Abstract

Field isolates of foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) are believed to use RGD-dependent integrins as cellular receptors in vivo. Using SW480 cell transfectants, we have recently established that one such integrin, αvβ6, functions as a receptor for FMDV. This integrin was shown to function as a receptor for virus attachment. However, it was not known if the αvβ6 receptor itself participated in the events that follow virus binding to the host cell. In the present study, we investigated the effects of various deletion mutations in the β6 cytoplasmic domain on infection. Our results show that although loss of the β6 cytoplasmic domain has little effect on virus binding, this domain is essential for infection, indicating a critical role in postattachment events. The importance of endosomal acidification in αvβ6-mediated infection was confirmed by experiments showing that infection could be blocked by concanamycin A, a specific inhibitor of the vacuolar ATPase.

Foot-and-mouth disease virus (FMDV) is one of the most infectious animal pathogens known. It causes a vesicular disease of cloven-hoofed animals, which spreads by aerosol, sometimes over long distances. The primary site of infection in cattle is the epithelium of the pharynx (47). It can be assumed that the pathology of foot-and-mouth disease and its ability to spread reflect processes at the cellular level concerning the choice of surface receptor and mechanism of infection.

FMDV is the type species of the Aphthovirus genus within the family Picornaviridae. The small nonenveloped virion consists of an 8.5-kb strand of RNA within an icosahedral capsid formed from 60 copies each of four proteins (VP1 to VP4). The virus infects cells by attaching to integrin receptors through a long surface loop, the G-H loop, of VP1 (28, 30, 31, 34, 35). The sequence of this loop contains the conserved tripeptide, Arg-Gly-Asp (RGD), which is characteristic of the ligands of several members of the integrin family (27). Some FMDVs can use heparan sulfate proteoglycans as alternative receptors, but this ability appears to be an adaptation to growth in cell culture, and there is no convincing evidence of a role for heparan sulfate in cell entry by field strains of FMDV (22, 29, 40, 46).

Integrins are a family of cell surface glycoproteins which function in a variety of adhesion and signaling phenomena (6, 16, 24, 27). Each molecule is composed of two large, type 1 transmembrane polypeptides, α and β, which, in most cases, have short cytoplasmic domains. To date, two species of RGD-binding integrin, αvβ3 and αvβ6, have been reported to mediate FMDV infection in cell culture (5, 31). Of the two, only αvβ6 is expressed in epithelial tissues, and this species is currently the most plausible receptor in the animal host (31). We recently reported that this integrin serves as an attachment receptor for FMDV, but we have no information on what part, if any, this integrin plays in subsequent events during infection (31). The work described in this paper was undertaken to elucidate the part played by αvβ6 in the events that follow virus attachment to the host cell.

For an infecting virion, the entry pathway culminates in the uncoating of the RNA genome and its transfer across a membrane into the cytosol. These processes are poorly understood for nonenveloped viruses, although it is clear that picornaviruses have evolved a variety of strategies for gaining entry to cells. For enteroviruses and the ICAM-1 receptor group of rhinoviruses, binding to the receptor triggers a profound structural transformation to the so-called altered or A particle, and this change is thought to be a prerequisite for release of the RNA (3, 11, 18, 21, 26, 42). For other picornaviruses, such as coxsackievirus A21 and certain enteroviruses that bind decay-accelerating factor, virus binding to the primary attachment receptor does not lead to formation of A-particles, instead A-particle formation is initiated by virus binding to a secondary or coreceptor (42, 43, 48). For FMDV, by contrast, there is no evidence for A-particle formation. Such a transformation would not be needed by a virus, like FMDV, that dissociates into pentamers, RNA, and VP4 at pH values just below neutrality (10, 14, 20). Instead, the virus is thought to enter endosomes, leading to capsid uncoating in the acidic environment of this compartment. Some evidence for this mechanism comes from the inhibitory effect of monensin (4) which raises endosomal pH. Capsid dissociation by some picornaviruses, such as the minor receptor group rhinoviruses, appears to involve aspects of both the enterovirus and FMDV pathways, since A-particle formation is triggered not by virus binding to its receptor but by acidic pH following virus uptake into endosomes (44). FMDV can thus be considered a simple model for endocytic cell entry by a nonenveloped virus. In the present study, we set out to determine what role αvβ6 plays during the postattachment phases of infection by FMDV by investigating the effects of deletions in the cytoplasmic domain of the β6 subunit. We chose this target because many of the functional properties of integrins, including the regulation of binding affinity, signal transduction, and integrin-mediated uptake of ligands, are dependent on the integrity of the cytoplasmic domain of the β-subunit (6, 8, 16, 24, 27, 41, 50, 55). Our data show that although the β6 cytoplasmic domain is not required for virus binding, this domain is essential for infection, indicating a critical role in postattachment events. In addition, we show that αvβ6-mediated infection is dependent on active endosomal acidification, implying that infection mediated by αvβ6 most likely proceeds through endosomes. Together, the results of these experiments are consistent with FMDV entering cells through receptor-mediated endocytosis and are discussed in relation to the normal cellular functions of the integrin β-subunit cytoplasmic domain.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and viruses.

BHK cells were cultured in Dulbecco's modified Eagle's medium (DMEM) supplemented with 5% fetal calf serum (FCS), 20 mM glutamine, penicillin (100 Système International d'Unités [SI] units/ml), and streptomycin (100 μg/ml). Construction of SW480 cell transfectants expressing wild-type αvβ6 or αvβ6 with deletions in the cytoplasmic domain of the β6-subunit has been described (1, 13, 38, 54). Transfectants were cultivated in DMEM supplemented with 10% FCS, 20 mM glutamine, penicillin (100 SI units/ml), streptomycin (100 μg/ml), and 1 mg of Geneticin (Life Technologies) per ml. Stocks of the non-heparin-binding FMDV strains O1Kcad2 and SAT-3 Zim4/81 (SAT-3) were propagated in primary bovine thyroid cells or BHK cells, respectively. The multiplicity of infection (MOI) was based on the virus titer on BHK cells. FMDV purification was done as described previously (15).

Antibodies, peptides, and reagents.

The sequence of the RGD peptide used in these studies was derived from the GH loop of VP1 of type O FMDV (142-VPNLRGDLQVLA-153). The antiintegrin antibodies used in these studies were P1F6 (anti-αvβ5), E7P6 (anti-αvβ6) (54), and 10D5 (anti-αvβ6) (25) all from Chemicon. The anti-FMDV monoclonal antibodies (MAbs) B2 and D9 (36), which recognize type O virus, were purified using protein A (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's instructions. Concanamycin A was purchased from FLUKA and stored at −20°C as a 10 mM stock in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO).

Infectious center assay.

Cells were harvested using 20 mM EDTA in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (pH 7.5), washed, and resuspended in cell culture media. One million cells were infected with SAT-3 (MOI = 1 PFU/cell) or with O1Kcad2 (MOI = 0.5) in 100 μl of DMEM supplemented with 1% FCS at 37°C for 1 h with continuous rotation. Following infection, virus that remained outside the cells was inactivated by the addition of 1 ml of 0.1 M citric acid buffer (pH 5.2) for 1 min. The cells were washed with PBS (pH 7.5) containing 2 mM CaCl2 and 1 mM MgCl2 and resuspended in 300 μl of the same buffer supplemented with 0.5% FCS. Dilutions of the infected cells (100 μl) were layered onto subconfluent monolayers of BHK cells as previously described (31), and the monolayers were incubated at 37°C for 40 to 48 h. Infectious centers were visualized as plaques by staining with methylene blue and 4% formaldehyde in PBS (pH 7.5). When antiintegrin antibodies were used to block infection, these reagents were added to the cells for 30 min at room temperature prior to infection.

Concanamycin A experiments. (i) Pretreatment of cells.

Confluent monolayers of SW480 cells expressing wild-type αvβ6 in 35-mm-diameter dishes were treated with concanamycin A or DMSO (mock treatment) in DMEM with 5% FCS for 30 min at 37°C. The drug was removed, and the cells were infected with SAT-3 (MOI = 2 PFU/cell) for 1 h at 37°C in the presence of fresh drug. Virus that remained outside the cells was acid inactivated as described above. Cell monolayers were washed with PBS (pH 7.5) and incubated in DMEM with 5% FCS at 37°C. At 12 h postinfection, the titer of infectious virus in the cell supernatant was determined by plaque assay on BHK cells as previously described (31).

(ii) Treatment with concanamycin A postinfection.

To confirm that concanamycin A was not acting on a postentry step of virus replication, cell monolayers were treated with the drug after infection. Cell monolayers were infected, and virus that remained outside the cells was acid inactivated as described above. At 1 h postinfection, the culture medium was replaced by fresh medium containing either concanamycin A or DMSO, and incubation at 37°C continued for 1.5 h. The cell monolayers were then washed and incubated in fresh cell culture media at 37°C. At 12 h postinfection, the virus titer in the cell supernatant was determined by plaque assay as described above.

Flow cytometry analysis. (i) Integrin expression.

Cells were harvested using EDTA as described above, washed, and resuspended at ∼107 cells per ml in buffer A (cold PBS [pH 7.5], 2 mM CaCl2, 1 mM MgCl2, 1% goat serum, 3% bovine serum albumin, 0.1% sodium azide). All subsequent steps were performed on ice. Cells (30 μl) were incubated with primary antibodies (10 μg/ml) for 30 min. The cells were washed and incubated with a goat anti-mouse immunoglobulin G IgG-biotin conjugate for 30 min. Following another washing step, the cells were incubated with a streptavadin–R-phycoerythrin conjugate (Southern Biotechnology Associates). The cells were then washed twice and resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde in PBS. Fluorescence staining was analyzed by flow cytometry using a FACSCalibur (Becton Dickinson) counting 10,000 cells per sample. Background fluorescence was determined by omitting the primary antibody from the assay.

(ii) Virus binding assay.

Cells were prepared in buffer A as described above and incubated with O1Kcad2 (10 μg/ml) for 30 min on ice. The cells were washed twice and incubated sequentially with the anti-FMDV MAb D9 (10 μg/ml), followed by a goat anti-mouse IgG2a-specific R-phycoerythrin conjugate. Background fluorescence was determined by omitting either FMDV or MAb D9 from the assay. Both control conditions gave near-identical results.

(iii) Competition experiments.

The anti-αvβ6 MAb 10D5 (IgG2a) or peptides were added to the cells for 30 min before the addition of virus for a further 30 min. The cells were then washed, and cell-bound virus was detected using an anti-FMDV MAb, B2 (IgG1), followed by a goat anti-mouse IgG1-specific R-phycoerythrin conjugate.

RESULTS

The β6 cytoplasmic domain is not required for FMDV binding.

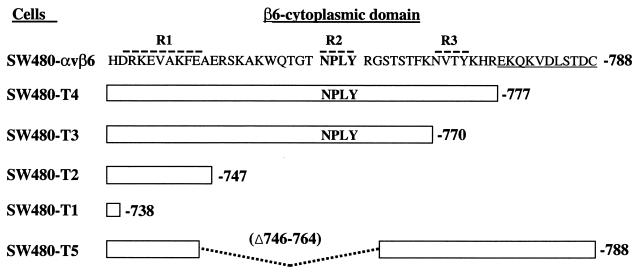

Previously, we showed that the RGD-dependent integrin αvβ6 functions as a receptor for FMDV when expressed on transfected SW480 cells (SW480-αvβ6) (31). To determine whether the cytoplasmic domain of the β6 subunit is required for FMDV infection, we used a series of stably transfected cell lines expressing five different deletion mutations in the cytoplasmic domain of the β6 subunit (SW480-T1 to SW480-T5 [Fig. 1]). These cells have been reported to show similar αvβ6 expression at the cell surface (13). Initially, we confirmed this observation by flow cytometry using a MAb specific for the extracellular domain of αvβ6. We found that on transfectants SW480-T2 and SW480-T3, αvβ6 expression was virtually identical to that of the wild-type integrin expressed on SW480-αvβ6, whereas integrin expression on transfectants SW480-T1, SW480-T4, and SW480-T5 was slightly reduced (see Fig. 4).

FIG. 1.

Schematic diagram showing the amino acid sequences of the different β6 cytoplasmic domains analyzed in these studies. The sequence of the wild-type β6 cytoplasmic domain is shown using the single-letter amino acid code. The broken lines above the sequence indicate the regions important for αvβ6 localization to focal adhesions (13). The conserved NPXY (NPLY) motif is shown in bold type. The underlined sequence is unique to the integrin β6 subunit. SW480-αvβ6 expresses wild-type αvβ6 as a functional heterodimer. SW480-T1 to SW480-T5 are transfectants expressing αvβ6 with deletions in the β6 cytoplasmic domain. The white boxes represent the sequence retained in the β6 subunits. In SW480-T5, the broken line represents an internal deletion.

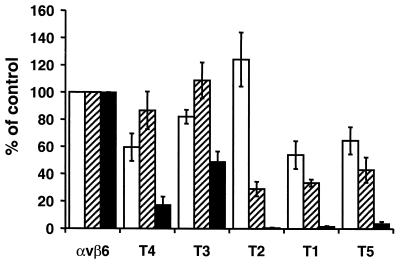

FIG. 4.

The β6 cytoplasmic domain is not required for FMDV binding but is essential for αvβ6-dependent infection. Expression of αvβ6 (white bars), FMDV binding (hatched bars), and the production of infectious centers generated with O1Kcad2 (black bars) in SW480 cells expressing either wild-type αvβ6 (αvβ6) or integrins with deletions in the β6 cytoplasmic domain (SW480-T1 to SW480-T5 [Fig. 1]). The data are expressed as percentages of the value for the control (SW480-αvβ6). Integrin expression was determined by flow cytometry using MAb E7P6, and the means ± standard errors of the mean (SEM) of four independent experiments are shown. Virus binding was determined as described in the legend to Fig. 2, and the means ± SEM of five independent experiments are shown. The infectious center assay was performed as described in Materials and Methods, and the means ± SEM of three independent experiments are shown.

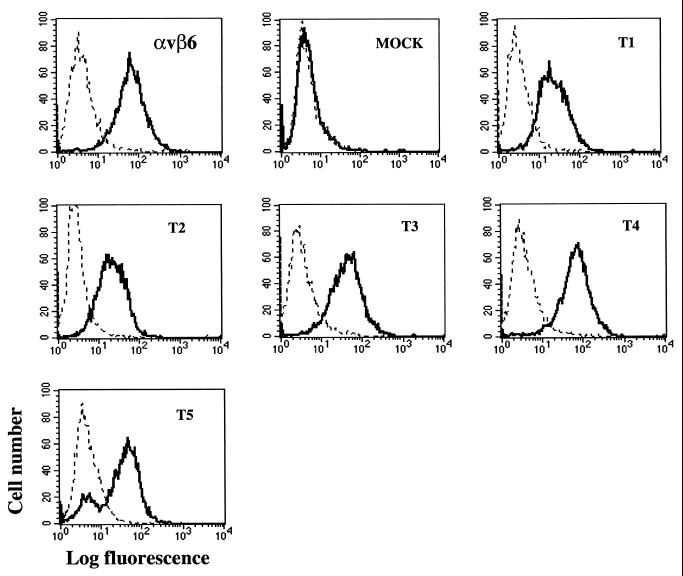

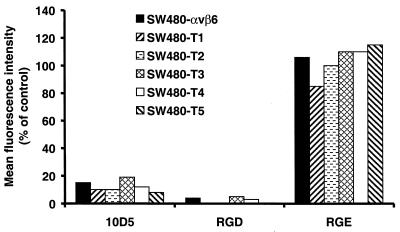

We next assessed whether the mutated integrins support FMDV binding. Figure 2 shows that FMDV binds to cells expressing wild-type αvβ6 (SW480-αvβ6) but not to the mock-transfected cells, thus confirming our previous observation (31). In addition, Fig. 2 shows that cells expressing the mutant integrin also bind FMDV. However, a small proportion of the cells in the SW480-T5 clone did not appear to bind virus. From the experiments shown below (see Fig. 4), we estimate the proportion of nonbinding cells to be 10 to 15%. To verify that virus binding to the cells was mediated by an authentic RGD-dependent interaction with αvβ6, we performed competition experiments using the anti-αvβ6 MAb 10D5 and an RGD-containing peptide. Previously we have shown that these reagents inhibit FMDV binding to αvβ6, whereas a functional blocking antibody to αvβ5 or the RGE version of the peptide have no effect on virus binding (31). Pretreatment of cells with MAb 10D5 or the RGD peptide inhibited virus binding, confirming that as for cells expressing wild-type integrin, αvβ6 serves as the major receptor for FMDV attachment on the cells expressing mutated integrins (Fig. 3). Furthermore, these results show that the β6 cytoplasmic domain is not required for FMDV binding to αvβ6.

FIG. 2.

Flow cytometric analysis of FMDV (O1Kcad2) binding to SW480 cells expressing wild-type or mutated integrin. Control cell samples were processed in the absence of virus (broken line). Virus binding (continuous line) was detected on all cells expressing αvβ6 (SW480-αvβ6 [αvβ6] and SW480-T1 to SW480-T5 [T1 to T5, respectively]). Virus binding was not detected with the mock-transfected cells.

FIG. 3.

FMDV binds to mutated αvβ6 through an RGD-dependent interaction. Cells were pretreated with the anti-αvβ6 MAb 10D5 (100 μg/ml) or peptides (1 mM) for 30 min prior to the addition of virus (O1Kcad2) (10 μg/ml). Cell-bound virus was detected by flow cytometery as described in Materials and Methods. Binding (mean fluorescence intensity) is expressed as a percentage of virus bound to cells pretreated with assay buffer alone (control).

In general, a good correlation between virus binding and αvβ6 expression was observed with the transfected cells with the exception of SW480-T2, as these cells supported less virus binding relative to the level of integrin expression (Fig. 4). αvβ6 receptors expressed on SW480-T2 have been shown to be deficient in binding to latency-associated protein of TGFβ1, the natural ligand for αvβ6 (38). Taken together, these data indicate that the majority of the αvβ6 on SW480-T2 is expressed in a conformation that is unable to bind RGD ligands.

The β6 cytoplasmic domain is essential for αvβ6-mediated infection by FMDV.

The above data show that the cytoplasmic domain of the β6-subunit is not required for FMDV binding. We next sought to determine whether this domain is required for αvβ6-mediated infection. Truncations in the cytoplasmic domain of the β6 subunit have been shown to change the surface distribution of αvβ6 from sites of tight contact with the underlying substratum (focal contacts) and that free in the plasma membrane (13). Since the amount of αvβ6 localized to focal contacts could potentially influence the number of integrin receptors available for virus binding and therefore infection, we performed infectivity studies using an infectious center assay with dispersed cells in suspension, thereby permitting a direct comparison to be made between virus binding and infection.

Virus binding to transfectants SW480-T3 and SW480-T4 generated a significant number of infectious centers (Table 1 and Fig. 4) indicating that the deleted regions of the β6 cytoplasmic domain are not essential for infection. Consistent with the observation that virus binding to SW480-T3 and SW480-T4 is inhibited by MAb 10D5, we found that infection of these cells was also inhibited (>98%) by pretreatment of cells with this antibody (100 μg/ml), whereas the anti-αvβ5 MAb P1F6 had no effect on infection (data not shown). By contrast, virus binding to SW480-T1, SW480-T2, and SW480-T5 resulted in little or no infection (Table 1 and Fig. 4). The small number of infectious centers generated with SW480-T5 was also completely inhibited by MAb 10D5 (data not shown). Taken together, the results of these experiments show that although the cytoplasmic domain of β6 subunit is not required for FMDV binding, this domain has a critical role in regulating postattachment steps in αvβ6-dependent infection.

TABLE 1.

FMDV infection of cells expressing αvβ6 with deletions in the β6 cytoplasmic domain

| Virus and cellsa | No. of infectious centersb | % of controlc |

|---|---|---|

| O1Kcad2 | ||

| SW480-αvβ6 | 14,430 ± 458 | 100 |

| SW480-T1 | 87 ± 7.9 | 0.6 |

| SW480-T2 | 55 ± 21.3 | 0.4 |

| SW480-T3 | 9,300 ± 1,081 | 65 |

| SW480-T4 | 4,700 ± 1,135 | 33 |

| SW480-T5 | 510 ± 156 | 3.5 |

| Mock | 28 ± 9.1 | 0.19 |

| SAT-3 | ||

| SW480-αvβ6 | 23,000 ± 4,582 | 100 |

| SW480-T1 | 330 ± 30 | 1.5 |

| SW480-T2 | 80 ± 34.6 | 0.5 |

| SW480-T3 | 13,000 ± 1,732 | 56 |

| SW480-T4 | 6,700 ± 4,592 | 29 |

| SW480-T5 | 490 ± 96 | 2.0 |

| Mock | 14 ± 6.2 | 0.10 |

Cells (106), either mock-transfected cells (mock) or cells expressing wild-type αvβ6 (SW480-αvβ6) or αvβ6 with deletions in the β6 cytoplasmic domain (SW480-T1 to -T5 [Fig. 1]), were infected with FMDV O1Kcad2 or SAT-3 at MOIs of ∼0.5 and 1 PFU/ml, respectively, as described in Materials and Methods.

Mean number of infectious centers ± standard deviation for one experiment carried out in triplicate.

Mean number of infectious centers expressed as a percentage of the control (SW480-αvβ6) value.

Infection of αvβ6-expressing cells requires active endosomal acidification.

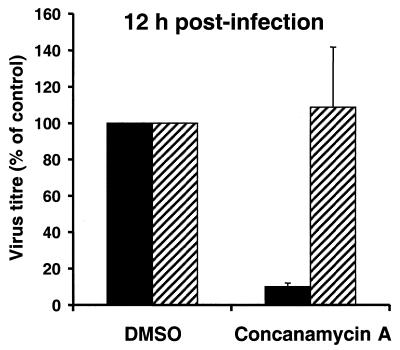

Previous studies have demonstrated that infection of BHK cells by FMDV is inhibited by treatment of the cells with the ionophore monensin, one effect of which is to raise the pH within endosomes, implying that infection proceeds through this compartment (4). To determine whether it is also true of αvβ6-mediated infection, we investigated the effect on infection of concanamycin A, a specific inhibitor of the vacuolar proton-ATPase (19). Preliminary studies, using one-step growth curve analysis, showed that pretreatment of cells with concanamycin A reduced the virus titer in cell supernatants compared to that of mock-treated controls over time in a concentration-dependent manner (data not shown). Figure 5 shows that treatment of cells with concanamycin A (10 μM) prior to infection reduced the virus titer in the cell supernatant compared to that of mock-treated controls. Treatment of cells with concanamycin A at 1 h after infection had a minimal effect on the virus titer (Fig. 5) showing that the drug was not inhibiting a postentry step necessary for virus replication. These data show that active endosomal acidification is required for an early event in αvβ6-mediated infection and imply that infection proceeds through endosomes.

FIG. 5.

αvβ6-dependent infection by FMDV requires active endosomal acidification. Cells were treated with either concanamycin A (10 μM) or DMSO before (black bars) or after (hatched bars) infection by SAT-3 as described in Materials and Methods. At 12 h postinfection, the virus titer in cell culture media was determined by plaque assay on BHK cells. The virus titer (mean ± SEM of three independent experiments) is expressed as a percentage of cells treated with DMSO. The virus titer at time 0 h postinfection was less than 30 PFU/ml.

The concentration of concanamycin A used in the experiment shown in Fig. 5 is greater (1,000 times) than that required to inhibit infection by some other viruses, such as influenza virus where infection is known to be dependent on the acidic pH within endosomes (23). An important difference between these viruses is that the conformational change required for influenza virus internalization is triggered at a pH much lower (pH 5.0 to 6.0) than is uncoating of FMDV (9, 14). Therefore, the comparative difficulty in inhibiting FMDV infection with concanamycin A may reflect the extreme acid sensitivity of the FMDV capsid, as the endosomal pH would necessarily have to be raised to ∼7 to achieve complete inhibition of capsid disassembly and infection.

DISCUSSION

Entry of picornavirus into host cells is a complex process initiated by virus binding to a specific cell surface receptor. Although receptors for FMDV have been identified, there is little information on the precise mechanisms by which these receptors promote entry. Recently, we showed that the RGD-dependent integrin αvβ6 serves as a receptor for FMDV attachment and that virus binding to the integrin results in an increased rate of cell entry (31). In the present study, we have focused on the role of the β6 cytoplasmic domain in FMDV infection. Our results show that complete truncation of the β6 cytoplasmic domain resulted in receptors that although expressed on the cell surface and able to bind FMDV, were defective in mediating infection.

The obvious question that arises from these observations is what is the role of the β6 cytoplasmic domain in infection. The need for β6 cytoplasmic domains implies that αvβ6 does not merely serve to pass virus onto a second receptor for internalization but plays an active role in events subsequent to attachment. The sensitivity of infection to concanamycin A confirms that αvβ6-mediated infection involves an acidification step and is consistent with virus entry proceeding through endosomes. This observation suggests that the regions deleted from the αvβ6 expressed on SW480-T1, SW480-T2, and SW480-T5 may contain important signals for virus localization to endosomes. Interestingly, all of these receptors lack the β6 cytoplasmic domain NPXY motif (Fig. 1). This motif is known to function as a signal that directs various membrane proteins into clathrin-coated vesicles (12). However, the role of the β-subunit NPXY sequence in integrin endocytosis is not well defined (50, 51, 55), and further experimentation will be necessary to more precisely define the role of this motif in FMDV infection.

While infection by FMDV depended completely on the presence of the β6 cytoplasmic domain, smaller inhibitory effects were also seen with β6 chains C terminally truncated in such a way as to leave the NPXY motif intact. Loss of the C-terminal 11 residues, for example, caused approximately 80% reduction in infection (Fig. 4, mutant T4). Interestingly, a similar observation was reported for the T4 cell line by Agrez et al. (2) when studying infection by another picornavirus, coxsackievirus B1. The reason for this impairment is unclear, however, as we found that deleting a further 7 residues (T3) partially restored receptor function to αvβ6.

The β6 cytoplasmic domain could also be needed to complete the final uncoating step in which the viral genome is translocated into the cytosol. Such a requirement has recently been demonstrated for αvβ5-mediated infection by adenovirus (52), but it seems less likely in the FMDV system, given that FMDV has been shown to infect cells through at least three integrin-independent mechanisms (29, 35, 45), thereby implying that the function of membrane permeabilization is an inherent property of the virus and not the receptor.

Many of the intracellular signaling pathways activated by integrins are dependent on the β-subunit cytoplasmic domain, which points to a further possible function of the β6 cytoplasmic domain in facilitating virus entry. For example, signal transduction through αvβ6 could be required to activate a coreceptor necessary for virus internalization. Signal transduction through integrins is known to regulate the ligand-binding affinity of other integrin species expressed on the same cell by a mechanism termed integrin cross-talk (7). SW480 cells normally express two RGD-dependent integrins, αvβ5 and α5β1, and either of these integrins could conceivably be activated following virus binding to αvβ6. However, as we showed previously that neither of these integrins appear to be involved in infection of SW480 cells expressing wild-type αvβ6, this mechanism may be discounted (31). Although we consider it unlikely, we cannot rule out the possibility that signaling through the β6 cytoplasmic domain is necessary for activation of a nonintegrin coreceptor. Alternatively, virus binding to αvβ6 could initiate intracellular signaling pathways that are advantageous for a postentry step in virus replication and/or assembly. However, since mock-transfected SW480 cells in the absence of αvβ6 are permissive for a heparin-binding strain of FMDV (31), such a role for αvβ6 in infection would similarly appear unlikely. However, on the basis of our data, we cannot rule out the possibility that signaling through αvβ6 may be required to promote infection by FMDV by stimulating endocytosis of αvβ6 itself. For example, endosomal uptake of the integrin αvβ5 has been shown to be stimulated by ligand binding (37), and more recently, αvβ5-mediated endocytosis of adenovirus has been shown to require activation of phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase (PI3K), an event dependent on the β5 cytoplasmic domain (33). Using one-step growth curve analysis, we have observed that treatment of cells expressing wild-type αvβ6 with wortmannin (50 to 200 nM), a specific inhibitor of PI3K, did not affect virus replication, suggesting that PI3K activity is not required for αvβ6-dependent infection by FMDV (data not shown).

Our findings contrast with those obtained with some other picornaviruses, namely, poliovirus, coxsackievirus B3, and human rhinovirus type 14 (HRV-14), which show that the single cytoplasmic domain of their receptors are not needed for infection (32, 49, 53). Since such modifications might be expected to prevent receptor uptake into endosomes, these differences tend to support the view that for these latter viruses infection is not dependent on classical receptor-mediated endocytosis or at least not totally dependent on that route. For poliovirus, this view is supported by the observation that infection is not dependent on dynamic-mediated endocytic pathways (17). However, it should be noted that the same study (17) concluded the opposite for HRV-14, i.e., infection requires dynamin-mediated endocytosis to be functional. An additional difference between these viruses and FMDV is that unlike FMDV, they form A-particles on receptor binding and for poliovirus and HRV-14, conversion to A-particles has been shown to occur on binding soluble receptors which lack cytoplasmic domains (32, 49).

While this study was in progress, Neff and Baxt (39) reported findings with αvβ3-expressing cells which would also lead to the opposite conclusion, namely, that infection of COS cells by FMDV does not require the cytoplasmic domain of either the α- or β-subunit. However, the role played by αvβ3 in this system remains unclear, since although this integrin was shown to be required for infection, studies with αvβ3-expressing cells have never clearly established that FMDV binds to this integrin (5, 39).

While the precise mechanisms involved in αvβ6-mediated infection require further investigation, the finding reported herein helps in the understanding of postattachment events in FMDV infection.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Peptides were synthesized at the peptide synthesis facility at the Oxford Centre for Molecular Science, New Chemistry Laboratory, Oxford.

L.C.M. was a recipient of an IAH Ph.D. studentship. This work was supported in part by MAFF.

REFERENCES

- 1.Agrez M, Chen A, Cone R I, Pytela R, Sheppard D. The αvβ6 integrin promotes proliferation of colon carcinoma cells through a unique region of the β6 cytoplasmic domain. J Cell Biol. 1994;127:545–556. doi: 10.1083/jcb.127.2.547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Agrez M, Shafren D R, Gu X, Cox K, Sheppard D, Barry R D. Integrin αvβ6 enhances coxsackievirus B1 lytic infection of human colon carcinoma cells. Virology. 1997;239:71–77. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arita M, Koike S, Aoki J, Horie H, Nomoto A. Interactions of poliovirus with its purified receptor and conformational alterations in the virion. J Virol. 1998;72:3578–3586. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3578-3586.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baxt B. Effect of lysosomotropic compounds on early events in foot-and-mouth disease virus replication. Virus Res. 1987;7:257–271. doi: 10.1016/0168-1702(87)90032-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Berinstein A, Roivainen M, Hovi T, Mason P W, Baxt B. Antibodies to the vitronectin receptor (integrin αvβ3) inhibit binding and infection of foot-and-mouth disease virus to cultured cells. J Virol. 1995;69:2664–2666. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2664-2666.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bianchi E, Denti S, Granata A, Bossi G, Geginat J, Villa A, Rogge L, Pardi R. Integrin LFA-1 interacts with the transcriptional co-activator JAB1 to modulate AP-1 activity. Nature. 2000;404:617–621. doi: 10.1038/35007098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Blystone S D, Slater S E, Williams M P, Crow M T, Brown E. A molecular mechanism of integrin crosstalk: αvβ3 suppression of calcium/calmodulin-dependent protein kinase II regulates α5β1 function. J Cell Biol. 1999;145:889–897. doi: 10.1083/jcb.145.4.889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Blystone S D, Williams M P, Slater S E, Brown E J. Requirement of integrin β3 tyrosine 747 for β3 tyrosine phosphorylation and regulation of αvβ3 avidity. J Biol Chem. 1997;272:28757–28761. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.45.28757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bullough P A, Hughson F M, Skehel J J, Wiley D. Structure of influenza haemagglutinin at the pH of membrane fusion. Nature. 1994;371:37–43. doi: 10.1038/371037a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burroughs J N, Rowlands D J, Sanger D V, Talbot P, Brown F. Further evidence for multiple proteins in the foot-and-mouth disease virus particle. J Gen Virol. 1971;13:73–84. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-13-1-73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Casasnovas J M, Springer T A. Pathways of rhinovirus disruption by soluble intercellular adhesion molecule 1 (ICAM-1): an intermediate in which ICAM-1 is bound and RNA is released. J Virol. 1994;68:5882–5889. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.9.5882-5889.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen W J, Goldstein J L, Brown M S. NPXY, a sequence often found in cytoplasmic tails, is required for coated pit-mediated internalization of the low density lipoprotein receptor. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:3116–3123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cone R I, Weinacker A, Chen A, Sheppard D. Effects of β subunit cytoplasmic domain deletions on the recruitment of the integrin αvβ6 to focal contacts. Cell Adhes Commun. 1994;2:101–113. doi: 10.3109/15419069409004430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curry S, Abrams C C, Fry E, Crowther J C, Belsham G J, Stuart D I, King A M. Viral RNA modulates the acid sensitivity of foot-and-mouth disease virus capsids. J Virol. 1995;69:430–438. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.430-438.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Curry S, Fry E, Blakemore W E, Abu-Ghazaleh R, Jackson T, King A, Lea S, Newman J, Rowlands D, Stuart D. Perturbations in the surface structure of A22 Iraq foot-and-mouth disease virus accompanying coupled changes in host cell specificity and antigenicity. Structure. 1996;4:135–145. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(96)00017-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dedhar S, Hannigan G E. Integrin cytoplasmic interactions and bidirectional transmembrane signalling. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1996;8:657–669. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(96)80107-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.DeTulleo L, Kirchhausen T. The clathrin endocytic pathway in viral infection. EMBO J. 1998;17:4585–4593. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.16.4585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dove A W, Racaniello V R. Cold-adapted poliovirus mutants bypass a postentry replication block. J Virol. 1997;71:4728–4735. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4728-4735.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Drose S, Bindseil K U, Bowman E J, Siebers A, Zeeck A, Altendorf K. Inhibitory effect of modified bafilomycins and concanamycins on P- and V-type adenosine triphosphatases. Biochemistry. 1993;32:3902–3906. doi: 10.1021/bi00066a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ellard F M, Drew J, Blakemore W E, Stuart D I, King A M Q. Evidence for the role of His-142 of protein 1C in the acid-induced disassembly of foot-and-mouth disease virus capsids. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:1911–1918. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-8-1911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Fricks C E, Hogle J M. Cell-induced conformational changes in poliovirus: externalization of the amino terminus of VP1 is responsible for liposome binding. J Virol. 1990;64:1934–1945. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.5.1934-1945.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fry E, Lea S M, Jackson T, Newman J W I, Ellard F M, Blakemore W E, Abu-Ghazaleh R, Samuel A, King A M Q, Stuart D I. The structure and function of a foot-and-mouth disease virus-oligosaccharide receptor complex. EMBO J. 1999;18:543–554. doi: 10.1093/emboj/18.3.543. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guinea R, Carrasco L. Requirement for vacuolar proton- ATPase activity during entry of influenza virus into cells. J Virol. 1995;69:2306–2312. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.4.2306-2312.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Howe A, Aplin A E, Alahari S K, Juliano R. Integrin signalling and cell growth control. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1998;10:220–231. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(98)80144-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Huang X, Wu J F, Spong S, Sheppard D. The integrin αvβ6 is critical for keratinocyte migration on both its known ligand, fibronectin, and on vitronectin. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:2189–2195. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.15.2189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Huang Y, Hogle J, Chow M. Is the 135S poliovirus particle an intermediate during cell entry? J Virol. 2000;74:8757–8761. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.18.8757-8761.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hynes R O. Integrins: versatility, modulation, and signalling in cell adhesion. Cell. 1992;69:11–25. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90115-s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jackson T, Sharma A, Abu-Ghazaleh R, Blakemore W E, Ellard F M, Simmons D L, Newman J W I, Stuart D I, King A M Q. Arginine-glycine-aspartic acid-specific binding by foot-and-mouth disease virus to the purified integrin αvβ3 in vitro. J Virol. 1997;71:8357–8361. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.11.8357-8361.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jackson T, Ellard F M, Abu-Ghazaleh R, Brookes S M, Blakemore W E, Corteyn A H, Stuart D I, Newman J W I, King A M Q. Efficient infection of cells in culture by type O foot-and-mouth disease virus requires binding to cell surface heparan sulfate. J Virol. 1996;70:5282–5287. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5282-5287.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jackson T, Blakemore W E, Newman J W I, Knowles N J, Mould A P, Humphries M J, King A M Q. Foot-and-mouth disease virus is a ligand for the high-affinity binding conformation of integrin α5β1: influence of the leucine residue within the RGDL motif on selectivity of integrin binding. J Gen Virol. 2000;81:51383–51391. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-5-1383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jackson T, Sheppard D, Denyer M, Blakemore W E, King A M Q. The epithelial integrin αvβ6 is a receptor for foot-and-mouth disease. J Virol. 2000;74:4949–4956. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.11.4949-4956.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koike S, Ise I, Nomoto A. Functional domains of the poliovirus receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1991;88:4104–4108. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.10.4104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Li E, Stupack D, Klemke R, Cheresh D A, Nemerow G R. Adenovirus endocytosis via αv integrins requires phosphoinositide-3-OH kinase. J Virol. 1998;72:2055–2061. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.3.2055-2061.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Logan D, Abu-Ghazaleh R, Blakemore W E, Curry S, Jackson T, King A, Lea S, Lewis R, Newman J W I, Parry N, Rowlands D, Stuart D, Fry E. Structure of a major immunogenic site on foot-and-mouth disease virus. Nature. 1993;362:566–568. doi: 10.1038/362566a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mason P W, Reider E, Baxt B. RGD sequence of foot-and-mouth disease virus is essential for infecting cells via the natural receptor but can be bypassed by an antibody-dependent enhancement pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:1932–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.5.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.McCahon D, Crowther J R, Belsham G J, Kitson J D A, Duchesne M, Have P, Meloen R H, Morga D O, de Simone F. Evidence for at least 4 antigenic sites on type foot-and-mouth disease virus involved in neutralization: identification by single and multiple monoclonal antibody-resistant mutants. J Gen Virol. 1989;70:639–645. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-70-3-639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Memmo L M, McKeown-Longo P. The αvβ5 integrin functions as an endocytic receptor for vitronectin. J Cell Sci. 1998;111:425–433. doi: 10.1242/jcs.111.4.425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Munger J S, Huang X, Kawakatsu H, Griffiths M D J, Dalton S L, Wu J, Pittet J F, Kaminski N, Garat C, Matthay M A, Rifkin D B, Sheppard D. The integrin αvβ6 binds and activates latent TGFβ1: a mechanism for regulating pulmonary inflammation and fibrosis. Cell. 1999;96:319–328. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80545-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Neff S, Baxt B. The ability of integrin αvβ3 to function as a receptor for foot-and-mouth disease virus is not dependent on the presence of complete subunit cytoplasmic domains. J Virol. 2001;75:527–532. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.1.527-532.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Neff S, Sa-Carvalho D, Rieder E, Mason P W, Blystone S D, Brown E J, Baxt B. Foot-and-mouth disease virus virulent for cattle utilizes the integrin αvβ3 as its receptor. J Virol. 1998;72:3587–3594. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3587-3594.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.O'Toole T E, Ylanne J, Culley B M. Regulation of integrin affinity states through an NPXY motif in the b subunit cytoplasmic domain. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:8553–8558. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.15.8553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pasch A, Kupper J, Wolde A, Kandolf R, Selinka H. Comparative analysis of virus-host cell interactions of haemagglutinating and non-haemagglutinating strains of coxsackievirus B3. J Gen Virol. 1999;80:53153–53158. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-80-12-3153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Powell R M, Ward T, Evans D J, Almond J W. Interaction between echovirus 7 and its receptor, decay-accelerating factor (CD55): evidence for a secondary cellular factor in A-particle formation. J Virol. 1997;71:9306–9312. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.12.9306-9312.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Prchla E, Kuechler E, Blass D, Fuchs R. Uncoating of human rhinovirus serotype 2 from late endosomes. J Virol. 1994;68:3713–3723. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.6.3713-3723.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reider E, Berinstein A, Baxt B, Kang A, Mason P W. Propagation of an attenuated virus by design: engineering a novel receptor for noninfectious foot-and-mouth disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:10428–10433. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.19.10428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sa-Carvalho D, Rieder E, Baxt B, Rodarte R, Tanuri A, Mason P W. Tissue culture adaptation of foot-and-mouth disease virus selects viruses that bind to heparin and are attenuated in cattle. J Virol. 1997;71:5115–5123. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.7.5115-5123.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Salt J S. Persistent infection with foot-and-mouth disease virus. Top Trop Virol. 1998;1:77–129. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shafren D R, Dorahy D J, Ingham R A, Burns G F, Barry R. Coxsackievirus A21 binds to decay-accelerating factor but requires intercellular adhesion molecule 1 for cell entry. J Virol. 1997;71:4736–4743. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4736-4743.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Staunton D E, Gaur A, Chan P, Springer T. Internalization of a major group human rhinovirus does not require cytoplasmic or transmembrane domains of ICAM-1. J Immunol. 1992;148:3271–3274. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Van Nhieu G T, Krukonis E S, Reszka A A, Horwitz A F, Isberg R R. Mutations in the cytoplasmic domain of the integrin β1 chain indicate a role for endocytosis factors in bacterial internalisation. J Biol Chem. 1996;271:7665–7672. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.13.7665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Vignould L, Usson Y, Balzac F, Tarone G, Block M R. Internalization of the α5β1 integrin does not depend on “NPXY” signals. 1994. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1994;2:603–611. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1994.1271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wang K, Guan T, Cheresh D A, Nemerow G R. Regulation of adenovirus membrane penetration by the cytoplasmic tail of integrin β5. J Virol. 2000;74:2731–2739. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.6.2731-2739.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang X, Bergelson J M. Coxsackievirus and adenovirus receptor cytoplasmic and transmembrane domains are not essential for coxsackievirus and adenovirus infection. J Virol. 1999;73:2559–2562. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.3.2559-2562.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Weinacker A, Chen A, Agrez M, Cone R I, Nishimura S, Wayner E, Pytela R, Sheppard D. Role of the integrin αvβ6 in cell attachment to fibronectin. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:6940–6948. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Ylänne J, Huuskonen J, O'Toole T E, Ginsberg M H, Virtanen I, Gahmberg C G. Mutation of the cytoplasmic domain of the integrin β3 subunit. Differential effects on cell spreading, recruitment to adhesion plaques, endocytosis and phagocytosis. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:9550–9557. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.16.9550. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]