Abstract

Typically, psychotherapy training comprises of didactic approaches and clinical practice under supervision, with students rarely having the opportunity to observe other therapists’ work in real time. Many trades and professions employ apprenticeship to teach new skills. However, it is rarely employed in psychotherapist training. This qualitative study was part of a pilot study that developed and tested the feasibility of an apprenticeship model to be used in psychotherapy training, and investigated how students experienced such training. Ten first-year clinical psychology students joined experienced therapists as observers and/or co-therapists. Each student attended up to 8 therapy sessions with different therapists/patients. The students wrote reflective log entries after each session. In sum, 66 log entries were collected and analyzed with reflective thematic analysis. Five themes were generated, reflecting how the students changed their perspectives from an internal focus to an increasingly external focus: Being informed by emotions, What sort of therapist will I become? Shifting focus from me to the other, The unpredictable nature of therapy, and Growing confidence in therapeutic change. The students gained insights into the dynamic nature of therapy, therapists’ responsiveness, and how internal and external foci of attention inform the therapeutic work. Such tacit knowledge is difficult to convey via didactic methods and might receive limited attention in clinical programs. Apprenticeship training is a promising supplement to traditional training.

Key words: psychotherapy training, therapist development, qualitative research, clinical training

Introduction

Training programs for psychotherapy professions need to convey both theoretical knowledge and practical skills. Programs typically include didactic methods such as coursework and discussions, skills training without patients (pre-practicum), and supervised clinical work with patients (practicum) either at university clinics or external institutions (Callahan & Watkins Jr, 2018a; Orlinsky et al., 2023). The current study presents and examines the utility of a supplementary approach that has received little attention in the literature, namely a model of apprenticeship training in which first-year clinical psychology students with little or no prior clinical training meet experienced therapists and join them in therapist sessions. This qualitative study explores the reflections and insights that students gained after participation in the apprenticeship sessions. Furthermore, the study aims to identify the learning processes that may occur from real-life therapeutic practice early on in students’ clinical training.

Apprenticeship training

One of the most common ways of learning a trade or a set of skills is to accompany a skilled person while on the job (Wolter & Ryan, 2011). Although apprenticeship training is often associated with skilled trades, it is also a major part of many higher education programs including training of health professionals such as nurses and medical doctors (Kale & Barkin, 2008; Taylor & Flaherty, 2020). Other professions that require interpersonal skills, such as teachers and early interventionists, also include apprenticeship as part of their training (Applequist et al., 2010; Bastian & Drake, 2023). Yet, apprenticeship training is rarely utilized in the field of psychotherapy, and hardly reported in literature.

One notable exception is Feinstein et al. (2015) who present an apprenticeship model used for psychotherapy trainees in residence. In their model, the trainees accompany experienced therapists for treatments of a duration of 5-20 sessions. Initially, supervisors lead the sessions, gradually the trainee takes more responsibility, and eventually leads the last sessions independently. The authors suggest that this apprenticeship model is feasible to implement and highly valued by the trainees, thus encouraging the development of apprenticeship models in other psychotherapy training contexts as well.

Whereas the trainees in the model of Feinstein et al. (2015) were advanced trainees in residence, the apprenticeship model in the present study is designed for first-year students with little or no prior knowledge of clinical psychology or psychotherapy. As illustrated below, we argue that apprenticeship can be useful also in the early stages of a clinical psychology education.

The timing of clinical training

In most countries, clinical psychology training programs typically require a university degree at a bachelor’s or master’s level (Norcross et al., 2010; Orlinsky et al., 2023). Likewise, in the Norwegian context of the present study, students in clinical psychology usually start their clinical training after several years of theoretical psychology studies. Thus, trainees are expected to know relevant psychological theories of human behavior, health, and development, before entering clinical training and - ultimately, the helper role in clinical work with actual patients. Indeed, a theoretical foundation and conceptual model of psychological development, health, and maladjustment may be essential to understanding patients’ psychological distress as a therapist.

On the other hand, first-hand experiences with the therapeutic setting could also be pivotal, for example, by witnessing how the therapeutic process unfolds during sessions and experiencing the emotions that clinical work often evokes, serving as context and adding relevance to the student’s theoretical studies. This notion is in line with a systems-contextual approach (Beidas & Kendall, 2010) which argues that therapist training is a process in which contextual factors are highly relevant and should be considered in parallel with theoretical knowledge or skills training. Situated learning, i.e., apprenticeship training, can promote ecologically valid knowledge (Feinstein, 2021). Considering the general opinion that apprenticeship training is useful and necessary for many clinical professions (Feinstein et al., 2015; Kühne et al., 2022), and theoretical notions of therapist training that support the benefits of clinical practice in parallel with theoretical learning (Beidas & Kendall, 2010), it is timely and appropriate to explore this concept in the context of early clinical psychology education. In the present study, we aim to address this topic by investigating the experiences of first-year clinical psychology students, with little or no prior theoretical or clinical experience with psychology or related sciences, after having participated in an apprenticeship training model developed for this purpose.

The novice student’s first meeting with a client

Building on an extensive literature review and empirical studies, Rønnestad and Skovholt (2013) describe the novice psychotherapy student phase as overwhelming. In their first meetings with clients, students strive to keep in mind relevant declarative knowledge, demonstrate therapeutic skills, and manage their own and the patient’s emotional reactions. Qualitative studies of novice students’ experiences support these notions. For example, Hill, Sullivan, et al. (2007) report that counseling psychology trainees who met with their first clients as part of their training were concerned with a range of topics including: their own emotional reactions to the client, critical evaluations of their performance as therapists, and how to use specific skills.

In response to the high stress perceived by novice students, Rønnestad et al. (2019) recommend creating a holding environment (p.219). The term refers to Winnicott (Anderson, 2014), who used it to describe how a therapist supports their patient by creating a space for the patient to feel cared for and safe, thus reducing stress even when experiencing strong emotions. According to the polyvagal theory for understanding the regulation of stress, being able to experience a sufficient degree of «felt sense» of safety and being available and open in contact with others (Porges, 2022), are necessary prerequisites for being able to function as a therapist. Within this theory, neural structures in the social engagement system (Porges, 2009) further lead to autonomous states in the interacting dyad that both send out and receive signals of perceived security – which both inhibit fear responses and promote accessibility and co-regulation (Porges, 2022). Accordingly, apprenticeship training can be one way to allow students to meet clients in a less emotionally demanding context, as the experienced therapist will take the therapeutic responsibility. The student will be able to observe and cope with their emotional reactions, make clinical observations, and familiarize themselves with the therapeutic context, without having to face the full demands of independent therapeutic work.

Professional and personal development in clinical training

During the last 20 years, there has been an increased interest in defining and operationalizing the competencies required to become psychotherapists (Fouad et al., 2022; Hatcher & Lassiter, 2007; McDaniel et al., 2014) and in empirically investigating how these competencies are promoted in clinical training (Hill, Stahl, et al., 2007; Perlman et al., 2023). Pascual-Leone et al. (2013) argue that also personal development is a vital part of psychotherapy training, and mention areas such as emotional sensitivity, self-awareness, and maturity. Although personal development is explicitly recognized in some therapeutic orientations, the topic has received little interest in research. In the study by PascualLeone et al. (2013), graduate students wrote self-reflections after having completed an introductory clinical training course. One of the major themes was that of self-development, such as increased sensitivity, ability to connect with others, and acceptance of one’s own and others’ shortcomings. In another study, counselors in training were asked to write weekly journals during their training, which included lectures, supervision, and clinical work with patients (Fitzpatrick et al., 2010). The findings illustrate how the trainees developed their own professional identity in terms of theoretical orientation, based on a range of influences during their training. Finally, individual interviews of internship students from different training programs revealed central topics in terms of developing a professional identity, integrating theoretical and practical knowledge, and managing the transition from university settings to clinical reality (Mele et al., 2021).

These studies illustrate how clinical training can promote personal development related to the roles of professional therapists. The studies all included different skills-training contexts, either with peers (Pascual-Leone et al., 2013) or with patients (Fitz-patrick et al., 2010; Mele et al., 2021). The study presented here will extend these findings by investigating students’ experiences in an apprenticeship context, where the performance demands of the trainees are reduced.

Purpose of the study

In the current study, students were offered apprenticeship training as an extracurricular activity in their first year of a six-year clinical psychology program. The apprenticeship training represents a new way of providing clinical experience to trainees. The training did not focus on the students’ skills performance, and the students had little or no prior theoretical or clinical experience with psychology or other related sciences (e.g., social work, nursing, etc.). The purpose of the study was to qualitatively explore the students’ experiences and reflections during the apprenticeship practice.

Methods

Study context and participants

In Norway, which is the context of the present study, the clinical psychology programs accept candidates from secondary-level education directly into a 6-year program which includes theoretical, scientific, and clinical training in one program, leading to a master’s level degree as a licensed clinical psychologist. While clinical practice typically takes place in the last three years of the program, clinical topics are to some degree introduced already in the first year, parallel with theoretical psychology studies.

This study is part of a pilot project in which an apprenticeship model for first-year students in clinical psychology was tested for feasibility and learning outcomes (see Brattland et al., 2022, for further information on the main study). The project was a mutual collaboration between the Norwegian University for Science and Technology (NTNU) and the Community Mental Health Center (CMHC) Nidelv DPS, Tiller Department, St. Olavs University Hospital. Twenty students were included in a randomized controlled trial, in which ten students were allocated to apprenticeship training together with clinicians working in the outpatient clinics in the CMHC (experimental condition), whereas the remaining students were given clinical training as usual (control condition).

The 10 participants who received the apprenticeship training are included in the present study. These were six men, and four women, all in the age range 20-30 years, in the first year of the study program. This first year includes introductory psychology courses, mostly lecture-based, and a seminar on professional development and ethics.

Ten weekly sessions were planned for the apprenticeship training during the spring semester of 2020. However, due to practical issues related to the COVID-19 pandemic, the number of weekly sessions was reduced to eight, and the last three sessions took place during the autumn of 2020. In these sessions, the student met with a therapist and joined them for one therapy session with one of the therapist’s regular patients. The student met a new therapist and patient each week, to promote variation and exposure amongst students to different therapeutic styles. The therapists conducted treatment as usual and were not instructed to adhere to any specific treatment approach. In the therapy session, the students could have an active role similar to that of a co-therapist, or they could be more in the background, observing the session. The role of the student varied according to the therapist’s preferences and what was considered appropriate for the specific patient/session. The therapist and the student had a short conversation before the therapy session for preparation and after the session for debriefing and discussion (typically 10 minutes). All the students gave written consent to participate, and the study was approved by the Regional Committee for Medical and Research Ethics (2012/1498).

Data collection

Directly after each therapy session, the student met with the other students and one or two of the researchers who are also clinical psychologists. They were asked to write a log entry about their immediate thoughts about the session, any aspects of the experience that had made a special impact on them, their reactions in the session and afterward, and their reflections in general. Each log entry was approximately one hand-written page, and altogether the ten participants wrote 66 log entries.

Analysis

The analysis was performed in NVivo (Lumivero, 2023). Reflexive thematic analysis methodology was used, which included coding the data material and searching for common themes across the data set (Braun & Clarke, 2006, 2021). The analysis process alternated between individual text analysis and group discussions. In particular, the group discussions increased reflexivity, as they enabled the researchers to critically examine their preconceptions and how they could shape the interpretation of the data.

The analysis procedure was as follows, in line with the recommendations of Braun & Clarke (2006 2021): i) The researchers read through the data material several times individually, to become familiarized with the data. ii) Preliminary codes were drafted, initially keeping an open and exploratory approach to the data. After discussions, the team agreed to focus on the students’ learning experiences concerning therapy and themselves as developing therapists. With this narrower focus on analysis, codes were revisited and adjusted. iii) Initial themes were generated, and coded data were assigned accordingly. iv) Themes were further elaborated in group discussions and adjusted to ensure that the meanings relevant to the research question were captured. v) The data was revisited, ensuring that all information relevant to the research topic was included in a meaningful way, and final themes were determined. vi) A description of each theme was written up, and sample quotes that represented the essence of each theme were selected.

The three researchers involved in the analysis (KHH, TG, NJL) are clinical psychologists and experienced in clinical training of psychology students. KHH has been involved in the planning and implementation of the study, whereas TG and NJL were new to the project at the time of the data analysis. A phenomenological-hermeneutic approach was adopted (Ho et al., 2017), aiming to capture the human experiences as they were conveyed in the reflective log entries, while also acknowledging that the researchers’ previous knowledge and professional background would contribute to their understanding of the data.

All quotes in the results section are followed by two numbers: the first referring to the specific student (1 to 10), the second number referring to the specific session (1 to 8).

Results

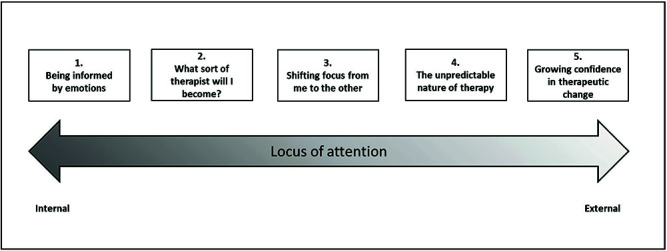

Five overall themes were generated. Three of the themes were related to the student’s personal and emotional experience, “Being informed by emotions”, “What sort of therapist will I become?”, and “Shifting the focus from myself to the other”. Two themes concern the way the students reflected and gained insight regarding the nature of therapy: “The unpredictable nature of therapy” and “Growing confidence in therapeutic change”. In discussing the themes, the researchers’ prior knowledge of relationships between stress, learning, and attention (e.g., Porges, 2022; Clark & Wells, 1995) created the opportunity to arrange the themes in a meaningful way on a continuum according to locus of attention, with the students’ focus on themselves and their own internal processes in one end (theme 1) and an increasing external focus on the therapy process in the other end (theme 5) (Figure 1). This continuum does not represent a fixed timeline; both internal and external loci of attention were prominent throughout the apprenticeship period.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the themes.

Theme 1. Being informed by emotions

This theme encompasses the students’ awareness of their emotional reactions in the therapy session, and how the experience of these emotions provided important information about themselves and the therapeutic setting. The students named a range of emotions they experienced while being in the room with the therapist and the patient, from “motivated”, “excited” and “impressed”, to “nervous” and “sad”. Many of the emotional reactions were related to the patients:

At one point, I felt that my stomach tightened when he talked about a recent event. I could actually have cried if I had allowed myself to. (7-7)

The students’ emotional reactions seemed central to their understanding of therapeutic work; being able to connect with the patients emotionally, experiencing empathy, and the regulation of one’s emotions served as reassurances that they had the necessary capabilities to become a therapist. Experiencing strong emotional reactions for a person they had just met was described as somewhat surprising: “It made an impact on me, how much empathy I felt for the patient.” (6-4) Some students suggested this was possible because they had something in common with the patient, or they found the patient sympathetic, which also raised some concern regarding what to do if you do not like the patient: “I found the patient sympathetic. I think that as a therapist, it will be more difficult to relate to a patient one finds unsympathetic.” (3-5)

Although the students perceived their own emotions as important in a therapeutic context, they also recognized the need for emotion regulation skills; the therapist cannot be overwhelmed by their own emotions, and some students described this combination of experiencing emotions and still remaining well-regulated. They suggested that it is possible, but maybe challenging at times, to find a balance between the two:

I noticed I was touched [by their story], but I tried to keep myself together. But then again, you do want to be perceived as a human being, not as a robot. (7-1)

Similarly, some of the students described situations in which their emotions had created an urge to take action; for example, to say something comforting, or to give the patient a hug. “My heart goes out to [the therapist’s] patient today. I just wanted to be there for them, give them a real hug and tell them that they are good enough” (6-4). Whereas some types of empathetic behaviors are welcome in a therapy setting, others obviously are not. In some situations, it may be less clear whether one can allow one’s emotions to influence one’s behavior:

I really wanted to convey encouragement and hope to the patient, but as the session moved along, I realized that just because you want someone to feel better doesn’t mean they are receptive for that just yet. (1-3)

This theme represents one end of the “locus of attention”-continuum, in which the students focus internally rather than on more external processes related to the therapist, the patient, or the therapeutic process. While an increased focus on oneself could reflect the level of stress experienced by the students, which could also potentially attenuate their ability to learn or to connect with the patient, the theme also encompasses the students’ recognition that awareness of their own emotions are important and serve many functions: Being able to experience these emotions and at the same time being able to regulate them according to the therapeutic context, is perceived as a reassurance of one’s potential for serving as a future therapist.

Theme 2. What sort of therapist will I become?

This theme entails the students’ expectations of their role as therapists in the future, based on their experiences from the therapy sessions. These reflections were often characterized by motivation and optimism:

I feel that this is a profession I am looking forward to – it is so incredibly exciting to gain all this insight into other people’s lives. (4-4)

The students’ reflections on their future role as therapists arose mainly from two sources; first, how the student experienced their own reactions and coping during the therapy sessions, as described in the previous theme, and second, observations of the therapist’s behavior and responses.

Although the students were looking forward to becoming therapists, some also realized how their own personal characteristics could challenge the therapeutic work. For example, one student realized that being able to address a patient’s grief could be difficult:

I discovered very quickly that grief is a very challenging topic for me. I find it difficult to know which questions to ask, and I was afraid of touching into topics the patient was not comfortable with. (8-6)

Other aspects concerned the acquisition of therapeutic skills, as the students reflected on their personal strengths and weaknesses related to being able to allow for silent pauses in the conversation, to communicate clearly or how to address emotions: To endure silence, that is definitely something I find a bit challenging. (7-2)

It was evident that the therapist served as a role model in terms of how therapeutic work can be performed, and the students were eager to see the therapists’ behavior as a guide for their own development as therapists. Some of these observations concerned how the therapist created a safe, relaxed and supporting atmosphere in the therapy session. One student noted that even when using standardized assessment interviews which might seem unnatural and formal, it is possible to create a natural and relaxed conversation:

I was thinking that I need to make sure the questions are asked in a natural and casual way and that it is good to prepare the patient when there are longer questions coming up. And a sense of humor about the wording can ease the contact with the patient. I learned a lot from how she did [the interview]. I have been wondering how to do it in a natural way, without sounding robot-like. (5-1)

Theme 3. Shifting focus from me to the other

As described in theme 1, the students experienced a range of emotions during the therapy sessions and had many reflections about their own emotions. Gradually however, a change was noticed by some students as they became less self-conscious and were able to focus more on the patient and the therapy process. On the continuum depicted in Figure 1, theme 3 represents a change in locus of attention from internal to external.

Some students were unsure of how to behave in the therapy session and became accordingly self-aware:

I notice that I am still a bit uncomfortable with being in the therapy session, and I become uncertain about little things like my eye contact being too direct or too avoidant, do I sit too still or do I tilt my feet up and down too much? [I feel] extra self-conscious, but I mostly manage to pay attention to the conversation. (4-4)

Upon being invited to participate more actively in the therapy session, for example, to ask questions to the patient or reflect on topics that were discussed by the therapist and patient, the fear of “saying the wrong things” was quite common. Thus, active participation required quite a bit of courage, but also gradually developed into confidence. The feedback from the patient or from the therapist was important for the students’ appraisal of themselves:

I find it challenging to know what is «good» or «stupid» to say, and so it was really good to talk to the therapist after the session. Today I got positive feedback, and it made me feel calm and assured after the session. (1-1)

Over time and as the students had more experience with the therapy situation, they reported feeling less anxious and self-conscious. This allowed them to direct their attention towards the patient’s experiences instead of themselves: You might say that self-consciousness takes up less space in the session (…) it makes it easier to focus on the patients’ story. (1-6)

Still, although the growing capacity to attend to the therapy process was perceived as a positive development, the awareness of one’s own emotions – as described in theme 1 – was also acknowledged. One student reflected upon the balance or potential conflict between self- and other- awareness:

During the session, I was also thinking about compassion. As a therapist, the self-awareness – constantly monitoring how you feel – could restrict one’s ability to experience true compassion. Maybe it all gets too analytic, and makes you feel un-genuine. How does one avoid that? (9-5)

Theme 4. The unpredictable nature of therapy

The process of observing and learning the characteristics of therapy included observations of the dynamic nature of the therapy process. Sessions do not always proceed according to the plan; each patient is different, and the therapist does not always know what to do. The conversations between the student and therapist after the therapy sessions were important for students to gain insight into the therapist’s reflections about processes that did not go as planned, or interventions they were unsure of:

The hopelessness was very present. Then [the patient] turns to the therapist and asks, what can I do? I realized this was a very difficult situation for the therapist, to try to convey hope in a situation that seemed quite hopeless. Because it was a difficult question, he did not reply right away – he told me [later] that he needed some more time to think. (9-4)

Dilemmas experienced by the therapist often became apparent in the conversations after therapy sessions, and these conversations contributed to an acknowledgement of the therapist as a “human being”, and that even an experienced therapist will sometimes still be insecure or in need of reflecting and evaluating.

Some elements that students considered as particularly challenging included the assessment of suicide risk, how to understand clinical phenomena such as comorbidity, and deciding when to steer the conversation rather than letting the patient talk freely. It was also acknowledged that the process of therapeutic change does not always follow the textbook; for example, the therapist can’t decide how the patient receives and understands the therapist’s interventions:

It made me think that there is a long way between [the patient] hearing a message and internalizing its content. Really understanding these apparently simple messages takes time and requires some work to become a natural part of your thinking. (10-2)

Along with the appreciation of the complexity of therapy situations, some students described a change during the apprenticeship period. While they were initially concerned with the “correct” or “incorrect” responses, there was a shift toward an understanding of dynamics and flexibility: I did not view the therapy room as a sacred room where mistakes must not be made. (3-1)

Part of this development also involved a new understanding of the therapeutic relationship for one of the students:

Maybe exactly this, to establish a connection and show empathy, are among the most important things. Therapy techniques and theories are important of course, but not worth much without [the connection and empathy]. Of course, this isn’t completely new to me, but especially after the last two sessions something has sort of opened up for me. (7-8)

Theme 5. Growing confidence in therapeutic change

This theme encompasses the students’ understandings and observations of how therapeutic work may result in positive outcomes for the patient. Some students described situations that reflected specific change: for example, a patient at the end of a therapy talking about the change they had experienced over time. Others noticed moments within the session that made a difference for the patient, as the student perceived it.

Today, I got to sit in on a session with a patient who was close to finishing the treatment. For me, it was very positive to meet a patient who had experienced huge improvement and had begun to feel joy again after a period of severe depression. It is very motivating. (1-4)

One of the students was initially skeptical towards the effectiveness of therapy, suggesting that therapy is just a conversation, not different from how you talk with a friend. Yet the student was also open to the possibility that therapy indeed had an effect, although the student had not yet witnessed it. Over time, the student seemed more open to the idea that therapy can make a difference for the patient.

I don’t really see how this one conversation about problems would have any effect, but I guess people might have strategies for problem-solving that are different from my own. (3-1)

So, they were talking about the positive things happening in her life right now, and I perceived it more like a normal conversation than treatment. (3-3)

It was exciting to see this session because I had the feeling that change could happen here, in a good way. With some tools the patient could have a better quality of life. (3-5)

As illustrated by the last citation, quality of life was one example of how therapy outcomes can be operationalized. Other examples included behavioral change, mood change, and hope:

One thing I found interesting this session was how the atmosphere in the room changed. (…) [the patient] talked about being depressed and “everything had failed”. At the end of the session the mood was lighter, it seemed like the therapist had managed to convey a sense of hope to the patient. (7-4)

Moreover, the understanding of therapeutic work seemed to expand from the aim of treating a disorder, to also include therapeutic aims such as addressing milder symptoms in order to prevent them from developing into a more serious condition. Also, the understanding that the aim of therapy will change according to person and situation, was addressed:

She [the therapist] told me that their task was to stabilize. When someone experiences a crisis, you don’t explore their emotional life, you focus on suicide prevention. (3-6)

In sum, the students provided examples of a range of different ways of understanding the outcomes of therapy, including behavioral and emotional change, cognitive changes like optimism or self-compassion, quality of life, or the prevention of adverse consequences. Descriptions of moments where the students felt they were witnessing some of these changes as a result of therapeutic work, were described as significant and inspiring.

Discussion

This study qualitatively explored first-year clinical psychology students’ experiences and reflections during their participation in apprenticeship training. Overall, five major themes were generated that could be arranged in a meaningful way on a continuum from internal- to external locus of attention. On a personal and emotional level, students experienced first-hand that their own emotions could serve as important sources of information yet needed to be regulated in the therapeutic setting (theme “Being informed by emotions”), gained new and often optimistic ideas about their future work as therapists (theme “What sort of therapist will I become”), and discovered that their capacity to attend to the patient and therapy process rather than themselves grew with experience (theme “Shifting the focus from myself to the other”). Students also described increasing insight into the nature of therapy, both its dynamics and flexibility (theme “The unpredictable nature of therapy”), and its potential to create change in patients (theme “ Growing confidence in therapeutic change”).

Taken together, we believe the results from this pilot study indicate that apprenticeship training may add to more traditional learning methods in terms of learning outcomes and personal development. Below, we further expand on our discussion according to four broader themes; (a) the need to create a safe context for clinical learning; (b) a dynamic locus of attention; (c) the potential benefits of early exposure to clinical work; and (d) the role of personal development and theories of change.

A safe context for learning

In contrast to typical clinical training programs in which students first meet patients as they enter the role of trainee therapists, the apprentice model allows students to meet patients with much less pressure than has otherwise been noted in the literature (Hill, Sullivan, et al., 2007; Rønnestad & Skovholt, 2013). Students are provided with a safe learning context, which invites them to observe from a safe “distance” without being burdened by demands, stress, and anxieties to perform themselves, while simultaneously being part of the therapeutic context. The themes “being informed by emotions” and “the unpredictable nature of therapy” illustrate the observations that students made of themselves, the patient, and the therapist. Being able to be available and receptive both inwardly to their reactions while at the same time taking in the patient’s situation, indicates that the apprenticeship model provided a sufficient degree of security so that the students’ social engagement system (Porges, 2009) could be active. It is possible that the experienced therapist created what Rønnestad et al. (2019) call a “holding environment (p. 219)”, by taking responsibility for the therapeutic process so that the students could allow themselves to just observe, experience, and reflect.

A flexible locus of attention

Our analysis revealed that attentional focus was an important factor in the students’ experiences. Their descriptions of observations and reactions were guided by how they sometimes focused on themselves, and at other times could direct their attention towards the therapist or the patient, as described in the theme “shifting focus from me to the other”. The students were thus provided an opportunity to decrease their self-focus and consequently, have increased access to their own executive-cognitive attentional resources, optimizing their possibilities for learning. This aligns with established cognitive treatment approaches that instruct patients to shift their focus of attention to reduce stress and increase coping (e.g., Clark & Wells, 1995; Wells, 1997). The apprenticeship model seems to provide a similar opportunity for accelerated possibilities for new learning for novice therapists.

At the same time, whereas a diminished self-focused attention can facilitate learning, the internal focus of attention is also a source of learning, as described in the theme “being informed by emotions” and “what sort of therapist will I become?”. The ability to allow oneself to be moved by the patient’s story is necessary to experience empathy, which is acknowledged as an important common factor in all psychotherapy (Norcross et al., 2010). Being able to experience this and coping well with it seems to have provided some self-confidence for the trainees.

Early exposure to clinical work

In most psychotherapy training programs, admission requires a university degree in a relevant discipline (Orlinsky et al., 2023), thus candidates typically have some theoretical knowledge before entering clinical practice. In contrast, the apprenticeship model utilized in this study provides exposure to therapy settings and clinical work during the first year of university studies, that is, parallel with the introduction of courses in psychology theories and psychopathology. This model aligns with a systems-contextual approach (Beidas & Kendall, 2010). As was apparent in the theme “the unpredictable nature of therapy”, the students observed how therapy can take unexpected turns. The patient may not respond according to the book, and the therapist can be unsure of what to do next. These observations provide a realistic insight into the nature of therapy, thus conveying ecologically valid knowledge (Feinstein, 2021). Such knowledge likely provides a valuable perspective when approaching scientific and clinical literature throughout their study program.

The Norwegian clinical psychology programs use high school grades as admission criteria. Predicting future therapist competence from academic skills is, however, an uncertain endeavor (Callahan & Watkins Jr, 2018b), and the students themselves have typically little or no previous first-hand experience with clinical work. Thus, students are oftentimes worried and anxious about their own capability to engage in clinical work (e.g., Hansen et al., 2010; Hill, Sullivan, et al., 2007; Rønnestad & Skovholt, 2013). As demonstrated in the theme, “what sort of therapist will I become?”, students did reflect on this topic during the apprenticeship training. The exposure to therapy situations, the observations of the therapist, and their emotional reactions seemed to contribute to the students’ expectations regarding the profession and themselves as therapists. This included increased motivation and assurance of their choice of study, reflected in the theme “Growing confidence in therapeutic change”. This may influence how the students approach their theoretical and clinical learning during the remaining five years of the study program.

Personal development and theories of therapy

Previous qualitative studies have demonstrated that clinical trainees experience personal development and acquire important insights about the field of psychotherapy during skills training (Fitzpatrick et al., 2010; Mele et al., 2021; Pascual-Leone et al., 2013). Our results supplement these studies and illustrate how observing an experienced therapist can expand the students’ understanding of clinical work and therapeutic processes. For example, the theme “Growing confidence in therapeutic change” describes perspectives of therapy which might reflect an increased insight regarding what therapy is, and what to expect. The notion that therapeutic change is not always associated simply with symptom relief, but also with increases in optimism, self-awareness, knowledge, quality of life, and progress towards personal values and goals, could arguably be an important perspective for the students in their studies of therapy literature and in their future practice.

As presented in the theme “the unpredictable nature of therapy”, the students observe that even an experienced therapist is not always confident in his or her work. Possibly, such observations could ease some of the pressure novice therapists experience, as described by others (Hill, Sullivan, et al., 2007; Rønnestad & Skovholt, 2013). Moreover, associations between therapists’ self-doubt and patient outcomes have been reported (Nissen-Lie et al., 2013), suggesting that students’ exposure to role models who display this characteristic can be important. The notion of self-doubt, along with other realizations described in our results such as the importance of interpersonal connection and empathy, and that there is not always a “right” or “wrong”, are similar to the findings described by Pascual-Leone et al. (2013) which are likely to reflect personal development and a maturation of the understanding of therapy.

Personal characteristics such as coping mechanisms and attitudes towards therapeutic processes are important factors in therapeutic work, especially when facing challenging situations (Heinonen & Nissen-Lie, 2020). Apprenticeship training is interactive in nature, in the sense that the students can interact with the patient and with the therapist according to what the situation allows for. The students also gained some insight into their own reactions and personal characteristics which might affect their therapeutic work, such as difficulties in coping with specific emotions or groups of patients. Awareness of such areas of one’s personal functioning could facilitate the development of targeted interpersonal skills as part of the clinical training.

Strengths and limitations

The data used in this study were log entries written by the students after each therapy session. This approach allowed a short time between the experience and the students’ reporting, thus reducing any recollection bias that could have been problematic in other approaches, for example, interviews with the students at the end of their apprenticeship period. The format of writing down their thoughts, as opposed to talking with an interviewer, was also chosen to provide a sense of privacy for the students as if they were writing a diary for themselves. Our aim with these design choices was to increase the level of detail, and thus richness of the data material, as we aimed to collect data on the students’ actual thoughts in the sessions, as opposed to their evaluations of the apprenticeship model as such. However, a limitation of this approach is the lack of opportunities to prompt for topics or follow up on statements to go into more detail, as one could do in an interview. Future studies might be able to provide even richer data by conducting qualitative interviews with each trainee.

The data collection for this study was conducted in 2020. Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, lockdown periods caused practical challenges and the pauses between some of the therapy sessions were quite long. However, we still feel confident that the qualitative findings reported in the current study are valid and provide important knowledge of students learning processes.

As the present study aimed to explore the students’ personal experiences and learning outcomes, it is not a study of the effectiveness of the apprenticeship model and should not be interpreted as such. However, the larger ongoing randomized controlled trial (Brattland et al., 2022) will provide further possibilities to assess the effects of the apprenticeship model.

Conclusions

Apprenticeship training is a promising supplement to traditional psychotherapy training and provides a safe learning environment in which students gain tacit knowledge on therapy and on themselves as therapists. It is possible to introduce this type of training even at the very beginning of clinical studies, to provide a useful background for later theoretical and clinical learning.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the therapists at Nidelv DPS and their patients, for accepting students into their therapy sessions. We also thank Øyvind Watne, Per Knutsen, Jon Morten Landrø, and Anne Elisabeth Skjervold for invaluable advice in the planning of the study. Finally, we thank the students for participating. Preliminary results from the study were presented at the 9th EUSPR Chapter meeting of Society for Psychotherapy Research in Rome, in 2022, and the SPR 54th Annual Meeting of Society for Psychotherapy Research in Dublin, in 2023.

Funding Statement

Funding: the study was funded by a grant from the Liaison Committee between Central Norway RHA and NTNU.

Data availability

Due to consent restrictions from participants, data are not available to researchers other than the authors of this manuscript. The list of codes that was generated in the qualitative analysis is available from the first author.

References

- Anderson J. W. (2014). How D. W. Winnicott conducted psychoanalysis. Psychoanalytic Psychology, 31(3), 375-395. doi: 10.1037/a0035374 [Google Scholar]

- Applequist K., McLellan M., McGrath E. (2010). The Apprenticeship Model: Assessing Competencies of Early Intervention Practitioners. Infants & Young Children, 23, 23–33. doi: 10.1097/IYC.0b013e3181c975d5 [Google Scholar]

- Bastian K. C., Drake T. A. (2023). School Leader Apprenticeships: Assessing the Characteristics of Interns, Internship Schools, and Mentor Principals. Educational Administration Quarterly, 59(5), 1002-1037. doi: 10.1177/0013161x 231196502 [Google Scholar]

- Beidas R. S., Kendall P. C. (2010). Training Therapists in Evidence-Based Practice: A Critical Review of Studies From a Systems-Contextual Perspective. Clin Psychol (New York), 17(1), 1-30. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-2850.2009.01187.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brattland H., Holgersen K. H., Vogel P. A., Anderson T., Ryum T. (2022). An apprenticeship model in the training of psychotherapy students. Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial and qualitative investigation. PLoS One, 17(8), e0272164. 10.1371/journal.pone.0272164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101. doi: 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [Google Scholar]

- Braun V., Clarke V. (2021). Thematic analysis. A practical guide. Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Callahan J. L., Watkins Jr C. E. (2018a). Evidence-based training: The time has come. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 12(4), 211-218. doi: 10.1037/tep0000204 [Google Scholar]

- Callahan J. L., Watkins Jr C. E. (2018b). The science of training I: Admissions, curriculum, and research training. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 12(4), 219-230. doi: 10.1037/tep0000205 [Google Scholar]

- Clark D. M., Wells A. (1995). A cognitive model of social phobia. In Social phobia: Diagnosis, assessment, and treatment. (pp. 69-93). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein R. E. (2021). Descriptions and Reflections on the Cognitive Apprenticeship Model of Psychotherapy Training & Supervision. Journal of Contemporary Psychotherapy, 51(2), 155-164. doi: 10.1007/s10879-020-09480-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feinstein R. E., Huhn R., Yager J. (2015). Apprenticeship Model of Psychotherapy Training and Supervision: Utilizing Six Tools of Experiential Learning. Academic Psychiatry, 39(5), 585-589. doi: 10.1007/s40596-015-0280-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fitzpatrick M. R., Kovalak A. L., Weaver A. (2010). How trainees develop an initial theory of practice: A process model of tentative identifications. Counselling and Psychotherapy Research, 10(2), 93-102. doi: 10.1080/1473314 1003773790 [Google Scholar]

- Fouad N. A., Hatcher R. L., McCutcheon S. (2022). Introduction to the Special Issue on Competency in Training and Education. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 16(2), 109-111. doi: 10.1037/tep0000408 [Google Scholar]

- Hansen T. I., Svendsen B., Hagen R. (2010). Studentterapeuters bekymringer og opplevelse av profesjonsstudiet. [Worry related to clinical training of Norwegian psychology students]. Journal of the Norwegian Psychological Association, 47(6), 505-510. [Google Scholar]

- Hatcher R. L., Lassiter K. D. (2007). Initial training in professional psychology: The practicum competencies outline. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 1(1), 49-63. doi: 10.1037/1931-3918.1.1.49 [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen E., Nissen-Lie H. A. (2020). The professional and personal characteristics of effective psychotherapists: a systematic review. Psychotherapy Research, 30(4), 417-432. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2019.1620366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C. E., Stahl J., Roffman M. (2007). Training novice psychotherapists: Helping skills and beyond. Psychotherapy (Chic), 44(4), 364-370. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.44.4.364 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill C. E., Sullivan C., Knox S., Schlosser L. Z. (2007). Becoming psychotherapists: Experiences of novice trainees in a beginning graduate class. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 44(4), 434-449. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.44.4.434 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho K. H. M., Chiang V. C. L., Leung D. (2017). Hermeneutic phenomenological analysis: the ‘possibility’ beyond ‘actuality’ in thematic analysis. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 73(7), 1757-1766. doi: doi: 10.1111/jan.13255 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kale S. A., Barkin R. L. (2008). Proposal for a Medical Master Class System of Medical Education for Common Complex Medical Entities. American Journal of Therapeutics, 15(1), 92-96. doi: 10.1097/MJT.0b013e31815fa680 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kühne F., Heinze P. E., Maaß U., Weck F. (2022). Modeling in psychotherapy training: A randomized controlled proof-of-concept trial. J Consult Clin Psychol, 90(12), 950-956. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000780 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McDaniel S. H., Grus C. L., Cubic B. A., Hunter C. L., Kearney L. K., Schuman C. C., Karel M. J., Kessler R. S., Larkin K. T., McCutcheon S., Miller B. F., Nash J., Qualls S. H., Connolly K. S., Stancin T., Stanton A. L., Sturm L. A., Johnson S. B. (2014). Competencies for Psychology Practice in Primary Care. American Psychologist, 69(4), 409-429. doi: 10.1037/a0036072 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mele E., Espanol A., Carvalho B., Marsico G. (2021). Beyond technical learning: Internship as a liminal zone on the way to become a psychologist25. Learning Culture and Social Interaction, 28. doi: 10.1016/j.lcsi.2020.100487 [Google Scholar]

- Nissen-Lie H. A., Monsen J. T., Ulleberg P., Rønnestad M. H. (2013). Psychotherapists’ self-reports of their interpersonal functioning and difficulties in practice as predictors of patient outcome. Psychother Res, 23(1), 86-104. doi: 10.1080/ 10503307.2012.735775 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Norcross J., Ellis J., Sayette M. (2010). Getting In and Getting Money: A Comparative Analysis of Admission Standards, Acceptance Rates, and Financial Assistance Across the Research-Practice Continuum in Clinical Psychology Programs. Training and Education in Professional Psychology, 4, 99-104. doi: 10.1037/a0014880 [Google Scholar]

- Orlinsky D. E., Messina I., Hartmann A., Willutzki U., Heinonen E., Rønnestad M. H., Löffler-Stastka H., Schröder T. (2023). Ninety psychotherapy training programmes across the globe: Variations and commonalities in an international context. Counselling & Psychotherapy Research, No Pagination Specified-No Pagination Specified. doi: 10.1002/capr.12690 [Google Scholar]

- Pascual-Leone A., Rodriguez-Rubio B., Metler S. (2013). What else are psychotherapy trainees learning? A qualitative model of students’ personal experiences based on two populations. Psychotherapy Research, 23(5), 578-591. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2013.807379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perlman M. R., Anderson T., Finkelstein J. D., Foley V. K., Mimnaugh S., Gooch C. V., David K. C, Martin S. J., Safran J. D. (2023). Facilitative interpersonal relationship training enhances novices’ therapeutic skills. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 36(1), 25-40. doi: 10.1080/09515070. 2022.2049703 [Google Scholar]

- Porges S. W. (2009). The polyvagal theory: new insights into adaptive reactions of the autonomic nervous system. Cleve Clin J Med, 76 Suppl 2(Suppl 2), S86-90. doi: 10.3949/ ccjm.76.s2.17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges S. W. (2022). Polyvagal Theory: A Science of Safety [Review]. Frontiers in Integrative Neuroscience, 16. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2022.871227 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rønnestad M. H., Orlinsky D. E., Schroder T A., Skovholt T M., Willutzki U. (2019). The professional development of counsellors and psychotherapists: Implications of empirical studies for supervision, training and practice. Counselling & Psychotherapy Research, 19(3), 214-230. doi: 10.1002/capr 12198 [Google Scholar]

- Rønnestad M. H., Skovholt T M. (2013). The developing practitioner: Growth and stagnation of therapists and counselors. Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor M., Flaherty C. (2020). Nursing associate apprenticeship - a descriptive case study narrative of impact, innovation and quality improvement. Higher Education Skills and Work-Based Learning, 10(5), 751-766. doi: 10.1108/heswbl-05-2020-0105 [Google Scholar]

- Wells A. (1997). Cognitive therapy of anxiety disorders: A practice manual and conceptual guide. John Wiley & Sons Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Wolter S. C, Ryan P. (2011). Chapter 11 - Apprenticeship. In Hanushek E. A., Machin S., Woessmann L. (Eds.), Handbook of the Economics of Education (Vol. 3, pp. 521-576). Elsevier. doi: doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53429-3.00011-9 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Due to consent restrictions from participants, data are not available to researchers other than the authors of this manuscript. The list of codes that was generated in the qualitative analysis is available from the first author.