Abstract

Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans is an acidophilic chemolithoautotroph that plays an important role in biogeochemical iron and sulfur cycling and is a member of the consortia used in industrial hydrometallurgical processing of copper. Metal sulfide bioleaching is catalyzed by the regeneration of ferric iron; however, bioleaching of chalcopyrite, the dominant unmined form of copper on Earth, is inhibited by surface passivation. Here, we report the implementation of CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) using the catalytically inactive Cas12a (dCas12a) in A. ferrooxidans to knock down the expression of genes in the petI and petII operons. These operons encode bc1 complex proteins and knockdown of these genes enabled the manipulation (enhancement or repression) of iron oxidation. The petB2 gene knockdown strain enhanced iron oxidation, leading to enhanced pyrite and chalcopyrite oxidation, which correlated with reduced biofilm formation and decreased surface passivation of the minerals. These findings highlight the utility of CRISPRi/dCas12a technology for engineering A. ferrooxidans while unveiling a new strategy to manipulate and improve bioleaching efficiency.

Keywords: metabolic engineering, CRISPR/Cas, CRISPR interference, iron metabolism, sulfur, chalcopyrite, biomining

Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans oxidize iron or reduced inorganic sulfur compounds (RISCs) and have generated interest for use in metal bioleaching as well as additional biotechnology applications (1, 2). In a bioleaching process, metal sulfide ores are oxidized via ferric iron and proton attack, either through direct contact mechanisms or indirect interactions, and dissolution can proceed through thiosulfate mechanisms or polysulfide mechanisms (3). The oxidation of many sulfides can be incomplete, as surface passivation can occur. This is especially problematic for the oxidation of chalcopyrite (CuFeS2), which holds 70% of the unmined copper on Earth, and this material will need to be processed to supply the copper necessary for global electrification. Surface passivation occurs through the formation of jarosite, oxides and polysulfide, and the extent of surface passivation is influenced by biofilm formation (4, 5, 6). Given that the RISC metabolism of A. ferrooxidans both directly and indirectly influences cell adherence and biofilm formation (7, 8), the manipulation of cellular metabolism (i.e. iron vs RISC utilization) may impact surface passivation, consequently affecting the extent of bioleaching of chalcopyrite and other sulfidic ores.

During aerobic growth, electrons from iron and sulfur are used to reduce O2 or to produce reducing power (NAD(P)H) through a series of protein complexes (Fig. 1A). The cytochrome bc1 complex (cytochrome b [PetB], cytochrome c1 [PetC], and the Rieske iron-sulfur protein [PetA]) (9, 10, 11) plays an important role in these processes, enabling electron transfer and proton translocation across the membrane, thus contributing to ATP synthesis (10, 12) (Fig. 1B). Under variations in substrate availability or redox states, electron flow can be directed to different pathways, optimizing energy production and metabolic efficiency (13). This electron bifurcation allows the organism to adapt to changing environmental conditions and optimize energy utilization. Due to the various oxidation states of RISCs and the combined involvement of both enzymatic and nonenzymatic reactions in sulfur oxidation (1, 14), the electron fluxes in A. ferrooxidans in environments rich in both iron and reduced sulfur, such as sulfidic ores and acid mine drainage (15, 16), are expected to be complex.

Figure 1.

Overview of iron and sulfur oxidation proteins and electron transport pathways of A. ferrooxidans.A, protein complexes implicated in iron and sulfur oxidation, (B) structural diagram of the bc1 complex, and (C) electron fluxes that occur during iron and sulfur oxidation under different conditions. In Panel B, an electron is serially transferred to Rieske iron-sulfur protein (PetA, Uniprot identification Q93A06) and cytochrome c1 (PetC, Uniprot identification Q93A10), as ubiquinol is oxidized at Qo site. Simultaneously, another electron travels back across the membrane through cytochrome b (PetB, Uniprot identification Q9KIW3), contributing to the reduction of quinone at the Qi site. In Panel C, the electrons from the oxidation of iron and RISCs are transmitted either to reduce O2 or NAD + via electron carrier proteins, in the presence of iron (blue), iron and low sulfur (0.1%, w/v) (red), and iron and high sulfur (0.5%, w/v) (black, hypothetical). During iron oxidation, approximately 95% of electrons are transported to downhill pathway (Cyc2 → Rusticyanin (Rus) → Cyc1 → aa3 oxidase) and 5% of electrons are passed uphill pathway (Cyc2 → Rus → CycA1 → bc1 complex (encoded by petI operon)→ Quinone pool (Q pool) → NADH hydrogenase (NDH)). During sulfur oxidation, the electrons are directly transmitted to enzymes (Q pool → bc1 complex (encoded by petII operon) → (Hipip and CycA2) → aa3 oxidase), or bd/bo3 complexes), or directly to NDH for NAD+ reduction. Arrows with dashed or X marks indicate lower or inhibited electron flows, respectively. IM, inner-membrane; Qi, quinol-reduction site; OM, outer-membrane; Qo, quinone oxidation site. The Figure was created by Biorender.com.

In the most studied A. ferrooxidans type strain (ATCC 23270), two distinct cytochrome bc1 complexes are expressed (Fig. 1). The bc1 complex proteins of the petI operon are expressed under iron-rich conditions, while the bc1 complex proteins of the petII operon are expressed under sulfur-rich conditions (11, 17). These two operons are necessary in autotrophic growth to segregate the transfer of electrons to either an “uphill” pathway for the reduction of NAD+ or to the “downhill” pathway for the reduction of oxygen, and these two operons are regulated by different promoters and transcriptional regulators, ensuring that each bc1 complex is expressed under appropriate environmental conditions. During iron oxidation, most of the electrons flow downhill for oxygen reduction, while the petI operon enables “uphill” electron transfer to the quinone pool. Under high sulfur concentrations, A. ferrooxidans prioritizes the use of sulfur over iron, due to the higher energy density of sulfur (18, 19) (Fig. 1C). Electrons are preferentially transferred “downhill” from the quinone pool by the petII bc1 complex. Thus, iron oxidation is inhibited under sulfur-rich conditions, and this can negatively affect the bioleaching of iron sulfide minerals including chalcopyrite. We hypothesized that the down-regulation of the petII operon may enhance iron oxidation under high sulfur concentrations, offering potential opportunities for influencing bioleaching mechanisms, leading to reduced surface passivation and enhancing metal sulfide bioleaching.

The use of Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated protein (Cas) system for genome editing has revolutionized genetic engineering (20). CRISPR interference (CRISPRi) uses a catalytically inactive (nuclease-deficient) Cas protein to silence target genes, enabling functional studies of genes without genome modification. Although extensively applied in many bacteria, CRISPRi applications to acidophiles, including A. ferrooxidans, have been limited. A Type IV CRISPR/Cas was identified in A. ferrooxidans ATCC23270 (21), but this endogenous system remains uncharacterized. Recently a well-established Class 2 Type II CRISPR/nuclease-deficient Cas9 (dCas9) was introduced to A. ferrooxidans (DSM 14882), and the authors used this CRISPRi to knock down the expression of the nitrogenase nifH gene, observing deceased growth on ammonium (NH4+) (22). Another study used dCas9 in Acidithiobacillus ferridurans to decrease sulfur oxidation by suppressing the expression of HdrA (heterodisulfide reductase) and TusA (thiosulfate carrier) (23). These reports demonstrate the successful transcriptional repression of target genes; however, CRISPRi has yet be used to create cells with useful new attributes. Moreover, the high off-target efficiency and cytotoxicity of Cas9 can restrict its use in many bacteria (24, 25). To address this, another Class 2 system, Cas12a (Cpf1) has become a useful alternative with functional advantages, such as easy multiplex genome editing, compatibility with high GC organisms (such as A. ferrooxidans), and lower toxicity (25, 26, 27, 28). However, the use of Cas12a based CRISPRi systems in non-model bacteria, including extremophiles, has been rarely reported.

Here, we report CRISPRi with DNase-deactivated Francisella novicida Cas12a (dCas12a) in A. ferrooxidans. After optimizing the CRISPRi system in Escherichia coli for enhanced knockdown efficiency, this system was investigated in A. ferrooxidans to reduce expression of the petA2 and petB2 genes (in the petII operon), and the petA1 and petB1 genes (in the petI operon). The mutant cells responded differently depending on available sulfur concentrations and the cells were further evaluated for their impact on the bioleaching of the sulfidic ores, pyrite and chalcopyrite, as well as the impact of these mutations on biofilm formation and surface passivation.

Results

dCas12a constructed in pJRD vector was evaluated in E. coli

The catalytically active FnCas12a (29) was cloned into pJRD215, a broad-host-range mobilizable vector that has been used for the transformation of A. ferrooxidans (1) (Fig. 2A). The expression of the Cas gene was controlled by tac promoter, which is a strong constitutive promoter effective for gene expression in A. ferrooxidans (30). The FnCas12a was converted to a catalytically inactivated form (dCas12a) by introducing the D917A/E1006A double mutations, inactivating the DNase activity without interrupting the RNA processing and DNA binding (29, 31).

Figure 2.

gRNA design for dCas12a CRISPRi in A. ferrooxidans. A, a schematic diagram of the dCas12a system constructed in the pJRD215 vector. The catalytically active FnCas12a (29) and the J23119 promoter up to the first direct repeat sequences were amplified from pFnCpf1_min, followed by inactivation of Cas12a and insertion of spacers, then cloned onto pJRD215 vector with rrnB terminator. The FnCas12 was made catalytically inactive by D917A/E1006A mutations (dCas12a), and the expression of the designed dCas12a system is controlled by tac promoter. B, different designs of dCas12a arrays with one target spacer with different sequences (placY1 and placY2), and two target spacers (placY3). C, predicted secondary structures of the different ddCas12 designs with placY1, placY2, and placY3 formulated by NUPACK webserver (http://www.nupack.org/) (59, 60). The free energy of the secondary structure was estimated. D, growth of E. coli cells (lacY1, lacY2, and lacY3) transformed with placY1, placY2, and placY3 plasmids, respectively, under lactose, in terms of OD600. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of triplicate biological replicates. Symbols indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05): ∗, compared to lacY1; #, compared to lacY2; †, compared to lacY3.

We inserted the dCas12a following the J23119 promoter up to the first direct repeat from pFnCpf1_min (29), into pJRD215 vector, in which the expression of the designed dCas12a is controlled by tac promoter (Fig. 2A). The lacY gene was chosen as a target for knockdown in E. coli cells as it can be used as a growth-dependent phenotype. As the design of CRISPR RNA (crRNA) affects RNA processing and targeting efficiency (32), the arrays were designed with one target spacers (20 bp) with different sequences in placY1 and placY2, and with two target spacers in placY3 (Fig. 2B). For placY1 and placY2 plasmids, additional sequences (TTTTTTGTCTAGCTTTAATGC) from pFnCpf1_min were included to ensure sufficient physical space for dCas12a to process the designed crRNA, avoiding potential interference by rrnB. In addition, this additional sequence was slightly modified in placY3 (TTTTCCAGAACTATTTAATGC) to maximize free energy of secondary structure. Structural analyses were performed by NUPACK, and the placY1 showed secondary structures (Fig. 2C), which can potentially disrupt the proper operation of the CRISPR array. The placY2 showed better RNA structure with proper folding of direct repeats, while the placY3 further improved the structures, resulting in a higher free energy. Then, these different dCas12a arrays were evaluated for growth suppression of E. coli cells. Under lactose conditions, the growth of E. coli transformed with lacY2 was inhibited by almost half as compared to the cells with lacY1, while the cells with lacY3 ceased growing before reaching the exponential phase (Fig. 2D). These results indicated that the use of two target spacer sequences, while minimizing the secondary RNA structure, increased the on-target efficiency. We opted to use the two target spacers without additional sequence extension (before rrnB terminator) for the subsequent experiments, since the proper functioning of the designed CRISPR array in the absence of additional sequences was observed, in terms of knockdown efficiency, compared to the number of target spacers (data not shown). These results confirm that the dCas12a expressed via the pJRD215 vector reduced the transcription of the target gene without apparent toxicity to E. coli cells, which is important considering that plasmid transfer from E. coli to A. ferrooxidans is required for conjugal transformation.

Knockdown of petA2 and petB2 overcome suppressed iron oxidation in A. ferrooxidans

After confirming the functionality of the dCas12a expressed from the pJRD215 plasmid in E. coli, the plasmids were conjugally transferred to A. ferrooxidans. The petA2 and petB2 genes in petII operon, and petA1 and petB1 genes in petI operon, which are two highly expressed genes under growth in sulfur and iron, respectively (17), were targeted for knockdown (Fig. 1). The engineered strains were referred to as dPetA2, dPetB2, dPetA1, and dPetB1. In the absence of sulfur (Fe-only medium), the petA1 and petB1 genes were expressed at a higher level than the petA2 and petB2 genes, confirming that these genes are related to iron oxidation. The transcriptional expression levels of the targeted genes in each of the engineered cells were decreased by ∼90% as compared to the wild-type cells (Table 1). Overall, these knockdowns did not affect the expression levels of the non-targeted genes, although the expression of petA2 was increased compared to the WT in the dPetB1 strain.

Table 1.

Transcriptional gene expression of petA2, petB2, petA1, and petB1 genes in the wild type (WT) and engineered A. ferrooxidans with knockdown petA2 (dPetA2), petB2 (dPetB2), petA1 (dPetA1), and petB1 (dPetB1) genes under different growth conditions

| Cells | Transcriptional gene expression ranscriptional gene expression ( 108 copies/g cDNA) |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| petA2 | petB2 | petA1 | petB1 | |

| Fe only | ||||

| WT | 3.2 ± 0.3 | 2.1 ± 0.5 | 9.9 ± 0.2 | 8.6 ± 1.0 |

| dPetA2 | 0.51 ± 0.02∗ | 3.0 ± 0.1 | 8.7 ± 0.5 | 9.3 ± 0.9 |

| dPetB2 | 2.7 ± 0.6 | 0.13 ± 0.02∗ | 9.3 ± 0.8 | 9.0 ± 0.4 |

| dPetA1 | 3.4 ± 0.8 | 1.9 ± 0.1 | 0.25 ± 0.04∗ | 8.3 ± 0.1 |

| dPetB1 | 4.7 ± 0.3∗ | 3.1 ± 0.1 | 9.1 ± 0.5 | 0.89 ± 0.06∗ |

| Fe and low S (0.1%, w/v) | ||||

| WT | 8.3 ± 0.3 | 9.2 ± 0.8 | 7.6 ± 1.1 | 7.8 ± 0.5 |

| dPetA2 | 0.81 ± 0.02∗ | 8.7 ± 1.5 | 6.7 ± 0.2 | 7.8 ± 0.2 |

| dPetB2 | 7.3 ± 1.2 | 1.0 ± 0.1∗ | 9.1 ± 0.5 | 8.6 ± 1.1 |

| dPetA1 | 7.0 ± 0.2∗ | 8.9 ± 1.5 | 0.73 ± 0.03∗ | 7.7 ± 0.3 |

| dPetB1 | 8.4 ± 0.7 | 8.6 ± 0.9 | 7.4 ± 1.1 | 0.74 ± 0.12∗ |

| Fe and high S (0.5%, w/v) | ||||

| WT | 9.2 ± 1.1 | 9.8 ± 1.0 | 0.84 ± 0.02 | 0.14 ± 0.03 |

| dPetA2 | 1.2 ± 0.2∗ | 9.3 ± 1.1 | 6.8 ± 0.5∗ | 7.2 ± 0.1∗ |

| dPetB2 | 9.5 ± 0.1 | 0.91 ± 0.05∗ | 6.5 ± 0.2∗ | 8.1 ± 0.01∗ |

| dPetA1 | 8.8 ± 1.0 | 9.0 ± 0.9 | 1.0 ± 0.1 | 0.85 ± 0.02 |

| dPetB1 | 9.4 ± 0.8 | 9.6 ± 0.6 | 0.38 ± 0.01 | 0.29 ± 0.01 |

All tested growth medium contains 100 mM Fe2+. Symbols (∗) indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05) of the gene expressions in knockdown cells compared to the wild type cells.

When the cells were grown in iron and low sulfur media (0.1%, w/v), the expression levels of all four of the measured genes were similar in the wild type cells. And again, transcriptional expression levels of the targeted genes in each of the engineered cells were decreased by ∼90% as compared to the wild type cells. This contrasted with the iron and high sulfur conditions (0.5%, w/v), where the petA2 and petB2 genes were expressed at a higher level than the petA1 and petB1 genes. In these conditions, the transcriptional expression levels of the petA2 and petB2 genes in the engineered cells were decreased by ∼90% as compared to the wild type. However, in the dPetA1 and dPetB1 knockouts, the lower levels of expression of the iron related petA1 and petB1 were not further suppressed, and in the dPetA2 and dPetB2 knockouts, increased levels of expression of petA1 and petB1 were observed.

Overall, these results demonstrate the successful knockdown of the targeted genes in A. ferrooxidans with low off-target efficiency by the dCas12a system constructed in the pJRD plasmid. The tac promoter successfully drove the expression of the dCas12 and when combined with the J23119 promoter, the design was sufficient to support the expression of downstream designed CRISPRi array gRNA sequences in A. ferrooxidans, as has been observed in other extremophiles (33, 34, 35).

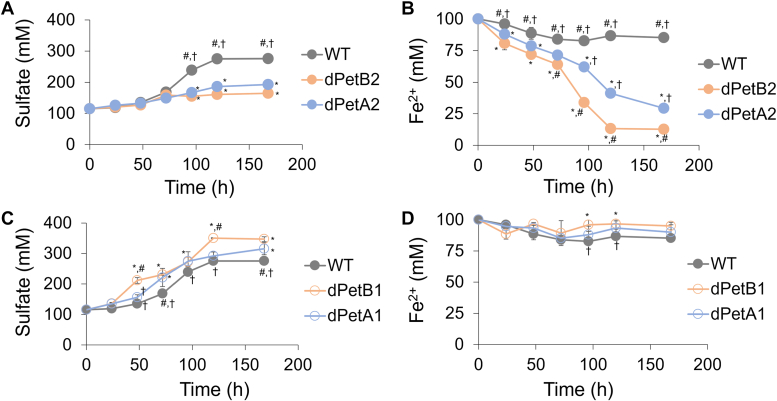

The engineered cells were grown under different iron and sulfur concentrations, and their phenotypic responses were compared to the wild-type cells. Under the high sulfur conditions (0.5%, w/v), the wild-type cells oxidized sulfur while the iron oxidation was found to be repressed (Fig. 3, A and B), which is consistent with the low expression of the petA1 and petB1 genes. This was in contrast to the dPetA2 and dPetB2 strains which oxidized Fe2+, and less sulfur was oxidized by both cell lines (Fig. 3, A and B). The effect was more pronounced in the dPetB2 cells. These results suggest that the knockdown of either the petA2 or petB2 genes, which resulted in an increase in the petA1 and petB1 genes, enables the cells to overcome the suppression of iron oxidation that normally occurs under high sulfur conditions (Fig. 1 and Table 1). In contrast, the profiles of iron oxidation were comparable among both dPetA2 and dPetB2 engineered and wild type cells when growing only with iron, which supports the functions of the petA2 and petB2 genes for the support of sulfur oxidation (Fig. S1 and Table 1). The knockdowns of the petA1 and petB1 genes showed the opposite results, as the iron oxidation remained largely suppressed, while the sulfur oxidation was similar or enhanced as compared to the wild type cells (Fig. 3, C and D). The repressed iron oxidation of both dPetA1 and dPetB1 cells in iron only medium further supports the functional roles of these genes in iron oxidation (Fig. S1 and Table 1).

Figure 3.

Sulfur and iron oxidation under high sulfur conditions. Profiles of sulfate production and Fe2+ consumption of the wild type (WT) and engineered A. ferrooxidans with knockdown petA2 (dPetA2) and petB2 (dPetB2) genes (A and B), and petA1 (dPetA1) and petB1 (dPetB1) genes (C and D), under high sulfur conditions (0.5% S, w/v) over time. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of triplicate biological replicates. Symbols indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05): ∗, compared to WT; #, compared to dPetA2 (for A and B) or dPetA1 (for C and D); †, compared to dPetB2 (for A and B) or dPetB1 (for C and D).

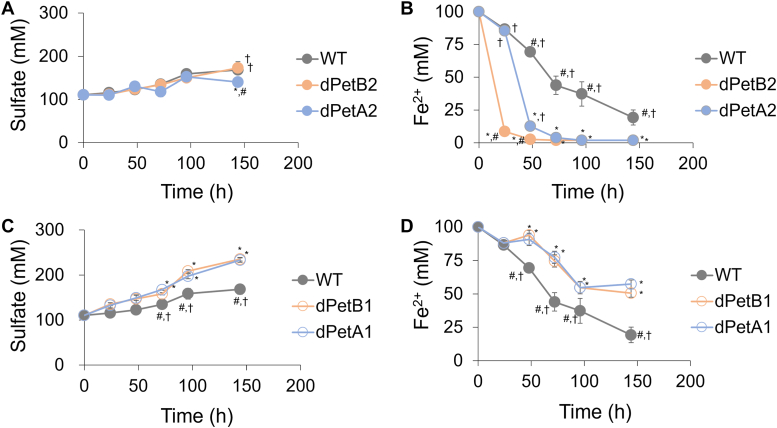

Different effects were seen under lower sulfur conditions (0.1% S, w/v) (Fig. 4). Sulfur oxidation by the dPetA2 and dPetB2 cells were similar to the wild type while the iron oxidation was even further accelerated in the knockdowns, with dPetB2 again showing the greatest effect (Fig. 4, A and B). However, under these same conditions, the dPetA1 and dPetB1 cells exhibited enhanced sulfur oxidation. The knockdowns of the petA1 and petB1 genes led to reduced iron oxidation as compared to the wild type cells, which is not surprising considering the majority of electrons (∼95%) from iron transfers via the downhill pathway (Figs. 1 and 4, C and D). Overall, these results indicate that A. ferrooxidans derives energy preferably from sulfur over iron when both substrates are present, and this can be manipulated in either direction with the knockdowns of the two different bc1 complexes (Figs. 3 and 4).

Figure 4.

Sulfur and iron oxidation under low sulfur conditions. Profiles of sulfate production and Fe2+ consumption of the wild type (WT) and engineered A. ferrooxidans with knockdown petA2 (dPetA2) and petB2 (dPetB2) genes (A and B), and petA1 (dPetA1) and petB1 (dPetB1) genes (C and D), under low sulfur conditions (0.1% S, w/v) over time. Error bars indicate the standard deviations of triplicate biological replicates. Symbols indicate statistical significance (p < 0.05): ∗, compared to WT; #, compared to dPetA2 (for A and B) or dPetA1 (for C and D); †, compared to dPetB2 (for A and B) or dPetB1 (for C and D).

Enhanced iron oxidation improves bioleaching

A. ferrooxidans has been widely investigated for its role in industrial mineral sulfide bioleaching and it has been shown to participate in direct contact interactions via biofilm formation as well as indirect, non-contact interactions by planktonic cells. Given the improved iron oxidation observed under sulfur abundant conditions by the dPetA2 and dPetB2 cells, we examined the effect of these knockdowns on the bioleaching of iron-bearing sulfidic ores, pyrite (FeS2) and chalcopyrite. Since we observed the better performance of the dPetB2 cells over the dPetA2 cells, in terms of the iron oxidation (Figs. 3 and 4), only the dPetB2 and dPetB1 cells, targeting of the knockdowns of the cytochrome b, were evaluated in the bioleaching experiments, while wild type cells served as controls.

Remarkably, dPetB2 cells exhibited enhanced bioleaching efficiencies of both minerals. The dPetB2 cells achieved final iron and copper bioleaching efficiencies of 35 ± 1% and 68 ± 3% from pyrite and chalcopyrite, respectively, which are up to 4- and 3-fold higher than the dPetB1 or wild-type control strains (Fig. 5, A and B). The solid residues after the bioleaching experiments were found to be mainly composed of sulfur, jarosite, and uncreated pyrite and/or chalcopyrite, in all conditions (Fig. S2). It is noteworthy that the conditions with the dPetB2 cells had fewer peaks corresponding to jarosite, particularly for chalcopyrite, in comparison with the wild type and dPetB1 cells. Considering that the jarosite formation is the main cause of the surface passivation (36, 37), reduced jarosite formation is consistent with the higher bioleaching efficiency observed with this cell line (Fig. 5, A and B). Furthermore, elemental analysis results indicated that the peak corresponding to carbon was not identified in either the pyrite and chalcopyrite residues after the bioleaching with dPetB2 cells, compared to the wild type and dPetB1 cells (Fig. S3). This also implies that fewer dPetB2 cells and biofilm materials were attached to the minerals during the experiments.

Figure 5.

Effects of petB2 knockdown on bioleaching efficiency.A, iron leaching efficiency from pyrite (FeS2) of the wild type (WT) and engineered A. ferrooxidans with knockdown petB2 (dPetB2) and petB1 (dPetB1) genes. B, copper leaching efficiency from chalcopyrite (CuFeS2) of both wild type and engineered cells. C, quantification of planktonic cells of both wild-type and engineered cells present in the solutions after bioleaching of pyrite and chalcopyrite. D, quantification of biofilm formation of both wild-type and engineered cells from the mineral residues after bioleaching of pyrite and chalcopyrite. E, transcriptional expressions of the genes responsible for biofilm formation by A. ferrooxidans, including quorum sensing (QS), (F) extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) precursors, and (G) cyclic-di-GMP (c-di-GMP). H, copper leaching efficiency from chalcopyrite with the WT cells without (WT) or with the removal of sulfur intermediates via periodic replacement of leaching media (WT – S intermediates), and (I) the addition of sulfur intermediates (thiosulfate and tetrathionate, WT + S intermediates) (∗ indicates the statistical significance (p < 0.05) compared to the control). Error bars indicate the standard deviations of at least triplicate analyses from triplicate biological replicates. Symbols indicate the statistical significance (p < 0.05) compared to the wild type (∗) and dPetB1 cells (#), unless otherwise noted.

The mineral contact modes of the cells were further evaluated, and 2-fold more planktonic cells along with up to 4- and 6-fold less biofilm formation was observed in the pyrite and chalcopyrite bioleaching with the dPetB2 cells, respectively, as compared to the dPetB1 and wild type controls (Fig. 5, C and D). These results were consistent with the significantly lower transcriptional expression of the genes involved in the biofilm formation in A. ferrooxidans (i.e., expressions of genes responsible for quorum sensing, cyclic-di-GMP (c-di-GMP), and extracellular polymeric substance) which was observed under the bioleaching conditions for both minerals with the dPetB2 cells (Fig. 5, E–G). In addition, the expression of biofilm genes were higher in the conditions with the dPetB1 cells than the wild type cells, although both conditions showed comparable quantitative biofilm results. Overall, the enhanced bioleaching performance of the dPetB2 cells correlated with a substantial reduction in key matrices of cell attachment, and the knockout strain demonstrated a remarkable improvement in chalcopyrite bioleaching efficiency, compared to the wild type cells (Table S1).

The knockdown of the cytochrome b in the dPetB2 cells caused the cells to reduce biofilm formation and remain in a planktonic state. This appears to play a crucial role in enhancing bioleaching, considering that biofilm formation can promote surface passivation via jarosite formation (4, 5). Given that the extracellular sulfur metabolites and proteins generated in sulfur metabolism of A. ferrooxidans contribute to cell attachment and biofilm formation (7, 8), we further examined the effect of the reduced sulfur oxidation on bioleaching. This was evaluated in wild type A. ferrooxidans cells by removing or adding sulfur intermediates that are produced during sulfur oxidation to chalcopyrite bioleaching experiments. When the sulfur intermediates were removed by periodic replacement of the leaching medium, the copper bioleaching efficiency was increased by 1.4-fold (Fig. 5H). On the other hand, the bioleaching efficiencies deteriorated upon the addition of thiosulfate and tetrathionate, which are major RISCs generated during the sulfur oxidation, as compared to the controls (Fig. 5I).

Discussion

A. ferrooxidans is rare in its ability to oxidize both iron and sulfur, and the manipulation of this substrate preference will be important as these industrially important microbes are developed for biotechnology applications. Although it is known that the petI and petII operons are found to encode ubiquinol cytochrome c reductase bc1 complexes, which catalyze electron transport during iron and sulfur oxidation (11, 14, 17) (Fig. 1), a full mechanistic understanding of the roles these operons play in metabolism and substrate selectivity is lacking, partially due to limited genetic tools for these organisms. The transcriptional expressions of the genes encoding PetAB1 and PetAB2 under various growth conditions (Table 1) confirm that the expression of these proteins is influenced by the availability and abundance of energy sources. Using CRISPRi with dCas12a, we observed that the downregulation of genes petA2 and petB2 (in the petII operon) led to improved iron oxidation by A. ferrooxidans in the presence of sulfur, particularly under high sulfur conditions where the iron oxidation is most suppressed in the wild type cells (Table 1, Figs. 3, and 4). In contrast, the suppression of petA1 and petB1 genes (in the petI operon) led to decreased iron oxidation by the cells as compared to the wild type. These results indicate that the energy substrate utilization can be tuned via regulation of the expression of genes in the petI and petII operons. Moreover, it seems that knockdown of the cytochrome b (PetB) had more of an impact than the knockdown of the Rieske iron-sulfur protein (PetA) in both operons, suggesting the cytochrome b is a metabolic control point for regulating substrate utilization, given its more direct role in electron transfer with the quinone pool. In the case of the petII operon, the observation that the petB2 gene plays more a prominent role than petA2 during sulfur oxidation is consistent with its higher transcriptional gene expression compared to other genes within petII operon (17).

It is worth noting how manipulation of the major electron transport gene influences the metabolic pathways within A. ferrooxidans. A signal transducing system RegBA has been suggested to bind to the operons involved in iron or sulfur oxidation in A. ferrooxidans (38), in response to redox changes in the quinone pool. Variations in electron fluxes could be sensed by the signal transducing system, allowing the cells to establish a hierarchical order of substrate utilization (39, 40). Given that cytochrome bc1 complexes bifurcate electron transfer upon substrate availability for energy conservation (13, 41), targeting major genes controlling electron transfer, as opposed to targeting a specific gene responsible for iron/sulfur oxidation, leads to the significant attenuation of overall substrate utilization by single gene knockdowns. The observed metabolic flexibility of A. ferrooxidans could also impact the growth and adaptation of the cells to varying environmental conditions, which is consistent with its competitiveness in different ecological niches.

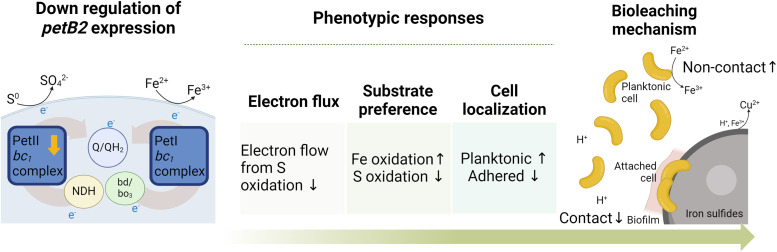

The enhanced iron oxidation of A. ferrooxidans under sulfur-abundant conditions can have a significant impact on metal recovery from sulfidic ores, such as chalcopyrite which is the most abundant yet recalcitrant copper sulfide (4). Remarkably, bioleaching with the dPetB2 cells resulted in approximately 70% of the copper being extracted from chalcopyrite, which is substantially better than what has ever been reported for the bioleaching efficiency of this mineral (Table S1) (6, 42, 43). During the bioleaching of chalcopyrite, direct contact by cells in biofilms as well as non-contact by planktonic cells contributes to copper liberation (6). The knockdown of the petB2 gene led to increased iron oxidation and this correlated with the cell localization during the bioleaching, as these cells exhibited a tendency towards a planktonic state, with lower biofilm formation and related biofilm gene expression (Figs. 5, C–G and S3). These results suggest that the dominant bioleaching mechanisms can be engineered by regulating the metabolic gene expressions in A. ferrooxidans. It is plausible that the promoted iron oxidation combined with the reduced sulfur oxidation spontaneously encourages the activity of the planktonic cells, thus the overall bioleaching was shifted to favor the indirect, non-contact pathway (Fig. 6). The higher cell attachment to minerals under the bioleaching conditions with the dPetB1 cells supports this possibility (Fig. S3). Although the cell attachment is an important step for the mineral bioleaching, the excessive biofilm formation likely promotes surface passivation of chalcopyrite via jarosite formation, which inhibits the bioleaching (6). We observed less jarosite formation under the dPetB2 conditions (Fig. S2), and we found that the bioleaching of chalcopyrite by the wild type cells was increased or decreased when removing (media replacement) or adding the sulfur metabolites, respectively (Fig. 5, H and I). Therefore, we conclude that the reduced cell attachment coupled with enhanced iron oxidation enabled the improved bioleaching of the pyrite and chalcopyrite.

Figure 6.

Proposed impacts of petB2 knockdown on phenotypic shifts of A. ferrooxidans and mechanistic consequences during bioleaching. The observed phenotypic responses during the growth and bioleaching, in terms of substrate utilization, cell localizations, and dominant bioleaching mechanisms, which were triggered by the down-regulation of petB2 gene expression are depicted. The figure was created by Biorender.com.

It is noteworthy that such high chalcopyrite bioleaching efficiencies are not commonly observed with iron-oxidizing bacteria alone, such as Leptospirillum sp (5). This phenomenon may be partially attributed to the stronger adhesion forces exhibited by Leptospirillum sp., on minerals, in comparison to other bioleaching organisms including A. ferrooxidans (44). Rapid cell adhesion by Leptospirillum ferriphilum leads to the swift coverage of chalcopyrite surfaces with sulfur and substantial amounts of jarosite, which result in low copper extraction (45). Furthermore, recent studies indicate that a deficiency of sulfur-oxidizing bacteria during bioleaching can result in low mineral dissolutions (46, 47, 48). Indeed, a previous bioleaching experiment using dialysis membranes reported that the bioleaching of copper waste materials reached the lowest efficiency when solely relying on the contact mechanism by A. ferrooxidans (49). Considering that the dPetB2 cells can still oxidize sulfur, these cells likely overcome the restricted chalcopyrite bioleaching through accelerated iron oxidation, while maintaining sulfur oxidation to some extent. This advantage could be reinforced by the reduced formation of jarosite. Our observations suggest that an increase in the contribution of the non-contact iron oxidation over the direct contact oxidation mechanism can enhance the bioleaching of iron sulfide ores.

The limited repertoire of genetic tools available for A. ferrooxidans has significantly impeded the comprehensive characterization of its unique physiological traits and constrained the exploration of its promising practical applications. Although the CRISPR/Cas system has been widely used for genome editing and silencing, it has been poorly explored in extremophiles due to the harsh growth conditions. Particularly for acidophiles, only two recent studies explored the CRISPRi with dCas9 in A. ferrooxidans (22) and A. ferridurans (23). We demonstrate the applicability of the CRISPRi/dCas12a in an environmentally and industrially important biomining organism, A. ferrooxidans, and explore the phenotypic responses of the core genes involved in the key metabolic processes of this organism. The technical advantages of Cas12a over Cas9 should enable the multiplexing of genome editing, which will accelerate our ability to explore the poorly characterized metabolic pathways of this organism. Furthermore, the compatibility of the based Cas12a/CRISPRi system provides a versatile molecular tool for genetic manipulation of other extremophiles, where genetic modification is often challenging.

Experimental procedures

Experimental design

The objective of this study was to use CRISPRi to attenuate the expression of the electron transport chain bc1 complex genes in A. ferrooxidans to regulate the flux of electrons from iron or sulfur oxidation towards NADH regeneration or oxygen reduction. Impacts on substrate utilization and growth were characterized, and the impact of the petB2 knockdown on mineral bioleaching was investigated. This provided new insights the bioleaching mechanisms, including the importance of non-contact interactions and the inhibitory effects of sulfur intermediates.

Experimental materials

Strains used in this study include E. coli DH10β and E. coli BL21 obtained from NEB (Ipswich, MA), E. coli S17-1 ATCC 47055, and A. ferrooxidans ATCC 23270 purchased from ATCC. All A. ferrooxidans strains were initially grown in 100 ml of iron and sulfur growth media (F2S medium) with an initial optical density measured at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.001, which corresponds to a cell density of 8.3 × 106 cells/ml (50), in shaking incubator (30 °C and 140 rpm). The F2S medium consisted of (NH4)2SO4, 0.8 g/L; HK2PO4, 0.1 g/L; MgSO4·7H2O, 2.0 g/L; Trace mineral solution (MD-TMS, ATCC), 5 ml/L; citric acid, 1.92 g/L; FeSO4·7H2O, 27.8 g/L; and dispersed sulfur (#S789400, Toronto Research Chemicals), 0.1% (w/v). The media was filtered through a 0.2 μm pore size (Thermo Fisher Scientific) prior to use, and sulfur was added to the media after filtration. The pFnCpf1_min (pY002) (29) plasmid expressing FnCpf1 (Cas12a) and spacers 1 to 4 of CRISPR array following the J23119 promoter, from Francisella tularensis subsp. Novicida, was sourced from Addgene (#69975).

Enzymes and reagents for DNA manipulation were obtained from NEB, and oligonucleotides were purchased from Integrated DNA Technologies. All strains, plasmids, and oligonucleotides used in this study were present in Tables S2–S4.

Pyrite (FeS2, Cat# 77817) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich and chalcopyrite (CuFeS2) concentrate (24.8% Cu, 27.2% Fe, and 30.7% S) was provided by Freeport-McMoRan and described elsewhere (6). All chemicals were sourced from Sigma-Aldrich, unless otherwise noted.

Plasmid construction and genetic manipulation

Given the four native gRNA sequences that are from the original F. novicida strain following the J23119 promoter, the sequences up to the end of the first native gRNA (with direct repeat sequence of 5′ GTCTAAGAACTTTAAATAATTTCTACTGTTGTAGAT) were amplified and cloned into pYI11 vector, the empty pJRD vector with tac promoter, using pYI28 primers (Table S3) via NEBuilder HiFi DNA Assembly following the manufacturer's instructions. The resulting construct (pJRD_Cas12a) was then converted into a catalytically inactivated form by introducing the E1006A and D917A double mutations in pJRD_Cas12a via Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (NEB), using pYI30 and pYI49 primers, respectively (Table S3). The final plasmid (pJRD_dCas12a) was referred to as dCas12a.

To make the pPetA2, pPetB2, pPetA1, and pPetB1 plasmids for knockdown the petA2, petB2, petA1, and petB1 genes, respectively, the two target spacer sequences for each target gene (Table S4) with a 19-nt direct repeat sequence (5′ AATTTCTACTGTTGTAGAT) (51), which contains the cleavage site to separate the first crRNA from the second crRNA, were inserted into the pJRD_dCas12a by Q5 Site-Directed Mutagenesis Kit (NEB), using relevant primer sets (Table S3). All constructed plasmids were transformed into E. coli DH10β for sequence verification before use. The gRNA sequences were designed using Benchling and CHOPCHOP((52)).

After verification, placY1–Y3 were transformed into E. coli BL21 and referred to as lacY1, lacY2, and lacY3, respectively. In addition, the sequence verified pPetA2, pPetB2, pPetA1, and pPetB1 were conjugally transferred to A. ferrooxidans by filter mating technique using the donor strain E. coli S17-1, as previously described (53). The resulting transconjugants were recovered in AFM1 medium containing 0.8 g/L, (NH4)2SO4; 0.1 g/L, HK2PO4; 2.0 g/L, MgSO4·7H2O; 5 ml/L, MD-TMS; and 72 mM, FeSO4·7H2O (final pH of 1.8) and screened in SM4 selection medium containing 0.8 g/L, (NH4)2SO4; 2.0 g/L, MgSO4·7H2O; 0.1 g/L, K2HPO4; 0.19 g/L, citric acid; 5 ml/L, MD-TMS; 40 μg/ml, leucine; 19 μg/ml, diaminopimelic acid; 17.9 μg/ml, Fe2(SO4)3; 1 g/L, dispersed sulfur; (final pH of 5.0) with kanamycin (50 mg/ml) to isolate the engineered cells. The isolated strains recombinantly expressing pPetA2, pPetB2, pPetA1, and pPetB1 were referred to as dPetA2, dPetB2, dPetA1, and dPetB1, respectively.

Quantification of transcriptional gene expression

The wild type and engineered strains (dPetA2, dPetB2, dPetA1, and dPetB1) were harvested at the stationary phase during the growth under 50 ml of F2S medium. Total RNA of the cells was extracted using RNeasy Mini kit (Qiagen), and reversely transcribed to cDNA using QuantiTech Reverse Transcription Kit (Qiagen), as per the protocols. The concentration of petA2, petB2, petA1, and petB1 genes were analyzed by QIAcuity Digital PCR (dPCR) System (Qiagen). In addition, the expressions of genes responsible for biofilm formation were measured after the bioleaching experiments. 1 ml of cell-mineral mixtures was collected from each condition of the bioleaching. The total RNA was extracted, then converted to cDNA, as described previously (54). Several genes that were proposed to encode the extracellular polymeric substance (EPS) precursors UDP-glucose, UPD-galactose, and dTDP-rhamnose (luxA, AFE_2321; pgm, AFE_2324; galU; and AFE_2323) (55), and genes encoding two distinct signaling mechanisms of quorum sensing (afeI, AFE_1999) (54) and c-di-GMP (AFE_0053, AFE_1172, AFE_1360, AFE_1373, AFE_1374, AFE_1379, and AFE_1852) (56), which regulate the biofilm formation, in A. ferrooxidans, were selected. The template cDNA was fragmented by XbaI and the dPCR reactions were carried out with the QIAcuity EG PCR Kit (Qiagen), following the manufacturer’s instructions. The absolute copy number of genes in samples was calculated using Poisson statistics and the final transcriptional gene expression was normalized with cDNA concentration of sample. The primer sequences for the dPCR reactions were present in Table S3.

Phenotypic evaluation of CRISPRi

The effect of the different CRISPR arrays (i.e., number of gRNA and secondary structure) on knockdown efficiency was evaluated in E. coli cells. The lacY1, lacY2, and lacY3 cells were grown in M9 medium (57) with 0.4% lactose to limit the cell to use lactose for growth, while the lactose induces the tac promoter to express our dCas12a systems. The growth of cells with different CRISPR array were monitored, in terms of OD measured at 600 nm.

The phenotypic responses of the engineered A. ferrooxidans by silencing petA2 and petB2 genes were examined by the growth tests with different sulfur concentrations. The dPetA2 and dPetB2 cells were grown in 100 ml of F2S medium with low (0.1%, w/v) and high (0.5%, w/v) dispersed sulfur. The profiles of iron and sulfur oxidations of the conditions were monitored, in comparison with the wild type, dPetA1, and dPetB1 cells. For dPetA2 and dPetB2 cells, the growth in the absence of sulfur (F2S medium without sulfur) was additionally assessed. The growth tests with A. ferrooxidans were performed in a shaking incubator (30 °C and 140 rpm), in triplicate biological replicates.

Bioleaching experiments

Bioleaching experiments were conducted to see if the improved iron oxidation by repressing the gene involved in the sulfur oxidative electron transfer pathway can affect the bioleaching of the sulfidic ores. Since we observed that the downregulating effects for the tested genes were more obvious in dPetB2 cells than dPetA2, the bioleaching experiments were performed only with the dPetB2, in comparison with the wild-type and dPetB1 cells.

Bioleaching experiments of pyrite and chalcopyrite were conducted in 250 ml Erlenmeyer flasks with working volumes of 100 ml. The leaching media consisted of 0.8 g/L, (NH4)2SO4; 0.1 g/L, K2HPO4; 2.0 g/L, MgSO4·7H2O; 5 ml/L, MD-TMS, and 10 mM, citric acid (final pH of 1.8). For chalcopyrite bioleaching, 100 mM of FeSO4·7H2O was added to accelerate initial leaching due to the poor bioleaching efficiency of this mineral (6, 42, 43). Wild type or engineered cells (dPetB2 or dPetB1) at OD600 of 1.0 were inoculated to adjust the initial cell density of 8.3 × 107 cells/ml. In addition, the effect of the presence of sulfur intermediates on the bioleaching was further examined either by removing or adding sulfur intermediates during the bioleaching of chalcopyrite with the wild type cells. The wild type cells at an initial OD600 of 0.01 were inoculated to a 14 ml Falcon round-bottom tube with a 10 ml working volume (the same leaching media used for the chalcopyrite bioleaching above). For removing the sulfur metabolites, the leaching solution was periodically replaced (once in 1–3 days) with fresh media. For adding sulfur intermediates, thiosulfate (sodium thiosulfate) tetrathionate (sodium tetrathionate dihydrate), which are the common sulfur metabolites produced during the bioleaching of sulfidic ores, were exogenously added at the final concentrations of 50 μM. The conditions without removing or adding sulfur intermediates were operated as controls. For all bioleaching experiments, the pulp densities of pyrite or chalcopyrite of 1.0% (w/v) were used. All experimental conditions were run in triplicate biological replicates and incubated at 30 °C and 140 rpm. The water evaporation was compensated by adding distilled water, and pH was not adjusted as it was maintained below two for all tested conditions throughout the experiments.

Analytical methods

OD600 was measured using a GENESYS 10S UV-VIS spectrophotometer. The soluble Fe2+ concentrations were measured by titration with cerium sulfate with a ferroin indicator, and sulfate concentration was measured using a barium sulfate turbidimetric method, as previously described (6, 58). After the bioleaching experiments, total soluble iron and copper concentrations were analyzed by atomic absorption spectrometer (iCE 3300, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). The solid residues after the bioleaching were characterized with a PANalytical XPert3 Powder X-ray diffraction (XRD) with Empyrean Cu Ka radiation (k = 0.15418 nm) equipped with a PIXcel1D detector, and a Zeiss-Sigma VP scanning electron microscopy (SEM) connected to a Bruker XFlash Detector. The sample preparations for XRD and SEM were described previously (6). Biofilm formation was quantified using crystal violet assay, following the previous description (6). For quantifying the number of planktonic cells, 1 ml of cell-mineral mixtures were filtered through a membrane filter with 0.7 μm pore size, then the filter-through was mixed with 5× SYBR Green I nucleic acid stain (Invitrogen, USA), according to the previous method (50).

Statistical analysis

Statistical significance was determined in Figure 2, Figure 3, Figure 4, Figure 5, S1 and Table 1 by one-way ANOVA (p < 0.05). All experiments were performed in at least triplicate.

Data availability

All data is contained with the manuscript and Supporting information.

Supporting information

This article contains supporting information (61).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest with the contents of this article.

Acknowledgments

Author contributions

Y. I., S. B., and H. J. writing–review & editing; Y. I. and H. J. methodology; Y. I., S. B., and H. J. formal analysis; Y. I., S. B. and H. J. conceptualization; S. B. supervision; S. B. project administration; S. B. funding acquisition; H. J. writing–original draft; H. J. investigation; H. J. data curation.

Funding and additional information

The authors gratefully acknowledge support from ARPA-E grant DE-AR0001340 from the U.S. Department of Energy.

Reviewed by members of the JBC Editorial Board. Edited by Joseph Jez

Supporting information

References

- 1.Jung H., Inaba Y., Banta S. Genetic engineering of the acidophilic chemolithoautotroph Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Trends Biotechnol. 2022;40:677–692. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2021.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma A., Kawarabayasi Y., Satyanarayana T. Acidophilic bacteria and archaea: acid stable biocatalysts and their potential applications. Extremophiles. 2012;16:1–19. doi: 10.1007/s00792-011-0402-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sand W., Gehrke T., Jozsa P.-G., Schippers A. (Bio)chemistry of bacterial leaching—direct vs. indirect bioleaching. Hydrometallurgy. 2001;59:159–175. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fu B., Zhou H., Zhang R., Qiu G. Bioleaching of chalcopyrite by pure and mixed cultures of Acidithiobacillus spp. and Leptospirillum ferriphilum. Int. Biodeterioration Biodegradation. 2008;62:109–115. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gu G.-h., Hu K.-t., Li S.-k. Bioleaching and electrochemical properties of chalcopyrite by pure and mixed culture of Leptospirillum ferriphilum and Acidthiobacillus thiooxidans. J. Cent. South Univ. 2013;20:178–183. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jung H., Inaba Y., Vardner J.T., West A.C., Banta S. Overexpression of the Licanantase protein in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans leads to enhanced bioleaching of copper minerals. ACS Sust. Chem. Eng. 2022;10:10888–10897. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Valdés J., Veloso F., Jedlicki E., Holmes D. Metabolic reconstruction of sulfur assimilation in the extremophile Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans based on genome analysis. BMC Genomics. 2003;4:51. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-4-51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Vera M., Krok B., Bellenberg S., Sand W., Poetsch A. Shotgun proteomics study of early biofilm formation process of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans ATCC 23270 on pyrite. Proteomics. 2013;13:1133–1144. doi: 10.1002/pmic.201200386. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berry E.A., Huang L.-S. Conformationally linked interaction in the cytochrome bc1 complex between inhibitors of the Qo site and the Rieske iron–sulfur protein. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2011;1807:1349–1363. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Xia D., Esser L., Tang W.-K., Zhou F., Zhou Y., Yu L., et al. Structural analysis of cytochrome bc1 complexes: implications to the mechanism of function. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2013;1827:1278–1294. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2012.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brasseur G., Bruscella P., Bonnefoy V., Lemesle-Meunier D. The bc1 complex of the iron-grown acidophilic chemolithotrophic bacterium Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans functions in the reverse but not in the forward direction: is there a second bc1 complex? Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2002;1555:37–43. doi: 10.1016/s0005-2728(02)00251-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Trumpower B.L. Cytochrome bc1 complexes of microorganisms. Microbiol. Rev. 1990;54:101–129. doi: 10.1128/mr.54.2.101-129.1990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brandt U. Energy conservation by bifurcated electron-transfer in the cytochrome-bc1 complex. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 1996;1275:41–46. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(96)00048-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhan Y., Yang M., Zhang S., Zhao D., Duan J., Wang W., et al. Iron and sulfur oxidation pathways of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019;35:1–12. doi: 10.1007/s11274-019-2632-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Duarte F., Araya-Secchi R., González W., Perez-Acle T., González-Nilo D., Holmes D.S. Protein function in extremely acidic conditions: molecular simulations of a predicted aquaporin and a potassium channel in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Adv. Mater. Res. 2009;71:211–214. [Google Scholar]

- 16.González-Toril E., Llobet-Brossa E., Casamayor E., Amann R., Amils R. Microbial ecology of an extreme acidic environment, the Tinto River. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003;69:4853–4865. doi: 10.1128/AEM.69.8.4853-4865.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bruscella P., Appia-Ayme C., Levicán G., Ratouchniak J., Jedlicki E., Holmes D.S., et al. Differential expression of two bc1 complexes in the strict acidophilic chemolithoautotrophic bacterium Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans suggests a model for their respective roles in iron or sulfur oxidation. Microbiology. 2007;153:102–110. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2006/000067-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Beschkov V., Razkazova-Velkova E., Martinov M., Stefanov S. Electricity production from marine water by sulfide-driven fuel cell. Appl. Sci. 2018;8:1926. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Inaba Y., Kernan T., West A.C., Banta S. Dispersion of sulfur creates a valuable new growth medium formulation that enables earlier sulfur oxidation in relation to iron oxidation in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans cultures. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2021;118:3225–3238. doi: 10.1002/bit.27847. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hille F., Richter H., Wong S.P., Bratovič M., Ressel S., Charpentier E. The biology of CRISPR-Cas: backward and forward. Cell. 2018;172:1239–1259. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.11.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Makarova K.S., Wolf Y.I., Alkhnbashi O.S., Costa F., Shah S.A., Saunders S.J., et al. An updated evolutionary classification of CRISPR–Cas systems. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2015;13:722–736. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yamada S., Suzuki Y., Kouzuma A., Watanabe K. Development of a CRISPR interference system for selective gene knockdown in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2022;133:105–109. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2021.10.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chen J., Liu Y., Mahadevan R. Genetic engineering of Acidithiobacillus ferridurans using CRISPR systems to mitigate toxic release in biomining. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023;57:12315–12324. doi: 10.1021/acs.est.3c02492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rostain W., Grebert T., Vyhovskyi D., Pizarro P.T., Tshinsele-Van Bellingen G., Cui L., et al. Cas9 off-target binding to the promoter of bacterial genes leads to silencing and toxicity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51:3485–3496. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkad170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhao J., Fang H., Zhang D. Expanding application of CRISPR-Cas9 system in microorganisms. Synth. Syst. Biotechnol. 2020;5:269–276. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2020.08.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Call S.N., Andrews L.B. CRISPR-based approaches for gene regulation in non-model bacteria. Front. Genome Editing. 2022;4 doi: 10.3389/fgeed.2022.892304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paul B., Montoya G. CRISPR-Cas12a: functional overview and applications. Biomed. J. 2020;43:8–17. doi: 10.1016/j.bj.2019.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Swarts D.C., Jinek M. Cas9 versus Cas12a/Cpf1: structure–function comparisons and implications for genome editing. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA. 2018;9 doi: 10.1002/wrna.1481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zetsche B., Gootenberg J.S., Abudayyeh O.O., Slaymaker I.M., Makarova K.S., Essletzbichler P., et al. Cpf1 is a single RNA-guided endonuclease of a class 2 CRISPR-Cas system. Cell. 2015;163:759–771. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2015.09.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kernan T., West A.C., Banta S. Characterization of endogenous promoters for control of recombinant gene expression in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Biotechnol. Appl. Biochem. 2017;64:793–802. doi: 10.1002/bab.1546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fonfara I., Richter H., Bratovič M., Le Rhun A., Charpentier E. The CRISPR-associated DNA-cleaving enzyme Cpf1 also processes precursor CRISPR RNA. Nature. 2016;532:517–521. doi: 10.1038/nature17945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Creutzburg S.C.A., Wu W.Y., Mohanraju P., Swartjes T., Alkan F., Gorodkin J., et al. Good guide, bad guide: spacer sequence-dependent cleavage efficiency of Cas12a. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020;48:3228–3243. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz1240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu C., Yue Y., Xue Y., Zhou C., Ma Y. CRISPR-Cas9 assisted non-homologous end joining genome editing system of Halomonas bluephagenesis for large DNA fragment deletion. Microb. Cell Factories. 2023;22:211. doi: 10.1186/s12934-023-02214-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qin Q., Ling C., Zhao Y., Yang T., Yin J., Guo Y., et al. CRISPR/Cas9 editing genome of extremophile Halomonas spp. Metab. Eng. 2018;47:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2018.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tsuji A., Takei Y., Azuma Y. Establishment of genetic tools for genomic DNA engineering of Halomonas sp. KM-1, a bacterium with potential for biochemical production. Microb. Cell Factories. 2022;21:122. doi: 10.1186/s12934-022-01797-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sasaki K., Nakamuta Y., Hirajima T., Tuovinen O. Raman characterization of secondary minerals formed during chalcopyrite leaching with Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Hydrometallurgy. 2009;95:153–158. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Xia J.-l., Yang Y., He H., Zhao X.-j., Liang C.-l., Zheng L., et al. Surface analysis of sulfur speciation on pyrite bioleached by extreme thermophile Acidianus manzaensis using Raman and XANES spectroscopy. Hydrometallurgy. 2010;100:129–135. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ponce J.S., Moinier D., Byrne D., Amouric A., Bonnefoy V. Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans oxidizes ferrous iron before sulfur likely through transcriptional regulation by the global redox responding RegBA signal transducing system. Hydrometallurgy. 2012;127-128:187–194. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Okano H., Hermsen R., Hwa T. Hierarchical and simultaneous utilization of carbon substrates: mechanistic insights, physiological roles, and ecological consequences. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2021;63:172–178. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2021.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Okano H., Hermsen R., Kochanowski K., Hwa T. Regulation underlying hierarchical and simultaneous utilization of carbon substrates by flux sensors in Escherichia coli. Nat. Microbiol. 2020;5:206–215. doi: 10.1038/s41564-019-0610-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuly J.L., Lubner C.E., Zhang P., Beratan D.N., Peters J.W. Electron bifurcation: progress and grand challenges. Chem. Commun. 2019;55:11823–11832. doi: 10.1039/c9cc05611d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bevilaqua D., Lahti H., Suegama P.H., Garcia Jr O., Benedetti A.V., Puhakka J.A., et al. Effect of Na-chloride on the bioleaching of a chalcopyrite concentrate in shake flasks and stirred tank bioreactors. Hydrometallurgy. 2013;138:1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Watling H. Chalcopyrite hydrometallurgy at atmospheric pressure: 1. Review of acidic sulfate, sulfate–chloride and sulfate–nitrate process options. Hydrometallurgy. 2013;140:163–180. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhu J., Li Q., Jiao W., Jiang H., Sand W., Xia J., et al. Adhesion forces between cells of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans or Leptospirillum ferrooxidans and chalcopyrite. Colloids Surf. B: Biointerfaces. 2012;94:95–100. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfb.2012.01.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gu G.-h., Hu K.-t., Li S.-k. Surface characterization of chalcopyrite interacting with Leptospirillum ferriphilum. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China. 2014;24:1898–1904. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lee M.H., Park H.J., Lee J.-U. Bioleaching of arsenic and heavy metals from mine tailings by pure and mixed cultures of Acidithiobacillus spp. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2015;21:451–458. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Ma L., Wang X., Feng X., Liang Y., Xiao Y., Hao X., et al. Co-culture microorganisms with different initial proportions reveal the mechanism of chalcopyrite bioleaching coupling with microbial community succession. Bioresour. Technol. 2017;223:121–130. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2016.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Tao J., Liu X., Luo X., Teng T., Jiang C., Drewniak L., et al. An integrated insight into bioleaching performance of chalcopyrite mediated by microbial factors: functional types and biodiversity. Bioresour. Technol. 2021;319 doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2020.124219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nie H., Yang C., Zhu N., Wu P., Zhang T., Zhang Y., et al. Isolation of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans strain Z1 and its mechanism of bioleaching copper from waste printed circuit boards. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2015;90:714–721. [Google Scholar]

- 50.Li X., Mercado R., Kernan T., West A.C., Banta S. Addition of citrate to Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans cultures enables precipitate-free growth at elevated pH and reduces ferric inhibition. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2014;111:1940–1948. doi: 10.1002/bit.25268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Yamano T., Nishimasu H., Zetsche B., Hirano H., Slaymaker I.M., Li Y., et al. Crystal structure of Cpf1 in complex with guide RNA and target DNA. Cell. 2016;165:949–962. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Labun K., Montague T.G., Krause M., Torres Cleuren Y.N., Tjeldnes H., Valen E. CHOPCHOP v3: expanding the CRISPR web toolbox beyond genome editing. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47:W171–W174. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Inaba Y., Banerjee I., Kernan T., Banta S.J.A., microbiology e. Transposase-mediated chromosomal integration of exogenous genes in Acidithiobacillus Ferrooxidans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2018;84 doi: 10.1128/AEM.01381-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jung H., Inaba Y., West A.C., Banta S. Overexpression of quorum sensing genes in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans enhances cell attachment and covellite bioleaching. Biotechnol. Rep. 2023;38 doi: 10.1016/j.btre.2023.e00789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Barreto M., Jedlicki E., Holmes D.S. Identification of a gene cluster for the formation of extracellular polysaccharide precursors in the chemolithoautotroph Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2005;71:2902–2909. doi: 10.1128/AEM.71.6.2902-2909.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Ruiz L.M., Castro M., Barriga A., Jerez C.A., Guiliani N. The extremophile Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans possesses a c-di-GMP signalling pathway that could play a significant role during bioleaching of minerals. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2012;54:133–139. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2011.03180.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Gupta R., Sharma P., Vyas V. Effect of growth environment on the stability of a recombinant shuttle plasmid, pCPPS-31, in Escherichia coli. J. Biotechnol. 1995;41:29–37. doi: 10.1016/0168-1656(95)00049-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Inaba Y., Xu S., Vardner J.T., West A.C., Banta S. Microbially influenced corrosion of stainless steel by Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans supplemented with pyrite: importance of thiosulfate. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2019;85 doi: 10.1128/AEM.01381-19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fornace M.E., Huang J., Newman C.T., Porubsky N.J., Pierce M.B., Pierce N.A. NUPACK: analysis and design of nucleic acid structures, devices, and systems. ChemRxiv. 2022 doi: 10.26434/chemrxiv-2022-xv98l. [preprint] [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zadeh J.N., Steenberg C.D., Bois J.S., Wolfe B.R., Pierce M.B., Khan A.R., et al. NUPACK: analysis and design of nucleic acid systems. J. Comput. Chem. 2011;32:170–173. doi: 10.1002/jcc.21596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Inaba Y., West A.C., Banta S. Enhanced microbial corrosion of stainless steel by Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans through the manipulation of substrate oxidation and overexpression of rus. Biotech. Bioeng. 2020;117:3475–3485. doi: 10.1002/bit.27509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data is contained with the manuscript and Supporting information.