Summary

Helicobacter-induced gastric cancer progresses very slowly, even in animal models, making it difficult to study. Here, we present a protocol to establish an accelerated murine model for Helicobacter-induced gastric cancer. We describe steps for infecting mice with Helicobacter felis, harvesting gastric tissue, assessing disease severity by histopathologic scoring, and performing gene expression studies with RT-qPCR and RNA sequencing. The accelerated model shows rapid progression of the disease, with gastric precancerous lesions developing within 6 months post-infection with Helicobacter.

For complete details on the use and execution of this protocol, please refer to Bali et al.1

Subject areas: Cancer, Microbiology, Model Organisms, Molecular Biology

Graphical abstract

Highlights

-

•

Protocol for developing an accelerated gastric cancer model

-

•

Steps for performing mouse infections, tissue harvesting, and histology

-

•

Details for performing cDNA synthesis and RT-qPCR

-

•

Instructions for performing RNA sequencing and pathway enrichment

Publisher’s note: Undertaking any experimental protocol requires adherence to local institutional guidelines for laboratory safety and ethics.

Helicobacter-induced gastric cancer progresses very slowly, even in animal models, making it difficult to study. Here, we present a protocol to establish an accelerated murine model for Helicobacter-induced gastric cancer. We describe steps for infecting mice with Helicobacter felis, harvesting gastric tissue, assessing disease severity by histopathologic scoring, and performing gene expression studies with real-time RT-PCR and RNA sequencing. The accelerated model shows rapid progression of the disease, with gastric precancerous lesions developing within 6 months post-infection with Helicobacter.

Before you begin

Institutional permissions

CRITICAL: All animal procedures for this study have been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of California, San Diego (Protocol Number: S02243) and conducted in compliance with federal regulations regarding the care and use of laboratory animals: Public Law 99–158, the Health Research Extension Act, and Public Law 99–198, the Animal Welfare Act which is regulated by USDA, APHIS, CFR, Title 9, parts 1, 2, and 3.

Six- to ten- week-old wild type C57BL/6 (WT) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME). MyD88 deficient (Myd88−/−) were from our breeding colony originally provided by Dr. Akira (Osaka University, Japan) and backcrossed 10 times onto a C57BL/6 background, bred, and maintained at our facility.

Note:Myd88−/− mice are available for purchase from different vendors including The Jackson Laboratory.

Purchase Helicobacter felis, strain CS1 (ATCC 49179) from the American Type Culture collection (Manassas, VA).

Animals

-

1.

All mice should be housed in the same facility throughout the study in a biosafety level II (BSL-2) facility.

-

2.

The mice should be maintained in a room controlled temperature (23 ± 2°C) and relative humidity (45%–60%).

-

3.

All mice should have full access to food and water.

Preparation 1: Growing bacteria to use for infecting mice

Timing: 11 days

-

4.

Streak Helicobacter felis, strain CS1 (ATCC 49179) on solid Columbia agar supplemented with 5% laked blood and 1% amphotericin B and incubate the cultures under microaerophilic conditions (5% O2, 10% CO2, 85% N2) at 37°C for 5 days (Figure 1).

-

5.

Passaged bacterial cultures every 2–3 days by streaking onto fresh solid media.2,3,4,5

-

6.

Two days prior to infecting mice, culture H. felis in 30 mL liquid brain heart infusion (BHI) broth supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum in a T-75 cell culture flask.

-

7.

Maintain the culture for 48 h on an orbital shaker at 50 rpm and incubated at 37°C under microaerophilic conditions (5% O2, 10% CO2, 85% N2) (Methods video S1).

-

8.

Count spiral bacteria using a Petroff-Hausser chamber before infections.

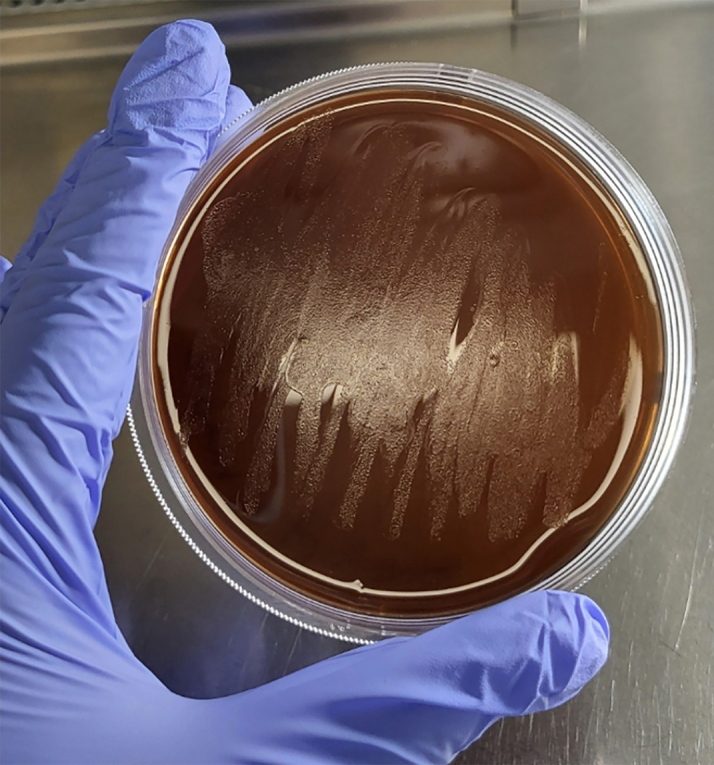

Figure 1.

H. felis on Columbia agar

The image shows H. felis growing as a lawn, not as individual distinct colonies.

Preparation 2: Mouse infections

Timing: 6 months, 1 week

-

9.

Inoculate mice (Myd88−/− and WT) with 109 organisms in 300 μL of BHI by oral gavage using a feeding needle.2,3,4,5

-

10.

Repeat inoculations of mice with H. felis at 1-day intervals for a total of three inoculations.

Note: Successful H. felis infections can be detected by performing PCR using mice fecal pellets using Helicobacter specific primers.6

-

11.

After 3 months post-infection with H. felis euthanize the mice and remove their stomachs.

Note: The level of disease severity is compared with the standard model of gastric cancer, which is WT mice. However, to demonstrate disease progression, we also infect both Myd88−/− and WT mice with H. felis for 1 or 6 months (Figure 1).

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Helicobacter felis, strain CS1 | American Type Culture Collection | ATCC 49179 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Human gastric biopsy tissue samples | Biorepository, University of California, San Diego | N/A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Direct-zol RNA MiniPrep kit | Zymo Research | R2050 |

| High-capacity cDNA reverse transcription kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 4368814 |

| Illumina TruSeq stranded total RNA sample prep kit with Ribo-Zero | Illumina | 20020597 |

| Deposited data | ||

| GEO accession number: GSE250438 | Bali et al., 20241 | GSE250438 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: WT: C57BL/6 | Jackson Laboratory | C57BL/6J |

| Mouse: Myd88 KO: Myd88 deficient | Dr. Akira’s laboratory | N/A |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers for qPCR | see Table S1 | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 8.2.0 | GraphPad Software | https://www.graphpad.com/scientificsoftware/prism/ |

| HOMER’s analyzeRepeats.pl | Dr. Benner’s lab | N/A |

| Other | ||

| NanoDrop 2000 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | ND-2000 |

| Veriti thermal cycler | Applied Biosystems | 4375305 |

| StepOne | Applied Biosystems | 272001471 |

| Illumina/Solexa HiSeq 2500 sequencer | Illumina | SY-401-2501 |

| SURE-TEK biopsy cassette | Fisher Scientific | 22-048-119 |

| 10% formalin | Fisher Scientific | SF98-4 |

| UltraPure DNase/RNase-free distilled water | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 10977015 |

| MicroAmp 96-well reaction plate | Applied Biosystems | 43446906 |

| Biopsy foam pads | Fisher Scientific | 22-038-221 |

| Flex 80 dehydrating reagent | Fisher Scientific | 22-046344 |

| Ethanol | Millipore Sigma | 493511 |

| TRIzol | Invitrogen | 15596026 |

| KIMBLE Dounce tissue grinder set | Millipore Sigma | DWK885300-0001 |

| Microfuge tube 1.5 mL | Genesee Scientific | 24-285 |

| 0.2 mL PCR tubes | Genesee Scientific | 22-154 |

| Microcentrifuge, 5425 | Eppendorf | 5405000719 |

| Agilent 2100 bioanalyzer | Agilent | AG-2100B |

| Rotary microtome RM 2125 RTS | Leica Biosystems | 14045746960 |

| Epredia HistoStar embedding workstation | Fisher Scientific | A81000002 |

| Fisherbrand Isotemp water bath | Fisher Scientific | FSGPD05S24 |

| Axio Imager.A2 microscope | Zeiss | 490022-0002-000 |

| AT2 Aperio digital slide scanner | Leica Biosystems | 23AT2100 |

| TC-treated dishes 100 × 20 mm | Genesee Scientific | 25-202 |

| Fetal calf serum | Thermo Fisher Scientific | 16000044 |

| Columbia agar | Becton Dickinson | 294420 |

| Bacto agar | Becton Dickinson | 214020 |

| Laked Horse blood | Hardy Diagnostic | 10052-812 |

| Amphotericin B | Corning | 30-003-CF-1 |

| Brain heart infusion broth | Becton Dickinson | 237500 |

| Petroff-Hausser counting chamber | Hausser Scientific | 3900 |

| Drummond Pipet-Aid | Fisher Scientific | 13-681-19 |

| Serological pipettes, 50 mL | Genesee Scientific | 12-107 |

| Serological pipettes, 25 mL | Genesee Scientific | 12-106 |

| Serological pipettes, 10 mL | Genesee Scientific | 12-104 |

| Serological pipettes, 5 mL | Genesee Scientific | 12-102 |

| 50 mL conical flask | Genesee Scientific | 28-106 |

| 1,000 μl, barrier tip, racked sterile | Genesee Scientific | 23-430 |

| 200 μL, barrier tip, racked sterile | Genesee Scientific | 23-412 |

| 10 μl, barrier tip, racked sterile | Genesee Scientific | 23-401 |

| Gilson PIPETMAN P100 pipette | Fisher Scientific | F144057MG |

| Gilson PIPETMAN P1000 | Fisher Scientific | F144059MG |

| Gilson PIPETMAN P200 pipette | Fisher Scientific | F144058MG |

| Gilson PIPETMAN P10 pipette | Fisher Scientific | F144055MG |

| Gilson PIPETMAN P2 pipette | Fisher Scientific | F144054MG |

| Corning 1 L Pyrex glass bottle | Millipore Sigma | CLS13951L |

| Corning 500 mL Pyrex glass bottle | Millipore Sigma | CLS1395500 |

| Thermo Scientific orbital shaker | Fisher Scientific | 11-676-233 |

| Thermo Forma CO2 incubator | Thermo Fisher Scientific | TH-3120 |

| Oral gavage feeding needle | Millipore Sigma | CAD7909 |

| TC-treated flasks, 25 mL, vent | Genesee Scientific | 25-207 |

| Thermo Scientific 1300 Series Class II, Type A2 biosafety cabinet | Fisher Scientific | 13-261-304 |

| Xylene histology | Fisher Scientific | 60-047-036 |

| Epredia Clear-Rite 3 | Fisher Scientific | 69-05 |

| Epredia bluing reagent | Fisher Scientific | 6769001 |

| Epredia Clarifier 1 | Fisher Scientific | 22-050-118 |

| Epredia Shandon Eosin-Y stain | Fisher Scientific | 6766007 |

| Epredia Histoplast paraffin | Fisher Scientific | 83-30 |

| Thermo Scientific oven | Fisher Scientific | 11-475-152 |

| Thermo Scientific ultra-low chest freezer | Thermo Fisher Scientific | TDEC39686FA |

Materials and equipment

Preparation of Brain Heart Infusion (BHI) Liquid Broth (1 L)

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| BHI | - | 37 g |

| ddH2O | - | 1000 mL |

| Total | 1000 mL |

Mix thoroughly and warm to completely dissolve. Sterilize by autoclaving. Store at 15°C–25°C for 6 months.

Preparation of Columbia Agar (1 L)

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| Columbia Broth | - | 35 g |

| Bacto Agar | - | 15 g |

| ddH2O | - | 1000 mL |

| Total | 1000 mL |

Mix thoroughly and warm to completely dissolve. Sterilize by autoclaving. Store at 15°C–25°C for 6 months.

Preparation of 70% Alcohol (100 mL)

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| 99% Ethanol | 70 | 70 mL |

| Water | - | 30 mL |

| Total | 100 mL |

Store at 15°C–25°C for a year.

Preparation of 95% Alcohol (100 mL)

| Reagent | Final concentration | Amount |

|---|---|---|

| 99% Ethanol | 95 | 95 mL |

| Water | - | 5 mL |

| Total | 100 mL |

Store at 15°C–25°C for a year.

-

•

Nanodrop 2000 (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Alternatives: Any other spectrophotometer equipped for RNA quantification can be used.

-

•

Veriti Thermal Cycler (Applied Biosystems).

Alternatives: Any other thermal cycler can be used.

-

•

StepOne qPCR(Applied Biosystems).

Alternatives: Any other qPCR machine can be used.

-

•

Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent).

Alternatives: 5300 Fragment Analyzer (Agilent), Experion automated system (Bio-Rad), machine can be used.

-

•

Illumina/Solexa HiSeq 2500 sequencer (Illumina).

Alternatives: Any other high throughput Next-Gen sequencer can be used.

-

•

Rotary microtome RM 2125 RTS (Leica).

Alternatives: Any other microtome can be used.

-

•

Epredia HistoStar Embedding Workstation (Fisher Scientific).

Alternatives: Any other embedding workstation can be used.

-

•

Axio Imager A2 microscope (Zeiss).

Alternatives: Any other upright microscope can be used.

-

•

AT2 Aperio Digital slide scanner (Leica).

Alternatives: Any other digital slide scanner can be used.

-

•

Thermo Forma CO2 Incubator (Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Alternatives: Any other CO2 Incubator can be used.

-

•

Thermo Scientific 1300 Series Class II, Type A2 Biosafety cabinet (Fisher Scientific).

Alternatives: Any other Class II, Type A2 Biosafety cabinet can be used.

-

•

HistoCore Pegasus Automated Tissue Processor (Leica).

Alternatives: Any other Automated Tissue Processor can be used.

-

•

Epredia Gemini Autostainer (Fisher Scientific).

Alternatives: Any other Slide stainer can be used.

-

•

Epredia ClearVue coverslipper (Fisher Scientific).

Alternatives: Any other Coverslipper can be used.

Step-by-step method details

Preparing mouse stomach tissue sections for various analyses

Timing: 6 months

In this section, mice stomachs are harvested at different time points and stomach tissue is sectioned.

-

1.

At indicated time points, post-infection with H. felis (Figure 2), euthanize mice with carbon dioxide followed by cervical dislocation.

-

2.

Remove the stomach from the abdominal cavity and open the stomach by cutting along the greater curvature.

-

3.

Cut the stomach tissue longitudinally into three sections (Figure 3), one section to be processed for histology and two sections snap-frozen separately to use for RNA sequencing and real-time PCR and stored in −80°C deep freezer for later use.

CRITICAL: Immediately freeze the tissue samples to be processed for RNA and store in −80°C deep freezer for later use to maintain integrity of the RNA and for better yield.

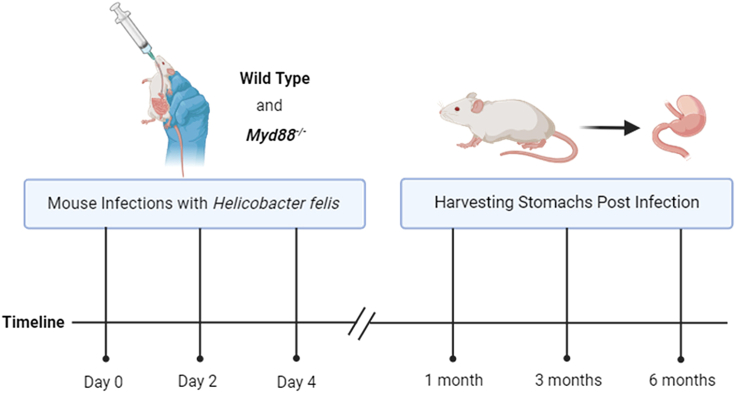

Figure 2.

Mouse infection timeline

This illustration shows the timeline of inoculating WT and Myd88−/− mice with H. felis by oral gavage at an interval of one day for a total of three inoculations. Uninfected mice serve as control for each genetic background. n = 8 mice /group.

Figure 3.

Illustration of mouse stomach sections used for analyses

At indicated time points mice are euthanized and stomachs are removed from the abdominal cavity. Each mouse stomach is opened by cutting along the greater curvature and laid flat on a petri plate. Then it is cut into longitudinal sections and processed for various analyses.

Fixing tissue section before paraffin embedding

Timing: 20 h

In this section, longitudinal stomach tissue sections are fixed.

-

4.

Flatten longitudinal sections of stomach tissue from each mouse by placing each tissue between biopsy foam pads in a biopsy cassette.

-

5.

Fix the tissue sections in neutral buffered 10% formalin.

-

6.

After 18 h of fixation remove the formalin and immerse the cassettes containing tissue section in Flex 80 dehydrating reagent.

Note: In this step you can use 70% ethanol instead of Flex 80.

Preparing gastric tissue sections for paraffin embedding

Timing: 4 h

In this section, stomach tissue sections are paraffin embedded.

-

7.

Take the fixed gastric tissue sections and run them on short cycle on automated tissue processor.

Steps of the short cycle on the automated processor.

Short cycle

| Station | Solution | Time (min) | Temperature °C | Vacuum | Mix speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 70% Alcohol | 15 | Ambient | ON | FAST |

| 2 | 70% Alcohol | 15 | Ambient | ON | FAST |

| 3 | 95% Alcohol | 15 | Ambient | ON | FAST |

| 4 | 100% Alcohol | 15 | Ambient | ON | FAST |

| 5 | 100% Alcohol | 15 | Ambient | ON | FAST |

| 6 | 100% Alcohol | 20 | Ambient | ON | FAST |

| 7 | 100% Alcohol | 20 | Ambient | ON | FAST |

| 8 | Xylene | 15 | Ambient | ON | FAST |

| 9 | Xylene | 20 | Ambient | ON | FAST |

| 10 | Xylene | 20 | Ambient | ON | FAST |

| 11 | Paraffin | 20 | 60 | ON | FAST |

| 12 | Paraffin | 30 | 60 | ON | FAST |

| 13 | Paraffin | 30 | 60 | ON | FAST |

Embed gastric tissue sections

Timing: 1 h

In this section, each stomach tissue section is embedded in a tissue cassette.

-

8.

Transfer the tissue from the automated process to an embedding instrument. Embed the gastric tissue on the edge.

-

9.

Open one tissue cassette at a time to maintain accuracy of each sample and label. Make one paraffin block for each tissue cassette (Figure 4).

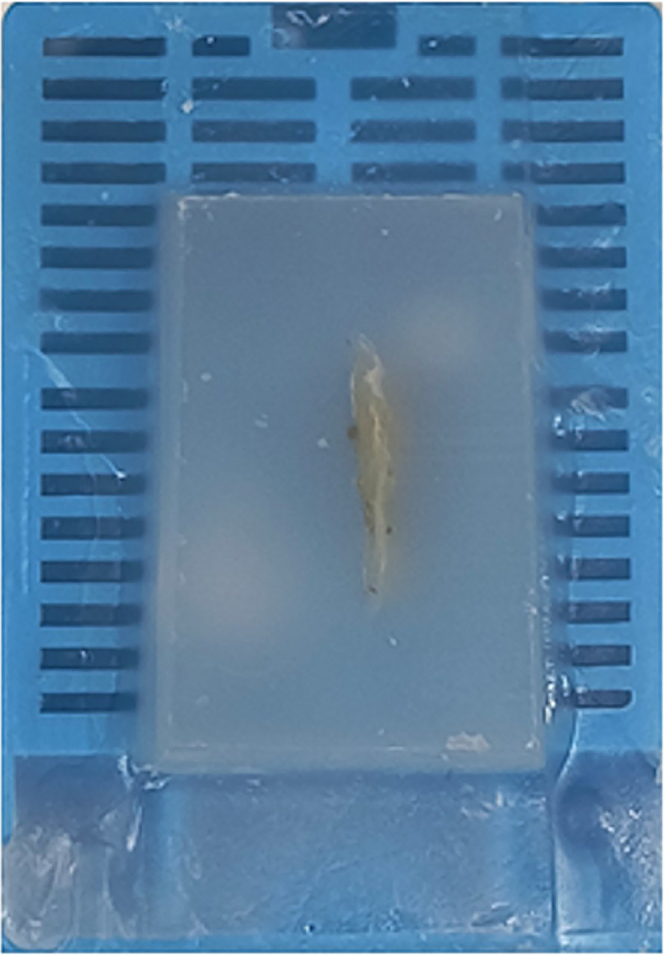

Figure 4.

A paraffin embedded tissue section

A stomach tissue section was paraffin embedded and cut on the edge for histopathology analysis.

Section gastric tissue samples

Timing: 24 h

In this section, paraffin embedded tissues are sectioned, and the flattened tissue sections are placed on slides.

-

10.

Place paraffin embedded tissue block in a rotary microtome blade holder.

-

11.

Adjust thickness to 5 μm.

-

12.

Cut and collect 2 to 6 gastric tissue sections in a ribbon.

-

13.

Place the ribbon of tissue sections in a water bath at 38°C–40°C.

-

14.

Separate the sections using forceps and place on a clear pre-labeled slide.

CRITICAL: Allow the slides with sections to remain in the water bath until they are flattened. Ensure there are no air bubbles trapped under the gastric tissue. Make sure the gastric tissue sections are free of debris and wrinkles.

-

15.

Air-dry the gastric tissue sections for 12 h.

Stain the gastric tissue sections

Timing: 1.5 h

In this section, gastric tissues sections are stained with hematoxylin and eosin.

-

16.

Stain the gastric tissue sections with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) using an automatic staining system.

-

17.

Cover the stained gastric tissue with a coverslip using an automated coverslipper instrument.

-

18.

Image the H&E-stained gastric tissue sections on the slides using an upright microscope to observe the morphological features.

-

19.

Scan the slides at 40X magnification using a digital slide scanner.

-

20.

Send the slides to a blinded pathologist to review and score histopathologic parameters.

Steps of Hematoxylin-Eosin staining protocol

| S. No. | Protocol | Time | Repetition |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Oven | 60 min | One |

| 2 | Clear-Rite 3 | 3 min | Three |

| 3 | 100% Ethanol | 1 min | Two |

| 4 | 95% Ethanol | 1 min | One |

| 5 | Running Water | 1 min | One |

| 6 | Clarifier 1 | 5 s | One |

| 7 | Running Water | 1 min | One |

| 8 | Bluing Reagent | 30 s | One |

| 9 | Running Water | 1 min | One |

| 10 | 70% Ethanol | 30 s | One |

| 11 | Eosin | 3 min | One |

| 12 | 70% Ethanol | 1 min | One |

| 13 | 95% Ethanol | 1 min | One |

| 14 | 100% Ethanol | 1 min | Four |

| 15 | Clear-Rite 3 | 3 min | Three |

| 16 | Move the rack to the coverslipper instrument or mount/coverslip slides manually | ||

Pathology scoring

Timing: 14 days

In this section, the H&E stained gastric tissue sections are scored for disease severity.

-

21.

Score H&E-stained gastric tissue sections for gastric histopathologies, including inflammation, epithelial defects, gland atrophy, hyperplasia, intestinal metaplasia, and dysplasia following the criteria outlined by Rogers et al.7

-

22.

Give a score for histologic disease severity on a scale from 0 (no lesions) to 4 (severe lesions).

Note: Scoring the histological characteristics is performed as follows: inflammation—infiltration of inflammatory cells into the mucosa and submucosa; epithelial defects—thinned epithelial surface, epithelial and mucosal erosion and multifocal collapse; oxyntic gland atrophy—loss of oxyntic glands (which contain parietal cells and chief cells) in the gastric corpus; mucous metaplasia- presence of large foamy mucus secreting cells; intestinal metaplasia—replacement of gastric epithelium by intestinal type gastric epithelium; and dysplasia—abnormal cellular and glandular maturation of the epithelium, with score of 3 indicating carcinoma in situ.

Extract RNA from mouse gastric tissue sections

Timing: 1 day

In this section, RNA is extracted from mouse gastric tissue.

-

23.

Pulverize the frozen gastric tissue and transfer to a microfuge tube containing 1 mL TRIzol reagent.

-

24.

Homogenize the gastric tissue sample using the dounce tissue homogenizer.

-

25.

Centrifuge the gastric homogenates at 4°C at 13226 × g for 30 min.

-

26.

Transfer the supernatant to complete RNA extraction using the Direct-zol RNA mini kit as per the manufacturer’s instructions (Protocol link).

-

27.

Determine the quality of the extracted RNA using a Nanodrop system by measuring absorbance levels at 230, 260, and 280 nm.

CRITICAL: The quality of the RNA is very important. If the 260/230 ratio is less than 1, it indicates the presence of contaminants such as TRIzol. The acceptable value is between 2.0 and 2.2. The 260/280 ratio should be between 1.65 and 2.0 with a ratio of 1.8 considered pure.

-

28.

Use the extracted RNA for quantitative real time PCR and RNA sequencing.

Perform cDNA synthesis and quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Timing: 8 h

In this section, the extracted RNA is subjected to cDNA synthesis followed by real time RT-PCR.

-

29.

Use 2 μg of RNA extracted from each gastric tissue to reverse transcribe RNA into cDNA using the High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription (RT) kit according to manufacturer’s instructions (Protocol link).

-

30.

Details of the reagents prepared are shown below.

RT Master Mix prepared using High Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcriptase Kit

| Component | Volume (μL) |

|---|---|

| 10X RT Buffer | 2.0 |

| 25X dNTP mix | 0.8 |

| 10X RT Random Primers | 2.0 |

| MultiScribe Reverse Transcriptase | 1.0 |

| Nuclease free water | 4.2 |

| Total | 10 |

-

31.

The reverse transcription reaction is prepared by mixing 10 μL of RT Master Mix with 10 μL of RNA (2 μg concentration, diluted with nuclease free water to make the final volume of 10 μL), to make a total reaction volume of 20 μL per individual tube.

-

32.

The tubes are loaded on to the thermal cycler following the amplification conditions shown below.

Note: After the RT-PCR cycle is complete store the cDNA tubes in −20°C till further use or proceed to the next step.

RT Cycle conditions

| Steps | Temperature °C | Time (min) |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 25 | 10 |

| 2 | 37 | 120 |

| 3 | 85 | 5 |

| 4 | 4 | Hold |

-

33.

Use 1 μL of each cDNA sample for real-time PCR per well in a total of 10 μL reaction mix.

-

34.

Details of amplification conditions and reagents are shown below.

q-PCR Master Mix prepared using SYBR Green Mix

| Component | Volume (μL) |

|---|---|

| SYBR Green Mix | 5.0 |

| Forward Primer (10 μM) | 0.5 |

| Reverse Primer (10 μM) | 0.5 |

| Nuclease free water | 3.0 |

| cDNA | 1.0 |

| Total | 10 |

qPCR Cycle conditions

| Steps | Temperature °C | Time | Cycle |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 95 | 5 min | 1 |

| 2 | 95 | 15 s | 40 |

| 3 | 60 | 20 s | |

| 4 | 72 | 40 s | |

| 5 | 4 | Hold | Forever |

-

35.

Primers are listed in supplementary material (Table S1).

Perform RNA sequencing

Timing: 14 days

In this section, the RNA extracted from gastric tissue samples are subjected to RNA Sequencing.

-

36.

Use RNA extracted from mouse gastric tissue sections.

-

37.

Measure RNA concentration and integrity using an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer, which assigns each sample an RNA integrity number (RIN).

CRITICAL: The quality of RNA is very important. A RIN number of 8 or higher is preferred because it indicates that the RNA is of high quality, which also means it is intact. A lower RIN number indicates that the RNA is degraded. A high RIN value is crucial for a proper library construction.

-

38.

Prepare the RNA-seq library for sequencing using the Illumina TruSeq Stranded Total RNA Sample Prep Kit with Ribo-Zero (Human/Mouse/Rat) according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Protocol link), which encompass ribosomal RNA depletion, fragmentation, cDNA synthesis, and cDNA library preparation.

CRITICAL: Avoid the use of sample prep kits that only measure mRNA (they specifically capture polyadenylated RNAs) as these approaches are much more sensitive to changes in RIN integrity and could result in a 3′ capture bias and increased sample variability.

-

39.

Perform RNA-sequencing on an Illumina/Solexa HiSeq 2500 sequencer to generate 75-bp single-end reads for all samples at a depth of approximately 40 million reads per sample.

Perform RNA-seq data analysis

Timing: 2 days

In this section, RNA-seq data analysis is performed.

-

40.

Trim RNA-seq reads to remove non-biological library adapter sequences by applying the fastp8 program to RNA-seq FASTQ files from each experiment.

-

41.

Align the trimmed RNA-seq reads from each experiment to the mouse genome using the program STAR.9

-

42.

Create HOMER-style tag directories for each experiment using HOMER’s makeTagDirectory program.10

-

43.

Determine gene-level read counts for all experiments by counting the number of reads overlapping exons for all genes using HOMER’s analyzeRepeats.pl tool and the transcriptome annotation from GENCODE.10

-

44.

Use DESeq2 to identify genes that are differentially expressed from the unnormalized read counts across all experiments.11

-

45.

Following analysis of RNA-seq data with DESeq2, use the EnhancedVolcano package from R/Bioconductor to construct a volcano plot to visualize the differential expression data.

-

46.

Use the DESeq2’s rlog function to normalize the raw gene counts and use the normalized gene expression values to cluster and generate a heatmap to visualize the RNA-seq data.

-

47.

Use HOMER’s makeUCSCfile tool to generate normalized genome browser read density files (bedGraph), which can then be visualized using the UCSC Genome Browser (http://genome.ucsc.edu/).

Perform pathway and motif enrichment analysis

Timing: 1 day

In this section, the pathway and motif enrichment analysis is performed.

-

48.

Use Metascape,12 a web-based portal that integrates multiple knowledge bases, including the Gene Ontology, to identify overrepresented pathways in sets of regulated genes.

-

49.

Use differentially expressed genes with a fold change of at least 2 and an adjusted p-value of 0.05 as input for Metascape analysis.

CRITICAL: It is important to correct for multiple hypothesis testing for the pathway enrichment data acquired using Metascape.

-

50.

Use HOMER, a software suite for DNA motif and next-generation sequence (NGS) analysis9 to analyze transcription factor motifs in mouse stomach tissue sections (RNA-seq data).

-

51.

Scan known transcription factor motifs from the HOMER database in mouse promoter sequences defined within a range from −300 to +50 bp relative to the GENCODE-defined transcription start site (TSS) locations of differentially regulated genes.

-

52.

Calculate their enrichment relative to non-regulated genes in the mouse genome using HOMER’s findMotifs.pl tool.

CRITICAL: The known motif results from this analysis will report a Benjamini-Hochberg procedure corrected q-value that address concerns arising from multiple hypothesis testing.

Expected outcomes

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) infection is an established cause of many digestive diseases, including gastritis, peptic ulcers, and gastric cancer.12 The development of gastric cancer is a very slow process, which complicates the study of this disease. Consequently, there is an urgent need for a Helicobacter-induced model that allows for more rapid study of disease progression. We compare our accelerated murine model of gastric cancer to the standard murine model of gastric cancer. Both models involve infection of C57BL/6 mice with H. felis, a close relative of the human pathogen, H. pylori,13,14 and have been established as cancer mouse models that closely recapitulate the disease progression observed in humans during H. pylori infection.4,15,16,17,18,19 We show that gastric precancerous lesions develop and progress more rapidly and with greater severity in H. felis-infected Myd88−/− mice (accelerated model) when compared to H. felis-infected WT mice (standard model) (Figures 5 and 6). In addition, the model exhibits activation of common oncogenic pathways and novel pathways/genes. The advantages of using this model include the following; i) it shortens the window for Helicobacter infection disease transformation into premalignant gastric lesions by 6 months, allowing for more rapid study of disease progression, ii) it exhibits activation of common oncogenic pathways and, in addition, the activation of novel pathways/genes, providing valuable insights into gastric cancer development, and iii) importantly, the gastric neoplastic phenotype in this model only manifests following Helicobacter infection,1 making it highly relevant to human gastric cancer development.

Figure 5.

Representative mice stomachs following infection with H. felis for 1, 3, or 6 months

Mice stomachs exhibit thicker mucosa with larger folds that increase in thickness with time in Myd88−/−-infected (accelerated model) compared to WT-infected (standard model) mice. n = 8 mice /group.

Figure 6.

Histopathologic stages in mouse gastric tissue in response to H. felis infection

WT and Myd88−/− mice are infected with H. felis for 1, 3, or 6 months (8 mice /group). Representative mouse stomach tissue sections from WT and Myd88−/− mice are shown (bar scale: 500 μm) (A). Mice stomachs are processed and scored double-blinded for histologic disease severity on an ascending scale from 0 (no lesions) to 4 (severe lesions) as described in our previous studies4,20 using criteria outlined by Rogers et al.7 (B). Histopathologic scores, which are a measure of disease severity4,5,7,21 show significant differences with increased disease in H. felis-infected Myd88−/− mice (accelerated model) compared to H. felis-infected WT mice (standard model). ∗p < .05, ∗∗p < .01, ∗∗∗p < .001.

Limitations

The study used only male mice, which limits generalization of the results. However, this was done to allow for comparison with previous studies that have investigated gastric carcinogenesis using the H. felis infection mouse model that have also used only male mice.15,22,23 This is the limitation of the study. There is immune infiltration in both the accelerated (H. felis-infected Myd88−/−) and standard (H. felis-infected WT) mouse models as indicated by the inflammation score in Figure 6. However, the difference is that the disease progresses faster in the accelerated model. Indeed, using the accelerated model we observed high expression levels of genes associated with disease severity including interferon stimulating genes (ISGs), which were similarly elevated in human gastric tumor samples.1 However, even with the presence of inflammatory response in the accelerated model, due to the absence of MyD88, caution should be exercised when interpreting findings from immunological and immunotherapeutic studies. This is the limitation of the model. Nevertheless, the accelerated model is a valuable asset for carrying out gastric cancer related studies given that it exhibits high activation of genes that are also highly expressed in patient gastric cancer biopsy samples and it shortens the window for Helicobacter infection disease transformation.

Troubleshooting

Problem 1

When growing H. felis in the liquid culture there is a possibility that the bacteria might not be enough to inoculate mice to achieve infection (Preparation 1- Growing bacteria to infect mice, step 6).

Potential solution

Increase the amount of medium by expanding the number of T-75 cell flasks used while maintaining a volume of 30 mL per flask. The percent of fetal calf serum in the liquid medium can also be increased to anywhere from 15%–20% and then repeat step 6 of the section on growing bacteria for infection.

Problem 2

Gastric homogenates are not uniform and homogeneous after centrifugation (RNA Extraction, step 24).

Potential solution

Transfer the supernatant containing the non-uniform homogenate, add TRIzol and repeat step 5 of the RNA extraction procedure.

Problem 3

During gavage of mice there might be some loss of bacteria through spilling or/and mice spitting (Preparation 2 – Mouse infections, Step 9).

Potential solution

Problems with liquid spillage and mouse spitting are usually a result of improper restraining of the mouse. To achieve this, hold the mouse in a vertical position and gently grasp the mouse by the loose skin over the neck and back and immobilize the head.

Problem 4

Gastric tissue lifts or peels off the slide (Fixing tissue sections before paraffin embedding, step 4).

Potential solution

Make sure the slides are very clean. Use charged slides.

Problem 5

Gastric tissue is not completely pulverized (RNA Extraction, Step 23).

Potential solution

Make sure that the gastric tissue is frozen and that the tissue pulverizer is completely frozen before adding the tissue to pulverize.

Resource availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Marygorret Obonyo (mobonyo@health.ucsd.edu).

Technical contact

Questions about the technical specifics of performing the protocol should be directed to the technical contact, Prerna Bali (pbali@health.ucsd.edu).

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

-

•

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

Single-cell RNA-seq data have been deposited at GEO and is publicly available as of the date of publication. The accession number is listed in the key resources table.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by funding from the Department of Defense (DOD) award W81XWH-20-1-0675 to M.O. The graphical abstract and figures were created using Biorender.com.

Author contributions

M.O. supervised and designed the study concept and research; C.B. supervised data analysis; P.B., I.L.-P., and J.H. collected and analyzed data; M.V.E. performed mouse histopathologic scoring; P.B. and I.L.-P. wrote the draft of the manuscript; C.B. and M.O. revised the manuscript. All authors read and approved the manuscript.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.xpro.2024.103302.

Supplemental information

References

- 1.Bali P., Lozano-Pope I., Hernandez J., Estrada M.V., Corr M., Turner M.A., Bouvet M., Benner C., Obonyo M. TRIF-IFN-I pathway in Helicobacter-induced gastric cancer in an accelerated murine disease model and patient biopsies. iScience. 2024;27 doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2024.109457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bali P., Coker J., Lozano-Pope I., Zengler K., Obonyo M. Microbiome Signatures in a Fast- and Slow-Progressing Gastric Cancer Murine Model and Their Contribution to Gastric Carcinogenesis. Microorganisms. 2021;9 doi: 10.3390/microorganisms9010189. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bali P., Lozano-Pope I., Pachow C., Obonyo M. Early detection of tumor cells in bone marrow and peripheral blood in a fastprogressing gastric cancer model. Int. J. Oncol. 2021;58:388–396. doi: 10.3892/ijo.2021.5171. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banerjee A., Thamphiwatana S., Carmona E.M., Rickman B., Doran K.S., Obonyo M. Deficiency of the myeloid differentiation primary response molecule MyD88 leads to an early and rapid development of Helicobacter-induced gastric malignancy. Infect. Immun. 2014;82:356–363. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01344-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mejias-Luque R., Lozano-Pope I., Wanisch A., Heikenwalder M., Gerhard M., Obonyo M. Increased LIGHT expression and activation of non-canonical NF-kappaB are observed in gastric lesions of MyD88-deficient mice upon Helicobacter felis infection. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:7030. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-43417-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nyan D.C., Welch A.R., Dubois A., Coleman W.G., Jr. Development of a noninvasive method for detecting and monitoring the time course of Helicobacter pylori infection. Infect. Immun. 2004;72:5358–5364. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.9.5358-5364.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rogers A.B., Taylor N.S., Whary M.T., Stefanich E.D., Wang T.C., Fox J.G. Helicobacter pylori but not high salt induces gastric intraepithelial neoplasia in B6129 mice. Cancer Res. 2005;65:10709–10715. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-1846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chen S., Zhou Y., Chen Y., Gu J. fastp: an ultra-fast all-in-one FASTQ preprocessor. Bioinformatics. 2018;34:i884–i890. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bty560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dobin A., Davis C.A., Schlesinger F., Drenkow J., Zaleski C., Jha S., Batut P., Chaisson M., Gingeras T.R. STAR: ultrafast universal RNA-seq aligner. Bioinformatics. 2013;29:15–21. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bts635. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinz S., Benner C., Spann N., Bertolino E., Lin Y.C., Laslo P., Cheng J.X., Murre C., Singh H., Glass C.K. Simple combinations of lineage-determining transcription factors prime cis-regulatory elements required for macrophage and B cell identities. Mol. Cell. 2010;38:576–589. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.05.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Love M.I., Huber W., Anders S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol. 2014;15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou Y., Zhou B., Pache L., Chang M., Khodabakhshi A.H., Tanaseichuk O., Benner C., Chanda S.K. Metascape provides a biologist-oriented resource for the analysis of systems-level datasets. Nat. Commun. 2019;10:1523. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-09234-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.van Doorn N.E., Namavar F., Sparrius M., Stoof J., van Rees E.P., van Doorn L.J., Vandenbroucke-Grauls C.M. Helicobacter pylori-associated gastritis in mice is host and strain specific. Infect. Immun. 1999;67:3040–3046. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.3040-3046.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smythies L.E., Waites K.B., Lindsey J.R., Harris P.R., Ghiara P., Smith P.D. Helicobacter pylori-induced mucosal inflammation is Th1 mediated and exacerbated in IL-4, but not IFN-gamma, gene-deficient mice. J. Immunol. 2000;165:1022–1029. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.165.2.1022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cai X., Carlson J., Stoicov C., Li H., Wang T.C., Houghton J. Helicobacter felis eradication restores normal architecture and inhibits gastric cancer progression in C57BL/6 mice. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1937–1952. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.02.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fox J.G., Li X., Cahill R.J., Andrutis K., Rustgi A.K., Odze R., Wang T.C. Hypertrophic gastropathy in Helicobacter felis-infected wild-type C57BL/6 mice and p53 hemizygous transgenic mice. Gastroenterology. 1996;110:155–166. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v110.pm8536852. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Houghton J., Stoicov C., Nomura S., Rogers A.B., Carlson J., Li H., Cai X., Fox J.G., Goldenring J.R., Wang T.C. Gastric cancer originating from bone marrow-derived cells. Science. 2004;306:1568–1571. doi: 10.1126/science.1099513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tu S., Bhagat G., Cui G., Takaishi S., Kurt-Jones E.A., Rickman B., Betz K.S., Penz-Oesterreicher M., Bjorkdahl O., Fox J.G., Wang T.C. Overexpression of interleukin-1beta induces gastric inflammation and cancer and mobilizes myeloid-derived suppressor cells in mice. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:408–419. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang T.C., Goldenring J.R., Dangler C., Ito S., Mueller A., Jeon W.K., Koh T.J., Fox J.G. Mice lacking secretory phospholipase A2 show altered apoptosis and differentiation with Helicobacter felis infection. Gastroenterology. 1998;114:675–689. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(98)70581-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Obonyo M., Rickman B., Guiney D.G. Effects of myeloid differentiation primary response gene 88 (MyD88) activation on Helicobacter infection in vivo and induction of a Th17 response. Helicobacter. 2011;16:398–404. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-5378.2011.00861.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rogers A.B. Histologic scoring of gastritis and gastric cancer in mouse models. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;921:189–203. doi: 10.1007/978-1-62703-005-2_22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ericksen R.E., Rose S., Westphalen C.B., Shibata W., Muthupalani S., Tailor Y., Friedman R.A., Han W., Fox J.G., Ferrante A.W., Jr., Wang T.C. Obesity accelerates Helicobacter felis-induced gastric carcinogenesis by enhancing immature myeloid cell trafficking and TH17 response. Gut. 2014;63:385–394. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2013-305092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hook-Nikanne J., Aho P., Karkkainen P., Kosunen T.U., Salaspuro M. The Helicobacter felis mouse model in assessing anti-Helicobacter therapies and gastric mucosal prostaglandin E2 levels. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 1996;31:334–338. doi: 10.3109/00365529609006406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

-

•

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request.

-

•

Single-cell RNA-seq data have been deposited at GEO and is publicly available as of the date of publication. The accession number is listed in the key resources table.

-

•

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.