Abstract

Introduction and Objectives:

La Clínica Latina is a free clinic that strives to meet the healthcare needs of the Spanish-speaking population of Franklin County, Ohio, including metropolitan Columbus. As a student-run free clinic, care is provided each week by volunteer medical students and resident physicians under the administrative leadership of the medical student board and clinical supervision of licensed physicians. Patients served by the clinic have a multitude of chronic health conditions, which are managed by clinic volunteers through the delivery of over 1500 appointments per year. In order to better serve the rapidly growing patient population, this study describes the delivery and results of an assessment aimed at understanding the needs that are being met sufficiently at the clinic and what pitfalls still exist in the clinic’s provision of care.

Methods:

By delivering a survey inquiring about the experiences of patients at La Clínica Latina, clinic workflow can be optimized for the provision of patient-centered care.

Results:

Insights collected from a convenience sample of 30 patients demonstrate mobile phone use as the primary mode of communication with clinic volunteers, previously under-appreciated musculoskeletal health concerns, longer than desired wait times after check-in, and variable experiences of health literacy by patient gender.

Conclusion:

By addressing each of these insights in updates to clinic workflow, La Clínica Latina may prove to become an even more useful resource to the region’s growing Hispanic population.

Keywords: student-run free clinic, needs assessment, survey, Spanish-speaking clinic

Background

La Clínica Latina (LCL) is a free clinic that primarily serves Spanish-speaking patients of Franklin County, Ohio, including metropolitan Columbus. As a weekly student-run free clinic, care is provided by volunteer medical students and resident physicians under the administrative leadership of the medical student board and clinical supervision of licensed physicians. The clinic provides free healthcare regardless of language, race, age, insurance status, immigration status, or income with the overall mission of alleviating health disparities imposed by social determinants of health impacting the Spanish-speaking population of the area. At LCL, patients are seen for any reason they would be seen at a primary care office. Patients most commonly present for annual well-visits and for management of diabetes and hypertension as well as specialty visits including gynecology, neurology, pediatrics, and musculoskeletal on specialty nights when clinical teams are available. An in-house lab offers patient lab testing and a pharmacy is stocked with several commonly prescribed medications. For patients who require more specialized or advanced care, referrals are made to the institution’s medical center. Other patient needs are addressed by providing community resources. During 2023, approximately 30 visits were conducted each night, totaling 1577 visits, including 380 via telehealth, 69 women’s health focused visits, and 56 pediatric visits. These numbers demonstrate the vast community impact that LCL has throughout the region.

As a note for this work, the terms “Hispanic” and “Latino” are pan-ethnic terms—“Hispanic” has more to do with language spoken (Spanish) and “Latino” is associated with geography, origin, or descent tied to Latin America. For clarity in this paper, “Latino” will be used to describe our patient population so that terms like “Hispanic,” “Latinx,” “Latin@” may also be applicable.

The Latino population in the United States faces many challenges to accessing healthcare, often made worse by a language barrier. 1 In addition, many other variables contribute to the higher disease burden faced by the U.S. Latino population when compared to non-Hispanic Whites, include cultural barriers, immigration status, and higher rates of being uninsured. 2 Specific to the population that La Clínica Latina serves, historical data from the Columbus, Ohio Department of Public Health has reported that Latino adults have about a 70% higher risk of having their activities limited due to poor physical or mental health and about a 70% higher risk of being uninsured. 3 Latinos comprise about 7% of the population of Franklin County and every single one of Ohio’s 88 counties has seen an increase in its Latino population over the last decade, with the most significant growth occurring in rural communities. 4 The barriers to sufficient care and healthy lifestyle practices that impact the growing Latino population in the U.S. necessitate the existence of free clinics such as La Clínica Latina.

Prior research has demonstrated the effectiveness of student-run free clinics in addressing the needs of underserved populations such as that of LCL. 5 One such example is the work done at LCL to improve the quality of diabetes care provided to chronic care patients in the clinic, which has resulted in rates of screening and preventive care uptake (ie, A1C monitoring, diabetic foot exams) that are on par with or surpass national averages. 6 This finding is not unique, as another study focusing on low-density lipoprotein levels in the patients of a Spanish-speaking student-run free clinic demonstrated improved control of hyperlipidemia as compared to national averages. 7 While the potential for positive impact of student-run free clinics is clear, it is essential that each individual clinic seeks to meet the ongoing unmet needs of their specific patient population. In order to better assess those of patients at LCL, clinic administrators and volunteers have conducted a rudimentary needs assessment with the principal aim of assessing the needs that are being met sufficiently at the clinic and any pitfalls that may still exist in the clinic’s care of the patient population. By understanding where services have room for improvement, La Clínica Latina may continue to work to improve patient health outcomes by modifying current clinic environment and practices.

Methods

This study was deemed exempt by The Ohio State University Institutional Review Board. In order to conduct the needs assessment, a cross-sectional study design was employed using a 1-time survey administered to a convenience sample of 30 patients in the waiting room of La Clínica Latina over the course of 4 weeks by trained project team members. Survey questions (Figures 1 and 2) were designed by the clinic medical and administrative teams based on prior assessments of clinic operations and patient needs, thus providing face validity to the items as they encompassed considerations relevant to LCL and clinic patients. Health literacy questions were adapted and translated versions of previously validated measures described by Chew et al. 8

Figure 1.

Spanish version of needs assessment survey administered to patients.

Figure 2.

English version of needs assessment survey administered to patients.

Surveys were collected from consenting patients waiting for their appointment who had previously had at least 2 prior appointments at LCL. Each participant was administered a questionnaire, consisting of questions regarding both positive and unsatisfactory aspects of patients’ experience at the clinic. Each of these categories includes a subjective, open ended question to elicit patient opinions about what they most enjoy about their experience at LCL and what could be improved based on their experience. Patients were provided with a paper copy of the questionnaire and offered the opportunity to be read the survey aloud by a volunteer. Most patients opted to have the survey orally delivered. Regardless of whether the survey was being read aloud, the project member remained with the patient completing the questionnaire to provide necessary clarification. Paper copies of survey responses were then recorded in a digital Qualtrics survey for maintenance and analysis.

Analysis of the deidentified data included aggregating and performing basic descriptive statistics and creating bar graphs using SPSS and the Microsoft Excel t-test function in order to better understand our patient population as a whole and what their needs are. The subjective responses were coded and assigned themes based on shared content. For example, one category for the question “What do you dislike most about clinic?” was “wait time.” Any comment that was written that had to do with wait time was included in this category. No responses were ambiguous and they all fit cleanly into a category.

Patient privacy was maintained by not collecting any identifiable medical information, conducting the survey anonymously, and electronically recording results in a deidentified manner. Furthermore, paper survey responses remain compiled in a secure location.

Results

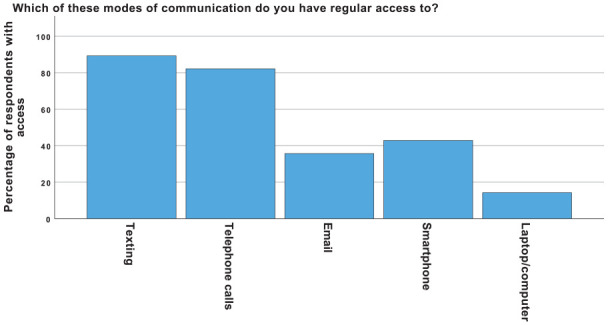

Over the course of 4 weeks at La Clínica Latina, survey responses were collected from 30 patients. In order to understand how the clinic may improve patient communications, the survey asked about forms of communication that respondents had access to. The majority of respondents reported having regular access to texting and telephone calls (Figure 3). Conversely, less than half of respondents had regular access to email, a smartphone, or a laptop/computer.

Figure 3.

Percentage of respondents with access to select modes of communication.

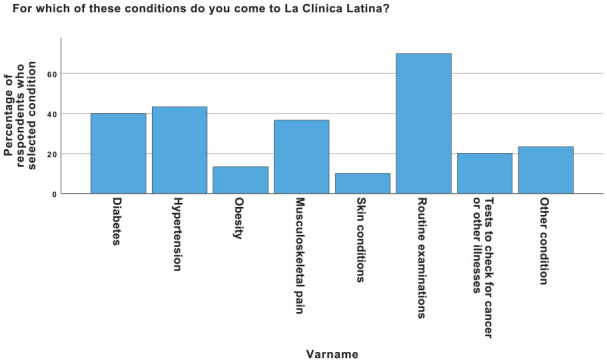

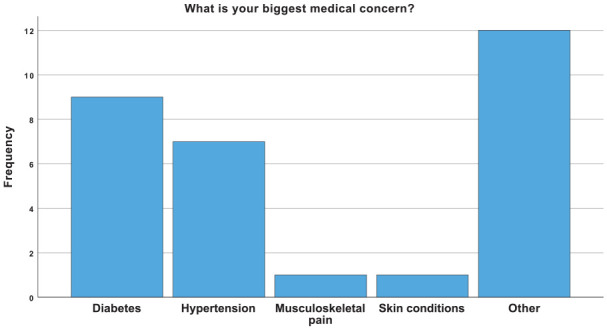

The next set of questions focused on patient health concerns. Respondents were asked to indicate any medical conditions for which they come to La Clínica Latina for treatment. Options based on clinic data were provided in a multiple choice list of common conditions including diabetes, hypertension, obesity, musculoskeletal pain, skin conditions, routine examination, testing, or other. Among these choices, the most common condition indicated was “routine examinations” followed by “hypertension” “diabetes” and “musculoskeletal pain.” (Figure 4) Distribution of participant responses changed significantly when asked to indicate their single biggest medical concern, rather than all conditions that they were seen for at LCL. Diabetes (n = 9) was the biggest medical concern reported by most patients, followed by hypertension (n = 7; Figure 5). Each of these options though was less prominent than the “Other” category (n = 14). When prompted to expounded on this selection, respondents indicated cancer-related (n = 3), thyroid-related (n = 3), and other specific concerns written in by only 1 respondent each.

Figure 4.

Frequency of conditions for which respondents sought care at La Clínica Latina.

Figure 5.

Frequency of biggest medical concerns indicated by survey respondents.

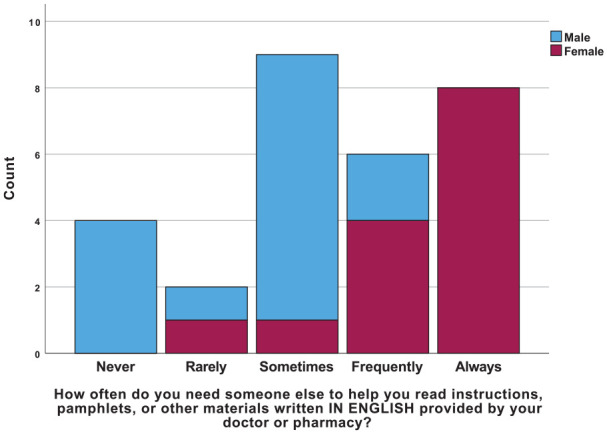

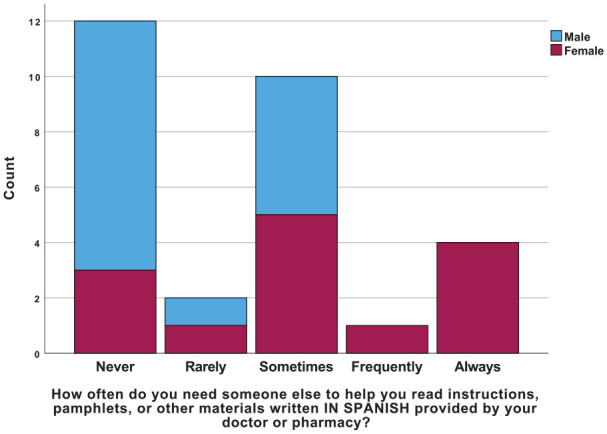

The third set of questions analyzed from the survey focused on patient health literacy, both in English and Spanish (Figures 6 & 7). When asked how often respondents required help reading medical instructions or information written in English, around half indicated “frequently” or “always,” while only 16.7% “frequently” or “always” needed help with medical instructions or information written in Spanish. Interestingly, a gender-based difference was observed in the distribution of results to these health literacy questions with women reporting needing help more often than men.

Figure 6.

Number of respondents indicating varying frequencies of need for assistance with reading health materials in English.

Figure 7.

Number of respondents indicating varying frequencies of need for assistance with reading health materials in Spanish.

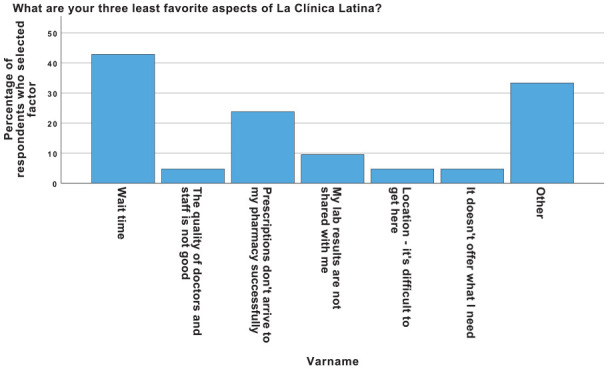

The next question sought to discern aspects of clinic that participants valued and those that were less appreciated. When asked to select the 3 most disliked aspects of La Clínica Latina from among a list of known shortcomings of the clinic, the most common selection was “wait time,” followed by “prescriptions don’t arrive to my pharmacy successfully” (Figure 8). Notably, most respondents indicated fewer than 3 disliked aspects.

Figure 8.

Percentage of respondents’ indication of select least favorite aspects of La Clínica Latina.

At the end of the survey, participants were provided with two open-ended questions intended to provide space for any attitudes that had not been elicited in the multiple choice-style questions throughout the rest of the survey. The first question prompted participants to describe the aspect of La Clínica Latina that they enjoyed the most. Responses to this question were categorized into themes, primarily consisting of quality of care, delivery of care in Spanish, and care being free of cost (Table 1). Conversely, when asked what aspect of LCL participants disliked the most, 23% reported the wait times, 13% reported issues with prescriptions, 10% reported lack of dentistry, 7% reported poor quality of care, 7% reported poor clinic space/environment, 7% reported accessibility issues, 3% reported scheduling and communication difficulties, 3% reported lapses in specialty care, and 27% reported that nothing could be improved.

Table 1.

Themes of Participant Responses Regarding Favorite Elements of La Clínica Latina.

| Theme | Rate of response (%) | Translated sample quotes |

|---|---|---|

| Quality of care | 50 | “The staff are just so friendly and they invest so much of their time to get to understand our health.” |

| “The attention and care that they provide is what I like most about Clinica Latina. I appreciate the assistance they give to our community, and the staff are so enthusiastic.” | ||

| Care delivered in Spanish | 23 | “Having medical attention in my language is incredible” |

| “I like that I can finally understand medical professionals because at last they speak my language. My only reservation is that I wish they could extend this service to more people and increase their availability.” | ||

| Free of cost | 10 | “I like that there is a service for those who don’t have access to medical insurance” |

| Location | 3 | N/A |

| Everything | 3 | N/A |

| No answer | 10 | N/A |

Discussion

The results of this needs assessment disclose a variety of shared demographics and attitudes that may allow La Clínica Latina to better serve the current patient population. When considering expansion approaches for meeting the needs of clinic patients, it is important to base efforts on known concerns in the community. As anticipated,9,10 diabetes and hypertension were respondents’ most prevalent “main” health concerns. More surprisingly, the data showed that when respondents were asked to indicate all of their health concerns via a multiple choice question, musculoskeletal pain was almost as prevalent as diabetes and hypertension. It had not previously been appreciated that so many of La Clínica Latina’s patients were suffering from musculoskeletal pain, and that it should be a priority in the development of future specialty clinic nights.

An additional key finding of interest from the survey was that wait time, or time spent in the waiting room before a volunteer is ready to see a patient, was the most disliked aspect of patient experience at La Clínica Latina, and that, overall, respondents were satisfied with other aspects like staff quality and laboratory test experience. This area of improvement is essential to address in the clinic as excessive wait time may lead to avoidance of accessing care. 11 Thus, for future patient experience initiatives, a focus should be placed on reducing wait time in an effort to alleviate it as a possible barrier to care.

Outside the clinic walls, it was also a goal of the survey to understand how to best reach patients and improve uptake of clinic services. In terms of the communications data, most respondents had regular access to texting and telephone calls, while few had regular access to email, smartphones, or laptops/computers. These data demonstrate an area of possible concern as our patients experience increased disparities due to the digital divide. 12 Lack of access to digital health resources or conduits for delivering telehealth care may have negative impacts on patient outcomes which should continuously be assessed by clinic administration. These data also support LCL’s current means of communication with patients primarily through call and text and oppose the implementation of any kind of scheduling or electronic chart system that requires email, smartphones, or computer access, all of which are initiatives that have been considered in the past at LCL.

In addition to disparities resulting from technological barriers, data from this assessment revealed new and previously appreciated gaps in health literacy. Overall, respondents unsurprisingly reported much higher health literacy in Spanish than in English, showing the ongoing importance of La Clínica Latina’s Spanish language services. Less expected was the finding that women reported needing more help understanding medical instructions or information in either language than men did. Many factors could underlie this, including gendered differences in educational attainment and the role of gender in likelihood of help-seeking behaviors. 13

While the aforementioned insights provided guidance on future areas for growth for LCL, participant responses also provided positive feedback, such as those included in Table 1, indicating the benefit experienced by the sample of patients who completed the survey. Most respondents report their health conditions as having improved since starting to receive care at La Clínica Latina, with far fewer reporting their health conditions as staying the same, and even less reporting their health conditions as having worsened.

This study includes a few limitations worthy of note, including lack of clarity of questions, small sample size, and desirability bias as surveys were orally delivered to most participants.

Conclusion

When providing a service to a community subjected to health inequities, it is of utmost importance to assure that those services are specifically tailored to their needs. This was the motivation behind this survey-based needs assessment of the patients at La Clínica Latina. By collecting and assessing patient attitudes, this study sought to identify areas for tailoring the continued improvement of the patient experience at LCL. Through the collection of 30 responses, significant needs to be addressed in clinic workflow regarding wait time, digital communications, and health literacy were identified. Additionally, flaws in survey design were identified through analysis, which will continue to inform the design and dissemination of future clinic surveys. Despite these shortcomings, this study has provided insights that will guide the development of process improvement at La Clínica Latina.

Prior to the execution of this study, patient wait time had long been a salient concern among clinic administrators. Anecdotally, patients at LCL have been known to wait up to an hour and a half for their appointment despite having a predetermined appointment time. This outcome is attributed to many factors, namely challenges with staffing licensed clinicians who oversee medical student volunteers. In spite of these challenges, patient survey feedback provides further motivation to address this shortcoming in patient care. Accessing healthcare shouldn’t monopolize patient time or resources, especially in light of the transportation and work hour limitations experienced by many of LCL’s patients.

Serving a Spanish-speaking patient population comes with unique challenges in health literacy. 14 These circumstances make communication of utmost importance. The data from our survey suggest that patients are most accessible by texting and phone call. While presently not the primary method, the former of these means of communication may be an optimal route for exploring more patient-friendly clinic communications, including scheduling. As demonstrated by the survey data, communications become further challenging when pertaining to health information. While there may be differences in literacy among patients at LCL based on gender, operating under the assumption that all patients could benefit from clear Spanish or English health communications is the safest way to assure equitable and satisfactory outcomes for all patients. 15

With these considerations in mind, La Clínica Latina aims to incorporate real patient data into its future workflow for the improvement of patient experience and ultimately outcomes. By sharing these data broadly, this study may serve as an example for similar student-run free clinics to seek out patient feedback and strive to provide the most tailored care possible.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding: The author(s) received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

ORCID iD: Nicole M. Clark  https://orcid.org/0009-0000-3837-7768

https://orcid.org/0009-0000-3837-7768

References

- 1. Escobedo LE, Cervantes L, Havranek E. Barriers in healthcare for Latinx patients with limited English proficiency: a narrative review. J Gen Intern Med. 2023;38(5):1264-1271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Velasco-Mondragon E, Jimenez A, Palladino-Davis AG, Davis D, Escamilla-Cejudo JA. Hispanic health in the USA: a scoping review of the literature. Public Health Rev. 2016;37:31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Columbus Public Health’s Office of Assessment & Surveillance and the Columbus Office of Minority Health. Franklin County Minority Health Facts: Focus on Hispanics/Latinos. Columbus Public Health. 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Cavanaugh L, McCain C, Lezak R. Ohio’s growing minority population: an analysis of the Hispanic/Latino community. The Ohio Commission on Hispanic/Latino Affairs. 2021. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Rebholz CM, Macomber MW, Althoff MD, et al. Integrated models of education and service involving community-based health care for underserved populations: Tulane student-run free clinics. South Med J. 2013;106(3):217-223. doi: 10.1097/SMJ.0b013e318287fe9a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Lawson E, Vemulapalli V, Barnes A, Scott S, Wyne K, Shah S. Applying national diabetic care standards for the management of a hispanic population attending a free clinic. J Community Health. 2023;48(4):576-584. doi: 10.1007/s10900-023-01199-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Rojas SM, Smith SD, Rojas S, Vaida F. Longitudinal hyperlipidemia outcomes at three student-run free clinic sites. Fam Med. 2015;47(4):309-314. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chew LD, Bradley KA, Boyko EJ. Brief questions to identify patients with inadequate health literacy. Fam Med. 2004;36(8):588-594. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Flegal KM, Ezzati TM, Harris MI, et al. Prevalence of diabetes in Mexican Americans, Cubans, and Puerto Ricans from the Hispanic Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 1982-1984. Diabetes Care. 1991;14(7):628-638. doi: 10.2337/diacare.14.7.628 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. National Center for Health Statistics (NCHS). Health, United States, 2003. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2003. (Department of Health and Human Services, DHHS Publication No. 2003-1232.)

- 11. Flores G, Abreu M, Olivar MA, Kastner B. Access barriers to health care for Latino children. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152(11):1119-1125. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.152.11.1119 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Saeed SA, Masters RM. Disparities in health care and the digital divide. Curr Psychiatry Rep. 2021;23(9):61. doi: 10.1007/s11920-021-01274-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Morris NS, MacLean CD, Chew LD, Littenberg B. The Single Item Literacy Screener: evaluation of a brief instrument to identify limited reading ability. BMC Fam Pract. 2006;7:21. doi: 10.1186/1471-2296-7-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Christy SM, Cousin LA, Sutton SK, et al. Characterizing health literacy among Spanish language-preferring Latinos ages 50-75. Nurs Res. 2021;70(5):344-353. doi: 10.1097/NNR.0000000000000519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Elder JP, Ayala GX, Parra-Medina D, Talavera GA. Health communication in the Latino community: issues and approaches. Annu Rev Public Health. 2009;30:227-251. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.031308.100300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]