Abstract

Paclitaxel (PCTX) is one of the most prevalently used chemotherapeutic agents. However, its use is currently beset with a host of problems: solubility issue, microplastic leaching, and drug resistance. Since drug discovery is challenging, we decided to focus on repurposing the drug itself by remedying its drawbacks and making it more effective. In this study, we have harnessed the aqueous solubility of sugars, and the high affinity of cancer cells for them, to entrap the hydrophobic PCTX within the hydrophilic shell of the carbohydrate β-cyclodextrin. We have characterized this novel drug formulation by testing its various physical and chemical parameters. Importantly, in all our in vitro assays, the conjugate performed better than the drug alone. We find that the conjugate is internalized by the cancer cells (A549) via caveolin 1-mediated endocytosis. Thereafter, it triggers apoptosis by inducing the formation of reactive oxygen species. Based on experiments on zebrafish larvae, the formulation displays lower toxicity compared to PCTX alone. Thus, our “Trojan Horse” approach, relying on minimal components and relatively faster formulation, enhances the anti-tumor potential of PCTX, while simultaneously making it more innocuous toward non-cancerous cells. The findings of this study have implications in the quest for the most cost-effective chemotherapeutic molecule.

Keywords: Antineoplasm, Cyclodextrin, Paclitaxel, Electron microscopy, Cell culture, Zebrafish

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction

Cancer accounted for nearly ten million deaths worldwide, or one in six deaths in 2020.1 Of all cancer types, lung cancer alone accounted for 18% of total mortality in 2020. Despite the cumulative contributions of surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, a major challenge in combating the disease is the inability to completely cure it. Although a tremendous number of chemotherapeutic drugs are tested every year, their development is a costly affair. Hence, it would be more practical to improve the efficiency of existing drugs for achieving maximum cytotoxicity. One of the most common drugs used to treat lung cancer is paclitaxel (PCTX), which is sold under the brand name Taxol.2 PCTX is a diterpenoid derived from the bark of the Pacific yew berry tree, and has antineoplastic properties.3 PCTX binds with β tubulin, and induces kinetic suppression of microtubule dynamics. This, in turn, induces cell cycle arrest in the mitotic phase, and prolonged activation of the mitotic checkpoint triggers apoptosis.4,5 One of the major hindrances to achieving maximum paclitaxel efficiency is solubility. As PCTX is barely soluble in aqueous medium, its solubility being less than 0.38 μg/mL in water,6 formulations of cremophor oil and ethanol (1:1) are required to administer the drug.7 However, it has been found that cremophor oil leads to leaching from polyvinyl chloride infusion set8 and poses the risk of generating microplastics.9 Therefore, an alternative to cremophor oil as a medium for paclitaxel delivery is the reformulation of the drug in a hydrophilic vehicle. Reformulation using a water-soluble carrier may also improve the efficacy of anticancer therapy. This can be achieved by approaches such as emulsification, micellization, liposome formation, utilising non-liposomal lipid carriers (nanocapsule), encapsulation, etc.3 Such existing approaches have certain drawbacks, however, e.g. liposome-mediated preparation tends to dissociate after intravenous injection, while nanocapsule formation is expensive.

As a biocompatible, biodegradable, and non-toxic anticancer drug delivery system, starch is a suitable candidate for several reasons. Being a sugar, it is more readily absorbed by cancer cells for fulfilling their high energy demand,10 a phenomenon commonly known as the Warburg effect. In addition, it is cheap, readily available, and easily adsorbed or assimilated into the body without any side effects.11 Starch also contains several hydroxyl groups on its surface, providing hydrophilic properties that make it favourable to load hydrophobic drugs inside it. A study has shown that the bioavailability of drugs increases when porous starch is used as the carrier.12

β-Cyclodextrin (β-CD) is a starch-derived cyclic oligosaccharide, containing seven -(1,4)-linked glucopyranose units.13 It is nontoxic, chemically stable, nonhygroscopic, easily separable and the most used natural dextrin for pharmaceutical industries. The US Food and Drug Administration includes β-CD among Generally Recognized as Safe (GRAS) carriers and protectants.14 The outer surface of this cone-shaped molecule is hydrophilic while its cavity is hydrophobic. Because it is readily water-soluble, it can accommodate various hydrophobic drugs in its non-polar cavity.15 It has also been shown that β-CD, upon embedding a lipophilic compound into its hydrophobic core, forms an inclusion complex and protects chemically non-altered guest molecules from light and oxygen.13

Since as far back as in the nineties, it has been shown that molecular complexing or nanoparticle formation with β-CD improves the aqueous solubility and bioactivity of PCTX while preserving its antitumoral activity both in vitro.16–18 Similar results have been obtained using PCTX/β-CD complex-loaded liposomes against PCTX-resistant cancers.19 However, all existing preparation methods suffer from multiple shortcomings: they require special organic solvents or oil, low temperatures, or stirring up to seven days.20,21

Therefore, we aimed to package paclitaxel into β-CD to make this formulation an efficient and cost-effective drug delivery system by relatively simpler means. This binary system was characterized using Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC), Fluorescence Transformed Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR), Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption Ionization-Time of Flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry, and Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM). The cytotoxic activity and efficacy of the conjugate were verified using [3-(4,5-Dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-Diphenyltetrazolium Bromide] MTT assay, fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based assays, immunocytochemistry, wound healing assays, colony formation assays, and SEM in the A549 lung adenocarcinoma cell line. Furthermore, we tested the developmental toxicity of the conjugate in comparison to PCTX alone in zebrafish larvae.

Materials and methods

Materials

β-Cyclodextrin (β-CD, ≥97%) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Cat No. C4767). Paclitaxel (PCTX, 99%) was obtained from SRL Laboratories (Cat No. 42883). Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) (Cat No. 34869) and Phosphate Buffered Saline (PBS) (Cat No. D5662) was procured from Sigma-Aldrich. The A549 human lung adenocarcinoma cell line was obtained from the National Center for Cell Science, Pune, India. The human embryonic kidney (HEK293) cell line was a kind gift from Dr Ramray Bhat, Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, India.

Synthesis of the conjugate between β-CD and paclitaxel

In a 10 ml solution of minimal DMSO supplemented 1X PBS, β-Cyclodextrin was added. The resulting solution was kept for stirring at 700 rpm at room temperature. The paclitaxel solution (dissolved in DMSO at 2 mg/ml stock concentration) was added dropwise to it over a duration of an hour (Ratio of Paclitaxel: β-CD = 1:5). Using the drug above this concentration led to precipitation of the drug (Supplementary Fig. S1). The solution was kept for stirring for 14–16 hr. This reaction mixture was then collected and lyophilized to get a white solid powder. All our further experiments were carried out using this powder by further solubilizing it into 1X PBS.

Entrapment efficiency and solubility check

The entrapment efficiency (EE) is calculated as the ratio of the amount of the paclitaxel entrapped in the conjugate to that of the total paclitaxel in conjugate suspension. The entrapment efficiency (%) was calculated from the relation: (C - C1)/C × 100, where C is the concentration of paclitaxel used for preparation of the particles and C1 is its concentration remaining after formation of the particles. To measure the entrapment efficiency, a series of dilutions with known concentrations of paclitaxel (0 to 20 μg/ml) was prepared in the DMSO supplemented PBS solvent. This series was used to generate a standard curve (R2 = 0.9961) that relates the absorbance of the solution to the known concentration of PCTX. A certain amount of the PCTX-β-CD conjugate was solubilized in DMSO supplemented PBS solvent and sonicated for 30 min. Then, the sample was diluted further with DMSO supplemented PBS solvent and the sample concentration was determined by measuring UV–Vis absorbance at 230 nm by a Duetta – Fluorescence and Absorbance Spectrometer (Horiba) and fitting the absorbance against the standard curve. The aqueous solubility of PCTX was reported to be low (0.38 μg/mL).6 Henceforth, we also checked if β-CD mediated entrapment of PCTX improves the solubility of PCTX in the aqueous solution.

Differential scanning calorimetry

Thermal analysis of the samples was performed using Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) (Mettler Toledo). Small amounts (~5 mg) of dry samples of β-CD, paclitaxel, the binary conjugate, and a physical mixture (1:5 ratio of PCTX to β-CD) were put in a sealed aluminium pan and heated at a constant rate of 10 °C/min from 30 to 240 °C and cooled at −10 °C/min from 240 to 30 °C twice under nitrogen (N2) purge. The thermogram includes data for β-CD, paclitaxel, the conjugate and the physical mixture.

Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy (FT-IR)

Fourier transformed infrared spectra (FT-IR) of β-CD, paclitaxel, the binary conjugate, and the physical mixture were recorded at room temperature in a spectral region between 4,000 and 650 cm−1 on a PerkinElmer FT-IR Frontier Spectrometer.

Matrix assisted laser desorption ionization-time of flight (MALDI-TOF)

Stock solutions of β-CD and paclitaxel (1 mg/ml each) were prepared (refer Section 2.2). The lyophilised conjugate and the physical mixture were solubilised in DMSO supplemented 1X PBS. All samples were analyzed with Agilent LC (Agilent technologies 1,260 Infinity) coupled to the ESI Qtof mass spectrometer (Bruker Daltonics, Germany). A reverse phase C18 column was used to pass solutions into the ESI chamber at a rate of 0.2 μL/min. Water and acetonitrile were used for the mobile phase, which contained 0.1% formic acid. An acetonitrile gradient of 10% to 90% over 30 min was set. An air nebulizer pressure of 26 psi was used, along with a dry gas temperature of 220 °C and air flow of 9 L/min. Mass spectra in the range of 300–2,750 Da were recorded in positive mode. Repeated measurements yielded nearly identical results. This paper reports only one set of reproducible data. The ESI-MS spectra were acquired with otof software and the data analysis was conducted with compass Data Analysis 4.2 (Bruker Daltonics, Germany).

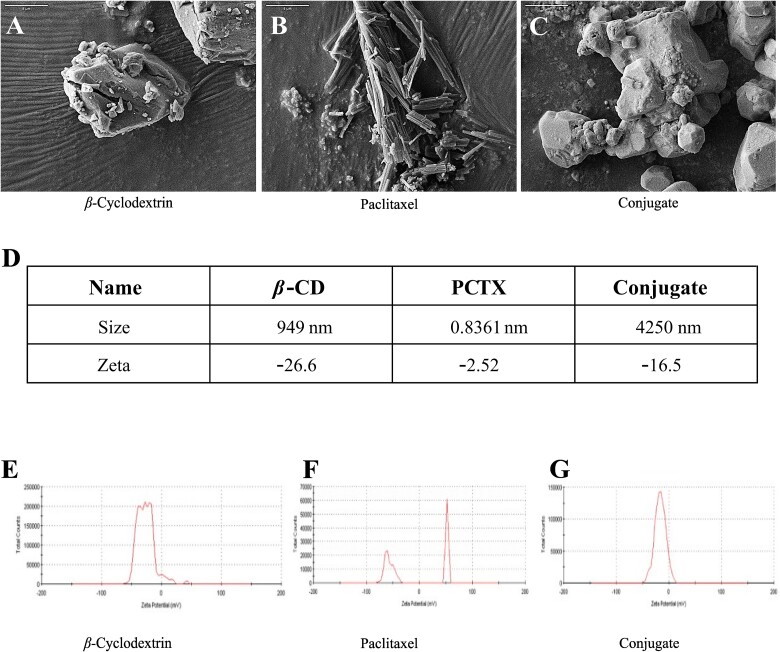

Surface morphology and size measurement

The external morphology of β-CD, PCTX and the conjugate was recorded using a scanning electron microscopy. The samples were allowed to adhere to the double-sided sticky tape on the stub. Thereafter, they were coated with gold for 1 min with a Quorum gold sputter and observed using the Ultra55 FE-SEM (Carl Zeiss). The average hydrodynamic size was determined by dynamic light scattering (DLS) using a Malvern, Nano-ZS zeta potential analyser. Specifically, samples were analysed at 25 °C at an angle of 90°.22

Cell culture

Human non-small cell lung cancer A549 and HEK293 cells were cultured in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% foetal bovine serum (FBS) and penicillin–streptomycin (10,000 U/ml) in a humidified CO2 incubator at 37 °C. Cell morphology was regularly checked using an inverted microscope. All the cell culture reagents and supplements were procured from Gibco. All cultures were monitored regularly for Mycoplasma contamination.

MTT assay

A549 and HEK293 cells were seeded in 96-well culture plates (20,000 cells/well) and incubated overnight in a CO2 incubator. The next day, treatment with both PCTX and the conjugate, ranging from 0.125 μg/ml to 3 μg/ml, was given for 24 hr. Subsequently, the cells were incubated with 0.5 mg/ml MTT for 2 hr in dark in a CO2 incubator. After removing the media, the formed formazan crystal was dissolved in 100 μl of DMSO and absorbance at 595 nm was recorded using a Tecan M200 PRO microplate reader and median inhibitory concentration (IC50) was determined.

Apoptosis assay

Fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS)-based

Apoptosis study was performed using the fluorescein isothiocyanate (FITC)-Annexin V detection kit according to the manufacturer’s protocol (BD Pharmigen, Cat No. 556547). Briefly, cells were washed with cold 1X PBS and resuspended in 1X binding buffer at a concentration of 1 × 106 cells/ml followed by addition of FITC-Annexin V and Propidium Iodide (PI). Then, the tubes were gently vortexed and incubated for 15 min at room temperature followed by analysis using FACS (BD Accuri C6). A total of 10,000 events were acquired; the cells were properly gated and a dual parameter dot plot of FL1-H (x-axis: Fluos-fluorescence) versus FL2-H (y-axis: PI-fluorescence) shown as logarithmic fluorescence intensity, was plotted.

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM)-based

A549 cells were seeded on a glass cover slip followed by treatment with PCTX and the conjugate. Untreated A549 cells were used as a control. Cells were then fixed with 2% glutaraldehyde (TAAB laboratories, Cat. No. G003) and kept at 37 °C for 30 min. After a brief wash using sodium cacodylate (TAAB laboratories, Cat. No. S006) buffer, the cells were fixed with 1% osmium tetroxide (Sigma laboratories, Cat. No. O-5500) followed by serial dehydration with graded ethanol. Imaging was performed using Ultra55 FE-SEM (Carl Zeiss) under the following analytical conditions: Signal A = SE2, EHT = 3 kV, WD = 8.1 mm.

Dichlorodihydrofluorescein diacetate (DCF-DA) staining to measure ROS

We measured ROS levels inside cells with oxidation-sensitive DCF-DA reagents. A549 cells were treated with β-CD, paclitaxel, and the conjugate for 24 hr. The cells were washed with 1X PBS (pH 7.4) and stained with 10 μM of DCF-DA for 30 min at 37 °C wrapped in aluminium foil. The cells were then washed with 1X PBS and examined under FACS (BD Accuri C6). Cells treated with 100 μM H2O2 were used as a positive control.

Mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP) assessment

Mitochondrial potential was checked using a lipophilic cation, the 5,5,6,6-tetrachloro-1,1,3,3-tetraethylbenzimidazolocarbocyanine iodide (JC-1) probe (Sigma-Aldrich). Treated cells were stained with 1.5 μM of JC-1 reagent at 37 °C for 30 min, followed by a brief wash with PBS. The cells were finally harvested in 200 μL of PBS. The stained cells were immediately analysed by the means of a flow cytometer (BD Accuri C6 Plus) using FL1-H vs FL2-H channel. The data were plotted as dot plots using BD Accuri C6 Software.

Immunocytochemistry

Cells on coverslips were washed with PBS, fixed in ice-cold methanol for 10 min and then blocked with 10% FBS in 1X PBS at room temperature for 1 hr. Cells were then incubated with rabbit anti-caveolin 1 primary antibody (Cloud-Clone Corp.) at 1:100 dilution overnight at 4 °C. After washing with PBS, antibody binding was detected by incubating with anti-rabbit Alexa Fluor 488 (Invitrogen) conjugated secondary antibody at a dilution of 1:5000 for 1 hr in dark. Cell nuclei were visualized by staining with Hoechst 33258 (Invitrogen) dye at 1:10000 dilution for 20 min at room temperature. Images were acquired using a Zeiss Confocal 880-Multiphoton system.

Monolayer wound-healing assay

A549 cells were seeded onto 6-well plate at a density of 5 × 105 cells/ml and grown to approximately 90% confluence. The medium was then removed and a scratch was created by scraping the cell monolayer with a p200 pipette tip. Debris were removed by washing the cells with 1 ml PBS, which was then replaced by 0.5% FBS-supplemented DMEM medium along with the corresponding IC50/5 (1/5th time lower of determined IC50) values of the drug and the conjugate.23 Reference points were created by marking the lid of the plate, and images were acquired using a phase-contrast microscope and Olympus Magcam DC 5 CMOS sensor camera. Cells were incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2 and observed periodically until 72 hr. Experiments were performed with three different passages, and the analysis was performed using the ImageJ software.

Colony formation assay

Colony formation assay was carried out to calculate the surviving fraction of cells post drug treatment. A549 cells were seeded in six well plates (1,000 cells/well) and kept for 24 hr. Then, cells were treated with the respective drug concentrations for another 24 hr. The cell culture was maintained for 16 days, with replacement of the old media by fresh media every 72 hr. After 16 days, cells were washed with PBS, fixed with cold methanol, and stained with 0.5% crystal violet at room temperature for 1 hr. After this, the culture plate was washed with distilled water and air dried. The image of the colonies (>50 cells) was captured using a camera and counted.

Zebrafish toxicity assessment

Wild-type Zebrafish were kept in purified tap water at a temperature of 29 °C under a 14- hr light and 10-hr dark cycle, mimicking their natural circadian rhythm. Eggs were obtained using the photo-induced breeding method. Fertilized embryos were then cultured in E3 medium containing specific concentrations of NaCl, KCl, CaCl2, 2H2O, and MgSO4, 7H2O for three days. All experiments were conducted specifically at the three-day post-fertilization stage (3 dpf). Ten numbers of zebrafish three-day old larvae were incubated to assess the toxicity of PCTX and conjugate in a twelve well plate (ThermoFisher, USA). The zebrafish experiments were conducted following the animal welfare guidelines set by the Committee for the Purpose of Control and Supervision of Experiments on Animals (CPCSEA), Government of India [License No. CAF/ETHICS/023/2023].

Statistical analysis

The results were analysed statistically using GraphPad Prism 8.0 software using the Student’s t test. The significance was defined as p < 0.05 (* = P < 0.05, ** = P < 0.01, *** = P < 0.001, **** = P < 0.0001, ns = non-significant).

Results

Characterisation of the conjugate

To synthesize the paclitaxel-β-CD (PCTX) conjugate, we first investigated the favourability between the two compounds. We performed UV–Vis spectroscopy (Fig. S1) using 500 μg/mL β-cyclodextrin and various concentrations of PCTX. A red shift was observed with each successive addition of PCTX, affirming a stable interaction between β-CD and PCTX. We discovered that PCTX forms a stable interaction with 500 μg/mL β-cyclodextrin up to 100 μg/mL, but beyond that concentration of PCTX, β-CD is unable to accommodate the drug, resulting in a disruption of the interaction. Song et al. 24 have also reported that using a 5:1 molar ratio of host to guest led to perfect star polymer formation via inclusion.24 Hence, we decided to accommodate PCTX inside the β-CD molecule in this ratio using the procedure stated in the Methods section. Previous reports have shown that DMSO as a co-solvent enhanced the solubility of poorly soluble drugs.25,26 We have opted for a minimal DMSO concentration for this preparation based on experiments done using isothermal titration calorimetry (data not shown). The following experiments were performed to verify plausible entrapment.

PCTX entrapped well into the β-CD shell with around 71% efficiency for the formulation described in 2.3. The water solubility of conjugated PCTX was found to be improved by over 1,000 times compared to PCTX alone. DSC was performed to determine the drug-excipient interaction and confirm the complexation by studying the enthalpy of absorption or release. The thermograms of β-CD, PCTX, the conjugate (lyophilised powder form), and the physical mixture are shown in Fig. 1A. β-CD exhibited a broad endothermic peak at 120 °C, whereas PCTX exhibited a sharp endothermic peak at 220 °C. In the physical mixture of β-CD and PCTX, the thermogram was characterized by the appearance of two endothermic peaks at 120 °C and 220 °C, respectively, indicating the absence of solid–solid interaction between the two compounds. The effective solid-state interaction between β-CD and PCTX resulted in the disappearance of the sharp endothermic peak at 120 °C and 220 °C in the thermogram for the proposed conjugate, indicating possible formation of a new compound.

Fig. 1.

Biophysical characterization of β-CD, PCTX and, conjugate (A) Differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) thermogram of the different formulations tested shows the melting point of PCTX (indicated with red arrow) appearing in pure PCTX and physical mixture of PCTX and β-CD, which is masked upon entrapment. (B) Fourier-transform infrared spectra (FTIR) of the different formulations tested. (C) Matrix-assisted laser desorption/ionisation-time of flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectra (MS) show the molecular weights of the different formulations tested.

A FT-IR study was conducted to determine the probable solid-state structure formed by host-guest interactions and the resulting spectra are represented in Fig. 1B. The FT-IR spectrum of β-CD consists of the peaks tabulated in Table 1.27 For PCTX, the infrared peaks are summarized in Table 2.28,29

Table 1.

FT-IR spectrum peaks of β-CD.

| Wavelength (cm−1) | Vibration(s) |

|---|---|

| 3280 | O-H stretching |

| 2924 | Medium intense C-H stretching |

| 1644 | H-OH bending |

| 1,152, 1080, 1021 | C-O, C-O-C stretching |

Table 2.

FT-IR spectrum peaks of PCTX.

| Wavelength (cm−1) | Vibration(s) |

|---|---|

| 3403 | N-H/O-H stretching |

| 2944 | CH3/C-H stretching |

| 1580 | C-C ring stretching |

| 1369, 1346 | CH3 deformation |

| 1646 | Amide carbonyl band |

| 1734 | Ester carbonyl band |

| 1705 | Carbonyl peak |

| 1048, 1072 | C-O stretching |

| 966, 709 | Aromatic bands |

For the conjugate, a new broad peak at 3297 cm−1 indicates the presence of an O-H stretching vibration. The sharp peak at 1356 cm−1 is attributed to C-O stretching vibration, and the peak at 1155 cm−1 corresponds to C-O-H bending. The spectrum also shows the absence of characteristic absorption peaks of paclitaxel. The region between dashed lines (1200–1800 cm−1) indicates where there might be some differences between the spectra of PCTX and conjugate. In the case of the physical mixture, the spectra showed a stretching vibration of N-H at 3302 cm−1. In addition, it contains a band at 1152 cm−1, indicating C-O vibrations. Although the interaction between Paclitaxel and β-CD may have resulted in intermolecular H-bonds in the conjugate, there was insufficient evidence to corroborate the creation of conjugate by FT-IR.

Therefore, MALDI-TOF was performed to confirm the conjugate formation. Figure 1C shows the mass spectra for β-CD, PCTX, the conjugate and the physical mixture. The molecular signals, recorded at (m/z) 1135.36 Da and 854.32 Da are assigned as [β-CD + Na] +, and [PCTX + Na] +, respectively. For the conjugate, we saw a distinct peak at m/z 1987.14 Da, confirming the formation of a stable conjugate between β-CD and PCTX together. In case of the physical mixture, we found two separate peaks responsible for the presence of β-CD and PCTX separately. Based on the results from the studies mentioned above, stable conjugate formation was achieved through our methodological approach, but physically mixing β-CD with PCTX is not sufficient to yield the inclusion product.

The microscopic morphological structures of the raw materials and the binary complex were elucidated by SEM (Fig. 2A–C). β-CD appeared irregular in shape, whereas PCTX was seen as aggregates of thin needles. However, after conjugate formation, the original morphology of both parent compounds disappeared. This transformation was further supported by our DLS findings, which indicated probable hydrodynamic sizes of 949 nm for β-CD, 0.8361 nm for PCTX, and 4,250 nm for the conjugate, along with respective zeta potentials of −26.6 mV, −2.52 mV, and − 16.5 mV (Fig. 2E–G). The result indicates that due to incorporation of PCTX into β-CD the overall zeta potential of conjugate falls from −26.6 to −16.5 mV. Because of this low zeta potential, the conjugate tends to get agglomerate and form a big cluster. Taken together, it suggests that clusters of β-CD molecules form a cage to entrap PCTX inside them, indicating the emergence of a new solid phase.

Fig. 2.

Scanning electron micrograph (SEM) of the different formulations tested (A) β-cyclodextrin; (B) paclitaxel; (C) conjugate. Scale bars (5 μm) are indicated on the upper left corner. (D-G) the size distribution and zeta potential of β-cyclodextrin, paclitaxel, and, conjugate.

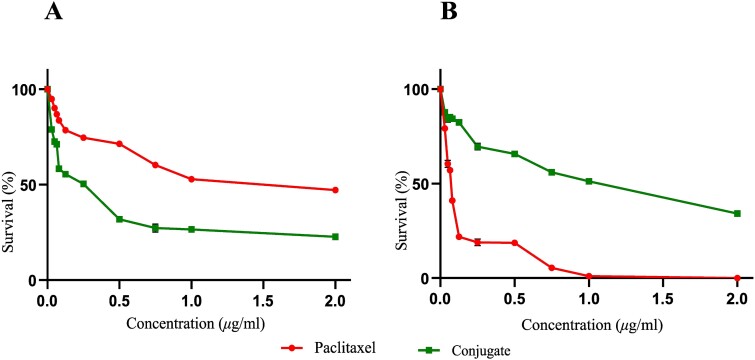

in vitro validation

The efficacy and safety of PCTX and the conjugate was assessed using MTT viability assay in A549 and HEK293 cell lines, respectively. The data indicated that upon treatment with PCTX, the dose-dependent cytotoxicity at which 50% of A549 cells exhibited death (IC50) relative to untreated cells, was 1 μg/mL. However, to our surprise, the conjugated PCTX shows similar anti-cancer activity at a much lower concentration, viz., 0.25 μg/mL (Fig. 3A). Since this chemotherapeutic drug is also known to adversely affect normal cells,30 we assessed its possible effects using the transformed but non-cancerous HEK293 cell line. We noted that PCTX alone can kill more than 50% of cells at a concentration of 0.065 μg/mL, whereas, the conjugate can do so only at 1 μg/mL (Fig. 3B). Together, these findings reveal that the conjugate is profoundly cytotoxic to cancer cells, in contrast to drug treatment alone.

Fig. 3.

Graphical representation of the MTT assay results to assess cell viability for the human cell lines tested: (A) lung adenocarcinoma (A549) [IC50 = 1 μg/mL for only paclitaxel and IC50 = 0.25 μg/mL for conjugated paclitaxel], and (B) embryonic kidney (HEK293) [IC50 = 0.065 μg/mL for only paclitaxel and IC50 = 1 μg/mL for conjugated paclitaxel] upon paclitaxel treatment for 24 hr. results are expressed as the percentage of cell survival relative to untreated control cells.

To corroborate the previous data, we validated the same by performing FACS-based cellular apoptosis assay using Annexin V and PI (Fig. 4A). The results showed that PCTX alone induced apoptotic signs (IC50) in A549 cells at 1 μg/mL, whereas, only 0.25 μg/mL of conjugated PCTX is enough to induce apoptosis.

Fig. 4.

Apoptotic hallmarks upon treatment with various formulations validated using (A) FACS-based assay (US = unstained control, BCD = β-CD, PCTX1 = paclitaxel, Conj = conjugate, H2O2 = hydrogen peroxide), and (B) SEM of A549 cells was performed after treating the cells with PCTX and the conjugate (at IC50) for 24 hr. Compared to untreated cells, the PCTX-treated cells showed partial distortion in cell shape and membrane blebbing, whereas the conjugate-treated cells (at IC50) exhibited several significant hallmarks of apoptosis, including membrane blebbing, the disappearance of microvilli, and the presence of distinct apoptotic bodies. Scale bars (5 μm) are indicated on the upper right corner.

Next, we employed SEM to analyse cellular morphology upon the induction of apoptosis in A549 cells upon drug treatment. Both the untreated cells and the cells treated with β-CD (Fig. 4B) showed morphological features typical of lung adenocarcinoma, with all the healthy cells remaining attached to the surface. The presence of a slightly flattened epithelioid structure possessing microvilli and lamellipodia was observed on the cell surfaces with intact cell membrane. On the other hand, the SE micrograph for PCTX-treated A549 cells showed distortion in cell shape and the blebbing of the cell membrane. After treating cells with the IC50 concentration of the conjugate, we observed several significant hallmarks of apoptotic cells, including cell membrane blebbing and the disappearance of microvilli, as well as the presence of distinct apoptotic bodies. This was also marked by spherical protrusions from these cells with apoptotic bodies on the surface.

Paclitaxel is known to cause apoptosis through various mechanisms, for instance, through the generation of excess ROS.29,31 To assess whether the production of excess ROS was a trigger for the conjugate-mediated apoptosis of A549 cells as well, ROS levels were assessed using the dye DCF-DA. It was found that the conjugate, at only 0.25 μg/mL, induces ROS levels similar to those of paclitaxel at 1 μg/mL (Fig. 5A). These results indicate that conjugated paclitaxel also induces ROS production in A549 cells, which may result in increased oxidative stress damage and apoptosis.

Fig. 5.

FACS-based validation of (A) the formation of ROS using DCF-DA staining, and (B) the impairment of the mitochondrial membrane potential using JC-1 staining. BCD = β-CD, PCTX1 = paclitaxel, Conj = conjugate, H2O2 = hydrogen peroxide.

Excessive production of ROS can incur mitochondrial damage,32 which may result in a decrease in mitochondrial membrane potential (MMP). We therefore measured MMP using the JC-1 assay kit, which contains a cationic dye that turns green upon decrease in membrane potential. Our flow cytometry data (Fig. 5B) showed that while 32.7% cells were green fluorescence positive upon treatment with the IC50 concentration of PCTX, only 0.25 μg/mL of conjugated paclitaxel was sufficient to show around the same population of cells to be green shifted in A549 cells. This implies that a much lesser amount of conjugated PCTX is sufficient to trigger the collapse of mitochondrial membrane potential than the native drug form alone.

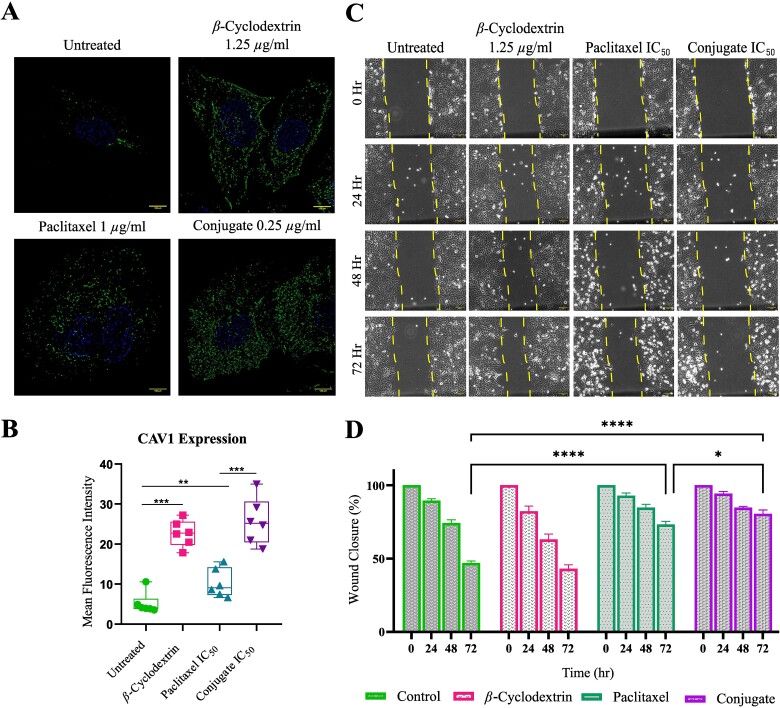

Next, we tried to dissect the mechanism by which the conjugated PCTX can achieve cancer cytotoxicity at a much lesser concentration than PCTX alone. We hypothesized that this could be due to the difference in the mode of delivery of the drug to the cells. To address this, we performed immunocytochemistry using the antibody against caveolin 1 (CAV1). CAV1 plays a role in endocytosis, the process by which cells take in molecules from their surroundings.33 Interestingly, reduced expression levels of CAV1 can limit ROS production and thereby prevent cells from undergoing ROS-induced apoptosis, as observed in BT-474 breast cancer cells.34Fig. 6A shows that in the presence of β-CD there is a significant upregulation of CAV1 than in untreated cells. A biased preference for glucose by cancer cells could explain this.35 When A549 cells were treated with the IC50 concentration of PCTX, an increase in CAV1 expression was noted compared to the untreated control (Fig. 6B). Upon treatment of the cells with the conjugate there was significant upregulation of CAV1 relative to treatment with the drug alone (Fig. 6B), implying successful uptake of the conjugate inside the cells. It has also been reported that increased expression of CAV1 can inhibit cancer metastasis.36 Therefore, in the current study, we have performed an in vitro wound healing assay to verify this correlation (Fig. 6C). The results showed that the conjugate (IC50) can inhibit the migration of A549 cells, whereas, there is a significant closure in the wound area in case of untreated cells as well as the cells treated with 1.25 μg/ml of β-CD. The wound for PCTX-treated cells was around 70% after 72 hr. In case of conjugate treated cells, the wound remained at around 81% (Fig. 6D), connoting improved metastatic inhibition by the reformulated drug.

Fig. 6.

Confocal microscopy analysis of caveolin 1 distribution (CAV1) and scratch assay (A) Representative confocal images of cells stained with anti-CAV1 (green) antibody under different treatment conditions to show cellular distribution of CAV1 in A549 cell line. Cell nuclei were stained with Hoechst (blue). (B) Quantification of CAV1 expression as the mean fluorescence intensity indicates a significant change in CAV1 expression post-treatment between the conjugate and paclitaxel. (C) Differential interference contrast (DIC) images showing results of the wound-healing assay in A549 cells at different time-points post scratch to determine cell migration. Yellow dashed line represents the cell movement boundary. (D) Quantification of percentage of wound closure over time in A549 cells upon drug treatment. (* = P < 0.05, ** = P < 0.01, *** = P < 0.001, **** = P < 0.0001).

The resistance of cancer cells to drug-mediated death is a major challenge in cancer chemotherapy. Therefore, we tried to determine if our reformulated compound could prevent the emergence of resistance colonies through the clonogenic assay. For this, 1,000 A549 cells were given treatment for 24 hr with the IC50 concentrations of PCTX and the conjugated drug, respectively. The effectiveness of this treatment was assessed after 16 days based on the appearance of crystal violet-stained colonies (Fig. 7).

Fig. 7.

Colony-formation assay results (A) Bright field images display petri wells showcasing the outcomes of the clonogenic assay performed on A549 cells after 16 days of treatment. (B) Quantification of crystal violet-stained colonies for different drug treatment. (ns = non-significant, * = P < 0.05).

While PCTX treatment alone gave rise to almost 6 resistant colonies, much fewer or no colonies were observed upon conjugate treatment, indicating that the conjugate could efficiently combat drug resistance in vitro.

in vivo validation

Having demonstrated the efficacy of the conjugate in vitro, we sought to test its physiological effects on a model system. We chose zebrafish larvae for this study because they are an ideal model for drug screening, owing to their small size, large numbers, optical transparency, etc.37,38 Since PCTX is a mitotic inhibitor, we hypothesise that its administration during the rapid succession of larval development may produce various forms of toxicity. As a read-out, we assayed the morphological changes and survival of larvae treated with PCTX alone, and the conjugate. Interestingly, while conjugate does not elicit any developmental toxicity, the PCTX shows different kinds of toxicity like lordosis, shorter body length, mild yolk sac edema and pericardial edema (Fig. 8.). In case of conjugate, on the other hand, toxicity is observed only approaching the lethal concentration (90 μg/mL) in the form of pericardial edema, and it was recorded before they died. The LC50 for PCTX was found to be 55.89 μg/mL, indicating that 50% of the population experienced death at this concentration, while the conjugate had the same impact only at 69.70 μg/mL. (Fig. 8).

Fig. 8.

Teratogenic effects of paclitaxel on the development of zebrafish larvae. Different kinds of phenotypic effects (pe: Pericardial edema; yse: Yolk sac edema; sbl; short body length; lrd; lordosis) were observed upon incubating zebrafish larvae with paclitaxel. Scale bar = 0.5 mm (A) normal larvae. (B) Larvae incubated with 50 μg/mL paclitaxel. (C) Larvae incubated with 55 μg/ml paclitaxel. (D) Larvae incubated with 60 μg/mL paclitaxel. (E) Larvae incubated with 60 μg/mL of conjugated paclitaxel shows no toxicity. (F) Larvae incubated with 90 μg/mL conjugated paclitaxel. (G) Survivability plot to determine LC50 of zebrafish larvae upon incubation with paclitaxel (LC50 = 55.89 μg/ml) and conjugate (LC50 = 69.70 μg/mL).

Discussion

The purpose of developing new chemotherapeutic drug is both time-consuming and financially demanding. For instance, it costs an estimated 2.558 billion USD to develop a new chemotherapeutic drug.39 Repurposing existing anti-cancer drugs to improve their efficacy and overcome resistance would be the most advantageous approach.

Our study chose to repurpose a very commonly used anti-tumor drug, paclitaxel. It is a first generation taxane anticancer agent, being used in clinic since 1992.40 Almost every patient with advanced or metastatic breast cancer in the United States receives a taxane. In general, those who die of the disease are mostly individuals who had stopped responding to taxane therapy.41 This is because the cancer cells develop resistance to chemotherapy, a major obstacle to the success of cancer treatment and patient survival. Since, as compared to normal cells, cancer cells absorb glucose 200 times faster, a “Trojan Horse” approach to overcome resistance could be β-CD based-drug encapsulation, which also ensures better delivery of the anti-cancer drug, higher aqueous solubility, and better stability.17,42

PCTX complexation (EE of around 71%) with β-CD was confirmed by the presence of a PCTX melting point peak in our DSC studies. There is clear evidence of interactions between β-CD and PCTX in the thermograms, but simply mixing two components physically does not allow PCTX to form complex with β-CD. Additionally, we conducted FT-IR analysis to verify the establishment of chemical bonds between drug and host. The spectral analysis indicated that the main characteristic peaks of the physical mixture (Fig. 1A and B) have almost the same chemical features as that of the pure drug, whereas, some new peaks appeared in the conjugate spectra. These spectra did not display the characteristic intense bands of the drug; these bands may have been masked due to entrapment by the carbohydrate. These changes, including the disappearance or shifting of wave numbers of bands indicated possible entrapment of PCTX inside the β-CD shell due to plausible covalent interactions. MALDI-TOF data (Fig. 1C) further corroborates our claim, where we could see one additive peak appearing due to β-CD and PCTX complexation in the conjugate, indicating the formation of a new molecular entity or compound due to covalent bond formation. SEM images (Fig. 2A–C) show the apparent conformation of the binary complex to be distinct from that of the drug alone. Whereas PCTX appears to have a crystalline rod-like morphology, a drastic change in the morphology and shape of the particles was seen in the conjugate. The DLS data suggest that the smaller sized PCTX molecules fit within the larger cavity of β-CD, yielding clusters of the conjugate. We hypothesize that this may allow a high concentration of PCTX to be packaged into a limited space. Conjugating in this manner offers several advantages over conventional drugs, as has been reviewed earlier43,44:

It improves the solubility and bioavailability of drugs by allowing the hydrophobic PCTX to gather in the cavity of β-CD, as the outer shell of the conjugate is hydrophilic.

It aids in shielding drugs from deactivation and maintaining their efficacy while circulating, ultimately enhancing the half-life of drug in blood plasma, and delaying its clearance from the body.

The phenomenon often leads to increased drug delivery to the specific target location due to the expanded dimensions of the conjugate, which tend to foster a higher aggregation of drugs within it.

Taken together, it implies that with our mode of preparation, β-CD can efficiently entrap PCTX in its hollow cavity.

In the present study, the effect of reformulated PCTX was evaluated for its in vitro anticancer activity in the human lung cancer cell line A549 by the MTT assay (Fig. 3A). Earlier studies for CDs have shown that they have no cytotoxicity and are suitable as delivery systems, unlike Cremophor EL.45 IC50 of the formulation clearly indicated that the conjugated PCTX exhibited superior cytotoxic activity (0.25 μg/mL) than PCTX alone (1 μg/mL) in A549 cells. In other words, the repurposed PCTX can induce apoptosis at a concentration four times lower than the drug alone. This has been also confirmed by FACS following the Annexin V apoptosis assay in which fluorochrome-conjugated Annexin V binds to exposed phosphatidylserine molecules located on the outer surface of apoptotic cells (Fig. 4A). Our SEM data also validates the occurrence of cell death visually (Fig. 4B). While treatment with PCTX could initiate only partial membrane blebbing within cells at 1 μg/mL, the conjugate resulted in complete blebbing and the presence of distinct apoptotic bodies at a much lower concentration. The blebs are eventually removed from the cell body to form apoptotic bodies, which are then phagocytosed by surrounding cells, accompanied by changes to the cytoskeleton, particularly the disassembly of actin filaments, which are visible in SEM as lamellipodia detachment. These data suggest that incorporation of PCTX in β-CD has a clear advantage in improving its cytotoxic potential significantly on the cancer cell line as well.

To delve deeper into the mechanism of conjugate-mediated cell death, we further investigated ROS production as a possible stimulator, as PCTX is known to promote the generation of ROS in case of cancer cell cytotoxicity.29,31 ROS act as a double-edged sword in oncogenesis,46 as at low concentration they boost tumorigenesis, but at high concentration they increase apoptosis. Figure 5A showed that treatment with IC50 concentrations of the conjugate evoked a similar or higher levels of ROS and consequent oxidative stress compared to that with PCTX. It could be that ROS is produced due to the release of PCTX within the cell upon internalization of conjugated assemblies. As a consequence of these ROS, mitochondrial membranes depolarize, mitochondrial ATP synthesis is impaired, and DNA damage and cell membrane destruction occur, which ultimately result in apoptosis.47 The JC-1 dye staining to measure mitochondrial membrane potential (Fig. 5B) validates the same, wherein fluorescence transition from red to green alluded to significant mitochondrial dysfunction.

In order to understand how cellular internalization occurs for the conjugate, we sought to investigate the endocytosis pathway. Prior evidence shows that cells take up cyclodextrin by endocytosis.48 Immunocytochemistry for CAV1 (Fig. 6) showed a significant upregulation of this vehicle protein upon PCTX treatment compared to untreated cells. Upon conjugation with β-CD, the conjugated PCTX shows an even stronger upregulation of CAV1 relative to the drug alone. Our explanation for this observation is the following:

First, increased production of CAV1 has led to ROS-mediated apoptosis in case of both PCTX and the conjugate at their respective IC50 concentrations.34,49

Second, evidence shows that CAV1-positive tubules in chinese hamster ovary (CHO) cells are microtubule dependent.50 It is also known that PCTX binds with microtubule components. Thus, it is highly possible that binding of PCTX to the microtubule machinery impedes the endocytosis mediated by CAV1, explaining the decreased signal of CAV1 protein noted upon ICC with only PCTX. For conjugated PCTX, masking by β-CD helps the complex to get internalized and release the drug, without affecting CAV1 activity. The high preference of cancer cells for sugars can also explain this observation.

Lastly, it is known that phosphorylation of CAV1 at the tyrosine-14 residue enhances PCTX-mediated cytotoxicity.51

Since increased expression of CAV1 inhibits breast cancer growth and metastasis,36 the scratch assay also validates the improved anti-migratory effect of conjugated PCTX than the drug alone. It is possible that the cytotoxic effects of the conjugated drug are more pronounced because the cancer cells die probably even before the efflux pumps are activated on the membrane. Our next experiment verifies the same (Fig. 7), wherein, in the in vitro colony formation assay, we barely find drug resistant colonies upon treatment with conjugated PCTX (IC50) after 16 days of experiment. Since chemotherapeutic drugs are known to have adverse effects on healthy cells,30 we tried to verify the cytotoxicity of our conjugate on the HEK293 cell line. We have found that the conjugated PCTX is safer as compared to the drug alone.

Upon validation in vivo, we found that the conjugate shows lesser developmental toxicity in comparison to PCTX alone. Conspicuous phenotypes are only observed at closer to the lethal concentration of the conjugate. These findings are in keeping with our observations for the non-cancerous HEK293 cell line. Such engineered compounds have previously been shown to improve effectiveness of the drug in the physiological system by different studies.52–54 We hypothesise that the β-CD conjugation buffers the direct deleterious effects of the drug, attenuating its cytotoxicity. This further highlights the safety and promising utility of our formulation for live organisms.

Conclusion

Our findings reveal that β-cyclodextrin-conjugated paclitaxel, being more effective at lower doses compared to the drug alone, offers the best of both worlds: price and power. On one hand, the conjugate is a cost-effective alternative to the classical drug, and, on the other, it exhibits water-based solubility, better cytotoxicity, can inhibit metastasis, and can avert the emergence of drug-resistant colonies in vitro in A549 cell line in vivo testing in zebrafish larvae showed that PCTX-β-CD complex is less toxic than PCTX alone. Further research is needed to explore the in vivo performance of this PCTX-β-CD complex in higher model organisms and its potential for clinical translation.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Sautan Show is supported by Senior Research Fellowship by University Grants Commission (NOV2017-340916). Dr Debanjan Dutta is supported by the Indian Council of Medical Research (ICMR) fellowship (F. NO. 2020-7170/ GTR BMS). We would like to acknowledge the fluorescence-activated cell sorting (FACS) facility, Developmental Biology and Genetics (DBG), liquid chromatography mass spectrometry facility and Horiba Technical Centre, Indian Institute of Science. We would like to acknowledge the support of the Indian Institute of Science (IE/REDA-23-1788.18), and Mahajana Education Society for infrastructure and financial assistance. We also thank Prof. Ramray Bhat and Prof. Bikramjit Basu (IISc) for their suggestions and support behind this work. Our gratitude to Mr Amartya Mukherjee and Ms Ramya Shekhar for reviewing the entire manuscript.

Contributor Information

Sautan Show, Department of Biochemistry, Pooja Bhagavat Memorial Mahajana Postgraduate Centre, K.R.S. Road, Metagalli, Mysore 570016, India; Department of Developmental Biology and Genetics, Indian Institute of Science, CV Raman Rd, Bengaluru 560012, India.

Debanjan Dutta, Department of Developmental Biology and Genetics, Indian Institute of Science, CV Raman Rd, Bengaluru 560012, India; Life Science Division, AgriVet Life Science, AgriVet Research & Advisory (P) Ltd., Lake Town Rd, Block A, Lake Town, South Dumdum, West Bengal 700089, India.

Upendra Nongthomba, Department of Developmental Biology and Genetics, Indian Institute of Science, CV Raman Rd, Bengaluru 560012, India.

Mahadesh Prasad A J, Department of Biochemistry, Pooja Bhagavat Memorial Mahajana Postgraduate Centre, K.R.S. Road, Metagalli, Mysore 570016, India.

Author contributions

Sautan Show: Investigation, Methodology, Formal analysis, Visualization, Software, Writing– original draft, Debanjan Dutta: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing- review and editing, Upendra Nongthomba: Visualization, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Supervision, Mahadesh Prasad AJ.: Data curation, Validation, Writing- review and editing, Supervision.

Conflict of interest: S.S. reports financial support was provided by University Grants Commission. D.D. reports financial support was provided by Indian Council of Medical Research. U.N. reports financial support, administrative support, and equipment, drugs, or supplies were provided by Indian Institute of Science. M.P.AJ. reports financial support was provided by Pooja Bhagavat Memorial Mahajana Post Graduate Centre. S.S., D.D., U.N., M.P.AJ. has an Indian patent pending to 202341062942. If there are other authors, they declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Data availability

Data will be made available on request.

Reference

- 1. World Health Organization (WHO) . 2022. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer.

- 2. RxList . 2022. https://www.rxlist.com/taxol-drug.htm#description.

- 3. Singla AK, Garg A, Aggarwal D. Paclitaxel and its formulations. Int J Pharm. 2002:235(1–2):179–192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Jordan MA. Mechanism of action of antitumor drugs that interact with microtubules and tubulin. Curr Med Chem Anti-Cancer Agents. 2002:2(1):1–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Foland TB, Dentler WL, Suprenant KA, Gupta ML Jr, Himes RH. Paclitaxel-induced microtubule stabilization causes mitotic block and apoptotic-like cell death in a paclitaxel-sensitive strain of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Yeast. 2005:22(12):971–978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Shah M, Shah V, Ghosh A, Zhang Z, Minko T. Molecular inclusion complexes of β-cyclodextrin derivatives enhance aqueous solubility and cellular internalization of paclitaxel: Preformulation and in vitro assessments. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2015:2(2):8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chen Q, Xu S, Liu S, Wang Y, Liu G. Emerging nanomedicines of paclitaxel for cancer treatment. J Control Release. 2022:342:280–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Gelderblom H, Verweij J, Nooter K, Sparreboom A. Cremophor EL: the drawbacks and advantages of vehicle selection for drug formulation. Eur J Cancer. 2001:37(13):1590–1598. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Henkel C, Hüffer T, Hofmann T. Polyvinyl chloride microplastics leach phthalates into the aquatic environment over decades. Environ Sci Technol. 2022:56(20):14507–14516. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Orang AV, Petersen J, McKinnon RA, Michael MZ. Micromanaging aerobic respiration and glycolysis in cancer cells. Mol Metab. 2019:23:98–126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Paleos CM, Sideratou Z, Tsiourvas D. Drug delivery systems based on hydroxyethyl starch. Bioconjug Chem. 2017:28(6):1611–1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Li Y, Zhao X, Wang L, Liu Y, Wu W, Zhong C, Zhang Q, Yang J. Preparation, characterization and in vitro evaluation of melatonin-loaded porous starch for enhanced bioavailability. Carbohydr Polym. 2018:202:125–133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Gong L, Li T, Chen F, Duan X, Yuan Y, Zhang D, Jiang Y. An inclusion complex of eugenol into β-cyclodextrin: preparation, and physicochemical and antifungal characterization. Food Chem. 2016:196:324–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kali G, Haddadzadegan S, Bernkop-Schnürch A. Cyclodextrins and derivatives in drug delivery: New developments, relevant clinical trials, and advanced products. Carbohydr Polym. 2024;324:121500. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Vukic MD, Vukovic NL, Popovic SL, Todorovic DV, Djurdjevic PM, Matic SD, Mitrovic MM, Popovic AM, Kacaniova MM, Baskic DD. Effect of β-cyclodextrin encapsulation on cytotoxic activity of acetylshikonin against HCT-116 and MDA-MB-231 cancer cell lines. Saudi Pharm J. 2020:28(1):136–146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Sharma US, Balasubramanian SV, Straubinger RM. Pharmaceutical and physical properties of paclitaxel (Taxol) complexes with cyclodextrins. J Pharm Sci. 1995:84(10):1223–1230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Alcaro S, Ventura CA, Paolino D, Battaglia D, Ortuso F, Cattel L, Puglisi G, Fresta M. Preparation, characterization, molecular modeling and in vitro activity of paclitaxel-cyclodextrin complexes. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2002:12(12):1637–1641. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hamada H, Ishihara K, Masuoka N, Mikuni K, Nakajima N. Enhancement of water-solubility and bioactivity of paclitaxel using modified cyclodextrins. J Biosci Bioeng. 2006:102(4):369–371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Shen Q, Shen Y, Jin F, Du YZ, Ying XY. Paclitaxel/hydroxypropyl-β-cyclodextrin complex-loaded liposomes for overcoming multidrug resistance in cancer chemotherapy. J Liposome Res. 2020:30(1):12–20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Bilensoy E, Gürkaynak O, Doğan AL, Hıncal AA. Safety and efficacy of amphiphilic ß-cyclodextrin nanoparticles for paclitaxel delivery. Int J Pharm. 2008a:347(1–2):163–170. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Bilensoy E, Gürkaynak O, Ertan M, Şen M, Hıncal AA. Development of nonsurfactant cyclodextrin nanoparticles loaded with anticancer drug paclitaxel. J Pharm Sci. 2008b:97(4):1519–1529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dutta D, Mukherjee R, Patra M, Banik M, Dasgupta R, Mukherjee M, Basu T. Green synthesized cerium oxide nanoparticle: a prospective drug against oxidative harm. Colloids Surf B: Biointerfaces. 2016:147:45–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Hasenoehrl C, Schwach G, Ghaffari-Tabrizi-Wizsy N, Fuchs R, Kretschmer N, Bauer R, Pfragner R. Anti-tumor effects of shikonin derivatives on human medullary thyroid carcinoma cells. Endocr connect. 2017:6(2):53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Song X, Wen Y, Zhu JL, Zhao F, Zhang ZX, Li J. Thermoresponsive delivery of paclitaxel by β-cyclodextrin-based poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) star polymer via inclusion complexation. Biomacromolecules. 2016:17(12):3957–3963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Senac C, Desgranges S, Contino-Pépin C, Urbach W, Fuchs PF, Taulier N. Effect of dimethyl sulfoxide on the binding of 1-Adamantane carboxylic acid to β-and γ-Cyclodextrins. Acs Omega. 2018:3(1):1014–1021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. M. Alshahrani S, Shakeel F. Solubility data and computational modeling of baricitinib in various (DMSO+ water) mixtures. Molecules. 2020:25(9):2124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Devi TR, Gayathri S. FTIR and FT-Raman spectral analysis of paclitaxel drugs. Int J Pharm Sci Rev Res. 2010:2:106–110. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Martins KF, Messias AD, Leite FL, Duek EA. Preparation and characterization of paclitaxel-loaded PLDLA microspheres. Mater Res. 2014:17(3):650–656. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Ren X, Zhao B, Chang H, Xiao M, Wu Y, Liu Y. Paclitaxel suppresses proliferation and induces apoptosis through regulation of ROS and the AKT/MAPK signaling pathway in canine mammary gland tumor cells. Mol Med Rep. 2018:17(6):8289–8299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nurgali K, Jagoe RT, Abalo R. Adverse effects of cancer chemotherapy: anything new to improve tolerance and reduce sequelae? Front Pharmacol. 2018:9:245. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Mohiuddin M, Kasahara K. The mechanisms of the growth inhibitory effects of paclitaxel on gefitinib-resistant non-small cell lung cancer cells. Cancer Genomics & Proteomics. 2021:18(5):661–673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Yang S, Li X, Dou H, Hu Y, Che C, Xu D. Sesamin induces A549 cell mitophagy and mitochondrial apoptosis via a reactive oxygen species-mediated reduction in mitochondrial membrane potential. Korean J Physiol Pharmacol. 2020:24(3):223–232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Chung YC, Chang CM, Wei WC, Chang TW, Chang KJ, Chao WT. Metformin-induced caveolin-1 expression promotes T-DM1 drug efficacy in breast cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2018:8(1):3930. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Wang R, Li Z, Guo H, Shi W, Xin Y, Chang W, Huang T. Caveolin 1 knockdown inhibits the proliferation, migration and invasion of human breast cancer BT474 cells. Mol Med Rep. 2014:9(5):1723–1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Chae YC, Kim JH. Cancer stem cell metabolism: target for cancer therapy. BMB Rep. 2018:51(7):319–326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Sloan EK, Stanley KL, Anderson RL. Caveolin-1 inhibits breast cancer growth and metastasis. Oncogene. 2004:23(47):7893–7897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Dutta D, Show S, Pal A, Anifowoshe AT, Aj MP, Nongthomba U. The association of cysteine to thiomersal attenuates its apoptosis-mediated cytotoxicity in zebrafish. Chemosphere. 2024:350:141070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Mukherjee A, Dutta S, Nongthomba U. Two to tango: untangling inter-organ communication using Drosophila melanogaster and Danio rerio. iSci Notes. 2021:6(6):1–3. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Katayama ES, Hue JJ, Bajor DL, Ocuin LM, Ammori JB, Hardacre JM, Winter JM. A comprehensive analysis of clinical trials in pancreatic cancer: what is coming down the pike? Oncotarget. 2020:11(38):3489–3501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Ojima I, Lichtenthal B, Lee S, Wang C, Wang X. Taxane anticancer agents: a patent perspective. Expert Opin. Ther. Pat. 2016:26(1):1–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kutuk O, Letai A. Alteration of the mitochondrial apoptotic pathway is key to acquired paclitaxel resistance and can be reversed by ABT-737. Cancer Res. 2008:68(19):7985–7994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pawar CS, Prasad NR, Yadav P, Enoch IMV, Manikantan V, Dey B, Baruah P. Enhanced delivery of quercetin and doxorubicin using β-cyclodextrin polymer to overcome P-glycoprotein mediated multidrug resistance. Int J Pharm. 2023:635:122763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Păduraru DN, Niculescu AG, Bolocan A, Andronic O, Grumezescu AM, Bîrlă R. An updated overview of cyclodextrin-based drug delivery systems for cancer therapy. Pharmaceutics. 2022:14(8):1748. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Junyaprasert VB, Thummarati P. Innovative design of targeted nanoparticles: polymer–drug conjugates for enhanced cancer therapy. Pharmaceutics. 2023:15(9):2216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bouquet W, Boterberg T, Ceelen W, Pattyn P, Peeters M, Bracke M, Remon JP, Vervaet C. In vitro cytotoxicity of paclitaxel/beta-cyclodextrin complexes for HIPEC. Int J Pharm. 2009:367(1–2):148–154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Pan JS, Hong MZ, Ren JL. Reactive oxygen species: a double-edged sword in oncogenesis. World J Gastroenterol. 2009:15(14):1702–1707. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Murphy MP. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. Biochem J. 2009:417(1):1–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Wang S, Hu Y, Yan Y, Cheng Z, Liu T. Sotetsuflavone inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis of A549 cells through ROS-mediated mitochondrial-dependent pathway. BMC Complement Altern Med. 2018:18(1):1–11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Réti-Nagy K, Malanga M, Fenyvesi É, Szente L, Vámosi G, Váradi J, Bácskay I, Fehér P, Ujhelyi Z, Róka E, et al. Endocytosis of fluorescent cyclodextrins by intestinal Caco-2 cells and its role in paclitaxel drug delivery. Int J Pharm. 2015:496(2):509–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Mundy DI, Machleidt T, Ying YS, Anderson RG, Bloom GS. Dual control of caveolar membrane traffic by microtubules and the actin cytoskeleton. J Cell Sci. 2002:115(22):4327–4339. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Shajahan AN, Wang A, Decker M, Minhall RD, Liu MC, Clarke R. Caveolin-1 tyrosine phosphorylation enhances paclitaxel-mediated cytotoxicity. J Biol Chem. 2007:282(8):5934–5943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Biswas S, Datta LP, Roy S. A stimuli-responsive supramolecular hydrogel for controlled release of drug. J. Mol. Eng. Mater. 2017:05(03):1750011. [Google Scholar]

- 53. Datta LP, Manchineella S, Govindaraju T. Biomolecules-derived biomaterials. Biomaterials. 2020:230:119633. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Biswas S, Datta LP, Das TK. A bioinspired stimuli-responsive amino acid-based antibacterial drug delivery system in cancer therapy. New J Chem. 2022:46(15):7024–7031. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.