Abstract

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is the deliberate damage caused to one’s own body tissue, without the intent to die. Voluntary disclosure of one’s NSSI can catalyze help-seeking and provision of support, although what informs the decision to disclose NSSI is not yet well understood. There is currently no existing framework specific to the process of NSSI disclosure, and the aim of this study was to assess the fit between factors involved in the decision to disclose NSSI and two broader frameworks of disclosure: the Disclosure Decision-Making and Disclosure Processes models. A directed content analysis was used to code interview transcripts from 15 participants, all of whom were university students aged between 18 and 25 (M = 20.33, SD = 1.88), with 11 identifying as female. All participants had lived experience of NSSI which they had previously disclosed to at least one other person. All codes within the coding matrix, which were informed by the disclosure models, were identified as being present in the data. Of the 229 units of data, 95.63% were captured in the existing frameworks with only 10 instances being unique to NSSI disclosure. Though factors that inform the decision to disclose NSSI largely align with the aforementioned models of disclosure, there are aspects of disclosure decision-making that may be specific to NSSI.

Key words: self-injury, NSSI, disclosure

Introduction

Non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) is the intentional damage to an individual’s own body tissue in the absence of suicidal intent (International Society for the Study of Self-Injury, 2022). Although NSSI can be diverse in form, skin cutting, burning, and self-battery are among the most frequently reported methods (Swannell et al., 2014). Similarly, there is a range of functions that NSSI may serve, with emotion regulation being most commonly reported (Taylor et al., 2018). A relatively common behavior— approximately 17.2% of adolescents, 13.4% of young adults, and 5.5% of adults—report a life-time history of NSSI (Swannell et al., 2014). More recently, rates of NSSI among adolescents and adults, respectively, have been reported at 32.4% and 15.7% (Deng et al., 2023). Negative outcomes such as later suicidal thoughts and behavior and mental health difficulties (e.g., anxiety and depression) are associated with lived experience of NSSI, presenting a potential need for supports (Fox et al., 2015; Kiekens et al., 2018). Although disclosure is not always pursued nor desired, NSSI disclosure can act as a catalyst for seeking and/or accessing support (Simone & Hamza, 2020; Mirichlis et al., 2023). However, factors that inform the decision to disclose NSSI are largely unknown. If we wish to appropriately respond to and support people who self-injure, inquiry into factors that facilitate disclosure is needed.

It is estimated that on average, 50-60% of individuals who have self-injured will disclose this to another person (Simone & Hamza, 2020). Previous findings suggest that disclosing NSSI to seek tangible aid may be of greater relevance when disclosing to health professionals, though the majority of NSSI disclosures are made to one’s friends, significant others, and/or families (Mirichlis et al., 2023; Simone & Hamza, 2020). Interpersonal factors, such as the quality of the relationship, may be more important in the decision to disclose to family or friends (Mirichlis et al., 2022). Additionally, NSSI disclosures may facilitate benefits other than support provision, such as opportunities for self-advocacy and to explore NSSI recovery. Such self-advocacy may reflect challenging the stigma towards NSSI, with disclosure offering opportunities for NSSI to be better understood from lived experience perspectives (Mirichlis et al., 2023). Further, disclosing one’s NSSI can open dialogues to consider what recovery may look like for an individual and how this could be fostered (Hasking et al., 2023).

Although the potential to challenge NSSI stigma may empower some individuals to disclose their NSSI, anticipation and internalization of others’ negative perceptions about NSSI can still pose considerable barriers to such disclosure (Mirichlis et al., 2023; Simone & Hamza, 2020). Anticipated NSSI stigma refers to the expectation of a negative reaction from others, such as being judged or rejected due to their NSSI, even in the absence of no prior stigmatizing experience (Staniland et al., 2022). Conversely, an individual may internalize stigmatizing views about NSSI and thus feel ashamed to disclose their NSSI (Simone & Hamza, 2020). Indeed, there is evidence of discrimination (e.g., being judged) and disruptions to relationships (e.g., introducing tension in friendships) following NSSI disclosures (Park et al., 2020; Staniland et al., 2022). While identification of these barriers provides some insight into what might inform the decision to not disclose NSSI, a more comprehensive approach to understanding and navigating NSSI disclosures could be instrumental in providing more appropriate support for individuals with lived experience of NSSI (Simone & Hamza, 2020). Having a theoretically informed understanding of NSSI disclosure decision-making would offer a process and set of factors to consider when navigating disclosures and could potentially improve outcomes following disclosures (Stratton et al., 2019). Currently, no such framework exists for NSSI disclosure, although insight may be gleaned from broader frameworks pertaining to the disclosure of personal information, such as the Disclosure Decision-Making Model (Greene, 2009) and the Disclosure Processes Model (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010).

Frameworks of personal information disclosure

Although not conceptualized specifically for NSSI, the Disclosure Decision-Making (Greene, 2009) and Disclosure Processes (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010) models each present a range of considerations people undertake when deciding to disclose personal and often stigmatized information. In the Disclosure Decision-Making Model, the “what?” and the “who?” of disclosures are considered, with reference to stigmatized health conditions such as HIV. Adopting a medical approach to disclosure decisions, Greene (2009) posits that individuals may consider whether the condition/experience is stigmatized, the prognosis of the condition (or in the case of NSSI, the course of the behavior such as the frequency, recency, or self-defined “recovery”), symptomatology (or visibility, e.g., NSSI scarring), and the relevance of this information to others (i.e., to what extent other people are somehow impacted by this experience). Greene (2009) also proposes that when deciding whether to disclose personal information, individuals may evaluate confidants in terms of the quality of their relationship and how they might be expected to respond to the disclosure. Further, Greene (2009) discusses an individual’s self-efficacy to disclose, taking into consideration such factors as ability to articulate their message. These considerations appear applicable to NSSI disclosure stigma being an established barrier to its disclosure (e.g., Rosenrot & Lewis, 2020) and to NSSI disclosure being associated with more impactful NSSI (i.e., causing distress to and/or inference with important aspects of the individual’s life such as in their interpersonal relationships), the presence of NSSI scarring, and reports of people adopting different approaches to disclosure depending on the recipient (Mirichlis et al., 2022; 2023; Simone & Hamza, 2020).

Complementing this focus on what to disclose and to whom, Chaudoir and Fisher (2010) consider the “when?” and the “why?” in their Disclosure Processes Model. Specifically, the “when” and “why” are operationalized as “Approach-Focused Goals” (i.e., those which aim for movement towards positive outcomes) and “Avoidance-Focused Goals” (i.e., those which aim to move away from negative outcomes). The motivations for NSSI disclosure are not yet well understood, although reports of disclosing NSSI online to seek validation from others may offer an example of approach-focused goals. In contrast, disclosing NSSI online as a means of resisting urges to self-injure could exemplify goals which are avoidance-focused (Lewis et al., 2012; Lewis & Seko, 2016). Additionally, Chaudoir and Fisher (2010) outline considerations of the disclosure event itself such as the depth, breadth, and duration of a disclosure, with the framework being applied to a range of stigmatized groups such as individuals who have experienced mental illness and users of alcohol and other drugs (Barth & Wessel, 2022; Earnshaw et al., 2019).

Together, the Disclosure Decision-Making and Disclosure Processes models may provide a framework for understanding the “what,” “who,” “when,” and “why” of NSSI disclosure decision-making, offering a tool to better synthesize understandings of NSSI disclosure and to support NSSI disclosure efforts. Using content analysis and drawing from existing data (Mirichlis et al., under review; see Method), the aim of the current study was to assess the fit between factors that informed the decision to disclose NSSI and the Disclosure Decision-Making and Disclosure Processes Models. As such, the research question was: To what degree do factors that inform the decision to disclose NSSI align with existing disclosure frameworks? Fitting with the deductive approach of this study, it was hypothesised that NSSI disclosure decision-making would align with the superordinate considerations collectively outlined in the Disclosure Decision-Making and Disclosure Processes models (related to the information being disclosed, who to disclose to, one’s confidence in their ability to disclose, and disclosure being goal-driven).

Materials and Methods

Participants

The sample comprised 15 participants with lived experience of NSSI who had voluntarily disclosed this to at least one other person. All participants were Australian university students, with nine being recruited from the university’s research participation pool in which studies are advertised to psychology students who receive course credits for their participation. These participants could sign up for a study slot, at which point they were contacted by the first author to arrange an interview booking. The remaining participants were recruited from an existing pool of individuals interested in NSSI research, and these participants were contacted via email to confirm their interest in participating in this study. Participants recruited the latter way received a gift-card as reimbursement for their time. The sample comprised 11 females and four males, aged 18 to 25 years (M = 20.33, SD = 1.88).

Procedure

Upon receiving ethical approval, individuals who expressed interest in the study were emailed the information sheet, and a mutually convenient interview time was arranged with each participant. To maintain confidentiality, participants provided informed consent in an audio recording separate from that of the recorded interview. The semi-structured interviews ran between 30 and 60 minutes. Participants were asked to describe NSSI in their own words before the interviewer asked them about their experiences of voluntarily disclosing their NSSI. (See Table 1 for a summary of the interview questions relevant to this study.) Once the interview concluded and the recording was stopped, participants were provided with debriefing information including contacts for emotional support services and information about NSSI. All interview recordings were later transcribed verbatim. De-identified transcripts were stored securely, and audio recordings were destroyed. As these interviews were part of a broader study (Mirichlis et al., under review), these transcripts featured participants’ disclosure experiences as a whole, inclusive of participants’ considerations leading to their disclosures.

Table 1.

Core interview questions and probes.

| Prior to disclosure |

|---|

| 1. Were they the first person you talked to about your self-injury? |

| A. As far as you know does this mean they were also the first person to know about it? |

| B. If not, was other people knowing a contributing factor to you telling this person? |

| 2. Could you tell me a bit about what your relationship with this person was like prior to them learning about your experience with self-injury? |

| 3. What prompted your decision to disclose your self-injury? A. Were there any specific reasons why you wanted to talk to this person in particular about it, rather than talking to somebody else? |

| 4. Was there anything that made you hesitant at first to disclose your self-injury to this person? A. How did you overcome this/what changed your mind? |

| 5. What were you expecting to happen when you told this person? |

| A. What other thoughts or feelings did you have right when you were about to tell this person? |

| B. What were you hoping would happen? |

| C. Why do you think this is? |

Analysis and rigor

A directed content analysis was used to assess the fit between frameworks of personal information disclosure and the decision to disclose NSSI (Elo & Kyngas, 2008; Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). Directed content analysis is a useful qualitative tool for examining existing theoretical frameworks via deductively coding data against codes prescribed by said theory (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005). In order to address our research aim, the Disclosure Decision-Making Model (Greene, 2009) and the Disclosure Processes Model (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010) were used to develop a theoretically informed coding matrix in Microsoft Excel. Elements of both models were combined in a single coding matrix. As seen in Table 2, higher-order categories reflecting the broad components of these frameworks (e.g., about the information being disclosed, interpersonal characteristics, etc.), were further organized into subordinate codes reflecting more specific aspects of the frameworks (e.g., stigma). In accordance with the aim of this study, to understand the decision to disclose the stigmatized behaviour of NSSI, the labels of some of these categories and codes have been adapted from the original models to more appropriately denote NSSI experiences in a way that does not pathologize the behavior. For example, rather than referring to “prognosis” and “symptomatology,” as Greene (2009) does, the coding matrix features “course” and “visibility” of NSSI, in line with the NSSI stigma framework developed by Staniland et al. (2021).

Table 2.

Description of categories and codes.

| Categories | Category description | Codes | Code description |

|---|---|---|---|

| NSSI characteristics | The specific characteristics or features of NSSI that may alter one’s decision to disclose their NSSI. | Stigma | Negative perceptions of NSSI that alter one’s decision to disclose their NSSI. |

| Course | The occurrence or progression of NSSI that may alter the decision to disclose about NSSI. | ||

| Visibility | Notable features (e.g., scarring) of NSSI that may affect the trajectory of disclosure. | ||

| Interpersonal characteristics | Consideration for disclosing NSSI in relation to the potential disclosure recipient. | Relevance | Consideration of the direct or indirect impacts that the disclosed information may have on the recipient. |

| Relational quality | The relational dynamics and context with the disclosure recipient (e.g., level of trust). | ||

| Anticipated reactions | The expected response from the disclosure recipient. | ||

| Disclosure self-efficacy | The perceived ability to disclose NSSI experiences. | ||

| Disclosure Goals | Underlying motives for disclosing self-injury. | Approach/positive focus | Perceptions that disclosure may facilitate positive outcomes such as increased understanding or acceptance from the disclosure recipient. |

| Avoidance/negative focus | Perceptions that disclosure may protect against negative outcomes such as preventing conflict and experiences of negative affect. |

Interview transcripts were exported into Microsoft Excel and segmented into codable data units to be mapped to the conceptual matrix. The transcripts were segmented so that each data unit represented a shift in meaning or topic (Campbell et al., 2013). Each data unit (n = 277) was labelled with a code that represented its analytically relevant content. A single data unit could be coded multiple times as in the following example: “He’s my partner, and because the first encounter was quite positive (relational quality) […] that kind of led me to have a bit more reassurance in that I’ll be able to tell him again (self-efficacy).” This data unit captured the disclosure experiences relevant to both relational quality and self-efficacy.

In addition to considering how data was to be segmented, the coding team consulted methodological literature to inform what data was coded. With reference to Elo and Kyngas (2005) a mixture of manifest and latent codes were used. The additional context offered by the richness of interview data supported the feasibility of taking this combined approach. Although the focus of this study is on existing disclosure frameworks, data that did not fit within the existing coding matrix was assigned the code of Other as per Hsieh and Shannon’s (2005) recommendations. Data coded as Other offer insight into factors that inform NSSI disclosure which have not been accounted for in the existing frameworks.

With the aim of maximizing rigor, a second coder independently coded 10% of the data. This subsample was randomly selected to enable representation from the full dataset. Interrater reliability was obtained by comparing the same data units, coded by the primary and secondary coder. Intercoder reliability was calculated with Gwet’s AC1 coefficients and ranged between < -0.00 and 1 (M = .66, SD = .30), indicating good intercoder reliability on average (Gwet, 2014). The coders discussed the coding discrepancies (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020) and proceeded to a second round of independent coding—a further 10% of randomly selected data. Following this second round of intercoder reliability, Gwet’s AC1 ranged from .69 to .96 (M = .90, SD = .09), indicating an excellent level of agreement (Gwet, 2014). The remaining discrepancies were again discussed until resolved (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020). The final data set, after coding was finalized, consisted of 229 data units. In addition to secondary coding, both coders engaged in reflective journaling and maintained an audit trail throughout the research process (O’Connor & Joffe, 2020). To ensure the validity of the data, interview transcripts underwent member checking, wherein full transcripts were provided to participants to check for accuracy.

Results

Factors involved in the decision to disclose NSSI aligned with broader existing frameworks of disclosure decision-making, with 95.63% of data units (i.e., individual excerpts) being captured by aspects of the two disclosure frameworks examined. There were 10 data units (4.37%) that discussed considerations of NSSI disclosure decision-making that were not at all captured by the existing disclosure frameworks. A further 54 (23.58%) instances of data were also coded as “other” such that some parts of the excerpt were relevant to elements of the frameworks and other portions were not. The findings relevant to the existing disclosure frameworks are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Frequency of categories and codes, and code examples.

| Categories | Codes | n | % | Code Examples |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSSI characteristics (n = 59, 25.76%) | Stigma | 23 | 10.04 | “It’s [NSSI] still a stigmatized issue a lot of the time, so it could still be something that people could react really negative to. There is that worry of the stigma that you might receive for talking about it.” |

| Course | 21 | 9.17 | “I told one of my friends about it because I was starting to worry that it wasn’t just a one-time thing.” | |

| Visibility | 15 | 6.55 | “No one else had known that I’d done it either because mine [self-injury] were like hidden.” | |

| Interpersonal characteristics (n = 202, 88.21%) | Relevance | 62 | 27.07 | “She is one of my best friends and she’s been there for me through everything so she should know.” |

| Relational quality | 81 | 35.37 | “She created this really safe space where I could tell her what was happening.” | |

| Anticipated reactions | 59 | 25.76 | “I was scared to tell someone because I didn’t want them to think of me as some like depressed child.” | |

| Disclosure self-efficacy (n = 48, 20.96%) | - | - | “I think after you tell one person it just becomes easier to tell other people.” | |

| Disclosure goals (n = 73, 31.88%) | Approach/positive focus | 48 | 20.96 | “I would disclose to them … because on one hand they may be more understanding about the situation and … they might be more accepting to the next person who discloses to them.” |

| Avoidance/negative focus | 25 | 10.92 | “I was a bit nervous to sort of disclose that information to a complete stranger, but I felt that it was probably important too, I guess. So they could help me stop doing that.” |

n, number of times the code was used; %, the percentages out of the 229 data unit.

NSSI characteristics

Characteristics specific to participants’ NSSI were referenced in 25.76% of the data units (n = 59). The code of NSSI Stigma was present in 23 of the data units (10.04%), highlighting instances where this key barrier to disclosure was overcome in pursuit of disclosing NSSI. For example, one participant (aged 18 years, male) reflected that although they confided their NSSI to a particular friend, they were mindful that, “it’s not really acceptable for you to display that kind of weakness.” Further, this participant reflected that

I was nervous because of the stigma because I know before then I had been accidentally found out, and it hadn’t gone well, and I think […] with general in the media and stuff and hearing how friends’ parents had reacted to stuff like that.

This participant’s quote provides insight into how different sources of NSSI stigma (i.e., direct and indirect experiences of NSSI stigmatization) may impact their consideration of disclosing their NSSI. Akin to Greene’s (2009) notion of considering the prognosis of a health condition to be disclosed, the course of one’s NSSI was referenced in 21 data units (9.17%). These references reflected aspects of the behaviour such as the frequency, recency, and perceived controllability or severity of one’s NSSI. In some instances, the course of the NSSI at the time of the disclosure may have also linked to the perceived relevance (as coded below) of disclosing to a particular person as highlighted by this participant (aged 25 years, male): “The first time I had to go to hospital was when it was the worst, but before that, it was just more mild, in which I didn’t need any attention, so I didn’t tell anyone about it.” Other participants reflected on how the extended time that had elapsed since engaging in NSSI contributes to contemporary disclosure. For example, a female participant (aged 21 years) said, “I feel more open about it now actually. Since not engaging it, I have told more people about it, whereas when I was [still engaging], there was that concern of what if someone [sic]- I wasn’t ready for that.” Relatedly, the visibility of one’s NSSI as a proxy to Greene’s (2009) reference to “symptoms” was coded in 15 data units (6.55%). This included references to scarring, lack of concealment/area of the body, and openness about NSSI in peer groups. One female participant (aged 21 years) noted that, “it’s pretty clear like I have scars all over me. You can tell, but I don’t think I’ve ever told many of my friends.” Another participant’s (female, aged 18 years) reflection is illustrative other ways NSSI can be visible: “if you have a bandage on your wrist, people are, like, going to ask about it. If you have it open, people are going to ask about it.” These varying forms of NSSI visibility appear to inform disclosure decision-making in different ways. For some individuals, the visibility of their NSSI seems make explicitly disclosing this experience redundant, whereas others acknowledge that visibility may be the catalyst for disclosure.

Interpersonal characteristics

The most commonly coded category was adapted from Greene’s (2009) reference to assessing the recipient of a potential disclosure. Interpersonal characteristics were coded in 88.21% of data units (n = 202). Relevance of disclosing one’s NSSI to a particular recipient was coded in 62 data units (27.07%), often coinciding with the code of Relationship Quality (n = 81; 35.37%). The latter code reflects the type of, and closeness of, the relationship with the disclosure recipient, with participants sometimes noting that these factors informed their assessment of the relevance of their NSSI disclosure. For example, one female participant (aged 21 years) stated, “part of me felt like I owed it to him to be honest with him because of the relationship” when recounting their experience of disclosing their NSSI to their partner. Other participants reflected on the “mateship” within their relationships with disclosure recipients, noting that they were “very close friends” and a “trusted ally.” A further consideration in whom to disclose information to adapted from both the Disclosure Decision-Making and Disclosure Processes Models (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010; Greene, 2009) was the code of Anticipated Reactions. This code was present in 59 data units (25.76%) with participants citing both anticipated reactions that encouraged their disclosure and those which were potential barriers that they had overcome. For example, a female participant (aged 19 years) reflected, “how will they react? What will they think? What are we going to do from here?” Conversely, another female participant (aged 22 years) reflected on the positive expectations they had when considering disclosing their NSSI: “I knew that she would understand where I was coming from and wouldn’t judge me.” These participants’ considerations of how their NSSI disclosures could be reacted to reflect barriers and facilitators of disclosure reported in the literature so that, for some, negative expectancies can hinder NSSI disclosures, whereas, for others, a sense of trust can be a catalyst for NSSI disclosure (Mirichlis et al., 2023; Simone & Hamza, 2020).

Disclosure self-efficacy

Confidence in the ability to disclose self-efficacy (i.e., self-efficacy to disclose NSSI) was coded 48 times (20.96%). Considerations raised by participants included a general lack of confidence (or general anxiety) about how to approach disclosure, with some citing a preference for being prepared for what to expect of the disclosure experience. For example, a female particiapant (aged 19 years) said, “I think when you go into a situation knowing what the consequences are and what the results will be, it just feels a lot better,” although, for others, “even with the heads up, it was still difficult to talk about it” (male, aged 25 years). Relatedly, some mentioned that with experience, disclosures became easier, and others noted how the means of disclosure (i.e., via online/text message rather than face-to-face or having a casual rather than formal conversation) may facilitate disclosure. For example, one female participant (aged 21 years) noted that

I honestly think that everything is easier online. I’m not that kind of person to do that sort thing online anymore, though, but it’s a lot easier to talk to a screen than it is to actually to be faced with someone who has emotions and reactions and their own thoughts.

In addition to explicating that digital technologies can assist NSSI disclosure, this participant sheds light on what aspects of disclosing NSSI online may contribute to one’s self-efficacy to do so.

Disclosure goals

In considering the decision-making process of disclosure, Chaudoir and Fisher (2010) describe both approach-focused and avoidance-focused goals reflecting the functional nature of disclosing information. Overall, these goals were coded 73 times (31.88%) in the data units. Approach-focused goals, i.e., those which seek out positive outcomes, were the most commonly coded (n = 48, 20.96%). Some goals cited by participants included seeking tangible and/or emotional support, as well as more broadly seeking acceptance and understanding. For example, a female participant (aged 19 years) reflected on seeking “support maybe, knowing that they’re always going to be there when I need them, when I need them to be relied upon. Understanding, no judgement, no pity, maybe empathy would be good.” In contrast, the prevention of negative outcomes via avoidance-focused goals were coded 25 times (10.92%). These avoidant goals included, “stop social outcasting me in the social norm” (male, aged 18 years), reducing negative emotions and/or experiences such as, “in case I got into a dark space where I was struggling to come out of it” (female, aged 20 years), and “once that pattern started, I knew I had to sort of stop it or get help for it, and that’s when I told her” (female, aged 19 years).

Considerations not captured in existing frameworks

In addition to being interested in what aspects of NSSI disclosure decision-making align with existing disclosure frameworks, we were interested in those not captured in these frameworks. Of the 64 instances coded as Other, the following codes were generated, suggesting considerations specific to deciding to disclose NSSI. Some of these new codes did align with the broader categories informed by the existing disclosure frameworks, but not their sub-categories. Within the category of Interpersonal Characteristics, five additional codes were identified. The most common of these pertained to “having an existing mutual understanding with the recipient” (i.e., rather than seeking understanding, n = 6). For example, “It was more just like we both kind of know what we’re going through” (female, aged 18 years). Secondly, a sense of confidence and/or security in the recipient and their ability to respond appropriately to the disclosure was coded five times. Although potentially similar to the Anticipated Reactions code, rather than capturing specific reactions anticipated from a disclosure recipient, this code reflected an assumption of competency on behalf of the recipient. For example, “she dealt with these kind of things before, she was experienced […] she was qualified” (female, aged 19 years). Additionally, a code was identified to capture the potential impact of the disclosure itself on the recipient (n = 3). Such consideration is reflected here: “I imagine it’s not good for people listening either, like it’s a hard process for them” (male, aged 25 years). Codes of the recipient previously knowing of their NSSI via other means (n = 1) and the disclosure being mutual (n = 1) were also identified, albeit rarely.

Within the category of Disclosure Self-efficacy four additional codes were identified. In terms of what may be involved in one’s self-efficacy to disclose their NSSI, a lack of preparation/processing preceding the disclosure was coded four times, with appropriate timing (n = 3) and the setting in which the disclosure takes place (n = 3) also being coded here. For example, one female participant (aged 19 years) reflected that their disclosure occurred when their school was, “looking at mental health awareness, it was r u ok day [a suicide prevention initiative].” Disclosure ambivalence was coded four times across the data set. For example, a female participant (aged 21 years) reflected that they, “didn’t want it [self-injury] to come up, but if it did, I felt relieved,” reflecting a sense of both wanting to and not wanting to disclose their NSSI simultaneously. Such conflict is of interest as it may challenge one’s confidence in whether to disclose their NSSI (Gray et al., 2023).

With relation to the category of Disclosure Goals, two further codes were identified. There were eleven instances of the code of Selectivity/agency and Self-preservation, capturing desires to exert control and protect oneself in future disclosures, as expressed by this female participant (aged 21 years): “The rest of my voluntary disclosures were seen through a lens of ‘What’s the risk to me? I have to be more careful about this. Who’s going to find out?’” Secondly, there were three instances of the code Ambiguous Expectations, such as this female participant’s (aged 18 years) expression: “I don’t know what I was expecting [by disclosing NSSI].”

Two additional categories are proposed based on the identification of further codes which did not fit within the existing disclosure frameworks. Firstly, Individual Characteristics pertains to the person considering disclosing their NSSI. Within this category, the codes of Difficult Emotional Experience/Period (n = 3) and Age at Time of Disclosure (n = 7) were identified. That is to say that some participants referenced that their age at the time of disclosure and going through a difficult experience when disclosing their NSSI informed their disclosure decisions. For instance, a female participant (aged 21 years) reflected on how being an adolescent informed their past disclosure decision-making: “I wouldn’t have wanted to talk to them about it. I was young. Adults are so unrelatable when you’re a kid or a teenager. You just think they don’t know anything they’re talking about and now being an adult.” Another female participant (aged 19 years) reflected on how their personal experience prompted their disclosure: “I was just having a rough day. So we were kind of talking about it, and then I think that’s how it [NSSI] came up.”

Finally, the category of Disclosure Course captures instances when participants specifically referenced the trajectory of NSSI disclosure. The most common code of this category is the ongoing nature of disclosure (n = 32). Here, participants highlight that disclosure is not necessarily a single discrete event. For example, a female participant (aged 18 years) recounted the various people they had disclosed their NSSI to:

I went to my GP first because of other things, and that [NSSI] came up. Because we were trying to figure out what was going on, and that came up. And then I went.... I was, like, referred to a psychiatrist and psychologist and stuff. And then I was telling my friend about [my self-injury].

Although participants had disclosed their NSSI voluntarily, some noted that the conversation had been prompted by recipients, for example, by being asked whether they had self-injured or from broader wellbeing check-ins (n = 14). Further, whether this would be an individual’s first time disclosing their NSSI may warrant consideration, as participant explicitly stated that the disclosure experience they were reflecting upon was the first (but not only) time they had told another person about their NSSI.

Discussion

Despite a growing body of literature which has explored decision-making regarding NSSI disclosure (e.g., Fox et al., 2022; Mirichlis et al., 2022; Simone & Hamza, 2020), there is currently no conceptual framework specific to NSSI to guide this research. Two previously mentioned, well-established frameworks of personal information disclosure, the Disclosure Decision-Making Model (Greene, 2009) and the Disclosure Processes Model (Chaudoir & Fisher, 2010) feature dynamic processes by which individuals evaluate information when deciding whether to disclose personal information. Namely, these theorists stipulate that characteristics of the information itself and of the disclosure recipient, the individual’s self-efficacy to disclose the information, and the goals of the disclosure are considered in disclosure decisions. We aimed to investigate whether factors that inform the decision to disclose NSSI align with these frameworks following Hsieh and Shannon’s (2005) process of directed content analysis. The current findings indicate that considerations of NSSI disclosure decision-making were largely captured in the combination of the two existing frameworks. At the same time, several additional considerations suggest that these extant frameworks alone are not sufficient in conceptualizing NSSI disclosure decisions.

Consistent with our hypothesis, the majority of NSSI disclosure considerations mentioned by participants were captured in the existing frameworks, although the specific ways these were expressed differed from the broader models. Of the considerations from the existing disclosure frameworks, the most commonly coded category was Interpersonal Considerations which featured the most frequently used code: Relational Quality. This aligns with previous research in which individuals with lived experience of NSSI rated interpersonal considerations of greatest importance to the decision to disclose NSSI, with quality of the relationship with a disclosure recipient being rated the second most important (Mirichlis et al., 2023). Of note for the current study, data coded into Relational Quality were often also coded into Relevance. It is plausible that this coincident of the Relational Quality and Relevance codes reflects the sensitive nature of NSSI disclosure such that one’s NSSI may only be deemed relevant to a chosen disclosure recipient if their relationship with the person disclosing necessitates such sharing. There appears to be merit in also considering the relevance of the information itself, with the Course code also co-occurring with Relevance. This may reflect the relationship between frequency and/or severity of NSSI and NSSI disclosures whereby more severe NSSI is more likely to be disclosed (Simone & Hamza, 2020). Further, some individuals may find disclosure less relevant if they have not recently engaged in NSSI (Mirichlis et al., 2022).

The least frequently coded category in the current study was that of Disclosure Self-Efficacy. One’s confidence in their ability to disclose NSSI has received little empirical attention. Nevertheless, it may have relevance among people with lived experience. In a previous study in which individuals with lived experience rated the importance of various factors to the decision to disclose their NSSI, their confidence to talk about their NSSI was rated as the third most important factor (Mirichlis et al., 2023). It is plausible that some factors contributing to one’s self-efficacy to disclose their NSSI were instead captured in the other categories. For example, an individual may feel more confident in their ability to disclose their NSSI to someone that they have a close relationship with and that may have been coded under Relationship Quality. As such, further research is warranted into the factors underlying one’s self-efficacy to disclose NSSI. The least commonly reported code in this content analysis was the visibility of one’s NSSI potentially reflecting the focus on voluntary disclosure in this study rather than involuntary disclosure/discoveries due to one’s NSSI being visible (e.g., by way of scarring [Pugh et al., 2023]). Further, it may be the case that many of our participants did not perceive their NSSI to be visible, and, as such, this was not a common consideration when they decided to disclose their experience.

Considerations beyond existing frameworks

The identification of codes and categories beyond those captured in the existing disclosure frameworks suggest the potential merit of extending upon current theoretical approaches when considering disclosure of NSSI. Of note, the Individual Characteristics category suggests the importance of considering an individual’s own characteristics when navigating a disclosure. This fits intuitively with a person-centred approach, characterized by prioritizing a person’s individual lived experience as opposed to taking a universal approach to understanding NSSI (Lewis & Hasking, 2023). Given the experiential nature of disclosing information and emerging findings that previous disclosure experiences can inform—and indeed predict—future NSSI disclosures (Mirichlis et al., 2023; Simone & Hamza, 2021), the identification of the Disclosure Course category appears of relevance when navigating and researching disclosure as an ongoing and dynamic process. Additional research could provide greater insights into these emerging considerations for NSSI disclosure decision-making.

A NSSI-Specific Framework

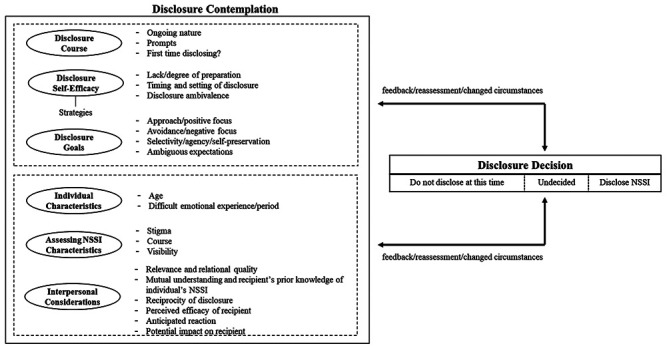

While our findings offer support for the Disclosure Decision-Making and Disclosure Processes models, evidently there are additional considerations when conceptualizing NSSI disclosure decision-making. We therefore propose a more comprehensive framework in the form of the NSSI Disclosure-Decisions Framework. In this framework (depicted in Figure 1), we aim to merge and extend upon the factors of the Disclosure Decision-Making and Disclosure Processes models to present a framework specific to NSSI disclosure. The considerations involved in the decision to disclose NSSI are outlined in the Disclosure Contemplation box and are arranged according to the categories discussed in the findings of this study (e.g., Disclosure Course, Assessing NSSI Characteristics, etc.). These categories have been further organized to reflect those broaching the process of disclosure itself (i.e., disclosure course and self-efficacy to disclose and the goals of disclosure) as compared to those pertaining to more contextual factors relevant to the individual in the lower dashed-box (i.e., Individual and NSSI Characteristics, and Interpersonal Considerations). It should be noted that the process by which an individual may consider the factors presented is not necessarily linear. Various factors may be considered in different combinations so that not all factors presented may inform a single disclosure decision at a given time. That is to say that while such frameworks can be helpful in understanding disclosure decision-making, they cannot be universally applied. Rather than being an itemized checklist, the figure may serve as a suggestive guide of what may inform the decision to disclose NSSI. Also of note are the dual-headed arrows linking the contemplation and “Disclosure Decision” boxes. These arrows denote that in addition to the contemplation factors informing disclosure decisions, feedback and other changes at the point of deciding whether to disclose NSSI may inform future decision-making. Taken together, this framework is illustrative of a disclosure process which varies both contextually (e.g., between different disclosure recipients and settings) and temporally (e.g., subsequent disclosures to the same recipient over time).

Figure 1.

NSSI disclosure-decisions framework.

Limitations, future research and implications

When interpreting the implications of this research, there are some key limitations to bear in mind. As the direct content analysis was applied to existing transcripts from a previous study, we were limited to the demographic and NSSI history data already collected. Given the reference to “NSSI Characteristics” in the analytical process, further information regarding participants’ experiences of NSSI such as what form of self-injury they had engaged in and how recently, as well as the presence/nature of any NSSI scarring, should be collected when researching NSSI disclosure. Similarly, emerging support for considering individual characteristics in decisions to disclose NSSI further warrants investigation among more diverse samples, including across varied developmental periods, cross-cultural perspectives, and minority groups with elevated rates of NSSI (e.g., LGBTIQ+ individuals [Liu et al., 2019]).

Our findings could have significant implications. Theoretically, the nature and frequency of the considerations aligning with the existing frameworks are suggestive of the utility of these frameworks when investigating NSSI disclosure. The findings indicate that when conceptualizing NSSI disclosure decision-making, considerations about the information being disclosed, the recipient disclosed to, self-efficacy to disclose NSSI, and goals of disclosure should be taken into account. Additionally, novel areas for future research and theoretical expansion have been presented in the identification of new codes and categories captured in the newly proposed NSSI Disclosure-Decisions Framework. As such, future research should investigate these factors as well as further lived experience perspectives on NSSI disclosure decision-making.

The findings present a series of factors for clinicians and support persons to consider with their client/loved one, particularly if the individual with lived experience is uncertain about making such a disclosure. These factors span characteristics of the individual and their NSSI experience, the disclosure recipient and the individual’s self-efficacy to disclose to this person, as well as the goals and course of disclosing NSSI. Any disclosure process should be guided by the individual’s lived experience and goals, such that the decision-making frameworks should be seen as no more than a flexible guide rather than a prescriptive tool for how to disclose NSSI. For example, the framework offers factors to be mindful of such factors as the person’s relationship with a prospective disclosure recipient, and the extent of the relevance of their NSSI to them, though ultimately, it is an individual’s own agency which makes a disclosure voluntary.

Conclusions

In deductively coding NSSI disclosure decision-making factors within existing disclosure frameworks, we have found that such factors tend to align with the key considerations posited in these frameworks. Several additional considerations were identified within the data, which may be specific to disclosing NSSI. These frameworks could offer theroretically informed directions for future NSSI disclosure research and practice, with scope to inform a NSSI-specific disclosure framework. Access to a comprehensive disclosure navigation tool could facilitate support-seeking efforts for individuals with lived experience of NSSI, mitigating negative outcomes associated with the behavior.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

References

- Barth S. E., Wessel J. L. (2022). Mental illness disclosure in organizations: Defining and predicting (un)supportive responses. Journal of Business and Psychology, 37(2), 407–428 [Google Scholar]

- Campbell J. L., Quincy C., Osserman J., Pedersen O. K. (2013). Coding in-depth semistructured interviews: Problems of unitization and intercoder reliability and agreement. Sociological Methods & Research, 42(3), 294-320. [Google Scholar]

- Chaudoir S. R., Fisher J. D. (2010). The disclosure processes model: Understanding disclosure decision making and post-disclosure outcomes among people living with a concealable stigmatized identity. Psychological Bulletin, 136(2), 236-256. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deng H., Zhang X., Zhang Y., Yan J., Zhuang Y., Liu H., Li J., Xue X., Wang C. (2023). The pooled prevalence and influential factors of non-suicidal self-injury in non-clinical samples during the COVID-19 outbreak: A meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders, 343, 109–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Earnshaw V. A., Bergman B. G., Kelly J. F. (2019). Whether, when, and to whom?: An investigation of comfort with disclosing alcohol and other drug histories in a nationally representative sample of recovering persons. Journal of Substance Abuse Treatment, 101, 29–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elo S., Kyngas H. (2008). The qualitative content analysis process. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 62(1), 107-115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K. R., Bettis A. H., Burke T. A., Hart E. A., Wang S. B. (2022). Exploring adolescent experiences with disclosing self-injurious thoughts and behaviors across settings. Research on Child and Adolescent Psychopathology, 50, 669-681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox K. R., Franklin J. C., Ribeiro J. D., Kleiman E. M., Bentley K. H., Nock M. K. (2015). Meta-analysis of risk factors for nonsuicidal self-injury. Clinical Psychology Review, 42, 156-167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray N., Uren H., Staniland L., Boyes E. (2023). Why am I doing this? Ambivalence in the context of non-suicidal self-injury. Deviant Behavior, 44(11), 1682-1700 [Google Scholar]

- Greene K. (2009). An integrated model of health disclosure decision-making. Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gwet K.L. (2014). Handbook of inter-rater reliability (4th Ed.). Advanced Analytics [Google Scholar]

- Hasking P., Lewis S., Tonta K. (2023). A person-centred conceptualisation of non-suicidal self-injury recovery: A practical guide. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 1-22. [Google Scholar]

- Hsieh F., Shannon S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research,15(9), 1277-1288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- International Society for the Study of Self-Injury. (2020). What is self-injury? Available from: https://itriples.org/category/ about-self-injury/ [Google Scholar]

- Kiekens G., Hasking P., Boyes M., Claes L., Mortier P., Auer-bach R., Cuijpers P., Demyttenaere K., Green J., Kessler R., Myin-Germeys I., Nock M., Bruffaerts R. (2018). The associations between non-suicidal self-injury and first onset suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Journal of Affective Disorders, 239, 171-179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S. P., Hasking P. A. (2023). Understanding self-injury: A person-centered approach. Oxford University Press; [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S. P., Heath N. L., Sornberger M. J., Arbuthnott A. E. (2012). Helpful or harmful? An examination of viewers’ responses to nonsuicidal self-injury videos on YouTube. The Journal of Adolescent Health, 51(4), 380-385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis S. P, Seko Y. (2016). A double-edged sword: A review of benefits and risks of online nonsuicidal self-injury activities. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 72(3), 249-262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu R. T., Sheehan A. E. L., Walsh R. F., Sanzari C. M., Cheek S. M., Hernandez E. M. (2019). Prevalence and correlates of non-suicidal self-injury among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 74, 1-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirichlis S., Boyes M., Hasking P., Lewis S. P. (2023). What is important to the decision to disclose nonsuicidal self-injury in formal and social contexts? Journal of Clinical Psychology, 79(8), 1816-1825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mirichlis S., Hasking P., Lewis S. P., Boyes M. E. (2022). Correlates of disclosure of non-suicidal self-injury amongst Australian university students. Journal of Public Mental Health, 21(1), 70-81. [Google Scholar]

- O’Connor C, Joffe H. (2020). Intercoder reliability in qualitative research: Debates and practical guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 19. 1-13. [Google Scholar]

- Park Y, Mahdy J. C, Ammerman B. A. (2020). How others respond to non-suicidal self-injury disclosure: A systematic review. Journal of Community & Applied Social Psychology, 31(1), 107-119. [Google Scholar]

- Pugh R. L., McLachlan K., Lewis S. P. (2023). Understanding the impact of involuntary discoveries of nonsuicidal self-injury: a thematic analysis, Counselling Psychology Quarterly, Advanced Online Publication, 1-22. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenrot S. A., Lewis S. P. (2020). Barriers and responses to the disclosure of non-suicidal self-injury: A thematic analysis. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 33(2), 121-141. [Google Scholar]

- Simone A. C, Hamza C. A. (2020). Examining the disclosure of nonsuicidal self-injury to informal and formal sources: A review of the literature. Clinical Psychology Review, 82, 1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staniland L., Hasking P., Boyes M., Lewis S. (2021). Stigma and nonsuicidal self-injury: Application of a conceptual framework. Stigma and Health, 6(3), 312-323. [Google Scholar]

- Staniland l., Hasking P., Lewis S. P., Boyes M., Mirichlis S. (2022). Crazy, weak, and incompetent: A directed content analysis of self-injury stigma experiences. Deviant Behavior, 44(2), 278-295. [Google Scholar]

- Stratton E., Choi I., Calvo R., Hickie I., Henderson C, Harvey S. B., Glozier N. (2019). Web-based decision aid tool for disclosure of a mental health condition in the workplace: A randomised controlled trial. Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 76(9), 595-602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swannell S. V., Martin G. E., Page A., Hasking P., St John N. J. (2014). Prevalence of nonsuicidal self-injury in nonclinical samples: Systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Suicide and LifeDThreatening Behavior, 44(3), 273-303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor P. J., Jomar K., Dhingra K., Forrester R., Shahmalak U, Dickson J. M. (2018). A meta-analysis of the prevalence of different functions of non-suicidal self-injury. Journal of Affective Disorders, 227, 759-769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.