Abstract

Flavobacterium columnare and F. psychrophilum are major fish pathogens that cause diseases that may require antimicrobial therapy. Choice of appropriate treatment is dependent upon determining the antimicrobial susceptibility of isolates. Therefore we optimized methods for broth microdilution testing of F. columnare and F. psychrophilum to facilitate standardizing an antimicrobial susceptibility test. We developed adaptations to make reproducible broth inoculums and confirmed the proper incubation time and media composition. We tested the stability of potential quality-control bacteria and compared test results between different operators. Log phase occurred at 48 h for F. columnare and 72–96 h for F. psychrophilum, confirming the test should be incubated at 28°C for approximately 48 h and at 18°C for approximately 96 h, respectively. The most consistent susceptibility results were achieved with plain, 4-g/L, dilute Mueller–Hinton broth supplemented with dilute calcium and magnesium. Supplementing the broth with horse serum did not improve growth. The quality-control strains, Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida ATCC 33658, yielded stable minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) against all seven antimicrobials tested after 30 passes at 28°C and 15 passes at 18°C. In comparison tests, most MICs of the isolates agreed 100% within one drug dilution for ampicillin, florfenicol, and oxytetracycline. The agreement was lower with the ormetoprim–sulfdimethoxine combination, but there was at least 75% agreement for all but one isolate. These experiments have provided methods to help standardize antimicrobial susceptibility testing of these nutritionally fastidious aquatic bacteria.

Major advances have been made in the development of standard laboratory methods to determine the antimicrobial susceptibility of bacterial pathogens of fish. Miller et al. (2003, 2005) conducted two multilaboratory standardization trials to determine quality control (QC) parameters for standard disk-diffusion and broth-dilution testing, at 22°C and 28°C, of nonfastidious bacteria isolated from aquatic animals. Results of these trials were used to draft two Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute (CLSI) guidelines (M42-A and M49-A). These guidelines provided reference methods, as well as QC parameters for testing some antimicrobials used in aquatic animal medicine.

This paper describes similar broth microdilution methods optimized for testing Flavobacterium columnare and F. psychrophilum. These experiments were done to facilitate a recent multilaboratory standardization trial that established QC parameters at the test conditions described in Gieseker et al. (2012). Recently, the CLSI updated guideline VET-04 (formerly M49-A) to include methods specific for broth dilution testing of these fastidious gliding bacteria based in part on the experiments described in this paper (CLSI 2014). Both F. columnare and F. psychrophilum are major pathogens of farmed fish that cause diseases, which may require antimicrobial therapy based on susceptibility test results. Therefore, reliable susceptibility testing methods were needed to help effectively guide clinical therapy and to monitor for changes in antimicrobial susceptibility patterns.

The distinctive growth features of fastidious bacteria present challenges that dictate which in vitro susceptibility testing method (disk diffusion, broth dilution, or agar dilution) should be used. Although agar dilution has been used to test F. psychrophilum (Bruun et al. 2000; Schmidt et al. 2000; Michel et al. 2003), some F. columnare isolates glide overtop adjacent isolates placed on the agar in distinct spots. In addition, the gliding rhizoid growth of F. columnare can disrupt Kirby–Bauer disk diffusion by distorting the inhibitory zones (Farmer 2004). Therefore, we decided to focus on the broth dilution as this technique was well suited for testing both Flavobacteria species since both grow well in liquid media. Past research has studied the antimicrobial susceptibility of both bacteria using the broth microdilution technique; however, the test conditions varied between studies, and/or quality control was either not used or not correctly applied since quality control parameters did not exist (Rangdale et al. 1997; Darwish et al. 2008; Del Cerro et al. 2010; Hesami et al. 2010; Declercq et al. 2013).

The M49-A guideline suggests both diluting (3 g media/L broth) and supplementing (5% horse or fetal calf serum) Mueller–Hinton broth (MHB) for broth dilution testing of fish pathogenic Flavobacteria spp. (CLSI 2006b). This recommendation was based on the work of Hawke and Thune (1992). However, when we began this research in 2009, we focused our efforts on the most recent research that determined plain MHB diluted to 4 g/L was better for broth microdilution testing of F. columnare and that calcium and magnesium cations, typically added to MHB for broth dilution susceptibility testing, may not be needed (Farmer 2004; Darwish et al. 2008). Calcium and magnesium cations are usually added to MHB since they improve the growth of bacteria to better estimate the in vivo activity of antimicrobials (D’Amato et al. 1975; Nanavaty et al. 1998). Declercq et al. (2013) recently used cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton broth (CAMHB) diluted to 3 g/L to successfully test F. columnare with the broth microdilution technique (CLSI 2006b). In our preliminary testing, F. psychrophilum also grew well in plain CAMHB diluted to our target level of 4 g/L (authors’ unpublished data). Our tests here provide further information on whether serum and/or cation supplements could improve the consistency of the broth microdilution tests.

The low temperature requirement of F. psychrophilum presented another challenge since selected QC strains must also grow under the same test conditions. Flavobacterium psychrophilum grows well at 15–20°C with relatively fast generation times (Pacha 1968; Holt et al. 1989). This present study shows how we determined that the two QC strains used for susceptibility testing of nonfastidious aquatic bacteria (CLSI 2006a, 2006b), Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida ATCC 33658, had the stability in their antimicrobial susceptibility to function as QC organisms at the incubation conditions needed for F. columnare and F. psychrophilum. Using existing QC strains kept us from having to develop new QC strains for the standardization trial conducted by Gieseker et al. (2012).

To help develop a standard broth microdilution test for F. columnare and F. psychrophilum, we adapted an alternative method of preparing cell suspensions and determining the optimized incubation times and required media supplements. Additionally, we tested the results for the existing aquatic QC strains under the modified conditions and performed an intralaboratory trial to compare test results among four separate operators to determine whether our method would provide similar results among different users.

METHODS

Bacterial isolates and antimicrobials.—

The 11 F. columnare and 13 F. psychrophilum isolates used in the following experiments are listed in Table 1. All of the isolates were obtained from diseased fish and were donated from laboratories in the USA, France, The Netherlands, Australia, and Chile or bought from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC). The identity of the isolates was confirmed with two species-specific PCR methods (Toyama et al. 1994; Darwish et al. 2004). Two QC strains for standardized susceptibility testing of the nonfastidious aquatic bacteria, E. coli ATCC 25922 and A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida ATCC 33658, were used in all experiments where antimicrobial susceptibility was tested with broth microdilution plates prepared in the laboratory.

TABLE 1.

Flavobacterium columnare and F. psychrophilum isolates used to develop broth microdilution antimicrobial susceptibility testing methods. MSU CVM = Mississippi State University, College of Veterinary Medicine Aquatic Diagnostic Laboratory.

| MSU CVM isolate number | Original isolate number | Host | Year isolated | Country of origin | Source | Serum supplementation | Inoculum volume in test broth | Cation supplementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavobacterium columnare | ||||||||

| 22650 | 503–435 | Channel Catfish Ictalurus punctatus | 2003 | USA | MSU CVM | + | + | + |

| 22655 | 503–517 | Channel Catfish | 2003 | USA | MSU CVM | + | + | |

| 22683 | 94–060 | Channel Catfish | 1994 | USA | John Hawkeb | + | + | + |

| 33677 | 94–082 | Channel Catfish | 1994 | USA | John Hawke | + | + | |

| 33970 | ATCC 49512 | Brown Trout Salmo trutta | 1987 | France | ATCC | + | + | + |

| 33971 | ATCC 49513 | Black Bullhead Ameiurus melas | 1987 | France | ATCC | + | + | |

| 36413 | CVI unknown | Unknown | 1991 | The Netherlands | Olga Haenenc | + | + | |

| 36417 | CVI 04017018 | Koia | 2004 | The Netherlands | Olga Haenen | + | + | + |

| 36422 | ALG 92–491-C | Channel Catfish | 1992 | USA | Joseph Newtond | + | + | + |

| 36434 | JIP 07/02 | Koi | 2002 | France | Jean-Francois Bernardete | + | ||

| 36445 | Not provided | Koi | NA | USA | Hui-Min Hsuf | + | + | |

| Flavobacterium psychrophilum | ||||||||

| 22645 | ATCC 49418T | Coho Salmon Oncorhynchus kisutch | NA | USA | ATCC | + | + | + |

| 36391 | FLPS 70 | Coho Salmon | 1981 | USA | Douglas Callg | |||

| 36393 | FLPS 79 | Coho Salmon | 1990 | USA | Douglas Call | + | + | |

| 36394 | FLPS 80 | Rainbow Trout O. mykiss | 1990 | USA | Douglas Call | + | + | |

| 36395 | FLPS 85 | Rainbow Trout | 1985 | USA | Douglas Call | + | + | + |

| 36396 | FLPS 96 | Ayu Plecoglossus altivelis altivelis | 1988 | Japan | Douglas Call | + | ||

| 36400 | FLPS 69 | Coho Salmon | 1981 | USA | Douglas Call | + | + | + |

| 36403 | FLPS 74 | Coho Salmon | 1989 | USA | Douglas Call | |||

| 36408 | FLPS 99 | Coho Salmon | 1991 | USA | Douglas Call | + | + | |

| 36410 | AU0205 | Atlantic Salmon Salmo salar | 2006 | Chile | Ruben Avendaño-Herrerah | + | + | + |

| 36411 | AU2706 | Rainbow Trout | 2006 | Chile | Ruben Avendaño-Herrera | + | + | |

| 36429 | LVDI 5/I | Common Carp | 1992 | France | Jean-Francois Bernardet | + | + | + |

| 36430 | LVDJ XP189 | Tench Tinca tinca | 1992 | France | Jean-Francois Bernardet | + | + | |

A variant of Common Carp Cyprinus carpio.

Louisiana State University, School of Veterinary Medicine Aquatic Diagnostic Laboratory.

Wageningen University and Research Centre, Central Veterinary Institute.

Auburn University, College of Veterinary Medicine.

Institut National de la Recherche Agronomique, Unite de Virologie et Immunologie Moleculaires.

University of Wisconsin–Madison, Veterinary Diagnostic Laboratory.

Washington State University, College of Veterinary Medicine Animal Disease Diagnostic Laboratory.

Universidad Andres Bello Interdisciplinary Center for Aquaculture Research.

The florfenicol (FFN) and oxytetracycline (OTC) antimicrobials used to test the effect of cations on susceptibility were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, Missouri) and MP Biomedicals (Santa Ana, California), respectively. All antimicrobials, except ormetoprim–sulfadimethoxine, used for stability testing of the potential quality control strains and for the intralaboratory testing trial were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Stock concentrations of ormetoprim (1,000 μg/mL) and sulfadimethoxine (1,520 μg/mL) were purchased from ThermoFisher Scientific, Trek Diagnostic Systems (Cleveland, Ohio).

Effect of horse serum supplementation and incubation time on growth.—

Spread-plate enumerations were used to evaluate F. columnare and F. psychrophilum growth in CAMHB diluted to 4 g/L with or without 5% horse serum (Donor Equine Serum, Hyclone Laboratories, Logan, Utah). The CAMHB diluted to 4 g/L was prepared by removing 8.9 mL CAMHB from commercially prepared 11-mL CAMHB tubes (ThermoFisher Scientific, Trek Diagnostics Systems) and replacing the broth with either 8.9 mL of sterile demineralized water or 8.35 mL of sterile demineralized water and 0.55 mL of horse serum.

Ten F. columnare isolates and 10 F. psychrophilum isolates were cultured from pure cryopreserved samples. Each isolate was subcultured twice in tryptone yeast-extract salts (TYES) broth (Holt et al. 1993) and incubated at either 28°C for 24 h (F. columnare) or 18°C for 72 h (F. psychrophilum). Turbidity suspensions (0.5 McFarland turbidity standard) of each isolate were prepared from the second subculture. Each suspension was vortexed and the clumps were allowed to settle for 1–3 min. The upper, more homogeneous fraction (~2 mL) was removed and adjusted as needed to a turbidity equivalent to a 0.5 McFarland turbidity standard with sterile saline. A 55-μL aliquot of this fraction was added to 11 mL of CAMHB diluted to 4 g/L with or without 5% horse serum to target a bacterial concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/mL. After vortex mixing, the inoculated dilute CAMHB was emptied into a sterile reservoir trough, and 100 μL was pipetted into each well of a sterile 96-well plate. A separate 96-well plate was inoculated for each isolate and broth combination. Flavobacterium columnare plates were incubated at 28°C, while F. psycrhophilum plates were incubated at 18°C.

Three replicate wells were sampled (100 μL each) from each 96-well plate at 0, 24, 48, 72, and 96 h for F. columnare isolates and at 0, 24, 48, 72, 96, 120, and 144 h for F. psychrophilum, and 10-fold serial dilutions (from 10–2 to 10–5) were prepared. A 100-μL aliquot of each 10-fold dilution was spread on TYES agar and incubated at 28°C for 48 h (F. columnare) and at 18°C for 96 h (F. psychrophilum). Viable cell concentrations (CFU/mL) were compared to determine whether serum supplementation improved growth and the optimal incubation time to target the log growth phase.

Turbidity level and inoculum volume for final target cell concentration in the test broth.—

To determine the McFarland turbidity and volume required to reliably achieve 5.0 × 105 CFU/mL bacterial concentrations in the broth microdilution plate wells, viable cells were enumerated directly from inoculated broth. Individual turbidity suspensions of 10 F. columnare isolates (0.5 McFarland standard) and 10 F. psychrophilum isolates (0.5 and 1.0 McFarland standards) were prepared from the second subculture as described above. Volumes of 55, 110, and 165 μL were removed from each cell suspension and added to a corresponding tube of 11 mL CAMHB diluted to 4 g/L corresponding to a 1:200, 1:100, and 1:67 dilution of the bacteria, respectively. A 1:1,000 dilution was prepared from each tube in sterile saline and 100 μL/plate was spread on three replicate TYES agar plates. The plates were incubated at 28°C for 24 h (F. columnare) and 18°C for 72 h (F. psychrophilum). Afterwards, plates were counted and CFU per milliliter calculated.

Effect of Ca++ and Mg++ supplementation on susceptibility.—

We compared the minimal inhibitory concentrations (MIC) determined with dilute broth supplemented with different levels of calcium and magnesium cations in order to confirm whether cations were needed for testing and to compare MICs between dilute and full-strength cation levels. The susceptibility of F. columnare (n = 6), F. psychrophilum (n = 6), E. coli ATCC 25922, and A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida ATCC 33658 to florfenicol and oxytetracycline was tested in 4-g/L MHB supplemented with full cations (20 mg/L Ca++, 10 mg/L Mg++), as suggested by the M49-A guideline for full strength CAMHB, in 4-g/L MHB supplemented with dilute cations (4 mg/L Ca++, 2 mg/L Mg++) and in plain 4-g/L MHB with no cations (CLSI 2006b).

In-house broth microdilution 96-well plates were prepared with FFN (from 32 to 0.015 μg/mL) or OTC (from 16 to 0.008 μg/mL) following the M49-A guideline (CLSI 2006b). Mueller–Hinton broth was prepared from dehydrated media (BD Diagnostic Systems, Sparks, Maryland) and supplemented with Ca++ and Mg++ cations using stock solutions of calcium chloride (10 mg/mL Ca++) and magnesium chloride (10 mg/mL Mg++) (Acros, Fair Lawn, New Jersey). Separate plates were made for each drug in each broth.

To make the custom 96-well plates, the highest final drug concentration was prepared in broth media at twice the target concentration in a 50-mL centrifuge tube by adding calculated amounts of stock drug solutions (1,280 μg/mL). To allow for subsequent twofold dilutions, we doubled the volume needed to fill the first column of the 96-well plates. The highest drug concentration was then serially diluted twofold 11 times in the same broth media in 50-mL centrifuge tubes. An aliquot of 50 μL of the appropriate concentration was added to the appropriate column of sterile 96-well plates using a multichannel pipette. The final two wells in the last row of the well plates were filled with plain broth; one to be left uninoculated as a negative control and the other inoculated with the cell suspension as a positive control. Plates were stored at ≤−70°C in sterile plastic bags until they were used within 2 months.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations were determined using the M49-A guideline for broth microdilution testing with adaptions developed here for making Flavobacterium spp. cell suspensions (CLSI 2006b). Each isolate was subcultured twice in TYES broth (F. columnare and F. psychrophilum) or on a blood agar plate (BAP; E. coli and A. salmonicida). Broth and agar plates were incubated at either 28°C for 24 h (F. columnare) or 18°C for 72 h (F. psychrophilum). Separate E. coli ATCC 25922 and A. salmonicida ATCC 33658 cultures were subcultured alongside the Flavobacterium isolates at each incubation temperature. Five replicate cell suspensions (0.5 McFarland turbidity standard) were made for each isolate. Suspensions were diluted 1:50 (Flavobacterium spp.) or 1:100 (E. coli and A. salmonicida) in separate 5-mL aliquots of the three broths. An aliquot of 50 μL of each inoculated broth was added to a row of a broth microdilution plate containing either FFN or OTC and made with the corresponding broth; one row for each isolate tested. Each plate was inoculated with all six F. columnare or all six F. psychrophilum isolates, E. coli, and A. salmonicida. Cell density was monitored in the broth supplemented with dilute cations with colony counts as described from three replicates of each bacterium using TYES (Flavobacterium spp.) or BAP (QC bacteria) agar plates. The broth microdilution and colony count plates were incubated at either 28°C for 48 h (F. columnare) or 18°C for 96 h (F. psychrophilum). After incubation the broth microdilution plates were read and MIC results determined (CLSI 2006b).

Stability of ATCC strains under test conditions.—

The susceptibility of E. coli ATCC 25922 and A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida ATCC 33658 was tested after multiple consecutive subcultures to examine the stability under culture conditions developed for testing F. columnare and F. psychrophilum. Both strains were subcultured every 24 h at 28°C and every 72–96 h at 18°C. Susceptibility to enrofloxacin (from 2 to 0.001 μg/mL), erythromycin (from 128 to 0.06 μg/mL), florfenicol (from 16 to 0.008 μg/mL), flumequine (from 8 to 0.004 μg/mL), gentamicin (from 8 to 0.004 μg/mL), oxytetracycline (from 32 to 0.015 μg/mL), and oxolinic acid (from 4 to 0.002 μg/mL) was examined with broth microdilution plates prepared in-house as described above at 28°C after 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 subcultures and at 18°C after 5, 10, and 15 subcultures.

Intralaboratory testing.—

To compare the results of tests conducted by different operators, four operators each tested three separate bacterial suspensions of each of six F. columnare isolates at 28°C and three separate bacterial suspensions of each of six F. psychrophilum isolates at 18°C. Tests of three separate bacterial suspensions of E. coli ATCC 25922 and A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida ATCC 33658 were also included at each temperature. Susceptibility to ampicillin (from 32 to 0.015 μg/mL), oxytetracycline (from 32 to 0.015 μg/mL), florfenicol (from 16 to 0.008 μg/mL), and ormethoprim/sulfadimethoxine (from 4/76 to 0.002/0.04 μg/mL) were assayed. Custom frozen broth microdilution plates were prepared and used as described previously. All bacterial suspensions were prepared and tested on the same day.

RESULTS

Effect of Horse Serum Supplementation and Incubation Time on Growth

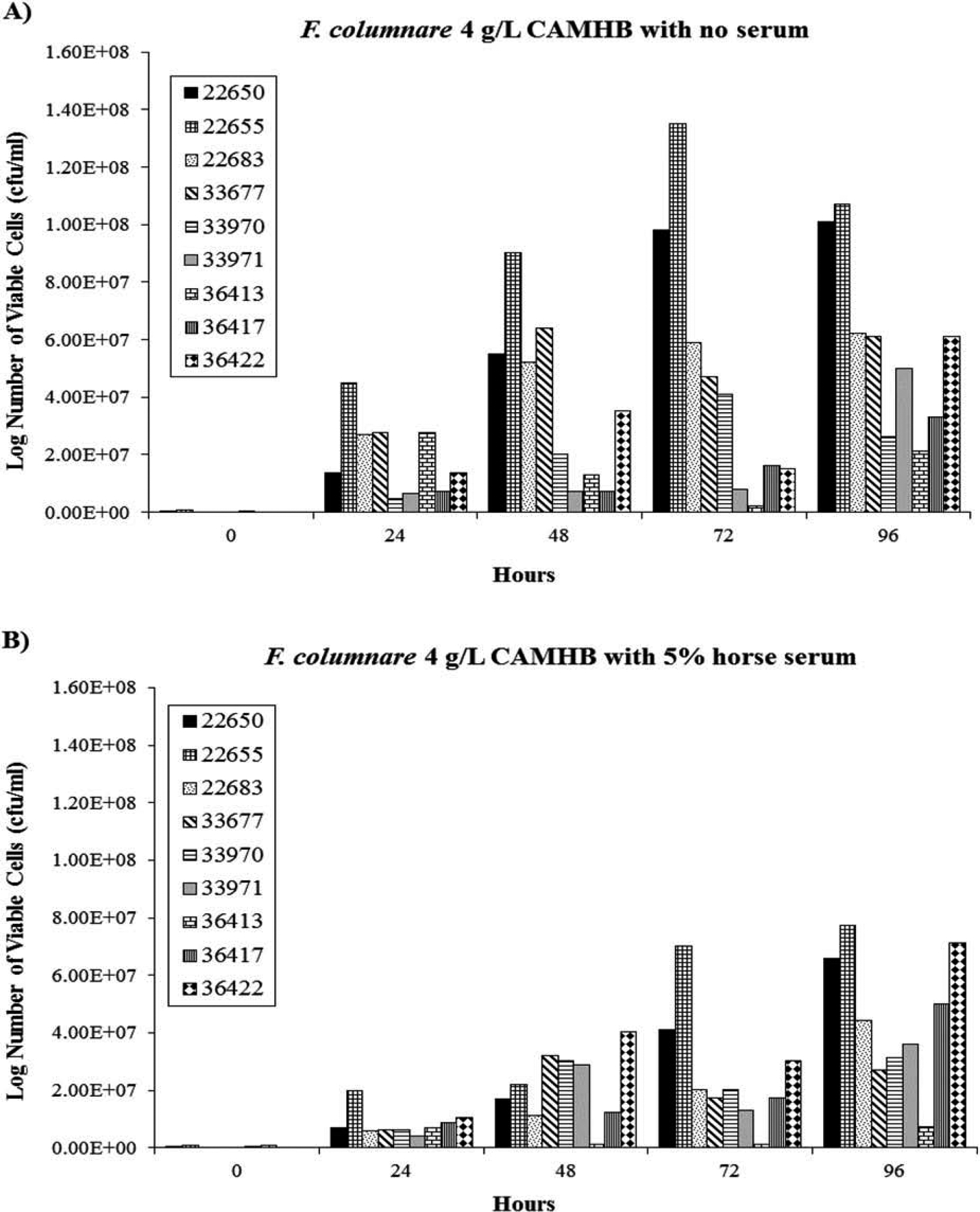

Five percent horse serum did not improve the growth of F. columnare or F. psychrophilum in 4-g/L CAMHB (Figures 1, 2). The number of viable cells for most of the isolates was higher at each time point in plain 4-g/L CAMHB. Most of the F. columnare isolates (six of nine) appeared to be in log-phase growth by 48 h. These isolates either had a rapid increase in cell number that peaked at 72 h or a rapid increase at 48 h that remained at a relative plateau. The growth of another isolate (36413) peaked at 24 h and stayed relatively constant. The last two isolates (33971 and 36417) grew slowly without a noticeable increase until 96 h. One isolate (36434) did not grow when initially subcultured and therefore was excluded from the experiment.

FIGURE 1.

Growth of F. columanre (n = 9) in 4-g/L, dilute, cation-adjusted, Mueller–Hinton broth (CAMHB) supplemented (A) without or (B) with 5% horse serum.

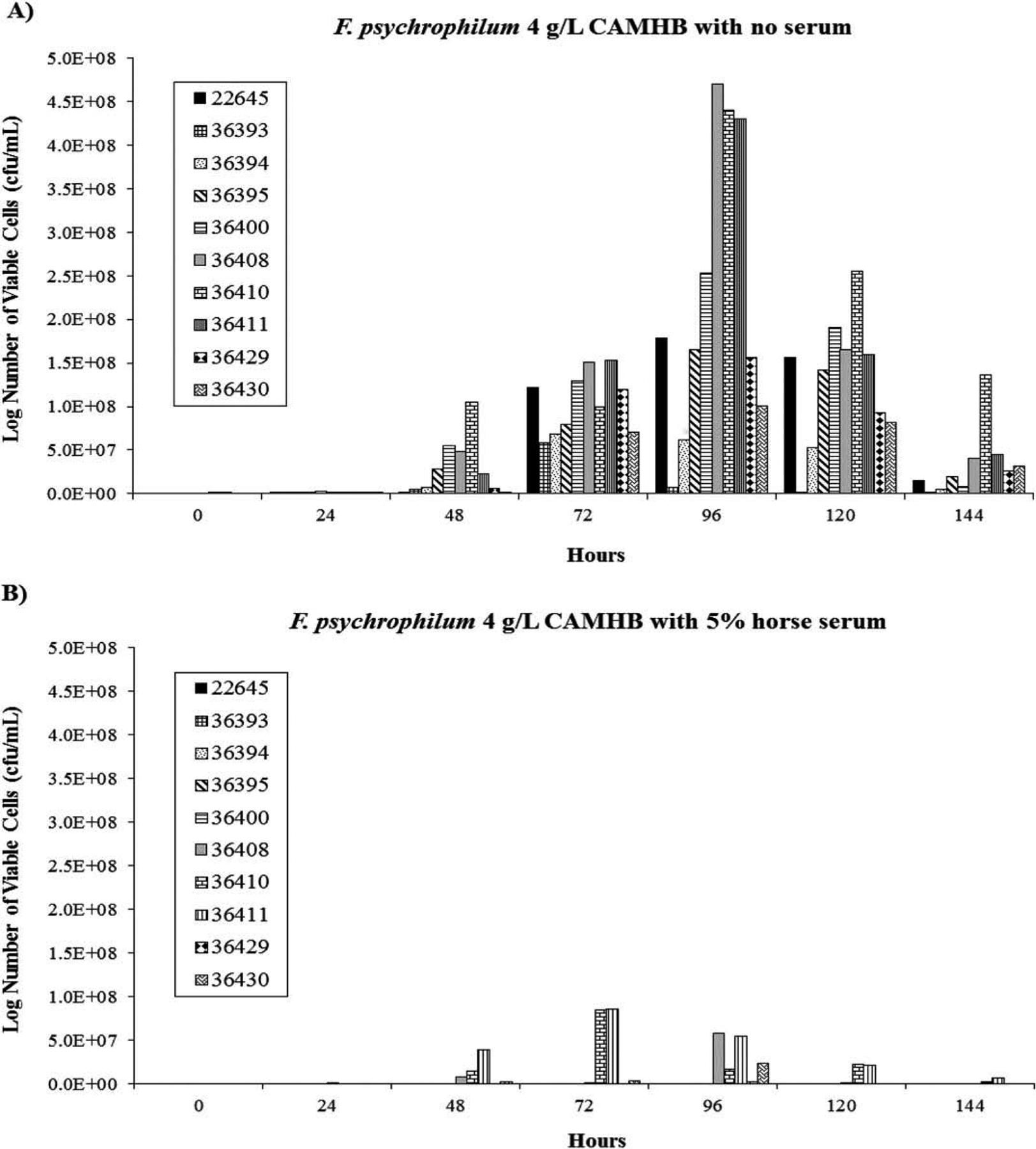

FIGURE 2.

Growth of F. psychrophilum (n = 10) in 4-g/L dilute, cation-adjusted, Mueller–Hinton broth (CAMHB) supplemented (A) without or (B) with 5% horse serum.

All of the F. psychrophilum isolates grew in plain 4-g/L CAMHB, but some did not grow in the serum-supplemented broth. The number of viable cells for most of the isolates peaked at 96 h in plain 4-g/L CAMHB then declined; however, growth peaked at 72 h for two isolates (36393 and 36394).

Turbidity Level and Inoculum Volume for Final Target Cell Concentration in the Test Broth

The mean cell concentration (CFU/mL) and SDs of 10 F. columnare and 10 F. psychrophilum isolates in cell suspensions at different McFarland turbidity standards and inoculum volumes used to prepare broth for microdilution testing are listed in Table 2. Dilute CAMHB (11 mL) inoculated with either 110 μL or 165 μL of a 0.5 McFarland suspension of F. columnare most closely achieved the initial target cell concentration of 5.0 × 105 CFU/mL. Dilute CAMHB inoculated with 55 μL of a 0.5 McFarland standard suspension or 55 μL of a 1.0 McFarland suspension of F. psychrophilum most closely achieved 5.0 × 105 CFU/mL for F. psychrophilum.

TABLE 2.

Mean number of cells (CFU/mL) and SDs of 10 F. columnare and 10 F. psychrophilum isolates in cell suspensions at different McFarland turbidity standards and inoculum volumes used to prepare an inoculum suspension for broth microdilution testing.

| McFarland suspension | Inoculum volume (μL) | Mean cell number (CFU/mL) | SD (CFU/mL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flavobacterium columnare | |||

| 0.5 | 55 | 3.5 × 105 | 1.1 × 105 |

| 0.5 | 110a | 7.4 × 105 | 6.2 × 105 |

| 0.5 | 165 | 7.5 × 105 | 2.6 × 105 |

| Flavobacterium psychrophilum | |||

| 0.5 | 55 | 6.3 × 105 | 2.6 × 105 |

| 0.5 | 110 | 1.1 × 106 | 4.8 × 105 |

| 0.5 | 165 | 1.5 × 106 | 4.9 × 105 |

| 1.0 | 55 | 8.5 × 105 | 2.2 × 105 |

| 1.0 | 110 | 1.6 × 106 | 4.2 × 105 |

| 1.0 | 165 | 2.0 × 106 | 6.6 × 105 |

One isolate had an unusually high cell concentration due most likely to technician error. Without this isolate the mean and SD values were 5.7 × 105 and 1.8 × 105 CFU/mL, respectively.

Effect of Ca++ and Mg++ Supplementation on Antimicrobial Susceptibility

Without cations the MICs of the F. columnare were consistently one to two dilutions below the MICs determined by using cations (Table 3). Most of the MICs agreed between the two cation levels; however, some F. columnare did not grow in the unsupplemented broth or in the presence of full-strength cations. All of the isolates grew in the broth supplemented with dilute cations.

TABLE 3.

Minimal inhibitory concentrations (μg/mL) of F. columnare, F. psychrophilum, A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida ATCC 33658, and E. coli ATCC 25922 from broth microdilution testing in 4-g/L cation-adjusted Mueller–Hinton broth supplemented with different levels of calcium and magnesium cations. NC = no cations, DC = dilute cations, FC = full cations.

| Isolate number | Oxytetracycline | Florfenicol | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NC | DC | FC | NC | DC | FC | |

| Flavobacterium columnare, 28°C | ||||||

| 22650 | 0.03 | 0.06–0.12 | No growth | 0.5–1 | 2 | No growth |

| 22683 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.12–2 | 2 | 2 |

| 33970 | 0.03 | 0.12 | 0.12–0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 2 |

| 36417 | 2 | 8 | 8 | 0.5 | 1–2 | 1 |

| 36422 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 1–2 | 1 | 1–2 |

| 36445 | No growth | 0.06–0.12 | No growth | No growth | 1 | No growth–0.25 |

| A. salmonicida ATCC 33658 | 0.12 | 0.25–0.5 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | 0.5 | 1 | 1 | 8–16 | 8 | 8 |

| Flavobacterium psychrophilum, 18°C | ||||||

| 22645 | No growth | 0.12 | 0.12–0.25 | No growth | 1 | 1 |

| 36395 | No growth–0.03 | 0.06 | 0.12 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 36396 | No growth | 0.12 | 0.12–0.25 | No growth | 1–2 | 2 |

| 36400 | No growth | 4 | 4–8 | No growth | 1 | 1–2 |

| 36410 | No growth | 8 | 16 | No growth | 2 | 1–2 |

| 36429 | No growth | 0.12 | 0.25 | No growth | 1 | 1–2 |

| A. salmonicida ATCC 33658 | 0.12 | 0.12 | 0.5 | 2 | 1 | 1–2 |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | 0.25 | 0.5 | 1 | 16–32 | 16 | 16–32 |

Most of the F. psychrophilum isolates did not grow in the unsupplemented broth; however, all of the isolates grew in the cation-supplemented broths. The MICs determined for each isolate from the two supplemented broths agreed within one dilution.

The MICs of the QC bacteria agreed across the drugs and cation levels at both incubation temperatures. The cation levels had a dose-dependent effect on the oxytetracycline MICs of A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida ATCC 33658 at 28°C and E. coli ATCC 25922 at 18°C.

Stability of ATCC Strains under Test Conditions

All MIC results for each drug agreed within one dilution for both bacteria at 28°C for up to 30 subcultures and at 18° C for up to 15 subcultures. Ampicillin and the two sulfonamide drugs were not tested because of the stability observed in the first seven drugs tested. Both E. coli ATCC 25922 and A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida ATCC 33658 had consistent MIC results against ampicillin and ormetoprim–sulfadimethoxine during intralaboratory testing.

Intralaboratory Testing

All of the F. columnare MICs agreed between the operators within one dilution of the mode for florfenicol and oxytetracycline (Table 4). Except for one isolate, all of the ampicillin MICs also agreed. The MIC results were more variable with the potentiated sulfonamide. Four of the six isolates agreed within a dilution but the remaining two isolates only agreed 75% and 50% of the time, respectively. Both E. coli ATCC 25922 and A. salmonicida subsp. salmonicida ATCC 33658 had stable MICs at the conditions for testing F. columnare.

TABLE 4.

Percent agreement among four operators in broth microdilution testing of six F. columnare, six F. psychrophilum, and two potential QC strains with specialized conditions developed for these nutritionally fastidious Flavobacteria. AMP = ampicillin, FFN = florfenicol, OTC = oxytetracycline, PRI = ormetoprim/sulfadimethoxine.

| Isolate number | AMP | FFN | OTC | PRI |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flavobacterium columnare, 28°C, 48 h | ||||

| 22650 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 22655 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 22683 | 100 | 100 | 100a | 75 |

| 33971 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| 36413 | 100d | 100b | 100 | 50 |

| 36434 | 73a | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 100 |

| A. salmonicida ATCC 33658 | 100a | 100a | 100a | 100a |

| Flavobacterium psychrophilum, 18°C, 96 h | ||||

| 36391 | 100a,c | 100 | 100a | 92 |

| 36396 | 100 | 100 | 91a | 83 |

| 36400 | 100 | 100 | 100a | 92 |

| 36403 | 100a | 100a | 100a | 91a |

| 36410 | 100 | 100 | 100 | 75 |

| 36429 | 92 | 100 | 100a | 75 |

| E. coli ATCC 25922 | 100 | 100d | 92 | 100 |

| A. salmonicida ATCC 33658 | 92 | 100 | 92 | 100 |

Average of 11 replicates since the bacteria did not grow in one replicate.

All MIC results were above the highest drug concentration tested.

Some isolates had MIC at the lower limit or less, presumed to agree within a dilution.

Some isolates had MIC at the upper limit or greater, presumed to agree within a dilution.

We observed a similar trend for F. psychrophilum. At least 91% of MICs agreed between the operators within a dilution of the mode for florfenicol and oxytetracycline. Likewise most of ampicillin MICs agreed for five of the six isolates. Agreement was lower with the potentiated sulfonamide but was at least 75%. The tested QC strains also had stable MICs at the F. psychrophilum test conditions. Agreement was lower with the potentiated sulfonamide but was at least 75%. The tested QC strains also had stable MICs at the F. psychrophilum test conditions.

DISCUSSION

The broth microdilution testing procedures presented in this paper used the same test media for both F. columnare and F. psychrophilum. As previously reported, based on the work presented here and in Gieseker et al. (2012), supplementing the broth media with 5% horse serum was not necessary as it was with agar dilution and disk diffusion tests (Hawke and Thune 1992; Bruun et al. 2000; Schmidt et al. 2000; Michel et al. 2003; Farmer 2004). Both QC bacteria currently used for nonfastidious aerobic aquatic bacteria grew well at the test conditions and had precise MIC results that were similar to the MIC ranges for QC bacteria established in full-strength Mueller–Hinton broth (Miller et al. 2005; CLSI 2006b). In addition, the methods proved reliable when compared among different operators.

By allowing a few minutes for the aggregated cells to settle out of suspension, we were able to make cell suspensions at the standard turbidity level from statically grown cultures of F. columnare. Compared with standard procedures for other organisms (CLSI 2006b) more of this suspension had to be added to the broth (1:100 dilution) to get the target cell concentration of 5 × 105 CFU/mL, presumably because F. columnare cells are relatively large compared with other bacteria. With this approach, we consistently prepared broth inocula that approximated the correct number of cells.

Alternatively, cultures grown while continually mixing (i.e., shaking or stirring) can likely improve the consistency of the cell suspensions. Laboratories that test F. columnare and F. psychrophilum susceptibility commonly use mixing when growing the primary cultures (Bruun et al. 2000; Darwish et al. 2008). Therefore, when testing these Flavobacterium species laboratories should first practice their methods to prepare the broth inoculums in order to obtain consistent results.

Unfortunately, F. psychrophilum isolates differ greatly from each other in growth rate making it hard to consistently prepare inocula with similar cell concentrations. In this study, the broth inoculum averaged the target cell concentration most closely when the suspensions at the standard turbidity were diluted in broth at the standard concentration (1:200). However, in preliminary testing, we found the broth inoculums should be made in the same way as F. columnare. The lower dilution resulted in more consistent cultures, preventing excessively low cell numbers of slow-growing isolates.

The growth of F. columnare sharply increased through 48 h then slowed, suggesting, as previously established, that susceptibility tests of F. columnare should be incubated for 48 h at 28°C (Darwish et al. 2008). Growth of F. psychrophilum peaked at 96 h then sharply declined. Although the cells were growing in log phase by 72 h, we chose to incubate our broth microdilution tests for 96 h to better account for slow-growing isolates.

We tested F. psychrophilum at 18°C since its generation time at this temperature is very similar to the established in vitro optimum of 15°C (Holt et al. 1989). In addition, existing QC bacteria would presumably grow better; therefore, no new QC bacteria would be needed. As such, we found that drug susceptibility of both existing QC bacteria (CLSI 2006b) were stable at both 28°C and 18°C in the dilute media.

Supplementing the broth with calcium and magnesium cations works best for broth dilution testing F. columnare and is required for testing of F. psychrophilum. Cations diluted to the same level as the broth (4 g/L) provided MIC results similar to results from tests conducted in dilute broth containing cations at full strength; therefore, commercially available CAMHB diluted to 4 g/L can be used. Commercial broth gives laboratories the convenience of not having to make media as well as possibly easier storage conditions and extended shelf life.

Flavobacterium psychrophilum clearly needs cations to grow in 4-g/L dilute Mueller–Hinton broth, and cations could have also enhanced the growth of F. columnare creating the differences in antimicrobial susceptibility observed between the different cation levels. The calcium and magnesium cation levels we supplemented were similar to concentrations that allow F. columnare to survive and grow in supplemented distilled water (Chowdhury and Wakabayashi 1988). However, future research should also evaluate whether adding cations to the dilute Mueller–Hinton broth affects the formation of biofilm since biofilm-associated bacterial cells can have decreased antimicrobial susceptibility compared with free-floating planktonic cells (Soriano et al. 2009; Reiter et al. 2012). Flavobacterium columnare can form biofilms on the surface of polystyrene plates in a wide range of calcium cation levels (12–360 ppm hardness [CaCl2·2H2O]: Cai et al. 2013). In addition, high densities (>107 CFU/mL) of in vitro biofilm-associated F. psychrophilum cells grown in TYES broth can have decreased susceptibility to antimicrobials (Sundell and Wiklund 2011), although TYES broth has higher cation levels (500 ppm) than those we used.

Although full strength CAMHB was recently used for broth microdilution testing of F. psychrophilum (Hesami et al. 2010), we chose dilute media to have similar methods for testing both F. columnare and F. psychrophilum and to be in line with suggested media recommendations (Alderman and Smith 2001; CLSI 2006b). The procedures and growth conditions developed in this study along with the recently developed QC limits (Gieseker et al. 2012) have led to the first standardized antimicrobial susceptibility testing method for these fastidious bacteria (CLSI 2014). We hope this method will improve the monitoring for antimicrobial resistance among isolates of F. columnare and F. psychrophilum.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank R. Avendaño-Herrera, J.-F. Bernardet, K. D. Cain, D. R. Call, O. L. M. Haenen, J. P. Hawke, H.-M. Hsu, J. C. Newton, and staff at the Mississippi State University, College of Veterinary Medicine Aquatic Diagnostic Laboratory for their generous contributions of Flavobacteria isolates used in our experiments. We also thank R. A. Miller, L. C. Woods III, and R. Reimschuessel for their review of the manuscript. The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and may not reflect the official policy of the Department of Health and Human Services, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, or the U.S. Government.

REFERENCES

- Alderman DJ, and Smith P. 2001. Development of draft protocols of standard reference methods for antimicrobial agent susceptibility testing of bacteria associated with fish diseases. Aquaculture 196:211–243. [Google Scholar]

- Bruun MS, Schmidt AS, Madsen L, and Dalsgaard I. 2000. Antimicrobial resistance patterns in Danish isolates of Flavobacterium psychrophilum. Aquaculture 187:201–212. [Google Scholar]

- Cai W, de la Fuente L, and Arias CR. 2013. Biofilm formation by the fish pathogen Flavobacterium columnare: development and parameters affecting surface attachment. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 79:5633–5642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chowdhury MBR, and Wakabayashi H. 1988. Effects of sodium, potassium, calcium and magnesium ions on the survival of Flexibacter columnaris in water. Fish Pathology 23:231–235. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute). 2006a. Methods for antimicrobial disk susceptibility testing of bacteria isolated from aquatic animals: approved guideline. CLSI, Document M42-A, Wayne, Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI (Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute). 2006b. Methods for broth dilution susceptibility testing of bacteria isolated from aquatic animals: approved guideline. CLSI, Document M49-A, Wayne, Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- CLSI (Clinical Laboratory Standards Institute). 2014. Methods for broth dilution susceptibility testing of bacteria isolated from aquatic animals: approved guideline, 2nd edition. CLSI, Document VET04-A2, Wayne, Pennsylvania. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato RF, Thornsberry C, Baker CN, and Kirven LA. 1975. Effect of calcium and magnesium ions on the susceptibility of Pseudomonas species to tetracycline, gentamicin, polymyxin B, and carbenicillin. Antimicrobial Agents and Chemotherapy 7:596–600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwish AM, Farmer BD, and Hawke JP. 2008. Improved method for determining antibiotic susceptibility of Flavobacterium columnare isolates by broth microdilution. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health 20:185–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darwish AM, Ismaiel AA, Newton JC, and Tang J. 2004. Identification of Flavobacterium columnare by a species-specific polymerase chain reaction and renaming of ATCC 43622 strain to Flavobacterium johnsoniae. Molecular and Cellular Probes 18:421–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Declercq AM, Boyen F, Van den Broeck W, Bossier P, Karsi A, Haesebrouck F, and Decostere A. 2013. Antimicrobial susceptibility pattern of Flavobacterium columnare isolates collected worldwide from 17 fish species. Journal of Fish Diseases 36:45–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Del Cerro A, Márquez I, and Prieto JM. 2010. Genetic diversity and antimicrobial resistance of Flavobacterium psychrophilum isolated from cultured Rainbow Trout, Oncorhynchus mykiss (Walbaum), in Spain. Journal of Fish Diseases 33:285–291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer BD 2004. Improved methods for the isolation and characterization of Flavobacterium columnare. Master’s thesis. Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge. [Google Scholar]

- Gieseker CM, Mayer TD, Crosby TC, Carson J, Dalsgaard I, Darwish A, Gaunt PS, Gao DX, Hsu H-M, Lin TL, Oaks JL, Pyecroft M, Teitzel C, Somsiri T, and Wu CC. 2012. Quality control ranges for testing broth microdilution susceptibility of Flavobacterium columnare and F. psychrophilum to nine antimicrobials. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 101:207–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawke JP, and Thune RI. 1992. Systemic isolation and antimicrobial susceptibility of Cytophaga columnaris from commercially-reared Channel Catfish. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health 4:109–113. [Google Scholar]

- Hesami S, Parkman J, MacInnes JI, Gray JT, Gyles CL, and Lumsden JS. 2010. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Flavobacterium psychrophilum isolates from Ontario. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health 22:39–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holt RA, Amandi A, Rohovec JS, and Fryer JL. 1989. Relation of water temperature to bacterial cold-water disease in Coho Salmon, Chinook Salmon, and Rainbow Trout. Journal of Aquatic Animal Health 1:94–101. [Google Scholar]

- Holt RA, Rohovec JS, and Fryer JL. 1993. Bacterial cold-water disease. Pages 3–22 in Inglis V, Roberts R, and Bromage NR, editors. Bacterial diseases of fish. Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Michel C, Kerouault B, and Martin C. 2003. Chloramphenicol and florfenicol susceptibility of fish pathogenic bacteria isolated in France: comparison of minimum inhibitory concentration, using recommended provisory standards for fish bacteria. Journal of Applied Microbiology 95:1008–1015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RA, Walker RD, Baya A, Clemens K, Coles M, Hawke JP, Henricson BE, Hsu H-M, Mathers JJ, Oaks JL, Papapetropoulou M, and Reimschueseel R. 2003. Antimicrobial susceptibility testing of aquatic bacteria: quality control disk diffusion ranges for Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 and Aeromonas salmonicida subsp. salmonicida ATCC 33658 at 22 and 28 degrees C. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 41:4318–4323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller RA, Walker RD, Carson J, Coles M, Coyne R, Dalsgaard I, Gieseker CM, Hsu H-M, Mathers JJ, Papapetropoulou M, Petty B, Teitzel C, and Reimschuessel R. 2005. Standardization of a broth microdilution susceptibility testing method to determine minimum inhibitory concentrations of aquatic bacteria. Diseases of Aquatic Organisms 64:211–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nanavaty J, Mortensen JE, and Shyrock TR. 1998. The effects of environmental conditions on the in vitro activity of selected antimicrobial agents against Escherichia coli. Current Microbiology 36:212–215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pacha RE 1968. Characteristics of Cytophaga psychrophila (Borg) isolated during outbreaks of bacterial cold-water disease. Applied Microbiology 16:97–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rangdale RE, Richards RH, and Alderman DJ. 1997. Minimum inhibitory concentrations of selected antimicrobial compounds against Flavobacterium psychrophilum the causal agent of Rainbow Trout fry syndrome (RTFS). Aquaculture 158:193–201. [Google Scholar]

- Reiter KC, Villa B, da Silva Paim TG, Sambrano GE, de Oliveria CF, and d’Azevedo PA. 2012. Enhancement of antistaphycoccal activities of six antimicrobials against sasG-negative methicillin-susceptible Staphylococcus aureus: an in vitro biofilm model. Diagnostic Microbiology and Infectious Disease 74:101–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt AS, Bruun MS, Dalsgaard I, Pedersen K, and Larsen J. 2000. Occurrence of antimicrobial resistance in fish-pathogenic and environmental bacteria associated with four Danish Rainbow Trout farms. Applied Environmental Microbiology 66:4908–4915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soriano F, Huelves L, Naves P, Rodriguez-Cerrato V, del Prado G, Ruiz V, and Ponte C. 2009. In vitro activity of ciprofloxacin, moxifloxacin, vancomycin and erythromycin against planktonic and biofilm forms of Corynebacterium urealyticum. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy 63:353–356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sundell K, and Wiklund T. 2011. Effect of biofilm on antimicrobial tolerance of Flavobacterium psychrophilum. Journal of Fish Diseases 34:373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toyama T, Kita-Tsukamoto K, and Wakabayashi H. 1994. Identification of Cytophaga psychrophila by PCR targeted 16S ribosomal RNA. Fish Pathology 29:271–275. [Google Scholar]