employed organizational recruitment and owner engagement strategies similar to FITShop, including sending out an introductory letter and study information sheet to shops (Cowart et al., 2004; Hart et al., 2008), calling shop owners to assess their interest in eligibility for participation (Cowart et al., 2004; Moore et al., 2016), and sending research staff to barbershop to have in-person visits with owners to provide detailed study information (Baker et al., 2012; Hart et al., 2008). While some studies have only discussed working with community advisors to identify and gain access to prospective shops for study participation (Hall et al., 2016; Luque et al., 2011), Hart et al. (2008), like the FITShop team, worked with a group of community advisors to develop culturally sensitive recruitment materials and approaches.

Continuous improvement in recruitment strategies is essential when effectively recruiting minority populations in research studies (Nicholson, Schwirian, & Groner, 2015). An effective strategy employed in this study includes the implementation of community partnership building and engagement activities to foster recruitment efforts (Hart & Bowen, 2004; Nicholson et al., 2015). A unique organizational recruitment effort offered by the FITShop study included working with Advisory Board members to produce a culturally sensitive informational video that was shown to barbershop owners during an in-person visit. Advisory Board members helped identify key scenes, messages, and images for the video storyboard that portrayed the value and impact of promoting health in barbershops, as well as described the activities involved with study participation. A systematic review of clinical trial recruitment methods suggested that the use of videos and incentives may improve awareness and understanding and increase willingness to participate in research studies (Caldwell, Hamilton, Tan, & Craig, 2010).

An additional unique organizational recruitment strategy offered by the FITShop study is the provision of meaningful incentives to barbershop owners and their barbers, such as the opportunity to attend a series of four free professionally led business development seminars, in addition to a small financial incentive. While most barbershop-based studies discuss the provision of participant incentives, few studies have mentioned the provision of incentives for owners and barbers in the barbershop venue, unless they were focus group participants in feasibility studies (Brawner et al., 2013; Hall et al., 2016), or if they were directly involved in delivering the intervention. Thus, while barbershops have been used as study sites, little incentive has been provided to the barbershop owners and barbers who work within these shops. Of the limited studies that have provided incentives to barbershop owners, all provided monetary incentives, ranging from $25 (Brawner et al., 2013) to $75 (Hall et al., 2016) for focus group participation. Other studies, that involved the completion of client health screenings by trained barbers, provided participating owners and barbers $3 incentives per client screened, $10 for a referral call, and $50 for each returned blood pressure card from clients (Hess et al., 2007; Victor et al., 2011). By offering owners and their barbers the opportunity to participate in a series of free business development sessions, the FITShop team demonstrated an investment in the success of enrolled shops as small businesses. Black-owned barbershops have been recognized as a major business establishment in most urban cities and communities across the United States (Murphy, 1998). Following CBPR principles, which promote mutually beneficial relationships between academic and community partners (Israel et al., 2012), the business development incentives offered to partnering barbershop owners promoted the sustainability and upward mobility of Black barbershops as local small businesses.

Recruiting barbershops and other nontraditional organizations as research settings presents some challenges. For example, the list of 283 licensed barbershops in four counties obtained from the North Carolina Board of Barber Examiners included many wrong phone numbers and incomplete information. However, of the 149 barbershops our team was able to reach, only four stated that they were not interested in the study—which is an extremely low initial refusal rate. A cost-efficient approach is needed if we are to implement and sustain effective interventions and improve population health (Neta et al., 2015). If one adds the cost of mailing a letter to the 46 interested and eligible shops, staffing costs for the initial screening call and shop visits, the informational video ($11,500) and other materials, the overall cost of recruiting 17 shops (14 study shops plus three shops put on a study waiting list) was $73,450, or $4,320 per shop. Few comparisons of organization-level recruitments costs exist, but these costs compare favorably with the $5,910 recruitment costs in a previous salon study (Linnan, Harrington, Bangdiwala, & Evenson, 2012). Future studies should monitor the time and cost involved to complete organizational and participant recruitment efforts as a means of comparing settings and working toward efficiencies that will reduce costs over time (Neta et al., 2015).

Qualitative data collected from our content analysis of enrolled owners’ open-ended question responses indicate that they were highly motivated to promote health and physical activity in their shops. As organizational leaders, the barbershop owners in our study understood the importance of enrollment for the benefits of their clients, themselves, their barbershop, and the local community. Owners also specifically acknowledged the potential impact that FITShop might have on Black men’s health disparities. As seen in owners’ reasons for enrolling their barbershops, owners’ commitment and service to their customers extends beyond haircuts. These findings are consistent with the literature on minorities’ willingness to participate in research if it reflects and respects cultural and community priorities (George et al., 2014).

Owners’ relatively high self-reported rates of health care coverage, health care utilization, and adherence to physical activity and nutrition guidelines, suggest that owners who enrolled their barbershops as FITShop study sites hold positive perceptions and behaviors regarding the importance of health and physical activity. While researchers are cautioned, given this is self-report data, we are confident in the validity of the current self-reported study findings, as they mirror North Carolina BRFSS data for Black males at the time of enrollment (North Carolina BRFSS, 2011). Previous research in beauty salons and barbershops confirms the importance of owner health status in predicting successful health promotion program outcomes (Linnan et al., 2002; Solomon et al., 2004). Closely related, previous researchers have observed that barbershop owners who prioritize health have an increased likelihood of enrolling their shops as health promotion study sites. For example, in the discussion of their barbershop recruitment protocol, Baker et al. (2012) noted that one owner who had prior experience participating in community health programs was enthusiastic about their barbershop-based study on HIV/AIDS risk among young Black men, and consequently, enrolled his shop as a study site.

Strengths and Limitations

Notable study strengths include a focused organizational-level recruitment protocol that includes multiple points of interaction, including an introductory phone call to assess eligibility and interest, a mailed organizational eligibility letter, and an in-person visit to barbershops where a culturally appropriate FITShop informational video was shown. Face-to-face recruitment efforts that include endorsements from trusted representatives of the priority population has been found to establish credibility for program initiatives among stakeholders (Ochs-Balcom et al., 2015). We feel that employing these recruitment strategies facilitated our team members with building a rapport with the barbershop owners. An additional strength of our organizational recruitment design was the thoughtful selection of meaningful incentives that would personally benefit barbershop owners, such as the invitation to attend a series of four free 2-hour business development seminars led by professional experts.

Our CBPR approach of working closely with a community advisory board was also a strength of the FITShop study, especially as it pertained to the development of effective organizational recruitment strategies. The importance of working with advisory boards has been highlighted in CBPR literature (Newman et al., 2011). Additionally, several recent barbershop-based health promotion studies have discussed the importance of working with community advisory boards as a resource to strengthen their research (Hall et al., 2016; Jemmott et al., 2016). For the FITShop study, it was imperative to gain insight from Black male Advisory Board members, especially given the study’s focus on organizational recruitment and engagement with Black barbershop owners. Because Black males were our priority population, we sought to minimize any potential barriers that the academic research team composition may cause, by partnering with our Advisory Board members throughout the entirety of the FITShop study. The CBPR literature emphasizes the importance of having a research team that is composed of members who are reflective of the priority population of interest (Muhammad et al., 2015). Specifically pertaining to recruitment, Hurt (2009) advises researchers to be cognizant of the “composition of the recruitment and engagement teams, and their ability to be seen as credible and trustworthy spokespersons for the project” (p. 12). As previously noted, Black male Advisory Board members provided invaluable insight and guidance for the development of the barbershop recruitment protocol and culturally appropriate recruitment materials, including the FITShop promotional video that was shown during shop recruitment visits.

Finally, inclusion of barbershop owner structured interviews yielded important information about characteristics of barbershop owners who are likely to enroll their shops as health promotion study sites, as well as their reasons for deciding to enroll their shop as a FITShop study site. Collectively, our study strengths serve as potential points of emphasis for future studies that are interested in organizational recruitment of barbershops.

Despite having strengths, the current study also had several limitations. These limitations include a lack of generalizability to all Black barbershops due to the nonrandomized nature of the recruitment process and our restriction of recruiting within four counties and nonfranchise locations. We also had a relatively small sample size for our structured interviews, which limited us to only being able to provide information from 14 barbershop owners. Additionally, while we gathered important information about the characteristics of owners who were willing to enroll their barbershops in the study, we lack data from owners that refused to enroll in the study, which limited our ability to generalize these findings beyond this sample.

Conclusions and Implications for Researchers and Practitioners

Our article contributes new knowledge about how to strategically and effectively recruit barbershops as sites for health promotion intervention trials for Black men. Given the health disparities suffered by Black men and their low participation in clinical and community trials, it is imperative that we identify, learn about, and partner with trusted community organizations that can serve as settings for Black men to enroll and participate in studies that address critical health issues. Owners’ reasons for joining the FITShop study, especially as it pertains to their perceived shop and community benefits, may serve as points of emphasis for future barbershop organizational recruitment efforts and interactions with owners and may also encourage support from barbers, given the importance of gaining buy-in from organizational leaders. Additionally, our CBPR-guided recruitment and enrollment strategies offer insight for building strong collaborative partnerships with barbershop owners, as organizational leaders, to address health disparities among Black men. Providing innovative incentives such as business development workshops can demonstrate a solid commitment to the sustainability of barbershops as essential organizations in the Black community.

When seeking to conduct barbershop-based work, future researchers should consider all available resources to assist with developing a strong organizational recruitment plan. Each state across the United States has a Board of Cosmetology and Barbering Examiners, whose purpose is to govern and document individual licensing and business operation of barbershops and salons. Similar to North Carolina, other State Boards of Barbering Examiners may serve as a helpful resource for obtaining a statewide list of barbershops. Additionally, as an important component of CBPR, the development of a representative community advisory board is an essential recommended resource for researchers seeking to recruit barbershops for collaborative health promotion research. We believe that the detailed information provided about the role of the community advisory board and development of the culturally appropriate FITShop organizational recruitment strategies prove useful to those interested in recruiting Black barbershops as sites for future research and/or practice-based interventions and reaching Black men.

Authors’ Note:

Special thanks to Sadiya Muqueeth, Seronda Robinson, Carolyn Naseer, Ashley Caldwell, and Ashley Lawrence for their help with shop recruitment. We also thank members of the NC Beauty and Barbershop Advisory Board who have guided all aspects of the study and all participating shop owners and barbers. This study was funded by the National Cancer Institute (Grant No. 5U54CA156735-03).

REFERENCES

- Apantaku-Onayemi F. (2013). Stay beautiful–stay alive: Assessing the receptivity of African American beauty salon owners to the integration of breast cancer intervention programs into salon operations (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.olivet.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1049&context=edd_diss. (Paper 50) [Google Scholar]

- Baker JL, Brawner B, Cederbaum JA, White S, Davis ZM, Brawner W, & Jemmott LS (2012). Barbershops as venues to assess and intervene in HIV/STI risk among young, heterosexual African American men. American Journal of Men’s Health, 6, 368–382. doi: 10.1177/1557988312437239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blumenthal DS, Sung J, Coates R, Williams J, & Liff J. (1995). Recruitment and retention of subjects for a longitudinal cancer prevention study in an inner-city black community. Health Services Research, 30(1 Pt 2), 197–205. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brawner BM, Baker JL, Stewart J, Davis ZM, Cederbaum J, & Jemmott LS (2013). “The black man’s country club”: Assessing the feasibility of an HIV risk-reduction program for young heterosexual African American men in barbershops. Family & Community Health, 36, 109–118. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e318282b2b5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Browne MC (2007). “Full service”: Talking about fighting prostate cancer—in the barber shop! Heath Education & Behavior, 34, 557–561. [Google Scholar]

- Byrd GS, Edwards CL, Kelkar VA, Phillips RG, Byrd JR, Pim-Pong DS, . . . Pericak-Vance M. (2011). Recruiting intergenerational African American males for biomedical research studies: A major research challenge. Journal of the National Medical Association, 103, 480–487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell PH, Hamilton S, Tan A, & Craig JC (2010). Strategies for increasing recruitment to randomised controlled trials: Systematic review. PLoS Medicine, 7(11), e1000368. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cowart L, Brown B, & Biro D. (2004). Educating African American men about prostate cancer: The barbershop program. American Journal of Health Studies, 19, 205–213. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz VA, Mainous A, McCall AA, & Geesey ME (2008). Factors affecting research participation in African American college students. Family Medicine, 40, 46–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FITShopUNC. (Producer). (2012). FITShop study [Video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3brsxQpbMGI

- Ford DS, & Goode CR (1994). African American college students’ health behaviors and perceptions of related health issues. Journal of American College Health, 42, 206–210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frencher SK Jr., Sharma AK, Teklehaimanot S, Wadzani D, Ike IE, Hart A, & Norris K. (2016). PEP talk: Prostate education program, “Cutting through the uncertainty of prostate cancer for Black men using decision support instruments in barbershops.” Journal of Cancer Education, 31, 506–513. doi: 10.1007/s13187-015-0871-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- George S, Duran N, & Norris K. (2014). A systematic review of barriers and facilitators to minority research participation among African Americans, Latinos, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders. American Journal of Public Health, 104, e16–e31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall MB, Eden TM, Bess JJ, Landrine H, Corral I, Guidry JJ., & Efird JT. (2016). Rural shop-based health program planning: A formative research approach among owners. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1007/s40615-016-0252-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart A, Underwood SM, Smith WR, Bowen DJ, Rivers BM, Jones RA, & Parker D. (2008). Recruiting African-American barbershops for prostate cancer education. Journal of the National Medical Association, 100, 1012–1020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart A Jr., & Bowen DJ (2004). The feasibility of partnering with African-American barbershops to provide prostate cancer education. Ethnicity & Disease, 14, 269–273. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess PL, Reingold JS, Jones J, Fellman MA, Knowles P, Ravenell JE, . . . Victor RG. (2007). Barbershops as hypertension detection, referral, and follow-up centers for black men. Hypertension, 49, 1040–1046. doi: 10.1161/hypertensionaha.106.080432 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hood S, Linnan L, Jolly D, Muqueeth S, Hall MB, Dixon C, & Robinson S. (2015). Using the PRECEDE Planning approach to develop a physical activity intervention for African American men who visit barbershops: Results from the FITShop study. American Journal of Men’s Health, 9, 262–273. doi: 10.1177/1557988314539501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurt T. (2009). Connecting with African American families: Challenges and possibilities. The Family Psychologist, 25, 11–13. [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Eng E, Shulz AJ, & Parker EA (Eds.). (2012). Methods for community-based participatory research for health (2nd ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass. [Google Scholar]

- Jemmott LS, Jemmott JB, Lanier Y, Thompson C, & Baker JL (2016). Development of a barbershop-based HIV/STI risk reduction intervention for young heterosexual African American men. Health Promotion Practice. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1177/1524839916662601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson RN, Speck PM, Bowdre TL, & Porter K. (2015). Assessment of the feasibility of barber-led sexual education for African-American adolescent males. Journal of the National Black Nurses Association, 26, 67–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones RA, Steeves R, & Williams I. (2009). How African American men decide whether or not to get prostate cancer screening. Cancer Nursing, 32, 166–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnan LA, D’Angelo H, & Harrington CB (2014). A literature synthesis of health promotion research in salons and barbershops. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 47, 77–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnan LA, Emmons K, & Abrams D. (2002). Beauty and the beast: Results of the Rhode Island smokefree shop initiative. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 27–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnan LA, Harrington C, Bangdiwala K, & Evenson K. (2012). Comparing recruitment methods to enrolling organizations into a community-based intervention trial: Results from the NC BEAUTY and health project. Journal of Clinical Trials, 2, 119. [Google Scholar]

- Linnan LA, Reiter P, Duffy C, Hales D, Ward D, & Viera A. (2011). Assessing and promoting physical activity in African American barbershops: Results of the FITStop pilot study. American Journal of Men’s Health, 5, 38–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Linnan LA, Thomas S, D’Angelo H, & Ferguson Y. (2012). African American barbershops and beauty salons: An innovative approach to reducing health disparities through community building and health education. In Minkler M. (Ed.), Community organizing and community building for health and welfare (3rd ed., pp. 229–245). New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Luque JS, Rivers BM, Gwede CK, Kambon M, Green BL, & Meade CD (2011). Barbershop communications on prostate cancer screening using barber health advisers. American Journal of Men’s Health, 5, 129–139. doi: 10.1177/1557988310365167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque JS, Rivers BM, Kambon M, Brookins R, Green BL, & Meade CD (2010). Barbers against prostate cancer: A feasibility study for training barbers to deliver prostate cancer education in an urban African American community. Journal of Cancer Education, 25, 96–100. doi: 10.1007/s13187-009-0021-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque JS, Ross L, & Gwede C. (2014). Qualitative systematic review of barber-administered health education, promotion, screening and outreach programs in African-American communities. Journal of Community Health, 39, 181–190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luque JS, Roy S, Tarasenko YN, Ross L, Johnson J, & Gwede CK (2015). Feasibility study of engaging barbershops for prostate cancer education in rural African-American communities. Journal of Cancer Education, 30, 623–628. doi: 10.1007/s13187-014-0739-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnus M. (2004). Barbershop nutrition education. Journal of Nutrition Education and Behavior, 36, 45–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore N, Wright M, Gipson J, Jordan G, Harsh M, Reed D, . . . Murphy A. (2016). A survey of African American men in Chicago barbershops: Implications for the effectiveness of the barbershop model in the health promotion of African American men. Journal of Community Health, 41, 772–779. doi: 10.1007/s10900-016-0152-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muhammad M, Wallerstein N, Sussman AL, Avila M, Belone L, & Duran B. (2015). Reflections on researcher identity and power: The impact of positionality on community based participatory research (CBPR) processes and outcomes. Critical Sociology, 41, 1045–1063. doi: 10.1177/0896920513516025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy M. (1998). Barbershop talk: The other side of Black men. Merrifield, VA: Murphy Communications. [Google Scholar]

- Nathan MB (2013). Assessing the feasibility of an HIV risk-reduction program for young heterosexual African American men in barbershops. Family Community Health, 36, 284. doi: 10.1097/FCH.0b013e31829e9b57 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Neta G, Glasgow RE, Carpenter CR, Grimshaw JM, Rabin BA, Fernandez ME, & Brownson RC (2015). A framework for enhancing the value of research for dissemination and implementation. American Journal of Public Health, 105, 49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newman SD, Andrews JO, Magwood GS, Jenkins C, Cox MJ, & Williamson DC (2011). Community advisory boards in community-based participatory research: A synthesis of best processes. Preventing Chronic Disease, 8(3), A70. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newton RL Jr., Griffith DM, Kearney WB, & Bennett GG (2014). A systematic review of weight loss, physical activity and dietary interventions involving African American men. Obesity Review, 15(Suppl. 4), 93–106. doi: 10.1111/obr.12209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nicholson LM, Schwirian PM, & Groner JA (2015). Recruitment and retention strategies in clinical studies with low-income and minority populations: Progress from 2004–2014. Contemporary Clinical Trials, 45, 34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- North Carolina BRFSS. (2011). Retrieved from http://www.schs.state.nc.us/schs/brfss/2011/

- Ochs-Balcom HM, Jandorf L, Wang Y, Johnson D, Meadows Ray V, Willis MJ, & Erwin DO (2015). “It takes a village”: Multilevel approaches to recruit African Americans and their families for genetic research. Journal of Community Genetics, 6, 39–45. doi: 10.1007/s12687-014-0199-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pepe MV (1989). Minority barbers screen customers for hypertension. Health Education, 20, 10–12. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rader F, Elashoff RM, Niknezhad S, & Victor RG (2013). Differential treatment of hypertension by primary care providers and hypertension specialists in a barber-based intervention trial to control hypertension in Black men. American Journal of Cardiology, 112, 1421–1426. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Releford BJ, Frencher SK Jr., & Yancey AK (2010). Health promotion in barbershops: Balancing outreach and research in African American communities. Ethnicity & Disease, 20, 185–188. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renert H, Russell-Mayhew S, & Arthur N. (2013). Recruiting ethnically diverse participants into qualitative health research: Lessons learned. Qualitative Report, 18, 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Roy S. (2016). Assessing the feasibility of the employer as a health advisor for type 2 diabetes prevention (Electronic theses & dissertations). Georgia Southern University, Statesboro. Retrieved from http://digitalcommons.georgiasouthern.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2503&context=etd. (Paper 1424) [Google Scholar]

- Saldana J. (2013). The coding manual for qualitative researchers (2nd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Solomon FM, Linnan LA, Wasilewski Y, Lee AM, Katz ML, & Yang J. (2004). Observational study in ten beauty salons: Results informing development of the North Carolina BEAUTY and health project. Health Education & Behavior, 31, 790–807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spence CT, & Oltmanns TF (2011). Recruitment of African American men: Overcoming challenges for an epidemiological study of personality and health. Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology, 17, 377–380. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Victor RG, Ravenell JE, Freeman A, Leonard D, Bhat DG, Shafiq M, . . . Haley RW. (2011). Effectiveness of a barber-based intervention for improving hypertension control in black men: The BARBER-1 study: A cluster randomized trial. Archives of Internal Medicine, 171, 342–350. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.390 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weinrich SP, Greiner E, Reis-Starr C, Yoon S, & Weinrich M. (1998). Predictors of participation in prostate cancer screening at worksites. Journal of Community Health Nursing, 15, 113–129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson TE, Fraser-White M, Williams KM, Pinto A, Agbetor F, Camilien B, . . . Joseph MA. (2014). Barbershop talk with brothers: Using community-based participatory research to develop and pilot test a program to reduce HIV risk among Black heterosexual men. AIDS Education and Prevention, 26, 383–397. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2014.26.5.383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yancy CW (2011). A bald fade and a BP check: Comment on “Effectiveness of a barbershop-based intervention for improving hypertension control in black men.” Archives of Internal Medicine, 171, 350–352. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]