Abstract

Introduction:

Factor Xa (FXa) inhibitors are superior to vitamin K antagonists (VKAs) in terms of avoiding hemorrhagic complications. However, no robust data are available to date as to whether this also applies to the early phase after stroke. In this prospective registry study, we aimed to investigate whether anticoagulation with FXa inhibitors in the early phase after acute ischemic stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA) is associated with a lower risk of major bleeding events compared with VKAs.

Materials and methods:

The Prospective Record of the Use of Dabigatran in Patients with Acute Stroke or TIA (PRODAST) study is a prospective, multicenter, observational, post-authorization safety study at 86 German stroke units between July 2015 and November 2020. Primary outcome was a major bleeding event during hospital stay. Secondary endpoints were recurrent strokes, recurrent ischemic strokes, TIA, systemic/pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, death and the composite endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism, life-threatening bleeding and death.

Results:

In total, 10,039 patients have been recruited. 5,874 patients were treated with FXa inhibitors and 1,050 patients received VKAs and were eligible for this analysis. Overall, event rates were low. We observed 49 major bleeding complications during 33,297 treatment days with FXa-inhibitors (rate of 14.7 cases per 10,000 treatment days) and 16 cases during 7,714 treatment days with VKAs (rate of 20.7 events per 10,000 treatment days), translating into an adjusted hazard ratio (aHR) of 0.70 (95% confidence interval (95% CI): 0.37–1.32) in favor of FXa inhibitors. Hazards for ischemic endpoints (63 vs 17 strokes, aHR: 0.96 (95% CI: 0.53–1.74), mortality (33 vs 6 deaths, aHR: 0.87 (95% CI: 0.33–2.34)) and the combined endpoint (154 vs 39 events, aHR: 0.99 (95% CI: 0.65–1.41) were not substantially different.

Discussion and conclusion:

This large real-world study shows that FXa inhibitors appear to be similarly effective in terms of bleeding events and ischemic endpoints compared to VKAs in the early post-stroke phase of hospitalization. However, the results need to be interpreted with caution due to the low precision of the estimates.

Keywords: Atrial fibrillation, ischemic stroke, recurrent stroke, bleeding, vitamin-K antagonists, factor-Xa-inhibitors

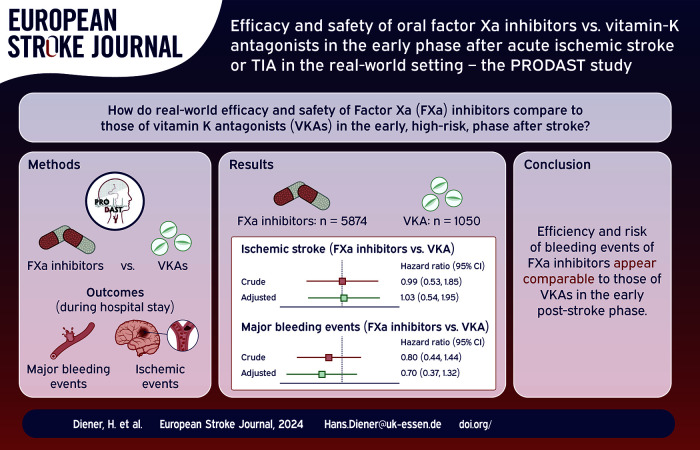

Graphical abstract.

Introduction

Patients with atrial fibrillation (AF) who suffered a transient ischemic attack (TIA) or ischemic stroke are at high risk for recurrent stroke. This risk is highest immediately after the event 1 and therefore oral anticoagulation should be started as early as possible. However, if anticoagulation is initiated too early, especially in large infarct areas, there is a risk of hemorrhagic transformation (HT) 2 or bleeding into the ischemic area. A number of retrospective and prospective registry studies have examined the timing of initiation of anticoagulation after an ischemic stroke with conflicting results in ideal timing.3–6 In addition, two randomized trials have addressed this topic: The TIMING trial randomized 888 patients with ischemic stroke to early initiation of anticoagulation with non-vitamin K dependent oral anticoagulants (NOACs) within 4 days compared to a start at 5–10 days and found a strong trend in favor of an early anticoagulation. 7 The ELAN trial randomized 2,013 participants with ischemic stroke and AF and also found numerical superiority of early anticoagulation over later anticoagulation. 8 Beyond the results of randomized trials, however, data from prospective registry studies are also necessary and important in order to reflect everyday clinical practice and to include patients who were not included in randomized trials. Prospective registry studies are necessary because there is evidence that real-world use of secondary prevention therapy in patients with TIA/stroke is often provided beyond RCTs recommendations. 9 The PRODAST study investigated the initiation of oral anticoagulation with respect to recurrent ischemic stroke and intracerebral hemorrhage in the real-world setting. 10 In a first part of the study, vitamin K antagonists (VKA) were compared with dabigatran over a follow-up period of 90 days. This published part of the study showed a decreased risk of intracranial hemorrhage in patients who were treated with dabigatran in the real-world setting. 11 Here, we present another part of the study, examining anticoagulation with factor Xa inhibitors (FXa), that is, apixaban, edoxaban, or rivaroxaban, with VKA in AF patients with recent (within 1 week) TIA or ischemic stroke. Our hypothesis was that anticoagulation with FXa inhibitors in the early phase after acute ischemic stroke or TIA would result in a reduced risk for major bleeding events compared with VKAs.

Material and methods

Study design

The multi-center PRODAST study is a non-interventional post-authorization safety study (PASS), which recruited 10,039 patients after recent (⩽7 days) acute ischemic stroke or TIA with non-valvular AF at 86 German stroke units between July 2015 and November 2020. The study design has been published. 10 In brief: patients had to be ⩾18 years old, and written informed consent (IC) was needed for inclusion. Patients with mechanical heart valves or valve disease that was expected to require valve replacement intervention (surgical or non-surgical) during the next 3 months were excluded, as well as participants in any RCT of an experimental drug or device, women of childbearing age without anamnestic exclusion of pregnancy, or who were not using an effective contraception, and nursing mothers. Patients were treated with an FXa-inhibitor chosen by the treating clinicians or a VKA, or other anti-thrombotic therapies, and followed until hospital discharge. The choice of anticoagulation or antithrombotic treatment was left to the treating physician. The time of initiation and regimen of anticoagulation was decided by the local investigator, and recorded on a daily basis, patients were followed up until the time of hospital discharge.

Outcomes

The primary outcome was major bleeding events during hospital stay. Secondary endpoints were recurrent strokes, recurrent ischemic strokes, TIA, systemic/pulmonary embolism, myocardial infarction, and death. Additionally, we analyzed the composite endpoint of stroke, systemic embolism, life-threatening bleeding, and death.

Major bleeding events were defined as fatal bleeding, intracranial, intraocular, intraspinal, retroperitoneal, intra-articular or intramuscular bleeding causing a compartment syndrome, or clinically overt bleeding associated with either a decrease in hemoglobin concentration of >2 g/dL, indication for transfusion of two or more units of whole blood or packed cells, or indication for surgical intervention. For estimation of infarct sizes, the ABC/2 formula was applied. 12 Infarct sizes were measured at study sites. Hemorrhagic transformation or bleeding was graded using the ECASS criteria. 13 After both central and local data review, unclear outcomes were confirmed by an independent Clinical Adjudication Committee (CAC), taking into account all available information.

Statistical analysis

To compare the event rates under current treatment with FXa-inhibitors with VKAs, each patient’s observed time was considered from the day of treatment initiation until the occurrence of the endpoint event, relative to the index event. Observations were analyzed in Cox-proportional hazards regressions with censoring at the time of treatment change, an alternative severe event (i.e. any other endpoint, except TIA) or discharge. Minimally adjusted and adjusted hazard ratios (HR) were estimated, where minimally adjusted models allowed for different risk depending on prevalent antithrombotic medication and were adjusted for age, study site (as random effect), and time-varying (daily, current) antithrombotic medication in the categories VKA, dabigatran, FXa-inhibitors, antiplatelets, and non-oral antithrombotic medication. Additional risk factors to correct for confounding or treatment by indication as derived from directed acyclic graphs (DAGs) (see online Figure 1) were included in adjusted models. DAGs were created a priori based on the prior knowledge of factors for choice of early anticoagulant treatment and/or the aforementioned outcome events. Therefore, minimally sufficient adjustment sets were derived in order to estimate the total effect of respective anticoagulant treatment on the outcome events. The adjustment matrix shown in Supplemental Table 1 provides an overview on relevant confounders that were taken into account in respective multivariable models. To account for the varying duration of the effect of antithrombotic drugs beyond intake, the respective end of therapy was postponed by a lag time, as previously described 10 (Supplemental Table 2). Only complete data were used for the analyses, which were done with SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Patients’ characteristics

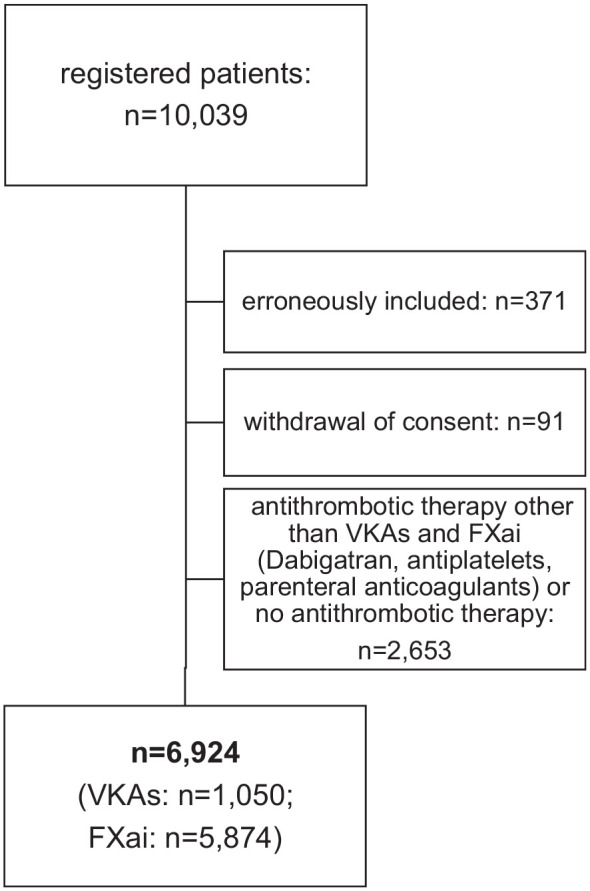

The treatment outcomes with FXa-inhibitors versus VKAs are based on data from 6,924 patients during an average of 9 days of hospital stay (total observation time 62,259 patient days). About 5,874 patients received treatment with FXa-inhibitors directly before or after the initial ischemic stroke or TIA, another 1,050 patients were treated with VKAs (Figure 1 and Figure 3). VKA-patients were predominantly men (62% vs 49% treated with FXa-inhibitors) with permanent AF (50% vs 35%), with a higher proportion of TIAs (31% vs 23%) and smaller median infarct size (2.07 ml vs 3.13 ml). Other demographic, clinical and event specific characteristics were comparable between these two patient groups, as summarized in Table 1. In addition, Supplemental Table 3 shows that characteristics of patients excluded for this analysis did not substantially differ from patients treated with FXa inhibitors or VKA.

Figure 1.

CONSORT diagram of the patients in the analysis.

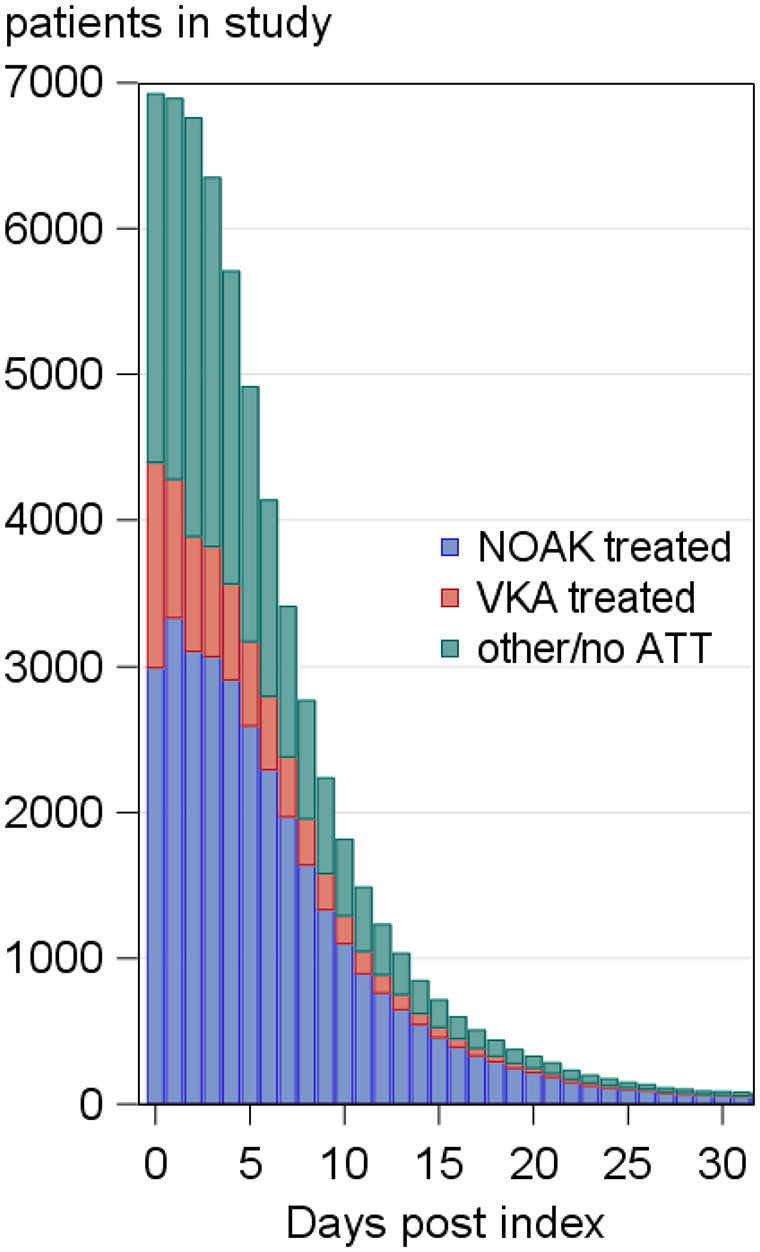

Figure 3.

Daily information (in relation to index event, here censored after 30 days) on treatment and follow-up for patients in PRODAST, who received VKAs or FX-inhibitors at some time during hospital stay.

Table 1.

Characteristics of PRODAST patients who were treated with FXa-inhibitors or VKAs in hospital or prior to their event.

| N (%), or as specified | FXa-inhibitors | VKAs |

|---|---|---|

| Participants | 5,874 (100%) | 1,050 (100%) |

| Female | 2,989 (51%) | 402 (38%) |

| Age [years, median (5th–95th percentile)] | 80.0 (63.0–91.0) | 79.0 (62.0–90.0) |

| Medical history of: Hypertension | 5,081 (86%) | 927 (88%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 1,826 (31%) | 343 (33%) |

| Congestive Heart failure/left ventricular dysfunction | 820 (14%) | 173 (16%) |

| Ischemic stroke | 1,327 (23%) | 239 (23%) |

| Hemorrhagic stroke | 36 (1%) | 6 (1%) |

| Falls with required med. treatment | 448 (8%) | 82 (8%) |

| Higher degree of renal dysfunction | 171 (3%) | 99 (9%) |

| Liver disease (liver cirrhosis; persistent Bilirubin > 2× ULN) | 36 (1%) | 9 (1%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 2,264 (39%) | 446 (42%) |

| Body mass index [kg/m², mean (std) [% missing]] | 27.2 (5.2) [15%] | 27.3 (4.8) [9%] |

| Current smoker | 458 (9%) | 72 (7%) |

| Former smoker | 1,432 (28%) | 333 (35%) |

| Smoking status missing | 815 | 86 |

| AF characteristics: Paroxysmal | 1,927 (33%) | 337 (32%) |

| Persistent | 465 (8%) | 98 (9%) |

| Long-lasting persistent | 155 (3%) | 36 (3%) |

| Permanent | 2,060 (35%) | 524 (50%) |

| Initial diagnosis | 1,234 (21%) | 50 (5%) |

| AF characteristics missing | 33 | 5 |

| Prevalent antithrombotic medication | 4,359 (74%) | 980 (93%) |

| Event specification | ||

| Infarctsize [ml, mean (std) [% missing]] | 30.72 (345.67) [58%] | 21.15 (53.40) [66%] |

| TIA | 1,336 (23%) | 329 (31%) |

| Potentially symptomatic stenosis | 800 (14%) | 144 (14%) |

| Information missing | 31 | 3 |

| Systemic thrombolysis with rtPA | 594 (10%) | 62 (6%) |

| Thrombectomy | 487 (8%) | 62 (6%) |

| Systemic thrombolysis with rtPA + Thrombectomy | 256 (4%) | 11 (1%) |

| Information on acute therapy missing | 8 | 2 |

| Premorbid modified Rankin Scale (mRS) on admission [mean (std) [% missing]] | 1.2 (1.4) [2%] | 1.0 (1.3) [4%] |

| National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) [ mean (std)[% missing]] | 5.0 (5.8) [2%] | 3.7 (4.9) [2%] |

| Early hemorrh. Transformation | 277 (5%) | 54 (5%) |

| Duration of hospital stay [mean (std)] | 9.2 (7.1) | 8.4 (5.5) |

FXa, coagulation factor Xa; VKA, Vitamin K antagonist; TIA, transient ischemic attack; rtPA, tissue-type recombinant plasminogen activator; mRS, modified Rankin scale; NIHSS, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale; std, standard deviation; ULN, upper limit of normal.

Outcomes

Table 2 shows that the overall number and rates of events were low. We observed 49 events of major bleeding complications during 33,297 treatment days with FXa-inhibitors (rate of 14.7 cases per 10,000 treatment days) and 16 cases during 7,714 treatment days with VKAs (rate of 20.7 events per 10,000 treatment days). Rates of recurrent stroke were 22.0 among patients treated with VKAs and 18.9 per 10,000 treatment days among patients treated with FXa-inhibitors. The combined endpoint was observed in 46.3 per 10,000 treatment days for FXa-inhibitors and 50.6 events per 10,000 treatment days in patients receiving VKAs.

Table 2.

Number and rate of endpoints (per 10,000 treatment days) observed in patients treated with FXa-inhibitors or VKAs, occurring under the respective actual treatment during hospital stay.

| Events under current use of | FXa-inhibitors | VKAs |

|---|---|---|

| Total treatment days | 33,297 | 7,714 |

| Major bleeding | 49 (14.72) | 16 (20.74) |

| Bleeding ICH | 33 (9.91) | 9 (11.67) |

| Bleeding gastrointestinal | 8 (2.40) | 2 (2.59) |

| Life threatening bleeding | 38 (11.41) | 11 (14.26) |

| Hemorrh. transformation | 25 (7.51) | 5 (6.48) |

| Stroke | 63 (18.92) | 17 (22.04) |

| Ischemic stroke | 56 (16.82) | 15 (19.45) |

| Hemorr. stroke | 8 (2.40) | 2 (2.59) |

| TIA | 17 (5.1) | 3 (3.89) |

| Systemic or lung embolism | 7 (2.10) | 0 (0.00) |

| Myocardial infarction | 26 (7.82) | 3 (3.89) |

| Death from any reason | 33 (9.45) | 6 (7.59) |

| Combined EP | 154 (46.25) | 39 (50.56) |

FXa, Coagulationfactor Xa; VKA, Vitamin K antagonist; ATT, antithrombotic therapy; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage; TIA, transient ischemic attack; EP, endpoint.

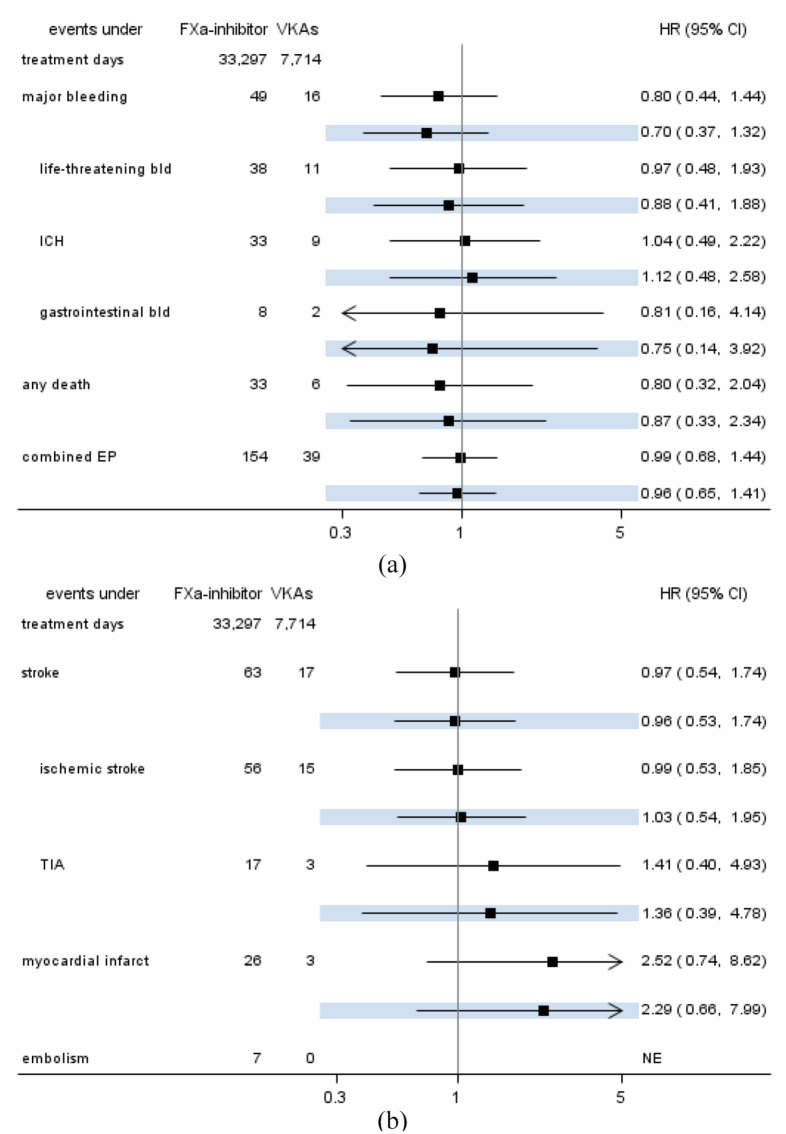

Direct comparison of event rates in Cox-regression with modeling of time-varying exposures to drugs revealed lower hazards for hemorrhagic events for major bleeding (adjusted HR: 0.70), in favor of FXa-inhibitors. Strength and direction of associations were minimally affected by adjustment for potential confounding factors (Figure 2(a)). Hazards for recurrent stroke and recurrent ischemic stroke were not different (adjusted HRs 0.96 and 1.03, respectively), but hazards for myocardial infarction were higher under treatment with FXa-inhibitors compared to treatment with VKAs (adjusted HR 2.52). Embolisms were too rare for comparison (0 events under treatment with VKAs, see Figure 2(b)).

Figure 2.

Minimally adjusted and adjusted (highlighted) hazard ratio estimates from Cox-regressions for major haemorrhagic (a) and ischemic (b) events under current use of FXA-inhibitors as compared to treatment with VKAs.

FXa, coagulation factor Xa; VKA, Vitamin K antagonist; bld, bleeding; ICH, intracranial hemorrhage; EP, endpoint; TIA, transient ischemic attack.

Discussion

This real-world study examines the risk and potential benefit of oral anticoagulation with FXa inhibitors versus VKAs in patients with AF who have suffered a TIA or ischemic stroke in the period until hospital discharge. In view of the large body of evidence for the efficacy and safety of NOACs, these have largely replaced VKAs in the secondary prevention of stroke. 14 However, the available data were actually limited to the subacute phase, so that a real-world analysis of the safety and efficacy of FXa compared to VKA in the days immediately after stroke was urgently needed. The main findings are as follows: The overall incidence of major bleeding complications and ischemic events, including recurrent ischemic strokes, in patients with AF and TIA or ischemic stroke is very low. Regarding ischemic endpoints, there were no relevant differences between initiation of oral anticoagulation with FXa inhibitors or VKAs. Regarding major bleeding complications, there was a trend in favor of FXa inhibitors with a 46% reduction in hazard. The confidence intervals, however, were wide. In the randomized trials on the benefits and risks of oral anticoagulation with non-vitamin K oral anticoagulants compared with vitamin K antagonists, patients who had recently suffered an ischemic stroke or TIA were excluded.15–18 In the early phase after stroke, both the risk of recurrent stroke and the risk of hemorrhage into the infarct are potentially increased. Therefore, beyond the two randomized trials7,8 on the optimal timing of initiation of oral anticoagulation in patients with AF after an ischemic stroke, it was necessary to obtain and analyze data on efficacy and safety from everyday clinical practice. The randomized trials examined the timing of initiation of NOACs after TIA or stroke in patients with AF but did not compare NOACs with VKAs in early initiation of anticoagulation. Our findings are also relevant for health care systems and countries where FXa inhibitors are either not available, not reimbursed by the health care system, or very expensive.

The PRODAST stroke registry study was set up as a postauthorization safety study (PASS), to compare patients treated with dabigatran and VKAs over a follow-up time of 90 days. 10 Here we present the analysis of patients in the PRODAST registry who were treated with FXa inhibitors, compared with patients treated with VKAs, all followed until hospital discharge. Due to funding restrictions, we could follow these patients only until discharge from hospital. We observed a very low rate of ischemic events and major bleeding complications compared with earlier periods. This is probably related to the fact that physicians on stroke units are meanwhile very good at optimally targeting patients and timing of anticoagulation and that anticoagulants are generally relatively safe in the real-world setting, even in the early phase after stroke.

The individual estimates showed only small effects in favor of FXa inhibitors for the ischemic endpoints. FXa inhibitors were not superior compared with VKA for hemorrhagic endpoints. Our results show that the evidence for the safety of FXa inhibition with regard to bleeding events15–18 is also applicable to the early phase after stroke in the real-world setting. Indeed, the effect sizes for FXa inhibitors (vs VKA) regarding hemorrhagic events in the ROCKET-AF, ENGAGE AF and ARISTOTLE trials were similar to those found in our study (i.e. HR ~ 0.7–0.8).

One problem with the analysis of registry studies is confounding. However, we tried to minimize this as best as possible by adjusting on the basis of causal diagrams and a wide range of carefully collected covariate information. Another limitation of our study is the low number of major bleeding events (n = 49) and therefore limited precision of the effect estimates. A strength of our study is the multicenter prospective design with large patient numbers, which reflects the treatment reality on German stroke units. However, the power is reduced by the fact that only very few ischemic and hemorrhagic endpoints occurred overall. This significantly limits the precision of the estimates. In addition, the average severity of strokes was low, so we cannot draw conclusions for patients with severe strokes. A major drawback of this study was the fact that observation could only be performed until hospital discharge after an average of 9 days, rather than over a defined period of 90 days as would have been desirable. The short observation period might increase the probability of cerebral hemorrhage and decrease the incidence of recurrent ischemic stroke.

In summary, this large registry study from daily practice demonstrates that FXa inhibitors appear to be similarly effective and safe in terms of bleeding events compared to VKAs in the early phase after stroke. However, our results need to be interpreted with caution due to the low precision of the estimates. Further studies from PRODAST will investigate, among other things, the ideal starting time of oral anticoagulation after stroke in the real-world setting.

Supplemental Material

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-eso-10.1177_23969873241242239 for Efficacy and safety of oral factor Xa inhibitors versus vitamin-K antagonists in the early phase after acute ischemic stroke or TIA in the real-world setting: The PRODAST study by Hans-Christoph Diener, Gerrit M Grosse, Anika Hüsing, Andreas Stang, Nils Kuklik, Marcus Brinkmann, Gabriele D Maurer, Hassan Soda, Carsten Pohlmann, Rüdiger Hilker-Roggendorf, Nikola Popovic, Peter Kraft, Bruno-Marcel Mackert, Christoph C Eschenfelder and Christian Weimar in European Stroke Journal

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all investigators and patients for their participation in the PRODAST study.

Footnotes

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: H-CD has received honoraria for participation in clinical trials, contribution to advisory boards or oral presentations from: Abbott, BMS, Boehringer Ingelheim, Daiichi-Sankyo, Novo-Nordisk, Pfizer, Portola, and WebMD Global. Boehringer Ingelheim provided financial support for research projects. H-CD received research grants from the German Research Council (DFG) and German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF). H-CD serves as editor of Neurologie up2date, Info Neurologie & Psychiatrie and Arzneimitteltherapie, as co-editor of Cephalalgia, and on the editorial board of Lancet Neurology and Drugs. GR received speaker’s honoraria and reimbursement for congress traveling and accommodation from Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi Sankyo and Pfizer. GMG has received research grants from the German Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF), the European Commission and the Lower Saxony Ministry of Science and Culture (MWK) and received honoraria from Boehringer Ingelheim. PK reports lecture honoraria and/or study grants from Daiichi Sankyo and Pfizer, outside the submitted work. CCE is an employee of Boehringer Ingelheim. The other authors declare no conflicts of interest related to the content of the presented work.

Funding: The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: This was an independent, investigator-initiated study supported by Boehringer Ingelheim (BI). BI had no role in the design, analysis or interpretation of the results in this study; BI was given the opportunity to review the manuscript for medical and scientific accuracy as it relates to BI substances, as well as intellectual property considerations. The authors disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: The authors did not receive payments related to the development of the manuscript. The authors meet criteria for authorship as recommended by the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE).

Ethical approval: Ethical approval was provided by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Duisburg-Essen (No. 15-6202-BO). All procedures were conducted in accordance with the national law, the 1964 Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments and the recommendations of the guidelines on Good Clinical Practice and Good Epidemiological Practice.

Informed consent: Written informed consent (IC) was obtained from all patients. In cases where IC could not be obtained in a timely manner due to the patient’s condition, the local investigator was allowed to decide on study inclusion, and the IC process was rescheduled as soon as possible.

Guarantor: Hans-ChristophDiener.

Registration: ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02507856.

Contributorship: HCD, CCE, AS, MB, and CW conceived the study. HCD, NK, AH, AS, MB, CCE, and CW were involved in the protocol development, gaining ethics and regulatory approvals, data management and conceiving the statistical analysis plan. HCD, GMG, AH, and AS analyzed data and interpreted results. HCD, GMG, and AH wrote the first draft of the manuscript. GMG, GDM, HS, CP, RHR, NP, PK, and BMM were involved in patient recruitment. All authors reviewed and edited the manuscript and approved the final version of the manuscript.

ORCID iDs: Hans-Christoph Diener  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6556-8612

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6556-8612

Gerrit M Grosse  https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5335-9880

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5335-9880

Christoph C Eschenfelder  https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2766-2488

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2766-2488

Supplemental material: Supplemental material for this article is available online.

References

- 1. Arboix A, García-Eroles L, Oliveres M, et al. Clinical predictors of early embolic recurrence in presumed cardioembolic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis 1998; 8: 345–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. England TJ, Bath PM, Sare GM, et al. Asymptomatic hemorrhagic transformation of infarction and its relationship with functional outcome and stroke subtype: assessment from the tinzaparin in acute ischaemic stroke trial. Stroke 2010; 41: 2834–2839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Palaiodimou L, Stefanou MI, Katsanos AH, et al. Early anticoagulation in patients with acute ischemic stroke due to atrial fibrillation: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med 2022; 11(17): 4981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Seiffge D, Traenka C, Polymeris A, et al. Early start of DOAC after ischemic stroke: risk of intracranial hemorrhage and recurrent events. Neurology 2016; 87: 1856–1862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Yaghi S, Henninger N, Giles JA, et al. Ischaemic stroke on anticoagulation therapy and early recurrence in acute cardioembolic stroke: the IAC study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry 2021; 92: 1062–1067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Arihiro S, Todo K, Koga M, et al. Three-month risk-benefit profile of anticoagulation after stroke with atrial fibrillation: the SAMURAI-nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (NVAF) study. Int J Stroke 2016; 11: 565–574. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Oldgren J, Åsberg S, Hijazi Z, et al. Early versus delayed non-vitamin K antagonist oral anticoagulant therapy after acute ischemic stroke in atrial fibrillation (TIMING): a registry-based randomized controlled noninferiority study. Circulation 2022; 146: 1056–1066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Fischer U, Koga M, Strbian D, et al. Oral anticoagulation and stroke in atrial fibrillation. New Engl J Med 2003; 349: 2360–2361. [Google Scholar]

- 9. De Matteis E, De Santis F, Ornello R, et al. Divergence between clinical trial evidence and actual practice in use of dual antiplatelet therapy after transient ischemic attack and minor stroke. Stroke 2023; 54: 1172–1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Grosse GM, Weimar C, Kuklik N, et al. Rationale, design and methods of the prospective record of the use of dabigatran in patients with acute stroke or TIA (PRODAST) study. Eur Stroke J 2021; 6: 438–444. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Grosse GM, Hüsing A, Stang A, et al. Early or late initiation of dabigatran versus vitamin-k-antagonists in acute ischemic stroke or TIA: the PRODAST study. Int J Stroke 2023; 18: 1169–1177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sims JR, Gharai LR, Schaefer PW, et al. ABC/2 for rapid clinical estimate of infarct, perfusion, and mismatch volumes. Neurology 2009; 72: 2104–2110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Larrue V, von Kummer R, Müller A, et al. Risk factors for severe hemorrhagic transformation in ischemic stroke patients treated with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator: a secondary analysis of the European-Australasian acute stroke study (ECASS II). Stroke 2001; 32: 438–441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Klijn CJ, Paciaroni M, Berge E, et al. Antithrombotic treatment for secondary prevention of stroke and other thromboembolic events in patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack and non-valvular atrial fibrillation: a European stroke organisation guideline. Eur Stroke J 2019; 4: 198–223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Connolly SJ, Ezekowitz MD, Yusuf S, et al. Dabigatran versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. New Engl J Med 2009; 361: 1139–1151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Patel MR, Mahaffey KW, Garg J, et al. Rivaroxaban versus warfarin in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation. New Engl J Med 2011; 365: 883–891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Granger CB, Alexander JH, McMurray JJV, et al. Apixaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. New Engl J Med 2011; 365: 981–992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Giugliano RP, Ruff CT, Braunwald E, et al. Edoxaban versus warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation. New Engl J Med 2013; 369: 2093–2104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material, sj-docx-1-eso-10.1177_23969873241242239 for Efficacy and safety of oral factor Xa inhibitors versus vitamin-K antagonists in the early phase after acute ischemic stroke or TIA in the real-world setting: The PRODAST study by Hans-Christoph Diener, Gerrit M Grosse, Anika Hüsing, Andreas Stang, Nils Kuklik, Marcus Brinkmann, Gabriele D Maurer, Hassan Soda, Carsten Pohlmann, Rüdiger Hilker-Roggendorf, Nikola Popovic, Peter Kraft, Bruno-Marcel Mackert, Christoph C Eschenfelder and Christian Weimar in European Stroke Journal