Abstract

Background:

Siganidae is a marine teleost family consisting of a single extant genus, Siganus Forsskål, 1775, which included 29 recognized species of rabbitfish.

Aim:

The main goal of this study was the use of the mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene as a potential molecular marker in the phylogenetic relationships study of some rabbitfishes species (Siganidae: Perciformes).

Methods:

The samples were gathered from the Red Sea. The sequences of four rabbitfishes (Siganus argenteus, Siganus luridus, Siganus rivulatus, and Siganus stellatus) were deposited into NCBI to gain the accession numbers (PP488874–PP488877) and then analyzed with their related rabbitfishes depending on available sequence data of the mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene.

Results:

The results of 16S rRNA sequences illustrated that the average A+T values were greater than C+G.

Conclusion:

The low genetic distance between S. luridus and Siganus rivulatus indicated a close linkage between them.

Keywords: Mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene, Molecular marker, Rabbitfishes

Introduction

With 27 species, siganids, or “rabbit fishes,” are a small family of marine herbivorous fish known as is widely spread throughout the tropical waters of the Indian Ocean, Red Sea, and Indo-Pacific (Woodland, 1983; Saoud et al., 2008). Moreover, subtropical Mediterranean locations have been reported to harbor these fish (Saoud et al., 2008; Insacco and Zava, 2016). A large range of salinity and temperature were tolerable to siganidas (Woodland, 1983; Saoud et al., 2007). In terms of growth, siganida grows similarly to other marine organisms that are cultivated. Its maximum weight and length are 318.2 g and 32 cm, respectively (Bariche, 2005).

It is challenging to accurately identify fish and infer the evolutionary relationships among species based on their morphology in many taxonomic groups that are distributed around the world. This is because species that are descended from convergent evolution share comparable morphological traits, and the pattern of speciation is highly complex (Rice and Westneat, 2005; Duftner et al., 2007).

Nowadays, it is thought that molecular marker-derived genetic information is crucial for the sustainable management, exploitation, and conservation of fisheries and animals as well as for promoting sustainable aquaculture (Casey et al., 2016; Lind et al., 2016).

Species characterization using morphology and anatomical characters causes sometimes errors in the proper identification of closely related species. Because of these issues, molecular markers have been used as a complementary tool for taxonomic identification (AL-Qurashi and Saad, 2022).

To comprehend biodiversity assessments, conservation management, evolutionary patterns, and processes, accurate species delimitation, and phylogenetic reconstruction are essential (Traldi et al., 2020; McCord et al., 2021).

Fish species identification, fish resource management, and seafood monitoring are all performed achievable by mitochondrial DNA (Teletchea, 2009; Rubinoff et al., 2006).

The mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene was used for molecular phylogenetic research in several fish species (Li et al., 2013). Because these genes are preserved and non-coding, they were crucial in establishing phylogenetic relationships (Rathipriya et al., 2022).

The basic goal of this work was to evaluate the phylogenetic linkages of some species of rabbitfishes belonging to the family Siganidae by the mean of large mitochondrial rRNA (16S rRNA) gene.

Materials And Methods

Samples collection and species identification

The study sampling site was the Red Sea, where four species of family Siganidae (Siganus argenteus, Siganus luridus, Siganus stellatus, and Siganus rivulatus) were compiled and identified. In order to isolate DNA, the sample muscles were taken out and preserved at –20°C

DNA isolation, and PCR amplification

Using the DNA Mini kit (Qiagen, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions, the genomic DNA was extracted from the conserved muscles. Using previously published primers, PCR was utilized to amplify a partial sequence of the mitochondrial 16S rRNA (Simon et al., 1991). Using 23 μL of 2X master mix, 1 μL of genomic DNA, 1 μL of each primer, and 20 μL of nuclease-free water, the PCR was finished in 46 μL. The amplification conditions included five minutes of denaturation at 95°C, thirty cycles of denaturation, annealing, and extension at 94°C, 48°C, and 72°C, respectively, for sixty seconds, and a final extension at 72°C for seven minutes. On a 1.5% agarose gel containing ethidium bromide and a 100 bp DNA ladder, the PCR results were electrophoresed.

Sequences and phylogenetic analysis

The final sequences were finished by Macrogen (South Korea, Seoul). In order to obtain accession numbers, the 16S rRNA sequences were deposited into GenBank/NCBI. The sequences were aligned using CLUSTAL W (Thompson et al., 1994), using the default parameters. Using MEGA software version 7.0 (Kumar et al., 2016), two approaches were used for phylogenetic reconstructions: neighbor joining and minimum evolution. We employed 1,000 bootstrap iterations of Kimura two-parameter distances (Kimura, 1980) to finalize the sequence divergences (Felsenstein, 1985).

Results

This work establishes the evolutionary lineages of four species of the family Siganidae: S. argenteus, S. luridus, S. stellatus, and S. rivulatus. This was achieved by employing large subunit ribosomal RNA (16S rRNA) sequences.

In all four species, the 16S rRNA-produced bands range in length from 521 to 570 bp. The 16S rRNA sequences were shown in GenBank/NCBI to obtain the accession numbers (PP488874––PP488877). The findings show that S. argenteus and S. rivulatus possess the shortest sequence (521 bp.) while S. stellatus possesses the sequence with the greatest length (570 bp.). Adenine (A), thymine (T), cytosine (C), and guanine (G) exhibited average frequencies of 28,63, 22.72, 25, and 23.65%, respectively. As was shown in Table 1, the average attribution for A+T was more significant compared to that of C+G. The final alignments comprised 589 base pairs. The sites that were variable, and conserved were 17 and 534, respectively.

Table 1. Accession number, nucleotide frequencies, A+T contents, and their averages of (16S rRNA) sequence in four species of the family Siganidae.

| No. | Species | Accession number | Base pair length | Nucleotide frequencies % | A+T Content (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A% | T% | C % | G% | |||||

| 1 | S. argenteus | PP488874.1 | 521 | 29.37 | 22.46 | 24.56 | 23.61 | 51.83 |

| 2 | S. luridus | PP488875.1 | 540 | 27.78 | 22.41 | 25.74 | 24.07 | 50.19 |

| 3 | S. stellatus | PP488876.1 | 570 | 28.95 | 23.51 | 24.21 | 23.33 | 52.46 |

| 4 | S. rivulatus | PP488877.1 | 521 | 28.41 | 22.46 | 25.52 | 23.61 | 50.87 |

| Average % | - | 538 | 28.63 | 22.72 | 25 | 23.65 | 51.35 | |

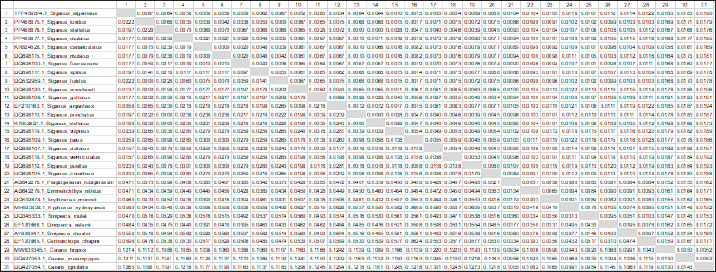

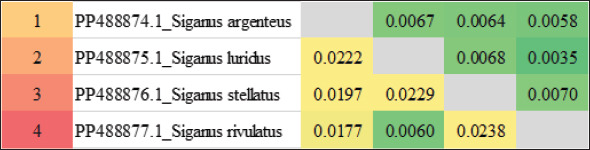

The P-distances across the entire fish fluctuated between 0.0000 and 0.0197%. The distance value was 0.05% overall. The P-distances among the Siganus species ranged from 0.0000 to 0.0082%. The largest value (0.0082) was found between _Siganus_javus and both Siganus canaliculatus and S. rivulatus (DQ898115.1). The smallest value (0.0000) was found between Siganus_canaliculatus and S. rivulatus (DQ898115.1) as well as understudied S. stellatus and both S. stellatus (KT952627.1) and Siganus punctatus. The P-distances among the studied species of Siganus spanned the range from 0.0035 to 0.0070%. The largest difference (0.0070) was observed between S. stellatus, and S. rivulatus. Conversely, S. luridus and S. rivulatus had the smallest P-distance (0.0000) (Table 2 and Fig. 1).

Table 2. Pairwise distances using 16S rRNA gene among four species of the family Siganidae, and the outgroup.

Fig. 1. Heatmap visualization of The P-distances among four species of the family Siganidae by employed the 16S rRNA gene.

The sequences obtained from four fish in the Siganidae family, along with 24 linked sequences and the three out-group species from GenBank, were used in this work for widely combination phylogenetic investigation in order to finish the phylogenetic tree investigation using the sequence of 16S rRNA sequence. More than one phylogenetic technique was employed for the very illustrative phylogenetic analysis utilizing the 16S rRNA gene: Neighbor Joining and Minimum Evolution. Although the support rate varied slightly, the methods yielded results that were essentially comparable and highlighted two main points: (1) The outgroup species creating a distinct cluster. (2) Each species of the studied species creating a distinct cluster with the comparable species from GenBank (Figs. 2 and 3).

Fig. 2. Neighbour joining phylogenetic tree among four species of the family Siganidae, and the outgroup with the outgroup by employed the 16S rRNA gene.

Fig. 3. Minimum evolution phylogenetic tree among four species of the family Siganidae, and the outgroup with the outgroup by employed the 16S rRNA gene.

Discussion

It can be difficult to identify species in traditional taxonomy since there are often arbitrary morpho meristic data sets and a lack of guidelines for character selection or coding. Under certain circumstances, genetic analysis can be employed as a further way of establishing taxonomic identity (Basheer et al., 2015).

Due to its slower mutation rate and lower substitution rates than other mtDNA genes, mitochondrial 16S rRNA has been found to be valuable for studying species, populations, and families (Garland and Zimmer, 2002). Moreover, fish phylogenetic relationships can be estimated at both the species and generic levels using the 16S rRNA gene (Moyer, et al., 2004; Chakraborty and Iwatsuki, 2006). Therefore, in fish evolutionary studies, 16S rRNA is advised for the reconstruction of informative phylogenetic links and a proper identification system (Saad et al., 2019).

This study showed that the average bidder for the fish that were understudied was (A+T) rather than (C+G). This aligned with multiple research investigations. In contrast to C+G, the entire 16S rRNA gene displays A+T affluence, according to Bo et al. (2013). Basheer et al. (2015) found that 16S rRNA had a lower C+G value than A+T in their investigation of Rastrelliger species. Additionally, Mar’ie and Allam (2019) discovered a greater A+T ratio than C+G in two puffer fish. In some species of catfish, Mahrous and Allam (2022) the proportion of A+T was greater than that of C+G.

The C+G concentration of the 16S rRNA gene varied between 48.52 and 50.09 in our data. The four species in the family Siganidae’s GC variety may indicate adaptation (Ali et al., 2021).

High levels of conservation were found in the final alignments of partial 16S rRNA sequences in the four species belonging to the Siganidae family. Using 16S rRNA aligned sequences, Basheer et al. (2015) discovered 575 consistent sites of 590 bp in three Rastrelliger species. Using a phylogenetic analysis of Cichlids and the 16S gene, Sokefun (2017) discovered 337 conserved sites comprising 463 bp of alignment. Numerous highly conserved regions are revealed by aligning the partial 16S rRNA sequences of eight Carangid fishes (Alyamani et al., 2023). The research done by Ramadan et al., (2023) showed that the four species of Lutjanus fish have an average (A+T) that is higher than the average (C+G).

According to (Kaleshkumar et al., 2015), strongly related species had low genetic distance values, whereas cases with great genetic divergence are caused by the highest genetic distance. The low genetic distance between S. luridus and S. rivulatus indicated a close linkage between them.

Acknowledgment

The author would like to thank the University of Jeddah.

Authors’ contributions

There is one author for this manuscript.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that there is no conflict of interest.

Funding

Not applicable.

Data availability

All data are provided in the manuscript.

References

- Ali F, Mamoon A, Abbas E. Mitochondrial-based phylogenetic inference of worldwide species of genus Siganus. Eg. J. Aqu. Bio. Fisheries. 2021;25:371–388. [Google Scholar]

- AL-Qurashi M, Saad Y. Utility of 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequence variations for inferencing evolutionary variations among some shrimp species. Eg. J.Aqu. Bio. Fisheries. 2022;26(4):1213–1225. [Google Scholar]

- Alyamani N.M, Fayad E, Abu Almaaty A.H, Ramadan A, Allam M. Phylogenetic relationships among some carangid species based on analysis of mitochondrial 16S rRNA Sequences. Eg. J. Aq. Bio. Fisheries. 2023;27(2):61–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bariche M. Age and growth of Lessepsian rabbitfish from the eastern Mediterranean. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 2005;21(2):141–145. [Google Scholar]

- Basheer V.S, Mohitha C, Vineesh N, Divya P.R, Gopalakrishnan A, Jena J.K. Molecular phylogenetics of three species of the genus Rastrelliger using mitochondrial DNA markers. Mol. Bio. Rep. 2015;42(4):873–879. doi: 10.1007/s11033-014-3710-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bo Z, Xu T, Wang R, Jin X, Sun Y. Complete mitochondrial genome of the Bombay duck Harpodon nehereus (aulopiformes, synodontidae) Mitochond. DNA. 2013;24(6):660–662. doi: 10.3109/19401736.2013.772988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casey J, Jardim E, Martinsohn J.T. The role of genetics in fisheries management under the E.U. common fisheries policy. J. Fish Bio. 2016;89:2755–2767. doi: 10.1111/jfb.13151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakraborty A, Iwatsuki Y. Genetic variation at the mitochondrial 16S rRNA gene among Trichiurus lepturus (Teleostei:Trichiuridae) from various localities: preliminary evidence of a new species from West Coast of Africa. Hydrobiologia. 2006;563(1):501–513. [Google Scholar]

- Duftner N, Sefc K.M, Koblmüller S, Salzburger W, Taborsky M, Sturmbauer C. Parallel evolution of facial stripe patterns in the Neolamprologus brichardi/pulcher species complex endemic to Lake Tanganyika. Mol. Phy. Evol. 2007;45(2):706–715. doi: 10.1016/j.ympev.2007.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Felsenstein J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: an approach using the bootstrap. Evol. Int. J. Organic Evo. 1985;39(4):783–791. doi: 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1985.tb00420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garland E.D, Zimmer C.A. Techniques for the identification of bivalve larvae. Marine Eco. Prog. Series. 2002;225:299–310. [Google Scholar]

- Insacco G, Zava B. First record of the Marbled spinefoot Siganus rivulatus Forsskål and Niebuhr, 1775 (Osteichthyes, Siganidae) in Italy. New Mediterranean Biodiv. Rec. 2016;2016:230–252. [Google Scholar]

- Kaleshkumar K, Rajaram R, Vinothkumar S, Ramalingam V, Meetei K.B. Note DNA barcoding of selected species of pufferfishes (Order : Tetraodontiformes ) of Puducherry coastal waters along south-east coast of India. Ind. J. Fisheries. 2015;62(2):98–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kimura M. A simple method for estimating evolutionary rates of base substitutions through comparative studies of nucleotide sequences. J. Mol. Evo. 1980;16(2):111–120. doi: 10.1007/BF01731581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S, Stecher G, Tamura K. MEGA7: molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 7.0 for bigger datasets. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2016;33(7):1870–1874. doi: 10.1093/molbev/msw054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y, Ren Z, Shedlockm A.M, Wu J, Sang L, Tersing T. High altitude adaptation of the schizothoracine fishes (Cyprinidae) revealed by the mitochondrial genome analysis. Gene. 2013;517:169–178. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2012.12.096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lind C.E, Brummett R.E, Ponzoni R.W. Exploitation and conservation of fish genetic resources in Africa: issues and priorities for aquaculture development and research. Rev. Aquacult. 2016;4(3):125–141. [Google Scholar]

- Mahrous N.S, Allam M. Phylogenetic relationships among some catfishes assessed by small and large mitochondrial rRNA sequences. Eg. J. Aq. Bio. Fisheries. 2022;26(6):1069–1082. [Google Scholar]

- Mar’ie Z.A, Allam M. molecular phylogenetic linkage for nile and marine puffer fishes using mitochondrial DNA sequences of Cytochrome b and 16S rRNA. Egyptian J. Aqu. Bio. Fisheries. 2019;23(5):67–80. [Google Scholar]

- McCord C.L, Nash C.M, Cooper W.J, Westneat M.W. Phylogeny of the damselfishes (Pomacentridae) and patterns of asymmetrical diversification in body size and feeding ecology. PLoS One. 2021;16(10):e0258889. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0258889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moyer G.R, Burr B.M, Krajewski C. Phylogenetic relationships of thorny catfishes (Siluriformes: Doradidae) inferred from molecular and morphological data. Zool. J. Linnean Soc. 2004;140(4):551–575. [Google Scholar]

- Ramadan A, Abu Almaaty A.H, Al-Tahr Z.M, Allam M. Phylogenetic diversity of some snappers (Lutjanidae: Perciformes) inferred from mitochondrial 16S rRNA sequences. Eg. J. Aqu. Bio. Fisheries. 2023;27(3):307–317. [Google Scholar]

- Rathipriya A, Kathirvelpandian A, Shanmugam S.A, Uma A, Suresh E, Felix N. Character-based diagnostic keys, molecular identification and phylogenetic relationships of fishes based on mitochondrial gene from Pulicat Lake, India: a tool for conservation and fishery management purposes. In. J. Ani. Res. 2022;56(8):933–940. [Google Scholar]

- Rice A.N, Westneat M.W. Coordination of feeding, locomotor and visual systems in parrotfishes (Teleostei: Labridae) J. Exp. Biol. 2005;208(18):3503–3518. doi: 10.1242/jeb.01779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubinoff D, Cameron S, Will K. A genomic perspective on the shortcomings of mitochondrial DNA for ‘barcoding’ identification. J. Hered. 2006;97:581–594. doi: 10.1093/jhered/esl036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saad Y, Abdulkader S.-O. and Gharbawi W. Evaluation of molecular diversity in some Red sea parrotfish species based on mitochondrial 16S ribosomal RNA gene sequence variations. Res. J. Biotech. 2019;14:30–38. [Google Scholar]

- Saoud I.P, Ghanawi J, Lebbos N. Effects of stocking density on the survival, growth, size variation and condition index of juvenile rabbitfish, Siganus rivulatus. Aquacult. Intern. 2008;16(2):109–116. [Google Scholar]

- Saoud I.P, Kreydiyyeh S, Chalfoun A, Fakih M. Influence of salinity on survival, growth, plasma osmolality and gill Na–K–ATPase activity in the rabbitfish Siganus rivulatus. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2007;348(1–2):183–190. [Google Scholar]

- Simon C, Franke A, Martin A. The polymerase chain reaction: DNA extraction and amplification. In: Hewitt G.M, Johnston A.W.B, Young J.P.W, editors. In Molecular techniques in taxonomy. Vol. 57. Eloudia, Greece: NATO AS1 Series H; 1991. pp. 329–355. [Google Scholar]

- Sokefun O.B. The cichlid 16S gene as a phylogenetic marker: limits of its resolution for analyzing global relationship. Intern. J. Gen. Mol. Bio. 2017;9(1):1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Teletchea F. Molecular identification methods of fish species: reassessment and possible applications. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2009;19:265–293. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J.D, Higgins D.G, Gibson T.J. CLUSTAL W: improving the sensitivity of progressive multiple sequence alignment through sequence weighting, position-specific gap penalties and weight matrix choice. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22(22):4673–4680. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.22.4673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Traldi J.B, Vicari M.R, de Fátima Martinez J, Blanco D.R, Lui R.L, Azambuja M, de Almeida R.B, de Cássia Malimpensa G, da Costa Silva G.J, Oliveira C, Pavanelli C.S, Filho O.M. Recent apareiodon species evolutionary divergence (Characiformes: Parodontidae) evidenced by chromosomal and molecular inference. Zoologischer. Anzeiger. 2020;289:166–176. [Google Scholar]

- Woodland D. Zoogeography of the Siganidae (Pisces): an interpretation of distribution and richness patterns. Bull. Mar. Sci. 1983;33:713–717. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data are provided in the manuscript.