Abstract

Treating patients with eating disorders can be challenging for therapists, as it requires the establishment of a strong therapeutic relationship. According to the literature, therapist characteristics may influence intervention outcomes. The aim of this systematic review was to identify and synthesize existing literature on therapist interpersonal characteristics that could affect psychotherapy relationship or outcomes in the context of eating disorder treatment from both patients’ and therapists’ perspectives. We conducted a systematic search using electronic databases and included both qualitative and quantitative studies from 1980 until July 2023. Out of the 1230 studies screened, 38 papers met the inclusion criteria and were included in the systematic review. The results indicate that patients reported therapist’s warmth, empathic understanding, a supportive attitude, expertise in eating disorders, and self-disclosure as positive characteristics. Conversely, a lack of empathy, a judgmental attitude, and insufficient expertise were reported as therapist negative characteristics which could have a detrimental impact on treatment outcome. Few studies have reported therapist’s perceptions of their own personal characteristics which could have an impact on treatment. Therapists reported that empathy and supportiveness, optimism, and previous eating disorder experience were positive characteristics. Conversely, clinician anxiety, a judgmental attitude, and a lack of objectivity were reported as negative characteristics that therapists felt could hinder treatment. This systematic review offers initial evidence on the personal characteristics of therapists that may affect the treatment process and outcomes when working with patients with eating disorders.

Key words: eating disorders, therapist characteristics, empathy, expertise, systematic reviews

Introduction

Eating disorders (EDs) are severe psychiatric conditions that encompass anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating disorder (BED), and other specified feeding and eating disorders (OSFED). These clinical conditions are characterized by a persistent disruption of eating-related behaviors, leading to significant alterations in food consumption. This is accompanied by subsequent severe physical consequences and psychosocial impairments (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). EDs can have a significant impact on physical, psychological, and social functioning, leading to a reduced quality of life and increased healthcare utilization (Ágh et al., 2016). The psychopathology of eating disorders is described within a continuum ranging from underconsumption to overconsumption. Maladaptive eating patterns can include extreme or abnormal eating habits, as well as dieting or restrictive behaviors. The global prevalence and impact of eating disorders are constantly increasing, affecting at least 9% of women and 2% of men (Galmiche et al., 2019).

In the last two decades, considerable progress has been made in developing effective treatments for ED. Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Enhanced Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBTE), and Interpersonal Psychotherapy (IPT) are recommended for the treatment of bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, and, to a lesser extent, atypical eating disorders (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2004). However, meta-analytic evidence showed that any bona fide psychotherapy is equally effective in treating EDs (Grenon et al., 2019) and there has been a recent call to improve the accessibility, affordability, and scalability of digital mental health treatments (Lattie et al., 2022). This call has gained even greater relevance since the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, which has led to an increase in the prevalence of eating disorder symptoms (Bonfanti et al., 2023; Schneider et al., 2023) and significant disruptions in clinical services (Sideli et al., 2021).

The treatment of EDs poses a significant challenge for clinicians due to certain intrinsic characteristics that can impact the likelihood of achieving positive treatment outcomes. Patients with EDs tend to underestimate the severity of their symptoms and have low motivation for treatment, which may lead to elevated dropout rates and deteriorating outcomes (Fernàndez-Aranda et al., 2021). According to Turner et al. (2015), adherence to treatment and the ability to establish a strong working alliance are crucial for a successful treatment of eating disorders. The working alliance, as proposed by Gelso (2014), constitutes one of the three factors that make up the therapeutic relationship, together with the real relationship and the transference/countertransference. Among these three dimensions, the working alliance is the factor that has been most studied in the literature and on which there are more empirical data in the context of the therapeutic relationship (Gelso, 2014; Lo Coco et al., 2011). Although there is promising evidence that a positive alliance can enhance the outcomes of psychotherapy for EDs (Werz et al., 2022), there is still a need to develop tailored treatments to meet the challenges of eating disorders. In recent years, significant research interest has been given to the examination of common therapeutic factors which may account for a significant portion of treatment outcomes (Wampold, 2015). Several attempts have been made over the years to systematize these common factors, with varying results (e.g. Wampold & Owen, 2021). However, there is still a lack of consensus among experts in the field, and a high risk of overlapping within psychological constructs remains.

Personal characteristics of the therapist have long been recognized as a cross-cutting factor in classifications of common factors in psychotherapy which influence treatment outcome (Barkham et al., 2017). Since Luborsky and colleagues (1985) early studies on psychotherapy outcomes, it has become clear that there are differences between therapists in terms of the outcome of the patients’ treatments. Subsequent studies have reinforced the relevance of the therapist effect, indicating that some therapists achieve more favorable outcomes than others. This therapist effect can account for around 5% of the variance in outcome and is strongly associated with other therapy process constructs, such as the therapeutic alliance (Nissen-Lie et al., 2023; Wampold & Owen, 2021). Some recent reviews and meta-analyses have tried to identify and summarize therapist characteristics that may influence treatment outcome and the therapeutic relationship. For example, Lingiardi et al. (2018) emphasized the influence of personal characteristics of the therapist, such as attachment, interpersonal styles, and personality traits, on the outcomes of interventions in psychodynamic psychotherapies. Heinonen and Nissen-Lie (2020) identified the therapist socio-emotional traits, such as empathy, warmth, positive regard, communication skills, and the ability to deal with criticism, as stronger predictors of positive outcomes (within the therapist effect). However, few studies have specifically focused on analyzing these therapist factors in the treatment of EDs, despite previous literature suggesting that some personal characteristics of therapists may be crucial in determining therapeutic outcomes in patients with EDs. For example, some studies have identified the therapist’s empathy, emotional attunement, and self-awareness as crucial qualities that could improve therapeutic outcomes. In particular, therapists working with people with ED need to be able to understand and address the emotional experiences of their clients. Empathy has been shown to be associated with improved therapeutic outcomes in the treatment of eating disorders (Oyer et al., 2016). Moreover, therapists who are emotionally attuned are better able to understand their clients’ perspectives, by improving the therapeutic alliance and treatment outcome (Le Grange et al., 2007). Self-awareness is also a crucial quality for therapists who work with individuals with eating disorders. It involves understanding one’s own thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, which can help therapists avoid projecting their own biases onto clients and provide more effective treatment (Aronson & Anderson, 2010). The therapist’s countertransference also seems to play a role in the therapeutic process of treating patients with EDs. Specifically, there is preliminary evidence that therapists may experience greater special/overinvolved countertransference when the patient had higher trauma severity (Groth et al., 2020), and that therapist’s emotional response may be influenced by patient variables such as sexual abuse or self-harm (Colli et al., 2015).

The therapist’s ability to establish a strong therapeutic alliance is crucial to the success of treating EDs. This alliance should be based on trust, mutual respect, and collaboration between the therapist and the client (Mallinckrodt et al., 2014). Several therapist characteristics have been identified as important for defining the therapeutic alliance, including empathy, genuineness, respect and unconditional positive regard (Lambert and Barley, 2001). Furthermore, therapists’ interpersonal characteristics, such as an engaging and encouraging relational style, have been shown to enhance the development of a positive alliance in short-term therapies, whereas constructive coping techniques have demonstrated more favorable effects on a positive alliance in long-term therapies (Heinonen et al., 2014). Conversely, some studies have found that therapists’ interpersonal characteristics, such as keeping a distance, being disconnected, or indifferent, could have a negative impact on the working alliance in long-term treatments (Hersoug et al., 2009). It is important to note, however, that research investigating the relationship between therapist characteristics and the therapeutic alliance in treating EDs is still in its early stages (Werz et al., 2022).

It is also worth noting that previous studies examining both beneficial and adverse experiences of psychotherapy have found that the latter are less commonly reported than positive experiences. Patients may hesitate to express feelings of dissatisfaction regarding therapy or their therapist (Castonguay et al., 2010). It is important to note that this research is still in its infancy. However, there is increasing attention to patients’ perceptions of negative experiences in psychotherapy (De Smet et al., 2019; Hardy et al., 2019; Alfonsson et al., 2023). According to a qualitative meta-analysis by Smith et al. (2014), clients’ negative experiences in psychotherapy primarily stem from negative assessments of the therapist’s personal qualities and behavior. These include instances where the therapist fails to listen, is judgmental, or devalues the client. Additionally, clients may perceive the therapist as disconnected from the therapy or the client, which can result in a lack of empathy, distrust, or a lack of interpersonal rapport. A more recent study showed that patients highlighted four areas of therapist variables that could lead to treatment failure: therapists’ negative traits (such as being inflexible, unengaged, unemphatic, insecure), unprofessionalism (such as violating personal boundaries, breaking confidentiality, non-transparency), incompetence (such as poor assessment or understanding, poor knowledge, too passive), and mismatch (therapist–patient mismatch) (Alfonsson et al., 2023). Although there are few studies that specifically focus on the positive (and negative) personal qualities of therapists in the treatment of EDs, research investigating user satisfaction and the experiences of both patients and therapists during the recovery process has yielded some intriguing findings. For example, in the treatment of patients with AN, positive treatment experiences are associated with therapists who are perceived as impartial, understanding, non-judgmental, warm, reliable, active, flexible, respectful, caring, validating, and loving (Colton & Pistrang, 2004). Patients have expressed gratitude for their therapist’s adaptability in tailoring treatment to their specific needs (Fairburn et al., 2015). Patients with BED have reported valuing the support provided by their therapists, while also experiencing negative feelings of stigmatization due to their disorder (Wilfley et al., 2002). On the other hand, therapists have reported their efforts to establish a warm and supportive treatment environment (Fairburn et al., 2015). However, the self-assessment bias of psychotherapists remains an issue. For example, it was found that therapists’ bias in assessing their own facilitative interpersonal skills such as emotional expression, warmth, acceptance was higher than those reported by observer ratings (Longley et al., 2023). Although some research suggests the role of therapist characteristics in the treatment of EDs, there is still a lack of a comprehensive view on this relevant topic. The purpose of this systematic review is to identify and synthesize existing literature on therapist interpersonal characteristics and their impact on therapy relationship or outcome for patients with EDs. In addition, it is valuable to analyze therapist characteristics from both the patient and clinician perspective to identify any differences between the two perspectives. These findings may help clinicians and researchers to address current limitations in ED interventions.

Methods

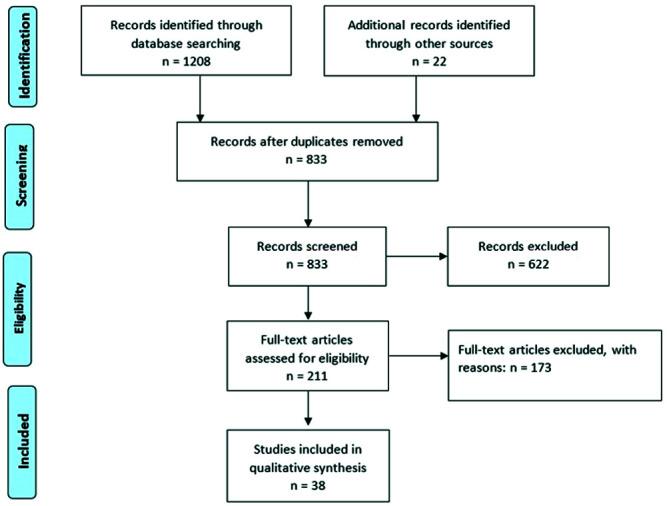

A systematic evaluation of the literature was conducted following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines (Moher et al., 2009) and using the following electronic databases: Embase, Medline, PsychINFO and PsychARTICLE through Ovid.

Three parallel searches were conducted; the first two searches aimed to identify the therapist’s characteristics throughout the several types of eating disorders treatments and therapeutic approaches, and the last one wishes to identify the patient’s and/or therapist’s own satisfaction with the therapist’s characteristics reported. In the first search, the following keywords were used: charact, trait, effect, dimension, factor, variable, influence, style, personality, attitude, temperament, credibility. The search was repeated using the following synonyms for therapist: Psychotherapist, Counsel, Mentor, Facilitator, Psychologist, Trainee, Clinical. In the second search, the following keywords were used: warm, empath, feeling, attachment, authentic, genuine. Also, in this case the research was repeated using the following therapist synonyms:

Psychotherapist, Counsel, Mentor, Facilitator, Psychologist, Trainee, Clinical. In the third search, the satisfaction keyword was used for patient or client or participant and therapist or Psychotherapist, Counsel, Mentor, Facilitator, Psychologist, Trainee, Clinical. All three searches were used in combination with the following keywords: anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorders. Both searches were limited to journal articles, published with human subjects and written in the English language between 1980 and January 2023. An updating of the literature was performed last July 2023.

Eligibility criteria

Studies were included in the systematic review if they met the following eligibility criteria: i) a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa and/or bulimia nervosa and/or binge eating according to the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5th Edition (DSM 5) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), or the International Classification of Diseases 10th edition (ICD-10) (World Health Organization, 1992), ii) at any stage of life (childhood, adolescence, adulthood), iii) in any therapy setting (Inpatient, outpatient, day-care, private sessions, psychotherapy); iv) from any study design (RCTs, case control studies, correlational studies, longitudinal studies) and lastly v) for both quantitative and qualitative studies. A mandatory criterion was used for all searches, vi) the presence of patient/client and/or therapists (other therapists’ definition) personal characteristics related to the treatment process and/or outcomes. The personal characteristics from the included studies were self-reported by therapist or reported by patients/clients. G.A and A.S. conducted the literature search and screened all papers for eligibility for the inclusion criteria. Disagreements were resolved through consensus meetings with G.L.

Study selection

The three literature searches identified 1208 papers in total. 22 studies were added using the reference lists from other studies. 397 duplicates were removed, and 622 papers were excluded because they did not meet the inclusion criteria following screening of titles and abstracts. 173 papers were excluded after reading the full texts. The final eligible papers were 38 (Banasiak et al., 2007; Bjork et al., 2009; Brown et al., 2014; Brown & Nicholson Perry, 2018; Clinton et al., 2004; Clinton, 2001; Colton & Pistrang, 2004; Daniel et al., 2015; De la Rie et al., 2006; De la Rie et al., 2008; De Vo s et al., 2016; Escobar-Koch et al. 2010; Fox & Diab, 2013; Gowers et al., 2010; Gulliksen et al., 2012; Halvorsen & Heyerdahl, 2007; Lose et al., 2014; Ma, 2008; Offord et al., 2006; Oyer et al., 2016; Paulson-Karlsson et al., 2006; Pettersen & Rosenvinge 2002; Poulsen et al., 2010; Rance et al., 2017; Reid et al., 2008; Rorty et al., 1993; Rosenvinge & Klusmeier, 2000; Sheridan & McArdle, 2015; Smith et al. 2016; Stockford et al. 2018; Tritt et al., 2015; Vanderlinden et al., 2007; Warren et al., 2013; Wasil et al., 2019; Whitney et al., 2008; Wright & Hacking 2012; Zaitsoff et al. 2015; Zaitsoff et al., 2016). A flow-chart of the studies included in the systematic review is presented in Figure 1. Screening was performed by three members of the research team (GA, AS, GL). As most of the included studies were observational and not RCTs, we did not perform a meta-analysis of the association between therapist characteristics and therapy outcome. The increased risk of bias and the high level of heterogeneity between studies would prevent us from establishing a precise estimate of the main effects.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of studies included in the present review.

Quality assessment

A quality appraisal for qualitative studies was carried out using the Critical Appraisal Skills Program (CASP) qualitative research checklist by three reviewers (CASP, 2017). A maximum of 10 Ye s were attributed for each study. A quality appraisal for quantitative studies was carried out using a modified version of the Newcastle-Ottawa Scale (Wells et al., 2003). A maximum of 7 points was attributed. Studies were evaluated to be at low risk of bias if the score was 5 to 7, at a moderate risk of bias if the score was 3 or 4, and at high risk of bias if the score was equal or lower than 2 (Supplementary Table 1). Quality assessment was conducted by GA, RCB, and AT. Any discrepancies between reviewers were discussed until an agreement was reached, if needed with the consultancy of the senior author (GLC).

Results

The search resulted in a final selection of 38 articles. All studies were evaluated to be at low risk of bias (Supplementary Table 2). The eligible articles were divided into two sections: the patient’s and therapist’s perspectives based on their own personal characteristics considered necessary for the achievement of treatment outcome or for a valid contribution to the EDs treatment process. For each section (patient and therapist), the characteristics of the therapist have been considered as positive or negative and therefore they are treated separately. 30 articles were focused on patient’s perspective; 18 out of these 30 studies (60%) reported positive characteristics, whereas 3 studies reported negative characteristics of therapist; 9 articles reported both positive and negative characteristics.

Only 4 articles were focused on the therapist’s perspective; 2 studies reported positive characteristics, one study focused on negative characteristics of the therapist, and only 1 article reported both positive and negative characteristics. 4 papers reported both clients’ and therapists’ perspectives respectively. 17 studies included patients with a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa (AN) or eating disorder not otherwise specified (EDNOS) (Brown et al. 2014; Colton & Pistrang, 2004; Fox & Diab, 2013; Gowers et al., 2010; Gulliksen et al. 2012; Halvorsen & Heyerdahl, 2007; Lose et al., 2014; Ma, 2008; Offord et al. 2006; Oyer et al. 2015; Paulson-Karlsson et al. 2006; Rance et al. 2017; Smith et al. 2014; Stockford et al. 2018; Whitney et al., 2008; Wright & Hacking, 2012; Zaitsoff et al., 2016); 4 studies included patients suffering from bulimia nervosa (BN), (Banasiak et al. 2007; Daniel et al. 2015; Poulsen et al. 2010; Rorty et al. 1993); 7 studies included patients with both diagnoses of AN and BN and/or EDNOS, (Bijork et al. 2009; De la Rie et al. 2008; De Vos et al. 2016; Lose et al. 2014; Reid et al., 2008; Sheridan & McArdle, 2015; Tritt et al., 2015; Zaitsoff et al. 2015); and 8 studies were focused on the treatment of general eating disorders (Brown et al., 2018; Clinton, 2001; Clinton et al. 2004; De la Rie et al., 2006; Escobar-Koch et al. 2010; Pettersen & Rosenvinge, 2002; Rosenvinge & Klusmeier, 2000; Vanderlinden et al. 2007; Warren et al. 2013; Wasil et al., 2019).

The majority of patients included in the systematic review were women, with a mean age range from 14.11 to 39.25 years. Regarding the therapist’s perspective, most professionals included from the selected studies were women, with a mean age range from 35.12 to 43.96 years. In the included studies, we found a large variety of clinical intervention directed to EDs, with different psychotherapeutic approaches (e.g., individual and group treatment or integrated interventions based on CBT or psychodynamic treatments). 12 out of 32 studies were based on a multidisciplinary intervention directed to both inpatient and outpatient interventions. Finally, in the eligible studies reported there is an accurate definition of the therapist; most studies involved a multidisciplinary clinical staff (composed by several professional identities with a proper expertise on the EDs treatment). Only nine studies involved clinical psychologists or therapists in the treatment of EDs, and in only one study general practitioners/therapists without a specific EDs background were involved in conducting clinical interventions.

Of the 38 articles checked for the quality assessment, 21 studies were qualitative researches (Banasiak et al., 2007; Colton & Pistrang, 2004; De vos et al., 2016; Escobar-Koch et al., 2010; Fox & Diab, 2013; Gulliksen et al., 2012; Lose et al., 2014; Ma, 2008; Oyer et al., 2016; Poulsen et al., 2010; Offord et al., 2006; Rance et al., 2017; Reid et al., 2008; Rorty et al., 1993; Sheridan & McArdle, 2015; Smith et al., 2016; Stockford et al., 2018; Warren et al., 2013; Whitney et al., 2008; Wright & Hacking, 2012; Zaitsoff et al., 2016), 13 were quantitative researches (Brown et al., 2014; Brown & Perry, 2018; Clinton et al., 2004; de la Rie et al., 2006; Daniel et al., 2015; Halvorsen & Heyerdahl, 2007; Paulson-Karlsson et al., 2006; Rosenvinge & Kuhlefelt Klusmeier, 2000; Tritt et al., 2015; Vanderlinden et al., 2007; Zaitsoff et al., 2015; Clinton, 2001; Wasil et al., 2019), and 4 mixed-method studies (Bjork et al., 2009; Gowers et al., 2010; de la Rie et al., 2008; Pettersen & Rosenvinge, 2002). The majority of studies used interviews or semi structured interviews to collect data. Few studies adopted validated measures to assess therapist characteristics. The nature of the interviews or semistructured interviews was mainly focused on the assessment of the treatment process. Most of the included studies adopted an inductive nature, avoiding author bias in data collection and allowing to patients the chance to explore the treatment process through broad treatment domains defined a priori by the study authors.

Supplementary Table 1 reports the quality ratings of the included studies. Overall, all studies (21 qualitative research and 17 quantitative research or mixed methods) fully satisfied the criteria for robustness.

In Table 1 and Table 2 are reported the characteristics of the included studies, for clients’ and therapists’ perceptions, respectively.

Table 1.

General characteristics of studies with clients’ perspectives (N=34).

| Author, year | Country | Type of study | N (% women) | Mage | Diagnosis and setting of the client | Type of treatment | Definition of therapist |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banasiak et al., 2007 | Australia | Retrospective and qualitative study | 36(100) | 29.5 | BN, primary care | Guided self-help treatment | Clinical staff |

| Bjork et al., 2009 | Sweden | Longitudinal naturalistic study | 82 (97.6) | 23.8 | AN, BN, EDNOS inpatients, outpatients, day-patients | Individual, family, group psychotherapy | n/a |

| Clinton, 2001 | Sweden | Multicentric and longitudinal study | 461 (98.9) | 24.5 | AN=115; BN=146; BED=64; EDNOS=136 inpatients, outpatients, day-patients | Individual, group, family CBT, PDT | Clinical and medical staff |

| Clinton et al., 2004 | Sweden | Multicentric and longitudinal study | 469 (98.5) | 25.4 | AN=94; BN=175; BED=25; EDNOS=175 inpatient, outpatients, day patients | Individual, group FT, ET | Clinical and medical staff |

| Colton & Pistrang, 2004 | UK | Phenomenological study | 19(100) | 15.4 | AN inpatients | n/a | Clinical staff |

| De la Rie et al., 2006 | Netherlands | Qualitative study | 304 | (97.3) | 28.7 | AN=44; BN=43; n/a EDNOS=69; Former ED=148 outpatients | Clinical and medical staff |

| De la Rie et al., 2008 | Netherlands | Mixed method | 304 | 16.04 | AN, BN and EDNOS | n/a | Clinical and medical staff |

| De Vo s et al., 2016 | Netherlands | Qualitative study | 205(98) | 27.25 | AN=98; EDNOS=72; BN=34 outpatients | Consult with a recovered therapist besides possible therapy from other treatment disciplines | Clinical psychologists |

| Escobar-Koch et al., 2010 | United States & UK | Cross-national study & qualitative and exploratory study | USA | 144 (97.2) 30.1 26 UK 150 (96.7) | .6 ED | n/a | Clinical staff |

| Fox & Diab, 2013 | UK | Phenomenological study | 6(100) | 27.0 | Chronic AN (can) inpatients, outpatients | Psychological therapy (various approaches) | Clinical staff |

| Gowers et al., 2010 | UK | RCT | 215 (92.5) | 14.11 | AN inpatients | CBT therapy | Clinical and medical staff |

| Gulliksen et al., 2012 | Norway | Phenomenological, descriptive, and qualitative study | 38(100) | 28.3 | AN inpatients and outpatients | n/a | Clinical and medical staff |

| Halvorsen & Heyerdahl, 2007 | Norway | Retrospective study | 46(100) | 14.9 | AN inpatients or outpatients | CFT | Psychotherapists |

| Lose et al., 2014 | UK | RCT (retrospective and qualitative study) | 17 (n/a) | 29.5 | AN=10; EDNOS-AN= 7 | MANTRA | Psychotherapists |

| Ma, 2008 | HongKong | Qualitative study | 29(100) | n/a | AN | FT | Psychotherapists |

| Offord et al., 2006 | UK | Retrospective and qualitative study | 7(100) | n/a | AN inpatients | n/a | Clinical staff |

| Oyer et al., 2016 | Colorado | Phenomenological and qualitative study | 8 (87.5) | 39.25 | AN inpatients, outpatients | n/a | Clinical staff |

| Paulson-Karlsson et al., 2006 | Sweden ( | Mixed method TSS with 11 open-ende questions) | 32(100) d | 15.0 | AN outpatients | SFT | Psychotherapists |

| Poulsen et al., 2010 | Copenhagen | Qualitative study | 15(100) | 26.1 | BN | Individual PDT | Psychotherapists |

| Pettersen & Rosenvinge, 2002 | Norway | Qualitative study | 48(100) | 27.6 | AN, BN, BED | Professional treatmen | t n/a |

| Rance et al., 2017 | UK | Retrospective and qualitative study | 12(100) | 31.5 | AN inpatients or outpatients | CBT, CAT, PDT, IT | Clinical and medical staff |

| Reid et al., 2008 | UK | Qualitative study | 20(95) | n/a | AN and BN outpatients | n/a | Clinical and medical staff |

| Rorty et al., 1993 | USA | Qualitative study | 40(100) | 25.65 | BN | n/a | Clinical and medical staff |

| Rosenvinge & Klusmeier, 2000 Norway | Cross-sectional | 321 (n/a) | 29.3 | AN, BN, BED inpatients, outpatient | Individual, group | CBT, FT | Clinical staff |

| Sheridan & McArdle, 2015 | Ireland | Qualitative study | 14(100) | 23.21 | AN and BN inpatients, outpatients | n/a | n/a |

| Smith et al., 2016 | UK | Qualitative study | 21(100) | 25.2 | AN inpatients CB | Individual and group T therapies, counselli dietetic management | Clinical staff ng, |

| Stockford et al., 2018 | UK | Phenomenological and qualitative study | 6(100) | 36.0 | AN inpatients, outpatients | A variety of clinical interventions | Clinical staff |

| Tritt et al., 2015 | USA, Canada, Multicenter and UK Retrospective study | 105 | (98.1) | 26.2 | AN, BN, EDNOS | CBT, FT, DBT, IPT, PDT | Psychotherapists |

| Vanderlinden et al., 2007 | Belgium | Quantitative | 132 (97.7) | 24.6 | AN=56; BN=65; BED=11 inpatients, outpatient | CBT (group format) combined with a FT | Clinical and medical staff |

| Wasil et al., 2019 | USA | Qualitative study | 11(100) | 33.09 | Patients recovered from an ED at least 1 year prior the study | n/a | Psychotherapists and peers |

| Whitney et al., 2008 | UK | Qualitative study | 19(100) | 30.3 | AN inpatients | CRT | Psychotherapists |

| Wright & Hacking, 2012 | UK | Phenomenological study | 6(100) | n/a | AN day care patients | n/a | Clinical staff |

| Zaitsoff et al., 2015 | Canada | Qualitative study | 34(100) | 16.33 | AN=14, BN=4, EDNOS=15 inpatients, outpatients | Individual, group FT; dietician, school counselling | n/a |

| Zaitsoff et al., 2016 | Canada | Qualitative study | 21(100) | 16.3 | AN=15 and subthreshold AN=6 inpatients, outpatients | Individual, group FT dietitian, school counselling | n/a |

CBT, cognitive behavioral therapy; PDT, psychodynamic therapy; ET, expressive therapy; FT, family therapy; CFT, conjoint family therapy; MANTRA, Maudsley model for treatment of adults with anorexia nervosa; SFT, separated family therapy; CAT, cognitive analytic therapy; DBT, dialectical behavioral therapy; IPT, interpersonal therapy; CRT, cognitive remediation therapy.

Table 2.

General characteristics of studies with therapists’ perspectives (N=8).

| Author, year | Country | Type of study | N (% women) | Mage | Diagnosis and setting of the client | Type of treatment | Definition of therapist |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown et al., 2014 | UK | Cross-sectional | 100(80) | n/a | AN outpatients | CBT | Clinical and medical staff |

| Brown & Perry, 2018 | Australia | Cross-sectional | 100(95) | 36.29 | ED | CBT | Psychologists |

| Daniel et al., 2015 | The Netherlands | RCT | 12(75) | n/a | BN | PPT, CBT | Clinical and medical staff |

| De la Rie et al., 2008 | The Netherlands | Quantitative and qualitative study | 73 (64.38) | 42 | AN, BN, EDNOS outpatients | CBT, biomedical therapy PAT, client-centered therapies STA | , Clinical and medical staff |

| De Vo s et al., 2016 | The Netherlands | Qualitative study | 26(100) | 35.12 | AN=98; BN=34; EDNOS=72 outpatients | Consultation with a recovered therapist besides possible therapy from other treatment | Psychologists |

| Oyer et al., 2016 | Colorado Ph | enomenological and qualitative study | 7 (85.7) | n/a | AN inpatients, outpatients | n/a | Clinical staff |

| Warren et al., 2013 | USA | Qualitative study | 139 (96.4) | 43.96 | ED multiple settings | CBT, PDT, eclectic/integrative and, humanistic thrapies, medication/nutrition interventions | Clinical staff |

| Wright & Hacking, 2012 | UK Phe | nomenological study | 7(100) | n/a | AN day care patients | n/a | Clinical staff |

Client’s point of view: positive characteristics

Thirty-four studies reported the positive characteristics related to the therapist identified by clients/patients (Table 3).

Table 3.

Positive and negative characteristics of therapists (as reported by eating disorders clients).

| Author, year | Positive (+) or negative (-) characteristics | Therapists’ personal characteristics reported by clients | Personal characteristics measure | Treatment outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banasiak et al., 2007 | + | Empathic | Ad hoc questionnaire, | Therapeutic relationship |

| + | Supportive | Evaluation of treatment | ||

| - | Arrogance | questionnaire | ||

| - | Criticism/Judgmental | |||

| - | Lack of empathy | |||

| Bjork et al., 2009 | - | Lack of empathy | Treatment Clie | nts’ satisfaction drop-out rates |

| Satisfaction scale | ||||

| Clinton, 2001 | + | Supportive | Treatment | Clients’ satisfaction |

| Satisfaction scale | ||||

| Clinton et al., 2004 | + | Supportive | Treatment | Client’s satisfaction |

| Satisfaction scale | ||||

| Colton & Pistrang, 2004 | + | Empathic | Semi-structured interviews | Recovery from EDs |

| + | Supportive | |||

| De la Rie et al., 2006 | + | Empathic | Questionnaire for eating disorders | Therapeutic relationship |

| + | Supportive | Drop-out rates | ||

| - | Lack of expertise | |||

| - | Lack of empathy | |||

| De la Rie et al., 2008 | + | Empathic | Questionnaire for Eating Disorders | Client’s satisfaction |

| + | Supportive | |||

| De Vos et al., 2016 | + | Supportive | Ad hoc questionnaire | Hope on EDs recovery |

| + | Expertise in EDs | |||

| + | Authentic | |||

| + | Empathic | |||

| Escobar-Koch et al., 2010 | + | Supportive | Ad hoc questionnaire | Client’s satisfaction |

| + | Empathic | |||

| + | Expertise in EDs | |||

| Fox & Diab, 2013 | + | Expertise in EDs | Interviews | Trust in EDs therapists |

| + | Empathic | Exacerbation of feeling of isolation | ||

| - | Pessimism | |||

| - | Overwhelmed | |||

| Gowers et al., 2010 | + | Expertise in EDs | Ad hoc questionnaire | Client’s satisfaction |

| + | Empathic | |||

| + | Friendly | |||

| Gulliksen et al., 2012 | + | Empathic | Interviews | Client’s satisfaction |

| + | Expertise in EDs | Therapeutic relationship | ||

| + | Humor | |||

| - | Lack of empathy | |||

| - | Prejudiced attitude | |||

| - | Authoritarianism | |||

| - | Passivity | |||

| - | Pampering | |||

| Halvorsen & Heyerdahl, 2007 | + | Empathic | Perception of therapist(s) | Improvement in EDs symptoms |

| + | Expertise in EDs | |||

| Lose et al., 2014 | + | Empathic | Semi-structured interviews | Client’s satisfaction |

| + | Supportive | |||

| + | Expertise in EDs | |||

| - | Lack of empathy | |||

| - | Lack of expertise | |||

| Ma, 2008 | + | Empathic | Interviews | Recovery in EDs |

| + | Supportive | |||

| + | Friendly | |||

| Offord et al., 2006 | - | Lack of empathy | Semi-structured interviews | Client’s satisfaction |

| - | Accusational | |||

| - | Patronising | |||

| Oyer et al., 2016 | + | Emotional self-disclosure (crying) | Semi-structured interviews | Therapeutic relationship |

| + | Empathic | |||

| + | Authentic | |||

| + | Humor | |||

| + | Expertise in EDs | |||

| - | Lack of empathy | |||

| - | Judgmental/invalidating attitude | |||

| Paulson-Karlsson et al., 2006 | + | Empathic | Treatment satisfaction scale | Client’s satisfaction |

| + | Expertise in EDs | |||

| Poulsen et al.,2010 | + | Empathic | Client experience interview | Client’s satisfaction |

| + | Supportive | |||

| + | Expertise in EDs | |||

| Pettersen & Rosenvinge, 2002 | + | Empathic | Interviews | Therapeutic relationship |

| + | Supportive | |||

| + | Availability | |||

| Rance et al., 2017 | + | Empathic | Semi-structured interviews | Client’s satisfaction |

| + | Self-disclosure | Therapeutic relationship | ||

| - | Lack of empathy | |||

| - | Judgmental attitude | |||

| Reid et al., 2008 | + | Empathic | Semi-structured interviews | Client’s satisfaction |

| + | Supportive | |||

| Rorty et al., 1993 | + | Empathic | Semi-structured interviews | Recovery in EDs |

| Rosenvinge & Kuhlefelt Klusmeier, | 2000 + | Empathic | Ad hoc questionnaire | Client’s satisfaction |

| + | Expertise in EDs | |||

| Sheridan & McArdle, 2015 | + | Empathic | Semi-structured interviews | Therapeutic relationship |

| + | Expertise in EDs | |||

| - | Lack of empathy | |||

| Smith et al. 2014 | + | Supportive | Semi-structured interviews | Therapeutic relationship |

| + | Empathic | Recovery process | ||

| - | Judgmental attitude | |||

| Stockford et al., 2018 | - | Judgmental attitude | Semi-structured interviews | Recovery process |

| - | Lack of empathy | (low self-esteem) | ||

| Tritt et al., 2015 | + | Emotional self-disclosure (crying) | Ad hoc questionnaire | Adherence to treatment |

| + | Self-disclosure (crying) | Recovery process | ||

| Vanderlinden et al., 2007 | + | Supportive | EDs questionnaire | |

| + | Expertise in EDs | |||

| Wasil et al., 2019 | + | Self-disclosure | Semi-structured interviews | Recovery process |

| Whitney et al., 2008 | + | Empathic | Feedback letter | Therapeutic relationship |

| + + | Supportive Expertise in EDs | |||

| Wright & Hacking, 2012 | + | Empathic | Semi-structured schedule | Therapeutic relationship |

| + | Authentic | |||

| + | Maternalism | |||

| + | Optimism | |||

| Zaitsoff et al., 2015 | + | Empathic | Interviews | Therapeutic relationship |

| + | Self-disclousure | |||

| Zaitsoff et al., 2016 | + | Empathic | Semi-structured interviews | Therapeutic relationship |

| + | Supportive | Engagement in treatment |

EDs, eating disorders.

Therapist’s warmth and empathic understanding

In 26 studies, the emphatic characteristic of the therapist was seen as a positive characteristic in relation to the definition of the therapeutic relationship, in contributing to the recovery process from an Eds (Colton & Pistrang, 2004; De Vo s et al., 2016; Ma, 2008; Halvorsen and Heyerdahl, 2007; Rorty et al., 1993), clients’ satisfaction (De la Rie et al., 2008; Escobar-Koch et al., 2010; Growers et al., 2010; Gulliksen et al., 2012; Lose et al., 2014; Paulson-Karlsson et al., 2006; Poulsen et al., 2010; Rance et al., 2017; Reid et al., 2008; Rosenvinge and Klusmeier, 2000), trust in therapist (Fox & Diab, 2013), and adherence/engagement to treatment (Zaitsoff et al., 2016).

Supportive attitude

In 17 studies, the supportive attitude of the therapist, i.e. the ability to be a helpful source of support and encouragement for the patient, particularly during the most difficult phases of treatment, was seen as a positive characteristic in relation to therapeutic relationship definition (Banasiak et al., 2007; De la Rie et al., 2006; Pettersen & Rosenvinge, 2002; Smith et al., 2016; Whitney et al., 2008; Zaitsoff et al., 2016) and the contribution to the recovery process from an Eds (Colton & Pistrang, 2004; De Vo s et al., 2016; Ma, 2008; Vanderlinden et al., 2007 ), and clients’ satisfaction (Clinton et al., 2001; 2004; De la Rie et al., 2008; Escobar-Koch et al., 2010; Lose et al., 2014; Poulsen et al., 2010; Reid et al., 2008).

Therapist’s expertise in eating disorders

In 13 studies the therapist’s expertise in EDs, i.e. the ability to convey clinical expertise and knowledge about key issues related to EDs (e.g.: nutrition, medical issues), was seen as a positive characteristic in relation to the definition of the therapeutic relationship (Oyer et al., 2016; Sheridan & McArdle, 2015; Whitney et al., 2008), in contributing to the recovery process from an EDs (De Vo s et al., 2016; Halvorsen & Heyerdahl, 2007; Vanderlinden et al., 2007), clients’ satisfaction (Escobar-Koch et al., 2010; Gowers et al., 2010; Gulliksen et al., 2012; Paulson-Karlsson et al., 2006; Poulsen et al., 2010; Rosenvinge & Klusmeier, 2000) and trust in therapist (Fox & Diab, 2013).

Self-disclosure

In 6 studies, therapists’ self-disclosure, defined as the willingness to share some aspects of themselves and their emotional inner experiences with the patient, was seen as a positive characteristic in relation to the therapeutic relationship (Oyer et al., 2016, Zaitsoff et al., 2015), clients’ satisfaction (Lose et al., 2014; Rance et al., 2017), or in relation to the recovery process from an EDs (Wasil et al., 2019) and to higher adherence/engagement to treatment (Tritt et al., 2015).

Others positive characteristics

In 3 studies the authenticity of the therapist, which is seen as the ability to respond intuitively to the patient’s needs beyond the standard treatment protocols, was positively related to the definition of the therapeutic relationship (Oyer et al., 2016; Wright & Hacking, 2012) and to the recovery from an Eds (De Vo s et al., 2016). In 2 studies the therapist’ friendly attitude was considered as a positive characteristic in relation to the recovery process from an EDs (Ma, 2008) and clients’ satisfaction (Gowers et al., 2010). In only 1 study (Oyer et al., 2016) the therapist’ sense of humor was considered a positive characteristic in relation to the definition of the therapeutic relationship, and the therapist’s vitality (Gulliksen et al., 2012) was related to client satisfaction. Finally, the therapist’ availability (Pettersen & Rosenvinge, 2002), optimism (Wright & Hacking, 2012), and maternalistic attitudes (Wright & Hacking, 2012, referring to the role of protecting, feeding and nurturing) were considered positively associated to the definition of the therapeutic relationship.

Client’s point of view: negative characteristics.

Thirteen studies reported the therapists’ negative characteristics identified by clients/patients during their EDs treatments (Table 3).

Therapist’s lack of warmth and empathic understanding

In 10 studies the therapist’s lack of warmth and empathic understanding was considered as an unhelpful and negative characteristic and associated with a poor therapeutic relationship (Banasiak et al., 2007; Gulliksen et al., 2012; Oyer et al., 2016; Rance et al., 2017), client’s dissatisfaction (Bjork et al., 2009; Lose et al., 2014; Offord et al., 2006), drop-out rates (De la Rie et al., 2006; Sheridan & McArdle, 2015) and a worsening in the recovery process (Stockford et al., 2018).

Therapist’s judgmental attitude

In 6 studies the therapist’s judgmental attitude was considered negative and associated to a poor therapeutic relationship (Banasiak et al., 2007; Gulliksen et al., 2012 Oyer et al., 2016; Rance et al., 2017), and in a worsening in the recovery process (Smith et al., 2016; Stockford et al., 2018).

Therapist’s lack of expertise

In 2 studies the therapist’s lack of expertise was considered as an unhelpful/negative characteristic associated to drop-out rates (De la Rie et al., 2006) and client’s dissatisfaction (Lose et al., 2014) respectively.

Other negative characteristics

The therapist’s arrogance, authoritarianism, passivity and pampering were negatively associate to therapeutic relationship definition (Banasiak et al., 2007; Gulliksen et al., 2012). Therapist’s pessimism and overwhelmed tendency were considered as an unhelpful and negative characteristic causing a feeling of isolation in patients (Fox & Diab, 2006). Finally, Offord and colleagues (2006) found that the therapist’s accusating and patronising attitudes were considered as unhelpful and negative characteristics associated with client’s dissatisfaction.

Therapist’s point of view: positive characteristics

Seven studies reported the positive characteristics identified by therapists in their experiences of EDs treatments conduction (Table 4).

Table 4.

Positive and negative characteristics of therapists (as reported by therapists).

| Author, year | Positive (+) or negative (-) characteristics | Therapists’ personal characteristics reported by clients | Personal characteristics measure | Treatment outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Brown et al., 2014 | - | Clinician anxiety | Ad hoc questionnaire | Lack of hope in the therapeutic relationship; no improvement in EDs symptoms |

| Daniel et al., 2015 | + - | Happy/Enthusiastic feelings Negative/unpleasant feelings | Feeling word checklists | Client attachment security Therapeutic relationship |

| Brown & Perry, 2018 | + + | Self-efficacy Optimism | Personal efficacy beliefs Eating disorder scale Therapeutic optimism eating disorder scale | Treatment fidelity |

| De la Rie et al., 2008 | + + | Supportive Empathic | Ad hoc questionnaire | Therapeutic relationship |

| De Vos et al., 2016 | + + + | Empathic Authenticity Expertise | Ad hoc questionnaire | Hope on recovery |

| Oyer et al., 2016 | + - | Self-disclosure Lack of objectivity | Semi-structured interviews | Therapeutic relationship |

| Warren et al., 2013 | + | Personal history of eating disorders | Ad hoc questionnaire | Increasing empathy |

| Wright & Hacking, 2012 | + | Transparent | Semi-structured schedule | Therapeutic relationship |

EDs, eating disorders.

Two studies found that the therapist’s empathic characteristic and supportive attitude were positively associate to the therapeutic relationship definition and a sense of hope towards recovery (De la Rie et al., 2008; De Vo s et al., 2016).

In two studies the presence of happy and enthusiastic feelings and optimism were considered positive characteristics in relation to client attachment security and treatment fidelity (Daniel et al., 2015; Brown et al., 2018), whilst the therapist’s authenticity was positively associated to a sense of hope towards recovery (De Vo s et a., 2016). Finally, therapists reported that their expertise on EDs treatment was considered a positive characteristic in relation to the client’s sense of hope towards recovery (De Vo s et a., 2016). Therapist’s self-disclosure and the capacity to be transparent with the clientswere seen as positive characteristics in relation to the therapeutic relationship (Oyer et al., 2016; Wright & Hacking, 2012). Finally, in the study of Warren et al., (2013) the therapist’s personal history of eating disorders was considered positively associated with increased empathy.

Therapist’s perspective: negative characteristics

Only three studies reported the negative characteristics identified by therapists in their experiences of EDs treatments conduction (Table 4). In two of these studies authors reported negative or unpleasant feelings and emotions and the lack of experience in EDs related to the absence of improvement in EDs (Brown et al., 2014; Daniel et al., 2015). In only one study (Oyer et al., 2016) the lack of objectivity was considered a negative characteristic in relation to poor therapeutic relationship.

Discussion

This systematic review is the first to synthesize the existing literature on therapists’ personal characteristics and their impact on specific treatment aspects for patients with eating disorders. A total of 38 studies were reviewed, reporting both qualitative and quantitative data on positive and negative views from patients and/or therapists. The studies included in the review take into consideration a wide variety of treatments, including theoretical orientations, settings, clinical practitioners (such as psychologists, psychotherapists, psychiatrists, and clinical staff), and patients’ diagnostic criteria (AN, BN, EDNOS, or EDs). The results of the review indicate that therapists’ personal characteristics, such as empathic and supportive attitudes, authenticity, tendency to self-disclose, and level of expertise in ED treatment, are considered by both patients and therapists to be positive determinants in the treatment of EDs. These characteristics have an impact on therapy outcome and the quality of the therapeutic relationship. Our findings on empathy, supportive attitude, and authenticity/transparency align with the results of the APA Task Force on Evidence-Based Relationships and Responsiveness, which identified these relational qualities of the therapist as effective factors in the development of the therapeutic relationship and as central components of change (Norcross, 2018). Previous meta-analyses (Elliott et al., 2018; Farber et al., 2018; Kolden et al., 2018) have indicated that therapist attributes, such as empathy, positive regard, and genuineness, are essential prerequisites for successful treatment. Our findings underline their relevance in the treatment of EDs. Some studies have confirmed the importance of therapists’ self-disclosure as a positive characteristic that can be important in fostering the therapy relationship and positively influencing the recovery process of individuals with eating disorders (see Patmore, 2020). Our findings seem to be in line with previous research literature, which has emphasized how the therapist’s willingness to share some aspects of themselves and their inner experiences with the patient can play a constructive role in fostering the therapeutic relationship, promoting patient disclosure, and alleviating feelings of shame and eating symptoms (Simonds & Spokes, 2017).

Our findings suggest that patients’ perceptions of their therapist’s expertise in the specific area of EDs may be associated with more positive perceptions of the therapeutic relationship, greater hope for recovery, greater client satisfaction, and greater trust in the therapist. These findings regarding patients’ perceptions of treatment credibility are consistent with recent literature which has highlighted its correlation with more positive treatment outcomes (Costantino et al., 2019). Therapists should consider patients’ perceptions of their own expertise in EDs as a ‘non-specific’ belief factor that could affect the quality of treatment and explore this aspect in clinical interventions and professional training. Furthermore, patients reported that they perceived the positive attributes of the therapist, such as a friendly attitude, sense of humor, optimism, availability, and caring behavior, as beneficial aspects of therapy. Humor and optimism are often considered beneficial in psychotherapy as they can help to establish a non-defensive clinical relationship, foster a sense of belonging, promote adherence to treatment, and facilitate the implementation of novel intervention strategies to achieve optimal outcomes (Bergmann, 2013; Edward et al., 2014).

It is common knowledge that patients with eating disorders may exhibit resistance and non-cooperation, especially during the initial stages of treatment. They may also struggle to accept their condition and may feel pressured into treatment by family members or significant others (Paulson-Karlsson et al., 2006). Therefore, it is important to establish a trusting and welcome setting to cultivate an effective therapeutic relationship. Bordin (1979) highlighted the crucial significance of establishing a bond when constructing the therapeutic relationship, a concept that can be understood as ‘being with’ (Solomon, 1972). Additionally, it is essential to establish the goals and tasks of therapy. When working with people with EDs, the negotiation of these two aspects inevitably involves elements of care and nurturing. From this perspective, the availability and care of the therapist can play an important role in therapy (Wright, 2015). As noted by Clarkson (2003), the therapist takes on a supportive role during the negotiation process, becoming a ‘safe other’ for the patient with EDs, ensuring a sense of protection and security. This promotes hope in recovery and a way out of eating disorders, similar to how parental care promotes independence (Wright, 2015).

Conversely, therapists also acknowledge that enthusiasm, selfefficacy, and a prior history of EDs can be positive personal characteristics from the patients’ view. This aligns with recent studies which aimed to understand how healed individuals can contribute to patient change. There is some evidence that people with previous experiences of EDs can help patients feel understood and improve clinical outcomes and treatment attendance (Albano et al., 2021). The literature suggests that enthusiasm and self-efficacy have a positive effect on treatment. Enthusiasm is linked to the clinician’s investment in the therapeutic relationship, which strengthens it (Ackerman & Hilsenroth, 2003). Self-efficacy is related to the potential to promote behavioral change in the patient, and to increase the chances of recovery by observing a functional model (Brown & Nicholson Perry, 2018).

Regarding the perception of negative therapist characteristics, our study found that the negative personal qualities reported by patients were arrogance, a judgmental attitude, lack of empathy, lack of expertise, pessimism, prejudice, authoritarianism, passivity, pampering, accusation, and patronizing. The results suggest that the mentioned characteristics could have an adverse effect on the establishment of a genuine therapeutic relationship, which is linked to treatment outcome (Lo Coco et al., 2011; Gelso et al., 2018) in psychotherapy. Our findings seem in line with previous research on clients’ negative experiences during treatment, showing that therapist errors/behaviors are connected with obstructive aspects of the therapy relationship (Vybíral et al., 2023). However, the relationship between negative client ratings of therapist qualities and therapy outcomes remains unclear, and further research is needed to establish this potential relationship.

Regarding therapists’ perceptions, our findings indicate that clinician anxiety, negative emotions, and a lack of objectivity were identified as adverse factors that could affect patient outcomes. Clinicians often experience emotions such as anxiety, lack of objectivity, or more generally negative feelings, including stress, hostility, and anger when working with individuals with EDs. These difficulties are often linked to the intrinsic characteristics and behaviors of ED patients. While patients with ED may expect a high level of responsiveness from clinicians, especially in the early stages of treatment, they may not necessarily trust them. This ambivalence may lead to a dichotomy between attention-seeking and devaluing attitudes; for clinicians, this can lead to patients being perceived as manipulative, subversive and obstructive (Palmer, 2000), resulting in frustration and negative emotions (Kaplan & Garfinkel, 1999). Negative feelings experienced by clinicians towards patients with EDs may significantly affect treatment outcomes (Thompson-Brenner et al., 2012). Considering these factors, it is crucial for clinicians who work with ED patients to engage in regular supervision and consultation (Warren et al., 2009). However, there is a lack of research on the quality, quantity, or nature of supervision activities in ED treatment, especially in addressing clinician emotions.

This systematic review examined the factors that influence the psychotherapeutic relationship in the treatment of eating disorders. The current findings suggest that personal characteristics play a central role in the process of change (Constantino et al., 2019; Elliott et al., 2018; Delgadillo et al., 2020). Finally, a noteworthy finding that requires further investigation is that although most positive characteristics were recognized by both patients and therapists, the negative characteristics varied between the two perspectives. Patients and therapists often differ in their evaluation of treatment effectiveness and the factors they consider significant in therapy (Compare et al., 2016; Werbart et al., 2022). Furthermore, research indicates that this difference is even more noticeable when treatments are unsuccessful (Gold & Striker, 2011). This difference may explain why, unlike positive traits, there is a greater divergence in the opinions of clinicians and patients regarding which personal characteristic of therapists have a negative impact on treatment. Similarly, the literature on therapists’ self-assessment bias (Longley et al., 2023) suggested that therapists tend to overestimate their skills in relation to their professional role and that this may be seen as an unconscious attempt to maintain motivation, particularly when working with difficult patients, such as EDs (Walfish et al., 2012). Overall, this study supports the findings by Heinonen and Nissen-Lie (2020) which showed that the socio-emotional qualities of the therapist, such as empathy, warmth, and positive regard, contribute to improved treatment outcome. Our results add the importance of addressing these factors in the psychological treatment of patients with EDs.

This review has several strengths. Firstly, it enriches the existing literature on therapists’ personal characteristics and their impact on specific aspects of the treatment of patients with eating disorders. Secondly, it brings together two distinct streams of literature on psychotherapy, one focusing on the patient perspective and the other on the therapist perspective. Another strength is the good quality of the included studies, none of which were coded as high risk of bias. However, this review has some significative limitations. Firstly, the limited number of included studies did not allow to draw firm conclusions on the role of therapy characteristics in the treatment of specific disorders such as AN or BN. Secondly, the included studies varied in therapeutic approach and patient characteristics, which may account for the heterogeneity in results. Several eligible studies analyzed therapist characteristics and treatment outcomes using non-standardized or ad hoc questionnaires or analyzed patient narratives. This qualitative approach may raise some concerns about our ability to establish correlations between the therapist characteristics and the outcomes reported in the studies. Moreover, the field is dominated by a lack of consensus on the relevance of therapist characteristics and further studies are needed to explore patients’ and clinicians’ views of therapist characteristics that can impact on the therapeutic relationship and treatment outcome through an exploratory approach. This qualitative approach may allow the development of more appropriate tools to identify and measure the influence that these characteristics have on the therapeutic process and outcome in the treatment of EDs. Finally, there are very few studies in the literature which have investigated personal characteristics perceived negatively by clinicians. This could potentially affect the generalizability of the results obtained from this review.

The clinical implications of this systematic review are noteworthy. Therapists who work with patients with eating disorders should be aware of the personal factors that can affect both the therapeutic relationship and treatment outcomes. Therapists should prioritize in establishing a warm and bonding therapeutic relationship with their patients. They should also be capable of discussing treatment goals and tasks in an accepting and non-judgmental manner. Additionally, our findings suggest the importance of customizing interventions to the personal and interpersonal characteristics of both members in the therapy dyad. Personalizing interventions by promoting interpersonal factors may be associated with a reduction in a fundamental disease-maintenance factor in ED, i.e. interpersonal distress (Brugnera et al., 2018; Lo Coco et al., 2012). Personalization can also serve as a potential predictor of treatment adherence and the development of a stronger therapeutic relationship. However, there is a lack of evidence regarding which interpersonal characteristics of therapists should be considered when developing patient-tailored interventions for EDs. These results highlight the significance of comprehensive training and ongoing supervision for clinicians working with ED patients. Measures like establishing clearer boundaries, providing emotional management training for therapists, increasing awareness of factors that will contribute to the patient’s goals, and implementing mentalizing and metacommunication abilities can aid clinicians in effectively handling negative patient experiences and preventing them from negatively affecting the therapeutic relationship.

Conclusions

The studies included in this systematic review highlight the importance of the therapist’s personal qualities as a critical factor in treating patients with eating disorders. This systematic review offers initial evidence on the therapist’s personal characteristics which may affect the treatment process. The findings support the importance of socio-emotional characteristics, as highlighted by Heinonen & Nissen-Lie (2020), which are also relevant in the context of ED treatments. However, this review has also revealed a gap in the research on how negative characteristics may affect treatment from the clinician’s perspective, as well as the high variability in the methods and research designs used. This indicates a strong need for further research to gain a better understanding of how therapist personal characteristics can impact the therapeutic process and contribute to positive changes in patients during therapy.

Funding Statement

Fundings: G.A. and A.T. are co-funded by EU–PON Ricerca e Innovazione 2014–2020 DM 1062/2021.

References

- Ackerman S. J., Hilsenroth M. J., (2003). A review of therapist characteristics and techniques positively impacting the therapeutic alliance. Clinical Psychology Review, 23(1), 1–33. doi: 10.1016/S0272-7358(02)00146-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ágh T., Kovács G., Supina D., Pawaskar M., Herman B. K., Vokó Z., Sheehan D. V., (2016). A systematic review of the health-related quality of life and economic burdens of anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, and binge eating disorder. Eating and Weight Disorders - Studies on Anorexia, Bulimia and Obesity, 21(3), 353–364. doi: 10.1007/s40519-016-0264-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albano G., Cardi V., Kivlighan D. M., Ambwani S., Treasure J., Lo Coco G. (2021). The relationship between working alliance with peer mentors and eating psychopathology in a digital 6-week guided self-help intervention for anorexia nervosa. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 54(8), 1519– 1526. doi: 10.1002/eat.23559 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alfonsson S., Fagernäs S., Sjöstrand G., Tyrberg M. J., (2023). Psychotherapist variables that may lead to treatment failure or termination. A qualitative analysis of patients’ perspectives. Psychotherapy, 60(4), 431–441. doi: 10.1037/ pst0000503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). doi: 10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596 [Google Scholar]

- Banasiak S. J., Paxton S. J., Hay P.J. (2007). Perceptions of Cognitive Behavioural Guided Self-Help Treatment for Bulimia Nervosa in Primary Care. Eating Disorders, 15(1), 23–40. doi: 10.1080/10640260601044444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barkham M., Lutz W., Lambert M. J., Saxon D. (2017). Therapist effects, effective therapists, and the law of variability. In Castonguay L. G., Hill C. E. (A c. Di), How and why are some therapists better than others? Understanding therapist effects. (pp. 13–36). American Psychological Association. doi: 10.1037/0000034-002 [Google Scholar]

- Barron J. W. (1999). Humor and psyche: Psychoanalytic perspectives. Analytic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Björk T., Björck C., Clinton D., Sohlberg S., Norring C. (2009). What happened to the ones who dropped out? Outcome in eating disorder patients who complete or prematurely terminate treatment. European Eating Disorders Review, 17(2), 109–119. doi: 10.1002/erv.911 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonfanti R. C., Sideli L., Teti A., Musetti A., Cella S., Barberis N., Borsarini B., Fortunato L., Sechi C., Micali N., Lo Coco G. (2023). The Impact of the First and Second Wave of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Eating Symptoms and Dysfunctional Eating Behaviours in the General Population: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients, 15(16), 3607. doi: 10.3390/nu15163607 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bordin E. S. (1979). The generalizability of the psychoanalytic concept of the working alliance. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research & Practice, 16(3), 252–260. doi: 10.1037/h0085885 [Google Scholar]

- Brown A., Mountford V., Waller G. (2014). Clinician and practice characteristics influencing delivery and outcomes of the early part of outpatient cognitive behavioural therapy for anorexia nervosa. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 7, e10. doi: 10.1017/S1754470X14000105 [Google Scholar]

- Brown C. E., Nicholson Perry K. (2018). Cognitive behavioural therapy for eating disorders: How do clinician characteristics impact on treatment fidelity? Journal of Eating Disorders, 6(1), 19. doi: 10.1186/s40337-018-0208-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brugnera A. Lo Coco G., Salerno L. Sutton R. Gullo S. Compare A. Tasca G. A., (2018). Patients with Binge Eating Disorder and Obesity have qualitatively different interpersonal characteristics: Results from an Interpersonal Circumplex study. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 85, 36–41. doi: 10.1016/j.comppsych.2018.06.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Castonguay L. G., Constantino M. J., McAleavey A. A., Gold-fried M. R., (2010). The therapeutic alliance in cognitive-be-havioral therapy. In The therapeutic alliance: An evidence-based guide to practice. (pp. 150–171). The Guilford Press. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen M., Hewitt-Taylor J. (2006). Empowerment in nursing: Paternalism or maternalism? British Journal of Nursing, 15(13), 695–699. doi: 10.12968/bjon.2006.15.13.21478 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clarkson P. (2005). The therapeutic relationship (2. ed., reprint). Whurr. [Google Scholar]

- Clinton D. (2001). Expectations and Experiences of Treatment in Eating Disorders. Eating Disorders, 9(4), 361–371. doi: 10.1080/106402601753454921 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clinton D., Björck C., Sohlberg S., Norring C. (2004). Patient satisfaction with treatment in eating disorders: Cause for complacency or concern? European Eating Disorders Review, 12(4), 240–246. doi: 10.1002/erv.582 [Google Scholar]

- Colli A., Speranza A. M., Lingiardi V., Gentile D., Nassisi V., Hilsenroth M. J., (2015). Eating disorders and therapist emotional responses. Journal of Nervous and Mental Disease, 203, 843–849. 10.1097/NMD.0000000000000379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colton A., Pistrang N. (2004). Adolescents’ experiences of in-patient treatment for anorexia nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 12(5), 307–316. doi: 10.1002/erv.587 [Google Scholar]

- Compare A., Tasca G. A., Lo Coco G., Kivlighan D. M., (2016). Congruence of group therapist and group member alliance judgments in emotionally focused group therapy for binge eating disorder. Psychotherapy, 53(2), 163–173. doi: 10.1037/pst0000042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Constantino M. J., Boswell J. F., Coyne A. E., (2021). Patient, therapist, and relational factors. In Bergin and Garfield’s handbook of psychotherapy and behavior change: 50th anniversary edition, 7th ed. (pp. 225–262). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Constantino M. J., Coyne A. E., Boswell J. F., Iles B. R., Vîslă A. (2019). Promoting Treatment Credibility. In Constantino M. J., Coyne A. E., Boswell J. F., Iles B. R., Vîslă A., Psychotherapy Relationships that Work (pp. 495– 521). Oxford University Press. doi: 10.1093/med-psych/ 9780190843953.003.0014 [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme. (2017). CASP checklists. Retrieved from https://www.casp-uk.net/checklists [Google Scholar]

- Daniel S. I. F., Lunn S., Poulsen S. (2015). Client attachment and therapist feelings in the treatment of bulimia nervosa. Psychotherapy, 52(2), 247–257. doi: 10.1037/a0038886 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Rie S., Noordenbos G., Donker M., Van Furth E. (2006). Evaluating the treatment of eating disorders from the patient’s perspective. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 39(8), 667–676. doi: 10.1002/eat.20317 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Rie S., Noordenbos G., Donker M., Van Furth E. (2008). The quality of treatment of eating disorders: A comparison of the therapists’ and the patients’ perspective. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 41(4), 307–317. doi: 10.1002/eat.20494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Smet M. M., Meganck R., Van Nieuwenhove K., Truijens F. L., Desmet M. (2019). No Change? A Grounded Theory Analysis of Depressed Patients’ Perspectives on Non-improvement in Psychotherapy. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 588. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Vos J. A., Netten C., Noordenbos G. (2016). Recovered eating disorder therapists using their experiential knowledge in therapy: A qualitative examination of the therapists’ and the patients’ view. Eating Disorders, 24(3), 207–223. doi: 10.1080/10640266.2015.1090869 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delgadillo J., Branson A., Kellett S., Myles-Hooton P., Hardy G. E., Shafran R. (2020). Therapist personality traits as predictors of psychological treatment outcomes. Psychotherapy Research, 30(7), 857–870. doi: 10.1080/10503307. 2020.1731927 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edward K.-L. (A c. Di). (2014). Mental health nursing: Dimensions of praxis. Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Elliott R., Bohart A. C., Watson J. C., Murphy D. (2018). Therapist empathy and client outcome: An updated meta-analysis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 399–410. doi: 10.1037/ pst0000175 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Koch T., Banker J. D., Crow S., Cullis J., Ringwood S., Smith G., Van Furth E., Westin K., Schmidt U. (2010). Service users’ views of eating disorder services: An international comparison. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 43(6), 549–559. doi: 10.1002/eat.20741 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairburn C. G., Bailey-Straebler S., Basden S., Doll H. A., Jones R., Murphy R., O’Connor M. E., Cooper Z. (2015). A transdiagnostic comparison of enhanced cognitive behaviour therapy (CBT-E) and interpersonal psychotherapy in the treatment of eating disorders. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 70, 64–71. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.04.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farber B. A., Suzuki J. Y., Lynch D. A., (2018). Positive regard and psychotherapy outcome: A meta-analytic review. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 411–423. doi: 10.1037/pst0000171 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Aranda F., Treasure J., Paslakis G., Agüera Z., Giménez M., Granero R., Sánchez I., Serrano-Troncoso E., Gorwood P., Herpertz-Dahlmann B., Bonin E. M., Monteleone P., Jiménez-Murcia S. (2021). The impact of duration of illness on treatment nonresponse and drop-out: Exploring the relevance of enduring eating disorder concept. European eating disorders review : the journal of the Eating Disorders Association, 29(3), 499–513. doi: 10.1002/erv.2822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox J. R., Diab P. (2015). An exploration of the perceptions and experiences of living with chronic anorexia nervosa while an inpatient on an Eating Disorders Unit: An Interpretative Phenomenological Analysis (IPA) study. Journal of Health Psychology, 20(1), 27–36. doi: 10.1177/1359105313497526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galmiche M., Déchelotte P., Lambert G., Tavolacci M. P., (2019). Prevalence of eating disorders over the 2000–2018 period: A systematic literature review. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 109(5), 1402–1413. doi: 10.1093/ ajcn/nqy342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelso C. J., Kivlighan D. M., Markin R. D., (2018). The real relationship and its role in psychotherapy outcome: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 434–444. doi: 10.1037/ pst0000183 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gelso C. (2014). A tripartite model of the therapeutic relationship: theory, research, and practice. Psychotherapy research : journal of the Society for Psychotherapy Research, 24(2), 117–131. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2013.845920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold J., Stricker G. (2011). Failures in psychodynamic psychotherapy. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 67(11), 1096–1105. doi: 10.1002/jclp.20847 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowers S., Clark A., Roberts C., Byford S., Barrett B., Griffiths A., Edwards V., Bryan C., Smethurst N., Rowlands L., Roots P. (2010). A randomised controlled multicentre trial of treatments for adolescent anorexia nervosa including assessment of cost-effectiveness and patient acceptability – the TOuCAN trial. Health Technology Assessment, 14(15). doi: 10.3310/hta14150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grenon R., Carlucci S., Brugnera A., Schwartze D., Hammond N., Ivanova I., Mcquaid N., Proulx G., Tasca G. A., (2019). Psychotherapy for eating disorders: A meta-analysis of direct comparisons. Psychotherapy Research, 29(7), 833–845. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2018.1489162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groth T., Hilsenroth M. J., Gold J., Boccio D., Tasca G. A., (2020). Therapist factors related to the treatment of adolescent eating disorders. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 51(5), 517–526. doi: 10.1037/pro0000308 [Google Scholar]

- Gulliksen K. S., Espeset E. M. S., Nordbø R. H. S., Skårderud F., Geller J., Holte A. (2012). Preferred therapist characteristics in treatment of anorexia nervosa: The patient’s perspective. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 45(8), 932–941. doi: 10.1002/eat.22033 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Halvorsen I., Heyerdahl S. (2007). Treatment perception in adolescent onset anorexia nervosa: Retrospective views of patients and parents. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 40(7), 629–639. doi: 10.1002/eat.20428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hardy G. E., Bishop-Edwards L., Chambers E., Connell J., Dent-Brown K., Kothari G., O’hara R., Parry G. D., (2019). Risk factors for negative experiences during psychotherapy. Psychotherapy Research, 29(3), 403–414. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2017.1393575 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen E., Lindfors O., Härkänen T., Virtala E., Jääskeläinen T., Knekt P. (2014). Therapists’ Professional and Personal Characteristics as Predictors of Working Alliance in ShortTerm and Long-Term Psychotherapies. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 21(6), 475–494. doi: 10.1002/ cpp.1852 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinonen E., Nissen-Lie H. A., (2020). The professional and personal characteristics of effective psychotherapists: A systematic review. Psychotherapy Research, 30(4), 417–432. doi: 10.1080/10503307.2019.1620366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hersoug A. G., Høglend P., Havik O., Vo n Der Lippe A., Monsen J. (2009). Therapist characteristics influencing the quality of alliance in long-term psychotherapy. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 16(2), 100–110. doi: 10.1002/c pp. 605 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A. S., Garfinkel P. E. (1999). Difficulties in Treating Patients with Eating Disorders: A Review of Patient and Clinician Variables. The Canadian Journal of Psychiatry, 44(7), 665–670. doi: 10.1177/070674379904400703 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolden G. G., Wang C.-C., Austin S. B., Chang Y., Klein M. H., (2018). Congruence/genuineness: A meta-analysis. Psychotherapy, 55(4), 424–433. doi: 10.1037/pst0000162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lambert M. J., Barley D. E., (2001). Research summary on the therapeutic relationship and psychotherapy outcome. Psychotherapy: Theory, Research, Practice, Training, 38(4), 357–361. doi: 10.1037/0033-3204.38.4.357 [Google Scholar]

- Lattie E.G., Stiles-Shields C., Graham A.K. An overview of and recommendations for more accessible digital mental health services. Nat Rev Psychol 1, 87–100 (2022). doi: 10.1038/s44159-021-00003-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Grange D., Crosby R. D., Rathouz P. J., Leventhal B. L., (2007). A Randomized Controlled Comparison of Family-Based Treatment and Supportive Psychotherapy for Adolescent Bulimia Nervosa. Archives of General Psychiatry, 64(9), 1049. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.9.1049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lingiardi V., Muzi L., Tanzilli A., Carone N. (2018). Do therapists’ subjective variables impact on psychodynamic psychotherapy outcomes? A systematic literature review. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 25(1), 85–101. doi: 10.1002/ cpp.2131 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Coco G., Gullo S., Prestano C., Gelso C. J., (2011). Relation of the real relationship and the working alliance to the outcome of brief psychotherapy. Psychotherapy, 48(4), 359–367. doi: 10.1037/a0022426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lo Coco G., Gullo S., Scrima F., Bruno V. (2012). Obesity and interpersonal problems: an analysis with the interpersonal circumplex. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 19(5), 390–398. doi: 10.1002/cpp.753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Longley M., Kästner D., Daubmann A., Hirschmeier C., Strauß B., Gumz A. (2023). Prospective psychotherapists’ bias and accuracy in assessing their own facilitative interpersonal skills. Psychotherapy (Chicago, Ill.), 60(4), 525–535. doi: 10.1037/pst0000506 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lose A., Davies C., Renwick B., Kenyon M., Treasure J., Schmidt U. on behalf of the MOSAIC trial group. (2014). Process Evaluation of the Maudsley Model for Treatment of Adults with Anorexia Nervosa Trial. Part II: Patient Experiences of Two Psychological Therapies for Treatment of Anorexia Nervosa. European Eating Disorders Review, 22(2), 131–139. doi: 10.1002/erv.2279 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luborsky L. (1985). Therapist Success and Its Determinants. Archives of General Psychiatry, 42(6), 602. doi: 10.1001/ archpsyc.1985.01790290084010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma J. L. C. (2008). Patients’ Perspective on Family Therapy for Anorexia Nervosa: A Qualitative Inquiry in a Chinese Context. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy (ANZJFT), 29(1), 10–16. doi: 10.1375/anft.29.1.10 [Google Scholar]