Abstract

Background:

On Saturday, October 7th, approximately 3000 Hamas-led terrorists infiltrated Israel’s southern border and attacked civilians and soldiers. Terrorists murdered close to 1200 people, abducted hundreds, and injured thousands. This surprise attack involved an unprecedented number of casualties. This article describes the injuries and outcomes of the hospitalized casualties.

Methods:

Hospitalized trauma casualties with an injury date of October 7 to 8, 2023, and with ICD9 E-codes E979 and E990 through E999, were extracted from the Israel National Trauma Registry. Demographic, injury, and hospital resource-use data were analyzed.

Results:

A total of 630 hospitalized casualties (277 civilians and 353 soldiers) suffered from gunshot wounds (90%), explosion-related wounds (19%), and multiple injury mechanisms (16%). The median age for civilians was 33 years (ages <1–88) and 21 years for soldiers. The most frequently injured body regions were lower (49%) and upper (42%) extremities, abdominal (28%), and thoracic (23%) injuries. Four hundred thirty-one (68%) patients underwent surgery, of which 240 within 12 hours. Over half of the severe and critical (Injury Severity Score 16+) casualties were discharged to a rehabilitation center. In-hospital mortality rate was 2.5%.

Conclusion:

Israel’s hospitals faced many challenges following the mega mass casualty incident, including the absorption, diagnosis, treatment, and rehabilitation of a massive number of casualties. Hospitals needed to immediately repurpose to provide additional imaging equipment and operating rooms. Additionally, the huge demand for rehabilitation resources necessitated immediate reorganization and transformation of existing medical facilities to accommodate the many casualties requiring rehabilitation. The injury details and outcomes from this mega mass casualty incident provide important information for planning and preparedness at local, regional, and national levels.

Keywords: injury, hospitalizations, mass casualty incident, terror attack, trauma, trauma registry

Introduction

Terror attacks against innocent civilians are a worldwide problem that often result in mass casualty incidents (MCI) involving all ages, diverse injuries, and varying levels of injury severity. MCIs in general, and large-scale terror MCIs in particular, pose significant challenges to medical teams and require adequate preparedness and prompt response to effectively manage the immediate and long-term healthcare needs of the wounded.

Some of the largest recent terror attacks in the Western world include: New York City (2001) on 9/11 which resulted in nearly 3000 deaths and thousands of injuries; Madrid (2004) train bombings which resulted in 191 deaths and over 1,800 injuries; London (2005) where coordinated suicide bombers on the public transportation system resulted in 52 deaths and more than 700 injured; and Paris (2015), where Islamic State of Iraq and Syria militants targeted several locations resulting in 130 deaths and over 350 casualties.1–4

The October 7th terror attack in Israel was the deadliest by the number of fatalities per capita for at least the last 50 years.5 On that Saturday, approximately 3000 Hamas-led terrorists infiltrated Israel’s southern border with Gaza and attacked civilians of all ages and soldiers in their homes, at an outdoor music festival, and on military bases. Hamas terrorists invaded 20 communities and several Israel Defense Forces bases, using assault rifles and explosives which killed and injured hundreds of civilians and soldiers. The music festival, which had approximately 4000 people in attendance, was also overrun by terrorists, resulting in 364 murders (approximately 30% of the total MCI deaths), 40 taken hostage, and hundreds injured.6–8

All said, the Hamas terrorists murdered close to 1200 people by firearms, explosives, decapitation, mutilation, and incineration. Hundreds of others were abducted and thousands more were injured. Israel’s National Center of Forensic Medicine had to identify almost 1200 deaths in a single day when they usually handle about 2000 cases a year.9 On October 7th and 8th, approximately 2000 casualties arrived at various emergency medicine departments (ED), especially at the Soroka Medical Center (level-I trauma center) and Barzilai Medical Center (level-II trauma center) which serve the Negev and Gaza Strip adjacent regions of southern Israel.10 Approximately 1 million people reside in this southern part of Israel, out of a national population of 9.8 million.11

While trauma centers in Israel are prepared for treating casualties in MCIs including terror incidents, the surprise attack on October 7th involved an unprecedented number of casualties resulting in a “mega MCI.” This article aims to describe the injuries of hospitalized casualties, the resources needed to diagnose and treat them, and their outcomes. Our description of the Israeli experience with a mega MCI may help other countries adequately prepare for their own trauma disasters.

METHODS

Data Source

The Israel National Trauma Registry (INTR), which aggregates data from all 7 level-I trauma centers (TCs) and 16 level-II TCs in Israel, was the data source for this study. The INTR includes all trauma patients with an International Classification of Disease-Ninth Revision-Clinical Modification (ICD9-CM) diagnosis code 800–989.9, who were received by an emergency department and were either hospitalized, died in the ED, or transferred to or from another hospital. The registry does not include casualties who died at the scene or en route to the hospital, or who were poisoned, suffocated, or drowned, or (under normal conditions; see below) hospitalized >72 hours after the traumatic incident. Under the guidance of a trauma unit director or trauma coordinator, trained trauma registrars at each TC entered the data into an electronic file. These files were then transferred to the INTR, where data quality checks were conducted. The data did not contain the names of the casualties or their national identification numbers. This study was approved by the Sheba Medical Center Institutional Review Board (IRB) (SMC 5138–18).

Study Population

For the purposes of this study, only hospitalized casualties with an injury date of October 7, 2023 or October 8, 2023, and with ICD9 E-codes E979 and E990 through E999 (which are terror and war-related injuries) were included. The data collection for this study ended on December 24, 2023.

Since many roads and towns were infiltrated by terrorists, it often took several hours to arrive at a hospital. An exception to the usual INTR inclusion criteria was thus made, and trauma registrars were instructed to include wounded from the October 7th and 8th attacks even if hospitalized more than 72 hours after the injury occurrence. Only 2 casualties met this relaxed criterion, arriving at the hospital 4 and 5 days following their injuries.

Only areas infiltrated by terrorists in the Negev and Gaza Strip adjacent regions of southern Israel were included. Casualties in other areas of the country that were injured on October 7th and 8th by rocket fire from Gaza were not included (n = 97).

The casualties are divided into two groups: (1) civilians, which also includes foreign workers, police officers, firefighters, and emergency medical services members, and (2) soldiers, both active duty and activated reservists.

Study Variables

The patients’ demographic characteristics, nature of injury, management, and post-treatment outcomes were obtained from the INTR. The demographic variables included age, gender, and ethnicity (Jews/non-Jews). Age takes into consideration soldiers in mandatory service (generally ages 18–22 years) and reserve duty (generally >22 years); thus, age is categorized as: 0–17, 18–22, 23–29, 30–64, and ≥65.

Injuries were characterized by the mechanism of injury (explosion, gunshot, or other) and categorized as penetrating, blunt, burn, or combined (ie, more than 1 mechanism). Abbreviated Injury Scale (AIS) codes were used to identify injured body regions (head, face, neck, thorax, abdomen, spine, upper extremity, lower extremity, and external). A seriously injured body region was defined as an AIS severity code of ≥3. The INTR software calculates the Injury Severity Score (ISS) based on the reported AIS codes. The ISS was categorized as 1–8 (minor), 9–14 (moderate), 16–24 (severe), and 25–75 (critical). Note that the ISS cannot be 15.12–14 Injury severity is reported here using the ISS and the initial Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) in the ED.

Surgeries were categorized according to ICD-CM procedure codes into neurosurgical, thoracic, abdominal, spinal, orthopedic, ophthalmologic, otorhinolaryngologic, and skin and subcutaneous procedures.

Hospital resource utilization variables included: treatment in a trauma resuscitation bay, admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) (yes/no), total number of surgical interventions during admission, and total length of stay (LOS). The outcome was defined by discharge destination which included home or place of temporary residence (residents of many southern towns and the Gaza Strip adjacent communities have been displaced to temporary housing), rehabilitation facilities, or death.

Data for casualties who were admitted more than once during the study period were used as follows: demographics, mechanism of injury, GCS, and other ED data from the first admission; procedures performed in the operating room, LOS, and ICU admissions were cumulative across the admissions; injured body regions, AIS codes, and discharge destination were from the last admission. This effectively merges repeated hospital admissions related to the October 7th attack, which occurred during the study period (October 7–December 24, 2023), into 1 consecutive stay.

The transfer of patients to another acute care hospital did not disrupt INTR data collection. All available data from hospital stays, irrespective of hospital or transfer status, were included in this analysis.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Descriptive data were analyzed using the χ2 test. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

RESULTS

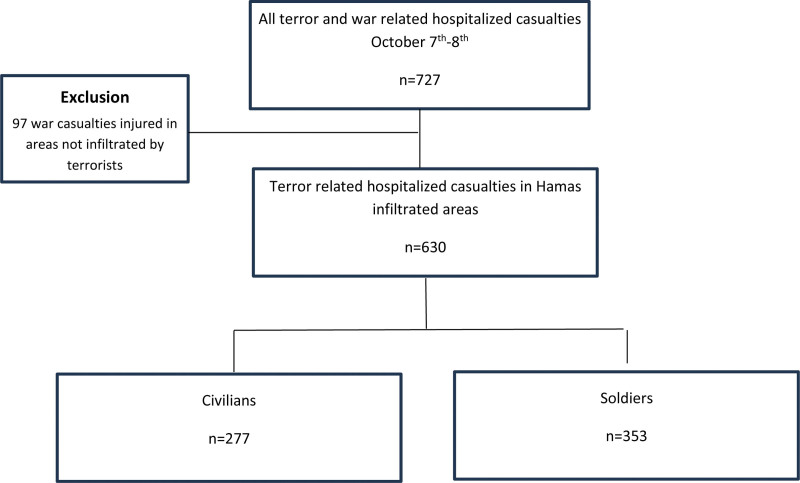

Approximately 2000 casualties arrived at the various EDs on October 7th and 8th, of whom 630 were hospitalized. Of these, 44.0% (n = 277) were civilians and 56.0% (n = 353) were soldiers (Fig. 1). The vast majority (n = 575, 91.3%) of casualties (263 civilians and 312 soldiers) were admitted on October 7th, and 60% were hospitalized in Israel’s southern trauma centers.

FIGURE 1.

Study population for hospitalized terror casualties.

Demographic Characteristics

The civilian casualties had a wide range of ages, with the youngest being an infant (younger than 1 year) and the oldest being 88 years old. The median age (interquartile range [IQR]) was 33 years (25–44) for civilians and 21 years (20–24) for soldiers (Table 1). Overall, 7% of the hospitalized casualties were not Jewish, including Israeli citizens, foreign workers, and students (12.4% [n = 34] of the civilians and 2.3% [n = 8] of the soldiers were not Jewish).

TABLE 1.

Demographics and Mechanisms of Injury Among Hospitalized Terror Victims, October 7–8, 2023

| Civilians n = 277 |

Soldiers n = 353 |

Total n = 630 |

P * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Age | ||||

| Median, years (IQR) | 33 (25–44) | 21 (20–24) | 24 (21–35) | <0.001 |

| Age group | <0.001 | |||

| 0–17 | 17 (6.2) | 0 (0.0) | 17 (2.7) | |

| 18–22 | 25 (9.0) | 223 (63.2) | 248 (39.4) | |

| 23–29 | 71 (25.6) | 71 (20.1) | 142 (22.5) | |

| 30–64 | 148 (53.4) | 59 (16.7) | 207 (32.9) | |

| 65+ | 16 (5.8) | 0 (0.0) | 16 (2.5) | |

| Gender | <0.001 | |||

| Male | 222 (80.1) | 327 (92.6) | 549 (87.1) | |

| Female | 55 (19.9) | 26 (7.4) | 81 (12.9) | |

| Ethnicity† | <0.001 | |||

| Jews | 240 (87.6) | 345 (97.7) | 585 (92.8) | |

| Non-Jews | 34 (12.4) | 8 (2.3) | 42 (6.7) | |

| Type of injury | ||||

| Penetrating | 256 (92.4) | 343 (97.2) | 599 (95.1) | 0.019 |

| Mechanism of injury‡ | ||||

| Gunshot | 254 (91.7) | 335 (94.9) | 589 (93.5) | 0.106 |

| Explosion | 54 (19.5) | 67 (19.0) | 121 (19.2) | 0.871 |

| Other§ | 16 (5.8) | 3 (0.9) | 19 (3.0) | 0.001 |

| >1 mechanism∥ | 47 (17.0) | 51 (14.5) | 98 (15.6) | 0.559 |

P-values are for comparing civilians with soldiers.

Missing data in 3 civilian casualties.

Total mechanism of injury >100% since some casualties were injured by more than one mechanism.

Other includes: stabbings, motor vehicle crash, falls, fights, and cuts.

Number (percentage) of casualties who endured more than one mechanism of injury.

Mechanism of Injury

More than 90% of casualties suffered from penetrating injuries. The primary mechanism of injury was firearms; over 90% of both civilians and soldiers suffered from gunshot wounds. Nineteen percent of the casualties sustained explosion-related wounds. Twelve civilians (4.4%) and 4 soldiers (1.1%) sustained burns. Multiple injury mechanisms were reported in 98 (15.6%) of all the casualties (Table 1).

Body Region and Injury Severity

Among the hospitalized casualties, the most frequently injured body regions were the lower (n = 308, 48.9%) and upper (n = 263, 41.8%) extremities, followed by abdominal (n = 179, 28.4%) and thoracic (n = 146, 23.2%) injuries. Head injuries were reported in 74 patients (11.8%). There were no significant differences in the injured body regions between civilians and soldiers (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Injury Severity and Injured Body Region of Hospitalized Terror Victims, October 7–8th, 2023

| Civilians n = 277 |

Soldiers n = 353 |

Total n = 630 |

P * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| No. body regions injured | 0.759 | |||

| 1 | 130 (46.9) | 170 (48.2) | 300 (47.6) | |

| 2+ | 147 (53.1) | 183 (51.8) | 330 (52.4) | |

| Body region† (any severity) | ||||

| Head | 27 (9.7) | 47 (13.3) | 74 (11.8) | 0.168 |

| Face | 40 (14.4) | 45 (12.7) | 85 (13.5) | 0.537 |

| Neck | 16 (5.8) | 27 (7.7) | 43 (6.8) | 0.355 |

| Thorax | 64 (23.1) | 82 (23.2) | 146 (23.2) | 0.971 |

| Abdomen | 85 (30.7) | 94 (26.6) | 179 (28.4) | 0.262 |

| Spine | 14 (5.1) | 19 (5.4) | 33 (5.2) | 0.854 |

| Upper Extremities | 105 (37.9) | 158 (44.7) | 263 (41.8) | 0.083 |

| Lower Extremities | 136 (49.1) | 172 (48.7) | 308 (48.9) | 0.926 |

| Number of amputees | 0.039 | |||

| Extremities | 6 (2.2) | 9 (2.6) | 15 (2.4) | |

| Fingers | 5 (1.8) | 0 | 5 (0.8) | |

| Injury severity | ||||

| ISS | 0.344 | |||

| Mild (1–8) | 136 (49.1) | 150 (42.5) | 286 (45.4) | |

| Moderate (9–14) | 63 (22.7) | 99 (28.0) | 162 (25.7) | |

| Severe (16–24) | 47 (17.0) | 61 (17.3) | 108 (17.1) | |

| Critical (25+) | 31 (11.2) | 43 (12.2) | 74 (11.8) | |

| GCS (in ER)‡ | 0.889 | |||

| 15 | 211 (89.8) | 279 (90.6) | 490 (90.2) | |

| 14 | 3 (1.3) | 5 (1.6) | 8 (1.5) | |

| 9–13 | 4 (1.7) | 4 (1.3) | 8 (1.5) | |

| 3–8 | 17 (7.2) | 20 (6.5) | 37 (6.8) |

P-values are for comparing civilians with soldiers.

Total body regions >100% since some casualties were injured in more than one body region.

Missing data in 42 civilian casualties and 45 soldiers.

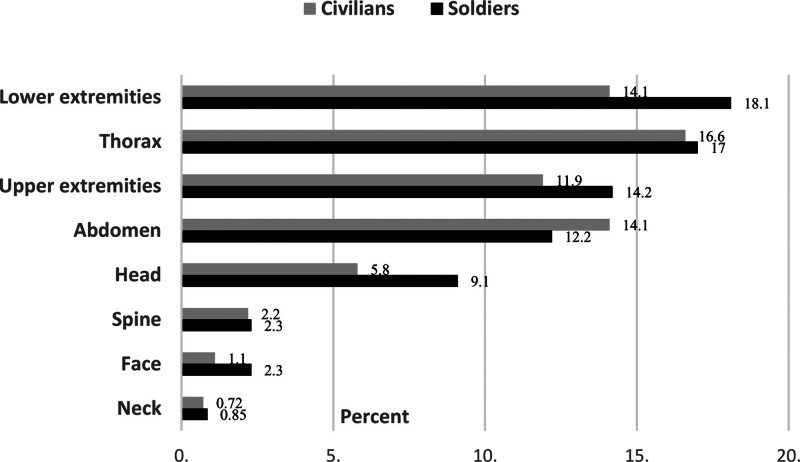

Serious injuries (AIS ≥3) predominantly involved the extremities, thorax, abdomen, and head (Fig. 2). Extremity amputation (not including finger amputation) occurred in 15 (2.4%) casualties (6 civilians [2.2%] and 9 soldiers [2.6%]), and 5 civilians (1.8%) suffered the amputation of finger(s) (Table 2).

FIGURE 2.

Percentage of hospitalized casualties with severely injured body regions (AIS ≥3), by body region, among civilians and soldiers, October 7–8, 2023, n = 630. Serious injuries (AIS ≥3) predominantly involved the extremities, thorax and abdomen. P value: neck P = 0.858; face P = 0.260; spine P = 0.933; head P = 0.122; abdomen P = 0.482; upper extremities P = 0.407; thorax P = 0.896; lower extremities P = 0.172.

Compared to civilians, more soldiers tended to suffer from serious head and lower extremity injuries (AIS ≥3) (Fig. 2). Among civilians, 16 (5.8%) had serious head injuries, whereas among soldiers 32 (9.1%) had serious injuries. Likewise, among civilians, 39 (14.1%) suffered serious lower extremity injuries, whereas among soldiers, 64 (18.1%) suffered serious injuries to the lower extremities (Fig. 2). The frequencies of serious thoracic and abdominal injuries were similar for civilians and soldiers.

ISSs and GCS scores were similar for civilians and soldiers: 182 (28.9%) casualties suffered from severe and critical injuries (ISS ≥16), and 37 (6.8% of 543; missing 87) had a GCS of 3–8 in the ED (Table 2).

Hospital Resource Utilization

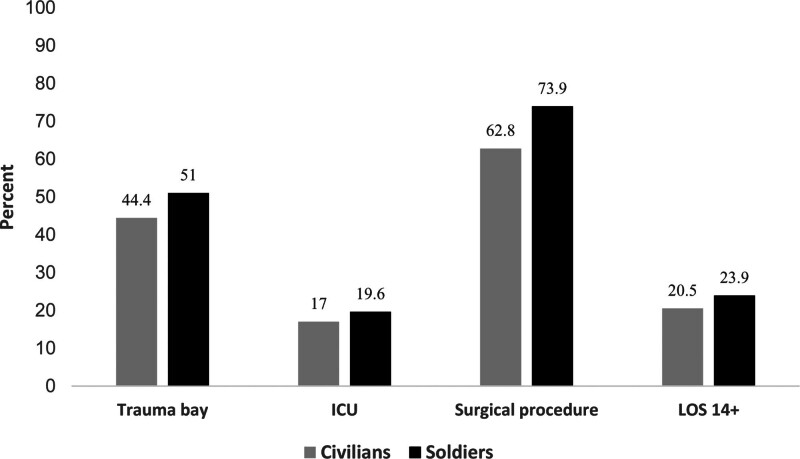

Three hundred and three (48.1%) casualties were triaged for treatment in the trauma resuscitation bay, which included proportionately more soldiers (123 [44.4%] civilians and 180 [51.0%] soldiers) (Fig. 3).

FIGURE 3.

Hospitalization resource utilization for civilians and soldiers, October 7–8, 2023, n = 630. The utilization of hospital resources among both civilians and soldiers was substantial, including the admissions to the trauma bay and ICU, long hospital stays and surgical procedures. P value for Trauma bay = 0.101; ICU = 0.407; surgical procedure = 0.003; LOS ≥14 = 0.334.

From the ED, 158 (25.1%) casualties were transferred directly to the operating room (67 [24.2%] civilians and 91 [25.8%] soldiers), and 35 (5.6%) casualties (17 [6.1%] civilians and 18 [5.1%] soldiers) were transferred directly to the ICU. An additional 111 (17.6%) casualties were transferred from the ED to another hospital (41 [14.8%] civilians and 70 [19.8%] soldiers).

Overall, 116 patients (18.4%) were admitted to the ICU for at least 1 day during their hospital stay (47 [17.0%] civilians and 69 [19.6%] soldiers) (Fig. 3). Over 430 (69%) patients underwent at least 1 surgical procedure, 240 of which were performed within the first 12 h of arrival at the TC. More soldiers underwent at least 1 surgical procedure (62.8% and 73.9% for civilians and soldiers, respectively; P = 0.003) and soldiers were more likely to undergo surgery within the first 12 hours (32.5% and 42.5%, respectively for civilians and soldiers; P = 0.012) (Table 3 and Fig. 3). Most surgical procedures were skin and subcutaneous (n = 259, 41.1%) followed by orthopedic (n = 213, 33.8%). Soldiers tended to undergo more thoracic, orthopedic, and spinal surgeries than did civilians (Table 4).

TABLE 3.

Hospital Resource Utilization of Hospitalized Terror Victims, October 7–8th, 2023

| Civilians n = 277 |

Soldiers n = 353 |

Total n = 630 |

P * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| CT (in ED) | 1365 (49.1) | 194 (54.0) | 330 (52.4) | 0.144 |

| LOS† | 0.014 | |||

| 0–1 | 67 (26.0) | 49 (14.6) | 116 (19.6) | |

| 2–6 | 99 (38.4) | 157 (46.8) | 256 (43.2) | |

| 7–13 | 39 (15.1) | 49 (14.6) | 88 (14.8) | |

| 14–27 | 38 (14.7) | 54 (16.1) | 92 (15.5) | |

| 28+ | 15 (5.8) | 24 (7.2) | 39 (6.5) | |

| Surgical procedure‡ | 0.012 | |||

| >12 hours to surgery | 90 (32.6) | 150 (42.9) | 240 (38.3) | |

| >12 hours to surgery | 83 (30.1) | 108 (30.9) | 191 (30.5) | |

| No surgery | 103 (37.3) | 92 (26.3) | 195 (31.2) | |

| Outcome§ | 0.111 | |||

| Discharge to home/residence | 195 (70.4) | 224 (63.5) | 419 (66.2) | |

| Discharge to rehabilitation ISS 16+ |

61 (22.0) 31 (43.7) |

104 (29.5) 61 (58.7) |

165 (26.2) 92 (52.6) |

|

| In-hospital mortality-Total ISS 25+ |

7 (2.5) 7 (20.6) |

9 (2.6) 7 (17.1) |

16 (2.5) 14 (18.7) |

|

| Hospitalizations admissions | 0.043 | |||

| 1 | 179 (64.6) | 200 (56.7) | 379 (60.2) | |

| 2+ | 98 (35.4) | 153 (43.3) | 251 (39.8) |

P values are for comparing civilians with soldiers.

Missing data in 19 civilian casualties and 20 soldiers.

Missing data in 1 civilian and 3 soldiers.

Missing data in 14 civilians and 16 soldiers.

TABLE 4.

Types of Surgical Procedures Performed Among Hospitalized Terror Victims, October 7–8

| Civilians n = 277 |

Soldiers n = 353 |

Total n = 630 |

P * | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Skin and subcutaneous | 105 (37.9) | 154 (43.6) | 259 (41.1) | 0.148 |

| Orthopedic | 84 (30.3) | 129 (36.5) | 213 (33.8) | 0.102 |

| Abdominal | 41 (14.8) | 54 (15.3) | 95 (15.3) | 0.863 |

| Thoracic | 26 (9.4) | 45 (12.8) | 71 (11.3) | 0.185 |

| Neurological | 4 (1.4) | 9 (2.6) | 13 (2.1) | 0.333 |

| Ophthalmological | 4 (1.4) | 9 (2.6) | 13 (2.1) | 0.333 |

| Otolaryngological | 3 (1.1) | 4 (1.1) | 7 (1.1) | 0.952 |

| Spinal | 1 (0.4) | 5 (1.4) | 6 (0.95) | 0.176 |

Patients may have undergone more than one type of surgery.

P values are for comparing civilians with soldiers.

The median (IQR) LOS for civilians was 3 (1–12) days, and that for soldiers was 4 (2–12) days (Table 3). Lengthy hospital stays were reported for both civilians and soldiers, with more soldiers hospitalized for more than 2 weeks than civilians (53 [20.5% of 258; missing 19] civilians and 80 [23.9% of 335; missing 18] soldiers) (Fig. 3).

Outcome

Among all hospitalized casualties, the majority (n = 419, 69.8% of 600; missing 30) were discharged to their homes or to other nonmedical residences, while 61 civilians (23.2% of 263; missing 14) and 104 soldiers (30.8% of 337; missing 16) were discharged to a rehabilitation center (Table 3). Overall, 51.1% of the severe and critical (ISS >15) casualties were discharged to a rehabilitation center (33 civilians [46.5% of 71; 7 missing] and 56 soldiers [54.4% of 103; 1 missing]). At the time of final data collection, 1 patient (0.2% of 600; missing 29) was still hospitalized and therefore not included in the discharge data.

While the overall mortality rate among the casualties was similar for both civilians and soldiers (2.4%) (Table 3), all but one of the in-hospital deaths occurred among critically injured (ISS ≥25) patients. Thus, in-hospital mortality among critical casualties was 18.3% (13 casualties of 71; missing 3).

Two hundred and fifty-one (39.8%) casualties of this mega MCI had 2 or more hospital admissions. Due to the extreme patient overload in the southern hospitals on October 7, almost 60% of the casualties admitted to those southern hospitals were transferred within their first admission day to another trauma center for continued treatment. Data were not reported from the receiving (last) hospital for 37 of these cases (5.8% of all casualties). In these cases, AIS values from the initial hospital were used (including to calculate the ISS); however, their LOS and outcome data are listed as missing in the tables.

DISCUSSION

This is the first study to provide nationwide data on hospitalized casualties of the October 7th terror attack in Israel, giving an overall description of the hospitalized casualties, their injuries, and their outcomes. Approximately 2000 victims arrived at the EDs, of which 630 were hospitalized due to their injuries.10,15

According to the INTR, on an average Saturday there are approximately 15 injury-related hospital admissions to Soroka and Barzilai Medical Centers. On Saturday, October 7th, approximately 630 casualties were hospitalized in southern hospitals due to their sustained injuries. Due to the massive number of casualties arriving primarily at 2 trauma centers within a very short time period, almost 60% of these wounded were transferred from southern hospitals within the first day, either after receiving initial treatment or directly from the ED to another medical center. Some of the early discharges were due to hospitals operating in “triage mode.” In this mode, patients who do not require immediate intervention are discharged to absorb many patients who require immediate care. These patients are generally readmitted at a later date or transferred to a less saturated hospital to complete their care. In addition, some of the transferred patients received initial emergent interventions (ie, surgery) before being transferred to another hospital. While the MCI in the ED ended after approximately 1 day, the hospitals remained on elevated emergency status for approximately 1 week. During this time, large numbers of medical staff were in the hospital day and night, dealing with the existing casualties and preparing for the possibility of additional MCI events.

While casualties need to be directed to the appropriate level of care to promptly diagnose and treat life-threatening injuries, early treatment is not always possible.16 Many of the casualties were unable to receive definitive care for hours following their injuries due to the extent of the terrorist infiltration on the roads and in the southern communities.

The hospitalized casualties suffered from injuries to almost all body regions, and half suffered from injuries to more than one region. Receiving a very large number of casualties in a short time frame is challenging in itself; the October 7th terror event also saw more multiple injured casualties. For comparison, previous terror attacks in Israel, which were on a much smaller scale, resulted in 40–44% of the hospitalized casualties suffering injuries to more than one body region, whereas in the current, much larger attack, over 50% endured multiple injuries.17

In this mega MCI, the vast majority of patients suffered from penetrating wounds, primarily gunshot-related wounds. This resulted in a large number of casualties requiring urgent surgical intervention. Over 430 (69%) patients underwent at least 1 surgical procedure, 240 of whom were within the first 12 hours of arriving at the TC. This required mobilizing many physicians, nurses, support staff, operating rooms, and diagnostic equipment during a 24-hour period. Part of the response at Soroka Medical Center included repurposing CT scans and operating rooms that do not usually serve trauma patients for emergency imaging and surgery.18

The in-hospital mortality rate was relatively low. In comparison to prior terror attacks, where the in-hospital mortality ranged between 4 and 6%,17 the in-hospital mortality rate for the October 7th attack was 2.2%.19 A possible explanation is that the wounded who arrived at the ED included many casualties who were able to survive very long evacuation times, resulting in a selection bias that underrepresented deadlier injuries. The corollary is a very high prehospital death toll. Among the severe and critical casualties (ISS >15), in-hospital mortality for the October 7th attack was 7.7%. In comparison, in a study of hospitalized casualties with violence-related gunshot wounds in Israel, the in-hospital mortality rate was 25%.20 This may be due in part to the same selection (survival) bias described above; however, this discordance remains even within standard ISS-defined injury severity categories. Further investigations are needed to understand these differences in mortality rates.

Finally, a quarter of the patients were discharged to a rehabilitation center, including half of the severe and critically wounded casualties (ISS >15). This surge in the need for rehabilitation (including long-term) resulted in an extraordinary demand for rehabilitation resources in a very short period of time, necessitating immediate reorganization and repurposing of some existing medical facilities to accommodate all the casualties requiring rehabilitation. For example, the Sheba Medical Center reported that less than 48 hours after the October 7th attack they had transferred their geriatric patients to an area protected from rocket attacks and used the now empty ward to create a new rehabilitation center with 36 beds.21 This rehabilitation center has since increased its capacity to treat hundreds of civilians and soldiers injured since October 7.

LIMITATIONS

This study utilized data from the INTR, a national database that includes hospitalized casualties. Thus, the victims who died at the scene or before hospital arrival, and the injured who were discharged following treatment in the ED, were not included in this study. We believe it is reasonable to assume that nearly all moderately to severely wounded casualties, as well as many lightly injured casualties (based on the inclusion of many casualties with ISS 1–8), who survived to the hospital, are included. The resources used by the casualties discharged from the ED, who are presumably the more lightly injured, are not included. We thus cannot present the demographics and mechanisms for all casualties arriving in the ED, or discuss the total resource usage in the ED phase of treatment. Injury severity and body regions, as well as hospital resource usage, only apply to those patients who were admitted. Variables such as amputations and surgical procedures are likely much more complete as these patients can be reasonably assumed to have been admitted.

Because of the hospital-based nature of our data capture, the INTR does not have prehospital data for casualties who did not survive hospital arrival. While this is less relevant for the present study of admitted patients, a national data registry that combines prehospital data with hospital-based data would very likely lead to improved casualty care.

Due to the overwhelming number of patients arriving at hospitals within a very short time span, not all data were recorded with the desired quality, especially prehospital data; for instance, time from injury until arrival in the ED. Those data are therefore not reported quantitatively.

There were 29 casualties who were transferred from southern hospitals, after initial stabilization and admission, to other hospitals, for whom data were not available from the receiving hospitals. It is not clear how these missing data would affect the reported LOS and outcomes. In addition, the number of procedures is likely to be slightly higher than reported since it is possible that these casualties underwent procedures in the receiving hospitals that were reported as unknown in this study.

CONCLUSIONS

The October 7th Hamas terror attack resulted in a mega MCI. Among the many challenges faced by Israel’s hospitals were the efficient absorption, diagnosis, and treatment of a large number of casualties, from babies to the elderly, many of whom were multiplely injured. One-quarter of hospitalized victims required transfer to rehabilitation centers after their acute hospital stay. The injury details and outcomes of the hospitalized casualties from this mega MCI provide important information for MCI planning and preparedness at the local, regional, and national levels.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Israel Trauma Group (ITG) includes: H. Bahouth, A. Bar, A. Braslavsky, D. Czeiger, D. Fadeev, A. L. Goldstein, I. Grevtsev, G. Hirschhorn, I. Jeroukhimov, A. Kedar, Y. Klein, A. Korin, B. Levit, I. Schrier, A. D. Schwarz, W. Shomar, D. Soffer, M. Weiss, O. Yaslowitz, I. Zoarets.

Footnotes

Published online 5 August 2024

Sharon Goldman and Ari M. Lipsky are considered as co-first author.

Disclosure: The authors declare that they have nothing to disclose.

S.G. participated in research design, writing the paper, performing the research, and data analysis; A.M.L. participated in writing the paper and research performance and data analysis; I.R. and A.G. participated in research design, performance of the research, analytic tools, and data analysis; O.A. and A.B. participated in research performance; and E.K. participated in research design and performance.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: H. Bahouth, A. Bar, A. Braslavsky, D. Czeiger, D. Fadeev, A. L. Goldstein, I. Grevtsev, G. Hirschhorn, I. Jeroukhimov, A. Kedar, Y. Klein, A. Korin, B. Levit, I. Schrier, A. D. Schwarz, W. Shomar, D. Soffer, M. Weiss, O. Yaslowitz, and I. Zoarets

REFERENCES

- 1.Ray M. Madrid train bombings of 2004. Encyclopedia Britannica, 2010. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Madrid-train-bombings-of-2004. Accessed January 21, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ray M. Paris attacks of 2015 Encyclopedia Britannica, 2015. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/event/Paris-attacks-of-2015. Accessed January 21, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ray M. 10th Anniversary of the London Bombings Encyclopedia Britannica. 2010. Available at: https://www.britannica.com/story/10th-anniversary-of-the-london-bombings. Accessed January 21, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biddinger PD, Baggish A, Harrington L, et al. Be prepared — The Boston Marathon and Mass-Casualty Events. N Engl J Med. 2013;368:1958–1960. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Daniel Byman APCDMH and DD. Hamas’s October 7 attack: visualizing the data. 2023. Available at: https://www.csis.org/analysis/hamass-october-7-attack-visualizing-data. Accessed February 12, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 6.By TOI STAFF and JACOB MAGID. Nov. 17: death toll from Re’im massacre updated to 364 – almost 1/3 of Oct. 7 deaths. November 2023. Available at: https://www.timesofisrael.com/liveblog-november-17-2023. Accessed February 12, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avraham Y. The investigation of the attack on the observation post reveals: the female soldiers suffocated to death from a poison gas grenade that was thrown into the room. N12 News. December 13, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Israel Defense Forces. War against Hamas what happened in the October 7th Massacre? October 2023. Available at: https://www.idf.il/en/mini-sites/hamas-israel-war-24/all-articles/what-happened-in-the-october-7th-massacre/. Accessed January 22, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 9.www.fdd.org. November 12, 2023. israel-revises-october-7-death-toll-after-agonizing-forensics. Accessed January 22, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ministry of Health. Iron Sword Hospitalizations and ED visits, 2023. Available at: https://datadashboard.health.gov.il/portal/dashboard/health. Accessed January 10, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statistical Abstract of Israel 2023, No. 74. Table 2.1: Population, by Population Group.; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Baker SP, O'Neill B, Haddon W, Jr, et al. The injury severity score: a method for describing patients with multiple injuries and evaluating emergency care. J Trauma. 1974;187–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rozenfeld M, Radomislensky I, Freedman L, et al. ISS groups: are we speaking the same language? Inj Prev. 2014;20:330–335. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Champion HR, Copes WS, Sacco WJ, et al. The major trauma outcome study: establishing national norms for trauma care. J Trauma. 1990;30:1356–1365. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Levi-Belz Y, Groweiss Y, Blank C, et al. PTSD, depression, and anxiety after the October 7, 2023 attack in Israel: a nationwide prospective study. EClinicalMedicine. 2024;68:1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Almogy G, Mintz Y, Zamir G, et al. Suicide bombing attacks. Ann Surg. 2006;243:541–546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Israel National Center for Trauma and Emergency Medicine Research. Trauma Injuries in Israel 2010-2015: National Report 2016 [Hebrew].; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Codish S, Frenkel A, Klein M, et al. October 7th 2023 attacks in Israel: frontline experience of a single tertiary center. Intensive Care Med. 2024;50:308–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rozenfeld M, Givon A, Rivkind A, et al. ; Israeli Trauma Group (ITG). New trends in terrorism-related injury mechanisms: is there a difference in injury severity? Ann Emerg Med. 2019;74:697–705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldman S, Bodas M, Lin S, et al. ; Israel Trauma Group (ITG). Gunshot casualties in Israel: a decade of violence. Injury. 2022;53:3156–3162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Unyielding hope: Sheba’s ‘returning to life’ rehab initiative. Available at: https://sheba-global.com/shebas-returning-to-life-rehab-initiative/. [Google Scholar]