Abstract

Introduction

There are a lack of data describing outcomes and follow-up after hospital discharge for patients with newly diagnosed cirrhosis with complication on index admission. This study examines factors that influence outcomes such as readmission, follow-up, and mortality for patients with newly diagnosed cirrhosis.

Methods

We conducted a single-center retrospective chart review study of 230 patients with newly diagnosed cirrhosis from January 1st, 2020 through December 31st, 2021. We obtained demographics, clinical diagnoses, admission, and discharge MELD-Na, disposition, mortality, appointment requests rate, appointment show rate, and readmission.

Results

The primary complications on admission were GI bleed (27%), ascites (25.7%), and hepatic encephalopathy (HE) (10.4%). Overall, the median length of stay (LOS) was 6 days, and the readmission rate was 27%. Out of 230 patients, 25 (10.9%) patients died while hospitalized while another 43 (18.6%) died after initial discharge within the two-year study period. Although there was a significant reduction of the MELD-Na from admission to discharge (p < 0.05), admission MELD-Na did not correlate with LOS and discharge MELD-Na did not predict readmission. Patients with HE had the highest median LOS, while patients with ascites had the highest readmission rate. The median time to an appointment was 32 days. When comparing discharge destinations, most patients were discharged to home (63%), to facilities (13.9%), or expired (10.9%). The average appointment show rate was 38.5%, although 70% of patients had appointment requests. Readmission rate and mortality did not differ based on appointment requests. No significant differences in outcomes were observed based on race, sex, or insurance status.

Conclusion

New diagnosis of decompensated was found to have high mortality and high readmission rates. Higher MELD-Na score was seen in patients who died within 30 days. Routine appointment requests did not significantly improve readmission, mortality, increase appointment show rate, or decrease time to appointment. A comprehensive and specialized hepatology-specific program may have great benefits after cirrhotic decompensation, especially for those with newly diagnosed cirrhosis.

Keywords: Newly decompensated cirrhosis, Post-discharge outcomes, Predictive factors, Outpatient follow-up

Introduction

Decompensated cirrhosis (DC) is associated with a high mortality, readmission, and healthcare utilization with an estimated annual cost of $4.5 billion dollars [1]. Several studies have investigated factors associated with discharge outcomes for patients with DC. For example, inpatient frailty status was independently associated with higher risk of facility discharge and mortality [2]. Prediction models for 30- and 90-day readmission and mortality have limited accuracy beyond the MELD-Na score, highlighting the need for further research into the factors that may influence discharge outcomes for patients with DC [3].

Despite these efforts, no studies have specifically focused on hospitalized patients with newly diagnosed cirrhosis with decompensation on index admission and post-hospital outcomes in care transition and follow-up. This knowledge gap is crucial because half of all cirrhosis patients experience complications during initial hospitalization [4]. More importantly, the impact of discharge destination in this clinical setting is not well established. Patients with poor healthcare access and health literacy may utilize acute care services more frequently than outpatient services, potentially impacting their long-term outcomes. Thus, the premier hospitalization and discharge serves as a unique opportunity for promoting follow-up and decreasing readmissions. Identifying care gaps in this setting can give insight to the development of effective strategies for improving patient care and outcomes in this population. This study aims to examine factors that influence discharge outcomes and practice patterns for patients with newly diagnosed cirrhosis hospitalized with complications.

Methods

We conducted a retrospective chart review of 297 patients with newly diagnosed cirrhosis with complication, admitted between January 1st, 2020 and December 31st, 2021, at Temple University Hospital. We included patients aged 18 and above, who were in the inpatient setting and never diagnosed with cirrhosis prior to admission. Patients with pregnancy, an established diagnosis of cirrhosis, or required scheduled dialysis were excluded. Patients diagnosed in the outpatient setting were also excluded. We queried our electronic health record for relevant ICD-10 codes (I85.0, I86.4, I98.20, I98.3, K721, K729, K76.6, K76.7, F10.11, E11.22, E11.69, Z79.4, E11.21, E11.22, E11.65). Competing diagnoses such as acute hepatitis were also assessed. After manual chart review, only 230 confirmed patients out of the initial 297 were included for data analysis. Demographic, diagnoses, co-morbid conditions, clinical outcomes, discharge disposition, and readmission information were obtained and manually reviewed by investigators. MELD-Na scores were calculated on admission and on day of discharge. Data on appointment requests and subsequent follow-up with hepatology were collected. The main outcomes of interest include length of stay (LOS), overall mortality, outpatient follow-up rate, and 30-d readmission rate.

Results

General Characteristics

230 patients were included in our study. Of these patients, the median age was 58; 140 patients (60.8%) were male, with 23.5% identified as Caucasian Whites, 33.9% African American, and 34.8% Hispanics. Most patients have primary Medicaid (52.6%) and Medicare (32.6%). With regards to cirrhosis etiology, 45.7% was alcohol related, 16.1% was HCV related, 17.0% was both alcohol and HCV, 6.5% was from NASH, and 4.3% was autoimmune. The complications on admission included ascites (43.5%), acute blood loss anemia (defined as variceal bleeding or gastrointestinal bleeding from portal hypertensive gastropathy) (37.4%), hepatic encephalopathy (HE) (24.8%), and other (11.3%). Other complications included hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC), hyponatremia, hepatorenal syndrome (HRS), coagulopathy, and anasarca. Patients may have multiple complications on admission. Out of 100 patients with ascites, 13 of which presented with spontaneous bacterial peritonitis. Other medical comorbidities include type 2 diabetes mellitus (33.9%), chronic kidney disease (10.0%), substance use disorder (8.3%), and HIV (3.9%). Table 1 summarizes the results.

Table 1.

Demographics and outcomes of patients admitted with newly diagnosed cirrhosis with decompensation on admission

| Demographics and Summary | N = 230 |

|---|---|

| Age (median, range) | 58 (26–86) |

| Sex, male (n, %) | 140 (60.8%) |

| Race (n, %) | |

| White/Caucasian | 54 (23.5%) |

| Black/African American | 77 (33.9%) |

| Hispanics | 80 (34.8%) |

| Other | 19 (8.3%) |

| Insurance type (n, %) | |

| Medicare | 75 (32.6%) |

| Medicaid/medical assistance | 121 (52.6%) |

| Commercial | 19 (8.3%) |

| Uninsured | 15 (6.5%) |

| Etiologies of cirrhosis (n, %) | |

| Alcohol | 105 (45.7%) |

| Alcohol + HCV | 39 (17.0%) |

| HCV | 37(16.1%) |

| NASH | 15 (6.5%) |

| Unknown | 24 (10.4%) |

| Autoimmune | 10 (4.3%) |

| Chronic medical conditions (n, %) | |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 78 (33.9%) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 23 (10.0%) |

| Substance use | 19 (8.3%) |

| Human immunodeficiency virus | 9 (3.9%) |

| MELD-Na on admission (median) | 21 |

| MELD-Na at discharge (median) | 18 |

| Complications of cirrhosis* (n, %) | |

| Ascites (including SBP) | 100 (43.5%) |

| Acute gastrointestinal bleed | 86 (37.4%) |

| Hepatic encephalopathy | 57 (24.8%) |

| Other | 26 (11.3%) |

| Discharge disposition (n, %) | |

| Home | 145 (63.0%) |

| Facility | 32 (13.9%) |

| Expired | 25 (10.9%) |

| Hospice (home or inpatient) | 13 (5.6%) |

| Self-discharge (against medical advice) | 10 (4.3%) |

| Another hospital | 5 (2.2%) |

| Length of stay (median, range) | 6 (1–56) |

| 30-day readmission (n, %) | 61 (26.5%) |

| Overall death (n, %) | 68 (29.5%) |

| Orthotopic liver transplantation (n, %) | 6 (2.6%) |

| Hepatology clinic appointment request (n, %) | 147 (63.9%) |

HCV Hepatitis c virus, NASH non-alcoholic steatohepatitis, MELD model for end-stage liver disease

*One patient may have multiple complications

General Outcomes and Non-health-related Factors

For patients hospitalized with new diagnosis of DC, 26.5% were readmitted within 30 days, with median LOS of 6 days, appointment request rate of 64%, and overall inpatient death as 10.9%. Out of 61 patients readmitted, 13 of which continued to use alcohol, while 20 patients discontinued alcohol use. We found that 10 (4.3%) patients had premature discharges or incomplete treatment. Patients admitted with hepatic encephalopathy have the greatest median LOS at 9 days followed by ascites (6 days) and acute GI bleed (5 days). On the other hand, patients with ascites had the highest readmission rate (33%) followed by HE (28%) and acute GI bleed (23%), but this difference was not significant, p = 0.3. After discharge, patients with HE had the highest overall death rate (42%) followed by ascites (32%) and then acute GI bleed (22%), and this was significantly different p < 0.01. Out of 230 patients, 6 patients received an orthotopic liver transplantations during the time of their hospitalization.

Table 2 displays comparative analyses of non-health-related factors. Comparing males to females, we observed no significant difference for overall death rate (33% v 24%; p = 0.18) or in 30-d readmission rate (28% v 44%; p = 0.75). Males and females also had similar median LOS and appointment request rates. Next, comparing White and non-White counterpart, we observed no significant differences in overall death rate (20% v 32%; p = 0.12) or in 30-d readmission rate (32% v 28%; p = 0.59). Lastly, when comparing insurance status for patients with Medicaid or medical assistance insurance to their counterpart, we observed no significant differences in overall death rate (30% v 28%, p = 0.77) and 30-d readmission rate (24% v 29%, p = 0.37).

Table 2.

Association of mortality and readmission with race, sex, and insurance status

| Overall death (n, %) | p value | 30-day readmission (n, %) * | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | 46 (33%) | p = 0.18 | 35 (28%) | p = 0.75 |

| Female | 22 (24%) | 24 (44%) | ||

| White | 11 (20%) | p = 0.12 | 16 (32%) | p = 0.59 |

| Non-white | 57 (32%) | 43 (28%) | ||

| Medicaid/medical assistance | 37 (30%) | p = 0.77 | 29 (24%) | p = 0.37 |

| Non-medicaid/medical assistance | 31 (28%) | 32 (29%) |

MELD-Na Score Associates with Death Rather than LOS or Readmissions

We calculated each patient’s MELD-Na score on admission and on discharge and found a significant decrease between admission and discharge MELD-Na (21 vs 18, respectively, p < 0.05). Furthermore, there was no correlation between admission MELD-Na and overall length of stay and we observed no relationship between discharge MELD-Na and readmission. The median MELD-Na at discharge was significantly higher for those that died inpatient compared to those who died within 30 days after discharge (33 v 25; p < 0.001).

High Number of Overall Deaths with Bimodal Distribution

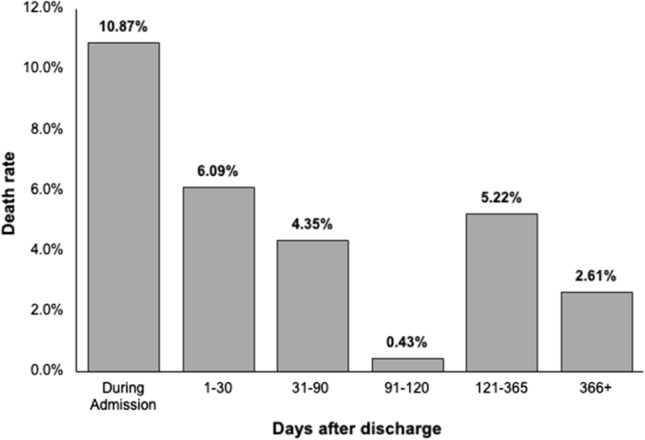

Next, we wish to examine the pattern of post-discharge deaths. Out of 230 patients, 25 (10.9%) patients died while hospitalized while another 43 (18.6%) died after initial discharge within the two-year study period. Inpatient deaths also included patients transitioned to hospice or comfort measure care. We observed a bimodal distribution with highest number of deaths occurring within 90 days after discharge, followed by a decrease, but rise again after 120 days (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Death distribution of patients since admission

Impact of Physician Practice Patterns and Disposition on Outcomes

To note, our inpatient hepatology consultation service operates every day and consultations are seen by housestaff and staffed by attendings within 24 h. In our study of patients hospitalized with newly diagnosed decompensated cirrhosis, we see a clear association that more consultations are requested with higher MELD-Na scores on admission. For patients with MELD-Na score < 15, consultations were requested 22% of the time. For MELD-Na 16–20, consultations were made 50% of the time, 21–25: 53% of the time, 26–30: 65% of the time, 31–35: 68% of the time, and for MELD-Na > 36 on admission, consultations were requested 94% of the time. In our subgroup analysis (Table 3), we excluded the 25 patients who experienced inpatient deaths as they would not require appointment requests. Of the remaining 205 patients, 147 (72%) had appointments requested prior to discharge and 58 (28%) did not have appointments requested prior to discharge. Despite appointment requests, the no-show rate was unexpectedly very high. Even after appointment requests, only 41% of those patients were able to attend that appointment. On the other hand, without appointment requests, only 29% of those patients followed up with hepatology clinic. Time to appointments after discharge was 32 days. Readmissions and overall death are similar regardless of whether appointments were requested after discharge. However, median survival seems to be higher when appointments were requested.

Table 3.

Association of discharge disposition with mortality, survival time, readmission, and follow-up

| Total n (%) | Outpatient hepatology follow-up (%) | From discharge to appointment (median days) | Readmission (%) | Overall death (%) | Median survival after discharge (days) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Appointment request | 147 (72%) | 61 (41%) | 32 | 46 (31%) | 30 (20%) | 139 |

| No appointment request | 58 (28%) | 17 (29%) | 17 | 13 (22%) | 13 (22%) | 94 |

| Home discharge | 145 (63%) | 64 (44%) | 53 | 41 (28%) | 29 (20%) | 116 |

| Facility discharge | 32 (14%) | 14 (12%) | 26 | 10 (31%) | 11 (34%) | 25 |

When comparing discharge destinations, most patients were discharged to home (63%), to facilities (13.9%), or expired (10.9%). Patients who were discharged home had a longer time to appointment (53 days v 26 days) but overall higher follow-up rates (44% v 12%). Readmission and death rates are similar between home discharges and facility discharges, but longer overall survival in non-facility discharges.

Discussion

This study aimed to understand discharge outcomes for patients hospitalized with newly diagnosed cirrhosis on index admission and the impact of clinical and nonclinical factors. This is the first study to specifically focus on this population to shed light on effective strategies for improving patient care and outcomes in vulnerable patients with new cirrhosis diagnosis.

First, our study found no significant differences between sex, race, and insurance status. Previous studies found that male sex was slightly associated with higher inpatient mortality and lower readmission rates [1, 5]. Similar safety net hospital experiences reported that race was not a predictive factor for mortality, which corroborates with our findings. [6]

Upon discharge, MELD-Na significantly decreased compared to admission MELD-Na and the discharge MELD-Na correlated with survival after discharge. That is, patients with inpatient death or death with 30 days of discharge have the highest MELD-Na scores. However, there was no observable difference in MELD-Na between those readmitted within 30 days and those without 30-d readmissions. Some studies suggested an association between readmission and MELD-Na greater than 15 [5]. The discrepancy with our data may be due to our selectivity of only hospitalized patients with a new diagnosis of cirrhosis rather than all patients with DC. It may be possible that new patients are more likely to be readmitted due to the acuity of their conditions regardless of their MELD-Na score, as our median MELD-Na score on discharge was 18.

Next, based on our subgroup comparisons, readmission rates appeared to be the lowest for patients admitted for acute GI bleed and highest for those admitted with ascites. Interestingly, HE made up the greatest proportion of death, followed by ascites and acute GI bleed. Mukthinuthalapati et al. previously found lower readmission rates for those admitted for a GI bleed at a safety net hospital, which is consistent with our report [6]. High readmission rate in patients with HE is possibly related to concomitant complications, such as nutritional deficiency, cognitive decline, and consequently higher frailty [2]. Additionally, it is likely that inadequate social support and lack of understanding of their disease state contributes to higher readmission as well [7]. Taken together, we believe that patients with HE, in particular, should be offered home services, maximizing family support with close follow-up to outpatient care, to reduce the risk of readmissions and death. Next, we did not find an impact of appointment requests on readmission rates or death rates. Furthermore, readmission and death were similar between facility and home discharges. However, there is a difference in median survival when discharged to facilities. We can only speculate on the reasons for this finding. It may be due to the fact that patients discharged to facilities were intrinsically frailer and physically deconditioned, or they are more medically complex. It is evident based on our data that neither routine appointment request upon discharge nor facility discharge resulted in meaningful improvement in outcomes for this particular patient population. This indicates that a more targeted intervention may be more beneficial to those with new diagnosis of cirrhosis. For example, a small 2013 study found patients with HE had improved outcomes when they were offered entry to a program that addresses their chronic social and medical issues [8]. Larger studies targeting specific disease groups have been done for both heart failure and COPD. For instance, post-discharge support for COPD patients, including home visits, phone calls, and education, effectively reduced 30-day and 180-day readmission rates [9]. Similarly, early follow-up within 14 days of discharge after a heart failure hospitalization significantly reduced the risk of death or hospitalization within 30 days (6%) and death or hospitalization or emergency department visit within 30 days (14%) [10]. These studies indicate that early and frequent follow-up with hepatology can likely improve patient outcomes following a cirrhosis diagnosis or decompensation. This can be extrapolated from our data as well. The median appointment time is beyond 30 days after discharge. This appointment delay competes with mortality and readmissions. Given that our patients with new cirrhosis experienced high mortality within 30 and 90 days, future interventions will need to reduce the median appointment time closer to 14 days. Furthermore, social resources and community outreach must be considered to counter the high no-show rate as seen in our data.

Given success of other specialized rehabilitation programs, we suspect that the utility of a comprehensive and specialized hepatology-specific program would have great benefits after cirrhotic decompensation, especially for those with newly diagnosed cirrhosis. Routine appointment request alone is not sufficient to improve patient outcomes.

Our study is subject to several limitations. Firstly, it relied on a retrospective review of data. Although efforts were made to verify data through manual chart review, there remains a possibility of misinterpretation by the original note writer, data collector, or coder. Consequently, there may have been instances where patients were incorrectly included in our study. However, it is unlikely that errors occurred in discharge and readmission outcomes, as these are crucial for medical billing and are often documented in multiple notes. This also applies to the calculation of MELD-Na scores. Additionally, our study may not have captured individuals who sought follow-up care at outside health systems, as our data query was limited to our own institution. However, we believe that the majority of readmissions and mortality events were captured, given that most of our patients receive follow-up care within our safety net hospital. Furthermore, it is important to acknowledge that our experiences may differ from those of non-safety net hospitals, as we serve a particularly underserved population. Moreover, our study only included new patients hospitalized with decompensated cirrhosis. While this fills an important gap in the literature and offer new insights, it may limit the generalizability of our findings. Findings of this study may not be extrapolated to the outpatient settings. These limitations should be taken into consideration when interpreting the results of our study.

Conclusion

In summary, our study underscores the importance of considering various factors in the discharge outcomes of patients with newly diagnosed cirrhosis. While we found no disparities based on sex, race, or insurance status, MELD-Na scores at discharge correlated significantly with post-discharge survival. However, we did not observe a clear link between MELD-Na scores and readmission rates, suggesting the complexity of factors influencing readmissions. Tailored interventions, especially for complications like hepatic encephalopathy, could improve outcomes. Optimizing post-discharge care, including reducing appointment delays and enhancing social support, is crucial to mitigate high mortality and readmission rates. Despite limitations, our study provides insights for future research and intervention development in this patient population.

Author’s contribution

AI designed the study, collected and analyzed data, performed literature review, and wrote the manuscript. RF conducted chart review, analyzed data, performed literature review, and made table/figures. AG conducted chart review, analyzed data, performed literature review, and made table/figures. HY designed the study, collected and analyzed data, and supervised the study and wrote manuscript for intellectual content.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

All authors declared no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Radadiya D, Devani K, Dziadkowiec KN, Reddy C, Rockey DC. Improved mortality but increased economic burden of disease in compensated and decompensated cirrhosis: a US national perspective. J Clin Gastroenterol 2023;57:300–310. 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Serper M, Tao SY, Kent DS et al. Inpatient Frailty Assessment Is Feasible and Predicts Nonhome Discharge and Mortality in Decompensated Cirrhosis. Liver Transplantation 2021;27:1711–1722. 10.1002/lt.26100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu C, Anjur V, Saboo K et al. Low predictability of readmissions and death using machine learning in cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2021;116:336–346. 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000971. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Volk ML, Tocco RS, Bazick J et al. Hospital readmissions among patients with decompensated cirrhosis. Am J Gastroenterol 2012;107:247–252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Morales BP, Planas R, Bartoli R et al. Early hospital readmission in decompensated cirrhosis: Incidence, impact on mortality, and predictive factors. Dig Liver Dis 2017;49:903–909. 10.1016/j.dld.2017.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mukthinuthalapati VVPK, Akinyeye S, Fricker ZP et al. Early predictors of outcomes of hospitalization for cirrhosis and assessment of the impact of race and ethnicity at safety-net hospitals. PLoS One 2019;14:e0211811. 10.1371/journal.pone.0211811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gaspar R, Rodrigues S, Silva M et al. Predictive models of mortality and hospital readmission of patients with decompensated liver cirrhosis. Dig Liver Dis 2019;51:1423–1429. 10.1016/j.dld.2019.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Andersen MM, Aunt S, Jensen NM et al. Rehabilitation for cirrhotic patients discharged after hepatic encephalopathy improves survival. Dan Med J 2013;60:A4683. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pedersen PU, Ersgard KB, Soerensen TB, Larsen P. Effectiveness of structured planned post discharge support to patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease for reducing readmission rates: a systematic review. JBI Database Syst Rev Implement Rep 2017;15:2060–2086. 10.11124/JBISRIR-2016-003045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mcalister FA, Youngson E, Kaul P, Ezekowitz JA. Early follow-up after a heart failure exacerbation. Circ: Heart Fail. 2016. 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.116.003194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analyzed during the current study.