Abstract

Celastrol (Cel), derived from the traditional herb Tripterygium wilfordii Hook. f., has anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, and immunoregulatory activities. Renal dysfunction, including acute renal failure, has been reported in patients following the administration of Cel-relative medications. However, the functional mechanism of nephrotoxicity caused by Cel is unknown. This study featured combined use of activity-based protein profiling and metabolomics analysis to distinguish the targets of the nephrotoxic effects of Cel. Results suggest that Cel may bind directly to several critical enzymes participating in metabolism and mitochondrial functions. These enzymes include voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1 (essential for maintaining mitochondrial configurational and functional stability), pyruvate carboxylase (involved in sugar isomerization and the tricarboxylic acid cycle), fatty acid synthase (related to β-oxidation of fatty acids), and pyruvate kinase M2 (associated with aerobic respiration). Proteomics and metabolomics analysis confirmed that Cel-targeted proteins disrupt some metabolic biosynthetic processes and promote mitochondrial dysfunction. Ultimately, Cel aggravated kidney cell apoptosis. These cumulative results deliver an insight into the potential mechanisms of Cel-caused nephrotoxicity. They may also facilitate development of antagonistic drugs to mitigate the harmful effects of Cel on the kidneys and improve its clinical applications.

Keywords: celastrol, nephrotoxicity, chemical proteomics, metabolomics, mitochondrial dysfunction, apoptosis

Introduction

Celastrol (Cel), a natural pentacyclic triterpenoid product with definitive and divergent therapeutic effects, is among the most promising modern drug candidates1. First isolated from the traditional Chinese herb Tripterygium wilfordii Hook. f., it has been long used to treat rheumatoid arthritis2, 3, and was identified as a main constituent exerting anti-inflammatory4 and immunoregulatory functions5. Subsequent studies revealed other pharmacological activities of Cel, including anti-tumor6, anti-obesogenic7, and neuroprotective effects8, with growing interest in its potential as a therapeutic agent. However, one obvious limitation of Cel-related clinical applications is its severe side effects, which include reproductive toxicity9, hepatotoxicity10, and cardiotoxicity11. Illustrating the molecular mechanisms of the toxic effects of Cel would facilitate developing strategies for improving its efficacy and reducing its side effects. Although renal tubular injury and necrosis of renal tubular epithelial cells have been associated with Cel, the mechanisms of nephrotoxicity are poorly understood.

Mitochondria have critical effects on homeostatic regulation, including substance metabolism, apoptosis, and autophagy12. And mitochondrial damage is an important factor in drug toxicity13. Some natural products induce mitochondrial-related cellular apoptosis, contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction14, 15. In addition, excessive accumulation of aristolochic acid in mitochondria-rich proximal tubular epithelial cells evokes apoptosis, eventually leading to nephrotoxicity15, 16. Based on our previous confirmation that Cel liposomes can selectively target proteins in the mitochondrial outer membrane17, we hypothesized that Cel-induced nephrotoxicity is associated with mitochondrial function.

In recent decades, the development and application of chemical proteomics have provided researchers with new perspectives for studying the molecular mechanisms of drug effects18, 19. In particular, activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) is effective for providing a comprehensive understanding of the pharmacological activity, and toxic mechanisms of target compounds, through a combination of activity-based probes and proteomics technologies19-21. We previously used this approach to identify the targets of action of various natural products. For example, aristolochic acid directly affects several crucial enzymes involved in energy metabolism, eventually causing kidney dysfunction15, while capsaicin exerts its therapeutic effect on sepsis by inhibiting pyruvate kinase 2 (PKM2)-LDHA-dependent aerobic glycolysis through direct binding to the cysteine residue of PKM222.

Herein, following our previous chemosynthetic strategy, Cel-probe (Cel-p) was designed with a clickable alkyne tag, based on Cel structure23, 24. This localized structural change has a negligible effect on Cel pharmacological activity20. In addition, covalent binding between Cel-p to fluorescent tags (TAMRA-azide) or affinity tags (biotin-azide) via a click reaction enables visualization of Cel-targeted proteins, and subsequent enrichment and identification20, 23. Using chemical proteomics based on ABPP and metabolomics, we analyzed and identified the covalent binding targets of Cel in the kidney.

Our findings indicated that numerous Cel-targeted proteins participate in several vital biological activities, particularly mitochondrial function. Validation of several important enzymes was then undertaken using cellular thermal shift assay-western blotting (CETSA-WB) and pull down-western blotting (PD-WB). Evidence of Cel involvement in multiple metabolic activities and mitochondrial functional impairment was further supported by metabolomics and proteomics analysis, and by measuring JC-1 monomer levels. Our cumulative results imply that Cel nephrotoxicity may function through intricate mechanisms that target specific proteins. Our research provides a prospective approach and new insights into the toxicologic molecular mechanisms of compounds.

2. Materials and methods

2.1 Reagents

Cel (purity ≥98%) was obtained from Bethealth People Biomedical Technology (Beijing, China). Cel-p, with a clickable alkyne tag, was synthesized and validated as previously described23-25. Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was bought from AbMole BioScience (Houston, TX, USA). Cell counting Kit-8 (CCK8) was purchased from Solarbio Life Sciences (Beijing, China). N-Acetyl-L-cysteine (NAC) was sourced from Yeasen Corporation (Shanghai, China). Essential reagents for the click reaction (Tris [3-hydroxypropyltriazolylmethyl] amine [THPTA], vitamin C sodium [NaVc], CuSO4, and TAMRA-azide or Biotin-azide), and liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) were used, as previously reported15, 20, 25. Of note, in the PD tandem mass tags (TMT) and PD-WB experiment, biotin-azide was added for the click reaction, rather than the TAMRA-azide used in cellular imaging or fluorescence labeling assay in situ20, 25. Sodium deoxycholate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA), dithiothreitol (Sigma-Aldrich, Germany), and iodoacetamide (IAA, Sigma-Aldrich, Germany) were used for proteomics analysis26. Primary antibodies against Bax, Bcl2, cytochrome C (Cyt C), caspase-3, β-actin, PKM2, and pyruvate carboxylase (PC) were purchased from Proteintech (Chicago, IL, USA). Primary antibodies against fatty acid synthase (FASN) were sourced from Abcam (Cambridge, UK). Primary antibody against voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1 (VDAC1) was obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA, USA).

2.2 Cell culture and viability detection assay

A human renal tubular epithelial cell line (HK-2) was purchased from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas, VA, USA) and cultured as previously reported15. A specific density of HK-2 cells was seeded and cultured, in 96-well plates overnight. Subsequently, cells were treated with Cel or Cel-p at different concentrations for 24 h. Cell activity was assessed using the CCK8 kit to determine the effects of treatment of Cel or Cel-p. Densitometric conditions for cell passaging and drug management were as previously described15.

2.3 Animal experiments

Animal experiment protocols were approved by the Laboratory Animal Care and Use Center of Shenzhen People's Hospital (Shenzhen China, IACUC NO. AUP-230105-LP-569-01). Male (25 ± 5 g, 12 weeks) and female (20 ± 2 g, 12 weeks) C57 BL/6 wild-type mice were housed under standard conditions. Mice were allowed to acclimatize to their environment for 1 week before experimentation. Cel was dissolved in DMSO and diluted with corn oil. Mice in the control group were treated with corn oil. Mice in the treatment group were administered Cel (5 mg/kg/d, intraperitoneally [i.p.]) for 5 days27, 28. After anesthesia and euthanasia, blood and kidney tissue samples were extracted. Kidney tissues were fixed with paraformaldehyde (PFA) or stored at -80 °C.

2.4 Blood biochemistry and histology

Serum levels of creatinine (Crea) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) were measured by the respective test kits (Jiancheng Biotechnology, Nanjing, China)29. After embedding kidney tissues were sliced into 4 μm sections and staining (hematoxylin and eosin [H&E], Masson's trichrome) was carried out to assess histologic changes and evaluate the extent of fibrotic lesions. Kidney tubular injury score was assigned, as described previously30.

2.5 Mitochondrial function and cell apoptosis detection assay

Cell mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP), detected with the MitoScreen™ (JC-1 staining) kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was assessed according to the proportion of mitochondrial monomers. The CCCP group was used as a positive control for inducing a MMP decrease. BD Pharmingen™ FITC Annexin V Apoptosis Detection Kit (BD Biosciences, USA) was used to detect the percentage of apoptotic cells with Cel treatment31.

Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) Assay Kit (S0026, Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was used to detect cellular ATP contents. Cells were washed with cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then ATP lysate was added, and the supernatant was centrifuged for the ATP test (luminometer, Spark Multifunctional Microplate Tester, Tecan, Switzerland)32. NAC pretreatment for 2 h was followed by co-treatment with Cel for 24 h.

2.6 Western blotting

Proteins from kidney tissue and cells were detected using polyvinylidene difluoride membranes after being separated on sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Corresponding primary and secondary antibodies were added to samples followed by incubation. ChemiScope 6100 Fully Automatic Chemiluminescence Imaging System (Qinxiang, Shanghai, China) was used to visualize protein bands using the Omni-ECL™ Femto Light Chemiluminescence Kit (Epizyme, Shanghai, China). Protein expression was semi-quantified following the normalization of WB bands with ImageJ (United States National Institutes of Health, USA).

Based on its simple, reliable principle of thermodynamic stabilization and operational workflow33, CETSA was used to measure bond stabilities between Cel and targeted proteins. Briefly, the same quantity of crude protein samples, isolated from HK-2 cells or kidney tissue, were heated with the CETSA heat-pulse machine (Applied Biosystems, Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA) for 5 min after incubation with Cel (20 µM) or DMSO lasting about 30 min25. After centrifugation, the supernatant was used for WB assay. The gray value at 37°C was used as a reference for each group, and plotted for analysis25, 34.

WB experiments on mitochondrial extraction of kidney tissues were conducted using the Tissue Mitochondria Isolation Kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China)35. Briefly, tissue samples were minced, mitochondrial isolation reagent added, supernatant centrifuged to obtain the crude cytosol protein, and precipitate added to the mitochondrial lysate to obtain the mitochondrial crude protein. Next, WB procedures were carried out.

2.7 Cellular imaging in situ

Fluorescence imaging was implemented, as previously described34. A specific number of cells was seeded on four-chamber glass-bottom dishes overnight, after which they were exposed to complete medium containing DMSO or Cel-p (1 µM). Cells were washed after 4 h, then fixed with 4% PFA at room temperature (RT) for 15 min. Samples were washed gently twice and then permeabilized using 0.2% Triton X-100. Cells were pretreated with fresh cocktails (THPTA, NaVc, CuSO4, and TAMRA-azide) prepared according to an established protocol8. Then, a click reaction was carried out (2 h, at RT). Cells were cultivated with specific primary antibodies (concentration per manufacturer instructions) overnight at 4 °C. After two rounds of gentle washing with PBS, cells were incubated for 1.5 h with a secondary fluorescent antibody (Alexa Fluor 488; Abcam) at a dilution of 1:1000. Then, cells were washed three times with PBS. Finally, cells were incubated with Hoechst or DAPI for 60 min at RT before image capture, following previously reported procedures24.

2.8 Fluorescence labeling assay for cells in situ and recombinant protein VDAC1

This assay was conducted on cells cultivated at an appropriate density for adaptation. Cells were pretreated with Cel (5 μM, as a competitor) for 1 h (only in the competitor group) and then treated with Cel-p (0.5, 1, 2, or 4 μM) or DMSO for 3-4 h. Proteins were quantified and their same quantities were taken from each group for click reaction with fresh cocktail (THPTA, NaVc, CuSO4, and TAMRA-azide), lasting for 2 h at RT. Precipitation, denaturation, electrophoresis, and visualization of labeled proteins (using fluorescence imaging scanner [Azure C400, USA]) were implemented as described previously8, 24, 25. A similar approach was taken to label and visualize the recombinant protein VDAC124.

2.9 Appraisal of pulldown and LC-MS/MS-based targets

Based on the competitive ABPP approach, potent and selective drug targets can be efficiently detected and identified by combined LC-MS/MS analysis21. Cells in the competitor group were co-processed with Cel-p (1 μM) for 3 h after Cel pretreatment for 1 h. Subsequently, the extracted protein was subjected to click chemistry for 4 h with fresh click cocktails (THPTA, NaVc, CuSO4, and Biotin-azide)8, 15, 25. Cel-p was bound to streptavidin beads through affinity labeling25. Bead-captured targets during the pulldown process were tracked and identified using isotope labeling. A high concentration of SDS (1.5%) was applied to dissolve the protein precipitates obtained from acetone, and stored at low temperatures. Subsequently, protein samples were diluted and centrifuged. They were then co-incubated with beads for 6 h. Peptides were obtained using elution, reduction, alkylation, and enzyme digestion; they were then desalted. Qualitative and quantitative analyses of peptide samples labeled with TMT 10-plexTM Mass Tag Reagent (Thermo, Waltham, MA, USA). Then, labeled peptides were classified and validated with LC-MS/MS (Orbitrap Fusion Lumos, Thermo, USA) following an established protocol15, 24, 25. A sample of the collected protein was set aside for detection by PD-WB before the enzyme reaction15.

2.10 Label-free proteomics analysis by LC-MS/MS

Proteomics provides insights into potential targets of functional and molecular mechanisms of treatments by analyzing differentially expressed proteins (DEPs) in treated and untreated samples36, 37. HK-2 cells with Cel or DMSO treatment were lysed in sodium deoxycholate buffer. Then, reduction, alkylation, precipitation, and digestion of lysates in dithiothreitol, IAA, acetone, trypsin, and other solutions were conducted step-by-step. Ultimately, samples were analyzed by LC-MS/MS, and data acquisition was conducted in data-dependent acquisition mode, as previously described38. Downstream protein profile analysis was conducted with the DEP package (version 1.18.0), with DEPs selected if absolute fold change (FC) was >1.2 and a P < 0.0539-41. Analyses of the functional enrichment of genes were done using the Gene Ontology (GO) database (https://geneontology.org/) and visualized using the “clusterprofiler” package (version 3.18.1) in R (R Institute for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria)26.

2.11 Synthesis and purification of recombinant human protein

VDAC1 was cloned into a pCold I vector with a 6 His-tag fusion (Sangon, Shanghai, China). Reporter plasmids were transformed into the Escherichia coli BL21 strain and cultured under particular conditions26. Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside was used to induce VDAC1 expression. Subsequently, bacteria were collected and fragmented, followed by centrifugation to isolate inclusion bodies. After undergoing denaturation, renaturation, and elution, the VDAC1 protein was obtained26. VDAC1 concentration was determined and recorded by Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). The integrity and purity of the purified protein were examined using SDS-PAGE stained with coomassie brilliant blue (CBB).

2.12 LC-MS/MS metabolomics analysis

Kidney tissues (100 mg) of male mice were grounded and resuspended with prechilled 80% methanol. Samples were incubated with a gradient of methanol (4 °C) and centrifuged prior to injection into the LC-MS/MS system for analysis42, 43. Ultra-high performance (UHP) LC-MS/MS analysis was conducted with a Vanquish UHPLC system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germany), which was coupled with an Orbitrap Q ExactiveTM ultra-high-field orbitrap mass spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Germany). Samples were injected onto a Hypersil Goldcolumn using a certain linear gradient and flow rate. Q ExactiveTM HF mass spectrometer was run in positive/negative polarity mode44.

Raw data recorded by UHPLC-MS/MS was calculated with the Compound Discoverer 3.1 (Thermo Fisher Scientific) to capture peak alignment, peak selection, and quantitation for each metabolite, and to predict the molecular formula. Metabolite identification was then performed by comparing the high-resolution secondary spectral databases mzCloud (https://www.mzcloud.org/), mzVault, and MassList primary database search (library search). Statistical analyses were performed using R (version 3.4.3), Python (version 2.7.6) and CentOS (release 6.6). When data were non-normally distributed, they were standardized to obtain relative peak areas. Compounds with CVs of relative peak areas in quality control (QC) samples >30% were removed, and final metabolite identifications and relative quantification results were obtained42.

Principal components analysis (PCA) was used to distinguish the distribution trends of samples in the groups receiving Cel or DMSO, using metaX software, QC PCA, PCA, and partial least squares discriminant analysis (PLS-DA)45. Selection of differentially expressed metabolites (DEMs) mainly relied on the parameters of variable importance in the projection (VIP), FC, and t-test P-values46, with thresholds set at VIP >1.0, FC >1.5 or FC <0.667 and P <0.0547-49. Definition and analysis of DEMs and classification of annotation was based on the Human Metabolome Database (HMDB; https://hmdb.ca/)15.

2.13 Molecular docking

Three-dimensional (3D) Cel structure information was downloaded from PubChem (https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). Detail information of targeted proteins VDAC1 (6TIR), PC (7WTA), PKM2 (8G2E), and FASN (3TJM) were obtained from the Protein Data Bank (PDB). To describe the structures of ligand and protein, we used the AutoDock Tools (https://autodock.scripps.edu/). Patterns of interaction between Cel and targeted proteins were computed using AutoDock Vina and PyRx 0.8 (https://pyrx.sourceforge.io/). Ultimately, analysis and visualization of all docking data were carried out by PyMOL (https://pymol.org/2/)26.

2.14 Statistical analyses

Identified through a minimum of three separate investigations, data from all analyses were presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean (SEM), except where noted. One-way ANOVA was applied to analyze data between groups. Two-sample unpaired t-tests were also conducted. Prism 8.2 (GraphPad, La Jolla, CA, USA) was conducted to analyze statistical data.

3. Results

3.1 Cel induced acute kidney injury and apoptosis in mouse kidney cells

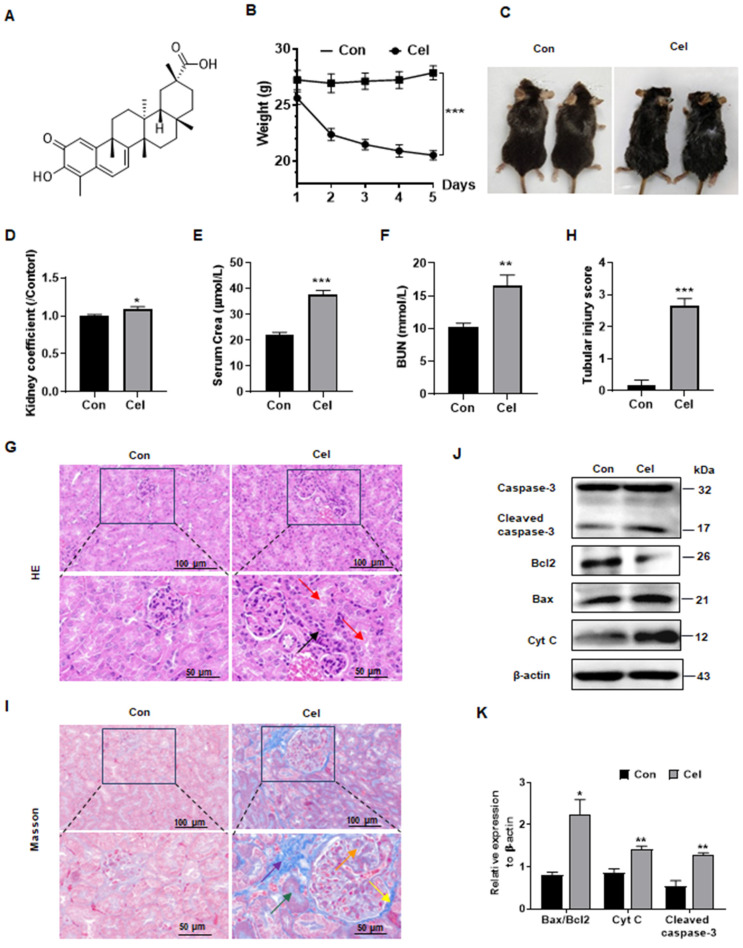

To investigate Cel nephrotoxicity (structural information as shown in Figure 1A)27, we conducted a series of in vivo experiments (Figure 1B-K). Cel administration significantly reduced C57 male mice bodyweight (Figure 1B) and caused cosmetic changes, including dehydration and loss of fur luster (Figure 1C). The kidney coefficient (kidneys weight/bodyweight) of male mice was increased upon Cel treatment (Figure 1D), suggesting an obvious toxic effect of Cel. Male mice in the Cel group exhibited severe kidney dysfunction with a significant increase in serum levels of Crea (Figure 1E) and BUN (Figure 1F). H&E staining (Figure 1G) demonstrated inflammatory cell infiltration in the renal interstitium (black arrow) and epithelial cell shedding in the tubular lumen, resulting in the formation of cellular debris (red arrow). The tubular injury score was significantly higher in the Cel group, suggesting kidney damage (Figure 1H). Fibrosis necrosis was observed by Masson's trichrome-staining (Figure 1I), including interstitial fibrosis (purple arrow), tubular fibrosis necrosis (green arrow), proliferation of glomerular thylakoid membrane (orange arrow) and basement membrane (yellow arrow).

Figure 1.

Dysfunction and apoptosis of male mice kidney caused by Cel treatment. (A) Cel chemical structure. (B) Bodyweight reduction was caused by Cel (5 mg/kg/d, i.p.) in male C57 mice (n = 6, p < 0.001). (C) Mouse appearance. (D) Cel increased mouse kidney coefficient (n = 6, p = 0.04). Cel treatment caused kidney dysfunction in mice, resulting in a significant increase in serum Crea (E, n = 4, p < 0.001), BUN (F, n = 6, p = 0.005). (G) H&E staining, (H) tubular injury score (n = 6, p < 0.001) and (I) Masson trichrome staining of male mouse kidney tissue. Scale bar = 50, 100 μm. (J) Expression and (K) corresponding statistical result of the proteins related to apoptosis in male mouse kidney tissue upon Cel treatment according to WB. Data were analyzed using unpaired two-tailed t-test with Prism 8.2 (mean ± SEM). ns, no significance, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, vs. Control. Con, control, Cel celastrol, Crea creatinine, BUN blood urea nitrogen, H&E hematoxylin and eosin, WB western blotting, Cyt C cytochrome C, SEM standard error of the mean.

Likewise, Cel caused significant bodyweight loss in female mice (Supplementary Figure 1A), and increased kidney coefficient (Supplementary Figure 1B). Cel treatment induced significant renal impairment, including elevated serum Crea (Supplementary Figure 1C) and BUN (Supplementary Figure 1D). Histological data from H&E staining (Supplementary Figure 1E) showed detachment of tubular endothelial cells (blue arrows), renal tubular vacuolization (black arrows), and a significant increase tubular injury score (Supplementary Figure 1F) in female mice with Cel treatment. Similar to the results of male mice, fibrosis of the tubular mesenchyme (red arrows), glomerular mesangium and glomerular basement membranes (yellow arrows) were found in female mouse in Masson staining (Supplementary Figure 1G).

It has been reported that some natural products cause cell apoptosis and induce toxic effects14, 15. Interestingly, as showed in Figure 1J and K: Cyt C expression and cleaved caspase-3 was significantly upregulated, and the Bax/Bcl2 ratio was increased, indicating kidney cell apoptosis. Cumulatively, these data showed that Cel induced obvious kidney damage and that kidney cell apoptosis may be related to mitochondria dysfunction.

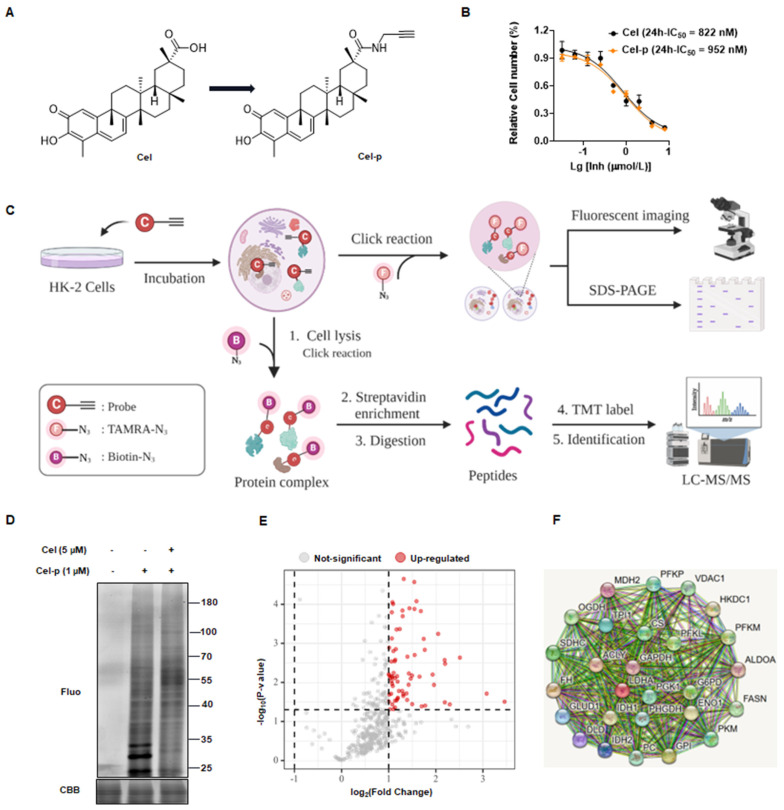

3.2 ABPP strategy was used to identify Cel nephrotoxic targets

To identify potential binding proteins of Cel in the kidney, we synthesized a Cel-p with the structural formula shown in Figure 2A. Cytotoxicities of Cel and Cel-p were highly similar (Figure 2B), suggesting the structural change of alkyne tag accession had little impact on Cel pharmacological activity. Therefore, Cel-p could be used to visualize and identify Cel targets using the ABPP method (Figure 2C). Results showed that plentiful proteins were labeled by probes, and fluorescence intensity increased in Cel-p concentration-dependent manner (Supplementary Figure 2A). Proteins labeled with Cel-p in situ were outcompeted by the co-incubation with excessive Cel (Figure 2D). As described above, the potent and selective binding targets (see red points) were pulled down by beads, enriched by biotin-azide and streptavidin, labeled with TMT reagent, and finally identified via LC-MS/MS analysis (Figure 2E). Moreover, analyses of signaling-pathway enrichment disclosed the biological processes (BPs) associated with these target proteins (Supplementary Figure 2B). Target proteins bound directly with Cel were involved in critical metabolic pathways, including the tricarboxylic acid (TCA) cycle (Supplementary Figure 2C). Notably, rate-limiting enzymes such as VDAC1, PC, PKM2, and FASN were highlighted in the protein-protein interaction (PPI) network according to the Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins (i.e., STRING) databases (https://cn.string-db.org/) (Figure 2F). Therefore, they were selected for Cel binding validation in vivo and in vitro.

Figure 2.

Using ABPP method to identify Cel nephrotoxic targets. (A) Cel-p chemical structure. (B) Toxicity of Cel and Cel-p on HK-2 cells. (C) Workflow of the strategy combining ABPP and click chemistry (schematic). This figure was created using www.biorender.com. (D) Excess Cel competed with labeled protein for binding to Cel-p in situ. (E) Volcano plot of the pulldown and identified proteins (red points) in Cel vs. DMSO groups by ABPP. (F) PPI network of target proteins (partial) of Cel bound to HK-2 cells. ABPP activity-based protein profiling, Cel celastrol, Cel-p celastrol probe, LC-MS/MS liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, TMT tandem mass tags, Fluo fluorescence, CBB coomassie brilliant blue, PPI protein-protein interaction.

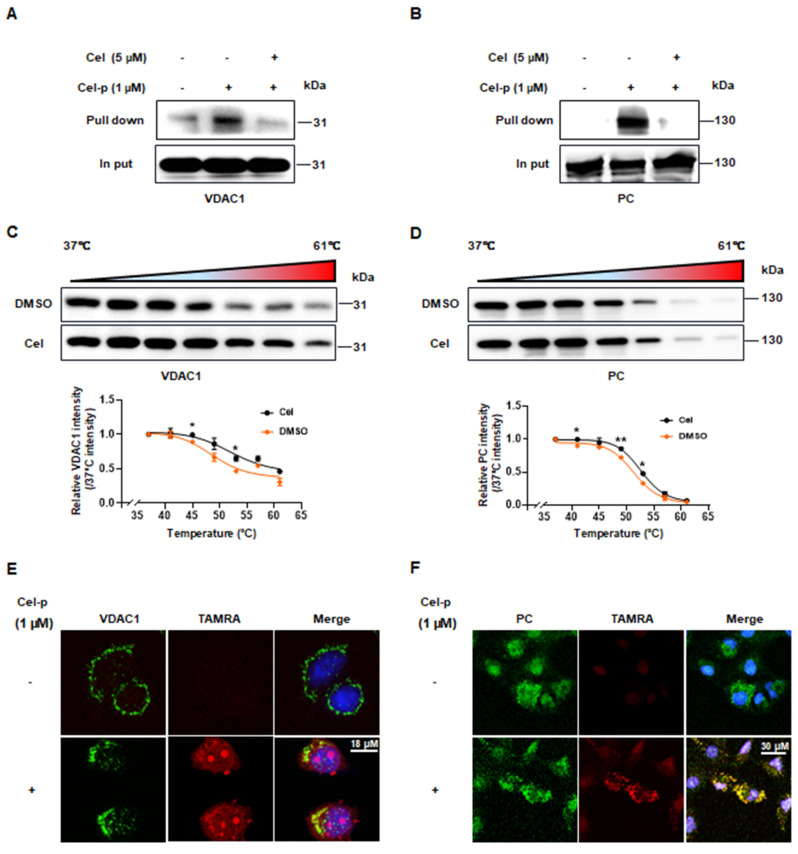

3.3 Cel targets validated by combined PD-WB and CETSA-WB

PD-WB and CETSA-WB were conducted to further validate the target and mechanism of Cel nephrotoxicity. PD-WB results from HK-2 cell lysates showed that VDAC1 (Supplementary Figure 3A) and PKM2 (Supplementary Figure 3B) could be effectively pulled down, and that a high Cel dose could compete effectively with Cel-p. It also showed significant downward pulldown effects of PC (Supplementary Figure 3C) and FASN (Supplementary Figure 3D) with Cel-p, though the competition effect was slightly inferior. CETSA-WB of cells lysates showed that VDAC1 (Supplementary Figure 3E) and PC (Supplementary Figure 3F) exhibited similar thermal stability between groups, while it was higher in the Cel-treated group in PKM2 (Supplementary Figure 3G) and FASN (Supplementary Figure 3H). Their interaction was further indicated by results obtained from kidney tissue lysates. As expected, VDAC1 (Figure 3A) and PC (Figure 3B) were pulled down by Cel-p, and competed away by overdose of Cel. Moreover, VDAC1 (Figure 3C), PC (Figure 3D), PKM2 (Supplementary Figure 4A), and FASN (Supplementary Figure 4B) exhibited greater thermal stability in the Cel-treated group than in those treated with DMSO. Taken together, these results demonstrated that these proteins directly and stably bind with Cel.

Figure 3.

Validation of Cel by combining PD-WB and CETSA-WB. (A and B) PD-WB and input WB were carried out in kidney lysates to measure levels of VDAC1 and PC upon treatment with Cel-p and/or excess Cel. CETSA-WB from kidney lysate samples of VDAC1 (C, n =3, 45oC, p = 0.04; 53oC, p = 0.01) and PC (D, n =3, 41oC, p = 0.01; 49oC, p = 0.004; 53oC, p = 0.01) curves corresponding to the grayscale values of WB stripes were shown (repeated three times). Co-localization of VDAC1 (E) and PC (F) and Cel-p in cells was determined by fluorescence staining. Data were analyzed using an unpaired two-tailed t-test with Prism 8.2 (mean ± SEM). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, vs. Control. Cel celastrol, PD-WB, pull down-western blotting, CETSA-WB, cellular thermal shift assay Western blotting, Cel-p celastrol probe, VDAC1 voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1, PC pyruvate carboxylase, SEM standard error of the mean.

Furthermore, immunofluorescence staining revealed that Cel co-localized with VDAC1 (Figure 3E), PC (Figure 3F), PKM2 (Supplementary Figure 4C), and FASN (Supplementary Figure 4D) in HK-2 cells. However, the pharmacological effects on expression of these proteins remain unknown, and thus require further investigation. WB results (Supplementary Figure 4E and F) showed a significant reduction of FASN but obvious increase of PKM2.

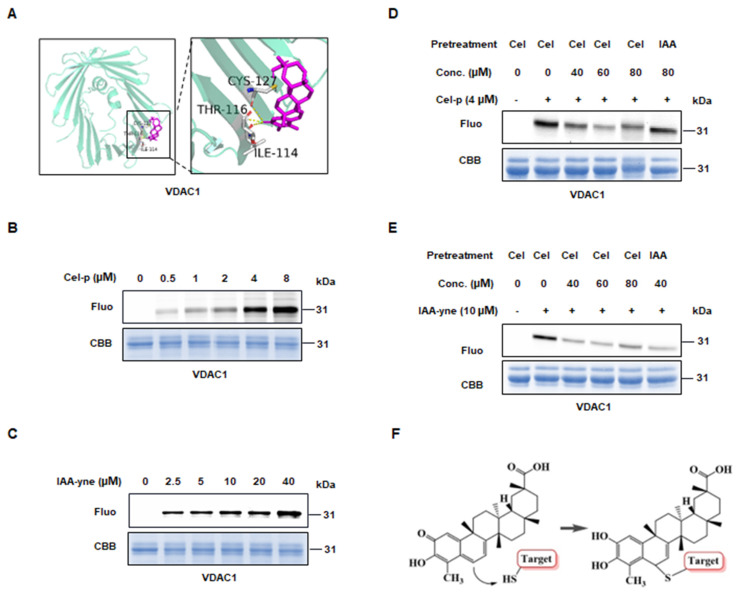

To predict the potential binding sites of Cel targets, we conducted molecular docking using the resolved structure of proteins. Probably interrelations occurred between: ILE114, THR116, and CYS127 of VDAC1 with Cel (Figure 4A); CYS663, GLU664, LYS667, and GLU668 of PC (Supplementary Figure 5A); LYS162, ASN163, CYS165, LYS166, and LYS188 of PKM2 (Supplementary Figure 5B); and ASP2291, CYS2292, and LEU 2231 of FASN (Supplementary Figure 5C) as possibly bound to Cel. These results suggested that Cel targets specific cysteines in VDAC1, PC, PKM2, and FASN. Next, IAA (Cys-alkylator) was used to determine whether Cel binds targets through cysteines sites. Recombined VDAC1, purified by the methods described above, was co-incubated with probes, after which a click reaction using TAMRA-azide was conducted. The fluorescence intensity of the protein-probe binding was shown to be dose-dependent (Figure 4B and C), indicating that Cel combined VDAC1 by covalent means. Then, VDAC1 protein was pretreated with an overdose of Cel or IAA, incubated with probes, and subjected to a click reaction. Cel-p was competed away by Cel and IAA, despite its slightly weaker effectiveness (Figure 4D and E). Change of Cel chemical structure after binding targets was demonstrated (Figure 4F). These data implied that cysteine residue may be the Cel-VDAC1 binding group. These cumulative findings reveal that Cel induced kidney dysfunction by targeting multiple crucial metabolic enzymes, and that cysteine residue is the key Cel target-induced nephrotoxicity binding group.

Figure 4.

Directly binding between Cel and VDAC1. (A) Predicted binding sites of VDAC1 with Cel by Autodock. Yellow dotted lines represent hydrogen bonds, and purple sticks represent Cel compounds. (B) Cel-p and (C) IAA-yne labeling of recombined human VDAC1 protein (1-2 µg) in a dose-dependent manner. (D) Cel-p and (E) IAA-yne labeling of recombined human VDAC1 protein was done in the presence or absence of corresponding competitors. (F) Chemical changes of Cel upon binding with targets using a model presentation. Cel celastrol, IAA iodoacetamide, VDAC1 voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1, Fluo fluorescence, CBB coomassie brilliant blue, Conc. concentration, IAA iodoacetamide, CYS cystine, THR threonine, ILE isoleucine.

3.4 Proteomics analysis revealed in vitro Cel impaired mitochondrial function

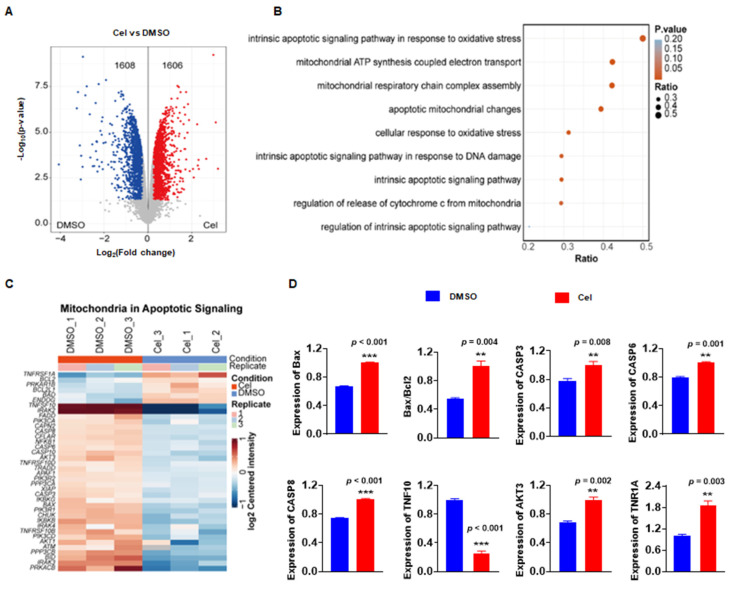

Cel-induced nephrotoxicity targets have been identified and confirmed by ABPP, CETSA-WB, PD-WB, and other methods. However, the potential molecular signaling pathways and BPs were unknown. Thus, a proteomics analysis of cell samples was undertaken. Compared with the DMSO group, the Cel-treated group exhibited 1608 proteins with downregulated expression and 1606 proteins with upregulated expression (Figure 5A). Analyses of signaling pathways showed that the most pathway-enriched DEPs were associated with mitochondrial metabolism, oxidative stress, and apoptosis (Figure 5B). Cluster analysis was used to assess mitochondrial apoptotic signaling of the specific DEPs (Figure 5C). These proteins were also quantified, and the expression of most was significantly upregulated with Cel treatment, including caspase-3, Bax/Bcl2, caspase-6, and AKT3 (Figure 5D). Indeed, our results from WB of tissue lysates (Figure 1J and K) confirmed that Cel induced mitochondria-related apoptosis in vivo.

Figure 5.

Proteomics analysis demonstrated that Cel caused mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in vitro. (A) Volcano plot depicting DEPs in Cel vs. Control (DMSO) groups. (B) Bubble diagram illustrating the analysis of signaling-pathway enrichment for DEPs using the KEGG database. (C) Cluster analysis of DEPs. (D) Statistical analyses of apoptosis related proteins among DEPs. Data were calculated by unpaired two-tailed t-test (mean ± SEM, n = 3). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, vs. Control. Cel celastrol, DEPs differentially expressed proteins, SEM standard error of the mean.

Taken together, proteomics analysis showed that Cel can damage kidney cells through BPs related to mitochondrial metabolism, oxidative stress, and apoptosis.

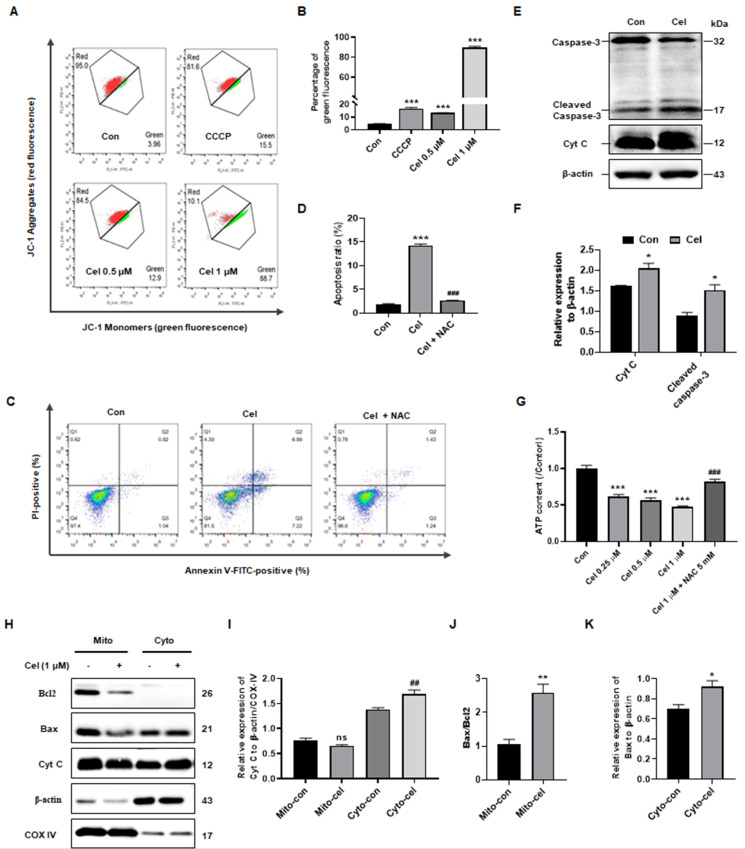

3.5 Cel reduced MMP and aggravated apoptosis in vitro

Based on data from kidney tissues (Figure 1J and K) and proteomics analysis of cell samples (Figure 5A-D), Cel treatment was found to impact the expression of genes related to apoptosis, particularly those associated with mitochondria. Flow cytometry was then conducted to further investigate alterations in mitochondria. JC-1 detection revealed that Cel reduced MMP of cells in a concentration-dependent manner, indicating an early stage of apoptosis (Figure 6A and B). The pro-apoptotic effects of Cel were largely blocked by NAC (Figure 6C and D). WB results confirmed a significant release of Cyt C and cleaved caspase-3 induced by Cel treatment in HK-2 cells (Figure 6E and F). Furthermore, ATP levels reduced in a concentration-dependent manner after 24 h with Cel administration, but pretreatment with NAC (2 h) rescued this decrease (Figure 6G). WB analysis of mitochondria isolated from mouse tissues (Figure 6H) showed a slight decrease in mitochondrial Cyt C expression in the Cel group, but an obvious up-regulation in the cytosol group (Figure 6I). Additionally, the Bax/Bcl2 ratio in mitochondria was significantly higher in the Cel group compared with the control group (Figure 6J), while Bax expression in the cytosol group was also significantly increased following Cel treatment (Figure 6K).

Figure 6.

Cel reduced MMP and induced apoptosis in HK-2 cells. (A) JC-1 monomers of HK-2 cells were measured and (B) statistical analyses for different concentrations of Cel (n = 3, p < 0.001). (C and D) The apoptosis of cells was detected with Cel treatment or NAC pretreatment (5 mM) (n = 3, p < 0.001). (E and F) Expression of apoptosis-related proteins was measured by WB (n = 3, Cyt C, p = 0.02; cleaved caspase-3, p = 0.02). (G) ATP content of HK-2 cells with Cel treatment (n = 3, p < 0.001, ###p < 0.001 for Cel + NAC vs. Cel). (H) The WB assay was detected in mitochondria and cytosol isolated from male mice kidneys. (I) The expression of Cyt C in mitochondria and in cytosol (n = 3, ##p = 0.007, cyto-cel vs. cyto-con). (J) The ratio of Bax/Bcl2 in mitochondria (n = 3, **p = 0.006, mito-cel vs. mito-con). (K) The expression of Bax in cytosol (n = 3, *p = 0.04, cyto-cel vs. cyto-con). Data in B, D, and G were analyzed using one-way ANOVA, and data in F, I, J, and K were used unpaired two-tailed t-test with Prism 8.2 (mean ± SEM). ns, no significance, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001, vs. Control. Cel celastrol, MMP mitochondrial membrane potential, NAC N-Acetyl-L-cysteine, ATP, adenosine triphosphate, WB western blotting, SEM standard error of the mean.

In summary, Cel treatment induced nephrotoxicity through dysfunction in ATP metabolism and mitochondria-dominated apoptosis.

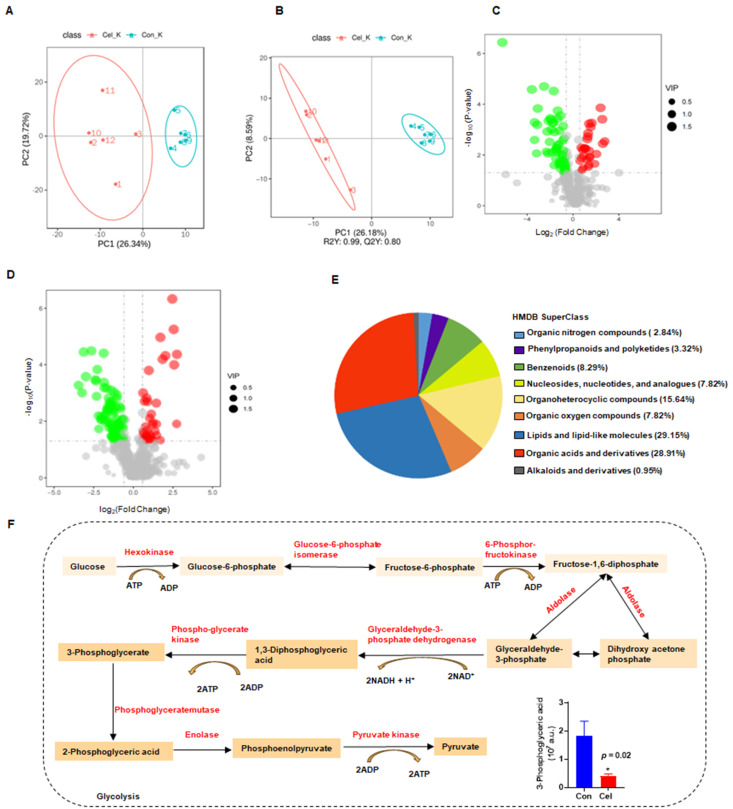

3.6 Nontargeted metabolomics analysis identified the primary metabolic pathways involved in Cel nephrotoxicity

UHPLC-MS/MS was used to analyze kidney tissue and characterize Cel nephrotoxicity. First, the QC of kidney samples was high in terms of their intercorrelations, both of negative ion mode (NIM, Supplementary Figure 6A) and positive ion mode (PIM, Supplementary Figure 6B). Similar results were observed from QC PCA analysis of NIM (Supplementary Figure 6C) and PIM (Supplementary Figure 6D), evidenced by the distribution of QC samples (blue points) clustering together. These results indicated that the quality and stability of samples during analyses were reliable in both ion modes [50]. Additionally, PCA of NIM (Figure 7A) indicated a significant distribution of metabolites with- or without-Cel treatment groups.

Figure 7.

Non-targeted metabolomics analysis revealed the main processes involved in Cel induced-nephrotoxicity. (A) PCA in NIM. (B) Neg PLS-DA score plots of DMSO and Cel groups in kidney tissue. (C and D) Volcano plots showing DEMs in NIM and PIM. (E) Classification annotations (based on HIMDB database) in the kidney following Cel-treatment. (F) Cel regulated the expression of rate-limiting enzymes (highlighted in red) and their corresponding products or substrates (n = 6). Data were analyzed using an unpaired two-tailed t-test with Prism 8.2 (mean ± SEM). *p < 0.05 vs. Control. Cel celastrol, Neg PLS-DA negative partial least squares-discriminant analysis, DEMs differentially expressed metabolites, PIM positive ion mode, NIM negative ion mode, HMDB human metabolome database, SEM standard error of the mean.

Finally, a total of 213 DEMs with obvious differences were detected, including 87 DEMs in NIM and 126 DEMs in PIM. The negative PLS-DA (neg PLS-DA) score was notably different between the DMSO and Cel groups (Figure 7B), with similar results observed in the positive PLS-DA (Supplementary Figure 6E). The metabolites in NIM were classified and determined to be primarily “lipids and lipidlike molecules” (Supplementary Figure 6F). Additionally, as shown in Figure 7C, 28 DEMs had up-regulated expression (red points) and 59 DEMs had downregulated expression (green points) in NIM. While in PIM (Figure 7D), 40 DEMs with upregulated expression (red points) and 86 DEMs with downregulated expression (green points,) were found. Next, we analyzed metabolites from the two ion modes based on the HMDB. The metabolites that changed under Cel treatment were primarily “lipids and lipid-like molecules” (Figure 7E). Cel affected almost all the rate-limiting enzymes associated with the glycolysis pathway (highlighted in red in Figure 7F), resulting in a decrease in the production of 3-phosphoglyceric acid.

In summary, metabolomics analysis suggested that Cel damages critical metabolic processes, including glycolysis, by affecting multiple key enzymes involved in complex molecular patterns.

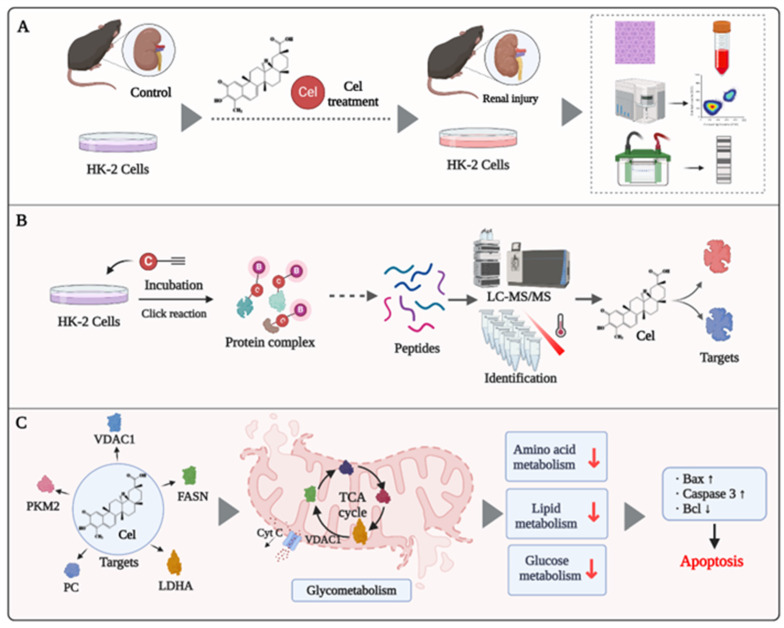

4. Discussion

In recent decades, Cel has been shown to have pharmacological activities, including sensitizing leptin, anti-inflammatory effects, and anti-tumor properties. These features make it a promising drug for the treatment of diabetes mellitus, lupus nephritis, and cancer51, 52. However, limited understanding of its toxicity (particularly nephrotoxicity) hinders Cel development and application. Herein, we achieved a deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying Cel nephrotoxicity by integrating ABPP, CETSA, proteomics, and metabolomics analysis. Multiple and complex mechanisms (e.g., regulation of enzymes participating in the TCA cycle and glycolysis) were involved. Cel treatment caused mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis in kidney cells (Figure 8). Our study thus provides invaluable evidence for preventing the adverse effects of Cel and developing drugs to counteract its nephrotoxicity, thereby facilitating expansion of its clinical applications.

Figure 8.

Potential mechanism of Cel-induced nephrotoxicity (schematic). (A) Cel sources and its nephrotoxicity in vivo and in vitro. (B) Strategy combining ABPP and CETSA to identify and validate the binding targets of Cel on HK-2 cells and kidney tissues. (C) Cel targeted the proteins (enzymes) associated specifically with metabolism, ultimately resulting in mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis. This figure was drawn using www.biorender.com. Cel celastrol, ABPP activity-based protein profiling, CETSA cellular thermal shift assay.

In vivo, Cel generated acute damage to kidney function in mice, resulting in a sharp rise in levels of Crea, BUN, and other renal function indices. Histology revealed clear vacuolization, fibrosis, and necrosis of renal tubular cells, along with glomerular hyperplasia and fibrotic degeneration. Furthermore, in kidney tissue and cell lysates, expression of Bax/Bcl2, CytC, and caspase-3 was upregulated significantly, indicating exacerbated apoptosis and kidney tissue damage following Cel treatment (Figure 8A). These effects were alike nephropathy influenced by aristolochic acid15. Previous studies have indicated that drugs with an IC50 <1 µM can exhibit potent inhibition on multiple ion channels11. Accordingly, our data suggests that Cel impaired VDAC1 expression, thereby disrupting the relevant functions of mitochondria and inducing kidney cell apoptosis or necrosis. The JC-1 assay also showed that Cel diminished the MMP and caused apoptosis. Combining TMT and metabolomics analysis revealed that Cel regulated various key enzymes related to energy metabolism. CETSA-WB and PD-WB further confirmed the specific damaging effect of Cel on VDAC1, PC, PKM2, and FASN (Figure 8B). Cel overdose downregulated several crucial components of the TCA cycle and glycolysis resulting in mitochondrial metabolic disorders and apoptosis (Figure 8C).

It was confirmed that PKM2 expression is up-regulated under stimuli such as toxicity studies, or oxidative stress53. Similarly, WB of kidney lysate showed that PKM2 expression increased with treatment of Cel. In line with Cao et al., it was observed that FASN expression was significantly downregulated in the Cel group, suggesting that Cel treatment inhibited lipid metabolism54. Clarification of the specific mechanism of these results will need further investigation.

Mitochondrial structural integrity is essential for their function and maintenance of intracellular homeostasis. Indeed, drug toxicity can promote apoptosis by disrupting the integrity of the mitochondrial membrane and the internal structure of cells15, 55. Impairment of mitochondrial function is closely associated with the development of acute kidney injury56, diabetic kidney disease57, and chronic kidney disease58. Our study confirmed that Cel causes dysfunction and apoptosis of mitochondria. This was verified including by WB experiment of isolation from mitochondria and cytosol, JC-1 test, and ATP content detected. Furthermore, as the 'gatekeeper' of mitochondria, VDAC1 is an essential component of the outer mitochondrial membrane (OMM). It plays a crucial part in regulating vital physiological processes, such as metabolism and apoptosis59. We discovered that Cel decreased the MMP, implying damage to the OMM. Studies have shown that if VDAC1 is overexpressed, it undergoes a transition to an oligomeric state, leading to macropore formation60. These macropores increase the OMM permeability, facilitating release of apoptosis-related proteins (e.g., Cyt C) into the cytoplasm60, 61. VDAC1 oligomerization is a feature of the early stage of apoptosis61-63. The corresponding cascade reaction is subsequently activated, including caspase family proteins that induce apoptosis. Moreover, VDAC1 interacts with BAX family proteins, such as Bax and Bcl2, to promote the apoptotic program60, 61, which was validated by the results of WB and proteomics analyses herein. Moreover, VDAC1 participates in substrate metabolism, including the TCA cycle, glycolysis, and lipid metabolism63, 64. These functions may be undertaken by regulating calcium ions in mitochondria, as well as substances such as pyruvate in the cytoplasm65, 66. Therefore, Cel caused nephrotoxicity via complex pathways involved in important mitochondrial BPs.

Though our findings further identify the covalent targets of Cel, these experimental methods were insufficient to identify the non-covalent or reversible binding proteins of Cel. In addition, while we focused on the mechanisms of Cel nephrotoxicity in the hyperacute phase, we did not investigate subacute or prolonged Cel nephrotoxicity. Moreover, that a substantial portion of in vivo data was obtained from male mice, which may be a limitation as we were unable to determine sex differences in the mechanism of Cel-induced nephrotoxicity. These information gaps should be further explored.

In summary, we have reported herein, for the first time, that the nephrotoxicity elicited by Cel may primarily occur by targeting mitochondrial proteins and inducing mitochondrial dysfunction, which ultimately leads to apoptosis.

5. Conclusion

By combining ABPP, CETSA, metabolomics, and proteomics analyses, we discovered that Cel directly targets critical enzymes involved in the TCA cycle, glycolysis, lipid metabolism, and amino acid metabolism. Cel treatment led to mitochondrial dysfunction, ultimately resulting in kidney cell apoptosis. Our findings provide new insights into the mechanism of Cel nephrotoxicity.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary figures.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by National Key Research and Development Program of China (2020YFA0908000); the Shenzhen Medical Research Fund (B2302051), the Science and Technology Foundation of Shenzhen (Shenzhen Clinical Medical Research Center for Geriatric Diseases); the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 82074098), Shenzhen Governmental Sustainable Development Fund (KCXFZ20201221173612034), Shenzhen key Laboratory of Kidney Diseases (ZDSYS201504301616234), Shenzhen Fund for Guangdong Provincial High-level Clinical Key Specialties (No. SZGSP001), and Shenzhen Fundamental Research Foundation (JCYJ20210324113001005), Medical research Fund of Shenzhen Medical Academy of Research and Translation(C2301004), Shenzhen Fund for Guangdong Provincial High-level Clinical Key Specialties (SZGSP001).

Data availability

Details of the data used to support the results of this study are obtainable upon request from the corresponding author.

Author contributions

Xinzhou Zhang, Jigang Wang and Piao Luo conceived and supervised this project. Ming Lei performed probe synthesis and manuscript revised. Xueying Liu and Qian Zhang were responsible for the main experiments, manuscript craft and revision, and data analysis. Peili Wang and Xin Peng performed MS and metabolomics data analysis, Letai Yi was responsible for some experiments in vivo and in vitro. Yehai An, Shuanglin Qin and Junhui Chen conducted molecular docking and some raw data analysis. Jingnan Huang, Hengkai He, Mingjing Hao, and Jiahang Tian carried out western blot and recombined protein purification.

Abbreviations

- Cel

Celastrol

- ABPP

activity-based protein profiling

- PKM2

pyruvate kinase 2

- Cel-p

Cel-probe

- CETSA

cellular thermal shift assay

- CETSA-WB

CETSA western blotting

- PD-WB

pull down-western blotting

- DMSO

deferoxamine mesylate

- CCK8

Cell counting Kit-8

- NAC

N-Acetyl-L-cysteine

- THPTA

Tris (3-hydroxypropyltriazolylmethyl) amine

- NaVc

vitamin C sodium

- LC-MS/MS

liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry

- TMT

tandem mass tags

- IAA

iodoacetamide

- Cyt C

cytochrome C

- PC

pyruvate carboxylase

- FASN

fatty acid synthase

- VDAC1

voltage-dependent anion-selective channel protein 1

- HK-2

human renal tubular epithelial cell line

- PFA

paraformaldehyde

- i.p.

intraperitoneally

- Crea

creatinine

- BUN

blood urea nitrogen

- H&E

hematoxylin and eosin

- MMP

mitochondrial membrane potential

- ATP

adenosine triphosphate

- PBS

phosphate-buffered saline

- SDS

sodium dodecyl sulfate

- PAGE

polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis

- RT

room temperature

- DEPs

differentially expressed proteins

- FC

fold change

- GO

gene ontology

- CBB

coomassie brilliant blue

- UHP

ultra-high performance

- QC

quality control

- PCA

principal components analysis

- PLS-DA

partial least squares discriminant analysis

- DEMs

differentially expressed metabolites

- VIP

variable importance in the projection

- HMDB

human metabolome database

- 3D

there-dimensional

- PDB

Protein Data Bank

- SEM

standard error of the mean

- BPs

biological processes

- TCA

tricarboxylic acid

- PPI

protein-protein interaction

- STRING

Search Tool for the Retrieval of Interacting Genes/Proteins

- Conc.

concentration

- CYS

cystine

- THR

threonine

- ILE

isoleucine

- CYS

cystine

- GLU

glutamic acid

- LYS

lysine

- ASN

asparagine

- LEU

leucine

- NIM

negative ion mode

- PIM

positive ion mode

- OMM

outer mitochondrial membrane

- Con

control

- ns

no significance

References

- 1.Corson TW, Crews CM. Molecular understanding and modern application of traditional medicines: triumphs and trials. Cell. 2007;130:769–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang X, Xia J, Jiang Y, Pisetsky DS, Smolen JS, Mu R. et al. 2023 International Consensus Guidance for the use of Tripterygium Wilfordii Hook F in the treatment of active rheumatoid arthritis. J Autoimmun. 2024;142:103148. doi: 10.1016/j.jaut.2023.103148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.T Chou PM. Study on Chinese herb LeiGongTeng Tripterygium wilfordii hook f.I: the coloring substance and the sugars. Chinese journal of physiology. 1936;10:529–34. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yang J, Liu J, Li J, Jing M, Zhang L, Sun M. et al. Celastrol inhibits rheumatoid arthritis by inducing autophagy via inhibition of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Int Immunopharmacol. 2022;112:109241. doi: 10.1016/j.intimp.2022.109241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shirai T, Nakai A, Ando E, Fujimoto J, Leach S, Arimori T. et al. Celastrol suppresses humoral immune responses and autoimmunity by targeting the COMMD3/8 complex. Science Immunol. 2023;8:eadc9324. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.adc9324. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wang C, Dai S, Zhao X, Zhang Y, Gong L, Fu K. et al. Celastrol as an emerging anticancer agent: Current status, challenges and therapeutic strategies. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;163:114882. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Xu S, Feng Y, He W, Xu W, Xu W, Yang H. et al. Celastrol in metabolic diseases: progress and application prospects. Pharmacol Res. 2021;167:105572. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105572. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu DD, Luo P, Gu L, Zhang Q, Gao P, Zhu Y. et al. Celastrol exerts a neuroprotective effect by directly binding to HMGB1 protein in cerebral ischemia-reperfusion. J Neuroinflammation. 2021;18:174. doi: 10.1186/s12974-021-02216-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bai JP, Shi YL, Fang X, Shi QX. Effects of demethylzeylasteral and celastrol on spermatogenic cell Ca2+ channels and progesterone-induced sperm acrosome reaction. Eur J Pharmacol. 2003;464:9–15. doi: 10.1016/s0014-2999(03)01351-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin C, Wu Z, Wang L, Kanai Y, He X. CYP450s-activity relations of celastrol to interact with triptolide reveal the reasons of hepatotoxicity of Tripterygium wilfordii. Molecules. 2019;24:2162. doi: 10.3390/molecules24112162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sun H, Liu X, Xiong Q, Shikano S, Li M. Chronic inhibition of cardiac Kir2.1 and HERG potassium channels by celastrol with dual effects on both ion conductivity and protein trafficking. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:5877–5884. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M600072200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kasahara A, Scorrano L. Mitochondria: from cell death executioners to regulators of cell differentiation. Trends in Cell Bio. 2014;24:761–770. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2014.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliveira CA, Mercês ÉAB, Portela FS, Malheiro LFL, Silva HBL, De Benedictis LM. et al. An integrated view of cisplatin-induced nephrotoxicity, hepatotoxicity, and cardiotoxicity: characteristics, common molecular mechanisms, and current clinical management. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2024;28:711–727. doi: 10.1007/s10157-024-02490-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Li Y, Xie J, Du X, Chen Y, Wang C, Liu T. et al. Oridonin, a small molecule inhibitor of cancer stem cell with potent cytotoxicity and differentiation potential. Eur J Pharmacol. 2024;975:176656. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2024.176656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhang Q, Luo P, Chen J, Yang C, Xia F, Zhang J. et al. Dissection of targeting molecular mechanisms of aristolochic acid-induced nephrotoxicity via a combined deconvolution strategy of chemoproteomics and,etabolomics. Int J Biol Sci. 2022;18:2003–2017. doi: 10.7150/ijbs.69618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Maeoka Y, Doi T, Aizawa M, Miyasako K, Hirashio S, Masuda Y. et al. A case report of adult-onset COQ8B nephropathy presenting focal segmental glomerulosclerosis with granular swollen podocytes. BMC Nephrol. 2020;21:376. doi: 10.1186/s12882-020-02040-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luo P, Zhang Q, Shen S, An Y, Yuan L, Wong Y-K. et al. Mechanistic engineering of celastrol liposomes induces ferroptosis and apoptosis by directly targeting VDAC2 in hepatocellular carcinoma. Asian J Pharm Sci. 2023;18:100874. doi: 10.1016/j.ajps.2023.100874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bantscheff M, Scholten A, Heck AJR. Revealing promiscuous drug-target interactions by chemical proteomics. Drug Discov Today. 2009;14:1021–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.drudis.2009.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gersch M, Kreuzer J, Sieber SA. Electrophilic natural products and their biological targets. Nat Prod Rep. 2012;29:659–682. doi: 10.1039/c2np20012k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen X, Wang Y, Ma N, Tian J, Shao Y, Zhu B. et al. Target identification of natural medicine with chemical proteomics approach: probe synthesis, target fishing and protein identification. Signal Transduct Target Ther. 2020;5:72. doi: 10.1038/s41392-020-0186-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Deng H, Lei Q, Wu Y, He Y, Li W. Activity-based protein profiling: Recent advances in medicinal chemistry. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;191:112151. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Q, Luo P, Xia F, Tang H, Chen J, Zhang J. et al. Capsaicin ameliorates inflammation in a TRPV1-independent mechanism by inhibiting PKM2-LDHA-mediated Warburg effect in sepsis. Cell Chem Biol. 2022;29:1248–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2022.06.011. e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baskin JM, Prescher JA, Laughlin ST, Agard NJ, Chang PV, Miller IA. et al. Copper-free click chemistry for dynamic in vivo imaging. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:16793–16797. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707090104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Luo P, Liu D, Zhang Q, Yang F, Wong YK, Xia F. et al. Celastrol induces ferroptosis in activated HSCs to ameliorate hepatic fibrosis via targeting peroxiredoxins and HO-1. Acta Pharm Sin B. 2022;12:2300–2314. doi: 10.1016/j.apsb.2021.12.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Luo P, Zhang Q, Zhong TY, Chen JY, Zhang JZ, Tian Y. et al. Celastrol mitigates inflammation in sepsis by inhibiting the PKM2-dependent Warburg effect. Mil Med Res. 2022;9:22. doi: 10.1186/s40779-022-00381-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.An Y, Zhang Q, Chen Y, Xia F, Wong YK, He H. et al. Chemoproteomics reveals Glaucocalyxin A induces mitochondria-dependent apoptosis of leukemia cells via covalently binding to VDAC1. Adv Biol (Weinh) 2023;8:e2300538. doi: 10.1002/adbi.202300538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hou W, Liu B, Xu H. Celastrol: Progresses in structure-modifications, structure-activity relationships, pharmacology and toxicology. Eur J Med Chem. 2020;189:112081. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2020.112081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu L, Hu Y, Ding X, Zhou S, Tang L, Shi J. Comparison on acute toxicity of celastrol derived from in vivo and in vitro methods. J Environ Occup Med. 2015;32:535–548. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ding Y, Xu M, Lu Q, Wei P, Tan J, Liu R. Combination of honey with metformin enhances glucose metabolism and ameliorates hepatic and nephritic dysfunction in STZ-induced diabetic mice. Food Funct. 2019;10:7576–7587. doi: 10.1039/c9fo01575b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ma H, Guo X, Cui S, Wu Y, Zhang Y, Shen X. et al. Dephosphorylation of AMP-activated protein kinase exacerbates ischemia/reperfusion-induced acute kidney injury via mitochondrial dysfunction. Kidney Int. 2022;101:315–330. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiao K, Su P, Li Y. FGFR2 modulates the Akt/Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway to improve angiotensin II-induced hypertension-related endothelial dysfunction. Clin Exp Hypertens. 2023;45:2208777. doi: 10.1080/10641963.2023.2208777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Peng X, Gan J, Wang Q, Shi Z, Xia X. 3-Monochloro-1,2-propanediol (3-MCPD) induces apoptosis via mitochondrial oxidative phosphorylation system impairment and the caspase cascade pathway. Toxicology. 2016;372:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.tox.2016.09.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Molina DM, Jafari R, Ignatushchenko M, Seki T, Larsson EA, Dan C. et al. Monitoring drug target engagement in cells and tissues using the cellular thermal shift assay. Science. 2013;341:84–87. doi: 10.1126/science.1233606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang Q, Luo P, Zheng L, Chen J, Zhang J, Tang H. et al. 18beta-glycyrrhetinic acid induces ROS-mediated apoptosis to ameliorate hepatic fibrosis by targeting PRDX1/2 in activated HSCs. J Pharm Anal. 2022;12:570–582. doi: 10.1016/j.jpha.2022.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang S, Tang Y, Liu T, Zhang N, Yang X, Yang D. et al. A novel antioxidant protects against contrast medium-induced acute kidney injury in rats. Front Pharmacol. 2020;11:599577. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2020.599577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Malmgren L, Öberg C, den Bakker E, Leion F, Siódmiak J, Åkesson A. et al. The complexity of kidney disease and diagnosing it - cystatin C, selective glomerular hypofiltration syndromes and proteome regulation. J Intern Med. 2023;293:293–308. doi: 10.1111/joim.13589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Matías-García PR, Wilson R, Guo Q, Zaghlool SB, Eales JM, Xu X. et al. Plasma proteomics of renal function: a transethnic meta-analysis and mendelian randomization study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2021;32:1747–1763. doi: 10.1681/ASN.2020071070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gao P, Liu Y-Q, Xiao W, Xia F, Chen J-Y, Gu L-W. et al. Identification of antimalarial targets of chloroquine by a combined deconvolution strategy of ABPP and MS-CETSA. Mil Med Res. 2022;9:30. doi: 10.1186/s40779-022-00390-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhong J, He X, Gao X, Liu Q, Zhao Y, Hong Y. et al. Hyodeoxycholic acid ameliorates nonalcoholic fatty liver disease by inhibiting RAN-mediated PPARα nucleus-cytoplasm shuttling. Nat Commun. 2023;14:5451. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-41061-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luo A, Jia Y, Hao R, Zhou X, Bao C, Yang L. et al. Proteomic and phosphoproteomic analysis of right ventricular hypertrophy in the pulmonary hypertension rat model. J Proteome Res. 2023;23:264–276. doi: 10.1021/acs.jproteome.3c00546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li W, Li S, Tang C, Klosterman SJ, Wang Y. Kss1 of Verticillium dahliae regulates virulence, microsclerotia formation, and nitrogen metabolism. Microbiol Res. 2024;281:127608. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2024.127608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Martens A, Holle J, Mollenhauer B, Wegner A, Kirwan J, Hiller K. Instrumental drift in untargeted metabolomics: Optimizing data quality with intrastudy QC samples. Metabolites. 2023;13:665. doi: 10.3390/metabo13050665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Want EJ, Masson P, Michopoulos F, Wilson ID, Theodoridis G, Plumb RS. et al. Global metabolic profiling of animal and human tissues via UPLC-MS. Nat Protoc. 2012;8:17–32. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2012.135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Feng L, Zhang Y, Liu W, Du D, Jiang W, Wang Z. et al. Effects of heat stress on 16S rDNA, metagenome and metabolome in Holstein cows at different growth stages. Sci Data. 2022;9:644. doi: 10.1038/s41597-022-01777-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wen B, Mei Z, Zeng C, Liu S. metaX: a flexible and comprehensive software for processing metabolomics data. BMC Bioinformatics. 2017;18:183. doi: 10.1186/s12859-017-1579-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Rao G, Sui J, Zhang J. Metabolomics reveals significant variations in metabolites and correlations regarding the maturation of walnuts (Juglans regia L.) Biol Open. 2016;5:829–836. doi: 10.1242/bio.017863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haspel JA, Chettimada S, Shaik RS, Chu J-H, Raby BA, Cernadas M. et al. Circadian rhythm reprogramming during lung inflammation. Nature Commun. 2014;5:4753. doi: 10.1038/ncomms5753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Sreekumar A, Poisson LM, Rajendiran TM, Khan AP, Cao Q, Yu J. et al. Metabolomic profiles delineate potential role for sarcosine in prostate cancer progression. Nature. 2009;457:910–914. doi: 10.1038/nature07762. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Research Misconduct Found]

- 49.Heischmann S, Quinn K, Cruickshank-Quinn C, Liang L-P, Reisdorph R, Reisdorph N. et al. Exploratory metabolomics profiling in the kainic acid rat model reveals depletion of 25-hydroxyvitamin D3 during epileptogenesis. Sci Rep. 2016;6:31424. doi: 10.1038/srep31424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Zhang Y, Nie H, Yan X. Metabolomic analysis provides new insights into the heat-hardening response of Manila clam (Ruditapes philippinarum) to high temperature stress. Sci Total Environ. 2023. 857. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 51.Song J, He GN, Dai L. A comprehensive review on celastrol, triptolide and triptonide: Insights on their pharmacological activity, toxicity, combination therapy, new dosage form and novel drug delivery routes. Biomed Pharmacother. 2023;162:114705. doi: 10.1016/j.biopha.2023.114705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Liu J, Lee J, Salazar Hernandez Mario A, Mazitschek R, Ozcan U. Treatment of obesity with celastrol. Cell. 2015;161:999–1011. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Liang J, Cao R, Wang X, Zhang Y, Wang P, Gao H. et al. Mitochondrial PKM2 regulates oxidative stress-induced apoptosis by stabilizing Bcl2. Cell Res. 2017;27:329–351. doi: 10.1038/cr.2016.159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Cao B, Deng H, Cui H, Zhao R, Li H, Wei B. et al. Knockdown of PGM1 enhances anticancer effects of orlistat in gastric cancer under glucose deprivation. Cancer Cell Int. 2021;21:481. doi: 10.1186/s12935-021-02193-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Qi L, Li Y, Dong Y, Ma S, Li G. Integrated metabolomics and transcriptomics reveal glyphosate based-herbicide induced reproductive toxicity through disturbing energy and nucleotide metabolism in mice testes. Environ Toxicol. 2023;38:1811–23. doi: 10.1002/tox.23808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Tong D, Xu E, Ge R, Hu M, Jin S, Mu J. et al. Aspirin alleviates cisplatin-induced acute kidney injury through the AMPK-PGC-1alpha signaling pathway. Chem Biol Interact. 2023;380:110536. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2023.110536. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Myakala K, Wang XX, Shults NV, Krawczyk E, Jones BA, Yang X. et al. NAD metabolism modulates inflammation and mitochondria function in diabetic kidney disease. J Biol Chem. 2023;299:104975. doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2023.104975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Kayhan M, Vouillamoz J, Rodriguez DG, Bugarski M, Mitamura Y, Gschwend J. et al. Intrinsic TGF-beta signaling attenuates proximal tubule mitochondrial injury and inflammation in chronic kidney disease. Nat Commun. 2023;14:3236. doi: 10.1038/s41467-023-39050-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Singh V, Khalil MI, De Benedetti A. The TLK1/Nek1 axis contributes to mitochondrial integrity and apoptosis prevention via phosphorylation of VDAC1. Cell Cycle. 2020;19:363–375. doi: 10.1080/15384101.2019.1711317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Shoshan-Barmatz V, Krelin Y, Chen Q. VDAC1 as a player in mitochondria-mediated apoptosis and target for modulating apoptosis. Curr Med Chem. 2017;24:4435–4446. doi: 10.2174/0929867324666170616105200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Keinan N, Tyomkin D, Shoshan-Barmatz V. Oligomerization of the mitochondrial protein voltage-dependent anion channel is coupled to the induction of apoptosis. Mol Cell Biol. 2010;30:5698–5709. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00165-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Zalk R, Israelson A, Garty ES, Azoulay-Zohar H, Shoshan-Barmatz V. Oligomeric states of the voltage-dependent anion channel and cytochrome c release from mitochondria. Biochem J. 2005;386:73–83. doi: 10.1042/BJ20041356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Hu H, Guo L, Overholser J, Wang X. Mitochondrial VDAC1: A potential therapeutic target of inflammation-related diseases and clinical opportunities. Cells. 2022;11:3174. doi: 10.3390/cells11193174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Shoshan-Barmatz V, Shteinfer-Kuzmine A, Verma A. VDAC1 at the intersection of cell metabolism, apoptosis, and diseases. Biomolecules. 2020;10:1485. doi: 10.3390/biom10111485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Denton RM. Regulation of mitochondrial dehydrogenases by calcium ions. Biochim Biophys Acta- 2009;1787:1309–1316. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2009.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cárdenas C, Miller RA, Smith I, Bui T, Molgó J, Müller M. et al. Essential regulation of cell bioenergetics by constitutive InsP3 receptor Ca2+ transfer to mitochondria. Cell. 2010;142:270–283. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.06.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary figures.

Data Availability Statement

Details of the data used to support the results of this study are obtainable upon request from the corresponding author.