Abstract

Introduction

An electronic prospective surveillance model (ePSM) uses patient-reported outcomes to monitor impairments along the cancer pathway for timely management. Randomised controlled trials show that ePSMs can effectively manage cancer-related impairments. However, ePSMs are not routinely embedded into practice and evidence-based approaches to implement them are limited. As such, we developed and implemented an ePSM, called REACH, across four Canadian centres. The objective of this study is to evaluate the impact and quality of the implementation of REACH and explore implementation barriers and facilitators.

Methods and analysis

We will conduct a 16-month formative evaluation, using a single-arm mixed methods design to routinely monitor key implementation outcomes, identify barriers and adapt the implementation plan as required. Adult (≥18 years) breast, colorectal, lymphoma or head and neck cancer survivors will be eligible to register for REACH. Enrolled patients complete brief assessments of impairments over the course of their treatment and up to 2 years post-treatment and are provided with a personalised library of self-management education, community programmes and when necessary, suggested referrals to rehabilitation services. A multifaceted implementation plan will be used to implement REACH within each clinical context. We will assess several implementation outcomes including reach, acceptability, feasibility, appropriateness, fidelity, cost and sustainability. Quantitative implementation data will be collected using system usage data and evaluation surveys completed by patient participants. Qualitative data will be collected through focus groups with patient participants and interviews with clinical leadership and management, and analysis will be guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research.

Ethics and dissemination

Site-specific ethics approvals were obtained. The results from this study will be presented at academic conferences and published in peer-reviewed journals. Additionally, knowledge translation materials will be co-designed with patient partners and will be disseminated to diverse knowledge users with support from our national and community partners.

Keywords: Implementation Science, oncology, Patient Reported Outcome Measures, Self-Management, eHealth

STRENGTHS AND LIMITATIONS OF THIS STUDY.

A strength of REACH is the remote and automated nature of the system that allows patients to complete assessments outside of clinical visits and receive tailored support to manage physical cancer-related impairments.

An additional strength of this study is the use of quantitative and qualitative methods and the integration of implementation science models, frameworks and tools to facilitate an understanding of processes, barriers and strategies for the successful implementation of an electronic prospective surveillance model.

A limitation of this study is the possibility that only patients who speak English and have higher levels of comfort and confidence with technology will enrol in REACH and participate in this study.

The single-arm design of this implementation study limits the ability to compare the effectiveness of the implementation strategies for REACH with alternative approaches.

Background

Despite the high rates of treatment-related adverse effects among people with cancer,1,4 cancer-related impairments often go undetected and existing rehabilitation services are underused.5 6 Recognising these challenges, the Canadian Cancer Rehabilitation Team (CanRehab) was formed as a national collaborative effort comprising of researchers, people with lived experience, clinicians and decision-makers. The CanRehab team aims to close the knowledge-to-practice gap in cancer rehabilitation through testing the implementation of evidence-based solutions to improve the systematic identification of the adverse effects of cancer and its treatment, increase access to cancer rehabilitation using innovative eHealth solutions and extend reach to a larger population of cancer survivors.

One such evidence-based and patient-centred solution is an electronic prospective surveillance model (ePSM) for cancer rehabilitation.7 8 ePSMs involve the routine assessment of cancer-related impairments using patient-reported outcomes at predetermined intervals along the cancer pathway (eg, diagnosis, adjuvant treatment, follow-up surveillance) which are used to inform tailored interventions to manage their impairments.7 8 ePSMs can vary in their design and implementation. For instance, some systems may involve patients completing assessments for outpatient clinical visits, where the assessment results are directly integrated into clinical workflows by providing clinicians with a summary report of the patient’s symptoms, alerts for symptoms that require attention and recommendations for clinical actions and referrals to services and programmes.9 Alternatively, other systems may ask patients to complete assessments remotely using their own devices and focus on promoting self-management by providing links to educational materials tailored to the assessment results, while also recommending patients to contact their oncology team if they report a symptom that may require further evaluation.9

Randomised controlled trials have demonstrated that ePSMs are effective models for identifying and managing anticipated treatment-related impairments.10,14 An important next step is implementation into routine cancer care; however, less is known about optimal approaches to do so.15 Previously reported barriers to implementation include challenges integrating an ePSM into clinical workflows, patients’ perceived difficulty, usefulness and acceptability of reporting symptoms remotely, and ambiguity around appropriate risk stratification criteria to guide referral pathways.16 17 Strategies to overcome these barriers may include assessing readiness and current work processes, adapting and tailoring the implementation to the clinical context, engaging clinical staff (eg, preparing champions and providing feedback to clinics on the percentage of patients using the system) and providing technical assistance.15 18 Building on existing evidence of the efficacy of ePSMs and current challenges to implementation, this study aims to evaluate the implementation of REACH into routine cancer care, including understanding barriers and facilitators to implementation.

Methods

Pre-implementation planning

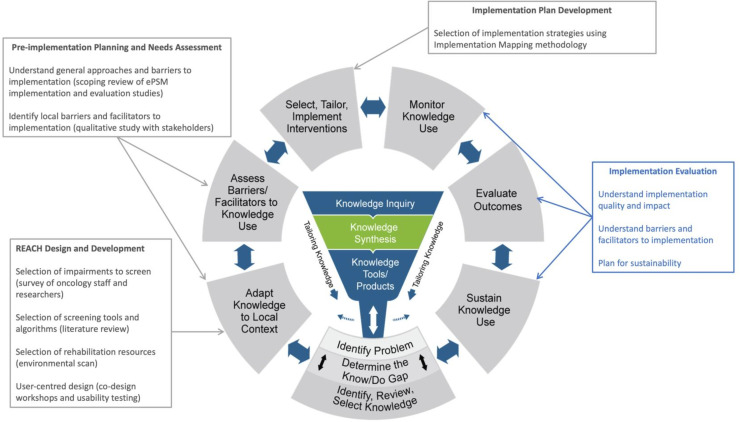

The CanRehab team developed an ePSM, called REACH, for people diagnosed with lymphoma, breast, head and neck or colorectal cancers. The Knowledge-to-Action (KTA) cycle19 guided the development and implementation planning and evaluation of REACH (figure 1). Several teams worked closely together to develop REACH and adapt this evidence-based intervention to our local contexts (design details to be published elsewhere). Briefly, a working group of researchers and clinicians were responsible for developing the initial logic and list of resources. This working group surveyed clinicians and researchers across the CanRehab team and within their network to identify priority impairments for each disease site. Next, a literature review of measurement instruments and cut-off scores was conducted. Lastly, the team conducted an environmental scan of national, regional and local resources for the identified impairments. The design team conducted a four-step person-centred design process20 that encompassed stakeholder interviews, a co-design workshop with the project’s Patient and Family Advisory Committee (PFAC) and usability testing. The design and development teams subsequently collaborated to convert the prototype into a web-based application. Team members with training in implementation science led a scoping review of the barriers and facilitators to implementation (guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)),21 and implementation strategies (categorised by the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change taxonomy)22 used for ePSM interventions in cancer care.9 Building on these findings, a pre-implementation needs assessment was conducted using qualitative focus groups and interviews with various stakeholders, including members of the PFAC, healthcare providers and clinical leadership.23 This qualitative data was also analysed using the CFIR. Data from the qualitative study and scoping review were used to develop an implementation plan using an Implementation Mapping approach, including the use of the CFIR-ERIC matching tool24 and discussions regarding each strategy’s feasibility and importance, use among other ePSM systems and the contexts of the clinical settings (implementation plan development details to be published elsewhere).

Figure 1. Application of the Knowledge-to-Action cycle for the implementation of REACH. Adapted from Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, Straus SE, Tetroe J, Caswell W, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26(1):13–24. ePSM, electronic prospective surveillance model.

Study design

This multicentre, prospective, single-arm implementation study uses a convergent parallel mixed methods design.25 Reporting of this study will follow the Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies.26 Following our preliminary work, the current study represents three steps in the KTA cycle, specifically (1) monitor knowledge use, (2) evaluate outcomes and (3) sustain knowledge use (ie, the extent to which REACH can be maintained within each setting’s operations).

Implementation settings

This study will be conducted at four sites in Canada, including the Princess Margaret Cancer Centre (Toronto, Ontario), BC Cancer (Vancouver, British Columbia), Saint John Regional Hospital (Saint John, New Brunswick) and Dr. H. Bliss Murphy Cancer Centre (St. John’s, Newfoundland). All four centres operate under single-payer healthcare systems that are primarily administered and delivered by their respective province and that provide universal coverage for medically necessary services. Princess Margaret Cancer Centre and BC Cancer—Vancouver are situated in densely populated urban areas, serving substantially higher volumes of patients with larger clinical teams. Given their size, these centres commonly operate with a larger number and wider variety of leadership and managerial roles including radiation team leads, nurse managers and physician leads assigned to specific disease sites. Alternatively, Dr H Bliss Murphy Cancer Centre and the oncology clinic at Saint John Regional Hospital are situated in small urban centres that also serve many patients from rural areas. Due to their size, these cancer centres typically deliver more general oncology clinics that are not exclusive to specific disease sites. As such, these centres have fewer leadership and managerial roles.

Study population

Patient participants

Individuals who have received any part of their cancer treatment at one of the four participating centres will be able to register and use the REACH system. Inclusion criteria include: (1) age 18 years or older; (2) diagnosed with breast, colorectal, lymphoma or head and neck cancer; and (3) scheduled to commence cancer treatment, currently receiving cancer treatment or completed active treatment and receiving follow-up care within the last 2 years. As REACH is a clinical tool being implemented as part of routine clinical care, research consent is not required for patients to register and use the REACH system, although the patient must accept the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy. On registering, patients are provided with a unique REACH identification number. Those who register for REACH will be presented with a consent page on the system for (1) their consent to use their data from the REACH system to study how to improve the system and (2) for permission to contact them to participate in additional questionnaires and/or qualitative focus groups as part of the research study. Patients can choose to agree or decline any or all the research consent questions.

Oncology staff participants

Front-line healthcare providers, clinical leadership and administrators from each site, including managers, clinical leads and directors, are important actors in the implementation process. As such, a sample of each will be asked to participate in the implementation evaluation study.

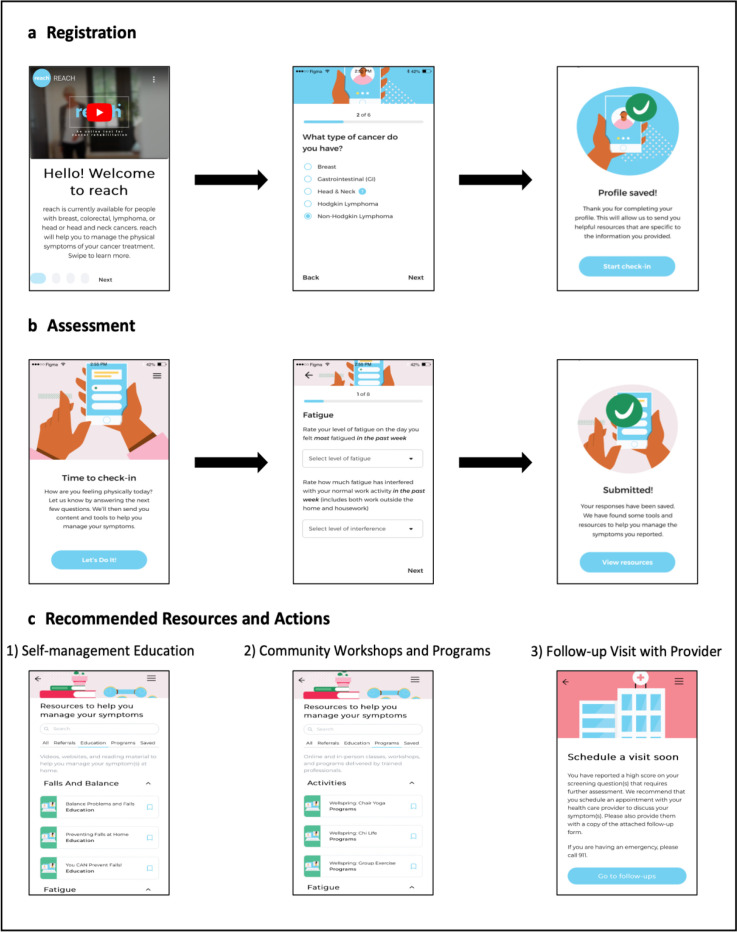

REACH intervention

REACH is a web-based application that systematically screens for and identifies cancer-related impairments and links patients to rehabilitation resources based on reported needs that can be accessed via a mobile phone, tablet, laptop or desktop computer. REACH is completely remote and automated, meaning patients complete patient-reported outcome assessments independently outside of clinical visits. Enrolled patients are prompted via email at regular intervals to log into REACH and complete a brief assessment throughout treatment and during follow-up surveillance for up to 2 years post-treatment. The specific impairments assessed, and frequency of assessments are tailored by cancer type and treatment status, with each assessment designed to take approximately 5 min (table 1). The REACH system then automatically provides patients with suggestions based on their assessment scores, cancer type and demographic and clinical information. The resources offered to patients follow a tiered approach based on the assessment scores with three distinct levels: (1) self-management education (ie, links to videos, handouts, websites and suggested classes); (2) suggested community workshops and programmes to register for (online or in-person); and (3) a recommendation to schedule a visit with their oncologist or family physician for further assessment and management of the impairment identified. Notably, REACH will only provide patients with a recommendation for further assessment if they also indicate they are not currently receiving treatment or management for that impairment. Additionally, data from the REACH system (eg, assessment scores, resources recommended to patients) are not linked to the electronic medical records used by the participating centres, and the involvement of healthcare providers in the REACH system is limited to instances where patients are recommended for further assessment. In these cases, REACH provides the patient with a report they can bring to their appointment. This report outlines the identified impairments and includes suggested referrals to community and hospital services that the oncologist or family physician may consider. See figure 2 for an overview of the REACH system.

Table 1. Impairments screened by REACH.

| Impairment | Cancer type | Adapted measures | Frequency during treatment | Frequency after treatment |

| Fatigue | Breast, colorectal, head and neck, lymphoma | FSI | 3 months | 3 months (year 1)6 months (year 2) |

| Pain | Breast, colorectal, head and neck, lymphoma | ESAS pain and BPI | 3 months | 3 months (year 1)6 months (year 2) |

| Activities of daily living | Breast, colorectal, head and neck, lymphoma | PRFS and FSQ | 3 months | 3 months (year 1)6 months (year 2) |

| Falls and balance | Breast, colorectal, head and neck, lymphoma | STEADI | 3 months | 3 months (year 1)6 months (year 2) |

| Return to work | Breast, colorectal, lymphoma | None | None | 3 months (year 1) no screening year 2 |

| Shoulder and neck dysfunction | Breast, head and neck | QuickDASH, Neck Dissection Impairment Index | 3 months | 3 months (year 1)6 months (year 2) |

| Sexual dysfunction | Breast, colorectal | BSSC-M and F | None | 3 months (year 1)6 months (year 2) |

| Lymphoedema | Breast | Lymphoedema symptom report | 2 months | 2 months (year 1)6 months (year 2) |

| Dysphagia | Head and neck | 4QT | 2 months | 3 months (year 1) no screening year 2 |

| Trismus | Head and neck | EORTC QLQ - H&N35 | 2 months | 3 months (year 1) no screening year 2 |

| Speech | Head and neck | UW Head and Neck Questionnaire | None | 3 months (year 1) no screening year 2 |

| Xerostomia | Head and neck | EORTC QLQ - H&N35 | 2 months | 3 months (year 1) no screening year 2 |

BPI, Brief Pain Inventory; BSSC-M and F, Brief Sexual Symptom Checklist Male and Female; EORTC QLQ - H&N35, European Organisation for Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire Head and Neck ModuleESASEdmonton Symptom Assessment SystemFSI, Fatigue Symptom Inventory; FSQFunctional Status QuestionnairePRFS, Patient-Reported Functional Status; 4QT4-point questionnaire testQuickDASH, The Disabilities of the Arm, Shoulder and Hand Score; STEADI, Stopping Elderly Accident, Deaths and InjuriesUWUniversity of Washington

Figure 2. Overview of the REACH system. (a) Screenshots of registration process for REACH (video describing system and creation of user profile. (b) Screenshots of patient assessment. (c) Screenshots of possible types of resources recommended to patients.

Implementation strategies

A multifaceted implementation plan, consisting of several discrete implementation strategies will be used to implement REACH within each clinical context (see table 2). Implementation strategies are the methods and approaches used to support the adoption and delivery of healthcare interventions in practice.27 Feasible and acceptable implementation strategies identified in our pre-implementation work were defined using the ERIC taxonomy.22 Our approach comprises several discrete strategies that target multiple levels of the implementation of REACH, including patients, clinical staff and workflows. These include strategies aimed at (1) educating patients and staff about REACH (conducting educational meetings and distributing educational materials), (2) regularly engaging patients to ensure REACH is being used as intended (automated system reminders to complete assessments and to use the suggested resources), (3) engaging clinical leadership to discuss barriers and possible solutions to implementation (meetings, advisory boards and workgroups), (4) monitoring a dedicated email for REACH to respond to patient inquiries and technical issues that arise, (5) leveraging or modifying existing electronic systems to facilitate the delivery of educational information about REACH to patients and/or staff (patient portals, electronic medical records) and (6) monitoring the quality of implementation to identify necessary changes to the REACH system and/or implementation strategies.

Table 2. Implementation strategies used during implementation phase for REACH.

| Strategy | Actor | Action | Action target | Dose |

| Purposefully re-examine the implementation | REACH team members | Monitor implementation outcomes to inform changes to the system and implementation effort. | REACH team members will have a better understanding of implementation success, barriers to implementation and changes made throughout the implementation effort. | Four, 4-month plan-do-study-act cycles for each centre. |

| Change record systems | Information technology teams within each site | Leverage or modify existing electronic systems used by the sites to facilitate the delivery of information about REACH to patients. Strategy will be tailored to each site depending on the availability and type of electronic systems. | Improved efficiency of identifying and informing patients about REACH. | Changes will be made for the launch date and additional changes will be made throughout the implementation phase if necessary. |

| Conduct educational meetings | REACH team member and clinical leadership | Organise presentations about REACH at oncology rounds, nursing rounds and other team meetings. Strategy will be tailored to each site depending on how patients are being introduced to REACH. | Improved understanding and ability to communicate the purpose, registration process and use of REACH to patients. May include physicians, nurses and/or radiation therapists. | Frequency: one per stakeholder group prior to launch, followed by additional meetings if needed.Duration: 10–30 min (based on preferences and feasibility at each site).Format: in-person or virtual, synchronous or asynchronous (based on preferences and feasibility at each site). |

| Distribute educational materials | REACH team members and clinical leadership | Prepare pathways to distribute a handout about REACH to patients. Pathways are tailored to each site depending on clinical preferences and available resources. This may include an online education prescription system, a patient portal, physical or electronic education packages, group virtual or in-person education classes and displays at the clinical registration desks. | Enable patients to register and use the tool independently and assist clinical staff to offer REACH to patients. May include physicians, nurses, radiation therapists and administrative staff). | Pathways to distribute the REACH handout should be prepared within 1-week prior to the go-live date. Additional changes will be made to distribution processes if needed. |

| Intervene with patients to enhance adherence and uptake | REACH development team | REACH will provide automated reminders via email to patients use REACH as intended. | Enable patients to log in and complete assessments (if not completed) and to view recommended resources. | Patients will receive up to two reminders for each incomplete assessment 2 days and 3 days after the initial prompt.Patients will receive a reminder to view the recommended resources 1 month after completing the assessment. |

| Centralise technical assistance | REACH team members and development team | The REACH system will have a dedicated email for patients to ask questions about the system and report technical issues. | Improve user experience and develop an understanding of resources needed to ensure sustainability of the system following implementation pilot. | Responses to patient inquiries will be answered within 48 hours. |

| Use advisory boards and workgroups | REACH team members and clinical leadership | Work with clinical champions and management to resolve barriers to implementation, map work processes and plan changes to how REACH is implemented at the site. | Improved understanding of current clinical workflows. Ability to obtain necessary approvals for how patients are invited to register to REACH.Strategy may be tailored to involve multiple meetings with individuals depending on the availability of groups and specific barriers and solutions to discuss. | The frequency, number and duration of meetings will be tailored to each site. At least one meeting will be held during each 4-month plan-do-study-act cycle. |

Implementation data collection

REACH system usage

Data on the use of the REACH system will be extracted using system reports to inform: (1) the number of assessments completed, (2) time to complete the assessments and (3) the clicks/views of the recommended resources.

Patient-reported data

On registering to the system, participants create a user profile by providing the following demographic and clinical information: sex, age, cancer type, date of diagnosis, treatment status and institution receiving care. This demographic and clinical data will be extracted from the REACH system.

We will invite a subset of patient participants to complete a web-based feedback survey. Eligibility criteria to be invited to participate in the survey include: (1) consented to be contacted; (2) completed at least one assessment on REACH, (3) registered to REACH a minimum of 2 months prior to the survey invitation and (4) indicated on REACH that they are currently receiving or have completed treatment. Patients who are newly diagnosed and have not yet started treatment, or those under active surveillance, will not be invited to participate in the survey. This decision is based on the REACH system’s logic, which initiates symptom assessments once treatment has commenced. Additional demographics (eg, gender, ethnicity, socioeconomic status, education) will be obtained through this survey. Participants will be asked about the feasibility and acceptability of the system, and appropriateness of the resources offered. The survey will include questions from the 13-item Patient Feedback Form, which was developed by Basch and colleagues28 and adapted by Snyder and colleagues29 to evaluate patient satisfaction with patient-reported outcome measures that are integrated into clinical practice. Additionally, the survey will include the four-item Acceptability of Intervention Measure (AIM) and the four-item Intervention Appropriateness Measure (IAM).30 The AIM and IAM were designed to be as pragmatic as possible and have demonstrated strong psychometric properties. Lastly, participants will be asked about their use of the educational resources, programmes and referrals recommended by REACH.

A subset of participants who provide consent will be purposively sampled and asked to participate in qualitative focus groups at the end of the 16-month evaluation. Eligibility criteria to be invited to participate in the focus groups include: (1) consented to be contacted; (2) completed at least one assessment on REACH and (3) registered to REACH a minimum of 2 months prior to the focus group invitation. A maximum variation purposive sampling approach will be used to identify participants with diverse insights and experiences with REACH and ensure representation across age, gender, geographical location, cancer type, treatment status.31 Focus group topics will include the system’s feasibility, acceptability and appropriateness, and aim to understand barriers and facilitators to consistent use of the system. Focus groups will also seek to obtain patient feedback on the strategies used to facilitate patient awareness and registration. Following guidance on code saturation for focus groups, we plan to conduct a total of approximately five focus groups across all four study sites (approximately six to eight participants per focus group) and conduct additional focus groups if necessary.32 Focus groups will be conducted through video and take approximately 60 min to complete. Focus groups will be audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Participant-reported technical issues and inquiries sent to the dedicated email account for the REACH system (eg, issues with registration, completion of assessments, access to resources offered) will also be monitored by research staff and recorded in a log.

Oncology staff-reported data

Clinical leadership and administrators from each site, including managers, clinical leads and directors, as well as front-line healthcare providers involved in the implementation of REACH will be asked to participate in a one-on-one semi-structured interview at the end of the 16-month evaluation. Interviews will aim to understand the extent to which REACH can be successfully embedded into the clinical workflow and the barriers and facilitators to institutionalising REACH within the clinic’s ongoing operations. Following guidance for code saturation for interviews and to ensure representation of clinical leadership perspectives from all four study sites, we plan to conduct a total of approximately 15 interviews and conduct additional interviews if necessary.33 All interviews will be conducted via video and take approximately 30–60 min. Interviews will be digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Implementation strategy data collection

We will collect data on the implementation strategies employed and the impact and quality of the implementation strategies. This documentation will be guided by the Longitudinal Implementation Strategy Tracking System (LISTS)34 and the conceptual framework for implementation fidelity.35 36 LISTS incorporates the strategy reporting and specification standards developed by Proctor and colleagues27 and elements from the Framework for Reporting Adaptations and Modifications to Evidence-based Implementation Strategies.37 LISTS allows for the capturing of dynamic changes, including planned or unplanned strategy modifications and the addition or discontinuation of strategies. Information related to LISTS will be entered by a member of the research team every 4 months using the Research Electronic Data Capture data entry system developed for LISTS. The utility of LISTS has been demonstrated in an implementation study of patient-reported outcomes in oncology.38 The information collected via LISTS will be used to aid in the interpretation of the results of this current study.

Implementation outcomes

We will assess several implementation outcomes informed by Proctor and colleagues’ taxonomy of outcomes39 and the RE-AIM (reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation, maintenance) framework40 using the quantitative and qualitative measures described above. A priori targets for these outcomes have been identified where possible to evaluate implementation success. The description, measurement approach and target (where possible) for the quantitative data for each implementation outcome is displayed in table 3. Throughout the 16-month evaluation, these targets will be used to determine whether any changes need to be made to improve the implementation of REACH.

Table 3. Summary of quantitative measures for implementation outcomes.

| Outcome | Description | Data source | Measurement approach | Target | Measurement time point |

| Reach | Number and representativeness of patients who register to REACH and who consent to have their data used for research. | REACH system | The number and representativeness of registered patients (ie, cancer type, age, sex, treatment status, time since diagnosis, time registered to system). | Registration – none.Research consent – >60%. | Monitored every 4 months to help identify and inform necessary changes to the implementation strategies used to facilitate patient awareness and uptake. |

| Feasibility | The extent to which REACH can be successfully used by patients. | REACH system | Time to open screening questions. | 75% are opened within 7 days of initial prompt. | Monitored every 4 months to help identify and inform necessary changes to the REACH system and/or implementation strategies used to facilitate the completion of assessments. |

| Time to complete screening questions. | None | Monitored every 4 months to help identify and inform necessary changes to the REACH system and/or implementation strategies utilised to facilitate the timely completion of assessments. | |||

| Patient survey | REACH feedback survey (questions on the amount of time and frequency of reporting symptoms). | 75% of patients scored 2 (just right) on the patient feedback form feasibility questions. | Survey will be sent at 12 and 16 months. | ||

| Acceptability | The extent to which REACH is appealing, satisfactory and welcomed. | Patient survey | REACH feedback survey (questions from the AIM about the REACH system). | 75% of patients had an average score of ≥4 (agree). | Survey will be sent at 12 and 16 months. |

| Appropriateness | The extent to which REACH is fitting, suitable, applicable for the patient population. | Patient survey | REACH feedback survey (questions from the IAM about the REACH resources). | 75% of patients had an average score of ≥4 (agree). | Survey will be sent at 12 and 16 months. |

| Fidelity | The extent to which REACH was used as intended. | REACH system | Completion of screening questions. | 75% of all assessments scheduled were completed. | Monitored every 4 months to help identify and inform necessary changes to the REACH system and/or implementation strategies used to facilitate the completion of assessments. |

| Clicks on the REACH resources recommended to patients. | 75% of patients clicked on at least one resource recommended. | Monitored every 4 months to help identify and inform necessary changes to the REACH system and/or implementation strategies used to facilitate the use of the resources offered to patients. |

AIMAcceptability of Intervention Measure

Intervention data collection

Patient-reported outcome data collected as part of each assessment on REACH will be obtained from consenting patient participants and used to evaluate the effect of REACH on cancer-related impairments. This data will not be used to evaluate the implementation of REACH. The effects of the REACH intervention will be reported elsewhere.

Economic evaluation

We will report on the costs related to maintaining the REACH system and any changes made to the system. Additionally, we will report on costs related to implementing REACH (eg, development of and changes to educational materials, addressing patient inquiries and technical issues with the system and changes to site-specific electronic systems to facilitate the implementation of REACH).

Sample size

As this is an implementation study, one of the objectives is to understand the extent to which patients register and use REACH across each site. Therefore, we do not have a planned number of participants that we will enrol. Any future analyses on the effects of the intervention will include sample size and power calculations.

Data analysis

Quantitative analysis

We will collect data from all consenting participants who register to REACH over a 16-month period starting from the date REACH is launched at each site. Demographic and clinical information, system usage data and patient-participant survey responses will be reported using descriptive statistics. Continuous data will be reported as means, SD, medians and ranges, and categorical data will be reported as frequencies and percentages. For each implementation outcome, we will report the data on the total sample of participants and by geographical site and cancer type. Throughout the 16-month evaluation, interim analyses are planned (ie, every 4 months) to help identify and inform necessary changes to the REACH system and/or the implementation strategies used. Analyses will be performed with the R programming language.

Qualitative analysis

Each source of qualitative data including the patient-participant focus groups, clinical staff interviews, technical issues reported via the REACH email account and project meeting notes will be analysed separately and undergo the following process. First, the qualitative data will be anonymised by removing any identifying information such as names of individuals and places. The data will be subsequently entered into Dedoose (software to support data management and analysis) to assist with data management. A thematic analysis using a hybrid deductive and inductive approach will be conducted.41 The analysis will be guided by CFIR.21 42 The CFIR codebook template with pre-populated definitions and coding guidelines will be used to facilitate the analysis in Dedoose.43 To ensure the codebook is consistently applied during the analysis, two members of the team will independently code the first few interviews and focus groups and meet to clarify the codebook. Each remaining source of data will undergo a process of deductive coding by one independent coder and double-checked by a second. Both coders will continue to meet to provide an opportunity to discuss the data and ensure the data are provided with the appropriate codes. Following deductive coding, the coded data within each CFIR construct will undergo a process of inductive coding and these codes will then be categorised into themes. Descriptions of each theme will be created and representative quotes for each construct will be chosen.

Integration of quantitative and qualitative data

The quantitative and qualitative findings will be integrated using a triangulation protocol.44 Each set of data will be analysed separately as described above. The qualitative themes will be mapped to the implementation outcomes measured and their respective quantitative findings. Next, each outcome’s qualitative and quantitative findings will be reviewed for whether they agree with one another (convergence), partially agree (complimentary) or conflict (discrepancy or dissonance).

Patient and public involvement

We have partnered with the Canadian Cancer Survivor Network (CCSN), a national network of people living with and beyond cancer, caregivers and community partners who work to promote the delivery of effective support for people with cancer. The CanRehab team formed the PFAC, consisting of 13 representatives across Canada, including from each of the study’s four participating cancer centres. The PFAC has played a key advisory role throughout each phase of the REACH implementation project including assisting with the design of the REACH system, determining when and how to introduce REACH to patients at each centre and providing feedback on patient education materials to promote the system and facilitate the registration process. We will continue to engage the PFAC throughout this study by presenting study updates and seeking feedback on possible adaptations to the REACH system and/or implementation strategies.

Ethics and dissemination

Necessary approvals to implement REACH as a clinical tool for patients at each centre were obtained. Ethics approvals were obtained from the University Health Network (#22–5227) and all three additional institutions to study the implementation of REACH. Each of the four centres launched REACH and study recruitment began at the first centre in April 2023. Recruitment for all study activities across all four centres is expected to be completed in May 2025.

In addition to traditional knowledge translation activities (publication in open-access journals, conference presentations), we aim to develop relevant and engaging dissemination materials for various target audiences. The Communicating with Intent Framework45 will be used to tailor materials to each target audience (eg, cancer survivors, healthcare providers) by considering their prior knowledge, beliefs and barriers to engaging with the material and a tailored key message will be developed for each target audience by using the COMPASS Message Box, a science communication tool created to facilitate effective knowledge translation. A diverse list of mediums (eg, videos, infographics, news publications, evidence-based summaries, briefs) will be considered to ensure materials are accessible and reach specific audiences. All dissemination materials will have a co-design focus and feature input from the PFAC. We will leverage our partnership with CCSN to disseminate this information to people living with and beyond cancer through their social media platforms, webinars and newsletters. Additionally, we will partner with Wellspring, a Canada-wide non-profit organisation consisting of a network of programmes (many of which are provided on REACH), to disseminate these materials to people with cancer and organisations they have a formal partnership.

Discussion

The use of ePSMs in cancer has the potential to improve the identification and management of cancer-related impairments and improve the quality of life of people with cancer.7 8 However, there is a need for improved evidence regarding optimal implementation strategies for ePSMs in real-world clinical practice.15 This study will investigate the implementation of an ePSM for cancer rehabilitation, called REACH, into routine cancer care.

To date, most studies examining the use of an ePSM in cancer care have not applied an implementation science approach.9 This study uses an implementation science process model, the KTA cycle, which provides a structured approach for moving evidence-based interventions to routine practice.46 The KTA cycle has been widely applied and can be integral to the design, delivery and evaluation of the implementation of an evidence-based intervention.47 This study also uses several additional implementation science frameworks and tools. First, this study uses the ERIC taxonomy22 and the LISTS34 to describe the implementation strategies for REACH following the reporting and specification standards for implementation strategies.27 This may help advance the implementation of ePSMs by clarifying the individuals delivering the strategies, the duration and frequency of strategies and the implementation outcomes targeted by each strategy to maximise their measurement and reproducibility.27 Second, this study uses the implementation outcomes taxonomy27 and the RE-AIM framework40 to carefully select relevant outcomes. While some outcomes will be used to evaluate success via a priori targets (ie, feasibility, acceptability, appropriateness and fidelity), others, (eg, reach) will be solely used to provide valuable context and insight into the implementation process, offering a comprehensive understanding of how REACH was integrated into routine clinical care. Third, this study uses the CFIR,42 a widely used determinant framework that includes several constructs within five domains (characteristics of the innovation, inner setting, outer setting, characteristics of individuals and the process of implementation), to categorise barriers and facilitators to implementing REACH. Lastly, we will use the Implementation Research Logic Model (IRLM)48 to specify the implementation research elements across all the steps of the KTA cycle (ie, barriers and facilitators, implementation strategies, mechanisms of action and outcomes). The IRLM is a tool designed to improve the specification, rigour, reproducibility and testable causal pathways involved in implementation research projects. It provides a compact visual depiction of an implementation project and highlights the relationship between all implementation research elements.

Despite the single-arm design of this study, the use of these implementation science models, frameworks and tools may provide a better understanding of the steps taken to implement REACH and provide insight into how and why implementation was or was not successful. The results of this study will be used to guide refinements to the REACH system and the implementation strategies used to improve its implementation within the four participating centres. Future studies could build on this work to test the effectiveness of implementation strategies on various implementation outcomes. The findings from this current study may also be used to spread and scale this system to additional disease sites and centres in Canada, and aid in the adaptation to additional languages to extend its reach to a broader group of patients. If successfully implemented, REACH will provide patients with an evidence-based tool to support them in managing physical cancer-related impairments through early education and referral to cancer rehabilitation services.

Footnotes

Funding: This work was supported by funding from the Canadian Cancer Society and Canadian Institutes of Health Research Cancer Survivorship Team Grant (Grant Number: 706699 (CCS), 02022–000 (CIHR)).

Prepub: Prepublication history for this paper is available online. To view these files, please visit the journal online (https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2024-090449).

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient and public involvement: Patients and/or the public were involved in the design, or conduct, or reporting, or dissemination plans of this research. Refer to the Methods section for further details.

Contributor Information

Christian Lopez, Email: christian.lopez@uhn.ca.

Sarah E Neil-Sztramko, Email: neilszts@mcmaster.ca.

Kristin L Campbell, Email: kristin.campbell@ubc.ca.

David M Langelier, Email: David.langelier@albertahealthservices.ca.

Gillian Strudwick, Email: gillian.strudwick@camh.ca.

Jackie L Bender, Email: Jackie.Bender@uhn.ca.

Jonathan Greenland, Email: jonathan.greenland@easternhealth.ca.

Tony Reiman, Email: anthony.reiman@horizonnb.ca.

Jennifer M Jones, Email: jennifer.jones@uhn.ca.

ReferenceS

- 1.Fitch M, Zomer S, Lockwood G, et al. Experiences of adult cancer survivors in transitions. Supp Care Cancer. 2019;27:2977–86. doi: 10.1007/s00520-018-4605-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Queensland CC 1000 survivor study: a summary of cancer council Queensland’s survivor study results. 2016. https://cancerqld.org.au/wp- content/uploads/2016/06/executive-summary-survivor-study-report.pdf Available.

- 3.Molassiotis A, Yates P, Li Q, et al. Mapping unmet supportive care needs, quality-of-life perceptions and current symptoms in cancer survivors across the Asia-Pacific region: results from the International STEP Study. Ann Oncol. 2017;28:2552–8. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdx350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Beckjord EB, Reynolds KA, van Londen GJ, et al. Population-level trends in posttreatment cancer survivors’ concerns and associated receipt of care: results from the 2006 and 2010 LIVESTRONG surveys. J Psychosoc Oncol. 2014;32:125–51. doi: 10.1080/07347332.2013.874004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Stubblefield MD. The Underutilization of Rehabilitation to Treat Physical Impairments in Breast Cancer Survivors. PM&R . 2017;9:S317–23. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2017.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheville AL, Kornblith AB, Basford JR. An examination of the causes for the underutilization of rehabilitation services among people with advanced cancer. Am J Phys Med Rehabil. 2011;90:S27–37. doi: 10.1097/PHM.0b013e31820be3be. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alfano CM, Cheville AL, Mustian K. Developing High-Quality Cancer Rehabilitation Programs: A Timely Need. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2016;35:241–9. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_156164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Alfano CM, Pergolotti M. Next-Generation Cancer Rehabilitation: A Giant Step Forward for Patient Care. Rehabil Nurs. 2018;43:186–94. doi: 10.1097/rnj.0000000000000174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lopez CJ, Teggart K, Ahmed M, et al. Implementation of electronic prospective surveillance models in cancer care: a scoping review. Implement Sci. 2023;18:11. doi: 10.1186/s13012-023-01265-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basch E, Deal AM, Kris MG, et al. Symptom Monitoring With Patient-Reported Outcomes During Routine Cancer Treatment: A Randomized Controlled Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:557–65. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.63.0830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Basch E, Deal AM, Dueck AC, et al. Overall Survival Results of a Trial Assessing Patient-Reported Outcomes for Symptom Monitoring During Routine Cancer Treatment. JAMA. 2017;318:197–8. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.7156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Maguire R, McCann L, Kotronoulas G, et al. Real time remote symptom monitoring during chemotherapy for cancer: European multicentre randomised controlled trial (eSMART) BMJ. 2021;374:1647.:n1647. doi: 10.1136/bmj.n1647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Barbera L, Sutradhar R, Seow H, et al. Impact of Standardized Edmonton Symptom Assessment System Use on Emergency Department Visits and Hospitalization: Results of a Population-Based Retrospective Matched Cohort Analysis. JCO Oncol Pract . 2020;16:e958–65. doi: 10.1200/JOP.19.00660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Absolom K, Warrington L, Hudson E, et al. Phase III Randomized Controlled Trial of eRAPID: eHealth Intervention During Chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2021;39:734–47. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.02015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Di Maio M, Basch E, Denis F, et al. The role of patient-reported outcome measures in the continuum of cancer clinical care: ESMO Clinical Practice Guideline. Ann Oncol. 2022;33:878–92. doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2022.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howell D, Molloy S, Wilkinson K, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in routine cancer clinical practice: a scoping review of use, impact on health outcomes, and implementation factors. Ann Oncol. 2015;26:1846–58. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdv181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bennett AV, Jensen RE, Basch E. Electronic patient-reported outcome systems in oncology clinical practice. CA Cancer J Clin. 2012;62:337–47. doi: 10.3322/caac.21150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Stover AM, Haverman L, van Oers HA, et al. Using an implementation science approach to implement and evaluate patient-reported outcome measures (PROM) initiatives in routine care settings. Qual Life Res. 2021;30:3015–33. doi: 10.1007/s11136-020-02564-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Straus SE, Tetroe J, Graham ID. Knowledge translation in health care: moving from evidence to practice. 2nd. Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell; 2013. edn. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chokshi SK, Mann DM. Innovating From Within: A Process Model for User-Centered Digital Development in Academic Medical Centers. JMIR Hum Factors. 2018;5:e11048. doi: 10.2196/11048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Damschroder LJ, Aron DC, Keith RE, et al. Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Impl Sci. 2009;4:50. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-4-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Powell BJ, Waltz TJ, Chinman MJ, et al. A refined compilation of implementation strategies: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) project. Impl Sci. 2015;10:21. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0209-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lopez CJ, Jones JM, Campbell KL, et al. A pre-implementation examination of barriers and facilitators of an electronic prospective surveillance model for cancer rehabilitation: a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2024;24:17. doi: 10.1186/s12913-023-10445-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waltz TJ, Powell BJ, Matthieu MM, et al. Use of concept mapping to characterize relationships among implementation strategies and assess their feasibility and importance: results from the Expert Recommendations for Implementing Change (ERIC) study. Impl Sci. 2015;10:109. doi: 10.1186/s13012-015-0295-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palinkas LA, Aarons GA, Horwitz S, et al. Mixed Method Designs in Implementation Research. Adm Policy Ment Health . 2011;38:44–53. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0314-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pinnock H, Barwick M, Carpenter CR, et al. Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) Statement. BMJ. 2017;356:i6795. doi: 10.1136/bmj.i6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Proctor EK, Powell BJ, McMillen JC. Implementation strategies: recommendations for specifying and reporting. Implement Sci. 2013;8:139. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-8-139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Basch E, Artz D, Dulko D, et al. Patient online self-reporting of toxicity symptoms during chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:3552–61. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Snyder CF, Blackford AL, Wolff AC, et al. Feasibility and value of PatientViewpoint: a web system for patient-reported outcomes assessment in clinical practice. Psychooncol. 2013;22:895–901. doi: 10.1002/pon.3087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Weiner BJ, Lewis CC, Stanick C, et al. Psychometric assessment of three newly developed implementation outcome measures. Implementation Sci. 2017;12:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s13012-017-0635-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Creswell JW, Poth CN. Qualitative inquiry & research design: choosing among five approaches. 4th. Sage Publications; 2018. edn. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Weber MB. What Influences Saturation? Estimating Sample Sizes in Focus Group Research. Qual Health Res. 2019;29:1483–96. doi: 10.1177/1049732318821692. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hennink MM, Kaiser BN, Marconi VC. Code Saturation Versus Meaning Saturation: How Many Interviews Are Enough? Qual Health Res. 2017;27:591–608. doi: 10.1177/1049732316665344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Smith JD, Norton WE, Mitchell SA, et al. The Longitudinal Implementation Strategy Tracking System (LISTS): feasibility, usability, and pilot testing of a novel method. Impl Sci Commun. 2023;4:153. doi: 10.1186/s43058-023-00529-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Carroll C, Patterson M, Wood S, et al. A conceptual framework for implementation fidelity. Implement Sci. 2007;2:40. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-2-40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hasson H. Systematic evaluation of implementation fidelity of complex interventions in health and social care. Implement Sci. 2010;5:67. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Miller CJ, Barnett ML, Baumann AA, et al. The FRAME-IS: a framework for documenting modifications to implementation strategies in healthcare. Impl Sci. 2021;16:36. doi: 10.1186/s13012-021-01105-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Smith JD, Merle JL, Webster KA, et al. Tracking dynamic changes in implementation strategies over time within a hybrid type 2 trial of an electronic patient-reported oncology symptom and needs monitoring program. Front Health Serv. 2022;2:983217. doi: 10.3389/frhs.2022.983217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Proctor E, Silmere H, Raghavan R, et al. Outcomes for implementation research: conceptual distinctions, measurement challenges, and research agenda. Adm Policy Ment Health . 2011;38:65–76. doi: 10.1007/s10488-010-0319-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Glasgow RE, Harden SM, Gaglio B, et al. RE-AIM Planning and Evaluation Framework: Adapting to New Science and Practice With a 20-Year Review. Front Public Health. 2019;7:64. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2019.00064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Braun V, Clarke V. Thematic analysis. APA handbook of research methods in psychology. Washington: American Psychological Association; 2012. Vol 2: research designs: quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological; pp. 57–71. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Damschroder LJ, Reardon CM, Widerquist MAO, et al. The updated Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research based on user feedback. Implement Sci. 2022;17:75. doi: 10.1186/s13012-022-01245-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tools and templates - consolidated framework for implementation research. 2022. https://cfirguide.org/tools/tools-and-templates/ Available.

- 44.O’Cathain A, Murphy E, Nicholl J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ. 2010;341:bmj.c4587. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Barriault C, Reid M.The communicate with intent framework. Teaching science students to communicate: a practical guide .2023 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Graham ID, Logan J, Harrison MB, et al. Lost in knowledge translation: time for a map? J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2006;26:13–24. doi: 10.1002/chp.47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Field B, Booth A, Ilott I, et al. Using the Knowledge to Action Framework in practice: a citation analysis and systematic review. Implement Sci. 2014;9:172. doi: 10.1186/s13012-014-0172-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Smith JD, Li DH, Rafferty MR. The Implementation Research Logic Model: a method for planning, executing, reporting, and synthesizing implementation projects. Implement Sci. 2020;15:84. doi: 10.1186/s13012-020-01041-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]