Abstract

Myocyte Enhancer Factor 2C (MEF2C) is a transcription factor that plays a crucial role in neurogenesis and synapse development. Genetic studies have identified MEF2C as a gene that influences cognition and risk for neuropsychiatric disorders, including autism spectrum disorder (ASD) and schizophrenia (SCZ). Here, we investigated the involvement of MEF2C in these phenotypes using human-derived neural stem cells (NSCs) and glutamatergic induced neurons (iNs), which represented early and late neurodevelopmental stages. For these cellular models, MEF2C function had previously been disrupted, either by direct or indirect mutation, and gene expression assayed using RNA-seq. We integrated these RNA-seq data with MEF2C ChIP-seq data to identify dysregulated direct target genes of MEF2C in the NSCs and iNs models. Several MEF2C direct target gene-sets were enriched for SNP-based heritability for intelligence, educational attainment and SCZ, as well as being enriched for genes containing rare de novo mutations reported in ASD and/or developmental disorders. These gene-sets are enriched in both excitatory and inhibitory neurons in the prenatal and adult brain and are involved in a wide range of biological processes including neuron generation, differentiation and development, as well as mitochondrial function and energy production. We observed a trans expression quantitative trait locus (eQTL) effect of a single SNP at MEF2C (rs6893807, which is associated with IQ) on the expression of a target gene, BNIP3L. BNIP3L is a prioritized risk gene from the largest genome-wide association study of SCZ and has a function in mitophagy in mitochondria. Overall, our analysis reveals that either direct or indirect disruption of MEF2C dysregulates sets of genes that contain multiple alleles associated with SCZ risk and cognitive function and implicates neuron development and mitochondrial function in the etiology of these phenotypes.

Author summary

Schizophrenia is a complex disorder caused by many genes. Current drugs for schizophrenia are only partially effective and do not treat cognitive deficits, which are key factors for explaining disability, leading to unemployment, homelessness and social isolation. Large-scale genetic studies of schizophrenia and cognitive function have been effective at identifying individual SNPs and genes that contribute to these phenotypes but have struggled to immediately uncover the bigger picture of the underlying biology of the disorder. Here we take an individual gene associated with schizophrenia and cognitive function called MEF2C, which on its own is a very important regulator of brain development. We use functional genomics data from studies where MEF2C has been mutated to identify sets of other genes that are influenced by MEF2C in developing and mature neurons. We show that several of these gene-sets are enriched for common variants associated with schizophrenia and cognitive function, and for rare variants that increase risk of various neurodevelopmental disorders. These gene-sets are involved in neuron development and mitochondrial function, providing evidence that these biological processes may be important in the context of the molecular mechanisms that underpin schizophrenia and cognitive function.

Introduction

MEF2C, a transcription factor within the myocyte enhancer factor-2 (MEF2) family, is involved in essential neurodevelopmental processes [1]. MEF2C is expressed during the initial stages of embryonic brain development and remains expressed at elevated levels in adult brains, including in the striatum, hippocampus, and cortex, indicating an involvement in both embryonic and adult brain activity [1,2]. MEF2C plays a critical role in neurogenesis, neuronal distribution and electrical activity in the neocortex [3–5]. Mutations in the MEF2C gene, including microdeletions, missense, or nonsense mutations, have been linked to a rare genetic disorder known as MEF2C haploinsufficiency syndrome. This syndrome is characterized by intellectual disability (ID), epilepsy, and additional autistic features like absent speech and impaired social interactions [6]. Genome-wide association studies (GWAS) have identified common variants in the MEF2C gene that are associated with schizophrenia (SCZ) intelligence (IQ) and educational attainment (EA) [7–9]. MEF2C is associated with genetic and epigenetic risk architectures of SCZ [10]. MEF2C motifs were present among the top-scoring single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with SCZ in GWAS and deep sequencing of histone methylation landscapes in individuals with SCZ and controls revealed a significant abundance of MEF2C motifs associated with histone hypermethylation in the disorder. Additionally, the upregulation of MEF2C improved working memory, object recognition memory, and spinal remodeling in prefrontal projection neurons in mice [10].

Various studies have utilized MEF2C heterozygous or homozygous knockout (KO) animal models to investigate the role of MEF2C in brain function and to identify molecular mechanisms underlying human phenotypes associated with MEF2C [3,11–15]. Recently, Mohajeri et al. (2022) evaluated MEF2C loss-of-function mutations in human-derived cell lineages representing different stages of neural development [16]. They directly disrupted the gene by targeting the coding sequence of MEF2C with CRISPR-engineered mutations, resulting in 122kb and 131kb deletions of the gene. Expanding beyond direct disruption of the gene, they utilized an indirect approach to disrupt the 3D genome organization of the locus and the regulatory architecture of the gene. Here, they either deleted the distal boundary (DB) or the proximal boundary (PB) of the topologically associated domain (TAD) encompassing MEF2C. Specifically, they performed a targeted deletion of a 3.3kb segment of the DB, which targeted a single occupied CTCF binding site located more than 1.3Mb distal to the MEF2C promoter. As for the PB, they carried out a targeted deletion of a single occupied CTCF binding site within a 3’ intron of MEF2C. Following the direct or indirect mutation of MEF2C in human induced pluripotent stem cells (iPSCs), these cells were differentiated into neural stem cells (NSCs) and glutamatergic induced neurons (iNs) as cellular models [16]. NSCs are undifferentiated cells that have the ability to self-renew and generate various types of neurons and glial cells. Glutamatergic iNs are responsible for synthesizing glutamate, the primary excitatory neurotransmitter in the mammalian central nervous system. Glutamate plays a crucial role in various essential brain processes, including cognition, learning, memory, and sensory perception [17]. The study used these cellular models to investigate the impact of both direct and indirect disruptions of MEF2C on global transcriptional signatures and electrophysiological changes in human neurons [16]. Both the direct disruption and the loss of a PB, but not the deletion of a DB, led to down-regulation of MEF2C expression, which resulted in reduced synaptic activity. The presence of common differentially expressed genes (DEGs) associated with neurogenesis and neuronal differentiation in both direct and indirect MEF2C disruptions suggests shared functional consequences arising from both types of MEF2C disruption [16].

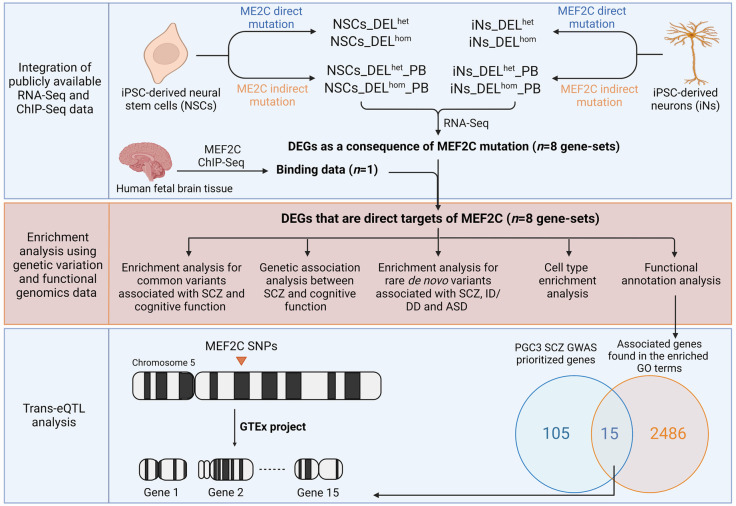

Here, we expanded upon the findings of Mohajeri et al. (2022) [16] by utilizing their gene expression data and combining it with chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing (ChIP-seq) data for MEF2C (Fig 1) [18]. This integration enabled us to identify putative direct transcriptional targets of MEF2C in both NSCs and iNs that were dysregulated following either heterozygous or homozygous direct or indirect mutation of the gene. Given MEF2C’s association with neuropsychiatric disorders and cognitive function, we sought to investigate if the direct targets of MEF2C that are dysregulated by different mutations in the different cellular models are enriched for genes containing SNPs associated with SCZ and cognitive function from GWAS, as well as enriched for genes harboring rare de novo mutations (DNMs) contributing to neurodevelopmental disorders. Subsequently, we investigated the biological processes and specific cell types that are dysregulated as a consequence of MEF2C disruption to better understand the contribution of MEF2C-regulated genes to the molecular mechanisms of SCZ and cognition. Finally, we sought to identify trans-expression quantitative trait loci (trans-eQTL) at the MEF2C gene that are associated with altered expression of downstream MEF2C target genes (Fig 1).

Fig 1. Schematic representation illustrating the stepwise methodology employed in this study.

DELhom: Homozygous deletion; DELhet: Heterozygous deletion; PB: Proximal boundary (indirect mutation of MEF2C); DEGs: Differentially expressed genes; SCZ: Schizophrenia; ID: Intellectual disability; DD: Developmental delay; ASD: Autism spectrum disorder; GO: Gene ontology; PGC: Psychiatric Genomics Consortium; GWAS: Genome-wide association study; SNPs: Single nucleotide polymorphisms; eQTL: Expression quantitative trait loci; GTEx: Genotype-Tissue Expression. Figure created with BioRender.com.

Materials and methods

Ethics statement

Data were directly downloaded from published studies and no additional ethics approval was needed. Each study is referenced and details on ethics approval are available in each manuscript.

MEF2C Transcriptomic data

We utilized transcriptomic data generated in a study of MEF2C conducted by Mohajeri et al. (2022) [16]. That study used dual-guide CRISPR-Cas9 genome editing to directly (deletion in the coding region) or indirectly (mutation of the PB of the TAD that encompasses MEF2C) disrupt MEF2C function in human iPSCs. Single cells were isolated and screened to identify edited clones and matched unedited controls. Six replicates per genotype (heterozygous (het) or homozygous (hom) deletion (DEL)) were then differentiated into NSCs and iNs and subjected to RNA-seq analysis. This analysis generated eight sets of differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in these cellular models, labelled as follows with PB denoting the indirect mutation: NSCs_DELhet, NSCs_DELhom, NSCs_DELhet_PB, NSCs_DELhom_PB, iNs_DELhet, iNs_DELhom, iNs_DELhet_PB, and iNs_DELhom_PB. Each gene-set represented a different combination of MEF2C disruption and genotype in NSCs or iNs. The significant DEGs were identified at FDR < 0.1 (S1 Table).

MEF2C ChIP-sequencing data analysis

To investigate MEF2C binding, we utilized existing ChIP-seq data from a study of MEF2C conducted on human fetal brain cultures [18]. Input DNA was used as a control. The raw files, comprising a single replicate, were provided by the authors. The quality of the raw FastQ files was assessed using the FastQC (http://bioinformatics.babraham.ac.uk/projects/fastqc/). Reads were aligned to the human genome (hg19) using Burrows Wheeler Aligner (BWA; http://bowtie-bio.sourceforge.net/bowtie2) [19]. Post-processing of the alignment data was conducted using Samtools (https://github.com/samtools). We converted the SAM files to BAM format, sorted the BAM files, removed any potential PCR duplicates and generated a file containing mapping statistics [20]. Peaks were called using MACS2 (parameters: -f BAM -g hg -q 0.01) [21]. ChIPSeeker was used to determine overlap with genomic features and for peak annotation to the nearest genes [22].

Integrative Analysis of RNA-Seq and ChIP Data

To infer the direct target genes of MEF2C, the eight sets of DEGs described above were integrated with the MEF2C ChIP-seq data using the BETA (Binding and Expression Target Analysis) (http://cistrome.org/BETA/) package software [23]. BETA ranks genes based on two key factors: the regulatory potential of factor binding sites and the differential expression observed upon factor binding. The regulatory potential is assessed by considering the distance of the binding sites from the transcription start site and the cumulative impact of multiple binding sites. By considering both aspects, a rank product (RP) was calculated for each gene, which can be interpreted as a probability, indicating the likelihood that a gene is a true direct target of MEF2C based on both criteria. Genes with a conservative RP < 0.01 were considered as direct targets of MEF2C (S2 Table).

Stratified linkage disequilibrium score regression (sLDSC) Analysis

Stratified linkage disequilibrium score regression (sLDSC) (https://github.com/bulik/ldsc) [24] was used to investigate if the MEF2C direct targets were enriched for heritability contributing to SCZ, IQ, and EA phenotypes. GWAS summary statistics for these phenotypes [7–9] were obtained from publicly available databases (the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium Website www.med.unc.edu/pgc, the Complex Trait Genetics lab www.ctg.cncr.nl/, and the Social Science Genetic Association Consortium www.thessgac.org/data). For control purposes, we performed sLDSC analysis using GWAS summary statistics for an additional four phenotypes, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) [25], obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD)[26], Alzheimer’s disease (AD) [27] and stroke [28]. Linkage disequilibrium (LD) scores between SNPs were estimated using the 1000 Genomes Phase 3 European reference panel. SNPs present in HapMap 3 with an allele frequency > 0.05 were included. Enrichment of heritability was assessed controlling for the effects of 53 functional annotations included in the full baseline model version. Enrichment for heritability was compared to the baseline model using the Z-score to derive a (one-tailed) P-value. Significant enrichments were determined using a Bonferroni correction, which set the corrected P value threshold at < 2.08E-03.

Overlapping Genes Implicated in the GWAS of SCZ and IQ/EA

In the GWAS of IQ, 1,016 genes were reported as associated with IQ through positional mapping, eQTL mapping, chromatin interaction mapping and gene-based association analysis [8]. For EA, 1,838 genes were prioritized using Data-driven Expression Prioritized Integration for Complex Traits (DEPICT), which was based on correlations across reconstituted gene-sets [9]. For SCZ, 682 associated genes were identified through fine mapping and summary-data-based mendelian randomization [7] (S3 Table). To investigate distinct and overlapping associations with SCZ and cognitive function, we identified genes that are associated with SCZ but not IQ or EA (n = 472), genes that are associated with at least one of the cognitive phenotypes (IQ or EA) but not SCZ (n = 2,258) and genes that are associated with both SCZ and at least one of the cognitive phenotypes (IQ or EA; n = 210).

Gene-set based polygenic risk score (PRS)

PRSice-2 software [20] was utilized for gene-set based PRS analysis aiming to investigate whether the MEF2C target gene-sets contributed to the shared genetic basis of SCZ and cognitive traits. PRSice-2 calculates PRS for each individual by summing up the number of minor alleles at each SNP multiplied by the GWAS effect size. It performs regression analysis, adjusting for sex, age, and GWAS array type as covariates, and provides performance metrics (Nagelkerke’s R2 and P value). SNP P values and effect sizes for SCZ were derived from a SCZ GWAS meta-analysis on 40,675 cases and 64,643 controls [7]. Irish samples were excluded from this GWAS to keep that base/discovery sample independent from the target/test sample for the PRS analysis. The SNP P values and effect sizes for IQs were based on an IQ GWAS on 269,867 individuals [8]. For each gene-set, SNPs in high LD were clumped according to PRSice-2 guidelines. Genotype data for the identified SNPs were extracted from the full GWAS data of the Irish samples, which consisted of 1,512 individuals, including SCZ patients and controls with IQ measurements [29,30]. Effect-size weighted SCZ-PRS and IQ-PRS were computed for each gene-set using thresholds ranging from P < 0.05 to P≤1 (P < 0.05, 0.1, 0.15, 0.2, 1). To validate the findings, 10,000 randomized phenotypes (equally distributed cases and controls as per the original dataset) were generated from the Irish samples, and SCZ-PRS and IQ-PRS were calculated for each gene-set using the randomized data to obtain empirical P values.

Analysis of De Novo Mutations

The R package denovolyzeR (http://denovolyzer.org/) was used to test for enrichment of rare de novo mutations (DNMs) in our gene-sets, estimating the expected number of DNMs for each gene based on sequence context and gene size [31]. Synonymous (Syn), missense (Mis), and loss of function (Lof) (including nonsense, frameshift, and splice) DNMs reported in exome sequencing studies of SCZ (n = 3447 trios) [32–35], ASD (n = 6430 trios) [36], and ID and/or DD (n = 4,851 trios) [37–40] and unaffected siblings (n = 1,995) [32]. S4 Table provides details about each study along with the respective table names listing the identified DNMs. To ensure consistency with the Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study (2017), we applied a filtering step for DNMs. Specifically, DNMs with a posterior probability score below 0.00781 were excluded. Enrichment of DNMs in a gene-set was investigated using a two-sample Poisson rate ratio test, using the ratio of observed to expected DNMs in genes outside of the gene-set as a background model. Significant enrichments were determined using a Bonferroni correction, which set the corrected P value threshold at < 5.21E-04.

MEF2C Direct Target Genes Analysis with Single-cell RNA-seq

The Expression Weighted Cell-type Enrichment (EWCE) R package (https://github.com/NathanSkene/EWCE) was used to assess if the direct target genes of MEF2C had higher expression in a particular cell type than expected by chance [41]. This method generates random gene sets (n = 100,000) of equal length from background genes to estimate the probability distribution. We performed enrichment analysis in a prenatal human dataset and in an adult human dataset. The prenatal human dataset included single-nuclei RNA sequencing (snRNA-seq) data from three fetuses from the second trimester of gestation and contained data for 91 distinct clusters of nuclei from five brain regions (frontal cortex (FC), ganglionic eminence (GE), hippocampus (Hipp), thalamus (Thal), and cerebellum (Cer)) [42]. The adult human dataset included data for 120 distinct clusters of nuclei from across the human cortex covering the middle temporal gyrus (MTG), cingulate gyrus (CgG), primary visual cortex (V1C), primary somatosensory cortex (S1C) and the primary motor cortex (M1C). Nuclei were sampled from postmortem and neurosurgical (MTG only) donor brains (https://portal.brain-map.org/atlases-and-data/rnaseq/protocols-human-cortex) [43,44]. The significance of the enriched expression of the MEF2C direct target genes relative to the background genes in each cell type was assessed by calculating the difference in standard deviations between the two expression profiles. Statistically significant enrichments were determined using a Bonferroni correction to adjust for multiple testing of cell types.

Functional enrichment analysis

ClueGO (version 2.5.9), a plugin for Cytoscape (version 3.8.2) was used to identify the Gene Ontology (GO) terms (categorized as biological processes (BP), molecular functions (MF), and cellular components (CC)) and the biological pathways (KEGG, Reactome, WikiPathways) enriched for (i) genes proximal to MEF2C peaks identified via ChIP-seq analysis using brain tissue-expressed genes as the background gene-set (S5 Table) [45] and (ii) the MEF2C direct target gene-sets using specific cell-type expressed genes as the background gene-set. Brain tissue-expressed genes were obtained directly from the Human Protein Atlas database (https://www.proteinatlas.org/) [46]. Cell type-specific expressed genes were identified by calculating Transcripts Per Million (TPM) values from raw reads counts of wild type NSCs and iNs downloaded from the gene expression omnibus (GEO GSE204778). Genes with TPM values less than 1 were filtered out. GO term relationships were determined based on shared genes and assessed using chance-corrected kappa statistics. Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust for multiple testing.

Results

Identification and Annotation of MEF2C Binding Peaks

Analysis of ChIP-Seq data using MACS and ChIPSeeker identified 10,620 MEF2C binding peak regions (FDR ≤ 1%) across the entire genome. Approximately 80% of the peaks were located in close proximity to gene-encoding regions including promoters (< = 1-kb (55.8%), 1–2 kb (2.35%), 2–3 kb (1.99%)), 5’ UTRs and 3’ UTRs (0.44%), exons (0.18%), first introns (5.8%), and other intron regions (14.8%) (S6 Table). When the binding peaks were mapped to the closest RefSeq annotated transcripts, they were found in close proximity to 5,775 protein coding genes. GO annotation analysis showed these genes were most involved in RNA binding, transcription and functions within the nucleus (S7 Table).

Identification of MEF2C Direct Target Genes

We integrated MEF2C ChIP-seq data with data on DEGs from cell line models where MEF2C had been mutated (2 cell types (NSCs or iNs) x 2 DEL mutation types (direct or indirect (PB)) x 2 genotypes (het or hom) = 8 cell line models). Fig 1 illustrates the stepwise methodology employed in this study, from generating the eight gene-sets from these models through to enrichment analysis using genetic variation and functional genomics data. We identified that MEF2C had a direct regulatory influence on approximately 23–57% of the DEGs from the original study (Table 1). Shared MEF2C direct target genes were observed between different genotypes within the same cell type in both NSCs and iNs. In NSCs, the proportion of shared genes for both heterozygous and homozygous genotypes ranged from 37% (direct mutation) to 42% (indirect mutation), while in iNs, it ranged from 23% (direct mutation) to 34% (indirect mutation) (S1 Fig). Furthermore, there was a limited number of common MEF2C direct target genes found for the same genotype across different gene disruption types, ranging from 13% (homozygous) to 22% (heterozygous) in NSCs and from 8% (homozygous) to 18% (heterozygous) in iNs (S1 Fig). A small fraction of the MEF2C direct target genes (3% in NSCs and 1.4% in iNs) were in each gene-set (S1 Fig), indicating that the downstream effect of different gene mutations and their genotypic state is to mostly impact distinct sets of genes.

Table 1. Number of DEGs in each gene-set before and after the integration with MEF2C ChIP-seq data to identify direct target genes.

| Gene-Set | # of all DEGs | # of MEF2C Direct Targets (% of MEF2C Direct Targets relative to all DEGs) |

|---|---|---|

| NSCs | ||

| DELhet | 366 | 169 (46%) |

| DELhom | 2187 | 1170 (53%) |

| DELhet_PB | 492 | 240 (49%) |

| DELhom _PB | 728 | 412 (57%) |

| iNs | ||

| DELhet | 689 | 335 (51%) |

| DELhom | 291 | 145 (50%) |

| DELhet_PB | 2980 | 1034 (35%) |

| DELhom _PB | 5132 | 1174 (23%) |

NSCs: Neural stem cells; iNs: Induced neurons; DELhom: Homozygous deletion; DELhet: Heterozygous deletion; PB: Proximal boundary (indirect mutation of MEF2C).

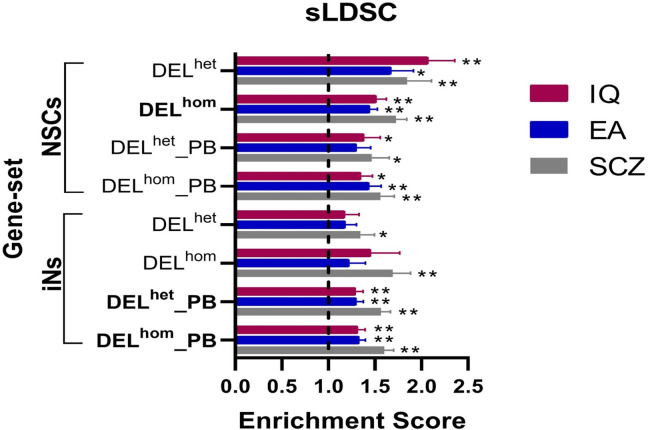

Enrichment analysis for genes containing common variants

We performed sLDSC analysis to investigate if the MEF2C direct target gene-sets are enriched for genes containing common genetic variants associated with SCZ risk or cognitive ability [7–9]. Six of the eight gene-sets were significantly enriched for heritability contributing to at least one of the studied phenotypes (SCZ, IQ, and/or EA) (Fig 2). Specifically, three gene-sets (NSCs_DELhom, iNs_DELhet_PB, and iNs_DELhom_PB) were significantly enriched for all phenotypes after multiple testing correction (Fig 2 and S8 Table). These findings highlight the potential role of MEF2C in regulating genes involved in SCZ and cognitive function. When we removed genes associated with SCZ from the enrichment analysis of IQ and EA, we saw that the majority of enriched gene-sets remained significant. When we removed genes associated with IQ or EA from the enrichment analysis of SCZ, we saw that only the enrichment of the NSCs_DELhom gene-set remained significant (S9 Table). This suggests that some MEF2C target genes are contributing to both SCZ and cognitive phenotypes while others are more phenotype specific. No significant enrichment was detected for any of the four control phenotypes (S10 Table).

Fig 2. Results from sLDSC analysis of MEF2C direct target gene-sets using GWAS data.

The graph plots the enrichment values, defined as the ratio of heritability (h2) to the number SNPs, on the x-axis. The error bars represent the standard errors. Two asterisks (**) indicate significance after Bonferroni correction, and one asterisk (*) indicates nominal significance. Gene-sets enriched for the three phenotypes are highlighted in bold. NSCs: Neural stem cells; iNs: induced neurons; DELhom: Homozygous deletion; DELhet: Heterozygous deletion; PB: Proximal Boundary.

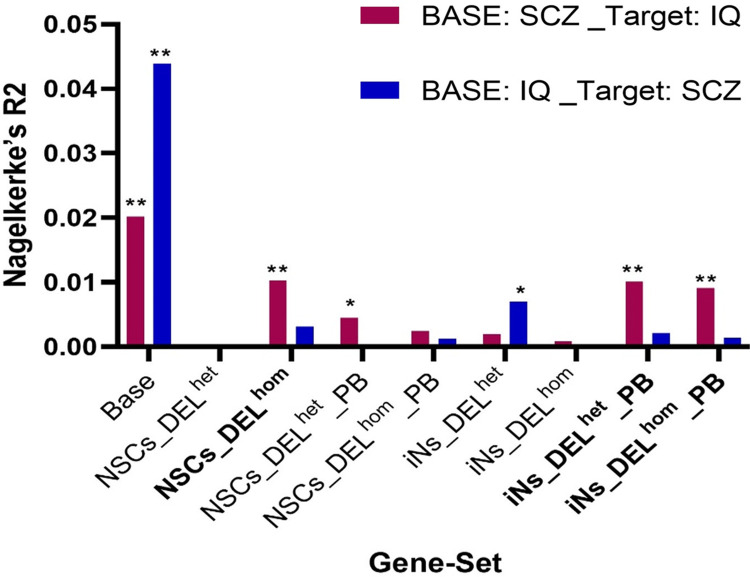

Genetic Association between SCZ and cognitive function

To explore the genetic overlap between these phenotypes further, gene-set based PRS analysis was conducted to investigate if the MEF2C target gene-sets contributed to the shared genetic etiology between SCZ and cognition. This was done by generating a gene-set PRS based on SCZ risk from GWAS and testing if this SCZ-PRS could explain variance in IQ in an independent dataset. We also tested if a gene-set IQ-PRS could predict SCZ case-control status in independent dataset. While the IQ-PRS could not predict SCZ case-control status, we found that the SCZ-PRS derived from three of the eight gene-sets (NSCs_DELhom, iNs_DELhet_PB, and iNs_DELhom_PB) could explain a significant proportion of variance in IQ (Fig 3 and S11 Table). These are the same three gene-sets that were previously enriched for common variation associated with SCZ, IQ and EA. When we removed genes associated with IQ or EA from these gene-sets, these three SCZ-PRSs could still explain variance in IQ in an independent dataset at levels that were nominally significant (S12 Table). These findings suggest that genetic variants associated with SCZ within these gene-sets also influence cognitive performance and the effect was not just due to genes already associated with IQ or EA. We performed a sensitivity analysis with respect to the p-value threshold for SNP inclusion and found that results were consistent and stable across different p-value thresholds (S11 and S12 Tables).

Fig 3. Gene-set based PRS analysis to examine associations between the SCZ-PRS and IQ, and between the IQ-PRS and SCZ.

Base on the x-axis refers to a PRS generated using all variants in the genome. The height of the columns on the y-axis indicates the proportion of variance in the phenotype explained when a gene-set based PRS is constructed using SCZ GWAS data and is tested against IQ (pink columns) or when a gene-set based PRS is constructed using IQ GWAS data and is tested against SCZ case-control status (blue columns). Two asterisks (**) indicate significance after Bonferroni correction, and one asterisk (*) indicates nominal significance. NSCs: Neural stem cells; iNs: induced neurons; DELhom: Homozygous deletion; DELhet: Heterozygous deletion; PB: Proximal Boundary.

Enrichment Analysis for Genes Containing De Novo Mutations

To assess the impact of rare variants within the MEF2C gene-sets on SCZ and other neurodevelopmental disorders where cognitive impairment is a major feature (ASD, ID and DD), we examined whether these gene-sets exhibited enrichment for Syn, Mis, and Lof DNMs in trio-based exome sequencing studies of these disorders [32–40]. The same gene-sets that showed enrichment for common variants associated with SZ, IQ and EA (NSCs_DELhom, iNs_DELhet_PB, and iNs_DELhom_PB) were also significantly enriched for genes containing Lof and/or Mis DNMs reported specifically in ID and/or DD patients after multiple test correction (Table 2). The NSCs_DELhom gene-set was also significantly enriched for Lof DNMs found in people with autism (Tables 2 and S13). None of our gene-sets showed enrichment for genes containing rare DNMs reported in SCZ patients. As a control, our gene-sets were not enriched for Syn DNMs reported for these disorders and not enriched for any class of DNM reported in the unaffected siblings of patients.

Table 2. Rare variant enrichment analysis of MEF2C direct target gene-sets using data on DNMs, identified in patients with SCZ, ASD, ID and DD.

| Gene-Set | SCZ n = 3394 trios |

ASD n = 6430 trios |

ID/DD n = 4485 trios |

Unaffected Siblings n = 1995 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NSCs | ||||

| DELhet | ns | ns | ns | ns |

| DELhom | ns | Lof** | Mis**, Lof** | ns |

| DELhet_PB | ns | Lof* | ns | ns |

| DELhom _PB | ns | Lof* | Mis | ns |

| iNs | ||||

| DELhet | ns | ns | Mis* | ns |

| DELhom | Syn* | ns | Mis*, Lof* | ns |

| DELhet_PB | ns | ns | Mis** | ns |

| DELhom _PB | Lof* | Mis*, Lof* | Mis**, Lof** | ns |

Two asterisks (**) indicate significant enrichment for mutation type after Bonferroni correction, one asterisk (*) indicates significant enrichment for mutation type at nominal significance level and ns indicates non-significant for all classes of mutation tested. SCZ: Schizophrenia; ASD: Autism spectrum disorder; ID: Intellectual disability; DD: Developmental delay; Syn: Synonymous mutations, Mis: Missense mutations; Lof: Loss-of-function mutations; NSCs: Neural stem cells; iNs: Induced neurons; DELhom: Homozygous deletion; DELhet: Heterozygous deletion; PB: Proximal boundary (indirect mutation of MEF2C).

Cell-type enrichment analysis

We utilized the EWCE R package [41] to investigate which individual cell types are enriched for these genes in the prenatal and adult human brain using snRNA-seq data. The three gene-sets with by far the most enriched cell types are the three gene-sets that were enriched for common variation associated with SCZ, IQ and EA and rare DNMs reported in neurodevelopmental disorders (NSCs_DELhom, iNs_DELhet_PB and iNs_DELhom_PB). There is a consistent pattern for these gene-sets in the prenatal and adult data with both glutamatergic excitatory neurons and GABAergic inhibitory neurons enriched across different regions of the prenatal brain and across regions of the adult cortex (S14 and S15 Tables). The enrichment of genes in both excitatory and inhibitory neurons is consistent with the role of MEF2C in regulating the balance of excitatory and inhibitory synapses, the disruption of which may contribute to neurodevelopmental disease [11]. Lastly, the NSCs_DELhom gene-set was enriched within cycling progenitor cells and intermediate progenitor cells within the prenatal brain, which like the NSCs can produce new types of neurons and glial cells (S14 Table).

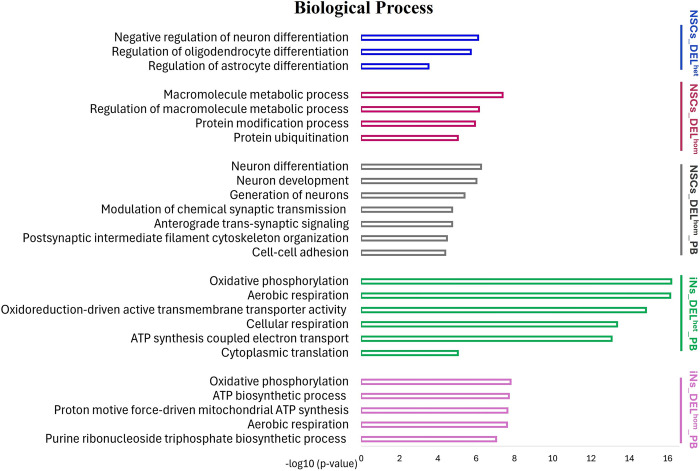

Functional enrichment analysis

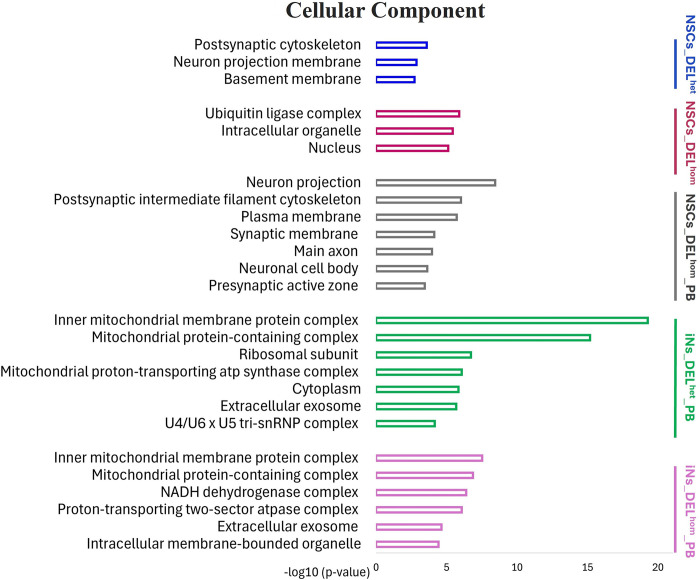

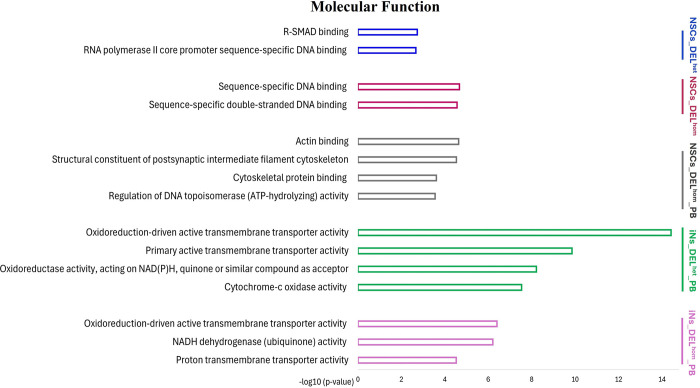

ClueGO (version 2.5.9), a plugin for Cytoscape (version 3.8.2) was used to investigate if genes within the eight sets are over-represented in similar or distinct GO terms for biological processes, cellular components and molecular functions, and biological pathways, using specific cell-type expressed genes as the background gene-set. The NSCs gene-sets were enriched for GO terms related to neuron development, regulation of neuron and glial cell differentiation and regulation of metabolic processes (Figs 4–6 and S16–S19 Tables). The iNs gene-sets were enriched for GO terms related to mitochondrial function and energy production, including the oxidative phosphorylation process (Figs 4–6 and S20–S23 Tables). KEGG pathway analysis revealed that the NSCs gene-sets were enriched in pathways including Orexin receptor pathway, Protein processing in endoplasmic reticulum and Aerobic glycolysis, while the iNs gene-sets were enriched in pathways including The citric acid (TCA) cycle and respiratory electron transport and Oxidative phosphorylation (S16–S23 Tables). The enriched GO terms following disruption of MEF2C are distinct from those observed earlier from the ChIP-seq binding pattern of MEF2C in the absence of any gene disruption.

Fig 4. Bar charts of gene ontology (GO) analysis of biological process for MEF2C direct target gene-sets using the ClueGo plugins of Cytoscape.

The Bonferroni method was applied for a p-value correlation (p < 0.05). The vertical axis displays the names of the GO terms. The horizontal axis and bar lengths represent the significance [−log10 (p-value)]. Colors in the bars represent different MEF2C direct target gene-sets. Results are presented only for the five gene-sets that were previously enriched for common variation associated with SCZ, IQ and/or EA. Enriched terms that were related to each other in the ontology were grouped together, with the most significant term(s)/group displayed. All data is detailed in S16–S23 Tables. NSCs: Neural stem cells; iNs: induced neurons; DELhom: Homozygous deletion; DELhet: Heterozygous deletion; PB: Proximal Boundary.

Fig 6. Bar charts of gene ontology (GO) analysis of cellular component for MEF2C direct target gene-sets using the ClueGo plugins of Cytoscape.

The Bonferroni method was applied for a p-value correlation (p < 0.05). The vertical axis displays the names of the GO terms. The horizontal axis and bar lengths represent the significance [−log10 (p-value)]. Colors in the bars represent different MEF2C direct target gene-sets. Results are presented only for the five gene-sets that were previously enriched for common variation associated with SCZ, IQ and/or EA. Enriched terms that were related to each other in the ontology were grouped together, with the most significant term(s)/group displayed. All data is detailed in S16–S23 Tables. NSCs: Neural stem cells; iNs: induced neurons; DELhom: Homozygous deletion; DELhet: Heterozygous deletion; PB: Proximal Boundary.

Fig 5. Bar charts of gene ontology (GO) analysis of molecular function for MEF2C direct target gene-sets using the ClueGo plugins of Cytoscape.

The Bonferroni method was applied for a p-value correlation (p < 0.05). The vertical axis displays the names of the GO terms. The horizontal axis and bar lengths represent the significance [−log10 (p-value)]. Colors in the bars represent different MEF2C direct target gene-sets. Results are presented only for the five gene-sets that were previously enriched for common variation associated with SCZ, IQ and/or EA. Enriched terms that were related to each other in the ontology were grouped together, with the most significant term(s)/group displayed. All data is detailed in S16–S23 Tables. NSCs: Neural stem cells; iNs: induced neurons; DELhom: Homozygous deletion; DELhet: Heterozygous deletion; PB: Proximal Boundary.

Trans expression quantitative trait loci analysis

We hypothesized that genetic variation at MEF2C (associated with SCZ, IQ or EA) could indirectly affect expression of a downstream target gene, mediated through MEF2C’s role as a transcription factor. This would be a trans expression quantitative trait loci (eQTL) effect and evidence of two risk genes (i.e., MEF2C and a downstream target gene) functioning within a putative risk pathway. To reduce the number of possible tests of target genes, we first restricted this analysis to the five gene-sets that were enriched for association with at least one of SCZ, IQ or EA. We next limited these MEF2C direct target genes to only those in significantly enriched GO terms (to capture genes with relevant functions; S24 Table) and to those genes among the 120 genes prioritized in the latest GWAS for SCZ (S25 Table) [7]. These 120 genes were identified through a combination of fine-mapping, transcriptomic analysis and functional genomic annotations [7]. The GWASs of IQ and EA had not performed similar prioritization analysis and each reported >1,000 associated genes. Fifteen of the 120 genes are MEF2C direct target genes that were in the enriched GO terms (S26 Table). We took 10 LD-independent SNPs at MEF2C that were associated with SCZ, EA, and IQ at genome-wide significant levels (S27 Table) and investigated their association with the expression levels of these fifteen genes using eQTL data obtained from the Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project (https://gtexportal.org/home/) [47]. We detected a trans eQTL for a single SNP at MEF2C (rs6893807; associated with IQ in GWAS) on the expression of the SCZ risk gene BNIP3L in the cerebellar hemisphere following multiple testing correction (P = 1.60E-05, adjusted P = 0.025). The BNIP3L gene is known to be involved in mitophagy, a process responsible for the selective removal of damaged mitochondria. Finally, to further explore genes with mitochondrial functions beyond the 120 prioritized SCZ genes, we performed a second trans eQTL analysis. This time we restricted the target genes to those within enriched GO terms related to mitochondrial function and energy production that had cell-type specific expression in the enriched cell-types from that earlier analysis. As a result, we tested the 10 LD-independent SNPs at MEF2C against 300 genes. Overall, the trans eQTL effect on the expression of BNIP3L, already detected, was the only finding that survived multiple test correction (S28 Table).

Discussion

The present study aimed to integrate transcriptomic data from human neural cell models of MEF2C deletion with ChIP-seq data to identify the direct regulatory influence of MEF2C disruption on global transcriptional signatures. These data from models of early neuronal development stem cells (NSCs) and fully differentiated neurons (iNs) provide insight into the sets of genes downstream of MEF2C that may be important for brain function at different stages of neurodevelopment. Common variants in MEF2C are associated with SCZ and cognitive function. We do not expect these sets of downstream dysregulated genes to directly align with the molecular mechanisms of SCZ and cognitive function. But we have been able to interrogate these gene sets to determine if they were enriched for other genes associated with these phenotypes or other neurodevelopmental disorders. From there, we investigated the functionality of the genes within these sets to generate evidence that supports existing hypotheses about the molecular basis of SCZ.

All eight gene-sets were significantly enriched for genes associated with at least one phenotype but three gene-sets (NSCs_DELhom, iNs_DELhet_PB, and iNs_DELhom_PB) were enriched for common variants associated with SCZ, IQ and EA and were further enriched for rare DNMs reported in ID and/or DD patients. We also showed using PRS analysis that genetic risk for SCZ in each of these gene-sets could explain a significant proportion of variance in IQ. These data support a role for the genes in these sets in the aetiology of SCZ risk and associated cognitive dysfunction. Functional enrichment analysis has indicated that genes regulated by MEF2C may have a dual function in neurodevelopment. In the early stages, they are implicated in neuron generation, differentiation and development, and metabolic processes, while in later stages, these genes are involved in mitochondrial function and energy production.

The process of neurogenesis forms the fundamental basis of brain development, involving the differentiation of NSCs and neural progenitor cells (NPCs) into mature neurons [48]. NSCs have the capacity to differentiate into various functional neural lineage cells, such as neurons, astrocytes, and oligodendrocytes [49]. Aberrant neurogenesis from NSCs has been implicated as a potential underlying mechanism in the development of neuropsychiatric disorders [50,51]. This critical process appears to be susceptible to various genetic and environmental disruptions during early brain development. The cell-type enrichment analysis of our NSCs gene-sets indicated that their constituent genes are enriched within cycling progenitor cells and intermediate progenitor cells in the prenatal brain, which can produce new types of neurons and glial cells. GO analysis of the NSCs gene-sets also indicated a role for MEF2C-regulated genes in neuron development and differentiation. These findings suggest that the differentiation process from NSCs to these specific neuronal subtypes may be influenced by MEF2C disruption, and variants within the genes that encode this process may contribute to SCZ risk and cognitive dysfunction. Dysregulation in the normal development and functioning of these neural lineage cells and imbalance between them have been strongly linked to the underlying causes of SCZ and other neuropsychiatric disorders [52,53]. Enrichment analysis of KEGG pathways identified an enrichment of MEF2C direct target genes in NSCs within Orexin receptor pathway. The regulatory role of orexin (OXA) extends to various functions including sleep-wake rhythms, attention, cognition, and energy balance, all of which exhibit significant alterations in individuals with SCZ. Research has found inconsistent links between the OXA system and SCZ. Schizophrenia patients show decreased OXA plasma levels and hypothalamic OXA, with lower cortical OX2R mRNA in females. Conversely, males exhibit higher cortical OX1R and OX2R mRNA levels [54]. Furthermore, elevated OXA plasma levels have been associated with negative and disorganized symptoms in some studies [55]. We also observed that both glutamatergic excitatory neurons and GABAergic inhibitory interneurons in the prenatal and adult brain were enriched for genes from this NSCs set and from the two iNs sets. This provides further support for the balance of excitatory and inhibitory synapses, which is affected by MEF2C disruption [11], representing a potential molecular mechanism for neurodevelopmental disorders.

Synaptic activity is known to be an energy-intensive process that relies heavily on adenosine triphosphate (ATP) produced through oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) in mitochondria [56]. OXPHOS involves the activity of electron transport chain (ETC) complexes (Complex I, II, III, and IV) and ATP synthase (Complex V), where electrons produced by the citric acid cycle are transferred across mitochondrial respiratory complexes [57]. Mitochondrial ATP production is crucial for various neuronal functions, including the assembly of the actin cytoskeleton for growth cone formation, development of pre-synaptic compartments, generation of membrane potential, and synaptic vesicle recycling and endocytosis. These processes contribute to essential synaptic activities and neuronal communication [58–60]. GO analysis of the iNs gene-sets identified that MEF2C directly regulates genes involved in ATP production, including those associated with OXPHOS.

Mitochondrial dysfunction has been implicated in the complex genetic mechanisms underlying SCZ. A total of 295 mitochondria-related genes associated with SCZ were identified through the examination of various studies encompassing copy number variants (CNVs), rare and de novo mutations, genome-wide associated SNPs, transcriptomic and proteomic studies of brain tissue from SCZ patients (reviewed in [61]). Significant associations were identified between SCZ and 19 nuclear mitochondria-related genes using GWAS data [62]. Four of these genes (SMDT1, HSPE1, COQ10B, and FOXO3) are in our iNs gene-sets. FOXO3, which is also significantly associated with IQ [8] is a transcription factor. It can translocate to the mitochondria where it may bind to mtDNA and react with mitochondrial transcription factor A (TFAM) and mitochondrial RNA polymerase (mtRNApol), inducing the production of various mitochondrial genes necessary for OXPHOS [63]. Large-scale brain eQTL studies have shown significant enrichment of mitochondria-related genes. Approximately 28% of the eQTL genes implicated in SCZ were related to mitochondria [64]. Furthermore, studies investigating gene expression in postmortem brain tissues of individuals with SCZ have consistently revealed a reduction in the expression of mitochondria-related genes. Specifically, genes such as NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit V1 (NDUFV1), NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit V2 (NDUFV2), NADH: ubiquinone oxidoreductase core subunit S1 (NDUFS1) [65–67], and cytochrome c oxidase (COX) show decreased expression levels in a region-specific manner [68]. NDUFV2 and multiple isoforms of COX are present in the iNs gene-sets.

One of the most well established CNVs associated with SCZ is the deletion of chromosome 22q11.2, also known as 22q11.2 deletion syndrome (22q11.2DS) [69]. Individuals with 22q11DS often encounter cognitive impairments and a variety of neuropsychiatric disorders, including attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), SCZ, anxiety, and ASD [69]. Among the genes deleted in 22q11DS, six (MRPL40, PRODH, SLC25A1, TXNRD2, T10, and ZDHHC8) encode for mitochondrial proteins, and 3 others (COMT, UFD1L, and DGCR8) have an indirect effect on mitochondrial function [70]. A recent study demonstrated mitochondrial deficits in iPSC-derived neurons from individuals with 22q11DS and SCZ. These deficits included reduced ATP levels, impaired activity of ETC complexes I and IV, and decreased levels of mitochondrial-translated proteins [71]. Our study revealed the direct regulatory influence of MEF2C on two mitochondrial-related genes (TXNRD2 and COMT) located within the 22q11.2 region in iNs. TXNRD2 encodes for the mitochondrial Thioredoxin Reductase 2, an enzyme that is essential for reactive oxygen species clearance in brain. In 22q model transgenic mice, mitochondrial TXNRD2 has been shown to impact synaptic function and is associated with long-range cortical connectivity and psychosis-related cognitive deficits [72]. A recent investigation demonstrated that an amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS)-associated SNP located in the intronic region of MEF2C (rs304152), residing in a putative enhancer element, causes neuronal mitochondrial dysfunction. This dysfunction is characterized by decreased mitochondrial gene expression, impaired ATP production, increased oxidative stress, and decreased mitochondrial membrane potential [73]. Additionally, mitochondrial dysfunction can contribute to an imbalance in the excitatory (glutamate) and inhibitory (GABA) neurotransmitter systems [74–76], which we have referenced already as a potential molecular mechanism of neurodevelopmental disorder.

The most recent GWAS of SCZ prioritized 120 genes from the 287 genome-wide significant loci [7]. We identified a trans eQTL effect of a SNP in MEF2C on the expression of one of these prioritized genes, BNIP3L. Disruption of MEF2C in the iNs cell line resulted in reduced expression of BNIP3L. BNIP3L is involved in the selective removal of damaged mitochondria through a process called mitophagy. BNIP3L downregulation induces synaptic dysfunction arising from the accumulation of damaged mitochondria that leads to reduced mitochondrial respiration function and synaptic density [77]. It has been reported that mitophagy is significantly impaired in neurodegenerative disorders including Alzheimer’s disease, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and Huntington’s [78–81]. A recent investigation has identified both common and rare mutations in the BNIP3L gene in individuals diagnosed with SCZ [82]. The effect of identified genome-wide significant SNPs at MEF2C on its function remains to be elucidated but here is evidence that these variants may have downstream effects on direct targets of MEF2C, in this case potentially dysregulating BNIP3L and potentially contributing to mitochondrial dysfunction.

A first limitation of this study is that the ChIP-seq data was not generated from the same human neural cell models as the RNA-seq data, it came from human fetal brain cultures. Ideally, these data would come from the same source when trying to combine them to identify direct target genes. In addition, it would have strengthened the study to have validated the ChIP-seq and RNA-seq results at some target genes with quantitative PCR. It is noteworthy that the three gene-sets that were enriched for common and rare variants associated with neurodevelopmental disorders and phenotypes were also the largest gene-sets (all >1,000 genes) whereas the other 5 gene-sets each contained <500 genes. Therefore, we likely had greater statistical power to detect enrichments in these larger gene-sets. The smaller gene-sets were all enriched for variants associated with SCZ, IQ or EA at least nominally significant levels and thus may also index relevant functions to these phenotypes.

In conclusion, our study leverages data from human neural cell models of MEF2C to investigate putative molecular mechanisms of SCZ and cognitive dysfunction. These include neuron development, metabolic processes and mitochondrial dysfunction including impaired ATP production, synaptic dysfunction, imbalance in neurotransmitter systems, and disrupted mitophagy. These mechanisms provide valuable insights into how MEF2C dysregulation could contribute to the development of these complex disorders. Further investigations into the precise molecular mechanisms by which MEF2C and mitochondrial genes contribute to the development of these disorders are needed. Such insights may pave the way for the development of novel therapeutic strategies targeting mitochondrial pathways in the treatment of neuropsychiatric disorders.

Supporting information

Venn diagrams illustrate the number of shared and unique MEF2C direct target genes in each cell type separately, across different genotypes and for different types of MEF2C gene mutation. NSCs: Neural stem cells; iNs: Induced neurons; DELhom: Homozygous deletion; DELhet: Heterozygous deletion; PB: Proximal boundary (indirect mutation of MEF2C).

(TIF)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

(XLSX)

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank Profs. Bulent Ataman, Gabriella Boulting and Michael Greenberg (Harvard Medical School) for sharing MEF2C ChIP-seq data.

Data Availability

The primary data underlying the results presented in this study are available from a study that have already been published (Mohajeri et al, 2022) at DOI: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2022.09.015, which has been referenced in the manuscript. The data link is: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc=GSE204778.

Funding Statement

This work was funded by grants from the University of Galway, Ireland (https://www.universityofgalway.ie/hardiman-scholarships/; Hardiman Research Scholarship #128936 to DA), the European Research Council (https://erc.europa.eu/; ERC-2015-STG-677467 to GD) and Science Foundation Ireland (https://www.sfi.ie/; SFI 16/ERCS/3787 to GD). The funders did not play any role in the study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Leifer D, Golden J, Kowall NW: Myocyte-specific enhancer binding factor 2C expression in human brain development. Neuroscience 1994, 63:1067–1079. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(94)90573-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lyons GE, Micales BK, Schwarz J, Martin JF, Olson EN: Expression of mef2 genes in the mouse central nervous system suggests a role in neuronal maturation. J Neurosci 1995, 15:5727–5738. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.15-08-05727.1995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Li H, Radford JC, Ragusa MJ, Shea KL, McKercher SR, Zaremba JD, Soussou W, Nie Z, Kang Y-J, Nakanishi N, et al.: Transcription factor MEF2C influences neural stem/progenitor cell differentiation and maturation in vivo. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105:9397–9402. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802876105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.UniProt Consortium: UniProt: a hub for protein information. Nucleic Acids Res 2015, 43:D204–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Potthoff MJ, Olson EN: MEF2: a central regulator of diverse developmental programs. Development 2007, 134:4131–4140. doi: 10.1242/dev.008367 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Engels H, Wohlleber E, Zink A, Hoyer J, Ludwig KU, Brockschmidt FF, Wieczorek D, Moog U, Hellmann-Mersch B, Weber RG, et al.: A novel microdeletion syndrome involving 5q14.3-q15: clinical and molecular cytogenetic characterization of three patients. Eur J Hum Genet 2009, 17:1592–1599. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2009.90 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Trubetskoy V, Pardiñas AF, Qi T, Panagiotaropoulou G, Awasthi S, Bigdeli TB, Bryois J, Chen C-Y, Dennison CA, Hall LS, et al.: Mapping genomic loci implicates genes and synaptic biology in schizophrenia. Nature 2022, 604:502–508. doi: 10.1038/s41586-022-04434-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Savage JE, Jansen PR, Stringer S, Watanabe K, Bryois J, de Leeuw CA, Nagel M, Awasthi S, Barr PB, Coleman JRI, et al.: Genome-wide association meta-analysis in 269,867 individuals identifies new genetic and functional links to intelligence. Nat Genet 2018, 50:912–919. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0152-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lee JJ, Wedow R, Okbay A, Kong E, Maghzian O, Zacher M, Nguyen-Viet TA, Bowers P, Sidorenko J, Karlsson Linnér R, et al.: Gene discovery and polygenic prediction from a genome-wide association study of educational attainment in 1.1 million individuals. Nat Genet 2018, 50:1112–1121. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0147-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mitchell AC, Javidfar B, Pothula V, Ibi D, Shen EY, Peter CJ, Bicks LK, Fehr T, Jiang Y, Brennand KJ, et al.: MEF2C transcription factor is associated with the genetic and epigenetic risk architecture of schizophrenia and improves cognition in mice. Mol Psychiatry 2018, 23:123–132. doi: 10.1038/mp.2016.254 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harrington AJ, Raissi A, Rajkovich K, Berto S, Kumar J, Molinaro G, Raduazzo J, Guo Y, Loerwald K, Konopka G, et al.: MEF2C regulates cortical inhibitory and excitatory synapses and behaviors relevant to neurodevelopmental disorders. eLife 2016, 5:e20059. doi: 10.7554/eLife.20059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harrington AJ, Bridges CM, Berto S, Blankenship K, Cho JY, Assali A, Siemsen BM, Moore HW, Tsvetkov E, Thielking A, et al.: MEF2C Hypofunction in Neuronal and Neuroimmune Populations Produces MEF2C Haploinsufficiency Syndrome-like Behaviors in Mice. Biol Psychiatry 2020, 88:488–499. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2020.03.011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Adachi M, Lin P-Y, Pranav H, Monteggia LM: Postnatal Loss of Mef2c Results in Dissociation of Effects on Synapse Number and Learning and Memory. Biol Psychiatry 2016, 80:140–148. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2015.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tu S, Akhtar MW, Escorihuela RM, Amador-Arjona A, Swarup V, Parker J, Zaremba JD, Holland T, Bansal N, Holohan DR, et al.: NitroSynapsin therapy for a mouse MEF2C haploinsufficiency model of human autism. Nat Commun 2017, 8:1488. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01563-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Barbosa AC, Kim M-S, Ertunc M, Adachi M, Nelson ED, McAnally J, Richardson JA, Kavalali ET, Monteggia LM, Bassel-Duby R, et al.: MEF2C, a transcription factor that facilitates learning and memory by negative regulation of synapse numbers and function. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2008, 105:9391–9396. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0802679105 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mohajeri K, Yadav R, D’haene E, Boone PM, Erdin S, Gao D, Moyses-Oliveira M, Bhavsar R, Currall BB, O’Keefe K, et al.: Transcriptional and functional consequences of alterations to MEF2C and its topological organization in neuronal models. Am J Hum Genet 2022, 109:2049–2067. doi: 10.1016/j.ajhg.2022.09.015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gasiorowska A, Wydrych M, Drapich P, Zadrozny M, Steczkowska M, Niewiadomski W, Niewiadomska G: The Biology and Pathobiology of Glutamatergic, Cholinergic, and Dopaminergic Signaling in the Aging Brain. Front Aging Neurosci 2021, 13:654931. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2021.654931 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ataman B, Boulting GL, Harmin DA, Yang MG, Baker-Salisbury M, Yap E-L, Malik AN, Mei K, Rubin AA, Spiegel I, et al.: Evolution of Osteocrin as an activity-regulated factor in the primate brain. Nature 2016, 539:242–247. doi: 10.1038/nature20111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Li H, Durbin R: Fast and accurate short read alignment with Burrows–Wheeler transform. Bioinformatics 2009, 25:1754–1760. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btp324 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li H, Handsaker B, Wysoker A, Fennell T, Ruan J, Homer N, Marth G, Abecasis G, Durbin R, 1000 Genome Project Data Processing Subgroup: The Sequence Alignment/Map format and SAMtools. Bioinformatics 2009, 25:2078–2079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Myers RM, Brown M, Li W, et al.: Model-based Analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biology 2008, 9:R137. doi: 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yu G, Wang L-G, He Q-Y: ChIPseeker: an R/Bioconductor package for ChIP peak annotation, comparison and visualization. Bioinformatics 2015, 31:2382–2383. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btv145 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang S, Sun H, Ma J, Zang C, Wang C, Wang J, Tang Q, Meyer CA, Zhang Y, Liu XS: Target analysis by integration of transcriptome and ChIP-seq data with BETA. Nat Protoc 2013, 8:2502–2515. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2013.150 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bulik-Sullivan BK, Loh P-R, Finucane HK, Ripke S, Yang J, Schizophrenia Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium, Patterson N, Daly MJ, Price AL, Neale BM: LD Score regression distinguishes confounding from polygenicity in genome-wide association studies. Nat Genet 2015, 47:291–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Demontis D, Walters RK, Martin J, Mattheisen M, Als TD, Agerbo E, Baldursson G, Belliveau R, Bybjerg-Grauholm J, Bækvad-Hansen M, et al.: Discovery of the first genome-wide significant risk loci for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Nat Genet 2019, 51:63–75. doi: 10.1038/s41588-018-0269-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.International Obsessive Compulsive Disorder Foundation Genetics Collaborative (IOCDF-GC) and OCD Collaborative Genetics Association Studies (OCGAS): Revealing the complex genetic architecture of obsessive-compulsive disorder using meta-analysis. Mol Psychiatry 2018, 23:1181–1188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Lambert JC, Ibrahim-Verbaas CA, Harold D, Naj AC, Sims R, Bellenguez C, DeStafano AL, Bis JC, Beecham GW, Grenier-Boley B, et al.: Meta-analysis of 74,046 individuals identifies 11 new susceptibility loci for Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Genet 2013, 45:1452–1458. doi: 10.1038/ng.2802 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Traylor M, Farrall M, Holliday EG, Sudlow C, Hopewell JC, Cheng Y-C, Fornage M, Ikram MA, Malik R, Bevan S, et al.: Genetic risk factors for ischaemic stroke and its subtypes (the METASTROKE collaboration): a meta-analysis of genome-wide association studies. Lancet Neurol 2012, 11:951–962. doi: 10.1016/S1474-4422(12)70234-X [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Corley E, Patlola SR, Laighneach A, Corvin A, McManus R, Kenyon M, Kelly JP, Mckernan DP, King S, Hallahan B, et al.: Genetic and inflammatory effects on childhood trauma and cognitive functioning in patients with schizophrenia and healthy participants. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2024, 115:26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.bbi.2023.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Whitton L, Cosgrove D, Clarkson C, Harold D, Kendall K, Richards A, Mantripragada K, Owen MJ, O’Donovan MC, Walters J, et al.: Cognitive analysis of schizophrenia risk genes that function as epigenetic regulators of gene expression. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part B: Neuropsychiatric Genetics 2016, 171:1170–1179. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.32503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ware JS, Samocha KE, Homsy J, Daly MJ: Interpreting de novo Variation in Human Disease Using denovolyzeR. Curr Protoc Hum Genet 2015, 87:7.25.1–7.25.15. doi: 10.1002/0471142905.hg0725s87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Howrigan DP, Rose SA, Samocha KE, Fromer M, Cerrato F, Chen WJ, Churchhouse C, Chambert K, Chandler SD, Daly MJ, et al.: Exome sequencing in schizophrenia-affected parent–offspring trios reveals risk conferred by protein-coding de novo mutations. Nat Neurosci 2020, 23:185–193. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0564-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang Q, Li M, Yang Z, Hu X, Wu H-M, Ni P, Ren H, Deng W, Li M, Ma X, et al.: Increased co-expression of genes harboring the damaging de novo mutations in Chinese schizophrenic patients during prenatal development. Sci Rep 2015, 5:18209. doi: 10.1038/srep18209 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ambalavanan A, Girard SL, Ahn K, Zhou S, Dionne-Laporte A, Spiegelman D, Bourassa CV, Gauthier J, Hamdan FF, Xiong L, et al.: De novo variants in sporadic cases of childhood onset schizophrenia. Eur J Hum Genet 2016, 24:944–948. doi: 10.1038/ejhg.2015.218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rees E, Han J, Morgan J, Carrera N, Escott-Price V, Pocklington AJ, Duffield M, Hall LS, Legge SE, Pardiñas AF, et al.: De novo mutations identified by exome sequencing implicate rare missense variants in SLC6A1 in schizophrenia. Nat Neurosci 2020, 23:179–184. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0565-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Satterstrom FK, Kosmicki JA, Wang J, Breen MS, De Rubeis S, An J-Y, Peng M, Collins R, Grove J, Klei L, et al.: Large-Scale Exome Sequencing Study Implicates Both Developmental and Functional Changes in the Neurobiology of Autism. Cell 2020, 180:568–584.e23. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2019.12.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Genovese G, Fromer M, Stahl EA, Ruderfer DM, Chambert K, Landén M, Moran JL, Purcell SM, Sklar P, Sullivan PF, et al.: Increased burden of ultra-rare protein-altering variants among 4,877 individuals with schizophrenia. Nat Neurosci 2016, 19:1433–1441. doi: 10.1038/nn.4402 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bowling KM, Thompson ML, Amaral MD, Finnila CR, Hiatt SM, Engel KL, Cochran JN, Brothers KB, East KM, Gray DE, et al.: Genomic diagnosis for children with intellectual disability and/or developmental delay. Genome Med 2017, 9:43. doi: 10.1186/s13073-017-0433-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chevarin M, Duffourd Y, Barnard RA, Moutton S, Lecoquierre F, Daoud F, Kuentz P, Cabret C, Thevenon J, Gautier E, et al.: Excess of de novo variants in genes involved in chromatin remodelling in patients with marfanoid habitus and intellectual disability. Journal of Medical Genetics 2020, 57:466–474. doi: 10.1136/jmedgenet-2019-106425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Deciphering Developmental Disorders Study: Prevalence and architecture of de novo mutations in developmental disorders. Nature 2017, 542:433–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Skene NG, Grant SGN: Identification of Vulnerable Cell Types in Major Brain Disorders Using Single Cell Transcriptomes and Expression Weighted Cell Type Enrichment. Front Neurosci 2016, 10:16. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2016.00016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Cameron D, Mi D, Vinh N-N, Webber C, Li M, Marín O, O’Donovan MC, Bray NJ: Single-Nuclei RNA Sequencing of 5 Regions of the Human Prenatal Brain Implicates Developing Neuron Populations in Genetic Risk for Schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry 2023, 93:157. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2022.06.033 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hodge RD, Bakken TE, Miller JA, Smith KA, Barkan ER, Graybuck LT, Close JL, Long B, Johansen N, Penn O, et al.: Conserved cell types with divergent features in human versus mouse cortex. Nature 2019, 573:61–68. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1506-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Tasic B, Yao Z, Graybuck LT, Smith KA, Nguyen TN, Bertagnolli D, Goldy J, Garren E, Economo MN, Viswanathan S, et al.: Shared and distinct transcriptomic cell types across neocortical areas. Nature 2018, 563:72–78. doi: 10.1038/s41586-018-0654-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bindea G, Galon J, Mlecnik B: CluePedia Cytoscape plugin: pathway insights using integrated experimental and in silico data. Bioinformatics 2013, 29:661–663. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Sjöstedt E, Zhong W, Fagerberg L, Karlsson M, Mitsios N, Adori C, Oksvold P, Edfors F, Limiszewska A, Hikmet F, et al.: An atlas of the protein-coding genes in the human, pig, and mouse brain. Science 2020, 367:eaay5947. doi: 10.1126/science.aay5947 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lonsdale J, Thomas J, Salvatore M, Phillips R, Lo E, Shad S, Hasz R, Walters G, Garcia F, Young N, et al.: The Genotype-Tissue Expression (GTEx) project. Nat Genet 2013, 45:580–585. doi: 10.1038/ng.2653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ribeiro FF, Xapelli S: An Overview of Adult Neurogenesis. In Recent Advances in NGF and Related Molecules: The Continuum of the NGF “Saga.” Edited by Calzà L, Aloe L, Giardino L. Springer International Publishing; 2021:77–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Thier M, Wörsdörfer P, Lakes YB, Gorris R, Herms S, Opitz T, Seiferling D, Quandel T, Hoffmann P, Nöthen MM, et al.: Direct Conversion of Fibroblasts into Stably Expandable Neural Stem Cells. Cell Stem Cell 2012, 10:473–479. doi: 10.1016/j.stem.2012.03.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hagihara H, Takao K, Walton NM, Matsumoto M, Miyakawa T: Immature Dentate Gyrus: An Endophenotype of Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Neural Plast 2013, 2013:318596. doi: 10.1155/2013/318596 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Cho K-O, Lybrand ZR, Ito N, Brulet R, Tafacory F, Zhang L, Good L, Ure K, Kernie SG, Birnbaum SG, et al.: Aberrant hippocampal neurogenesis contributes to epilepsy and associated cognitive decline. Nature Communications 2015, 6:6606. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gao R, Penzes P: Common Mechanisms of Excitatory and Inhibitory Imbalance in Schizophrenia and Autism Spectrum Disorders. Curr Mol Med 2015, 15:146–167. doi: 10.2174/1566524015666150303003028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Foss-Feig JH, Adkinson BD, Ji JL, Yang G, Srihari VH, McPartland JC, Krystal JH, Murray JD, Anticevic A: Searching for Cross-Diagnostic Convergence: Neural Mechanisms Governing Excitation and Inhibition Balance in Schizophrenia and Autism Spectrum Disorders. Biological Psychiatry 2017, 81:848–861. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.03.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lu J, Huang M-L, Li J-H, Jin K-Y, Li H-M, Mou T-T, Fronczek R, Duan J-F, Xu W-J, Swaab D, et al.: Changes of Hypocretin (Orexin) System in Schizophrenia: From Plasma to Brain. Schizophr Bull 2021, 47:1310–1319. doi: 10.1093/schbul/sbab042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chien Y-L, Liu C-M, Shan J-C, Lee H-J, Hsieh MH, Hwu H-G, Chiou L-C: Elevated plasma orexin A levels in a subgroup of patients with schizophrenia associated with fewer negative and disorganized symptoms. Psychoneuroendocrinology 2015, 53:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.psyneuen.2014.12.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Hall CN, Klein-Flügge MC, Howarth C, Attwell D: Oxidative Phosphorylation, Not Glycolysis, Powers Presynaptic and Postsynaptic Mechanisms Underlying Brain Information Processing. J Neurosci 2012, 32:8940–8951. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0026-12.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wen Y: Maxwell’s demon at work: Mitochondria, the organelles that convert information into energy? Chronic Dis Transl Med 2018, 4:135–138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Verstreken P, Ly CV, Venken KJT, Koh T-W, Zhou Y, Bellen HJ: Synaptic Mitochondria Are Critical for Mobilization of Reserve Pool Vesicles at Drosophila Neuromuscular Junctions. Neuron 2005, 47:365–378. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.06.018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Attwell D, Laughlin SB: An Energy Budget for Signaling in the Grey Matter of the Brain. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism 2001, 21:1133. doi: 10.1097/00004647-200110000-00001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Lee CW, Peng HB: The function of mitochondria in presynaptic development at the neuromuscular junction. Mol Biol Cell 2008, 19:150–158. doi: 10.1091/mbc.e07-05-0515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Hjelm BE, Rollins B, Mamdani F, Lauterborn JC, Kirov G, Lynch G, Gall CM, Sequeira A, Vawter MP: Evidence of Mitochondrial Dysfunction within the Complex Genetic Etiology of Schizophrenia. Mol Neuropsychiatry 2015, 1:201–219. doi: 10.1159/000441252 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Gonçalves VF, Cappi C, Hagen CM, Sequeira A, Vawter MP, Derkach A, Zai CC, Hedley PL, Bybjerg-Grauholm J, Pouget JG, et al.: A comprehensive analysis of nuclear-encoded mitochondrial genes in schizophrenia. Biol Psychiatry 2018, 83:780–789. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.02.1175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Celestini V, Tezil T, Russo L, Fasano C, Sanese P, Forte G, Peserico A, Lepore Signorile M, Longo G, De Rasmo D, et al.: Uncoupling FoxO3A mitochondrial and nuclear functions in cancer cells undergoing metabolic stress and chemotherapy. Cell Death Dis 2018, 9:231. doi: 10.1038/s41419-018-0336-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Kim Y, Xia K, Tao R, Giusti-Rodriguez P, Vladimirov V, van den Oord E, Sullivan PF: A meta-analysis of gene expression quantitative trait loci in brain. Transl Psychiatry 2014, 4:e459. doi: 10.1038/tp.2014.96 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Ben-Shachar D, Karry R: Neuroanatomical Pattern of Mitochondrial Complex I Pathology Varies between Schizophrenia, Bipolar Disorder and Major Depression. PLOS ONE 2008, 3:e3676. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0003676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ben-Shachar D, Karry R: Sp1 Expression Is Disrupted in Schizophrenia; A Possible Mechanism for the Abnormal Expression of Mitochondrial Complex I Genes, NDUFV1 and NDUFV2. PLOS ONE 2007, 2:e817. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0000817 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Ben-Shachar D: Mitochondrial complex I as a possible novel peripheral biomarker for schizophrenia. In The handbook of neuropsychiatric biomarkers, endophenotypes and genes, Vol 3: Metabolic and peripheral biomarkers. Springer Science + Business Media; 2009:71–83. [Google Scholar]

- 68.Rice MW, Smith KL, Roberts RC, Perez-Costas E, Melendez-Ferro M: Assessment of Cytochrome C Oxidase Dysfunction in the Substantia Nigra/Ventral Tegmental Area in Schizophrenia. PLOS ONE 2014, 9:e100054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0100054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McDonald-McGinn DM, Sullivan KE, Marino B, Philip N, Swillen A, Vorstman JAS, Zackai EH, Emanuel BS, Vermeesch JR, Morrow BE, et al.: 22q11.2 deletion syndrome. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2015, 1:15071. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2015.71 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Napoli E, Tassone F, Wong S, Angkustsiri K, Simon TJ, Song G, Giulivi C: Mitochondrial Citrate Transporter-dependent Metabolic Signature in the 22q11.2 Deletion Syndrome. J Biol Chem 2015, 290:23240–23253. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M115.672360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Li J, Ryan SK, Deboer E, Cook K, Fitzgerald S, Lachman HM, Wallace DC, Goldberg EM, Anderson SA: Mitochondrial deficits in human iPSC-derived neurons from patients with 22q11.2 deletion syndrome and schizophrenia. Transl Psychiatry 2019, 9:302. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Fernandez A, Meechan DW, Karpinski BA, Paronett EM, Bryan CA, Rutz HL, Radin EA, Lubin N, Bonner ER, Popratiloff A, et al.: Mitochondrial Dysfunction Leads to Cortical Under-connectivity and Cognitive Impairment. Neuron 2019, 102:1127–1142.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2019.04.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yousefian-Jazi A, Kim S, Choi S-H, Chu J, Nguyen PT-T, Park U, Lim K, Hwang H, Lee K, Kim Y, et al.: Loss of MEF2C function by enhancer mutation leads to neuronal mitochondria dysfunction and motor deficits in mice. 2024, doi: 10.1101/2024.07.15.603186 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Anderson M, Hooker BS, Herbert M: Bridging from Cells to Cognition in Autism Pathophysiology: Biological Pathways to Defective Brain Function and Plasticity. American Journal of Biochemistry and Biotechnology, 4(2):167–176 2008, 4. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Rubenstein JLR, Merzenich MM: Model of autism: increased ratio of excitation/inhibition in key neural systems. Genes Brain Behav 2003, 2:255–267. doi: 10.1034/j.1601-183x.2003.00037.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Liu Y, Ouyang P, Zheng Y, Mi L, Zhao J, Ning Y, Guo W: A Selective Review of the Excitatory-Inhibitory Imbalance in Schizophrenia: Underlying Biology, Genetics, Microcircuits, and Symptoms. Front Cell Dev Biol 2021, 9:664535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Choi GE, Lee HJ, Chae CW, Cho JH, Jung YH, Kim JS, Kim SY, Lim JR, Han HJ: BNIP3L/NIX-mediated mitophagy protects against glucocorticoid-induced synapse defects. Nat Commun 2021, 12:487. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-20679-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fang EF, Hou Y, Palikaras K, Adriaanse BA, Kerr JS, Yang B, Lautrup S, Hasan-Olive MM, Caponio D, Dan X, et al.: Mitophagy inhibits amyloid-β and tau pathology and reverses cognitive deficits in models of Alzheimer’s disease. Nat Neurosci 2019, 22:401–412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Chu CT: Multiple Pathways for Mitophagy: A Neurodegenerative Conundrum for Parkinson’s Disease. Neurosci Lett 2019, 697:66–71. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2018.04.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Palomo GM, Granatiero V, Kawamata H, Konrad C, Kim M, Arreguin AJ, Zhao D, Milner TA, Manfredi G: Parkin is a disease modifier in the mutant SOD1 mouse model of ALS. EMBO Mol Med 2018, 10:e8888. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201808888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Hwang S, Disatnik M-H, Mochly-Rosen D: Impaired GAPDH-induced mitophagy contributes to the pathology of Huntington’s disease. EMBO Mol Med 2015, 7:1307–1326. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201505256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhou J, Ma C, Wang K, Li X, Jian X, Zhang H, Yuan J, Yin J, Chen J, Shi Y: Identification of rare and common variants in BNIP3L: a schizophrenia susceptibility gene. Hum Genomics 2020, 14:16. doi: 10.1186/s40246-020-00266-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]