Summary

Background

The Pacific Island country of Vanuatu is at the early stages of demographic ageing. The government is yet to develop a strategic approach to optimize the health and wellbeing of older indigenous Vanuatu residents (ni-Vanuatu).

Methods

Using policy mapping and semi-structured interviews with 42 ni-Vanuatu, this research aimed to explore the current policy context surrounding ageing in Vanuatu and the priorities of older adults to inform preliminary steps to develop a national response to healthy ageing. Analyses were grounded in the World Health Organization's Regional Action Plan on Healthy Ageing in the Western Pacific.

Findings

While the national policy context exhibited an indirect commitment to creating an environment conducive to healthy ageing, explicit policy commitments and monitoring indicators were lacking. Older persons reported numerous obstacles to healthy ageing, including financial insecurity, physical and psychological barriers to participation, and lack of community support.

Interpretation

Findings highlighted the need for policymakers and stakeholders to focus preliminary strategic efforts on select components of the Regional Action Plan: evidence generation, advocacy/awareness, financing, community engagement and coordination, and family-centred empowerment. To ensure acceptability and sustainability, it is vital that these leverage existing strengths of traditional community values and the prevailing role of faith and religion in the lives of older ni-Vanuatu.

Funding

This project was funded and supported by the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for the Western Pacific (WPRO). Outcomes reflect the deliberations of authors and research partners.

Keywords: Healthy ageing, Vanuatu, Ageing policy, Older people, Pacific Islands

Research in context.

Evidence before this study

Vanuatu is in the early stages of population ageing, yet already experiences the third highest age-related disease burden globally. Evidence of the health and social care needs of the older Vanuatu population, and the ability of existing services and infrastructure to meet these needs, is lacking. Effective delivery of health care in Vanuatu is hindered by geographic barriers, limited accessibility, low public investment in primary health care and workforce shortages. Additionally, there are no formalized models of long-term care, and family comprise the central support network for older adults living their later years of life at home. In 2022, the Ministry of Health commenced advocacy efforts to drive the development of Vanuatu's own national multi-sectoral action plan on healthy ageing. To do so required new evidence of how the existing national policy landscape addressed opportunities for healthy ageing, and an understanding of the requirements for patient-centred healthy ageing strategies from the perspective of older people themselves.

Added value of this study

This study provides the first comprehensive assessment of the policy landscape underpinning healthy ageing in Vanuatu and the self-identified needs of older adults. Our findings highlight financial security, maintaining agency and social participation, and a desire for community-based support as priority concerns of older persons. We also identify significant gaps in the degree to which Vanuatu's current policy, programs, and services address objectives of the World Health Organization's Regional Action Plan on Healthy Ageing in the Western Pacific. Specifically, we highlight the need for policymakers and ageing stakeholders to focus preliminary efforts on select components of the Regional Action Plan: evidence generation, advocacy/awareness, financing, community engagement and coordination, and family-centred empowerment.

Implications of all the available evidence

The recommendations put forward by this study can serve as a starting point for the development of a national strategic response to population ageing. There is strong potential to integrate this response with the current national policy landscape, which includes explicit mention of the needs and rights of older persons in overarching goals and objectives, and demonstrates well-defined monitoring and implementation plans. Suggested preliminary efforts identified from our research indicate that a tailored and pragmatic approach to addressing healthy ageing in Vanuatu, which considers the unique contextual challenges including geography and resources, along with the priorities of older persons, is required.

Introduction

Population ageing is progressing at a rapid pace worldwide. By 2050, 21% of the world's population (2.1 billion people) will be aged 60 or above, surpassing the proportion of children under 5 years (7.1%) and of youth aged 15–24 years (13.7%).1 This demographic shift has profound implications for the achievement of universal health coverage and provides impetus for governments to address ageing as a major policy challenge.2,3 While social policies can be used to promote healthy ageing over the life-course, many governments are hindered by limited contextually-grounded evidence on what is needed and what works to inform both effective policy and policy implementation for healthy ageing within their populations.4 This dearth of evidence is particularly evident in resource poor nations where limited translatable epidemiological data to underpin predictions of demographic and disease trends, lack of knowledge and coordination of multisectoral policies and services for older adults, and poor understanding of the priorities of older persons themselves, present significant barriers to driving evidence-based responses to population ageing.5, 6, 7 Calls to strengthen data, research and innovation to address the urgent need for evidence-informed context appropriate policy and planning solutions are intensifying.8, 9, 10

Asia–Pacific low- and middle-income countries are experiencing some of the world's most accelerated demographic transitions, resulting in rapid growth of the actual and relative numbers of older adults.11 While such increasing longevity represents a public health success, population ageing in these settings brings new challenges including an increasing burden of non-communicable diseases and declines in intrinsic capacity among older people.12, 13, 14 Effectively managing the accompanying growth in demand for health and social care poses considerable challenges for service delivery within health systems still struggling to achieve continuous and integrated care. Such circumstances are particularly evident across the Pacific Island countries, where ageing is yet to receive sufficient attention from policy makers.5,15 As a result, the health and social support needs of older persons remain underserved.5

Vanuatu is a lower middle-income Pacific Island country with a population of just over 300,000 people, approximately 99% of who are indigenous Melanesian peoples (known as ni-Vanuatu).16 With a median age of just 20 years, the country is in the early stages of this demographic transition.16 In 2020, those aged 60 years and over comprised 6.4% of the total population (19,325 people, 50% women)16 yet this proportion is expected to reach 9% by 20301 and 14% (68,000 people) by 2050.17 However, the country already experiences the third highest age-related disease burden globally18: cardiovascular diseases are responsible for just under half of all deaths in those age 60 years and older and 28% of older adults have some form of disability.19

Prior research on the health and social care needs of older ni-Vanuatu, and the ability of existing services and infrastructure to meet these needs, is lacking.20 The limited available evidence paints a picture of under-resourced and fragmented health and social care systems, inadequately prepared to manage the complexity of needs of an ageing community.21 The effective delivery of health care in Vanuatu is hindered by the unique geography of the country, limited public investment in primary health care22 and workforce shortages.22, 23, 24 Although the majority (85%) of health facilities are in rural locations including outer islands, individuals living in these areas face numerous barriers to accessing care including long waiting times and high transport costs.25,26 In terms of social support and aged care services, there are no formalized models of long-term care, and family comprise the central support network for older adults living their later years of life at home. Such support encompasses not just health and social care, but financial needs also; there is no universal old age social security benefit.27,28 As elsewhere, restrictions to reduce the spread of COVID-19 infection were applied in many sectors in Vanuatu during 2020–2022, including curfews and lockdowns, social distancing, and border closures. Such measures were found to exacerbate existing social vulnerabilities of older persons in other settings, including income security and social isolation.29

Partly hindered by this lack of relevant contextual evidence, the national government of Vanuatu is yet to establish a coordinated strategy to optimize the health and wellbeing of ni-Vanuatu as they age. Political will to address the needs of an ageing society has gained new momentum, however, spurred by the launch of the United Nations Decade of Healthy Ageing 2021–203030 and the World Health Organization's (WHO) recently revised Regional Action Plan on Healthy Ageing in the Western Pacific (‘Regional Action Plan’).31 In 2022, the Ministry of Health of Vanuatu, with support of WHO Western Pacific Regional Office and WHO Country Liaison Office for Vanuatu, commenced advocacy efforts to drive the development of Vanuatu's own national multi-sectoral action plan on healthy ageing. To do so required new evidence of how the existing national policy landscape addressed opportunities for healthy ageing, and an understanding of the requirements for patient-centred healthy ageing strategies from the perspective of older people themselves. Studying this interconnection between macro-discourses and individual practices and representations is essential to orient future social policy developments that more fully address the self-identified needs of older adults.32,33

The focus of this study was, therefore, to explore the current national policy context surrounding ageing in Vanuatu, along with the experiences and priorities of older adults, to inform preliminary steps to develop a national response to healthy ageing.

Methods

This study employed a multi-component qualitative approach, comprising a policy mapping exercise and a series of semi-structured interviews with older ni-Vanuatu. Analysis and synthesis of findings were guided by an analytical framework informed by the five objectives of the WHO Regional Action Plan.31 For the purposes of this research, healthy ageing was defined as “the process of developing and maintaining the functional ability that enables well-being in older age”.34 Ethical approval for the research was granted by the Vanuatu Ministry of Health (ref: ADPH 02/02-JS/am).

Study setting

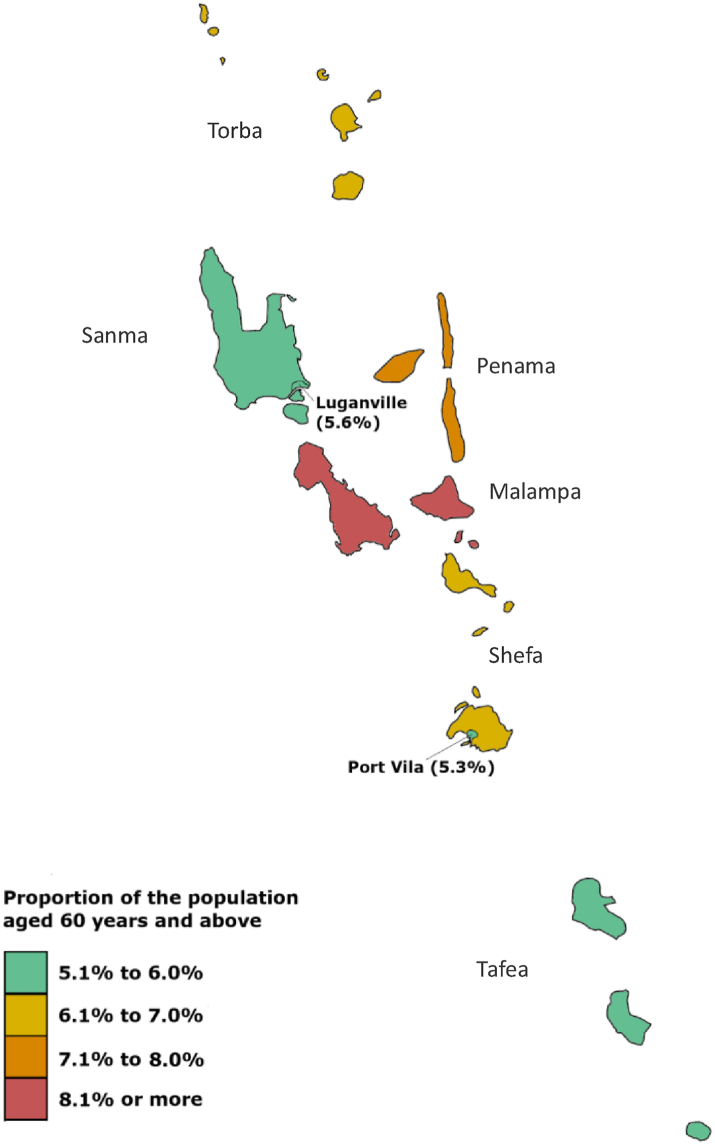

The Republic of Vanuatu lies in the southwestern Pacific Ocean, situated between the French territory of New Caledonia to the South and the Pacific Island country of Fiji to the East. The nation covers more than 80 islands (13 of which are considered principal islands) divided into six administrative provinces, each governed by a provincial council.35 The majority of the Vanuatu population live in rural areas (77.8%; 233,266 people), i.e. outside the nation's capital Port Vila and other major urban center Luganville.16 There is variation in the geographic distribution of older adults throughout Vanuatu (Fig. 1), with the highest concentration of older persons (8.3%) residing in Malampa province and the lowest (5.3%) within the nation's capital, Port Vila (Shefa province).16

Fig. 1.

Geographic distribution of persons aged 60 years and over, Vanuatu. In 2020, the province of Malampa had the highest proportion of people aged 60+ years at 8.3% (3509) of the total province population (42,499). This was followed by Penama at 7.1% (2535), Shefa at 6.7% (3673) and Torba at 6.5% (735). Port Vila and Luganville had the lowest proportion of people aged 60+ years at 5.3% and 5.6% respectively. Data source: 2020 National Population and Housing Census.

In 2020, life expectancy in Vanuatu was 69.1 years for males and 72.3 years for females. ‘Healthy life expectancy’, i.e., the average number of years that a person can expect to live in “full health”, was significantly lower at 57.8 years (56.4 years for males and 59.4 years for females).36 The potential support ratio, a measure of the number of individuals of “working age” (aged 15–60 years) likely to be economically supporting each person aged 60 years and over, was 8.5 in 2020.16 Projections indicate a reduction in the potential support ratio to 6.7 in 2050, one of the lowest across the Pacific Island countries. A selection of key population indicators relevant to healthy ageing are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Vanuatu population indicators relevant to healthy ageing.

| Population aged 60+ (% of total, 2020)a | 6.4% (19,325) |

| Aged 60+ rural | 81.4% (15,729) |

| Aged 60+ urban | 18.6% (3595) |

| Life expectancy at birth, years (2020)b | |

| Male | 69.1 |

| Female | 72.3 |

| Life expectancy at age 65, years (2016)c | |

| Male | 11.7 |

| Female | 12.3 |

| Healthy adjusted life expectancy at age 60 (2016)c | |

| Male | 8.8 |

| Female | 9.0 |

| Disability status, aged 60+ (2013)d | 27.8% |

| Age dependency ratio, older persons (65+ per 100 population aged 15–64) (2021)b | 6.2 |

| Proportion of population above Statutory Pensionable Age receiving a pension (2019)e | 8.5% |

| Active contributors to an old age contributory scheme as a percent of the working age population (2011)f | |

| Male | 16.4% |

| Female | 17.5% |

| Proportion of population covered by at least one social protection benefit (2020)e | 57.4% |

| Proportion of population living below national poverty line (2020)b | 15.9% |

| Proportion of population aged 65+ living below international poverty line (2019)b | 6.5% |

| Mortality rate attributed to cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, or chronic respiratory disease (2019)e | 39.7% |

| Male | 45.1% |

| Female | 33.5% |

| Coverage of essential health services (2019)e,g | 52 |

Vanuatu National Population and Housing Census 2020.

World Bank databank (https://data.worldbank.org/country/vanuatu).

GBD 2016 DALYs and HALE Collaborators. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life-years (DALYs) for 333 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE) for 195 countries and territories, 1990–2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016. Lancet.

Vanuatu Demographic and Health Survey 2013.

Asian Development Bank, 2022: Key Indicators for Asia and the Pacific 2022. Manila.

International Labour Office, 2018: Social protection for older persons: Policy trends and statistics 2017–19.

Universal health coverage service coverage index is calculated based on 14 tracer indicators and presented on a scale from 0 to 100.

Health care in Vanuatu is delivered by the Government through six hospitals, 38 health centres, 104 dispensaries and 243 community-owned aid posts, staffed by volunteer community health workers.22 Support for health service delivery is provided by development partners, nongovernment organizations, faith-based organizations and a small private sector. Available evidence depicts a health system by fragmented care, with little continuity of care between hospital and community-based services.26 Patients living in rural areas, especially in outer islands, face little access to care, higher transport costs, long waiting times for transport and typically have lower incomes.25,26 Older ni-Vanuatu, who are more likely to reside in rural locations16 and experience some form of functional disability19 than the younger population, are likely to be disproportionately affected by these barriers.

Data source and sample

A review of national policies and strategies underpinning Vanuatu's response to population ageing to-date was undertaken, with a focus on: provision of health and social services for older adults; health workforce development; aged care/long-term care; gender; disability; age-friendly environments; financial protection; social security and pensions. Relevant national policy and strategy documents were sourced from the official websites of the Government of Vanuatu, including: the Vanuatu Ministry of Health; Ministry of Justice and Community Services; Ministry of Infrastructure and Public Utilities; and Department of Labour. National policy documents of potential relevance that were not publicly available via internet search were requested from, and sourced by, WHO Vanuatu and Vanuatu Ministry of Health collaborators, who were able to access these through national public archives.

To supplement the policy review findings, semi-structured interviews were completed to explore the circumstances and experiences of older ni-Vanuatu in relation to healthy ageing. Interview participants were recruited through purposive sampling to ensure proportional representations based on age group, sex, area (province), cultural/linguistic criteria, and socio-economic situation. Eligibility criteria for participation included: age 50 years or older, residing in the community, willingness to participate and capable of describing their lived experience. The relatively young average healthy life expectancy in Vanuatu of 58 years (56 years for men),36 the only recent increase in compulsory retirement age from 55 to 60 years for public servants,37 and cultural perceptions of ‘elders’ also suggest a ‘younger’ cut-off age for classifying older persons may be appropriate. As such, we invited perspectives from those aged 50 years and over. We aimed to recruit at least six older adults with primary residence in each of Vanuatu's six provinces (i.e. minimum 36 participants), which we hypothesized to be the minimum sample required to achieve thematic saturation.38

Interview recruitment and conduct was carried out by ni-Vanuatu representatives of a local non-government organization (NGO) with prior experience of community consultation, proficiency in the local language and training in qualitative techniques. The NGO representative provided verbal information about the research to the village chief and sought their permission to undertake interviews with members of their community. Once permission was granted, an invitation to take part in an interview was disseminated to eligible community members by verbal announcement at regular community forums (church meetings, village meetings, women's groups). All participants provided informed written or oral consent prior to data collection. In the case of oral consent, potential participants who were unable to read or write were first read the participant information statement by the interviewer and given the opportunity to ask any questions. Then, on agreeing to participate, the participant's oral consent was captured via audio recording.

A total of 42 interviews were conducted with older adults (18 men and 23 women [missing data, 1]; age range 54–90 years) residing in four of Vanuatu's six provinces: Malampa, Sanma, Shefa and Tafea. Each interview was conducted in the local language of participants' choice (English, Bislama or French). Interview discussions were guided by a semi-structured interview guide (Supplementary File 1) and explored: perceptions and attitudes towards ageing; community and social services for health and social support; attitudes to and experience of COVID-19 (including aspects of vaccination and the specific needs of older adults during the pandemic); use of traditional healers; and current social models for and attitudes towards long term care (defined as “the activities undertaken by others to ensure that people with or at risk of a significant ongoing loss of intrinsic capacity can maintain a level of functional ability consistent with their basic rights, fundamental freedoms and human dignity”34). Interviews were audiotaped and lasted approximately 20 min. Basic demographic details of interview participants were elicited by a short questionnaire. The majority of those interviewed (32/42) lived with family (either a spouse, children, or both) and 24% (10/42) were widowed. A summary of participant demographic details is provided in Table 2.

Table 2.

Demographic characteristics of interview respondents (n = 42).

| Provincea | Participants |

Gender |

Age group (years) |

Living situation |

Marital status |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n) | M | F | 50–59 | 60–69 | 70+ | Alone | Family | Married | Widowed | Single | |

| Malampa | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Sanma | 27 | 10 | 17 | 7 | 7 | 10 | 1 | 22 | 17 | 9 | 1 |

| Shefa | 7 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Tafea | 6 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 0 |

| TOTAL | 42 | 18 | 23 | 8 | 12 | 12 | 2 | 32 | 27 | 10 | 2 |

Missing data: Malampa: age group (1); Sanma: gender (1), age group (3), living situation (4), marital status (1); Shefa: gender (1), age group (5), living situation (4), marital status (3); Tafea: age group (1).

Data collection was undertaken between September and November 2022.

Data analysis

All identified national policy and strategy documents were reviewed in full by one member of the research team (AP). Applying a policy content analysis approach,39 keywords and concepts reflective of each of the five objectives of the WHO Regional Action Plan were systematically identified in each documents and the relevant text excerpts were extracted to pre-defined codes structured according to the sub-components of each objective, using QSR nVivo 12 (QSR International, Burlington, MA, USA) qualitative data management software. To aid identification of the strengths, weaknesses and gaps in the alignment of current policy initiatives with the Regional Action Plan, content was then visually mapped (Supplementary File 2) and areas of potential leverage and requirements for policy-strengthening to more effectively address the Action Plan objectives were identified.

Interview audiotapes were transcribed verbatim and translated into English, and the transcript checked for accuracy by a bi-lingual member of the research team and anonymized by another member. Using QSR nVivo 12 (QSR International, Burlington, MA, USA), transcripts were then separately coded, inductively, by two members of the research team (AP, TG) and codes reviewed, refined and sorted into a single coding framework based on main categories of discussion. Emerging themes were explored by all members of the research team, who worked collaboratively to further refine themes and compare findings by participant group and demographic characteristics.

Thematic findings from the interviews were triangulated with those of the policy review to identify common, contrasting and/or complementary themes.40,41 The qualitative interview data provided important contextual grounding to the desk-based policy analysis and helped to inform potential levers and leverage points for a national response to healthy ageing, grounded in the objectives of the Regional Action Plan.31

Role of the funding source

This project was funded and supported by the World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific. SL and SiL are employees of the World Health Organization and contributed to study design, analysis, interpretation, and writing of the manuscript.

Results

Policy review

A total of 23 government policies, plans or strategies were identified as encompassing issues potentially applicable to the health and social care needs of older persons in Vanuatu (Supplementary File 3). Strengths, limitations and gaps of the current policy landscape as it related to the Regional Action Plan objectives are summarized below. Relevant policy content, mapped to the objectives of the Regional Action Plan, is available in Supplementary File 2.

Policy strengths

We identified main strengths of existing national policy commitments in relation to two of the five objectives of the Regional Acton Plan: Objective 2 (Transforming health systems) and Objective 5 (Strengthening monitoring and surveillance systems). A third objective (Objective 3—Community-based integrated care) was underpinned to some extent by existing policy, though with key omissions in commitments to supporting models of long-term care, including ageing in place.

Two national policy documents—the National Sustainable Development Plan (2016–2030) and the Health Sector Strategy (2021–2030)—made explicit mention of the needs and rights of older persons in their overarching goals or objectives. Both documents were key instruments guiding the nation's policy direction through to 2030. Further, all six Health Sector Strategy goals served to strengthen both national and community health systems to optimize population health, thereby creating a health sector conducive to healthy ageing. Guiding principles of the Health Sector Strategy—universal health coverage, primary health care, equitable and inclusive health, continuum of care, community engagement and multi-sectoral action—were in clear alignment with the Regional Action Plan's Objective 2.

Policy commitments to strengthening research, monitoring and evaluation (Objective 5) were extensive, ranging from ensuring systems to collect, analyse and report disaggregated health data, to enhancing use of research and data for decision making and building health management capacity to evidence-based policies. While not explicitly mentioning programs, services and policies for older adults as a key outcome, broader reference to the application of these commitments to inclusive development efforts for ‘vulnerable groups’ and ‘persons with a disability’ could be leveraged in a more targeted national plan or strategy for healthy ageing.

We found a range of other national policy and strategy documents which indirectly recognized the strategic objectives of the Regional Action Plan. These include the Ministry of Health Workforce Development Plan (2019–2025), Vanuatu Non-Communicable Diseases Policy & Strategic Plan (2021–2030), Clinical Services Plan (2019), and National Disability Inclusive Development Policy (2018–2025). While these did not specifically focus on ageing and older adults, they showed a commitment to strengthening the core health system foundations required to enable healthy ageing (including enabling implementation of many of the Regional Action Plan's recommended actions).

Other key strengths of the Vanuatu policy environment included the use of best-available local evidence to underpin policy commitments, and the presence of implementation plans and monitoring and evaluation plans for several major policy documents (including the National Sustainable Development Plan [2016–2030] and Workforce Development Plan [2019–2025]). The use of evidence suggests decision-making is informed by accurate and meaningful data which may lead to policies that are more relevant and likely to reach their desired outcome. Each of these plans established a clear and pragmatic pathway to meeting policy objectives and defined key implementation partners.

Policy limitations and gaps

Specific policy commitments relating to strengthening understanding of the broader implications of population ageing, the development of a positive culture around ageing, optimizing appropriate models of long-term care, the coordination of health and social services at both patient and community level, and technological and social innovation to promote healthy ageing (six key objectives of the Regional Action Plan) were largely absent.

Further, while there was a range of national policy and strategy documents with objectives closely aligned to the Regional Action Plan's other strategic objectives, none of the Action Plan's recommended country actions were comprehensively addressed within the existing national policy framework. Where recommended actions were partially reflected in policy, the policy commitment was relatively broad, simply referring to ‘vulnerable groups’ (assuming one of which may be older adults). Existing policies lacked mention of the specific health needs of older adults, their access to care, and provision (or gaps) in appropriate health services. The absence of mention of older persons contrasts with explicit policy commitments for other population groups: for example, the national Health Sector Strategy (2021–2030) placed focus on strengthening “Family Health to improve health outcomes, especially for those most vulnerable, such as women, children and young people”, omitting any mention of older persons as vulnerable family members. The Health Sector Strategy's Objective 1.1 sets out to ‘Ensure people with disability are recognised and supported by the health system” and Objective 2.8 to “Improve quality, range and accessibility of targeted health messaging and services for adolescents and young people…’, yet older adults remained largely invisible.

While there were well-defined implementation and monitoring plans for several major policy documents, none of the monitoring indicators focused on the health and wellbeing of the older population. This lack of monitoring was particularly evident in the Health Sector Strategy's expanded national ‘Health Report Card’, which omitted any performance indicator specifically tailored to older adults.

Semi-structured interviews

Six overarching themes emerged from the accounts of older adults in Vanuatu regarding their experiences with ageing. These are reported here and summarized in Table 3 with reference to their alignment with implementation of the Regional Action Plan.

Table 3.

Key themes emerging from interviews with older ni-Vanuatu as contextual implementation levers for the WHO Regional Action Plan on Healthy Ageing in the Western Pacific (2020).

| Theme | WHO regional action plan alignment | Implementation leverage point |

|---|---|---|

| Older persons are financially insecure | Objective 1.2: Transform policies across sectors to ensure that policies are age-friendly |

|

| Perceived physical and mental capabilities influence participation |

Objective 1.3: Advocacy to prevent ageism and create a positive culture around ageing Objective 2: Transforming health systems to address each individual's lifelong health needs by providing necessary health and non-health services in a coordinated way |

|

| Family and community attitudes towards older persons impact wellbeing | Objective 1.3: Advocacy to prevent ageism and create a positive culture around ageing |

|

| Community support for older persons is limited |

Objective 1.2: Transform policies across sectors to ensure that policies are age-friendly Objective 3: Providing community-based integrated care for older adults, specifically:

|

|

| COVID-19 challenged health and social vulnerabilities |

Objective 2.1: Curative services & care continuity during health emergencies Objective 2.3: Social and welfare services Objective 3.1: Health care & vaccine-preventable conditions Objective 3.4: Coordination (community level) |

|

| Faith and religion provide reassurance and direction |

Objective 3: Providing community-based integrated care for older adults, specifically:

|

|

World Health Organization. (2007). Global age-friendly cities: a guide. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43755.

World Health Organization. (2019). Integrated care for older people (ICOPE): Guidance for person-centred assessment and pathways in primary care. World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/iris/rest/bitstreams/1088824/retrieve.

Older persons are financially insecure

Respondents (n = 17/42) reported relying on family members (often children) for both financial support and assistance with activities of daily living, including food preparation and mobility. Many expressed concerns about this reliance, due to either: 1) the pressure it placed on family members who were willing to provide such support; or 2) the absence of support for older adults with less-willing family members or without family living nearby. Seventeen older adults also pursued income independently through the sale of craftwork and food items at their local markets, though some noted that health and mobility issues impacted their ability to do so on a regular basis. A small number of respondents (n = 4) stated they had no income at all. The following quotes illustrate how older adults were dependent on friends and relatives to support their basic needs. When relatives were absent, some participants lost access to resources altogether:

‘My friends and family support me. However, if no one comes by, I can go hungry at lunch, but it’s ok, I am already old.’

[F, Sanma, age unknown]

‘My children support me but when they go away from home it’s just me.’

[F, 90, Sanma]

‘In the past I earn my income from selling things at the market but now that I am sick, I can no longer do that. My sons would support me financially.’

[F, 64, Sanma]

Perceived physical and mental capabilities influence participation

One of the strongest themes emerging from discussions focused on participation and agency, encompassing both a sense of loss of these facets in older age and, for many, a desire to continue to provide an active contribution to society. Several respondents expressed a sense of frustration that although they wanted to contribute to income generation, household responsibilities and other subsistence activities in the older age, they felt a loss of power and strength that prevented them from achieving their desired level of contribution.

‘At a younger age, you can do everything you want to do. At this older age, there are some things I cannot do. My grandchildren especially get tired of doing what I ask them to do.’

[F, 62, Sanma]

‘When I was younger, I could do everything. But for now, I feel crippled as I cannot do much for myself.’

[F, 64, Sanma]

‘I have grown weak and cannot perform normal chores such as gardening etc.’

[F, 70, Sanma]

Family and community attitudes towards older persons impact wellbeing

Older adults described how interactions with a family or community member—whether positive or negative—would influence their self-esteem and sense of self-worth. Some respondents indicated a loss of respect from both family and community as they became older.

‘When I was younger, I loved to go gardening and help others. However now that I am older, a lot of people neglect me and will not help me. I wish I was younger so I can help those like myself.’

[M, Sanma, age unknown]

‘It is hard work looking after my grandkids and as I am getting older, I don’t feel ok looking after them. I now don’t feel ok as they gave me some ill-treatment this morning.’

[F, 67, Sanma]

Others felt that they were treated with greater kindness and regard.

‘They treat me well with respect and I am satisfied with how they treat me.’

[M, 68, Tafea]

There was a widely shared concern that younger people were no longer committed to the legacy established by previous generations.

‘I would appreciate more if young people follow the good steps which we have built in our communities, like finding decent job or work, going to church, achieving their goal.’

[M, 71, Malampa]

Community support for older persons is limited

Respondents reported a lack of community initiatives designed to support the health and wellbeing of older adults. In one province (Tafea) there was community support for cleaning and maintaining the gardens of older residents; one respondent also reported community help in funding their transport to health services or sourcing medication.

‘The community helps clean our garden and they can assist us with kastom [cultural traditions] and church work.’

[M, 60, Tafea]

Thirteen respondents, however, stated that the community did not help them at all and called for stronger engagement from the village chief and younger community leaders in listening to older persons and addressing their needs.

‘Young leaders should listen and have respect to elderly, so they get examples from them to lead the community in the future.’

[M, Malampa, age unknown]

COVID-19 challenged health and social vulnerabilities

Many respondents experienced social isolation during the COVID-19 pandemic. This isolation was strongly linked to their inability to attend church gatherings and prayer groups during that time, which serve as the regular means of socialization for many older ni-Vanuatu. Feelings of social isolation were more commonly reported by those older adults living alone. Older adults also felt that their basic needs were left unsupported during the height of the pandemic, particularly in relation to medications, food and transport. Food shortages were frequently reported by respondents, who could no longer access local shops and supermarkets due to public health orders.

‘Main challenge is that you have to isolate yourself and cannot visit other family members. I find that very hard.’

[M, Tafea, age unknown]

‘We stay by yourself, isolated from other relatives.’

[M, 59, Tafea]

‘I can't walk to Lakatoro (main town) even nearby shop to buy food because of lockdown.’

[M, 87, Malampa]

When exploring attitudes towards and experience with the COVID-19 vaccination, more than 60% of respondents had refused the vaccine despite its availability. Reasons given included fear of illness linked to vaccination (fuelled by rumours and misinformation) and a perception that vaccination was redundant because of their older age.

‘There were a lot of rumours, and I was afraid to get vaccinated and information was not clear… My view: we are old and we do not need any vaccine as our blood is already weak. This medicine can shorten our life span.’

[M, Tafea, 60]

Faith and religion provide reassurance and direction

Respondents (n = 8) mentioned ‘church’, ‘religion’, ‘God’, or ‘prayer’ as some of the key factors from which they derive strength and joy in older age. For many, church and prayer also provided opportunity for social contact; the loss of these social opportunities was felt strongly by several respondents during the COVID-19 lockdown.

‘I get my income through my prayer. I Pray to God if I need money or food, God answers my prayers.’

[F, 81, Sanma]

‘I have this sickness now. My mind is all set on God and nothing else.’

[F, 61, Sanma]

‘…not worried at all as many times we resort to go to church and just pray.’

[F, 65, Shefa]

‘There are some people who treat me badly, but I tend to forgive them despite the situation. The Lord said to be of good character so, despite their ill-treatment, I know that only God holds my life.’

[F, 54, Sanma]

Discussion

This study provides the first comprehensive assessment of the policy landscape underpinning healthy ageing in Vanuatu. First-hand experiences of older ni-Vanuatu provided additional context to inform potential levers for a national response. While several key national policies and strategies exhibited indirect commitments to creating an environment conducive to healthy ageing, policy commitments and monitoring indicators explicit to the health and wellbeing of older adults were lacking. Older persons reported numerous obstacles to healthy ageing, including financial insecurity, ageism, social isolation, physical and psychological barriers to participation, and an absence of community-based services and support. Faith and religion were frequently cited as primary sources of reassurance and direction for older adults, in addition to being agents of socialization.

Despite the limited national focus on ageing to-date, the national policy framework included older ni-Vanuatu in its broader vision and provided a strong leverage point from which to build a national response to healthy ageing. This commitment was reflected in Society Goal 4 of the National Sustainable Development Plan (2016–2030): “An inclusive society which upholds human dignity and where the rights of all ni-Vanuatu including women, youth, the elderly and vulnerable groups are supported, protected and promoted in our legislation and institutions.” Embedding a national action plan on healthy ageing within this vision and emphasizing alignment of objectives and guiding principles with those of existing sectoral policies (e.g., health, environment, climate change), may facilitate an effective, integrated and multisectoral approach to optimizing opportunities for healthy ageing in Vanuatu.

The existing national policy landscape exhibited additional strengths in not only being evidence-based but incorporating well-defined monitoring and implementation plans. There were, however, an absence of monitoring indicators focusing on the health and wellbeing of the older population, resulting in limited data to inform future actions to improve the wellbeing of older adults. This “data gap” on older persons has been highlighted globally as a key barrier to informed and successful public policy that is inclusive of the needs of older adults.42,43 The addition of select indicators to existing policy monitoring frameworks that inform the specific needs and health concerns of older ni-Vanuatu would enhance the impact of national policy on older persons’ wellbeing and delineate areas to include in a dedicated national response to healthy ageing. These indicators could include, for example: demographic health data; health service accessibility; data on social support needs; data on income source, adequacy and predictability; data on food security; and data relating to unpaid work and care.42,44,45 Appropriate disaggregation of data (by age group, sex and (where available) gender, and other key sociodemographic variables including living arrangements, education, employment, income and location) is also essential for informing the design and implementation of equitable healthy ageing policies and programs.46

The absence of ageing related policies or specific policy objectives in Vanuatu reflects the concerns of invisibility and social exclusion raised by older persons in our qualitative interviews. Indeed, the Health Sector Strategy's expanded national ‘Health Report Card’, omitted any performance indicator specifically tailored to older adults. In line with this omission, older ni-Vanuatu commonly reported feeling ignored by the community, financially insecure, heavily reliant on their children for income and food and dependent on unpredictable income through the sale of goods at local markets. With no state-funded universal age pension, the majority of older ni-Vanuatu rely on informal arrangements involving extended families and limited NGO-delivered social assistance activities.27,28 Such circumstances have been linked to significant physical and mental health implications for older adults.47

These findings provide several contextually grounded leverage points which should be harnessed in the development of effective and sustainable policy and implementation initiatives to enhance healthy ageing (see ‘Implementation leverage point’ column in Table 3). For instance, there is a critical need for initiatives to safeguard the financial security of older adults and unpaid caregivers, who often sacrifice income-earning activities to take on this role. More gender-sensitive analysis is also required to explore issues of inequality on women's economic security. These initiatives may have greatest impact by harnessing the important role of family and kindship networks in older person care. Initiatives specifically targeting community and caregiver awareness and empowerment, such as educational interventions and intergenerational contact, may serve to address other key concerns expressed by interview participants, including a need to improve community perceptions of older persons and combat ageism.48

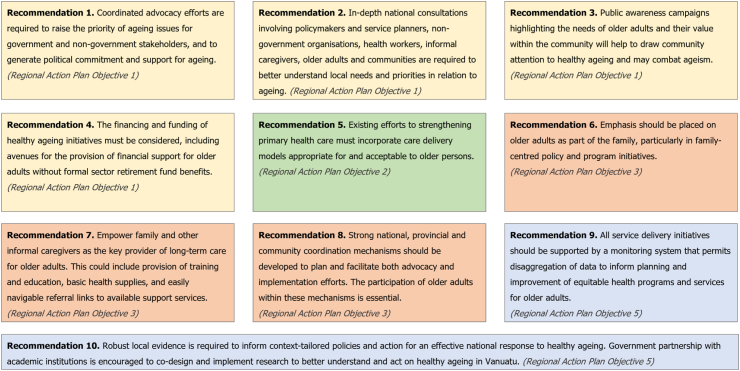

Based on the findings of this study, we propose ten preliminary steps towards developing a national response to healthy ageing in Vanuatu (Fig. 2). Alignment of recommendations with the strategic objectives of the WHO Regional Action Plan for Healthy Ageing in the Western Pacific (2021–2025) is highlighted. Study findings indicate the need for policymakers and other national healthy ageing stakeholders to focus preliminary strategic efforts on select components of the Regional Action Plan: evidence generation, advocacy and awareness, financing, community engagement and coordination, and family-centred empowerment. We recognize that not all objectives of the Regional Action Plan are addressed in these preliminary steps and encourage a pragmatic approach to the development of an effective and sustainable national response, tailored to context. For example, aspects of innovation and health system reform for healthy ageing—which require an evidence base, political commitment, policy direction and appropriate funding models—may constitute a second phase of national planning. To ensure acceptability and sustainability of future healthy ageing initiatives (cf. ‘Implementation leverage point’ column in Table 3), it is vital that these leverage existing strengths of traditional community values and the prevailing role of faith and religion in the lives of older ni-Vanuatu.

Fig. 2.

Proposed preliminary steps towards developing a national response to healthy ageing in Vanuatu and their alignment with strategic objectives of the World Health Organization Regional Action Plan for Healthy Ageing in the Western Pacific.31

Limitations

The findings reported here are limited by the breadth and quality of publicly available evidence on healthy ageing in Vanuatu. The dearth of prior research in this area prevents validation of our findings with alternative sources and reinforces the significance of this founding study. Insights from interviews were not as rich as hoped due to a relatively small number of older ni-Vanuatu participants, limited probing and superficial exploration of responses by interviewers, and data collection predominantly conducted in one province (Sanma, 30/45 interviews). Further, two of the more geographically isolated provinces (Torba and Penama) remained unrepresented in our interview sample due to resource and timeline limitations impacting research team travel for data collection. This restricted geographic focus may limit transferability of our findings to other settings. Yet, considering that ageing has received limited policy attention across the Pacific, it is likely that many of the findings are broadly reflective of the ageing experience elsewhere in the Pacific Islands region.5 The authors acknowledge the potential influence of various sources of bias on our qualitative findings and took steps to prevent these during the research process. To mitigate interviewer bias, a pre-defined topic guide was used by all interviewers and all interviews were audio recorded which allowed for monitoring of any researcher influence on participants’ responses. Additionally, the research team—comprising both international and ni-Vanuatu members—consulted regularly during the analysis of interview data to mitigate any cultural bias in the interpretation of data and identification of emerging themes.

Additional in-depth national consultation, involving non-government organizations, health workers, policymakers and service planners, will be required to better understand local needs and priorities in relation to ageing. The authors recommend that such consultations aim to explore and map current programs, services and resources for older adults; understand the political economy of ageing in Vanuatu and cultural acceptance of ageing policy; assess the social context of support for older adults in greater depth, including the concept of “family” and where extended kinship systems and networks are at play; and examine pathways for multi-sectoral coordination of a national healthy ageing response. Further, building on the finding of faith and religion being an important source of strength and direction for older ni-Vanuatu, the role of these concepts and structures in healing more broadly and the impact of this on a person's experience of ageing warrants further exploration. The research also did not collect data relating to identity and belonging beyond gender, age, living situation, marital status, and province of origin. Additional variables should be collected in the future to enable a better understanding of variations of experiences of ageing across the population. Further in-depth community consultation would also be beneficial to assess in detail the individual needs of older ni-Vanuatu (representing the spectrum of functional ability) and informal caregivers, barriers to accessing current health and social care services, and preferences for models of aged care appropriate to the context.

While our research details a set of preliminary priorities for health and social policy efforts to optimize healthy ageing specifically within the Vanuatu context, these insights likely hold relevance to other Pacific Island nations who are yet to develop a national policy response to population ageing. Indeed, similar policy priorities related to the provision of integrated, community-based health and social care and a critical need for initiatives that empower family caregivers of older adults were recently identified in Fiji.6,49 The requirement for aged care workforce training and strengthened data collection for evidence-based planning is also echoed in the single available review of health system implications of population ageing across Pacific Island countries.5 Importantly, this study lays the foundation for additional research on healthy ageing in Vanuatu (and other Pacific Island nations) to ensure a strong evidence base on which to develop contextually relevant and community-centred policy, program and service initiatives. Future research domains would also make valuable attempts to disaggregate data into a more extensive and granular understanding of needs across the ageing population according to gender, belonging to pertinent sub-groups, place of residence, migration trajectories, urban/rural settings, and other relevant variations impacting identity.

Conclusion

This study provides unique evidence of the policy and societal context underpinning opportunities for healthy ageing in Vanuatu. The nation's once young population is now ageing at a rapid pace, making the next decade a critical time to produce, and respond to, evidence which informs policies and actions that will optimize the health and wellbeing of older adults. The findings reported here highlight significant gaps in the degree to which Vanuatu's current healthy ageing policy, programs and services address objectives of the WHO Regional Action Plan on Healthy Ageing in the Western Pacific. While acknowledging the limitations of the existing national policy landscape, this research also shows how current policy is compatible with the development and implementation of a more extensive response to population ageing both through its inclusion of concerns for older adults, and the existence of well-defined monitoring and implementation plans. Specifically, our findings highlighted the need for policymakers and stakeholders to focus preliminary strategic health and social policy efforts on select components of the Regional Action Plan: evidence generation, advocacy/awareness, financing, community engagement and coordination, and family-centred empowerment. Our findings also emphasized the importance of traditional community values and the prevailing role of faith and religion in the lives of older ni-Vanuatu, and it is recommended that health and social policy initiatives leverage these existing strengths to ensure acceptability and sustainability.

Contributors

Conceptualization: AP, SeL, SiL, JS, MA, TB; Data collection: AP, TG, LP; Data analysis and interpretation: AP, TG, MA, TB, SeL, CB; Original draft of the manuscript: AP, TG, SeL; Review and editing of the manuscript: All authors.

Data sharing statement

Policy data were obtained from publicly available sources. Further data that supports the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Editor note

The Lancet Group takes a neutral position with respect to territorial claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Declaration of interests

None declared.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the valuable support offered by volunteers at the Vanuatu Red Cross Society, colleagues at WHO Country Liaison Office for Vanuatu, and Dr Fabrizio D'Esposito, Consultant for WHO, at different stages of this research project. This project was funded and supported by the World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for the Western Pacific (WPRO). Outcomes reported here reflect the deliberations of authors and research partners. AP was supported by an Australian National Health and Medical Research Council Early Career Fellowship. TG was supported by a University Postgraduate Award from the University of New South Wales.

Footnotes

This is an Open Access article published under the CC BY NC ND 3.0 IGO license which permits users to download and share the article for non-commercial purposes, so long as the article is reproduced in the whole without changes, and provided the original source is properly cited. This article shall not be used or reproduced in association with the promotion of commercial products, services or any entity. There should be no suggestion that WHO endorses any specific organisation, products or services. The use of the WHO logo is not permitted.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lanwpc.2024.101178.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

References

- 1.United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs Population Division . 2017. World population prospects: the 2017 revision. New York. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Suhrcke M., Fumagalli E., Hancock R. Is there a wealth dividend of aging societies? Public Health Rev. 2010;32:377–400. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bristol N. Vol. 38. Center for Strategic and International Studies; Washington DC: 2014. pp. 152–160. (Global action toward universal health coverage). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barber S., Rosenberg M. Aging and universal health coverage: implications for the Asia pacific region. Health Syst Reform. 2017;3:154–158. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2017.1348320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Anderson I., Irava W. The implications of aging on the health systems of the Pacific Islands: challenges and opportunities. Health Syst Reform. 2017;3:191–202. doi: 10.1080/23288604.2017.1342179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dodd R., Shanthosh J., Lung T., et al. Gender, health and ageing in Fiji: a mixed methods analysis. Int J Equity Health. 2021;20:205. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01529-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Teerawichitchainan B., Knodel J. 2015. Data mapping on ageing in Asia and the pacific: analytical report. East Asia and pacific regional office HelpAge international. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Keating N. A research framework for the united nations decade of healthy ageing (2021–2030) Eur J Ageing. 2022;19:775–787. doi: 10.1007/s10433-021-00679-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2017. Global strategy and action plan on ageing and health. [Google Scholar]

- 10.World Health Organization UN decade of health ageing. 2021. https://www.who.int/ageing/decade-of-healthy-ageing Available from:

- 11.World Bank . World Bank; Washington, DC: 2016. Live long and prosper: aging in east Asia and pacific. [Google Scholar]

- 12.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva: 2011. Global status report on noncommunicable diseases 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 13.UNFPA Pacific Sub-Regional Office . UNFPA Sub-Regional Office; Suva, Fiji: 2014. Population ageing in the Pacific Islands: a situation analysis. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lin S., Tukana I., Linhart C., et al. Diabetes and obesity trends in Fiji over 30 years. J Diabetes. 2016;8:533–543. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spratt J. 2019. Palliative care in the pacific: initial research. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vanuatu National Statistics Office . 2020. National population and housing census: basic tables report volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- 17.United Nations Population Fund Pacific Sub-Regional Office . United Nations Population Fund; Suva, Fiji: 2014. Population and development profiles: pacific island countries. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chang A.Y., Skirbekk V.F., Tyrovolas S., Kassebaum N.J., Dieleman J.L. Measuring population ageing: an analysis of the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet Public Health. 2019;4:e159–e167. doi: 10.1016/S2468-2667(19)30019-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vanuatu National Statistics Office and Secretariat of the Pacific Community . 2014. Vanuatu demographic and health survey, 2013: final report. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ibell C., Sheridan S.A., Hill P.S., Tasserei J., Maleb M., Rory J. The individual, the government and the global community: sharing responsibility for health post-2015 in Vanuatu, a small island developing state. Int J Equity Health. 2015;14:102. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0244-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Elliott L., Taylor J. Medical pluralism, sorcery belief and health seeking in Vanuatu: a quantitative and descriptive study. Health Promot Int. 2021;36:722–730. doi: 10.1093/heapro/daaa079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.World Bank . International Bank for Reconstruction and Development/The World Bank; Washington, DC: 2018. Vanuatu health financing system assessment: spend better. [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Health Organization . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2013. Human resources for health country profiles: Republic of Vanuatu. [Google Scholar]

- 24.World Health Organization Western Pacific Region . WHO; Philippines: 2017. Vanuatu-WHO; country cooperation strategy 2018–2022. contract No.: WPRO/2017/DPM/025. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bunkley N., Bissett I., Buka M., et al. A household survey to evaluate access to surgical care in Vanuatu. World J Surg. 2020;44:3237–3244. doi: 10.1007/s00268-020-05608-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ofanoa M., Aitip B., Ram K., et al. A qualitative study of patient perspectives of diabetes and diabetic retinopathy services in Vanuatu. Health Promot J Austr. 2022;33:289–296. doi: 10.1002/hpja.484. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alatoa H. 2012. ADB technical assistance consultant's report: republic of Vanuatu: updating and improving the social protection index. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jolly M.L.,H., Lepani K., Naupa A., Rooney M. UN Women; 2015. Falling through the net? Gender and social protection in the Pacific. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sepúlveda-Loyola W., Rodríguez-Sánchez I., Pérez-Rodríguez P., et al. Impact of social isolation due to COVID-19 on health in older people: mental and physical effects and recommendations. J Nutr Health Aging. 2020;25:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s12603-020-1500-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.United Nations General Assembly. (2020) 75/131 . 2020. United nations decade of healthy ageing (2021–2030). Resolution adopted by the general assembly on 14 December. [Google Scholar]

- 31.World Health Organization . World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific; Manila: 2020. Regional action plan on healthy ageing in the western pacific. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Leyland A., Groenewegen P. Health in context. Springer; Cham (CH): 2020. Multilevel modelling for public health and health services research: health in context. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Raub W., Buskens V., Van Assen M. Micro-macro links and microfoundations in sociology. J Math Sociol. 2011;35:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- 34.World Health Organization . 2015. World report on ageing and health. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Government of Vanuatu . 2023. About Vanuatu.https://www.gov.vu/index.php/about/about-vanuatu Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 36.Global health estimates. 2022. https://www.who.int/data/gho/data/themes/mortality-and-global-health-estimates/ghe-life-expectancy-and-healthy-life-expectancy Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 37.Government of Vanuatu . 2020. Employment act [CAP. 160] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Urquhart C. 2013. Grounded theory for qualitative research: a practical guide. 55 city road.https://methods.sagepub.com/book/grounded-theory-for-qualitative-research London. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hall D.M., Steiner R. Policy content analysis: qualitative method for analyzing sub-national insect pollinator legislation. MethodsX. 2020;7 doi: 10.1016/j.mex.2020.100787. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.O'Cathain A., Murphy E., Nicholl J. Three techniques for integrating data in mixed methods studies. BMJ. 2010;341:c4587. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c4587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tariq S., Woodman J. Using mixed methods in health research. JRSM Short Rep. 2013;4 doi: 10.1177/2042533313479197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gorman MM A., Albone R., Knox-Vydmanov C. HelpAge International; London: 2017. How data systems leave older people behind. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Amuthavalli Thiyagarajan J., Mikton C., Harwood R.H., et al. The UN decade of healthy ageing: strengthening measurement for monitoring health and wellbeing of older people. Age Ageing. 2022;51 doi: 10.1093/ageing/afac147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grube M.M., Möhler R., Fuchs J., Gaertner B., Scheidt-Nave C. Indicator-based public health monitoring in old age in OECD member countries: a scoping review. BMC Public Health. 2019;19:1068. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7287-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Global AgeWatch . HelpAge International; London: 2014. Older people count: making data fit for purpose. [Google Scholar]

- 46.Diaz T., Strong K.L., Cao B., et al. A call for standardised age-disaggregated health data. Lancet Healthy Longev. 2021;2:e436–e443. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(21)00115-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Kim S., Subramanian S.V. Income volatility and depressive symptoms among elderly Koreans. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2019;16 doi: 10.3390/ijerph16193580. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ayalon L., Roy S. Combatting ageism in the western pacific region. Lancet Reg Health Western Pacific. 2022;25 doi: 10.1016/j.lanwpc.2022.100593. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Palagyi A., Rafai E., Zwi A., et al. The George Institute for Global Health; Sydney, Australia: 2022. Healthy ageing Fiji: promoting evidence-based policies, programs and services for ageing and health in Fiji.https://cdn.georgeinstitute.org/sites/default/files/documents/Fiji-population-ageing-report-apr-2022_0.pdf Available from: [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.