Abstract

The simian-human immunodeficiency virus SHIV-HXBc2 contains the envelope glycoproteins of a laboratory-adapted, neutralization-sensitive human immunodeficiency virus type 1 variant, HXBc2. Serial in vivo passage of the nonpathogenic SHIV-HXBc2 generated SHIV KU-1, which causes rapid CD4+ T-cell depletion and an AIDS-like illness in monkeys. A molecularly cloned pathogenic SHIV, SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2, was derived from the SHIV KU-1 isolate and differs from the parental SHIV-HXBc2 by only 12 envelope glycoprotein amino acid residues. Relative to SHIV-HXBc2, SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 was resistant to neutralization by all of the antibodies tested with the exception of the 2G12 antibody. The sequence changes responsible for neutralization resistance were located in variable regions of the gp120 exterior envelope glycoprotein and in the gp41 transmembrane envelope glycoprotein. The 2G12 antibody, which neutralized SHIV-HXBc2 and SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 equally, bound the HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins on the cell surface comparably. The ability of the other tested antibodies to achieve saturation was less for the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins than for the HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins, even though the affinity of the antibodies for the two envelope glycoproteins was similar. Thus, a highly neutralization-sensitive SHIV, by modifying both gp120 and gp41 glycoproteins, apparently achieves a neutralization-resistant state by decreasing the saturability of its envelope glycoproteins by antibodies.

Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HIV-1) and HIV-2 are the etiologic agents of AIDS in humans (2, 9, 20, 24). Simian immunodeficiency viruses are related viruses that can cause AIDS-like disease in Asian macaques (15, 32, 45). The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins, which exist as trimeric complexes on the virion surface, mediate the attachment of the virus to the target cell and the fusion of the viral and cell membranes (1, 6, 65, 75, 84, 88). Within each trimeric complex, three gp120 exterior envelope glycoproteins are noncovalently associated with three gp41 transmembrane envelope glycoproteins. The gp120 glycoprotein binds the CD4 glycoprotein on the cell surface (11, 14, 36, 49), triggering conformational changes in gp120 that create and/or expose the binding site for one of the chemokine receptors, CCR5 or CXCR4 (63, 67, 81, 86). CCR5 is utilized as a receptor by most transmitted, primary HIV-1 isolates (8, 13, 16, 17). Later in the course of HIV infection, virus variants that can also use CXCR4 as a coreceptor often emerge (21). Extensive passage of HIV-1 isolates on immortalized cell lines typically generates T-cell-line-adapted (TCLA) viruses that utilize only CXCR4 as a coreceptor (21). Chemokine receptor binding is believed to induce additional conformational changes in the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins that lead to the fusion of the viral and target cell membranes by the gp41 transmembrane envelope glycoprotein (6, 75, 84, 88).

During natural infection, the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins are the major viral targets for the humoral immune response (87, 88). Many nonneutralizing antibodies are generated, presumably elicited by envelope glycoprotein complexes that have disassociated into gp120 and gp41 subunits (68, 88). The gp120 glycoprotein contains five conserved (C1 to C5) and five variable (V1 to V5) regions (44); the variable regions elicit strain-restricted neutralizing antibodies (87, 88). Neutralizing antibodies directed against the more conserved elements of the envelope glycoproteins tend to be low in titer. Furthermore, primary HIV-1 isolates are generally more resistant to antibody-mediated neutralization than TCLA isolates (4, 30, 74). Neutralizing antibodies bind the monomeric gp120 glycoproteins of primary and TCLA isolates with comparable affinity (23, 52, 68, 74). In contrast, antibody binding to the trimeric envelope glycoproteins of primary HIV-1 isolates is less efficient than to those of TCLA isolates (23, 68, 74). In addition to relative resistance to neutralizing antibodies, many primary HIV-1 isolates exhibit decreased sensitivity to soluble CD4 (sCD4) (10, 12, 22, 51, 70, 80). It is thought that sCD4 resistance arises as a consequence of in vivo selection for envelope glycoprotein conformations resistant to neutralization by antibodies, including those directed against the CD4-binding site of gp120 (59, 64, 77, 79).

Study of the interaction of antibodies and HIV-1 in vivo has been facilitated by the development of animal models involving inoculation with defined viruses. Because HIV-1 does not infect Old World monkeys (27), chimeric simian-human immunodeficiency viruses (SHIVs) that contain HIV-1 tat, rev, vpu, and env genes in the simian immunodeficiency virus provirus have been created (25, 26, 28, 46–48). SHIVs can infect macaques and elicit HIV-1-specific neutralizing antibody responses. Some SHIVs have been derived by passage in vivo in monkeys, leading to the generation of virus variants that cause rapid CD4+ T-lymphocyte depletion and AIDS-like illness in rhesus monkeys (29, 30, 60, 71, 72). One example is SHIV-HXBc2, which was constructed with the env gene from a TCLA HIV-1 isolate, HXBc2 (46). SHIV-HXBc2 replicated efficiently in monkey peripheral blood mononuclear cells in tissue culture but replicated inefficiently and was apathogenic in several macaque species (46, 47). Serial passage of bone marrow from infected monkeys to naive animals generated SHIV KU-1, which caused profound decreases in CD4+ T lymphocytes in infected monkeys within 3 weeks of infection and, eventually, fatal AIDS-like disease (29, 30). Substitution of the env gene from SHIV KU-1 into the SHIV-HXBc2 provirus generated a virus, designated SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2, that exhibited CD4 T-lymphocyte-depleting ability and pathogenicity in rhesus monkeys (5). The sequence of the SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins corresponds to the consensus sequence of the SHIV KU-1 biological isolate (5, 72). SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 differs from the nonpathogenic parent SHIV-HXBc2 by 12 envelope glycoprotein residues (5). SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 exhibited improved replicative ability and greater resistance to sCD4 and to antibodies directed against the CD4-binding site and the V3 loop of gp120, compared with SHIV-HXBc2 (5). Here we examine the ability of SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 to resist a range of HIV-1-neutralizing antibodies and investigate the envelope glycoprotein determinants of this resistance. We also explore possible mechanisms of neutralization resistance at the level of antibody binding to the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein complex.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Plasmids and recombinant viruses.

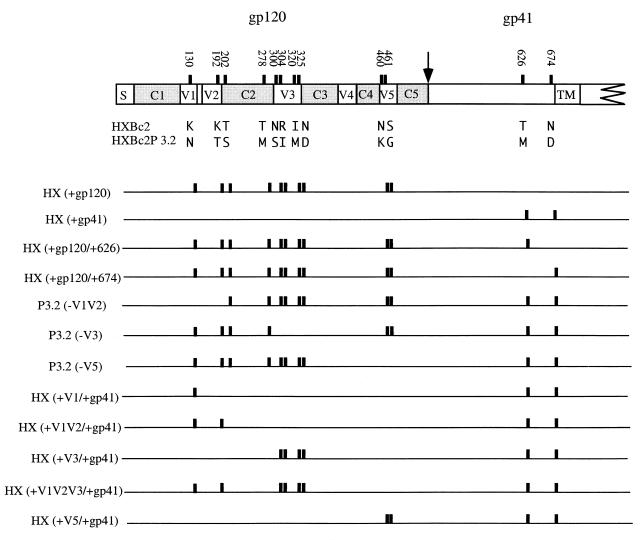

The pSVIIIenvHX and pSVIIIenvHXP3.2 plasmids that express the envelope glycoproteins of SHIV-HXBc2 and SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 have been previously described (5, 89). Plasmids expressing recombinants between SHIV-HXBc2 and SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins (Fig. 1) were created by the exchange of appropriate restriction fragments. The pSVIIIenvHXΔct and pSVIIIenvHXP3.2Δct plasmids, which express the corresponding envelope glycoproteins lacking gp41 cytoplasmic tails, were created by the QuickChange protocol (Stratagene, La Jolla, Calif.) with a sense primer 5′TCTATAGTGAATAGAGTTAGGCAGGTTTAAACACCATTATCGTTT CAGACCCAC3′ and an antisense primer 5′GTGGGTCTGAAACGATAATGGTGTTTAAACCTGCCTAACTCTATTCACTATAGA3′. The envelope glycoproteins that are produced are truncated after amino acid 711 due to the replacement of the codon for tyrosine 712 with a stop codon. (Envelope glycoprotein residue numbering corresponds to that of the prototypic HXBc2 sequence, as per current convention [39].)

FIG. 1.

HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein variants used in this study. (Top) HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins, with the signal peptide (S), gp120-gp41 cleavage site (arrow), and membrane-spanning region (TM) indicated. The conserved (C1 to C5) and variable (V1 to V5) regions of the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins are also indicated. Positions of the amino acid residues that differ between the HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins are indicated as vertical bars. The residue numbers correspond to those of the prototypic HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins, as per current convention (39). The specific HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 amino acid residues at these positions are indicated in single-letter code. (Bottom) Presence of the HXBc2P 3.2 amino acid residue at a particular position in each of the variants shown is indicated by a vertical bar. Where no bar is present, the sequence corresponds to that of the HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins.

Recombinant HIV-1 viruses were generated by transfecting a 100-mm-diameter dish of subconfluent 293T cells with 5 μg of a particular pSVIIIenv plasmid, 5 μg of pCMVΔP1ΔenvpA plasmid, and 15 μg of an HIV-1 vector plasmid expressing firefly luciferase, using the calcium phosphate method (38, 42). Forty-eight hours after transfection, the virus-containing supernatant was harvested and cleared by low-speed centrifugation. Aliquots of 1 ml each were stored at −70°C. The amount of virus in the aliquots was estimated by reverse transcriptase assay.

Antibodies and sCD4.

The IgG1b12 and F105 antibodies, which recognize the CD4-binding site of gp120 (4, 59), were provided by Dennis Burton and Marshall Posner, respectively. The AG1121 antibody directed against the gp120 V3 loop was purchased from ImmunoDiagnostics, Inc. (Woburn, Mass.). The 17b antibody recognizes a CD4-induced gp120 epitope (78) and was provided by James Robinson. The 2G12 antibody, which recognizes a carbohydrate-dependent gp120 epitope (82), and the 2F5 antibody, which recognizes a gp41 epitope (53), were provided by Herman Katinger. The sCD4 was provided by Raymond Sweet (SmithKline Beecham Corp., King of Prussia, Pa.).

Virus neutralization assays.

Approximately 30,000 cpm of reverse transcriptase activity of the recombinant viruses, prepared as described above, was incubated with various concentrations of sCD4 or antibodies in a volume of 500 μl of RPMI 1640 medium at 37°C for 1 h in a 24-well plate. The target CEMx174 cells were propagated at a density of 5 × 105 cells per ml of medium and resuspended in RPMI 1640 medium at a density of 4 × 106 cells per ml of medium. Into each well of virus-antibody mixture, 250 μl (106 cells) of the cell suspension was added. After 16 h at 37°C, 2 ml of fresh RPMI 1640 medium was added, and the 37°C incubation was continued for another 48 h. At that time, the CEMx174 cells were harvested and resuspended in 1 ml of 1× phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and then transferred to 1.5-ml Eppendorf tubes. Pelleted cells were lysed by vortexing in 100 μl of 1× luciferase cell culture lysis reagent (Promega, Madison, Wis.). Cell debris was cleared by high-speed centrifugation, and 40 μl of the supernatant was mixed with 100 μl of luciferase assay reagent (Promega). Luciferase activity was measured using a TD20/20 Luminometer (Promega).

Antibody-binding analysis by flow cytometry.

Measurement of antibody binding to 293T cells that expressed cytoplasmic tail-deleted envelope glycoproteins was carried out by fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS). For FACS analysis, approximately 106 cells were resuspended in 200 μl of FACS buffer (1× PBS, 1% bovine serum albumin, and 0.05% azide) containing different concentrations of a monoclonal antibody or different dilutions of pooled sera from HIV-1-infected individuals. After 60 min of incubation at room temperature, cells were washed twice with 200 μl of FACS buffer and resuspended in 200 μl of the same buffer containing a 1:200 dilution of phycoerythrin-conjugated goat anti-human immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody or goat anti-mouse IgG antibody. The binding reaction mixtures were incubated at room temperature for another 60 min. Cells were then washed and resuspended in 100 μl of FACS buffer and were finally subjected to FACS analysis. Controls included mock-transfected 293T cells stained with primary and secondary antibodies as well as env-transfected 293T cells stained only with secondary antibody.

Syncytium inhibition assays.

The 293T cells were transfected with 10 μg of a plasmid expressing HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins and 1 μg of a Tat-expressing plasmid, using Superfect reagent (Qiagen), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Forty-eight hours after transfection, the cells were detached by EDTA treatment. Approximately 105 cells in 1 ml of complete Dulbecco modified Eagle medium were aliquoted into the wells of a six-well plate in the presence of different concentrations of antibody. Following incubation at 37°C for 1 h, 106 CEMx174 cells in 1 ml of medium were added and mixed gently. The incubation was continued for another 16 h. Syncytia were counted under a microscope.

RESULTS

Relative sensitivity of SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 to neutralization.

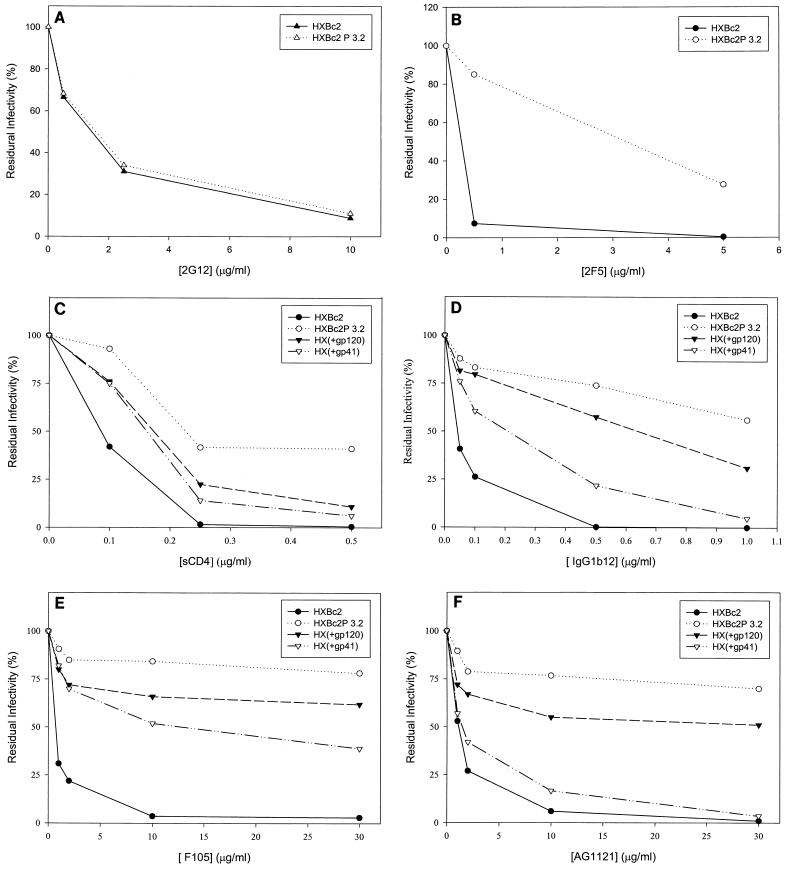

Our previous results (5) demonstrated that recombinant viruses with the SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins were more resistant than viruses with SHIV-HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins to sCD4 and some gp120 antibodies directed against the CD4-binding site and the V3 loop. We examined the relative sensitivity of these recombinant viruses to neutralization by several other well-characterized HIV-1-neutralizing antibodies. These include the 17b antibody directed against a CD4-induced gp120 epitope (78), the 2G12 antibody directed against a carbohydrate-dependent gp120 epitope (82), and the 2F5 antibody directed against a gp41 epitope (53). Recombinant viruses containing the HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins were readily neutralized by all three monoclonal antibodies (Fig. 2A and B and 3E). The sensitivity of viruses with the SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins to neutralization by the 2G12 antibody was indistinguishable from that of viruses with the HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins (Fig. 2A). In contrast, viruses with the SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins were more resistant to neutralization by the 17b and 2F5 antibodies than were viruses with the HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins (Fig. 2B; also data not shown). We also confirmed that, compared with viruses with the HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins, viruses with the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins were resistant to neutralization by sCD4, CD4-binding site antibodies (IgG1b12 and F105), and a V3 loop antibody (AG1121) (Fig. 2C through F). Thus, the envelope glycoproteins of the passage-derived SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 confer a relative degree of resistance to most but not all HIV-1-neutralizing antibodies.

FIG. 2.

Sensitivity of recombinant viruses to neutralization by sCD4 and antibodies. Recombinant viruses containing the envelope glycoproteins indicated in the panel insets were incubated with sCD4 or antibodies prior to infection of CEMx174 cells. The activity of the luciferase protein expressed by the recombinant viruses was measured in the infected cells. The luciferase activity for each recombinant virus in the absence of added ligand was assigned a value of 100%. The ligands incubated with the recombinant viruses were 2G12 (A), 2F5 (B), sCD4 (C), IgG1b12 (D), F105 (E), and AG1121 (F). The results shown are representative of two independent experiments.

Contributions of changes in gp120 and gp41 to neutralization resistance of SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2.

To examine whether the passage-associated changes in the SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 gp120 or gp41 glycoproteins were important for the relative resistance to neutralization, recombinant viruses with chimeric envelope glycoproteins were constructed and tested. The chimeric envelope glycoproteins, HX(+gp120) and HX(+gp41), contain the HXBc2P 3.2 gp120 and gp41 glycoproteins, respectively, with the remainder of the envelope glycoproteins derived from SHIV-HXBc2 (Fig. 1). Recombinant viruses containing the HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins were included as controls. The susceptibility of these recombinant viruses to neutralization by sCD4 or antibodies was tested. The relative resistance of glycoproteins to neutralization by sCD4, IgG1b12, F105, AG1121, 17b, and 2F5 exhibited the pattern HXBc2 < HX(+gp41) < HX(+gp120) < HXBc2P 3.2 (Fig. 2B through F; also see below). Thus, the passage-associated changes in both envelope glycoprotein subunits contribute to the relative neutralization resistance of SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2.

Envelope glycoprotein determinants of neutralization resistance of SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2.

To assess the contribution of each gp120 region and each gp41 amino acid change to the resistance of SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 to neutralization, a panel of additional chimeric envelope glycoproteins was created (Fig. 1). These envelope glycoproteins are named according to the gp120 region or gp41 residue that differs from those of the designated parental envelope glycoprotein. For example, HX(+n) refers to an envelope glycoprotein that is identical to the HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins except for the n region or residue, which is identical to that of the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins. Likewise, P3.2(− n) refers to an envelope glycoprotein that is identical to the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins except for the n region or residue, which is identical to that of the HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins. The envelope glycoproteins produced by these constructs after transfection of 293T cells were examined by precipitation using a mixture of sera from HIV-1-infected individuals. All of the envelope glycoproteins were expressed and proteolytically processed at comparable levels (data not shown).

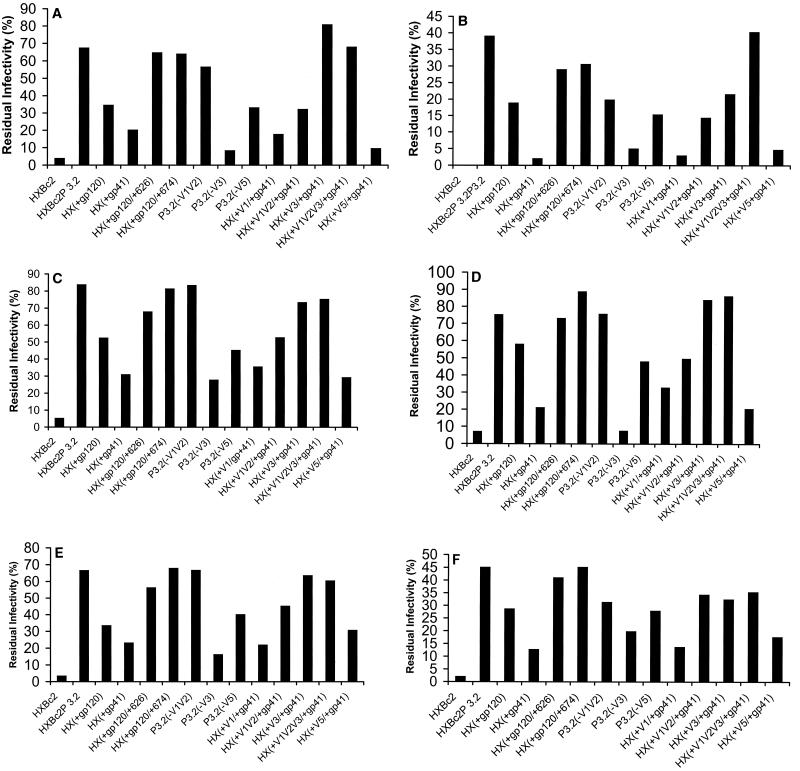

Recombinant viruses with the chimeric envelope glycoproteins were tested for sensitivity to neutralization by sCD4 and antibodies. Based on the dose-inhibition curves in Fig. 2, a single concentration of each ligand was chosen to allow the detection of significant differences between the neutralization sensitivities of viruses with the HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins. Although some differences in the sensitivity of viruses with chimeric envelope glycoproteins to neutralization by different ligands were observed, the overall patterns of sensitivity were remarkably similar (Fig. 3). As has been seen in many previous studies (18, 19, 73, 74, 76, 78, 79), the sensitivity of the viruses to neutralization was not related to the efficiency of virus infection in the absence of added ligand (data not shown). For all of the ligands tested, addition of either of the passage-associated changes in the gp41 glycoprotein to the gp120 changes resulted in a virus that was almost as resistant to neutralization as the virus with the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins [see HX(+120/+626) and HX(+120/+674)]. The V5 changes modestly contributed to the degree of neutralization resistance of viruses with the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins [see P3.2(−V5)] but were insufficient in the absence of other gp120 changes for neutralization resistance [see HX(+V5/+41)]. Changes in the gp120 V3 loop contributed significantly to the resistance to both sCD4 and neutralizing antibodies [see P3.2(−V3)]. For sCD4 and some of the neutralizing antibodies (F105, 17b, and 2F5), the V3 loop and gp41 changes were sufficient to account for most of the neutralization resistance of viruses with the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins [see HX(+V3/+gp41)]. Note that the V3 loop changes largely accounted for the resistance of SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 to the AG1121 antibody. The passage-associated changes in the gp120 V1 and V2 variable regions modulated the neutralization resistance phenotypes in a manner that was highly dependent on the particular ligand. These changes exerted minimal effects on the resistance of the virus to sCD4, for example, but contributed to the resistance of the virus to the IgG1b12 and AG1121 antibodies [compare HX(+gp41) and HX(+V1V2/+gp41), and HX(+V3/+gp41) and HX(+V1V2V3/+gp41)]. Comparison of the phenotypes of viruses with the HX(+gp41) and HX(+V1V2/+gp41) envelope glycoproteins revealed positive contributions of the V1 and V2 loop changes to resistance to the F105, 17b, and 2F5 antibodies. Thus, the broad resistance of SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 to several neutralizing ligands is determined by a combination of passage-associated changes involving the gp120 V1 and V2, V3, and V5 variable regions as well as two changes in the gp41 ectodomain.

FIG. 3.

Determinants of resistance to neutralization by sCD4 and antibodies. Recombinant viruses containing the indicated envelope glycoproteins were incubated with 0.25 μg of sCD4 per ml (A), 1 μg of IgG1b12 per ml (B), 10 μg of F105 per ml (C), 10 μg of AG1121 per ml (D), 30 μg of 17b per ml (E), or 1 μg of 2F5 per ml (F). The ligand concentrations were chosen to allow differences in the neutralization sensitivity of viruses with the HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins to be detected. The luciferase activity in cells exposed to recombinant viruses preincubated with the ligand was divided by the luciferase activity in cells exposed to the same virus preincubated in medium only. The results shown are representative of two independent experiments.

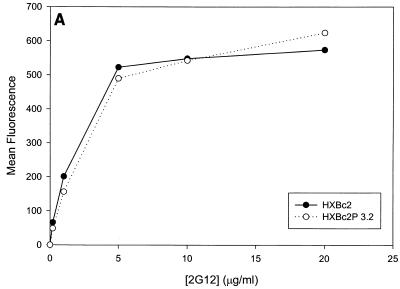

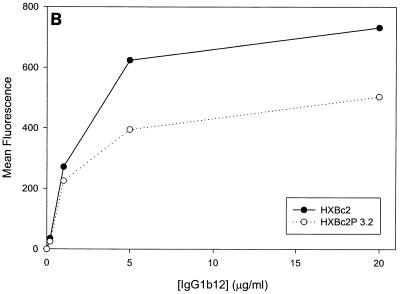

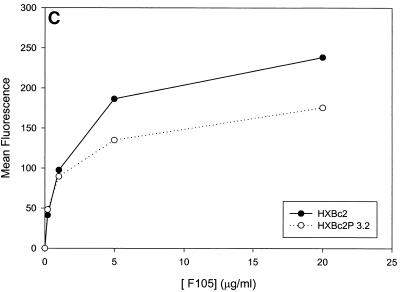

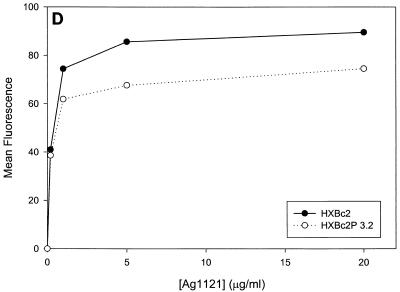

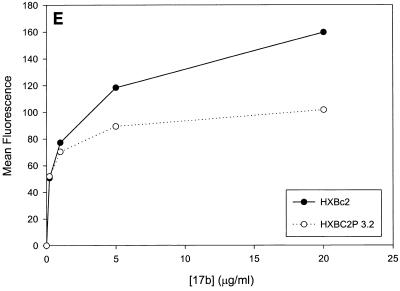

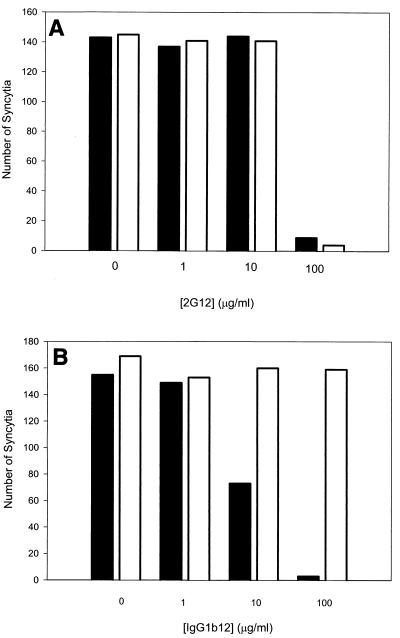

Binding of monoclonal antibodies to cell surface envelope glycoproteins.

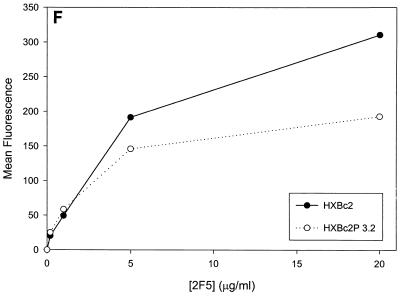

Previous studies (5, 89) indicated that the binding of all the anti-gp120 ligands used in this study to monomeric HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 gp120 was equivalent. To investigate whether differences in antibody binding to the oligomeric HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins might exist, we examined the binding of several antibodies to these envelope glycoproteins expressed on the surface of transfected cells. To increase the expression levels on the cell surface, the gp41 cytoplasmic domain, which contains an endocytosis signal (3, 66, 69), was deleted from the HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins. The 2G12 antibody, which neutralized viruses with HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins equivalently, bound the two envelope glycoproteins on the transfected cell surface indistinguishably (Fig. 4A). The comparable levels of fluorescence observed at saturating concentrations of 2G12 antibody indicated equivalent cell surface expression of the HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins, a conclusion that was independently supported by cell surface biotinylation studies (data not shown). In contrast to the results obtained with the 2G12 antibody, the binding of other antibodies examined revealed less efficient binding to the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins (Fig. 4B through E). Notably, the apparent affinity of the antibodies for the HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins was equivalent, but the amount of antibody bound at saturating or nearly saturating concentrations of antibody was decreased for the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins.

FIG. 4.

Antibody binding to cells expressing the HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins. Transfected 293T cells expressing the HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins were incubated with the indicated concentrations of 2G12 (A), IgG1b12 (B), F105 (C), AG1121 (D), 17b (E) or 2F5 (F) antibodies or with the indicated dilutions of pooled sera from HIV-1-infected individuals (G). The mean fluorescent intensity of the cells after washing is shown. Data shown are representative of two independent experiments.

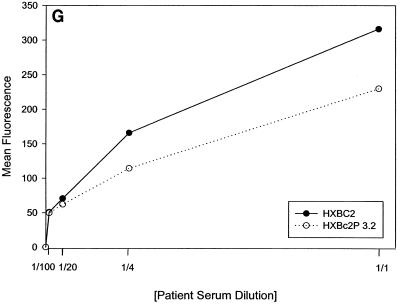

Antibody inhibition of syncytium formation.

To underscore the relevance of the antibody-binding results obtained with cell surface envelope glycoproteins, we compared the ability of selected antibodies to inhibit the formation of syncytia between 293T cells expressing the HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins and target CEMx174 cells. Higher anti-envelope antibody concentrations are required to inhibit syncytium formation than those required to neutralize HIV-1 infection (38). Therefore, we utilized two antibodies, 2G12 and IgG1b12, that exhibit reasonable potency in neutralizing HIV-1 (4, 82). These two antibodies exhibited comparable affinity for the cell surface envelope glycoproteins, although, as noted above, the IgG1b12 antibody did not achieve comparable binding at saturation (Fig. 4A and B). The 2G12 antibody inhibited syncytium formation by the HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins equivalently (Fig. 5A). In contrast, the IgG1b12 antibody inhibited the formation of syncytia by the HXBc2 but not the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins at the antibody concentrations tested (Fig. 5B). Thus, the sensitivity of syncytium formation mediated by the HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins to inhibition by these antibodies parallels that of infection by viruses with these envelope glycoproteins.

FIG. 5.

Sensitivity of syncytium formation to antibody inhibition. The 293T cells transiently expressing the HXBc2 (black bars) and HXBc2P 3.2 (white bars) envelope glycoproteins were cocultivated with CEMx174 cells at 37°C for 16 h in the presence of the indicated concentrations of either 2G12 (A) or IgG1b12 (B) antibodies. The numbers of syncytia were scored. The results shown are representative of two independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In vivo passage of SHIVs in macaques is often associated with an increased resistance to neutralizing antibodies (5, 7, 18, 34). A previous study (5) demonstrated that 12 amino acid changes occurred in the envelope glycoproteins of the nonpathogenic SHIV-HXBc2 during in vivo passage and that these changes were sufficient for the immunopathogenicity and neutralization resistance of the derived virus, SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2. We examined the range of antibodies to which SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 exhibits relative resistance. Compared with viruses containing the HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins, viruses that contain the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins were resistant to neutralization by antibodies directed against the CD4-binding site, CD4-induced epitopes, the V3 loop of gp120, and a moderately conserved gp41 epitope. Viruses with the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins were less sensitive to sCD4 than were viruses with the HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins, although this difference was not as dramatic as that seen for the antibodies listed above. This is consistent with the notion that one major in vivo selective pressure for change in the SHIV-HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins is mediated by antibodies and that the altered ability to bind CD4 is a secondary consequence of adaptation to a milieu in which such antibodies are present. It is noteworthy that SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 remains sensitive to neutralization by the 2G12 antibody, which recognizes the heavily glycosylated, immunologically silent outer domain surface of gp120 (40, 82, 87). Neutralizing antibodies with the epitope specificity of the 2G12 antibody are thought to be elicited only rarely in HIV-1-infected humans due to the resemblance of the highly glycosylated gp120 surface to self glycoproteins (87, 88). Apparently, little selective pressure to alter the sensitivity of SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 to 2G12-like antibodies existed during in vivo passage, suggesting that these antibodies are not abundant in SHIV-infected monkeys. In vivo passage of another SHIV variant, SHIV-89.6, also generated a pathogenic virus that was more resistant to several neutralizing anti-HIV-1 antibodies (18, 33, 34). This pathogenic virus was as sensitive to the 2G12 and 2F5 antibodies as the parental virus (18). This finding supports the idea that 2G12 antibodies are not elicited at significant frequencies or levels in SHIV-infected monkeys. The 2F5 neutralizing anti-gp41 antibody is also thought to be less commonly elicited in HIV-1-infected humans (53). Whether the relative resistance of viruses with the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins to the 2F5 antibody is a specific adaptation to 2F5-like antibodies generated in SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2-infected monkeys or is an indirect consequence of adaptation to the presence of other neutralizing antibodies remains to be determined. In this context, it is noteworthy that SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 is more resistant to sCD4 than to SHIV-HXBc2, whereas passage of SHIV-89.6 did not result in altered sensitivity to sCD4 (34). Resistance to sCD4 is thought to be a secondary consequence of resistance to neutralizing antibodies and involves decreases in the affinity of the oligomeric envelope glycoprotein complexes for CD4, an adaptation not favorable to virus replication (31, 51, 58). It may be that the retained sensitivity of the passage-derived SHIV-89.6 to sCD4 and 2F5, ligands to which the passage-derived SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 is relatively resistant, reflects the better capacity of the 89.6 primary isolate envelope glycoproteins to evolve envelope glycoprotein conformations to meet specific in vivo requirements than the highly laboratory-adapted HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins.

Similarities and differences exist between the envelope glycoprotein determinants that are responsible for the relative neutralization resistance of SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 and those that have been determined to influence the neutralization phenotypes of other SHIVs derived by passage in vivo. Common determinants of neutralization resistance in all of these instances are the gp120 variable loops, with contributions from N-linked sites of glycosylation within these loops (7, 18). This observation is consistent with our studies of the HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 gp120 glycoproteins by competition mapping (89), which indicated that conserved core elements of gp120 were unaltered by the passage-associated changes; rather, the relationships of the V2 and V3 loops to each other and to conserved gp120 epitopes appeared to have been influenced by these changes. X-ray crystal structures of gp120 cores from a laboratory-adapted and a primary HIV-1 isolate (41) confirm the high degree of similarity in the conserved gp120 core elements of HIV-1 isolates that exhibit dramatic differences in sensitivity to antibody or sCD4 neutralization. Genetic studies of primary and TCLA HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins have also pointed to a major role for the gp120 variable loops, particularly the V3 and V2 loops, in determining neutralization resistance (73).

The contribution of changes in the gp41 envelope glycoprotein to the relative neutralization resistance of SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 is unusual in the passage-derived SHIVs that have been analyzed. Both of the passage-associated changes in the HXBc2P 3.2 gp41 ectodomain remove potential sites of N-linked glycosylation. A previous study (43) of HXBc2 envelope glycoproteins indicated that only one of these sites, at asparagine 624, is modified by carbohydrate in COS-1 cells. Based on the migration of the envelope glycoprotein variants on sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gels (data not shown), this appears to be true in 293T cells as well. Carbohydrate addition is commonly thought to contribute to the ability of primate immunodeficiency viruses to evade host immune responses (61), so it is somewhat surprising to observe increased neutralization resistance associated with the removal of carbohydrate. However, it is possible that loss of particular sugars allows packing of the gp120 variable loops in an oligomeric structure that is optimal for attaining an antibody-resistant state. Prior examples exist of gp41 ectodomain changes, not involving glycosylation sites, that affect HIV-1 sensitivity to neutralization by gp120-directed antibodies (35, 54–56, 62, 83, 85). It is noteworthy that one such neutralization-resistant virus was generated by tissue culture passage of a TCLA HIV-1 isolate in the presence of neutralizing serum from an HIV-1-infected individual (62). The unusual involvement of gp41 changes in this example and in the case of SHIV-HXBc2P 3.2 might reflect the existence of common evolutionary pathways to the recovery of a neutralization-resistant state by TCLA viruses.

Our results provide insight into the mechanism whereby the passage-associated changes in the HXBc2P 3.2 gp120 and gp41 glycoproteins collectively contribute to neutralization resistance. Surprisingly, the antibodies that differentially neutralized the function of the HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins exhibited equivalent affinity for these proteins when they were expressed on the cell surface. However, at saturating antibody concentrations, the antibodies that inefficiently neutralized viruses with the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoproteins bound less to the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoprotein complex than to the HXBc2 envelope glycoprotein complex. This was not observed for the 2G12 antibody, which neutralized viruses with the two envelope glycoproteins equivalently. Apparently, at subsaturating antibody concentrations, antibodies can bind epitopes on the HXBc2 and HXBc2P 3.2 trimers equivalently. For antibodies other than 2G12, however, saturating the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoprotein oligomers is extremely inefficient. One explanation is negative cooperativity in the binding of these antibodies to the HXBc2P 3.2 envelope glycoprotein trimer, whereby occupancy of some epitope sites leads to conformational changes that minimize the likelihood of all three sites being occupied. Another model postulates an intrinsic, rather than antibody-induced, heterogeneity in the epitopes on the HXBc2P 3.2 trimer; this model requires asymmetry within the HIV-1 envelope glycoprotein trimers or heterogeneity among trimers. Both models imply that optimal neutralization of HIV-1 requires occupancy of all available binding sites by antibody. This requirement is consistent with data derived from other studies of HIV-1 neutralization (57) and with the observation that subsaturating concentrations of antibody can enhance infection by some primary HIV-1 isolates (73, 74).

The mechanisms underlying the relative resistance of primary HIV-1 isolates to neutralization are of great biological and practical interest. Whether naturally occurring HIV-1 isolates use the strategy of limiting the ability of the viral envelope glycoproteins to be saturated by antibodies will require further investigation. It seems likely that different neutralization-resistant viruses generated under different circumstances will employ unique solutions to the problem of replicating in the face of neutralizing antibodies. Using similar approaches, we and others have observed significant differences in the affinity of neutralizing ligands for the oligomeric envelope glycoproteins of some neutralization-resistant HIV-1 isolates compared with their neutralization-sensitive counterparts (18, 23, 51, 58, 68, 74). In other cases, such as CD4-independent HIV-1 isolates generated by tissue culture adaptation (37), increased neutralization sensitivity is not accompanied by an obvious increase in the affinity of some antibodies for the cell surface oligomers (38). In these cases, there may be differences in the consequences associated with the binding of subsaturating amounts of antibody by the viral envelope glycoproteins. The plasticity of the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins and the variety of options for neutralization escape available to the virus present challenges to the development of effective vaccines and immunotherapeutics.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We acknowledge Raymond Sweet, Dennis Burton, Marshall Posner, and James Robinson for reagents. We thank Sheri Farnum and Yvette McLaughlin for manuscript preparation.

This work was supported by NIH grants AI24755 and AI39420 and by Center for AIDS Research grant AI28691. We also acknowledge the support of the G. Harold and Leila Mathers Foundation, The Ford Foundation, The Friends 10, Douglas and Judith Krupp, and the late William F. McCarty-Cooper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Allan J, Lee T H, McLane M F, Sodroski J, Haseltine W, Essex M. Identification of the major envelope glycoprotein product of HTLV-III. Science. 1983;228:1322–1323. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barre-Sinoussi F, Chermann J C, Rey F, Nugeyre M T, Chamaret S, Gruest J, Dauguet C, Axler-Blin C, Vezinet-Brun F, Rouzioux C, Rozenbaum W, Montagnier L. Isolation of a T-lymphotropic retrovirus from a patient at risk for acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) Science. 1983;220:868–871. doi: 10.1126/science.6189183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berlioz-Torrent C, Shacklett B L, Erdtmann L, Delamarre L, Bouchaert I, Sonigo P, Dokhelar M C, Benarous R. Interactions of the cytoplasmic domains of human and simian retroviral transmembrane proteins with components of the clathrin adaptor complexes modulate intracellular and cell surface expression of envelope glycoproteins. J Virol. 1999;73:1350–1361. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.1350-1361.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burton D R, Pyati J, Koduri R, Sharps S J, Thornton G B, Parren P W, Sawyer L S, Hendry R M, Dunlop N, Nara P L, et al. Efficient neutralization of primary isolates of HIV-1 by a recombinant human monoclonal antibody. Science. 1994;266:1024–1027. doi: 10.1126/science.7973652. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cayabyab M, Karlsson G B, Etemad-Moghadam B A, Hofmann W, Steenbeke T, Halloran M, Fanton J W, Axthelm M K, Letvin N L, Sodroski J G. Changes in human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoproteins responsible for the pathogenicity of a multiply passaged simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV-HXBc2) J Virol. 1999;73:976–984. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.2.976-984.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chan D C, Fass D, Berger J M, Kim P. Core structure of gp41 from HIV envelope glycoprotein. Cell. 1997;73:263–273. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80205-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cheng-Mayer C, Brown A, Harouse J, Luciw P A, Mayer A J. Selection for neutralization resistance of the simian/human immunodeficiency virus SHIVSF33A variant in vivo by virtue of sequence changes in the extracellular envelope glycoprotein that modify N-linked glycosylation. J Virol. 1999;73:5294–5300. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5294-5300.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Choe H, Farzan M, Sun Y, Sullivan N, Rollins B, Ponath P D, Wu L, Mackay C R, LaRosa G, Newman W, Gerard N, Gerard C, Sodroski J. The beta-chemokine receptors CCR3 and CCR5 facilitate infection by primary HIV-1 isolates. Cell. 1996;85:1135–1148. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Clavel F, Guetard D, Brun-Vezinet F, Chamaret S, Rey M A, Santos-Ferreira M O, Laurent A G, Dauguet C, Katlama C, Rouzioux C, et al. Isolation of a new human retrovirus from West African patients with AIDS. Science. 1986;233:343–346. doi: 10.1126/science.2425430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Daar E S, Li X L, Moudgil T, Ho D D. High concentrations of recombinant soluble CD4 are required to neutralize primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1990;87:6574–6578. doi: 10.1073/pnas.87.17.6574. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dalgleish A G, Beverly P C L, Clapham P R, Crawford D H, Greaves M F, Weiss R A. The CD4 (T4) antigen is an essential component of the receptor for the AIDS retrovirus. Nature. 1984;312:763–767. doi: 10.1038/312763a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Deen K, McDougal J S, Inacker R, Folena-Wasserman G, Arthos J, Rosenberg J, Maddon P, Axel R, Sweet R. A soluble form of CD4 (T4) protein inhibits AIDS virus infection. Nature (London) 1988;331:82–84. doi: 10.1038/331082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Deng H, Liu R, Ellmeier W, Choe S, Unutmaz D, Burkhart M, Di Marzio P, Marmon S, Sutton R E, Hill C M, Davis C B, Peiper S C, Schall T J, Littman D R, Landau N R. Identification of a major co-receptor for primary isolates of HIV-1. Nature. 1996;381:661–666. doi: 10.1038/381661a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Denisova G, Raviv D, Mondor I, Sattentau Q J, Gershoni J M. Conformational transitions in CD4 due to complexation with HIV-envelope glycoprotein gp120. J Immunol. 1997;158:1157–1164. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Desrosiers R C. The simian immunodeficiency viruses. Annu Rev Immunol. 1990;8:557–578. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.08.040190.003013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doranz B J, Rucker J, Yi Y, Smyth R J, Samson M, Peiper S C, Parmentier M, Collman R G, Doms R W. A dual-tropic primary HIV-1 isolate that uses fusin and the beta-chemokine receptors CKR-5, CKR-3, and CKR-2b as fusion cofactors. Cell. 1996;85:1149–1158. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81314-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Dragic T, Litwin V, Allaway G P, Martin S R, Huang Y, Nagashima K A, Cayanan C, Maddon P J, Koup R A, Moore J P, Paxton W A. HIV-1 entry into CD4+ cells is mediated by the chemokine receptor CC-CKR-5. Nature. 1996;381:667–673. doi: 10.1038/381667a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Etemad-Moghadam B, Sun Y, Nicholson E K, Karlsson G B, Schenten D, Sodroski J. Determinants of neutralization resistance in the envelope glycoproteins of a simian-human immunodeficiency virus passaged in vivo. J Virol. 1999;73:8873–8879. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8873-8879.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Etemad-Moghadam B, Sun Y, Nicholson E K, Fernandes M, Liou K, Lee J, Sodroski J. Envelope glycoprotein determinants of increased fusogenicity in a pathogenic simian-human immunodeficiency virus (SHIV-KB9) passaged in vivo. J Virol. 2000;74:4433–4440. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4433-4440.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fauci A S, Macher A M, Longo D L, Lane H C, Rook A H, Masur H, Gelmann E P. NIH conference. Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome: epidemiologic, clinical, immunologic, and therapeutic considerations. Ann Intern Med. 1984;100:92–106. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-100-1-92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Feng Y, Broder C C, Kennedy P E, Berger E A. HIV-1 entry cofactor: functional cDNA cloning of a seven-transmembrane, G protein-coupled receptor. Science. 1996;272:872–877. doi: 10.1126/science.272.5263.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fisher R, Bertonis J, Meier W, Johnson V, Costopoulos D, Liu T, Tizard R, Walder B, Hirsch M, Schooley R, Flavell R. HIV infection is blocked in vitro by recombinant soluble CD4. Nature (London) 1988;331:76–78. doi: 10.1038/331076a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fouts T R, Binley J M, Trkola A, Robinson J E, Moore J P. Neutralization of the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 primary isolate JR-FL by human monoclonal antibodies correlates with antibody binding to the oligomeric form of the envelope glycoprotein complex. J Virol. 1997;71:2779–2785. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.4.2779-2785.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gallo R C, Salahuddin S Z, Popovic M, Shearer G M, Kaplan M, Haynes B F, Palker T J, Redfield R, Okeske J, Safai B, White G, Foster P, Markham P D. Frequent detection and isolation of cytopathic retroviruses (HTLV-III) from patients with AIDS and at risk for AIDS. Science. 1984;224:500–503. doi: 10.1126/science.6200936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harouse J M, Gettie A, Tan R C, Blanchard J, Cheng-Mayer C. Distinct pathogenic sequela in rhesus macaques infected with CCR5 or CXCR4 utilizing SHIVs. Science. 1999;284:816–819. doi: 10.1126/science.284.5415.816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hayami M, Igarashi T. SIV/HIV-1 chimeric viruses having HIV-1 env gene: a new animal model and a candidate for attenuated live vaccine. Leukemia. 1997;11(Suppl. 3):95–97. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hofmann W, Schubert D, LaBonte J, Munson L, Gibson S, Scammell J, Ferrigno P, Sodroski J. Species-specific, postentry barriers to primate immunodeficiency virus infection. J Virol. 1999;73:10020–10028. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.12.10020-10028.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Igarashi T, Shibata R, Hasebe F, Ami Y, Shinohara K, Komatsu T, Stahl-Hennig C, Petry H, Hunsmann G, Kuwata T, Jin M, Adachi A, Kurimura T, Okada M, Miura T, Hayami M. Persistent infection with SIVmac chimeric virus having tat, rev, vpu, env and nef of HIV type 1 in macaque monkeys. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1994;10:1021–1029. doi: 10.1089/aid.1994.10.1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Joag S V, Li Z, Foresman L, Stephens E B, Zhao L J, Adany I, Pinson D M, McClure H M, Narayan O. Chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus that causes progressive loss of CD4+ T cells and AIDS in pig-tailed macaques. J Virol. 1996;70:3189–3197. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.5.3189-3197.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joag S V, Li Z, Foresman L, Pinson D M, Raghavan R, Zhuge W, Adany I, Wang C, Jia F, Sheffer D, Ranchalis I, Watson A, Narayan O. Characterization of the pathogenic KU-SHIV model of acquired immunodeficiency syndrome in macaques. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 1997;13:635–645. doi: 10.1089/aid.1997.13.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kabat D, Kozak S L, Wehrly K, Chesebro B. Differences in CD4 dependence for infectivity of laboratory-adapted and primary patient isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1994;68:2570–2577. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.4.2570-2577.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kanki P J, McLane M F, King N W, et al. Serologic identification and characterization of a macaque T-lymphotropic retrovirus closely related to HTLV-III. Science. 1985;228:1199–1201. doi: 10.1126/science.3873705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Karlsson G B, Halloran M, Li J, Park I W, Gomila R, Reimann K A, Axthelm M K, Iliff S A, Letvin N L, Sodroski J. Characterization of molecularly cloned simian-human immunodeficiency viruses causing rapid CD4+ lymphocyte depletion in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1997;71:4218–4225. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.6.4218-4225.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Karlsson G B, Halloran M, Schenten D, Lee J, Racz P, Tenner-Racz K, Manola J, Gelman R, Etemad-Moghadam B, Desjardins E, Wyatt R, Gerard N P, Marcon L, Margolin D, Fanton J, Axthelm M K, Letvin N L, Sodroski J. The envelope glycoprotein ectodomains determine the efficiency of CD4+ T lymphocyte depletion in simian-human immunodeficiency virus-infected macaques. J Exp Med. 1998;188:1159–1171. doi: 10.1084/jem.188.6.1159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klasse P J, McKeating J, Schutten M, Reitzand M, Robert-Guroff M. An immune-selected point mutation in the transmembrane protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 (HXB2-Env:Ala 582-Thr) decreases viral neutralization of monoclonal antibodies to the CD4-binding site. Virology. 1993;196:332–337. doi: 10.1006/viro.1993.1484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Klatzmann D, Champagne E, Charmaret S, Gruest J, Guetard D, Hercend T, Glueckman J-C, Montagnier L. T-lymphocyte T4 molecule behaves as the receptor for human retrovirus LAV. Nature. 1984;312:767–768. doi: 10.1038/312767a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kolchinsky P, Mirzabekov T, Farzan M, Kiprilov E, Cayabyab M, Mooney L J, Choe H, Sodroski J. Adaptation of a CCR5-using, primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate for CD4-independent replication. J Virol. 1999;73:8120–8126. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.10.8120-8126.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Kolchinsky P, Kiprilov E, Sodroski J. Increased neutralization sensitivity of CD4-independent human immunodeficiency virus variants. J Virol. 2001;75:2041–2050. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.5.2041-2050.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Korber B T, Foley B, Kuiken C, Pillai S, Sodroski J G. Human retroviruses and AIDS: a compilation and analysis of nucleic acid and amino acid sequences. Los Alamos, N.Mex: Los Alamos National Laboratories; 1998. Numbering position in HIV relative to HXB2CG, p. III-102–III-103. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kwong P D, Wyatt R, Robinson J, Sweet R, Sodroski J, Hendrickson W. Structure of an HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein in complex with the CD4 receptor and a neutralizing antibody. Nature. 1998;393:648–659. doi: 10.1038/31405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kwong P D, Wyatt R, Majeed S, Robinson J, Sweet R, Sodroski J, Hendrickson W. Structures of HIV-1 gp120 envelope glycoproteins from laboratory-adapted and primary isolates. Structure. 2000;8:1329–1339. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(00)00547-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.LaBonte J, Patel T, Hofmann W, Sodroski J. Importance of membrane fusion mediated by the human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoproteins for lysis of primary CD4-positive T cells. J Virol. 2000;74:10690–10698. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.22.10690-10698.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lee W R, Yu X F, Syu W J, Essex M, Lee T H. Mutational analysis of conserved N-linked glycosylation sites of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41. J Virol. 1992;66:1799–1803. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.3.1799-1803.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Leonard C, Spellman M, Riddle L, Harris R, Thomas J, Gregory T. Assignment of intrachain disulfide bonds and characterization of potential glycosylation sites of the type 1 human immunodeficiency virus envelope glycoprotein (gp120) expressed in Chinese hamster ovary cells. J Biol Chem. 1990;265:10373–10382. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Letvin N L, Daniel M D, Sehgal P K, Desrosiers R C, Hunt R D, Waldron L M, MacKey J J, Schmidt D K, Chalifoux L V, King N W. Induction of AIDS-like disease in macaque monkeys with T-cell tropic retrovirus STLV-III. Science. 1985;230:71–73. doi: 10.1126/science.2412295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li J, Lord C I, Haseltine W, Letvin N L, Sodroski J. Infection of cynomolgus monkeys with a chimeric HIV-1/SIVmac virus that expresses the HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1992;5:639–646. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Li J T, Halloran M, Lord C I, Watson A, Ranchalis J, Fung M, Letvin N L, Sodroski J. Persistent infection of macaques with simian-human immunodeficiency viruses. J Virol. 1995;69:7061–7067. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.11.7061-7067.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Luciw P A, Pratt-Lowe E, Shaw K E, Levy J A, Cheng-Mayer C. Persistent infection of rhesus macaques with T-cell-line-tropic and macrophage-tropic clones of simian/human immunodeficiency viruses (SHIV) Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:7490–7494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.16.7490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Maddon P J, Dalgleish A G, McDougal J S, Clapham P R, Weiss R A, Axel R. The T4 gene encodes the AIDS virus receptor and is expressed in the immune system and the brain. Cell. 1986;47:333–348. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(86)90590-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Mascola J R, Snyder S W, Weislow O S, Belay S M, Belshe R B, Schwartz D H, Clements M L, Dolin R, Graham B S, Gorse G J, Keefer M C, McElrath M J, Walker M C, Wagner K F, McNeil J G, McCutchan F E, Burke D S. Immunization with envelope subunit vaccine products elicits neutralizing antibodies against laboratory-adapted but not primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. The National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases AIDS Vaccine Evaluation Group. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:340–348. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.2.340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Moore J P, McKeating J, Huang Y, Ashkenazi A, Ho D D. Virions of primary human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates resistant to soluble CD4 (sCD4) neutralization differ in sCD4 binding and glycoprotein gp120 retention from sCD4-sensitive ones. J Virol. 1992;66:235–243. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.1.235-243.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Moore J P, Cao Y, Qing L, Sattentau Q J, Pyati J, Koduri R, Robinson J, Barbas III C F, Burton D R, Ho D D. Primary isolates of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 are relatively resistant to neutralization by monoclonal antibodies to gp120, and their neutralization is not predicted by studies with monomeric gp120. J Virol. 1995;69:101–109. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.1.101-109.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Muster T, Steindl F, Purtscher M, Trkola A, Klima A, Himmler G, Ruker F, Katinger H. A conserved neutralizing epitope on gp41 of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1993;67:6642–6647. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.11.6642-6647.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Park E J, Vujcic L K, Anand R, Theodore T S, Quinnan G V., Jr Mutations in both gp120 and gp41 are responsible for the broad neutralization resistance of variant human immunodeficiency virus type 1 MN to antibodies directed at V3 and non-V3 epitopes. J Virol. 1998;72:7099–7107. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.9.7099-7107.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Park E J, Quinnan G V., Jr Both neutralization resistance and high infectivity phenotypes are caused by mutations of interacting residues in the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp41 leucine zipper and the gp120 receptor- and coreceptor-binding domains. J Virol. 1999;73:5707–5713. doi: 10.1128/jvi.73.7.5707-5713.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Park E J, Gorny M K, Zolla-Pazner S, Quinnan G V., Jr A global neutralization resistance phenotype of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 is determined by distinct mechanisms mediating enhanced infectivity and conformational change of the envelope complex. J Virol. 2000;74:4183–4191. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4183-4191.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Parren P W, Mondor L, Naniche D, Ditzel H J, Klasse P J, Burton D R, Sattentau Q J. Neutralization of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 by antibody to gp120 is determined primarily by occupancy of sites on the virion irrespective of epitope specificity. J Virol. 1998;72:3512–3519. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.5.3512-3519.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Platt E J, Kozak S L, Kabat D. Critical role of enhanced CD4 affinity in laboratory adaptation of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. AIDS Res Hum Retrovir. 2000;16:871–882. doi: 10.1089/08892220050042819. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Posner M R, Cavacini L A, Emes C L, Power J, Byrn R. Neutralization of HIV-1 by F105, a human monoclonal antibody to the CD4 binding site of gp120. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 1993;6:7–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Reimann K A, Li J T, Veazey R, Halloran M, Park I- W, Karlsson G B, Sodroski J, Letvin N L. A chimeric simian/human immunodeficiency virus expressing a primary patient human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolate env causes an AIDS-like disease after in vivo passage in rhesus monkeys. J Virol. 1996;70:6922–6928. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.10.6922-6928.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Reitter J N, Means R E, Desrosiers R C. A role for carbohydrates in immune evasion in AIDS. Nat Med. 1998;4:679–684. doi: 10.1038/nm0698-679. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Reitz M S, Jr, Wilson C, Naugle C, Gallo R C, Robert-Guroff M. Generation of a neutralization-resistant variant of HIV-1 is due to selection for a point mutation in the envelope gene. Cell. 1988;54:57–63. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90179-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Rizzuto C, Wyatt R, Hernandez-Ramos N, Sun Y, Kwong P D, Hendrickson W A, Sodroski J. A conserved HIV gp120 glycoprotein structure involved in chemokine receptor binding. Science. 1998;280:1949–1953. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Roben P, Moore J, Thali M, Sodroski J, Barbas C, Burton D. Recognition properties of a panel of human recombinant Fab fragments to the CD4 binding site of gp120 that show differing abilities to neutralize human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1994;68:4821–4828. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.8.4821-4828.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Robey W G, Safai B, Oroszlan S, Arthur L O, Gonda M A, Gallo R C, Fischinger P J. Characterization of envelope and core structural gene products of HTLV-III with sera from AIDS patients. Science. 1985;228:593–595. doi: 10.1126/science.2984774. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Rowell J F, Stanhope P E, Siliciano R F. Endocytosis of endogenously synthesized HIV-1 envelope protein. Mechanism and role in processing for association with class II MHC. J Immunol. 1995;155:473–488. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Sattentau Q J, Moore J P, Vignaux F, Traincard F, Poignard P. Conformational changes induced in the envelope glycoproteins of the human and simian immunodeficiency viruses by soluble receptor binding. J Virol. 1993;67:7383–7393. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.12.7383-7393.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Sattentau Q J, Moore J P. Human immunodeficiency virus type 1 neutralization is determined by epitope exposure on the gp120 oligomer. J Exp Med. 1995;182:185–196. doi: 10.1084/jem.182.1.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Sauter M M, Pelchen-Matthews A, Bron R, Marsh M, LaBranche C C, Vance P J, Romano J, Haggarty B S, Hart T K, Lee W M, Hoxie J A. An internalization signal in the simian immunodeficiency virus transmembrane protein cytoplasmic domain modulates expression of envelope glycoproteins on the cell surface. J Cell Biol. 1996;132:795–811. doi: 10.1083/jcb.132.5.795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Smith D, Byrn R, Marsters S, Gregory T, Groopman J, Capon D. Blocking of HIV-1 infectivity by a soluble secreted form of the CD4 antigen. Science. 1987;238:1704–1707. doi: 10.1126/science.3500514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Stephens E B, Joag S V, Sheffer D, Liu Z Q, Zhao L, Mukherjee S, Foresman L, Adany I, Li Z, Pinson D, Narayan O. Initial characterization of viral sequences from a SHIV-inoculated pig-tailed macaque that developed AIDS. J Med Primatol. 1996;25:175–185. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0684.1996.tb00014.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Stephens E B, Mukherjee S, Sahni M, Zhuge W, Raghavan R, Singh D K, Leung K, Atkinson B, Li Z, Joag S V, Liu Z Q, Narayan O. A cell-free stock of simian-human immunodeficiency virus that causes AIDS in pig-tailed macaques has a limited number of amino acid substitutions in both SIVmac and HIV-1 regions of the genome and has altered cytotropism. Virology. 1997;231:313–321. doi: 10.1006/viro.1997.8534. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Sullivan N, Sun Y, Binley J, Lee J, Barbas III C F, Parren P W H I, Burton D R, Sodroski J. Determinants of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 envelope glycoprotein activation by soluble CD4 and monoclonal antibodies. J Virol. 1998;72:6332–6338. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.8.6332-6338.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Sullivan N, Sun Y, Li J, Hofmann W, Sodroski J. Replicative function and neutralization sensitivity of envelope glycoproteins from primary and T-cell line-passaged human immunodeficiency virus type 1 isolates. J Virol. 1995;69:4413–4422. doi: 10.1128/jvi.69.7.4413-4422.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tan K, Liu J, Wang J, Shen S, Lu M. Atomic structure of a thermostable subdomain of HIV-1 gp41. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1997;94:12303–12308. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.23.12303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Thali M, Charles M, Furman C, Cavacini L, Posner M, Robinson J, Sodroski J. Resistance to neutralization by broadly reactive antibodies to the human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 glycoproteins conferred by a gp41 amino acid change. J Virol. 1994;68:674–680. doi: 10.1128/jvi.68.2.674-680.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Thali M, Charles M, Furman C, Cavacini L, Posner M, Robinson J, Sodroski J. Discontinuous, conserved neutralization epitopes overlapping the CD4-binding region of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 envelope glycoprotein. J Virol. 1992;66:5635–5641. doi: 10.1128/jvi.66.9.5635-5641.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Thali M, Moore J P, Furman C, Charles M, Ho D D, Robinson J, Sodroski J. Characterization of conserved human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 neutralization epitopes exposed upon gp120-CD4 binding. J Virol. 1993;67:3978–3988. doi: 10.1128/jvi.67.7.3978-3988.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Thali M, Olshevsky U, Furman C, Gabuzda D, Posner M, Sodroski J. Characterization of a discontinuous human immunodeficiency virus type 1 gp120 epitope recognized by a broadly reactive neutralizing human monoclonal antibody. J Virol. 1991;65:6188–6193. doi: 10.1128/jvi.65.11.6188-6193.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Traunecker A, Luke W, Karjalainen K. Soluble CD4 molecules neutralize human immunodeficiency virus type 1. Nature (London) 1988;331:84–86. doi: 10.1038/331084a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Trkola A, Dragic T, Arthos J, Binley J M, Olson W C, Allaway G P, Cheng-Mayer C, Robinson J, Moore J P. CD4-dependent, antibody-sensitive interactions between HIV-1 and its coreceptor CCR5. Nature. 1996;384:184–186. doi: 10.1038/384184a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Trkola A, Purtscher M, Muster T, Ballaun C, Buchacher A, Sullivan N, Srinivasan K, Sodroski J, Moore J P, Katinger H. Human monoclonal antibody 2G12 defines a distinctive neutralization epitope on the gp120 glycoprotein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1. J Virol. 1996;70:1100–1108. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.2.1100-1108.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Watkins B A, Buge S, Aldrich K, Davis A E, Robinson J, Reitz M S, Jr, Robert-Guroff M. Resistance of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 to neutralization by natural antisera occurs through single amino acid substitutions that cause changes in antibody binding at multiple sites. J Virol. 1996;70:8431–8437. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.12.8431-8437.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Weissenhorn W, Dessen A, Harrison S C, Skehel J J, Wiley D C. Atomic structure of the ectodomain from gp41. Nature. 1997;387:426–430. doi: 10.1038/387426a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Wilson C, Reitz M S, Jr, Aldrich K, Klasse P J, Blomberg J, Gallo R C, Robert-Guroff M. The site of an immune-selected point mutation in the transmembrane protein of human immunodeficiency virus type 1 does not constitute the neutralization epitope. J Virol. 1990;64:3240–3248. doi: 10.1128/jvi.64.7.3240-3248.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Wu L, Gerard N P, Wyatt R, Choe H, Parolin C, Ruffing N, Borsetti A, Cardoso A A, Desjardin E, Newman W, Gerard C, Sodroski J. CD4-induced interaction of primary HIV-1 gp120 glycoproteins with the chemokine receptor CCR-5. Nature. 1996;384:179–183. doi: 10.1038/384179a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Wyatt R, Kwong P D, Desjardins E, Sweet R, Robinson J, Hendrickson W, Sodroski J. The antigenic structure of the human immunodeficiency virus gp120 envelope glycoprotein. Nature. 1998;393:705–711. doi: 10.1038/31514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Wyatt R, Sodroski J. The HIV-1 envelope glycoproteins: fusogens, antigens, and immunogens. Science. 1998;280:1884–1888. doi: 10.1126/science.280.5371.1884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Ye Y, Si Z H, Moore J P, Sodroski J. Association of structural changes in the V2 and V3 loops of the gp120 envelope glycoprotein with acquisition of neutralization resistance in a simian-human immunodeficiency virus passaged in vivo. J Virol. 2000;74:11955–11962. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.24.11955-11962.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]