Abstract

Marine microalgae are the primary producers of ω3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), such as octadecapentaenoic acid (OPA, 18:5n-3) and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6n-3) for food chains. However, the biosynthetic mechanisms of these PUFAs in the algae remain elusive. To study how these fatty acids are synthesized in microalgae, a series of radiolabeled precursors were used to trace the biosynthetic process of PUFAs in Emiliania huxleyi. Feeding the alga with 14C-labeled acetic acid in a time course showed that OPA was solely found in glycoglycerolipids such as monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) and digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG) synthesized plastidically by sequential desaturations while DHA was exclusively found in phospholipids synthesized extraplastidically. Feeding the alga with 14C-labeled α-linolenic acid (ALA), linoleic acid (LA), and oleic acid (OA) showed that DHA was synthesized extraplastidically from fed ALA and LA, but not from OA, implying that the aerobic pathway of DHA biosynthesis is incomplete with missing a Δ12 desaturation step. The in vitro enzymatic assays with 14C-labeled malonyl-CoA showed that DHA was synthesized from acetic acid by a PUFA synthase. These results provide the first and conclusive biochemistry evidence that OPA is synthesized by a plastidic aerobic pathway through sequential desaturations with the last step of Δ3 desaturation, while DHA is synthesized by an extraplastidic anaerobic pathway catalyzed by a PUFA synthase in the microalga.

Keywords: octadecapentaenoic acid, docosahexaenoic acid, PUFA Δ3 desaturase, biosynthesis, Emiliania huxleyi

Marine microalgae are the primary producers of many important biochemicals such as proteins, triacylglycerols, carotenoids and carbohydrates that are widely used for food, feed and bioproducts (1, 2). In particular, they are the primary producers of several nutritionally important ω3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) such as docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6-4,7,10,13,16,19), eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA, 20:5-5,8,11,14,17) and octadecapentaenoic acid (OPA, 18:5-3,6,9,12,15), providing a vital source of these fatty acids for food chains. Because of significant contribution to ecosystems and food chains, marine algae have recently received much scientific attention. Progress has been made on improving photosynthetic rates, biomass production and yield of ω3 PUFAs (3, 4). However, entire biosynthetic mechanisms of these ω3 PUFAs in marine microalgae remain to be elucidated.

Emiliania huxleyi is a widely occurring eukaryotic unicellular marine alga belonging to the coccolithophore family with a distinctive structure of coccoliths made of calcium carbonate. Due to abundance in oceans, it has high impacts on marine ecosystems and carbon cycles (5, 6, 7, 8). In particular, it produces predominantly ω3 PUFAs such as OPA and DHA. OPA is a PUFA with 18 carbons and five double bonds found in many marine microalgae, such as prymnesiophyceae, dinophyceae, raphidophyceae, and dinoflagellates (9, 10, 11). However, little information is available for biosynthesis and function.

In nature, there are two distinct pathways for the biosynthesis of PUFAs (12, 13). The aerobic pathway requires molecular oxygen as a cofactor for desaturations and involves multiple desaturases and elongases working together on precursor long-chain saturated fatty acids to produce PUFAs (14), while the anaerobic pathway does not require oxygen for desaturations and involves only a single mega-enzyme called PUFA synthase for the de novo biosynthesis of PUFAs from initial precursor acetic acid (15). During or after the biosynthesis of PUFAs, these fatty acids or their intermediates are usually incorporated into different types of intracellular glycerolipids. In plants and algae, these fatty acids can be found in plastidic glycoglycerolipids (GL) such as monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) and digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG) in plastids and extraplastidic phosphoglycerolipids (PL) such as phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) in cytosol. In plants, the biosynthesis of very long-chain PUFAs such as DHA does not occur. In microalgae, biosynthesis of the fatty acid is believed to follow the aerobic pathway utilizing desaturases to introduce double bonds and elongases to extend acyl chains. For instance, oleic acid (OA, 18:1-9) is desaturated to linoleic acid (LA, 18:2-9,12) by a Δ12 desaturase, and LA is desaturated to α-linolenic acid (ALA, 18:3-9,12,15) by a Δ15 desaturase. ALA can then be converted to EPA through sequential Δ6 desaturation, Δ6 elongation and Δ5 desaturation. Alternatively, ALA can also be elongated to eicosatrienoic acid (ETA, 20:3-11,14,17) by Δ9 elongase, and then desaturated by Δ8 desaturase and Δ5 desaturase to EPA (16, 17, 18). EPA is then elongated by Δ5 elongase, and desaturated by Δ4 desaturase (14) to DHA. The anaerobic pathway for the biosynthesis of PUFAs catalyzed by PUFA synthase has not been functionally identified in microalgae, although it widely occurs in prokaryotic bacteria and eukaryotic protists and fungi (19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28).

This study aimed to elucidate the biosynthetic process of PUFAs, particularly for OPA and DHA in microalga E. huxleyi using a series of radiolabeled precursors for metabolic tracing. When fed with 14C-labeled acetic acid in a time course, the alga produced labeled OPA found in glycoglycerolipids MGDG and DGDG, and labeled DHA found in phospholipids PC and PE. When fed with 14C-labeled intermediate fatty acids, the alga could produce labeled DHA found in PL from ALA and LA but not from OA. The in vitro enzymatic assays with acetyl-CoA and 14C-labeled malonyl-CoA showed that DHA could be de novo synthesized by a PUFA synthase. Collectively, these results indicate that OPA is synthesized by a plastidic aerobic pathway through sequential desaturations with the last step of Δ3 desaturation, while DHA is synthesized by an extraplastidic anaerobic pathway catalyzed by a PUFA synthase in E. huxleyi.

Results

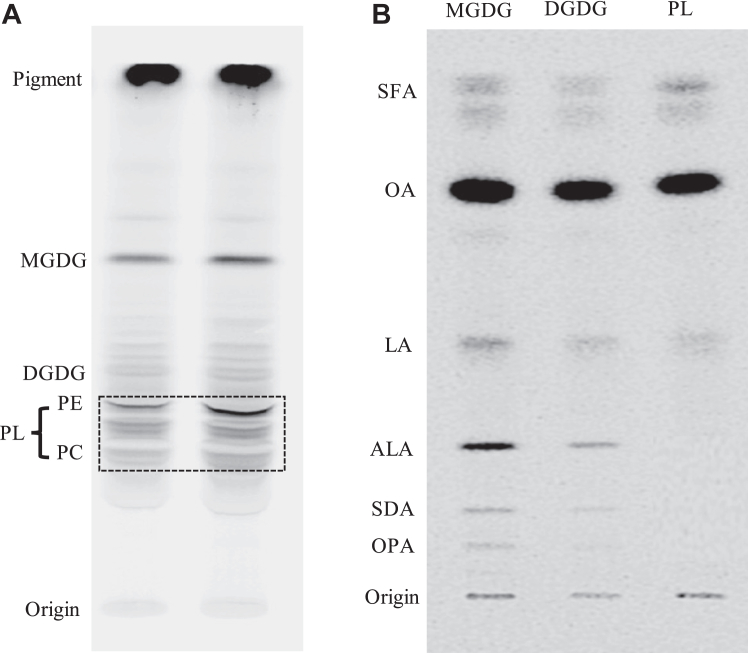

Lipid and fatty acid profiles of E. huxleyi

To analyze the lipid and fatty acid profiles of E. huxleyi, total lipids were isolated from the alga grown at the optimal temperature (18 ) and separated into different lipid classes by thin layer chromatography (TLC), and their fatty acid profiles were subsequently determined by gas chromatography (GC). As shown in Figure 1A, the major lipid classes in E. huxleyi under the culture condition were glycoglycerolipids (GL) including monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG) and digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG), phosphoglycerolipids (PL) such as phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE), and betaine lipids (BL) as well as lipophilic pigments. In glycoglycerolipids MGDG and DGDG, major fatty acids were long chain PUFAs such as OPA, stearidonic acid (SDA, 18:4-6,9,12,15), and saturated fatty acids such as 14:0, but no DHA present. In phospholipids PC and PE, major fatty acids were saturated fatty acids 14:0 and 16:0, and DHA was substantially detected in PC, but no OPA detected in both PLs (Fig. 1B). This result indicates that OPA is solely present in plastidic GLs while DHA resides exclusively in extraplastidic PLs of E. huxleyi.

Figure 1.

Lipid and fatty acid profiles of Emiliania huxleyi.A, TLC separation of total lipids from E. huxleyi into MGDG, DGDG, betaine lipids (BL), PE and PC with two lane replicates, and standards (STD: MGDG, DGDG, PE and PC). B, gas chromatograms of fatty acids in major lipid classes (total lipids, MGDG, DGDG, PE and PC).

Feeding the alga with radiolabeled acetic acid

Acetic acid is an initial precursor for the biosynthesis of all fatty acids including long-chain saturated fatty acids such as 16:0 and 18:0 synthesized by fatty acid synthase, and very long-chain PUFAs such as DHA by PUFA synthase. To trace the biosynthetic process of two nutritionally important ω3 PUFAs, OPA and DHA, in E. huxleyi, steady-state labeling of the alga grown at the optimal temperature with radiolabeled acetic acid in a 24-h time course was performed. Labeled lipids and fatty acid profiles at the five time points in the time course were analyzed by TLC. As shown in Figures 2A and S1A, the most abundantly labeled lipid classes in the time course were lipophilic pigments, PE and PC, followed by MGDG, DGDG and BL. With the labeling time going on, the accumulation of radioactivity increased in these lipids. The most abundantly labeled fatty acids in the total lipids in the time course were saturated fatty acids such as 18:0 and 14:0, followed by OA, DHA, ALA, LA, SDA, and OPA as well as some unknown compounds. It was noted that DHA appeared at the 3-h time point of the labeling course, earlier than OPA that appeared at the 6-h time point of labeling. With the labeling time increasing, the radioactivity of both fatty acids increased; however, DHA was labeled at a higher level than OPA in the entire course (Figs. 2B and S1B). The major labeled fatty acids in GLs were OA and 14:0, followed by LA, ALA, SDA, and OPA with no DHA present. OPA first appeared at the 6-h time points, later than upstream intermediate fatty acids such as LA, ALA, and SDA that appeared at the 3-h time point of the time course (Figs. 2C and S1C). The major labeled fatty acids in PLs were 14:0, 18:0, followed by OA and DHA with little LA and ALA, and no other intermediate fatty acids labeled in the time course. DHA appeared at the 3-h time point, and with the labeling time increasing, its radioactivity increased (Figs. 2D and S1D). These results indicate that OPA is synthesized in plastidic GLs through sequential desaturations: first Δ9 desaturation of 18:0 synthesized from acetic acid by fatty acid synthase, to OA, then Δ12 desaturation of OA to LA, Δ15 desaturation of LA to ALA, Δ6 desaturation of ALA to SDA, and finally Δ3 desaturation to OPA. On the other hand, DHA is probably synthesized extraplastically from acetic acid through an anaerobic pathway catalyzed by a PUFA synthase in the alga, but its synthesis from 18:0 through desaturations and elongations cannot be excluded.

Figure 2.

Labeled lipids and fatty acids in Emiliania huxleyi fed with14C-labeled acetic acid in a time course with five time points.A, TLC separation of labeled total lipids into lipid classes. B, AgNO3-TLC separation of labeled fatty acids from total lipids. C, AgNO3-TLC separation of labeled fatty acids from galactolipids (MGDG + DGDG). D, AgNO3-TLC separation of labeled fatty acids from phospholipids (PE + PC).

Figure 3.

Labeled lipids and fatty acids in Emiliania huxleyi fed with14C-labeled α-linolenic acid.A, TLC separation of total lipids into pigments, MGDG, DGDG, and PLs including PE and PC with two lane replicates. B, AgNO3-TLC separation of fatty acids from MGDG, DGDG and phospholipids (PL, dash line box).

Feeding the alga with radiolabeled α-linolenic acid

To examine whether an aerobic pathway was involved in the biosynthesis of DHA, the radiolabeled intermediate ALA at the branching point of Δ6 desaturation/Δ6 elongation and Δ9 elongation/Δ8 desaturation sub-pathways in the aerobic pathway was used to trace the biosynthetic process. As shown in Figure 3A, exogenously fed ALA was readily taken up and incorporated into lipid classes by the alga. MGDG and PE as well as pigments were among the most abundantly labeled lipid classes with DGDG and PC being labeled to a less extent. The most abundantly labeled fatty acid in MGDG was OPA, followed by SDA and ALA with little labeled saturated fatty acids. The similar pattern of labeled fatty acids was observed in DGDG, with exception of relatively low conversion efficiency from ALA to SDA and then to OPA resulting in a higher level of ALA (Figs. 3B and S2A). This result confirms that two sequential desaturations take place on fed ALA in GLs, first converting ALA to SDA by a Δ6 desaturation and then SDA to OPA by a Δ3 desaturation. On the other hand, the major labeled fatty acids in PLs were ALA, DHA and saturated fatty acids (Figs. 3B and S2A). This result implies that DHA can be synthesized from fed ALA by an aerobic pathway through desaturations and elongations. Collectively, ALA feeding results indicate that biosynthesis of OPA and DHA in E. huxleyi can go through two separate aerobic pathways from ALA. OPA is synthesized in plastidic GLs through two sequential desaturations on ALA while DHA is synthesized extraplastidically through desaturations and elongations on ALA.

Feeding the alga with radiolabeled linoleic acid

To confirm the two aerobic pathways for OPA and DHA biosynthesis concluded from the above feeding experiments, a radiolabeled upstream intermediate fatty acid LA in the pathways was fed to the alga. Similar to the ALA feeding, the major labeled lipid classes with LA feeding were MGDG, PE, and pigments with DGDG and PC labeled to a lesser extent (Fig. 4A). The most abundantly labeled fatty acid in MGDG was OPA, followed by SDA, ALA and LA with little labeled saturated fatty acids. The most strongly labeled fatty acids in DGDG were ALA and LA, followed by OPA and SDA. In PLs, LA, 18:0, and DHA were the three most abundantly labeled fatty acids, followed by ALA and other saturated fatty acids (Figs. 4B and S2B). This result indicates that DHA can be synthesized from fed LA through desaturation and elongation processes in an extraplastidic aerobic pathway. On the other hand, the biosynthesis of OPA occurs through the plastidic aerobic pathway by sequential desaturations on LA.

Figure 4.

Labeled lipids and fatty acids in Emiliania huxleyi fed with14C-labeled linoleic acid.A, TLC separation of total lipids into pigments, MGDG, DGDG, and PL including PE and PC with two lane replicates. B, AgNO3-TLC separation of fatty acids from MGDG, DGDG and phospholipids (PL, dash line box).

Feeding the alga with radiolabeled oleic acid

To confirm the biosynthesis process of OPA and DHA in E. huxleyi, a further upstream radiolabeled intermediate, oleic acid, in the pathways was fed to the alga. As shown in Figure 5A, the most strongly labeled lipid classes were MGDG and PE with some labelings found in DGDG and PC, which was similar as ALA and LA feedings. However, labeled fatty acid profiles in lipid classes were very different from previous feedings. In both MGDG and DGDG, the major labeled unsaturated fatty acids were LA, ALA, SDA and OPA besides OA, further confirming the biosynthesis of OPA by the plastidic aerobic pathway through sequential desaturations. In contrast, OA was almost a solely labeled unsaturated fatty acid in PLs with no DHA and OPA as well as any other intermediate fatty acids detected (Figs. 5B and S2C). Although a very faint LA band was observed in PLs, it likely resulted from contamination of the near DGDG band on the TLC plate due to challenges in dissecting the close bands, as the steady-state labelings of the alga with the same fatty acid failed to detect this band (see below). These results indicate that the extraplastidic aerobic pathway for the biosynthesis of DHA is incomplete with possibly missing a Δ12 desaturation step for converting OA to LA in the alga.

Figure 5.

Labeled lipids and fatty acids in Emiliania huxleyi fed with14C-labeled oleic acid. A, TLC separation of total lipids into pigments, MGDG, DGDG, and PLs including PE and PC with two-lane replicates. B, AgNO3-TLC separation of fatty acids from MGDG, DGDG and phospholipids (PL, dash line box).

To further interrogate the precursor and product relationship in the biosynthesis of OPA and DHA in the aerobic pathways, steady-state labeling of the alga grown at the optimal temperature with radiolabeled oleic acid in a 24-h time course was performed, and fatty acid profiles in GLs and PLs were analyzed by TLC. As shown in Figure 6A, the predominating labeled fatty acid in GLs was OA, followed by downstream fatty acids such as LA, ALA, SDA and OPA in the time course. SDA first appeared at the 6-h time point, and OPA started to show up at the 9-h time point in the time course. With the labeling time increasing, radioactivity of OPA increased in the lipid class. At the 24-h time point of labeling, radioactivity of OPA reached its highest in the time course (Fig. S4A). Such labeling pattern reconfirms that the biosynthesis of OPA from OA goes through a sequential process of Δ12, Δ15, Δ6 and Δ3 desaturations and all these desaturation steps take place in galactolipids. On the other hand, OA was almost a solely labeled fatty acid in PLs at all time points of the labeling course with other fatty acids including DHA and OPA being undetected (Fig. 6B), implying that OA was solely taken up and incorporated in PLs during the labeling course, and it was not used to synthesize any downstream fatty acids in the aerobic pathway including DHA. To investigate whether the labeling pattern in the alga would change under different growth conditions, especially at a lower temperature where there would increase demand for PUFAs to adapt cellular membrane fluidity, a steady-state labeling of the alga grown at 11 with radiolabeled oleic acid in a 24-h time course was thus performed. As shown in Figs. S3 and S4B, the labeling pattern was very similar to that in the alga grown at the optimal temperature (18 ). No DHA was labeled in phospholipids while ALA, SDA and OPA were labeled in galactolipids in the sequential order during the time course. These results reconfirms that the extraplastidic aerobic pathway for DHA biosynthesis is partial by missing the Δ12 desaturation step, and suggests that DHA is synthesized by an anaerobic pathway in the microalga.

Figure 6.

Labeled fatty acids from galactolipids and phospholipids in Emiliania huxleyi fed with14C-labeled oleic acid in a 24-h time course with five time points.A, AgNO3-TLC separation of fatty acids from galactolipids (MGDG + DGDG). B, AgNO3-TLC separation of fatty acids from phospholipids.

In vitro PUFA synthase assays

To further confirm that DHA was synthesized through an anaerobic pathway catalyzed by a PUFA synthase in the alga, in vitro PUFA synthase assays were performed using the crude enzymes isolated from the alga along with acetyl-CoA and 14C-labeled malonyl-CoA as substrates (15). As shown in Figure 7, DHA was produced in the in vitro assay with Emiliania crude enzymes, which was similar to that from the positive control Thraustochytrium where DHA was exclusively synthesized by the anaerobic pathway with exception of the additional production of 16:0 and eicosapentaenoic acid (DPA, 22:5n-6) in Thraustochytrium (29). No fatty acid was produced in the assay with heat deactivated crude enzyme proteins. This result confirms that DHA can be de novo synthesized from acetyl-CoA by the anaerobic pathway catalyzed by a PUFA synthase in Emiliania.

Figure 7.

Fatty acids produced by in vitro PUFA synthase assays. Fatty acids synthesized by crude enzymes with 100 μM acetyl-CoA, 500 μM malonyl-CoA (a mixture of [1-14C]-malonyl-CoA and unlabeled malonyl-CoA), 2 mM NADH and 2 mM NADPH were transmethylated into fatty acid methyl esters separated by AgNO3-TLC. Lane 1, Thraustochytrium sp. 26185 as a positive control; Lane 2, Emiliania huxleyi; Lane 3, the same as in Lane 2 with heat deactivated proteins. 22:5n-6, docosapentaenoic acid (DPA).

Discussion

Dietary ω3 PUFAs have been shown to provide many health benefits for humans and animals (30, 31, 32, 33). Microalgae are the primary producers of these fatty acids for food chains. However, how these fatty acids are synthesized in microalgae remains poorly known. This study aimed to elucidate the biosynthetic mechanisms of two nutritionally important ω3 PUFAs OPA and DHA in microalgae using a series of radioisotope tracers to chase the biosynthetic process. E. huxleyi is a unicellular marine alga species in the coccolithophore family widely found in oceans where it plays significant ecological, nutritional and geochemical roles (5, 6, 7, 8). Particularly, it can produce a high level of several ω3 PUFAs including OPA and DHA. OPA, an unusual 18C chain ω3 PUFA with potential health effects (34, 35, 36) was first reported in microalgae in 1975 (37), but its biosynthesis remains completely unknown, although some hypotheses have been proposed (17, 37, 38, 39, 40, 41). This study first used a radiolabeled acetic acid, the initial precursor of fatty acid synthesis to trace the biosynthetic process in a time course. OPA was found exclusively in GLs, particularly in MGDG, with OA, LA, ALA, SDA, and OPA present in order of the labeling course, indicating that OPA is synthesized from OA through sequential Δ12, Δ15, Δ6, and Δ3 desaturations in galactolipids in E. huxleyi. This notion was later confirmed by feeding the alga with radiolabeled intermediate fatty acids including OA, LA, and ALA. These results provide the first conclusive biochemistry evidence that the biosynthesis of OPA involves the plastidic aerobic pathway with a sequential desaturation process with the last step of Δ3 desaturation using galactolipids as substrates (Fig. 8).

Figure 8.

Biosynthetic pathways of OPA and DHA in Emiliania huxleyi. There are three pathways for PUFA biosynthesis: a complete aerobic pathway for OPA synthesis in chloroplast, a complete anaerobic pathway for DHA synthesis (PUFA synthase) in cytosol, and an incomplete aerobic pathway for DHA synthesis in ER where X indicates the possible missing step. Accession number and gene ID of the functionally characterized desaturases and elongases including chloroplast Δ15 desaturase EhN3 (PP273416) (60), Δ9 elongase (EMIHUDRAFT_433098), Δ8 desaturase (EMIHUDRAFT_216445), Δ5 desaturase (EMIHUDRAFT_443389), Δ5 elongase (EMIHUDRAFT_414244), Δ4 desaturase (EMIHUDRAFT_433467) (17).

In nature, biosynthesis of DHA occurs through both aerobic and anaerobic pathways. In bacteria and some heterotrophic eukaryotic microorganisms such as protists, DHA can be synthesized from acetic acid through an anaerobic pathway catalyzed by a PUFA synthase (15, 27, 42). In other eukaryotes, DHA is synthesized by the aerobic pathway through either a Δ4 desaturation process (14) or a retro-conversion process (43, 44, 45). In microalgae, Δ4, Δ5, Δ6 and Δ8 desaturases, and Δ6, Δ5, and Δ9 fatty acid elongases are found in the aerobic pathway, but no PUFA synthases in the anaerobic pathway have been identified (17, 46, 47, 48, 49, 50, 51, 52, 53). Therefore, the biosynthesis of DHA in microalgae is believed to go through an aerobic pathway with the last step of Δ4 desaturation. Our tracing experiments with LA and ALA labeling showed that DHA was synthesized from the fed intermediate fatty acids, implying that the aerobic pathway for DHA biosynthesis does exist in the alga. However, both pulse and steady-state labeling with OA showed that DHA was not synthesized from the fed fatty acid, implying that the aerobic pathway for DHA is incomplete missing a Δ12 desaturation step. In this pathway, OA is probably synthesized in chloroplast by a soluble acyl-ACP Δ9 desaturase. After synthesis, OA can be acylated to galactolipids for sequential desaturations to OPA in chloroplast, or move out to cytosol for the phospholipid assembly, but not for the biosynthesis of DHA (Fig. 8). A partial aerobic pathway for DHA biosynthesis has also been observed in Thraustochytrium where aerobic and anaerobic pathways coexist (27). It is believed that the aerobic pathway is a progenitor while the anaerobic pathway is newly acquired. As the anaerobic pathway is more efficient for the biosynthesis, the aerobic pathway might be only active under very specific conditions or become relic where some components get lost consequently during evolution.

Feeding the alga with acetic acid in the time course showed that DHA in PLs appeared earlier than OPA in GLs in the time course, implying that DHA is synthesized from acetic acid by the anaerobic pathway. In vitro enzymatic assays with acetyl-CoA and 14C-labeled malonyl-CoA confirm that DHA can be de novo synthesized by a PUFA synthase in the alga. Collectively these results indicate that both aerobic and anaerobic pathways coexist in E. huxleyi for the biosynthesis of DHA; however, the aerobic pathway is incomplete and the anaerobic pathway is solely responsible for DHA biosynthesis (Fig. 8).

Currently, no front-end PUFA Δ3 desaturase has been identified in any living species including algae, and no PUFA synthases have been functionally confirmed in microalgae although homologous sequences were found in alga genomes by homology search (39). Therefore, our future efforts on the biosynthesis of PUFAs in microalgae would be the identification and functional characterization of the genes for these enzymes.

Experimental procedures

Cultivation of E. huxleyi

Axenic culture of E. huxleyi strain CCMP1516 was purchased from the National Center for Marine Algae and Microbiota (NCMA), grown and maintained in L1 medium without silicate (L1-Si) from NCMA based on f/2 medium with additional trace metals (54). The algal cells were cultivated in a 500-ml Erlenmeyer flask under illumination by an LED lamp at an intensity of 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 with a light/dark cycle of 12 h/12 h at 18 . The growth of the alga was determined based on the O.D. values at 750 nm.

Lipid extraction

Total lipids were extracted by a modified Bligh & Dyer method (55). Microalga biomass was first quenched in 80 to 85 isopropanol with 0.01% (w/v) butylated hydroxytoluene (BHT) for 10 min. The total lipids were then extracted with methanol/chloroform/water (2:1:0.8, v/v/v) and mix vigorously before centrifugation at 2200 rpm for 10 min. After centrifugation, the organic phase containing total lipids was collected, dried under nitrogen gas and resuspended in an appropriate volume of chloroform. Total lipids were separated into different lipid classes including monogalactosyldiacylglycerol (MGDG), digalactosyldiacylglycerol (DGDG), phosphatidylcholine (PC) and phosphatidylethanolamine (PE) on silica gel thin layer chromatography (TLC) plates (Analtech, uniplate, 20 × 20 cm) using acetone/toluene/water (91:30:8, v/v/v) (56). After separation of total lipids, the TLC plate was air dried in fume hood for 20 min, stained with 0.005% (w/v) primulin in acetone/water (4:1, v/v) and then visualized under UV light. Individual lipid classes were identified by the comparison with standards obtained from Nu-Chek-Prep, Inc. and Sigma-Aldrich.

Fatty acid analysis by gas chromatography

Unlabeled fatty acids of Emiliania cells were analyzed by gas chromatography (GC). Total fatty acids in the biomass were transmethylated to fatty acid methyl esters (FAMEs) by 2 ml of 1% sulfuric in methanol at 80 for 2 h. After that, the samples were cooled down on ice and then added with 1 ml 0.9% NaCl and 2 ml hexane. After brief centrifugation, the hexane phase containing FAMEs was transferred to a new tube and dried under N2 gas. After drying, the sample was re-suspended in an appropriate amount of hexane and used for GC analysis on an Agilent 7890A system with a DB-23 column. The peaks shown on the GC chromatogram were identified by comparison with standards (Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA) (57).

Feeding of radiolabeled tracers and analysis of labeled lipids

Algae cultures were first grown under a 12 h/12 h light/dark cycle with a light intensity of 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 at 18 until it reached OD750 at around 0.3, then algae cells were sub-cultured by inoculating 20 ml of the culture into 180 ml of fresh medium. When the culture reached to the log phase, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 3000 rpm at 18 for 5 min and re-suspended in 200 ml of fresh Li-Si medium. The cultures were then incubated at 18 for 1 h for equilibration before adding radioisotope tracers for labeling. For steady-state labeling of acetic acid, 50 μCi of [1-14C]-labeled sodium acetate (PerkinElmer; specific activity, 50.5 mCi/mmol) was added to a 200 ml culture. At the time points of 3 h (3h), 6 h (6h), 9 h (9h), 12 h (12h), and 24 h (24h) of feeding, 40 ml of culture at each time point was harvested and used for lipid analysis. For steady-state labeling by oleic acid, the same procedure was used with 50 μCi of [1-14C]-oleic acid (American Radiolabeled Chemicals; specific activity, 55 mCi/mmol) was added to 200 ml Emiliania culture. At the time points of 3h, 6h, 9h, 12h, and 24h of feeding, total lipids were extracted from the culture samples and used for lipid class and fatty acid composition analysis.

To trace the aerobic biosynthetic pathways of PUFAs produced by E. huxleyi, 14C-labeled intermediate fatty acids including 25 μCi of [1-14C]-oleic acid (American Radiolabeled Chemicals; specific activity, 55 mCi/mmol), 25 μCi of [1-14C]-linoleic acid (American Radiolabeled Chemicals; specific activity, 55 mCi/mmol) and 25 μCi of [1-14C]-α-linolenic acid (American Radiolabeled Chemicals; specific activity, 55 mCi/mmol) were individually fed to 100 ml Emiliania culture at the log phase for 24 h. Then, total lipids were extracted from the cell pellet and separated on a TLC plate as indicated above. Each lipid class was eluted from the TLC plate and directly transmethylated with 2 ml of 1% sulfuric in methanol at 80 for 2 h for FAMEs analysis. FAMEs, as prepared above, were loaded onto EMD Millipore plates treated in 10% (w/v) silver nitrate in acetonitrile and baked at 110 for 15 min before use. The FAMEs were separated on AgNO3-TLC plates developed by toluene/acetonitrile (97:3, v/v) (58). After development, the TLC plates were air-dried and stained briefly with iodine vapor for visualization. For radioactive imaging capture, TLC plate was exposed to phosphor imaging screen (Amersham Biosciences) overnight and scanned by a Typhoon FLA 7000 phosphor imager (GE Healthcare Life Sciences). Identity of fatty acids were determined by comparison with radiolabeled and cold fatty acid standards. For quantitative analysis of radioactivity of lipids and fatty acids, lipid classes eluted from TLC plate with chloroform/methanol/water (50:50:10, v/v/v) and the FAMEs extracted from AgNO3-TLC plate with hexane/isopropanol/water (60:40:5, v/v/v) were counted by a liquid scintillation analyzer (Tri-carb 2910 TR, PerkinElmer, Waltham, MA, United States). The radioactivity was presented in the form of disintegration per minute (DPM) (59).

In vitro PUFA synthase assays

Emiliania culture was first grown under illumination by an LED lamp at an intensity of 100 μmol photons m−2 s−1 with a light/dark cycle of 12 h/12 h at 18 until it reached about to the log phase (OD750 at ∼0.3). Emiliania cell pellets from 100 ml cell culture were harvested by centrifugation, instantly frozen with liquid nitrogen, ground to a fine powder with pre-chilled mortar and pestle, and then transferred to a 2 ml Eppendorf tube containing 1 ml homogenization buffer (100 mM phosphate buffer with 2 mM dithiothreitol, 2 mM EDTA and 10% (v/v) glycerol). After vortexing, the mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4 for 15 min and the supernatant containing the crude protein was collected for in vitro enzymatic assays. The crude protein of Thraustochytrium sp. 26185 was prepared as described previously (29) and used as a positive control. Thraustochytrium was cultured with shaking in the GY medium consisting of 1% (w/v) yeast extract, 3% (w/v) D-glucose, and 1.75% (w/v) artificial sea salts (Sigma) at 25 until the culture reached to the log phase (OD600 at ∼0.8). The cell pellets from 5 ml cell culture were centrifuged and resuspended in 1 ml homogenization buffer with 0.5 ml of 0.5 mm glass beads (BioSpec). Thraustochytrium cells were disrupted using a Mini-Beadbeater-16 (BioSpec) for 2 min with a 1-min ice incubation every 30 s of agitation and centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4 for 15 min. The supernatant containing the total proteins was collected and used for enzymatic assay. Radioactive PUFA synthase assays were conducted in a 200 μl total reaction volume. Both reactions were initiated by adding 160 μl algal and Thraustochytrium lysate to a homogenization buffer containing 100 μM acetyl-CoA, 500 μM malonyl-CoA (a mixture of 0.2 μCi, 20 μM [1-14C]-malonyl-CoA (PerkinElmer; specific activity, 51 mCi/mmol) and 480 μM unlabeled malonyl-CoA), 2 mM NADH and 2 mM NADPH. Enzyme assay with Thraustochytrium crude protein was incubated at 25 for 1 h, and enzyme assay with Emiliania crude protein was incubated at 20 for 2 h. The reaction was terminated by adding 500 μl 85 isopropanol with 0.01% (w/v) BHT, followed by lipid extraction as described above. The organic layer containing total lipids was directly transmethylated into FAMEs and analyzed by AgNO3-TLC as described above.

Data availability

All datasets generated for this study were included in the manuscript and/or the supplementary files.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

X. Q. and D. M. writing–review & editing; X. Q. and D. M. supervision; X. Q. and D. M. resources; X. Q. project administration; X. Q. funding acquisition; X. Q. conceptualization. D. M. and K. S. methodology; K. S. writing–original draft; K. S. visualization; K. S. validation; K. S. investigation; K. S. formal analysis; K. S. data curation.

Funding and additional information

This research was supported by Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by George M. Carman

Supporting information

References

- 1.Anto S., Mukherjee S.S., Muthappa R., Mathimani T., Deviram G., Kumar S.S., et al. Algae as green energy reserve: technological outlook on biofuel production. Chemosphere. 2020;242 doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2019.125079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hu Q., Sommerfeld M., Jarvis E., Ghirardi M., Posewitz M., Seibert M., et al. Microalgal triacylglycerols as feedstocks for biofuel production: perspectives and advances. Plant J. 2008;54:621–639. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-313X.2008.03492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guschina I.A., Harwood J.L. Lipids and lipid metabolism in eukaryotic algae. Prog. Lipid Res. 2006;45:160–186. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2006.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Li-Beisson Y., Thelen J.J., Fedosejevs E., Harwood J.L. The lipid biochemistry of eukaryotic algae. Prog. Lipid Res. 2019;74:31–68. doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2019.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hallegraeff G.M., McMinn A. Coccolithophores: from molecular processes to global impact. J. Phycol. 2005;41:1065–1066. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Paasche E. A review of the coccolithophorid emiliania huxleyi (prymnesiophyceae), with particular reference to growth, coccolith formation, and calcification-photosynthesis interactions. Phycologia. 2001;40:503–529. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rost B., Riebesell U. Coccolithophores. Springer; Berlin, Heidelberg: 2004. Coccolithophores and the biological pump: responses to environmental changes. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holligan P.M., Viollier M., Harbour D.S., Camus P., Champagne-Philippe M. Satellite and ship studies of coccolithophore production along a continental shelf edge. Nature. 1983;304:339–342. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Leblond J.D., Chapman P.J. Lipid class distribution of highly unsaturated long chain fatty acids in marine dinoflagellates. J. Phycology. 2000;26:1103–1108. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bell M.V., Pond D. Lipid composition during growth of motile and coccolith forms of Emiliania huxleyi. Phytochemistry. 1996;41:465–471. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Okuyama H., Kogame K., Takeda S. Phylogenetic significance of the limited distribution of octadecapentaenoic acid in prymnesiophytes and photosynthetic dinoflagellates. Proc. NIPR Symp. Polar Biol. 1993;6:21–26. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Qiu X. Biosynthesis of docosahexaenoic acid (DHA, 22:6-4, 7,10,13,16,19): two distinct pathways. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2003;68:181–186. doi: 10.1016/s0952-3278(02)00268-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Qiu X., Xie X., Meesapyodsuk D. Molecular mechanisms for biosynthesis and assembly of nutritionally important very long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in microorganisms. Prog. Lipid Res. 2020;79 doi: 10.1016/j.plipres.2020.101047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Qiu X., Hong H., MacKenzie S.L. Identification of a Δ4 fatty acid desaturase from Thraustochytrium sp. involved in the biosynthesis of Docosahexanoic acid by heterologous expression in Saccharomyces cerevisiae and Brassica juncea. J. Biol. Chem. 2001;276:31561–31566. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102971200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Metz J.G., Roessler P., Facciotti D., Levering C., Dittrich F., Lassner M., et al. Production of polyunsaturated fatty acids by polyketide synthases in both prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Science. 2001;293:290–293. doi: 10.1126/science.1059593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Qi B., Beaudoin F., Fraser T., Stobart A.K., Napier J.A., Lazarus C.M. Identification of a cDNA encoding a novel C18-Δ9 polyunsaturated fatty acid-specific elongating activity from the docosahexaenoic acid (DHA)-producing microalga, Isochrysis galbana. FEBS Lett. 2002;510:159–165. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(01)03247-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sayanova O., Haslam R.P., Calerón M.V., López N.R., Worthy C., Rooks P., et al. Identification and functional characterisation of genes encoding the omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthetic pathway from the coccolithophore Emiliania huxleyi. Phytochemistry. 2011;72:594–600. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2011.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhou X.R., Robert S.S., Petrie J.R., Frampton D.M.F., Mansour M.P., Blackburn S.I., et al. Isolation and characterization of genes from the marine microalga Pavlova salina encoding three front-end desaturases involved in docosahexaenoic acid biosynthesis. Phytochemistry. 2007;68:785–796. doi: 10.1016/j.phytochem.2006.12.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Orikasa Y., Tanaka M., Sugihara S., Hori R., Nishida T., Ueno A., et al. PfaB products determine the molecular species produced in bacterial polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 2009;295:170–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2009.01582.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lippmeier J.C., Crawford K.S., Owen C.B., Rivas A.A., Metz J.G., Apt K.E. Characterization of both polyunsaturated fatty acid biosynthetic pathways in schizochytrium sp. Lipids. 2009;44:621–630. doi: 10.1007/s11745-009-3311-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu Z., Zang X., Cao X., Wang Z., Liu C., Sun D., et al. Cloning of the pks3 gene of Aurantiochytrium limacinum and functional study of the 3-ketoacyl-ACP reductase and dehydratase enzyme domains. PLoS One. 2018;13 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0208853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shulse C.N., Allen E.E. Widespread occurrence of secondary lipid biosynthesis potential in microbial lineages. PLoS One. 2011;6 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0020146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tanaka M., Ueno A., Kawasaki K., Yumoto I., Ohgiya S., Hoshino T., et al. Isolation of clustered genes that are notably homologous to the eicosapentaenoic acid biosynthesis gene cluster from the docosahexaenoic acid-producing bacterium Vibrio marinus strain MP-1. Biotechnol. Lett. 1999;21:939–945. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orikasa Y., Nishida T., Yamada A., Yu R., Watanabe K., Hase A., et al. Recombinant production of docosahexaenoic acid in a polyketide biosynthesis mode in Escherichia coli. Biotechnol. Lett. 2006;28:1841–1847. doi: 10.1007/s10529-006-9168-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Okuyama H., Orikasa Y., Nishida T., Watanabe K., Morita N. Bacterial genes responsible for the biosynthesis of eicosapentaenoic and docosahexaenoic acids and their heterologous expression. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2007;73:665–670. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02270-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allen E.E., Bartlett D.H. Structure and regulation of the omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid synthase genes from the deep-sea bacterium Photobacterium profundum strain SS9. Microbiology (N Y) 2002;148:1903–1913. doi: 10.1099/00221287-148-6-1903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Meesapyodsuk D., Qiu X. Biosynthetic mechanism of very long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in Thraustochytrium sp. 26185. J. Lipid Res. 2016;57:1854–1864. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M070136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ujihara T., Nagano M., Wada H., Mitsuhashi S. Identification of a novel type of polyunsaturated fatty acid synthase involved in arachidonic acid biosynthesis. FEBS Lett. 2014;588:4032–4036. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao X., Qiu X. Analysis of the biosynthetic process of fatty acids in Thraustochytrium. Biochimie. 2018;144:108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2017.10.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Niemoller T.D., Bazan N.G. Docosahexaenoic acid neurolipidomics. Prostaglandins Other Lipid Mediat. 2010;91:85–89. doi: 10.1016/j.prostaglandins.2009.09.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sprecher H. Metabolism of highly unsaturated n-3 and n-6 fatty acids. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Mol. Cell Biol. Lipids. 2000;1486:219–231. doi: 10.1016/s1388-1981(00)00077-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Crawford M.A., Costeloe K., Ghebremeskel K., Phylactos A., Skirvin L., Stacey F. Are deficits of arachidonic and docosahexaenoic acids responsible for the neural and vascular complications of preterm babies? Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1997;66:1032S–1041S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/66.4.1032S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Brash A.R. Arachidonic acid as a bioactive molecule. J. Clin. Invest. 2001;107:1339–1345. doi: 10.1172/JCI13210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mayzaud P., Eaton C.A., Ackman R.G. The occurrence and distribution of octadecapentaenoic acid in a natural plankton population. A possible food chain index. Lipids. 1976;11:858–862. doi: 10.1007/BF02532993. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fossat B., Porthé-Nibelle J., Sola F., Masoni A., Gentien P., Bodennec G. Toxicity of fatty acid 18:5n3 from Gymnodinium cf. mikimotoi: II. Intracellular pH and K+ uptake in isolated trout hepatocytes. J. Appl. Toxicol. 1999;19:275–278. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1263(199907/08)19:4<275::aid-jat578>3.0.co;2-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sola F., Masoni A., Fossat B., Porthé-Nibelle J., Gentien P., Bodennec G. Toxicity of fatty acid 18:5n3 from Gymnodinium cf. mikimotoi: I. morphological and biochemical aspects on Dicentrarchus labrax gills and intestine. J. Appl. Toxicol. 1999;19:279–284. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1099-1263(199907/08)19:4<279::aid-jat579>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Joseph J.D. Identification of 3, 6, 9, 12, 15-octadecapentaenoic acid in laboratory-cultured photosynthetic dinoflagellates. Lipids. 1975;10:395–403. doi: 10.1007/BF02532443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jónasdóttir S.H. Fatty acid profiles and production in marine phytoplankton. Mar. Drugs. 2019;17:151. doi: 10.3390/md17030151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chen B., Wang F., Xie X., Liu H., Liu D., Ma L., et al. Functional analysis of the dehydratase domains of the PUFA synthase from Emiliania huxleyi in Escherichia coli and Arabidopsis thaliana. Biotechnol. Biofuels Bioproducts. 2022;15:123. doi: 10.1186/s13068-022-02223-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sasso S., Pohnert G., Lohr M., Mittag M., Hertweck C. Microalgae in the postgenomic era: a blooming reservoir for new natural products. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2012;36:761–785. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2011.00304.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ishikawa T., Domergue F., Amato A., Corellou F. Characterization of Unique eukaryotic sphingolipids with temperature-dependent Δ8-Unsaturation from the picoalga Ostreococcus tauri. Plant Cell Physiol. 2024;pcae007:1–18. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcae007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Matsuda T., Sakaguchi K., Hamaguchi R., Kobayashi T., Abe E., Hama Y., et al. Analysis of Delta12-fatty acid desaturase function revealed that two distinct pathways are active for the synthesis of PUFAs in T. aureum ATCC 34304. J. Lipid Res. 2012;53:1210–1222. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M024935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Bazinet R.P., Layé S. Polyunsaturated fatty acids and their metabolites in brain function and disease. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2014;15:771–785. doi: 10.1038/nrn3820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Uauy R., Mena P., Rojas C. Essential fatty acids in early life: structural and functional role. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2000;59:3–15. doi: 10.1017/s0029665100000021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sprecher H. The roles of anabolic and catabolic reactions in the synthesis and recycling of polyunsaturated fatty acids. Prostaglandins Leukot. Essent. Fatty Acids. 2002;67:79–83. doi: 10.1054/plef.2002.0402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Degraeve-Guilbault C., Gomez R.E., Lemoigne C., Pankansem N., Morin S., Tuphile K., et al. Plastidic D6 fatty-acid desaturases with distinctive substrate specificity regulate the pool of C18-PUFAs in the ancestral picoalga ostreococcus tauri1. Plant Physiol. 2020;184:82–96. doi: 10.1104/pp.20.00281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Domergue F., Lerchl J., Zähringer U., Heinz E. Cloning and functional characterization of phaeodactylum tricornutum front-end desaturases involved in eicosapentaenoic acid biosynthesis. Eur. J. Biochem. 2002;269:4105–4113. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1033.2002.03104.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hoffmann M., Wagner M., Abbadi A., Fulda M., Feussner I. Metabolic engineering of ω3-very long chain polyunsaturated fatty acid production by an exclusively acyl-CoA-dependent pathway. J. Biol. Chem. 2008;283:22352–22362. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802377200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Iskandarov U., Khozin-Goldberg I., Ofir R., Cohen Z. Cloning and characterization of the δ6 polyunsaturated fatty acid elongase from the green microalga parietochloris incisa. Lipids. 2009;44:545–554. doi: 10.1007/s11745-009-3301-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pereira S.L., Leonard A.E., Huang Y.S., Chuang L. Te, Mukerji P. Identification of two novel microalgal enzymes involved in the conversion of the ω3-fatty acid, eicosapentaenoic acid, into docosahexaenoic acid. Biochem. J. 2004;384:357–366. doi: 10.1042/BJ20040970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Tonon T., Sayanova O., Michaelson L.V., Qing R., Harvey D., Larson T.R., et al. Fatty acid desaturases from the microalga Thalassiosira pseudonana. FEBS J. 2005;272:3401–3412. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.04755.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Domergue F., Abbadi A., Zähringer U., Moreau H., Heinz E. In vivo characterization of the first acyl-CoA Δ6- desaturase from a member of the plant kingdom, the microalga Ostreococcus tauri. Biochem. J. 2005;389:483–490. doi: 10.1042/BJ20050111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petrie J.R., Shrestha P., Mansour M.P., Nichols P.D., Liu Q., Singh S.P. Metabolic engineering of omega-3 long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids in plants using an acyl-CoA Δ6-desaturase with ω3-preference from the marine microalga Micromonas pusilla. Metab. Eng. 2010;12:233–240. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2009.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Guillard R.R., Ryther J.H. Studies of marine planktonic diatoms. I. Cyclotella nana Hustedt, and Detonula confervacea (cleve) Gran. Can. J. Microbiol. 1962;8:229–239. doi: 10.1139/m62-029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bligh E.G., Dyer W.J. A rapid method of total lipid extraction and purification. Can J. Biochem. Physiol. 1959;37:911–917. doi: 10.1139/o59-099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Wang Z., Benning C. Arabidopsis thaliana polar glycerolipid profiling by thin layer chromatography (TLC) coupled with gas-liquid chromatography (GLC) J. Vis. Exp. 2011;49:2518. doi: 10.3791/2518. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Xie X., Sun K., Meesapyodsuk D., Miao Y., Qiu X. Distinct functions of two FabA-like dehydratase domains of polyunsaturated fatty acid synthase in the biosynthesis of very long-chain polyunsaturated fatty acids. Environ. Microbiol. 2020;22:3772–3783. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.15149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Wilson R., Sargent J.R. High-resolution separation of polyunsaturated fatty acids by argentation thin-layer chromatography. J. Chromatogr. A. 1992;623:403–407. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Zhao X., Qiu X. Very long chain polyunsaturated fatty acids accumulated in triacylglycerol are channeled from phosphatidylcholine in Thraustochytrium. Front Microbiol. 2019;10 doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00645. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Sun K., Meesapyodsuk D., Qiu X. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of a plastidial ω3 desaturase from Emiliania huxleyi. Front. Microbiol. 2024;15:1–11. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2024.1381097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study were included in the manuscript and/or the supplementary files.