Abstract

Objective:

Individuals with serious mental illnesses are very likely to interact with police officers. The crisis intervention team (CIT) model is being widely implemented by police departments across the United States to improve officers’ responses. However, little research exists on officer-level outcomes. The authors compared officers with or without CIT training on six key constructs related to the CIT model: knowledge about mental illnesses, attitudes about serious mental illnesses and treatments, self-efficacy for deescalating crisis situations and making referrals to mental health services, stigmatizing attitudes, deescalation skills, and referral decisions.

Methods:

The sample included 586 officers, 251 of whom had received the 40-hour CIT training (median of 22 months before the study), from six police departments in Georgia. In-depth, in-person assessments of officers’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills were administered. Many measures were linked to two vignettes, in written and video formats, depicting typical police encounters with individuals with psychosis or with suicidality.

Results:

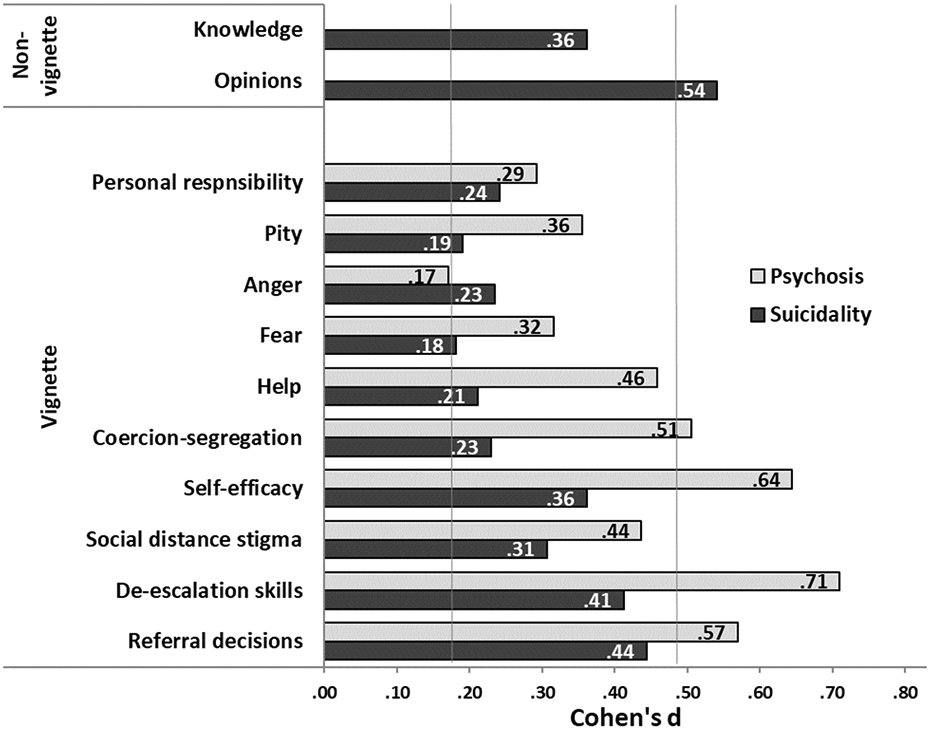

CIT-trained officers had consistently better scores on knowledge, diverse attitudes about mental illnesses and their treatments, self-efficacy for interacting with someone with psychosis or suicidality, social distance stigma, deescalation skills, and referral decisions. Effect sizes for some measures, including deescalation skills and referral decisions pertaining to psychosis, were substantial (d=.71 and .57, respectively, p <.001).

Conclusions:

CIT training of police officers resulted in sizable and persisting improvements in diverse aspects of knowledge, attitudes, and skills. Research should now address potential outcomes at the system level and for individuals with whom officers interact.

Keywords: Criminal justice, Crisis Intervention Team, Jail diversion, Law enforcement, Police

Police officers are often first responders to emergency calls involving individuals with serious mental illnesses (1), defined as mental disorders that substantially interfere with one’s life activities and ability to function, such as schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depression. In fact, up to 10% of all police contacts involve a person with a mental illness (2), and officers provide up to ⅓ of all emergency mental health referrals (3). Thus, as officers are not just gatekeepers to the justice system but also to the psychiatric system (4), they serve as de facto mental health professionals (5), making decisions regarding referral to mental health services versus arrest/incarceration versus other discretionary decisions. Despite the magnitude of this pervasive societal issue that involves the most vulnerable individuals with serious mental illnesses and some of the most strained public sectors, officers usually receive little training on mental illnesses, though they want more training and find the topic very important to their work (6).

To improve officers’ responses to individuals with serious mental illnesses, the Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) model was developed in 1988 in Memphis (7-9). CIT provides select officers 40 hours of specialized training by police trainers, local mental health professionals, family advocates, and consumer groups (7,10), equipping them with the necessary knowledge, attitudes, and skills to enhance their responses to persons with serious mental illnesses or those in psychiatric crisis (1,2,8). After training, officers are specialized first-line responders to such calls (11-14). CIT also supports partnerships between psychiatric emergency services and police departments, encouraging treatment rather than jail when appropriate (1,10). Thus, in addition to its other goals (e.g., improved officer and subject safety), CIT is a form of pre-booking jail diversion.

Given the very wide implementation and rapid growth of CIT in recent years (to date, there are likely >2,700 police departments in the U.S. having implemented CIT; personal communication, Dr. Randolph Dupont, July 2013), research on this police-based collaboration between law enforcement, advocacy, and mental health is urgently needed (15). This study focused on how CIT training affects a number of key officer-level outcomes that likely underlie its broader beneficial effects. The purpose of this study was to document differences between CIT-trained and non-CIT officers across six key constructs. We first assessed potentially important covariates by determining differences between the CIT-trained and non-CIT groups in demographics, experience, and empathy. We then determined differences between CIT-trained and non-CIT officers, while considering effects of covariates, for our six constructs of interest: knowledge about mental illnesses, attitudes about serious mental illnesses and their treatments, self-efficacy for de-escalating crisis situations and making referrals to mental health services, stigma toward persons with serious mental illnesses, de-escalation skills, and referral decisions.

Method

Participants

Police officers (n=586), including both CIT-trained (n=251) and traditional, non-CIT officers (n=335), were recruited from six police departments in Georgia. Each department, described in Table 1 in the companion article that follows (reference), had implemented CIT training of officers using a standardized 40-hour curriculum developed and made available through a statewide CIT initiative (14), though relying on local instructors. The percentage of participating CIT officers who reported having volunteered for their CIT training (as opposed to being assigned to it)—given that self-selection or volunteering for CIT specialization is commonly considered a core element of the CIT model—ranged from 36% to 100% across the six departments (65.5% across all 251 CIT officers).

Table 1.

CIT versus Non-CIT Group Differences in Scales Measuring the Six Key Constructs

| CIT Officers | Non-CIT Officers | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Variable | Range | N | M | SD | N | M | SD | t | p | d |

| Knowledge about mental illnesses | ||||||||||

| Knowledge (% correct) | 0–100 | 251 | 59 | 15 | 335 | 54 | 15 | 4.32 | <.001 | .36 |

| Attitudes about mental illnesses and their treatments | ||||||||||

| Opinions about mental illnesses | 1–6 | 249 | 4.24 | .45 | 331 | 4.01 | .40 | 6.44 | <.001 | .54 |

| AQ Personal responsibility-P | 1–9 | 249 | 2.54 | 1.30 | 332 | 2.96 | 1.49 | −3.48 | .001 | −.29 |

| AQ Personal responsibility-S | 1–9 | 251 | 4.89 | 1.81 | 333 | 5.31 | 1.74 | −2.88 | .004 | −.24 |

| AQ Pity-P | 1–9 | 249 | 6.35 | 1.72 | 331 | 5.71 | 1.82 | 4.23 | <.001 | .36 |

| AQ Pity-S | 1–9 | 250 | 5.91 | 1.74 | 333 | 5.57 | 1.78 | 2.28 | .023 | .19 |

| AQ Anger-P | 1–9 | 249 | 3.29 | 1.73 | 331 | 3.58 | 1.74 | −2.02 | .043 | −.17 |

| AQ Anger-S | 1–9 | 251 | 3.13 | 1.66 | 333 | 3.54 | 1.79 | −2.80 | .005 | −.23 |

| AQ Fear-P | 1–9 | 249 | 4.71 | 1.73 | 331 | 5.27 | 1.80 | −3.76 | <.001 | −.32 |

| AQ Fear-S | 1–9 | 251 | 4.25 | 1.63 | 333 | 4.55 | 1.63 | −2.16 | .031 | −.18 |

| AQ Help-P | 1–9 | 250 | 3.48 | 1.39 | 331 | 2.89 | 1.20 | 5.46 | <.001 | .46 |

| AQ Help-S | 1–9 | 251 | 4.99 | 1.80 | 333 | 4.62 | 1.69 | 2.52 | .012 | .21 |

| AQ Coercion-segregation-P | 1–9 | 249 | 4.77 | 1.76 | 332 | 5.62 | 1.64 | −6.02 | <.001 | −.51 |

| AQ Coercion-segregation-S | 1–9 | 251 | 3.06 | 1.56 | 333 | 3.42 | 1.58 | −2.73 | .006 | −.23 |

| RCDS External control-P | 1–9 | 250 | 4.59 | 1.69 | 332 | 4.48 | 1.55 | .76 | .45 | .06 |

| RCDS External control-S | 1–9 | 251 | 4.73 | 1.64 | 333 | 4.60 | 1.63 | .90 | .37 | .08 |

| RCDS Personal control-P | 1–9 | 250 | 3.50 | 1.61 | 332 | 3.64 | 1.71 | −1.04 | .30 | −.09 |

| RCDS Personal control-S | 1–9 | 251 | 5.99 | 1.77 | 333 | 6.14 | 1.79 | −1.00 | .32 | −.08 |

| Self-efficacy | ||||||||||

| Self-efficacy-P | 1–4 | 250 | 3.34 | .44 | 332 | 3.05 | .46 | 7.68 | <.001 | .64 |

| Self-efficacy-S | 1–4 | 251 | 3.46 | .42 | 333 | 3.31 | .40 | 4.32 | <.001 | .36 |

| Stigma | ||||||||||

| Social distance-P | 1–4 | 250 | 2.43 | .67 | 331 | 2.72 | .65 | −5.20 | <.001 | −.44 |

| Social distance-S | 1–4 | 251 | 2.09 | .68 | 333 | 2.29 | .65 | −3.66 | <.001 | −.31 |

| Stigmatizing attitudes-P | 0–9 | 250 | 4.82 | .84 | 330 | 4.92 | .93 | −1.34 | .18 | −.11 |

| Stigmatizing attitudes-S | 0–9 | 244 | 4.65 | .92 | 327 | 4.63 | .96 | .26 | .80 | .02 |

| De-escalation skills | ||||||||||

| De-escalation skills-P | 1–4 | 249 | 3.20 | .36 | 332 | 2.97 | .31 | 8.45 | <.001 | .71 |

| De-escalation skills-S | 1–4 | 251 | 3.18 | .32 | 333 | 3.05 | .31 | 4.92 | <.001 | .41 |

| Referral decisions | ||||||||||

| Referral decisions-P | 1–4 | 249 | 3.46 | .37 | 332 | 3.24 | .39 | 6.78 | <.001 | .57 |

| Referral decisions-S | 1–4 | 251 | 3.49 | .36 | 333 | 3.33 | .37 | 5.30 | <.001 | .44 |

Note. Variables suffixed with “P” derive from the psychosis vignette and with “S” from the suicidality vignette. Cohen’s d is the standardized difference between the means. AQ=Attribution Questionnaire; RCDS=Revised Causal Dimensions Scale.

After hearing about the study through roll-call presentations, email notices, flyers posted in department precincts, or word of mouth, both CIT and non-CIT officers interested in participating called the research team to register for one of 34 proctored, group-based (including 6–29 officers in each), in-depth survey administrations between April and October 2010. Officers took part during off-duty hours and were compensated to remunerate them for their travel time to and from the assessment, the approximately three hours spent completing the survey, and parking.

The average age of the 586 officers was 37.0±8.7 years and participants had been officers an average of 10.0±7.7 years. Nineteen percent were female. Seventeen percent had graduated high school as their highest level of education, 41% had completed some college, 10% had an associate’s degree, 26% had a bachelor’s degree, and 6% had a master’s degree. Thirty-five percent self-identified as African American and 61% as Caucasian. Among 251 CIT-trained officers, time since training varied from <1 month to >7 years. The median months since training was 22 and 50% were between 7 and 37 months; for subsequent analyses, participants were coded 1–5 for 1st–5th quintiles of time since training.

Procedures and Measures

The assessment required ~3 hours, with roughly ⅓ focused on demographics, experience, empathy, knowledge, and attitudinal factors, and the remainder on attitudinal and behavioral responses to two vignettes, one written and one video, which were developed (and the videos professionally produced) specifically for this study. One vignette depicted an agitated, disheveled, disorganized, and psychotic man digging through a trashcan at a business, with an officer arriving on the scene (4.2 minutes, herein called the “psychosis vignette”). The other presented an intoxicated, distraught (due to a relationship break-up), and suicidal woman who had locked herself in her home bathroom, with an officer arriving on the scene (2.5 minutes, the “suicidality vignette”). Groups of officers received one vignette in a video format and the other as a written script, in a counterbalanced manner. The study was approved by the Emory University Institutional Review Board and participants provided written informed consent.

With the exception of experience with mental health treatment and knowledge about mental illnesses, all constructs were scored as the mean of items answered if responses were given for ≥75% of items. Reverse scoring was conducted as appropriate so that higher scores for all measures represent more of the named attribute. The possible ranges for all variables are given in Table 1.

The first portion of the assessment included a number of measures not linked to vignettes. To assess experience with mental health treatment, four items asked whether the participant (referred to herein as “self”), a family member, or a friend had received or was now receiving mental health treatment, or whether the participant or family members or friends had volunteered or worked in the mental health field (“other”). We created an experience index, coded 0–5, to summarize these four items: 0 if they responded negatively to all four items (33%); 1 for an affirmative response only to “other” (11%); 2 if they responded yes only to “friend,” and maybe “other” as well (16%); 3 if they responded yes to “family” but not “friend,” and maybe “other” as well (10%); 4 if they responded yes to both “family” and “friend,” and maybe “other’ as well (16%); and 5 if they responded affirmatively to “self” (14%).

The construct empathy toward individuals with mental illnesses, serving as a potential personality-related covariate, was assessed with an adapted version of a 9-item measure (16). In response to “indicate how much you feel each emotion toward people with mental illnesses,” each item (e.g., compassion, disgust, respect) is rated 0=not at all, to 10=extremely; Cronbach’s α=.78. To measure knowledge about mental illnesses, officers completed the 33-item Knowledge of Mental Illnesses Test (17), scored as the percentage of correct items.

Several measures were administered to thoroughly assess attitudes about mental illnesses and their treatments. The Opinions about Mental Illnesses scale (18,19) consists of five subscales: authoritarianism (scored such that high scores were less), benevolence, mental hygiene, social restrictiveness, and interpersonal etiology; α=.69, .63, .42, .72, .75. Two additional scales assessed attitudes toward community mental health treatment facilities (20,21) and attitudes about psychiatric treatments more broadly, in addition to hospitals and community facilities (22); α=.83, .72. The six reliable scales (excluding mental hygiene) were inter-correlated (mean r=.57; range, .29–.67). Accordingly, an “opinions about mental illnesses” variable was computed as the mean of these six scales (items for all scales were rated 1–6); α=.84.

All remaining measures were administered twice, linked to the two vignettes. Two rating scales pertained to the attitudes construct. The Attribution Questionnaire (23,24) consists of 21 items in six domains (e.g., personal responsibility, pity, anger), and the 12-item Revised Causal Dimensions Scale (25-27) assesses causal attributions along four domains: external control, personal control, locus of causality/internality, and stability. The latter two had unacceptably low internal consistency and were not considered further. The mean α for the remaining eight attitudinal domains was .76 when linked to the psychosis vignette (range, .59–.87) and .78 with respect to the suicidality vignette (range, .62–.87).

The self-efficacy for de-escalating crisis situations and making referrals to mental health services construct was measured with a 16-item questionnaire rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1=not at all confident, to 4=very confident (22); α=.94 when linked to both vignettes. To measure stigma toward people with mental illnesses, we used two instruments, an adapted version of the Social Distance Scale and a semantic differential measure. Regarding the former, participants rated their willingness to be close (e.g., live next door) to the individual depicted in the vignette on a 4-point scale ranging from 1=very willing, to 4=very unwilling (22); α=.92 when linked to both vignettes. For the second stigma measure, respondents rated an average person, the man in the psychosis vignette, and the woman in the suicidality vignette, 1–7 on 12 semantic differentials (e.g., valuable–worthless). The 12 items were scored so that higher values reflected more positive judgments; α=.86, .83, .84. Total stigmatizing attitudes toward psychosis was computed by subtracting the psychosis-vignette mean from the average-person mean, and likewise for stigmatizing attitudes toward suicidality. To make all values positive, four was added to each score, resulting in an index varying from just above zero to just below nine.

Finally, the de-escalation skills and referral decisions constructs were measured by two instruments designed specifically for this study, and tested previously in an independent sample of nearly 200 officers (22). Both were 8-item instruments assessing officers’ opinions on the effectiveness of specific actions in the two situations depicted, rated on a 4-point scale ranging from 1=very negative, to 4=very positive.

Statistical Analysis

Due to the extent of the data deriving from these multiple measures, the large sample size, and number of analyses, we used p≤.01 as our criterion for significance and refer to effects significant at the .05 but not the .01 level as marginal. Throughout, we present effect sizes as well as statistical significance (28). We use Cohen’s d, the standardized difference between two means (29), following Cohen’s criteria: .2 is a small (weak) effect, .5 is a medium (moderate) effect, and .8 is a large (strong) effect.

Results

CIT vs. Non-CIT Differences in Demographics, Experience, and Empathy

CIT-trained and non-CIT officers did not differ in age, race, years of education, or years having served as an officer. CIT-trained officers were about twice as likely to be female as non-CIT officers, 27% versus 14%; odds ratio (OR)=2.23, p<.001. The two additional potential covariates did in fact distinguish the groups. Specifically, experience and empathy means for CIT-trained were higher than for non-CIT officers; 2.4 vs. 1.8 on a 0–5 scale and 6.8 vs. 6.3 on a 0–10 scale, t=4.23 and 3.88 (d=.35 and .33), respectively (p<.001 for both).

CIT vs. Non-CIT Differences in the Six Key Constructs

Differences in the two groups were examined with analyses of covariance that included age, gender, years having worked as an officer, years of education, the experience index, and empathy as covariates. Covariates had little effect on group differences; essentially the same levels of significance were obtained with independent samples t-tests. The CIT-trained group differed consistently from the non-CIT group (see Table 1); e.g., they scored higher on knowledge and opinions about mental illnesses and lower on anger and fear attitudes.

Regarding the 17 items of the attitudes construct (the first of which is a mean of six scales; Table 1), except for external and personal control, differences were at least marginal for the remaining 13 and significant (p<.01) for nine; of these, the effect size was weak for seven and moderate for two (opinions about mental illnesses and coercion-segregation pertaining to psychosis). The pervasive pattern of differences was not due to strong correlations among variables; the mean absolute correlation between variables for both the psychosis and suicidality vignettes was .16. Mean differences were greater for the psychosis compared to the suicidality vignette for five of six corresponding pairs (anger was the exception). Figure 1 displays absolute effect sizes for CIT versus non-CIT differences.

Figure 1. Absolute Effect Sizes (d) for CIT versus Non-CIT Group Differences in Scales Measuring the Six Key Constructs.

Effect sizes for knowledge and opinions about mental illnesses (top two bars) were not linked to video or written vignettes. Otherwise, lighter bars pertain to variables linked to the psychosis and darker bars to the suicidality vignettes. For simplicity, only the 10 (of 13) vignette variables that significantly distinguished the groups are shown. Effect sizes between .20 and .50 (indicated with vertical gray lines) are regarded as small (weak) and those between .50 and .80 as medium (moderate).

Regarding differences in other key variables, except for the stigmatizing attitudes scores derived from the semantic differential scales, differences were significant (all p<.001) for the remaining variables—of these, the effect size was weak for five and moderate for three (self-efficacy, de-escalation skills, and referral decisions linked to the psychosis vignette). All correlations between corresponding items across vignettes were strong, with a mean r=.64 (.57–.71), though mean differences were greater for the psychosis than the suicidality vignette.

Quintile of time since training was largely unassociated with the variables in Table 1. Of 28 correlations, only the two involving de-escalation skills (both vignettes) were significant; r=.19 (p=.003) and r=.18 (p=.005). Specifically, for the psychosis and suicidality vignettes, mean de-escalation skills scores increased monotonically, from 3.12 to 3.35, and from 3.10 to 3.26, respectively, for the 1st–5th quintiles.

Discussion

Controlling for covariates such as years of education, personal/family experience with mental health treatment, and empathy, CIT-trained officers had consistently better scores on knowledge, diverse attitudes toward serious mental illnesses and their treatments, self-efficacy, social distance stigma, de-escalation skills, and referral decisions. Effect sizes for some of these—including self-efficacy, de-escalation skills, and referral decisions pertaining to psychosis, which are arguably most central to the problems that CIT seeks to address—were in the moderate range. Importantly, given that officers had completed CIT training a median of 22 months prior to the research assessment, these findings are particularly impressive and confirm that previously reported improvements in knowledge, attitudes, stigma, and self-efficacy immediately after training (30,31) do in fact persist. These results suggest officer-level effectiveness of CIT. Now, the more difficult task is to address immediate, short-term, and perhaps even long-term outcomes of subjects with whom officers interact, including improved safety and less use of force, reduced arrests (i.e., pre-booking jail diversion), enhanced case finding and referral and mental health and criminal justice outcomes, as well as system-level effects of CIT (e.g., criminal justice cost savings).

Although each of our six key constructs are meaningful to CIT, de-escalation skills are of particular importance given that the “criminalization” of mental illnesses may be prominently related to impulsivity or emotionally motivated responses to perceived provocation (32), rather than untreated symptoms alone (33); thus, de-escalation may be critical to advancing jail diversion. Enhanced referral decisions, when joined with improvements in mental health services, represents a crucial officer-level outcome of CIT training given arguments that “criminalization” inappropriately blames officers, many of whom use arrest and detention as a “mercy booking” in an attempt to provide subjects with mental health services in jail because of perceived unavailability or ineffectiveness of the mental health system (34).

We acknowledge several methodological limitations. First, all CIT-trained officers were from a single state, which relies upon a relatively standardized curriculum. However, Georgia’s CIT program is guided by the core elements of the CIT model (35), suggesting that results may be broadly generalizable. Second, whether enhanced knowledge and more positive attitudes towards people with serious mental illnesses affect encounter resolutions remains unknown. Self-report of de-escalation skills and referral decisions is clearly a proxy for actual behaviors during an interaction. Although we linked most of our measures to contextualized, realistic vignettes to optimize validity, it is not known if the perceived enhanced de-escalation skills translate into safer resolutions of crises in the field.

Improving police responses to persons with serious mental illnesses is now a national priority in the law enforcement/criminal justice sector (36) as well as the mental health community. CIT is a police-based (but mental health and advocacy supported) exemplar for addressing this priority. Whereas the use of mental health courts has recently been shown to meet public safety objectives in terms of lower re-arrest rates and fewer incarceration days (37), CIT represents a pre-booking approach that may also impact these and diverse other outcomes. The present findings demonstrate that CIT training of police officers results in substantial and persisting improvements in officers’ knowledge, attitudes, and skills. Research should also address other outcomes that may accompany our documented officer-level findings, especially safer outcomes for both citizens and officers (e.g., less agitation and reduced use of force), as well as more appropriate dispositions in terms of both reduced arrests (i.e., pre-booking jail diversion) and enhanced case-finding and referral to mental health services, which are topics of the article that follows (reference). Such research would determine whether CIT is an effective mental health service augmentation beyond its now proven beneficial effects for officers.

Acknowledgment:

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute of Mental Health of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01 MH082813. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lamb HR, Weinberger LE, DeCuir WJ: The police and mental health. Psychiatric Services 53:1266–1271, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Deane MW, Steadman HJ, Borum R, Veysey BM, Morrissey JP: Emerging partnerships between mental health and law enforcement. Psychiatric Services 50:99–101, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Borum R, Deane MW, Steadman HJ, Morrissey J: Police perspectives on responding to mentally ill people in crisis: perceptions of program effectiveness. Behavioral Sciences and the Law 16:393–405, 1998 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wells W, Schafer JA: Officer perceptions of police responses to persons with a mental illness. Policing: An International Journal of Police Strategies & Management 29:578–601, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teplin LA, Pruet NS: Police as streetcorner psychiatrist: managing the mentally ill. International Journal of Law and Psychiatry 15:139–156, 1992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vermette HS, Pinals DA, Appelbaum PS: Mental health training for law enforcement professionals. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 33:42–46, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dupont R, Cochran S: Police response to mental health emergencies—barriers to change. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 28:338–344, 2000 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steadman HJ, Deane MW, Borum R, Morrissey JP: Comparing outcomes of major models of police responses to mental health emergencies. Psychiatric Services 51:645–649, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Compton MT, Broussard B, Munetz M, Oliva JR, Watson AC: The Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) Model of Collaboration between Law Enforcement and Mental Health. New York: Novinka/Nova Science Publishers, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cochran S, Deane MW, Borum R: Improving police response to mentally ill people. Psychiatric Services 51:1315–1316, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bower DL, Pettit G: The Albuquerque Police Department’s Crisis Intervention Team: A Report Card. FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin 70:1–6, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hails J, Borum R: Police training and specialized approaches to respond to people with mental illnesses. Crime and Delinquency 49:52–61, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 13.Oliva JR, Haynes N, Covington DW, Lushbaugh DJ, Compton MT: Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) Programs. In: Compton MT, Kotwicki RJ, eds. Responding to Individuals with Mental Illnesses. Sudbury, Massachusetts: Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Inc.: 33–45, 2006 [Google Scholar]

- 14.Oliva JR, Compton MT: A statewide Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) initiative: evolution of the Georgia CIT program. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 36:38–46, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Compton MT, Bahora M, Watson AC, Oliva JR: A comprehensive review of extant research on Crisis Intervention Team (CIT) programs. Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law 36:47–55, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Levy SR, Freitas AL, Salovey P: Construing action abstractly and blurring social distinctions: implications for perceiving homogeneity among, but also empathizing with and helping, others. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 83:1224–1238, 2002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Compton MT, Hankerson-Dyson D, Broussard B: Development, item analysis, and initial reliability and validity of a multiple-choice knowledge of mental illnesses test for lay samples. Psychiatry Research 189:141–148, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cohen J, Struening EL: Opinions about mental illness in the personnel of two large mental hospitals. Journal of Abnormal Social Psychology 64:349–360, 1962 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Struening EL, Cohen J: Factorial invariance and other psychometric characteristics of five opinions about mental illness factors. Educational and Psychological Measurement 23:289–298, 1963 [Google Scholar]

- 20.Taylor SM, Dear MJ, Hall GB: Attitudes toward the mentally ill and reactions to mental health facilities. Social Science and Medicine 13:281–290, 1979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Taylor SM, Dear MJ: Scaling community attitudes toward the mentally ill. Schizophrenia Bulletin 7:225–240, 1981 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Broussard B, Krishan S, Hankerson-Dyson D, Husbands L, Stewart-Hutto T, Compton MT: Development and initial reliability and validity of four self-report measures used in research on interactions between police officers and individuals with mental illnesses. Psychiatry Research 189:458–462, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Corrigan PW, River LP, Lundin RK, Wasowski KU, Campion J, Mathison J, Goldstein H, Gagnon C, Bergman M, Kubiak MA: Predictors of participation in campaigns against mental illness stigma. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease 187:378–380, 1999 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Corrigan PW: An attribution model of public discrimination toward persons with mental illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 44:162–179, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Russell D: The Causal Dimension Scale: a measure of how individuals perceive causes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 42:1137–1145, 1982 [Google Scholar]

- 26.Russell DW, McAuley E, Tarico V: Measuring causal attributions for success and failure: a comparison of methodologies for assessing causal dimensions. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 52:1248–1257, 1987 [Google Scholar]

- 27.McAuley E, Duncan TE, Russell DW: Measuring causal attributions: The Revised Causal Dimension Scale (CDSII). Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 18:566–573, 1992 [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilkinson L, Task Force on Statistical Inference: Statistical methods in psychology journals: guidelines and explanations. American Psychologist 54:594–604, 1999 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Cohen J: Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences. 2nd Ed. Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1988 [Google Scholar]

- 30.Compton MT, Esterberg ML, McGee R, Kotwicki RJ, Oliva JR: Crisis intervention team training: changes in knowledge, attitudes, and stigma related to schizophrenia. Psychiatric Services 57:1199–1202, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Bahora M, Hanafi S, Chien VH, Compton MT: Preliminary evidence of effects of Crisis Intervention Team training on self-efficacy and social distance. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research 35:159–167, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Junginger J, Claypoole K, Laygo R, Crisanti A: Effects of serious mental illness and substance abuse on criminal offenses. Psychiatric Services 57:879–882, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Peterson J, Skeem JL, Hart E, Vidal S, Keith F: Analyzing offense patterns as a function of mental illness to test the criminalization hypothesis. Psychiatric Services 61:1217–1222, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fisher WH, Grudzinskas AJ: Crisis intervention teams as the solution to managing crises involving persons with serious psychiatric illnesses: does one size fit all? Journal of Police Crisis Negotiations 10:58–71, 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dupont R, Cochran S, Pillsbury S. Crisis Intervention Team Core Elements. Memphis, TN: The University of Memphis School of Urban Affairs and Public Policy, Department of Criminology and Criminal Justice, CIT Center; 2007. http://www.citinternational.org/images/stories/CIT/SectionImplementation/CoreElements.pdf (Accessed July 26, 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 36.Improving Responses to People with Mental Illnesses: Tailoring Law Enforcement Initiatives to Individual Jurisdictions. New York: Council of State Governments Justice Center; 2010 [Google Scholar]

- 37.Steadman HJ, Redlich A, Callahan L, Clark Robbins P, Vesselinov R: Effect of mental health courts on arrest and jail days: a multisite study. Archives of General Psychiatry 68:167–172, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]