Abstract

Research into defensive functioning in psychotherapy has thus far focused on patients’ defense use. However, also the defensive functioning of therapists might be significant because of its potential in promoting changes in the patient’s overall defensive functioning by sharing their higher-level understanding of a given situation and letting the patient have the opportunity to learn how to cope more successfully. This exploratory case study is the first to examine therapist’s defense mechanisms and their relationship to changes in the patient’s defensive functioning evaluated at different times throughout psychoanalytic treatment. We assessed the use of defense mechanisms with the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales in 20 sessions collected at three phases (early, middle and late) of the psychoanalytic treatment. For each session, we identified therapist’s and patient’s defenses, defense levels and overall defensive functioning, with particular attention to the sequence of consecutively activated defenses within the therapeutic dyad. Results showed that the patient’s defensive functioning tended to gradually improve over the course of the treatment, with a slight decrease at the end. Therapists’ overall defensive functioning remained stable throughout the treatment with values in the range of high-neurotic and mature defenses. Assessment of the dyadic interaction between therapist and patient’s use of defenses showed that within-session, the patient tended to use the same individual defenses that the therapist used, which was especially pronounced in the initial phases of the treatment. Towards the end of the treatment, once there was a stable shared knowledge, the patient started to explore using new, higher-level defenses on her own, independent from what defenses the therapist used. Our findings emphasized the analyst’s role in encouraging the development of more effective ways of coping in the patient, confirming previous theoretical and empirical research regarding the improvement of patient’s defensive functioning in psychotherapy. The alterations in these coping strategies, also called high-adaptive defenses, as part of the therapist-patient interaction demonstrate the importance of studying defenses as an excellent process-based outcome measure. The measurement of the degree to which the analyst models and illustrates these superior coping methods to the patient is a prime vehicle for supporting internalization of these skills by the patient.

Key words: defense mechanisms, DMRS, psychoanalytic treatment, coping, process-outcome research

Introduction

Psychological defense mechanisms are conceptualized as unconscious operations that protect individuals against unconscious or unacceptable feelings, desires, thoughts, or external stressors (American Psychiatric Association, 1994; Vaillant, 1992). Research on defense mechanisms has extensively studied the impact of individual’s overall defensive functioning on mental health (Békés et al., 2023a; Di Giuseppe et al., 2021; 2022; Fiorentino et al., 2024; Martino et al., 2023), highlighting the strong relationship between implicit emotional regulation (i.e. defense mechanisms) and various aspects of healthy and pathological mental functioning (Carone et al., 2023; Di Giuseppe et al., 2022; Galli et al., 2019; Gross, 2015; Tasca et al., 2023). Psychotherapy research (e.g., Gelo & Manzo, 2015; Gelo et al., 2020) has shown that changes in defensive functioning are associated with variations in symptoms, personality functioning, mentalization, therapeutic alliance, and quality of life (Békés et al., 2021b; 2023b; Conversano et al., 2023; Tanzilli et al., 2022). While patients’ defenses have been well-explored (e.g., Lingiardi et al., 1999; Perry et al., 2009; Perry & Bond, 2017; Vaillant 1994), little is known about therapists’ defenses/coping styles and how they may impact the patients’ learning new and more adaptive ways of coping with their own impulses, feelings, and wishes regarding the external world. In the present study, we analyzed a psychoanalytic treatment from the dataset of 27 recorded psychoanalytic treatments made available for research purposes by the Psychoanalytic Research Consortium with the aim of exploring the relationship between therapist’s defenses and patient’s defenses and the pattern of change during the treatment.

Psychoanalytic literature has emphasized the gradual movement from less mature to more mature defensive functioning in therapy (Vaillant, 1992; Rice & Hoffman, 2014). Phebe Cramer’s work has shown that defense mechanisms change throughout life, going from a greater use of immature defenses, such as denial and projection, to a greater use of mature defenses, such as individuation (Cramer, 2015). Although very little is known empirically about the mechanisms of change in psychoanalytic treatments (Aafjes-van Doorn, Horne, & Barber et al., 2024), the use of interpretations and the therapeutic relationship are generally highlighted as important (Cooper, 1987; Gabbard, 2004; Yılmaz et al., 2024). As Gill suggested regarding the role of transference interpretation in changing the patient’s functioning, by addressing patient’s conflicts and defenses, as well as patient’s reactions to the analyst or analytic situation, the therapist helps the patient in work with their conflictual emotional, relational, and cognitive patterns, thus fostering improvement in various aspects of personality functioning, including defense mechanisms (Gill, 1982). More recently, attention has also been paid to important implicit processes over the course of treatment, including that of implicit relational knowing (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., 2024; Bekes & Hoffman 2020; Zilcha-Mano & Fischer, 2022). To recall LyonsRuth et al. definition (1998): the implicit relational knowing of patient and therapist intersect to create an intersubjective field that includes reasonably accurate sensings of each person’s ways of being with others, sensings we call the real relationship (Lyons-Ruth et al., 1998).

Previous research has described change in a patient’s defenses over the course of psychoanalytic and psychodynamic treatments (Babl et al., 2019; Kramer et al., 2010; Olson et al., 2011; Perry & Bond, 2012). Since Freud’s first conceptualization of defense mechanisms (1894), and in particular from the ‘60s onwards, a number of scholars have been involved in developing various theoretical and empirical models to evaluate the use of defenses. Most of them have defined defenses as unconscious maladaptive ways of handling conflicts that, at their lower levels (i.e. denial, projection etc.), involve some distortions in reality testing and thus contribute to psychopathology. At higher levels, there are more adaptive ways of coping with life, both with internal conflicts and with problems in living (Lazarus & Folkman, 1991; Silverman & Aafjes-van Doorn, 2023). Conceptualizing defenses as automatic, negative, and pathological whereas healthier ways of coping are aware, positive, and adaptive has been supplanted by Perry’s hierarchical organization of defenses known as the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales (DMRS; Perry, 1990), which is the unique empirical-based method that organizes the entire hierarchy of defense and coping methods into seven levels of increasing adaptiveness and awareness (Di Giuseppe et al., 2021; Di Giuseppe & Perry, 2021). Perry et al. brought together various ways of dealing with conflicts, under the rubric of different levels of defenses, but we believe it is clearer to talk about defenses and coping styles, in referring to Perry’s contributions. The DMRS is nowadays considered the gold-standard theoretical and empirical approach for assessing defenses/coping methods (Di Giuseppe, M., & Lingiardi, 2023). This has inspired the recent development of other DMRS-based measures (Békés et al., 2021a; Di Giuseppe, 2024; Prout et al., 2022). The DMRS analyzes defenses at a microan-alytical level, within the transcripts of clinical interviews and psychotherapy sessions, tracking the individual’s use of defense/coping mechanisms segment by segment, thus offering the possibility of dynamically observing how different defenses unfold during the session and in the various moments of the treatment (Perry, 2014). Moreover, it provides a quantitative index of overall defensive maturity, the so-called Overall Defensive Functioning (ODF), that can be used as an outcome measure in psychotherapy research (Carlucci et al., 2022; Conversano et al., 2023; de Roten et al., 2021; Drapeau et al., 2003).

Providing psychotherapy is known to be often stressful (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., 2022; Briggs & Munley, 2008) eliciting a range of emotional responses also within the therapist (Hayes et al., 2011), and psychotherapy sessions are thus likely to trigger also the therapists’ defenses. To our knowledge, only one other study examined defenses among therapists (Aafjesvan Doorn et al., 2021). This study reported on therapists’ self-reported defenses at the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, using two different self-report measures. On average, therapists reported higher levels of mature defenses and lower levels of neurotic and immature defenses than reported by community and patient samples, reflecting healthy and superior-level functioning (Perry, 2014). Only a small subsample of therapists reported a low overall level of defenses, usually associated with personality disorders or acute depression, related to vicarious trauma (Aafjes-van Doorn et al., 2021). Other studies have highlighted the importance of considering healthcare professionals’ defenses and their impact on perceived stress and burnout (Di Trani et al., 2022; Kocijan Lovko et al., 2007; Pompili et al., 2006). However, these studies were methodologically limited due to cross-sectional designs and the use of self-report measures. Assessing defenses at one time-point only does not clarify if therapists’ use of defenses reflects a character trait or change over time in response to a patient. Moreover, the assessment of defenses using self-reported measures reflects only the conscious correlates of defensive functioning (Perry & Ianni, 1998) and not the implicit relational process. Finally, and maybe most importantly, none of these studies investigated patterns of interactions between therapist and patient defense use.

The present study aimed to address these limitations by examining the therapist’s use of defenses and the patient’s use of defenses within one systematic case study of psychoanalytic treatment (Iwakabe & Gazzola, 2009). We believe that to study the way the analyst approaches the patient’s difficulties by trying to understand them in context (i.e. interpretation leading to insight, that is understanding which is less distorted than the previous approach) is to study a process of teaching and learning. The analyst shares their higher-level understanding of a given situation the patient finds him/herself in and the patient has the opportunity to learn about him/herself and then to cope more successfully. From this perspective, assessing defense mechanisms by both participants in the treatment, from the most immature and undesirable to the most mature and adaptive ones (also called coping strategies), is an excellent measure of both process and outcome (Gelo et al., 2015; Gennaro et al., 2019).

Specifically, this exploratory case study aims to: i) identify the therapist defense use in-session and over the course of treatment; ii) assess the patient defense use in-session and over the course of treatment; iii) qualitatively observe therapist and patient defenses within the same sessions and explore the defense patterns in early and late phase sessions of treatment.

In line with available literature, we expected to observe higher (that is healthier) levels of defensive functioning in the therapist than in the patient at any stage of the treatment. We expected that while patients’ defensive functioning would improve over treatment, therapist’s defense use would remain relatively stable over time, as a result of their role in the treatment leading to their having a lower emotional involvement in the material as well as likely having a more highly structured personality organization. We also expected to see specific interactions between therapist and patient defense use at different stages of the psychoanalytic treatment, as the effect of patient’s implicit learning of therapist’s defensive functioning. We also expected to see specific interactions between therapist and patient defense use at different stages of the psychoanalytic treatment, as the effect of patient’s implicit learning of therapist’s defensive functioning. In particular, we expected that in the early stage of the treatment, the patient would try to use similar defense mechanisms used by the therapist, but with poor persistence and evident predominance of the patient’s usual immature defense mechanisms. In the middle stage of the psychoanalytic treatment, the imitation of therapist’s defense mechanisms would have been more efficient with an evident use of defenses higher in the hierarchy by the patient. Towards the end of the psychoanalytic treatment, we expected that the patient would show a more flexible and adaptive use of defense mechanisms, that would be used independently from the therapist’s use of defenses.

Methods

The case of Annie

The single case reported on in this study is a psychoanalytic treatment carried out from 1982 to 1985 in the United States, belonging to the collection of recorded psychoanalytic treatments made available for research purposes by the Psychoanalytic Research Consortium (for more information visit https://psychoanalyticresearch.org/case-studies/). Eventually we would like to be able to do a similar evaluation of the all the cases, and this serves as an initial foray to see if preliminary results are promising. The treatment took 324 sessions and lasted approximately three and a half years, with sessions taking place four times weekly per week until the 250th session, after which the patient reduced the frequency to twice weekly until termination. Of the full treatment, 20 recorded sessions were transcribed, distributed as follows: sessions 5 to 8 (T1); session 30 to 33 (T2); session 144 to 147 (T3); session 269 to 272 (T4); and sessions 309 to 312 (T5). These groups of four consecutive sessions represented five different times of the treatment, the first eight sessions represent the early phase in the treatment, the last eight sessions represent the late phase of treatment.

The patient was a woman in her early thirties when she began her psychoanalytic treatment. She sought treatment for agoraphobia and related psychophysiological reactions, such as nausea, vomiting and diarrhea, which affected her daily activities and social life. She was married with two children, and was a housewife, and had no intimate relationships outside of her family, including her parents, in-laws and her husband. She articulated conflicts with many members of her immediate family. She was unsatisfied with the relationship she had with her husband and perceived him as blaming and devaluing. She blamed herself for inadequacies as a wife, mother, and a daughter. During the first week of psychoanalytic treatment, she agreed to attend four sessions a week on the couch. At the end of the first year, the patient asked to reduce the frequency to two face-to-face sessions per week, which continued at that frequency for another nearly two years more. At the very end of the psychoanalytic treatment (T5), the patient reported that she re-experienced mild symptoms of agoraphobia and conversion which had disappeared during the therapy. However, she appeared to be much more autonomous and assertive and found a job that rewarded her greatly and in which she invested a lot of psychological resources. Although she still tended to feel anxious, guilty and inadequate at times, her self-awareness had increased as well as her ability to care for herself and other people. From the clinical perspective, this can be considered a good outcome case of psychoanalytic treatment.

Measures

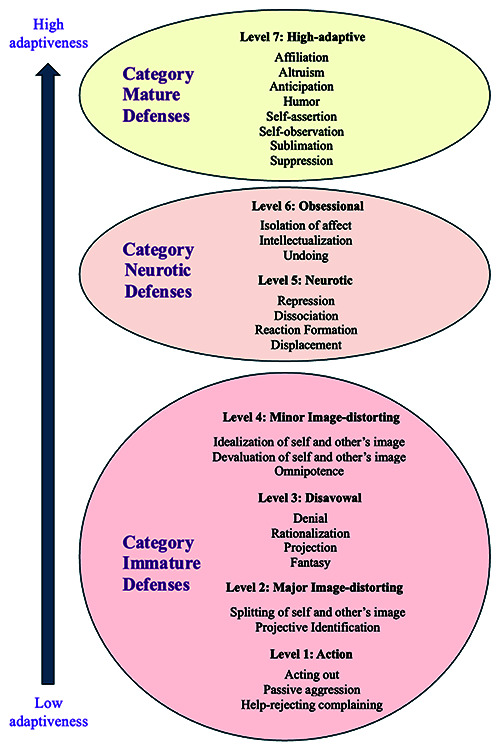

The DMRS (Perry, 1990) is an observer-rated instrument for assessing the entire hierarchy of defense mechanisms. It was adopted as the Provisional Defense Axis in Appendix B of DSM-IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994), there is a large consensus in identifying the DMRS as the gold-standard theory and empirical method for assessing defenses. The DMRS manual provides qualitative and quantitative scoring directions to identify the occurrence of 30 defense mechanisms in a transcript of a clinical interview or therapy session (Perry, 2014). These defenses are further organized into seven defense levels and three defensive categories, which describe the specific defensive function and the level of defensive maturity, respectively (see Di Giuseppe & Perry, 2021 for review). Figure 1 summarizes the hierarchy of defenses as described by the DMRS.

Figure 1.

The hierarchy of defense mechanisms.

The DMRS provides three levels of scoring, yielding continuous, ratio scales (Perry & Bond, 2012). Individual defense scores are proportional or percentage scores, calculated by dividing the number of times each defense was identified by the total defenses observed in the session. Defense level scores are proportional, or percentage scores calculated by dividing the number of times each defense included in the defense level was identified by the total defenses observed in the session. Defensive category scores are proportional, or percentage scores calculated by dividing the number of times each defense included in the defensive category was identified by the total defenses observed in the session. Finally, the ODF is a summary variable informing on the level of defensive maturity and consisting of the mean of each defense used, each weighted by its level. It is useful to note here that Perry and colleagues’ use of the term defense extends the original concept which implied pathology, to include what might more accurately include the term coping skills at the high end of the ODF range (Di Giuseppe et al., 2021).

Procedures

The first author consecutively conducted the ratings on the DMRS for both patient and therapist’s defensive functioning. The rater had over 18 years of experience in coding defenses with the DMRS, with certified inter-rater reliability with the developer of the DMRS (intraclass correlation coefficient above 0.7 on all DMRS subscales, including ODF, defense levels, and individual defenses).

Data analysis

Defensive functioning of both the therapist and the patient was analyzed by comparing the DMRS scores in 20 psychoanalytic sessions. The average scores of each of the five subgroups of consecutive sessions were calculated for ODF and defense levels in both the therapist and the patient. A qualitative analysis of the interactive sequences between therapist and patient was carried out to explore the existence of specific patterns of therapist-patient defenses throughout the treatment. Specifically, we observed which defense mechanism or sequence of defense mechanisms were activated by the patient in response to the therapist’s use of a defense mechanisms, to detect possible repetitive defensive responses in relation to therapist’s use of certain defense mechanisms.-

Results

Therapist’s defensive functioning over the course of treatment

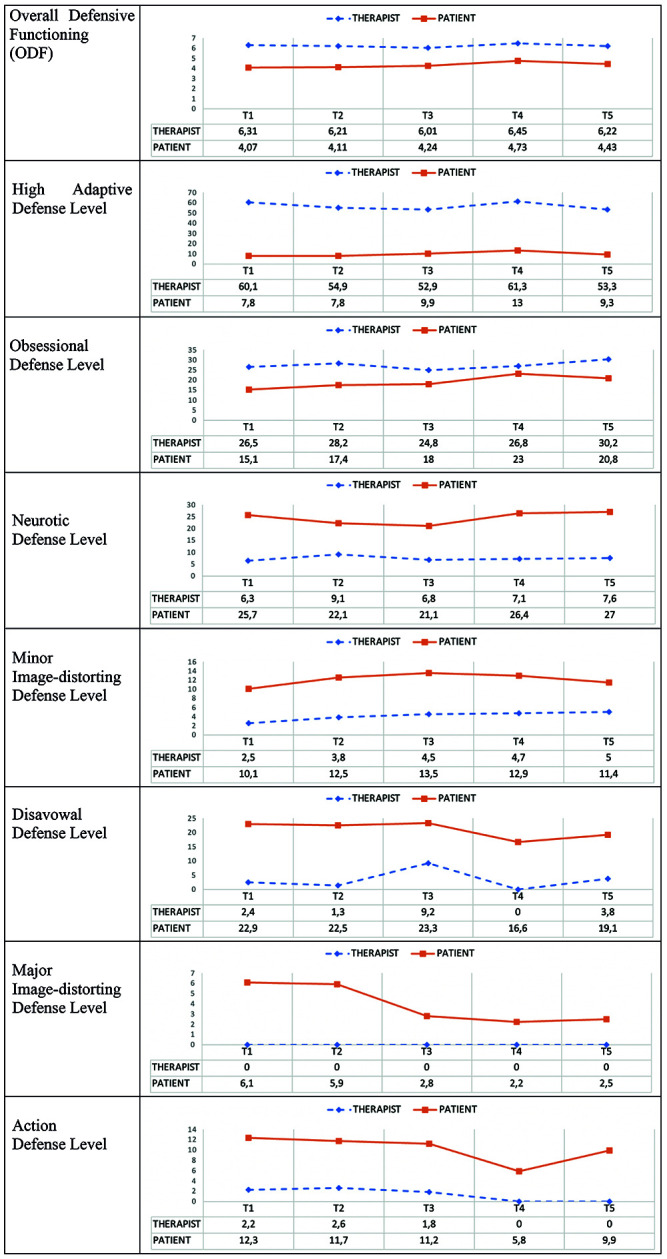

Therapist’s defensive functioning was found to be stable over time as displayed in Figure 2. The overall defensive maturity assessed at 5 times of treatment was on average 6.2 (ranging from ODF=5.3 to ODF=6.8), corresponding to an adaptive defensive functioning.

Figure 2.

Changes in defensive functioning of patient and therapist during the treatment.

Table 1 shows the average use of defense levels in the therapist. Results show that mature defenses represented over half of therapist’s defensive functioning, followed by 27% of obsessional defenses and 7% of neurotic defenses. Immature defenses were rarely used by the therapist during the treatment, contributing only for the 8% to the therapist’s ODF.

Table 1.

Therapist’s defensive functioning in the psychoanalytic treatment with Annie.

| Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | 95% CI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | |||||

| ODF | 6.24 | 0.38 | 5.26 | 6.77 | 6.06 | 6.24 |

| High-adaptive defenses | 56.50 | 11.50 | 31.60 | 76.90 | 51.1 | 61.9 |

| Obsessional defenses | 27.30 | 9.03 | 7.69 | 50.00 | 23.10 | 31.60 |

| Neurotic defenses | 7.37 | 7.54 | 0.00 | 26.30 | 3.84 | 10.90 |

| Minor I-D defenses | 4.11 | 4.91 | 0.00 | 11.80 | 1.81 | 6.41 |

| Disavowal defenses | 3.35 | 5.07 | 0.00 | 15.40 | 0.98 | 5.72 |

| Major I-D defenses | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Action defenses | 1.33 | 2.96 | 0.00 | 10.50 | -0.06 | 2.71 |

ODF, Overall Defensive Functioning; I-D, Image Distorting. ODF score can vary from 1 (lowest) to 7 (highest), while defense level scores are proportional and can vary from 0 (lowest) to 100 (highest).

Patient’s defensive functioning over the course of treatment

Patients’ ODF was 4.09 at the beginning of psychoanalytic treatment. Changes in the patient’s defensive functioning during the treatment are displayed in Figure 2. The ODF increased gradually over the course of treatment, with a slight decrease toward the end of treatment, resulting in a raw increase of approximately 0.4. Defense mechanisms (calculated as defense levels) also changed during the treatment in the expected directions. Results showed that mature, obsessional, and neurotic defense level improved, while minor image-distorting defenses remained stable. Conversely, immature defenses belonging to disavowal, major image distortion, and action defense levels significantly decreased over time.

Patterns of interaction between therapist and patient defensive functioning

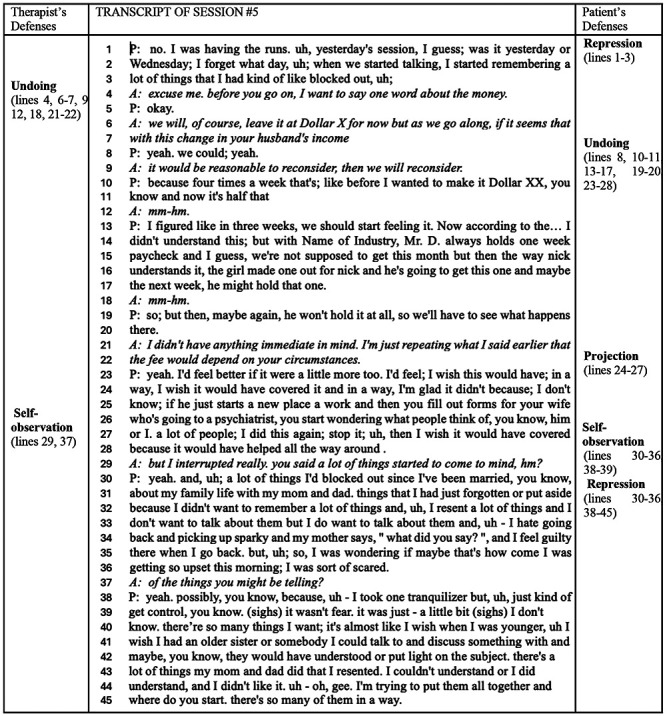

In the early stage of the psychoanalytic treatment, in response to the therapist’s defenses, the patient tends to use similar defense mechanisms. However, this automatic emulation of the therapist’s defense mechanisms is quickly lost, and the patient’s usual immature defensive functioning returns to predominate. The patient’s ODF is therefore quite low at the beginning of treatment. Figure 3 describes an example of this initial trend. After the therapist’s use of undoing (level 6), the patient replies with another undoing, and with a projection at the same time (level 3). Similarly, the therapist responds with a self-observation (level 7), which the patient immediately replies, overlapping it with a repression (level 5).

Figure 3.

Example of therapist-patient match in the use of defenses in the early stage of the treatment (session 5).

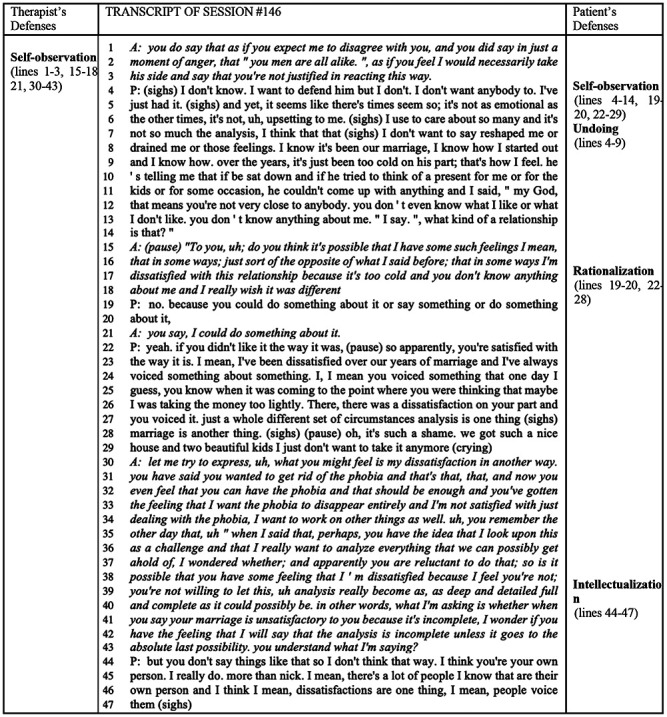

In the middle stage of the psychoanalytic treatment, the sequence of defenses observed in the patient still seems to imitate that of the therapist, but with a greater use of defenses higher in the hierarchy. The patient’s ODF is slightly higher and includes a broader range of defenses from immature to highly adaptive. Figure 4 describes an example of this increased use of defenses higher in the hierarchy. After the therapist’s use of self-observation, the patient sequentially activates self-observation (level 7), undoing (level 6), rationalization (level 3), intellectualization (level 6). The use of several defenses in this segment indicated high defensive activity in the patient, who recurred often to higher-level defenses.

Figure 4.

Example of therapist-patient match in the use of defenses in the middle stage of the treatment (session 146).

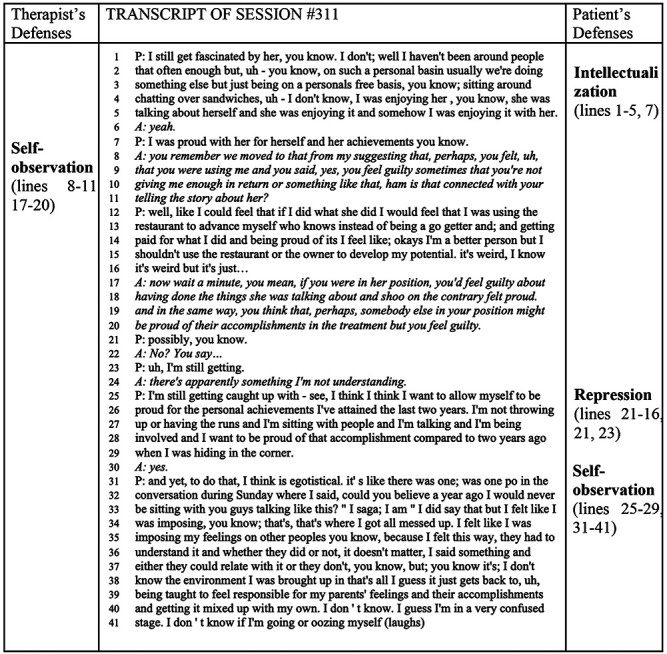

Towards the end of the psychoanalytic treatment, the defenses observed in the patient were more flexible, protean, and adaptive. The patient seemed to use defenses independently from the therapist’s use of defenses. Patient’s ODF was higher at the end stage of the treatment than at the early stage of treatment and were in the range of low neurotic defensive functioning. Figure 5 describes an example of how the patient activated more adaptive defenses independently from therapist’s defenses. The patient used intellectualization (level 6) to which the therapist responded with self-observation (level 7). In response, the patient first used repression (level 5) and then self-observation (level 7), indicating increasingly adaptive strategies to deal with personal conflicts.

Figure 5.

Example of therapist-patient match in the use of defenses in the late stage of the treatment (session 311).

Discussion

Previous research has focused on change in a patient’s defenses (Babl et al., 2019; Kramer et al., 2010; Olson et al., 2011;

Perry & Bond, 2012), however, therapist’s defenses have received very little attention in research so far. This is surprising because therapists are known to contribute to the therapeutic relationship and process overall, furthermore, providing therapy can be stressful also for the therapist and thus likely to activate therapists’ defenses as well. The present study attempted to investigate patterns of change in defense mechanisms from both the patient’s and therapist’s perspectives in a single case of psychoanalytic treatment. The main purpose of the research was to provide empirical evidence to support the hypothesis that the therapeutic process is a teaching and learning process in which the therapist acts as a high-functioning model of coping with life from whom the patient can gradually learn to shape his responses in a more functional and adaptive way. Moreover, the present study aimed at demonstrating that assessing defenses as they occur within the therapeutic dyad may be a relevant measure of both process and outcome in psychotherapy (Gelo et al., 2015; Gennaro et al., 2019).

The first aim of this study was to identify defenses used by the therapist in sessions and over time through using a widely validated measure, the DMRS (Perry, 1990). This method allowed us to identify transcript segments in which the therapist used a defense mechanism for each of the 20 available session transcripts. As expected, the therapist’s defensive functioning was in the adaptive range and remained stable over time. It was characterized by a wide use of mature defenses accompanied mostly by obsessive defenses such as intellectualization, and sometimes neurotic defenses such as repression and displacement. Thus, the therapist may indeed have served as a stable and adaptive model of defensive functioning throughout the course of the treatment, providing a predictable secure base that fostered the development of secure attachment within the psychoanalytic setting.

The second aim was to analyze a patient’s defensive functioning in-session and over the course of treatment. In line with previous studies (Conversano et al., 2023; Perry & Bond, 2012), the patient’s initial defensive maturity corresponded to an ODF of 4.09, which gradually improved during psychoanalytic treatment, but then partially declined near the end. Despite this final slight decrease; overall, the patient’s defensive maturity improved over the course of treatment, as indicated by a significant improvement on the ODF and defense levels higher in the hierarchy. Mature and obsessive defenses followed a similar trend observed for ODF, while immature defenses as action, major image distortion and disavowal defenses showed an opposite trend, resulting in substantial decrease from the middle of the treatment and a slight increase close to the end of the treatment. Instead, change in neurotic and minor image distorting defenses showed a bell-shaped trend, and variation in these defense levels from beginning to end of the psychoanalytic treatment. Whereas neurotic defenses decreased in the early stage of the treatment and then increased in the second half, minor image distorting defenses followed an opposite trend, as they increased in the early stage of the treatment and then decreased in the second half. These results illustrated how adaptive defenses gradually replaced maladaptive ways of dealing with distress, but also informed on different trends of medium-level defenses, which the patient needed to restore at the end of the treatment to sustain the anxiety due to separation from the analyst.

The final aim was to explore the potential patterns of interaction of therapist and patient’s in-session defenses in early and late phase sessions of treatment. From the qualitative analysis of DMRS ratings we detected three different patterns of interaction corresponding to the initial, middle, and final stage of the psychoanalytic treatment. In the initial stage, the patient tended to use the same defense activated by the therapist, as a sort of automatic emulation of an adaptive defensive functioning, which was immediately undone by a subsequent large use of immature defenses. In the middle stage of the psychoanalytic treatment, the patient still tended to activate defenses as those activated by the therapist, but there was a greater presence of defenses higher in the hierarchy. At this point of the treatment, the patient not only imitated the therapist but also began to independently use more adaptive defenses (i.e. mature and obsessive defenses), taking the place of immature defense mechanisms. The patient might have acquired greater self-confidence and awareness of her internal conflict and stressful situations and began to widen her defensive functioning repertoire with various defense mechanisms higher in the hierarchy. Towards the end of the treatment, the patient’s defenses were more flexible, variable, and adaptive, and they were activated independently from those activated by the therapist. At this stage of the treatment, the patient showed a personal style of coping with distress, which included using the whole hierarchy of defenses, but with a greater use of defenses higher in the hierarchy. The patient may have acquired greater awareness by now of her own personal resources and could rely on a larger and more adaptive array of defensive functioning to manage internal and external difficulties, including the end of the psychoanalytic treatment – though the functional regression reported in the clinical literature around termination (e.g. McWilliams, 2004) was observed.

Overall, it appears that the therapist’s use of defenses served, at least initially, a function of implicit learning in which the patient followed the model provided by the more mature personality functioning of the therapist functioning in the treatment role.

Clinical implications

Although limited to a single case report, these findings inspired clinical reflections. The stability of the individual and contextual aspects of the psychotherapeutic process, including therapist’s defensive functioning, may play an important role in promoting improvement in patient’s defensive functioning within the therapeutic setting. A stable and predictable therapist might serve as a secure base from which the patient can re-think their internal working models and encourage the process of individualization through the development of new representations of themselves and others (Farber & Metzger, 2009; Farber et al., 1995).

Changes observed in the patient’s defensive functioning, which concern the transition from maladaptive to adaptive defensive strategies and the partial reactivation of the initial defensive functioning at the end of the treatment, suggest some considerations. If the patient felt supported by the therapist, she might have been able to pursue gradual but significant improvements, imitating the therapist’s coping methods during the course of the treatment. According to Gill’s hypotheses about the role of transference interpretation in changing the functioning of the patient, therapist’s use of interpretations of patient’s defenses and interpretation of the transference in the here and now most likely played a key role in leading to the change (Gill, 1982; Gabbard & Horowitz, 2009). However, close to the conclusion of the psychoanalytic treatment, with the increased anxiety for the coming separation (McWilliams, 2004), she partially regressed to original defensive patterns, possibly linked to her personality structure, which however were finally modulated by a greater defensive maturity achieved in the therapy.

From this perspective, the therapeutic process could be seen as an evolutionary journey of the therapeutic dyad, in which both the therapist and the patient play an important role in improving the patient’s defensive maturity. The therapist interpreted maladaptive strategies, proposed adaptive defensive strategies to manage internal conflicts and external stressors, modelled higher level defenses and gradually influenced the patient’s restyling of her own defenses. Hence, this might highlight the importance of training the therapist in monitoring their own defenses, as they function as a healthy model for the patient and by doing this, also offer the secure base from which the patient’s individuation process can take place (Bowlby, 1988).

Limitations and future research

This study presents several limitations. Firstly, the single case methodology does not allow for generalization but only a qualitative reflection that needs to be tested on larger samples of patients and therapists in psychotherapy. Second, the present study did not investigate other aspects of psychological functioning besides defenses, and therefore does not allow the identification of possible effects on defensive changes brought by other variables that might have impacted on results (i.e. personality traits, reflective functioning, working alliance, etc). Moreover, outcome measures than the DMRS were not used in this study, thus impeding seeing relationships between defenses improvement and therapeutic improvement. Finally, the study considered only psychoanalytic treatment (a psychoanalysis which became what would be called a psychoanalytic psychotherapy halfway through) and did not offer information regarding potential differences between different therapeutic approaches. Future studies should test the relationship between defense improvement and therapeutic improvement by including other processoutcome measures. Future research should also compare various psychotherapy approaches to detect potential differences among treatments in promoting changes in defensive functioning.

Conclusions

The study of defenses in psychotherapy is relevant as it offers information about changes in the patient’s use of defenses over time, but also on the therapist’s ability to address patient’s maladaptive defenses by demonstrating more adaptive ways of coping which the patient gradually learned to use. Once one recasts the topic of what is going on in treatment as helping patients to better manage their own impulses, feelings, and wishes in regard to the external world, then we may see that, in a successful analysis, the patient will achieve higher levels of coping skills. And the question of how or whether this process takes place is well captured by studying the learning and modeling process provided by the analyst in response to the patient’s communications, and the degree to which patients adapt better coping skills.

Psychotherapy, and in particular psychoanalysis, is a learning process about one’s inner life and wishes in relation to dealing with the outside world. Thus, it is important to further explore the therapists’ use of defenses and coping via process-outcome psychotherapy research and systematically include this relevant psychological aspect as an essential part of psychotherapy training of any theoretical approach.

Funding Statement

Funding: this study is part of a larger research that has received funding from the International Psychoanalytic Association under the 2022 IPA Research Grant 2022.

References

- Aafjes-van Doorn K., Békés V., Luo X., Prout T. A., Hoffman L. (2021). what do therapist defense mechanisms have to do with their experience of professional self-doubt and vicarious trauma during the COVID-19 pandemic?. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 647503. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.647503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aafjes-van DoornK., Békés V., Luo X., Prout T. A., Hoffman L. (2022). Therapists’ resilience and posttraumatic growth during the COVID-19 pandemic. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 14(S1), S165-S173. doi: 10.1037/tra0001097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aafjes-van DoornK., Horne S., Barber J. P. (2024). Psychoanalytic process research. (Eds Patrick Luyten & Linda Mayes). Textbook of Psychoanalysis published by the American Psychiatric Association. [Google Scholar]

- Aafjes-van DoornK., Spina D., Gorman B., Stukenberg K, Waldron W. (2024). Implicit relational aspects of the therapeutic relationship in psychoanalytic treatments: an examination of linguistic style entrainment over time. Psychotherapy Research (in press) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (1994). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (4th ed.). American Psychiatric Publishing, Inc.. [Google Scholar]

- Babl A., Grosse HoltforthM., Perry J. C., Schneider N., Dommann E., Heer S., Stähli A., Aeschbacher N., Eggel M., Eggenberg J., Sonntag M., Berger T., Caspar F. (2019). Comparison and change of defense mechanisms over the course of psychotherapy in patients with depression or anxiety disorder: Evidence from a randomized controlled trial. Journal of affective disorders, 252, 212-220. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.04.021 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Békés V., Starrs C. J., Perry J. C. (2023a). The COVID-19 pandemic as traumatic stressor: Distress in older adults is predicted by childhood trauma and mitigated by defensive functioning. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice and Policy, 15(3), 449-457. doi: 10.1037/tra 0001253 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Békés V., Starrs C. J., Perry J. C., Prout T. A., Conversano C., Di Giuseppe M. (2023b). Defense mechanisms are associated with mental health symptoms across six countries. Research in Psychotherapy (Milano), 26(3), 729. doi: 10.4081/ ripppo.2023.729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Békés V., Aafjes-van DoornK., Spina D., Talia A., Starrs C. J., Perry J. C. (2021b). The relationship between defense mechanisms and attachment as measured by observer-rated methods in a sample of depressed patients: a pilot study. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 648503. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021. 648503 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Békés V., Hoffman L. (2020). The “something more” than working alliance: authentic relational moments. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 68(6), 1051-1064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Békés V., Prout T. A., Di Giuseppe M., Wildes AmmarL., Kui T., Arsena G., Conversano C. (2021a). Initial validation of the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales Q-sort: A comparison of trained and untrained raters. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 9(2). doi: 10.13129/2282-1619/mjcp-3107 [Google Scholar]

- Bowlby J. (1988). A secure base: parent-child attachment and healthy human development. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Briggs D. B., Munley P. H. (2008). Therapist stress, coping, career sustaining behavior and the working alliance. Psychological Reports, 103(2), 443–454. doi: 10.2466/PR0.103.6.443-454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carlucci S., Chyurlia L., Presniak M., Mcquaid N., Wiley J. C., Wiebe S., Hill R., Garceau C., Baldwin D., Slowikowski C., Ivanova I., Grenon R., Balfour L., Tasca G. A. (2022). A group’s level of defensive functioning affects individual outcomes in group psychodynamic-inter-personal psychotherapy. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 59(1), 57-62. doi: 10.1037/pst0000423 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carone N., Benzi I. M. A., Muzi L., Parolin L. A. L., Fontana A. (2023). Problematic internet use in emerging adulthood to escape from maternal helicopter parenting: defensive functioning as a mediating mechanism. Research in psychotherapy (Milano), 26(3), 693. doi: 10.4081/ripppo.2023.693 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conversano C., Di Giuseppe M., Lingiardi V. (2023) Case report: Changes in defense mechanisms, personality functioning, and body mass index during psychotherapy with patients with anorexia nervosa. Frontiers in Psychology, 14, 1081467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cramer P. (2015). Defense mechanisms: 40 years of empirical research. Journal of personality assessment, 97(2), 114–122. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2014.947997 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper A. M. (1987). Changes in psychoanalytic ideas: transference interpretation. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 35(1), 77-98. doi: 10.1177/00030651870 3500104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roten Y., Djillali S., Crettaz von Roten F., Despland J. N., Ambresin G. (2021). Defense Mechanisms and Treatment Response in Depressed Inpatients. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 633939. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.633939 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M. (2024). Transtheoretical, transdiagnostic, and empirical-based understanding of defense mechanisms. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 12(1). [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Perry J. C., Prout T. A., Conversano C. (2021). Editorial: Recent empirical research and methodologies in defense mechanisms: Defenses as fundamental contributors to adaptation. Frontiers in Psychology, 12:802602. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.802602 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Orrù G., Gemignani A., Ciacchini R., Miniati M., Conversano C. (2022). Mindfulness and Defense mechanisms as explicit and implicit emotion regulation strategies against psychological distress during massive catastrophic events. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19, 12690. doi: 10.3390/ijerph 191912690 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Giuseppe M., Lingiardi V. (2023). From theory to practice: The need of restyling definitions and assessment methodologies of coping and defense mechanisms. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 30(4), 393–395. doi: 10.1037/cps 0000145 [Google Scholar]

- Di Trani M., Pippo A. C., Renzi A. (2022). Burnout in Italian hospital physicians during the COVID-19 pandemic: the roles of alexithymia and defense mechanisms. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology, 10(1). doi: 10.13129/2282-1619/ mjcp-3250 [Google Scholar]

- Drapeau M., De Roten Y., Perry J. C., Despland J. N. (2003). A study of stability and change in defense mechanisms during a brief psychodynamic investigation. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 191(8), 496–502. doi: 10.1097/01.nmd. 0000082210.76762.ec [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber B. A., Lippert R. A., Nevas D. B. (1995). The therapist as attachment figure. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 32(2), 204–212. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.32.2.204 [Google Scholar]

- Farber B. A., Metzger J. A. (2009). The therapist as secure base. In Obegi J. H., Berant E. (Eds.), Attachment Theory and Research in Clinical Work with Adults (pp. 46–70). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fiorentino F., Lo BuglioG., Morelli M., Chirumbolo A., Di Giuseppe M., Lingiardi V., Tanzilli A. (2024). Defensive functioning in individuals with depressive disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Affective Disorders. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2024.04.091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freud S. (1894). The neuro-psychosis of defence. In Strachey J., Freud A., Strachey A., Tyson A. (1962) The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, Volume III (1893-1899). The Hogarth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gabbard G. O., Horowitz M. J. (2009). Insight, transference interpretation, and therapeutic change in the dynamic psychotherapy of borderline personality disorder. American Journal of Psychiatry, 166(5), 517-521. doi: 10.1176/ appi.ajp. 2008.08050631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galli F., Tanzilli A., Simonelli A., Tassorelli C., Sances G., Parolin M., Cristofalo P., Gualco I., Lingiardi V. (2019). Personality and Personality Disorders in Medication-Overuse Headache: A Controlled Study by SWAP-200. Pain research & management, 2019, 1874078. doi: 10.1155/2019/1874078 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelo O. C.G., Manzo S. (2015). Quantitative approaches to treatment process, change process, and process-outcome research. In Gelo O. C. G., Pritz A., Rieken B. (Eds.), Psychotherapy research: Foundations, process, and outcome (pp. 247–277). Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Gelo O. C. G., Lagetto G., Dinoi C., Belfiore E., Lombi E., Blasi S., Aria M., Ciavolino E. (2020). Which methodological practice(s) for psychotherapy science? A systematic review and a proposal. Integrative Psychological and Behavioral Science, 54(1), 215–248. doi: 10.1007/s12124-019-09494-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelo O. C. G., Pritz A., Rieken B. (2015). Preface. In Gelo O. C. G., Pritz A., Rieken B. (Eds.), Psychotherapy research: Foundations, process, and outcome (pp. v-vi). Springer [Google Scholar]

- Gennaro A., Gelo O. C. G., Lagetto G., Salvatore S. (2019). A systematic review of psychotherapy research topics (2000-2016): a computer-assisted approach. Research in psychotherapy (Milano), 22(3), 429. doi: 10.4081/ripppo.2019.429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gill M. M. (1982). Analysis of transference. New York, NY: International University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gross J. J. (2015). Emotion regulation: Current status and future prospects. Psychological Inquiry, 26(1), 1–26. doi: 10.1080/ 1047840X.2014.940781 [Google Scholar]

- Hayes J. A., Gelso C. J., Hummel A. M. (2011). Managing countertransference. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 48(1), 88–97. doi: 10.1037/a0022182 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kocijan LovkoS., Gregurek R., Karlovic D. (2007). Stress and ego-defense mechanisms in medical staff at oncology and physical medicine departments. European Journal of Psychiatry, 21(4), 279-286. [Google Scholar]

- Kramer U., Despland J. N., Michel L., Drapeau M., de Roten Y. (2010). Change in defense mechanisms and coping over the course of short-term dynamic psychotherapy for adjustment disorder. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 66(12), 1232–1241. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iwakabe S., Gazzola N. (2009). From single-case studies to practice-based knowledge: aggregating and synthesizing case studies. Psychotherapy research: journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 19(4-5), 601–611. doi: 10.1080/ 10503300802688494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus R., Folkman S. (1991). 9. The Concept of Coping. In Monat A., Lazarus R. (Ed.), Stress and Coping: an Anthology (pp. 189-206). New York Chichester, West Sussex: Columbia University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi V., Gazzillo F., Colli A., De Bei F., Tanzilli A., Di Giuseppe M., Nardelli N., Caristo C., Condino V., Gentile D., Dazzi N. (2010). Diagnosis and assessment of personality, therapeutic alliance and clinical exchange in psychotherapy research. Research in Psychotherapy (Milano), 2, 97-124. doi: 10.4081/ripppo.2010.36 [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi V., Lonati C., Delucchi F., Fossati A., Vanzulli L., Maffei C. (1999). Defense mechanisms and personality disorders. The Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 187(4), 224–228. doi: 10.1097/00005053-199904000-00005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyons-Ruth K. (1998). Implicit relational knowing: Its role in development and psychoanalytic treatment. Infant Mental Health Journal, 19(3), 282–289. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0355(199823)19:3<282::AID-IMHJ3>3.0.CO;2-O [Google Scholar]

- Martino G., Viola A., Vicario C. M., Bellone F., Silvestro O., Squadrito G., Schwarz P., Lo Coco G., Fries W., Catalano A. (2023). Psychological impairment in inflammatory bowel diseases: the key role of coping and defense mechanisms. Research in Psychotherapy (Milano), 26(3), 731. doi: 10.4081/ripppo.2023.731 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McWilliams N. (2004). Psychoanalytic psychotherapy. New York: The Guilford Press [Google Scholar]

- Olson T. R., Perry J. C., Janzen J. I., Petraglia J., Presniak M. D. (2011). Addressing and interpreting defense mechanisms in psychotherapy: general considerations. Psychiatry, 74(2), 142–165. doi: 10.1521/psyc.2011.74.2.142 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. C. (1990). Defense Mechanism Rating Scales (DMRS), 5th Edn. Cambridge, MA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. C. (2014). Anomalies and specific functions in the clinical identification of defense mechanisms. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 70(5), 406–418. doi: 10.1002/jclp. 22085 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. C., Beck S. M., Constantinides P., Foley J. E. (2009). Studying change in defensive functioning in psychotherapy using the defense mechanism rating scales: Four hypotheses, four cases. In Levy R. A., Ablon J. S. (Eds.), Handbook of evidence-based psychodynamic psychotherapy: Bridging the gap between science and practice (pp. 121–153). Humana Press/Springer Nature. doi: 10.1007/978-1-59745-444-5_6 [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. C., Bond M. (2012). Change in defense mechanisms during long-term dynamic psychotherapy and five-year outcome. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 169(9), 916–925. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2012. 11091403 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. C., Bond M. (2017). Addressing defenses in psychotherapy to improve adaptation. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 37(3), 153–166. doi: 10.1080/07351690.2017.1285185 [Google Scholar]

- Perry J. C., Ianni F. F. (1998). Observer-rated measures of defense mechanisms. Journal of Personality, 66(6), 993–1024. doi: 10.1111/1467-6494.00040 [Google Scholar]

- Pompili M., Rinaldi G., Lester D., Girardi P., Ruberto A., Tatarelli R. (2006). Hopelessness and suicide risk emerge in psychiatric nurses suffering from burnout and using specific defense mechanisms. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 20(3), 135–143. doi: 10.1016/j.apnu.2005.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prout T. A., Di Giuseppe M., Zilcha-Mano S., Perry J. C., Conversano C. (2022). Psychometric Properties of the Defense Mechanisms Rating Scales-Self-Report-30 (DMRS-SR-30): Internal consistency, Validity and Factor Structure. Journal of Personality Assessment, 104, 833-843. doi: 10.1080/00223891.2021.2019053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice T. R., Hoffman L. (2014). Defense mechanisms and implicit emotion regulation: a comparison of a psychodynamic construct with one from contemporary neuroscience. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 62(4), 693–708. doi: 10.1177/000306 5114546746 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silverman J., Aafjes-van Doorn K. (2023). Coping and defense mechanisms: A scoping review. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice. Advance online publication. doi: 10.1037/cps0000139 [Google Scholar]

- Tanzilli A., Cibelli A., Liotti M., Fiorentino F., Williams R., Lingiardi V. (2022). Personality, Defenses, Mentalization, and Epistemic Trust Related to Pandemic Containment Strategies and the COVID-19 Vaccine: A Sequential Mediation Model. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(21), 14290. doi: 10.3390/ijerph192114290 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tasca A. N., Carlucci S., Wiley J. C., Holden M., El-Roby A., Tasca G. A. (2023). Detecting defense mechanisms from Adult Attachment Interview (AAI) transcripts using machine learning. Psychotherapy research: journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 33(6), 757–767. doi: 10.1080/ 10503307.2022.2156306 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant G. E. (1992). Ego mechanisms of defense: A guide for clinicians and researchers. American Psychiatric Association, New York. [Google Scholar]

- Vaillant G. E. (1994). Ego mechanisms of defense and personality psychopathology. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 103(1), 44–50. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.103.1.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yilmaz M., Türkarslan K. K., Zanini L., Hasdemir D., Spitoni G. F., Lingiardi V. (2024). Transference interpretation and psychotherapy outcome: a systematic review of a no-consensus relationship. Research in psychotherapy (Milano), 27(1), 744. doi: 10.4081/ripppo.2024.744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilcha-Mano S., Fisher H. (2022). Distinct roles of statelike and trait-like patient–therapist alliance in psychotherapy. Nature Reviews Psychology, 1(4), 194-210. doi: 10.1038/ s44159-022-00029-z [Google Scholar]