Abstract

Neuroinflammation plays a crucial role in the development and progression of neurological disorders. MicroRNA-155 (miR-155), a miR is known to play in inflammatory responses, is associated with susceptibility to inflammatory neurological disorders and neurodegeneration, including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, multiple sclerosis, and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis as well as epilepsy, stroke, and brain malignancies. MiR-155 damages the central nervous system (CNS) by enhancing the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines, like IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, and IRF3. It also disturbs the blood–brain barrier by decreasing junctional complex molecules such as claudin-1, annexin-2, syntenin-1, and dedicator of cytokinesis 1 (DOCK-1), a hallmark of many neurological disorders. This review discusses the molecular pathways which involve miR-155 as a critical component in the progression of neurological disorders, representing miR-155 as a viable therapeutic target.

Keywords: MicroRNA-155; Neurodegenerative diseases; Epilepsy; Brain malignancies; Stroke, RNA therapeutics

Introduction

MicroRNAs (miRs) are a class of short regulatory elements with 18–25 nucleotides critically implicated in the post-transcriptional regulation of genes (Tonacci et al. 2019). MiRNAs are expressed in all body tissues with a higher level in the nervous system (Nielsen et al. 2009). Most of the known miRs expressed in the brain and spinal cord that is believed to regulate two-thirds of total mRNAs (Kou et al. 2020). A single miR could target and change the expression of many genes or many other miRs, hence having fundamental roles in both normal physiological processes and pathological conditions (Tonacci et al. 2019).

MiR-155, a novel-defined and multifunctional miR, was initially identified as an immune regulator (Thai et al. 2007; Gracias et al. 2013). Recent studies suggest that miR-155 is also involved in developing and progressing neurological disorders (Adly Sadik et al. 2021; Maciak et al. 2021). Because this miR is a potent activator of inflammation, it is also called inflamma-miR (Maciak et al. 2021). This miR is a critical pro-inflammatory microRNA involved in various physiological and pathological functions such as immunity, inflammation, cardiovascular disorders, neurological disorders, and malignancies (Gomes et al. 2020; Oliveira et al. 2020; Adly sadik et al. 2021).

miRNA-155 and Targets

The functional significance of miRNAs is the gene regulation through RNA-dependent post-transcriptional silencing mechanisms (Krol et al. 2010). mRNA 3′-UTR is targeted, leading to mRNA downregulation inhibiting the expression of specific target genes. The mode of action of miRNA has been comprehensively reviewed elsewhere (Pasquinelli 2012; Fabian and Sonenberg 2012). Altered biological function and abundance of miRNAs are found in different cells, tissues, and diseases, implying the necessity of a complete characterization of the potential targets. The miRNA-target interactions are beyond repression. It also includes an increased expression of target genes or induction of correlations of different targets (Hausser and Zavolan 2014). Table 1 represents the key target pathways of miRNA-155 in different cells and states. The potential target factors of expressed miRNA-155 could also be involved in neurodegeneration-related pathways. So, the neurodegenerative phenotypes would be associated with such control of genetic signaling relevant to diseases (Rizzuti et al. 2018). Therefore, understanding gene networks will be a potential strategy for treating complex conditions like neuroinflammation.

Table 1.

Examples of potential targets responsive to miR-155

| Function | Key target | Experimental cell | Related condition | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Repressor | SOCS1 | Microglia | Neuroinflammation | Zheng et al. (2018) |

| TAB2 (TLRs/IL-1 signaling) | Human DCs | Inflammatory stimulation | Ceppi et al. (2009) | |

| TAB2/ iNOS | MSCs | Inflammation | Xu et al. (2013) | |

| FoxO1/ ROS | NSCLC cell | NSCLC | Hou et al. (2016) | |

|

C/EBPβ CREB |

3T3-L1 cells | Adipogenesis | Liu et al. (2011) | |

| LKB1 | Cervical cancer cells | Cervical cancer | Lao et al. (2014) | |

| MyD88 (TLRs/IL-1 signaling), IL-8 | AGS/ HEK-293 cells | H. pylori-related inflammation | Tang et al. (2010) | |

| κB-Ras1 (NF-κB inhibitor) | BM endothelial cells | Myeloproliferative disorders | Wang et al. (2014a, b) | |

| SHIP1 | Human NK cells | Infectious pathogens and tumor surveillance | Trotta et al. (2012) | |

| Bcl-6 | Macrophages | Atherosclerosis | Nazari-Jahantigh et al. (2012) | |

| Bcl-6 and Hdac4 | Naïve B cells | Leukemias | Sandhu et al. (2012) | |

| SMAD2 | THP-1 and HeLa cells | Homeostatic controls mediated by TGF-β | Louafi et al. (2010) | |

| SOCS1/6 | NRK-49F and HK-2 cells | Renal fibrosis | Zhang et al. (2020a, b) | |

| PU.1 | FLT3-ITD-associated leukemic cells | AMLs | Gerloff et al. (2015) | |

| PP2A | PBMCs | Juvenile SLE | Lashine et al. (2015) | |

| Nrf2 | SCs | DPN | Chen et al. (2019) | |

| CDX1 | Glioma cells | Glioma | Yang et al. (2017) | |

| SOCS1 | CD4+ T lymphocytes | AP | Wang et al. (2018) | |

| BRG1 | NKTCL cells | Lymphangiogenesis | Chang et al. (2019) | |

| IKKε | MCF-7 breast cancer cells | Breast cancer | Harquail et al. (2018) | |

| HIF1α | SKOV3 cells | Ovarian cancer | Ysrafil et al. (2020) | |

|

PI3K/Akt/mTOR BDNF and TrkB |

Epilepsy cells | Temporal lobe epilepsy | Duan et al. (2018) | |

| Inducer |

MHCII (I/A-I/E), CD86, CD40 IL-12p70, IFN-γ, IL-10 |

DCs | DC therapy | Asadirad et al. (2019) |

| Autophagy | Osteosarcoma cells | Chemotherapy resistance in osteosarcoma | Chen et al. (2014) | |

| SIRT1 | Primary human CD4+ cells | Neuropathic pain | Heyn et al. (2016) | |

| Wnt/β-catenin | Colorectal cancer SW-480 cells | Colon cancer | Liu et al. (2018) | |

| c-Fos, NLRP3, and caspase-1 | A549 cells | monocrotaline-induced PAH | Chai et al. (2020) | |

| caspase-3, p53 and Bax | Epilepsy cells | Temporal lobe epilepsy | Duan et al. (2018) |

SOCS1 suppressor of cytokine signaling 1, TAB2 TAK1-binding protein 2, TLRs toll-like receptors, IL-1 interleukin 1, DCs dendritic cells, MSCs mesenchymal stem cells, FoxO1 forkhead box protein O1, ROS reactive oxygen species, NSCLC non-small cell lung carcinomas, C/EBPβ CCAAT/enhancer binding protein beta, CREB cAMP response element-binding protein, LKB1 Liver kinase B1, MyD88 myeloid differentiation protein 88, HEK human embryonic kidney, NF-κB, nuclear factor κB, BM, bone marrow, SHIP1 Src homology 2-containing inositol-5'-phosphatase 1, NK Natural Killer, Bcl-6 B-cell lymphoma 6, Hdac4 Histone deacetylase 4, TGF-β transforming growth factor-β, NRK-49F rat kidney fibroblast cells, HK-2, human kidney 2, FLT3 FMS-like tyrosine kinase 3 receptor, ITD internal tandem duplications, AMLs acute myeloid leukemias, PP2A protein phosphatase 2A, PBMCs peripheral blood mononuclear cells, SLE systemic lupus erythematosus, Nrf2 nuclear transcription factor 2, SCs rat Schwann cells, DPN diabetic peripheral neuropathy, CDX1 caudal-type homeobox 1, AP acute pancreatitis, BRG1 Brahma related gene 1, NKTCL natural killer/T-cell lymphoma, IKKε IκB kinase ε, HIF1α hypoxia-inducible factor-1α, PI3K phosphoinositide 3-kinase, Akt protein kinase B, mTOR mechanistic target of rapamycin, BDNF brain-derived neurotrophic factor, TrkB tropomyosin receptor kinase B, MHC major histocompatibility complex, CD86 Cluster of Differentiation 86, IFN-γ interferon-gamma, SIRT1 histone deacetylase sirtuin1, NLRP3 NLR family pyrin domain containing 3, PAH pulmonary arterial hypertension

MiR-155 and Neuroinflammation

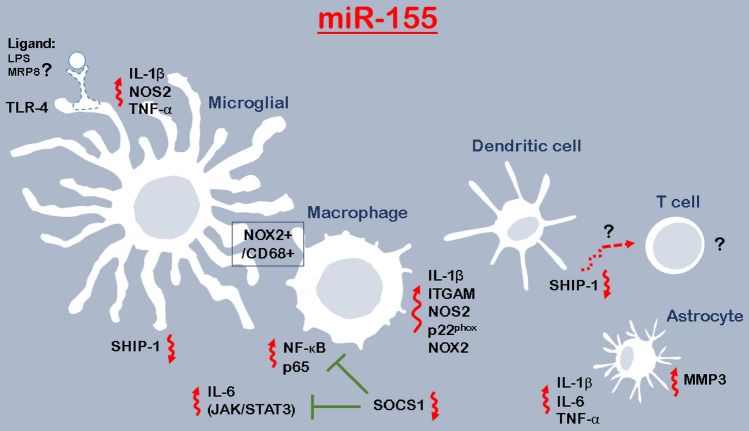

miR-155 is emerged as a crucial regulator of inflammatory responses, as it is regulated by Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands in cells, like monocyte-derived cells (Fig. 1) (Koch et al. 2012). Its expression is positively correlated with cytokines release (Woodbury et al. 2015; Maciak et al. 2021). Overexpression of miR-155 in dendritic cells can induce an autoimmune response by reducing the level of the SH-2-containing inositol 5'-polyphosphates 1 (SHIP1) (Lind et al. 2015). SHIP1, which catalyzes the conversion of phosphatidylinositol (3,4,5)-trisphosphate to phosphatidylinositol (3,4)-bisphosphate, would be necessary for immune responses because the lack of this molecule in dendritic cells is sufficient to induce a CD8-mediated autoimmune response and break T-cell tolerance (Fig. 1) (Lind et al. 2015). Because autoimmune is strongly related to neurological disorders, particularly degenerative diseases, there seems to be a close relationship between miR-155 and different neurological disorders.

Fig. 1.

The pro-inflammatory activation responses induced by miR-155. Under pro-inflammatory stimuli, miR-155 is introduced as the most overexpressed miRNAs in microglial cells. The overexpression of miR-155, therefore, is associated with cytokines release, including IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α. In pro-inflammatory microglia, induced IL-6 amplifies these cells and influences the regulation of neurogenesis, for example, through JAK/STAT3 signaling. MiR-155 is regulated by Toll-Like Receptor (TLR) ligands and with lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a pro-inflammatory ligand for TLR-4, which is reported specific to microglia, would account for inflammation-induced neurogenic deficits. There is an association between miR-155 expression and the number of co-expressed NOX2 + /CD68 + microglia/macrophages in post-traumatic neuroinflammatory responses. As miR-155 expresses in the robust and persistent neuroinflammatory response, it might be a therapeutic target for neuroinflammation. Macrophages are also the cells in which miR-155 can be specifically upregulated, driving them toward a pro-inflammatory phenotype. In addition, TLR-matured dendritic cells expressing miR-155 can break immune tolerance. It seems that regulation of miR-155 of SHIP1 sounds a unique axis regulating dendritic cells’ function and promoting T cells (CD8 +)-mediated autoimmune responses. It is important to understand the cells interactions that would be mediated by miRNAs abundance. Microglia, macrophage, and astrocyte, together with the sustained cytokines signaling, participate in the inflammatory responses in the CNS. TLR ligands and cytokines influence astrocytes expressing miR-155. IRF3 can suppress pro-inflammatory cytokine gene expression and then neuroinflammation via regulating the immunomodulatory miR-155 expression. According to the role of TLRs-related miRNAs (miR-132) (Kong et al. 2015) in the regulation of myeloid-related protein-8 (MRP8)-induced astrocyte activation, there might be a need to assess miR-155 in the modulation of neuroinflammation induced by ligands

Pro-inflammatory stimuli have been found to upregulate miR-155 and this miRNA, like an amplifier, represses anti-inflammatory molecules leading to inflammation induction (Woodbury et al. 2015). MiR-155 is activated in macrophages and microglia and directs them to pro-inflammatory conditions (Henry et al. 2019). MiR-155 emerged as crucial regulators of inflammatory responses is regulated by Toll-like receptor (TLR) ligands in cells, like monocyte-derived cells (Fig. 1) (Koch et al. 2012). This miRNA is the most upregulated one in microglia under pro-inflammatory activation and is essential for pro-inflammatory cytokines induction in microglia (Woodbury et al. 2015). MiR-155 knockdown in microglia by hairpin inhibitors (antagomirs) reduces the release of inflammatory mediators, including interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα), and nitric oxide that ameliorates microglia-mediated neurotoxicity (Henry et al. 2019). This miRNA also complicates astrocyte pro-inflammatory gene expression activates astrocytes (Tarassishin et al. 2011), which results in the release of IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (Kong et al. 2015). However, suppressing the miR-155 inhibits astrocyte inflammatory gene expression executed by interferon regulatory factor 3 (IRF3) (Tarassishin et al. 2011). In addition, miR-155 upregulation is accompanied by increases of γ‐aminobutyric acid (GABA) transporter type 1 and type 3 (GAT-1 and GAT-3), involved in modulation of the levels of extracellular GABA, leading to neuroinflammation (Zhang et al. 2019).

Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1) is one of the central target genes of miR‐155 (Cardoso et al. 2012). This anti‐inflammatory protein is an important inflammation regulator and its deficiency results in an increase in inflammation in tissues (Zhang et al. 2019). MiR‐155 has been found to decrease SOCS1 and promote the expression of IL‐1β and TNF‐α (Wen et al. 2014; Zhang et al. 2019). SOCS1 inhibits Janus kinase 2 /signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (JAK2/STAT3) signaling, one of the major pathways for cytokine signal transduction, and controls inflammation (Recio et al. 2014). This anti‐inflammatory protein can also suppress nuclear factor kappaB (NF-κB) by diminishing p65 stability within the cell nucleus, which represses the release of inflammatory cytokines (Strebovsky et al. 2011). On the other hand, overexpression of miR-155 in macrophages increases the level of NF-κB and p65 and the level of pro-inflammatory cytokines by decreasing the expression of SOCS1 (Jiang et al. 2019).

SHIP1 is another potential target of miR-155 in macrophages (Yang et al. 2018), inhibiting macrophage proliferation (Gloire et al. 2007). This protein also plays a critical role in the regulation of NF-κB pathway (Gloire et al. 2007). Since miR-155 decreases the level of SHIP1, it promotes the proliferation of macrophages and inflammation (Jiang et al. 2019).

Another important point is that upregulation of miR-155 increases blood–brain barrier (BBB) permeability, which mimics cytokine-induced alterations in junction structures. It modulates BBB function by targeting cell–cell complex molecules including claudin-1 and annexin-2 and focal adhesion components such as syntenin-1 and dedicator of cytokinesis 1 (DOCK-1) (Lopez-Ramirez et al. 2014). Given that BBB dysfunction is a hallmark of many neurological disorders (Lopez-Ramirez et al. 2014), and on the other hand according to the role of miR-155 in causing impaired BBB, it seems that this miR should be considered a therapeutic approach. Figure 1 shows the role of miR-155 in neuroinflammation.

Alzheimer’s Disease

Alzheimer’s disease (AD), the most common neurodegenerative disease, is clinically characterized by dementia (Soria Lopez et al. 2019). Since the hippocampus, one of the main brain parts involved in cognition (Rastegar-Moghaddam et al. 2019; Baradaran et al. 2020), is damaged in this disease, it is estimated that approximately 65% of cognition impairments are due to this neurodegenerative disease (Mantzavinos and Alexiou 2017; Han et al. 2020). The main pathological change is forming the extracellular plaque after oligomerizing amyloid-β (Aβ) monomers (Tiwari et al. 2019; Mohammadipour and Abudayyak 2021).

Dysregulation of miR-155 in AD brain has been reported in previous studies and there is a large document about the relationship between miR-155 and AD pathogenesis (Guedes et al. 2015; Arena et al. 2017). Also, this miR is associated with some crucial genes involved in AD, such as PICALM, SORL1, MS4A4A, and CD33 (Guedes et al. 2015).

MiR-155 could influence Aβ production by altering sorting nexin 27 (SNX27) expression (Fig. 2). Overexpression of miR-155 has been shown to reduce the SNX27 level and on the other hand, reduction of SNX27 expression is associated with increases in Aβ production and hippocampal neuronal loss in AD mouse model (Wang et al. 2014a, b). In addition, SNX27 has a crucial role in the dynamic trafficking of important brain receptors and ion channels such as G-protein-activated inward rectifying potassium type 2 (GIRK2), β2-adrenergic receptors (β2-AR), N-Methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-type glutamate receptor subunit 2C (NR2C), and serotonin receptor subunit 4a (5-HT4a) (Wang et al. 2013). Therefore, overexpression of miR-155 in AD negatively regulates SNX27, thereby resulting in synaptic dysfunction, which is a hallmark of AD.

Fig. 2.

MiR-155 and its intracellular targets in the neurological disorders. MiR-155 dysregulates (in red) molecules, which play a lot in neurological disorders. In each disorder, the typical consequences of the dysregulation are indicated as; inflammation, apoptosis, and synaptic dysfunction in AD; apoptosis, inflammation, and microgliosis in PD; immune responses in ALS; inflammation in MS; BBB disturbance in Epilepsy; cells apoptosis in Ischemic stroke; mitochondrial dysfunction in Spinal cord injuries; cells proliferation in Cancer. Hence, miR-155 would be considerably described within combinatorial therapies

As mentioned, miR-155 overexpression is accompanied by the promotion of Aβ production and because Aβ is an activator of NF-κB in both neurons and astrocytes, its overproduction results in inflammation in the brain (Fig. 2). Overexpression and over-activation of NF-κB has been reported in Post-mortem studies of the AD brain (Snow and Albensi 2016) and research studies have confirmed the regulation of NF-κB by Aβ (Valerio et al. 2006). NF-κB activation increases cytokine levels and elevates COX2 expression in neurons, related to AD pathogenesis (Kaltschmidt et al. 2002). Because COX2 is among the players in initiating the inflammatory response by triggering the production of other pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines, it plays a crucial role in inflammatory diseases such as AD (Lee et al. 2018).

A study by Liu et al. (2019) showed that intraventricular infusion of a miR-155 inhibitor prevents IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α elevation in AD hippocampus (Table 2) and also attenuates upregulation of caspase-3 and alleviates cognitive impairment (Liu et al. 2019). The increased miR-155 level has been associated with decreased SHIP1 level in the hippocampus of the rat model of AD (Aboulhoda et al. 2021). MiR-155 activates Akt kinase by repressing the expression of SHIP1 (Fig. 2), leading eventually to neurofibrillary development in AD (Aboulhoda et al. 2021). A recent study reported that treatment with both mesenchymal stem cells and hydrogen sulfide (H2S) extracted microvesicles could decrease miR-155 level and Akt activity due to their potent anti-inflammatory properties, which led to a decrease in apoptosis in the hippocampus and cerebral cortex (Aboulhoda et al. 2021). So, miR-155 seems to be a potent therapeutic element that should be more considered in future molecular therapies.

Table 2.

MiR-155 inhibition as a potent therapeutic for neurological disorders

| Disorder | Experimental model | Result | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| AD | Intracerebroventricular injection of miR-155 inhibitor in rat AD model | Attenuation of increase of IL-1β, IL-6, TNF-α, their receptors, and Caspase-3, Alleviation of cognitive impairment | Liu et al. (2019) |

| PD | miR-155 -/- mice | Reduction of pro-inflammatory response to α-Synuclein, Inhibition of neurodegeneration | Thome et al. (2016) |

| ALS | Intracerebroventricular injection of miR-155 inhibitor in mouse ALS model | Delay in disease onset, Restoration of dysfunctional microglia, Prolongation of animal survival | Butovsky et al. (2015) |

| MS | miR-155 -/- mice | Decrease in production of IFN-γ and IL-17, Reduction of demyelination, Reduction of paralytic symptoms | Murugaiyan et al. (2011) |

| Epilepsy | Intracerebroventricular injection of miR-155 inhibitor in a mouse model | Microglia morphology change suppression, Rescue of BDNF reduction, Decrease in abnormal electroencephalography | Cai et al. (2016) |

| Stroke | Intravenous injection of miR-155 inhibitor in a mouse model | Reduction of infarct size (by 34%), Improvement of microvascular integrity, Improvement of animal functional recovery | Caballero-Garrido et al. (2015) |

| Malignancies | In vitro knockdown of miR-155 in Glioma and glioblastoma | Sensitization of tumoral cells to chemotherapy, Induction of apoptosis, Slowing the progression of cancer | Meng et al. 2012 Liu et al. (2015) |

| Spinal cord injury |

Intrathecal injection in rat miR-155 -/- mice |

Locomotor promotion, Neuropathic pain attenuation Decrease in incidence of paralysis |

Tan et al. (2015) Awad et al. (2018) |

Parkinson’s Disease

PD, the second most common neurodegenerative disorder worldwide, is characterized by a progressive loss of dopaminergic neurons in the midbrain (Heidari et al. 2019; Mohammadipour et al. 2020; Bigham et al. 2021) and is clinically manifested by both movement disabilities and behavioral disorders (Mohammadipour et al. 2020; Bigham et al. 2021). Changes in miR-155 expression have been demonstrated to be closely associated with PD. The elevation of the expression level of this miR has been reported in both PD patients (Caggiu et al. 2018) and the animal model of PD (Thome et al. 2016). Because inflammation plays a critical role in PD progression (Mohammadipour et al. 2020), miR-155, as a main inflammation regulator, is strongly involved in this common neurodegenerative disease. It amplifies the level of pro-inflammatory cytokines, including TNF-α, which are directly involved in cell death. TNF-α is strongly linked to apoptosis induction through the TNFR1 receptor death domain. This binding results in activating caspases 1 and 3, which finally leads to apoptosis (Mogi et al. 2000). MiR-155 has also been found to suppress anti-inflammatory targets such as SHIP1 and CEBPβ (Fig. 2), which results in downregulation of the Arg1, IL-10, IL13R, and TGFβR and leads to cell death (Thome et al. 2016).

Thome et al. (2016) found that complete deletion of miR-155 in PD animals reduces pro-inflammatory responses (Table 2) and alleviates PD symptoms (Thome et al. 2016). Documents also show a relationship between miR-155 and α-synuclein (Fig. 2). Protein α-synuclein is a hallmark of PD and plays a central role in the pathophysiology of PD (Mohammadipour et al. 2020; Bigham et al. 2021). It has been shown that overexpression of α-synuclein induces expression of miR-155, leading to induction of neuroinflammation (Thome et al. 2016). It has also been found that miR-155 elevates MHCII expression and microgliosis in response to α-synuclein overexpression that increases neuronal damages (Thome et al. 2016). Taken together, α-synuclein-induced neuropathology is closely associated with miR-155 and knocking out it can prevent α-synuclein-associated neurodegeneration.

Another damaging pathway of miR-155 in PD is via affecting the DJ-1, also known as PARK7 (Parkinson protein 7), which is an onset autosomal-recessive PD gene (Bonifati et al. 2003) and has anti-inflammatory properties (Kim et al. 2014). DJ-1 also is found to act as a chaperone to suppress a-synuclein fibrillation (Kim et al. 2014). MiR-155 suppression increases DJ-1 expression, thereby suppressing a-synuclein aggregation, inhibiting inflammation, and reducing signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT1) activation (Kim et al. 2014). Since the reduction of STAT1 activity results in inhibition of interferon-gamma (IFN-γ), it is directly associated with reducing neural damage (Kim et al. 2014).

Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS)

ALS is a fatal and multifactorial neurodegenerative disease caused by the progressive degeneration of upper and lower motor neurons, leading to paralysis and death (Izrael et al. 2020; Pegoraro et al. 2020). Motor neuron degeneration in this progressive disease is associated with several pathophysiological processes including, protein aggregation, inclusion bodies formation, mitochondrial dysfunction, demyelination, impairment in RNA processing, and disruption of the neuromuscular junction (Izrael et al. 2020).

Although ALS was not primarily considered an immune-mediated disease in the past, today, there is evidence that the immune system plays a central role in the pathogenesis of the disease. In ALS patients and animal models, microglia and astrocytes have been observed activated during disease progression and evidence suggests that inflammatory responses contribute to neuronal death (Butovsky et al. 2015). Recently, astrocytes were introduced as significant contributors to motor neuron degeneration in ALS (Gomes 2020). Since miR-155 upregulation is associated with astrocytes and microglia activity (Henry et al. 2019), it can be involved in ALS.

Studies have proven elevation of miR-155 expression in the spinal cord of both sporadic and familial ALS, and the role of this miR in ALS progression has well been demonstrated (Butovsky et al. 2015). Also, it has been found that miR-155 expression is increased in the skeletal muscles of ALS patients (Pegoraro et al. 2020). Therefore, inhibition of miR-155 could be considered as a therapeutic approach (Table 2). Butovsky et al. (2015) observed that intracerebroventricular injection of anti-miR-155 repressed microglial miR-155 targeted genes and also found that peripheral anti-miR-155 treatment delayed not only disease onset but also prolonged ALS animals’ survival (Butovsky et al. 2015). The important point is that miR-155 upregulation in ALS occurs earlier, even before disease onset, and in the absence of other pro-inflammatory markers (Cunha et al. 2018). Therefore, the upregulation of miR-155 seems to be an excellent supplementary marker to track ALS at its early stage.

Multiple Sclerosis (MS)

MS is an autoimmune disease characterized by chronic inflammation, myelin loss, axonal damage, and progressive neurological dysfunction (Maciak et al. 2021).

Because of miR-155 influence on myeloid cell polarization and its role in changing these cells from phenotypic to functional pro-inflammatory form, it is considered an essential miR in the pathogenesis of autoimmune diseases such as MS (Maciak et al. 2021). Upregulation of miR-155 has been reported in both serum (Paraboschi et al. 2011) and MS patients’ brains (Noorbakhsh et al. 2011). As mentioned above, miR-155 dysregulation results in BBB dysfunction, and in the course of MS, it helps infiltration of CD4+ and CD8+ T cells and B cells into the brain (Kasper and Shoemaker 2010; Maciak et al. 2021), which ultimately causes myelin sheaths damage, followed by axonal injury leading to movement disabilities.

This miR plays an indispensable role in regulating lymphocyte subsets, including B cells, CD4+ and CD8+ T cells such as T helper type 1 (Th1), Th2, Th17 and regulatory T cells (Seddiki et al. 2014). CD4+ T cell-mediated autoimmunity besides IFN-γ–producing Th1 cells and IL-17–producing Th17 cells has been accepted as the key participants in MS pathogenesis (Murugaiyan et al. 2011). On the other hand, mir-155 expression is increased in CD4+ T cells of MS mice (Murugaiyan et al. 2011) and modulates Th1 and Th17 cells differentiation (Zhang et al. 2014). A previous study showed that silencing of miR-155 decreases production of IFN-γ and IL-17 (Fig. 2), thereby reducing neuroinflammation and demyelination (Table 2), leading to delayed onset of neurologic impairment and significantly fewer paralytic symptoms (Murugaiyan et al. 2011).

Epilepsy

Temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) is a common and chronic neurological disorder and nearly 30% of patients cannot be treated adequately with anti-epileptic drugs (Korotkov et al. 2018). Neuroinflammation is among the crucial mechanisms and an essential contributor to the development of epilepsy (Fu et al. 2019a). IL-1β has been shown to induce epileptic seizures by upregulation of NMDA receptors (Viviani et al. 2003). This upregulation leads to a rapid increase in intracellular calcium and consequently, it leads to activation of NF-κB (Snow and Albensi 2016). In addition, the elevation of IL-1β levels decreases the long-term potentiation (LTP) and impairs synaptic plasticity, which causes neuronal dysfunction (Han et al. 2016). Besides, TNF-related apoptosis-inducing ligand (TRAIL) expression has been reported to be elevated in epileptic patients. This ligand is a chemokine modulator and its increase leads to cell death and neural dysfunction (Rana and Musto 2018). Since miR-155 is among the central inflammatory regulators, it is closely involved in this common disease. Elevation of miR-155 expression in the brain of both epilepsy patients and kainic acid-induced seizures animals has been reported (Fu et al. 2019b). miR-155 expression starts to elevation 2 h after status epilepticus induction and reaches peak levels in the latent phase (7 days after status epilepticus) of the seizure (Li et al. 2018).

Besides neuroinflammation, remodeling of the extracellular matrix by matrix metalloproteinases (MMPs) has also been shown to play a major role in epilepsy (Korotkov et al. 2018). In epileptic conditions, MMP3 expression is increased and induced by IL-1β, regulated by miR-155 (Fig. 2) (Korotkov et al. 2018). An increase in MMP3 levels by miR-155 induces degradation of the basal lamina and tight junction proteins, leading to BBB dysfunction in epilepsy (Korotkov et al. 2018).

Silencing miR-155 has been found to alleviate seizures by reducing pro-inflammatory cytokine expression, suppressing microglia morphology change, and rescuing brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) reduction (Fig. 2), resulting in a decrease in abnormal behavior electroencephalography (Cai et al. 2016; Fu H et al. 2019). Clinical trials on transient downregulation of miR-155 can be beneficial and worthy of investigation.

Ischemic Stroke

Stroke is among the most common neurological disorders worldwide and ranked the second leading cause of death (Adly Sadik et al. 2021). Hypertension, atherosclerosis, smoking, obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and diabetes mellitus are major risk factors of ischemic stroke, with nearly 80% of stroke cases (Adly Sadik et al. 2021). As miR-155 is involved in hypertension and atherosclerosis, two of the significant risk factors of ischemic stroke (Bruen et al. 2019; Adly Sadik et al. 2021) and because its circulating level has been reported upregulated among stroke patients (Adly Sadik et al. 2021), it is predictable that there is a close relationship between this miR and ischemic stroke.

MiR-155 promotes the M1 polarization of microglia after ischemia and increases neuroinflammation (Ma et al. 2020). Also, following ischemic stroke, an increase in miR-155 level inhibits BDNF expression, disrupting many normal functions and leading to neuronal apoptosis (Lu et al. 2018). In ischemic conditions, miR-155 bounds the 3’-UTR of Rheb and suppresses Rheb expression. The increased miR-155 level also decreases mTOR and p-S6K expression (Fig. 2), leading to increased cell apoptosis and cerebral infarct volume (Xing et al. 2016). A part of the damaging effects of miR-155 is via inhibiting MafB (Fig. 2), which is a kind of the musculoaponeurotic fibrosarcoma oncogene (Maf) family proteins that act as a crucial transcriptional activator of anti-inflammatory cytokine genes (Zhang et al. 2020a). MiR-155 directly targeted 3’UTR of MafB and diminished its expression in cerebral ischemia injuries and resulted in amplification of expression of both inflammatory mediators (IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α) and inflammatory enzymes (COX2 and iNOS) (Zhang et al. 2020a, b).

Studies have revealed that miR-155 has a high potential to be considered a proper protective and therapeutic target for ischemic stroke. MiR-155 inhibition promotes hippocampal neurological functions by diminishing oxidative stress and inflammation (Sun et al. 2019). It also improves microvascular integrity and blood flow in the peri-infarct area. Besides, inhibition of this miR improves capillary tight junction integrity by stabilizing the protein ZO-1 and can rescue the BBB dysfunction after ischemia, which, interestingly, reduces infarct size by 34% (Caballero-Garrido et al. 2015). Additionally, Nampoothiri and Krishnamurthy (2016) reported promoting post-stroke neovascularization and functional recovery by silencing the miR-155 (Nampoothiri and Krishnamurthy 2016).

CNS Malignancies

MiR-155, the first identified oncogene microRNA (Tao et al. 2019), is upregulated in brain malignancies, including glioma and glioblastoma and promotes tumor growth via various mechanisms such as inhibiting γ-aminobutyric acid A receptor 1 (GABRA1) (D'Urso et al. 2012; Sun et al. 2014). MiR-155 induces tumor proliferation by suppressing apoptosis and promoting the invasiveness and migration of glioma cells (Ling et al. 2013). Ling et al. (2013) found that miR-155 functions as an oncogene by targeting forkhead box O3 (FOXO3a) in both the development and progression of glioma (Ling et al. 2013). FOXO3a is a tumor suppressor and a transcription factor that plays a crucial role in cell apoptosis (Fu Y et al. 2019). Upregulation of miR-155 level has been found to downregulate FOXO3a expression (Fig. 2), thereby decreasing tumor cell apoptosis and accelerating cell proliferation (Wu et al. 2019).

This miR also increases glioma cell proliferation by decreasing Max interactor-1 (MXI1) (Zhou et al. 2013). MXI1 is a member of the Mad family of transcription factors and has been shown to inhibit the proliferation of glioma cells by downregulating the cyclin B1 gene (Manni et al. 2002). Other known targets of miR-155 are the wnt signaling and caudal-type homeobox 1 (CDX1) pathway (Fig. 2). This miR promotes the progression of the human glioma by increasing the activation of Wnt (Yan et al. 2015) and decreasing the CDX1 activity (Yang et al. 2017).

MiR-155 downregulation decreases cell proliferation (Kouhkan et al. 2011). The downregulation of this miR by metastasis-associated lung adenocarcinoma transcript 1 (MALAT1) leads to decreased tumor size and cell viability in glioma (Cao et al. 2016). MiR-155 knockdown also sensitizes glioma and glioblastoma cells to the chemotherapy and induces apoptosis by targeting the p38 isoforms mitogen-activated protein kinase 13 (MAPK13) and MAPK14 (Liu et al. 2015; Meng et al. 2012).

Spinal Cord Injuries

Like brain injuries, inflammation occurs as a principal phenomenon in spinal cord injuries. Following spinal cord injury, blood-spinal cord-barrier disruption results in infiltration of numerous peripheral macrophages into the injured area, and among all, M1-polarized macrophages are dominant and play a fundamental role in all processes of spinal cord injury (Ge et al. 2021). Since miR-155 is upregulated in activated astrocytes, activated microglia and M1-polarized macrophages (Henry et al. 2019; Ge et al. 2021) it seems to be a close relationship between this miRNA and spinal cord injuries (Fig. 2). MiR-155 induces mitochondrial dysfunction by activating the NF-κB signaling pathway in vascular endothelial cells after traumatic spinal cord injury and increases their permeability (Ge et al. 2021).

Suppression of Th17 cell differentiation via upregulation of SOCS1 by mir-155 silencing is shown in both in vivo and in vitro (Yi et al. 2015). Inhibition of this miR also increases myelin sparring and enhances the spinal cord repair process, promoting locomotor function (Yi et al. 2015). Awad et al. (2018) reported that miR-155 deletion reduces the incidence of paralysis by 40% after spinal cord ischemia induction (Awad et al. 2018). Besides locomotor promotion, the attenuation of neuropathic pain by regulating serum and glucocorticoid regulated protein kinase 3 (SGK3) and SOCS1 signaling has also been reported in spinal cord injuries after the suppression of miR-155 (Tan et al. 2015) (Table 2). Also, inhibition of miR-155 alleviates neuropathic pain during chemotherapy by decreasing expression of tumor necrosis factor-a receptor (TNFR1), transient receptor potential ankyrin 1 (TRPA1), c-Jun amino-terminal kinase (JNK), and p38-MAPK in the spinal cord (Duan et al. 2020).

Conclusions and Future Perspectives

MiR-155 is closely involved in several neurological diseases and has a major role in developing and progressing these diseases or amplifying the consequences (Fig. 2). Because neuroinflammation plays a crucial role in the damages of neurological diseases, miR-155, as inflamma-miR, is complicated in various neurological diseases. This miR is upregulated in many neurological diseases, including neurodegenerative diseases, epilepsy, ischemic stroke, glioma, and glioblastoma, and induces severe damages through multiple mechanisms and targets. Therefore, inhibiting this miR could be a novel and proper therapeutic target and should be considered. In particular, as glioblastoma is the most common and aggressive malignancy in CNS with a high mortality rate, inhibition of miR-155 could be a valuable treatment strategy for this malignancy. Clinical trials are highly recommended to evaluate the benefits of miR-155 block on the progression of neurological disorders. As miR per se has many targets that will be defined in direct interaction with the medium it involves, using double/multitargets might be beneficial to specify the desired clinical outcomes.

Acknowledgements

We express our sincere gratitude for the Vice Chancellor’s support for Research, Mashhad University of Medical Sciences, Iran. AMM received support from funds from ricerca corrente to IRCCS Istituto Ortopedico Galeazzi.

Authors' Contributions

Seyed HamidReza Rastegar-moghaddama, Alireza Ebrahimzadeh-Bideskan, and Sara Shahba contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. Amir Mohammad Malvandi and Abbas Mohammadipour contributed to overall conceptual design, drafting and final edits, and approval.

Funding

This work was supported by Mashhad University of medical sciences and IRCCS Istituto Ortopedico Galeazzi.

Data Availability

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest to publish this review.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Amir Mohammad Malvandi, Email: amalvandi@gmail.com.

Abbas Mohammadipour, Email: Mohammadipa@mums.ac.ir.

References

- Aboulhoda BE, Rashed LA, Ahmed H, Obaya EMM, Ibrahim W, Alkafass MAL, Abd El-Aal SA, ShamsEldeen AM (2021) Hydrogen sulfide and mesenchymal stem cells-extracted microvesicles attenuate LPS-induced Alzheimer’s disease. J Cell Physiol 236(8):5994–6010. 10.1002/jcp.30283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adly Sadik N, Ahmed Rashed L, Ahmed Abd-El Mawla M (2021) Circulating miR-155 and JAK2/STAT3 axis in acute ischemic stroke patients and its relation to post-ischemic inflammation and associated ischemic stroke risk factors. Int J Gen Med 14:1469–1484. 10.2147/IJGM.S295939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arena A, Iyer AM, Milenkovic I, Kovacs GG, Ferrer I, Perluigi M, Aronica E (2017) Developmental expression and dysregulation of miR-146a and miR-155 in down’s syndrome and mouse models of down’s syndrome and alzheimer’s disease. Curr Alzheimer Res 14(12):1305–1317. 10.2174/1567205014666170706112701 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asadirad A, Hashemi SM, Baghaei K, Ghanbarian H, Mortaz E, Zali MR, Amani D (2019) Phenotypical and functional evaluation of dendritic cells after exosomal delivery of miRNA-155. Life Sci 219:152–162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Awad H, Bratasz A, Nuovo G, Burry R, Meng X, Kelani H (2018) MiR-155 deletion reduces ischemia-induced paralysis in an aortic aneurysm repair mouse model: Utility of immunohistochemistry and histopathology in understanding etiology of spinal cord paralysis. Ann Diagn Pathol 36:12–20. 10.1016/j.anndiagpath.2018.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baradaran R, Khoshdel-Sarkarizi H, Kargozar S, Hami J, Mohammadipour A, Sadr-Nabavi A, Peyvandi Karizbodagh M, Kheradmand H, Haghir H (2020) Developmental regulation and lateralisation of the α7 and α4 subunits of nicotinic acetylcholine receptors in developing rat hippocampus. Int J Dev Neurosci 80(4):303–318. 10.1002/jdn.10026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bigham M, Mohammadipour A, Hosseini M, Malvandi AM, Ebrahimzadeh-Bideskan A (2021) Neuroprotective effects of garlic extract on dopaminergic neurons of substantia nigra in a rat model of Parkinson’s disease: motor and non-motor outcomes. Metab Brain Dis 36(5):927–937. 10.1007/s11011-021-00705-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonifati V, Rizzu P, van Baren MJ, Schaap O, Breedveld GJ, Krieger E (2003) Mutations in the DJ-1 gene associated with autosomal recessive early-onset parkinsonism. Science 299(5604):256–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bruen R, Fitzsimons S, Belton O (2019) miR-155 in the Resolution of Atherosclerosis. Front Pharmacol 10:463. 10.3389/fphar.2019.00463 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Butovsky O, Jedrychowski MP, Cialic R, Krasemann S, Murugaiyan G, Fanek Z (2015) Targeting miR-155 restores abnormal microglia and attenuates disease in SOD1 mice. Ann Neurol 77(1):75–99. 10.1002/ana.24304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caballero-Garrido E, Pena-Philippides JC, Lordkipanidze T, Bragin D, Yang Y, Erhardt EB, Roitbak T (2015) In Vivo Inhibition of miR-155 Promotes Recovery after Experimental Mouse Stroke. J Neurosci 35(36):12446–12464. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1641-15.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caggiu E, Paulus K, Mameli G, Arru G, Sechi GP, Sechi LA (2018) Differential expression of miRNA 155 and miRNA 146a in Parkinson’s disease patients. eNeurologicalSci 13:1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.ensci.2018.09.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Cai Z, Li S, Li S, Song F, Zhang Z, Qi G, Li T, Qiu J, Wan J, Sui H, Guo H (2016) Antagonist Targeting microRNA-155 Protects against Lithium-Pilocarpine-Induced Status Epilepticus in C57BL/6 Mice by Activating Brain-Derived Neurotrophic Factor. Front Pharmacol 7:129. 10.3389/fphar.2016.00129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S, Wang Y, Li J, Lv M, Niu H, Tian Y (2016) Tumor-suppressive function of long noncoding RNA MALAT1 in glioma cells by suppressing miR-155 expression and activating FBXW7 function. Am J Cancer Res 6(11):2561–2574 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cardoso AL, Guedes JR, Pereira de Almeida L, Pedroso de Lima MC (2012) miR-155 modulates microglia-mediated immune response by down-regulating SOCS-1 and promoting cytokine and nitric oxide production. Immunology 135(1):73–88. 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2011.03514.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ceppi M, Pereira PM, Dunand-Sauthier I, Barras E, Reith W, Santos MA, Pierre P (2009) MicroRNA-155 modulates the interleukin-1 signaling pathway in activated human monocyte-derived dendritic cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci 106(8):2735–2740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chai S-D, Li Z-K, Liu R, Liu T, Dong M-F, Tang P-Z, Wang J-T, Ma S-J (2020) The role of miRNA-155 in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension through c-Fos/NLRP3/caspase-1. Mol Cell Toxicol 16:311–320 [Google Scholar]

- Chang Y, Cui M, Fu X, Zhang L, Li X, Li L, Wu J, Sun Z, Zhang X, Li Z (2019) MiRNA-155 regulates lymphangiogenesis in natural killer/T-cell lymphoma by targeting BRG1. Cancer Biol Ther 20(1):31–41 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen L, Jiang K, Jiang H, Wei P (2014) miR-155 mediates drug resistance in osteosarcoma cells via inducing autophagy. Exp Ther Med 8(2):527–532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen J, Li C, Liu W, Yan B, Hu X, Yang F (2019) miRNA-155 silencing reduces sciatic nerve injury in diabetic peripheral neuropathy. J Mol Endocrinol 63(3):227–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cunha C, Santos C, Gomes C, Fernandes A, Correia AM, Sebastião AM, Vaz AR, Brites D (2018) Downregulated Glia Interplay and Increased miRNA-155 as Promising Markers to Track ALS at an Early Stage. Mol Neurobiol 55(5):4207–4224. 10.1007/s12035-017-0631-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan W, Chen Y, Wang XR (2018) MicroRNA-155 contributes to the occurrence of epilepsy through the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Int J Mol Med 42(3):1577–1584 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duan Z, Zhang J, Li J, Pang X, Wang H (2020) Inhibition of microRNA-155 Reduces Neuropathic Pain During Chemotherapeutic Bortezomib via Engagement of Neuroinflammation. Front Oncol 10:416. 10.3389/fonc.2020.00416 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- D’Urso PI, D’Urso OF, Storelli C, Mallardo M, Gianfreda CD, Montinaro A, Cimmino A, Pietro C, Marsigliante S (2012) miR-155 is up-regulated in primary and secondary glioblastoma and promotes tumour growth by inhibiting GABA receptors. Int J Oncol 41(1):228–234. 10.3892/ijo.2012.1420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fabian MR, Sonenberg N (2012) The mechanics of miRNA-mediated gene silencing: a look under the hood of miRISC. Nat Struct Mol Biol 19:586–593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu H, Cheng Y, Luo H, Rong Z, Li Y, Lu P (2019a) Silencing MicroRNA-155 Attenuates Kainic Acid-Induced Seizure by Inhibiting Microglia Activation. NeuroImmunoModulation 26(2):67–76. 10.1159/000496344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu Y, Sun S, Sun H, Peng J, Ma X, Bao L, Ji R, Luo C, Gao C, Zhang X, Jin Y (2019b) Scutellarin exerts protective effects against atherosclerosis in rats by regulating the Hippo-FOXO3A and PI3K/AKT signaling pathways. J Cell Physiol 234(10):18131–18145. 10.1002/jcp.28446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ge X, Tang P, Rong Y, Jiang D, Lu X, Ji C (2021) Exosomal miR-155 from M1-polarized macrophages promotes EndoMT and impairs mitochondrial function via activating NF-κB signaling pathway in vascular endothelial cells after traumatic spinal cord injury. Redox Biol 41:101932. 10.1016/j.redox.2021.101932 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerloff D, Grundler R, Wurm A, Bräuer-Hartmann D, Katzerke C, Hartmann J, Madan V, Müller-Tidow C, Duyster J, Tenen DG (2015) NF-κB/STAT5/miR-155 network targets PU. 1 in FLT3-ITD-driven acute myeloid leukemia. Leukemia 29(3):535–547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gloire G, Erneux C, Piette J (2007) The role of SHIP1 in T-lymphocyte life and death. Biochem Soc Trans 35(Pt 2):277–280. 10.1042/BST0350277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gomes C, Sequeira C, Barbosa M, Cunha C, Vaz AR, Brites D (2020) Astrocyte regional diversity in ALS includes distinct aberrant phenotypes with common and causal pathological processes. Exp Cell Res 395(2):112209. 10.1016/j.yexcr.2020.112209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gracias DT, Stelekati E, Hope JL, Boesteanu AC, Doering TA, Norton J, Mueller YM, Fraietta JA, Wherry EJ, Turner M, Katsikis PD (2013) The microRNA miR-155 controls CD8(+) T cell responses by regulating interferon signaling. Nat Immunol 14(6):593–602. 10.1038/ni.2576 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guedes JR, Santana I, Cunha C, Duro D, Almeida MR, Cardoso AM, de Lima MC, Cardoso AL (2015) MicroRNA deregulation and chemotaxis and phagocytosis impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (amst) 3:7–17. 10.1016/j.dadm.2015.11.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han T, Qin Y, Mou C, Wang M, Jiang M, Liu B (2016) Seizure induced synaptic plasticity alteration in hippocampus is mediated by IL-1β receptor through PI3K/Akt pathway. Am J Transl Res 8(10):4499–4509 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Han C, Guo L, Yang Y, Guan Q, Shen H, Sheng Y, Jiao Q (2020) Mechanism of microRNA-22 in regulating neuroinflammation in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain Behav 10(6):e01627. 10.1002/brb3.1627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harquail J, LeBlanc N, Landry C, Crapoulet N, Robichaud GA (2018) Pax-5 inhibits NF-κB activity in breast cancer cells through IKKε and miRNA-155 effectors. J Mammary Gland Biol Neoplasia 23(3):177–187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hausser J, Zavolan M (2014) Identification and consequences of miRNA-target interactions-beyond repression of gene expression. Nat Rev Genet 15:599–612 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heidari Z, Mohammadipour A, Haeri P, Ebrahimzadeh-Bideskan A (2019) The effect of titanium dioxide nanoparticles on mice midbrain substantia nigra. Iran J Basic Med Sci 22(7):745–751. 10.22038/ijbms.2019.33611.8018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Henry RJ, Doran SJ, Barrett JP, Meadows VE, Sabirzhanov B, Stoica BA, Loane DJ, Faden AI (2019) Inhibition of miR-155 limits neuroinflammation and improves functional recovery after experimental traumatic brain injury in mice. Neurotherapeutics 16(1):216–230. 10.1007/s13311-018-0665-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heyn J, Luchting B, Hinske LC, Hübner M, Azad SC, Kreth S (2016) miR-124a and miR-155 enhance differentiation of regulatory T cells in patients with neuropathic pain. J Neuroinflammation 13(1):1–11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou L, Chen J, Zheng Y, Wu C (2016) Critical role of miR-155/FoxO1/ROS axis in the regulation of non-small cell lung carcinomas. Tumor Biol 37(4):5185–5192 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izrael M, Slutsky SG, Revel M (2020) Rising stars: astrocytes as a therapeutic target for ALS disease. Front Neurosci 14:824. 10.3389/fnins.2020.00824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang K, Yang J, Guo S, Zhao G, Wu H, Deng G (2019) Peripheral circulating exosome-mediated delivery of miR-155 as a novel mechanism for acute lung inflammation. Mol Ther 27(10):1758–1771. 10.1016/j.ymthe.2019.07.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaltschmidt B, Linker RA, Deng J, Kaltschmidt C (2002) Cyclooxygenase-2 is a neuronal target gene of NF-kappaB. BMC Mol Biol 3:16. 10.1186/1471-2199-3-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasper LH, Shoemaker J (2010) Multiple sclerosis immunology: The healthy immune system vs the MS immune system. Neurology 74(Suppl 1):S2-8. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3181c97c8f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim JH, Jou I, Joe EH (2014) Suppression of miR-155 expression in IFN-γ-treated astrocytes and microglia by DJ-1: a possible mechanism for maintaining SOCS1 expression. Exp Neurobiol 23(2):148–154. 10.5607/en.2014.23.2.148 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koch M, Mollenkopf H-J, Klemm U, Meyer TF (2012) Induction of microRNA-155 is TLR-and type IV secretion system-dependent in macrophages and inhibits DNA-damage induced apoptosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109:1153–1162 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong H, Yin F, He F, Omran A, Li L, Wu T, Wang Y, Peng J (2015) The effect of miR-132, miR-146a, and miR-155 on MRP8/TLR4-induced astrocyte-related inflammation. J Mol Neurosci 57(1):28–37. 10.1007/s12031-015-0574-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Korotkov A, Broekaart DWM, van Scheppingen J, Anink JJ, Baayen JC, Idema S, Gorter JA, Aronica E, van Vliet EA (2018) Increased expression of matrix metalloproteinase 3 can be attenuated by inhibition of microRNA-155 in cultured human astrocytes. J Neuroinflammation 15(1):211. 10.1186/s12974-018-1245-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kou X, Chen D, Chen N (2020) The regulation of microRNAs in Alzheimer’s disease. Front Neurol 11:288. 10.3389/fneur.2020.00288 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kouhkan F, Alizadeh S, Kaviani S, Soleimani M, Pourfathollah AA, Amirizadeh N, Abroun S, Noruzinia M, Mohamadi S (2011) miR-155 down regulation by LNA inhibitor can reduce cell growth and proliferation in PC12 cell line. Avicenna J Med Biotechnol 3(2):61–66 (PMID: 23408179) [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krol J, Loedige I, Filipowicz W (2010) The widespread regulation of microRNA biogenesis, function and decay. Nat Rev Genet 11:597–610 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lao G, Liu P, Wu Q, Zhang W, Liu Y, Yang L, Ma C (2014) Mir-155 promotes cervical cancer cell proliferation through suppression of its target gene LKB1. Tumor Biology 35(12):11933–11938 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashine Y, Salah S, Aboelenein H, Abdelaziz A (2015) Correcting the expression of miRNA-155 represses PP2Ac and enhances the release of IL-2 in PBMCs of juvenile SLE patients. Lupus 24(3):240–247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JY, Han SH, Park MH, Baek B, Song IS, Choi MK (2018) Neuronal SphK1 acetylates COX2 and contributes to pathogenesis in a model of Alzheimer’s Disease. Nat Commun 9(1):1479. 10.1038/s41467-018-03674-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li TR, Jia YJ, Wang Q, Shao XQ, Zhang P, Lv RJ (2018) Correlation between tumor necrosis factor alpha mRNA and microRNA-155 expression in rat models and patients with temporal lobe epilepsy. Brain Res 1700:56–65. 10.1016/j.brainres.2018.07.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind EF, Millar DG, Dissanayake D, Savage JC, Grimshaw NK, Kerr WG, Ohashi PS (2015) miR-155 upregulation in dendritic cells is sufficient to break tolerance in vivo by negatively regulating SHIP1. J Immunol 195(10):4632–4640. 10.4049/jimmunol.1302941 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling N, Gu J, Lei Z, Li M, Zhao J, Zhang HT, Li X (2013) microRNA-155 regulates cell proliferation and invasion by targeting FOXO3a in glioma. Oncol Rep 30(5):2111–2118. 10.3892/or.2013.2685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu S, Yang Y, Wu J (2011) TNFα-induced up-regulation of miR-155 inhibits adipogenesis by down-regulating early adipogenic transcription factors. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 414(3):618–624 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q, Zou R, Zhou R, Gong C, Wang Z, Cai T, Tan C, Fang J (2015) miR-155 Regulates glioma cells invasion and chemosensitivity by p38 isforms in vitro. J Cell Biochem 116(7):1213–1221. 10.1002/jcb.25073 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu N, Jiang F, Han X, Li M, Chen W, Liu Q, Liao C, Lv Y (2018) MiRNA-155 promotes the invasion of colorectal cancer SW-480 cells through regulating the Wnt/beta-catenin. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 22(1):101–109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu D, Zhao D, Zhao Y, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Wen C (2019) Inhibition of microRNA-155 alleviates cognitive impairment in alzheimer’s disease and involvement of neuroinflammation. Curr Alzheimer Res 16(6):473–482. 10.2174/1567205016666190503145207 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Ramirez MA, Wu D, Pryce G, Simpson JE, Reijerkerk A, King-Robson J (2014) MicroRNA-155 negatively affects blood-brain barrier function during neuroinflammation. FASEB J 28(6):2551–2565. 10.1096/fj.13-248880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Louafi F, Martinez-Nunez RT, Sanchez-Elsner T (2010) MicroRNA-155 targets SMAD2 and modulates the response of macrophages to transforming growth factor-β. J Biol Chem 285(53):41328–41336 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu Y, Huang Z, Hua Y, Xiao G (2018) Minocycline promotes BDNF expression of N2a cells via inhibition of miR-155-mediated repression after oxygen-glucose deprivation and reoxygenation. Cell Mol Neurobiol 38(6):1305–1313. 10.1007/s10571-018-0599-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma S, Fan L, Li J, Zhang B, Yan Z (2020) Resveratrol promoted the M2 polarization of microglia and reduced neuroinflammation after cerebral ischemia by inhibiting miR-155. Int J Neurosci 130(8):817–825. 10.1080/00207454.2019.1707817 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maciak K, Dziedzic A, Miller E, Saluk-Bijak J (2021) miR-155 as an important regulator of multiple sclerosis pathogenesis. A Review Int J Mol Sci 22(9):4332. 10.3390/ijms22094332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manni I, Tunici P, Cirenei N, Albarosa R, Colombo BM, Roz L, Sacchi A, Piaggio G, Finocchiaro G (2002) Mxi1 inhibits the proliferation of U87 glioma cells through down-regulation of cyclin B1 gene expression. Br J Cancer 86(3):477–484. 10.1038/sj.bjc.6600065 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mantzavinos V, Alexiou A (2017) Biomarkers for Alzheimer’s disease diagnosis. Curr Alzheimer Res 14(11):1149–1154. 10.2174/1567205014666170203125942 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mogi M, Togari A, Kondo T, Mizuno Y, Komure O, Kuno S, Ichinose H, Nagatsu T (2000) Caspase activities and tumor necrosis factor receptor R1 (p55) level are elevated in the substantia nigra from parkinsonian brain. J Neural Transm (vienna) 107(3):335–341. 10.1007/s007020050028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadipour A, Abudayyak M (2021) Hippocampal toxicity of metal base nanoparticles. Is there a relationship between nanoparticles and psychiatric disorders? Rev Environ Health. 10.1515/reveh-2021-0006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohammadipour A, Haghir H, Ebrahimzadeh Bideskan A (2020) A link between nanoparticles and Parkinson’s disease. Which nanoparticles are most harmful? Rev Environ Health 35(4):545–556. 10.1515/reveh-2020-0043 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murugaiyan G, Beynon V, Mittal A, Joller N, Weiner HL (2011) Silencing microRNA-155 ameliorates experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Immunol 187(5):2213–2221. 10.4049/jimmunol.1003952 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nampoothiri SS, Krishnamurthy RG (2016) Commentary: targeted inhibition of miR-155 promotes post-stroke neovascularization and functional recovery. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets 15(4):372–374. 10.2174/187152731504160328163830 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nazari-Jahantigh M, Wei Y, Noels H, Akhtar S, Zhou Z, Koenen RR, Heyll K, Gremse F, Kiessling F, Grommes J (2012) MicroRNA-155 promotes atherosclerosis by repressing Bcl6 in macrophages. J Clin Investig 122(11):4190–4202 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen JA, Lau P, Maric D, Barker JL, Hudson LD (2009) Integrating microRNA and mRNA expression profiles of neuronal progenitors to identify regulatory networks underlying the onset of cortical neurogenesis. BMC Neurosci 10:98. 10.1186/1471-2202-10-98 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noorbakhsh F, Ellestad KK, Maingat F, Warren KG, Han MH, Steinman L, Baker GB, Power C (2011) Impaired neurosteroid synthesis in multiple sclerosis. Brain 134(Pt 9):2703–2721. 10.1093/brain/awr200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliveira SR, Dionísio PA, Correia Guedes L, Gonçalves N, Coelho M, Rosa MM, Amaral JD, Ferreira JJ, Rodrigues CMP (2020) Circulating inflammatory miRNAs associated with parkinson’s disease pathophysiology. Biomolecules 10(6):945. 10.3390/biom10060945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paraboschi EM, Soldà G, Gemmati D, Orioli E, Zeri G, Benedetti MD, Salviati A, Barizzone N, Leone M, Duga S, Asselta R (2011) Genetic association and altered gene expression of mir-155 in multiple sclerosis patients. Int J Mol Sci 12(12):8695–8712. 10.3390/ijms12128695 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasquinelli AE (2012) MicroRNAs and their targets: recognition, regulation and an emerging reciprocal relationship. Nat Rev Genet 13:271–282 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pegoraro V, Marozzo R, Angelini C (2020) MicroRNAs and HDAC4 protein expression in the skeletal muscle of ALS patients. Clin Neuropathol 39(3):105–114. 10.5414/NP301233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rana A, Musto AE (2018) The role of inflammation in the development of epilepsy. J Neuroinflammation 15(1):144. 10.1186/s12974-018-1192-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rastegar-Moghaddam SH, Mohammadipour A, Hosseini M, Bargi R, Ebrahimzadeh-Bideskan A (2019) Maternal exposure to atrazine induces the hippocampal cell apoptosis in mice offspring and impairs their learning and spatial memory. Toxin Reviews 38(4):298–306. 10.1080/15569543.2018.1466804 [Google Scholar]

- Recio C, Oguiza A, Lazaro I, Mallavia B, Egido J, Gomez-Guerrero C (2014) Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1-derived peptide inhibits Janus kinase/signal transducers and activators of transcription pathway and improves inflammation and atherosclerosis in diabetic mice. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 34(9):1953–1960. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.114.304144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rizzuti M, Filosa G, Melzi V, Calandriello L, Dioni L, Bollati V, Bresolin N, Comi GP, Barabino S, Nizzardo M (2018) MicroRNA expression analysis identifies a subset of downregulated miRNAs in ALS motor neuron progenitors. Sci Rep 8:1–12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu SK, Volinia S, Costinean S, Galasso M, Neinast R, Santhanam R, Parthun MR, Perrotti D, Marcucci G, Garzon R (2012) miR-155 targets histone deacetylase 4 (HDAC4) and impairs transcriptional activity of B-cell lymphoma 6 (BCL6) in the Eµ-miR-155 transgenic mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci 109(49):20047–20052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seddiki N, Brezar V, Ruffin N, Lévy Y, Swaminathan S (2014) Role of miR-155 in the regulation of lymphocyte immune function and disease. Immunology 142(1):32–38. 10.1111/imm.12227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snow WM, Albensi BC (2016) Neuronal gene targets of NF-κB and their dysregulation in alzheimer’s disease. Front Mol Neurosci 9:118. 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soria Lopez JA, González HM, Léger GC (2019) Alzheimer’s disease. Handb Clin Neurol 167:231–255. 10.1016/B978-0-12-804766-8.00013-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strebovsky J, Walker P, Lang R, Dalpke AH (2011) Suppressor of cytokine signaling 1 (SOCS1) limits NFkappaB signaling by decreasing p65 stability within the cell nucleus. FASEB J 25(3):863–874. 10.1096/fj.10-170597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun J, Shi H, Lai N, Liao K, Zhang S, Lu X (2014) Overexpression of microRNA-155 predicts poor prognosis in glioma patients. Med Oncol 31(4):911. 10.1007/s12032-014-0911-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L, Ji S, Xing J (2019) Inhibition of microRNA-155 alleviates neurological dysfunction following transient global ischemia and contribution of neuroinflammation and oxidative stress in the hippocampus. Curr Pharm Des 25(40):4310–4317. 10.2174/1381612825666190926162229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan Y, Yang J, Xiang K, Tan Q, Guo Q (2015) Suppression of microRNA-155 attenuates neuropathic pain by regulating SOCS1 signalling pathway. Neurochem Res 40(3):550–560. 10.1007/s11064-014-1500-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang B, Xiao B, Liu Z, Li N, Zhu ED, Li BS, Xie QH, Zhuang Y, Zou QM, Mao XH (2010) Identification of MyD88 as a novel target of miR-155, involved in negative regulation of Helicobacter pylori-induced inflammation. FEBS Lett 584(8):1481–1486 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tao Y, Ai R, Hao Y, Jiang L, Dan H, Ji N, Zeng X, Zhou Y, Chen Q (2019) Role of miR-155 in immune regulation and its relevance in oral lichen planus. Exp Ther Med 17(1):575–586. 10.3892/etm.2018.7019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarassishin L, Loudig O, Bauman A, Shafit-Zagardo B, Suh HS, Lee SC (2011) Interferon regulatory factor 3 inhibits astrocyte inflammatory gene expression through suppression of the pro-inflammatory miR-155 and miR-155*. Glia 59(12):1911–1922. 10.1002/glia.21233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thai TH, Calado DP, Casola S, Ansel KM, Xiao C, Xue Y, Murphy A, Frendewey D, Valenzuela D, Kutok JL, Schmidt-Supprian M, Rajewsky N, Yancopoulos G, Rao A, Rajewsky K (2007) Regulation of the germinal center response by microRNA-155. Science 316(5824):604–608. 10.1126/science.1141229 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thome AD, Harms AS, Volpicelli-Daley LA, Standaert DG (2016) microRNA-155 regulates alpha-synuclein-induced inflammatory responses in models of parkinson disease. J Neurosci 36(8):2383–2390. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.3900-15.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari S, Atluri V, Kaushik A, Yndart A, Nair M (2019) Alzheimer’s disease: pathogenesis, diagnostics, and therapeutics. Int J Nanomedicine 14:5541–5554. 10.2147/IJN.S200490 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tonacci A, Bagnato G, Pandolfo G, Billeci L, Sansone F, Conte R, Gangemi S (2019) MicroRNA cross-involvement in autism spectrum disorders and atopic dermatitis: a literature review. J Clin Med 8(1):88. 10.3390/jcm8010088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trotta R, Chen L, Ciarlariello D, Josyula S, Mao C, Costinean S, Yu L, Butchar JP, Tridandapani S, Croce CM (2012) miR-155 regulates IFN-γ production in natural killer cells. Blood J Am Soc Hematol 119(15):3478–3485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valerio A, Boroni F, Benarese M, Sarnico I, Ghisi V, Bresciani LG, Ferrario M, Borsani G, Spano P, Pizzi M (2006) NF-kappaB pathway: a target for preventing beta-amyloid (Abeta)-induced neuronal damage and Abeta42 production. Eur J Neurosci 23(7):1711–1720. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.04722.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Viviani B, Bartesaghi S, Gardoni F, Vezzani A, Behrens MM, Bartfai T, Binaglia M, Corsini E, Di Luca M, Galli CL, Marinovich M (2003) Interleukin-1beta enhances NMDA receptor-mediated intracellular calcium increase through activation of the Src family of kinases. J Neurosci 23(25):8692–8700. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-25-08692.2003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Zhao Y, Zhang X, Badie H, Zhou Y, Mu Y (2013) Loss of sorting nexin 27 contributes to excitatory synaptic dysfunction by modulating glutamate receptor recycling in Down’s syndrome. Nat Med 19(4):473–480. 10.1038/nm.3117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang L, Zhang H, Rodriguez S, Cao L, Parish J, Mumaw C, Zollman A, Kamoka MM, Mu J, Chen DZ (2014a) Notch-dependent repression of miR-155 in the bone marrow niche regulates hematopoiesis in an NF-κB-dependent manner. Cell Stem Cell 15(1):51–65 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X, Huang T, Zhao Y, Zheng Q, Thompson RC, Bu G, Zhang YW, Hong W, Xu H (2014b) Sorting nexin 27 regulates Aβ production through modulating γ-secretase activity. Cell Rep 9(3):1023–1033. 10.1016/j.celrep.2014.09.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D, Tang M, Zong P, Liu H, Zhang T, Liu Y, Zhao Y (2018) MiRNA-155 regulates the Th17/Treg ratio by targeting SOCS1 in severe acute pancreatitis. Front Physiol 9:686 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wen Y, Zhang X, Dong L, Zhao J, Zhang C, Zhu C (2014) Acetylbritannilactone modulates MicroRNA-155-mediated inflammatory response in ischemic cerebral tissues. Mol Med 21(1):197–209. 10.2119/molmed.2014.00199 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodbury ME, Freilich RW, Cheng CJ, Asai H, Ikezu S, Boucher JD, Slack F, Ikezu T (2015) miR-155 is essential for inflammation-induced hippocampal neurogenic dysfunction. J Neurosci 35(26):9764–9781. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.4790-14.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu S, Xie DL, Dai XY (2019) Down-regulation of miR-155 promotes apoptosis of nasopharyngeal carcinoma CNE-1 cells by targeting PI3K/AKT-FOXO3a signaling. Eur Rev Med Pharmacol Sci 23(17):7391–7398. 10.26355/eurrev_201909_18847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xing G, Luo Z, Zhong C, Pan X, Xu X (2016) Influence of miR-155 on cell apoptosis in rats with ischemic stroke: role of the Ras Homolog Enriched in Brain (Rheb)/mTOR pathway. Med Sci Monit 22:5141–5153. 10.12659/msm.898980 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu C, Ren G, Cao G, Chen Q, Shou P, Zheng C, Du L, Han X, Jiang M, Yang Q (2013) miR-155 regulates immune modulatory properties of mesenchymal stem cells by targeting TAK1-binding protein 2. J Biol Chem 288(16):11074–11079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Z, Che S, Wang J, Jiao Y, Wang C, Meng Q (2015) miR-155 contributes to the progression of glioma by enhancing Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Tumour Biol 36(7):5323–5331. 10.1007/s13277-015-3193-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Li C, Liang F, Fan Y, Zhang S (2017) MiRNA-155 promotes proliferation by targeting caudal-type homeobox 1 (CDX1) in glioma cells. Biomed Pharmacother 95:1759–1764. 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang L, Liu L, Ying H, Yu Y, Zhang D, Deng H, Zhang H, Chai J (2018) Acute downregulation of miR-155 leads to a reduced collagen synthesis through attenuating macrophages inflammatory factor secretion by targeting SHIP1. J Mol Histol 49(2):165–174. 10.1007/s10735-018-9756-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yi J, Wang D, Niu X, Hu J, Zhou Y, Li Z (2015) MicroRNA-155 deficiency suppresses Th17 cell differentiation and improves locomotor recovery after spinal cord injury. Scand J Immunol 81(5):284–290. 10.1111/sji.12276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ysrafil Y, Astuti I, Anwar SL, Martien R, Sumadi FAN, Wardhana T, Haryana SM (2020) MicroRNA-155-5p diminishes in vitro ovarian cancer cell viability by targeting HIF1α expression. Adv Pharm Bulletin 10(4):630 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang J, Cheng Y, Cui W, Li M, Li B, Guo L (2014) MicroRNA-155 modulates Th1 and Th17 cell differentiation and is associated with multiple sclerosis and experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol 266(1–2):56–63. 10.1016/j.jneuroim.2013.09.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Wang L, Pang X, Zhang J, Guan Y (2019) Role of microRNA-155 in modifying neuroinflammation and γ-aminobutyric acid transporters in specific central regions after post-ischaemic seizures. J Cell Mol Med 23(8):5017–5024. 10.1111/jcmm.14358 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Li X, Tang Y, Chen C, Jing R, Liu T (2020a) miR-155-5p implicates in the pathogenesis of renal fibrosis via targeting SOCS1 and SOCS6. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2020:1–11. 10.1155/2020/6263921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang W, Wang L, Wang R, Duan Z, Wang H (2020b) A blockade of microRNA-155 signal pathway has a beneficial effect on neural injury after intracerebral haemorrhage via reduction in neuroinflammation and oxidative stress. Arch Physiol Biochem 15:1–7. 10.1080/13813455.2020.1764047 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng X, Huang H, Liu J, Li M, Liu M, Luo T (2018) Propofol attenuates inflammatory response in LPS-activated microglia by regulating the miR-155/SOCS1 pathway. Inflammation 41(1):11–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou J, Wang W, Gao Z, Peng X, Chen X, Chen W (2013) MicroRNA-155 promotes glioma cell proliferation via the regulation of MXI1. PLoS ONE. 10.1371/journal.pone.0083055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.