Abstract

Background.

Thoracic aortic aneurysms (TAA) and abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) represent related but distinct disease processes. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is known to be significantly upregulated in human TAA and AAA. We hypothesize that loss of IL-6 is protective in experimental TAA and AAA.

Methods.

Murine TAAs or AAAs were created using a novel model in C57/B6 mice by treating the intact aorta with elastase. Cytokine profiles were analyzed with antibody arrays (n = 5 per group). Separately, to determine the role of IL-6, thoracic (n = 7) or abdominal (n = 7) aortas of wild type mice and IL-6 knockout (KO) mice were treated with elastase. Additionally, thoracic animals treated with either the IL-6 receptor antagonist tocilizumab (n = 8) or vehicle (n = 5). Finally, human TAA and AAA were analyzed with human cytokine array.

Results.

Elastase treatment of thoracic aortas yielded dilation of 86.8% ± 9.6%, and abdominal aortas produced dilation of 85.6% ± 16.2%. Murine IL-6, CXCL13, and matrix metalloproteinase-9 were significantly elevated in TAA compared with AAA (p = 0.004, 0.028, and 0.001, respectively). The IL-6KO mice demonstrated significantly smaller TAA size relative to wild type mice (wild type 100.1% versus IL-6KO 76.5%, p = 0.04). The IL-6KO mice did not show protection from AAA (p = 0.732). Pharmacologic inhibition of IL-6 resulted in significant reduction in TAA size (tocilizumab 71.5% ± 13.2% versus vehicle 103.6% ± 20.7%, p = 0.005). Human TAA showed significantly greater IL-6 (p < 0.0001) compared with AAA and normal thoracic and abdominal aorta.

Conclusions.

Interleukin-6 is significantly greater in both murine and human TAA compared with AAA, suggesting fundamental differences in these disease processes. Interleukin-6 receptor antagonism attenuates experimental TAA formation, indicating that IL-6 may be a potential target for human thoracic aneurysmal disease.

Aneurysmal disease of the thoracic and abdominal aorta represent the 15th leading cause of death among people over the age of 55 years [1, 2]. Although morphologically similar, descending thoracic aortic aneurysms (TAA) and abdominal aortic aneurysms (AAA) represent distinct disease processes. The etiology of AAA and de novo TAA remain poorly understood. Common to both descending TAA and AAA is a local inflammatory process leading to degeneration of the aortic media and progressive dilation; however, several fundamental differences between the thoracic and abdominal aorta may account for different responses to injury. The thoracic and abdominal aorta contain cells of distinct embryologic origins [3]. Additionally, the thoracic aorta has greater elastin content and contains more prominent vaso vasora than the abdominal aorta [4-6]. Current nonsurgical therapy for AAA and TAA is aimed at preventing further dilation and includes risk factor reduction and β-adrenergic blockade (for TAA), both with limited efficacy [1, 7].

Interlukin-6 (IL-6) is known to play a role in a wide variety of vascular pathologies, including atherosclerosis and tumor angiogenesis [8-11]. Additionally, serum levels of IL-6 have been linked to both thoracic and abdominal aortic disease [12-14]. We hypothesized there is differential expression of inflammatory cytokines in TAA and AAA. We further hypothesized that IL-6 is critical to both descending TAA and AAA formation.

Material and Methods

All animal protocols were reviewed and approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Virginia, protocol number 3634. Human tissue was collected and used in accordance with Institutional Re-view Board protocol number 17042.

Creation of Murine TAA

Murine TAA were created as we have previously published [5]. Briefly, male C57-black-6 mice between the ages of 8 and 10 weeks were anesthetized with isofluorane. Mice were then intubated under direct tracheal visualization and ventilated with tidal volumes of 200 mL and a rate of 200 breathes per minute. The neck was closed with absorbable suture and the mouse repositioned in the right lateral decubitus position. A left posterolateral thoracotomy was then performed in the fourth to fifth interspace, and the left lung was retracted gently anteriorly to reveal the descending thoracic aorta. The pleura overlying the aorta was removed, and an elastase-soaked (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO) sponge was placed on the exposed aorta. Care was taken not to allow the sponge to come in contact with either the left lung or the right pleura. After 5 minutes, the sponge was removed, and the residual elastase was removed. Measurements of the aorta were taken before and after elastase exposure by video micrometry. The thoracotomy was closed in two layers, and the left lung was reexpanded.

Creation of Murine AAA

Similarly, AAA creation with periadventitial elastase has been previously described [15]. Briefly, C57-B6 mice between 8 and 10 weeks of age were anesthetized with ketamine and xylazine, and a midline laparotomy was performed. The bowl was retracted superiorly, and the retroperitoneum was dissected to expose the infrarenal abdominal aorta. The vena cava was separated from the aorta, and an elastase-soaked sponge was placed directly on the aorta for 5 minutes. After sponge removal, excess elastase was removed, and aortic diameter was measured. The bowel was returned to the peritoneal cavity, and the abdomen was closed in two layers.

All mice were allowed to recover for 3 to 14 days. At the time of harvest, the thoracic or abdominal aortas were exposed in a similar fashion, and video micrometry was used to measure maximum aortic diameter. An undissected, non-elastase-exposed segment of thoracic or abdominal aorta was used for comparison of diameter, thereby accounting for variation in animal growth and variation in the cardiac cycle.

Measurement of Aortic Cytokines

Thoracic and abdominal aortas (n = 5 per group) treated with either full-strength elastase or saline were harvested 7 days postoperatively. Cytokine profiles were analyzed using a murine antibody cytokine array (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN). Tissue was harvested, and the array was performed per the manufacturer′s protocol. Samples were run in duplicate. Densitometric volume was determined by spectophotometry using Thermo Scientific software (Waltham, MA). Similarly, human aortic frozen samples from AAA and TAA as well as normal thoracic and abdominal aorta were analyzed using a human antibody cytokine array (R&D Systems) per the manufacturer′s protocol and analyzed as above.

Measurements of Aortic Interleukin-6

To confirm the results of the murine cytokine arrays, IL-6 levels were determined using a murine IL-6 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay kit (R&D systems), according to the manufacturer′s instructions. The IL-6 levels were determined from separate mice harvested at 3, 7, or 14 days postoperatively for both thoracic and abdominal aneurysms. Samples were run in duplicate.

Comparison of Thoracic and Abdominal Aortic Dilation in IL-6 Knockout Mice

To further define the role of IL-6 in thoracic aneurysm formation, wild type (WT) mice (n = 7 per group) and IL-6 knockout (KO) mice (n = 7 per group [Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME]) underwent either thoracic or abdominal aneurysm procedures (as described above) and were harvested at postoperative days 7 and 14. Percentage dilation was calculated by dividing maximum aneurysmal diameter by the diameter of untreated thoracic or abdominal aorta.

Pharmacologic Inhibition of IL-6

To move toward a translatable result, we examined reproducibility of TAA inhibition seen in our IL-6KO experiments using WT mice and commercially available IL-6 receptor antagonist (tocilizumab; Roche Pharmaceuticals, Basel, Switzerland). The WT mice were given either vehicle (saline) alone (n = 5), or vehicle plus tocilizumab (8 mg/kg per dose; n = 7) by intraperitoneal injection on the day of surgery and 7 days postoperatively. Aortas were harvested on day 14 and preserved as above for histology.

Immunohistochemistry for Human IL-6

Human TAA and AAA aortic tissue and nonaneurysmal abdominal and thoracic aortas were placed in 4% paraformaldehyde overnight. Tissues were rinsed with phosphate-buffered saline (three times for 5 minutes), transferred to 70% ethanol, and then embedded in paraffin. Aortic sections were stained for IL-6 using an IL-6 antibody (sc-7920; Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Dallas, TX), as previously described [5, 16].

Statistical Methods

Statistical analysis was performed using Prism 5 software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). Maximal aortic dilation (%) was calculated as: [maximal aortic diameter — internal control diameter] ÷ internal control diameter * 100%. Values are reported as mean ± SD. Aortic dilation between groups was compared with one-way analysis of variance with post hoc Tukey corrections applied to determine the significance of individual comparisons with α = 0.05. When only two groups were compared, Student′s t test was used for significance.

Results

Cytokine Differences Between Murine TAA Versus AAA

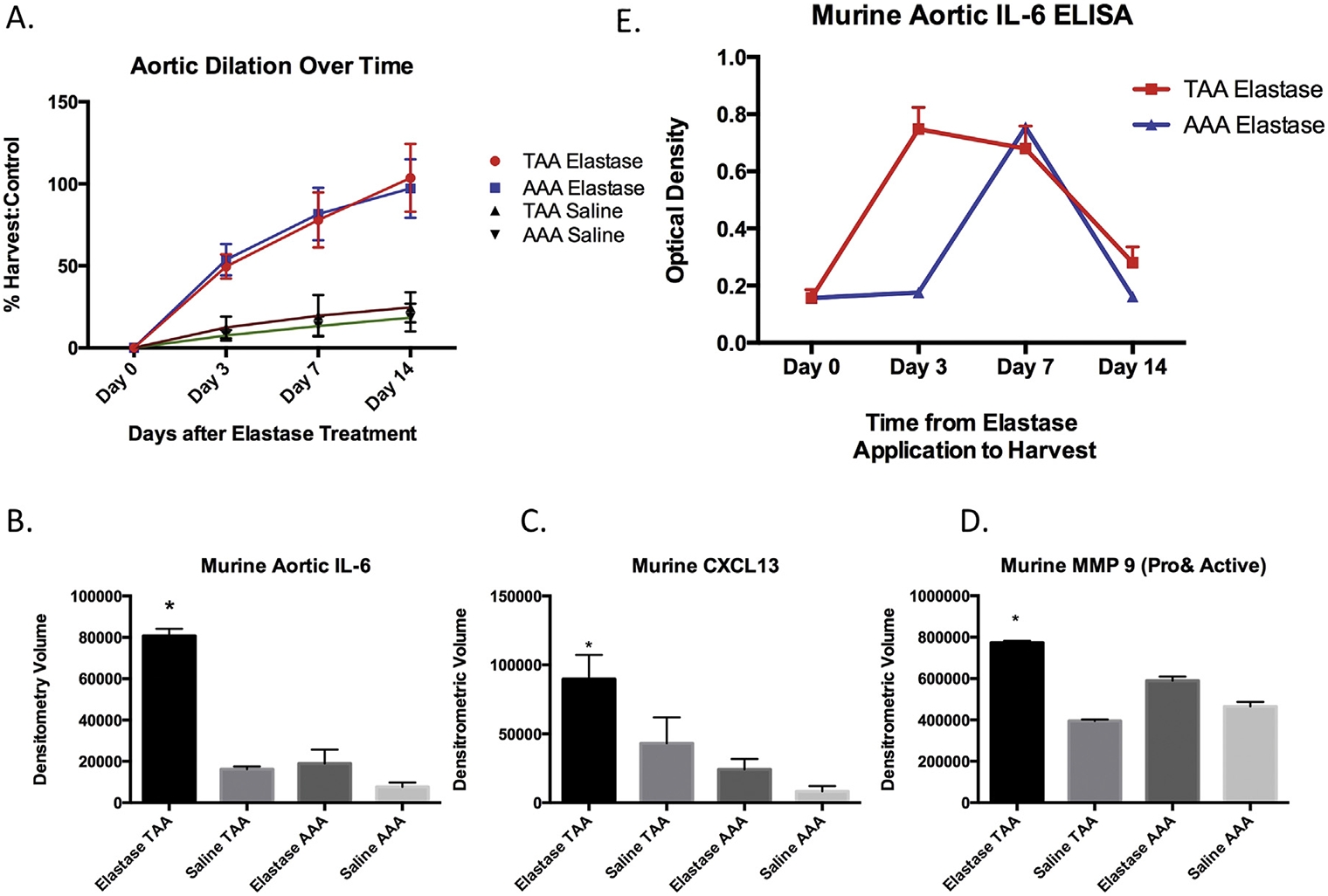

To assess differential cytokine expression in TAA and AAA, WT mice treated with elastase had thoracic and abdominal aneurysms of similar size at 3 days (n = 5 per group [49.6% versus 53.7%, p = 0.49]), 7 days (n = 5 per group [77.9% versus 81.6%, p = 0.74]), and 14 days (n = 5 per group [103.6% versus 97.1%, p = 0.64]) after treatment with elastase (Fig 1A). By cytokine array, IL-6 levels at day 7 were four times higher in TAA as compared with AAA (80,808 versus 18,936 optical density units, p = 0.0074) or saline controls at day 7 (thoracic 16,176, abdominal 7,692 optical density units, p = 0.0003; Fig 1B).

Fig 1.

(A) Aortic dilation days after topical treatment with elastase (n = 5 per group per timepoint). (Red line = thoracic aortic aneurysm [TAA] elastase; blue line = abdominal aortic aneurysm [AAA] elastase; black line = TAA saline; green line = AAA saline.) (B) Murine TAA interleukin-6 (IL-6) peaked higher and remained elevated longer than AAA, by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA [p < 0.0001]). (Red line = TAA elastase; blue line = AAA elastase.) Murine thoracic aortic (C) IL-6 (p = 0.0076), (D) CXCL-13 (p = 0.0028), and (E) matrix metalloprotease-9 (MMP-9 [p = 0.001]) were significantly elevated in elastase-treated mice as compared with saline-treated TAA and saline- or elastase-treated AAA.

Expression of more than 20 cytokines was assessed by antibody array. The TAA demonstrated significantly higher levels of CXCL13 (TAA 89,671, AAA 24,240 optical density units, p = 0.028) and matrix metalloproteinase (MMP)-9 (TAA 773,514, AAA 589,428, p = 0.001) compared with AAA (Fig 1C and D). In addition, IL-1β, IL-16, and tumor necrosis factor-α were more prevalent in AAA as compared with TAA (IL-1β TAA 244,179, AAA 271,720, p = 0.024; IL-16 TAA 248,850, AAA 327,456, p = 0.0002; tumor necrosis factor-α TAA 103,720, AAA 127,271, p = 0.0007). There was no significant difference between TAA and AAA for IL-1α (TAA 136,867, AAA 163,810, p = 0.06), IL-17 (TAA 35,553, AAA 63,584, p = 0.08), IL-23 (TAA 75,089, AAA 29,576, p = 0.20), or tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase-1 (TAA 501,290, AAA 529,759, p = 0.60). The IL-6 levels peaked at day 3 in TAA (74,756 optical density units) and at day 7 in AAA (7,549 optical density units; Fig 1E).

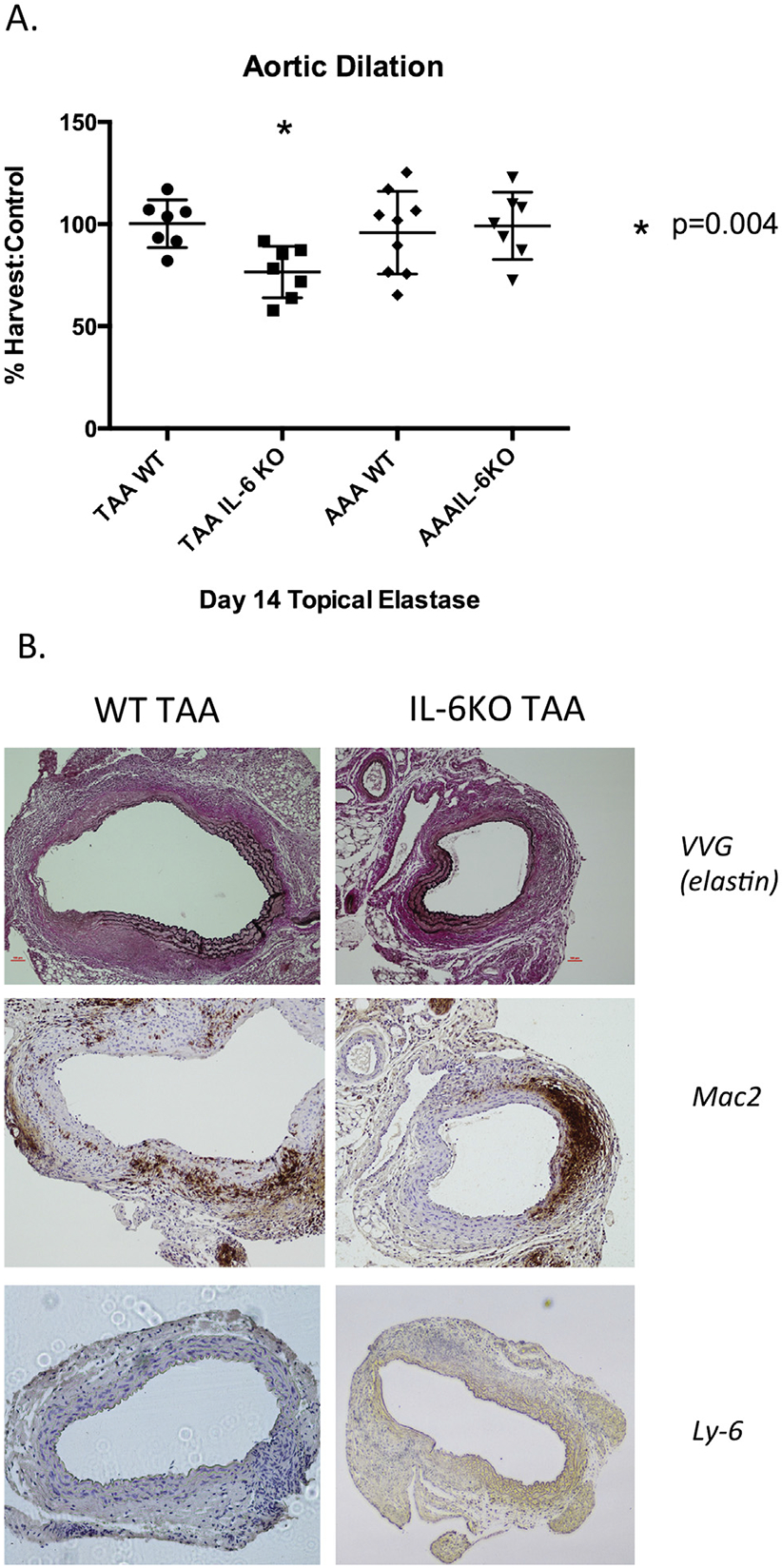

Interleukin-6KO Mice Are Protected From TAA, Not AAA

The IL-6KO mice (n = 7) treated with elastase were significantly smaller than WT mice control thoracic aorta treated with elastase (n — 7) at day 14 (WT 100.1% versus IL-6KO 76.5%, p = 0.0035). Interestingly, IL-6KO mice were not protected from AAA (n = 7) formation as compared with WT mice AAA controls (n = 9) at 14 days after elastase treatment (WT 95.8%, IL-6KO 99.1%, p = 0.73; Fig 2A). Histology demonstrated preservation of elastin fibers (Verhoeff-Van Gieson stain) in IL-6KO animals and without a notable difference in macrophage (Mac-2) or neutrophil (Ly-6) infiltrate (Fig 2B).

Fig 2.

(A) Aortic dilation in wild type (WT) mice (n = 7 per group) and interleukin-6 knockout (IL-6KO) mice (n = 7 per group) after thoracic aortic aneurysmal (TAA) or abdominal aortic aneurysmal (AAA) application of topical elastase. *p = 0.004. The IL-6KO mice had significantly smaller TAA compared with WT controls (WT 100.1% versus IL-6KO 76.5%, p = 0.0035). There was no significant difference between WT and IL-6KO AAA (WT 95.8%, IL-6KO 99.1, p = 0.73). (B) Left panels, WT TAA; right panels, IL-6KO TAA (original magnification). Elastin was preserved in IL-6KO animals without a significant difference in macrophage (Mac-2) or neutrophil (Ly-6) infiltration. (VVG = Verhoeff-Van Gieson stain.)

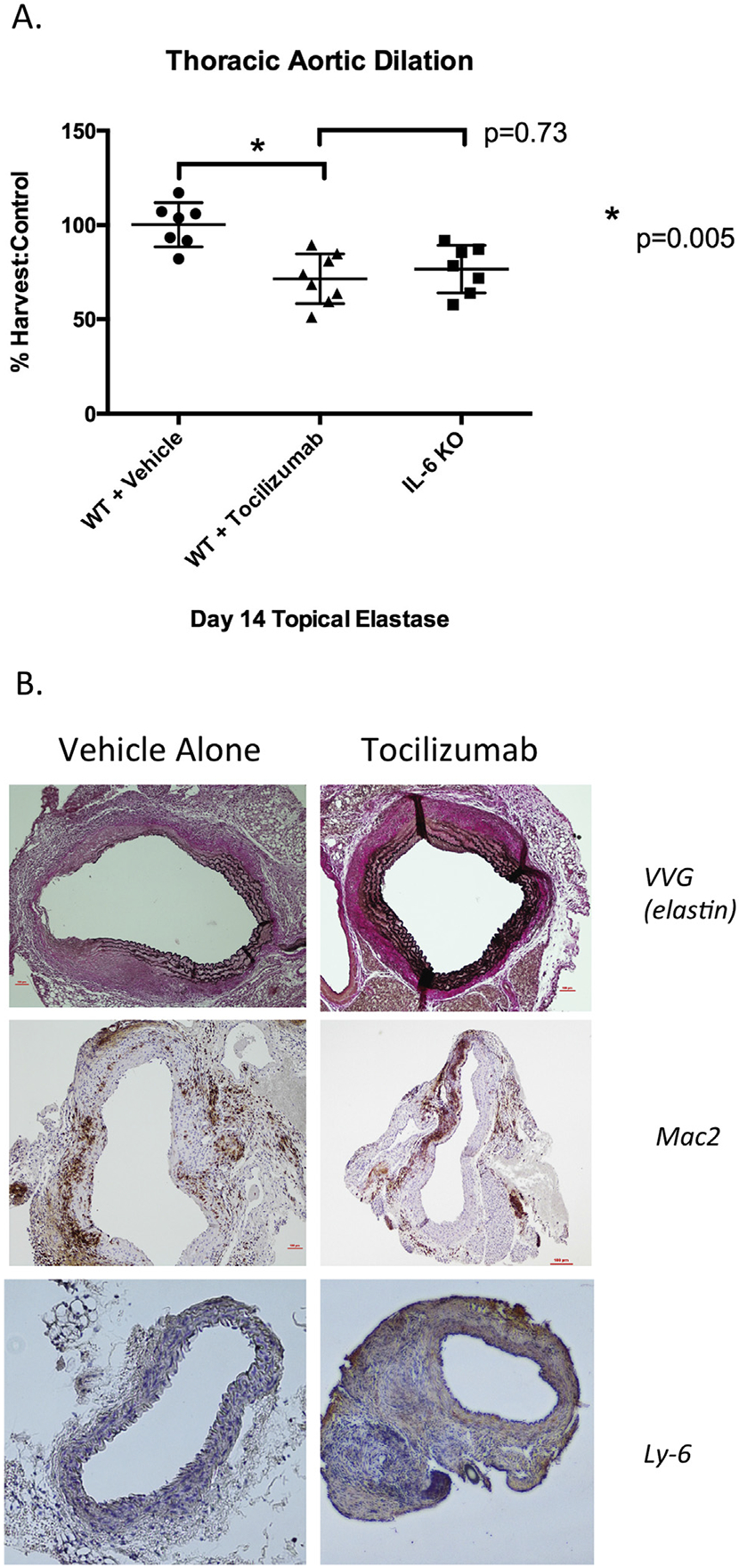

Pharmacologic Inhibition of IL-6 Inhibits Murine TAA

Pharmacologic inhibition of IL-6 signaling in WT TAA mice (WT treated with elastase to thoracic aorta) resulted in significant inhibition of TAA size in treated animals (tocilizumab 71.5% ± 13.2% versus vehicle 103.6% ± 20.7%, p = 0.005; Fig 3A). Histology demonstrated elastin preservation (Verhoeff-Van Gieson stain) in tocilizumabtreated mice without a notable difference in macrophage (Mac-2) or neutrophil (Ly-6) infiltrate (Fig 3B).

Fig 3.

(A) Treatment of wild type (WT) mice with interleukin-6 (IL-6) receptor antagonist (tocilizumab) by intraperitoneal injection before elastase treatment of the thoracic aorta. *p = 0.005. Tocilizumab treatment resulted in significant decrease in aneurysm size as compared with vehicle-treated controls (tocilizumab 71.5% ± 13.2% versus vehicle 103.6% ± 20.7%, p = 0.005). (KO = knock out.) (B) Left panels, vehicle alone; right panels, tocilizumab (original magnification). Tocilizumab treatment resulted in preservation of elastin fibers (Verhoeff-Van Gieson stain [VVG]) without change in macrophage (Mac-2) infiltration. (Ly-6 = neutrophil infiltration.)

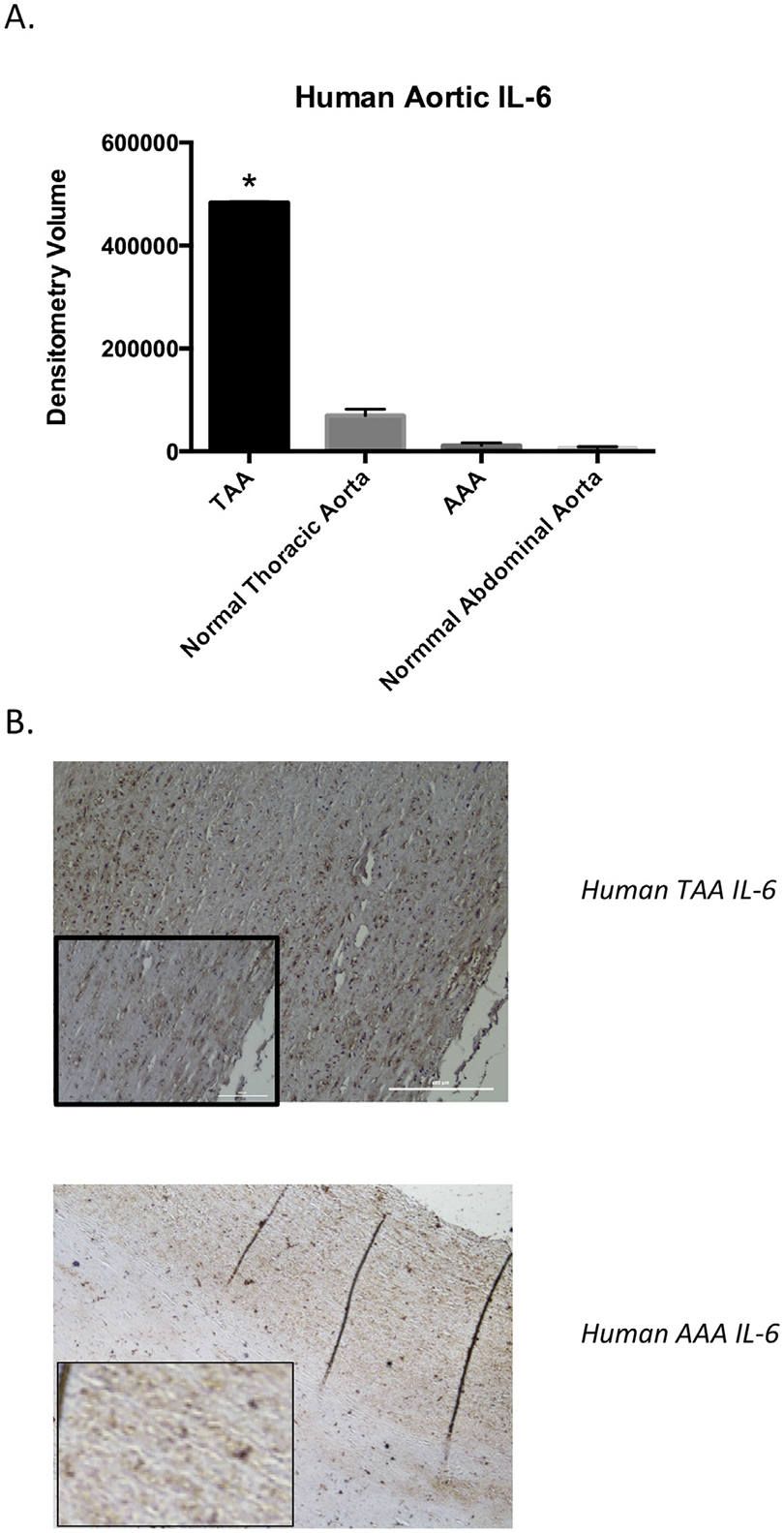

Human TAAs Demonstrate Significantly Higher IL-6 Expression

Human TAA samples also demonstrated significantly higher IL-6 expression than AAA samples (TAA 483,206, AAA 11,834 optical density units, p < 0.0001) or normal thoracic and abdominal samples (TA 69,654, AA 7,280 optical density units, p < 0.0001) by antibody array (Fig 4A). In addition, by immunohistochemistry, human TAAs have markedly greater IL-6 staining than human AAAs (Fig 4B).

Fig 4.

Human thoracic and abdominal aortic cytokine content in aneurysmal and nonaneurysmal samples. (A) Interleukin-6 (IL-6) is significantly higher in thoracic aortic aneurysmal (TAA) tissue (483,206 optical density units) as compared with abdominal aortic aneurysmal (AAA) tissue (11,834 optical density units; p < 0.0001). (B) Human tissue stained for IL-6: upper panel, TAA tissue; lower panel, AAA tissue (original magnification; insets show magnified views). The TAA tissue shows significantly denser IL-6 staining than the AAA tissue (n = 4 per group).

Comment

Herein, we demonstrate significantly higher murine IL-6 levels in TAA compared with AAA in response to similar types of injury and in similarly sized aneurysms. Although IL-6 was elevated in response to both TAA and AAA, aortic tissue expression of IL-6 was fourfold higher in TAA. Furthermore, IL-6 expression peaks significantly earlier in TAA and remains elevated longer than in AAA. Interestingly, mice deficient in IL-6 showed significant protection against TAA formation while having no protection from AAA, suggesting that this early and sustained IL-6 response is important in aneurysm formation, as evidenced by a 23% reduction in aneurysm size when IL-6 is not present.

Interleukin-6 has been shown to be an important marker in human AAA. Serum IL-6 has previously been shown to be elevated from baseline in patients with AAA and has been shown to correlate with aneurysm size [13, 14]. Moreover, polymorphisms in the IL-6 gene promoter have been shown to be an independent risk factor for AAA [17]. Although less well defined, IL-6 appears to be implicated in human TAA as well. Serum IL-6 and C-reactive protein to IL-6 ratios have been shown to correlate with TAA size [12]. Given the observational studies linking IL-6 to human aneurysmal disease, we believe that it represents an optimal target for potential disruption of the inflammatory cascade that leads to aortic aneurysm formation. To our knowledge, this study represents the first investigation into the role of IL-6 in TAA or AAA.

We demonstrated differential expression of cytokines in TAA and AAA. Specifically, murine TAA expressed higher levels of CXCL13 and MMP-9 at day 7. This enhanced inflammatory response could possibly be due to the increased density of smooth muscle cells in the thoracic compared with the abdominal aorta. Vascular smooth muscle cells are known to modulate to a secretory, inflammatory phenotype in response to injury, and may account for the exaggerated early inflammatory response demonstrated in TAA [18]. Interestingly, there was not an obvious decrease in macrophage recruitment in mice deficient in IL-6, perhaps because of an alteration in cellular function rather than recruitment, affecting the pathophysiology further downstream from inflammatory cell infiltration. Elucidating the exact mechanism by which IL-6 inhibition attenuates TAA formation was beyond the scope of this study, as IL-6 signal transduction remains only partially understood. In addition to classical IL-6 signal transduction through membrane-bound IL-6 receptor-α/gp130 complex and JAKS/STAT3, IL-6 is known to act through a soluble form of IL-6 receptor-α independent of gp130 in a process known as “transsignaling” [11, 19, 20]. Differing cell types have been shown to rely on transsignaling to varying degrees depending on local cellular conditions, and transsignaling has been shown to be important in recruiting the mononuclear cell inflammatory response [6, 11].

Importantly, tocilizumab (IL-6 receptor antagonist) treatment, in doses similar to those used for humans, demonstrated a comparable degree of aneurysm inhibition as genetic deletion of IL-6, suggesting this inhibitor results in strong inhibition of IL-6 signaling. In its current indication for use in rheumatoid arthritis, tocilizumab is generally well tolerated. The most common side effects reported in adults taking tocilizumab are upper respira-tory infections, nasopharyngitis, and headache [21].

The elevation in IL-6 demonstrated in murine TAAs was also demonstrated with human samples, with robust IL-6 staining in human TAA samples, indicating this important cytokine remains locally elevated even in the later phases of disease. Additional human subject trials are needed to further investigate the efficacy of pharmacologic IL-6 inhibition in preventing growth of small TAA.

Aneurysmal disease of the descending thoracic and abdominal aorta represents distinct disease processes. Although they are often thought of as the same disease process that takes place in differing locations, there are several important clinical, anatomic, and cellular differences that argue that they represent distinct processes. Morphologically, the expansion of TAA and AAA differ, as the posterior walls of TAA tend to be spared [22]. Although a AAA tends to expand uniformly in a fusiform fashion, the posterior portion of TAA tends not to dilate, as evidenced by a preserved distance between intercostal arteries posteriorly. On a cellular level, although both TAA and AAA exhibit elastin breakdown, TAA demonstrated greater MMP expression and smooth muscle cell loss. The thoracic and abdominal aortas arise from distinct embryologic cell lines and demonstrate differential responses to cytokine signals during embryogenesis [23, 24]. In addition, regional heterogeneity in MMP expression within the TAA wall may account for some of these differences, as cellular expression is not uniform throughout the human aorta [4]. Differences in mechanical forces, local cellular architecture, and differing smooth muscle composition may account for differences between the thoracic and abdominal aorta in response to injury.

Despite these novel findings, there are several limitations to note. The murine model of TAA is clearly artificial; however, the recapitulation of elevated IL-6 levels in human tissue samples would argue that our results may be translatable. Even so, comparison of IL-6 levels in individual patients with TAA or AAA remains difficult to interpret, likely because of genetic and functional variation in immune function. Our murine model allows for comparison of genetically similar subjects exposed to a consistent injury, thus increasing the validity of the comparison. Moreover, our experimental findings are limited to a single surgical model of descending TAA as no medical models of descending TAA have been reported. Finally, although we have demonstrated that treatment with tocilizumab given at the time of injury can attenuate TAA formation, we did not investigate treatment of an existing TAA in an attempt to prevent further dilation.

Future studies will focus on determining the mechanism by which IL-6 inhibition attenuates TAA formation by examining the specific roles of the membrane-bound and soluble IL-6 receptor. Translation to the clinical setting would require a randomized control trial of IL-6 receptor antagonist in patients with small descending TAA, as large animal translational models of TAA are lacking and existing IL-6 receptor antagonists have wellestablished safety profiles.

In conclusion, experimental murine TAA and AAA demonstrate distinct inflammatory responses during aneurysm formation with differential expression of a number of cytokines. Interlukin-6 plays a critical role in the formation of TAA but not AAA. Pharmacologic inhibition of IL-6 receptor recapitulates genetic deletion of IL-6 in the prevention of murine TAA. Significant IL-6 expression is also seen in human TAA. These data suggest that IL-6 may be considered a novel target for the treatment of thoracic aneurysmal disease.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to thank Anthony Herring, Cynthia Dodson, and Melissa Bevard for their knowledge and technical expertise. This work was supported by National Institutes of Health (NIH) KO8 HL098560 (to G.A) and RO1 HL081629 (to G.R.U.). This project was supported by National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) award T32HL007849 (to N.H.P; primary investigator, Irving L. Kron). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the views of the NHLBI.

Footnotes

Presented at the Poster Session of the Fifty-first Annual Meeting of The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, San Diego, CA, Jan 24–28, 2015.

References

- 1.Kuzmik GA, Sang AX, Elefteriades JA. Natural history of thoracic aortic aneurysms. J Vasc Surg 2012;56:565–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. National Center for Injury Prevention and Control. WISQARS leading causes of death reports. Atlanta, GA; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wassef M, Upchurch GR, Kuivaniemi H, Thompson RW, Tilson MD. Challenges and opportunities in abdominal aortic aneurysm research. J Vasc Surg 2007;45:192–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ailawadi G, Knipp BS, Lu G, et al. A nonintrinsic regional basis for increased infrarenal aortic mmp-9 expression and activity. J Vasc Surg 2003;37:1059–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Johnston WF, Salmon M, Pope NH, et al. Inhibition of interleukin-1beta decreases aneurysm formation and progression in a novel model of thoracic aortic aneurysms. Circulation 2014;130(Suppl 1):51–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rabe B, Chalaris A, May U, et al. Transgenic blockade of interleukin 6 transsignaling abrogates inflammation. Blood 2008;111:1021–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonser RS, Pagano D, Lewis ME, et al. Clinical and pathoanatomical factors affecting expansion of thoracic aortic aneurysms. Heart 2000;84:277–83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Boekholdt SM, Stroes ES. The interleukin-6 pathway and atherosclerosis. Lancet 2012;379:1176–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guzel S, Seven A, Kocaoglu A, et al. Osteoprotegerin, leptin and IL-6: association with silent myocardial ischemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Diabetes Vasc Dis Res 2013;10:25–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hirte HW. Novel developments in angiogenesis cancer therapy. Curr Oncol 2009;16:50–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hou T, Tieu BC, Ray S, et al. Roles of IL-6-GP130 signaling in vascular inflammation. Curr Cardiol Rev 2008;4:179–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Artemiou P, Charokopos N, Rouska E, et al. C-reactive protein/interleukin-6 ratio as marker of the size of the uncomplicated thoracic aortic aneurysms. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg 2012;15:871–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jones KG, Brull DJ, Brown LC, et al. Interleukin-6 (IL-6) and the prognosis of abdominal aortic aneurysms. Circulation 2001;103:2260–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rohde LE, Arroyo LH, Rifai N, et al. Plasma concentrations of interleukin-6 and abdominal aortic diameter among subjects without aortic dilatation. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol 1999;19:1695–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bhamidipati CM, Mehta GS, Lu G, et al. Development of a novel murine model of aortic aneurysms using periadventitial elastase. Surgery 2012;152:238–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salmon M, Johnston WF, Woo A, et al. Klf4 regulates abdominal aortic aneurysm morphology and deletion attenuates aneurysm formation. Circulation 2013;128(Suppl 1): 163–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Smallwood L, Allcock R, van Bockxmeer F, et al. Poly-morphisms of the interleukin-6 gene promoter and abdominal aortic aneurysm. Eur J Vasc Endovasc Surg 2008;35:31–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ailawadi G, Moehle CW, Pei H, et al. Smooth muscle phenotypic modulation is an early event in aortic aneurysms. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2009;138:1392–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Scheller J, Grötzinger J, Rose-John S. Updating interleukin-6 classic and trans-signaling. Signal Transduct 2006;6:240–59. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vardam TD, Zhou L, Appenheimer MM, et al. Regulation of a lymphocyte-endothelial-IL-6 trans-signaling axis by fever-range thermal stress: hot spot of immune surveillance. Cytokine 2007;39:84–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nishimoto N, Hashimoto J, Miyasaka N, et al. Study of active controlled monotherapy used for rheumatoid arthritis, an IL-6 inhibitor (samurai): evidence of clinical and radiographic benefit from an x-ray reader-blinded randomised controlled trial of tocilizumab. Ann Rheum Dis 2007;66:1162–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sinha I, Bethi S, Cronin P, et al. A biologic basis for asymmetric growth in descending thoracic aortic aneurysms: a role for matrix metalloproteinase 9 and 2. J Vasc Surg 2006;43: 342–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gadson PF, Dalton ML, Patterson E, et al. Differential response of mesoderm- and neural crest-derived smooth muscle to TGF-beta1: regulation of c-myb and alpha1 (I) procollagen genes. Exp Cell Res 1997;230:169–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ruddy JM, Jones JA, Spinale FG, Ikonomidis JS. Regional heterogeneity within the aorta: relevance to aneurysm disease. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2008;136:1123–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]