Abstract

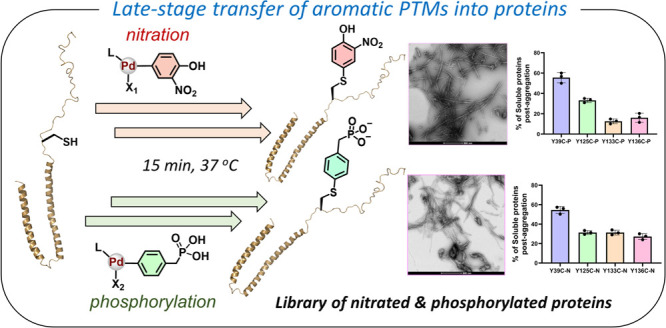

Posttranslational modifications (PTMs) of proteins play central roles in regulating the protein structure, interactome, and functions. A notable modification site is the aromatic side chain of Tyr, which undergoes modifications such as phosphorylation and nitration. Despite the biological and physiological importance of Tyr-PTMs, our current understanding of the mechanisms by which these modifications contribute to human health and disease remains incomplete. This knowledge gap arises from the absence of natural amino acids that can mimic these PTMs and the lack of synthetic tools for the site-specific introduction of aromatic PTMs into proteins. Herein, we describe a facile method for the site-specific chemical installation of aromatic PTMs into proteins through palladium-mediated S–C(sp2) bond formation under ambient conditions. We demonstrate the incorporation of novel PTMs such as Tyr-nitration and phosphorylation analogs to synthetic and recombinantly expressed Cys-containing peptides and proteins within minutes and in good yields. To demonstrate the versatility of our approach, we employed it to prepare 10 site-specifically modified proteins, including nitrated and phosphorylated analogs of Myc and Max proteins. Furthermore, we prepared a focused library of site-specifically nitrated and phosphorylated α–synuclein (α-Syn) protein, which enabled, for the first time, deciphering the role of these competing modifications in regulating α-Syn conformation aggregation in vitro. Our strategy offers advantages over synthetic or semisynthetic approaches, as it enables rapid and selective transfer of rarely explored aromatic PTMs into recombinant proteins, thus facilitating the generation of novel libraries of homogeneous posttranslationally modified proteins for biomarker discovery, mechanistic studies, and drug discovery.

Introduction

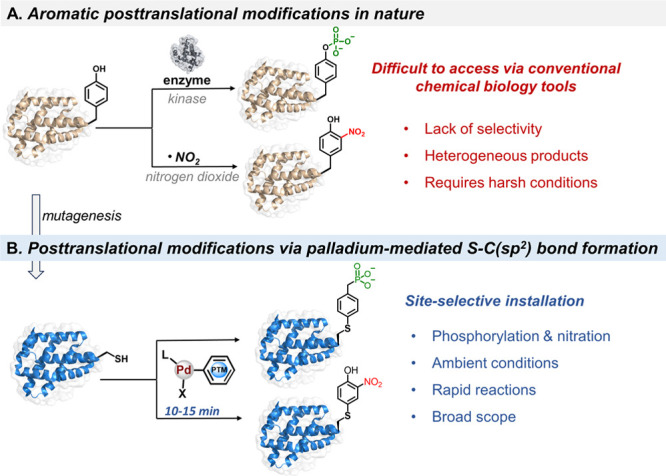

Posttranslational modifications (PTMs) of proteins play central roles in controlling numerous biological processes essential for the proper functionality of living cells.1 The incorporation of PTMs into proteins and their removal from proteins are a dynamic process that is tightly regulated by enzymes known as “writers” and “erasers”. The diverse nature of these modifications greatly contributes to expanding the structural and functional diversity of the proteome.2 Several amino acids in proteins are subjected to a wide range of PTMs, and different types of PTMs often compete for the same amino acid. Of particular interest are the tyrosine (Tyr) residues, which are known to undergo posttranslational modifications such as phosphorylation,3 sulfation,4 or nitration.5 Tyr-PTMs play important roles in regulating signal transduction, cell growth, differentiation, metabolism, regulation of enzymatic activity, and protein–protein interactions.6 Dysregulation of Tyr-PTMs is implicated in the development and progression of various human diseases including cancer and neurological disorders.3,6 However, dissecting the role of Tyr-PTMs in regulating the protein function in health and disease remains challenging and has been hampered by the lack of methodologies that allow for the site-specific introduction of Tyr modifications in vitro or investigating the dynamics of competing PTMs on Tyr residues in cells. Despite the significant advances in the chemical and semisynthetic strategies for producing homogeneously modified proteins, the incorporation of aromatic PTMs into proteins using common chemical biology tools remains largely limited and challenging,7 which has hampered efforts to decipher the PTM codes of proteins.8

Although it is widely accepted that phosphorylation at serine and threonine residues could be studied using amino acids that partially mimic the charge state of the phosphorylated forms of these residues, serine to aspartate or threonine to glutamate, there are no natural amino acids that can mimic aromatic PTMs. Furthermore, methods that allow ease and flexibility in the site-specific incorporation of these PTMs into proteins, especially natively structured proteins, in high homogeneity and workable quantities remain lacking. In vitro enzymatic modification methods often lack specificity, resulting in heterogeneous mixtures of modified proteins, which makes it difficult to decipher the relative contribution of Tyr modifications at specific residues or the cross-talk between specific residues. Furthermore, limited knowledge about the natural enzymes responsible for regulating Tyr modification presents additional challenges in deciphering their role in health and disease. Other biological approaches such as the genetic-code expansion method provide a powerful means to generate site-specifically modified proteins9; however, this method is technically challenging and is difficult to apply to produce proteins bearing multiple PTMs in sufficient quantities.10 Chemical protein synthesis and chemoselective protein ligation approaches represent powerful methods for addressing these limitations11 and have been successfully used to decipher the molecular role of PTMs of a large number of proteins of various sizes, along with functional and structural complexity.12 However, one of the limitations of these approaches is that introducing different modifications at the same residue often requires repeating the entire protein synthesis/semisynthesis, which is often time-consuming and challenging, especially when ligation reactions are carried out under denaturing conditions and proper refolding of the proteins is required.13 Therefore, there is a need to develop new and versatile methods that enable the rapid site-specific introduction of different types of PTMs, starting with properly folded proteins. We envisioned the development of late-stage and the orthogonal insertion of aromatic PTMs into native proteins to enable an unprecedented opportunity to generate libraries of homogeneously modified analogs. In principle, this process can enable rapid access to proteins bearing defined aromatic PTMs at the desired sites through direct protein diversification of recombinantly expressed proteins (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Palladium-mediated site-specific installation of aromatic PTM analogs into proteins. (A) Aromatic posttranslational modifications of proteins in nature, e.g., Tyr phosphorylation and nitration. (B) Site-specific late-stage installation of Tyr phosphorylation and nitration mimics into proteins.

Late-stage protein modification approaches are ideal to dissect the role of PTMs that compete for the same residue, e.g., Tyr phosphorylation and nitration.14 The low abundance and nucleophilicity of Cys residue have rendered it the site of choice to install site-specific modifications, labeling or aliphatic PTM mimics into proteins, mainly through S-alkylation and thiol-ene chemistry to provide the desired modified protein with a single atom (−S−) variation.15 Cys elimination to dehydroalanine (Dha) has also been explored to install aliphatic PTM mimics via Michael addition or carbon–carbon bond-forming reactions.16 The current late-stage protein modification approaches using Cys and Dha chemistry have provided unprecedented opportunities to modify proteins with specific PTMs. However, these strategies were implemented to incorporate primarily aliphatic PTM mimics such as Lys/Arg methylation, Lys acetylation, Ser phosphorylation, and glycosylation into proteins.15,16 Recently, Cys arylation has emerged as a powerful method for functionalizing biomolecules with high precision.17 In this context, S-arylation using transition metals is particularly noteworthy for its high reaction rate and chemoselectivity under ambient conditions.18 Herein, we report a facile and site-selective strategy to transfer aromatic PTM analogs to proteins through the Cys residue via palladium(II)-mediated S–C(sp2) bond formation reactions. We demonstrate the power of this approach to incorporate Tyr-nitration and phosphorylation at diverse sites and show that this approach could be used to produce homogeneously modified proteins in good yield and multimilligram quantities. Furthermore, this method enabled the preparation of a focused library of site-specifically nitrated or phosphorylated α-synuclein (α-Syn) analogs, enabling for the first time the investigation and comparison of the effect of these competing modifications with all Tyr residues in this protein, which plays a central role in the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease and other neurodegenerative disorders.19

Results and Discussion

Design of Palladium(II) Oxidative Addition Complexes to Install Aromatic PTMs to Unprotected Peptides

Organometallic palladium chemistry has emerged as a powerful means to functionalize a wide range of biopolymers with novel molecules.20 Of particular interest are palladium(II) oxidative addition complexes (Pd(II)OACs), which enable rapid and selective Cys functionalization in proteins through a C-S cross-coupling process.18a,21 We envisaged the design of Pd(II)OACs embedded with aromatic PTM scaffolds to allow the installation of target PTM mimics through Cys residues (Figure 2).22 Remarkably, the high reaction rate, selectivity, and aqueous compatibility of Pd(II)OACs,23 along with the orthogonal reactivity and low abundance of Cys, should in principle provide a powerful means to enable precise and rapid transfer of aromatic PTMs to unprotected peptides and proteins under aqueous conditions.

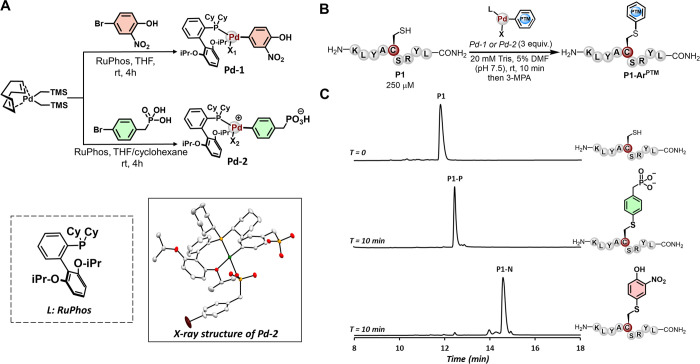

Figure 2.

Late-stage insertion of phosphorylation and nitration mimics to unprotected peptides using the palladium(II) strategy. (A) Schematic representation of the synthesis of palladium(II) oxidative addition complexes bearing aromatic PTMs and the X-ray structure of Pd-2 (CCDC: 2362585). (B) Schematic representation of the site-specific installation of phosphorylation and nitration mimics to unprotected peptides. (C) Analytical HPLC trace of the crude reactions after 10 min. The reactions were quenched with 3-mercaptopropionic acid (3-MPA) before HPLC analysis. Analytical RP-HPLC was performed by using 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid in water and acetonitrile as the mobile phases. Modified peptides were obtained in a protonated form. X1: bromide; X2: 4-bromobenzylphosphonic acid.

To test our hypothesis, we first set out to synthesize Pd(II)OAC bearing the 2-nitrophenol moiety to transfer the Tyr-nitration mimic (Figure 2A). By combining the bis[(trimethylsilyl)methyl](1,5-cyclooctadiene)palladium(II) [(COD)Pd(CH2TMS)2] precursor and 4-bromo-2-nitrophenol with RuPhos ligand, we were able to synthesize the desired Pd-1 complex, obtained in 88% isolated yield (see the Supporting Information, Section 2). To prepare the phosphorylation analog, we opted to develop a stable phospho-Tyr mimic with minimal alteration at the modification site (e.g., O-to-CH2 substitution). This approach should provide a hydrolysis-stable mimic that is compatible with both in vitro and in vivo studies. To this end, we reacted commercially available 4-bromobenzylphosphonic acid with [(COD)Pd(CH2TMS)2] in the presence of RuPhos, which provided the desired Pd-2 complex in 61% isolated yield (Figure 2A).

Both palladium complexes Pd-1 and Pd-2 exhibited superior reactivity, facilitating the effective transfer of nitration and phosphorylation analogs to Cys-containing peptides within minutes. Initially, we tested the reactivity of the Pd-1 and Pd-2 analogs with a 9-mer polypeptide (KLYACSRYL, P1), prepared using a standard Fmoc-SPPS (see the Supporting Information, Section 4.1). We were pleased to observe a rapid and effective incorporation of the aromatic PTM analogs to P1 using a low loading of Pd-1 and Pd-2 (3 equiv) in 20 mM Tris buffer (pH 7.5) using 5% DMF cosolvent. This led to a quantitative conversion to the desired site-specifically modified products within less than 10 min at room temperature, as determined by analytical high-performance liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (HPLC–MS) analysis (Figure 2B,C). These findings indicate that designed Pd(II)OACs could effectively insert aromatic PTM mimics into unprotected peptides under mild conditions, highlighting the power of this strategy to transfer aromatic PTMs to complex biomacromolecules.

Palladium(II)-Mediated Site-Selective Installation of Phosphorylation and Nitration Analogs into Proteins

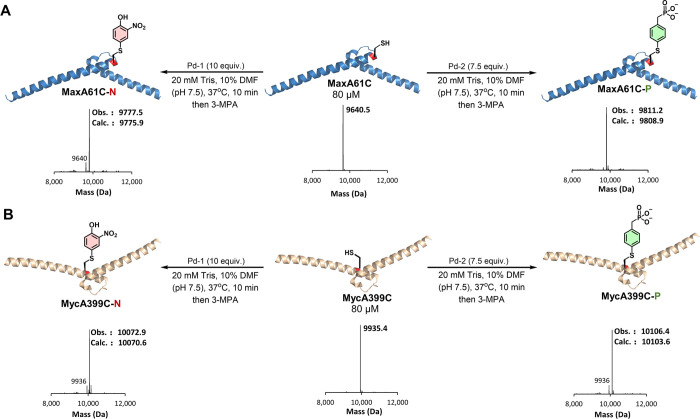

Encouraged by our results, we turned our attention to site-selectively incorporating the phosphorylation and nitration marks into protein at predetermined sites. As a model system, we employed our approach to modify the DNA binding domains of the Myc and Max transcription factors (TFs) engineered with a single Cys residue (MaxA61C and MycA399C). We initially reacted MaxA61C with Pd-1 or Pd-2 separately using the optimized reaction conditions in 20 mM Tris buffer and 10% DMF (pH 7.5) at 37 °C (see the Supporting Information, Section 7). These conditions provided the mononitrated and phosphorylated products MaxA61C-N and MaxA61C-P within 10 min in 86 and 96% conversion, respectively, as determined by LC-MS analysis (Figure 3A). We observed the same outcome once we reacted the MycA399C protein with Pd-1 or Pd-2 under the optimized conditions, which provided the desired modified products MycA399C-N and MycA399C-P in 85 and 89% conversion, respectively (Figure 3B). These transformations establish that Tyr-nitration and phosphorylation could be successfully transferred to target proteins through palladium-mediated C-S arylation to provide site-selectively modified proteins. In principle, this late-stage process could enable rapid and effective protein diversification with aromatic PTMs to generate novel libraries of homogeneous posttranslationally modified proteins to dissect their code.

Figure 3.

Site-specific installation of phosphorylation and nitration PTM analogs into proteins via palladium-mediated S–C(sp2) bond formation. (A) Monophosphorylated and nitrated MaxA61C protein. The deconvoluted mass spectrum of the starting material and the crude reaction mixtures after 10 min is depicted. (B) Monophosphorylated and nitrated of MycA399C protein. The deconvoluted mass spectrum of the starting material and the crude reaction mixtures after 10 min is depicted. LCMS was performed using 0.1% formic acid in water and acetonitrile as the mobile phases. Modified proteins were obtained in the protonated form.

Next, we probed the chemical stability of the nitration and phosphorylation mimics. The PTM analogs in our approach are coupled to proteins through S–C(sp2) linkage, which should provide high chemical stability.18a To this end, using MaxA61C protein, we produced both modified analogs and analyzed their stability in aqueous buffer (see the Supporting Information, Sections 8.3 and 8.4). We reacted 6.0 mg of MaxA61C with Pd-2 in 20 mM Tris buffer and 5% DMF (pH 7.5) at 37 °C, which provided the desired site-specifically phosphorylated product MaxA61C-P. Subsequently, we purified the modified proteins with preparative RP-HPLC to provide MaxA61C-P in 65% isolated yield (see the Supporting Information, Section 8.1). Similarly, we successfully isolated the nitrated product MaxA61C-N in 64% isolated yield after RP-HPLC purification (see the Supporting Information, Section 8.2). Having both isolated analogs, we incubated MaxA61C-N and MaxA61C-P separately in phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) at 37 °C. LCMS analysis revealed that no degradation had occurred after 5 days (see the Supporting Information, Sections 8.3 and 8.4). Taken together, these experiments revealed that the installation of phosphorylation and nitration Tyr modifications could be performed on a milligram scale and could provide homogeneously modified proteins in good yield through a stable S-aryl linkage, thus enabling more detailed structural, biochemical, and biological studies to decipher the role of these modifications.

Site-Specific Incorporation of Nitration and Phosphorylation Analogs into α-Syn Protein

To further assess the effectiveness of our nitro and phosphomimetics in reproducing the effects of bona fide PTMs, we used the synaptic protein α-Syn as a model system, since it offers several advantages: (1) phosphorylation and nitration in several α-Syn Tyr residues have been implicated in pathology formation and neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease (PD) and other neurological diseases characterized by α-Syn aggregation and pathology formation,24 (2) α-Syn sequences consist of a limited number of Tyr residues, thus allowing the assessment of differential effects of mimicking phosphorylation/nitration at different Tyr residues, and (3) previous studies have already investigated the effect of site-specific phosphorylation/nitration at multiple α-Syn Tyr residues using protein semisynthetic approaches, thus allowing for a direct comparison of our results to data from bona fide modified forms of the protein.

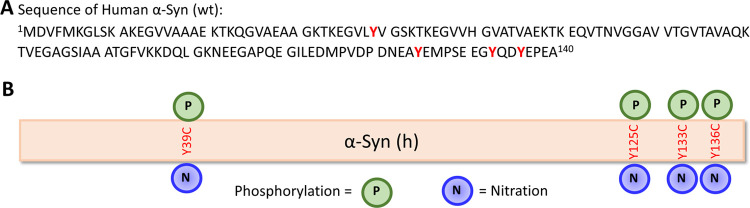

α-Syn is a highly soluble, acidic protein expressed in the neurons of the central and peripheral nervous system25; it belongs to the family of intrinsically disordered proteins.26 The aggregation and fibrillogenesis of α-Syn in the brain are the defining features of PD and other synucleinopathies.27 Currently, α-Syn is one of the most sought targets for developing diagnostic and therapeutic strategies; moreover, increasing evidence indicates that PTMs are key regulators of its pathogenic properties.28 Human α-Syn has four Tyr residues: one is in the N-terminal region at position 39 and the other three are in the C-terminal region at positions 125, 133, and 136 (Figure 4A). Each of these residues is susceptible to competing PTMs such as phosphorylation and nitration (Figure 4B). In particular, phosphorylation at Tyr-39, Tyr-125, Tyr-133, and Tyr-136 has been detected in postmortem brain tissues from patients with PD and other neurodegenerative diseases.29 Similarly, nitration of Tyr residues is one of the key features of pathological aggregates found in PD brains.30 Moreover, the accumulation of 3-nitrotyrosine and cross-linked dityrosine α-Syn aggregates has been detected in the brains of patients with PD, dementia with LBs (DLBs), and multiple system atrophy (MSA).31 Finally, the link between oxidative and nitrative stress, as well as α-Syn aggregation and pathology formation in synucleinopathies, is also supported by a 9-fold increase in α-Syn nitration at Tyr-39 upon the overexpression of monoamine oxidase B in animal models of PD.32 Altogether, these findings underscore the critical importance of deciphering the role of these Tyr modifications in regulating α-Syn aggregation and pathology formation.

Figure 4.

(A) Amino acid sequence of the wild-type (wt) α-Syn (h): the four Tyr residues are highlighted in red. (B) Schematic representation of the α-Syn phosphorylation and nitration at Tyr → Cys mutation points.

Initially, we sought to determine whether mutating Tyr to Cys (Y → C) at 39, 125, 133, or 136 influences the ability of α-Syn to aggregate and form fibrils. All four α-Syn variants (α-SynY39C, α-SynY125C, α-SynY133C, and α-SynY136C) and WT α-Syn were expressed and purified as described previously.33 The purity of the proteins was verified by UPLC-MS (Supporting Information, Figures S23–S26) and SDS-PAGE analyses (Supporting Information, Figure S27). To investigate how a single Y → C mutation at different positions (Tyr-39/125/133/136) affects the conformation of α-Syn monomers, we compared the circular dichroism (CD) spectra of purified WT α-Syn and Cys-mutated α-Syn from Escherichia coli. WT-α-Syn and the four Cys mutants displayed indistinguishable CD spectra, with a minimum at ∼198 nm, which is consistent with a predominantly disordered conformation (Supporting Information, Figure S28A). Next, we investigated the effect of these mutations on the aggregation properties of α-Syn using the well-established thioflavin T (ThT)-based fluorescence assay under the standard conditions used to induce α-Syn aggregates into β-sheet-rich fibrils (incubation of monomeric α-Syn in sterile PBS buffer, pH ∼ 7 at 37 °C with vigorous shaking for 5 days), which are ThT-positive.34 The aggregation of all Cys mutants was monitored using the ThT fibrillization assay along with WT-α-Syn as a positive control at a 20 μM concentration. All four C → Y variants formed predominantly fibrillar structures that were very similar in morphology, length, and width to WT-α-Syn (Supporting Information, Figure S29C–G). Analysis of the kinetic curves from three independent experiments revealed that the α-SynY125C, α-SynY133C, and α-SynY136C mutants exhibited slightly faster aggregation compared with WT-α-Syn and α-SynY39C (Supporting Information, Figure S29A). After 5 days of incubation, nearly all four proteins (>80–90%) converted to insoluble fibrils, as determined using the sedimentation assay,33 i.e., by quantifying the remaining soluble α-Syn species at the end of the aggregation on day 5 (Supporting Information, Figure S29B). The Cys mutants exhibited similar (α-SynY39C) or slightly lower (α-SynY125C, α-SynY133C, and α-SynY136C) percentages of soluble proteins post aggregation (Supporting Information, Figure S29B), despite the differences in ThT intensity at the steady state between α-SynY39C and the other Y → C mutants. These observations indicate that the Y → C mutations do not markedly change the extent of α-Syn fibrillization or alter the morphology of the final fibrillar structures.

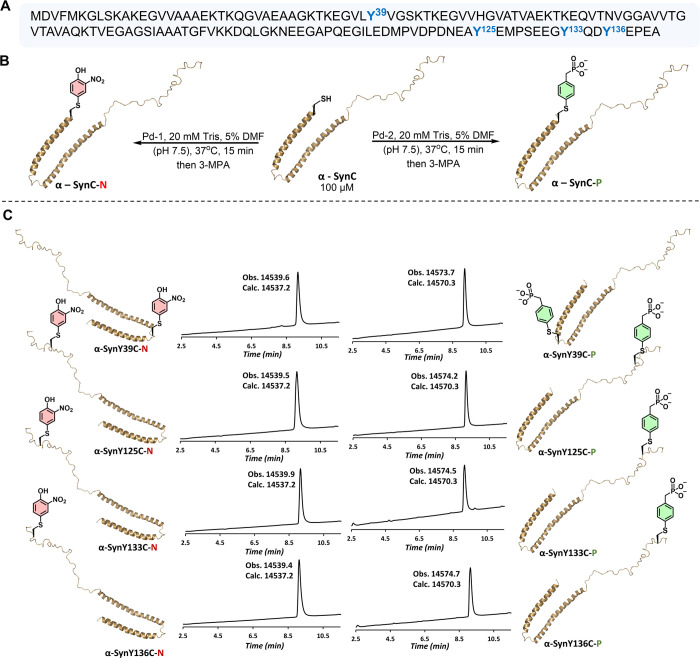

Next, we used the same approach described above to produce homogeneously phosphorylated or nitrated α-Syn with high fidelity. We initially treated α-SynY39C with Pd-2 using our optimized reaction conditions in 20 mM Tris buffer and 5% DMF (pH 7.5) at 37 °C for 15 min. This provided the desired monophosphorylated product α-SynY39C-P in 73% isolated yield after RP-HPLC purification (see the Supporting Information, Section 9.1). Reacting the other analogs α-SynY125C, α-SynY133C, and α-SynY136C separately with Pd-2 under the same reaction conditions afforded the desired monophosphorylated products α-SynY125C-P, α-SynY133C-P, and α-SynY136C-P in 83, 79, and 77% isolated yields, respectively. The identity and purity of all phosphorylated analogs were confirmed by LCMS (Figure 5), SDS-PAGE analysis (Supporting Information, Figure S27), and 31P NMR (Supporting Information, Figures S43–S46). Subsequently, we reacted the α-SynY39C, α-SynY125C, α-SynY133C, and α-SynY136C analogs separately with Pd-1, which provided the desired mononitrated products α-SynY39C-N, α-SynY125C-N, α-SynY133C-N, and α-SynY136C-N in 43, 45, 55, and 30% isolated yields, respectively (see the Supporting Information, Section 9.2). The identity and purity of the nitrated analogs were confirmed by LCMS (Figure 5) and SDS-PAGE analysis (Supporting Information, Figure S27). Remarkably, this approach enabled the facile insertion of the nitration and phosphorylation analogs at all possible nitration and phosphorylation sites on a milligram scale (Figure 5). Notably, previous reports have demonstrated the potential of semisynthetic strategies to prepare nitrated and phosphorylated α-Syn at Tyr-39 and Tyr-125 residues.35 These proteins were isolated in moderate to good yields due to the multistep operation, which required multiple synthetic and isolation steps. On the other hand, the preparation of nitrated and phosphorylated α-Syn at Tyr-133 and Tyr-136 has never been reported. Importantly, our late-stage approach provided the nitrated and phosphorylated α-Syn analogs at all Tyr sites in a single-step operation in good yields. Such success in building a focused library of site-specifically nitrated and phosphorylated α-Syn analogs further reinforces the power of the palladium-mediated late-stage arylation for the rapid production of homogeneous PTM-modified recombinant proteins in high quality and good quantities.

Figure 5.

Site-specific incorporation of phosphorylation and nitration analogs to α-Syn protein. (A) Sequence of α-Syn; highlighted Tyr phosphorylation and nitration sites. (B) Schematic representation of the production of nitrated and phosphorylated α-Syn analogs. (C) LCMS chromatograms and the deconvoluted mass spectra of the isolated modified α-Syn analogs. LCMS was performed using 0.1% formic acid in water and acetonitrile as the mobile phases. Modified proteins were obtained in the protonated form.

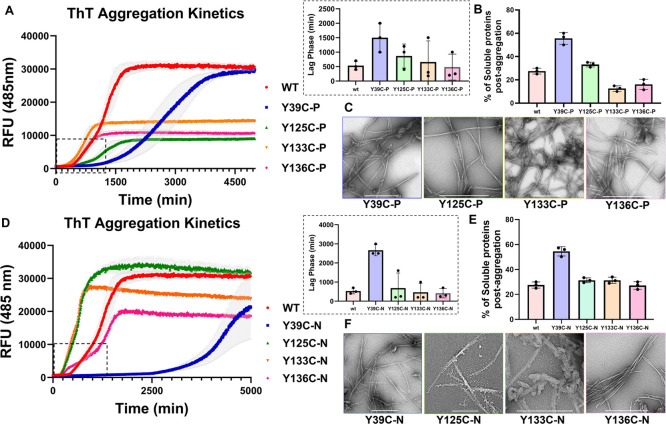

Phosphorylation at Residue 39 or 125 Significantly Inhibits α-Syn Aggregation In Vitro

All phosphorylated α-Syn proteins showed CD spectra similar to that of WT α-Syn (Supporting Information, Figure S28B). A comparison of the aggregation profile of all the phosphorylated analogs shows that α-SynY133C-P and α-SynY136C-P exhibited a lag time similar to the WT α-Syn protein but showed a noticeable reduction in ThT intensity at the steady state (Figure 6A). Interestingly, α-SynY125C-P and α-SynY39C-P proteins aggregated slower than did the WT α-Syn protein, along with a longer lag phase and a reduction in aggregation observed for α-SynY39C-P (Figure 6B). The trend of the lag phase for these phosphorylated analogs is α-SynY39C-P > α-SynY125C-P > WT α-Syn ∼ α-SynY136C-P ∼ α-SynY133C-P. Interestingly, the ThT intensity of the α-SynY125C-P, α-SynY136C-P, and α-SynY133C-P proteins at the steady state was significantly lower than that of WT α-Syn or α-SynY39C-P. We hypothesized that this could be due to the presence of reduced levels of fibrils or the formation of fibrils that exhibit reduced affinity for ThT.36 To more accurately assess the extent of fibrillization, we quantified the amounts of the remaining monomers after 5 days using the sedimentation assay (Supporting Information, Figure S31F–I). Interestingly, we observed complete fibrillization for all α-SynY125C-P, α-SynY133C-P, and α-SynY136C-P proteins. However, the percentage of soluble protein for α-SynY39C-P was higher than those for the remaining proteins. These results suggest that lower plateau values for α-SynY125C-P, α-SynY133C-P, and α-SynY136C-P analogs could be attributed to a reduction in the ThT binding site due to differences in the fibril structure or the lateral association of the phosphorylated fibrils. Consistent with this hypothesis, the fibrils formed by the phosphorylated analogs appeared morphologically wider (Figure 6C), 2–3-fold wider than the WT α-Syn protein (Supporting Information, Figure S33).

Figure 6.

(A) Aggregation kinetics of phosphorylated α-Syn based on thioflavin T fluorescence (ThT ± SEM; n = 3). The difference in the lag phase is shown in the bottom box. (B) Corresponding quantification of the remaining soluble protein ± SEM of WT α-Syn, α-SynY39C-P, α-SynY125C-P, α-SynY133C-P, and α-SynY136C-P. (C) Electron micrographs of phosphorylated proteins (the scale bars are 500 nm). (D) Aggregation kinetics of nitrated α-Syn based on thioflavin T fluorescence (ThT ± SEM, n = 3). (E) Corresponding quantification of the remaining soluble protein ± SEM of WT α-Syn, α-SynY39C-N, α-SynY125C-N, α-SynY133C-N, and α-SynY136C-N. (F) Electron micrographs of nitrated proteins (the scale bars are 500 nm). For expanded EM micrographs, please see the Supporting Information, Section 17.

Our results on the marked reduction in the aggregation propensity of α-SynY39C-P are consistent with previous observations using semisynthetic pY39-α-Syn.35a Interestingly, the delayed aggregation kinetics of α-SynY125C-P differ from the previously reported semisynthetic α-SynY125, where phosphorylation at this site was shown not to significantly influence the conformation or the aggregation kinetics of α-Syn.35d Importantly, our work represents the first study on the effect of the site-specific phosphorylation of α-Syn at Tyr-133 and Tyr-136 (α-SynY133C-P and α-SynY136C-P) on the aggregation kinetics and properties of α-Syn. We showed that phosphorylation at these residues does not influence the aggregation kinetics of the protein but results in the formation of morphologically wider fibrils compared with those of WT α-Syn.

N-Terminal but Not C-Terminal Nitration Inhibits the Aggregation of α-Syn In Vitro

Next, we investigated the effect of nitration on the conformation and in vitro fibrillization of α-Syn. Nitration at all Tyr residues did not induce any changes in the CD spectra of α-Syn (Supporting Information, Figure S28C). Similar to what we observed with phosphorylation, only nitration at Tyr-39 resulted in a significant delay in the aggregation of α-Syn, whereas nitration at the C-terminal Tyr residues resulted in either similar (Tyr-125) or slightly faster aggregation (Tyr-133 and Tyr-136) (Figure 6D). Even after 5 days of aggregation, the percentage of the remaining soluble protein in the case of α-SynY39C-N is higher than those of the remaining nitrated proteins (α-SynY125C-N, α-SynY133C-N, and α-SynY136C-N) (Figure 6E). Next, we evaluated the structural properties of the aggregates formed after 5 days by TEM. Interestingly, the nitrated analogs of α-Syn form fibrils with distinct morphologies compared with their native Tyr-nitrated analogs (Figure 6F). α-SynY39C-N and α-SynY125C-N both formed shorter fibrils after longer aggregation times.35e As previously reported, both native nY39-α-Syn and nY125-α-Syn formed predominantly short and thick fibrils, particularly with nY39-α-Syn. The nY125-α-Syn aggregates exhibited a high propensity to stack in parallel.35e In contrast, both α-SynY39C-N and α-SynY125C-N showed elongated fibrils similar to WT α-Syn or their modified analogs (Figure 6F). Although our results on the α-SynY39C-N analog are consistent with the previous finding from our group, demonstrating a strong aggregation inhibitory effect of nitration at this position,35e the results on α-SynY125C-N show a different trend than the previously reported results, where we observed increased aggregation kinetics for nY125-α-Syn (Figure 6D).35e

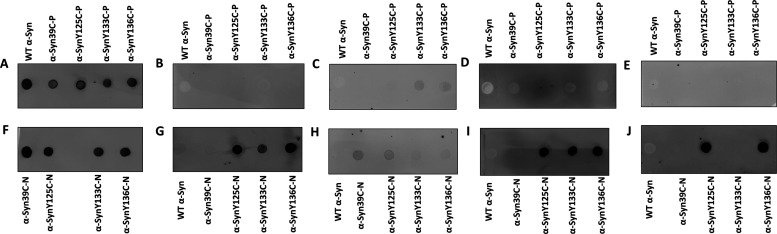

α-Syn fibrils produced in vitro are commonly used to induce the aggregation and inclusion formation of endogenous α-Syn proteins in cellular and animal models of α-Syn pathology formation. Recent studies from the Lashuel Laboratory and others have also employed posttranslationally modified α-Syn fibrils to dissect the role of PTMs in regulating α-Syn aggregation and pathogenicity. The internalization and fate of these modified fibrils are monitored primarily by using PTM-specific antibodies. Therefore, to determine whether our phospho- and nitromimetics could be detected by antibodies that recognize the bona fide phosphorylated and nitrated α-Syn, we performed dot-blot analysis using commercially available antibodies specific to 39/125/133/136 native phosphorylated or nitrated α-Syn(h).29a As shown in Figure 7, the nitrated proteins were recognized by the corresponding antibodies (Figure 7G–J and Figure S12). In contrast, the phosphorylated analogs were not recognized by the phospho-antibodies (Figure 7B–E and Figure S11). We believe that this behavior can be attributed to the substitution of the oxygen atom in the phosphorylation by methylene. Although these findings preclude the use of pS129 antibodies to track the modified fibrils prepared using the phospho- and nitromimetics, they present an opportunity to address one of the major challenges faced by the community today, which is how to distinguish between exogenous modified fibrils and newly formed fibrils in cells with the same modifications. Therefore, the phosphorylated proteins that we produced here represent important tools that enable selective monitoring, evolution, and clearance of only newly seeded fibrils in the cells. Importantly, the fact that all the antibodies against nitrated α-Syn recognized the nitrated α-Syn analogs supports the conclusion that the nitration method described here could serve as a general method to study Tyr-nitration and could provide a rapid and efficient method for generating modified α-Syn protein standards and tools for biomarker discovery and validation.

Figure 7.

Dot-blot analysis of the nitrated and phosphorylated α-Syn(h) analogs against (A, F) anti-α-Syn(H) antibody (epitope: Syn 91-99), (B) anti-Syn-pY39, (C) anti-Syn-pY125, (D) anti-Syn-pY133, (E) anti-Syn-pY133, Syn-pY136, (G) anti-Nitrated-Syn, (H) anti-Syn-nY39, (I) anti-Syn-nY125, nY133, and (J) anti-Syn-nY125, nY136.

One of the limitations of our approach is the introduction of single-atom alteration and insertion of the (−S−) atom at the desired PTM site. Although previous Cys alkylation methods used to install aliphatic modifications (e.g., methylation) through thioether linkage have shown that such an alteration is a reasonable mimic of native PTMs,15 systematic studies on the impact of such alterations have not been performed. Our work on α-Syn presents the first opportunity for such a comparison since the corresponding site-specifically modified bona fide phosphorylated and nitrated forms of this protein at Tyr-39 and Tyr-125 have been produced and characterized.35d,37 Our data show that both bona fide phosphorylated and nitrated proteins at Tyr-39 exhibited similar aggregation properties, whereas different results were observed on α-Syn aggregation kinetics when these modifications were introduced at the C-terminus of the protein. These observations could be explained by the fact that Tyr-39 occurs within a more hydrophobic domain of the α-Syn sequence and is part of the structured amyloid core of the fibrils,38 whereas Tyr-125 occurs in a highly negatively charged and disordered domain that lies outside the amyloid core and is sensitive to pH and interactions with different types of ions and metals.

Conclusions

The site-specific installation of aromatic PTMs into recombinant protein provides a versatile approach to produce homogeneous analogs with novel aromatic PTMs, e.g., in Tyr residue. We developed a rapid and effective strategy that enables the site-selective installation of essential aromatic PTMs into native peptides and proteins containing an engineered Cys site that directs site-specific installation. The reaction proceeds within minutes through a palladium(II)-mediated S–C(sp2) bond formation process under ambient conditions. We demonstrated that this strategy could be used to insert novel PTMs such as nitration and phosphorylation mimics into several protein targets in high quality and good yields, including the Myc and Max TFs and α-Syn on a multimilligram scale. The ability to produce a spectrum of site-specifically modified α-Syn analogs (at Tyr-39, Tyr-125, Tyr-133, and Tyr-136) enabled for the first time the investigation and comparison of the effect of nitration and phosphorylation on all Tyr residues in modulating α-Syn aggregation properties in vitro. Furthermore, this is the first study to investigate the effect of competing site-specific nitration or phosphorylation at Tyr-133 and Tyr-136. Importantly, this strategy leverages the power of organometallic palladium chemistry to functionalize proteins with aromatic PTMs. Recently, elegant strategies involving novel organometallic gold reagents and activated pyridinium salts have been reported for rapid Cys arylation, with enhanced reaction rates (104 to 105 M–1 s–1).18d,18e These approaches are envisioned to further expand the scope of accessible aromatic transformations to functionalize complex biomolecules for various applications.

The ability to introduce late-stage, postfolding, or postaggregation PTMs, along with the efficiency of the reactions and good yields, is envisioned to pave the way for future studies to explore the rarely explored role of aromatic PTM sites and their cross-talk with other PTMs in regulating the function, dysfunction, or pathogenicity of proteins, for example, investigating the effect of postfibrillization site-specific nitration or phosphorylation of α-Syn and its impact on α-Syn fibril uptake, processing, seeding activity, and pathological spreading in the brain and peripheral tissues. Finally, this method could be further extended to transfer other native and non-native aromatic PTMs, e.g., Tyr-sulfonation, for various biochemical and biomedical studies. This and other research programs are currently under investigation in our laboratories.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by the ISF Grant 493/23, the Neubauer Foundation, and the Council for Higher Education (M.J.) and EPFL (H.L.A. and S.M.). We thank the Protein Production and Structure Core Facility for the expression and purification of the α-Syn wt and mutant proteins used in this study (B.B.) and the Interdisciplinary Centre for Electron Microscopy for providing access to the electron microscopes. Additionally, we thank the Jbara group members for their assistance with peptide synthesis and Dr. Sophia Lipstman for the X-ray structure analysis.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/jacs.4c08416.

Synthesis and methods, as well as biochemical and biophysical characterization of all compounds (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Walsh C. T.; Garneau-Tsodikova S.; Gatto G. J. Jr. Protein posttranslational modifications: the chemistry of proteome diversifications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44 (45), 7342–7372. 10.1002/anie.200501023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barber K. W.; Rinehart J. The ABCs of PTMs. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2018, 14 (3), 188–192. 10.1038/nchembio.2572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter T. The Genesis of Tyrosine Phosphorylation. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2014, 6 (5), a020644 10.1101/cshperspect.a020644. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell J. W. C.; Payne R. J. Revealing the functional roles of tyrosine sulfation using synthetic sulfopeptides and sulfoproteins. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 2020, 58, 72–85. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2020.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sabadashka M.; Nagalievska M.; Sybirna N. Tyrosine nitration as a key event of signal transduction that regulates functional state of the cell. Cell Biol. Int. 2021, 45 (3), 481–497. 10.1002/cbin.11301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Q.; Xiao X.; Qiu Y.; Xu Z.; Chen C.; Chong B.; Zhao X.; Hai S.; Li S.; An Z.; et al. Protein posttranslational modifications in health and diseases: Functions, regulatory mechanisms, and therapeutic implications. Medcomm 2023, 4 (3), e261 10.1002/mco2.261. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Spicer C. D.; Davis B. G. Selective chemical protein modification. Nat. Commun. 2014, 5, 4740. 10.1038/ncomms5740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Krall N.; da Cruz F. P.; Boutureira O.; Bernardes G. J. Site-selective protein-modification chemistry for basic biology and drug development. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8 (2), 103–113. 10.1038/nchem.2393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Bondalapati S.; Jbara M.; Brik A. Expanding the chemical toolbox for the synthesis of large and uniquely modified proteins. Nat. Chem. 2016, 8 (5), 407–418. 10.1038/nchem.2476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Harel O.; Jbara M. Chemical Synthesis of Bioactive Proteins. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, 62 (13), e202217716 10.1002/anie.202217716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Wang Z. A.; Cole P. A. Methods and Applications of Expressed Protein Ligation. Methods Mol. Biol. 2020, 2133, 1–13. 10.1007/978-1-0716-0434-2_1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Neumann H.; Hazen J. L.; Weinstein J.; Mehl R. A.; Chin J. W. Genetically encoding protein oxidative damage. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2008, 130 (12), 4028–4033. 10.1021/ja710100d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Chin J. W. Expanding and reprogramming the genetic code. Nature 2017, 550 (7674), 53–60. 10.1038/nature24031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Hoppmann C.; Wong A.; Yang B.; Li S. W.; Hunter T.; Shokat K. M.; Wang L. Site-specific incorporation of phosphotyrosine using an expanded genetic code. Nat Chem Biol 2017, 13 (8), 842. 10.1038/nchembio.2406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Lang K.; Chin J. W. Cellular incorporation of unnatural amino acids and bioorthogonal labeling of proteins. Chem. Rev. 2014, 114 (9), 4764–4806. 10.1021/cr400355w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Xie J. M.; Schultz P. G. Innovation: A chemical toolkit for proteins - an expanded genetic code. Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio 2006, 7 (10), 775–782. 10.1038/nrm2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Kent S. Chemical protein synthesis: Inventing synthetic methods to decipher how proteins work. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25 (18), 4926–4937. 10.1016/j.bmc.2017.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Hackenberger C. P.; Schwarzer D. Chemoselective ligation and modification strategies for peptides and proteins. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2008, 47 (52), 10030–10074. 10.1002/anie.200801313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Pattabiraman V. R.; Bode J. W. Rethinking amide bond synthesis. Nature 2011, 480 (7378), 471–479. 10.1038/nature10702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Piemontese E.; Herfort A.; Perevedentseva Y.; Moller H. M.; Seitz O. Multiphosphorylation-Dependent Recognition of Anti-pS2 Antibodies against RNA Polymerase II C-Terminal Domain Revealed by Chemical Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146 (17), 12074–12086. 10.1021/jacs.4c01902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jbara M.; Maity S. K.; Morgan M.; Wolberger C.; Brik A. Chemical Synthesis of Phosphorylated Histone H2A at Tyr57 Reveals Insight into the Inhibition Mode of the SAGA Deubiquitinating Module. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55 (16), 4972–4976. 10.1002/anie.201600638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Li Y.; Heng J.; Sun D.; Zhang B.; Zhang X.; Zheng Y.; Shi W. W.; Wang T. Y.; Li J. Y.; Sun X.; et al. Chemical Synthesis of a Full-Length G-Protein-Coupled Receptor beta2-Adrenergic Receptor with Defined Modification Patterns at the C-Terminus. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (42), 17566–17576. 10.1021/jacs.1c07369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; From NLM Medline.; d Premdjee B.; Andersen A. S.; Larance M.; Conde-Frieboes K. W.; Payne R. J. Chemical Synthesis of Phosphorylated Insulin-like Growth Factor Binding Protein 2. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (14), 5336–5342. 10.1021/jacs.1c02280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Haj-Yahya M.; Gopinath P.; Rajasekhar K.; Mirbaha H.; Diamond M. I.; Lashuel H. A. Site-Specific Hyperphosphorylation Inhibits, Rather than Promotes, Tau Fibrillization, Seeding Capacity, and Its Microtubule Binding. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2020, 59 (10), 4059–4067. 10.1002/anie.201913001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Nithun R. V.; Yao Y. M.; Lin X.; Habiballah S.; Afek A.; Jbara M. Deciphering the Role of the Ser-Phosphorylation Pattern on the DNA-Binding Activity of Max Transcription Factor Using Chemical Protein Synthesis. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2023, e202310913 10.1002/anie.202310913. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; g McGinty R. K.; Kim J.; Chatterjee C.; Roeder R. G.; Muir T. W. Chemically ubiquitylated histone H2B stimulates hDot1L-mediated intranucleosomal methylation. Nature 2008, 453 (7196), 812–U812. 10.1038/nature06906. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; h Murar C. E.; Ninomiya M.; Shimura S.; Karakus U.; Boyman O.; Bode J. W. Chemical Synthesis of Interleukin-2 and Disulfide Stabilizing Analogues. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (22), 8425–8429. 10.1002/anie.201916053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; i Li H. X.; Zhang J.; An C. J.; Dong S. W. Probing N-Glycan Functions in Human Interleukin-17A Based on Chemically Synthesized Homogeneous Glycoforms. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (7), 2846–2856. 10.1021/jacs.0c12448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; j Wang P.; Dong S. W.; Shieh J. H.; Peguero E.; Hendrickson R.; Moore M. A. S.; Danishefsky S. J. Erythropoietin Derived by Chemical Synthesis. Science 2013, 342 (6164), 1357–1360. 10.1126/science.1245095. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; k Ellmer D.; Brehs M.; Haj-Yahya M.; Lashuel H. A.; Becker C. F. W. Single Posttranslational Modifications in the Central Repeat Domains of Tau4 Impact its Aggregation and Tubulin Binding. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58 (6), 1616–1620. 10.1002/anie.201805238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; l Hessefort H.; Gross A.; Seeleithner S.; Hessefort M.; Kirsch T.; Perkams L.; Bundgaard K. O.; Gottwald K.; Rau D.; Graf C. G. F.; et al. Chemical and Enzymatic Synthesis of Sialylated Glycoforms of Human Erythropoietin. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2021, 60 (49), 25922–25932. 10.1002/anie.202110013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; m Maki Y.; Okamoto R.; Izumi M.; Kajihara Y. Chemical Synthesis of an Erythropoietin Glycoform Having a Triantennary N-Glycan: Significant Change of Biological Activity of Glycoprotein by Addition of a Small Molecular Weight Trisaccharide. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (49), 20671–20679. 10.1021/jacs.0c08719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; n Pomplun S.; Jbara M.; Schissel C. K.; Wilson Hawken S.; Boija A.; Li C.; Klein I.; Pentelute B. L. Parallel Automated Flow Synthesis of Covalent Protein Complexes That Can Inhibit MYC-Driven Transcription. ACS Cent. Sci. 2021, 7 (8), 1408–1418. 10.1021/acscentsci.1c00663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; o Wu H. X.; Zhang Y. W.; Li Y. X.; Xu J. C.; Wang Y.; Li X. C. Chemical Synthesis and Biological Evaluations of Adiponectin Collagenous Domain Glycoforms (vol 143, pg 7808, 2021). J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (25), 9695–9695. 10.1021/jacs.1c05501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; p Nithun R. V.; Yao Y. M.; Harel O.; Habiballah S.; Afek A.; Jbara M. Site-Specific Acetylation of the Transcription Factor Protein Max Modulates Its DNA Binding Activity. ACS Cent. Sci. 2024, 10 (6), 1295–1303. 10.1021/acscentsci.4c00686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Holt M.; Muir T. Application of the protein semisynthesis strategy to the generation of modified chromatin. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 2015, 84, 265–290. 10.1146/annurev-biochem-060614-034429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Maity S. K.; Jbara M.; Brik A. Chemical and semisynthesis of modified histones. J Pept Sci 2016, 22 (5), 252–259. 10.1002/psc.2848. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Kulkarni S. S.; Sayers J.; Premdjee B.; Payne R. J. Rapid and efficient protein synthesis through expansion of the native chemical ligation concept. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2018, 2 (4), 0122 10.1038/s41570-018-0122. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; d Tan Y.; Wu H. X.; Wei T. Y.; Li X. C. Chemical Protein Synthesis: Advances, Challenges, and Outlooks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2020, 142 (48), 20288–20298. 10.1021/jacs.0c09664. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Wright T. H.; Vallee M. R.; Davis B. G. From Chemical Mutagenesis to Post-Expression Mutagenesis: A 50 Year Odyssey. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2016, 55 (20), 5896–5903. 10.1002/anie.201509310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; From NLM Medline.; b Wright T. H.; Bower B. J.; Chalker J. M.; Bernardes G. J. L.; Wiewiora R.; Ng W. L.; Raj R.; Faulkner S.; Vallée M. R.; Phanumartwiwath A.; et al. Posttranslational mutagenesis: A chemical strategy for exploring protein side-chain diversity. Science 2016, 354 (6312), aag1465 10.1126/science.aag1465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Yang A.; Ha S.; Ahn J.; Kim R.; Kim S.; Lee Y.; Kim J.; Soll D.; Lee H. Y.; Park H. S. A chemical biology route to site-specific authentic protein modifications. Science 2016, 354 (6312), 623–626. 10.1126/science.aah4428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Dadova J.; Galan S. R.; Davis B. G. Synthesis of modified proteins via functionalization of dehydroalanine. Curr Opin Chem Biol 2018, 46, 71–81. 10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Harel O.; Jbara M. Posttranslational Chemical Mutagenesis Methods to Insert Posttranslational Modifications into Recombinant Proteins. Molecules 2022, 27 (14), 4389. 10.3390/molecules27144389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Chalker J. M.; Lercher L.; Rose N. R.; Schofield C. J.; Davis B. G. Conversion of cysteine into dehydroalanine enables access to synthetic histones bearing diverse post-translational modifications. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2012, 51 (8), 1835–1839. 10.1002/anie.201106432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Josephson B.; Fehl C.; Isenegger P. G.; Nadal S.; Wright T. H.; Poh A. W. J.; Bower B. J.; Giltrap A. M.; Chen L.; Batchelor-McAuley C.; et al. Light-driven post-translational installation of reactive protein side chains. Nature 2020, 585 (7826), 530–537. 10.1038/s41586-020-2733-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Zhang C.; Vinogradova E. V.; Spokoyny A. M.; Buchwald S. L.; Pentelute B. L. Arylation Chemistry for Bioconjugation. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2019, 58 (15), 4810–4839. 10.1002/anie.201806009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jbara M. Transition metal catalyzed site-selective cysteine diversification of proteins. Pure Appl. Chem. 2021, 93 (2), 169–186. 10.1515/pac-2020-0504. [DOI] [Google Scholar]; c Montgomery H. R.; Spokoyny A. M.; Maynard H. D. Organometallic Oxidative Addition Complexes for S-Arylation of Free Cysteines. Bioconjug. Chem. 2024, 35 (7), 883–889. 10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.4c00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Vinogradova E. V.; Zhang C.; Spokoyny A. M.; Pentelute B. L.; Buchwald S. L. Organometallic palladium reagents for cysteine bioconjugation. Nature 2015, 526 (7575), 687–691. 10.1038/nature15739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Messina M. S.; Stauber J. M.; Waddington M. A.; Rheingold A. L.; Maynard H. D.; Spokoyny A. M. Organometallic Gold(III) Reagents for Cysteine Arylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140 (23), 7065–7069. 10.1021/jacs.8b04115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Willwacher J.; Raj R.; Mohammed S.; Davis B. G. Selective Metal-Site-Guided Arylation of Proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2016, 138 (28), 8678–8681. 10.1021/jacs.6b04043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Lipka B. M.; Honeycutt D. S.; Bassett G. M.; Kowal T. N.; Adamczyk M.; Cartnick Z. C.; Betti V. M.; Goldberg J. M.; Wang F. Ultra-rapid Electrophilic Cysteine Arylation. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2023, 145 (43), 23427–23432. 10.1021/jacs.3c10334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Doud E. A.; Tilden J. A. R.; Treacy J. W.; Chao E. Y.; Montgomery H. R.; Kunkel G. E.; Olivares E. J.; Adhami N.; Kerr T. A.; Chen Y.; et al. Ultrafast Au(III)-Mediated Arylation of Cysteine. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146 (18), 12365–12374. 10.1021/jacs.3c12170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f Hanaya K.; Ohata J.; Miller M. K.; Mangubat-Medina A. E.; Swierczynski M. J.; Yang D. C.; Rosenthal R. M.; Popp B. V.; Ball Z. T. Rapid nickel(ii)-promoted cysteine S-arylation with arylboronic acids. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55 (19), 2841–2844. 10.1039/C9CC00159J. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashuel H. A.; Overk C. R.; Oueslati A.; Masliah E. The many faces of alpha-synuclein: from structure and toxicity to therapeutic target. Nat Rev Neurosci 2013, 14 (1), 38–48. 10.1038/nrn3406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Jbara M.; Maity S. K.; Brik A. Palladium in the Chemical Synthesis and Modification of Proteins. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (36), 10644–10655. 10.1002/anie.201702370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Isenegger P. G.; Davis B. G. Concepts of Catalysis in Site-Selective Protein Modifications. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2019, 141 (20), 8005–8013. 10.1021/jacs.8b13187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ingoglia B. T.; Buchwald S. L. Oxidative Addition Complexes as Precatalysts for Cross-Coupling Reactions Requiring Extremely Bulky Biarylphosphine Ligands. Org. Lett. 2017, 19 (11), 2853–2856. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b01082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin X. X.; Nithun R. V.; Samanta R.; Harel O.; Jbara M. Enabling Peptide Ligation at Aromatic Junction Mimics via Native Chemical Ligation and Palladium-Mediated S-Arylation. Org. Lett. 2023, 25 (25), 4715–4719. 10.1021/acs.orglett.3c01652. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Jbara M.; Pomplun S.; Schissel C. K.; Hawken S. W.; Boija A.; Klein I.; Rodriguez J.; Buchwald S. L.; Pentelute B. L. Engineering Bioactive Dimeric Transcription Factor Analogs via Palladium Rebound Reagents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2021, 143 (30), 11788–11798. 10.1021/jacs.1c05666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Jbara M.; Rodriguez J.; Dhanjee H. H.; Loas A.; Buchwald S. L.; Pentelute B. L. Oligonucleotide Bioconjugation with Bifunctional Palladium Reagents. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. Engl. 2021, 60 (21), 12109–12115. 10.1002/anie.202103180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Lin X.; Harel O.; Jbara M. Chemical Engineering of Artificial Transcription Factors by Orthogonal Palladium(II)-Mediated S-Arylation Reactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2024, 63, e202317511 10.1002/anie.202317511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magalhães P.; Lashuel H. A. Opportunities and challenges of alpha-synuclein as a potential biomarker for Parkinson’s disease and other synucleinopathies. NPJ Parkinsons Dis. 2022, 8 (1), 93. 10.1038/s41531-022-00357-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Burré J. The Synaptic Function of α-Synuclein. J Parkinson Dis 2015, 5 (4), 699–713. 10.3233/JPD-150642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Iwai A.; Masliah E.; Yoshimoto M.; Ge N. F.; Flanagan L.; Desilva H. A. R.; Kittel A.; Saitoh T. The Precursor Protein of Non-Aβ Component of Alzheimers Disease Amyloid Is a Presynaptic Protein of the Central Nervous System. Neuron 1995, 14 (2), 467–475. 10.1016/0896-6273(95)90302-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Eliezer D.; Kutluay E.; Bussell R.; Browne G. Conformational properties of α-synuclein in its free and lipid-associated states. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 307 (4), 1061–1073. 10.1006/jmbi.2001.4538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Weinreb P. H.; Zhen W. G.; Poon A. W.; Conway K. A.; Lansbury P. T. NACP, a protein implicated in Alzheimer’s disease and learning, is natively unfolded. Biochemistry 1996, 35 (43), 13709–13715. 10.1021/bi961799n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spillantini M. G.; Goedert M. The α-synucleinopathies:: Parkinson’s disease, dementia with Lewy bodies, and multiple system atrophy. Ann Ny Acad Sci 2000, 920, 16–27. 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2000.tb06900.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Levine P. M.; Galesic A.; Balana A. T.; Mahul-Mellier A. L.; Navarro M. X.; De Leon C. A.; Lashuel H. A.; Pratt M. R. alpha-Synuclein O-GlcNAcylation alters aggregation and toxicity, revealing certain residues as potential inhibitors of Parkinson’s disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2019, 116 (5), 1511–1519. 10.1073/pnas.1808845116. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Balana A. T.; Mahul-Mellier A. L.; Nguyen B. A.; Horvath M.; Javed A.; Hard E. R.; Jasiqi Y.; Singh P.; Afrin S.; Pedretti R.; et al. O-GlcNAc forces an alpha-synuclein amyloid strain with notably diminished seeding and pathology. Nat Chem Biol 2024, 20 (5), 646–655. 10.1038/s41589-024-01551-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Mahul-Mellier A. L.; Burtscher J.; Maharjan N.; Weerens L.; Croisier M.; Kuttler F.; Leleu M.; Knott G. W.; Lashuel H. A. The process of Lewy body formation, rather than simply alpha-synuclein fibrillization, is one of the major drivers of neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2020, 117 (9), 4971–4982. 10.1073/pnas.1913904117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Pan B.; Shimogawa M.; Zhao J.; Rhoades E.; Kashina A.; Petersson E. J. Cysteine-Based Mimic of Arginylation Reproduces Neuroprotective Effects of the Authentic Post-Translational Modification on alpha-Synuclein. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2022, 144 (17), 7911–7918. 10.1021/jacs.2c02499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Pan B.; Petersson E. J. A PARP-1 Feed-Forward Mechanism To Accelerate alpha-Synuclein Toxicity in Parkinson’s Disease. Biochemistry 2019, 58 (7), 859–860. 10.1021/acs.biochem.8b01311. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Altay M. F.; Kumar S. T.; Burtscher J.; Jagannath S.; Strand C.; Miki Y.; Parkkinen L.; Holton J. L.; Lashuel H. A. Development and validation of an expanded antibody toolset that captures alpha-synuclein pathological diversity in Lewy body diseases. NPJ Parkinson's Dis. 2023, 9 (1), 161. 10.1038/s41531-023-00604-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Mahul-Mellier A. L.; Fauvet B.; Gysbers A.; Dikiy I.; Oueslati A.; Georgeon S.; Lamontanara A. J.; Bisquertt A.; Eliezer D.; Masliah E.; et al. c-Abl phosphorylates α-synuclein and regulates its degradation: implication for α-synuclein clearance and contribution to the pathogenesis of Parkinson’s disease. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23 (11), 2858–2879. 10.1093/hmg/ddt674. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duda J. E.; Giasson B. I.; Chen Q. P.; Gur T. L.; Hurtig H. I.; Stern M. B.; Gollomp S. M.; Ischiropoulos H.; Lee V. M. Y.; Trojanowski J. Q. Widespread nitration of pathological inclusions in neurodegenerative synucleinopathies. Am. J. Pathol. 2000, 157 (5), 1439–1445. 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)64781-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Souza J. M.; Giasson B. I.; Chen Q. P.; Lee V. M. Y.; Ischiropoulos H. Dityrosine cross-linking promotes formation of stable α-synuclein polymers -: Implication of nitrative and oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative synucleinopathies. J. Biol. Chem. 2000, 275 (24), 18344–18349. 10.1074/jbc.M000206200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b He Y. X.; Yu Z. W.; Chen S. D. Alpha-Synuclein Nitration and Its Implications in Parkinson’s Disease. Acs Chemical Neuroscience 2019, 10 (2), 777. 10.1021/acschemneuro.8b00288. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Altay M. F.; Liu A. K. L.; Holton J. L.; Parkkinen L.; Lashuel H. A. Prominent astrocytic alpha-synuclein pathology with unique post-translational modification signatures unveiled across Lewy body disorders. Acta Neuropathol. Comun. 2022, 10 (1), 163. 10.1186/s40478-022-01468-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Gómez-Tortosa E.; Gonzalo I.; Newell K.; Yébenes J.; Vonsattel P.; Hyman B. T. Patterns of protein nitration in dementia with Lewy bodies and striatonigral degeneration. Acta Neuropathol 2002, 103 (5), 495–500. 10.1007/s00401-001-0495-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Lyras L.; Perry R. H.; Perry E. K.; Ince P. G.; Jenner A.; Jenner P.; Halliwell B. Oxidative damage to proteins, lipids, and DNA in cortical brain regions from patients with dementia with Lewy bodies. J Neurochem 1998, 71 (1), 302–312. 10.1046/j.1471-4159.1998.71010302.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Danielson S. R.; Held J. M.; Schilling B.; Oo M.; Gibson B. W.; Andersen J. K. Preferentially Increased Nitration of α-Synuclein at Tyrosine-39 in a Cellular Oxidative Model of Parkinson’s Disease. Anal. Chem. 2009, 81 (18), 7823–7828. 10.1021/ac901176t. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar S. T.; Donzelli S.; Chiki A.; Syed M. M. K.; Lashuel H. A. A simple, versatile and robust centrifugation-based filtration protocol for the isolation and quantification of α-synuclein monomers, oligomers and fibrils: Towards improving experimental reproducibility in α-synuclein research. J Neurochem 2020, 153 (1), 103–119. 10.1111/jnc.14955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naiki H.; Higuchi K.; Hosokawa M.; Takeda T. Fluorometric determination of amyloid fibrils in vitro using the fluorescent dye, thioflavin T1. Anal. Biochem. 1989, 177 (2), 244–249. 10.1016/0003-2697(89)90046-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a Dikiy I.; Fauvet B.; Jovicic A.; Mahul-Mellier A. L.; Desobry C.; El-Turk F.; Gitler A. D.; Lashuel H. A.; Eliezer D. Semisynthetic and in Vitro Phosphorylation of Alpha-Synuclein at Y39 Promotes Functional Partly Helical Membrane-Bound States Resembling Those Induced by PD Mutations. ACS Chem. Biol. 2016, 11 (9), 2428–2437. 10.1021/acschembio.6b00539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Pan B.; Rhoades E.; Petersson E. J. Chemoenzymatic Semisynthesis of Phosphorylated alpha-Synuclein Enables Identification of a Bidirectional Effect on Fibril Formation. ACS Chem. Biol. 2020, 15 (3), 640–645. 10.1021/acschembio.9b01038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; c Zhao K.; Lim Y. J.; Liu Z.; Long H.; Sun Y.; Hu J. J.; Zhao C.; Tao Y.; Zhang X.; Li D.; et al. Parkinson’s disease-related phosphorylation at Tyr39 rearranges alpha-synuclein amyloid fibril structure revealed by cryo-EM.. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U S A 2020, 117 (33), 20305–20315. 10.1073/pnas.1922741117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; d Hejjaoui M.; Butterfield S.; Fauvet B.; Vercruysse F.; Cui J.; Dikiy I.; Prudent M.; Olschewski D.; Zhang Y.; Eliezer D.; et al. Elucidating the Role of C-Terminal Post-Translational Modifications Using Protein Semisynthesis Strategies: α-Synuclein Phosphorylation at Tyrosine 125. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012, 134 (11), 5196–5210. 10.1021/ja210866j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; e Burai R.; Ait-Bouziad N.; Chiki A.; Lashuel H. A. Elucidating the Role of Site-Specific Nitration of α-Synuclein in the Pathogenesis of Parkinson’s Disease via Protein Semisynthesis and Mutagenesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137 (15), 5041–5052. 10.1021/ja5131726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- a De Giorgi F.; Laferrière F.; Zinghirino F.; Faggiani E.; Lends A.; Bertoni M.; Yu X.. et al. Emergence of stealth polymorphs that escape α-synuclein amyloid monitoring, take over and acutely spread in neurons. bioRxiv, 2020, doi: 10.1101/2020.02.11.943670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; b Sokratian A.; Ye Z.; Meltem T.; Kevin J. B.; Enquan X.; Elizabeth V.; Addison M. D.. et al. Mouse α-synuclein fibrils are structurally and functionally distinct from human fibrils associated with Lewy body diseases. bioRxiv. 2024, doi: 10.1101/2024.05.09.593334. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dikiy I.; Fauvet B.; Jovicic A.; Mahul-Mellier A. L.; Desobry C.; El-Turk F.; Gitler A. D.; Lashuel H. A.; Eliezer D. Semisynthetic and Phosphorylation of lpha-Synuclein at Y39 Promotes Functional Partly Helical Membrane-Bound States Resembling Those Induced by PD Mutations. ACS Chem. Bio. 2016, 11 (9), 2428–2437. 10.1021/acschembio.6b00539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dhavale D. D.; Barclay A. M.; Borcik C. G.; Basore K.; Berthold D. A.; Gordon I. R.; Liu J.; Milchberg M. H.; O’Shea J. Y.; Rau M. J.; et al. Structure of alpha-synuclein fibrils derived from human Lewy body dementia tissue. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15 (1), 2750. 10.1038/s41467-024-46832-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.