Abstract

The blockage of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4) inhibits inflammation and reduces hippocampal neuronal injury in a pilocarpine-induced mouse model of temporal lobe epilepsy. However, the underlying mechanisms remain largely unclear. NF-κB signaling pathway is responsible for the inflammation and neuronal injury during epilepsy. Here, we explored whether TRPV4 blockage could affect the NF-κB pathway in mice with pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus (PISE). Application of a TRPV4 antagonist markedly attenuated the PISE-induced increase in hippocampal HMGB1, TLR4, phospho (p)-IκK (p-IκK), and p-IκBα protein levels, as well as those of cytoplasmic p-NF-κB p65 (p-p65) and nuclear NF-κB p65 and p50; in contrast, the application of GSK1016790A, a TRPV4 agonist, showed similar changes to PISE mice. Administration of the TLR4 antagonist TAK-242 or the NF-κB pathway inhibitor BAY 11-7082 led to a noticeable reduction in the hippocampal protein levels of cleaved IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF, as well as those of cytoplasmic p-p65 and nuclear p65 and p50 in GSK1016790A-injected mice. Finally, administration of either TAK-242 or BAY 11-7082 greatly increased neuronal survival in hippocampal CA1 and CA2/3 regions in GSK1016790A-injected mice. Therefore, TRPV4 activation increases HMGB1 and TLR4 expression, leading to IκK and IκBα phosphorylation and, consequently, NF-κB activation and nuclear translocation. The resulting increase in pro-inflammatory cytokine production is responsible for TRPV4 activation-induced neuronal injury. We conclude that blocking TRPV4 can downregulate HMGB1/TLR4/IκK/κBα/NF-κB signaling following PISE onset, an effect that may underlie the anti-inflammatory response and neuroprotective ability of TRPV4 blockage in mice with PISE.

Graphical Abstract

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10571-022-01249-w.

Keywords: Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4), Neuronal injury, NF-κB signaling pathway, Inflammatory cytokines, Temporal lobe epilepsy

Introduction

Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 (TRPV4), a member of the transient receptor potential vanilloid subfamily (Toft-Bertelsen and MacAulay 2021), is selectively permeable to calcium (Ca2+), and its activation induces Ca2+ influx, which depolarizes the cell membrane and increases the intracellular free calcium concentration ([Ca2+]i) (Nilius and Voets 2013). TRPV4 is widely expressed in neurons, glial cells, vascular endothelial cells, and smooth muscle cells in the brain, including the cerebral cortex, hippocampus, cerebellum, and thalamus (Toft-Bertelsen and MacAulay 2021). TRPV4 can be activated by a wide range of stimuli, including mechanical, hypotonic, and hyperthermic stimulation, as well as arachidonic acid and its metabolites (Rosenbaum et al. 2020). Because of these characteristics, TRPV4 plays an important role in both the regulation of nervous system function and the pathogenesis of nervous system diseases (Kumar et al. 2018). Tuberous sclerosis and cortical dysplasia are often accompanied by refractory epilepsy (Chen et al. 2016a, b). The expression of TRPV4 is markedly increased in cortical nodules or the dysplastic cortex of these patients and is significantly correlated with seizure symptoms (Chen et al. 2016a, b). In mice, high-temperature stimulation can promote epileptic seizures by activating TRPV4 (Shibasaki et al. 2020), while in zebrafish low-temperature treatment can inhibit epileptic discharges in the forebrain by inhibiting TRPV4 (Hunt et al. 2012). The expression of TRPV4 is increased in mice with pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus (PISE), and blocking TRPV4 greatly increases the latency for the development of pilocarpine-induced SE and reduces the success rate of PISE model preparation (Men et al. 2019). These observations suggest that TRPV4 is involved in the pathogenesis of epilepsy.

Epilepsy is a commonly diagnosed central nervous system disease characterized by periodic and unpredictable epileptic seizures (Wang et al. 2008). Inflammatory cytokine levels and inflammatory responses are reportedly enhanced in the cerebrospinal fluid and peripheral blood of patients with epilepsy and brain tissue in animal models of epilepsy (Rizzi et al. 2003; Fisher et al. 2005; de Vries et al. 2016; Mazdeh et al. 2018; Wang et al. 2019). An excessive inflammatory response leads to neuronal damage, resulting in the permanent impairment of the structure and function of neural networks, an important underlying cause of the recurrent spontaneous seizures seen in chronic epilepsy (Vezzani et al. 2008). High mobility group protein B1 (HMGB1) is released from damaged neurons or glial cells and binds to Toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4) on the cell surface, which activates nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB), and consequently also the inflammatory response (Bianchi et al. 2017). The expression of HMGB1 and TLR4 is significantly increased in the serum and focal brain tissue of epileptic patients and hippocampal tissue of rats with kainic acid (KA)- and pentylenetetrazol-induced epilepsy (Kaya et al. 2021). Inhibiting the HMGB1/TLR4 pathway can reduce the convulsion threshold, alleviate the inflammatory response, and lessen nerve damage after epileptic seizures, and was suggested to exert therapeutic effects in patients with refractory epilepsy (Zhao et al. 2017).

The activation of TRPV4 has been reported to promote the release of inflammatory cytokines in the skin, lung, cornea, gastrointestinal tissue, and adipose tissue (Vergnolle 2014; Okada et al. 2016; Dutta et al. 2020; Wiesner et al. 2020). A recent study reported that blocking TRPV4 markedly inhibited the activation of astrocytes and microglia in epileptic mice and reduced the levels of inflammatory cytokines in the hippocampus (Wang et al. 2019). TRPV4 activation can also upregulate NF-κB expression and activate it in dorsal root ganglion neurons (Wang et al. 2015). In the present study, we investigated how TRPV4 blockage affects the HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB pathway in mice with PISE and subsequently explored whether this signaling pathway is responsible for the inflammatory response and neuronal damage induced by TRPV4 activation.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male ICR mice (6 weeks old) weighing 25–30 g were used in this study and were obtained from Oriental Bio Service Inc. (Nanjing, China). All the animals were housed in the Animal Core Facility of Nanjing Medical University under controlled conditions (temperature: 23 ± 2 °C; relative humidity: 55 ± 5%; 12/12 h light/dark cycle; free access to food and water). Each cage contained four to five mice. This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Medical University (No. IACUC2009007) and all animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Laboratory Animal Research set by Nanjing Medical University. Each experimental group contained nine mice (see Supplementary Methods). The present study did not perform the sample size calculation. The sample size (number of mice) was determined based on the magnitude and consistency of measurable differences between multiple groups.

Preparation of PISE Model Mice

Mice were first intraperitoneally (ip.) injected with methylscopolamine (1 mg/kg) to inhibit peripheral muscarinic activity. After 20 min, pilocarpine (300 mg/kg) was injected (ip.) to induce SE (Wang et al. 2019). Seizure severity was rated using the Racine scale (Racine 1972). SE was defined as the onset of category 4–5 seizures and was terminated after 1 h using diazepam (10 mg/kg). Animals that did not develop category 4–5 seizures within 30 min of pilocarpine injection were excluded from subsequent parts of the study. Control mice were injected with the same volume of saline.

Drug Administration

GSK1016790A (a TRPV4 agonist) and HC-067047 (a TRPV4 antagonist) were administered by intracerebroventricular (icv.) injection, and TAK-242 (a TLR4 antagonist) and BAY 11-7082 (an NF-κB inhibitor) by ip. injection, as previously described (Miyamoto et al. 2010; Hua et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2019). For icv. injection, mice were anesthetized with ketamine (100 mg/kg)/xylazine (10 mg/kg; i.p.) and then were placed in a stereotaxic device (Kopf Instruments, Tujunga, CA, USA). A guide cannula of 23-gauge stainless steel tubing was implanted into the right lateral ventricle (0.3 mm posterior, 1.0 mm lateral, and 2.5 mm ventral to bregma) and anchored to the skull with stainless steel screws and dental cement. Drugs were slowly injected into the right lateral ventricle using a 26-gauge stainless steel needle (Plastics One, Roanoke, VA, USA) at the rate of 0.2 μL/min. GSK1016790A (1 μM) or HC-067047 (10 μM) was injected once daily for 3 consecutive days. To block TRPV4 following SE induction, HC-067047 (10 μM) was injected 1 h after SE was terminated and then once daily for 3 days. TAK-242 (3 mg/kg) and BAY 11-7082 (5 mg/kg) were injected 30 min before GSK1016790A injection and subsequently once daily for 3 days. The doses of the above drugs were chosen based on previous reports (Miyamoto et al. 2010; Hua et al. 2015; Wang et al. 2019).

Western Blot Analysis

Hippocampal samples were obtained 8 h after the last injection of GSK1016790A or HC-067047 or 3 days after SE induction. Total protein was extracted using the Whole Cell Lysis Assay Kit from Nanjing KeyGen Biotech Co., Ltd (Cat: KGP250; Nanjing, China) while nuclear and cytosolic proteins were extracted using the Nuclear/Cytosol Fractionation Kit (Cat: R0050, Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd, Beijing, China) according to the manufacturers’ protocols. The protein concentrations were determined using a BCA Protein Assay Kit (Pierce, Rochford, IL, USA). Equal amounts of protein (20 μg) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes. After blocking using 5% nonfat milk in Tris-buffered saline (TBS)/Tween20, the membranes were incubated with primary antibodies against TLR4 (Cat: sc-293072, 1:300, Santa Cruz Biotechnology Inc., Dallas, TX, USA); HMGB1 (Cat: 10829-1-AP, 1:1,000), IL-1β (Cat: 16806-1-AP, 1:1000), TNF (Cat: 17590-1-AP, 1:1000), IL-6 (Cat: 21865-1-AP, 1:1000), and Lamin B1 (Cat: 12987-1-AP, 1:3000) (all from Proteintech Group Inc., Wuhan, China); phosphorylated (p)-NF-κB p65 (Ser536) (Cat: AF2006, 1:1000) and p-IκK (Ser180/Ser181) (Cat: AF3013, 1:1000) (both from Affinity Biosciences, Zhenjiang, China); IκBα (Cat:4814, 1:1000) and NF-κB p65 (Cat: 8242, 1:1000) (both from Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA); p-IκBα (Ser36) (Cat: ab133462, 1:20,000), IκK (Cat: ab178870, 1:1000), and NF-κB p105/p50 (Cat:ab32360, 1:5000) (all from Abcam, Cambridge, MA, USA); and glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) (Cat: AP0063, 1:1000, Bioworld Technology, Minneapolis, MN, USA) at 4 °C overnight. After washing with TBST, the membranes were incubated with an HRP-labeled secondary antibody, developed using an ECL Detection Kit (Amersham Biosciences, Piscataway, NJ, USA), quantified using a Tanon Digital Gel Imaging Analysis System (Tanon-5200, Shanghai Tanon Science & Technology, Shanghai, China), and analyzed using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health). The primary antibodies were chosen according to previously reports or based on the production introduction (see Supplementary Methods and Materials).

Histological Examination

Anesthetized mice were transcardially perfused with ice-cold phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then with 4% paraformaldehyde 8 h after the last injection of GSK1016790A or HC-067047 or 3 days after the onset of SE. Excised brains were fixed at 4 °C overnight and paraffin-embedded. Coronal sections (5 μm) were cut at the level of the dorsal hippocampus and stained with toluidine blue. The surviving neurons were observed using a light microscope (Olympus DP70, Olympus Corporation, Tokyo, Japan) and quantified as previously described (Hong et al. 2015; Jie et al. 2016).

Chemicals

HC-067047 (Cat: HY-100208), TAK-242 (Cat: HY-11109), and BAY 11-7082 (Cat: HY-13453) were obtained from MedChemExpress (Shanghai, China); pilocarpine (Cat: 14487) and methylscopolamine (Cat: 23862), ketamine (Cat: 11630) and xylazine (Cat: 14113) were obtained from Cayman Chemical Company (Ann Arbor, MI, USA); unless otherwise stated, GSK1016790A (Cat: G0798) and all other chemicals were obtained from Sigma Chemical Company (St Louis, MO, USA).

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed with Statistical Package for Social Sciences, version 26.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Normality of the distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test and variance homogeneity was assessed using Levene’s test before statistical analysis. When the variances are homogeneous, independent samples t-tests or one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test were used for statistical analysis. When the variance are not homogeneous across groups, non-parametric Mann–Whitney U tests or Kruskal–Wallis tests were used for statistical analysis. Significance levels were set at P < 0.05. The experimenters were blind to the control and experimental groups when collecting data. The numbers of surviving cells or protein levels in mice injected with drugs were expressed as percentages of those values in vehicle-injected mice. The numbers of surviving cells or protein levels in mice with PISE were normalized to those of control mice. The protein levels in vehicle- or HC-067047-treated PISE model mice were normalized to those of vehicle-treated control mice. The numbers of surviving cells or protein levels in vehicle- or drug-treated GSK1016790A-injected mice were normalized to those of vehicle-treated control mice (see Supplementary Methods and Materials).

Results

The Levels of HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway-Related Proteins Increase in Mice with PISE

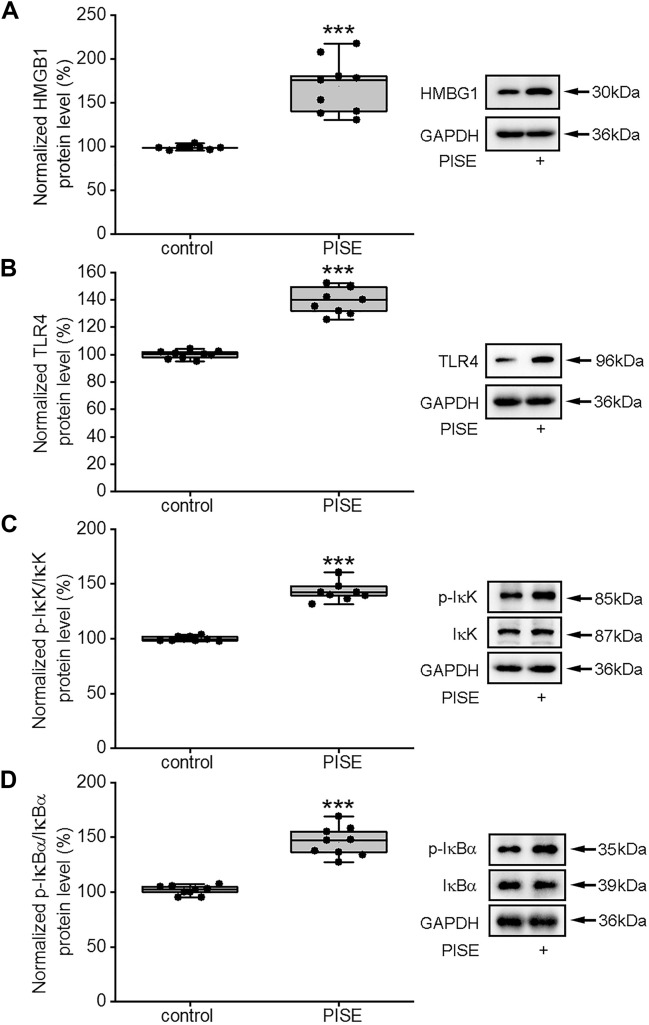

The expression of HMGB1 was reported to be increased in the brain tissue of epileptic model rats, which promoted the synthesis of inflammatory cytokines by activating TLR4, thereby influencing inflammatory responses (Yang et al. 2020). We have recently shown the presence of substantial neuronal damage in the hippocampus 3 days after PISE onset concomitant with an increase in the numbers of activated astrocytes and microglia and the expression of inflammatory cytokines (Wang et al. 2019). In this study, therefore, experiments were performed 3 days after PISE onset. As shown in Fig. 1, compared with the control group, the protein levels of HMGB1 and TLR4 were significantly increased in the hippocampus of mice with PISE (Fig. 1A, B), in line with previously reported results (Zhao et al. 2017).

Fig. 1.

Hippocampal protein levels of HMGB1, TLR4, p-IκK, and p-IκBα increase in mice with PISE. The hippocampal protein levels of HMGB1 (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.001) (A), TLR4 (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.001) (B), p-IκK/IκK (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.001) (C) and p-IκBα/IκBα (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.001) (D) were significantly higher in mice with PISE than in normal controls. ***P < 0.001 versus control (control 1, see Supplementary Methods and Materials). Horizontal lines represented the medians, the boxes in plots represented interquartile range (25th–75th percentile) of each distribution, and the error bars represented the maximum and minimum values

When bound to TLR4, HMGB1 can activate the NF-κB signaling pathway, thereby promoting the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Yang et al. 2020). In most cell types, NF-κB is localized to the cytoplasm and exists primarily as an inactive p50/p65 heterodimer bound to the IκB inhibitory subunit. The activity of IκB is regulated by inhibitor of kappa B kinase (IκK) (Suzuki et al. 2011). We then examined the expression of proteins related to the NF-κB signaling pathway. In this study, the cytosolic protein levels of p-IκK and p-IκB were significantly higher in the hippocampi of mice with PISE than in those of control animals (Fig. 1C, D). As shown in Fig. 2, compared with the control group, the cytosolic protein level of p-NF-κB p65 (p-p65) (Fig. 2A) in the hippocampus increased markedly following SE induction; moreover, the nuclear protein levels of p65 (Fig. 2B) and NF-κB p50 (p50) (Fig. 2C) were also increased. These results suggested that the activity of the HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway was enhanced following PISE onset.

Fig. 2.

Hippocampal protein levels of NF-κB increase in mice with PISE. The cytosolic protein levels of p-p65/p65 (independent samples t test, t = − 10.47, P < 0.001) (A) and the nuclear protein levels of p65 (independent samples t test, t = − 7.47, P < 0.001) (B) and p50 (independent samples t test, t = − 13.17, P < 0.001) (C) were markedly increased in hippocampus of mice with PISE. ***P < 0.001 versus control (control 1, see Supplementary Methods and Materials). Data were presented as means ± standard deviation

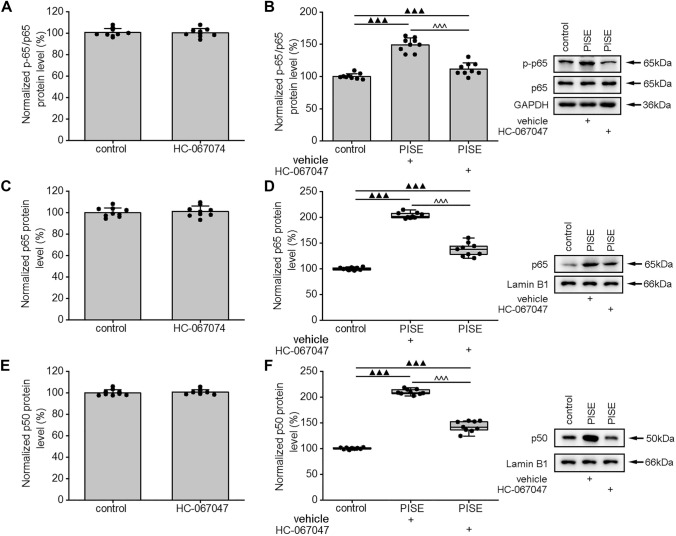

TRPV4 Blockage Inhibits HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway Following PISE Onset

Blocking TRPV4 has been reported to attenuate the inflammatory response in mice with temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) (Wang et al. 2019). Here, we examined whether this effect is related to HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling. First, we determined that the application of HC-067047, a specific antagonist of TRPV4, did not affect the protein levels of either HMGB1 or TLR4 in the hippocampus of control mice (Fig. 3A, C). Subsequently, we found that, compared with vehicle-treated mice with PISE, the hippocampal protein levels of HMGB1 and TLR4 were markedly reduced in model mice administered HC-067047 (Fig. 3B, D). HC-067047 administration did not significantly affect the cytosolic protein levels of p-IκK and p-IκBα in the hippocampi of control mice (Fig. 3E, G), but significantly reduced the levels of both proteins in mice with PISE (Fig. 3F, H). Additionally, neither the cytosolic protein levels of p-p65 nor the nuclear protein levels of p65 or p50 were affected by HC-067047 treatment in control mice (Fig. 4A, C, E). Notably, the cytosolic protein levels of p-p65 and the nuclear protein levels of p65 and p50 were significantly reduced in HC-067047-treated PISE model mice (Fig. 4B, D, F). These results indicated that blocking TRPV4 could reduce the activity of the HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway in mice with status epileptics.

Fig. 3.

HC-067047, a TRPV4 antagonist, reduces the hippocampal protein levels of HMGB1, TLR4, p-IκK, and p-IκBα in mice with PISE. Injection of HC-067047 did not affect the hippocampal protein levels of HMGB1 (independent samples t test, t = 0.94, P = 0.36) (A), TLR4 (independent samples t test, t = 0.44, P = 0.66) (C), p-IκK/IκK (independent samples t test, t = 0.16, P = 0.87) (E), or p-IκBα/IκBα (independent samples t test, t = 0.31, P = 0.76) (G) in control mice, but markedly attenuated those of HMGB1 (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test, F2,24 = 371.01, P < 0.001) (B), TLR4 (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test, F2,24 = 245.64, P < 0.001) (D), p-IκK/IκK (one-way ANOVA followed by Tamhane T2 post hoc test, F2,24 = 82.10, P < 0.001) (F), and p-IκBα/IκBα (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) (H) in mice with PISE. ▲▲▲P < 0.001 versus control (control 3, see Supplementary Methods and Materials), ^^^P < 0.001 versus PISE + vehicle (see Supplementary Methods and Materials). Data were presented as means ± standard deviation in A–E, G and H. In F, horizontal lines represented the medians, the boxes in plots represented interquartile range (25th–75th percentile) of each distribution, and the error bars represented the maximum and minimum values

Fig. 4.

HC-067047 reduces the hippocampal protein levels of NF-κB in mice with PISE. The injection of HC-067047 did not affect the cytosolic protein levels of p-p65/p65 (independent samples t test, t = 0.22, P = 0.83) (A), the nuclear protein levels of p65 (independent samples t test, t = − 0.41, P = 0.68) (C) or p50 (independent samples t test, t = − 0.48, P = 0.64) (E) in the hippocampus of control mice, but markedly attenuated those of p-p65/p65 (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test, F2,24 = 77.56, P < 0.001) (B), p65 (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) (D) and p50 (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) (F) in the hippocampus of mice with PISE. ▲▲▲P < 0.001 versus control (control 3, see Supplementary Table), ^^^P < 0.001 versus PISE + vehicle (see Supplementary Methods and Materials). Data were presented as means ± standard deviation in A–C and E. In D and F, horizontal lines represented the medians, the boxes in plots represented interquartile range (25th–75th percentile) of each distribution, and the error bars represented the maximum and minimum values

GSK1016790A, a TRPV4 Agonist, Increases the Levels of HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB Signaling Pathway-Related Proteins in the Hippocampus

Activation of TRPV4 can enhance the inflammatory response, leading to neuronal injury (Wang et al. 2019). We examined whether activation of TRPV4 could affect HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway. Here, we found that after application of GSK1016790A, the hippocampal protein levels of HMGB1, TLR4 (Fig. 5A, B), p-IκK, and p-IκBα (Fig. 5C, D), as well as the cytosolic protein levels of p-p65 (Fig. 6A) and the nuclear protein levels of p65 and p50 were all markedly increased when compared with those in the control condition (Fig. 6B, C).

Fig. 5.

GSK1016790A, a TRPV4 agonist, increases the protein levels of HMGB1, TLR4, p-IκK, and p-IκBα in the hippocampus. The injection of GSK1016790A markedly increased the hippocampal protein levels of HMGB1 (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.001) (A), TLR4 (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.001) (B), p-IκK/IκK (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.001) (C) and p-IκBα/IκBα (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.001) (D) in control mice. ###P < 0.001 versus control (control 4, see Supplementary Methods and Materials). Horizontal lines represented the medians, the boxes in plots represented interquartile range (25th–75th percentile) of each distribution, and the error bars represented the maximum and minimum values

Fig. 6.

GSK1016790A increases NF-κB protein levels in the hippocampus. The injection of GSK1016790A markedly increased the cytosolic protein levels of p-p65/p65 (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.001) (A), the nuclear protein levels of p65 (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.001) (B) and p50 (Mann-Whitney U test, P < 0.001) (C) in the hippocampus in control mice. ###P < 0.001 versus control (control 4, see Supplementary Methods and Materials). Horizontal lines represented the medians, the boxes in plots represented interquartile range (25th–75th percentile) of each distribution, and the error bars represented the maximum and minimum values

TAK-242, a TLR4 Antagonist, Reduces HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB Pathway-Related Protein Expression in the Hippocampus of GSK1016790A-Injected Mice

TAK-242, a TLR4 antagonist, was used to examine whether GSK1016790A-induced increase of HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB pathway is mediated by TLR4. The application of TAK-242, a TLR4 antagonist, did not change the protein levels of p-IκK and p-IκBα in the hippocampi of control mice (Fig. 7A, C). Compared with vehicle-treated GSK1016790A-injected mice, mice injected with GSK1016790A and co-treated with TAK-242 exhibited greatly reduced p-IκK and p-IκBα protein levels in the hippocampus (Fig. 7B, D). TAK-242 did not affect the cytosolic protein level of p-p65 or the nuclear protein levels of p65 and p50 in hippocampal cells in control mice (Fig. 7E, G, I). Both the cytosolic protein level of p-p65 and the nuclear protein levels of p65 and p50 were markedly reduced in the hippocampi of mice co-injected with GSK1016790A and TAK-242 compared with those in vehicle-treated GSK1016790A-injected mice (Fig. 7F, H, J).

Fig. 7.

TAK-242, a TLR4 antagonist, reduces the hippocampal protein levels of p-IκK, p-IκBα, and NF-κB in GSK1016790A-injected mice. The application of TAK-242 did not affect the hippocampal protein levels of p-IκK/IκK (independent samples t test, t = 0.41, P = 0.69) (A), p-IκBα/IκBα (independent samples t test, t = 1.04, P = 0.31) (C), p-p65/p65 (independent samples t test, t = − 0.06, P = 0.96) (E), p65 (independent samples t test, t = 1.79, P = 0.09) (G) or p50 (independent samples t test, t = 1.67, P = 0.11) (I) in control mice, but markedly attenuated those of p-IκK/IκK (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test, F2,24 = 81.49, P < 0.001) (B), p-IκBα/IκBα (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) (D), p-p65/p65 (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) (F), p65 (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) (H), and p50 (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) (J) in GSK1016790A-injected mice. &&&P < 0.001, &P < 0.05 versus control (control 6, Supplementary Methods and Materials), ~~~P < 0.001 versus GSK1016790A + vehicle (GSK1016790A + vehicle-3, see Supplementary Methods and Materials). Data were presented as means ± standard deviation in A–C, E, G and I. In D, F, H and J, horizontal lines represented the medians, the boxes in plots represented interquartile range (25th–75th percentile) of each distribution, and the error bars represented the maximum and minimum values.

TAK-242 Reduces the Levels of Inflammatory Cytokines in the Hippocampus of GSK1016790A-Injected Mice

The activation of TRPV4 has been reported to promote the release of pro-inflammatory cytokines, and we then examined whether this effect could be affected by TAK-242. Here, we found that the application of TAK-242 did not alter the hippocampal protein levels of cleaved interleukin-1 beta (c-IL-1β), IL-6 or tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF) in control mice (Fig. 8A, C, E). We further observed that TAK-242 administration noticeably reduced hippocampal c-IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF protein levels in GSK1016790A-injected mice (Fig. 8B, D, F).

Fig. 8.

TAK-242 reduces the hippocampal protein levels of inflammatory cytokines in GSK1016790A-injected mice. The application of TAK-242 did not affect the hippocampal protein levels of c-IL-1β (independent samples t test, t = 0.47, P = 0.64) (A), TNF (independent samples t test, t = 0.29, P = 0.76) (C) or IL-6 (independent samples t test, t = − 0.01, P = 0.99) (E) in control mice, but markedly attenuated those of c-IL-1β (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) (B), TNF (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test, F2,24 = 132.07, P < 0.001) (D) and IL-6 (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) (F) in GSK1016790A-injected mice. &&&P < 0.001 versus control (control 6, see Supplementary Methods and Materials), ~~~P < 0.001 versus GSK1016790A + vehicle (GSK1016790A + vehicle-3, see Supplementary Methods and Materials). Data were presented as means ± standard deviation in A, C, D and E. In B and F, horizontal lines represented the medians, the boxes in plots represented interquartile range (25th–75th percentile) of each distribution, and the error bars represented the maximum and minimum values

BAY 11-7082, an NF-κB Signaling Pathway Inhibitor, Reduces the Hippocampal Protein Levels of Pro-inflammatory Cytokines in GSK1016790A-Injected Mice

BAY 11-7082 can inhibit the phosphorylation of IκBα and consequently the NF-κB signaling pathway (Miyamoto et al. 2010). Here, BAY 11-7082 was used to examine whether it could affect GSK1016790A-induced increase of pro-inflammatory cytokines levels. As shown in Fig. 9A, after BAY 11-7082 administration, the cytosolic protein level of p-p65 and the nuclear protein levels of p65 and p50 decreased in the hippocampus in control mice. Compared with the vehicle-treated GSK1016790A-injected mice, GSK1016790A-injected mice treated with BAY 11-7082 displayed distinctly reduced cytosolic protein levels of p-p65 and nuclear protein levels of p65 and p50 in the hippocampus (Fig. 9B). We also found that BAY 11-7082 administration reduced the protein levels of c-IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF in control mice (Fig. 9C). Compared with the vehicle-treated GSK1016790A-injected mice, BAY 11-7082 application significantly reduced the protein levels of c-IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF in the hippocampus in GSK1016790A-injected mice (Fig. 9D). These results indicated that the activation of TRPV4 may increase inflammatory cytokine production through enhancing HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB pathway signaling.

Fig. 9.

BAY 11–7082, an NF-κB signaling pathway inhibitor, reduces the hippocampal protein levels of NF-κB and inflammatory cytokines in GSK1016790A-injected mice. A The hippocampal protein levels of p-p65/p65 (Mann–Whitney U test, P < 0.001), p65 (Mann–Whitney U test, P < 0.001) and p50 (Mann–Whitney U test, P < 0.001) in control and BAY 11-7082-injected mice; △△△P < 0.001 versus control (control 7, see Supplementary Methods and Materials). B The application of BAY 11-7082 markedly reduced the hippocampal protein levels of p-p65/p65 (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001), p65 (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001), and p50 (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) in GSK1016790A-injected mice; $$$P < 0.001 versus control (control 8, see Supplementary Methods and Materials), ▼▼▼P < 0.001 versus GSK1016790A (GSK1016790A+vehicle-4, see Supplementary Methods and Materials). C The hippocampal protein levels of c-IL-1β (Mann–Whitney U test, P < 0.001), TNF (Mann–Whitney U test, P < 0.001), and IL-6 (Mann–Whitney U test, P < 0.001) in control and BAY 11-7082-injected mice; △△△P < 0.001 versus control (control 7, see Supplementary Methods and Materials). D The application of BAY 11-7082 markedly reduced the hippocampal protein levels of c-IL-1β (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001), TNF (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001), and IL-6 (Kruskal–Wallis test, P < 0.001) in GSK1016790A-injected mice; $$$P < 0.001 versus control (control 8, see Supplementary Methods and Materials), ▼▼▼P < 0.001 versus GSK1016790A+vehicle (GSK1016790A+vehicle-4, see Supplementary Methods and Materials). Horizontal lines represented the medians, the boxes in plots represented interquartile range (25th–75th percentile) of each distribution, and the error bars represented the maximum and minimum values

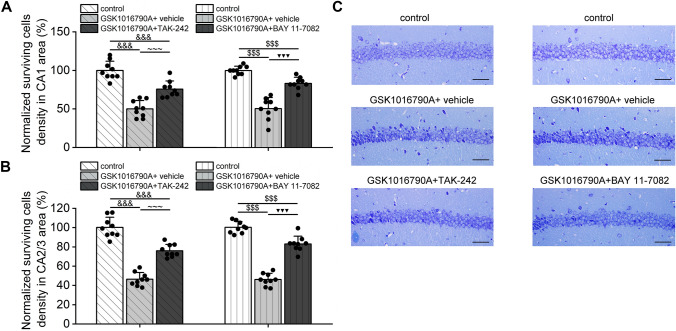

TAK-242 or BAY 11–7082 Administration Alleviates Hippocampal Neuronal Injury in GSK1016790A-Injected Mice

The activation of TRPV4 has been shown to induce neurotoxicity. In this study, fewer surviving pyramidal neurons were found in the hippocampal CA1 and CA2/3 regions of GSK1016790A-injected mice than in those of untreated animals, in line with previous report (Jie et al. 2016). The administration of either TAK-242 or BAY 11-7082 did not change the number of surviving hippocampal CA1 or CA2/3 pyramidal neurons in control mice (Fig. 10); however, compared with vehicle-treated GSK1016790A-injected mice, a greater number of hippocampal pyramidal neurons were found to survive in mice co-injected with GSK1016790A and TAK-242 or BAY 11-7082. This result indicated that HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling is likely to be involved in TRPV4 activation-induced neuronal injury (Fig. 11).

Fig. 10.

GSK1016790A, but not TAK-242 or BAY 11-7082, decreases the hippocampal neuronal survival in control mice. The numbers of surviving pyramidal cells in the CA1 (A and C) and CA2/3 (B) regions in GSK1016790A- (independent samples t test, CA1: t = 13.49, P < 0.001; CA2/3: t = 15.38, P < 0.001), TAK-242- (independent samples t test, CA1: t = 0.62, P = 0.54; CA2/3: t = 1.63, P = 0.12), and BAY 11–7082-injected mice (independent samples t test, CA1: t = 0.30, P = 0.77; CA2/3: t = − 0.07, P = 0.95). × 400, Scale bar = 100 μM, ###P < 0.001 versus control (control 4, see Supplementary Methods and Materials)

Fig. 11.

TAK-242 and BAY 11-7082 increase the hippocampal neuronal survival in GSK1016790A-injected mice. The co-administration of TAK-242 or BAY 11-7082 in GSK1016790A-mice markedly increased the numbers of surviving pyramidal cells in the CA1 (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test, TAK-242: F2,24 = 45.22, P < 0.001; BAY 11-7082: F2,24 = 57.71, P < 0.001) (A and C) and CA2/3 regions (one-way ANOVA followed by Bonferroni’s post hoc test, TAK-242: F2,24 = 96.91, P < 0.001; BAY 11-7082: F2,24 = 146.29, P < 0.001) (B) of the hippocampus. × 400, Scale bar = 100 μM, &&&P < 0.001 versus control (control 6, see Supplementary Methods and Materials), ~~~P < 0.001 versus GSK1016790A + vehicle (GSK1016790A + vehicle-3, see Supplementary Methods and Materials), $$$P < 0.001 versus control (control 8, see Supplementary Methods and Materials), ▼▼▼P < 0.001 versus GSK1016790A + vehicle (GSK1016790A + vehicle-4, see Supplementary Methods and Materials)

Discussion

The present study found that the levels of HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway-related proteins increased in mice with PISE and these changes were blocked by a TRPV4 antagonist HC-067047. Application of a TRPV4 agonist GSK1016790A increased the levels of HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB signaling pathway-related proteins in the hippocampus, which was attenuated by a TLR4 antagonist TAK-242. Application of an NF-κB signaling pathway inhibitor BAY 11-7082 reduced the hippocampal protein levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in GSK1016790A-injected mice. GSK1016790A-induced hippocampal neuronal death was attenuated by TAK-242 or BAY 11-7082.

Hippocampal neuronal loss, an important pathological change seen in TLE, leads to structural and functional alterations in hippocampal neural networks, thereby greatly influencing the development of epilepsy (Pitkänen et al. 2002). During epilepsy, the inflammatory response is a major causal factor for neuronal injury. Patients with epilepsy have elevated expression levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines in the cerebrospinal fluid and serum. Moreover, the expression of IL-1β was found to be increased in the brain tissue of epilepsy patients after surgical resection, while seizures were significantly relieved in some patients taking anti-inflammatory drugs (Rizzi et al. 2003; de Vries et al. 2016; Mazdeh et al. 2018).

When activated, the NF-κB transcription factor is a key inducer of inflammatory cytokine-related gene expression and is a critical regulator of the inflammatory response (Kopitar-Jerala, 2015). In the cytoplasm, IκB inhibitory subunits are complexed with p50/p65 heterodimers, and cover the nuclear localization sequence of NF-κB, thereby preventing its translocation into the nucleus under physiological conditions. The activity of IκB is regulated by IκK. When IκK is activated, it phosphorylates IκB, which then disassociates from p50/p65 heterodimers, leading to NF-κB activation and its subsequent translocation into the nucleus, where it induces immune- and inflammation-related gene expression (Suzuki et al. 2011). HMGB1 binds to TLR4, thereby activating NF-κB (Ibrahim et al. 2013; Lu et al. 2014).The expression of HMGB1 and TLR4 is significantly increased and the levels of inflammatory cytokines are elevated in the hippocampal tissue of rats with KA- and pentylenetetrazol-induced epilepsy (Kaya et al. 2021). Inhibiting the HMGB1/TLR4 pathway can alleviate the inflammatory response and nerve injury after seizures (Zhang et al. 2018). IκKβ knockout in microglia can effectively inhibit the KA-induced production of inflammatory cytokines in the hippocampus (Cho et al. 2008). Here, the hippocampal protein levels of HMGB1 and TLR4 were found to be increased in mice with PISE (Fig. 1A, B). The cytosolic protein levels of p-IκK, p-IκB, and p-p65, as well as the nuclear protein levels of p65 and p50, were also noticeably increased following the onset of PISE (Figs. 1C, D and 2). These results indicated that the HMGB1/TLR4/IκK/IκB/NF-κB pathway is activated in mice with PISE, which leads to inflammatory cytokine production.

Studies on epithelial cells of the colon, esophagus, and urethra; endothelial cells of blood vessels, and keratinocytes of the skin have shown that TRPV4 activation can promote the expression and release of IL-1β, IL-6, and other pro-inflammatory cytokines and also induce inflammatory responses (Dutta et al. 2020). The TRPV4 antagonist GSK2193874 was reported to attenuate lipopolysaccharide-induced IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF production in pulmonary macrophages (Li et al. 2019). Additionally, small interfering RNA-mediated inhibition of TRPV4 can reduce IL-1β and TNF production in cultured glial cells (Liu et al. 2010). TRPV4 is implicated in the pathogenesis of epilepsy and blocking TRPV4 can reduce the levels of inflammatory cytokines following the onset of PISE (Men et al. 2019; Wang et al. 2019). In this study, we found that the application of the TRPV4 antagonist HC-067047 markedly suppressed HMGB1 and TLR4 protein levels in the hippocampus in mice with PISE (Fig. 3B, D). Additionally, following PISE onset, HC-067047 treatment reduced the cytosolic protein levels of p-IκK, p-IκB, and p-p65, as well as the nuclear protein levels of p65 and p50 (Figs. 3F, H and 4B, D, F). These results indicated that blocking TRPV4 can inhibit the HMGB1/TLR4/IκK/IκB/NF-κB pathway in mice with PISE.

In this study, we found that application of the TRPV4 agonist GSK1016790A increased the protein levels of p-p65 in the cytoplasm and those of p65 and p50 in the nucleus of hippocampal cells, suggesting that the activation of TRPV4 promotes NF-κB activation and nuclear translocation (Fig. 6). We also found that hippocampal HMGB1 and TLR4 protein levels were higher in GSK1016790A-injected mice than in control animals (Fig. 5A, B). Furthermore, the cytosolic protein levels of p-IκK and p-IκB were increased by GSK1016790A treatment (Fig. 5C, D), an effect that was markedly attenuated by the administration of TAK-242, a TLR4 antagonist (Fig. 7B, D). Moreover, in GSK1016790A-injected mice, co-treatment with TAK-242 or the NF-κB signaling pathway inhibitor BAY 11-7082 reduced the cytosolic protein level of p-p65 and the nuclear protein levels of p65 and p50 (Figs. 7F, H, J and 9B). These results suggested that activated TRPV4 may enhance HMGB1/TLR4/NF-κB pathway activity. In this study, in GSK1016790A-injected mice, co-treatment with either TAK-242 or BAY 11-7082 effectively reduced the hippocampal levels of c-IL-1β, TNF, and IL-6, and led to a notable increase in the number of surviving neurons in the hippocampus (Figs. 8B, D, F, 9D and 11). These observations indicated that the activation of TRPV4 may enhance inflammatory responses and lead to neuronal injury through enhancing HMGB1/TLR4/IκK/IκB/NF-κB pathway activity.

Activated TRPV4 induces neurotoxicity, which is subsequently involved in the neuronal damage in cerebral ischemia–reperfusion injury, Alzheimer disease, Parkinson disease, and epilepsy (Zhang et al. 2013; Liu et al. 2020; Tanaka et al. 2020).The activation of TRPV4 may facilitate glutamate excitotoxicity by enhancing the function of the N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) glutamate receptor and/or promoting the release of presynaptic glutamate (Li et al. 2013; Shibasaki et al. 2014). Enhanced oxidative stress is also reported to be involved in TRPV4 agonist-mediated neuronal injury (Bai and Lipski 2014; Hong et al. 2016). In addition, TRPV4 activation-associated cell damage may be related to the activation of apoptosis and the promotion of endoplasmic reticulum stress (Jie et al. 2015; Shen et al. 2019; Liu et al. 2020). Although the mechanism underlying TRPV4-induced neurotoxicity is not completely clear, TRPV4 nevertheless represents a promising target for promoting neuroprotection in disorders of the central nervous system.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contributions

LC designed the study and wrote the manuscript. DA, XQ, KL and WX performed the experiments. YW and XC did the data analysis. SS, CW and YD helped to revise the manuscript. All authors approved the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81971274 and 81571270) to Lei Chen; National Natural Science Foundation of China (82170326 and 81770328) to Yimei Du, Foundation of Nanjing Health Committee (YKK19101) to Chunfeng Wu and Nanjing Medical University Science and Technology Development Project (NMUB20210003) to Dong An.

Data Availability

All mentioned data are presented in this published article or the supplementary information or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Ethical Approval

This study was approved by the Ethics Committee of Nanjing Medical University (No. IACUC2009007) and all animal experiments were performed in accordance with the Guidelines for Laboratory Animal Research set by Nanjing Medical University.

Consent for Publish

All authors consent to publish the article.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Yimei Du, Email: yimeidu@mail.hust.edu.cn.

Lei Chen, Email: chenl@njmu.edu.cn.

References

- Bai JZ, Lipski J (2014) Involvement of TRPV4 channels in Aβ(40)-induced hippocampal cell death and astrocytic Ca(2+) signalling. Neurotoxicology 41:64–72. 10.1016/j.neuro.2014.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi ME, Crippa MP, Manfredi AA, Mezzapelle R, Rovere Querini P, Venereau E (2017) High-mobility group box 1 protein orchestrates responses to tissue damage via inflammation, innate and adaptive immunity, and tissue repair. Immunol Rev 280(1):74–82. 10.1111/imr.12601 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Yang M, Sun F, Liang C, Wei Y, Wang L, Yue J, Chen B, Li S, Liu S, Yang H (2016a) Expression and cellular distribution of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 in cortical tubers of the tuberous sclerosis complex. Brain Res 1636:183–192. 10.1016/j.brainres.2016a.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Sun FJ, Wei YJ, Wang LK, Zang ZL, Chen B, Li S, Liu SY, Yang H (2016b) Increased expression of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 in cortical lesions of patients with focal cortical dysplasia. CNS Neurosci Ther 22(4):280–290. 10.1111/cns.12494 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho IH, Hong J, Suh EC, Kim JH, Lee H, Lee JE, Lee S, Kim CH, Kim DW, Jo EK, Lee KE, Karin M, Lee SJ (2008) Role of microglial IKKbeta in kainic acid-induced hippocampal neuronal cell death. Brain 131(Pt 11):3019–3033. 10.1093/brain/awn230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Vries EE, van den Munckhof B, Braun KP, van Royen-Kerkhof A, de Jager W, Jansen FE (2016) Inflammatory mediators in human epilepsy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Neurosci Biobehav Rev 63:177–190. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2016.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta B, Arya RK, Goswami R, Alharbi MO, Sharma S, Rahaman SO (2020) Role of macrophage TRPV4 in inflammation. Lab Invest 100(2):178–185. 10.1038/s41374-019-0334-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher RS, van Emde BW, Blume W, Elger C, Genton P, Lee P, Engel J (2005) Epileptic seizures and epilepsy: definitions proposed by the international league against epilepsy (Ilae) and the International Bureau for Epilepsy (Ibe). Epilepsia 46(4):470–472. 10.1111/j.0013-9580.2005.66104.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong J, Sha S, Zhou L, Wang C, Yin J, Chen L (2015) Sigma-1 receptor deficiency reduces MPTP-induced parkinsonism and death of dopaminergic neurons. Cell Death Dis 6:e1832. 10.1038/cddis.2015.194 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong Z, Tian Y, Yuan Y, Qi M, Li Y, Du Y, Chen L, Chen L (2016) Enhanced oxidative stress is responsible for TRPV4-induced neurotoxicity. Front Cell Neurosci 10:232. 10.3389/fncel.2016.00232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua F, Tang H, Wang J, Prunty MC, Hua X, Sayeed I, Stein DG (2015) Tak-242, an antagonist for toll-like receptor 4, protects against acute cerebral ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab 35(4):536–542. 10.1038/jcbfm.2014.240 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunt RF, Hortopan GA, Gillespie A, Baraban SC (2012) A novel zebrafish model of hyperthermia-induced seizures reveals a role for Trpv4 channels and Nmda-type glutamate receptors. Exp Neurol 237(1):199–206. 10.1016/j.expneurol.2012.06.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ibrahim ZA, Armour CL, Phipps S, Sukkar MB (2013) RAGE and TLRs: relatives, friends or neighbours? Mol Immunol 56(4):739–744. 10.1016/j.molimm.2013.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jie P, Hong Z, Tian Y, Li Y, Lin L, Zhou L, Du Y, Chen L, Chen L (2015) Activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 induces apoptosis in hippocampus through downregulating PI3K/Akt and upregulating p38 MAPK signaling pathways. Cell Death Dis 6(6):e1775. 10.1038/cddis.2015.146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jie P, Hong Z, Tian Y, Li Y, Lin L, Zhou L, Du Y, Chen L, Chen L (2016) Activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 is involved in neuronal injury in middle cerebral artery occlusion in mice. Mol Neurobiol 53:8–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaya MA, Erin N, Bozkurt O, Erkek N, Duman O, Haspolat S (2021) Changes of HMGB-1 and sTLR4 levels in cerebrospinal fluid of patients with febrile seizures. Epilepsy Res 169:106516. 10.1016/j.eplepsyres.2020.106516 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kopitar-Jerala N (2015) Innate immune response in brain, NF-kappa B signaling and cystatins. Front Mol Neurosci 8:73. 10.3389/fnmol.2015.00073 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar H, Lee SH, Kim KT, Zeng X, Han I (2018) TRPV4: a sensor for homeostasis and pathological events in the CNS. Mol Neurobiol 55:8695–8708. 10.1007/s12035-018-0998-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Qu W, Zhou L, Lu Z, Jie P, Chen L, Chen L (2013) Activation of transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 increases NMDA-activated current in hippocampal pyramidal neurons. Front Cell Neurosci 7:17. 10.3389/fncel.2013.00017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li M, Fang XZ, Zheng YF, Xie YB, Ma XD, Liu XT, Xia Y, Shao DH (2019) Transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 is a critical mediator in lps mediated inflammation by mediating calcineurin/NFATc3 signaling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 513(4):1005–1012. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2019.04.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu TT, Bi HS, Lv SY, Wang XR, Yue SW (2010) Inhibition of the expression and function of TRPV4 by RNA interference in dorsal root ganglion. Neurol Res 32(5):466–471. 10.1179/174313209X408945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Liu J, Wen X, Bai L, Shao R, Bai J (2020) TRPV4 contributes to ER stress: relation to apoptosis in the MPP(+)-induced cell model of Parkinson’s disease. Life Sci 261:118461. 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu B, Antoine DJ, Kwan K, Lundbäck P, Wähämaa H, Schierbeck H, Robinson M, Van Zoelen MA, Yang H, Li J, Erlandsson-Harris H, Chavan SS, Wang H, Andersson U, Tracey KJ (2014) JAK/STAT1 signaling promotes HMGB1 hyperacetylation and nuclear translocation. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 111(8):3068–3073. 10.1073/pnas.1316925111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mazdeh M, Omrani MD, Sayad A, Komaki A, Arsang-Jang S, Taheri M, Ghafouri-Fard S (2018) Expression analysis of cytokine coding genes in epileptic patients. Cytokine 110:284–287. 10.1016/j.cyto.2018.01.017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Men C, Wang Z, Zhou L, Qi M, An D, Xu W, Zhan Y, Chen L (2019) Transient receptor potential Vanilloid 4 is involved in the upregulation of connexin expression following pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus in mice. Brain Res Bull 152:128–133. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2019.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miyamoto R, Ito T, Nomura S, Amakawa R, Amuro H, Katashiba Y, Ogata M, Murakami N, Shimamoto K, Yamazaki C, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Fukuhara S (2010) Inhibitor of IkappaB kinase activity, BAY 11–7082, interferes with interferon regulatory factor 7 nuclear translocation and type I interferon production by plasmacytoid dendritic cells. Arthritis Res Ther 12(3):R87. 10.1186/ar3014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nilius B, Voets T (2013) The puzzle of Trpv4 channelopathies. EMBO Rep 14(2):152–163. 10.1038/embor.2012.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okada Y, Shirai K, Miyajima M, Reinach PS, Yamanaka O, Sumioka T, Kokado M, Tomoyose K, Saika S (2016) Loss of Trpv4 function suppresses inflammatory fibrosis induced by alkali-burning mouse corneas. PLoS ONE 11(12):e0167200. 10.1371/journal.pone.0167200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitkänen A, Nissinen J, Nairismägi J, Lukasiuk K, Gröhn OH, Miettinen R, Kauppinen R (2002) Progression of neuronal damage after status epilepticus and during spontaneous seizures in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy. Prog Brain Res 135:67–83. 10.1016/s0079-6123(02)35008-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Racine RJ (1972) Modification of seizure activity by electrical stimulation: II. Motor seizure. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol 32:281–294. 10.1016/0013-4694(72)90177-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzi M, Perego C, Aliprandi M, Richichi C, Ravizza T, Colella D, Velískŏvá J, Moshé SL, De Simoni MG, Vezzani A (2003) Glia activation and cytokine increase in rat hippocampus by kainic acid-induced status epilepticus during postnatal development. Neurobiol Dis 14(3):494–503. 10.1016/j.nbd.2003.08.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenbaum T, Benítez-Angeles M, Sánchez-Hernández R, Morales-Lázaro SL, Hiriart M, Morales-Buenrostro LE, Torres-Quiroz F (2020) TRPV4: a physio and pathophysiologically significant ion channel. Int J Mol Sci 21(11):3837. 10.3390/ijms21113837 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen J, Tu L, Chen D, Tan T, Wang Y, Wang S (2019) TRPV4 channels stimulate Ca(2+)-induced Ca(2+) release in mouse neurons and trigger endoplasmic reticulum stress after intracerebral hemorrhage. Brain Res Bull 146:143–152. 10.1016/j.brainresbull.2018.11.024 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki K, Ikenaka K, Tamalu F, Tominaga M, Ishizaki Y (2014) A novel subtype of astrocytes expressing TRPV4 (transient receptor potential vanilloid 4) regulates neuronal excitability via release of gliotransmitters. J Biol Chem 289:14470–14480. 10.1074/jbc.M114.557132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibasaki K, Yamada K, Miwa H, Yanagawa Y, Suzuki M, Tominaga M, Ishizaki Y (2020) Temperature elevation in epileptogenic foci exacerbates epileptic discharge through Trpv4 activation. Lab Invest 100(2):274–284. 10.1038/s41374-019-0335-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki J, Ogawa M, Muto S, Itai A, Isobe M, Hirata Y, Nagai R (2011) Novel IkB kinase inhibitors for treatment of nuclear factor-kB-related diseases. Expert Opin Investig Drugs 20(3):395–405. 10.1517/13543784.2011.559162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka K, Matsumoto S, Yamada T, Yamasaki R, Suzuki M, Kido MA, Kira JI (2020) Reduced post-ischemic brain injury in transient receptor potential vanilloid 4 knockout mice. Front Neurosci 14:453. 10.3389/fnins.2020.00453 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toft-Bertelsen TL, MacAulay N (2021) Trping to the point of clarity: understanding the function of the complex Trpv4 ion channel. Cells 10(1):165. 10.3390/cells10010165 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vergnolle N (2014) Trpv4: new therapeutic target for inflammatory bowel diseases. Biochem Pharmacol 89(2):157–161. 10.1016/j.bcp.2014.01.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vezzani A, Balosso S, Ravizza T (2008) The role of cytokines in the pathophysiology of epilepsy. Brain Behav Immun 22(6):797–803. 10.1016/j.bbi.2008.03.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang W, Wu J, Dai X, Ma G, Yang B, Wang T, Yuan C, Ding D, Hong Z, Kwan P, Bell GS, Prilipko LL, de Boer HM, Sander JW (2008) Global campaign against epilepsy: assessment of a demonstration project in rural China. Bull World Health Organ 86(12):964–969. 10.2471/blt.07.047050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J, Wang XW, Zhang Y, Yin CP, Yue SW (2015) Ca(2+) influx mediates the Trpv4-no pathway in neuropathic hyperalgesia following chronic compression of the dorsal root ganglion. Neurosci Lett 588:159–165. 10.1016/j.neulet.2015.01.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z, Zhou L, An D, Xu W, Wu C, Sha S, Li Y, Zhu Y, Chen A, Du Y, Chen L, Chen L (2019) Trpv4-induced inflammatory response is involved in neuronal death in pilocarpine model of temporal lobe epilepsy in mice. Cell Death Dis 10(6):386. 10.1038/s41419-019-1612-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner DL, Merkhofer RM, Ober C, Kujoth GC, Niu M, Keller NP, Gern JE, Brockman-Schneider RA, Evans MD, Jackson DJ, Warner T, Jarjour NN, Esnault SJ, Feldman MB, Freeman M, Mou H, Vyas JM, Klein BS (2020) Club cell Trpv4 serves as a damage sensor driving lung allergic inflammation. Cell Host Microbe 27(4):614-628.e6. 10.1016/j.chom.2020.02.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang H, Wang H, Andersson U (2020) Targeting inflammation driven by HMGB1. Front Immunol 11:484. 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00484 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L, Papadopoulos P, Hamel E (2013) Endothelial TRPV4 channels mediate dilation of cerebral arteries: impairment and recovery in cerebrovascular pathologies related to Alzheimer’s disease. Br J Pharmacol 170(3):661–670. 10.1111/bph.12315 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang HL, Lin YH, Qu Y, Chen Q (2018) The effect of miR-146a gene silencing on drug-resistance and expression of protein of P-gp and MRP1 in epilepsy. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 22(8):2372–2379. 10.26355/eurrev_201804_14829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J, Wang Y, Xu C, Liu K, Wang Y, Chen L, Wu X, Gao F, Guo Y, Zhu J, Wang S, Nishibori M, Chen Z (2017) Therapeutic potential of an anti-high mobility group box-1 monoclonal antibody in epilepsy. Brain Behav Immun 64:308–319. 10.1016/j.bbi.2017.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All mentioned data are presented in this published article or the supplementary information or are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.