Abstract

CCR5 is an essential coreceptor for the cellular entry of R5 strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1). CCR5-893(−) is a single-nucleotide deletion mutation which is observed exclusively in Asians (M. A. Ansari-Lari, et al., Nat. Genet. 16:221–222, 1997). This mutant gene produces a CCR5 which lacks the entire C-terminal cytoplasmic tail. To assess the effect of CCR5-893(−) on HIV-1 infection, we generated a recombinant Sendai virus expressing the mutant CCR5 and compared its HIV-1 coreceptor activity with that of wild-type CCR5. Although the mutant CCR5 has intact extracellular domains, its coreceptor activity was much less than that of wild-type CCR5. Flow cytometric analyses and confocal microscopic observation of cells expressing the mutant CCR5 revealed that surface CCR5 levels were greatly reduced in these cells, while cytoplasmic CCR5 levels of the mutant CCR5 were comparable to that of the wild type. Peripheral blood CD4+ T cells obtained from individuals heterozygous for this allele expressed very low levels of CCR5. These data suggest that the CCR5-893(−) mutation affects intracellular transport of CCR5 and raise the possibility that this mutation also affects HIV-1 transmission and disease progression.

CCR5 is an essential coreceptor for the cellular entry of R5 (macrophagetropic, non-syncytium-inducing) strains of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) (1, 8, 15, 19–21), which predominate in the early stages of infection (59). During the course of infection, variants called X4 (T-cell-line tropic, syncytium-inducing) strains emerge (5, 8, 14, 17, 54), which use CXCR4 as a coreceptor (22). In vitro replication of R5 strains can be blocked by ligands of CCR5, macrophage inflammatory peptides 1α and 1β, and RANTES (regulated on activation normal T-cell expressed and secreted) (4, 16). Recently, monocyte chemoattractant protein 2 was found to be a natural ligand of CCR5 (9, 23, 49). On the other hand, replication of X4 strains can be blocked by the CXCR4 ligands stromal cell derived factor 1α and 1β (SDF-1α and SDF-1β) (10, 42).

Mutations in HIV-1 coreceptors and their natural ligand genes have been shown to modify HIV-1 transmission and disease progression. Caucasians homozygous for a 32-nucleotide deletion in the CCR5 coding region (CCR5Δ32) are resistant to HIV-1 infection (32, 50), while heterozygosity delays disease progression (18, 38). A single valine-to-isoleucine change in the first transmembrane segment of CCR2 (CCR2-64I), a minor coreceptor for dualtropic R5X4 strains (15, 20), has a significant impact on disease progression but not on HIV-1 transmission (30, 53). Homozygosity of a single G-to-A mutation in the 3′ noncoding region of the SDF-1 gene also showed a disease retarding effect (56), although later studies could not confirm this effect (39, 55). A CCR5 promoter variant was shown to be associated with accelerated progression in HIV-1 diseases (35, 37). We recently demonstrated that a single A-to-G mutation in the promoter region of RANTES was associated with delayed disease progression in HIV-1-infected individuals in Japan (31).

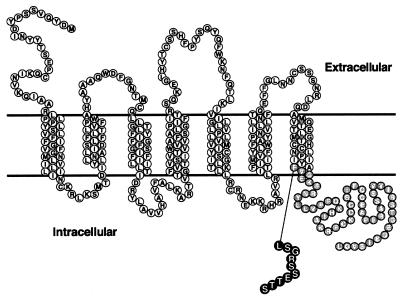

In addition to the relatively abundant HIV-1 disease-modifying alleles described above, several less frequent polymorphisms have been found in the coding region of CCR5 (3, 11, 27, 34, 47). Among them, CCR5-893(−) is a single-nucleotide deletion which is observed exclusively in Asians (3). This deletion caused a frameshift at codon 299 and resulted in premature termination of translation (Fig. 1). As a result, the CCR5-893(−) gene product lacked 51 amino acid residues in the C-terminal cytoplasmic tail and 3 residues in the last transmembrane segment, and it gained 10 amino acid residues encoded in the −1 open reading frame in its C terminus. The CCR5-893(−) gene product is thus composed of 308 amino acids.

FIG. 1.

Structure of the CCR5-893(−) gene product. Outlined letters in gray circles denote amino acid residues which are not present in the CCR5-893(−) gene product; those in black circles denote amino acid residues generated by the frameshift.

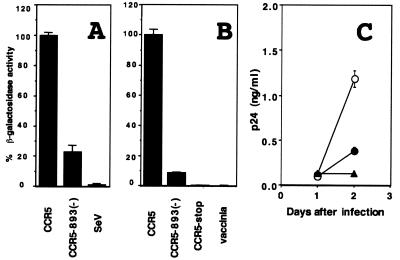

To assess the effect of CCR5-893(−) on HIV-1 infection, we used a recombinant Sendai virus (SeV) vector to express the wild-type and mutant CCR5 and examined their ability to support CD4-dependent cell fusion mediated by an HIV-1 envelope protein of the R5 strain SF162. Recombinant SeVs were generated as described previously (26, 28, 29), and HIV-1 coreceptor activity was examined by a recombinant vaccinia virus-based gene activation assay using a β-galactosidase gene as a reporter (40, 41). Mouse L cells lacking endogenous CCR5 expression were used for this experiment. Since none of the extracellular domains of CCR5 were affected by this deletion, we initially anticipated that this deletion had no effect on HIV-1 coreceptor activity. On the contrary, the CCR5-893(−) product showed a greatly reduced ability to support R5 envelope-mediated cell fusion compared with wild-type CCR5 (Fig. 2A). A similar result was obtained when we used a vaccinia virus vector to express CCR5 (Fig. 2B) (33, 52). Northern blot analyses confirmed the presence of comparable amounts of CCR5 mRNA in cells infected with SeV expressing wild-type CCR5 and in those infected with SeV expressing CCR5-893(−) (data not shown). Furthermore, CD4+ MT4 cells infected with SeV expressing wild-type CCR5 supported replication of SF162 five times better than those infected with SeV expressing CCR5-893(−) (Fig. 2C). These data clearly indicated that the CCR5-893(−) product had a reduced coreceptor activity for HIV-1 entry.

FIG. 2.

HIV-1 coreceptor activity of wild-type CCR5 and CCR5-893(−). SeV (A) or vaccinia virus (B) vector was used to express wild-type CCR5 and CCR5-893(−), and HIV-1 coreceptor activity of each CCR5 construct was measured as described in the text. Vaccinia virus was also used to express the CCR5-stop product. SeV and vaccinia denote the parental strains of SeV and vaccinia virus, respectively. (C) MT4 cells were infected with SeV expressing wild-type CCR5 (open circles), CCR5-893(−) (closed circles), and the parental Z strain of SeV (triangles) at a multiplicity of infection of 10 PFU per cell. Six hours after infection, cells were inoculated with 25 ng of p24 of HIV-1 strain SF162. Culture supernatants were periodically assayed for levels of p24.

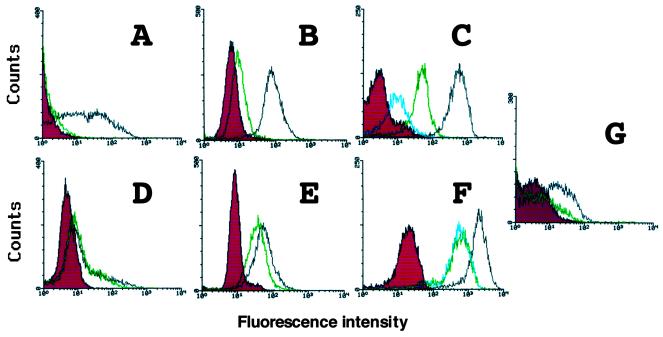

We then analyzed levels of cell surface CCR5 by flow cytometry. Jurkat and L cells were used in this experiment. Nine hours after infection of SeVs expressing the wild-type and mutant CCR5, cells were stained with T227, a rat monoclonal immunoglobulin G1 (IgG1) antibody directed against the N-terminal extracellular domain of CCR5 (Y. Tanaka et al., unpublished data), followed by fluorescein-5-isothiocyanate (FITC)-labeled anti-rat IgG. Stained cells were fixed in 1% formaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and analyzed by FACScan (Becton Dickinson, San Jose, Calif.). As shown in Fig. 3, the CCR5-893(−) product was poorly detected on the surface of all the cell lines examined, whereas wild-type CCR5 was readily detected on the cell surface (Fig. 3A and B). When cells were permeabilized with 0.05% saponin and 0.2% bovine serum albumin in PBS before staining, strong staining was observed in cells expressing the CCR5-893(−) product (Fig. 3D and E). Intracellular fluorescence intensity of the CCR5-893(−) product was comparable to that of the wild type. These data suggested that the mutant CCR5 was synthesized as efficiently as the wild type, but its surface trafficking was greatly impaired by the mutation. A similar result was obtained when we used monocytic U937 cells (data not shown).

FIG. 3.

Surface and intracellular expression of CCR5. Jurkat cells (A and D) and L cells (B and E) were infected with SeV expressing the wild-type CCR5 (black) or CCR5-893(−) gene product (green). CV1 cells (C and F) were infected with vaccinia virus expressing the wild-type CCR5 (black), CCR5-893(−) (green), or CCR5-stop (blue) gene product. Nine hours after infection with SeV or 12 h after infection with vaccinia virus, cells were stained with anti-CCR5 rat monoclonal antibody T227 followed by FITC-labeled anti-rat IgG and analyzed by flow cytometry. Before staining, cells were permeabilized (D to F) or not (A to C) with saponin. Cells infected with the parental Z strain of SeV (A, B, D, and E) and the parental WR strain of vaccinia virus (C and F) served as a control (red). (G) Jurkat cells were coinfected with SeV expressing the wild-type CCR5 and CCR5-893(−) gene products (green) or coinfected with SeV expressing wild-type CCR5 and the parental Z strain of Sendai virus (black). Six hours after infection, cells were stained with anti-CCR5 rat monoclonal antibody followed by FITC-labeled anti-rat IgG without permeabilization. Cells infected with the parental Z strain of SeV served as a control (red).

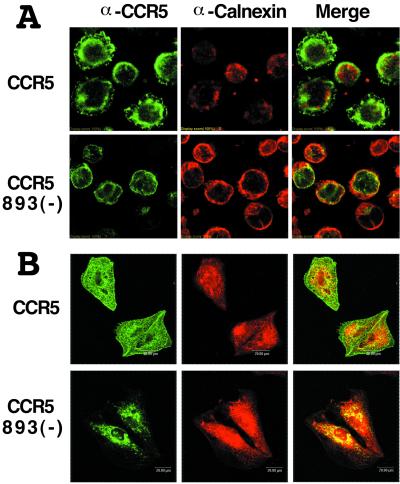

To determine the subcellular localization of the CCR5-893(−) product, we used immunofluorescence confocal microscopy. Jurkat and HeLa cells infected with SeV expressing wild-type CCR5 or CCR5-893(−) were fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde in PBS, permeabilized with 0.05% saponin and 0.2% bovine serum albumin in PBS, and incubated with rat monoclonal antibody T227 directed against human CCR5 and rabbit polyclonal antibodies directed against calnexin (Stressgen). Bound antibodies were then detected with FITC-conjugated goat antibody directed against rat IgG (American Qualex Antibodies, San Clemente, Calif.) or Cy5-conjugated goat antibody directed against rabbit IgG (Amersham-Pharmacia Biotech). Indirect immunofluorescence was visualized with a Fluoview FV300 laser confocal microscope system (Olympus, Tokyo, Japan). As shown in Fig. 4, fluorescent signals of CCR5 were mainly observed on the cell surface in cells expressing wild-type CCR5. Calnexin, an endoplasmic reticulum (ER) chaperone that assists in the folding of proteins in the ER, was observed in the perinuclear regions of the cells and showed only a partial colocalization with CCR5 (Fig. 4). In contrast, distribution of the CCR5-893(−) product was limited to the perinuclear regions, and almost all CCR5-specific signals were surrounded by calnexin-specific signals (Fig. 4). These data indicated a clear colocalization of the CCR5-893(−) product and calnexin in both cell types and suggested that the CCR5-893(−) product was retained in ER. Similar results were obtained when we used U937 cells or 2D7, a mouse monoclonal antibody against the second extracellular loop of CCR5 (data not shown).

FIG. 4.

Subcellular distribution of the wild-type CCR5 and CCR5-893(−) gene products in Jurkat (A) and HeLa (B) cells. SeV vector was used to express the wild-type CCR5 (CCR5) and CCR5-893(−) gene products [CCR5 893(−)]. Cells were permeabilized with saponin, double stained with rat anti-CCR5 monoclonal antibody (α-CCR5; green) and rabbit anticalnexin antibody (α-Calnexin; red) followed by FITC-labeled anti-rat IgG and Cy5-labeled anti-rabbit IgG, and analyzed by a confocal laser microscope. Colocalization of CCR5 and calnexin is indicated in yellow in the merged images (Merge).

To investigate whether the additional 10 amino acid residues generated by the frameshift are responsible for the inefficient surface trafficking of the CCR5-893(−) product, we introduced a stop codon at position 299 of CCR5 to remove these 10 amino acid residues from the mutant CCR5. A recombinant vaccinia virus was used to express this artificial mutant CCR5, designated CCR5-stop. L cells infected with the recombinant vaccinia virus expressing CCR5-stop did not support CD4-dependent R5 envelope-mediated membrane fusion (Fig. 2B). Surface expression of CCR5-stop in CV-1 cells was more severely impaired than that of the CCR5-893(−) product (Fig. 3C), although intracellular staining of CCR5-stop was comparable to that of the CCR5-893(−) product (Fig. 3F). These data indicated that lack of the entire cytoplasmic tail rather than the addition of 10 aberrant amino acid residues was responsible for inefficient surface trafficking of the mutant CCR5. Previously, Gosling et al. reported that a deletion after amino acid 308 of CCR5 did not abolish its HIV-1 coreceptor activity (24). Similarly, Alkhatib et al. demonstrated that truncation after amino acid 307 did not alter surface expression, chemokine binding, and HIV-1 coreceptor activity of CCR5 (2). Therefore, the eight amino acid residues from positions 299 to 306 seem to be important for efficient surface trafficking of CCR5.

CCR5Δ32 was reported to affect expression of wild-type CCR5 (7). To determine whether CCR5-893(−) also has a dominant negative effect on wild-type CCR5 expression, we simultaneously inoculated Jurkat cells with SeV expressing wild-type CCR5 and SeV expressing CCR5-893(−). Six hours after infection, surface expression of CCR5 was examined by flow cytometry. As shown in Fig. 3G, coinfection with SeV expressing CCR5-893(−) severely reduced the levels of CCR5 expression on the cell surface compared to coinfection with the parental Z strain of SeV. This finding indicated that CCR5-893(−) dominantly affects wild-type CCR5 expression as the CCR5Δ32 does.

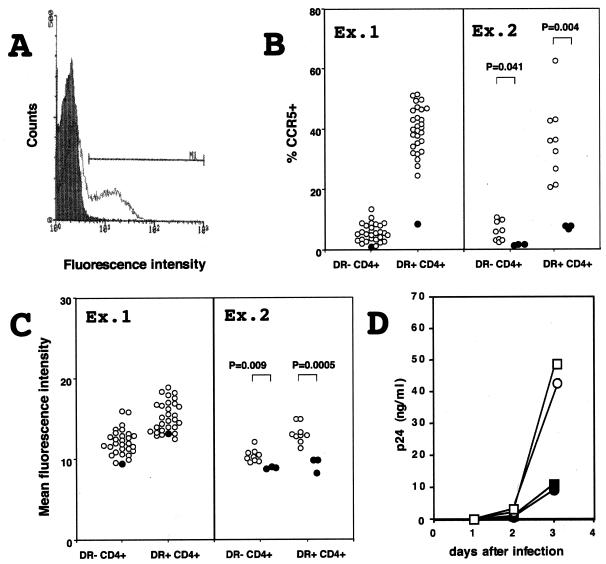

To determine whether individuals carrying CCR5-893(−) exhibit reduced cell surface expression of CCR5, we analyzed levels of CCR5 on the surface of primary peripheral blood CD4+ cells. CD4+ cells were positively selected from peripheral blood mononuclear cells by using MACS CD4 MicroBeads (Miltenyi Biotec, Nordrhein-Westfalen, Germany) and stained with T227 rat monoclonal antibody directed against CCR5 followed by FITC-conjugated goat antibody directed against rat IgG (American Qualex Antibodies) and a peridinin chlorophyll protein (PerCP)-conjugated mouse monoclonal antibody directed against HLA-DR (Becton Dickinson). Stained cells were fixed in 1% formaldehyde in PBS and analyzed by FACScan (Becton Dickinson) (Fig. 5A). In the first set of experiments (Ex. 1 in Fig. 5B and C), we analyzed one heterozygote for CCR5-893(−) and 30 nonmutant individuals. We then analyzed three heterozygotes for CCR5-893(−) and nine nonmutant individuals in experiment 2 in Fig. 5B and C. CD4+ cells were further divided into HLA-DR+ cells and HLA-DR− cells to normalize the activation status of each individual, which is known to affect the levels of CCR5 expression (58). The proportion of HLA-DR+ CD4+ cells varied among individuals, ranging from 3 to 19% of total CD4+ cells. As reported previously (48), more HLA-DR+ CD4+ cells than HLA-DR− CD4+ cells express CCR5. Nevertheless, both HLA-DR+ and HLA-DR− CD4+ cells from individuals heterozygous for CCR5-893(−) expressed significantly lower levels of CCR5 than those from nonmutant individuals (Fig. 5B and C). These data suggested that CCR5-893(−) also reduced CCR5 expression in cells that can be actual targets for HIV-1 infection. Furthermore, CD8+ cells from the heterozygote for CCR5-893(−) also showed reduced levels of CCR5 expression (data not shown).

FIG. 5.

Expression of CCR5 on peripheral blood CD4+ cells. (A) Typical staining of CCR5 on CD4+ T cells. CD4+ cells stained only with the FITC-conjugated goat antibody directed against rat IgG served as a control (shaded). Cells shown by a bar are regarded as CCR5+. (B) Proportion of CCR5+ cells in CD4+ HLA-DR+ cells and in CD4+ HLA-DR− cells. Ex. 1 and Ex. 2 denote the first and second sets of experiments, respectively. Closed circles denote cells obtained from heterozygotes for CCR5-893(−), and open circles denote cells from individuals who do not possess CCR5-893(−). Statistical significance of difference between heterozygotes for CCR5-893(−) and individuals who do not possess CCR5-893(−) are shown only in the second set of experiments. (C) Mean fluorescence intensity of CCR5 in CCR5+ cells. For details, see the legend to panel B. (D) Infectability of donor CD4+ cells. CD4+ cells obtained from two heterozygotes (open circles and squares) and two nonmutant individuals (closed circles and squares) were stimulated with phytohemagglutinin and inoculated with HIV-1 strain SF162. Culture supernatants of infected cells were periodically assayed for levels of p24 core antigen.

Above finding prompted us to investigate whether CD4+ cells from heterozygotes for CCR5-893(−) show reduced sensitivity to infection with HIV-1 R5 strains. For this, 106 CD4+ cells obtained from two heterozygotes and two nonmutant individuals were stimulated with phytohemagglutinin for 2 days and then inoculated with 25 ng of p24 of HIV-1 strain SF162. Culture supernatants of infected cells were periodically assayed for levels of p24 core antigen (RETRO-TEK, Buffalo, N.Y.). As shown in Fig. 5D, HIV-1 strain SF162 grew to significantly lower titers in cells from two heterozygotes than in those from two nonmutant individuals. This result suggested that CD4+ cells from individuals heterozygous for CCR5-893(−) had reduced sensitivity to infection with HIV-1 R5 strains.

To determine the frequency of CCR5-893(−) in non-HIV-1-infected and HIV-1-infected individuals in Japan, we analyzed CCR5 genes of 156 non-HIV-1-infected and 207 HIV-1-infected individuals. DNA was extracted from peripheral blood mononuclear cells by a method previously described (31). Informed consent was obtained from all subjects. DNA fragments corresponding to a 1,194-bp region spanning the entire open reading frame of CCR5 were PCR amplified using primers CKR5a+ (5′-CAGTTTGCATTCATGGAGGG-3′) and CKR5a− (5′-CTAAGCCATGTGCACAACTC-3′). PCR was performed in a 50-μl reaction mixture containing 1 μg of DNA by 40 cycles of 94°C for 30 s, 58°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 1 min. Amplified DNA fragments were purified and sequenced using primer CKR5c+ (5′-CTGTGTTTGCGTCTCTCC-3′). Sequencing reactions were performed by the dideoxy-chain termination method using an ABI Prism 377 (Applied Biosystems) automated DNA sequencer. We found three heterozygotes among non-HIV-1-infected and two among HIV-1-infected individuals. The calculated allele frequencies were approximately 1% in non-HIV-1-infected and 0.5% in HIV-1-infected individuals, showing a tendency toward reduced frequency in HIV-1-infected individuals, although this difference did not reach statistical significance. Since both non-HIV-1-infected and HIV-1-infected individuals carry CCR5-893(−), heterozygosity for this allele does not confer complete resistance to initial HIV-1 transmission. Although homozygosity of CCR5-893(−) is highly likely to confer at least partial resistance to initial HIV-1 transmission, the frequency of this allele appeared to be too low for evaluation of the epidemiological consequence of this allele in Japan. The clinical effect of this allele may be similar to that of CCR5Δ32, since heterozygosity for CCR5Δ32 also failed to protect from HIV-1 transmission, while this genotype was associated with delayed disease progression (18, 38). We are currently analyzing samples from other Asian ethnic groups including Chinese and Thai to determine whether CCR5-893(−) is more prevalent in these populations.

With respect to cytoplasmic retention of chemokine receptors, two precedents have been reported. The chemokine receptor CCR2, which shows more than 75% amino acid sequence homology with CCR5, arises in two isoforms, CCR2A and CCR2B, by differential splicing from a single gene. They differ only in their carboxyl-terminal cytoplasmic tails (12). The amino acid sequence of the CCR2B cytoplasmic tail showed 76% identity with that of CCR5, whereas the corresponding region of CCR2A showed little homology with CCR5. A recent study by Wong et al. showed that CCR2A was predominantly detected in the cytoplasm of transfected cells, whereas CCR2B was efficiently trafficked to the cell surface (57). Truncation analyses of CCR2A further suggested the presence of a cytoplasmic retention signal in the carboxyl tail. In the case of CCR5, however, our truncation analysis suggested that the absence of the entire cytoplasmic tail rather than the addition of aberrant amino acid residues generated by the frameshift was responsible for the poor trafficking of the mutant CCR5. Therefore, the molecular mechanism of cytoplasmic retention of CCR5-893(−) may be different from that of CCR2A. Further studies, including the identification of factors interacting with the cytoplasmic tails of CCR2A, CCR2B, and CCR5, would be necessary to define the precise mechanisms responsible for cytoplasmic retention of these chemokine receptors. Also, it would be interesting to analyze the interaction between the CCR5-893(−) product and ER chaperones, since our confocal microscopic observation of cells expressing the mutant CCR5 suggested that the mutant protein was retained in ER.

Another example of cytoplasmic retention of the chemokine receptor is US28, encoded by a cytomegalovirus. This chemokine receptor also showed HIV-1 coreceptor activity (45) and was reported to be retained in the cytoplasm of Cf2Th cells but not COS-1, U87, or HeLa cells (43). Similarly, our data showed that surface expression of CCR5-893(−) was more severely impaired in Jurkat (Fig. 3A) and U937 (data not shown) cells than in epithelial CV1 cells (Fig. 3C). It is possible that factors affecting surface trafficking of these chemokine receptors distribute differently in different cell types and that the molecular mechanism controlling cytoplasmic retention of US28 may be identical or similar to that of CCR5-893(−).

CCR5Δ32 was mainly observed in Caucasians (18, 32, 38, 53), whereas CCR5-893(−) was exclusively observed in Asians (3). Furthermore, CCR5Δ24, another nonfunctional allele of CCR5, was also observed in sooty mangabey and red-capped mangabey monkeys (13, 44). Distribution of multiple nonfunctional alleles of CCR5 in various human and primate populations suggested the presence of a certain selective pressure favoring those nonfunctional alleles during evolution of humans and lower primates. It is unlikely that HIV-1 infection itself could be the selective pressure, since the HIV-1 epidemic is a recent event. CCR5 has been shown to be involved in several inflammatory diseases (6, 46), and CCR5Δ32 was associated with a reduced risk of severe symptoms in patients with multiple sclerosis and asthma (25, 51). Therefore, it is possible that impaired function of CCR5 might be advantageous for survival of individuals with autoimmune or inflammatory diseases. Alternatively, nonfunctional alleles of CCR5 might have been selected for by variola virus epidemics, since it was recently reported that poxvirus infection was facilitated by CCR5 (36).

Acknowledgments

The first two authors contributed equally to this work.

We thank all of the blood donors described in this study, David Chao and Jun-ichi Sakuragi for critical discussions, and Akio Nomoto and Shusuke Kuge for guiding the confocal microscopic observations. pG1T7β-gal was kindly supplied by E. Berger.

This work was supported by grants from the Ministry of Education, Science, Sports and Culture, the Ministry of Health and Welfare, and the Organization for Pharmaceutical Safety and Research (OPSR), Japan.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alkhatib G, Combadiere C, Broder C C, Feng Y, Kennedy P E, Murphy P M, Berger E A. CC-CKR5: a RANTES, MIP-1α, MIP-1β receptor as a fusion cofactors for macrophage-tropic HIV-1. Science. 1996;272:1955–1958. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5270.1955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alkhatib G, Locati M, Kennedy P E, Murphy P M, Berger E A. HIV-1 coreceptor activity of CCR5 and its inhibition by chemokines: independence from G protein signaling and importance of coreceptor downmodulation. Virology. 1997;234:340–348. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8673. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ansari-Lari M A, Liu X-M, Metzker M L, Rut A R, Gibbs R A. The extent of genetic variation in the CCR5 gene. Nat Genet. 1997;16:221–222. doi: 10.1038/ng0797-221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Virelizier J L, Rousset D, Clark-Lewis I, Loetscher P, Moser B, Baggiolini M. HIV blocked by chemokine antagonist. Nature (London) 1996;383:400. doi: 10.1038/383400a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Asjo B, Albert J, Karlsson A, Morfeldt-Manson L, Biberfeld G, Lidman K, Fenyo E M. Replicative properties of human immunodeficiency viruses from patients with varying severity of HIV infection. Lancet. 1986;ii:660–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Balashov K E, Rottman J B, Weiner H L, Hancock W W. CCR5 (+) and CXCR3 (+) T cells are increased in multiple sclerosis and their ligands MIP-1alpha and IP-10 are expressed in demyelinating brain lesions. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:6873–6878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.12.6873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Benkirane M, Jin D Y, Chun R F, Koup R A, Jeang K T. Mechanism of transdominant inhibition of CCR5-mediated HIV-1 infection by ccr5Δ32. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:30603–30606. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.49.30603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berger E A, Doms R W, Fenyo E-M, Korber B T M, Littman D R, Moore J P, Sattentau Q J, Schuitemaker H, Sodroski J, Weiss R A. HIV-1 phenotype classified by co-receptor usage. Nature (London) 1998;391:240. doi: 10.1038/34571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blanpain C, Migeotte I, Lee B, Vakili J, Doranz B J, Govaerts C, Vassart G, Doms R W, Parmentier M. CCR5 binds multiple CC-chemokines: MCP-3 acts as a natural antagonist. Blood. 1999;94:1899–1905. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bluel C C, Farzan M, Choe H, Parolin C, Clark-Lewis I, Sodroski J, Springer T A. The lymphocyte chemoattractant SDF-1 is a ligand for LESTR/fusin and blocks HIV-1 entry. Nature (London) 1996;382:829–833. doi: 10.1038/382829a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carringtin M, Kissner T, Gerrard B, Ivanov S, O'Brien S J, Dean M. Novel alleles of the chemokine-receptor gene CCR5. Am J Hum Genet. 1997;61:1261–1267. doi: 10.1086/301645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Charo I F, Myers S J, Herman A, Franci C, Connolly A J, Coughlin S R. Molecular cloning and functional expression of two monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 receptors reveals alternative splicing of the carboxyl-terminal tails. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:2752–2756. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.7.2752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen Z, Kwon D, Jin Z, Monard S, Telfer P, Jones M S, Lu C Y, Aguilar R F, Ho D D, Marx P A. Natural infection of a homozygous delta 24 CCR5 red-capped mangabey with an R2b-tropic simian immunodeficiency virus. J Exp Med. 1998;188:2057–2065. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.11.2057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cheng-Mayer C, Seto D, Tateno M, Levy J A. Biologic features of HIV-1 that correlate with virulence in the host. Science. 1988;240:80–82. doi: 10.1126/science.2832945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Choe H, Farzan M, Sun Y, Sullivan N, Rollins B, Ponath P D, Wu L, Mackay C R, LaRosa G, Newman W, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. The beta-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell. 1996;85:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Cocchi F, DeVico A L, Garzino-Demo A, Arya S K, Gallo R C, Lusso P. Identification of RANTES, MIP-1α, and MIP-1β as the major HIV-suppressive factors produced by CD8+ T cells. Science. 1995;270:1811–1815. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5243.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Connor R I, Mohri H, Cao Y, Ho D D. Increased viral burden and cytopathicity correlate temporally with CD4+ lymphocyte decline and clinical progression in human immunodeficiency virus type 1-infected individuals. J Virol. 1993;67:1772–1777. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.4.1772-1777.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dean M, Carrington M, Winkler C, Huttley G A, Smith M W, Allikmets R, Goedert J J, Buchbinder S P, Vittinghoff E, Gomperts E, Donfield S, Vlahov D, Kaslow R, Saah A, Rinaldo C, Detels R, O'Brien S J. Genetic restriction of HIV-1 infection and progression to AIDS by a deletion allele of the CKR5 structural gene. Hemophilia Growth and Development Study, Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study, Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study, San Francisco City Cohort, ALIVE Study. Science. 1996;273:1856–1862. doi: 10.1126/science.273.5283.1856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Deng H, Liu R, Ellmerier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton R E, Hill C M, Davis C B, Peiper S C, Schall T J, Littman D R, Landau N R. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature (London) 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doranz B J, Rucker J, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Samson M, Peiper S C, Parmentier M, Collman R G, Doms R W. A dual-tropic primary HIV-1 isolate that uses fusin and the beta-chemokine receptors CKR-5, CKR-3, and CKR-2b as fusion cofactors. Cell. 1996;85:1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway G P, Martin S R, Huang Y, Nagashima K A, Cayanan C, Maddon P J, Koup R A, Moore J P, Paxton W A. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature (London) 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Feng Y, Broder C C, Kennedy P E, Berger E A. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gong W, Howard O M, Turpin J A, Grimm M C, Ueda H, Gray P W, Raport C J, Oppenheim J J, Wang J M. Monocyte chemotactic protein-2 activates CCR5 and blocks CD4/CCR5-mediated HIV-1 entry/replication. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4289–4292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.8.4289. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gosling J, Monteclaro F S, Atchison R E, Arai H, Tsou C-L, Goldsmith M A, Charo I F. Molecular uncoupling of C-C chemokine receptor 5-induced chemotaxis and signal transduction from HIV-1 coreceptor activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:5061–5066. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.10.5061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hall I P, Wheatley A, Christie G, McDougall C, Hubbard R, Helms P J. Association of CCR5 delta32 with reduced risk of asthma. Lancet. 1999;354:1264–1265. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(99)03425-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hasan M K, Kato A, Shioda T, Sakai Y, Yu D, Nagai Y. Creation of an infectious recombinant Sendai virus expressing the firefly luciferase gene from the 3′ proximal first locus. J Gen Virol. 1997;78:2813–2820. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-11-2813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Howard O M Z, Konno-Shirakawa A, Turpin J A, Maynard A, Tobin G J, Carrington M, Oppenheim J J, Dean M. Naturally occurring CCR5 extracellular and transmembrane domain variants affect HIV-1 co-receptor and ligand binding function. J Biol Chem. 1999;274:16228–16234. doi: 10.1074/jbc.274.23.16228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hu H, Shioda T, Hori T, Moriya C, Kato A, Sakai Y, Matsushima K, Uchiyama T, Nagai Y. Dissociation of ligand-induced internalization of CXCR-4 from its co-receptor activity for HIV-1 Env-mediated membrane fusion. Arch Virol. 1998;143:851–861. doi: 10.1007/s007050050337. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kato A, Sakai Y, Shioda T, Kondo T, Nakanishi M, Nagai Y. Initiation of sendai virus multiplication from transfected cDNA or RNA with negative or positive sense. Genes Cells. 1996;1:569–579. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2443.1996.d01-261.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kostrikis L G, Huang Y, Moore J P, Wolinsky S M, Zhang L, Guo Y, Deutsch L, Phair J, Neumann A U, Ho D D. A chemokine receptor CCR2 allele delays HIV-1 disease progression and is associated with a CCR5 promoter mutation. Nat Med. 1998;4:350–353. doi: 10.1038/nm0398-350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu H, Chao D, Nakayama E E, Taguchi H, Goto M, Xin X, Takamatsu J, Saito H, Ishikawa Y, Akaza T, Juji T, Takebe Y, Ohishi T, Fukutake K, Maruyama Y, Yashiki S, Sonoda S, Nakamura T, Nagai Y, Iwamoto A, Shioda T. Polymorphism in RANTES chemokine promoter affects HIV-1 disease progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:4581–4585. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.8.4581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu R, Paxton W A, Choe S, Ceradini D, Martin S R, Horuk R, MacDonald M E, Stuhlmann H, Koup R A, Landau N R. Homozygous defect in HIV-1 coreceptor accounts for resistance of some multiply-exposed individuals to HIV-1 infection. Cell. 1996;86:367–377. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80110-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mackett M, Smith G L, Moss B. The construction and characterization of vaccinia virus recombinants expressing foreign genes. In: Glover D M, editor. DNA cloning. II. Oxford, England: IRL Press; 1985. pp. 191–211. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Magierowska M, Lepage V, Lien T X, Lan N T, Guillotel M, Issafras H, Reynes J M, Fleury H J, Chi N H, Follezou J Y, Debre P, Theodorou I, Barre-Sinoussi F. Novel variant of the CCR5 gene in a Vietnamese population. Microbes Infect. 1999;1:123–124. doi: 10.1016/s1286-4579(99)80002-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Martin M P, Dean M, Smith M W, Winkler C, Gerrard B, Michael N L, Lee B, Doms R W, Margolick J, Buchbinder S, Goedert J J, O'Brien T R, Hilgartner M W, Vlahov D, O'Brien S J, Carrington M. Genetic acceleration of AIDS progression by a promoter variant of CCR5. Science. 1998;282:1907–1911. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5395.1907. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lalani A S, Masters J, Zeng W, Barrett J, Pannu R, Everett H, Arendt C W, McFadden G. Use of chemokine receptors by poxviruses. Science. 1999;286:1968–1971. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5446.1968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.McDermott D H, Zimmerman P A, Guignard F, Kleeberger C A, Leitman S F, Murphy P M the Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS) CCR5 promoter polymorphism and HIV-1 disease progression. Lancet. 1998;352:866–870. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(98)04158-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Michael N L, Louie L G, Rohrbaugh A L, Schultz K A, Dayhoff D E, Wang C E, Sheppard H W. The role of CCR5 and CCR2 polymorphisms in HIV-1 transmission and disease progression. Nat Med. 1997;3:1160–1162. doi: 10.1038/nm1097-1160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mummidi S, Ahuja S S, Gonzalez E, Anderson S A, Santiago E N, Stephan K T, Craig F E, O'Connell P, Tryon V, Clark R A, Dolan M J, Ahuja S K. Genealogy of the CCR5 locus and chemokine system gene variants associated with altered rates of HIV-1 disease progression. Nat Med. 1998;4:786–793. doi: 10.1038/nm0798-786. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nakayama E E, Shioda T, Tatsumi M, Xin X, Yu D, Ohgimoto S, Kato A, Sakai Y, Ohnishi Y, Nagai Y. Importance of the N-glycan in the V3 loop of HIV-1 envelope protein for CXCR-4- but not CCR-5-dependent fusion. FEBS Lett. 1998;426:367–372. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(98)00375-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nussbaum O, Broder C C, Berger E A. Fusogenic mechanisms of enveloped-virus glycoproteins analyzed by a novel recombinant vaccinia virus-based assay quantitating cell fusion dependent reporter gene activation. J Virol. 1994;68:5411–5422. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5411-5422.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Oberlin E, Amara A, Bachelerie F, Bessia C, Virelizier J L, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Schwartz O, Heard J M, Clark-Lewis I, Legler D F, Loetscher M, Baggiolini M, Moser B. The CXC chemokine SDF-1 is the ligand for LESTR/fusin and prevents infection by T-cell-line-adapted HIV-1. Nature (London) 1996;382:833–835. doi: 10.1038/382833a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ohagen A, Li L, Rosenzweig A, Gabuzda D. Cell-dependent mechanisms restrict the HIV type 1 coreceptor activity of US28, a chemokine receptor homolog encoded by human cytomegalovirus. AIDS Res Hum Retroviruses. 2000;16:27–35. doi: 10.1089/088922200309575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Palacios E, Digilio L, McClure H M, Chen Z, Marx P A, Goldsmith M A, Grant R M. Parallel evolution of CCR5-null phenotypes in humans and in a natural host of simian immunodeficiency virus. Curr Biol. 1998;8:943–946. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(07)00378-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pleskoff O, Treboute C, Brelot A, Heveker N, Seman M, Alizon M. Identification of a chemokine receptor encoded by human cytomegalovirus as a cofactor for HIV-1 entry. Science. 1997;276:1874–1878. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5320.1874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qin S, Rottman J B, Myers P, Kassam N, Weinblatt M, Loetscher M, Koch A E, Moser B, Mackay C R. The chemokine receptor CXCR3 and CCR5 mark subsets of T cells associated with certain inflammatory reactions. J Clin Investig. 1998;101:746–754. doi: 10.1172/JCI1422. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Quillent C, Oberlin E, Braun J, Rousset D, Gonzalez-Canali G, Metais P, Montagnier L, Virelizier J L, Arenzana-Seisdedos F, Beretta A. HIV-1-resistance phenotype conferred by combination of two separate inherited mutations of CCR5 gene. Lancet. 1998;351:14–18. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(97)09185-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Reynes J, Portales P, Segondy M, Baillat V, Andre P, Reant B, Avinens O, Couderc G, Benkirane M, Clot J, Eliaou J F, Corbeau P. CD4+ T cell surface CCR5 density as a determining factor of virus load in persons infected with human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Infect Dis. 2000;181:927–932. doi: 10.1086/315315. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ruffing N, Sullivan N, Sharmeen L, Sodroski J, Wu L. CCR5 has an expanded ligand-binding repertoire and is the primary receptor used by MCP-2 on activated T cells. Cell Immunol. 1998;189:160–168. doi: 10.1006/cimm.1998.1379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Samson M, Libert F, Doranz B J, Rucker J, Liesnard C, Farber C-F, Saragosti S, Lapoumeroulie C, Cognaux J, Forceille C, Muyldermans G, Verhofstede C, Burtonboy G, Geoges M, Imai T, Rana S, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Collman R G, Doms R W, Vassart G, Parmentier M. Resistance to HIV-1 infection in Caucasian individuals bearing mutant alleles of the CCR-5 chemokine receptor gene. Nature (London) 1996;382:722–725. doi: 10.1038/382722a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sellebjerg F, Madsen H O, Jensen C V, Jensen J, Garred P. CCR5 delta32, matrix metalloproteinase-9 and disease activity of multiple sclerosis. J Neuroimmunol. 2000;102:98–106. doi: 10.1016/s0165-5728(99)00166-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shioda T, Shibuta H. Production of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) like particles from cells infected with a recombinant vaccinia virus expressing gag gene of HIV-1. Virology. 1990;175:139–148. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(90)90194-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Smith M W, Dean M, Carrington M, Winkler C, Huttley G A, Lomb D A, Goedert J J, O'Brien T R, Jacobson L P, Kaslow R, Buchbinden S, Vittinghoff E, Vlahov D, Hoots K, Hilgartner M W, O'Brien S J. Contrasting genetic influence of CCR2 and CCR5 variants on HIV-1 infection and disease progression. Hemophilia Growth and Development Study (HGDS), Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS), Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study (MHCS), San Francisco City Cohort (SFCC), ALIVE Study. Science. 1997;277:959–965. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.959. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tersmette M, Lange J M A, DeGoede R E Y, DeWolf F, Schattenkerk J K M E, Schellekens P T A, Coutinho R A, Huisman J G, Goudsmit J, Miedema F. Association between biological properties of human immunodeficiency virus variants and risk for AIDS and AIDS mortality. Lancet. 1989;i:983–985. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)92628-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.van Rij R P, Broersen S, Goudsmit J, Coutinho R A, Schuitemaker H. The role of a stromal cell-derived factor-1 chemokine gene variant in the clinical course of HIV-1 infection. AIDS. 1998;12:F85–F90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Winkler C, Modi W, Smith M W, Nelson G W, Wu X, Carrington M, Dean M, Honjo T, Tashiro K, Yabe D, Buchbinder S, Vittinghoff E, Goedert J J, O'Brien T R, Jacobson L P, Detels R, Donfield S, Willoughby A, Gomperts E, Vlahov D, Phair J, O'Brien S J ALIVE Study; Hemophilia Growth and Development Study (HGDS); Multicenter AIDS Cohort Study (MACS); Multicenter Hemophilia Cohort Study (MHCS); San Francisco City Cohort (SFCC) Genetic restriction of AIDS pathogenesis by an SDF-1 chemokine gene variant. Science. 1998;279:389–393. doi: 10.1126/science.279.5349.389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wong L-M, Myers S J, Tsou C-L, Gosling J, Arai H, Charo I F. Organization and differential expression of the human monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 receptor gene: evidence for the role of the carboxyl-terminal tail in receptor trafficking. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:1038–1045. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.2.1038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wu L, Paxton W A, Kassam N, Ruffing N, Rottman J B, Sullivan N, Choe H, Sodroski J, Newman W, Koup R A, Mackay C R. CCR5 levels and expression pattern correlate with infectability by macrophage-tropic HIV-1, in vitro. J Exp Med. 1997;185:1681–1691. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.9.1681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhu T, Mo H, Wang N, Nam D S, Cao Y, Koup R A, Ho D D. Genotypic and phenotypic characterization of HIV-1 patients with primary infection. Science. 1993;261:1179–1181. doi: 10.1126/science.8356453. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]